Abstract

Bullying remains a significant social problem among youth and many school interventions focus on increasing bystander defending in order to reduce bullying. In this study, we employed a between-groups experimental design to examine the differential effects of brief empathy and compassion activation on different bystander responses to bullying, including (1) empathic distress, empathic anger, compassion, and (2) intended bystander behaviors (i.e., passive bystanding, aggressive defending, and prosocial defending). Participants were 110 adolescents (Mage = 13.99, SD = 0.88, age range = 13–16 years; 49.1% females), randomly assigned to an experimental group that involved a 10-min visualization exercise that focused on increasing empathy [EM] or compassion [CM], or to an active control condition [FI]. Following the visualization exercise, students viewed four short bullying videos, followed by completing self-report measures of empathy-related responses and intended bystander behaviors. Analysis of variance [ANOVAs] revealed that adolescents in the CM condition reported less empathic distress and empathic anger in response to the bullying videos than the EM and FI groups. Yet, there were no further differential effects between the three conditions on responses to the bullying videos, which emphasizes the need for future research to assess more comprehensive interventions for increasing adolescents’ compassion and prosocial defending.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Bullying is a widespread social problem (Menesini & Salmivalli, 2017; Ttofi & Farrington, 2011) that is related to elevated and chronic social and mental health problems for children and adolescents (Arseneault, 2017; Ttofi et al., 2014). Bullying is not usually hidden from view. Instead, bystanders are present for about 85% of child and adolescent bullying incidents, making it important to understand how, when, and why these witnesses stop peer bullying (Hawkins et al., 2001; Menesini & Salmivalli, 2017; Sainio et al., 2010). Indeed, prosocial defending responses, such as comforting the victimized peer or involving an adult for help, can reduce the negative outcomes for victimized individuals and potentially reduce bullying behavior (Jung & Schröder-Abé, 2019; Sainio et al., 2010).

Many school interventions focus on increasing defending behaviors to reduce bullying (Gaffney et al., 2019; Polanin et al., 2012). However, most bystanders to bullying remain passive observers (Hawkins et al., 2001; Pozzoli et al., 2017; Salmivalli, 2010). Passivity is not the best response to witnessing bullying as it facilitates pro-bullying norms by giving the impression that bullying is acceptable, which in turn reinforces bullying behavior (Juvonen & Galván, 2008). In addition, among bystanders who intervene, some respond with aggressive defending directed at the person bullying (Lambe & Craig, 2020; Reijntjes et al., 2016), which may escalate the bullying and reinforce aggressive behavior as a means of resolving conflicts (Frey et al., 2015; Hawkins et al., 2001). Given the potential harmful consequences of passivity and aggressive defending, research is needed to understand intervention strategies that enhance bystanders’ abilities to use more constructive and prosocial responses. Based on theories and emerging research on the role of empathy and compassion in prosocial behavior (Singer & Klimecki, 2014; Stevens & Taber, 2021), and as a step towards encouraging the refinement of intervention content to improve the effectiveness of bystander interventions, the purpose of this study was to examine adolescents’ empathy-related responses to witnessing bullying and intentions to defend following either a brief empathy or compassion activation exercise.

Empathy and Bystander Responses

Defending research has shown that empathy, defined as the ability to understand (i.e., cognitive empathy or perspective taking) and share the emotional states of others (i.e., affective empathy), is positively associated with defending against bullying (for a systematic review, see Lambe et al., 2019). However, emerging theory and research in the prosocial and affective neuroscience literature (Singer & Klimecki, 2014; Stevens & Taber, 2021) indicate a complex relationship between empathy and prosocial behavior. As empathy training is designed to increase the ability to resonate with and share others’ distress, there can be a resulting increase in focus on one’s own negative emotions (Klimecki et al., 2014). Critically, a focus on one’s personal aversive emotional experience can result in empathic distress (also known as personal distress), defined as the excessive sharing of others’ distress, which in turn may motivate self-protective behaviors, such as avoidance and passivity, rather than other-protective defending behaviors (Batson et al., 1987; Singer & Klimecki, 2014). Teaching adolescents to be more empathic towards victimized peers may therefore serve to inadvertently increase their empathic distress, which in turn can lower their likelihood of intervention when witnessing bullying.

In addition, consistent with Hoffman’s theory of empathy (2001), empathy can activate feelings of anger on behalf of others when witnessing someone being treated in an unfair or harmful way. This form of response is referred to as empathic anger or third-party anger and reflects an other-condemning moral emotion. Hoffman proposes that empathic anger is an important inhibitor of passivity by acting as a moral motivator of action to restore justice, but this can also lead to retaliation and aggression. Vitaglione and Barnett (2003) demonstrated that adults who reported greater empathic anger in response to witnessing individuals who have been intentionally hurt were motivated to support these individuals and to punish the person who offended. Similar findings have been shown in more general bystander research (Buffone & Poulin, 2014; Gummerum et al., 2016; van Doorn et al., 2018). In the context of bullying, defending research has shown that dispositional levels of empathic anger are associated with less passivity and more overall defending (Pozzoli et al., 2017), as well as intended prosocial and aggressive defending specifically (Steinvik et al., 2023). These findings emphasize the importance of understanding ways to direct anger to prosocial, constructive defending strategies to prevent aggressive defending.

Taken together, research indicates that empathy may lead to distinctive empathic responses and subsequent bystander behaviors, ranging from passivity to aggressive and prosocial action (Singer & Klimecki, 2014; Vitaglione & Barnett, 2003). Thus, although empathy in response to witnessing the distress of others may lead to feelings of concern and prosocial helping in some instances, empathy experienced as empathic distress may increase passivity, whereas empathic anger may also increase the likelihood of aggressive defending (e.g., retaliation).

Although empathy training is a component of many interventions (Cefai et al., 2018; Gaffney et al., 2019), there is limited research on the effects of empathy-based intervention on bystander responses in the context of bullying. For example, in a meta-analytical review of 141 independent effect sizes for the effectiveness of bullying intervention programs (Gaffney et al., 2019), empathy training was a core component in several interventions, but none of the studies assessed the unique effects of empathy training or considered all three outcomes of passive bystanding, aggressive defending, and prosocial defending. We could locate only one previous defending study (Barlińska et al., 2018) that examined empathy activation as a stand-alone intervention aimed at increasing bystander defending against bullying. In this study, adolescents (N = 265, Mage = 14.14) were randomly assigned to an empathy or control condition. Adolescents in the empathy condition watched a 2-min video depicting a cyberbullying episode while asked to concentrate on the victim and identify their emotions. Following the video, participants who received the empathy manipulation, compared to those in the control condition, reported a greater likelihood of prosocial defending, in the form of reporting the bullying, in response to a simulated online bullying interaction (Barlińska et al., 2018). However, this study did not include any measures of empathic responses, nor any measures of passivity or aggressive defending. Thus, it remains unknown whether empathy activation will affect different empathy-related responses and the likelihood of subsequent passivity, aggressive defending, and prosocial defending in the context of peer bullying.

Compassion as a Potential Avenue for Promoting Prosocial Defending

Compassion training could be an alternative or addition to empathy training that more specifically targets prosocial defending, while at the same time reducing the likelihood of passivity or aggressive defending. Indeed, compassion takes empathy a step further, by integrating distress tolerance, or the ability to tolerate difficult empathic emotions. In other words, compassion not only involves the ability to recognize and understand others’ emotions, but also the ability to tolerate resulting emotions such as distress or anger, and therefore experience empathy without becoming overwhelmed or reactive (Stevens & Taber, 2021; Strauss et al., 2016). Compassion is a complex construct and there is not one universally agreed-upon definition. However, based on recent research and conceptualizations (Gilbert & Mascaro, 2017; Pommier et al., 2020; Strauss et al., 2016), and for the purpose of this study, we conceptualize compassion as including the following interdependent abilities: (1) the ability to engage with and tolerate others’ distress, (2) feelings of concern/kindness in response to others’ distress, and (3) the ability to approach others’ distress/difficulties with non-judgement.

In the context of bullying, we could locate only two previous studies that measured compassion and considered its association with bystander responses to bullying. In a cyberbullying study, Steinvik et al. (2023) used dispositional trait measures used in previous research (Davis, 1983; Gilbert et al., 2017; Vitaglione & Barnett, 2003) to assess the unique associations of empathic distress, empathic anger, and compassion (not specific to the context of witnessing bullying) with bystander behavior intentions. In comparison to empathic distress and anger, dispositional levels of compassion were uniquely associated with intentions for less aggressive defending and more prosocial defending in response to cyberbullying. Expanding on this study, Steinvik et al. (2024) examined these empathy-related responses (i.e., empathic distress, empathic anger, and compassion) and intended bystander behaviors measured as self-reported situational responses to viewing brief video portrayals of face-to-face bullying. To our knowledge, this was the first study to measure compassion responses in response to bullying, in which compassion items were modelled on dispositional trait measures used in previous research (Gilbert & Mascaro, 2017; Pommier et al., 2020). The development of this measure involved two pilot studies to ensure that the bullying videos were realistic examples of bullying that elicited empathic feelings (see also the “Method” section) (Steinvik et al., 2024). Consistent with Steinvik et al.’s (2023) cyberbullying study, results revealed that adolescents who reported more compassion in response to watching the brief videos of face-to-face bullying intended to use less passive bystanding and aggressive defending, and more prosocial defending. However, we could locate no previous study that has investigated the causal effect of compassion on bystander responses to bullying, let alone compared the effects of compassion activation to empathy activation on adolescents’ intended responses of prosocial defending, aggressive defending, or passive bystanding.

In general, compassion-based interventions are thought to facilitate prosocial action by (1) reducing the negative and reactive emotional responses that can result in empathic distress and avoidance, and (2) enhancing kindness towards oneself and others, and a concern for the well-being of all others, as well as disliked others (Hofmann et al., 2011; Kirby et al., 2017; Weng et al., 2017). Such interventions most commonly include loving-kindness meditation [LKM] which involves the visualization and focus on directing phrases of loving kindness toward oneself and others (e.g., “may you be at ease”), and/or compassion meditation [CM], a form of LKM directed towards suffering others (e.g., “may you be free from suffering) (Hofmann et al., 2011; Salzberg & Kabat-Zinn, 2004; Shonin et al., 2015). Research on the effects of compassion-based interventions indicates potential benefits for children and adolescents (for a review, see Perkins et al., 2022), but this research remains in its infancy and there is little understanding of the effects on prosocial behaviors.

Despite the lack of research on compassion interventions among youth, a growing body of evidence shows various benefits for adults (Hofmann et al., 2011; Kirby et al., 2017; Luberto et al., 2018). Short- and long-term compassion interventions (Fredrickson et al., 2008; Klimecki et al., 2014), as well as brief single-session (i.e., 7–20 min) LKM, compared to controls can result in reduced negative affect and enhanced positive affect (Hutcherson et al., 2008; Kirby & Baldwin, 2018; Shonin et al., 2015), which facilitate people’s thought-action repertoires, believed to increase approach-related behaviors (Fredrickson, 2001; Fredrickson et al., 2008). Indeed, LKM and CM type compassion-based interventions have also been found to increase compassionate and prosocial responses to others’ distress (Ashar et al., 2016; Condon et al., 2013; Weng et al., 2015). Relatedly, CM has been found to increase adults’ visual attention (as indexed by eye-tracking data) towards cues of suffering in others as well as decreased amygdala responses, indicating greater levels of distress tolerance after CM (Weng et al., 2018).

In addition, consistent with evidence of compassion as linked with enhanced concern and non-judgement for all people, as well as disliked others and others who have intentionally done harm (Klimecki et al., 2016; Oveis et al., 2010; Sprecher & Fehr, 2005), compassion-based interventions may be beneficial for individuals who have a tendency toward anger and hostility. In line with this view, research indicates that compassion can reduce anger, aggression, and revengeful retaliation behaviors. For example, compassion induction in a controlled laboratory setting has been found to reduce the use of actual punishment for unfair treatment of others (i.e., cheating for financial gain) (Condon & DeSteno, 2011). Relatedly, long-term practitioners of compassion-related meditation compared to controls have been found to engage in less vengeful, retributive justice in response to the unfair treatment of the self and others (McCall et al., 2014).

In applying these findings to bystanders’ behavior in response to bullying, compassion training may help to mitigate against fight-flight-freeze responses when witnessing the unfair treatment of a person being bullied. Given this, and evidence of compassion’s unique contribution to prosocial defending (Steinvik et al., 2023, 2024), it could be argued that compassion training, more so than empathy training, might be particularly important for facilitating prosocial defending and preventing the likelihood of passivity and aggressive defending. To date, no studies have explored this proposition. In line with Barlińska et al.’s (2018) examination of the short-term effects of empathy activation, we aimed to provide a preliminary examination of the short-term effects of empathy versus compassion activation on these different responses to witnessing bullying.

The Current Study

The current study employed a between-groups experimental design to compare the effects of a brief audio-guided empathy meditation [EM] versus compassion meditation [CM] on adolescents’ (1) empathic distress, empathic anger, and compassion, and (2) intended behaviors (i.e., passive bystanding, aggressive defending, prosocial defending) in response to witnessing short video portrayals of bullying. The EM aimed to enhance students’ ability to understand and resonate with the distress/difficulties of their peers (i.e., increase empathy). In comparison, the CM aimed to cultivate a non-reactive and non-judgmental concern towards one’s own distress/difficulties, as well as the distress/difficulties of other peers (i.e., increase compassion). A third condition was an audio-guided focused imagery exercise (FI) to control for unspecific effects (e.g., fatigue) from the EM and CM. Adolescents were randomly assigned to one of these three conditions.

As gender, age, and past experiences with bullying are associated with bystander responses to bullying (Bussey et al., 2020; Lambe & Craig, 2020), preliminary analyses were conducted to ensure that the randomization process resulted in three comparable conditions. We also compared students’ self-reported engagement and affect in response to the EM, CM, and FI conditions to check the experimental manipulations (see hypotheses below). Finally, for our primary analyses comparing adolescents’ empathy-related responses (i.e., empathic distress, empathic anger, compassion) and intended bystander behaviors (i.e., video outcome measures) across conditions (EM, CM, FI), two primary hypotheses were tested (see below).

Hypotheses

Manipulation Check

H1: Upon completion, (a) participants in the CM condition will be higher in positive affect relative to participants in the EM and FI conditions. Also, (b) participants in the EM condition will be higher in negative affect relative to participants in the CM and FI conditions.

Responses to the Bullying Videos

H2: Participants in the CM, relative to the EM and FI, will be lower in (a) empathic distress and (b) empathic anger, (c) passive bystanding, and (d) aggressive defending, but higher in (e) compassion and (f) prosocial defending.

H3: Participants in the EM group, relative to the FI group, will be higher on all video outcome measures: (a) empathic distress, (b) empathic anger, (c) compassion, (d) passive bystanding, (e) aggressive defending, and (f) prosocial defending.

Method

Participants

The participants were 124 adolescents from two secondary schools in Australia. After principals consented to their schools’ participation, consent forms were sent home to parents, with only adolescents who received parental consent taking part in the study. Twelve adolescents were subsequently excluded as they did not complete the audio-guided exercise due to technology failure. In addition, two adolescents were excluded due to patterned responses to the survey. The final sample comprised 110 adolescents (Mage = 13.99, SD = 0.88, age range = 13–16 years, 49.1% females). The majority of participants (82.8%) reported they were born in Australia and 1% reported New Zealand as their birthplace. In addition, 31.9% identified as European, 10.9% as Australian First Peoples/Torres Strait Islander/Pacific Islander, 4.5% as Asian, 7.5% reported other cultural/ethnic backgrounds, and the remaining 45.2% reported no additional/other cultural/ethnic background.

Design and Procedure

Participants accessed the study in their classroom via an online survey link that randomly assigned them to either an experimental group (EM or CM) or an active control group (FI). Participants were informed that their participation is voluntary. The experiment was structured in five parts. First, after reading the study information, participants completed a set of demographic questions. Second, participants completed the 10-min audio-guided visualization exercise (i.e., EM, CM, or FI) and subsequent manipulation check items that measured their engagement with the visualization exercise. Third, participants viewed four short bullying videos (see the “Materials” section for more details) followed by survey questions. Specifically, before each video clip, participants were asked to imagine witnessing the same bullying incident at their own school. Following each of the four videos, participants completed the bullying video outcome measures (dependent measures): empathic distress, empathic anger, compassion, and their intentions to respond with passivity, aggressive defending, and prosocial defending. Fourth, after being provided with a definition of bullying, participants completed a set of questions about their own experience with bullying, victimization, and being a witness to bullying, as well as their bystander behaviors in response to witnessing bullying in the past months. Finally, all participants received a debriefing sheet from the experimenter at completion and a small gift voucher as a thank you. The procedures were approved by the Griffith University (Australia) Human Research Ethics Committee.

Materials

Audio-Guided Recordings

The three audio recordings were developed by the first author and recorded by an experienced meditation instructor for use in this study. All three recordings were approximately 10 min in duration. The EM and CM exercises were adapted from previous studies (Hofmann et al., 2011; Hutcherson et al., 2008; Kirby & Baldwin, 2018; Kirby & Laczko, 2017; Klimecki et al., 2014) to specifically target the activation of empathy (EM) or compassion (CM) for difficulties experienced by school peers, and were developed to be structural similar. The FI exercise was used as an active control condition that aimed to be structurally similar to the EM and CM, and was designed to control for the unspecific effects (e.g., fatigue) of the audio-guided recordings and visual imagery.

EM The EM exercise was designed to enhance the ability to understand and resonate with difficulties and challenges experienced by other adolescents. The guided imagery instructions first asked students to visualize a personal difficulty or challenge, while directing empathic phrases to oneself (e.g., “I can understand this distress and difficulty”). Next, students were instructed to visualize a difficulty or challenge experienced by a peer and direct empathic phrases to their peer (e.g., “I can understand your difficulty” and “I feel your difficulty”). This empathic sharing with the difficult or challenging experience of another was then extended toward a difficulty experienced by all students at the school. This EM exercise was adapted from previous research that assessed the effects of empathy training (e.g., Klimecki et al., 2014) and modified to focus specifically on enhancing the empathy for other adolescent peers rather than other people in general.

CM The CM was designed to cultivate care and friendliness toward personal difficulties and challenges, as well as the difficulties and challenges experienced by other adolescents. It followed a structured script including five steps: (1) a mindful focus on the breath; (2) visualization of a personal difficulty/challenge and directing loving kindness phrases to oneself (e.g., “may I feel safe and happy”); (3) visualization of a difficulty/challenge experienced by another and directing the loving kindness phrases to this other (e.g., “may you feel safe and happy”); (4) visualization of a difficulty/challenge experienced by a difficult peer and directing the loving kindness phrases to this difficult peer; (5) visualization of a difficulty/challenge experienced by all students at the school and directing loving kindness phrases to all. The CM is a form of LKM and was based on the structure provided by Hofmann et al. (2011), which has been used in previous studies testing the effects of LKM and CM (Kirby & Baldwin, 2018; Kirby & Laczko, 2017; Klimecki et al., 2014).

FI The FI involved a guided visualization of different aspects of the face, focusing on specific regions (e.g., shape and color of eyes). First, students were instructed to visualize their own face, then move towards visualizing aspects of another students’ face. Similar focused imagery meditation has been used as a control condition when assessing the effects of compassion-based meditations in previous studies (Kirby & Baldwin, 2018; Kirby & Laczko, 2017; Klimecki et al., 2014).

Bullying Videos

The bullying videos used in the current study were four short (15–25 s) bullying scenes portraying girls and boys close in age to the adolescent participants, all depicting face-to-face peer bullying (i.e., bystanders present) with elements of social, verbal, and physical aggression. Specifically, two of the scenes depicted bullying towards a girl (i.e., making fun of the victimized girl, and throwing a piece of paper towards a victimized girl), while the other two scenes depicted bullying towards a boy (i.e., making fun of the boy being victimized, and pouring water on the victimized boy). These bullying clips were excerpts from youth-focused and educational movies for the use in a previous bullying bystander study (i.e., Steinvik et al., 2024) that involved two pilot studies to ensure the clips were realistic examples of bullying that would elicit empathic feelings. The first pilot study tested the face validity of these selections among 50 undergraduate psychology students (aged 17–25). The videos that were considered the most realistic examples of bullying and elicited a range of emotional responses were then selected. The second pilot study was conducted with a convenience sample of 30 adolescents (aged 13–17), with results confirming that the bullying scenarios were salient to adolescents and elicited empathic feelings.

Manipulation Checks and Measures of Affect

Three items were included to measure participants’ engagement with the audio-guided recordings. The first item measured the extent to which participants listened and followed the audio-guided instructions: “How closely did you listen to and follow the instructions in the guided audio recording?” The second item measured negative affect: “Listening to the recording made me feel upset, distressed, or worried,” and the third item measured positive affect: “Listening to the recording made me feel warmth, kindness, or friendliness.” Adolescent responded to each item using a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very).

Video Outcome Measures

Empathic Distress and Anger

Two items each measured empathic distress (e.g., “As a witness to this incident, I would feel worried and upset”) and empathic anger (e.g., “As a witness to this incident, I would feel outraged because of what was happening to the person being victimized”) in response to each bullying video (see Appendix for all items). Participants rated their agreement with each item on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very). Items were drawn from previous studies of empathic distress (e.g., Batson et al., 1987; Davis, 1983) and from the Trait Empathic Anger Scale (Vitaglione & Barnett, 2003). The same items were used to measure empathic distress and anger in a previous bystander study (i.e., Steinvik et al., 2024). All 8 relevant items across the four videos (2 items per video for each of empathic distress and empathic anger) were averaged, with higher scores indicating higher levels of empathic distress or empathic anger; Cronbach’s α = 0.94 for each of the measures.

Compassion

Six items were included to measure compassion in response to each bullying video (see Appendix for all items). These items were previously used in Steinvik et al.’s (2024) bullying bystander study and were adapted from the Compassion to Others Scale (CS; Pommier et al., 2020) and the Compassionate Engagement Scale (Gilbert et al., 2017). The adaptations involved altering items from more general compassion responses to compassion specifically experienced when witnessing someone being victimized. Consistent with the conceptualization of compassion as characterized by mutually interdependent abilities, two items measured engagement/distress tolerance (e.g., “As a witness to this incident, I would think about how the person being victimized is feeling), two items measured concern/kindness (e.g., “As a witness to this incident, I would feel concerned because of what was happening to the person being victimized”), and two items measured non-judgement/common humanity (e.g., “As a witness to this incident, I would think the person [or people] who did the bullying did a bad thing, but may not be a bad person [or bad people]”). Participants responded to each item using a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very). A composite compassion score was calculated by first reversing some items and then averaging the 24 compassion items (6 items per video), with a higher score indicating more compassion; Cronbach’s α = 0.91.

Passive Bystanding, Aggressive Defending, and Prosocial Defending

Following each of the four bullying videos, adolescents reported their intended responses of passivity (3 items; e.g., “As a witness to this incident, I would act as if nothing has happened”), aggressive defending (3 items; e.g., “As a witness to this incident, I would take revenge on the person doing the bullying”), and prosocial defending (3 items; e.g., “As a witness to this incident, I would encourage the person being victimized to report the bullying to the adults in charge”) (see Appendix for all items). Participants responded on a 5-point scale (1 = not likely at all, 5 = very likely). These items were drawn from previous bullying bystander research (Pronk et al., 2013; Salmivalli et al., 1996), and the same items were used in Steinvik et al.’s (under review) study. Total passivity, aggressive defending, and prosocial defending scores were calculated by averaging the relevant 12 responses across the four videos (3 items per video), Cronbach α = 0.94 for passivity, 0.91 for aggressive defending, and 0.93 for prosocial defending.

Personal Experience with Bullying and Victimization

As previous research has shown that past experiences with bullying are associated with bystander responses to bullying (Bussey et al., 2020; Lambe & Craig, 2020), we measured personal experience of bullying and victimization to ensure that the randomization process resulted in three comparable groups (i.e., EM, CM, FI). After reading a brief definition of bullyingFootnote 1 adapted from Olweus (1994), and used in previous studies (e.g., Callaghan et al., 2019), two items were used to measure how often in the past few months students had “bullied other students” and “been the victim of bullying” on a 5-point rating scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very often/several times a week).

Results

Missing Data and Preliminary Analyses

Small amounts of item level data for the dependent variables were missing (range 0 to 0.90%) completely at random (Little’s MCAR test: χ2[75] = 27.26, p = 1.000) and not systematically related to other scores in the study. Expectation Maximization [EM] was therefore used to estimate missing data points to maintain all 110 participants. In addition, given that gender, age, and past experiences with bullying are associated with bystander responses to bullying (Bussey et al., 2020; Lambe & Craig, 2020), we conducted analyses to compare participant’s gender, age, and past experiences with bullying, across the conditions (EM, CM, FI). There was no difference in the proportions of boys/girls in each group, χ2(2) = 0.02, p= 0.992. The three groups also did not differ in age and level of past experiences of bullying others or being bullied (see Table 1 for means, SDs, and results of ANOVAs).

Manipulation Checks

Three univariate ANOVAs were used to compare engagement and affect in response to the EM, CM, and FI conditions to check the experimental manipulations (see Table 1 for means and SDs). Conditions did not significantly differ in terms of participants’ reported tendency to listen to and follow the audio-guided instructions, F(2, 107) = 0.64, p = 0.531, ηp2 = 0.01. The results were mixed for H1 regarding group differences in affect. There was no condition difference in positive affect following the visualization exercises, F(2, 107) = 0.30, p = 0.745, ηp2 = 0.01. However, there was a difference in negative affect following the visualization exercises between the conditions, F(2, 107) = 3.36, p = 0.038, ηp2 = 0.06. Follow-up pairwise comparisons indicated a higher level of negative affect in the EM compared to the CM (p = 0.025) and the FI (p = 0.029) groups, but no significant difference between the CM and FI groups (see Table 1 for means and SDs).

Comparison of Outcomes for Condition

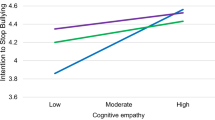

Six ANOVAs were used to compare the three conditions (EM, CM, FI) on the primary outcomes (see Table 1 for means, SDs, and results of ANOVAs). Two differences were found between conditions—empathic distress and empathic anger. Post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that adolescents in the CM group reported less empathic distress in response to the videos compared to adolescents in the EM and FI groups (p = 0.021 and p = 0.017, respectively), as well as less empathic anger compared to the EM and FI groups (p = 0.034, p = 0.001). The conditions did not differ in compassion or the three measures of bystander intentions.

Discussion

This experiment examined the differential effects of an audio-guided 10-min empathy [EM] and compassion [CM] visualization meditation exercise on adolescents’ (1) empathic distress, empathic anger, and compassion and (2) intended bystander behaviors (i.e., passive bystanding, aggressive defending, and prosocial defending) in response to viewing video clips of bullying. A focused imagery visualization control condition [FI] was also included. Our broader purpose was to understand whether bystander interventions may benefit from including a short empathy or compassion meditation exercise to improve their effectiveness. It was predicted that participants in the CM, relative to the EM and FI, would be lower in empathic distress and empathic anger, passive bystanding, and aggressive defending, but higher on compassion and prosocial defending, and that participants in the EM, relative to the FI group, will be higher on all outcome measures. This was only partially supported.

As predicted, adolescents in the CM group reported less empathic distress (H2a) and empathic anger (H2b) in response to the bullying videos than the EM and FI groups. However, contrary to predictions, there were no further differential effects between the three visualization conditions on responses to the bullying videos, nor were there any differences between the EM and FI groups on adolescents’ responses to the bullying videos. As we did not find evidence suggesting any benefits in adolescents’ bystander intentions from including a short empathy or compassion exercise, the findings of this initial experiment emphasize the need for further study and other possible strategies for increasing adolescents’ compassion for peers who are victimized by bullying.

Differences Between the Conditions

Consistent with the expected effect of the manipulation, participants reported more negative affect (i.e., upset, distressed, and worried) following the EM exercise, compared to the CM and FI exercises. Relatedly, as predicted, the CM participants reported less empathic distress and anger in response to the bullying videos than the EM and FI participants. These findings are consistent with theory and research (Klimecki et al., 2014; Stevens & Taber, 2021; Weng et al., 2017), indicating that compassion-based meditations can facilitate distress tolerance and may therefore act as an emotion regulation strategy in response to empathic emotions (Hofmann et al., 2011; Kirby et al., 2017; Luberto et al., 2018). In contrast, research indicates that a focus on empathy alone can lead to increased negative emotions, which may enhance a focus on one’s own negative feelings, resulting in empathic distress, rather than a focus on the person needing support (Klimecki et al., 2014; Singer & Klimecki, 2014). Critically, emerging research on defending against bullying has shown that a higher level of empathic distress is associated with more passivity/avoidance (Rieffe & Camodeca, 2016; Steinvik et al., 2023). However, although the EM resulted in more empathic distress than the CM, there were no differences between the EM and the FI control condition in this study. Taken together, the differential effects of empathy and compassion activation on emotional responses to videos of bullying in the current study advance research on compassion and empathy interventions in children and adolescents (for a review, see Perkins et al., 2022), by providing the first evidence to show that even brief empathy and compassion activation can be effective for altering emotions in the context of bullying.

However, the difference between conditions did not extend to participants’ positive affect before the bullying videos, compassionate responding to the videos, or intended bystander behaviors (i.e., passivity, aggressive defending, and prosocial defending). Although brief empathy induction has been shown to increase the likelihood of reporting cyberbullying acts (i.e., prosocial defending) (Barlińska et al., 2018), longer empathy and compassion meditation practice might be needed for improvements in prosocial intentions and behaviors in the context of face-to-face bullying. This view is consistent with Luberto et al.’s (2018) meta-analytic review that examined the effects of compassion-based meditation practice on prosocial emotions and behaviors, and studies showing that compassion-based meditation training ranging from 1 day to 8 to 12 weeks can enhance compassion and prosocial behaviors in adults (Hofmann et al., 2011; Kirby et al., 2017; Weng et al., 2017). Thus, while the current findings indicate that brief empathy and compassion activation can influence adolescents’ empathic emotions, future research is needed to understand how empathy and compassion interventions can enhance prosocial intentions and behavior in children and adolescents.

A possible reason for the lack of condition difference in compassion or intended defending behaviors could be that, even by adolescence, these emotional and behavioral responses are founded in a history of experience that requires more than a short visualization exercise to modify. As suggested in decades of developmental research, emotional responses emerge from a history of repeated and actual transactions with demands and stressors (Frijda, 1988). Changing deeply ingrained emotional and behavioral responses can be difficult because they are founded in a long history of experiences and responses that must be replaced with new beliefs and attitudes, as well as practice using new complex control mechanisms (Thompson, 1991). Specifically for compassion, the lack of differences between conditions in the present study could be because a general level of compassion for others has become rather ingrained even as early as adolescence. Compassion is not only an outcome of a specific experience or emotional state, but also is the by-product of many experiences and long-standing attitudes (Gilbert, 2015; Hofmann et al., 2011). Consistent with the view that compassion takes considerable time and practice to develop, longer compassion exercises may successfully influence intentions and behaviors in adolescents. In contrast, empathic emotions (i.e., empathic distress and anger) are in the moment and specific to a particular interaction, experience, or context. Therefore, they may be more influenced by context and the use of single and short compassion exercises as demonstrated in the current study.

It is also possible that adolescents’ attitudes and intentions may be even more resistant to change or, alternatively, adolescents may be more resistant to engage with intervention activities at school. Consistent with this possibility, students decline in motivation and school engagement (behavioral, emotional, and cognitive) during adolescence (Raine et al., 2023; Skinner & Raine, 2023; Skinner et al., 1998), while peers become increasingly important for attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. Adolescence is characterized by a drive to “fit in” with peers, in which the social influence from friends can surpass influence from parents and teachers (Flynn et al., 2017; Ryan, 2000). It may therefore be that, during adolescence, more comprehensive empathy- and compassion-based interventions are needed to influence compassion and subsequent behavioral responses, especially toward their peers.

Limitations and Considerations for Future Research

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, the visualization exercises and self-report scales used in the present study are vulnerable to responder bias, and it is unclear how adolescents would respond to empathy- and compassion-based visualization exercises and bullying in real life. It also remains unknown whether there was any change in affect, empathy, or compassion pre and post the visualization exercises. Despite using an experimental between-groups design comparing the effects of the visualization exercises, we did not include any pre-measures, mainly to prevent response biases to the visualization exercises. It is therefore unknown whether the conditions (i.e., EM, CM, FI) had any common effects on adolescents’ responses to the bullying videos. To overcome this limitation, future studies should implement a repeated measures design collecting data at pre-time, possibly also separate from the experimental manipulation (visualization exercises), to control for response bias. To expand the validity of measures, future research would also benefit from using measures beyond self-report, including observational and physiological measures to capture state-like emotional data (e.g., heart rate variability) shown to indicate compassion and prosocial behavior in previous studies (Bornemann et al., 2016; Di Bello et al., 2020; Stellar et al., 2015).

Additionally, to better understand how to design more comprehensive empathy and compassion interventions to target prosocial defending, future research must account for possible mediators and moderators of the effects of empathy and compassion exercises on bystander behavior. For instance, self-efficacy, moral disengagement, and school/classroom norms are significant correlates of bystander defending (Bussey et al., 2020; Peets et al., 2015), and may influence the effects of empathy and compassion interventions. Research also indicates that disruptions in early caregiving experiences increase the likelihood of later difficulties with empathy, compassion, and prosocial behavior (Amari et al., 2022; Martins et al., 2022). Relatedly, research has shown that young adults with high levels of self-criticism or fears of compassion do not respond well to compassion-based exercises (Gilbert & Mascaro, 2017).

Finally, although our current sample had a diverse ethic/racial background, the majority was white Australian adolescents identifying as either female or male. As minority groups (e.g., sexual, ethnic, individuals with disabilities) are at higher risk of victimization (Xu et al., 2020), it is also critical to understand how to influence prosocial bystander responses when different ethnic-cultural groups and minorities are victimized by bullying. Given that empathic responses are influenced by external variables, including group membership (Vanman, 2016) and target race (Han, 2018), an important future research question is whether empathy- and compassion-based interventions can be used to improve prosocial defending of victimized peers, regardless of group differences.

Implications and Conclusion

This was the first study to compare the effects of brief stand-alone empathy (i.e., EM) and compassion (i.e., CM) visualizations on a range of emotional and behavioral responses to viewing video clips of bullying. As predicted, we found that the EM resulted in higher levels of negative affect compared to the CM and FI. Critically, negative affect can activate fight-flight-freeze responses, which may inhibit constructive thinking and trigger more avoidance-based behaviors, such as passivity (Fredrickson, 2001; Fredrickson et al., 2008; Porges, 2007; Singer & Klimecki, 2014). Empathy interventions might therefore benefit from including strategies to tolerate negative affect while also enhancing positive affect, which facilitates feelings of safety important for other-oriented feelings of concern and prosocial social engagement behaviors (Porges, 2017; Stevens & Taber, 2021). Although the compassion-based meditation [CM] was designed to enhance participants’ positive affect, there was no significant difference in positive affect between the CM and EM, indicating that longer compassion meditation sessions might be needed to influence adolescents’ positive affect.

However, consistent with the intent of compassion-based interventions to enhance distress tolerance and reduce reactivity and anger, the CM participants reported less empathic distress and anger compared to the EM and FI participants. Hence, even short compassion-based meditation interventions may be useful for improving distress tolerance; however, more research is needed to understand the role of compassion interventions in improving long-term distress tolerance in adolescents. Despite the current study effects on negative emotions, there was no effect of the experimental conditions on the outcome of compassionate responding or behavioral intentions to defend or remain passive. As we did not find evidence suggesting any major benefit of a brief stand-alone empathy or compassion exercise for adolescents’ intended bystander behaviors, further research is needed to determine if more comprehensive empathy and compassion exercises, with repeated sessions and practice, might be of benefit.

With emerging awareness that empathy and compassion can predict distinctive responses to witnessing the distress or unfair treatment of others, ranging from passivity to aggressive and prosocial actions (Singer & Klimecki, 2014; Steinvik et al., 2023; Vitaglione & Barnett, 2003), it is critical to understand how to successfully incorporate empathy and compassion interventions in schools to increase the likelihood of prosocial defending behaviors among adolescents when they witness peer bullying. Given that empathy interventions alone may inadvertently increase adolescents’ distress and therefore subsequent avoidance in response to witnessing victimized peers, further research is needed to understand the extent to which compassion-based interventions can enhance adolescents’ distress tolerance and capacity to respond to difficult empathic emotions. In addition, with research indicating that compassion training can reduce intended and actual punishment of transgressors (Condon & DeSteno, 2011; McCall et al., 2014), consistent with compassion as characterized by a non-judgemental view of others, future research is needed to examine whether longer compassion training can reduce aggressive responses toward peers who bully others, to prevent escalated aggression and conflict, and increase the use of prosocial constructive defending.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Notes

The definition provided read: “We say a student is being bullied when another student or group of students say or do nasty and unpleasant things to him or her. It is also bullying when a student is teased repeatedly in a way he or she does not like or when he or she is deliberately left out of things. But it is not bullying when two students of about the same strength or power argue or fight. It is also not bullying when the teasing is done in a friendly and playful way.”.

References

Amari, N., Martin, T., Mahoney, A., Peacock, S., Stewart, J., & Alford, E. A. (2022). Exploring the relationship between compassion and attachment in individuals with mental health difficulties: A systematic review. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-022-09573-4

Arseneault, L. (2017). The long-term impact of bullying victimization on mental health. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 27–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20399

Ashar, Y. K., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Yarkoni, T., Sills, J., Halifax, J., Dimidjian, S., & Wager, T. D. (2016). Effects of compassion meditation on a psychological model of charitable donation. Emotion, 16(5), 691–705. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000119

Barlińska, J., Szuster, A., & Winiewski, M. (2018). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 799. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00799

Batson, C. D., Fultz, J., & Schoenrade, P. A. (1987). Distress and empathy: Two qualitatively distinct vicarious emotions with different motivational consequences. Journal of Personality, 55(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1987.tb00426.x

Bornemann, B., Kok, B. E., Boeckler, A., & Singer, T. (2016). Helping from the heart: Voluntary upregulation of heart rate variability predicts altruistic behavior. Biological Psychology, 119, 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2016.07.004

Buffone, A. E. K., & Poulin, M. J. (2014). Empathy, target distress, and neurohormone genes interact to predict aggression for others-even without provocation. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(11), 1406–1422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214549320

Bussey, K., Luo, A., Fitzpatrick, S., & Allison, K. (2020). Defending victims of cyberbullying: The role of self-efficacy and moral disengagement. Journal of School Psychology, 78, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.11.006

Callaghan, M., Kelly, C., & Molcho, M. (2019). Bullying and bystander behaviour and health outcomes among adolescents in Ireland. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 73(5), 416–416. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2018-211350

Cefai, C., Bartolo, P. A., Cavioni, V., & Downes, P. (2018). Strengthening social and emotional education as a core curricular area across the EU: A review of the international evidence (NESET II report). European Union. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar//handle/123456789/29098

Condon, P., Desbordes, G., Miller, W. B., & DeSteno, D. (2013). Meditation increases compassionate responses to suffering. Psychological Science, 24(10), 2125–2127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613485603

Condon, P., & DeSteno, D. (2011). Compassion for one reduces punishment for another. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(3), 698–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.11.016

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

Di Bello, M., Carnevali, L., Petrocchi, N., Thayer, J. F., Gilbert, P., & Ottaviani, C. (2020). The compassionate vagus: A meta-analysis on the connection between compassion and heart rate variability. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 116, 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.06.016

Flynn, H. K., Felmlee, D. H., & Conger, R. D. (2017). The social context of adolescent friendships: Parents, peers, and romantic partners. Youth & Society, 49(5), 679–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X145599

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. (2008). Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1045–1062. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013262

Frey, K. S., Pearson, C. R., & Cohen, D. (2015). Revenge is seductive, if not sweet: Why friends matter for prevention efforts. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 37, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.08.002

Frijda, N. H. (1988). The laws of emotion. American Psychologist, 43, 349–358. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.43.5.349

Gaffney, H., Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2019). Evaluating the effectiveness of school-bullying prevention programs: An updated meta-analytical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 111–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.001

Gilbert, P., Catarino, F., Duarte, C., Matos, M., Kolts, R., Stubbs, J., Ceresatto, L., Duarte, J., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Basran, J. (2017). The development of compassionate engagement and action scales for self and others. Journal of Compassionate Health Care, 4(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40639-017-0033-3

Gilbert, P., & Mascaro, J. (2017). Compassion: Fears, blocks, and resistances: An evolutionary investigation. In E. M. Seppälä, E. Simon-Thomas, S. L. Brown, M. C. Worline, C. D. Cameron, & J. R. Doty (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of compassion science 399–420 (p. 2017). Gilbert et al.: Oxford University Press.

Gilbert, P. (2015). The evolution and social dynamics of compassion. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(6), 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12176

Gummerum, M., Van Dillen, L. F., Van Dijk, E., & López-Pérez, B. (2016). Costly third-party interventions: The role of incidental anger and attention focus in punishment of the perpetrator and compensation of the victim. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 65, 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2016.04.004

Han, S. (2018). Neurocognitive basis of racial ingroup bias in empathy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(5), 400–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2018.02.013

Hawkins, L. D., Pepler, D. J., & Craig, W. M. (2001). Naturalistic observations of peer interventions in bullying. Social Development, 10(4), 512–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00178

Hoffman, M. L. (2001). Empathy and moral development: Implications for caring and justice. U.K., Cambridge University Press.

Hofmann, S. G., Grossman, P., & Hinton, D. E. (2011). Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: Potential for psychological interventions. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1126–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.003

Hutcherson, C. A., Seppala, E. M., & Gross, J. J. (2008). Loving-kindness meditation increases social connectedness. Emotion, 8(5), 720–724. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013237

Jung, J., & Schröder-Abé, M. (2019). Prosocial behavior as a protective factor against peers’ acceptance of aggression in the development of aggressive behavior in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 74, 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.06.002

Juvonen, J., & Galván, A. (2008). Peer influence in involuntary social groups: Lessons from research on bullying. In M. J. Prinstein & K. A. Dodge (Eds.), Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents (pp. 225–244). The Guilford Press.

Kirby, J. N., & Baldwin, S. (2018). A randomized micro-trial of a loving-kindness meditation to help parents respond to difficult child behavior vignettes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 1614–1628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0989-9

Kirby, J. N., & Laczko, D. (2017). A randomized micro-trial of a loving-kindness meditation for young adults living at home with their parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26, 1888–1899. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0692-x

Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Steindl, S. R. (2017). A meta-analysis of compassion-based interventions: Current state of knowledge and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 48(6), 778–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.06.003

Klimecki, O. M., Leiberg, S., Ricard, M., & Singer, T. (2014). Differential pattern of functional brain plasticity after compassion and empathy training. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(6), 873–879. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nst060

Klimecki, O. M., Vuilleumier, P., & Sander, D. (2016). The impact of emotions and empathy-related traits on punishment behavior: Introduction and validation of the inequality game. PLoS ONE, 11(3), e0151028. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0151028

Lambe, L. J., Cioppa, V. D., Hong, I. K., & Craig, W. M. (2019). Standing up to bullying: A social ecological review of peer defending in offline and online contexts. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.05.007

Lambe, L. J., & Craig, W. M. (2020). Peer defending as a multidimensional behavior: Development and validation of the Defending Behaviors Scale. Journal of School Psychology, 78, 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.12.001

Luberto, C. M., Shinday, N., Song, R., Philpotts, L. L., Park, E. R., Fricchione, G. L., & Yeh, G. Y. (2018). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of meditation on empathy, compassion, and prosocial behaviors. Mindfulness, 9, 708–724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0841-8

Martins, M. C., Santos, C., Fernandes, M., & Veríssimo, M. (2022). Attachment and the development of prosocial behavior in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Children, 9(6), 874. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060874

McCall, C., Steinbeis, N., Ricard, M., & Singer, T. (2014). Compassion meditators show less anger, less punishment, and more compensation of victims in response to fairness violations. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 424–424. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00424

Menesini, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2017). Bullying in schools: The state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(1), 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2017.1279740

Olweus, D. (1994). Bullying at school: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35(7), 1171–1190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01229.x

Oveis, C., Horberg, E. J., & Keltner, D. (2010). Compassion, pride, and social intuitions of self-other similarity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(4), 618–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017628

Peets, K., Pöyhönen, V., Juvonen, J., & Salmivalli, C. (2015). Classroom norms of bullying alter the degree to which children defend in response to their affective empathy and power. Developmental Psychology, 51(7), 913. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039287

Perkins, N., Sehmbi, T., & Smith, P. (2022). Effects of kindness-and compassion-based meditation on wellbeing, prosociality, and cognitive functioning in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Mindfulness, 13(9), 2103–2127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01925-4

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2012.12087375

Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Tóth-Király, I. (2020). The development and validation of the Compassion Scale. Assessment, 27(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191119874108

Porges, S. W. (2017). Vagal pathways: Portals to compassion In. In E. M. Seppälä, E. Simon-Thomas, S. L. Brown, M. C. Worline, C. D. Cameron, & J. R. Doty (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of compassion science (pp. 198–202). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190464684.013.15

Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 116–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009

Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Thornberg, R. (2017). Getting angry matters: Going beyond perspective taking and empathic concern to understand bystanders’ behavior in bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 61, 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.09.011

Pronk, J., Goossens, F. A., Olthof, T., De Mey, L., & Willemen, A. M. (2013). Children’s intervention strategies in situations of victimization by bullying: Social cognitions of outsiders versus defenders. Journal of School Psychology, 51(6), 669–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.09.002

Raine, K. E., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Skinner, E. A. (2023). The role of coping in processes of resilience: The sample case of academic coping during late childhood and early adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457942300072X

Reijntjes, A., Vermande, M., Olthof, T., Goossens, F. A., Aleva, L., & van der Meulen, M. (2016). Defending victimized peers: Opposing the bully, supporting the victim, or both? Aggressive Behavior, 42(6), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21653

Rieffe, C., & Camodeca, M. (2016). Empathy in adolescence: Relations with emotion awareness and social roles. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 34(3), 340–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12133

Ryan, A. M. (2000). Peer groups as a context for the socialization of adolescents’ motivation, engagement, and achievement in school. Educational Psychologist, 35(2), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3502_4

Sainio, M., Veenstra, R., Huitsing, G., & Salmivalli, C. (2010). Victims and their defenders: A dyadic approach. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(2), 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025410378068

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:13.0.CO;2-T

Salzberg, S., & Kabat-Zinn, J. (2004). Lovingkindness: The revolutionary art of happiness. Shambhala Publications.

Shonin, E., Van Gordon, W., Compare, A., Zangeneh, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Buddhist-derived loving-kindness and compassion meditation for the treatment of psychopathology: A systematic review. Mindfulness, 6, 1161–1180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0368-1

Singer, T., & Klimecki, O. M. (2014). Empathy and compassion. Current Biology, 24(18), R875–R878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.054

Skinner, E. A., & Raine, K. E. (2023). Fostering the development of academic coping: A multi-level systems perspective. In E. A. Skinner & M. J. Zimmer-Gembeck (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of the development of coping. Cambridge University Press.

Skinner, E. A., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Connell, J. P., Eccles, J. S., & Wellborn, J. G. (1998). Individual differences and the development of perceived control. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 63(2/3), i–231. https://doi.org/10.2307/1166220

Sprecher, S., & Fehr, B. (2005). Compassionate love for close others and humanity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22(5), 629–651. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407505056439

Steinvik, H. R., Duffy, A. L., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2023). Bystanders’ responses to witnessing cyberbullying: The role of empathic distress, empathic anger, and compassion. International Journal of Bullying Prevention. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-023-00164-y

Steinvik, H. R., Duffy, A. L., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2024). Adolescents’ compassion is distinctly associated with more prosocial and less aggressive defending against bullying when considering multiple empathic emotions and costs. [Manuscript submitted for publication].

Stellar, J. E., Cohen, A., Oveis, C., & Keltner, D. (2015). Affective and physiological responses to the suffering of others: Compassion and vagal activity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(4), 572. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000010

Stevens, F., & Taber, K. (2021). The neuroscience of empathy and compassion in pro-social behavior. Neuropsychologia, 159, 107925–107925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2021.107925

Strauss, C., Lever Taylor, B., Gu, J., Kuyken, W., Baer, R., Jones, F., & Cavanagh, K. (2016). What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clinical Psychology Review, 47, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.004

Thompson, R. A. (1991). Emotional regulation and emotional development. Educational Psychology Review, 3, 269–307. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23359228

Ttofi, M. M., Bowes, L., Farrington, D. P., & Lösel, F. (2014). Protective factors interrupting the continuity from school bullying to later internalizing and externalizing problems: A systematic review of prospective longitudinal studies. Journal of School Violence, 13(1), 5–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2013.857345

Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7(1), 27–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1

van Doorn, J., Zeelenberg, M., Breugelmans, S. M., Berger, S., & Okimoto, T. G. (2018). Prosocial consequences of third-party anger. Theory and Decision, 84(4), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-017-9652-6

Vanman, E. J. (2016). The role of empathy in intergroup relations. Current Opinion in Psychology, 11, 59–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.06.007

Vitaglione, G. D., & Barnett, M. A. (2003). Assessing a new dimension of empathy: Empathic anger as a predictor of helping and punishing desires. Motivation and Emotion, 27(4), 301–325. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026231622102

Weng, H. Y., Schuyler, B., & Davidson, R. J. (2017). The impact of compassion meditation training on the brain and prosocial behavior. In E. M. Seppälä, E. Simon-Thomas, S. L. Brown, M. C. Worline, C. D. Cameron, & J. R. Doty (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of compassion science (pp. 133–146). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190464684.013.11

Weng, H. Y., Fox, A. S., Hessenthaler, H. C., Stodola, D. E., & Davidson, R. J. (2015). The role of compassion in altruistic helping and punishment behavior. PLoS ONE, 10(12), e0143794–e0143794. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143794

Weng, H. Y., Lapate, R. C., Stodola, D. E., Rogers, G. M., & Davidson, R. J. (2018). Visual attention to suffering after compassion training is associated with decreased amygdala responses. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 771. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00771

Xu, M., Macrynikola, N., Waseem, M., & Miranda, R. (2020). Racial and ethnic differences in bullying: Review and implications for intervention. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 50, 101340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.101340

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions This work was supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Stipend Scholarship for higher degree research (HDR) candidates.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

In conducting this research study, we have complied with APA guidelines for the ethical conduct of research. Human Research Ethics Approval for this study was obtained from Griffith University (Australia).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from the school principal, parents/legal guardians, and participants. Participants were also informed that it was voluntary to complete the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

We can confirm that this manuscript is not under review at any other journal or outlet, and all authors have agreed to the content of this article and the author order. No previous papers have been published using any of the data included here.

Appendix

Appendix

Items for empathic distress, empathic anger, and compassion

As a witness to this incident, I would:

-

1.

Feel worried and upset (empathic distress)

-

2.

Feel concerned because of what was happeing to the person being victimised (compassion: concern vs indifference)

-

3.

Feel angry because of what was happening to the person being victimised (empathic anger)

-

4.

Feel not much of anything (reversed; compassion: engagement vs disengagement)

-

5.

Feel overwhelmed (empathic distress)

-

6.

Feel outraged because of what was happening to the person being victimised (empathic anger)

-

7.

Think about how the person being victimised was feeling (compassion: engagement vs disengagement)

-

8.

Not care about the person being victimised (reversed; compassion: concern vs indifference)

-

9.

Think the person (or people) who was bullying did a bad thing but may not be a bad person (or bad people) (compassion: non-judgement/common humanity)

-

10.

Try to understand why someone would bully like that (compassion: non-judgement/common humanity)

Response options: 1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = somewhat, 4 = quite, 5 = very.

Items for bystander intentions

As a witness to this incident, I would:

-

1.

Ignore the situation (passive bystanding)

-

2.

Try to comfort the person being victimized (prosocial defending)

-

3.

Attack or threaten the person doing the bullying (aggressive defending)

-

4.

Act as if nothing has happened (passive bystanding)

-

5.

Encourage the person being victimized to report the bullying to the people in charge (e.g., teacher) (prosocial defending)

-

6.

Gossip about the person doing the bullying to others (e.g., say mean things abou the person doing the bullying (aggressive defending)

-

7.

Not get involved (i.e., mind my own business) (passive bystanding)

-

8.

Try to sort out the problem by talking to th people involved in the bullying (prosocial defending)

-

9.

Take revenge on the person doing the bullying (e.g., call the person doing the bullying names) (aggressive defending)

Response options: 1 = not at all likely, 2 = a little likely, 3 = somewhat likely, 4 = quite likely, 5 = very likely.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Steinvik, H.R., Duffy, A.L. & Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J. Can Empathy and Compassion Activation Affect Adolescents’ Empathic Responses, Compassion, and Behavioral Intentions When Witnessing Bullying?. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-024-00254-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-024-00254-5