Abstract

School principals may be well-placed to establish safe and affirming school climates for gender and sexuality diverse students by upholding zero-tolerance policies for homophobic, biphobic, and/or transphobic (HBT) bullying. Few qualitative investigations have examined how leaders are perceived, by those with vested interest, to be exercising their powers in this regard. Parents and caregivers (N = 16) completed a qualitative online questionnaire about their experiences navigating school responses to the HBT bullying of their child. Responses were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis. Findings indicate that principals were often either a first point of contact or an option for escalation. Intervention efforts were favourably appraised where empathy for the targeted student was accompanied by quick and decisive action. When this did not occur, participants described the injurious effects of inaction, prejudiced attitudes, and minimisation of the impact of non-physical bullying on both them and their child. We discuss implications for principals and schools with respect to the significant consequences of non-intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Bullying, whether based on actual or perceived gender and/or sexuality (GS) diversity, is prevalent in Australian high schools (i.e. Years 7–12; Ullman, 2021a). School bullying is a behaviour that causes physical, emotional, or social harm to targeted students. It is characterised by an imbalance of power, is reinforced by norms within the school and education system, and suggests an absence of effective responses by peers and adults (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), 2023).

The term gender and/or sexuality diverse (GSD) refers to any individual who stands outside of the categories of heterosexual and/or cisgendered, including those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual+, asexual, transgender, and/or queer (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023). A recent survey of Australian GSD young people, including 3850 high school students, revealed that in the preceding 12 months, 28.1% of participants had experienced sexuality or gender bias-driven verbal aggression at school (Hill et al., 2021). In the same timeframe, 8.6% and 6.7% of participants had experienced bias-driven sexual or physical aggression, respectively. Students who do not identify as GSD can also be targets of homophobic, biphobic, and/or transphobic (HBT) bullying, such as when they are perceived by their peers to defy normative gender roles or appearance (e.g., an athletic female targeted for being a lesbian; Brown et al., 2013).

While preventative measures are most desired to avert bullying, dependable intervention is an important component of a safe school climate for GS diversity (Swanson & Gettinger, 2016). Substantive research has focused on the frequency, methods, and predictors of staff intervention, primarily through quantitative survey methods. In a study with a convenience sample including 2376 Australian GSD high school students, of those who reported that homophobic remarks were made within earshot of staff (n = 1850), only 6.2% reported that staff always intervened, and only 5.2% reported consistent intervention where transphobic remarks were made in the presence of staff (n = 1174; Ullman, 2021a).

Additionally, relational bullying, the deliberate manipulation and damage of others’ peer relationships by means such as rumour spreading and purposeful social exclusion, is notoriously difficult for schools to address as detecting it requires contextual knowledge of students’ relationships (Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). Low rates of intervention can contribute to a school culture wherein HBT bullying can thrive because it is not explicitly condemned, bystander intervention is not normalised, and students are less likely to approach staff with concerns (Molina et al., 2023).

Bullying Intervention: The Role of School Principals

Compared to teachers and wellbeing staff, school principals have received less research attention for their role in bullying intervention. Researchers have primarily been concerned with the role of principals in establishing policy and procedures that contribute to the overall wellbeing of GSD students, and any secondary effects on intervention (Reyes-Rodríguez et al., 2021). Nonetheless, there is growing interest in the potential impact of principal involvement in the intervention of HBT bullying (Farrelly et al., 2017).

National frameworks for both student wellbeing (The Australian Student Wellbeing Framework; Education Services Australia Ltd, 2020) and principalship (The Principal Standard; Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, 2017) arguably provide a strong, albeit non-specific, justification for principals to work actively and collaboratively in bias-driven bullying intervention. This is especially true given the adverse effects of this form of bullying on the school attendance, educational attainment, mental health, and long-term overall health of targeted students (Moyano & Sánchez-Fuentes, 2020). A principal who accepts accountability for the school’s response to bullying of this nature can ensure that complaints are properly investigated, intervention is followed through, and a zero-tolerance stance is perceptible to students, parents, and teachers (Englehart, 2014). As with teachers, principals’ capacity to achieve a safe climate for GSD individuals is likely moderated in part by their own attitudes, knowledge, and priorities (Greytak & Kosciw, 2014; Payne & Smith, 2017); however, how, or if, principals are choosing to respond to incidences of HBT bullying in Australian high schools is unclear.

Conceptual Framework

An adaptation of Brofenbrenner’s (1977) social-ecological perspective on bullying positions students, educators, and families within a complex system of factors which can variously facilitate, disrupt, and wear the consequences of these behaviours (Espelage, 2014). The present study, methodologically, captures dynamics within the mesosystem of the social-ecological model of bullying, in that it relates to the interaction between families and school personnel, themselves both part of the microsystem (Espelage, 2014). Engagement between schools and families is an important part of the ecological system approach upon which whole-school anti-bullying efforts are based (Price & Green, 2016). However, in research about HBT bullying, the perspective of parent/caregivers is underutilised, potentially because some parents/caregivers may be unaware, or unsupportive, of their child’s GS diversity (Hill et al., 2021).

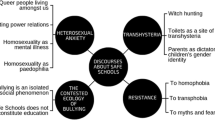

For HBT bullying specifically, the factors that impact such behaviours can be identified across the individual (e.g. GS diversity), microsystem (e.g. peer group norms), exosystem (e.g. community norms), and macrosystem (e.g. legal frameworks) levels (Newman & Fantus, 2015; Patel & Quan-Haase, 2022). The present study integrates literature on HBT bullying with Berdahl’s (2007) theory of sex-based harassment, adapting it for use in the context of GS diversity. HBT bullying is conceptualised as a means of policing “acceptable” GS identities and expression, which is abetted by the stratification of social status, based on these characteristics, within the school microsystem (Berdahl, 2007; Meyer, 2008). HBT bullying is incentivised in environments where there is an assumption that heterosexuality is inherently normal and natural compared with other forms of attraction and relationships (i.e. heteronormativity; Kitzinger, 2005) and where gender is considered a binary construct, determined by sex assigned at birth, with aspirational attributes tied to these classifications (i.e. cisnormativity; Stewart et al., 2022). Hetero/cisnormativity is driven by factors across the social-ecological systems but are commonly reinforced both implicitly (e.g. through the omission of GSD-related curriculum materials) and explicitly (e.g. through gendered uniform and hair policies) by the school microsystem (Ullman et al., 2023). HBT bullying, a form of gender-based harassment, can be a tool by which perpetrators protect or enhance their social status within this hierarchy of ideals (Berdahl, 2007; Meyer, 2008). Such is the social security afforded by conforming to these norms that being bullied for gender non-conformity, irrespective of actual GS identity, may lead to worse mental health outcomes than are elicited by general bullying (Swearer et al., 2008).

Given the ubiquity of hetero/cisnormativity, it is unsurprising that even well-intended educators may falter at identifying and addressing HBT bullying, especially if it is covert or relational in nature (McCabe et al., 2012). Principals may be uniquely positioned to instigate the disruption of these norms, especially as other staff have cited a lack of administrator support as a deterrent from addressing HBT bullying themselves (Meyer, 2008; Smith-Millman et al., 2019). Considering the lacunae in research regarding the role principals are playing in addressing HBT bullying in Australian high schools, the present qualitative study explored parent/caregivers’ experiences using the following research questions:

-

RQ1: How do parents report that principals have been involved with the management of HBT bullying, including by comparison to other staff?

-

RQ2: How do parents perceive the efficacy of principals at managing HBT bullying?

-

RQ3: What do parents want from principals with respect to the management of HBT bullying?

Methods

Design

An exploratory, qualitative, online questionnaire design was used. Participants were given the option to participate in a follow-up interview (results analysed separately). Given the sensitivity of the research topic, the qualitative questionnaire methodology was chosen to achieve a rich collection of data, while maintaining anonymity, and to increase participation amongst people who, owing to work and family commitments, may otherwise have limited opportunity to participate (Braun et al., 2020; Davey et al., 2019). This is a well-established methodology for complex and underrepresented topics, especially where the target sample is geographically dispersed (Clarke & Smith, 2015; Davey et al., 2019).

Data Collection

Ethics approval was granted by the first author’s institution’s ethics committee (protocol #205245). The study was hosted on Qualtrics from March to July 2023. Inclusion criteria were as follows: parent/caregivers of a student who currently attends, or has attended in the past 5 years, an Australian high school, and had experience with school staff involvement, of any kind, in the HBT bullying of their child.

Purposive sampling was employed to reach marginalised and niche populations who create strong online communities (Trau et al., 2012). Participants were recruited using a snowballing approach via posts on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter. Recruiting parents and members of the GSD population is challenging (Tully et al., 2021). Numerous relevant national- and community-based organisations and service providers advertised the study, and with permission, the questionnaire was also shared in online groups of GSD parents and parents with GSD children. Participants had the option to enter a draw to win one of three $50 gift cards.

Demographic information about the participants, their child, and their school(s) was collected. Participants then completed one of two forms of the questionnaire, depending on whether or not a member of the principal team was involved with handling the bullying issue. Any principal, acting principal, deputy/vice principal, or assistant principal was considered a member of the principal team.

Both forms of the questionnaire included open-ended questions about the nature of the bullying, how contact was made between the participant and the school, the nature of the school’s response, participants’ degree of satisfaction with the response, what participants would like to see done to prevent systemic HBT bullying problems in schools, and anything else they would like to convey. Participants who indicated that no member of the principal team was involved were additionally asked whether they thought principal involvement would have altered the outcome. Where a principal was involved, participants were asked how involved the principal was by comparison to other staff. There were seven open-ended questions in both versions of the questionnaire.

Participants

A total of 362 responses were exported from Qualtrics. Of these, 129 incomplete forms with no qualitative answers were removed. A protocol was developed to identify bot and malicious responses (see Supplementary Material), removing an additional 217 responses. During a follow-up interview with one participant (P4), it emerged that her child was in Year 6 (i.e. not in high school), contrary to what was indicated in the questionnaire response. This response was included in the study nonetheless given that, from an ethical standpoint, excluding a participant who entrusted the researchers with their personal experience did not seem warranted. In addition, the student attended a combined primary and high school with a principal who oversees both, and high school students perpetrated. Finally, since this study did not aspire to generalisability or saturation (Braun & Clarke, 2022), no inherent harms were associated with the inclusion.

The final sample consisted of 16 participants, from six Australian states, consistent with sample size guidelines for participant-generated textual research designed for thematic analysis (Clarke & Braun, 2013) and previous qualitative questionnaire studies with comparably niche populations (Turner & Coyle, 2000). Included responses ranged from approximately 70–790 words, with an average of 274 words per response (see Table 1 for demographic information on parents/caregivers, the targeted students, and implicated schools and Table 2 for basic details of bullying descriptions reported).

Data Analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) was employed by the first author (Braun & Clarke, 2022). An inductive, critical-realist approach was applied to the analyses, acknowledging that participants’ experiences of reality are mediated by their language and culture, albeit that reality exists independently of how it is observed and understood (Braun & Clarke, 2022; Haigh et al., 2019). Familiarisation began with the extraction of valid questionnaire forms from the initial participant pool, and the final data were thereafter read and re-read as a set. Initial coding was completed by hand and then refined using NVivo software. Coding was done at the semantic level to “stay close” to participants’ experiences (Braun & Clarke, 2022, p. 57). RTA privileges analytic depth and richness over coding reliability (Braun & Clarke, 2022, p. 241). Accordingly, no inter-rater reliability procedures were conducted. However, the data, codes, and themes were discussed by the researchers to ensure rigour. Initial themes were constructed using the coded data, and these were mapped, reviewed, and refined with reference to the coded data and the entire data set to ensure a good fit. Minor spelling and grammatical corrections have been made to participants’ responses for readability.

Results

Four themes were generated: (1) Whose role is it anyway?, (2) Is it “really” an issue?, (3) We alone bear the consequences, and (4) Beyond bullying—The whole-school approach. To contextualise the discussion within these themes, the nature of the bullying reported by parents is presented first.

Overview of the HBT Bullying

The responses reflected a range of HBT bullying experiences. Participants referred to experiences of both online and in-person bullying, often both together, as well as some combination of verbal, social, and/or physical bullying.

The bullying reported most often involved the use of slurs and taunting, in person and online, which sometimes conflated gender, sex, and sexuality. This type of bullying included typical name calling and humiliation based on the target’s actual or perceived identity (e.g. “fag”, “tranny”, “chick with a dick”; e.g. P3, P9, P12), or the identity of their parent/caregiver (i.e. for having same-sex parents; P6, P15). This form of overtly HBT aggression was directed to GSD students and those who did not, at least to the participants’ knowledge, identify as GSD. In these cases, the bullying policed normative family structures and gender expression (e.g. a male target with long hair and ear piercings). Verbal bullying also included bullying specifically targeted at GSD individuals, such as deadnaming, purposeful misgendering, teasing for using gender-neutral toilets, and outing the target to their peers.

Relational or social bullying was commonly reported, manifesting as social exclusion and rumour spreading. Physical aggression was reported less commonly and took the form of violence and theft of possessions and money. In one case, it was suggested that verbal and physical bullying evolved into relational bullying after the target stood up to the perpetrators:

“My child is frequently the target of homophobic and transphobic slurs. They are told ‘you should go kill yourself’; ‘What are you?’; ‘Have you got a penis?’; ‘You’re an “it”’. They have been physically assaulted (i.e., pushed around and into walls while others watched on). They stood up for themselves. Then the rumours started. All false. As it turns out, people don’t like having their homophobia/transphobia called out so they make other reasons to act out their hatred.” (P2)

Notably, while most bullying reported was peer-to-peer in nature, a few participants detailed events in which staff members either facilitated or engaged in perpetration which contributed to the hostility of the school environment. In one case, a student was, amongst additional peer-perpetrated bullying, “sent to the back of the tuck shop queue (by school rules) for non-standard uniform”, which was being worn to align with their gender identity (P16). In other instances, staff members were described as knowingly creating situations that aided the bullying by students:

“The PE teacher … called out to the students as he went to play a song on the speaker. He said, ‘Well girls, you are really going to like this song!’ He paused and then looked over at my Trans daughter and said, ‘…. and you too [name redacted].’ The students laughed. Some around her called out, ‘See, you’re not a girl! You’re a boy!’ Other students called out crude statements about her genitalia. The teacher did nothing about the bullying and instead continued with the exercise session.” (P5)

“Rather than support my child, on the request of the other children’s parents who were horrified that their children were in the company of my child, the school ‘psychologist’ decided to hold a ‘restorative meeting’ with my child without my knowledge or consent where the other children basically told my child how they felt. My child felt ambushed and so ashamed after this meeting and did not have the mental health capacity to voice his feelings - I got a text at work with the words ‘help me.’ ” (P10)

Theme 1: Whose Role is it Anyway?

Responses revealed significant variation in both the role principals had in addressing HBT bullying and participants’ conceptualisations of the capacity of principals to execute this role effectively. Several participants reported they approached a member of the principal team in the first instance.

Most participants expressed dismay at the inaction of school staff, including principals, after they had been made aware of the bullying. Inaction was attributed to various underlying mechanisms, including the passing of complaints between principals and other staff. Principals were commonly perceived by participants as being unwilling or unable to assume a meaningful role in the management of the problem, even when this was explicitly sought by the parent/caregiver:

“I spoke to the year level coordinator and asked that the matter be shared with the principal as it is a matter of discrimination. The principal felt that it was better left with the Year Level Coordinator as she had a better knowledge of the kids since this happened in the first 6 months of Year 7 … He seemed to not want to be part of it … His response was pathetic, he handballed it to others.” (P9)

“Access to the principal was rare. Communication was always fed down to the Wellbeing team. I would have liked to have spoken with the principal and heard from them about the outcome of staff bullying.” (P5)

However, the data did also suggest that principals do play a role in intervention. In contrast to the cases above, a participant recalled being “directed to the principal” (P6) after initially raising their concerns with their child’s teacher. In an alternative case of escalation, another participant approached the principal “following the inability of the teachers and other support staff to take appropriate and immediate action” (P13). The few participants who reported being satisfied with the response of school staff specifically expressed the view that principal involvement was not necessary because staff were “very empathetic and acted immediately” (P11), with the qualification that “if the situation was more severe, then I think the principal’s support would have been essential” (P14). Positive experience with principal involvement was characterised by the principal demonstrating understanding and a commitment to positive outcomes for the targeted student:

“[The deputy principal was] extremely professional and sensitive to my son’s needs … [and] has been available to my son at all times he has needed her. She has made him feel safe in the school environment.” (P15)

Many participants expressed a clear desire for the principal to intervene to some extent, and this role was accepted with varying degrees of enthusiasm. Where participants expressed no overt desire to have the principal involved in the intervention, principals’ attitudes were cited as key deterrents, over and above views about the role of principals more generally. On whether principal involvement may have made a difference to the outcome:

“Absolutely not. He is old- and from a different era, has no idea about current youth, and probably doesn’t understand transgender teens.” (P8)

“No. I think the principal is the problem.” (P7)

“No. I think our principal seems equally tepid on social justice issues. The few conversations we’ve had revealed a lack [of understanding] on LGBTQ+ issues.” (P2)

The participants who took this view, however, distinguished between the role of principals in prevention versus intervention. A consensus was that addressing HBT bullying requires an overhaul of school cultures. Some participants specifically acknowledged principals may be uniquely positioned to drive this:

“It was very engrained in the culture of the school so perhaps the culture shift was needed to be implemented from the top down.” (P12)

“I would like to see principals take the lead in these issues and educate their students on the history of queer people all over the world, the effects of bullying and especially the intersection of being in a minority and being bullied, and how to allow people to make choices for their own lives without judging them.” (P9)

Theme 2: Is it “Really” an Issue?

Irrespective of whether a principal or other staff member was primarily involved in addressing bullying, many participants perceived their concerns, and those of their children, were minimised and dismissed. This was deemed a significant reason for inaction and was particularly evident where the bullying was non-violent and/or staff perceived that the targeted student incited conflict themselves:

“I had a face-to-face meeting with the principal to discuss. They didn’t seem too concerned as it didn’t involve violence.” (P3)

“[The principal] saw it as an ‘isolated and rare issue’. Dismissive and victim blaming, as my son chose to grow his hair, and later to have his ears pierced. It was only taken somewhat seriously when there was a physical assault … though victim blaming still occurred.” (P4)

Participants conveyed a sense that the the severity and urgency of their circumstances were not understood, or were not reflected in the response of principals. Principal and staff were often perceived as lacking the understanding that precedes effective and responsive action. Participants highlighted that principals’ responses demonstrated a limited awareness of issues related to GS diversity, and minimal empathy for victims:

“He didn’t even show any empathy, and even the coordinator kept telling my son that he should just let it go … The principal at the new school … has also made similar remarks when kids at the new school have made similar comments. Principals we have had contact with need a lot more education on the effects of trans/bi/homophobic bullying on the victim.” (P9)

“… at one point our son reported directly to her during recess and following a homophobic attack she actually told our son that in her day, 'being gay was a good thing, it meant you were happy’ … They clearly have no idea what it means to be gay and how these and their comments are so hurtful and damaging when we asked for help.” (P13)

Similarly, participants noted the limitations of sympathetic responses that were not accompanied by definitive action to both stop the bullying and provide support for the targeted student (i.e. simply acknowledging an issue was insufficient). Positive experiences with intervention had two critical components: expressed understanding by the principal/staff that the bullying was problematic, and swiftly enacted intervention:

“He [the principal] was very involved. He felt really bad that my child had to go through that for so long. The bullies were made to apologise and suspended. It stopped.” (P6)

“[The staff members were] very empathetic and acted immediately – boy was suspended for one day.” (P11)

A participant who did not experience this dual-focused approach called for it explicitly:

“It was pretty poorly handled. No one really talking action - just saying it was not ok and wouldn’t be tolerated. More direct action, targeted intervention needed and more calling people on it.” (P12)

Theme 3: We Alone Bear the Consequences

Where school responses were characterised by inaction and school leadership was deemed ineffectual, participants expressed frustration at being forced into an advocacy role, whereby they became responsible for securing safe access to education for their child. This responsibility, and having to watch their children endure the consequences of the bullying, takes a significant toll on parent/caregivers:

“It is an isolating and exhausting role to take on when leadership of a school fails to ensure their staff are inclusive and professional, and additionally ensure that bullying complaints are met with zero tolerance.” (P5)

“My child makes statements like ‘the world is broken’. I try to bring light into their life every day to compensate for what they’re going though at school. I fall woefully short. I feel powerless. I feel enraged that we’re just expected to accept the status quo. Ultimately, I am heartbroken … When your child experiences something like this, the whole family system suffers.” (P2)

Common to many participants is the despondency they and their children felt because it was them, and not the perpetrators, who faced the adverse consequences and were least protected by the school. For the targeted student, this manifested as significant mental health issues, altering their behaviour to minimise risk, and pausing, ceasing, or modifying school attendance. The extent of the impact on targeted students’ mental health, a significant consequence of an unsafe school environment in isolation, also accounts for why special accommodations were often necessary:

“After this ‘meeting’ my child was so traumatised that they were no longer able to attend school and I had to stay with them in their room for fear that they would unalive themselves.” (P10)

“[The bullying consisted of] Verbal, emotional and physical abuse, gay slurs. Resulting in increased anxiety, school avoidance, depression, and suicidal ideation with plan.” (P4)

Parents were dismayed that their children felt as though they had to alter their own behaviour to minimise the risk of bullying, yet the perpetrators seemed to avoid having to do the same: “[The principals involved] were empathetic but didn’t directly deal with the students involved and it resulted in my child modifying their behaviour, not the perpetrators” (P1). Relatedly, targeted students’ trepidation about how other students may react to intervention was seemingly used by staff to refuse responsibility for determining the best course of action:

“The Wellbeing team spoke with my daughter and I face to face about the outcome of the bullying incident. They felt that the directive from the principal, by sending the PE teacher to undertake the inclusive workshop, was a good outcome. I agreed. My daughter was slightly optimistic about learning what had happened, yet she was such a bundle of anxiety about the backlash from other students.” (P5)

“I told them that my child was fearful of retaliation. Their response was ‘well, we will talk to your child but we will have to defer to what action they want us to take’. I expected more.” (P2)

Arguably, this imposition of adversity back onto the targeted student was another symptom of the tendency of principals and staff, inadvertently or otherwise, to hold them unduly accountable for the actions of others:

“I have been baffled and bewildered that the attitude to bullying seems to have not changed since I was at school 25 years ago. It seems to be that … the victim is just constantly told they need to be tougher and constantly gaslighted and blamed for their own bullying. I was dissatisfied with the entire process and the only thing I was pleased with was how strong and amazing my son was.” (P9)

“When I complained to the deputy principal, he asked me ‘what my child was doing to attract this kind of attention’? … It seemed that he was victim blaming.” (P13)

Academic performance and school attendance were often described as casualties of the bullying and associated mental health issues. Several participants explained that the response of school personnel, or lack thereof, undermined their child's trust in the adults at school, caused them to withdraw from participating in class and co-curriculars, and, in extreme cases, necessitated departure from their school:

“My daughter had lost all faith and trust in principals by that age. And felt anxious and fearful to go to school. From Year 10 she decided to school online, to avoid attending placed-based school. This has worked very well in building her confidence!” (P5)

“It made my son not want to attend school anymore, created a lot of anxiety and depression and led to them self-harming, I removed them from school within 6 months of the events starting. It took 12 months for his mental health to improve.” (P9)

“[There was] Not a lot of action. My child has ended up home schooling (partially as a result of the consistent transphobic bullying).” (P12)

Principles of fundamental human rights and access to education underpinned participants’ view that schools must improve their management of bias-driven bullying. Participants wanted schools and leadership, and not targeted students and their families, to be held accountable for addressing HBT bullying:

“Principals need to face the fact that there are more and more young people identifying as part of the LGBTIQA+ community; this community is much more vulnerable to anxiety, depression, self-harm, and suicide: and these kids are in their care. If they don’t educate themselves they will be at best complicit in the harming of a generation of kids who are simply fighting to exist, and be seen as valid.” (P9)

“I want leadership to fight for our kids’ basic human right to have access to an education free from bias or prejudice. I mean, if you’re not actively invested in the fundamentals of equality in education, how are you in the job in 2023?” (P2)

Theme 4: Beyond Bullying—The Whole-School Approach

There was an unequivocal desire for schools to take a proactive and preventative approach to HBT bullying, wherein schools would become safer for all students “who identify outside the mainstream” (P14). HBT bullying was conceptualised as stemming from an unfamiliarity with GS diversity, which may manifest as discomfort or fear. Increasing exposure to, and acceptance of, difference was therefore viewed as essential. Many participants contended that educating all students about GS diversity, coupled with empathy-raising curricula around the effects of bullying and its various forms, may deter bullying:

“[There should be] Education on queer history, biology of gender (more advanced than in current high school curriculum), intersectional feminism, privilege, the tolerance paradox and learning not to judge others. Exposure to queer stories, through plays, books, excursions and incursions, and through historical figures.” (P9)

Increased visibility of GS diversity was also considered a way in which GSD students themselves could be better supported by schools, including the suggestion of an “adult queer mentor” (P1) from whom GSD students could seek support. Participants implicitly made connections between the culture and GSD-friendly infrastructure of a school and the likelihood of a systemic HBT bullying issue. Other ideas echoed those that have recurrently been called for by GSD students and families, such as “visible signage around the school to encourage reporting of homophobic, biphobic and transphobic bullying, … celebrate days of significance - IDAHOBIT Day, Wear it Purple Day, Transgender Day of Visibility etc., school representatives marching in Pride march” (P5). An affirmative stance on GS diversity and displays of allyship must be accompanied by concrete policy (e.g. uniform) and supportive infrastructure:

“Staff should be trained on acceptance and managing LGBTIQ+ issues in the school grounds. Toilets should include all gender toilets so that gender diverse children have a safe place to go to the toilet. For their years at school my child does not drink or eat during the day so that they do not need to use the toilets which has led to issues with food.” (P10)

However, these supports are less likely to be sought, let alone enacted, where principals are perceived to be uninformed and/or refuse to affirm GSD students. This conflict compounded participants’ sense of helplessness. For better or worse, school leadership determines the stance of the school and thereby establishes expectations for others:

“I know of one school principal who rang the parents of young people who routinely harass LGBTQ + students before Wear it Purple Day and said, ‘this day is happening, if your child can’t be kind, maybe keep them home’. That’s leadership.” (P2)

“[My child faced] Homophobic exclusion from peers over a long term, enabled by school staff and teachers who ‘couldn’t do anything’ because of the school executive … Child is now acutely mentally ill with multiple hospital admissions … Staff ‘couldn’t do anything’ or say anything. Some staff wore rainbow lanyards for a few weeks to identify themselves as safe people however school executive asked that they stop.” (P7)

Subsequently, most participants, including those who had positive experiences, mentioned the importance of ongoing training and professional development pertaining to GS diversity, and supporting GSD students, reinforcing the perceived connection between knowledge and favourable attitudes and behaviours.

Discussion

This study provides insight into participants’ experiences navigating school responses to the HBT bullying of their children, with a focus on the involvement of school principals. It extends findings from previous qualitative studies of parent/caregivers’ experiences who reported bullying to school personnel (Brown et al., 2013; Harcourt et al., 2015). Parent/caregivers in this study had a desire for principal involvement in addressing HBT bullying, whether as a first point of contact, an option for escalation, and/or as a leader for improving the school climate for GS diversity; however, principals were reported to vary in their willingness and capacity to fulfill this role. The data reinforced the potential for interactions between schools and parent/caregivers (i.e. the mesosytem) to have significance for students’ schooling and wellbeing outcomes. Likewise, several factors within the school microsystem were identified as drivers of HBT bias and facilitators of HBT bullying.

Previous evidence suggests that school staff do not regard relational bullying as severe as physical bullying (e.g. Wolgast et al., 2022; Yoon & Kerber, 2003), and that their personal attitudes towards GSD minorities impact their ability to support GSD students (e.g. Bartholomaeus et al., 2017; Nappa et al., 2018). Thus, it is unsurprising that participants reported that non-violent bullying was taken less seriously and that principals’ own attitudes and limited knowledge impeded their ability to respond satisfactorily to these concerns. Likewise, if the targeted student was regarded as problematic or provocative, then staff may be less likely to intervene effectively (Berkowitz & Benbenishty, 2012). Highlighting the impossibility of their situation, participants suggested that their children’s desire to stand up to the perpetrators or present in a non-traditional manner meant that they themselves were pegged as troublesome, which in turn impeded the likelihood of receiving principal support.

Arguably, principals’ attitudes, knowledge, and actions are particularly consequential, given their role not only as potential first responders, but also as an option for escalation where either staff intervention has failed, the bullying increases in severity, and/or a staff member is the perpetrator. Where families perceive that school leadership cannot be relied upon to create a safe school environment, few remaining options for recourse are available. This can necessitate action that may have punitive effects for the targeted student, as was reported in this study, such as modifying their own behaviours to avoid attracting aggression, changing schools, or ceasing mainstream education (Ferfolja & Ullman, 2021). In a contemporary Australian context which has seen the Safe Schools controversy, the Religious Discrimination Act debate, and the same-sex marriage postal vote in the past 7 years alone, the politicisation of GS diversity, especially in the education sector, is pervasive (Cumming-Potvin & Martino, 2018; Thompson, 2019). Nonetheless, as was expressed by several participants, the conceptualisation of GS diversity as inherently contentious, and the tolerance of anti-GS diversity positions, is arguably incompatible with the work of educators, especially where it dictates which students are accommodated by the school system (Payne & Smith, 2011).

Implications for Schools and the Education System

Participants with negative experiences expressed frustration not only at the perceived inability of principals to accommodate for GS diversity, but equally at their management of the bullying, more generally, after it was brought to their attention. Conversely, some hallmarks of constructive responses can be extracted from the positive experiences.

A paradigm shift away from a preoccupation with whether an event constitutes bullying, and towards a focus on how leadership can make the targeted student feel safer at school, may be the first step to ensure that the student, and their parent/caregivers, do not feel discounted (Englehart, 2014). Our findings point to the intensely emotional and exhausting nature of the experience of school bullying for students and families alike. Noting the increasing pressures facing principals (Riley et al., 2021), the human dimensions of the role of the school leader remain critical (Boyland et al., 2016; Louis et al., 2016). The ability to extend empathy to, and comprehend the weight of their response for, students and their families is paramount (Englehart, 2014).

Other determinants of a productive response identified included ongoing communication with the targeted student and their family, a zero-tolerance policy, and decisive intervention that involves the perpetrators being made aware of the effects of their actions. Importantly, principals should avoid imposing the burden of advocacy and decision making on the targeted student and/or their parent/caregivers. Participants’ expected school principals to adopt a proactive and preventative approach that dismantles prejudice in students and staff alike. This is consistent with the well-established links between school climate and bullying and has previously been framed as anticipatory anti-bullying action (Paechter et al., 2021).

Climate-defining actions may include the acknowledgement of significant events such as Wear it Purple Day, displaying pride flags or symbols of allyship in classrooms, providing targeted professional development opportunities, and encouraging staff reflect the existence of GSD people in curriculum decisions (Hill et al., 2021). A principal who visibly endorses these initiatives may help establish the legitimacy of the cause, embolden staff to take aligned action, and fortify it against any backlash that may arise (Payne & Smith, 2017).

Unambiguous support of GS diversity may curtail the stratification of students’ social based on GSD identity, where heterosexuality and cisgenderism are typically upheld as the aspirational identities (Ullman, 2021b). Irrespective of the identity of the targeted student, HBT bullying assumes an educative or warning effect, for all, about the risks involved with diverging from the social norm, and the consequences for students’ wellbeing and safety at school can parallel that of direct victimisation (Asakura & Craig, 2014). Accordingly, there is an imperative for principals to consider that, in all likelihood, more people in the school community are impacted by the prejudice that exists within it than will be known to school personnel at the time. Likewise, the fact that most participants in this study reported that their child simultaneously identifies as both a gender and sexuality minority, and that several GSD parents also had GSD children, suggests the importance of an intersectional approach to affirming GS diversity in the school community. The importance of an intersectional approach is likewise emphasised by scholars who lament a “homonormative” approach to supporting GS diversity in schools, wherein performative inclusive practices are adopted without any meaningful effort to disrupt the norms and structures which make these practices necessary in the first place (Mittleman, 2023). Such an approach benefits only a portion of the students who are affected by HBT bullying.

Postgraduate educational management courses may need directed content to prepare principals for leading school communities that include GSD individuals (Boyland et al., 2016; O’Malley & Capper, 2015). Even brief professional development interventions with school staff may increase empathy for GSD youth (Greytak et al., 2013) and increase the likelihood of demonstrating supportive behaviours towards GSD students (Swanson & Gettinger, 2016). In addition to the aforementioned national frameworks, explicit training for principals needs to be grounded in the internationally recognised right to education without discrimination and access to safe and non-violent learning environments (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2019). Participants highlighted that it is not hyperbole to suggest that, in some cases, chronic non-intervention in bullying becomes an issue of access to education.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

Notwithstanding that generalisability and saturation are not aspirations of RTA, the authors acknowledge the limitations of such a small sample size and the brevity of some responses. Owing to the nature of the recruitment drive, participants were all supportive of GS diversity, with many involved in advocacy groups. Consequently, the experiences of parent/caregivers who were less supportive of, or knowledgeable about, GS diversity are not represented. This would be an important perspective for future research given that unsupportive parents could impede effective intervention (Maher & Sever, 2007). Moreover, the experiences reported have not been triangulated with the perspectives of their children, nor those of the principals and staff.

Beyond the study’s primary aim, the data emphasised important methodological considerations for researchers in the space. Firstly, noting our unequivocal support for an increased research effort to sample and collaborate with students themselves (O’Higgins Norman, 2020), parents of GSD students can also be rich sources of information about schooling experiences, especially when the focus is not on specific details of the bullying itself (Demaray et al., 2013). Secondly, qualitative questionnaires can be an effective means of eliciting meaningful data where participants are motivated to provide insightful responses in writing and are less likely to be available for interviews. As an exploratory, inductive investigation, it was beneficial to have a sample, albeit small, which included different experiences, identities, locations, and school types. Thirdly, researchers investigating school climate for GS diversity should take a “big picture” approach when considering the students who are impacted by a limiting or unsafe climate.

Conclusion

Principals of Australian high schools are involved in dealing with cases of HBT bullying; however, participants in this study conveyed that their concerns were not reliably met with empathy and remedial action. The dismissal of parent/caregivers’ concerns, the “handballing” of complaints between staff members, and the lack of empathy for the targeted student compound the already significant impact of an unsafe school climate for all students who experience these forms of prejudice and their families. However, when intervention is swift and support for the targeted student is both meaningful and ongoing, participants reinforced the significant capacity principals have to buffer the negative effects of the bullying. Likewise, principals were perceived to have a, if not the, critical role in leading climate initiatives that prevent systemic HBT bullying, especially as they pertain to affirmative school policies and professional development for staff.

Data Availability

Due to the nature of this research, the data shared in the manuscript is the extent of what can be made available in order to protect participant anonymity.

References

Asakura, K., & Craig, S. L. (2014). It gets better … but how? Exploring resilience development in the accounts of LGBTQ adults. Journal of Human Behaviour in the Social Environment, 24(3), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2013.808971

Australian Institute for Health and Welfare. (2023). LGBTQIA+ people. Retrieved March 5, 2024, from https://www.aihw.gov.au/family-domestic-and-sexual-violence/population-groups/lgbtiqa-people

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2017). Unpack the Principal Standard. Retrieved August 21, 2023, from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/lead-develop/understand-the-principal-standard/unpack-the-principal-standard

Bartholomaeus, C., Riggs, D. W., & Andrew, Y. (2017). The capacity of South Australian primary school teachers and pre-service teachers to work with trans and gender diverse students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 65, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.03.006

Berdahl, J. L. (2007). Harassment based on sex: Protecting social status in the context of gender hierarchy. The Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 641–658. Retrieved February 13, 2024, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/20159319

Berkowitz, R., & Benbenishty, R. (2012). Perceptions of teachers’ support, safety, and absence from school because of fear among victims, bullies, and bully-victims. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01132.x

Boyland, L., Swensson, J., Ellis, J., Coleman, L., & Boyland, M. (2016). Principals can and should make a positive difference for LGBTQ students. The Journal of Leadership Education, 15(4), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.12806/V15/I4/A1

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE.

Braun, V., Clarke, V., Boulton, E., Davey, L., & McEvoy, C. (2020). The online survey as a qualitative research tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(6), 641–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1805550

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

Brown, J. R., Aalsma, M. C., & Ott, M. A. (2013). The experiences of parents who report youth bullying victimization to school officials. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(3), 494–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260512455513

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

Clarke, V., & Smith, M. (2015). Not hiding, not shouting, just me: Gay men negotiate their visual identities. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(1), 4–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2014.957119

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66(3), 710–722. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131945

Cumming-Potvin, W., & Martino, W. (2018). The policyscape of transgender equality and gender diversity in the western Australian education system: A case study. Gender and Education, 30(6), 715–735. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2018.1483491

Davey, L., Clarke, V., & Jenkinson, E. (2019). Living with Alopecia Areata: An online qualitative survey study. British Journal of Dermatology, 180(6), 1377–1389. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17463

Demaray, M. K., Malecki, C. K., Secord, S. M., & Lyell, K. M. (2013). Agreement among students’, teachers’, and parents’ perceptions of victimization by bullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(12), 2091–2100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.10.018

Education Services Australia Ltd. (2020). Australian Student Wellbeing Framework. Retrieved August 21, 2023, from https://studentwellbeinghub.edu.au/educators/framework/

Englehart, J. M. (2014). Attending to the affective dimensions of bullying: Necessary approaches for the school leader. Planning and Changing, 45(1), 19–30. Retrieved February 17, 2023, from https://www.proquest.com/docview/1719261018/abstract/686BBA3A9584472DPQ/1?accountid=14649

Espelage, D. L. (2014). Ecological theory: Preventing youth bullying, aggression, and victimization. Theory into Practice, 53(4), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2014.947216

Farrelly, G., O’Higgins Norman, J., & O’Leary, M. (2017). Custodians of silences? School principal perspectives on the incidence and nature of homophobic bullying in primary schools in Ireland. Irish Educational Studies, 36(2), 151–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2016.1246258

Ferfolja, T., & Ullman, J. (2021). Inclusive pedagogies for transgender and gender diverse children: Parents’ perspectives on the limits of discourses of bullying and risk in schools. Pedagogy Culture & Society, 29(5), 793–810. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2021.1912158

Greytak, E. A., & Kosciw, J. G. (2014). Predictors of US teachers’ intervention in anti-lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender bullying and harassment. Teaching Education, 25(4), 410–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2014.920000

Greytak, E. A., Kosciw, J. G., & Boesen, M. J. (2013). Educating the educator: Creating supportive school personnel through professional development. Journal of School Violence, 12(1), 80–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2012.731586

Haigh, F., Kemp, L., Bazeley, P., & Haigh, N. (2019). Developing a critical realist informed framework to explain how the human rights and social determinants of health relationship works. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1571. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7760-7

Harcourt, S., Green, V. A., & Bowden, C. (2015). It is everyone’s problem: Parents’ experiences of bullying. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 44(3), 4–17. https://www.psychology.org.nz/journal-archive/Parents-Experiences-of-Bullying.pdf

Hill, A. O., Lyons, A., Jones, J., McGowan, I., Carman, M., Parsons, M., Power, J., & Bourne, A. (2021). Writing themselves in 4: The health and wellbeing of LGBTQA+ young people in Australia. https://doi.org/10.26181/6010fad9b244b

Kitzinger, C. (2005). Heteronormativity in action: Reproducing the heterosexual nuclear family in after-hours medical calls. Social Problems, 52(4), 477–498. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2005.52.4.477

Louis, K. S., Murphy, J., & Smylie, M. (2016). Caring leadership in schools: Findings from exploratory analyses. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(2), 310–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X15627678

Maher, M. J., & Sever, L. M. (2007). What educators in catholic schools might expect when addressing gay and lesbian issues: A study of needs and barriers. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education, 4(3), 79–111. https://doi.org/10.1300/J367v04n03_06

McCabe, P. C., Dragowski, E. A., & Rubinson, F. (2012). What is homophobic bias anyway? Defining and recognising microaggressions and harassment of LGBTQ youth. Journal of School Violence, 12(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2012.731664

Meyer, E. J. (2008). Gendered harassment in secondary schools: Understanding teachers’ (non) interventions. Gender and Education, 20(6), 555–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250802213115

Mittleman, J. (2023). Homophobic bullying as gender policing: Population-based evidence. Gender & Society, 37(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432221138091

Molina, A., Shlezinger, K., & Cahill, H. (2023). Asking for a friend: Seeking teacher help for the homophobic harassment of a peer. The Australian Educational Researcher, 50(2), 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00492-2

Moyano, N., & del Mar Sánchez-Fuentes, M. (2020). Homophobic bullying at schools: A systematic review of research, prevalence, school-related predictors and consequences. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 53, 101441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101441

Nappa, M. R., Palladino, B. E., Menesini, E., & Baiocco, R. (2018). Teachers’ reaction in homophobic bullying incidents: The role of self-efficacy and homophobic attitudes. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 15(2), 208–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0306-9

Newman, P. A., & Fantus, S. (2015). A social ecology of bias-based bullying of sexual and gender minority youth: Toward a conceptualisation of conversion bullying. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 27(1), 46–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2015.988315

O’Higgins Norman, J. (2020). Tackling bullying from the inside out: Shifting paradigms in bullying research and interventions. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 2(3), 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-020-00076-1

O’Malley, M. P., & Capper, C. A. (2015). A measure of the quality of educational leadership programs for social justice: Integrating LGBTIQ identities into principal preparation. Educational Administration Quarterly, 51(2), 290–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X14532468

Paechter, C., Toft, A., & Carlile, A. (2021). Non-binary young people and schools: Pedagogical insights from a small-scale interview study. Pedagogy Culture & Society, 29(5), 695–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2021.1912160

Patel, M. G., & Quan-Haase, A. (2022). The social-ecological model of cyberbullying: Digital media as a predominant ecology in the everyday lives of youth. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221136508

Payne, E. C., & Smith, M. (2011). The reduction of stigma in schools: A new professional development model for empowering educators to support LGBTQ students. Journal of LGBT Youth, 8(2), 174–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2011.563183

Payne, E. C., & Smith, M. J. (2017). Refusing relevance: School administrator resistance to offering professional development addressing LGBTQ issues in schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 54(2), 183–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X17723426

Price, D., & Green, D. (2016). Social-ecological perspective: Power of peer relations in determining cyber-bystander behavior. In M. F. Wright (Ed.), A social-ecological approach to cyberbullying (pp. 181–196). Nova Science Publishers Inc.

Reyes-Rodríguez, A. C., Valdés-Cuervo, A. A., Vera-Noriega, J. A., & Parra-Pérez, L. G. (2021). Principal’s practices and school’s collective efficacy to preventing bullying: The mediating role of school climate. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211052551

Riley, P., See, S. M., Marsh, H., & Dicke, T. (2021). The Australian principal occupational health, safety and wellbeing survey (IPPE report). Institute for Positive Psychology and Education, Australian Catholic University. Retrieved August 22, 2023, from https://www.principalhealth.org/reports/2020_AU_Final_Report.pdf

Smith-Millman, M., Harrison, S. E., Pierce, L., & Flaspohler, P. D. (2019). Ready, willing, and able: Predictors of school mental health providers’ competency in working with LGBTQ youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 16(4), 380–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2019.1580659

Stewart, M., Ryu, H., Blaque, E., Hassan, A., Anand, P., Gómez-Ramirez, O., MacKinnon, K. R., Worthington, C., Gilbert, M., & Grace, D. (2022). Cisnormativity as a structural barrier to STI testing for trans masculine, two-spirit, and non-binary people who are gay, bisexual, or have sex with men. PLOS ONE, 17(11), e0277315. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0277315

Swanson, K., & Gettinger, M. (2016). Teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and supportive behaviors toward LGBT students: Relationship to gay-straight alliances, antibullying policy, and teacher training. Journal of LGBT Youth, 13(4), 326–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2016.1185765

Swearer, S. M., Turner, R. K., Givens, J. E., & Pollack, W. S. (2008). You’re so gay! Do different forms of bullying matter for adolescent males? School Psychology Review, 37(2), 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2008.12087891

Thompson, J. D. (2019). Predatory schools and student non-lives: A discourse analysis of the Safe Schools Coalition Australia controversy. Sex Education, 19(1), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1475284

Trau, R. N. C., Härtel, C. E. J., & Härtel, G. F. (2012). Reaching and hearing the invisible: Organizational research on invisible stigmatized groups via web surveys. British Journal of Management, 24(4), 532–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2012.00826.x

Tully, L., Spyreli, E., Allen-Walker, V., Matvienko-Sikar, K., McHugh, S., Woodside, J., McKinley, M. C., Kearney, P. M., Dean, M., Hayes, C., Heary, C., & Kelly, C. (2021). Recruiting ‘hard to reach’ parents for health promotion research: Experiences from a qualitative study. BMC Research Notes. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-021-05653-1

Turner, A. J., & Coyle, A. (2000). What does it mean to be a donor offspring? The identity experiences of adults conceived by donor insemination and the implications for counselling and therapy. Human Reproduction, 15(9), 2041–2051. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/15.9.2041

Ullman, J. (2021a). Free to be… yet? The second national study of Australian high school students who identify as gender and sexuality diverse. https://doi.org/10.26183/3pxm-2t07

Ullman, J. (2021b). Trans/gender-diverse students’ perceptions of positive school climate and teacher concern as factors in school belonging: Results from an Australian national study. Teachers College Record, 124(8), 145–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/01614681221121710

Ullman, J., Hobby, L., Magson, N. R., & Zhong, H. F. (2023). Students’ perceptions of the rules and restrictions of gender at school: A psychometric evaluation of the Gender Climate Scale (GCS). Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1095255

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2019). Right to education handbook. https://doi.org/10.54675/ZMNJ2648

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. (2023). Defining school bullying and its implications on education, teachers and learners. Retrieved February 19, 2024, from https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/defining-school-bullying-and-its-implications-education-teachers-and-learners

Wolgast, A., Fischer, S. M., & Bilz, L. (2022). Teachers’ empathy for bullying victims, understanding of violence, and likelihood of intervention. Journal of School Violence, 21(4), 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2022.2114488

Yoon, J. S., & Kerber, K. (2003). Bullying: Elementary teachers’ attitudes and intervention strategies. Research in Education, 69(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.7227/RIE.69.3

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions The first author acknowledges receipt of a cost-of-living stipend to complete research as part of a PhD thesis, in the form of an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Laura G. Hanlon: the principal role in conceptualising the study, questionnaire design, data collection, data analysis, write-up of the manuscript, and implementing reviewer feedback. Stephanie N. Webb: involved with conceptualising the study and questionnaire design, developing the manuscript, and responding to reviewer feedback. Jill M. Chonody: involved with conceptualising the study and questionnaire design, developing the manuscript, and implementing reviewer feedback. Deborah A. Price: involved with conceptualising the study and questionnaire design, developing the manuscript, and composing responses to reviewer feedback. Philip S. Kavanagh: involved with conceptualising the study and questionnaire design, developing the manuscript, and responding to reviewer feedback by reducing manuscript size.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study were approved by the first author’s institution’s Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol #205245).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

As part of the informed consent process, participants were informed that their data may be used in a manuscript submitted for publication by a journal.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hanlon, L.G., Webb, S.N., Chonody, J.M. et al. Parental Perspectives on Principals’ Responses to Homophobic, Biphobic, and Transphobic Bullying in Australian High Schools: An Exploratory Study. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-024-00252-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-024-00252-7