Abstract

This study provides a systematic review of literature from India on traditional bullying and victimization among school-going adolescents. A search of bibliographic electronic databases PsycINFO, MEDLINE, ERIC, Web of Science, and PubMed was performed in May 2020. Thirty-seven studies were included in the review. For each study included, the following specifics were examined: (a) methodological characteristics, (b) prevalence estimates of bullying behavior, (c) forms of bullying, (d) risk factors, and (e) consequences of bullying. It was found that bullying happens in India, and some risk factors for bullying and victimization in India are typical to the Indian context. In addition, bullying in India is associated with adverse consequences for both the aggressor and the victim. Many studies on bullying from India should be interpreted cautiously because of problems with data collection processes, instrumentation, and presentation of the findings. Cross-cultural comparisons for prevalence estimates, and longitudinal studies to examine the direction of possible influence between bullying and its correlates need to be conducted, to cater to the large adolescent population of India.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Bullying is an intentional and repetitive act of physical or psychological aggression, where the aggressor is more powerful than the victim (Olweus 1993). Meta-analytic studies have confirmed the marked prevalence of and risk factors associated with bullying perpetration and victimization among children and adolescents in school (Modecki et al. 2014). In a recent survey conducted in 79 countries with over 300,000 participants, 30% of the adolescent respondents reported that they had been victims of bullying in the past 30 days (Elgar et al. 2015). In India, research on bullying is scarce, certainly in proportion to its population size, as well as socio-cultural diversity (Milfont and Fischer 2010; Smith et al. 2018). The vast adolescent population provides ample opportunity and resources to further our understanding in the field of bullying. The disparities seen in India in terms of socio-cultural factors such as SES, religion, caste, gender, and color, which have been recognized as typical to the Indian context (Panda and Gupta 2004), may aid in breeding an imbalance of power, an underlying element of bullying (Olweus 1993). Moreover, given the diverse socio-cultural context of India, and its structural incongruence with western cultures (Charak and Koot 2015), literature from western countries may not be generalizable to the Indian population, thus requiring scientific attention to examine the role of these factors specifically in India (Smith et al. 2018).

Through the current review, we aim to provide researchers a notion of challenges that need to be addressed in future studies on bullying and victimization in India. Systematic reviews are of importance, because they closely follow a scientific and step-by-step approach, with an aim of limiting systematic errors or bias, and particularly seek to identify, evaluate, and synthesize all relevant studies to elucidate knowledge and advanced understanding of the topic at hand (Petticrew and Roberts 2008). The present systematic review focuses on traditional bullying and victimization among adolescents in schools in India, highlighting the following specifics: (a) methodological characteristics of included studies, (b) prevalence estimates of bullying behavior, (c) forms of bullying, (d) risk factors, and (e) consequences of bullying. Specifically, we examine the psychometric properties of the instruments adopted in the included studies from India, as well as methodological characteristics including design and data collection, sample size and sampling procedures of the included studies, and characteristics of bullying behavior distinctive to the Indian context.

Method

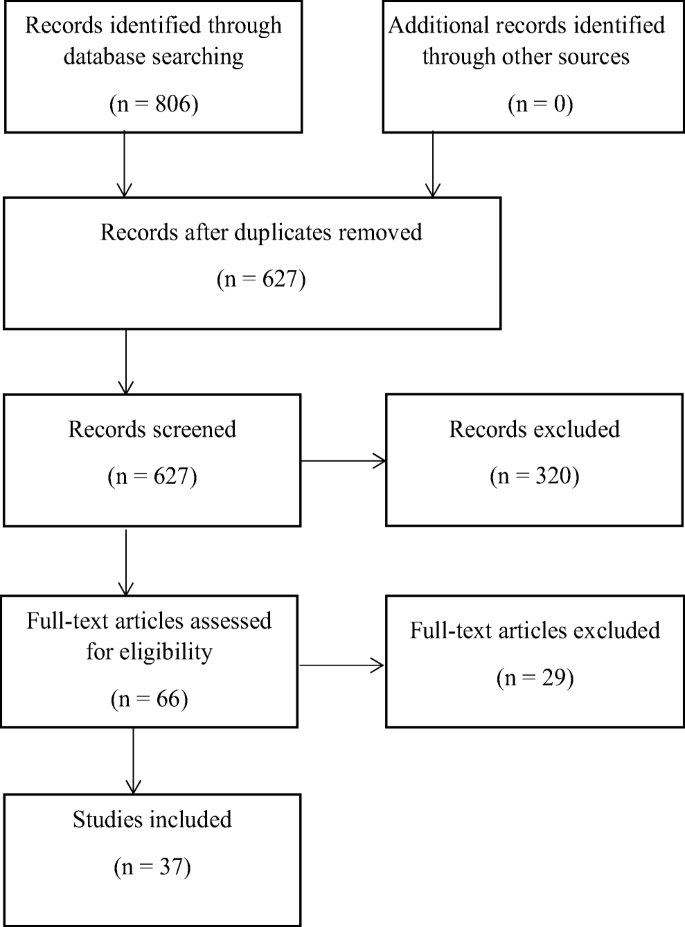

Guidelines provided by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) for conducting systematic reviews were followed in the present study. A systematic search of bibliographic electronic databases PsycINFO, MEDLINE, ERIC, Web of Science, and PubMed was performed in May 2020. The following terms formed the basis of the search strategy: “bullying” OR “peer victim*” OR “bullied” OR “bully” OR “school harassment*” OR “ragging” OR “school violence*” AND “India” OR “Indian” OR “Hindi”. No date limit was set for the search. Our search was not limited to published articles; book chapters, dissertations, unpublished articles, and posters were also eligible. A flow diagram of the search results is provided in Fig. 1. Only studies that focused on bullying by peers and the resulting victimization at school were included. Articles on online bullying or cyberbullying were excluded. There were too few studies on cyberbullying in India to provide a meaningful analysis, especially when such an analysis should also deal with recent concerns about cyberbullying studies (e.g., Wolke et al. 2017). Non-empirical studies that did not include quantifiable data (for instance, book reviews) were excluded as we focus on only empirical research in the current review. Six studies used interviews to gather data; for instance, Kshirsagar et al. (2007) used Olweus’s (1996) pre-tested semi-structure interview to collect data on bullying and victimization in their study. The answers to these interviews were quantified and used in statistical analyses, and therefore, we included the articles in the current review. Studies on Indian children who live outside of India were excluded. Because we focused on adolescents in school, the age of students in included studies should range between 10 and 19 years. For studies on students whose ages only partly overlapped with this intended range, we applied the rule that the average age should fall within the intended range and the lowest and highest age should be within 2 years of the intended age limits. Two studies did not provide a definitive age range of the participants included in their study (Patel et al. 2017; Schäfer et al. 2018); however, the studies indicate that the participants were from grade 8 to 10 (who are typically 12 to 15 years old), thereby qualifying for inclusion in the present review. Three studies did not provide the mean age of the participants in their study though they specify the age range of the participants (Kshirsagar et al. 2007; Malik and Mehta 2016; Ramya and Kulkarni 2011), and because the lower limit or higher limit of the provided age range in these three study fell within 2 years of 11–19 years old, we have included them in the present review. Eventually, 37 studies were included in the final review.

Results

Methodological Characteristics of Included Studies

Design and Data Collection

Of the 37 studies that were included, two were longitudinal studies (Nguyen et al. 2017; Thakkar et al. 2020), two were experimental studies with pre- and post-test intervention designs (Sharma et al. 2020; Shinde et al. 2018, 2020), whereas the others were cross-sectional studies. Seven of the 37 studies used peer-reports, 21 studies used self-reports, two studies used both self- and peer-reports (Chakrabartty and Gupta 2016; Thakkar et al. 2020), whereas six studies used structured or semi-structured interviews and open-ended questions to collect data on bullying and victimization (Kshirsagar et al. 2007; Malhi et al. 2014, 2015; Malik and Mehta 2016; Munni and Malhi 2006; Ramya and Kulkarni 2011). One study used a photo-story method (Skrzypiec et al. 2015), where participants were invited to use a photograph or picture to illustrate their opinions or experiences of bullying.

Psychometric Properties

Psychometric properties of the scales or interviewing approaches used in the studies have been reported in 22 of the 37 studies. Four studies reported the reliability and validity of the original scale (Malik and Mehta 2016; Menon and Hannah-Fisher 2019; Patel et al. 2017; Samanta et al. 2012), but did not report psychometric properties based on the Indian sample, while five studies reported neither the psychometric properties of the original scale nor its generalizability to the Indian sample (Kshirsagar et al. 2007; Maji et al. 2016; Sarkhel et al. 2006; Sharma et al. 2017; Sethi et al. 2019). Two studies used a scale developed by the authors of the study; however, psychometric properties were not reported (Kelly et al. 2016; Prakash et al. 2017). Four studies did not provide a clear description of the method of data collection, and the validity of the approach was not defined (Malhi et al. 2014, 2015; Munni and Malhi 2006; Ramya and Kulkarni 2011). Seven studies specified that the instrument used to assess bullying behavior was an English language questionnaire, while 10 studies used either existing translations or translations created by the authors of the study, of English scales into Indian regional languages. Two studies used English instruments and orally explained the translation in Punjabi (Lee et al. 2018) or translated the difficult words to Hindi (Malik and Mehta 2016), and one study used English and Hindi language translations of the scales (Thakkar et al. 2020).

Sampling

Of the 37 studies, 25 studies used a convenience or purposive sampling approach to recruit participants. One study used a proportionate random sampling approach to recruit participants (Kelly et al. 2016); one study used a two-stage cluster sampling approach (Swain et al. 2014); one used a multi-stage sampling design (Chakrabartty and Gupta 2016); six studies reported using a random sampling method for selecting either schools or participants (Kshirsagar et al. 2007; Maji et al. 2016; Malik and Mehta 2016; Nguyen et al. 2017; Ramya and Kulkarni 2011; Sarkhel et al. 2006), but only one of them reported how the school sample was randomized (by draw of lots; Sethi et al. 2019). Two studies used a randomized control design to allocate participants to experimental or control groups, where Prakash et al. (2017) used a cluster randomized control design, and the intervention study by Shinde et al. (2018) used randomized and masked groups for each of three study groups. One study used a quasi-experimental design, where of the two participating schools, one was randomly assigned to the intervention group, and the other was assigned to the control group (Sharma et al. 2020). Of the 37 studies included in the review, 17 studies had a sample size of less than 300 participants, nine studies had a sample size of between 300 and 500 participants, whereas 11 studies had a sample size larger than 500 participants.

The articles widely differed in their statistical reporting practices, and therefore, the amount of statistical information provided in the below sections and Table 1 varies per reported study. Time frames of bullying and victimization prevalence estimates are reported in the below sections if they were specified in the included studies. Percentages are rounded off without decimals.

Prevalence Studies

Eight studies focused on the prevalence of bullying in India, while 14 others provided descriptive statistics or percentages for sample participants that qualified as bullies or victims in their study. Of these, five studies provided the participants with a definition of bullying for peer nomination estimates of bullying and victimization in their research (Goossens et al. 2018; Khatri 1996; Lee et al. 2018; Skrzypiec et al. 2018a; Thakkar et al. 2020). Studies from the same city or region in India were scarce, and reports inconsistent. We found that bullying perpetration estimates ranged from 7% (Thakkar et al. 2020) to 31% (Kshirsagar et al. 2007), and bullying victimization ranged from 9% (Thakkar et al. 2020) to 80% (Maji et al. 2016), across studies. For instance, Maji et al. (2016) found that only 38 of 273 adolescents were not bullied, resulting in a dominant 80% students qualifying as victims of bullying. Next to region differences in prevalence, estimates may be related to the reporter used. Kshirsagar et al. (2007) found higher prevalence rates for bullying for self-reports than for parent or guardian interviews, whereas Thakkar et al. (2020) found higher prevalence estimates for bullying and victimization for peer reports than for self-reports. Findings as regards prevalence and other findings or aspects reviewed of each study are reported in Table 1.

Forms of Bullying

It was observed that name-calling or using bad words were common forms of bullying observed among adolescents next to physical bullying. For instance, Kshirsagar et al. (2007) reported that the most common types of bullying were teasing and giving discriminatory or offensive labels and nick names to others. Similarly, Malhi et al. (2014) reported that 16% of their sample were victims of direct bullying or physical bullying and 34% were victims of name-calling. Skrzypiec et al. (2015) showed that caste-based bullying was reported by students and that for females, sexual harassment or “eve-teasing” was a common occurrence.

Risk Factors for Bullying and Victimization

Thirteen studies from India focus on the risk factors and correlates of bullying and victimization. Risk factors refer to variables that have the potential to increase or decrease the likelihood of bullying behaviors occurring (Olweus 1996), whereas correlates of bullying behaviors focus on factors that are significantly associated with, and co-occur with, bullying behaviors. Risk factors for bullying and victimization identified through the review were body weight (Patel et al. 2017), religion (Thakkar et al. 2020), and age (Malhi et al. 2015; Ramya and Kulkarni 2011), and factors that were found to be significantly correlated to bullying behaviors were personality traits (neuroticism; Donat et al. 2012), academic performance (Patel et al. 2017), urban/rural setting (Nguyen et al. 2017; Samanta et al. 2012), and father’s education level (Sethi et al. 2019). Factors that were found to be risks or correlates of bullying behavior in various studies included in the review were caste-system of India (Kelly et al. 2016; Sethi et al. 2019; Thakkar et al. 2020), socio-economic status (Malhi et al. 2015; Sethi et al. 2019), and gender differences.

Studies focusing on the caste system of India reported contradictory findings ranging from “General” caste students experiencing lower harassment (Kelly et al. 2016), “General” caste students experiencing more victimization (Thakkar et al. 2020), to no differences between castes (Khatri 1996). As regards the role of religion, Thakkar et al. (2020) reported that non-Hindu children were significantly more likely to classify as victims than Hindu children. For SES, Malhi et al. (2015) found a significant relationship between SES and victimization, with low SES students scoring higher on physical victimization, whereas high SES students scored higher on relational victimization. For gender comparison, although not fully consistent, most studies within India reported that boys scored higher than girls on bullying perpetration and bullying victimization (Narayanan and Betts 2014; Nguyen et al. 2017; Patel et al. 2017; Pronk et al. 2017; Ramya and Kulkarni 2011; Sethi et al. 2019; Sharma et al. 2017; Swain et al. 2014). Age was also found to have some, though inconsistent, relationship with bullying behavior in school (Malhi et al. 2015; Patel et al. 2017; Ramya and Kulkarni 2011).

Consequences of Bullying

Being bullied was found to be associated with anxiety, depression, and preferring to stay alone (Kshirsagar et al. 2007). Also, bullied children were more likely to report symptoms such as school phobia, vomiting, catastrophizing, self-blaming, and sleep disturbances (Kshirsagar et al. 2007; Maji et al. 2016). Bully-victims had higher risk of conduct problems, hyperactivity, and academic difficulties, and while bullies were found to be better at academics, they had high self-esteem, and higher risk of hyperactivity and conduct problems (Malhi et al. 2014; Sarkhel et al. 2006).

Discussion

Based on the syntheses of studies included in our review, we draw the following conclusions: (a) limitations in methodological characteristics of studies were identified with regard to sampling, instrumentation, data collection processes, and presentation of findings, and thus, conclusions from the included studies must be considered cautiously; (b) bullying happens in India, as it does internationally, though the range of prevalence estimates varies widely across studies; (c) name-calling, using bad words and other forms of relational and social bullying are common in India, and physical bullying is also prevalent; (d) risk factors for bullying and victimization in India show some factors that are typical to the Indian context, for example, caste; and (e) bullying is associated with adverse consequences for both, the aggressor and the victim, in India.

The current review notes that bullying is widely spread in India. However, available prevalence estimates vary largely across India, for bullying perpetration and for victimization. India is a geographically vast country, with enormous differences in regional socio-demographics (Charak and Koot 2015), thereby constraining prevalence estimates to stratified regions. Scholars have noted that homogeneity within culture in India, like in many other countries, cannot be assumed (Panda and Gupta 2004). Thus, generalizing regional prevalence estimates to be representative across India is questionable, calling attention to the need to conduct cross-regional and cross-cultural comparative studies of bullying behavior within the country.

Furthermore, the type of instruments and their psychometric properties impact the findings of a study (Milfont and Fischer 2010), thereby not only making prevalence estimates from studies in the present review questionable but also warranting caution to conclusions. Also, conclusions about similarities or differences between the Indian and Western contexts require that metric invariance first be established to allow cross-ethnic and cross-cultural comparisons (Milfont and Fischer 2010). Of the 37 studies included in the present review, 22 studies provided descriptions of the psychometric properties of the instruments used, while 15 studies did not report the properties of instruments in their study raising concerns about comparability across studies in terms of instruments used. Furthermore, most studies on bullying in India adopted a quantitative method of data collection, where only 6 out of the included 37 in the present review used a qualitative approach to collect data for their research. The concerns about validity are increased by the over reliance on self-reports; we found that only 7 of the 37 studies used peer-reports, and 2 studies used self- as well as informant reports. In self-rating procedures, pupils tend to underestimate their aggressive behavior and emphasize prosocial behavior on account of social desirability (Salmivalli et al. 1996). There is an urgent need to validate and standardize instruments, with special attention to peer reports that assess bullying behaviors and establish their generalizability to Indian samples, to attain unbiased reports of bullying behavior in India (Sousa and Rojjanasrirat 2011).

Furthermore, only few studies included a sample that is sizable enough to provide firm, stable conclusions (Naing et al. 2006), and thus, the basis for the generalizability of the reports on the prevalence is very narrow. Ioannidis (2005) asserted that the smaller the sample sizes in a study, the smaller the power of the study, and consequently the higher the likelihood of the research findings to be affected by bias. Thus, we emphasize the need to conduct more studies across India, with proportional sample sizes for objective, less biased conclusions regarding bullying behavior. Also, the purposive selection of participants in 25 of the 37 included studies poses a potential threat to the validity of findings. In future studies, random sampling approaches should be used to study bullying in India.

Furthermore, we observe that there are only two longitudinal studies from India (Nguyen et al. 2019; Thakkar et al. 2020). Longitudinal studies help disentangle antecedents and consequents, to estimate the inter-individual variability in intra-individual (or within-person) patterns of change (Curran et al. 2010), allowing investigations of the sequence of occurrence of bullying with its risks and outcomes. Additionally, several studies in the present review report the adverse effects of bullying; however, the magnitude of these effects remains unclear. Only two of the 37 included studies were experimental studies with pre- and post-test intervention designs (Sharma et al. 2020; Shinde et al. 2018, 2020), which also underlines the urgent need to conduct fundamental indigenous research on the topic of bullying behaviors so that future research focusing on effective and tailor-cut interventions can be modeled for the Indian context. Also, given that most studies included were cross-sectional, cause and effect reasoning for bullying behavior remains elusive in India, and warrants further attention.

Lastly, we emphasize that risk factors of bullying need to be studied in light of the Indian culture to understand its meaning and relevance in the culture (Smith et al. 2018). In western literature as well, several recent studies have indicated a growing need to study bullying in relation to its broader socio-cultural context (Graham 2016). This is imperative in the Indian context given the contextual-development perspective (Chen and French 2008), which suggests that in collectivistic countries like India, context is more likely to affect evaluations of socially acceptable behavior and experiences, rather than individual attributes. Given the diversity and population density of India, considerable disparities and inequalities co-exist between cultures and also within the sub-groups of particular cultures (Panda and Gupta 2004). For instance, factors such as caste, dissimilarities between urban and rural youth, and the range of SES as observed in India can help in better, more deeply understanding bullying.

Conclusions and Implications for Future Research

This review contributes valuable findings in the field of bullying and victimization in India. However, it has been noted that conducting research in India comes with its own set of logistical and contextual challenges (Smith et al. 2018), and thus, the conclusions drawn through the review must be considered with due caution given methodological limitations of the included studies. The quality of research conducted in India has scope of improvement in terms of methodological rigor, data collection processes, instrumentation, and presentation of the findings.

The present study is limited in capacity as it does not include a report on cyberbullying, and thus, future research on the topic of cyberbullying is necessitated within the Indian context. Furthermore, terms such as “aggression” and “discrimination” were not used as search terms in the current study. However, bullying is a form of aggression, and discrimination could be, in some cases, strongly tied to bullying (Verkuyten and Thijs 2002). Future studies should pay more attention to the relations between bullying and discrimination.

In contrast to the large body of research on bullying from western countries where findings have been reproduced with a delimited adolescent population insistently, data from India is scanty. India accommodates the largest adolescent population in the world, providing a potential reservoir of relatively untapped resources that could provide in-depth knowledge of causes and consequences of bullying and victimization. Given its special cultural context, there is considerable scope to scrutinize cultural contexts of bullying behavior in India that could assist in revealing novel insights, such as the role of socio-economic distance between different sects of society in low to middle income countries. Such insights might facilitate the conception of dynamic intervention designs for not only the Indian population but also for western populations. Future studies that compare how bullying happens in the western and Indian context would also help shed further light on this topic.

Notes

-

1.

Study 3 (Correia et al. 2009) and 4 (Donat et al. 2012) have the same Indian sample in their studies. However, the variables examining correlates and consequences of bullying are different in the studies, and thus for the purpose of our review, we include both studies.

-

2.

Study 8 by Khatri and Kupersmidt (2003) is based on a dissertation thesis submitted to University of North Carolina by the first author in 1996. For the purpose of our review, we consider the dissertation and the journal article as one inclusion since the participants as well as bullying reports are the same for both.

-

3.

Study 19 (Nguyen et al. 2017) and 20 (Nguyen et al. 2019) have the same Indian sample in their studies. However, the former paper focuses on prevalence and forms of bullying and victimization, whereas the latter one examines psychosocial outcomes of victimization, and thus, we include both studies separately in the present review.

-

4.

Study 32 includes reports from two articles (Shinde et al. 2018; Shinde et al. 2020). The studies use an intervention design with the same sample, and include reports after 12-month follow-up and 17-month follow-up of the design, both of which have been reported in point 32 in the present review.

-

5.

Study 35 (Suresh and Tipandjan 2012) uses a retrospective bullying questionnaire with undergraduate college students. As the study focuses on bullying behavior in school retrospectively with adolescents, we included the study in the present review.

References

Articles marked with an asterisk (*) in the refernce list are the studies that have been included for synthesis in the present review.

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Bond, L., Wolfe, S., Tollit, M., Butler, H., & Patton, G. (2007). A comparison of the Gatehouse Bullying Scale and the Peer Relations Questionnaire for students in secondary school. Journal of School Health, 77, 75–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00170.x.

*Bowker, J. C., Markovic, A., Cogswell, A., & Raja, R. (2012). Moderating effects of aggression on the associations between social withdrawal subtypes and peer difficulties during early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 995–1007.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2013). CDC-YRBS-Questionnaires and item rationales – adolescent and school health. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/questionnaire_rationale.htm. Accessed 15 Sept 2013.

*Chakrabartty, S. N., & Gupta, R. (2016). Test validity and number of response categories: a case of bullying scale. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 42, 344–353.

Charak, R., & Koot, H. M. (2015). Severity of maltreatment and personality pathology in adolescents of Jammu, India: a latent class approach. Child Abuse & Neglect, 50, 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.05.010.

Chen, X., & French, D. C. (2008). Children’s social competence in cultural context. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 591–616. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093606.

*Correia, I., Kamble, S. V., & Dalbert, C. (2009). Belief in a just world and well-being of bullies, victims and defenders: a study with Portuguese and Indian students. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 22, 497–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800902729242.

Curran, P. J., Obeidat, K., & Losardo, D. (2010). Twelve frequently asked questions about growth curve modeling. Journal of Cognition and Development, 11, 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248371003699969.

*Donat, M., Umlauft, S., Dalbert, C., & Kamble, S. V. (2012). Belief in a just world, teacher justice, and bullying behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 38, 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21421.

Elgar, F. J., McKinnon, B., Walsh, S. D., Freeman, J., Donnelly, P. D., de Matos, M. G., et al. (2015). Structural determinants of youth bullying and fighting in 79 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57, 643–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.08.007.

Espelage, D. L., & Holt, M. K. (2001). Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: Peer influences and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 2, 123–142. https://doi.org/10.1300/J135v02n02_08.

*Goossens, F., Pronk, J., Lee, N., Olthof, T., Schäfer, M., Stoiber, M. . . . Kaur, S. (2018). Bullying, defending and victimization in Western Europe and India: similarities and differences. In P. K. Smith, S. Sundaram, B. A. Spears, C. Blaya, M. Schäfer, & D. Sandhu (Eds.), Bullying, cyberbullying and student well-being in schools: Comparing European, Australian and Indian Perspectives. (pp. 146–165). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

*Gothwal, V. K., Sumalini, R., Irfan, S. M., Giridhar, A., & Bharani, S. (2013). Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire: evaluation in visually impaired. Optometry and Vision Science: Official Publication of the American Academy of Optometry, 90, 828–835. https://doi.org/10.1097/OPX.0b013e3182959b52.

Graham, S. (2016). Victims of bullying in schools. Theory Into Practice, 55, 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1148988.

Hamburger, M.E., Basile, C., Vivolo, A.M., 2011. Measuring bullying victimization, perpetration and bystander experiences; A compedium of assessment tools. Centres for Disease Control and National Centre for Injury Prevention and Control, Atlanta, GA.

Ioannidis, J. P. (2005). Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Medicine, 2, e124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124.

Kazdin, A. E. (1996). Conduct disorders in childhood and adolescence. California: Sage Publications.

*Kelly, O., Krishna, A., & Bhabha, J. (2016). Private schooling and gender justice: an empirical snapshot from Rajasthan, India’s largest state. International Journal of Educational Development, 46, 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.10.004.

*Khatri, P. (1996). Aggression, peer victimization, and social relationships among rural Indian youth (Doctoral dissertation). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

*Khatri, P., & Kupersmidt, J. B. (2003). Aggression, peer victimization, and social relationships among Indian youth. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27, 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250244000056.

*Kshirsagar, V. Y., Agarwal, R., & Bavdekar, S. B. (2007). Bullying in schools: prevalence and short-term impact. Indian Pediatrics, 44, 25–28.

*Lee, N., Pronk, J., Olthof, T., Sandhu, D., Kaur, S., & Goossens, F. (2018). Defining the relationship between risk-taking and bullying during adolescence: a cross-cultural comparison. In P. K. Smith, S. Sundaram, B. A. Spears, C. Blaya, M. Schäfer, & D. Sandhu (Eds.), Bullying, cyberbullying and student well-being in schools: Comparing European, Australian and Indian perspectives. (pp. 166–185). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

*Maji, S., Bhattacharya, S., & Ghosh, D. (2016). Cognitive coping and psychological problems among bullied and non-bullied adolescents. Journal of Psychosocial Research, 11, 387–396.

*Malhi, P., Bharti, B., & Sidhu, M. (2014). Aggression in schools: psychosocial outcomes of bullying among Indian adolescents. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 81, 1171–1176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-014-1378-7.

*Malhi, P., Bharti, B., & Sidhu, M. (2015). Peer victimization among adolescents: relational and physical aggression in Indian schools. Psychological Studies, 60, 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-014-0283-5.

*Malik, A., & Mehta, M. (2016). Bullying among adolescents in an Indian school. Psychological Studies, 61, 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-016-0368-4.

*Menon, M., & Hannah-Fisher, K. (2019). Felt gender typicality and psychosocial adjustment in Indian early adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 43, 334–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025418820669.

Milfont, T. L., & Fischer, R. (2010). Testing measurement invariance across groups: applications in cross-cultural research. International Journal of Psychological Research, 3, 111–130. https://doi.org/10.21500/20112084.857.

Modecki, K. L., Minchin, J., Harbaugh, A. G., Guerra, N. G., & Runions, K. C. (2014). Bullying prevalence across contexts: a meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55, 602–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.007.

*Munni, R., & Malhi, P. (2006). Adolescent violence exposure, gender issues and impact. Indian Pediatrics, 43, 607–612.

Mynard, H., & Joseph, S. (2000). Development of the multidimensional peer‐victimization scale. Aggressive Behavior, 26, 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(2000)26:2<169::AID-AB3>3.0.CO;2-A.

Naing, L., Winn, T., & Rusli, B. N. (2006). Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. Archives of Orofacial Sciences, 1, 9–14.

*Nambiar, P., Jangam, K., Roopesh, B. N., & Bhaskar, A. (2019). Peer victimization and its relationship to self-esteem in children with mild intellectual disability and borderline intellectual functioning in regular and special schools: an exploratory study in urban Bengaluru. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629519831573.

*Narayanan, A., & Betts, L. R. (2014). Bullying behaviors and victimization experiences among adolescent students: the role of resilience. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 175, 134–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2013.834290.

*Nguyen, A. J., Bradshaw, C., Townsend, L., & Bass, J. (2017). Prevalence and correlates of bullying victimization in four low-resource countries. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517709799.

*Nguyen, A. J., Bradshaw, C. P., Townsend, L., Gross, A., & Bass, J. (2019). It gets better: attenuated associations between latent classes of peer victimization and longitudinal psychosocial outcomes in four low-resource countries. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 372–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0935-1.

Olweus, D. (1978). Aggression in the Schools: Bullies and Whipping Boys. Washington, DC: Hemisphere Press (Wiley).

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: what we know and what can we do. Malden, MA: Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10114.

Olweus, D. (1996). Bully/victim problems in school. Prospects, 26, 331–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02195509.

Orpinas, P., & Horne, A. (2006). Bullying prevention: Creating a positive school climate and developing social competence. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Panda, A., & Gupta, R. K. (2004). Mapping cultural diversity within India: a meta-analysis of some recent studies. Global Business Review, 5, 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/097215090400500103.

Parada, R. H. (2000). Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument: A theoretical and empirical basis for the measurement of participant roles in bullying and victimization of adolescence: An interim test manual and a research monograph: A test manual. Sydney, Australia: Publication Unit, Self-concept Enhancement and Learning Facilitation (SELF) Research Centre, University of Western Sydney.

*Patel, H. A., Varma, J., Shah, S., Phatak, A., & Nimbalkar, S. M. (2017). Profile of bullies and victims among urban school-going adolescents in Gujarat. Indian Pediatrics, 54, 841–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-017-1146-7.

Perry, D. G., Kusel, S. J., & Perry, L. C. (1988). Victims of peer aggression. Developmental Psychology, 24, 807–814. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.24.6.807.

Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2008). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. John Wiley & Sons.

*Prakash, R., Beattie, T., Javalkar, P., Bhattacharjee, P., Ramanaik, S., Thalinja, R. . . . Isac, S. (2017). Correlates of school dropout and absenteeism among adolescent girls from marginalized community in north Karnataka, south India. Journal of Adolescence, 61, 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.09.007.

*Pronk, J., Lee, N. C., Sandhu, D., Kaur, K., Kaur, S., Olthof, T., & Goossens, F. A. (2017). Associations between Dutch and Indian adolescents’ bullying role behavior and peer-group status: cross-culturally testing an evolutionary hypothesis. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41, 735–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416679743.

*Ramya, S. G., & Kulkarni, M. L. (2011). Bullying among school children: prevalence and association with common symptoms in childhood. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 78, 307–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-010-0219-6.

Rigby, K., & Slee, P. T. (1991). Bullying among Australian school children: Reported behavior and attitudes toward victims. The Journal of Social Psychology, 131, 615–627.https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1991.9924646.

Rigby, K., & Slee, P. T. (1993). Dimensions of interpersonal relation among Australian children and implications for psychological well-being. The Journal of Social Psychology, 133, 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1993.9712116.

Ruchkin, V., Schwab-Stone, M., & Vermeiren, R. (2004). Social and Health Assessment (SAHA): Psychometric development summary. New Haven, CT: Yale University.

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:1<1::AID-AB1>3.0.CO;2-T.

*Samanta, A., Mukherjee, S., Ghosh, S., & Dasgupta, A. (2012). Mental health, protective factors and violence among male adolescents: a comparison between urban and rural school students in West Bengal. Indian Journal of Public Health, 56, 155–158. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-557X.99916.

*Sarkhel, S., Sinha, V. K., Arora, M., & Desarkar, P. (2006). Prevalence of conduct disorder in school children of Kanke. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 48, 159–164. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.31579.

Sawyer, M. G., Pfeiffer, S., Spence, S. H., Bond, L., Graetz, B., Kay, D., ... & Sheffield, J. (2010). School‐based prevention of depression: a randomised controlled study of the beyondblue schools research initiative. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02136.x.

Schäfer, M., Korn, S., Smith, P. K., Hunter, S. C., Mora‐Merchán, J. A., Singer, M. M., & Van der Meulen, K. (2004). Lonely in the crowd: Recollections of bullying. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 22, 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1348/0261510041552756.

*Schäfer, M., Stoiber, M., Bramböck, T., Letsch, H., Starch, K., & Sundaram, S. (2018). Participant roles in bullying: what data from Indian classes can tell us about the phenomenon. In P. K. Smith, S. Sundaram, B. A. Spears, C. Blaya, M. Schäfer, & D. Sandhu (Eds.), Bullying, cyberbullying and student well-being in schools: Comparing European, Australian and Indian perspectives. (pp. 130–145). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

*Sethi, S., Setiya, R., & Kumar, A. (2019). Prevalence of school bullying in middle school children in urban Rohtak, State Haryana, India. Journal of Indian Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 15, 13–28.

*Sharma, D., Kishore, J., Sharma, N., & Duggal, M. (2017). Aggression in schools: cyberbullying and gender issues. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 29, 142–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2017.05.018.

*Sharma, D., Mehari, K. R., Kishore, J., Sharma, N., & Duggal, M. (2020). Pilot Evaluation of Setu, a School-Based Violence Prevention Program Among Indian Adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431619899480.

*Shinde, S., Weiss, H. A., Varghese, B., Khandeparkar, P., Pereira, B., Sharma, A. . . . Patel, V. (2018). Promoting school climate and health outcomes with the SEHER multi-component secondary school intervention in Bihar, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England), 392, 2465–2477. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31615-5.

*Shinde, S., Weiss, H. A., Khandeparkar, P., Pereira, B., Sharma, A., Gupta, R., ... & Patel, V. (2020). A multicomponent secondary school health promotion intervention and adolescent health: an extension of the SEHER cluster randomised controlled trial in Bihar, India. PLoS Medicine, 17, e1003021. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003021.

*Skrzypiec, G., Slee, P., & Sandhu, D. (2015). Using the Photostory Method to Understand the Cultural Context of Youth Victimisation in the Punjab. The International Journal of Emotional Education, 7, 52–68.

*Skrzypiec, G., Alinsug, E., Nasiruddin, U. A., Andreou, E., Brighi, A., Didaskalou, E. . . . Yang, C. C. (2018a). Self-reported harm of adolescent peer aggression in three world regions. Child Abuse and Neglect, 85, 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.07.030.

*Skrzypiec, G., Slee, P., Sandhu, D., & Kaur, S. (2018b). Bullying or peer aggression? A pilot study with Punjabi adolescents. In P. K. Smith, S. Sundaram, B. A. Spears, C. Blaya, M. Schäfer, & D. Sandhu (Eds.), Bullying, cyberbullying and student well-being in schools: Comparing European, Australian and Indian perspectives. (pp. 45–60). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, P. K., Sundaram, S., Spears, B. A., Blaya, C., Schäfer, M., & Sandhu, D. (Eds.). (2018). Bullying, cyberbullying and student well-being in schools: Comparing European, Australian and Indian perspectives. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Sousa, V. D., & Rojjanasrirat, W. (2011). Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 17, 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x.

*Suresh, S., & Tipandjan, A. (2012). School bullying victimization and college adjustment. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 38, 68–73.

*Swain, S., Mohanan, P., Sanah, N., Sharma, V., & Ghosh, D. (2014). Risk behaviors related to violence and injury among school-going adolescents in Karnataka, Southern India. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 26, 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2013-0334.

Tarshis, T. P., & Huffman, L. C. (2007). Psychometric properties of the Peer Interactions in Primary School (PIPS) questionnaire. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 28, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.DBP.0000267562.11329.8f.

*Thakkar, N., van Geel, M., Malda, M., Rippe, R. C. A., & Vedder, P. (2020). Bullying and psychopathic traits: a longitudinal study with adolescents in India. Psychology of Violence, 10, 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000277.

Veenstra, R., Lindenberg, S., Zijlstra, B. J., De Winter, A. F., Verhulst, F. C., & Ormel, J. (2007). The dyadic nature of bullying and victimization: Testing a dual-perspective theory. Child Development, 78, 1843–1854. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01102.x.

Verkuyten, M., & Thijs, J. (2002). Racist victimization among children in The Netherlands: the effect of ethnic group and school. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 25, 310–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870120109502.

Wolke, D., Lee, K., & Guy, A. (2017). Cyberbullying: a storm in a teacup? European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 26, 899–908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-0954-6.

World Health Organization. Global school-based student health survey (GSHS). (2001). Available from: https://www.who.int/entity/chp/gshs/methodology/en/index.html. Accessed 25 Dec 2009.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thakkar, N., van Geel, M. & Vedder, P. A Systematic Review of Bullying and Victimization Among Adolescents in India. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention 3, 253–269 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-020-00081-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-020-00081-4