Abstract

This study uses a literature review to probe the prevalence and trends of induced abortions among unmarried women since the 1980s. Premarital pregnancy has become more and more common, and this has pushed the premarital abortion rate still higher. With the premarital abortion rate remaining markedly high in China, the percentage of women who have experienced premarital abortions has risen steadily with the passage of time. Not only has the prevalence of premarital abortions increased in China on the whole, but there is evidence that some young women have had multiple abortions. Premarital abortion is more prevalent in urban areas and among migrants and less-educated women. The huge number of premarital abortions not only signifies a palpable, unmet need for contraceptives, but also represents an immense number of unrealized births. In the years to come, it is imperative to strengthen research into premarital abortions, to optimize the approaches to data collection and analysis, and to improve reproductive health services for unmarried women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Pregnancies and abortions among young adults have been the subject of much research, policy and program discussions, and debate. Young adults attending secondary or tertiary education institutions have entered a critical life stage. During this time, pregnancy, childbearing or induced abortion can not only pose health risks, but also have an impact on young people’s education, employment and future life trajectory, resulting in “diverging destinies” (McLanahan, 2004). Adolescent abortion and birth rates are important indicators for measuring unmet reproductive health needs, and must be considered in setting a global development agenda.

In China, the abortion rate among the "unmarried" outweighs the rate among "adolescents" in ways that have both theoretical and practical significance. Having completed the second demographic transition, developed Western countries tend to have a relatively high tolerance for out-of-wedlock childbirths. Therefore, Western scholars are more inclined to focus their research on unsafe abortions, induced abortions among 15–19 year old girls, and adolescent births, showing little regard for whether the births or abortions occurred in or outside of marriage. In China, however, most people get married; the proportion of Chinese who never marry is very low and has been over the long term (Zhai & Liu, 2020). According to Chinese law, the minimum age of marriage for women is 20 years old, and the average age at first marriage for women has edged up in recent years, reaching 26.3 years in 2016 (He et al., 2018). The majority of unmarried women are adolescents or young adults.

In fact, the pattern of China’s second demographic transition has diverged greatly from those of demographic transitions in Western countries, and such disparities have defined how premarital pregnancies and induced abortions in China are closely linked to young people's attitudes towards marriage and childbearing. Amid the second demographic transition China is undergoing, premarital sex and cohabitation are gaining currency (Ma & Rizzi, 2017). The proportion of Chinese men and women who have engaged in premarital sex has increased substantially across cohorts (Parish et al., 2007). China’s family planning programs have long focused on controlling the fertility behavior of married people, but paid little attention to providing contraceptive information and services for unmarried people (Che & Cleland, 2003; Li et al., 2013). The rate of premarital pregnancies among unmarried women has risen due to the limited access unmarried people have to contraception (Wang et al., 2019). In 2017, 29.5% of Chinese women aged 15–49 had experienced one or more premarital pregnancies, and this rate increased with younger birth cohorts (Qian & Jin, 2020). Although premarital cohabitation is perceived as a prelude to marriage, it does not equate to marriage in the eyes of Chinese people, and premarital childbirths are frowned upon by the society as a whole (Yu & Xie, 2015). The increased number of premarital pregnancies has not led to an increase in single mothers, because if shotgun marriages were not possible, premarital pregnancies have ended in premarital abortion.

The enduring interest of China’s public health sector in research concerning premarital abortions shows no sign of waning, yet many of the existing studies are fragmented, unsystematic and superficial. Most of this research has relied on surgical data derived from medical and health care institutions. Due to the lack of data on premarital abortions and the limited number of articles published in English, China has not been included in recent international comparative studies (Sedgh et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2018). This study reviews Chinese and English language research articles on premarital abortions published since 1980 in an effort to shed light on the following questions: (1) What are the levels and trends of premarital abortions in China; and (2) what are the demographic characteristics of premarital abortions in China? Building upon the answers to these questions, the study discusses the deficiencies of existing research and envision the direction of future research.

2 Definitions and indicators

In this study "unmarried" refers to the absence of legal marriage registration, and "induced abortion" refers to the act of artificially terminating a pregnancy within 14 weeks of conception.

Three categories of premarital abortion indicators are used in this study. The first category consists of indicators taking population as the denominator, such as the premarital abortion rate (the number of premarital abortions per 1000 unmarried women during a certain period of time) and the percentage of women who have experienced premarital abortions.

The second category comprises indicators showing the percentage of premarital pregnancies ending in induced abortions. Induced abortion is a pregnancy outcome, and the changes in the percentage of induced abortions are reflective of shifts in the attitudes of unmarried women towards marriage and fertility. The data for these two categories of indicators was usually taken from surveys conducted in communities or schools (population-based data).

The third category of indicators is taken from an examination of medical service records to determine the numbers of premarital abortions and the percentage premarital abortions are of total abortions. Data can be presented for the percentage of unmarried women among all women who undergo induced abortion, and the percentage of premarital abortions among all induced abortions. The data for these indicators usually come from medical institutions that provide abortion services (clinic-based data).

In view of the purpose of this research and the indicators examined, "unmarried" and "induced abortion" were taken as the keywords to search the China National Knowledge Infrastructure Database (CNKI), and "unmarried", "abortion" and "China" were taken as the keywords to search Ebsco, Elsevier Science, Sage Journal and Springer Journal, a total of 40 articles either in Chinese or in English was obtained.

3 Prevalence and trends

3.1 Premarital abortion rate

The Chinese government routinely discloses the number of induced abortions performed in China every year. Abortion numbers had an upward trajectory in the 1980s and then began trending downward in the 1990s. The number of abortions rose again after 2013, maintaining a level of roughly 9 million per year. The number of induced abortions was 8.96 millionFootnote 1 in 2020, a number equal to 74.7% of the number of births in that year. However, it is important to note that China does not disaggregate the number of induced abortions by marital status and province. Consequently, information on the national and province-specific premarital abortion rates is basically unavailable. A series of national population, fertility and reproductive health surveys conducted since the 1980s have chosen people of childbearing age as respondents, but unmarried people have been excluded from these surveys in most cases. Even in surveys that did include unmarried women, the pregnancy histories of these women were seldom examined.

According to certain surveys of local populations, as early as the 1980s, the abortion rate in Shanghai City had already reached 109‰ in unmarried women aged 15–29 and 93.9‰ in those aged 15–34, and during this decade premarital abortion rate rose with the passage of time. In the period from 1982 to 1988, the abortion rate increased from 4.85‰ to 54.90‰ in unmarried women aged 15–19, from 41.65‰ to 158.62‰ in those aged 20–24, and from 42.73‰ to 93.51‰ in those aged 25–29 (Wu et al., 1990b). In the same period, this rate was only 38.8‰ in the larger group of Chinese women aged 15–44, most of whom were married (Hardee-Cleaveland & Bannister, 1988; Henshaw, 1990).

In 2009, the Survey of Youth Access to Reproductive Health in China conducted by Peking University (2009 PKU Survey) was launched to collect comprehensive information on the reproductive health of unmarried people, and generate nationally representative data. According to the survey results, the abortion rate was 51.9‰ in unmarried people aged 15–24. A more detailed breakdown shows the abortion rate was 23.6‰ in unmarried women aged 15–19 and 95.7‰ in those aged 20–24 (Guo et al., 2019).

According to a 2017 survey of 29 medical institutions from 10 provinces and cities across China, the premarital abortion rate was 17.62‰ in Chinese teenagers aged 15–19. Although the results of this survey can be used to represent the premarital abortion rate at the national level, given the limited scope of the survey and its sampling methods and statistical caliber, the findings likely underestimate the actual rate (Zhu, 2018). In the period from 2010 to 2014, the premarital abortion rate was 24‰ in Asia (Guttmacher Institute, 2018). In 2011, the premarital abortion rate in teenagers aged 15–19 stood at 20‰ in Sweden and the United States, and was above 10‰ in most developed European countries (Guttmacher Institute, 2015). China was on a par with those developed countries.

3.2 Percentage of women who have experienced premarital abortions

Prior to 2003, all couples planning to register for marriage were required to undergo a premarital physical examination. In 1988, 24.5% of 2409 Shanghai women who had the premarital physical examination had experienced premarital abortions (Wu et al., 1990a). A review of nine articles found that during the years 1995–2000, 11%–55% of urban women and 0.8% of rural women who had a premarital physical examination had experienced premarital abortions (Qian et al., 2004). Women attending the premarital physical examination were mainly unmarried women who had a regular boyfriend and planned to get married, and therefore were more likely to engage in premarital sex and get pregnant than unmarried women who were not partnered and preparing to marry.

According to Table 1, figures from population-based surveys show rather low and similar results(3%-5%) in the percentage of unmarried people having experienced premarital abortion, despite the diversity of survey respondents, survey methods and survey years (Zheng & Chen, 2010; Zhou et al., 2013; China Family Planning Association, 2020). The numbers of people engaging in premarital sex, experiencing premarital pregnancies, and having premarital abortions narrows gradually like a pyramid. It should be noted that the above figures only reveal the percentage of unmarried people who had experienced induced abortions at the time the various surveys took place. As the average age at first marriage increases, young people remain single longer and are exposed longer to the risk of premarital abortions. The percentage of women who have premarital abortions is certain to rise further.

The percentage of married women who had had induced abortions was 32.3% in 1997 and 27.3% in 2001 (Chen et al., 2007), and some of these abortions occurred before the women were married. According to the National Population and Reproductive Health (Fertility) Surveys conducted in 1997, 2001, 2006, and 2017, among married women of childbearing age who had been pregnant but had not given birth to any child in the previous 5 years, the percentages who had had induced abortions were 65.4%, 57.6%, 58.6% and 42.9%, respectively, for the four survey years. The percentage of these induced abortions that were premarital rose from 22.0% to 36.1% (Wei et al., 2021), a sign that induced abortions are increasingly taking place before marriage.

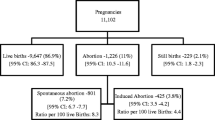

3.3 Percentage of premarital pregnancies ending in induced abortions

After excluding stillbirths and spontaneous abortions, the principal outcomes of premarital pregnancy were induced abortion, shotgun marriage or out-of-wedlock births. The percentage of premarital pregnancies ending in induced abortions can generally be obtained by tracking the outcomes of premarital pregnancies longitudinally, or through cross-sectional surveys of the pregnancy histories of both married and unmarried women. And yet, there are hardly any surveys of these two types in China. Existing studies are based mainly on cross-sectional surveys focused either on groups of unmarried women or on groups of married women. Since out-of-wedlock births are not socially acceptable in China, an overwhelming majority of premarital pregnancies end in induced abortion or shotgun marriage.

According to data from surveys of unmarried people, compared with shotgun marriage, induced abortion is a preferred choice for dealing with premarital pregnancies. The 2009 PKU Survey found that only 0.2% of premarital pregnancies ended in live births, and that most of these pregnancies ended in induced abortions (Zheng & Chen, 2010). According to a survey conducted in Shanghai, Taipei and Hanoi (Vietnam), 94.4% of premarital pregnancies in Shanghai ended in induced abortions (Zhang, 2011). Among the 2012 unmarried pregnant women who visited a hospital in Guangdong Province in the period from 2009 to 2013, 46.8% chose induced abortion, 37.1% had spontaneous abortions, and 16.1% gave birth to their child after a shotgun marriage (Wu & Chen, 2014).

A retrospective survey of married people found that shotgun marriage was the mainstream choice. This follow-up survey of couples married in the period from 1987 to 1995 revealed that 76% of premarital pregnancies ended in shotgun marriage, while 24% ended in induced abortion (Che & Cheland, 2003). Another survey of married couples conducted in 2012 in Foshan City showed that 11.43% of premarital pregnancies ended in out-of-wedlock birth, 62.38% ended in shotgun marriage, and 14.29% ended in induced abortion (Jian et al., 2015).

Surveys of married people have generally found a higher percentage of shotgun marriage as the solution to premarital pregnancy, whilst surveys of unmarried people mostly revealed a higher proportion of induced abortion. These distinctly different survey results are linked to the difference in the groups of respondents. Both types of surveys simply do not include groups of respondents who are likely to have opposite answers, and hence such surveys only yield one-sided results.

Internationally, in countries with relatively complete abortion data, the percentage of pregnancies ending in induced abortions reached as high as 69% in 2010 in females aged 15–19 in Sweden and 67% in 2011 in Denmark, while it was less than 35% in the United States, Israel, and Portugal (Sedgh et al., 2015). In the period from 1975 to 2004, on average in Japan, more than 60% of premarital pregnancies in women aged 15–29 ended in induced abortions and less than 5% ended in out-of-wedlock births. In the United States, however, out-of-wedlock births far outnumbered induced abortions, a result of the different attitudes women have of out-of-wedlock birth, marriage, and abortion (Hertog & Iwasawa, 2011).

3.4 Percentage of total induced abortions that are premarital abortions

In 1982, 28% of 1,031 induced abortions performed in a Beijing maternity hospital were the result of premarital pregnancies (Tien, 1987). In the period from 1982 to 1988, among all induced abortions performed in the five districts and counties of Shanghai, premarital abortions accounted for an average of 24.5%—that is, one out of every four induced abortions was a premarital abortion (Wu et al., 1990b). A sample survey of 79,174 women who had induced abortions in 298 hospitals from 30 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities from 2012 to 2017 found that 31% of the women were unmarried, 61% were migrants, and 28.5% were under the age of 24 (Wu et al., 2015, 2017).

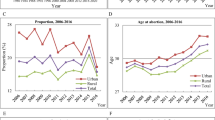

According to Table 2, figures from medical institutions in different cities show notable increases year by year in the percentage of premarital abortions to total induced abortions (Lv et al., 2016; Shao & Zhang, 1989; Wu & Dong, 2006; Zhai et al., 2012; Zhang & Jiang, 2007). However, not all medical institutions showed increases: facilities in certain cities, such as the Maternity Hospital in Xiamen, had declines over time in the percentage of premarital abortions to total induced abortions (Luo et al., 2016).

4 Main characteristics of premarital abortions

4.1 Increasing percentage of females under the age of 20

The minimum legal age for marriage in China is 20, meaning that virtually all abortions performed on women under the age of 20 are assumed to be premarital abortions. Recent surgical registration data from Chinese medical institutions serve as strong evidence that the proportion of women under 20 having abortions has climbed steadily, and this indicates that premarital abortions account for an ever-greater percentage of total abortions.

In the period from 1980 to 1988, the percentage of females in the 15–19 age group who had undergone induced abortions soared from 2.6 to 14.6% in the urban districts of Shanghai and from 2.8 to 38.8% in the suburban counties (Wu et al., 1990b). A survey of medical institutions in Beijing found that the percentage of premarital abortions in females aged 20 or younger increased from 4.19% in 2005 to 10.69% in 2008 (Wang & Gao, 2009). During the period from January 2007 to November 2011, a total of 31,578 women aged 14–49 had first trimester induced abortions in two medical institutions in Tianjin. Among these women, there were 1540 teenagers under the age of 20, who accounted for 4.88% of total number of induced abortions (Yin & Yang, 2012).

4.2 Repeat induced abortions in unmarried youth

In 2000, of the 4547 induced abortions performed on unmarried women aged under 22 in three metropolitan areas, 33% were repeat abortions (Cheng et al., 2004). In 2006, 32.1% of the premarital abortions performed in 27 hospitals in several provinces were repeat abortions (Cheng et al., 2006). A Shanghai-based study found that among 2,343 unmarried women under the age of 24 who had induced abortions, 38.5% had had more than one abortion (Xu et al., 2007).

The 2009 PKU Survey found that among all unmarried women who had experienced induced abortions, 20.9% had had repeat abortions, with some women having as many as four abortions (Zheng & Chen, 2010). In 2011, among all unmarried women who had induced abortions in medical facilities in Beijing, 26.9% had had two or more induced abortions; the average number of induced abortions was 2.32 and the maximum number of induced abortions any of the women had had was eight (Wei & Tang, 2013). According to the 2016 records of medical institutions in Zhejiang Province, 49.07% of unmarried women who had experienced induced abortions had had two or more induced abortions (Fang et al., 2016).

Although unmarried females aged 15–19 had relatively fewer induced abortions, the percentage of 15–19 year old females who had had repeat abortions was strikingly high. A 2017 survey of 29 medical institutions across China found that among 15–19 year old unmarried females who had experienced induced abortions, 18.48% had had repeat abortions (Zhu, 2018). Also conducted in 2017, another survey of 30 provincial hospitals found that among 15–19 year old unmarried females who had experienced induced abortions, 39% had had more than one abortion, and 9% had had three abortions. Young girls from moderately developed or relatively poor areas, as well as migrant girls who had dropped out of school, were more likely to have had repeat abortions (Liu et al., 2017).

4.3 Relatively higher prevalence of premarital abortions in urban areas; migrant and less-educated women are more likely to have premarital abortions

In China, the prevalence of induced abortions is always higher in urban areas than in rural areas, and it is closely correlated with an area’s level of economic development (Chen et al., 2007; Tien, 1987). An early study of induced abortion in China revealed that medical institutions in urban areas performed more premarital abortions than those in rural areas (Liu et al., 2000). In places with more developed, modern economies, young people tend to be more open-minded about sex and are more likely to engage in premarital sex. This means urban young people are more likely to have premarital abortions.

In recent years, the trend for the number of induced abortions shows an increased concentration of abortion in urban areas. In part this is because, in an effort to address safety concerns, the government has tightened the criteria for medical institutions to become certified to perform induced abortions, and hence certain rural medical institutions have been disqualified. At the same hand, rapid urbanization has led to a larger proportion of younger population being concentrated in urban areas. Finally, urban–rural integration and convenient transportation have greatly improved rural women's access to safe abortion procedures in urban areas.

Compared with permanent residents of cities, unmarried migrants face a higher risk of having induced abortions and are considered vulnerable to premarital abortions (He et al., 2012; Zhong et al., 2014). Cross-sectional studies focused on rural-to-urban migrants have identified high rates of abortion among this group, especially among migrants who are young and unmarried. Moreover, this group generally lacks information about sexual and reproductive health issues (Ip et al., 2011). Unmarried migrant women are also at greater risk than urban women of having repeat induced abortions (Xu et al., 2007; Zeng et al., 2015). Insufficient knowledge of contraception and unequal gender-power relations make it difficult for unmarried migrant women to obtain and use effective contraception (Che et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2011).

Lower educational attainment is also linked to a higher probability of having induced abortions for unmarried women (Wu et al., 1990a). Lower levels of education are indicative of lower levels of contraceptive awareness, and less understanding of how and where to obtain contraceptive information and services. This results eventually in a higher probability of women with low educational attainment experiencing premarital abortions. In addition, women with less education are more likely to have repeat induced abortions than better educated women (Cheng et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2007).

5 Discussion and additional research

5.1 Existing studies have been burdened by data constraints

Studies of premarital abortions have long been plagued by the poor integrity and reliability of research data. In addition to the absence of a fully developed system for the registration, reporting, and monitoring of induced abortions, the figures on induced abortions published by the Chinese government are not disaggregated by province, marital status, and demographic characteristics, and the number of induced abortions may be underreported. Among the large- and small-scale sample surveys undertaken by institutions of all kinds, the respondents, survey methods, sampling schemes and quality control procedures are so diverse that it is virtually impossible to compare the results or draw firmly grounded conclusions from these surveys. Overall, this body of research fails to shed light on the overall level and temporal variations of induced abortions.

The data available come mainly from the surgical records of medical institutions. Such data can only reveal the percentage of premarital abortion to total induced abortions; it cannot provide information on the prevalence of women to have premarital abortions. Unmarried women with different characteristics have different needs and preferences for abortion services. The number of induced abortions performed in a given medical institution is dependent on a mix of factors, such as geographic location, age structure of the local population, the level of the institution’s technical services, and its billing standards. If a medical institution only performs a limited number of induced abortions, then the percentage of induced abortions this reveals is likely to be at odds with broader trends or the prevalence of certain groups of women to have abortions. What is still more problematic, data on premarital abortions are not generally accessible in China because the access to data is restricted to some people and not easy to find.

Efforts must be made to strengthen the collection, aggregation, and analysis of data on induced abortions. To this end, we need to improve the quality of abortion data statistics and the aggregation systems used by medical institutions, in order to collect data on the marital status, age, education level, and other relevant factors for women having induced abortions. Data storage systems must safeguard patient confidentiality and personal privacy. National population and fertility surveys should include questions pertaining to induced abortions for unmarried people and such information should be included in survey results. Using enhanced data quality as a foundation, we should make data more accessible, and closely track and monitor premarital abortion trends.

5.2 Level and trends of premarital abortions

A review of the existing literature indicates that the occurrence of premarital abortions has been trending upward. The abortion rate among teenagers in China has been on a par with, or even higher than, rates in developed countries in recent years. The percentage of women having experienced premarital abortions reached 3%–5% in all unmarried women from 2009 to 2020, and was as high as 11%–55% in urban women attending premarital physical examinations during the years 1995 to 2000. Among women who have gotten married but have not given birth to their first child, the number of this group who have had an abortion before marriage is increasing. Most studies analyzing surgical records of medical institutions also point to an upward trend for the percentage of total induced abortions that are premarital abortions.

Premarital abortion is one of the outcomes of premarital pregnancy, which is a consequence of insufficient or improper use of contraception by sexually active young people. Inevitably, in parallel with the acceleration of China's modernization process and the shift in people's attitudes towards sex, premarital sex has become more and more common, leading to the higher incidence of premarital pregnancy. However, existing studies have provided little information about the distribution and trends of premarital pregnancies, or the numbers or percentages that end in shotgun marriages, induced abortions or out-of-wedlock births. The outcome of a premarital pregnancy is dependent on the social context within which it occurs. Given the generally low tolerance Chinese have for out-of-wedlock births, the behavioral choice made in response to premarital pregnancy hinges largely on the willingness and possibility of the two people involved to get married (Tang, 2021).

In order to probe the trends of premarital abortions, we need to investigate the trends for both premarital pregnancies and the behavioral choices (shotgun marriage, out-of-wedlock birth, etc.) that are responses to premarital pregnancy. In the years to come, we must strengthen the research on such behavioral choices, with a greater focus on the decision-making process and the factors that influence those decisions.

5.3 Demographic implications of the shift in the composition of the group of women who have induced abortions

The main reasons women have induced abortions grows out of a need or desire to terminate an unwanted or mistimed pregnancy. The decision to abort is likely to be influenced by a range of social, economic, family, and personal development considerations, including concerns about disruptions to education or career, inability to raise the child, or a bad relationship with the partner (Bankole et al., 1998). The reasons for having induced abortion vary in different countries and cultures, and differ depending on the marital status of the women. In the case of unintended pregnancy, induced abortion can prevent unintended childbirth, whilst in the case of intended pregnancy, it puts an end to the translation of fertility desire into actual reproductive behavior. In fact, induced abortion represents dynamic changes in a woman’s fertility desire, and in her attitudes towards unwanted pregnancy and the mechanism by which her fertility desire is translated into reproductive behavior (Bongaarts & Casterline, 2018).

In the 1990s, most abortions were sought by unmarried women in developed countries, but by married women with a child or children in developing countries, including China (Bankole et al., 1999; Henshaw, 1990). Although the abortion rate among Chinese married women has dropped over the past several years, the decline is becoming increasingly slower (Wei et al., 2021). China's total fertility rate plummeted to an all-time low of 1.3 in 2020. Against a backdrop of steadily declining fertility, the ideal number of children wanted by Chinese women also dropped significantly, standing at 1.75 in 2017 (He et al., 2018). This indicates that a pregnancy that would deliver a second child is likely to be unwanted. At the same time, the Chinese government’s relaxation of fertility policy has provided more freedom for women to have children, creating the conditions necessary for translating unwanted pregnancies into unintended childbirths. The combined effect of these two opposing forces has resulted in an abortion rate that has remained stable or declined in married women. Instead, the rate of induced abortion is increasing among unmarried women and a greater percentage of total abortions are premarital abortions, a sign that China is gradually converging with developed Western countries. Is this convergence objectively inevitable? The shifts in the abortion rate and fertility rate are inextricably linked to macro socioeconomic and cultural factors, and to changes in fertility policy. This is driving the demand for robust studies of the correlations between fertility desire, induced abortion, and reproductive behavior in different population groups.

5.4 Premarital abortion and second demographic transition

Previous studies in China have tended to assume that premarital pregnancies result from improper contraceptive use, and that premarital abortion is the "inevitable" outcome of these pregnancies. These studies failed to take into account the multiplicity of factors that lead to premarital pregnancies, nor have they recognized that premarital abortion is but one of the outcomes of premarital pregnancies, and that the decision to have an induced abortion hinges largely on the attitudes towards marriage and childbearing of the women considering abortion. Such unfounded assumptions and misconception have resulted in ill-considered theoretical explanations of the reasons for premarital abortions.

The spike in premarital abortions in China highlights the desire of unmarried people to postpone marriage and childbearing, and the clear-eyed choices they are making related to marriage and childbearing. Putting premarital abortions in the context of social and cultural changes can help explain young people's attitudes towards marriage and childbearing, and shed light on the connections between their attitudes and the trends of premarital abortions.

Additionally, this points to an increasing number of unwanted pregnancies among unmarried women who are reluctant to give birth to a child out of wedlock. This underscores the strong influence of traditional Chinese culture that advocates "in-wedlock childbirth". Since childbearing is exclusively linked to marriage, the second demographic transitions of China, Japan and South Korea have all demonstrated certain similarities (Lesthaeghe, 2010). We strongly recommend strengthening comparative analysis of the characteristics of the second demographic transitions in China, East Asian countries, and Western European countries. Such research should examine premarital abortion, the outcomes of premarital pregnancy, and other factors that can help to shore up theoretical explanations for premarital abortions.

5.5 Meeting the reproductive health needs of unmarried women

The continuous decline of the marital fertility rate has been the main contributor to the fall in China's TFR; non-marital births contribute little to TFR. The huge number of premarital pregnancies ending in induced abortions represents an immense number of unrealized births. This has without doubt hindered China's effort to raise TFR above its currently low level. On the premise of fully respecting people's reproductive health rights, the government should consider introducing more fertility-friendly policies.

The spike in premarital pregnancies in recent years signifies palpable unmet reproductive health needs among unmarried women. Traditional values concerning marriage are embedded in contraceptive services programs and fertility support policies, and the unmarried are effectively excluded. This review highlights the need for commitment and investment to ensure access to the full spectrum of quality comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care for the unmarried. The government should consider strengthening reproductive health policy support for unmarried women, introducing "youth-friendly" reproductive health information and service policies, and especially promoting interventions that target younger, less-educated migrant women. Efforts should also be made to standardize surgical abortion procedures and to strengthen post-abortion care and contraceptive guidance in medical institutions at all levels. Better care and guidance can help unmarried women avoid repeat premarital abortions and minimize the harm induced abortion can cause.

Notes

Sources: China Health Statistical Yearbook (for the years 2011–2012); China Health and Family Planning Statistical Yearbook (for the years 2013–2017); China Health Statistical Yearbook (for the years 2018–2021). The data about abortion were collected by Chinese Ministry of Health and the National Population and Family Planning Commission respectively before 2013. These two government authorities merged into the National Health and Family Planning Commission in 2013, resulting in statistics showing increased totals for abortions.

References

Bankole, A., Singh, S., & Haas, T. (1998). Reasons why women have induced abortions: Evidence from 27 countries. International Family Planning Perspectives, 24(3), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.2307/3038208

Bankole, A., Singh, S., & Haas, T. (1999). Characteristic of women who obtained induced abortion: A worldwide review. International Family Planning Perspectives, 25(2), 68–77.

Bongaarts, J., & Casterline, B. (2018). From fertility preferences to reproductive outcomes in the developing world. Population and Developments Review, 44(4), 793–809. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12197

Che, Y., & Cleland, J. (2003). Contraceptive use before and after marriage in Shanghai. Studies in Family Planning, 34(1), 44–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/3181151

Che, Y., Dusabe-Richards, E., Wu, S., Jiang, Y., Dong, X., Li, J., Zhang, W., Temmerman, M., Tolhurst, R., & INPAC group. (2017). A qualitative exploration of perceptions and experiences of contraceptive use, abortion and post-abortion family planning services (PAFP) in three provinces in China. BMC Women’s Health, 17, 113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0458-z

Chen, G., Pang, L., & Zheng, X. (2007). Level, trend and influencing factors of induced abortions in China. Chinese Journal Population Science, 5, 49-59+95-96. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-7881.2007.05.009 in Chinese.

Cheng, Y., Guo, X., Li, Y., Li, S., Qu, A., & Kang, B. (2004). Repeat induced abortions and contraceptive practices among unmarried young women seeking an abortion in China. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 87(2), 199–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.06.010

Cheng, Y., Wang, X., Lv, Y., Cai, Y., Li, Y., Guo, X., Huang, L., Xu, X., Xu, J., & Francoice. (2006). Study on the risk factors of repeated abortion among unmarried adolescents. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 27(8), 669–672. in Chinese.

China Family Planning Association. (2020). Survey report on the sexual and reproductive health of college students. https://www.163.com/dy/article/FC1DJV4T0514CJV0.html. Accessed 7 May 2020. in Chinese.

Fang, Q., Chen, Y., Wu, D., Wang, B., & Fu, X. (2016). Survey on induced abortions in unmarried women. Zhejiang Journal of Preventive Medicine., 28(1), 82–84. in Chinese.

Guo, C., Pang, L., Ding, R., Song, X., Chen, G., & Zheng, X. (2019). Unmarried youth pregnancy, outcomes, and social factors in China: Findings from a nationwide population-based survey. Sexual Medicine, 7(4), 396–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2019.07.002

Guttmacher Institute. (2015). Adolescent Pregnancy and Its Outcomes across Countries. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/adolescent-pregnancy-and-its-outcomes-across-countries. Accessed 9 Feb 2017.

Guttmacher Institute. (2018). Abortion in Asia. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/abortion-asia. Accessed 26 Mar 2020.

Hardee-Cleaveland, K., & Bannister, J. (1988). Fertility policy and implementation in China, 1986–1988. Population and Development Review, 14, 245–268. https://doi.org/10.2307/1973572

He, D., Zhang, X., Zhuang, Y., Wang, Z., & Yang, S. (2018). China fertility report, 2006–2016: An analysis based on China fertility survey 2017. Population Research, 42(06), 35–4. in Chinese.

He, D., Zhou, Y., Ji, N., et al. (2012). Study on sexual and reproductive health behaviors of unmarried female migrants in China. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 38(4), 632–638. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01753.x

Henshaw, S. K. (1990). Induced abortion: A world review. Family Planning Perspectives, 16(2), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/1966428

Hertog, E., & Marriage, I. M. (2011). Abortion, or unwed motherhood? How women evaluate alternative solutions to premarital pregnancies in Japan and the United States. Journal of Family Issues, 32(12), 1674–1699. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11409333

Ip, W., Chan, M., Chan, D., & Chan, C. (2011). Knowledge of and attitude to contraception among migrant woman workers in mainland China. Journal of Clinical Nursing., 20(11–12), 1685–1695. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03404.x|

Jian, M., Li, X., Zhou, S., Ye, X., Xu, Y., & Xu, Y. (2015). Premarital pregnancies in married women of childbearing age and influencing factors. China Public Health, 31(3), 282–284. https://doi.org/10.11847/zgggws2015-31-03-08 in Chinese.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review., 36(2), 211–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00328.x

Li, J., Temmerman, M., Chen, Q., Xu, J., Hu, L., & Zhang, E. (2013). Review of contraceptive practices among married and unmarried women in China from 1982 to 2010. The European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care, 18(3), 148–158. https://doi.org/10.3109/13625187.2013.776673

Liu, J., Wu, S., Xu, J., Temmerman, M., & Zhang, W. (2017). Repeat abortion in Chinese adolescents: A cross-sectional study in 30 provinces. The Lancet., 390(S4), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33155-0

Liu, M., Liang, W., Zhang, K., Su, S., Yang, W., Chen, Q., & Jiang, C. (2000). A cross-sectional study on the abortion status and risk factors of 609 women of child-bearing age. Chinese Journal of Public Health, 5, 69–70. https://doi.org/10.11847/zgggws2000-16-05-50 in Chinese.

Liu, Z., Zhu, M., Dib, H. H., Li, Z., Shi, S., & Wang, Z. (2011). Reproductive health knowledge and service utilization among unmarried rural-to-urban migrants in three major cities China. BMC Public Health, 11, 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-74

Luo, Z., Quan, S., Chai, D., & Zhang, W. (2016). Cohort records study of 19,655 women who received post-abortion care in a tertiary hospital 2010–2013 in China: What trends can be observed? BioMed Research International. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/3629451

Lv, Y., Shi, W., Zhang, N., Jia, L., Wang, H., & Nie, W. (2016). Analysis on the causes of abortion among women of childbearing age from 2010 to 2015. Journal of Hebei Medical University, 37(9), 1030–1033. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1007-3205.2016.09.010 in Chinese.

Ma, L., & Rizzi, E. (2017). Entry into first marriage in China. Demography Research, 37, 1231–1244. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2017.37.36

McLanahan, S. (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41(4), 607–627. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2004.0033

Parish, W., Laumann, E., & Mojola, S. (2007). Sexual behavior in China: Trends and comparisons. Population and Development Review, 33(4), 729–756. https://doi.org/10.2307/25487620

Qian, X., Tang, S., & Garner, P. (2004). Unintended pregnancy and induced abortion among unmarried women in China: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 4(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-4-1

Qian, Y., & Jin, Y. (2020). Premarital pregnancy in China: Cohort trends and educational gradients. Studies in Family Planning, 51(3), 273–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12135

Sedgh, G., Finer, L. B., Bankole, A., Eilers, M. A., & Singh, S. (2015). Adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: levels and recent trends. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(2), 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.007

Shao, S., & Zhang, H. (1989). A problem that can’t be ignored—a survey on premarital pregnancies. Popul Journal, 1, 28–30. in Chinese.

Singh, S., Remez, L., Sedgh, G., Kwok L. & Onda, T. (2018). Abortion Worldwide 2017: Uneven progress and unequal access. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/abortion-worldwide-2017. Accessed 20 Mar 2020.

Tang, M. (2021). Why unmarried young people terminate pregnancy: Findings from a qualitative study in China. Paper presented at XXIX International Population Conference (IPC2021), Dec 5–10. 2021. https://ipc2021.popconf.org/uploads/210253. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

Tien, H. Y. (1987). Abortion in China: Incidence and implications. Modern China, 13(4), 441–468. https://doi.org/10.2307/189264

Wang, J., & Gao, S. (2009). Investigation and analysis of influential factors related to high risk induced abortion. Chinese Journal of Family Planning, 2, 99–101. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-8189.2009.02.010 in Chinese.

Wang, M. Y., Zhang, W. H., Mu, Y., Temmerman, M., Li, J., & Zheng, A. (2019). Contraceptive practices among unmarried women in China, 1982–2017: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care, 24(1), 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/13625187.2018.1555641

Wei, Z., & Tang, M. (2013). Repetitive abortions and emergency contraception among unmarried female adolescents in Beijing: Based on data collected from seven hospitals in Shunyi and Changping districts. Collection of Women’s Studies, 5, 43–49. in Chinese.

Wei, Z., Yu, D., & Liu, H. (2021). Induced abortion among married women in China: A study based on the 1997–2017 China Fertility Surveys. China Population and Development Studies, 5(5), 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-021-00079-5

Wu, H., & Dong, L. (2006). Distribution of induced abortions in women of childbearing age and influencing factors in 1994 and 2003. Chinese Journal of General Practitioners, 5(1), 46–47. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-7368.2006.01.017 in Chinese.

Wu, S., Temmerman, M., et al. (2015). Induced abortion in 30 Chinese provinces in 2013: A cross-sectional survey. The Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00596-6.

Wu, S., Wang, K., & Dong, J. (2017). WP3 quantitative survey and its key findings. In Zheng, W. & Che,Y. (Eds.), Interventions into post-abortion family planning services in China—Design and implementation of an EU FP7 Funded INPAC Project (pp. 72–74). China Population Publishing House. in Chinese.

Wu, Y., & Chen, J. (2014). Outcomes and psychological analysis of 2012 premarital pregnancies. Shenzhen Journal of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, 24(02), 59–60. in Chinese.

Wu, Z., Gao, E., Gu, X., Hong, W., Xu, S., & Liu, C. (1990a). Survey on the sexual experience, pregnancies and induced abortions in unmarried women in Shanghai. Chinese Journal of Public Health, 6(11), 481–483. in Chinese.

Wu, Z., Gu, X., Gao, E., Xu, S., Wang, M., & Hong, W. (1990b). Rate and trend of induced abortions in unmarried women in Shanghai. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 5(41–43), 34. in Chinese.

Xu, J., Huang, Y., & Cheng, L. (2007). Factors in relation to repeated abortions among unmarried young people in Shanghai. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 28(08), 742–745. https://doi.org/10.3760/j.issn:0254-6450.2007.08.004 in Chinese.

Yin, Z., & Yang, H. (2012). The investigation of artificial abortion of adolescents under the age of 20 in Tianjin urban and suburban. Journal of International Reproductive Health/family Planning, 31(6), 3. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-1889.2012.06.008 in Chinese.

Yu, J., & Xie, Y. (2015). Cohabitation in China: Trends and determinants. Population and Development Review, 41(4), 607–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00087.x

Zeng, J., Zou, G., Song, X., & Li, L. (2015). Contraceptive practices and induced abortions status among internal migrant women in Guangzhou, China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 15, 552. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1903-2

Zhai, Z., & Liu, W. (2020). Do the Chinese really not want to get married? From the cohort perspective. Exploration and Free Views, 2, 122-130+160. in Chinese.

Zhai, J., Li, L., Yue, J., Long, Q., & Tang, J. (2012). Analysis on abortion age and marital status of childbearing age of women in Nanning city. Chinese Nursing Research, 26(11), 1015–1016. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1009-6493.2012.11.027 in Chinese.

Zhang, L., & Jiang, Q. (2007). Analysis of women having induced abortions. China Clinical Practical Medicine, 4, 2. in Chinese.

Zhang P. (2011). Sexual behavior patterns in unmarried teenagers in three Asian regions and influencing factors, Ph.D dissertation. Fudan University. Shanghai. China. in Chinese.

Zheng, X., & Chen, G. (2010). Survey report on the accessibility of reproductive health for Chinese adolescents. Population and Development., 16(3), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-1668.2010.03.001 in Chinese.

Zhong, F., Zhao, W., & Zhou, Y. (2014). Analysis of family planning surgery in Haidian district from 2008 to 2013. Chinese Journal of Woman and Child Health Research, 6(1), 052–1054. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-5293.2014.06.049 in Chinese.

Zhou, Y., Xiong, C., Xiong, J., Shang, X., Liu, G., Zhang, M., & Yin, P. (2013). A blind area of family planning services in China: Unintended pregnancy among unmarried graduate students. BMC Public Health, 13, 198. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-198

Zhu X. (2018). Current status, influencing factors and post-abortion services relating to the repeated induced abortions among adolescents aged 15–19 in China. Unpublished Work. https://www.cmcha.org/detail/15226545927225919379.html. Accessed 29 Apr 2018. in Chinese.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no potential conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, M. Induced abortion among unmarried women in China. China popul. dev. stud. 6, 78–94 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-022-00105-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-022-00105-0