Abstract

This study uses four sets of data from China Fertility Surveys completed during the years 1997–2017 to analyze the trend of induced abortion, with a focus on the twenty-first century. Married women of reproductive age who had a history of pregnancy during the 5 years prior to participating in a survey were the research object. The study also examines the variation of abortion proportions among different subgroups during different time periods, including an examination of the number and gender of children, place of residence, and contraceptive use of women who had induced abortions. The results show that the occurrence of induced abortion has decreased gradually, and that the risk of induced abortion was higher for those who had given birth to fewer children. However, induced abortion among women with two children has increased in recent years. It is noteworthy that induced abortions among childless premarital women have continued to increase in recent years, and that the sexual and reproductive health problems of adolescents remain of great concern. The occurrence of induced abortions after childbirth increased for those with one or two children, showing that the unmet need for contraception after childbirth should receive more attention. In addition, sex-selective abortion has been decreasing gradually, but still exists today.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Induced abortion is a medical procedure that allows artificial termination of inappropriate or unintended pregnancies. Induced abortion has received widespread attention because it is a reproductive health issue and related to women's physical and mental health. An earlier study reveals that the induced abortion rate among Chinese women aged 15–44 climbed from 23.1 to 54.9% during the years 1971–1982 (Kang et al. 1991). Such a rise in the induced abortion rate drew much attention to reproductive health issues from relevant government departments and researchers. The nationwide fertility surveys in 1988, 1997, 2001, 2006 and 2017 subsequently provided solid data for understanding the reproductive health status of women of reproductive age, and included information about induced abortion.

Some scholars have taken data from 1988, 1997 and 2001 surveys to analyze the trends in induced abortion from the 1970s to the 1990s (Chen, 2002; Chen et al. 2007; Kang et al. 1991; Pan, 2004; Qiao, 2002). The incidence of induced abortion among married women displayed an upward trend and then a downward trend during this period, with turning point occurring in the mid to late 1990s. Data from the 2018 China Health Statistics Yearbook show that from the 1980s to the early 1990s, the average number of induced abortions performed in China exceeded 10 million per year, peaking at 14.37 million in 1983. From the mid to late 1990s, the number of induced abortions fluctuated between 6 and 8 million per year. During the first few years after 2000, the number of induced abortions was basically commensurate with that in the mid to late 1990s, though it surged to 9.17 million per year in 2008. Some reports claiming more than 10 million induced abortions per year in several years before 2010 (Wu and Qiu, 2010). During the period from 2009 to 2013, the number of induced abortions declined slightly, settling at somewhat more than 6 million per year. Following the fertility policy adjustment at the end of 2013, the number of induced abortions rose sharply to more than 9.6 million per year in the period 2014–2017.

According to published statistics, the number of induced abortions yearly has seen significant fluctuations over the past decade. The trend for induced abortion since 2001 is not clear due to a lack of related research. The two fertility surveys conducted in 2006 and 2017 have provided adequate information to support such research into the trends for induced abortion during this period. This study intends to use information from the four surveys that were completed during the years 1997–2017 to illuminate the trends in induced abortion in China since the beginning of the twenty-first century, and to draw out more detailed characteristics of induced abortion during different periods by examining the number and gender of children, place of residence, and contraceptive use of women who had induced abortions.

2 Data and methodology

2.1 Data source

The data used in this study comes from the 1997 National Population and Reproductive Health Survey and the 2001 National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Survey conducted by the State Family Planning Commission (SFPC), the 2006 National Population and Family Planning Survey conducted by the National Population and Family Planning Commission (NPFPC), and the 2017 China Fertility Survey conducted by the National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC).

The 1997 National Population and Reproductive Health Survey was conducted in November, 1997, at 1041 sample sites in 337 counties (cities, or districts) of 31 provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities across China. A stratified, multi-level, cluster and proportional sampling method was used, and a total of 15,213 women of reproductive age were interviewed (National Family Planning Commission, 1998).

Carried out from July to September 2001 at the same 1041 sample sites in 337 counties (cities, or districts) used by the 1997 National Population and Reproductive Health Survey, the 2001 National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Survey interviewed a total of 39,586 women of reproductive age (National Family Planning Commission, 2002).

Employing a three-stage probabilities proportional to size (PPS) sampling method, the 2006 National Population and Family Planning Survey was conducted in August 2006 in 120 statistical monitoring counties (cities, or districts) of 31 provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities across China, and a total of 33,209 women of reproductive age were interviewed (NPFPC, 2007).

The 2017 China Fertility Survey opted for a stratified, three-stage PPS sampling method, and was conducted in July 2017 at 12,500 village/neighborhood-level sample sites in 6,078 townships (towns, or sub-districts) of 2737 counties (cities, or districts) in 31 provinces/autonomous regions/ municipalities across China. The sample size was nearly 250,000 people (Zhuang et al. 2019), of whom 180,816 were women of reproductive age. The data from the 1997, 2001 and 2006 surveys was not weighted. In order to ensure consistency with the data from these three surveys, the data from the 2017 survey was also unweighted. The number of women aged 15–60 surveyed in 2017 was 249,946, and after excluding women aged 50–60, the number of women of reproductive age was 180,816.

The figures and tables in this paper are all derived from the four fertility surveys noted above.

2.2 Main variables and the samples

In the four nationwide fertility surveys from 1997 to 2017, information on induced abortion could be found in the section of the surveys about pregnancy history. The time interval separating the first three surveys was about 5 years,Footnote 1 with survey targets being women of reproductive age (15–49); however, only married women were asked about their pregnancy history. The 2017 survey was completed more than a decade after the last of the previous surveys. This survey interviewed women aged 15–60, and both married and unmarried women were asked about their pregnancy history. Because married women aged 15–49 participated in all of the four surveys, and because this group is especially relevant to our analysis of induced abortion, this study only includes married women aged 15–49.

In order to minimize the impact of memory bias and generate a series of continuous, consistent data for analysis, we selected married women of reproductive age who had been pregnant at some point during the 5 years previous to the sample survey they participated in. Our sample population was composed of married women of age 15–49 who were pregnant in the period from November 1992 to October 1997, from July 1996 to June 2001, from August 2001 to July 2006, or from July 2012 to June 2017.

As shown in Table 1, after moving from the number of women of reproductive age to married women of reproductive age, and further to married women of reproductive age who were pregnant during the 5 years prior to participating in one of the surveys, the final sizes of samples for each of four surveys was 3,879 for 1997, 8697 for 2001, 7256 for 2006 and 46,814 for 2017. The proportion of married women of reproductive age who were pregnant during the 5 years prior to participating in one of the surveys to all married women of reproductive age was between 25 and 31 percent.

Table 2 is a profile of the four samples. The age structures of the samples show the proportion of older married women of reproductive age increases with each survey, a trend which is consistent with the increase of average age of women of reproductive age in China. More women received higher education in recent years due to China’s development of educational resources. The proportion of urban residents increased as a result of rapid urbanization in twenty-first century. The higher proportion of second children in 2017 reflects the policy effects of the “Universal Two-Child Policy” implemented in January 2016. Another significant change in 2017 was the large increase in the proportion people using short-acting contraceptives (mainly condoms).

“Induced Abortion Worldwide” utilized the proportion of the number of induced abortions to the number of pregnancies within a period of time to analyze the global trends in induced abortion during the years 1990 to 1994 and 2010 to 2014 (Guttmacher Institute, 2018). We intend to use the proportion of pregnant women who had induced abortion within a certain period of time for analysis. Specifically, we took married women of reproductive age who were pregnant during the 5 years prior to participating in one of the surveys studied in this paper as the denominator and those who had an abortion in the 5 years prior to participation in any of the surveys are used as the numerator, thereby calculating the proportion of induced abortions among married women of reproductive age who participated in any of the surveys studied and were pregnant during the 5 year period prior to survey participation.

This study mainly uses a descriptive analysis. For convenience, unless otherwise specified, references to married women of reproductive age below shall refer to married women of reproductive age who were pregnant in the 5 years prior to survey participation, and the proportion of induced abortions for a particular survey year shall refer to the proportion of married women of reproductive age who participated in that survey and were pregnant and opted for induced abortion during the 5 year period prior to their survey participation.

3 Main findings

3.1 Changing trends in induced abortion

3.1.1 Gradual decline in the proportion of induced abortions

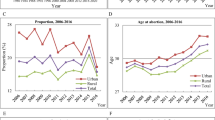

As shown in Fig. 1, the four surveys show that the proportion of induced abortions has edged down gradually. It began its downward track after reaching a peak in the mid to late 1990s, well mirroring the downward trend in unintended pregnancy among married women of reproductive age. However, it can also be observed that the rate of decline in the proportion of induced abortions has slowed, and this is especially evident in the decline between the 2006 and 2017 surveys.

Furthermore, the four surveys point to the fact that among all abortions, one-time abortions accounted for more than 80% of the total, meaning that an overwhelming majority of married women of reproductive age who underwent induced abortion did so only once. In view of this, all subsequent analyses of the occurrence time of abortions (i.e., before or after marriage, before or after childbirth, etc.) will focus on married women of reproductive age who had one induced abortion.

In the mid-1990s, the Chinese government began to advocate a people-centered approach by strengthening the effective provision of contraceptive services in the work of family planning and piloting “Quality of Care Project (QoC)” in family planning services underpinned by informed choice (Kaufman et al. 2006; Zhang, 2000). At the same time, these changes in approach to family planning were occurring, women's fertility intentions were undergoing a profound change and having less children was becoming the common wish of a majority of women. With improved contraceptive services and decreased childbearing intentions combined with the effects of other changes at the social, governmental, and individual levels, the proportion of induced abortions in the late 1990s declined significantly.

With the advent of the twenty-first century, QoC in family planning services developed into a national policy. In 2002, China initiated a nationwide campaign of building advanced units to provide family planning services. Under the QoC framework, client-centered family planning services that integrated notions of rights protection and gender equality with pioneering management and service practices not only enhanced the level of reproductive health services by optimizing the service environment, enhancing service facilities and equipment, and improving service quality and service capabilities, but also put greater emphasis on the needs and accessibility of services for vulnerable groups, including migrants and teenagers. The package of measures implemented in this period played a crucial role in bringing down the induced abortion rate.

China has been adjusting and improving fertility policy since 2010. More relaxed fertility policy has provided an alternative to induced abortion for unintended pregnancies caused by contraceptive failure, thereby reducing the incidence of induced abortions. However, beginning with implementation of the Universal Two-Child Policy in 2016 another risk surfaced–unintended pregnancies caused by less awareness of effective contraception. One study revealed that the years 2010 to 2016 saw an upsurge in the use of condoms, although the use of short-acting contraceptive methods has been found closely bound up with the incidence of induced abortions (Zou et al. 2018). Changing patterns of contraceptive usage may account for the increase in the proportion of induced abortions (Zong et al. 2020).

The “Outline of the ‘Healthy China 2030' Plan” and the “Healthy China Action (2019–2030)” highlighted the protection of women's health and the provision of family planning services. China has incorporated family planning with maternity and childcare health services, strengthened technical services to assist couples in the selection of contraceptive methods, and included the provision of free contraceptives as a part of basic public health service coverage. However, there is still much room for improvement of the grass-roots reproductive health service network, and the promotion, consultation and service provision for contraceptives. Presently, despite ample positive factors contributing to the decreased incidence of induced abortion, there are also several risk factors that are cause for concern. But in general, positive factors outnumber risk factors, thereby hastening the further decline in the proportion of induced abortions.

3.1.2 Increased number of premarital abortions

All of the four surveys found that some childless married women had had an induced abortion, and some had induced abortion before marriage. The sample sizes of childless married women in the four surveys were 104, 231, 181 and 664, respectively, and among these women 68, 133, 106 and 285 had had an induced abortion, accounting for a relatively high share.

As shown in Fig. 2, a majority of childless women had their induced abortion after marriage. However, it should be noted that the proportion of premarital abortions exhibited an upward trend during our study period. The proportion of premarital abortions among childless married women climbed from 22.0% in the 1997 survey to 36.1% in the 2017 survey. For women already have children, induced abortion before marriage mostly happened beyond 5 years before the survey year, therefore we only include childless women in Fig. 2.

3.1.3 Lower incidence of induced abortion is associated with women who have more children

As shown in Fig. 3, the analysis of women who had given birth shows that in most cases, the proportion of induced abortions was lower among women who had given birth to more children. Only the 2006 survey found that the proportion of induced abortions in women who had given birth to 2 children was lower than that of those who had given birth to 3 children. Over time, the surveys show that, regardless of whether they had one, two, or three children, the proportion of induced abortions in married women of reproductive age went down gradually. The only exception was that the proportion of induced abortions among married women with two children was higher in 2017 than it was in 2006.

The four surveys reveal that the incidence of induced abortion in married women with one child was higher than it was for those with two or more children in both urban and rural areas, and the incidence of induced abortion in urban women with one child was much higher than it was for women in rural women with one child. However, by 2017, the urban–rural gap had narrowed significantly. The first three surveys show that the proportion of induced abortions in rural women with two children edged down steadily, and in 2017, the proportion of induced abortions for urban and rural women with two children stood at 18.6% and 18.3% respectively, very close to each other.

A significant majority of married women with two children claimed that two was exactly the number of children they desired. These women tended to use more effective long-acting contraceptive methods than did those with one child. The four surveys show that the proportions of married women with one child who used long-acting contraceptive methods were 76.2%, 73.7%, 60.6% and 16.8%, respectively, for the four surveys. These were lower than the proportions of those with two children who also used long-acting contraceptive methods (88.2%, 86.6%, 82.0% and 41.0% respectively). It can therefore be concluded that when married women had given birth to the desired number of children, they were more likely to use more effective long-acting contraceptive methods, and hence less likely to have an induced abortion.

3.2 Childbearing and induced abortions

3.2.1 The incidence of induced abortion among married women with one child is related to gender of the child and place of residence

Figure 4 shows the proportions of induced abortions among married women with one son or one daughter. All four surveys show that the incidence of induced abortion in married women with one son was higher than that in those with one daughter. Over time, the two proportions both edged down, yet the gap between the two widened. Furthermore, the two proportions fell at roughly the same pace, thereby contributing to the steady decline in the proportion of induced abortions among married women with one child.

As shown in Fig. 5, the decreased incidence of induced abortion among married women with a single child was mainly attributable to the lowered incidence of induced abortions in urban areas. The first three surveys show that the proportion of urban women with either one son or one daughter having induced abortions was significantly higher than that of rural women. The proportion of urban women trended downward over time during these three surveys, while that of rural woman remained relatively constant. By 2017, the incidence of induced abortion of urban women with either one son or one daughter was basically on a par with that of rural women. Furthermore, in rural areas, the proportion of induced abortions of married women with one son was always higher than that of married women with one daughter, and the difference between the two remained relatively stable. It can be seen that in rural areas, there was a greater difference in the incidence of induced abortion between married women with one son and those with one daughter.

The incidence of induced abortion of urban women with one child was higher than that of their rural peers. This might be attributed to urban–rural differences in the use of effective contraceptives. The first three surveys show that at the time of the respective surveys, the proportion of urban women using long-acting contraceptives was lower than that of rural women, with the gap ranging from 14 to 17%. This likely pushed up the incidence of induced abortion among urban women. In the 2017 survey, the gap between the two had narrowed to approximately 9 percentage points.

Figure 6 breaks down the proportions of married women of reproductive age who had induced abortions before or after their first child was born, and by urban and rural areas and the gender of the only child. The first three surveys show that the incidence of induced abortion was higher for rural women with one daughter. Although rural women with one daughter were eligible to have another child, some of them opted for induced abortion instead of giving birth to the second child. This might be related to sex selection due to a preference for sons (Liu., 2005).

Proportion of induced abortions before or after childbirth among one-child women by child sex and place of residence. Note: “Before childbirth” means that the date of the abortion was before the birth of the first child, and “after childbirth” means that the date of abortion was after the birth of the first child

In the first three surveys, the incidence of induced abortion among married women who had not given birth to either one son or one daughter was found to be significantly higher in urban areas than in rural areas. The incidence of induced abortion among women who had already had a child is understandable, but a high incidence of induced abortion among married women who were childless suggests a close connection with sex selection efforts (Pang et al. 2008).

3.2.2 The incidence of induced abortion in women with two children is related to the gender of the first child

We divided married women with two children into four groups: those with two sons, two daughters, one son plus one daughter, and one daughter plus one son. It should be noted that in the first three surveys, most married women with two children lived in rural areas, while in the 2017 survey, married women with two children could be found in both urban and rural areas. As shown in Fig. 7, the first three surveys show that: (1) the highest incidence of induced abortion was found in married women with either two sons or two daughters; (2) the proportion of induced abortions of married women who had one son first and then one daughter was roughly on a par with that of married women with either two sons or two daughters; and (3) the lowest proportion of induced abortions was found among married women had one daughter first and then one son.

There seems to be a strong correlation between the incidence of induced abortion in married women with two children and the gender of the first child. We found that among married women with two children, most induced abortions occurred after women already had two children or between the birth of the first and second child (the proportion of married women having an abortion before the birth of their first child was less than 3%). The first case, abortions among women who already had two children, was the most common. Figure 8 shows the proportion of induced abortions in married women with two children by the gender combination of their children. The first three surveys show that among married women with two children: (1) those who had had two children, the first of whom or both of whom were boys, had a higher incidence of abortion after the birth of the second child; and (2) those who had had two children, the first of whom was a girl had a higher incidence of induced abortion between the birth of the first and the second child (including the case of two daughters and the case of one daughter preceding the son). The higher incidence among the first group might be a result of these women having fulfilled their desire to have two children, while the higher incidence among the second group might be the result of sex selection.

Proportion of induced abortions occurring between the first and second birth or after the second birth among married women with two children, by the sex of the child. Note: "Between two births" means that the date of the abortion was after the birth of the first child, but before the birth of the second child; and "after two births" means that the date of the abortion was after the birth of two children

Sex ratio at birth (SRB) of second parity in different gender scenarios for the first birth can also be used to examine the connection between sex selection and induced abortion. The first three surveys show that in rural families with two children, the first of whom is a boy, the second-birth SRBs were 106.2 in the first survey, 112.8 in the second, and 97.0 in the third. While the 2001 survey was out of the normal range, the second-birth SRB in 1997 was within the normal range (103–107), and that in 2006 was below the normal range. However, when the first child was a girl, the second-birth SRB reached 200.5, 211.9 and 206.1, respectively, in the first three surveys, all far above normal. The 2017 survey shows that in both rural and urban areas, the second-birth SRB was within the normal range when the first child was a boy, but was still higher than normal when the first child was a girl, despite a sharp drop from the previous three surveys.

3.2.3 Increasing incidence of induced abortion among married women with two children and narrowing gaps between different gender combinations of children in recent years

Figure 7 shows that, in the first three surveys, the proportion of induced abortions among married women with two children exhibited a declining trend for all gender combinations of children. However, the 2017 survey revealed a proportion of induced abortion higher than the level of 2006 and close to the level of 2001 for all gender combinations of children, indicating that in recent years, the incidence of induced abortion has been on the rise in married women who have already given birth to two children. Figure 8 also shows that in the first three surveys, regardless of the gender of their children, the incidence of induced abortion, whether between the first and second births or after two births, exhibited a downward trend, with the incidence of induced abortion after two births descending faster. However, in 2017, the incidence of induced abortion in married women with two children increased significantly, both between the first and second births and after two births, for all gender combinations of children, with the incidence of induced abortion after two births seeing the greater increase.

It can also be observed from Fig. 7 that in the first three surveys, there were significant gaps in the incidence of induced abortion among the four gender combinations of children. In the 2017 survey, however, the incidences of induced abortion for all groups were on the rise and the gaps had been narrowed, pointing to the limited relationship between the incidence of induced abortion in 2017 among women with two children and the gender structure of their children. Figure 8 shows that in the 2017 survey, the incidence of induced abortion after two births was slightly higher for the gender combination of one daughter followed by one son, but basically remained undifferentiated among the other three gender combinations. The incidence of induced abortion occurring between the births of the first and second child was not much different among all groups. This apparently signifies the diminishing impact the gender of children has on the incidence of induced abortion among married women with two children in recent years.

4 Conclusions and discussions

The analyses in this paper show that the incidence of induced abortion among married women of reproductive age is now on a downward curve, unequivocal evidence of China's remarkable achievements in its steady push for reproductive health. The findings are also consistent with previous studies about a downward trend of induced abortion in early and mid 1990s (such as: Chen, 2002; Pan, 2004). However, it should also be noted that the fewer the number of children born, the higher the incidence of induced abortion. Detailed analysis found that from 2012 to 2017, the proportion of induced abortions decreased steadily for married women with one child and remained stable for married women with three or more children, but surged among those with two children.

A review of the four survey results shows the outcome of efforts to eliminate unnecessary induced abortions, but suggests that potential risks still exist. With the strategic initiative of "Healthy China" guiding the merger of the health and family planning systems to improve services, we should pay special attention to the following five factors as part of our efforts to reduce the incidence of induced abortion and promote reproductive health:

-

1.

The increasing incidence of induced abortion among married women with two children following the adjustment of the fertility policy. After the adjustment of the fertility policy, some older married women became pregnant with a second child, and the probability of abnormal fetal growth in these women could account for the increasing incidence of induced abortion in married women with two children. The analyses in this paper also reveals that the increasing incidence of induced abortion after two births points to unmet contraceptive needs among married women with two children.

-

2.

Promote the use of highly effective contraceptive methods and improve the accessibility of contraceptive services. We found that, among married women with one child and those with two children, the proportion of women using less effective contraceptive methods was on the rise. This can obviously lead to unintended pregnancies and push up the incidence of induced abortion. It is possible that adjustments to fertility policy have made people less attuned to the importance of effective contraceptive methods and this may be behind the rise in unintended pregnancies and abortions. The lack of a strong push for the use of effective contraceptive methods and the less satisfactory access to contraceptive services in recent years may also be attributable to changes in fertility policy.

-

3.

Sex-selective induced abortion still exists amid the shift of fertility intentions. China has kicked off a broad array of interventions aimed at improving women's social status and enhancing women's reproductive health, thereby contributing to the gradual decline in sex-selective induced abortions. Nevertheless, sex-selective induced abortions have not disappeared as shown by our research findings, and there is still a long way to go to build a social environment that enables gender equality.

-

4.

There are unmet reproductive health needs among unmarried young people. This study found that a considerable number of childless married couples had experienced premarital induced abortion, and this number appears to be trending steadily higher. This spotlights the unmet reproductive health needs of unmarried young people.

-

5.

Promote reproductive health services in the provision of basic public health services. With the integration of various service resources, family planning services have been incorporated into the basic public health service system. However, the integration of the two types of services is still subject to ongoing adjustments. The availability of contraceptive services is limited, service quality is inadequate, and basic skills required for delivering family planning management services are lacking at the grassroots level. In view of this, we should actively promote reproductive health services as a key part of the provision of basic public health services.

Notes

The 2001 survey was 4 years away from the 1997 survey, and the 2006 survey was 5 years away from the 2001 survey.

References

Chen, G., Pang, L., & Zheng, X. (2007). Induced abortion in China: the level, trend and determinants. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 5, 49–59. (in Chinese).

Chen, W. (2002). Determinants of induced abortion in China: a multilevel analysis. Market and Demographic Analysis, 8(5), 11–20. (in Chinese).

Guttmacher Institute. Induced Abortion Worldwide. Fact Sheet, March 2018. https://www.guttmacher.org. Accessed March 2020.

Kang, X., Luo, S., Weng, S., & Wang, S. (1991). Trend and determinants of induced abortion among married womenin China. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 2, 45–49. (in Chinese).

Kaufman, J., Zhang, E., & Xie, Z. (2006). Quality of care in China: Scaling up a pilot project into a national reform program. Studies in Family Planning, 37(1), 17–28.

Liu, S. (2005). Sex preference in childbearing for Chinese women. Population Research, 29(3), 2–10. (in Chinese).

National Family Planning Commission. (1998). Communiqué of the 1997 national population and reproductive health survey. Population and Family Planning, 5, 4–5. (in Chinese).

National Family Planning Commission. (2002). Communiqué of the 2001 national family planning and reproductive health survey. Population and Family Planning, 5, 46–47. (in Chinese).

National Population and Family Planning Commission. (2007). Communiqué of the 2006 national population and family planning survey. Population and Family Planning, 5, 21. (in Chinese).

Pan, G. (2004). Theses Collection of the 2001 National Family Planning/Reproductive Health Survey (pp. 64–73). Beijing: China Population Publishing House. (in Chinese).

Pang, L., Chen, G., Song, X., & Zheng, X. (2008). The choice of abortion and the choice of children’s sex: An exploration analysis. Population & Development, 14(3), 2–9. (in Chinese).

Qiao, X. (2002). Analysis of induced abortion in Chinese women. Population Research, 26(3), 16–25. (in Chinese).

Wu, S., & Qiu, H. (2010). Induced abortion in China: Problems and interventions. ActaAcademiaeMedicinaeSinicae, 32(5), 479–482. (in Chinese).

Zhang, E. (2000). China’s pilot program for quality of care in family planning services. Population and Family Planning, 1, 35–37. (in Chinese).

Zhuang, Y., Yang, S., Qi, J., Li, B., Zhao, X., & Wang, Z. (2019). China fertility survey 2017: design and implementation. China Population and Development Studies, 2(2), 259–271.

Zong, Z., Sun, X., Mao, J., Shu, X., & Hearst, N. (2020). Contraception and abortion among migrant women in Changzhou, China. The European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care. https://doi.org/10.1080/13625187.2020.1820979

Zou, Y., Liu, H., & Wang, H. (2018). Evolution of contraception mix in China, 2010–2016. Population Research, 42(5), 3–16. (in Chinese).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to this study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, Z., Yu, D. & Liu, H. Induced abortion among married women in China: a study based on the 1997–2017 China Fertility Surveys. China popul. dev. stud. 5, 83–99 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-021-00079-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-021-00079-5