Abstract

Against the backdrop of stagnation in hukou reform, a new theme in research on internal migration in China has emerged. Are reforms aimed at equalizing citizens’ rights effective in promoting the rights and position of rural migrants? This paper proposes that a dual transition is taking place in China, one that is affecting the market and another in the area of social policy. The paper examines two lines of reform measures intended to equalize rights: the marketization of employment and the development of inclusive social policy. This investigation on the reforms shows that rural migrants to cities have attained citizenship-based rights to employment and job-related social insurance. This paper also discusses the issue of local citizenship as a by-product of China’s reform and development. The paper’s findings imply that rural migrants are beneficiaries of China’s dual-transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Prior to 1978, a basic feature of policy in China was to impose severe restrictions on population migration from the countryside to cities. This resulted in a particular social structure and a special mode of rural–urban inequality. From the 1950s to the early 1960s, as the hukou system, labor employment system, urban food supply system and other relevant systems were established, a regime based on an artificial rural–urban divide was created. Beginning in those years and for years afterwards, peasants and their descendants were bound to rural areas and to agriculture. The status and rights of rural residents were fundamentally different from those of urban citizens, and urbanites enjoyed favorable opportunities and benefits guaranteed by the state, such as employment, income, welfare and other benefits (Cheng and Selden 1994). Therefore, in pre-reform China, in addition to the rural–urban inequality that commonly exists in all developing countries, China’s rural–urban divide included measures that made it next to impossible for rural farmers to move into urban society. Rural–urban disparities were thus fixed and reinforced by these policies, and peasants became a “low caste” class (Whyte 2010).

Since market-oriented reform began in the 1980s, restrictions on the movement of labor and population have loosened or been dismantled one by one, resulting in a tide of internal migration in the 1990s in which rural migrants to cities played a major role. Early research on migration was focused primarily on geographical patterns of rural-to-urban mobility, but studies soon turned their attention to the socio-economic significance of migration. Was it possible for rural residents, who had been disconnected from urban life in the past, to attain upward social mobility by working in cities and narrow the gap in rights and benefits separating them from urban citizens? A search for answers to this question led to the first wave of research on Chinese rural migrants in the 1990s. Until the early 2000s this research came to conclusions that were largely pessimistic. Many studies showed that rural migrants were not eligible for treatment equal to that urban citizens received in the areas of employment, social security and public services. An internationally comparative study found that Chinese rural migrants without urban hukou were as disadvantaged as foreign workers without citizenship in Germany and Japan (Solinger 1999a). A popular interpretation of the rural migrant issue was that the rural–urban divide that separated the country as a whole was reproduced on a smaller scale in China’s urban areas, with the result that rural migrants became “second class” citizens of the cities (Li 2004), and the urban domain became a new dual society (Chen 2005).

The past 10 years or more have witnessed an increase in the size of the migrant population, but the outcomes of reforms relating to rural migrants are still mixed. On the one hand, hukou reform has made little substantive progress. In 2001, the central government department in charge of hukou administration announced that “deep reforms” of the hukou system would be introduced as a part of urban labor market integration. This plan, however, was not carried out in practice (Wang 2010). In February 2011, the central government issued a document aimed at “actively and soundly” implementing hukou reform, but 1 year later a report by a department responsible for this new round of reform showed that almost all mayors surveyed “resist hukou reform” (Sun and Yao 2012). On July 30, 2014, the State Council promulgated a new guideline for hukou reform in which integrating rural and urban hukou status, introducing residence permission systems, and adjusting household registration policy were major components. The last one seemed particularly significant for rural migrants to obtain hukou in cities, but it limited on towns, small and medium cities, and control of hukou registration in big cities and metropolitan areas were to remain in place.Footnote 1 This means that the existing mechanism for hukou registration, which is crucial in determining the situation of rural migrants in cities, will to a large extent continue to function for some time.

At the same time, central government authorities have made other strategic reforms since 2003 that directly or indirectly affect rural migrants. First, in 2003 some new ideas for policies directed at rural migrants were presented, and by 2006, a package of new policies aimed at realizing “equal employment between cities and countryside” had been formulated.Footnote 2 Later, the equalization of rights for rural migrants was extended from policy to legislation. In 2007 the Labor Contract Law that stipulates equal labor rights for all employees including rural migrant workers was promulgated. In October 2010, the Social Insurance Law was passed and took effect the following year; the law gives citizenship-based rights to participate in social insurance schemes to rural migrants. In addition, the principle of providing the same basic public services for rural migrants and urban residents was established for governments at all levels. These new initiatives can be called rights equalization reforms and while not altering the hukou status of rural migrants, appear to be of some help to them.

These initiatives raise the question of whether it is possible to significantly promote the rights of rural migrants and improve their socio-economic position through such reforms to equalize rights, even in the context of slow progress on hukou reform. Emphasizing the importance and persistence of the hukou system, some scholars tend to deny that other reforms have an impact. For example, one study views recent reforms regarding the rights and welfare of rural migrants as “broad” hukou reform with unclear outcomes, and claims that the hukou is still central to determining the position and life chances of rural migrants (Chan and Buckingham 2008). In contrast, another study argues that inclusive reforms of social policy in the first decade of the new century considerably weakened institutional discrimination against rural migrants and hence reduced the importance of the hukou system (Zhang 2014).

The social policy reforms discussed in this study may serve as a starting point for a theoretical consideration of rights equalization reforms. China’s economic reforms since the 1980s have been commonly called “market-oriented reforms” or a “market transition”. Social policy reform, however, was not in evidence until the later 1990s. If social policy reform is really something new, it is necessary to rethink China’s overall transition process in order to develop a theoretical model to analyze and predict the consequences of the on-going rights’ equalizing reforms for rural migrants.

With a view to studying rural migrants in terms of rights equalization reforms, this paper is organized as follows. It starts with a couple of notes on China’s hukou system and the floating population. An account of China’s dual transition to a market economy and the use of social policy is then presented, and some of the relevant research is reviewed. On the basis of this conceptual framework, employment marketization and the development of inclusive social insurance are examined from the perspective of the evolution of rights, and their consequences for rural migrants are discussed. The issue of local citizenship as a by-product of the social policy transition is also carefully examined. The final section presents conclusions and discusses implications.

2 Notes on the hukou system and the floating population

The Chinese concept of floating population is closely associated with the hukou system. People belonging to the floating population are internal migrants who have changed their habitual residence but not registered their household in the location where they presently live. Here, China’s hukou system and floating population are introduced in order to provide the basis for discussions in internationally comparative studies in which Chinese rural migrants are included.

2.1 The Chinese hukou system

The hukou system literally refers to China’s household registration system. China has a long history of household registration administration that predates establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. After the foundation of Mao’s China, a preliminary household registration system was introduced in 1951. In this period, however, hukou administration was similar to household registration systems in other countries or regions of the world. Only urban residents were required to register their households and they were free to change residence. Later, hukou administration was gradually expanded and used to control migration, leading to the formation of a hukou system in 1958. This system involved far more than simple administrative procedures to register households and was consistent with the emerging centrally planned economy. From 1958 to 1959, the system actually collapsed during the Great Leap Forward, but in the 1960s it was re-imposed (Cheng and Selden 1994).

Under the fully developed hukou registration system, before 1978 every Chinese citizen was required to have a hukou registration in his or her hometown. In the 1950s people were categorized as rural population or urban population according to their occupations and given an agricultural hukou or a non-agricultural hukou. Hukou registration was managed by a “household registration agent” (usually a local police station) in the person’s hometown. In the 1960s and 1970s, anyone who moved out of the household registration locality for more than 3 days needed to complete a temporary household registration in the host locale. Changing residence from one hukou administration area to another required approval in advance. Migration from the countryside to a city was not only a change of residence, but also amounted to a change in the basic nature of one’s hukou—from an agricultural to a non-agricultural hukou. This form of migration was tightly controlled by the central government (Chan and Buchingham 2008).

In the research on hukou system, the relation between it and resource allocation is a point at issue. According to one study, the hukou system performs four functions—collecting and managing household and population information, serving as a basis for resource allocation, controlling internal migration, and monitoring “targeted people”, among which the latter three functions are “uniquely Chinese” (Wang 2010). The idea that hukou registration is used for determining resource allocation seems to be widely accepted, especially among scholars who emphasize the decisive power of the hukou system in social relations and social stratification. Another study conducted by a research team in Shanghai pointed to four social functions of the hukou system: verifying the status of citizens, maintaining public order, controlling the urban population, and providing government departments with information about residents, the last considered to be an auxiliary function (Research team of hukou 1989). This viewpoint suggests that the hukou system and other relevant systems together shape resource allocation mechanisms. Historical observations support this position. In the 1960s and 1970s, most important aspects of resource allocation were administrated by the relevant government departments, not the hukou administration department. For example, the urban food supply was managed by the Food Ministry and the Labor Ministry was mainly responsible for urban job assignments. The hukou system’s auxiliary function in resource allocation implies that if “the rules of the game” governing how a particular resource is allocated are changed in such a way that the rights of individuals to access that resource have nothing to do with their hukou status, then the hukou system will become irrelevant in this respect. This is the rationale for this paper exploring the impact of rights equalization reforms.

2.2 The floating population

During the reform era, population management and migration policies have changed a great deal. Despite the continued existence of the hukou system, residents can now go to other places to live and work without changing their hukou status. This enormous change has brought about the emergence and growth of the second type of population migration in China, non-hukou migration, in contrast to the traditional type of hukou migration which entailed administrative approval and the formal transfer of an individual’s hukou to a new locale. In addition to the concepts of hukou and non-hukou migration, other terms, such as permanent migration vs. temporary migration, planned migration vs. non-planned migration, have also been used in the literature on Chinese migration (Fan 2001). The concept of a floating population, which refers to non-hukou migrants, has become a common term in the media, and in policy design and academic research. In 2013, China’s floating population reached 236 million or about 17.4% of the country’s total population. The floating population is composed of two sub-populations based on their hukou status. Rural migrant workers and their family members with agricultural hukou status comprise the first group, and inter-city migrants with non-agricultural and non-local hukou, sometimes referred to as “outside citizens,” form the second group. Rural migrants, often called “peasant workers” (nongmingong) are the majority of the floating population.Footnote 3 A nationwide survey estimates that in 2011 over 85% of the floating population had rural hukou (National Population and Family Planning Commission Office for the Migrants 2012).

The emergence and growth of the floating population have changed the population structure of Chinese cities. In the pre-reform time the population of a Chinese city jurisdiction usually composed of urban population and rural population with local non-agricultural hukou and agricultural one respectively, and non-local hukou residents did not exist. Now the resident population of a city can be classified into four sub-populations, depending on whether an individual’s hukou is agricultural or non-agricultural and whether its locale is the city of residence or another place (see Table 1). In China, metropolitan areas and cities in the coastal areas usually have high proportions of floating population. For example, in Beijing, over one-third of the total resident population in 2010 did not hold a Beijing hukou (Zhang and Yang 2013).

Past research on the floating population focused on rural migrants, with a view to a theoretical analysis of systematic discrimination against rural hukou holders and a “two group” agenda that compared rural migrants with urban workers or citizens as a reference group. Recent studies have begun to develop a new approach in which the city-to-city floating population is the third group in the analysis (Zhang 2007; Yang 2013; Guo and Zhang 2012). Scholars have extended their concern about the floating population from a focus on the institutional advantages of urban hukou characteristic of the old-fashioned rural–urban divide to broader concerns and a focus on analyzing the implications of local hukou vs. non-local hukou status.

3 China’s market transition and the social policy transition

The histories of countries with market economies make clear that both free market mechanisms and state social policies have played essential roles in the development of market economies, but the advent of the latter lagged far behind the development of the former. In Western European countries, commodity exchange and domestic and foreign trade existed in the feudal period or even earlier, but markets were not a very important part of economic activities because of social constraints on labor and land. The new market economic system meant that factors of production such as labor, land, and money came under the regulation of the market. In England, capitalist industries emerged as early as the 18th century, but a nationwide labor market did not become the core of the market economy due to the guild system, the local system for relief of the poor and other institutions. Not until the early 19th century, when the old Poor Law and the Speenhamland systems were abolished was the market economy finally established (Polanyi 1944). In European countries, after the establishment of market economies, various forms of government regulation came into being to protect people against the impact of free market mechanisms. In the late 19th century, Bismarck developed a model for labor insurance in Germany, an early example of social policy reform in Western Europe. After World War II the development of social policy in Europe led to the age of the welfare state, which refers to the institutionalized responsibility of the government to provide comprehensive social security to citizens (Zhou 2005). In modern Western countries social policy has become a framework for reducing the negative impact of market mechanisms, securing the social rights of citizens, and maintaining social solidarity and development.

The reform of state socialism in the former Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and other socialist countries began with the introduction of some free market elements into their centrally planned regimes, followed by the gradual extension of these elements to build market systems. In China, a reform guideline in 1984 described its aim as building a “planned commodity economy.” However, in 1993, central government authorities announced that the ultimate objective of the reform was to establish a socialist market economy. In research on China’s market-oriented reforms, economists focus on increasing productivity, the efficiency of resource allocation and economic growth. For example, an overview study of China’s economic reforms from 1978 to 1995 identified three aspects—reform on the micro-management of institutions, on the mechanisms for resource allocation, and on the macro-policy environment, and judged that the Chinese economy had been transformed to one in which the market played a major role in resource allocation (Lin et al. 1996).

In contrast to economists, sociologists are generally less interested in economic efficiency than they are in the effect of reform on power structures and hence on income distribution and social stratification. For example, Nee (1996) argues that the market transition in state socialist countries, including “the growth of market institutions” such as labor markets, capital markets and business groups, weakens the redistributive power of the socialist state. Could social policy reform be a part of this marketization process? Sociological scholarship about state socialism and market transitions has so far given little consideration to this issue. Nevertheless, Nee (1989) provides a clue in his references to studies of the welfare state in western countries that show that redistribution reduces inequalities, while in state socialist economies the redistributive mechanism gives rise to greater social inequality. Nee suggests that economic and social reforms in socialist countries cannot be regarded as a pure process of market transition; rather, some part of the redistributive function of the state may be transferred to social policy.

In China’s transition from state socialism to a market-based system in the 1980s and 1990s, one of most striking phenomenon was the marketization of employment—the emergence and expansion of urban labor markets. In pre-reform China, full bureaucratic coordination of labor was exercised by means of urban public enterprises and rural people’s communes. Since the 1980s, non-public entities in urban areas such as individual businesses, domestic private firms, foreign companies, and other types of businesses developed and attracted employees who had departed from bureaucratic labor controls, including millions of rural migrants to cities. The growth of employment in this “new sector” accelerated in the 1990s, and with it there was an obvious reduction in the absolute and relative numbers of those employed in the public sector (state-owned enterprises, urban collective enterprises, and other public workplaces). As Fig. 1 shows, the proportion of people employed in the non-public sector grew from almost zero (0.2%) in 1978 to 5.5% by 1989, and then speeded up, reaching 54.2% by 1999. In the shrinking public sector, despite some trial internal reforms, the old labor institutions remained intact until the mid-1990s. After that, however, more and more state workers were laid-off or lost their jobs (Cai 2008, 40), and this marked the beginning of urban labor market integration, a new phrase of employment marketization.

The change of non-public sector’s percentage in total urban employment, 1978–1999. Original data from Cai (2008, p. 71). Data for some years are unavailable

The late 1990s were crucial for China’s transition, not only due to employment marketization, but also because these years marked the beginning of the enterprise labor security system that was a precursor of the transition to social policy. Before the advent of this system, a sign of the early marketization of workers in the new non-public sector was that they were almost totally exposed to labor market risks because there were no social security schemes for them. In this sense these Chinese non-public sector workers were in a very similar situation to free wage workers in the period of the free market in Europe prior to the rise of social policy. In contrast, state workers during this period were still covered by social security schemes offering medical care, pension and other benefits. This labor security system established during the years of the centrally planned economy in China appeared similar to employment-related social insurance schemes in modern market economies, but it was organized differently. This was a system based on the rural–urban hukou divide and the employment status of urban workers. Rural laborers with agricultural hukou had no access to the system, and even among urban hukou holders, only those formally employed by public sector state-owned or managed enterprises and organizations were fully eligible for all benefits (Walder 1986). This Chinese system was not built on the concept of universal citizenship and market economy mechanisms.

In 1997, the reform of this system began with the establishment of a pension insurance scheme targeting all workers contracting with any enterprise, regardless of the ownership form of the enterprise. A medical care insurance scheme with the same broad-based coverage followed in 1998. An unemployment insurance scheme was introduced in 1999. These initiatives were not simply modifications of existing arrangements or a change from one social insurance model to another; rather, they were key steps in a fundamental transformation from status-based labor security and welfare schemes to citizenship-based social insurance—an important component of social policy (Zhang 2014). Therefore, in the 1980s and the early 1990s there was a period of market transition without the establishment of social policy, but beginning in the late 1990s China entered into a new era of a dual-transition to a market economy and to the use of social policy.Footnote 4

Since the early 2000s, marketization of employment has deepened and social policy reform has also made considerable progress. The proportion of people employed in the state sector had fallen to 20.3% by 2011, meaning that about four fifths of urban laborers were employed in the non-public or new sector by this time. As employment in the public sector shrank in the 2000s, participation rates in most employment-related social insurance schemes saw a clear increase. This growth in participation signifies that the new social insurance schemes benefit more and more people outside of the public sector. The increasingly “social” nature of social insurance is illustrated in Fig. 2, which shows the structural change in participation in basic pension schemes for urban workers in the first decade of the new century in terms of the proportion of workers from each sector. These rough indicators allow for intuitive estimates of the current state of employment marketization and the social policy transition. However, to better understand these two processes and highlight their consequences for rural migrants, it is necessary to introduce citizenship rights into the theoretical discussion and examine these rights empirically.

Proportions of participants in urban workers’ basic pension scheme by sector, 1999–2010. Original data from Ministry of Human Resources and Social Protection (2011, 963, 999)

4 Research on the socio-economic transition and the evolution of citizenship

Both a market economy and social policy are associated with the development of citizenship rights. The sociologist Marshall (1950) conducted pioneering research on the relationship between social change and the evolution of citizenship. Based on his analysis of British history, Marshall defines citizenship as a status that secures equal rights and duties and is commonly possessed by all members of a society. He divides citizenship rights into civil rights related to personal, economic and other freedoms; political rights related to democracy; and social rights related to welfare and security. He argues that, in England, these citizenship rights were developed during the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. During the early stage, civil rights were the core of citizenship and served as a basis of the free market economy. With the development of the welfare state, social rights became crucial. According to Marshall (1972), the market value of an individual cannot be used as a criterion to determine welfare rights. Rather, the first function of the welfare state is to control and adjust market mechanisms in order to bring about results that the market is unable to generate.

Rather than exploring citizenship rights, sociological research on market transitions in socialist states began by examining the redistributive mechanisms of these states. In a state redistributive economy, Szelenyi (1978) argues that any surplus is directly collected and redistributed by the state, and that this process creates and structures social inequalities favoring those with redistributive power. Nee (1989) presents a theory of market transition, arguing that in the process of transition from state redistribution to market mechanisms, market actors gain power over redistributors and alter the social stratification order. Market transition theory has triggered heated debates among sociologists interested in market-oriented reforms in state socialist countries.Footnote 5 Research in this area focuses on changing modes of resource allocation and income distribution and, at the same time, findings suggest that marketization affects the rights of individuals. According to Szelenyi (1978), the core of the state socialist economy is non-market trade in labor, which means that citizens are deprived of the freedom to work as a basic type of civil right. Therefore, in the transition to market mechanisms based on the labor market, redefining labor rights should be of primary importance. Nevertheless, in the literature on market transitions, little attention has been paid to Chinese rural migrants, despite the fact that they are a major social group affected by the restructuring of rights.

In contrast to the general prediction of market transition theory that marketization benefits the formerly powerless and underprivileged, some studies of Chinese rural migrants from a citizenship perspective have sketched a different picture. How do emerging markets affect rural migrants? Solinger (1999b) raises this question and concludes that both the state and markets are preventing rural migrants from acquiring normal urban citizenship symbolized by an urban hukou. Consequently, rural migrants become second-class citizens in their host cities. Thus, the outcome of marketization “must be understood in conjunction with institutional legacies left from the former socialist system” (p. 9). Another study uses the concept of differential citizenship to address the second-class status of rural migrants, but attributes this primarily to factors such as the demand of local governments for cheap labor under globalization (Wu 2010). These studies not only question market transition theory, but also challenge Marshall’s view that the market economy and citizenship rights are positively correlated.

An approach based on urban citizenship or differential citizenship nevertheless needs close scrutiny. The underlying assumption that “urban citizenship” in China serves as a standard model is not very reliable (Wang 2009). In pre-reform China the entitlements of urban residents were not really citizenship rights (Zhang 2014). More importantly, Solinger’s research (1999a, b) relies mainly upon observations made in the first half of the 1990s, when it might have been too early to draw convincing conclusions about the impact of China’s reform on individuals in general and on rural migrants in particular. During this period, marketization was in its early stages. As discussed above, before the late 1990s, the development of the urban labor market was limited to the new non-state sector, while the state sector was still dominated by the old socialist employment model. During this period of partial reform, the urban labor market was unable to work normally or fairly. Meanwhile social policy reforms had not yet started. So to improve our knowledge about the equalization of rights for Chinese rural migrants, it is crucial to conduct an empirical examination of the dual-transition after 2000, especially employment marketization and the development of inclusive social security reforms.

5 Employment marketization and incremental labor rights for rural migrants

China’s market-oriented reform has been multifaceted, and within it, employment marketization has been, for the most part, directly related to the rights and status of individuals. In the pre-reform period, neither urban nor rural laborers could work in jobs of their choice, but their patterns of employment were nonetheless different. The relatively better jobs available in cities were assigned only to urban laborers, whereas rural labors were tied to life-time collective farming with low, unstable incomes. Employment marketization replaced the bureaucratic coordination of labor with labor market mechanisms which generally bestowed free and equal labor rights on individuals, but its effects on urban and rural laborers obviously varied. For workers with urban hukou, employment reform in the direction of equal rights for workers meant they lost the exclusive entitlements to permanent employment and vested benefits they had enjoyed in the past. For rural migrants, however, this was purely a process of expanding rights, because at the beginning they had no rights to lose. Employment marketization can be broken down into three stages, 1978–1992, 1993–2002, and after 2002. During each of these stages the labor rights of rural migrants increased incrementally step by step.

5.1 1978–1992: rural reform and employment of migrants in cities

China’s post 1978 reforms were first introduced in the countryside. In the early 1980s, the household responsibility system was fully implemented, and rural laborers were liberated from collective farming in People’s Communes. This was accomplished by restoring private rights to labor (Cheung 1989). Restrictions prohibiting rural residents from moving out remained in place initially, but by the mid-1980s peasants were permitted to work and live temporarily in cities (Solinger 1999b). Thanks to these changes and the emergence of the new urban employment sector, in the 1980s rural migrants began to move to cities. A survey of Shanghai conducted in August 1984 showed that there were numerous migrants on the outskirts of the metropolis, the majority of whom were peasants from other provinces engaged in trading agricultural and sideline products (Zheng et al. 1985). By the mid-1980s, the size of the floating population was increasing rapidly due to changing economic relationships and the flow of commodities across regions and between rural and urban areas. A considerable proportion of migrants were people from the countryside who migrated to the cities for work (Zhang 1986).

In addition to rural migrants working in the new non-state sector, some rural migrants also worked in the state sector without formal employment status. In 1986, state-owned enterprises began to introduce a contract system for newly recruited workers.Footnote 6 Against this background, three forms of employment came into existence within state-owned enterprises: permanent or fixed workers who were bureaucratically assigned jobs before the reforms began; urban contract workers; and peasant contract workers. The last referred to rural laborers with agricultural hukou who were contracted by enterprises.Footnote 7 The entitlements and treatment of the three types of workers were different, with a hierarchy descending from permanent workers to peasant contract workers. In summary, rural migrants to cities worked in the new sector or got jobs with informal employment status in the state sector, but it was more difficult for them to get jobs in the state sector than in the new sector.

5.2 1993–2002: coexistence of two types of labor relations

In 1993, as the establishment of a socialist market economy became the objective of economic reforms, the state sector employment system also became a target for reform. In July 1994, the Labor Law was issued and took effect in January 1995. This law defined general contract labor relations for all types of Chinese enterprises, and in doing so, did away with the system of fixed employment in state-owned enterprises and the rural–urban segmentation of labor. In accordance with this law, from the late 1990s, lay-offs were common in the state sector and re-employment programs were implemented; increasingly workers were driven into urban labor markets.

In this period, however, the Labor Law was not applied to rural migrants. In November 1994, just 4 months after the Labor Law was promulgated, the Ministry of Labor issued a bylaw entitled the Temporary Regulation on Rural Migrants’ Employment across Provinces.Footnote 8 This regulation imposed several restrictions on rural migrants working in cities, including: (1) priority given to local workers in employment policy, (2) administrative approval for industries and types of work which were open to rural migrants, and (3) approval procedures for migrants in their hometowns. In accordance with this regulation, many provinces and cities issued overtly discriminatory local regulations or policies with respect to the employment of migrants (Li 2007). These regulations and policies treated rural migrants as aliens, which was contradictory to the universal principle embodied in the Labor Law.Footnote 9 In this situation, two sets of labor relations developed in cities. One was defined by the Labor Law and emphasized labor protection and covered local laborers involved in contract employment. The other was for rural migrants and was set according to local policies aimed at controlling and regulating this labor force.

During this time, the efforts of central and local government authorities were focused on coping with the complex problems of restructuring state-owned enterprises (SOEs), among which the most challenging problem was pressure to find employment for the vast numbers of laid-off workers. Therefore, although equal employment rights were embodied in the Labor Law, this principle could not be applied to rural migrants immediately. As a result, because the employment status of rural migrants remained unprotected, they were still subordinate to local workers. Nevertheless, despite this new form of institutional discrimination, the relative position of rural migrants in urban labor markets had nonetheless improved somewhat because state workers increasingly had to compete with them in the emerging urban labor markets.

5.3 After 2002: from new policies for rural migrants to the Labor Contract Law

Equal employment for urban and rural laborers became a principle in 2003. The central government announced that rural migrants and urban citizens should be treated equally, and all restrictions on the employment of rural migrants should be eliminated. In 2005, the temporary regulation issued by the Ministry of Labor in 1994 that overtly discriminated against rural migrants was revoked,Footnote 10 and related local regulations and policies were eliminated accordingly. In 2006, new policies for rural migrants were formulated systematically in Several Opinions of the State Council on Solving the Problems of Rural Migrant Workers, a document that stressed the need to pay rural migrant workers fair wages and ensure they had equal labor rights and relations with other workers.Footnote 11

After the implementation of the new policies, the Labor Contract Law came into force in January 2008. This was a milestone in the employment marketization process. Compared with relevant provisions of the 1994 Labor Law, the labor relations defined in the Labor Contract Law were not essentially different. However, the legislative environment in the late 2000s was very different. The emphasis of the reform of labor institutions had shifted from SOEs to labor market integration. Central and local government regulations and policies that discriminated against rural migrant workers had already been revoked and the legal framework for labor relations embodied in the Labor Contract Law was therefore generally applicable to all workers, including rural migrants contracted with enterprises. The enforcement of this law has obviously led to an increase in the proportion of rural migrant workers employed with labor contracts. A sample survey in the Pearl River Delta, Guangdong province, an area with a large concentration of rural migrants, shows that in 2009 62.36% of rural migrant workers had written labor contracts with their employers, an increase of nearly 20% over 2006 (Li and Freeman 2014). Because migrants have high mobility and for a number of other reasons, the proportion with employment contracts is still low compared with local workers. Nevertheless, most importantly, under the Labor Contract Law, the legal rules defining employment rights and relationships have been unified and institutionalized discrimination against rural migrants with agricultural and non-local hukou has become a thing of the past.

Employment marketization is not yet complete. On the one hand, in public and semi-public industries, hukou status can still sometimes be used to create unequal employment rights. For example, in some cities, university graduates with non-local hukou may find it difficult to get jobs in public agencies and SOEs because local policies and ad hoc decisions favor “native” graduates. On the other hand, some new forms of labor market segmentation have emerged. For instance, there is employment inequality in an enterprise between workers under direct contract relation with it and labors from labor dispatching companies. In the case of public sector employment rural migrant labors were almost irrelevant because this sector employs few of them. In the case of contract/dispatching inequality the dispatching laborers include both rural migrants and other labors. In sum, rural migrants are no longer the only unprivileged group in the urban labor market. Although further employment marketization may affect rural migrants in various ways, the magnitude of the impact in the future will be much less than that in the past.

6 An inclusive social security network and rural migrants’ rights to coverage

China’s social policy transition since the late 1990s has given rise to an inclusive social security network. Prior to the development of this network, there was only the urban labor security system that covered workers of employees and staff in public institutions. Today, the new network is composed of social insurance, social assistance and social welfare and provides broad coverage for rural and urban laborers and residents. The inclusive nature of social security reform is reflected in efforts aimed at setting up universal work-related social insurance and in the fact that migrant workers are legally incorporated into the new system.

6.1 The late 1990s: initiating social insurance reform

General ideas for social insurance reform began to form in the early 1990s. In the 1993 reform guidelines formulated by the central government for the socialist market economy, some basic points concerning social insurance reform were addressed. For example, employers and employees would share responsibility for funding pensions and health-care. In 1995, a requirement for labor insurance for all contractual workers was first written into the Labor Law. There was a push at this time towards overall reform in the direction of social insurance.

Substantial reform measures in the direction of social policy started in 1997. In that year, the State Council issued a decision on establishing a uniform social pension scheme for workers in urban areas.Footnote 12 In 1998 the central government decided to set up a basic medical-care insurance scheme for urban workers.Footnote 13 In 1999 The Regulations for Unemployment Insurance were issued, providing urban workers with protection in the event of unemployment. According to these new institutional rules, urban employees, no matter which types of enterprises they worked for or the status of their hukou, should be covered by these three programs. This meant that status-based eligibility under the old labor security regime had been abandoned. The new rights to be covered by and participate in these work-related insurance schemes were social rights. They were based on the concept of universal citizenship, regardless of hukou status or other status.

However, initially, reforms in the direction of social insurance were not implemented universally in practice. From 1997 to the early 2000s, the new social insurance schemes were mainly implemented in public sector enterprises (Fig. 2). Due to the difficulties encountered restructuring SOEs, financial constraints and other factors, early reform efforts concentrated on state workers, and employees of other types of enterprises and other workers were not immediately covered (Xin 2008). Two groups that were initially omitted were residents of cities who were employed outside the public sector and almost all rural migrants to cities. Rural migrant workers with agricultural hukou were more difficult than resident urban worker to cover because, as discussed in the preceding section, they were not regarded as normal urban workers when the system was characterized by dual-labor market relationships. Rural migrants without equal labor rights could not get legitimate access to the newly developed social insurance programs, which policies at the time made available only to those classified as urban workers.

6.2 Inclusive work-related injury insurance implemented in 2004: a breakthrough for rural migrants’ participation in social insurance

Five years after the first round of social insurance reform, in January 2014, the Regulation on Work-Related Injury Insurance was issued by the State Council. Like other social insurance regulations, it applied to “all urban workers,” but according to common understandings from the 1990s, the scope of “urban workers” did not include rural migrant workers. However, in June 2004, just half a year later, the Ministry of Labor and Social Security issued an official Notice, which indicated that rural migrant workers had basic rights to participate in work-related injury insurance.Footnote 14 This was the first time the government stated specifically that rural migrants had equal rights to insurance; previously there were no administrative interpretations relating to the participation of rural migrants in the three social insurance schemes introduced in the late 1990s. With the enforcement of the 2004 regulation to provide work-related injury insurance, rural migrant workers began to be regarded as a part of the urban labor force. However, at that time it was still unclear whether this equal-treatment principle could be extended to other social insurance schemes.

6.3 The 2010 Social Insurance Law: defining equal rights in social insurance

New policies for rural migrants, under the banner “equal employment for urban and rural laborers”, were developed from 2003 to 2006. These policies were not limited to advocating equal labor rights; equal treatment with respect to social security coverage and public services accessibility were also objectives of these policies. The provision that rural migrant workers be treated equally with respect to work-related injury insurance can be partly attributed to the implementation of these new policies. Before, during and shortly after 2006, there was an ongoing debate among researchers and policy makers at the national level over whether to treat rural migrant workers as a special group in urban work-related social insurance programs. At the local level there had been a number of local pilot social insurance programs for rural migrants. During this period of implementing new policies for rural migrants, their participation in social insurance was also under consideration, but it was a long way from being integrated into policy nationwide.

In 2010, both the debate about the participation of rural migrants in social insurance programs and local trials came to an end, because the Social Insurance Law was enacted that year and came into force in July 2011. Article 1 of this law states that its purpose is “to regulate social insurance relationships and protect the legal rights of citizens to participate in social insurance and enjoy related benefits”. A central purpose of this law is to define citizenship rights for all types of work-related social insurance—basic pension, basic health-care, unemployment, work-related injury, and maternity. Of particular importance is Article 95, which stipulates that “rural residents working in cities participate in social insurance in accordance with this law”. If rights to participate in social insurance are a matter of citizenship, then all members of society naturally possess such rights, and hence special interpretations about the status of particular groups should become redundant. Nevertheless, given the earlier tacit understanding that rural migrants did not belong to the category of urban workers, it was necessary to state clearly, as Article 95 does, that rural migrant workers have the same right to social insurance as other urban workers. The fact that Article 95 is essential to the law tells us how difficult it is to overcome the legacy of the rural–urban divide, both in terms of reforming the formal rules and altering the informal customs that discriminate against rural hukou holders.

As a landmark in inclusive social insurance reform, the Social Insurance Law formulates an institutional framework for work-related social insurance. The development of this reform involved a process of eliminating the role of status. In the late 1990s, reform initiatives opened some social insurance schemes to all urban workers, meaning all employees with urban hukou. After 2000, rural migrant workers with rural hukou were gradually included in these reforms. By clearly defining citizenship-based rights, the Social Insurance Law became hukou-neutral and allowed all individual laborers to participate in and enjoy all kinds of work-related social insurance. Enactment of this law has especially benefited rural migrants who were ignored in the early rounds of social insurance reform, but have now finally obtained full access. Reforms to make other aspects of social security inclusive are underway, and some of these reforms may also be relevant to rural migrants. However, establishing equal rights for access to work-related social insurance has generated direct, specific, and powerful consequences for rural migrant workers that future reforms may not be able to match.

7 The impact of rights’ equalizing on rural migrants: preliminary evidence

Employment marketization and social insurance reforms that offer inclusive coverage are evidence of the evolution of citizenship generally, and in particular have contributed to the equalizing of rights for rural migrant workers. Thanks to these rights’ equalizing processes, rural migrants have attained universal legal rights with respect to urban employment and related social insurance. They received some marginal labor rights in cities in the 1980s, before social insurance reform had taken place. In the late 1990s, social insurance reform was initiated, but rural migrants were actually excluded. After 2000, rights equalization for rural migrants was extended from urban employment to work-related social insurance. When legislative reforms of the employment system were pushed forward in the late 2000s, guaranteeing equal rights for rural migrants was a key part of the process.

Are these rights’ equalizing reforms improving the socio-economic situation of rural migrants with regard to urban employment and social insurance? The point at issue is the extent to which such legally defined rights can actually be realized. There are some negative factors that must be considered. Without radical hukou reform, the hukou status of rural migrants may still work informally, and even formally in some cases, to affect the enforcement of the Labor Contract Law and the Social Insurance Law. Moreover, some characteristics of rural migrants, such as generally low levels of education and low incomes, may serve as barriers to social inclusion regardless of the law. Both of these concerns suggest that it is difficult for rural migrants to fully enjoy equal rights. At the same time, it is nonetheless reasonable to argue that the effects of institutional change in urban employment and social insurance for rural migrants are substantive. Rural migrants are not a social group with ascribed status based on their being an ethnic minority, a race, a caste, or a group with particular religious beliefs. Their disadvantages in the past resulted basically from man-made institutional exclusions. Therefore, the evolution of rights and equalizing reforms which greatly limit the importance of hukou and move toward full citizenship rights should be powerful and should have an observable impact in terms of narrowing the inequality gap between rural migrants and the urban residents of the cities where the migrants live.

Recent empirical research has already provided some preliminary evidence to support this hopeful outlook for the rights of rural migrants. Some studies have observed that there is less wage discrimination against rural migrant workers, or that unexplained wage differentials between rural migrants and local laborers have diminished. Income inequality between these two groups of workers is related to differences in welfare income, not differences in wage income (Xie 2007; Guo and Zhang 2012). In recent years, the wage growth for of rural migrants has exceeded that of local workers (Li 2013). An econometric study shows that the contribution of hukou discrimination to wage differentials fell from 35.18% in 2002 to 25.08% in 2007 (Pang and Chen 2013).

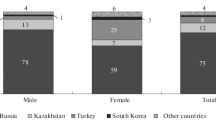

Furthermore, participation of rural migrants in work-related insurance has increased rapidly, and this evidently signifies that rural migrants are securing their social rights to this insurance. Table 2 shows the rates of rural workers in non-agricultural industries (nongmingong) participating in the four social insurance schemes. Some surveys have provided higher estimates of their participation rates.Footnote 15 In any event, this table illustrates the general movement towards higher participation rates for rural migrants.

In addition to the position of rural migrants with respect to urban employment and social insurance, there is the broader question of their class status. The differential citizenship argument holds that due to the persistence of the rural–urban divide, a migrant working class is forming (Wu 2010, p. 61). According to this view, this working class should be subordinate to workers with local hukou because rural migrants lack essential rights to urban employment and related social insurance. In contrast, there is an argument claiming that a powerful equalization of rights has taken place, an equalization of rights implying that rural migrants are being integrated into the urban labor force and that a uniform working class is emerging in Chinese urban society. The latter argument is supported by a recent study that examines the bargaining and protesting activities of urban workers and suggests that the goals of local workers and rural migrants are converging (Li and Luo 2014).

8 Local citizenship and non-hukou migrants in dual-transition

Although the equalization of rights to access work-related social insurance has achieved a lot, the social rights of rural migrants in cities are still incomplete. Rural migrants are legally ineligible for residence-based social security, such as old-age insurance systems for residents that are restricted to local hukou holders. They may also find it difficult to get access to some public services; for instance, to education in public schools for their children. Such problems are often cited by some scholars as direct evidence of the persistence of the rural–urban divide. However, some changes have already taken place. In the 1990s, rural migrants were denied equal rights to employment due to their agricultural hukou status; now both rural migrants and floating migrants without local hukou are excluded from residence-based social security. In the past, within cities or administrative regions a rural–urban hukou divide existed, and residents of cities with rural hukou were unable to be formally employed in nearby urban areas. Since the beginning of the new century, however, this hukou divide has weakened rapidly due to rural–urban integration. In February 2014, the old-age insurance system for urban residents and that for rural residents were unified; 5 months later the central government announced the end of rural and urban classifications in the hukou system. Nowadays, it is the fact rural migrants hold hukou from a locale other than the place where they live that is basically responsible for their exclusion. Another important change is that rural migrants are no longer alone in their underprivileged position, for the situation of inter-city migrants is similar.

To describe and interpret this new pattern of discrimination or exclusion in the allocation of social rights, I introduce the concept of local citizenship.Footnote 16 This concept can be considered in reference to that of urban citizenship proposed by Solinger (1999b). From this perspective, in the 1990s urban citizenship, as represented by the urban hukou, functioned in Chinese cities as citizenship does in a Western society to determine “a person’s entire life chances” (p. 4). The dual-transition in the 2000s has caused this earlier type of urban citizenship to diminish in importance and has led to the development of universal citizenship rights in employment and related social insurance. However, while hukou-based urban citizenship available only to a limited group of people has, to a large extent, been eliminated by the dual transition, residence-based social security and lack of access to certain public goods have emerged as new barriers to rural migrants enjoying full citizenship rights in the cities where they live. In contrast to urban citizenship, local citizenship is defined by local hukou status in a city. That is, local citizenship is not concerned with distinctions between urban and rural residents; instead, it allocates residence-based social rights only to people who are residents anywhere within the city’s jurisdiction (the urban core area or rural counties) and excludes “foreigners”—citizens from other places in China. Just as the idea of urban citizenship can be regarded as a rights-based conceptualization of the rural–urban divide, the model of local citizenship also encapsulates a rights perspective, but it is used to explain hukou-based “native-migrant” inequality that is an outcome of regional segmentation.Footnote 17 Local citizenship exists in almost all Chinese cities, although its existence is more obvious in prosperous cities with large non-local populations.Footnote 18

In fact, some social rights are fully and legally (de jure) tied to local citizenship, but others are not. Of the local citizenship rights with legal standing, the most obvious and common is access to the subsistence allowance (dibao). According to the Regulations on Subsistence Allowance for Urban Residents issued in September 1999, urban households should apply for the subsistence allowance in their hukou registration localities. Clearly, non-locals do not qualify for this kind of income support. In most provinces, eligibility for the entrance examination to universities and colleges is also limited to students from households with local hukou. This eligibility requirement has been the subject of heated debate for many years (Liu 2011). Recently, guided by the central government, local governments have begun to develop various low-income housing programs, but in most cases such programs are only open to local residents.Footnote 19 The ability to be eligible to take university exams or have access to low-income housing is linked to local hukou status by formal regulations and thus these rights are examples of de jure local citizenship. Some other social rights are legally open to all without a local hukou requirement, but the formulation of relevant policies and ad hoc decisions potentially favor holders of local hukou. For example, it is difficult for migrants with informal jobs to participate in work-related social insurance schemes, despite the fact that, according to the Social Insurance Law, laborers in the informal sector should be covered. Another example is that in some cities it is still problematic for migrants to enroll their children in public schools, even though equal access to schools has been the policy of the central government for years. Limited access to these social rights are examples of de facto local citizenship. Although laws and regulations guarantee migrants access to social insurance programs and public schools, in practice it is difficult for migrants to realize these rights.

Table 3 compares the characteristics of local citizenship rights with those of earlier urban citizenship rights.Footnote 20 The difference in how they are based on hukou status is straightforward. The central government created the system of urban citizenship rights based on a rural–urban divide that existed before 1978 and was maintained until the 1990s. This is why this system remained uniform across China. In contrast, local governments have played a major role in the development of local citizenship, and depending on the pressure exerted by the floating populations in different cities, the arrangements defining local citizenship vary from strong to moderate to slight. In the past, the system of urban citizenship rights brought about rural–urban inequality and was basically responsible for the formation of a low status peasant class. The new model of local citizenship rights has resulted in inequality between locals and migrants, but this inequality is not so pronounced as to create a new migrant class in urban China. This is because the scope and strength of “native-migrant” inequalities are much less than those of rural–urban inequalities were. Moreover, the non-hukou status of migrants is not fixed for life because migrants are able to resume “native” status if they return to the place of their hukou origin.

The emergence of hukou-based local citizenship as a deviation from universal citizenship is not totally incidental. The pathway of the social policy transition has been largely shaped by the types of market-oriented reform introduced and the patterns of economic growth. China’s economic reform has been described as a decentralized approach underpinned by financial federalism (Qian et al. 1999; Jin et al. 2005). Decentralized reform has contributed greatly to China’s dramatic economic growth by providing incentives to local governments and encouraging competition between them. This kind of reform has, nevertheless, been costly, because increasing income inequality, regional market segmentation, and the inadequate provision of public goods at the local level are attributable to these reforms (Wang et al. 2007). Driven by decentralized reform, local governments are inclined to welcome migration, but they generally regard the people who migrate as guest workers, and do not extend to them rights and treatment equal to what local citizens enjoy. In a reform atmosphere that encourages local experiments and initiatives, when it comes to regulating access to social security provisions, the central government’s concern with rights and interests of migrants has to somehow find a way to compromise with the interests of relatively autonomous local governments. A more serious problem is the fact that decentralized reform has caused uneven development across regions. This is reflected by much faster economic growth and greater pressure from migration to big cities and coastal areas. Uneven development has reinforced local exclusion and makes it difficult for the central government to design and manage integrative and inclusive social security programs. Since local citizenship is a by-product of China’s reform and development strategy, guaranteeing universal citizenship rights to all Chinese will require a long term effort.

Consequently, the existence of a floating population that does not have full membership in urban society will last for a period of time. However, rights equalization reforms are continuing and being extended in scope, so the situation of this floating population will improve gradually. Central government authorities have pledged a steady “equalization of basic public services” for the floating population in cities. At the regional and city level, increasing labor shortages are expected to induce local governments to create adaptive policies and administrative measures in order to attract migrants. As a result, the floating population will hopefully gain more equal social rights and equal access to local public goods in the future. In parallel with this process, the significance of the hukou system will diminish. Rural migrants and inter-city floating migrants do not seem concerned with radical hukou reform, but they do expect gradual but real progress in the area of rights’ equalizing reforms.

9 Conclusions and implications

Whereas in Western states the policy debate concerning international immigration has something to do with citizenship, in China policy discussions and scholarly research on internal migration are always related to the hukou system. This system is considered by some scholars to be decisive in determining the level of discrimination against rural migrants. However, regarding this system as determinative in terms of rights may lead to overestimating its power and ignoring other influencing factors. Just as citizenship in Western countries serves as a device for excluding immigrants from certain rights, so the hukou system in China is a mechanism for allocating rights. If institutional rules about rights are no longer related to hukou status, but are redefined on the basis of universal citizenship, the hukou’s function in allocating rights will cease. This paper has examined rights equalization reforms for rural migrants and assessed their effects from this perspective.

By constructing a new conceptual model of transitional China, one that describes a dual-transition to a market economy and to social policy, and then systematically investigating processes of employment marketization and social security inclusion, this study has found that rights equalization reforms have been quite successful with regard to urban employment and related social insurance. In the 1990s new institutional rules about labor rights and work-related social insurance rights were initiated, but these rights were not bestowed on rural migrants immediately. Not until the early 2000s did policy initiatives to equalize rights for rural migrants begin. By the end of the 2000s, this rights’ equalizing approach specific to rural migrants was finally integrated into the development of citizenship rights and reflected in legislative reforms in the areas of labor relations and social insurance.

The equalization of rights for rural migrants is embedded in the building of citizenship rights more generally. Recent advances of citizenship rights have affected China’s entire working population, but rural migrants who began with no protections whatsoever have been benefited relatively more than other groups. In the fields of labor and work-related social insurance there remains much to be done to improve the enforcement of legally defined rights. What is important, however, is that rural migrants, inter-city floating migrants and local workers are now able to enjoy equally gains from the evolution of citizenship and endure its shortcomings equally as well. Through the use of rights equalization reforms, China has succeeded in preventing the formation of an isolated and low status class of workers composed of rural migrants to cities.

This study also shows that beyond the domain of employment, equalization of the rights of rural migrants is just beginning. Rural migrants in cities still lack certain basic social rights, including most residence-based rights and access to some basic public services. Today, notions of local citizenship, not an earlier notion of urban citizenship, are the driving mechanism of discrimination migrant populations. However, the power to discriminate has been considerably reduced because at least partial citizenship rights have been established. The central task of rights equalization reforms in the future is to fight against local citizenship arrangements.

The above findings call for a rethinking of the situation of Chinese rural migrants. In the past, the term “peasant workers” appeared in the literature to signify the continuity of the rural–urban divide. Now it is reasonable to argue that rural migrants are being included in urban society, although progress towards inclusion has not moved along a linear path. While market transition theory focuses on elites—entrepreneurs taking the place of “redistributors” as marketization proceeds, this paper suggests that rural migrants are agents in the dual-transition to a market economy and social policy regime. Employment marketization and social insurance inclusion, which have a special impact on rural migrants, have helped China’s dual-transition get off to a good start.

Notes

The full name of the document is “Opinions about Further Implementing the Reform on the Hukou System”. (http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-07/30/content_8944.htm).

The State Council issued “Several Opinions of the State Council on Solving the Problems of Rural Migrant Workers” on Jan. 31, 2006. (http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2008-03/28/content_6668.htm).

One official statistic related to rural migrants is “out-migrant peasant workers” (waichu nongmingong). In 2013, the total of “peasant workers”(nongmingong), referring to those with agricultural hukou but not working in agricultue was 268.94 million, among which the amount of “out-migrant peasant workers” was 166.10 million (Household Survey Office SSB 2013). The definition of out-migrant peasant workers, however, is not exactly consistent with that of floating population (Zhang and Yang 2013).

Wang (2007) has similar ideas. He argues that, from 1978 to the mid-1990s in China, there was no social policy; he believes that during this period of time there was only “economic policy” and does not use the notion of market transition or similar concepts.

About the debates, please see: American Journal of Sociology, vol. 101, no. 4 (Jan. 1996), which included a special section about market transition; Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 19 (2002) was a special issue named “The Future of Market Transition”.

In July 1986, the State Council issued Temporary Regulation on Implementing the Labor Contract System in State Enterprises. (http://www.110.com/fagui/law_1730.html).

In July 1991 the State Council issued Regulations on Recruiting Peasant Contract Workers for State-owned Enterprises. (http://www.110.com/fagui/law_2774.html).

For this regulation, see http://china.findlaw.cn/fagui/p_1/227046.html.

The second clause of 1994 Labor Law stated that this law was applicable for enterprises and individual businesses within PRC’s border and laborers who had contractual relations with these entities.

In Feb. 2005 the Labor and Social Security Ministry issued a notice to abolish this regulation.

For this document, see http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2006/content_244909.htm.

The title of the document is “Decision about Establishing a Uniform Basic Pension Insurance System for Urban Workers”.

The title of the document is “Decision about Establishing a Basic Medical Insurance System for Urban Workers”.

The full title of the document is “Notice concerning issues about rural migrant workers’ participation in work-related injury insurance”.

For instance, a nationwide survey reported that participation rates of rural migrant workers in basic pension insurance, basic medical care insurance, unemployment insurance, and work-related injury insurance in 2011 were 19.7, 23.3, 11.2, and 23.4%, respectively (Department of Services and Administration for Floating Population, NPFPC2012, p. 89). Another example is a five-city survey that estimates that in 2010 rural migrants’ participation rates in basic pension and basic medical care were 24.95 and 31.95%, respectively (Gao 2014).

As has been mentioned, rights’ discrimination may also happen in urban employment. Such events, however, are sporadic and have little impact on rural migrants. So investigation here concentrates on systematic social rights’ discrimination.

Zhang (2007) has examined the decline of the rural–urban divide and the rise of regional segmentation.

A field study on welfare reform in a “new factory town” in Guangdong used term “local citizenship” to describe the phenomenon restricted income and welfare redistribution to “indigenous residents” and excluded “nonhukou” migrants and even hukou migrants (Smart and Smart 2001). In this study local citizenship is applied on a different scale and has a somewhat different meaning than I have assigned to it.

“International Conference on China’s Housing Security Policies” held in Beijing in August 7, 2012. At this conference, some scholars called for making the formulation of housing security policies for rural migrants a priority. See Zhongguojingjishibao (China Economic Times), August 8, 2012.

In this table “urban citizenship rights” is used in order to be consistent with the study that presented this notion. It is arguable that in China’s pre-reform period, urban welfare entitlements differed fundamentally from standard citizenship-based social rights (Zhang 2014). Therefore, it may be more reasonable to use the term “urban privileged entitlements” instead, regardless of the origin of “urban citizenship rights”.

References

Cai, F (Ed.), (2008). Research on the 30 years of China’s labor and social security system reform. Economy and Management Publishing House.

Chan, K. W., & Buckingham, W. (2008). Is China abolishing the hukou system? The China Quarterly, 195, 582–606.

Chen, Y. (2005). “Peasant workers”: Institutional arrangements and status identification. Sociological Research, 3.

Cheng, T., & Selden, M. (1994). The origins and social consequences of China’s hukou system. China Quarterly, 139, 644–668.

Cheung, S.N.S. (1989). Privatization vs. special interests: The experience of China’s economic reforms. In J. A. Dorn, & W. Xi (eds.), Economic Reform in China: Problems and Prospects (pp. 21–32). The University of Chicago Press.

Department of Services and Administration for Floating Population, National Population and Family Planning Commission (Ed.). (2012). Report on China’s Migrant Population Development, 2012, China Population Publishing House.

Fan, C. C. (2001). Migration and labor-market return in urban China: results from a recent survey in Guangzhou. Environment and Planning A., 33(3), 479–508.

Gao, W. (2014). Urbanization of rural migrants to cities: Current situation, progress, and reform suggestions. Urban Insight, 2.

Guo, F., & Zhang, Z. (2012). The urban labor market status of China’s floating population (p. 1). No: Population Research.

Household Survey Office, National Bureau of Statistics (2013). Monitoring Survey Report on Migrant Workers in 2012. In F. Cai (Ed.), Reports on China’s Population and Labor No. 14—From Demographic Dividend to Institutional Dividend (pp. 1–15), Social Sciences Academic Press.

Jin, H., Qian, Y., & Weingast, B. R. (2005). Regional decentralization and fiscal incentives: Federalism, Chinese style. Journal of Public Economics, 89, 1719–1742.

Li, Q. (2004), Peasant workers and social stratification. Social Sciences Academic Press.

Li, R., et al. (2007). Toward Order: research on local regulations regarding administration of migrants. Social Sciences Academy Press.

Li, S. (2013). Current situation of rural migrant workers in the Chinese labor market (p. 1). No: Studies in Labor Economics.

Li, X., & Freeman, R. (2014). How does China’s new Labor Contract Law affect floating workers? (p. 3). No: Studies in Labor Economics.

Li, Y., & Luo, Y. (2014). Analysis of workers’ bargaining power based on Marxist economics (p. 5). No: Finance and Economics Sciences.

Lin, J. Y., Cai, F., & Li, Z. (1996). The China Miracle: Development Strategy and Economic Reform. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press.

Liu, X. (2011). Historical review, present dilemma, and rethinking about hukou status for higher education’s entrance examination. Journal of National Academy of Education Administration, No.11.

Marshall, T. H. (1950). Citizenship and social class, and other essays. Cambridge: The University Press.

Marshall, T. H. (1972). Value problems of welfare capitalism. Journal of Social Policy, 1(1), 15–32.

Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (Ed.). (2011). Yearbook of China’s Human Resources and Social Security (Work Volume) in 2011. Beijing: China’s Labor and Social Security Press.

Nee, V. (1989). A theory of market transition: From redistribution to markets in state socialism. American Sociological Review, 54, 663–681.

Nee, V. (1996). The emergence of a market society: Changing mechanisms of stratification in China. American Journal of Sociology, 101, 908–949.

Pang, N., Chen G. (2013). Decomposition of wage differential between urban local workers and migrant laborers. Population and Economy, 6.

Polanyi, K. (1944). The great transition: The political and economic origins of our time. New York: Rinehart.

Qian, Y., Rolan, G., & Xu, C. (1999). Why China is different from Eastern Europe? Perspectives from organization theory. European Economic Review, 43, 1085–1094.

Research team of hukou. (1989). Present system of hukou administration and reform of the economic system (p. 3). No: Academic Quarterly of Shanghai Social Sciences Academy.

Smart, A., & Smart, J. (2001). Local citizenship: welfare reform, urban/rural status, and exclusion in China. Environment and Planning A, 33, 1853–1869.

Solinger, D. J. (1999a). Citizenship issues in China’s internal migration: Comparisons with Germany and Japan. Political Science Quarterly, 114(3), 455–478.

Solinger, D. J. (1999b). Contesting citizenship in Urban China: Peasant migrants, the state, and the logic of the market. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sun, Y., Yao Y. (2012). National Development and Reform Commission is making the plan of the new urbanization. Economy and Nation Weekly, 17.

Szelenyi, I. (1978). Social inequalities in state socialist redistributive economy. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 19, 63–78.

Walder, A. G. (1986). Communist neo-traditionalism: work and authority in Chinese industry. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wang, Y., et al. (2007). Development path of China as a big country—on gains and costs of decentralized reform. Economic Research, 1.

Wang, X., (2009). From survival to being acknowledged: The issue of rural migrant workers under the perspective of citizenship. Sociological Research, 5.

Wang, F.-L., (2010), Renovating the great floodgate: The reform of China’s hukou system. In M. K. Whyte (Ed.), One Country, Two Societies: Rural-Urban Inequality in Contemporary China (pp. 335–364). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Whyte, M. K. (2010), The paradoxes of rural-urban inequality in contemporary China. In M. K. Whyte (Ed.), One country, two societies: Rural-Urban inequality in contemporary China (pp. 1–25).

Wu, J. (2010). Rural migrant workers and China’s differential citizenship: A comparative institutional analysis. In M. K. Whyte (Ed.), One country, two societies: Rural-urban inequality in contemporary China. (pp. 55–81).

Xie, G. (2007). Rural migrant workers and urban labor market. Sociological Research, 5.

Xin, C. (2008). Theoretical thinking about equity and efficiency of employment, income distribution and social security reform. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 1.