Abstract

The impacts of climate change are undeniable, and it is becoming increasingly difficult to dispute the science. What is less clear is the role of outdoor environmental education in educating participants with the knowledge and motivation to act. Experiential programs that take students outdoors seemingly provide the ideal context to equip students with knowledge and skills to be the vital change agents that the world needs. If outdoor educators are unconvinced of the impacts of climate change, then recent impacts on outdoor programming and practices should call attention to the issue. Changing climatic factors include increased temperatures, droughts, increased severity and frequency of storms, bushfires and floods, and national park closures. The implications of such impacts have not been widely considered, and our research aims to elucidate these concerns. This article uses a systematic literature review to examine the prevalence of climate change as a focus for published research in JOEE and its predecessor, AJOE. We conducted a qualitative analysis of the abstract of every single peer-reviewed paper and six themes emerged from our analysis of these articles. Findings from this review indicate that there is not a substantive focus on climate change in refereed articles published in the journal as only 14 of the 251 peer-reviewed articles published in AJOE/JOEE mentioned climate change. We conclude that more research needs to be undertaken to ascertain how outdoor environmental educators can facilitate a climate change curriculum and how outdoor environmental education programs in Australia are impacted by climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Current perspectives on climate change

The recent catastrophic and record-breaking floods along Australia’s East coast and Western New South Wales have been described as “climate change playing out in real time” (Verlie & Rickards, 2022, para 1). Flood events are one example of increasing catastrophic natural disasters impacting human and natural systems, infrastructure, mental health, and well-being. The floods have also impacted outdoor environmental education (OEE) programs where we work as academics at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Southeast Queensland, Australia. OEE is not impervious to climate change and anecdotally, we have witnessed an intensifying impact over the 30 years of our engagement in the outdoor education profession. For example, over the last two years floods have forced temporary closures of National Parks and forced the cancellation, rescheduling, or relocation of many of our own OEE field trips.

The degree to which climate change issues, and the pressing need for climate change adaptation, are addressed in outdoor education programs is unclear. However, the foreseen long-term impacts of climate change on outdoor education programs warrant further exploration and research. When we discuss climate change in this article, we define it as “long-term trends or shifts in climate over many decades. These changes may be due to natural variations (such as changes in the Earth’s orbit) or caused by human activities changing the atmosphere’s composition” (CSIRO, 2020, para. 2).

Climate change has been termed a ‘wicked’ problem due to its interconnected nature and the complexities in solving it. It intertwines political, economic, social, and environmental knowledge bases and interests (Head, 2014). Climate change in Australia and worldwide has accelerated at an alarming pace, causing more frequent and intense weather events (Grose & Bettio, 2020), such as “increased extreme heat days, to longer bushfire seasons and more intense rainfall events” (Quicke, 2021, p. 6). These events are predicted to escalate, bringing about further environmental, economic, and social impacts unless, according to the 2015 United Nations (UN) Climate Change Conference (COP), society can limit global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels (UNFCCC, 2022b).

At the 2021 COP Summit, progress was noted as nations reaffirmed their commitment to fulfilling their climate pledges (UNFCCC, 2022a). However, at COP27 in 2022, UN Secretary-General António Guterres said “The world still needs a giant leap on climate ambition.... We can and must win this battle for our lives” (UNCA, 2022, para. 1). Numerous authors have shared concerns that society has adopted a ‘business as a usual’ approach focusing on the “continued widespread political prioritisation of gross domestic product” (Raworth, 2017, p. e49), neoliberal agenda and frameworks (Warner et al., 2020), and climate coloniality legacies (Sultana, 2022) placing profit over the planet and halting or stifling the opportunity for change. An example of this is the Australian Government’s decision to allow the Adani Coal Mine in the Queensland Galilee Basin to go ahead, even though some have argued it “represents a huge setback in terms of Australia’s efforts to mitigate climate change” (Stutzer et al., 2021, p. 3). Furthermore, Australia’s inaction to transition to cleaner or renewable energy sources to achieve a net-zero emission plan was highlighted by being awarded the ‘colossal fossil’ award at the recent COP26 summit, exemplifying its continued dependence on coal and fossil fuel exports (Milman, 2021). Brett (2020) termed Australia’s dependence on coal “the coal curse” (p. 1) due to political denialism of climate change and the inaction to move away from a coal funded and fuelled society. Whitehouse (2021) deduces that this political denialism and its associated inaction has resulted in the lack of federal and state government commitment to climate education policies, investment, and support, resulting in an often non-existent, ad-hoc education curriculum on climate change.

In the seven years since the signing of the Paris Agreement, anthropogenic climate change impacts have been evidenced by the breaching of many rapid and irreversible tipping points (Lontzek et al., 2015) and planetary boundaries (Biermann, 2012). For example, Williams and de la Fuente (2021) have identified “long-term changes in populations of rainforest birds in the Australian Wet Tropics bioregion” as a “climate-driven biodiversity emergency” (p. 1). Intense and frequent heat waves are the main driving factors in the bird population’s demise and contraction to higher elevations. Williams and de la Fuente (2021) are not alone in their concern about the imminent impacts of climate change. According to The Climate of the Nation 2021 report, “75% of Australians are concerned about climate change” (Quicke, 2021, p. 4), this percentage reflects the highest level of concern since the report’s inception in 2007, whilst 67% concur that Australia should be a world leader in climate change solutions (p. 34). The need for urgent climate action resonates through terms such as ‘climate emergency’ (Flannery, 2020), ‘code red for humanity’ (United Nations, 2021), ‘climate-worry’ (Sciberras & Fernando, 2022), ‘climate action’ (United Nations, 2022), ‘adapting to climate change’ (Naughtin et al., 2022) and ‘Youth Climate Movement’(Hilder & Collin, 2022).

‘Outdoor Learning’ as a curriculum connection in the Australian F-10 rationale aims for students to develop “relationships, essential for the well-being and sustainability of individuals, society and our environment” and equip students with “the skills and understandings to move safely and competently” in natural environments (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), 2014, para. 6). At a tertiary level, seven threshold concepts guide and detail what OEE university graduates know and can do. These include place-responsive, social, and environmental justice pedagogies and practices, continual upskilling of knowledge and expertise, and understanding of safety, risk management and aversion to fatalities (Thomas et al., 2019). However, given Australia’s increased concerns regarding the real and present threats and impacts of climate change, combined with the pedagogical intent of outdoor learning and tertiary OEE programs, it is not clear if outdoor environmental education in Australia is leveraging or fulfilling its moral imperative to enact its curriculum, educate students about climate change, equip them with climate adaption and resilience skills, and instil in them the motivation to advocate for climate action.

Climate inaction impacts Australians in various ways through: increased insurance fees; damage to, or loss of, property; disruption to supply chains; loss of income; and impacts on people’s mental and physical health (Quicke, 2021). Climate inaction has also undermined, diffused and fragmented the development of a climate change curriculum. Colliver (2017) exemplifies this as she finds it “puzzling, given climate change is a major issue for humankind, that the Australian Curriculum does not make more explicit mention of climate change as a topic for learning” (p. 75). Stewart in Quay et al. (2020) refers to climate change as a ‘wicked problem’ that “has been the elephant in the room for some time” (p. 110). The phrase ‘elephant in the room’ is a metaphorical term, highlighting an issue, topic or question that is potentially controversial or challenging that is being ignored despite its obvious presence. Climate change is a significant issue. However, it is rarely addressed, referred to, or discussed, as it has the potential to cause controversy. Stewart highlights the dramatic impact climate change is currently having on OEE programs in Australia and worldwide, including changing environmental contexts, changes in precipitation, snowfall patterns, and temperatures. These climate change impacts have resulted in shorter time frames or windows in which to run OEE activities and venue accessibility has also become an issue. Additionally, environmental safety concerns are escalating with climate change increasing the exposure to the risk of injuries, loss of life, mid-program evacuations, and the postponement and cancellation of programs. Increasing financial pressures of changing climate on OEE programs include the loss of income and additional funds needed for training and resource needs (Miller, 2022). Despite these concerns and pressures mounting, it may be plausible that some outdoor environmental education business models, programs, policies, and practices perpetuate the realities of anthropogenic climate change through their ingrained association with neoliberal capitalism and consumerism (Giroux, 2015).

There appears to be a paucity of literature describing how OEE can enact a climate change pedagogy which supports young people and adult learners to build the knowledge, skills and capability needed to participate in and contribute to a climate-resilient future. (Victorian State Government, 2022). Outdoor Environmental Education seems ideally placed as a learning platform, pedagogy, and vehicle for climate change education through its unique disposition incorporating practical and experiential learning opportunities, place-based pedagogies, and connection to Country that other disciplines may not offer. Wayman (2018) encapsulates these thoughts, explaining that “outdoor and adventure education offers a unique chance to correlate issues such as … climate change and sustainability … into everyday life and connect them to similar ideas, to the lived experiences of participants” (p. 176). One example occurred for Robyn (lead author), when teaching at Mt Seewah Lookout during a multi-day expedition circumnavigating the Cooloola National Park on the Sunshine Coast in Queensland, Australia. Whilst on the lookout, the group, caught glimpses of humpback whales breaching in the Coral Sea to the East and watched sailboats in the shallow bracken waters of Lake Cootharaba to the West. Amidst the spectacle and beauty, a discussion ensued about rising sea levels. Students deliberated whether this area would be accessible for them to run similar multi-day trips in the future with the impact of climate change causing rising sea levels (CSIRO & BOM, 2020). We concur with Cutter-Mackenzie and Rousell’s (2019) view that climate change education is an innovative, effective, and emerging field of practice and research that moves beyond the discipline boundaries of education for sustainability, sustainable development and environmental education. In this way, climate change education is viewed as “fundamentally responsive and accountable to the rapidly changing environmental conditions of everyday life” (Cutter-Mackenzie & Rousell, 2019, p. 101), which includes children and youth perspectives, experiences, and advocacy. Insights gained from these significant life experiences and formative influences (Howell & Allen, 2019) signify the value of experiential learning and reflective pedagogies (Thomas, 2015) used in OEE. Furthermore, it highlights the possibilities of an OEE climate education pedagogy in which climate change is positioned front and centre.

The purpose of this article is to explore the extent to which climate change is a focus in research and writing published in the Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education (JOEE) and the superseded Australian Journal of Outdoor Education (AJOE) since 1998. To facilitate this exploration, we conducted a systematic literature review to ascertain the extent to which climate change is being discussed, researched, and showcased in the journals’ peer-reviewed articles and to identify themes, gaps, and future research opportunities regarding the inclusion of climate change foci in OEE.

Methodology

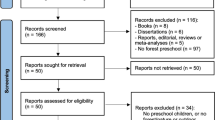

The methodological approach taken in this academic inquiry is that of a systematic literature review. We have used a comprehensive, protocol and parameter-driven, quality-focused approach to searching, selecting, and summarising literature pertinent to our research focus (Bearman et al., 2012). This literature review focused solely on peer-reviewed articles published in the AJOE and JOEE from 1998 (volume 3, issue 1—when articles were first peer-reviewed), to 2021 (volume 24, issue 3). Editorials and book reviews were excluded from the review. This study incorporated, and built on, the data collected and analysed by Thomas et al. (2009) and utilised the framework they used when they analysed articles published in three outdoor/experiential journals. Thomas et al. (2009) to “provide an overview of the peer reviewed research that has been published in the last decade in order to reveal strengths, weaknesses, gaps, and what we perceive to be blind spots” (pp. 16–17). In this study, we utilised some of their existing data analysis and continued the analysis of articles published in AJOE/JOEE beyond 2007 up to the present time.

The article analysis we conducted categorised and coded all the published articles in the following areas: Author affiliation, the type of article, the context of each article, and the article focus (primary and secondary). The definitions of the categories and the codes used within each category are shown in Table 1. We checked the coding of all the AJOE articles published between 1998 and 2007 analysed by Thomas et al. (2009) before continuing to code all the articles published in the AJOE/JOEE from 2007. In total, 251 articles were coded and included in the data set. Having clear code definitions ensured coding consistency and reliability. A cross-checking process between coders was also employed to ensure consistency and increase trustworthiness. We did this by cross-checking a random sample (N = 20) of the new articles published since 2007 to confirm consistency with the original coding completed in the research conducted by Thomas et al. (2009).

The plan was to then highlight the articles that had a primary and secondary focus on climate change and then conduct a more detailed analysis of those articles. However, the fact that there was only one (N = 1) article had a secondary focus on climate change led us to take a different approach to expand the data set. Hence, we conducted a search of the remaining 250 articles for any references to climate change, which resulted in a data set of 13 articles that addressed climate change in some way. The relevant sections from the single article with a secondary focus on climate change, and the additional 13 articles that addressed climate change, were then imported into Nvivo (a data analysis software) and scrutinised for relationships, trends, and patterns (D. Gough et al., 2017). Based on this analysis, six themes emerged; the nature of climate change, the citing of climate change in reports, the transboundary nature of climate change impacts, climate change impacts on OEE programs, education and climate change and a call to action. The 14 articles were also analysed to determine author affiliation, the type of article, the context, and the focus (primary and secondary). These data will also inform the discussion that follows.

Findings and discussion from the systematic literature review

The analysis of the primary and secondary foci of the 251 articles is outlined in Table 2. The most common foci of the articles were Outcomes/effects/participant experiences (38.2% of all 251 articles) and Program design and facilitation (35.9%), which is consistent with the findings reported by Thomas et al. (2009). Authors of articles in the Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education are still primarily focused on program outcomes and how a program can be designed and facilitated to achieve those outcomes. A further four foci feature prominently across the total 251 articles: Theoretical foundations (18.7%); Relationships with nature/self/others (18.7%); Curriculum issues (12.7%); and Profession/professional issues (12.4%). Of specific interest to this article, only a limited number of articles had a primary or secondary focus on either the Anthropocene (0.4%) or Climate change/crisis (0.4%).

The paucity of articles focused on climate change/crisis in the JOEE (as shown in Table 2) is concerning, and it is unclear why there has been so little focus on this topic in the journal. Whilst the data needs to be interpreted carefully, the underrepresentation of climate change/crisis in the JOEE indicates that climate change has not been a priority focus of research and writing by outdoor environmental education researchers, or they are choosing to publish that research elsewhere. It is possible that outdoor environmental education researchers are publishing their work in journals with a stronger climate change focus. Another explanation for the apparent gap in the literature may be the lack of reference or acknowledgement of the need for climate change education in the Australian Curriculum. For instance, the 2019 Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration, which sets out the educational goals for all young people for the next ten years, has omitted reference to climate change, which was included in the previous 2009 Melbourne Declaration (A. Gough, 2020). It is unclear how outdoor environmental educators in Australia, and other countries, might educate their students on climate change and mitigate against its impacts if researchers and writers do not address the issue in journals such as JOEE.

Additional analysis of articles that mention climate change in the systematic literature review

Although only one article contained a secondary focus on climate change/crisis, as seen in Table 2, 14 articles (5.6% of the 251 articles) specifically mention or refer to climate change (refer to Table 3 for details). Of those 14 articles, the overall primary focus was spread across ten focus areas, with the two most significant representations being Relationships with nature/self/others (36%) and Sustainability/stewardship (14%). The other categories included: the Anthropocene (7%); Curriculum Issues (7%); Environmental/ecological/spiritual (7%); Profession/professional issues (7%); Program design/ facilitation (7%) and Research processes (7%). Interestingly, no articles in this data set included the term climate change in its title.

The authors of the 14 articles in the data set were affiliated with institutions from Australia (43%), the United States (21%), NZ (14%) with Canada (7%), Europe (7%) and Asia/ Middle East (7%). Of note, none of the lead authors published more than one article on climate change in the data set. A possible explanation for this maybe that climate change in OEE has not been a central research area for outdoor environmental education academics.

In terms of the types of articles in the data set, position papers and research reports accounted for 78% and 22%, respectively as shown in Table 3. These results illustrate that more empirical research is warranted to rigorously explore the impacts of changing climate on OEE programs and practices, how OEE programs address these impacts, and how OEE might effectively contribute to climate change education. Furthermore, the contexts of various articles that referred to climate change reflect the diversity of OEE, consistent with the findings reported by Thomas et al. (2009). For example, 29% of the articles focused on outdoor environmental education, 21% on place pedagogy, 21% on outdoor education, and 7% on each of adventure education, environmental activism, forest schools, and service learning.

The term ‘climate change’ was referred to 70 times within the 14 articles in the data set as reflected in Table 4 below. Gough’s (2007) article was the first to mention climate change. The article referred to climate change seven times regarding curriculum issues within outdoor education (OE) on integrating the Education for Sustainable Development Agenda. The article which incorporated the most references to climate change was Haq et al. (2020) article regarding environmental activism in Pakistan. Their article was categorised with a secondary focus on climate change/crisis, referring to climate change 19 times. Over time, the number of citations regarding ‘climate change’ in the JOEE has increased, with the term being cited 83% more in the last four years, from 2018 to 2021. Also noted were periods of infrequent use of the term; these periods were from 2008 until 2011 and then from 2013 to 2018.

Other phrases associated with climate change within the articles included ‘global warming’ (A. Gough, 2007; Haq et al., 2020), ‘increasingly rapid change in climate’ (Morse et al., 2018), ‘climate-threatened resources’ (Zajchowski et al., 2021), ‘Anthropocene global heating and climate destabilisation’ (Blades, 2021), ‘abruptly changing weather patterns,’ ‘climate changes,’ ‘climate emergency,’ ‘climate exposures’ (Haq et al., 2020), ‘changes in climate’ (McGregor & McGregor, 2020), ‘climate crisis’ (Quay et al., 2020), and ‘climate regimes’ (Zajchowski et al., 2021). The wide variety of words and phrases used to describe climate change, and its impacts in the JOEE potentially dilute the importance and impact of the issue for OEE policymakers, programmers, and practitioners. Implementing a common language framework regarding climate change would help it gain more clarity, voice, and agency.

Findings and discussion from the thematic analysis of the articles that refer to climate change

The six distinct themes that emerged through the thematic analysis of the articles that referred to climate change are: the nature of climate change, the citing of climate change in reports, the transboundary nature of climate change impacts, climate change impacts on OEE programs, education and climate change; and a call to action. These themes provide a snapshot of the breadth of writing regarding climate change in the JOEE, helping to identify potential literature gaps and describing the impacts that climate change has caused in the context of OEE. These six themes will now be described and summarised in more detail.

The nature of climate change

This theme highlights the complex range of contexts used when describing climate change found in the data set of articles in the JOEE. Eight of the 14 JOEE articles on climate change contributed to this theme. These contexts included: weather and climate events; phenomena related to weather and climate extremes; climate change impacts human systems and the more-than-human world, and climate change impacts human health and well-being.

Weather and climate events referred to in the JOEE include heatwaves, cloudbursts, cyclones, floods, and sea intrusion (Haq et al., 2020), sea-level rise (Hill, 2012), droughts (Gough, 2007; Quay et al., 2020) and bushfires (Quay et al., 2020). Phenomena related to weather and climate extremes were outlined by Hill (2012), as he referred to human-induced (anthropogenic) climate change, citing increased greenhouse gas emissions as a significant contributor to climate change in Australia.

Climate change impacts, regarding human systems, and the more-than-human world mentioned in the JOEE, underly many challenging environmental issues of climate change (Meltzer et al., 2020). This challenge is reflected by Haq et al. (2020), who describe heightened levels of human vulnerability caused by increased air pollution, deforestation, urbanisation, famine, and water scarcity. Morse et al. (2018) bring a sense of urgency to the discussion of climate change using words such as ‘tipping points,’ ‘irreversible changes,’ caused by the “emerging geological epoch, sometimes called the Anthropocene,” regarding the “loss of species, habitats and entire ecosystems” (p. 244). Quay et al. (2020) also highlight the devastating impacts of climate change through droughts, habitat destruction, and the 2019–2020 Australian bushfires, emphasising the impacts beyond humans, including those to the more-than-human world. However, climate change impacts are not always visible and are often only observable over long periods of time. Blades (2021) captures this sentiment as she refers to the “macro-scale impacts of climate change over time on mountainScape” in her descriptive summary of her first research question, “What is afforded and felt whilst walking with/in nature(s)?” (p. 305). This description paints a picture of the devastation climate change renders upon areas we use for bushwalking and other outdoor activities over time. This slow, occurring change may not be readily observed on OEE trips unless participants repeatedly visit an area over an extended time frame. Hence, the change(s) would most likely be needed to be explicitly highlighted and taught. The nature of climate change is reflected in human health and well-being. Blenkinsop and Ford (2018) discuss some of the psychological responses felt by learners, such as “regret, sadness, and loss” (p. 236), as participants feel alienated from and unable to respond to threats to the natural world.

The citing of climate change reports

Several of the JOEE articles in the data set for this study cite United Nations and Governmental reports and documents, which enhances the credibility and relevance of that writing. For example, Gough (2007) referred to the United Nations Decade Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) framework. Morse et al. (2018) referred to two Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, whilst Hill’s (2012) article referred to the 2011 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. At a national level, Haq et al. (2020) refer to Pakistan’s 2017 Climate Change Act, enabling climate change to be “accepted and addressed as a serious issue” (p. 287). Finally, McGregor and McGregor’s (2020) article referred twice to documents signed by the Victorian Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change at a state level.

Referring to these documents improves credibility (Lampert, 2020), enhances the agreed understanding of the term climate change, and shows how climate change has been addressed over time. For example, The Climate Change 2021 IPCC report is compiled by a team of 234 scientists worldwide who reviewed over 14,000 articles (Spera, 2021). Thomas et al. (2019) describe seven threshold concepts that detail what OEE university graduates know and can do. Threshold concept number four stipulates, “outdoor educators advocate for social and environmental justice” (p. 10). Promoting the use of key climate change documents by OEE facilitators in provocations, discussions and debates regarding climate change and human impact on the planet will provide authenticity and help mitigate fake news, misinformation, hearsay, and climate change denial.

Climate change and impacts on OEE

Climate change is already impacting OEE programs by changing the accessibility of locations closed by land managers, by creating scheduling difficulties for programs caused by dangerous weather and fire risks, and other safety and risk considerations caused by extreme weather conditions. For example, Quay et al. (2020) highlight the disruptive nature of climate change and the need to rethink OEE pedagogy and curriculum, as fires caused “widespread cancellation or deferral of OEE programs across the south-eastern parts of the country” (p. 109). This sentiment had been discussed by Gough (2007) nearly 15 years prior as she highlighted the impacts of drought on inland waterways reducing the locations where outdoor activities were able to be undertaken. However, these were the only two examples from the JOEE which explicitly showcased or highlighted the impact of climate change on OEE programs.

The transboundary nature of climate change impact

Climate change influences and impacts are not confined to a physical location or single context: in this respect, they are transboundary (Zajchowski et al., 2021). For this reason, climate change has often been termed a ‘wicked’ problem and ‘threat multiplier’ due to its interconnected nature and complexities, as it intertwines political, economic, social and environmental knowledge bases and interests (Head, 2014). The transboundary nature of climate change impacts highlighted within the JOEE reflects its complex nature and its direct and indirect impacts on OEE programs in both the human and more-than-human spheres. It also raises the questions of how we plan for, and who is responsible for, transboundary climate impacts?

Protected areas, such as National and State Parks, where many OEE programs are undertaken, are impacted by the transboundary nature of climate change. For example, Zajchowski et al. (2021) highlight the “transboundary challenges of ecosystem management in the Anthropocene” (p. 93). They use Australia’s ‘Great Barrier Reef’ as an example, highlighting the impacts of geological, social, cultural, and economic activities external to the protected area, impacting the reef and its associated ecosystems.

The impacts of climate change, exemplified in times of “global environmental threats, social issues and economic instability” raised by Hill (2012, p. 16), are still relevant and have implications for OEE. Quay et al. (2020) stress the interrelated issues of COVID-19, climate change and the neoliberal capitalist system, which “unleashed untold destruction across the globe... for residential centres and outdoor professions, the pandemic has been a disaster” (p. 107). Quay et al.’s article provides acumen for the outdoor environmental education sector moving forward post-COVID-19. It proposes how OEE’s core values could guide the shift away from a neoliberal capitalist system as it seeks to incorporate Indigenous knowledge, the more-than-human entities, student and planetary health and well-being, and students’ voices and advocacy into critical conversations. These core values would be taught through OEE practices utilising inclusive, student-centred, placed-based learning and community-building engagements in natural environments.

Another aspect showcasing the transboundary nature of climate change in the JOEE is the social-ecological transboundary impact of climate change. Zajchowski et al. (2021) examine this tension through the premise of ‘last-chance tourism.’ They question if last-chance tourists feel ambivalent and hold the mindset that they are at the “Earth’s going out of business sale” (p. 95). Therefore, they participate in the experience in ways that perpetuate climate change’s impacts absolve them of any responsibility or environmental ethic. However, they explain that these ‘tourism experiences’ can be crafted and facilitated in ways that allow participants to connect with nature and develop pro-environmental actions, often fostered through immersive outdoor experiences, service learning, or ecological restoration education projects (Hansen & Sandberg, 2019).

The failings of politics, short term governance and political decisions regarding climate change and nature preservation, potentially impacting freedoms for future generations, reflect the transboundary impacts of climate change inaction over time. Zajchowski et al. (2021) raise concern, citing the variances in climate policies and initiatives between the Obama and Trump terms of office, asking the question of who is responsible “when accounting for international impacts of climate change on outdoor recreation?” (p. 92). Questions such as these, could be used as prompts or provocations for OEE stakeholders (facilitators, students, and policymakers) to debate and discuss as they advocate “for social and environmental justice” through the lens of OEE (Thomas et al., 2019, p. 178). In this way, OEE programs could engage all stakeholders in critical discourses and engagements regarding politics and climate change, cultivating ways to foster a sense of hope, action, and responsibility.

Education and climate change

The presence of discussion relating to climate education and climate change’s impacts on education in the JOEE was minimal, given education’s crucial role in advocating for a sustainable future. The concerns raised in Gough’s (2007) article regarding the coverage and reference to climate change in the VCE OES curriculum studies design (Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority, 2005); considering its prominence, being designated one of the critical environmental perspectives of the education for sustainable development framework and “the widespread impact climate change could have on outdoor activities” (p. 26) still hold true 15 years later. Current pedological practices and policies should support young people and their concerns about the future. It is disappointing that the current 2019 Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration does not refer to climate change (Gough, 2020).

Another significant aspect of climate education highlighted by Johns and Pontes (2019) is the need for continual informal adult eco-literacy. They have noticed a gap in adults’ eco-literacy skills, expressing that many adults lacked the skills to critically engage in complex discussions regarding climate change, biodiversity loss, and greenhouse gas emissions, inferring that these skills would become intergenerational.

The impacts of “climate change disruptions” expressed by Stewart in (Quay et al., 2020, p. 111) highlight the vulnerability of OEE’s position in the Higher Education (HE) sector. Stewart conveys that academics need to “rethink OEE pedagogy and curricula” (p. 111), ensuring its viability and relevance in uncertain times within HE, as it is times of vulnerability (highlighted by the deferment and cancellations, albeit floods or fires) that in the past OEE programs: often considered small niche fields in universities, have been cut from HE funding and programs. The vulnerability of OEE discourse in the HE sector was also expressed by Dyment and Potter (2020). They encourage OEE programs to align themselves with universities’ critical strategic plans, which parallel many OEE theoretical foundations of sustainability, place-based education, and social and environmental justice.

A call to action

Outdoor Education Australia, the owner of the JOEE, provides a resource hub for outdoor educators. Their webpage identifies OEE as a pedagogical practice that ‘calls people to action’ through the ideals of “stewardship and sustainability” (Outdoor Education Australia, 2015, para 5.). The concepts of environmental action, stewardship and sustainability resonate in diverse ways throughout the JOEE articles concerning climate change. For example, the Blenkinsop and Ford (2018) article identified that the fields of OEE have aligned themselves with “making the world a just and caring place” (p. 319) with the need to “create something ready to respond to the educational challenge par excellence of today – an adequate response to the massive social/ecological/cultural destructions happening right now” (p. 320). They, along with (Morse et al., 2018), proposed that this change could be undertaken under the ‘wilding of pedagogies education.’

Environmental activism is another way in which people can advocate for climate action. Haq et al. (2020) highlight youth activism’s rising prominence and role through the ‘Global Youth Strike Movement’ raising awareness and advocating for environmental and climate action through marches, clean-ups, education, and awareness campaigns. Another form of environmental activism, cultural ecofeminism, was discussed by (Haq et al., 2020), in which women advocate for environmental justice as “their environmental knowledge can execute climate change issues more effectively” (p. 277) due to the role that they play as the primary supervisors of the family unit and the ecological knowledge embedded within this role.

Alcock and Ritchie, in their (2018) article regarding Forest Schooling in New Zealand, encourage and challenge educators not to over romanticise the concepts of natural and wild places, nature and Forest School pedagogy, which they claim “perpetuate colonial legacies” (p. 86). Instead, they encourage readers to apply “Indigenous Māori worldviews of humans inter and intra-actively living, playing, knowing, and relating within a forest and other wild spaces” in an era of “increasing threats of climate change disturbances” (p. 86). Blades (2021) shares a similar sentiment as she invites her readers to question and challenge “enduring colonial legacies” (p. 294) through their OEE pedagogies, practices and research in the times of the “Anthropocene’s global heating and climate destabilization play havoc with Australian natural and social environments, including Education” (p. 294). Embedding the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures priority (ACARA, 2016) and the OEE university threshold concept, “outdoor educators are place-responsive, and see their work as a social, cultural and environmental endeavour” (Thomas et al., 2019, p. 177), should act as a catalyst for critical discussion and nuanced ways of undertaking decolonisation practices.

The need to embed sustainable principles and practices into OEE programs is another ‘call to action’ in the data set of articles in this study. Hansen and Sandberg (2019) challenge humans to reduce their current ecological footprint and act as “socio-ecologically responsible citizens”(p. 65), preserving the world for future generations at a time in which the world is undergoing “rapid climate change and fiery debates regarding human responsibility” (p. 65). Through the success of integrating ecological restoration education projects into OEE programmes in Nordic counties, they encourage these restoration projects to be adopted worldwide. Furthermore, ecological restoration education provides students with direct experiences in nature, shedding “new light on the role of humans in the biosphere” (Hansen & Sandberg, 2019, p. 66), connecting them to the more-than-human world whilst fostering “greater concern and knowledge about the loss of biodiversity and climate change” (p. 58). The diversity of literature in the JOEE regarding a ‘call to action’ concerning climate change highlights the multiple ways in which all OEE stakeholders can undertake climate action and mitigate against the impacts of a changing climate.

Conclusions and recommendations

This systematic literature review has highlighted the extent to which ‘climate change’ has been a focus of the research published in the JOEE and AJOE. The findings identify that climate change is not a prominent focus area of articles published in these journals, reflected by the low number of articles (N = 14) that refer to climate change, the fact that none of the articles had a primary focus on climate change, and that no lead authors have published more than one article on this topic within the JOEE. Although some discussion of climate change was noted in the 14 articles across the six identified themes, as well as a sharp rise reported (83%) in reference to ‘climate change’ citations in the four years, from 2018 to 2021, the discussion of how climate change could and is impacting OEE programs is limited, and there was little discussion of how OEE could enact an effective climate adaptive curriculum. It is unclear why the topic of climate change has not been discussed in more detail within the JOEE, given the compounding implications that it is and will have for OEE programs and the profession. It may be that the challenge of embedding a climate change curriculum in OEE has not been tackled due to its controversial nature, depressing content, and the lengthy time frames required to effectively study climate change.

Acknowledging the impacts of a changing climate and embedding a climate education curriculum in OEE, could also be seen as a double-edged sword. The positives of doing so, could be viewed through the lens of transformative change. The benefits might include empowering youth advocacy, developing deeper connections to Country and the more than human world, upskilling youth and OEE practitioners with resilience, critical thinking and adaptability skills to participate in and respond to a climate-resilient future. At the other edge of the sword, hard work would be needed to develop new OEE policies, programs, and practices. Funds, time and energy would need to be redirected from the perceived ‘bread and butter’ of OEE, adventure education, to incorporate emergent practices, train staff to understand the science behind climate change and the impacts of climate change and provide them with the knowledge and skills to advocate for environmental justice to assist students to deal with climate-worry. Finally, parents and schools would need to buy into a different way of doing OEE, based on deep connections to Country and place.

This article has identified the need for future research regarding the impact of climate change in the Australian OEE space. There is also a need to explore the development and implementation of a climate change curriculum within OEE, relevant to the Australian context. This research might include, but not be limited to: a systematic review of other journals (for example, the Australian Journal of Environmental Education) concerning climate change; a study regarding current climate change impacts on OEE programs in Australia; a review of climate change education in OEE settings; and a study regarding the OEE profession’s preparedness to ensure outdoor educators are equipped to cope with the impacts of climate change and students’ climate-worry and grief. To raise the profile of climate change dialogue within the JOEE, a special edition of the JOEE calling for articles on climate change in OEE would be helpful. This could assist with the development and use of a common language framework and give voice and agency to OEE stakeholders who can write on the issue.

As practitioners who have collectively spent over 60 years facilitating OEE experiences, it would be devastating to see the OEE programs rendered inoperable in Australia due to climate change impacts, especially when much can be done to alleviate the impacts of a changing climate. We urge all OEE stakeholders to become more active in this space, advocating and providing a voice for the health and prosperity of the human and the more-than-human world. As explained by John Lewis (Loyd, 2020) “If not us, then who? If not now, then when?” (para.1).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alcock, S., & Ritchie, J. (2018). Early childhood education in the outdoors in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-017-0009-y

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2014). Outdoor Learning. Online: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/resources/curriculum-connections/portfolios/outdoor-learning/

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2016). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures (Version 8.4). Retrieved from https://www.acara.edu.au/curriculum/foundation-year-10/cross-curriculum-priorities/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-histories-and-cultures-ccp

Bearman, M., Smith, C. D., Carbone, A., Slade, S., Baik, C., Hughes-Warrington, M., & Neumann, D. L. (2012). Systematic review methodology in higher education. Higher Education Research and Development, 31(5), 625–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.702735

Biermann, F. (2012). Planetary boundaries and earth system governance: Exploring the links. Ecological Economics, 81, 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.02.016

Blades, G. (2021). Making meanings of walking with/in nature: Embodied encounters in environmental outdoor education. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 24(3), 293–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-021-00087-6

Blenkinsop, S., & Ford, D. (2018). The relational, the critical, and the existential: Three strands and accompanying challenges for extending the theory of environmental education. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(3), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-018-0027-4

Brett, J. (2020). Resources, climate and Australia’s future. Quarterly Essay, 78, 1–81.

Colliver, A. (2017). Education for climate change and a real-world curriculum. Curriculum Perspectives, 37, 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-017-0012-z

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation. (2020). What is climate change? Climate change refers to any long-term trends or shifts in climate over many decades. Retrieved from https://www.csiro.au/en/research/environmental-impacts/climate-change/climate-change-qa/what

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, & Bureau of Meteorology. (2020). State of the climate 2020. Retrieved from Online: https://www.csiro.au/state-of-the-climate

Cutter-Mackenzie, A., & Rousell, D. (2019). Education for what? Shaping the field of climate change education with children and young people as co-researchers. Children’s Geographies, 17(1), 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2018.1467556

Dyment, J. E., & Potter, T. G. (2020). Overboard! The turbulent waters of outdoor education in neoliberal post-secondary contexts. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 24(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-020-00071-6

Flannery, T. F. (2020). The climate cure: Solving the climate emergency in the era of COVID-19. Text Publishing.

Giroux, H. (2015). Henry Giroux on the rise of neoliberalism. Humanity & Society, 39(4), 449–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160597615604985

Gough, A. (2007). Outdoor and environmental studies: More challenges to its place in the curriculum. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 11(2), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03400854

Gough, A. (2020). Educating Australia on the climate crisis: Despite its obvious benefits, governments are neglecting climate learning in the school curriculum. Retrieved from Online: https://www.policyforum.net/educating-australia-on-the-climate-crisis

Gough, D., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2017). An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Grose, M., & Bettio, L. (2020). Prepare for hotter days, says the State of the Climate 2020 report for Australia. The Conversation: Australian Edition. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/prepare-for-hotter-days-says-the-state-of-the-climate-2020-report-for-australia-149430

Hansen, A. S., & Sandberg, M. (2019). Reshaping the outdoors through education: Exploring the potentials and challenges of ecological restoration education. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 23(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-019-00045-3

Haq, Z. A., Imran, M., Ahmad, S., & Farooq, U. (2020). Environment, Islam, and women: A study of eco-feminist environmental activism in Pakistan. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 23(3), 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-020-00065-4

Head, B. W. (2014). Evidence, uncertainty, and wicked problems in climate change decision making in Australia. Environment and Planning. C, Government & Policy, 32(4), 663–679. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1240

Hilder, C., & Collin, P. (2022). The role of youth-led activist organisations for contemporary climate activism: The case of the Australian Youth Climate Coalition. Journal of Youth Studies, 25(6), 793–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2022.2054691

Hill, A. (2012). Developing approaches to outdoor education that promote sustainability education. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 16(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03400935

Howell, R. A., & Allen, S. (2019). Significant life experiences, motivations and values of climate change educators. Environmental Education Research, 25(6), 813–831. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1158242

Johns, R. A., & Pontes, R. (2019). Parks, rhetoric and environmental education: Challenges and opportunities for enhancing ecoliteracy. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 22(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-019-0029-x

Lampert, M. (2020). Glocalities Report: Trust in the United Nations. Retrieved from https://glocalities.com/reports/untrust

Lontzek, T. S., Cai, Y., Judd, K. L., & Lenton, T. M. (2015). Stochastic integrated assessment of climate tipping points indicates the need for strict climate policy. Nature Climate Change, 5(5), 441–444. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2570

Loyd, F. (2020). The Legendary John Lewis: If not us, then who, if not now, then when? Retrieved from https://chrishildrew.wordpress.com/2015/06/21/assembly-if-not-us-then-who/

McGregor, B. A., & McGregor, A. M. (2020). Communities caring for land and nature in Victoria. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 23(2), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-020-00052-9

Meltzer, N. W., Bobilya, A. J., Mitten, D., Faircloth, W. B., & Chandler, R. M. (2020). An investigation of moderators of change and the influence of the instructor on outdoor orientation program participants’ biophilic expressions. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 23(2), 207–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-020-00051-w

Mertens, D. M. (2005). Research and evaluation in education and psychology: Integrating diversity with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods (2nd ed.). Sage.

Miller, L. (2022). Outward Bound Australia’s Transformation through Bushfires and Pandemic: Multi-faceted turnaround strategies and considerations for the future of outdoor education. Paper presented at the 9th International Outdoor Education Research Conference (IOERC9), University of Cumbria, Ambleside, Cumbria, LA22 9BB UK.

Milman, O. (2021). Australia named ‘colossal fossil’ of Cop26 for ‘appalling performance’: Climate Action Network give unwanted prize of worst country at the talks to Australia for its ‘breathtaking ineptitude’. The Guardian: Australian Edition. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/nov/12/australia-named-colossal-fossil-of-cop26-for-appalling-performance

Morse, M., Jickling, B., & Quay, J. (2018). Rethinking relationships through education: Wild pedagogies in practice. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(3), 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-018-0023-8

Naughtin, C., Hajkowicz, S., Schleiger, E., Bratanova, A., Cameron, A., Zamin, T., & Dutta, A. (2022). Our future world: Global megatrends impacting the way we live over coming decades. CSIRO.

Outdoor Education Australia. (2015). Outdoor education (OE) focuses on learning about self, others and the environment: Rationale for Outdoor Ed. Retrieved from https://outdooreducationaustralia.org.au/education/rationale-for-oe/

Quay, J., Gray, T., Thomas, G., Allen-Craig, S., Asfeldt, M., Andkjaer, S., . . . Foley, D. (2020). What future/s for outdoor and environmental education in a world that has contended with COVID-19? Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 23(2), 93-117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-020-00059-2

Quicke, A. (2021). Climate of the Nation 2021: Tracking Australia’s attitudes towards climate change and energy. Retrieved from https://australiainstitute.org.au/report/climate-of-the-nation-2021/

Raworth, K. (2017). A doughnut for the anthropocene: Humanity’s compass in the 21st century. The Lancet. Planetary Health, 1(2), e48–e49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30028-1

Sciberras, E., & Fernando, J. W. (2022). Climate change-related worry among Australian adolescents: An eight-year longitudinal study. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 27(1), 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12521

Spera, S. (2021). 234 scientists read 14,000+ research papers to write the IPCC climate report – here’s what you need to know and why it’s a big deal. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/234-scientists-read-14-000-research-papers-to-write-the-ipcc-climate-report-heres-what-you-need-to-know-and-why-its-a-big-deal-165587

Stutzer, R., Rinscheid, A., Oliveira, T. D., Loureiro, P. M., Kachi, A., & Duygan, M. (2021). Black coal, thin ice: The discursive legitimisation of Australian coal in the age of climate change. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 8(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00827-5

Sultana, F. (2022). The unbearable heaviness of climate coloniality. Political Geography. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102638

Thomas, G. (2015). Signature pedagogies in outdoor education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 6(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2015.1051264

Thomas, G., Grenon, H., Morse, M., Allen-Craig, S., Mangelsdorf, A., & Polley, S. (2019). Threshold concepts for Australian university outdoor education programs: Findings from a Delphi research study. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 22(3), 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-019-00039-1

Thomas, G., Potter, T. G., & Allison, P. (2009). A tale of three journals: A study of papers published in AJOE, JAEOL and JEE between 1998 and 2007. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 13(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03400876

United Nations. (2021). Secretary-General Calls Latest IPCC Climate Report ‘Code Red for Humanity’, Stressing ‘Irrefutable’ Evidence of Human Influence [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sgsm20847.doc.htm

United Nations. (2022). Sustainable Development Goals: Goal 12: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/climate-change/

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (2022a). The Glasgow Climate Pact: Key outcome from COP26. Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-glasgow-climate-pact-key-outcomes-from-cop26

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (2022b). The Paris Agreement. Retrieved from https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement

United Nations Climate Action. (2022). COP27: Delivering for people and the planet. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/cop27

Verlie, B., & Rickards, L. (2022). Make no mistake: these floods are climate change playing out in real time. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/environment/climate-change/make-no-mistake-these-floods-are-climate-change-playing-out-in-real-time-20220302-p5a11y.html

Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority. (2005). Outdoor and environmental studies study design (Revised). Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority.

Victorian State Government. (2022). Education and Training Climate Change Adaptation Action Plan 2022–2026. Victorian State Government.

Warner, R. P., Meerts-Brandsma, L., & Rose, J. (2020). Neoliberal ideologies in outdoor adventure education: Barriers to social justice and strategies for change. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 38(3), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.18666/JPRA-2019-9609

Wayman, S. (2018). Chapter 11: Fostering sustainability in outdoor and informal education. In T. Jeffs & J. Ord (Eds.), Rethinking outdoor and experiential education: Beyond the Confines. Routledge.

Whitehouse, H. (2021). Australia needs a climate change education policy: An absence of responsibility. Australian Education Union Victorian Branch: Professional Voice Journal, 14(2). Retrieved from https://www.aeuvic.asn.au/professional-voice-1422

Williams, S. E., & de la Fuente, A. (2021). Long-term changes in populations of rainforest birds in the Australia Wet Tropics bioregion: A climate-driven biodiversity emergency. PLoS ONE, 16(12), e0254307–e0254307. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254307

Zajchowski, C. A. B., Dustin, D. L., & Hill, E. L. (2021). “The freedom to make mistakes”: Youth, nature, and the Anthropocene. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 24(1), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-021-00076-9

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge that our use of the expression ‘elephant in the room’ in our title was first used in the context of climate change in OEE by Alistair Stewart in Quay et al. (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fox, R., Thomas, G. Is climate change the ‘elephant in the room’ for outdoor environmental education?. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education 26, 167–187 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-022-00119-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-022-00119-9