Abstract

The current study aimed to investigate whether the intensive Certificate in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (CELTA), which certifies teachers of English as a Foreign Language (EFL), is better viewed as a teacher development or a teacher training course. Qualitative content analysis was carried out on the written reflective assignments of CELTA course participants on several courses where the researcher worked as a tutor. The data was subsequently triangulated using semi-structured qualitative interviews. From these data, four main themes emerged as significant: Teacher Learning, General Pedagogic Knowledge, Teaching Skills and Teaching Language, and the Learner Element. A closer analysis of the categories within these themes reveals a tension between a view of teacher development as “training” and a view of teacher development as “education”. To ensure that the course places a greater emphasis on teacher development, CELTA tutors can encourage less focus on the teaching techniques acquired during the course and more focus on the appropriacy of such techniques with particular classes and in certain contexts by redesigning the reflective prompts which form the basis of the written reflection assignment on the course, and by modelling reflective practice throughout the course.

摘要

本研究主旨在調查以密集教導說他國語言者的英語教學能力證照 (CELTA),來核發給教授英語為外語的教師合格證書,此證照是否更被視為一門教師發展或培訓的課程。藉由在以作者為導師身份於此證照(CELTA)課程中,質化內容分析將執行在此課程參加者的書面反思作業上。收集的資料隨後以半結構式的質化訪談來進行三角驗證法。結果研究顯示,從資料分析當中,浮現出四個具有意義重要性的主題:「教師學習、一般教育知識、教學技巧與教學語言、學習者要素」。更進一步分析在這些主題中的分類,其結果顯示在視教師發展的觀點為「培訓」和「教育」之間,存在著緊張關係。為了確保此證照課程更著重在於教師發展,藉由重新設計反思提問機制,來形成書面反思作業的基礎,並在課堂間進行模擬反思訓練,此證照課程的導師鼓勵減少聚焦在課程間教學技巧的獲得,而將更著重在同樣的教學技巧,運用在特定課程或在某些情境中的適當性。

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Akbari, R., Behzadpoor, F., & Dadvand, B. (2010). Development of English language teaching reflection inventory. System, 38, 211–227.

Anderson, J. (2016). Initial teacher training courses and non-native speaker teachers. ELT Journal, 70(3), 261–274.

Bell, J. (2010). Doing your research project: a guide for first time researchers in education, health and social science (5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Berg. (2001). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Borg, M. (2002). Learning to teach: CELTA trainees’ beliefs, experiences and reflection. [online]. Doctoral dissertation, University of Leeds, School of Education. Last accessed 28th November 2018 at: http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/1009/1/uk_bl_ethos_270670.pdf

Borg, S. (2009). Language teacher cognition. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to second language teacher education (pp. 163–171). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Borg, S. (2010). Contemporary themes in language teacher education. Foreign Languages in China, 7(4), 84–89.

Bradford, R. (2004). Can teach, will travel: having a TEFL qualification offers a great chance to work abroad and earn some money. [online]. Daily Telegraph. 1st May. Last accessed 28th November 2018 at:http://www.cactustefl.com/about_us/press/telegraph_010504.php .

Brandt, C. (2006). Integrating feedback and reflection in teacher preparation. ELT Journal, 62(1), 37–46.

Bruster, B. G., & Peterson, B. R. (2013). Using critical incidents in teaching to promote reflective practice. Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 14(2), 170–182.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2005). Research methods in education (5th ed.). London and New York: Routledge Farmer.

Crystal, D. (2006). A global language. In P. Seargeant & J. Swann (Eds.), (2008) English in the world: history, diversity, change (pp. 152–177). London: Routledge.

Ferguson, G., & Donno, S. (2003). One-month teacher training courses: time for a change? ELT Journal, 57(1), 26–33.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hatton, N., & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: towards definition and implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11(1), 33–49.

Hobbs, V. (2007a). Faking it or hating it: can reflective practice be forced? Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 8(3), 405–417.

Hobbs, V.. (2007b). A brief look at the current goals and outcomes of short-term ELT teacher education. [online]. Research News (21), 3–5. Last accessed 28th November 2018 at: http://resig.weebly.com/uploads/8/1/4/0/8140071/issue_21-final.pdf.

Hobbs, V. (2013). “A basic starter pack”: the TESOL certificate as a course in survival. ELT Journal, 67(2), 163–174.

Korthagen, F., Loughran, J., & Russell, T. (2006). Developing fundamental principles for teacher education programs and practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 9(3), 317–326.

Krippendorf, K. (2003). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology, second edition. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Lai, G. (2008). Examining the effects of selected computer-based scaffolds on preservice teachers’ levels of reflection as evidenced in their online journal writing. [online]. Dissertation, Georgia State University. Last accessed 28th November 2018 at: http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/msit_diss/41 .

Lee, H. J. (2005). Understanding and assessing preservice teachers’ reflective thinking. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(6), 699–715.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. In Beverly Hills. Calif: Sage Publications.

Lortie, D. C. (1975). School-teacher: a sociological study. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Mackenzie, L. (2018). Investigating reflection in written assignments on CELTA courses. ELT Journal, ccy037.

Mann, S., & Walsh, S. (2013). RP or ‘RIP’: a critical perspective on reflective practice. Applied Linguistics Review 2013, 4(2), 291–315.

McCabe, M., Walsh, S., Wideman, R., & Winter, E. (2009). The ‘R’ word in teacher education: understanding the teaching and learning of critical reflective practice under construction. [online]. IEJLL: International Electronic Journal for Leadership in Learning, 13(7). Last accessed 28th November 2018 at: http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ940630

Richards, J. C., & Nunan, D. (1990). Second language teacher education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J. C., & Farrell, T. S. C. (2005). Professional development for language teachers: strategies for teacher learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, J. (1998). Language teacher education. London: Arnold.

Stanley, P., & Murray, N. (2013). ‘Qualified?’: a framework for comparing ELT teacher preparation courses. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 36(1), 102–115.

UCLES (2014a). [online]. CELTA Syllabus and Assessment Guidelines. Last accessed 28th November 2018 at: http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/21816-celta-syllbus.pdf

UCLES (2014b). [online]. CELTA End of course performance descriptors. Last accessed 12th February 2018 at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/cfi_resumes/attachments/1283/CELTA_performance_de scriptors_v1_2014.pdf

UCLES (2015). [online]. Cambridge English CELTA Overview. Last accessed 28th November 2018 at: http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/272250-celta-overview.pdf

Van Manen, M. (1977). Linking ways of knowing with ways of being practical. Curriculum Inquiry, 6(3), 205–228.

Wallace, M. J. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: a reflective approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ward, J. R., & McCotter, S. S. (2004). Reflection as a visible outcome for pre-service teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(3), 243–257.

Watkins, P. (2011). A bottom-up view of the needs of prospective teachers. [online]. ELTWorldOnline.com, 3. Last accessed 28th November 2018 at: ELTWorldOnline.com , 3. Retrieved from: http://blog.nus.edu.sg/eltwo/2011/07/24/a-bottom-up-view-of-the-needs-of-prospective-teachers/

Watts, M., & Lawson, M. (2009). Using a meta-analysis activity to make critical reflection explicit in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(5), 609–616.

Yuan, R., & Lee, I. (2014). Pre-service teachers’ changing beliefs in the teaching practicum: three cases in an EFL context. System, 2014, 1–12.

Yuan, E. R. (2016). The dark side of mentoring on pre-service language teachers’ identity formation. Teacher and Teacher Education, 55, 188–197.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to all my research participants, who have all embarked on their own reflective journeys in different contexts and settings, without whom this research would not have been possible. I would like to express thanks to Helen Donaghue for feedback on a draft version of this paper, and her continued support. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose comments significantly improved this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author states that there is no conflict of interest.

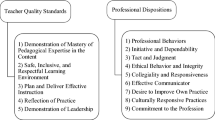

Appendix: Explanation of Themes and Categories From the Qualitative Content Analysis

Appendix: Explanation of Themes and Categories From the Qualitative Content Analysis

Teacher Learning

Robert’s definition of process knowledge as “a set of...skills and attitudes that enable the development of the teacher” (1998, p. 105) was instructive in the development of this theme. It comprises the following sub-categories:

Individual Strengths, Learning, and Weaknesses

This category includes references candidates make to:

-

Their own personal learning and growth

-

Strengths and weaknesses

-

Reflection and self-appraisal

Examples:

“My teaching has changed a lot since the beginning of the CELTA course” [Lily].

“Yes you have the strengths but you need to work on these areas” [Ricky: interview].

Learning from Others

This category includes any references candidates make to learning from:

-

Peers

-

Tutors (including in input and feedback sessions)

-

Other teachers

-

Literature

-

Other sources of information (e.g. from YouTube videos, seminars etc.)

-

Their learners (either TP students or their own students prior to the course)

-

Collaboration with any/all of the above

Examples:

“A peer in my trainee group had planned wonderful activities for her third TP at Intermediate level.” [Ricky].

“I shall also try to utilize the example of fellow trainee <name of trainee>” [Dave].

“I’ve tried to encourage my workmates to introduce peer observations and sometimes I came up against a lack of will to do that” [John: interview].

Difficulties and Challenges on the CELTA

This includes any references the teacher makes to difficulties:

-

Learning the techniques that CELTA teaches and any explanations given for these difficulties (e.g. intensity, duration)

-

Adapting to the style/method of teaching that is expected of them and explanations given for these difficulties (e.g. contradictions in tutor feedback, prior experience)

Examples:

“I wish I could had (sic) had more time to process the huge amount of information that I’ve acquired” [Miki].

“I’ve been told that it was a very intense course but I couldn’t imagine that it would be so demanding” [Miki: interview].

General Pedagogic Knowledge (GPK)

General pedagogic knowledge refers to:

Classroom management skills: a repertoire of language learning activities appropriate to different learning situations; the use of aids; monitoring and feedback; and formal assessment of learning ([30], p. 105).

Following Roberts’s definition, this theme incorporates lesson planning. However, it also comprises the following subcategories:

Managing Tasks

This subcategory covers aspects of classroom management that do not relate to introducing and clarifying language, language practice, and communication. It includes any references to:

-

Setting up tasks

-

Checking understanding

-

Interaction patterns before, during, and after tasks

-

The positioning of the teacher

-

Monitoring and pace

-

Language grading

Some CELTA terminology relating to managing tasks is explained below:

Instruction check questions (ICQs) are given after an instruction to check understanding of the instruction. The simplest example of this is when the teacher sets up a task and asks students “what do you have to do?” Doing examples of tasks and modelling tasks with a stronger student are other ways of making tasks clear. Monitoring involves ensuring learners are on task, and keeping tabs on learners’ progress on tasks. Poor monitoring can affect pace. A lesson has a slow pace when the activities and tasks take too long (for example, because the teacher does not know that students have finished), which can lead to boredom. Information gathered while monitoring is used to inform feedback on tasks. Open class feedback or whole class feedback is conducted after an activity. This is when the teacher provides to the whole class the answers to an activity or task either orally or in written form (if there are clear answers), highlights examples of good and bad language used by students during the task, and/or provides feedback on the actual content of the task by getting students to share what they have discussed. Interaction patterns relates to student groupings and teacher-student interaction. Interaction patterns include open class (all students are listening to the teacher or each other); pair-work, individual work, or group work. Finally, language grading refers to the language the teacher uses to communicate with learners. The CELTA teaches that this should be largely comprehensible and appropriate to the level, particularly when giving instructions [32].

Examples:

“It is important the teacher constantly monitors what students are doing during tasks” [Ricky].

“I also cut down on teacher talking time and managed to increase student talking time” [John: interview].

Planning and Resources

This category covers:

-

Lesson planning

-

Task and materials design and adaptation (resources and activities)

-

Stage and lesson aims

-

Anticipating problems with language

-

Anticipating problems with materials, tasks, skills, and classroom management

-

Suggesting solutions for problems

-

Making assumptions about the learners

Basically, this refers to everything teachers do or think about before the lesson.

Examples:

“I have to work hard on giving students a reason to listen, talk, and write. I have to think about the purpose of every single task before asking students to do an activity” [Lily].

“I will plan better the stages and their connection throughout the class, so they can connect smoothly” [Ricky].

Teaching Skills and Teaching Language

While most lessons integrate both skills and language, CELTA candidates are taught to try and keep these separate in terms of aims and activities. In order to successfully teach language, CELTA trainees must clarify the target language and provide opportunities for language practice ([32]). As for skills, the CELTA typically teaches that these are developed through tasks which focus on specific sub-skills (e.g. reading for gist) and by adequate preparation, appropriate set up, and feedback on such tasks. I have included feedback as an aspect of general pedagogic knowledge (GPK) since it forms a key part of B1: Managing Tasks, but it could also be included under C: Teaching Skills and Teaching Language since feedback is invariably given on either skills-related tasks or language-related tasks.

In terms of teacher knowledge, this category is equivalent to Roberts’ definition of pedagogic content knowledge (PCK) as:

The knowledge of the language we need to teach it. It includes our awareness of what aspects of the target language are more or less problematic for our learners; a personal stock of examples and activities by which to communicate awareness of systems; and a sense of what aspects of the TL system to present now and which to leave for later (1998, p. 105).

It also covers content knowledge (CK), defined by Roberts as, “teachers’ knowledge of target language (TL) systems, their TL competence and their analytic knowledge” (1998, p. 105) since without C4: Content Knowledge, teachers cannot effectively clarify the language they are teaching. This theme also includes this subcategory.

While CK and PCK are treated as different kinds of knowledge by Roberts, both are necessary for the effective teaching of skills and language, and therefore can be said to be aspects of this higher-order theme.

Language practice and communication

This includes any reference to:

-

Productive skills (either written or oral)

-

Interaction or communication in the target language

-

Controlled and freer practice of specific structures

-

Drilling

Drilling is when the teacher says a word, phrase, or sentence which learners then practice saying. This is a way of clarifying the pronunciation of a particular structure or item of lexis but is also a form of controlled practice. Controlled and freer practice are terms used to refer to activities which get students practicing the language in a restricted (controlled) or less restricted (freer) context. These terms relate to the amount of control the teacher has over the language output.

Examples:

“I’m also getting really confident about my drilling” [Miki].

“I still need to work on the way how to exploit the communicational opportunities in the classroom” [Ricky].

Content Knowledge

This includes any references to the teacher’s:

-

Knowledge of or competency in the target language

-

Knowledge of how the language works (their “language awareness”).

The term language awareness is used to refer to CELTA candidates’ knowledge of and proficiency in the target language. For non-expert English speakers language proficiency is an important aspect of content knowledge.

Examples:

“My English level wasn’t that good. I was like in upper intermediate at the time” [Lily: interview].

“I really need to feel comfortable again with grammar” [Miki].

Introducing and Clarifying Language

This includes any references to:

-

The clarification of the target language

-

Techniques used to clarify language such as eliciting, error correcting, or different methods for highlighting or encouraging students to notice something about the target language by use of gestures, tone of voice, fingers, the whiteboard etc.

-

Concept checking (e.g. CCQs)

Concept checking questions (CCQs) are generally considered the most common method of checking understanding on a CELTA. These are questions to check that students have understood the meaning of the target language. For example, “does a wasp make honey?” would check understanding of “wasp”. As mentioned, drilling is a technique for clarifying the pronunciation of the target language but it is also a way of getting learners to practice the language. In either case, it falls under the main theme C: Teaching Skills and Language. For this reason, error correction (which is one aspect of linguistic feedback), although also considered an aspect of classroom management, has also been coded under this theme.

Examples:

“You can take advantage of this moment and take notes of students’ errors and clarify them in the error correction stage” [Lily].

“The correcting of people was something <name of tutor> you two had a very different take on” [Dave: interview].

The Learner Element

This theme concerns “those items that deal with a teacher’s reflecting on his/her students, how they are learning and how learners respond or behave emotionally in their classes” ([1], p. 214). It often entails seeing things from the learner’s perspective. This category incorporates Roberts’ definition of contextual knowledge as an understanding of the learning and teaching context and culture which informs teaching decisions (1998).

Affective Factors

This category refers to emotional factors that influence the classroom dynamic and the learning process. CELTA courses place an emphasis on building rapport with learners. This can be fostered, for example, by talking and listening to students, maintaining eye contact, and smiling. This category covers references to the following:

-

Learner motivation

-

Praising learners

-

The classroom dynamic

-

Learner engagement

-

Establishing and maintaining a good relationship (rapport) with learners

-

Fostering and maintaining a positive learning environment

Examples:

“Not establishing good rapport may lead into a bad development of the class” [Ricky].

“I have a good rapport with the class due to my enthusiasm and sensitivity to students’ needs” [Miki].

The Learning and Teaching Context

This category includes any reference to specific learning and teaching situations and incorporates reference to the following:

-

Learning styles

-

Learners’ and teachers’ culture or learning context

-

Learners’ language learning needs

-

The learners’ level

-

The impact of a specific technique or behaviour on learners

Examples:

“It would benefit them more if I used an open-handed gesture instead of pointing at them directly” [John].

“Students can have a visual-kinaesthetic example of the task they are asked to do” [Ricky].

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mackenzie, L. Teacher Development or Teacher Training? An Exploration of Issues Reflected on by CELTA Candidates. English Teaching & Learning 42, 247–271 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-018-0016-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-018-0016-2