Key summary points

To summarize the literature on medication review and deprescribing in older adults, and formulate recommendations to improve prescribing medications in older, multimorbid adults with polypharmacy.

AbstractSection FindingsCurrent evidence demonstrates a need for a multifaceted and wide-scale change in education, guidelines, research, advocacy, and policy to improve the management of polypharmacy in older people, and to make deprescribing part of routine care for the ageing generations to come.

AbstractSection MessageBy implementing the recommendations in this paper, healthcare professionals will be better prepared to address the challenges associated with an ageing population and provide high-quality care to older patients with complex health and social care needs.

Abstract

Inappropriate polypharmacy is highly prevalent among older adults and presents a significant healthcare concern. Conducting medication reviews and implementing deprescribing strategies in multimorbid older adults with polypharmacy are an inherently complex and challenging task. Recognizing this, the Special Interest Group on Pharmacology of the European Geriatric Medicine Society has compiled evidence on medication review and deprescribing in older adults and has formulated recommendations to enhance appropriate prescribing practices. The current evidence supports the need for a comprehensive and widespread transformation in education, guidelines, research, advocacy, and policy to improve the management of polypharmacy in older individuals. Furthermore, incorporating deprescribing as a routine aspect of care for the ageing population is crucial. We emphasize the importance of involving geriatricians and experts in geriatric pharmacology in driving, and actively participating in this transformative process. By doing so, we can work towards achieving optimal medication use and enhancing the well-being of older adults in the generations to come.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An ageing population means that more people will be living longer, but with multimorbidity [1, 2]. As a consequence, polypharmacy is becoming more prevalent, with two-thirds of adults over 65 years requiring multiple medications to manage their chronic conditions [3, 4]. While appropriate polypharmacy can be beneficial in managing symptoms and prolonging life, there is an increasing prevalence of inappropriate polypharmacy [5, 6]. This occurs when medicines are prescribed without evidence-based indication, are ineffective, or pose a risk for adverse drug reactions (ADRs). Potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) use is highly prevalent, not only in institutional care, but also in community-dwelling older adults [5,6,7,8,9].

There is a growing awareness of the potential harm associated with polypharmacy, especially in older adults [6, 10]. In fact, medication-related harm has recently been identified as a common geriatric syndrome [11]. Negative outcomes can include poor quality of life, drug interactions (drug–drug and drug–disease), poor medication adherence, increased morbidity, hospitalizations, increased length of hospital stay and mortality (drug related and overall), and greater economic burden [1, 6, 12,13,14]. In Europe, around 8.6 million unplanned hospital admissions are caused by ADRs annually, of which 70% are in older patients with polypharmacy [15]. To address this issue, the World Health Organization (WHO) established 'Medication Without Harm' as the third international Global Patient Safety Challenge in 2017 [16]. The initiative aims to raise global awareness about inappropriate prescribing and reduce serious avoidable medication harm by 50% globally within 5 years. In addition, medication safety is an important component of the global “Age-Friendly Health Systems” movement [17], and American recommendations for geriatric care [one of the four Ms (“matters most”) for stands for “Medication”]. There have been many national and regional initiatives aiming to improve safety in patients with polypharmacy, such as the Scottish Polypharmacy Guidance [18], the British CHARMER (CompreHensive geriAtRician-led MEdication Review) [19], and the recently launched SafePolyMed project (www.safepolymed.eu/).

For safe and effective pharmacotherapy in older adults, the medication list should be assessed for both over- and undertreatment and adjusted within the context of an individual patient’s care goals, current level of functioning, life expectancy, values, and preferences [3, 18]. Underprescribing occurs when effective treatments are not initiated despite a valid indication [7, 20], while overprescribing occurs when medications are prescribed without a valid indication or in inappropriate dosage, or interact unfavorably with certain patient conditions or concomitant medications. In practice, both over- and underprescribing are common [7, 20,21,22]. An important part of optimizing pharmacotherapy is deprescribing [23], the process of withdrawal of an inappropriate medication, supervised by a health care professional with the goal of managing polypharmacy and improving outcomes [24, 25]. It is a means to address and mitigate the current or potential harmful effects of inappropriate polypharmacy [24, 25], minimize drug-related harm for older adults, and improve their quality of life [3, 25]. Deprescribing can also reduce geriatric syndromes (such as cognitive decline [26] and falls [27]), pill burden [27,28,29], and the risk of hospitalization and death [27, 30]. On the other hand, deprescribing can also be harmful, as is suggested by studies in which antihypertensives were deprescribed in older patients, showing relevant—but not statistically significant—safety signals with more serious drug events (SAEs) in the intervention groups [31, 32]. This illustrates that deprescribing decisions should be weighed carefully. The recently published special issue of this journal by the European Geriatric Medicine Society (EuGMS) Task and Finish group on Fall Risk Increasing Drugs (FRIDs), “Deprescribing dilemmas in patients at risk of falls” (Volume 14, issue 4, August 2023), contains reviews on rational (de)prescribing of FRIDs.

This position paper, written on behalf of the (EuGMS Special Interest Group (SIG) on Pharmacology, discusses recommendations for the deprescribing component of optimizing pharmacotherapy in older adults with multimorbidity, and the role of healthcare professionals herein, with special focus on the role of geriatricians, and how to manage patient-centered polypharmacy in clinical practice. The paper also provides recommendations for future research efforts and implementation strategies, and reflects on deprescribing policy initiatives. Our recommendations are based on a (non-systematic) review of existing literature and expert knowledge. The expert group consisted of geriatricians, clinical pharmacologists, pharmacists, researchers, and policy makers from eleven countries. The co-authors reached consensus on the recommendations.

Deprescribing in clinical practice

The process of deprescribing

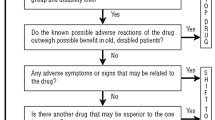

Medication review and deprescribing in older people with multimorbidity are challenging and not performed as frequently as it should [6]. Clinical inertia, possibly due to the difficulty of thoroughly evaluating the benefits and risks of medications in this population, may explain this [33]. While individual medications may be suitable based on guidelines for specific diseases, they may not be appropriate when considering multiple conditions, frailty, or limited life expectancy. However, there is limited evidence on the health benefits and safety of deprescribing for many medications. To make informed and patient-centered (patient priority directed; https://patientprioritiescare.org/) treatment decisions [34,35,36], healthcare providers need to consider the patients’ condition, functional trajectories, life expectancy, treatment risks and benefits, personal goals and preferences, and previous (de)prescribing experiences [35, 37,38,39,40].

The frequency of medication review to assess the safety and effectiveness of older adults' medication regimens is not uniformly recommended. Regular comprehensive evaluations, considering changes in overall health and prognosis, are advisable, particularly for frail individuals [21]. According to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance, medication review should ideally occur every 6 months for frail or cognitively impaired older adults [41]. Detailed medication review and deprescribing should also be considered when new symptoms or conditions arise or when ADRs or advanced/end-stage diseases, severe dementia, extreme frailty, or long-term care facility admissions occur [42]. In medication review, careful attention should be given to patient characteristics, drug–disease interactions, and the efficacy and safety of each treatment before initiating, continuing, or discontinuing medications. Additionally, special attention is necessary for high-risk medication combinations, unnecessary or ineffective medications, and preventive drugs for individuals with frailty or limited life expectancy [43].

Over the last decades, many checklists, online resources (e.g., evidence-based deprescribing guidelines at www.deprescribing.org), and guidelines have been developed to support health care providers in the process of (de)prescribing in older people [6, 44,45,46]. A recent review [47] identified over 70 drug lists, including the Beers Criteria [48], Fit-For-The-Aged (FORTA) [49], the Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions and Screening Tool to Alert to Right Treatment (STOPP/START) [50], and Turkish Inappropriate Medication Use in the Elderly (TIME) [42]. These lists can be classified as either Drug-Oriented Listing Approaches (DOLAs), or Patient-In-Focus Listing Approaches (PILAs) for which knowledge of patient characteristics is required [47]. In randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) [51,52,53], PILAs (e.g., FORTA and STOPP/START) were more beneficial to patients than DOLAs [47], especially if they not only identify overtreatment by PIMs, but also positively label drugs or actions on drugs (e.g., dose adjustment) that may have been omitted [potentially omitted medications (POMs)]. The demonstrated clinical benefits in RCTs suggest that deprescribing by itself is not always sufficient to improve an older patient’s clinical status.

Organizing healthcare systems with focus on deprescribing

Given their expertise and knowledge of older adults with multimorbidity, and age-related alterations in pharmacodynamics and kinetics, geriatricians are in an ideal position to perform medication reviews and optimizing pharmacotherapy (including deprescribing) for this patient population. Thus, geriatricians are urged to take the lead in this area. However, given the large number of older adults involved, geriatrician-led medication reviews cannot be the standard for all and collaboration is warranted. In principle, general practitioners (GPs) should regularly review medications and this should include evaluation of deprescribing opportunities in their older patients. They already are the main prescribers of older adults’ medications [54], have detailed knowledge of their patient’s past and current diagnoses and treatments, are the connection between healthcare providers, and often have a longstanding professional relationship with their patients. The associated level of trust among patients regarding health care professionals’ decisions to change or discontinue (long-term) treatments is considered essential for successful deprescribing attempts [55]. In complex situations where GPs lack confidence or expertise to perform a medication review, and depending on the organization of national healthcare systems, geriatricians, clinical pharmacologists, and/or pharmacists can provide support, or take responsibility for the medication review and represcribing. For effective management of polypharmacy and deprescribing medications, it is recommended to have interprofessional communication on a case-by-case patient level to define the roles and responsibilities between hospital specialists and primary care physicians. Integrating the skills and professional expertise of pharmacists and other healthcare professionals can help to address the medical complexity of older patients [6, 35]. Collaboration among healthcare professionals also allows for shared responsibility and workload associated with deprescribing [10]. Many studies have reported highly effective deprescribing interventions involving pharmacists [7, 56]. Pharmacists are well equipped for tasks such as medication reconciliation, review, patient education, and advising on safer alternative medications. They can also assist in detecting and optimizing adherence [57]. However, deprescribing interventions carried out by pharmacists or physicians may require significant effort, time, and costs, making it challenging to implement in real-world clinical care.

In some countries, nurses can acquire an advanced role as nurse prescribers (also called nurse practitioners), enabling them to play an active role in deprescribing as well, for example in the monitoring phase, by educating and coaching patients and their caregivers and communicating with other healthcare providers [35, 58]. For countries where nurses cannot be actively involved in pharmaceutical care, specialized polypharmacy clinics may be considered [59].

Deprescribing settings and communication between prescribers

Older patients with polypharmacy and multimorbidity often receive care from multiple healthcare professionals in different specialties and settings. Accurate medication reconciliation is crucial for optimal pharmacotherapy [60]. Effective communication of medication changes and management plans among healthcare professionals is essential for safe and effective polypharmacy management in older adults, particularly during care transitions [61, 62]. However, there is currently a lack of uniform pharmacotherapeutic documentation standards in most European Union (EU) countries. Canadian researchers have recently developed templates for deprescribing recommendations between pharmacists and clinicians, with promising results from pilot trials [63].

To facilitate decision-making for all care providers, we propose a minimal set of data to be recorded in patients' medical records, including the indication and planned duration of treatment, rationale for medication initiation or changes, treatment goals, and patient adherence. Standardized documents should be used to communicate medication changes and management plans, incorporating indications/rationales, treatment goals, planned duration, goals of care, patient preferences, tapering regimens, and monitoring plans for deprescribing attempts.

Comprehensive geriatric assessments by geriatricians should routinely include a review of medication appropriateness and patient willingness to deprescribe. However, deprescribing practices may vary depending on settings and available resources. Geriatric day hospitals, outpatient clinics, rehabilitation centers, and long-term care facilities are suitable for proactive medication-related problem identification based on comprehensive assessments [25, 35]. Deprescribing is also recommended during unplanned hospital admissions, particularly if the admission is related to medications. However, the short duration of hospital stays may limit proper evaluation of therapy modifications and patient recovery. Therefore, geriatricians should provide appropriate instructions to patients and include detailed deprescribing information in discharge letters to ensure awareness and appropriate monitoring by GPs and other treating physicians. Experts propose systematic screening of older patients' willingness to deprescribe, similar to falls or depression screening, possibly using tools such as the Patients' Attitudes Towards Deprescribing (PATD) questionnaire [64], which can inform clinicians about patient preferences and facilitate patient-centered decision-making (Table 1).

Organizational factors, implementation, and policy

To facilitate appropriate drug prescribing, country-specific and the most comprehensive up-to-date explicit national criteria of PIMs are required [5]. At present, in some EU countries (e.g., The Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, and Italy), national implicit guidelines for managing polypharmacy and deprescribing have been published. These evidence-based guidelines assist healthcare providers in clinical decision-making and rational deprescribing practices. Efforts should be made to develop such guidelines for countries lacking these. This may result in better patient and policy maker engagement, bringing deprescribing into the routine care dialogue [65]. Also, we advocate the need for more information/guidance on deprescribing in (inter)national “disease-specific” guidelines that so far emphasize medication prescription over deprescribing. Finally, to improve (de)prescribing across Europe, regulatory aspects related to PIM approvals, marketing, and availability should be harmonized and better regulated. At present, there are considerable cross-country differences in approval rates, marketing, recommendations, and preferences for the use of PIMs [5]. Special focus should be on a limited set of high-risk medications [48]. In addition, it is desirable that regulatory agencies [for example the European Medicines Agency (EMA)] prioritize deprescribing, and include recommendations for withdrawing medications, instead of merely recommendations when to start medications.

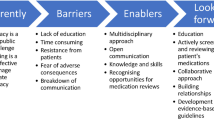

Current healthcare systems are highly fragmented, consisting of numerous disciplines and organizations. There is limited time and resources available for deprescribing [66], and prescribing quality indicators are lacking [67]. These factors, combined with public and healthcare provider-related factors, contribute to the complexity of reducing inappropriate polypharmacy.

Some countries have concluded that a coordinated national action plan is required to make the needed transformation (lown-eliminating-medication-overload-web.pdf (lowninstitute.org). For example, in Australia, over 100 stakeholders collaborated to develop a national strategic action plan for reducing inappropriate polypharmacy in older people and the following items were included: (1a) exploring opportunities to update documents that guide medication use to explicitly include issues of multimorbidity, polypharmacy, and deprescribing; (1b) investigate the inclusion of a mandatory section to the approved product information consumer medication information of all medications titled ‘Cessation’ or ‘Deprescribing’; (2) integrate health care to provide multi-disciplinary patient-centered pharmaceutical care; (3) collect and use health data to monitor and address polypharmacy at the community, health care professional and consumer level; (4) provide incentives to health care professionals for optimizing quality use of medicines by older adults; (5) provide health care professionals with education and tools to optimize quality use of medicines by older patients; (6) raise consumer awareness of polypharmacy and deprescribing and provide tools to help consumers discuss the issues with their prescribers, and (7) develop a national strategic plan for research on polypharmacy and deprescribing [68].

Many older adults are unaware that certain medications may be harmful [69, 70], and that deprescribing inappropriate medications or switching to safer alternatives may be possible. Improving older adults’ health literacy has been shown to be a valuable intervention to reduce the harms associated with inappropriate polypharmacy [20]. Patient and public engagement is essential for managing polypharmacy and deprescribing PIMs. Therefore, public awareness should be increased [69] making deprescribing more common [55, 56, 65, 71]. There have been various large-scale programs aimed to facilitate the deprescribing movement by targeting the public [72]. For example, in the D-PRESCRIBE study [28], brochures about high-risk medications were e-mailed to patients. In addition, the patients’ primary care physician received a document, containing evidence-based rationale and options for stopping medications when appropriate. This intervention resulted in a reduction in sedative use of 43% over 6 months, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of only three. Another example is a regional public awareness campaign in Southern Australia about the benefits and harms of benzodiazepines, and the availability of non-pharmacological alternatives. This initiative produced a 19% reduction over 2 years in benzodiazepine dispensing [73]. Furthermore, receipt of a mailed educational booklet outlining the benefits and harms of chronic benzodiazepine use for insomnia yielded a benzodiazepine discontinuation rate of 27% compared with 5% in the control group 6 months after the intervention [74]. In Europe, enhancing patient empowerment towards safer prescribing is one of the main aims of the recently launched SafePolyMed program (Table 2).

Education and training

Undergraduate training

To meet the challenges and demands of an ageing population, we need to adapt undergraduate education and ensure that all newly qualified doctors are well equipped to care for older patients with complex health and social care needs [75], including managing polypharmacy and deprescribing [76, 77]. At present, teaching polypharmacy and deprescribing are still an evolving topic in undergraduate curricula. Based on experts from the European Union of Medical Specialists-Geriatric Medicine Section (EUMS-GMS) board, the Education SIG of the EuGMS [76], and the International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (IUPHAR), managing polypharmacy, deprescribing and minimizing low-value care (continuation of potentially futile medications associated with ADRs) should receive priority [78].

For effective and personalized pharmacotherapy (including deprescribing), a patient-centered, multi-disciplinary approach, adequate knowledge, attitudes, and communication skills are required, for which students should be adequately trained. First, the learning outcomes of medical students should include recognition of frailty, which is crucial in medication-related decision-making in older individuals [78]. Also, knowledge of deprescribing tools (e.g., Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in Frail Adults with Limited Life Expectancy (STOPPFrail) [79]), age- and frailty-related changing risk management and treatment goals should be taught. Technical knowledge should be provided to facilitate rational and safe pharmacotherapy, including NNT, number needed to harm (NNH), time-to-benefit (TTB), ADRs, optimal tapering strategies, and non-pharmacological treatment options. Competencies for shared decision-making, communication, and managing health systems should be included in the training. Ideally, future doctors should be trained for optimal use of terminology: instead of telling patients they “need” medications for a certain benefit, or telling the medication is “for the rest of their lives”, they should discuss the risks of a medication up-front [55], and consider the use of safer (non-pharmacologic) alternatives. To prevent prescribing cascades (a new medicine is prescribed to 'treat' an adverse reaction to another drug) [80, 81], students should be taught to have a high level of suspicion for new symptoms to be an adverse effect of other medications that were recently initiated in older people with polypharmacy [82].

Future doctors should be taught communication skills to be able to openly discuss current medication adherence, satisfaction, and preferences with their patients, and discuss their willingness to deprescribe [83]. In deprescribing discussions, optimizing therapy and minimizing risk of adverse effects should be emphasized [37]. Also, deprescribing attempts should be framed as a trial, reassuring patients that medication can be re-initiated whenever necessary [84]. The importance of exploring the patients’ willingness to deprescribe should be emphasized, as opposed to assuming that patients may not be willing to deprescribe a longstanding medication [85]. Indeed, literature consistently shows that clinicians (including geriatricians [86]) perceive patients to be unwilling to deprescribe their medications, despite evidence indicating the opposite: the majority of geriatric patients and nursing home residents want to take fewer medicines, and are hypothetically willing to stop a medicine on their clinician’s recommendation [20, 35, 87]. Also, students should be trained to communicate uncertainty with patients: in older adults with multimorbidity, benefits and harms of both prescribing and deprescribing medications are often uncertain, stressing the need for an individualized, holistic approach that is driven by the patients’ goals and preferences for care, and requires clinical judgement [42]. Finally, students should be encouraged to be proactive in reviewing polypharmacy and optimizing medication, especially in geriatric and palliative care patients.

Ideally, education on optimization of pharmacotherapy and deprescribing should include interprofessional educational approach where students from two or more health or social care professions learn interactively together with the aim of providing high-quality, patient-centered care [76]. It is beneficial for students, because it not only expands knowledge, but they also learn about roles and responsibilities, and effective communication as a team [76]. Given their specific knowledge, expertise, and skills, we advocate that experts on geriatric prescribing and/or pharmacotherapy are actively involved in the development of undergraduate educational programs on polypharmacy and deprescribing, not only for medical students, but also for student pharmacists, nurses, and other healthcare professionals.

Geriatricians and geriatricians-in-training often report that they received insufficient education and training in polypharmacy management and deprescribing in medical school [86]. In another study, hospital clinicians reported limited self-efficacy in deprescribing [88]. Recently, European societies have defined a common core curriculum with a list of minimum training requirements for obtaining the specialty title of geriatric medicine [89]. According to that listing [90], geriatric trainees should be able to: “explain the indications and contraindications, mechanism of action, effectiveness, potential adverse effects, potential drug interactions, and alternatives for medications commonly used in older patients. They should also be able to recognize symptoms that could be explained by ADRs and risk factors for increased risk of ADRs. Knowledge of the basic principles of drug-drug interactions, drug-food interactions, and effects of disease states on drug pharmacokinetics is important. Trainees should acquire knowledge on polypharmacy, PIMs, and under- or overuse of the most common drugs in older patients”. In addition, it is stated that “Geriatricians entering into unsupervised practice, in and across all care settings, are able to: provide comprehensive medication review to maximize benefit and minimize number of medications and adverse events”.

Specialized nurses in geriatrics and/or long-term care facilities should be trained for their role in monitoring adverse effects, assessing adherence, and providing non-pharmacological patient education [36] at least in countries where these healthcare professionals are allowed to prescribe medications. Their education should include knowledge on non-pharmacological interventions, for example regarding challenging behavior/behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia [90, 91].

Postgraduate training

International experts in the field of deprescribing recommend education on optimal prescribing and deprescribing continuing from the undergraduate level through to continuing professional development [55]. We recommend that educational material is developed for European geriatricians to increase their knowledge on medication review, polypharmacy, and deprescribing. To this end, a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) could be developed. MOOCs are free-of-charge (“open”) online training courses that can be used to disseminate knowledge and skills to a large amount of individuals (“massive”) [92], as has been successfully done by the “Screening for Chronic Kidney Disease among Older People across Europe” consortium [92].

Given their specific knowledge, expertise, and skills, we advocate that experts on geriatric prescribing and/or pharmacotherapy are actively involved in the development of postgraduate educational programs on polypharmacy and deprescribing, not only for medical doctors, but also for pharmacists and specialized nurses working in the geriatric field (Table 3).

Research

Clinical trials

Frail older individuals are often underrepresented in clinical trials, and functional outcomes are frequently overlooked, particularly in trials involving medications commonly prescribed to this population [93]. This underrepresentation presents a significant barrier to the application of modern epidemiological techniques and the expansion of our knowledge base. To enable healthcare professionals to make informed prescribing decisions for older individuals with multimorbidity and polypharmacy, it is crucial to enhance our evidence base concerning the potential harm and benefits of (de)prescribing medicines in older adults with multimorbidity. This includes investigating metrics such as the NNH, NNT, efficacy of non-pharmacologic alternatives to PIMs [94], and adverse drug withdrawal events (ADWEs). Consequently, prioritizing funding for studies focusing on medications with an overall positive benefit/risk ratio in older adults is essential. Key outcomes to focus on should include patient-centered goal attainment, TTB approaches, and de-escalation trials, particularly within the fields of geriatric oncology and hematology [95]. Ideally, these trials should have longer durations and incorporate baseline functional parameters. Additionally, real-world evidence studies allow for the evaluation of the representativeness of RCT data in real-life patient populations. Furthermore, such studies provide opportunities to generate comparative safety and efficacy data.

Existing tools

A multitude of tools have been developed, and various online resources are available to assist clinicians in achieving appropriate (de)prescribing practices. However, it is recommended to validate, refine, and regularly update these existing tools before considering the development of new ones. Additionally, it is essential to adapt these tools to local settings, taking into account the differences in registered medications and prescribing practices among regions and countries [96].

Deprescribing trials

A growing number of deprescribing trials are being conducted, and recent systematic reviews show an effect in terms of decreased prescribing of PIMs [29, 97]. However, strong evidence for consistent and sustainable changes in clinical outcomes is still lacking. This can be explained by methodological limitations. Scott et al. listed the following items potentially explaining study limitation factors for RCTs, namely: small sample size, short follow-up time, infrequent use of quality-of-life measures, insufficient targeting of patients at highest risk of medication-related harm, suboptimal intensity or duration of deprescribing interventions, and limited use of potentially useful clinical decision support system (CDSS) to assist deprescribing [33]. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has launched a new road map 2030 for drug evaluation in older adults. The road map contains support for deprescribing studies [98]. In contrast, the EMA does not have a comparable agenda and has not reopened the Geriatric Expert Group.

Implementing deprescribing in clinical trials has proven to be challenging. For instance, recent large European trials on medication optimization, such as SENATOR [99] and OPERAM [100], reported disappointing acceptance rates of deprescribing advice. When developing new interventions, it is important to consider and address the barriers and facilitators to deprescribing at various levels, including individuals and the public, healthcare professionals, and the healthcare system [66].

In addition to suboptimal implementation, the low intensity of interventions may partially account for the negative outcomes observed in the majority of deprescribing trials [33]. Relying solely on a single medication review conducted by a pharmacist or physician might not be sufficient. Instead, healthcare professionals and patients require adequate time, interactions, information, and motivation to develop, agree upon, initiate, and monitor deprescribing decisions [33]. For instance, in the OPERAM trial [100], the single review was proposed as one of the explaining factors for negative findings as contacts with other doctors might have led to changes in medication regimens. Naturally, in a busy clinical practice, it is crucial to find the right balance between the feasibility and intensity of the intervention.

In addition, several recommendations were not implemented during the hospital admission as some hospitalized patients first wanted to consult their GP about the medication change recommendations [100]. Moreover, several STOPP/START criteria might not be relevant during acute hospital admission [99]. These examples highlight the importance of the timing of the medication review in future trials and the adjustment of the used tool to the setting [101]. In addition, follow-up duration should be longer to ascertain potential long-term deprescribing effects.

It should be stressed that deprescribing interventions are complex interventions, comprising a number of interactions between components, different stakeholders/users, variable outcomes, and a number of uncertainties. The updated Medical Research Council (MRC) framework can guide the development and evaluation of such interventions [102]. This framework can help design interventions that fit within clinician’s workflow and engage all stakeholders, including patients and professionals in each step (develop or identify intervention, feasibility assessment, evaluation, and implementation). Furthermore, to understand the feasibility and acceptability of different deprescribing interventions, common implementation outcomes should be developed for deprescribing trials [103].

The use of electronic medical records (EMRs) provides an opportunity to develop and utilize CDSSs that could incorporate deprescribing tools. Although the potential to reduce PIM prescribing through EMR-enabled CDSSs has been demonstrated in hospitalized older adults [104], evidence that this translates to improved clinical outcomes is limited. Literature suggests that improvement in clinical outcomes (e.g., reduction in adverse drug reactions) can be achieved if geriatricians are involved in the intervention [105, 106]. In line with this, it should be emphasized that CDSS-based approaches are always part of multicomponent complex interventions. They require careful development of the CDSS in collaboration with the end-users, and adequate integration in the workflow of the clinicians is essential. Also, adequate educational and implementation efforts supported by specific end-user expertise are warranted. Ultimately, CDSSs should be seamlessly integrated into EMRs at the point of care, user-friendly, and responsive to patient contexts to avoid alert fatigue [107].

To date, inconsistent and heterogeneous outcome definitions of deprescribing have been used [103]. To enable comparison and synthesis of trial results, a Core Outcome Set (COS) should be used as these provide a base for robust evidence regarding deprescribing research. COS is a consensus minimum set of standardized outcomes to be used in all trials of a specific field. Currently, COS exists for medication reviews in older people with polypharmacy, for addressing polypharmacy in older people in primary care, and for deprescribing in hospital for older people [19, 108, 109]. Furthermore, a future framework for deprescribing trials should focus on patient-centered outcomes [110].

Non-inferiority designs have been proposed as an alternative to classical superiority analysis. It is important to consider the clinical, financial, and economic aspects that influence deprescribing decisions. Considering the decrease in drug burden and costs, a lack of change in clinical status (e.g., functioning or symptoms) following deprescribing could be considered a positive outcome. Non-inferiority designs can help evaluate whether deprescribing leads to "no change" [111, 112]. Another study design that may be considered for addressing polypharmacy and deprescribing is the n-of-1 trial. N-of-1 trials involve crossover experiments within individual patients, allowing for a comparison of the effects of continuing with the current treatment versus no treatment or placebo [113, 114]. N-of-1 trials are appealing as they generate patient-specific evidence that can inform deprescribing decisions and promote therapeutic precision [114]. Considering the challenges associated with conducting RCTs on deprescribing, the use of observational research using large administrative datasets, such as electronic health records or claims data, could be considered as an additional data source to support the evaluation of specific deprescribing research questions within RCTs [115]. In recent decades, significant advancements have been made in pharmaco-epidemiology and comparative effectiveness research, including the emulation of target trials, active comparator new user designs, and the use of prior event rate ratios or propensity scores, which can be applied to deprescribing research [115]. To employ comparative effectiveness research in the field of deprescribing, rich data for large numbers of individuals are necessary [115]. However, the possibility for unmeasured confounding still exists.

There is a significant knowledge gap regarding the heterogeneous treatment effects of deprescribing, as highlighted by Scott et al. [33]. Individual responses to PIMs and deprescribing can vary due to inter-individual differences, such as age, frailty, and comorbidities. Future research efforts should aim to identify which individuals benefit most from deprescribing and who are most likely to re-initiate medication after deprescribing [33].

To optimize interventions and target individuals at the highest risk of adverse drug events, it is important to consider sex/gender-related pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) differences. Despite women being the largest consumers of medications and facing an increased risk of ADRs compared to men, existing research has largely overlooked this consideration [3]. Therefore, there is a pressing need for more research focusing on the influence of sex and gender on inappropriate prescribing and deprescribing [3] (Table 4).

Conclusion

In summary, the EuGMS SIG on Pharmacology advocates a multifaceted and wide-scale change in education, guidelines, research, advocacy, and policy to improve the management of polypharmacy in older people, and to make deprescribing part of routine care for the ageing generations to come. In our opinion, it is important that geriatricians and experts in geriatric/gerontological pharmacology are in the lead and actively take part in this change.

Abbreviations

- ADR:

-

Adverse drug event

- ADR:

-

Adverse drug reaction

- ADWE:

-

Adverse drug withdrawal event

- CDSS:

-

Clinical decision support system

- COS:

-

Core outcome set

- DOLA:

-

Drug-oriented listing approach

- EMA:

-

European Medicines Agency

- EU:

-

European Union

- EMR:

-

Electronic medical record

- EuGMS:

-

European Geriatric Medicine Society

- EUMS-GMS:

-

European Union of Medical Specialists-Geriatric Medicine Section

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- FORTA:

-

Fit-fOR-The-Aged

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- IUPHAR:

-

International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology

- MOOC:

-

Massive Open Online Course

- MRC:

-

Medical Research Council

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- NNH:

-

Number needed to harm

- NNT:

-

Number needed to treat

- PATD:

-

Patients' Attitudes Towards Deprescribing

- PD:

-

Pharmacodynamic

- PILA:

-

Patient-in-focus listing approach

- PIM:

-

Potentially inappropriate medication

- PK:

-

Pharmacokinetic

- POM:

-

Potentially omitted medication

- RCT:

-

Randomized-controlled trials

- SAE:

-

Serious drug event

- SIG:

-

Special Interest Group

- STOPPFrail:

-

Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in Frail Adults with Limited Life Expectancy

- STOPP/START:

-

Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions and Screening Tool to Alert to Right Treatment

- TIME:

-

Turkish Inappropriate Medication Use in the Elderly

- TTB:

-

Time-to-benefit

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, Naganathan V, Waite L, Seibel MJ et al (2012) Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 65(9):989–995

Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE (2017) What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2

Rochon PA, Petrovic M, Cherubini A, Onder G, O’Mahony D, Sternberg SA et al (2021) Polypharmacy, inappropriate prescribing, and deprescribing in older people: through a sex and gender lens. Lancet Healthy Longev 2(5):e290–e300

Pazan F, Wehling M (2021) Polypharmacy in older adults: a narrative review of definitions, epidemiology and consequences. Eur Geriatr Med 12(3):443–452

Fialova D, Brkic J, Laffon B, Reissigova J, Gresakova S, Dogan S et al (2019) Applicability of EU(7)-PIM criteria in cross-national studies in European countries. Ther Adv Drug Saf. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098619854014

Petrovic M, O’Mahony D, Cherubini A (2022) Inappropriate prescribing: hazards and solutions. Age Ageing. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab269

Steinman MA, Landefeld CS (2018) Overcoming inertia to improve medication use and deprescribing. JAMA 320(18):1867–1869

Mucalo I, Hadziabdic MO, Brajkovic A, Lukic S, Maric P, Marinovic I et al (2017) Potentially inappropriate medicines in elderly hospitalised patients according to the EU(7)-PIM list, STOPP version 2 criteria and comprehensive protocol. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 73(8):991–999

Bahat G, Bay I, Tufan A, Tufan F, Kilic C, Karan MA (2017) Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing among older adults: a comparison of the Beers 2012 and Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions criteria version 2. Geriatr Gerontol Int 17(9):1245–1251

Reeve J, Maden M, Hill R, Turk A, Mahtani K, Wong G et al (2022) Deprescribing medicines in older people living with multimorbidity and polypharmacy: the TAILOR evidence synthesis. Health Technol Assess 26(32):1–148

Stevenson JM, Davies JG, Martin FC (2020) Medication-related harm: a geriatric syndrome. Age Ageing 49(1):7–11

Bulow C, Clausen SS, Lundh A, Christensen M (2023) Medication review in hospitalised patients to reduce morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1(1):CD008986

Kwak MJ, Chang M, Chiadika S, Aguilar D, Avritscher E, Deshmukh A et al (2022) Healthcare expenditure associated with polypharmacy in older adults with cardiovascular diseases. Am J Cardiol 169:156–158

Black CD, Thavorn K, Coyle D, Bjerre LM (2020) The health system costs of potentially inappropriate prescribing: a population-based, retrospective cohort study using linked health administrative databases in Ontario, Canada. Pharmacoecon Open 4(1):27–36

Mair A. Polypharmacy management by 2030: a patient safety challenge. http://www.simpathy.eu/resources/publications/simpathy-project-reference-book2017

Organization WH (2017) The third WHO global patient safety challenge: medication without harm. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIS-SDS-2017.6

https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/default.aspx.

Scottish Government Model of Care Polypharmacy Working Group (2015) Polypharmacy guidance, 2nd edn. Scottish Government, Edinburgh

Martin-Kerry J, Taylor J, Scott S, Patel M, Wright D, Clark A et al (2022) Developing a core outcome set for hospital deprescribing trials for older people under the care of a geriatrician. Age Ageing. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac241

Jansen J, Naganathan V, Carter SM, McLachlan AJ, Nickel B, Irwig L et al (2016) Too much medicine in older people? Deprescribing through shared decision making. BMJ 353:i2893

Duong MH, McLachlan AJ, Bennett AA, Jokanovic N, Le Couteur DG, Baysari MT et al (2021) Iterative development of clinician guides to support deprescribing decisions and communication for older patients in hospital: a novel methodology. Drug Aging 38(1):75–87

Lombardi F, Paoletti L, Carrieri B, Dell’Aquila G, Fedecostante M, Di Muzio M et al (2021) Underprescription of medications in older adults: causes, consequences and solutions—a narrative review. Eur Geriatr Med 12(3):453–462

Pereira A, Verissimo M (2022) Deprescribing in older adults: time has come. Eur Geriatr Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-022-00716-3

Reeve E, Gnjidic D, Long J, Hilmer S (2015) A systematic review of the emerging definition of “deprescribing” with network analysis: implications for future research and clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol 80(6):1254–1268

Reeve E, Thompson W, Farrell B (2017) Deprescribing: a narrative review of the evidence and practical recommendations for recognizing opportunities and taking action. Eur J Intern Med 38:3–11

Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, Le Couteur DG (2008) Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older a systematic review. Drug Aging 25(12):1021–1031

Kua CH, Mak VSL, Huey Lee SW (2019) Health outcomes of deprescribing interventions among older residents in nursing homes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 20(3):362-372.e11

Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A, Ahmed S, Tannenbaum C (2018) Effect of a pharmacist-led educational intervention on inappropriate medication prescriptions in older adults: the D-PRESCRIBE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 320(18):1889–1898

Bloomfield HE, Greer N, Linsky AM, Bolduc J, Naidl T, Vardeny O et al (2020) Deprescribing for community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 35(11):3323–3332

Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, Schwartz D, Etherton-Beer CD (2016) The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 82(3):583–623

Bogaerts J, Gussekloo J, De Jong-Schmit B, Achterberg W, Poortvliet R (2022) The Danton study—discontinuation of antihypertensive treatment in older people with dementia living in a nursing home: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Hypertens 40(Suppl):E1

Sheppard JP, Burt J, Lown M, Temple E, Lowe R, Fraser R et al (2020) Effect of antihypertensive medication reduction vs usual care on short-term blood pressure control in patients with hypertension aged 80 years and older: the OPTIMISE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 323(20):2039–2051

Scott IA, Reeve E, Hilmer SN (2022) Establishing the worth of deprescribing inappropriate medications: are we there yet? Med J Aust. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.51686

Mair A, Wilson M, Dreischulte T (2020) Addressing the challenge of polypharmacy. Annu Rev Pharmacol 60:661–681

Kalim RA, Cunningham CJ, Ryder SA, McMahon NM (2022) Deprescribing medications that increase the risk of falls in older people: exploring doctors’ perspectives using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF). Drug Aging. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-022-00985-4

Lee JW, Boyd CM, Leff B, Green A, Hornstein E, LaFave S et al (2022) Tailoring a home-based, multidisciplinary deprescribing intervention through clinicians and community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.18186

Green AR, Aschmann H, Boyd CM, Schoenborn N (2021) Assessment of patient-preferred language to achieve goal-aligned deprescribing in older adults. JAMA Netw Open 4(4):e212633

Thompson W, Jarbol D, Nielsen JB, Haastrup P, Pedersen LB (2022) GP preferences for discussing statin deprescribing: a discrete choice experiment. Fam Pract 39(1):26–31

Fajardo MA, Weir KR, Bonner C, Gnjidic D, Jansen J (2019) Availability and readability of patient education materials for deprescribing: an environmental scan. Br J Clin Pharmacol 85(7):1396–1406

Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD (2014) Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmacol 78(4):738–747

NICE. Medicines management in care homes. Quality standard [QS85]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs85

Mangin D, Bahat G, Golomb BA, Mallery LH, Moorhouse P, Onder G et al (2018) International Group for Reducing Inappropriate Medication Use & Polypharmacy (IGRIMUP): position statement and 10 recommendations for action. Drug Aging 35(7):575–587

Odden MC, Lee SJ, Steinman MA, Rubinsky AD, Graham L, Jing B et al (2021) Deprescribing blood pressure treatment in long-term care residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 22(12):2540-2546.e2

van Merendonk LN, Crul M (2022) Deprescribing in palliative patients with cancer: a concise review of tools and guidelines. Support Care Cancer 30(4):2933–2943

Thompson W, Lundby C, Graabaek T, Nielsen DS, Ryg J, Sondergaard J et al (2019) Tools for deprescribing in frail older persons and those with limited life expectancy: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 67(1):172–180

Seppala LJ, Petrovic M, Ryg J, Bahat G, Topinkova E, Szczerbinska K et al (2021) STOPPFall (Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in older adults with high fall risk): a Delphi study by the EuGMS Task and Finish Group on Fall-Risk-Increasing Drugs. Age Ageing 50(4):1189–1199

Pazan F, Kather J, Wehling M (2019) A systematic review and novel classification of listing tools to improve medication in older people. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 75(5):619–625

By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert P (2023) American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria(R) for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 67:674–694

Pazan F, Weiss C, Wehling M, Forta (2022) The FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) list 2021: fourth version of a validated clinical aid for improved pharmacotherapy in older adults. Drug Aging 39(6):485

O’Mahony D, Cherubini A, Guiteras AR, Denkinger M, Beuscart JB, Onder G et al (2023) STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 3. Eur Geriatr Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-023-00777-y

Wehling M, Burkhardt H, Kuhn-Thiel A, Pazan F, Throm C, Weiss C et al (2016) VALFORTA: a randomised trial to validate the FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) classification. Age Ageing 45(2):262–267

Frankenthal D, Lerman Y, Kalendaryev E, Lerman Y (2014) Intervention with the screening tool of older persons potentially inappropriate prescriptions/screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment criteria in elderly residents of a chronic geriatric facility: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 62(9):1658–1665

Garcia-Gollarte F, Baleriola-Julvez J, Ferrero-Lopez I, Cuenllas-Diaz A, Cruz-Jentoft AJ (2014) an educational intervention on drug use in nursing homes improves health outcomes resource utilization and reduces inappropriate drug prescription. J Am Med Dir Assoc 15(12):885–891

Pottegard (2022) Who prescribes drugs to patients: a Danish register-based study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 88(3):1398

Raman-Wilms L, Farrell B, Sadowski C, Austin Z (2019) Deprescribing: an educational imperative. Res Soc Adm Pharm 15(6):790–795

Sloane PD, Zimmerman S (2018) Deprescribing in geriatric medicine: challenges and opportunities. J Am Med Dir Assoc 19(11):919–922

Turner JP, Sanyal C, Martin P, Tannenbaum C (2021) Economic evaluation of sedative deprescribing in older adults by community pharmacists. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 76(6):1061–1067

De Baetselier E, Van Rompaey B, Batalha LM, Bergqvist M, Czarkowska-Paczek B, De Santis A et al (2020) EUPRON: nurses’ practice in interprofessional pharmaceutical care in Europe. A cross-sectional survey in 17 countries. BMJ Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036269

Bennett F, Shah N, Offord R, Ferner R, Sofat R (2020) Establishing a service to tackle problematic polypharmacy. Future Healthc J 7(3):208–211

Redmond P, Grimes TC, McDonnell R, Boland F, Hughes C, Fahey T (2018) Impact of medication reconciliation for improving transitions of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8(8):CD010791

Christensen M, Lundh A (2016) Medication review in hospitalised patients to reduce morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008986.pub3

Boockvar K, Fishman E, Kyriacou CK, Monias A, Gavi S, Cortes T (2004) Adverse events due to discontinuations in drug use and dose changes in patients transferred between acute and long-term care facilities. Arch Intern Med 164(5):545–550

Martin P, Tannenbaum C (2018) A prototype for evidence-based pharmaceutical opinions to promote physician-pharmacist communication around deprescribing. Can Pharm J 151(2):133–141

Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD (2013) Development and validation of the patients’ attitudes towards deprescribing (PATD) questionnaire. Int J Clin Pharm 35(1):51–56

Farrell B, Conklin J, Dolovich L, Irving H, Maclure M, McCarthy L et al (2019) Deprescribing guidelines: an international symposium on development, implementation, research and health professional education. Res Soc Adm Pharm 15(6):780–789

Sawan M, Reeve E, Turner J, Todd A, Steinman MA, Petrovic M et al (2020) A systems approach to identifying the challenges of implementing deprescribing in older adults across different health care settings and countries: a narrative review. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 13(3):233–245

Renom-Guiteras A, Meyer G, Thurmann PA (2015) The EU(7)-PIM list: a list of potentially inappropriate medications for older people consented by experts from seven European countries. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 71(7):861–875

O’Donnell LK, Reeve E, Cumming A, Scott IA, Hilmer SN (2021) Development and dissemination of the national strategic action plan for reducing inappropriate polypharmacy in older Australians. Intern Med J 51(1):111–115

Achterhof AB, Rozsnyai Z, Reeve E, Jungo KT, Floriani C, Poortvliet RKE et al (2020) Potentially inappropriate medication and attitudes of older adults towards deprescribing. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240463

Gemmeke M, Koster ES, Janatgol O, Taxis K, Bouvy ML (2022) Pharmacy fall prevention services for the community-dwelling elderly: patient engagement and expectations. Health Soc Care Community 30(4):1450–1461

Scott IA, Le Couteur DG (2015) Physicians need to take the lead in deprescribing. Intern Med J 45(3):352–356

Turner JP, Currie J, Trimble J, Tannenbaum C (2018) Strategies to promote public engagement around deprescribing. Ther Adv Drug Saf 9(11):653–665

Dollman WB, LeBlanc VT, Stevens L, O’Connor PJ, Roughead EE, Gilbert AL (2005) Achieving a sustained reduction in benzodiazepine use through implementation of an area-wide multi-strategic approach. J Clin Pharm Ther 30(5):425–432

Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A, Ahmed S (2014) Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med 174(6):890–898

Masud T, Blundell A, Gordon AL, Mulpeter K, Roller R, Singler K et al (2014) European undergraduate curriculum in geriatric medicine developed using an international modified Delphi technique. Age Ageing 43(5):695–702

Masud T, Ogliari G, Lunt E, Blundell A, Gordon AL, Roller-Wirnsberger R et al (2022) A scoping review of the changing landscape of geriatric medicine in undergraduate medical education: curricula, topics and teaching methods. Eur Geriatr Med 13(3):513–528

Pearson GME, Winter R, Blundell A, Masud T, Gough J, Gordon AL et al (2023) Updating the British Geriatrics Society recommended undergraduate curriculum in geriatric medicine: a curriculum mapping and nominal group technique study. Age Ageing. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac325

Liau SJ, Lalic S, Sluggett JK, Cesari M, Onder G, Vetrano DL et al (2021) Medication management in frail older people: consensus principles for clinical practice, research, and education. J Am Med Dir Assoc 22(1):43–49

Lavan A, Gallagher P, Parsons C, O’Mahony D (2016) Stoppfrail (screening tool of older persons prescriptions in frail adults with limited life expectancy): consensus validation. Age Ageing 45:3

Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH (2017) The prescribing cascade revisited. Lancet 389(10081):1778–1780

Elbeddini A, Sawhney M, Tayefehchamani Y, Yilmaz Z, Elshahawi A, Villegas JJ et al (2021) Deprescribing for all: a narrative review identifying inappropriate polypharmacy for all ages in hospital settings. BMJ Open Qual. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2021-001509

Zazzara MB, Palmer K, Vetrano DL, Carfi A, Graziano O (2021) Adverse drug reactions in older adults: a narrative review of the literature. Eur Geriatr Med 12(3):463–473

Reeve E, Low LF, Hilmer SN (2019) Attitudes of older adults and caregivers in Australia toward deprescribing. J Am Geriatr Soc 67(6):1204–1210

Turner JP, Edwards S, Stanners M, Shakib S, Bell JS (2016) What factors are important for deprescribing in Australian long-term care facilities? Perspectives of residents and health professionals. BMJ Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009781

Gray SL, Fornaro R, Turner J, Boudreau DM, Wellman R, Tannenbaum C et al (2022) Provider knowledge, beliefs, and self-efficacy to deprescribe opioids and sedative-hypnotics. J Am Geriatr Soc. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.18202

van Poelgeest EP, Seppala LJ, Lee JM, Bahat G, Ilhan B, Lavan AH et al (2022) Deprescribing practices, habits and attitudes of geriatricians and geriatricians-in-training across Europe: a large web-based survey. Eur Geriatr Med 13(6):1455–1466

Lundby C, Glans P, Simonsen T, Sondergaard J, Ryg J, Lauridsen HH et al (2021) Attitudes towards deprescribing: the perspectives of geriatric patients and nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 69(6):1508–1518

Ng B, Duong M, Lo SR, Le Couteur D, Hilmer S (2021) Deprescribing perceptions and practice reported by multidisciplinary hospital clinicians after, and by medical students before and after, viewing an e-learning module. Res Soc Adm Pharm 17(11):1997–2005

Stuck AE, Masud T (2022) Health care for older adults in Europe: how has it evolved and what are the challenges? Age Ageing. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac287

Sawan MJ, Moga DC, Ma MGJ, Ng JC, Johnell K, Gnjidic D (2021) The value of deprescribing in older adults with dementia: a narrative review. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 14(11):1367–1382

Harrison SL, Cations M, Jessop T, Hilmer SN, Sawan M, Brodaty H (2019) Approaches to deprescribing psychotropic medications for changed behaviours in long-term care residents living with dementia. Drug Aging 36(2):125–136

Roller-Wirnsberger R, Zitta S, Herzog C, Dornan H, Lindner S, Rehatschek H et al (2019) Massive open online courses (MOOCs) for long-distance education in geriatric medicine across Europe A pilot project launched by the consortium of the project “Screening for Chronic Kidney Disease among Older People”: SCOPE project. Eur Geriatr Med 10(6):989–994

van Marum RJ (2020) Underrepresentation of the elderly in clinical trials, time for action. Br J Clin Pharmacol 86(10):2014–2016

Abraha I, Cruz-Jentoft A, Soiza RL, O’Mahony D, Cherubini A (2015) Evidence of and recommendations for non-pharmacological interventions for common geriatric conditions: the SENATOR-ONTOP systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007488

Sedrak MS, Freedman RA, Cohen HJ, Muss HB, Jatoi A, Klepin HD et al (2021) Older adult participation in cancer clinical trials: a systematic review of barriers and interventions. CA Cancer J Clin 71(1):78–92

Bahat G, Ilhan B, Erdogan T, Halil M, Savas S, Ulger Z et al (2020) Turkish inappropriate medication use in the elderly (TIME) criteria to improve prescribing in older adults: TIME-to-STOP/TIME-to-START. Eur Geriatr Med 11(3):491–498

Thillainadesan J, Gnjidic D, Green S, Hilmer SN (2018) Impact of deprescribing interventions in older hospitalised patients on prescribing and clinical outcomes: a systematic review of randomised trials. Drugs Aging 35(4):303–319

Liu Q, Schwartz JB, Slattum PW, Lau SWJ, Guinn D, Madabushi R et al (2022) Roadmap to 2030 for drug evaluation in older adults. Clin Pharmacol Ther 112(2):210–223

O’Mahony D, Gudmundsson A, Soiza RL, Petrovic M, Jose Cruz-Jentoft A, Cherubini A et al (2020) Prevention of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized older patients with multi-morbidity and polypharmacy: the SENATOR* randomized controlled clinical trial. Age Ageing 49(4):605–614

Blum MR, Sallevelt B, Spinewine A, O’Mahony D, Moutzouri E, Feller M et al (2021) Optimizing therapy to prevent avoidable hospital admissions in multimorbid older adults (OPERAM): cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 374:n1585

Sallevelt B, Egberts TCG, Huibers CJA, Ietswaart J, Drenth-van Maanen AC, Jennings E et al (2022) Detectability of medication errors with a STOPP/START-based medication review in older people prior to a potentially preventable drug-related hospital admission. Drug Saf 45(12):1501–1516

Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM et al (2021) A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061

Bayliss EA, Albers K, Gleason K, Pieper LE, Boyd CM, Campbell NL et al (2022) Recommendations for outcome measurement for deprescribing intervention studies. J Am Geriatr Soc 70(9):2487–2497

McDonald EG, Wu PE, Rashidi B, Wilson MG, Bortolussi-Courval E, Atique A et al (2022) The MedSafer study-electronic decision support for deprescribing in hospitalized older adults a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 182(3):265–273

Schmader KE, Hanlon JT, Pieper CF, Sloane R, Ruby CM, Twersky J et al (2004) Effects of geriatric evaluation and management on adverse drug reactions and suboptimal prescribing in the frail elderly. Am J Med 116(6):394–401

O’Connor MN, O’Sullivan D, Gallagher PF, Eustace J, Byrne S, O’Mahony D (2016) Prevention of hospital-acquired adverse drug reactions in older people using screening tool of older persons’ prescriptions and screening tool to alert to right treatment criteria: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 64(8):1558–1566

Scott IA, Pillans PI, Barras M, Morris C (2018) Using EMR-enabled computerized decision support systems to reduce prescribing of potentially inappropriate medications: a narrative review. Ther Adv Drug Saf 9(9):559–573

Beuscart JB, Knol W, Cullinan S, Schneider C, Dalleur O, Boland B et al (2018) International core outcome set for clinical trials of medication review in multi-morbid older patients with polypharmacy. BMC Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1007-9

Rankin A, Cadogan CA, Ryan C, Clyne B, Smith SM, Hughes CM (2018) Core outcome set for trials aimed at improving the appropriateness of polypharmacy in older people in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc 66(6):1206–1212

Clough AJ, Hilmer SN, Kouladjian-O’Donnell L, Naismith SL, Gnjidic D (2019) Health professionals’ and researchers’ opinions on conducting clinical deprescribing trials. Pharmacol Res Perspect 7(3):e00476

Gnjidic D, Johansson M, Meng DM, Farrell B, Langford A, Reeve E (2022) Achieving sustainable healthcare through deprescribing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.ED000159

Weiskopf RB, Cook RJ (2017) Understanding non-inferiority trials and tests for the non-statistician: when to use them and how to interpret them. Transfusion 57(2):240–243

Goyal P, Safford MM, Hilmer SN, Steinman MA, Matlock DD, Maurer MS et al (2022) N-of-1 trials to facilitate evidence-based deprescribing: rationale and case study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 88(10):4460–4473

Clough AJ, Hilmer SN, Naismith SL, Kardell LD, Gnjidic D (2018) N-of-1 trials for assessing the effects of deprescribing medications on short-term clinical outcomes in older adults: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 93:112–119

Moriarty F, Thompson W, Boland F (2022) Methods for evaluating the benefit and harms of deprescribing in observational research using routinely collected data. Res Soc Adm Pharm 18(2):2269–2275

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support was received for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Poelgeest, E., Seppala, L., Bahat, G. et al. Optimizing pharmacotherapy and deprescribing strategies in older adults living with multimorbidity and polypharmacy: EuGMS SIG on pharmacology position paper. Eur Geriatr Med 14, 1195–1209 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-023-00872-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-023-00872-0