Key summary points

To study the readmission rates and predictors of readmission following hip fracture surgery in a tertiary care centre with the very short postoperative length of stay.

AbstractSection FindingsPostoperative length of stay of only 1–2 days did not increase the risk of readmissions. Delay to surgery, prolonged length of stay, not receiving orthogeriatric contribution and discharge to primary rather than secondary care were associated higher readmission rate and/or mortality.

AbstractSection MessageAlthough a very short stay in the operating hospital appears safe, hip fracture patients should not be discharged to primary care wards with insufficient resources for managing the acute postoperative phase.

Abstract

Purpose

Readmissions are common and complicate recovery after hip fracture. The objective of this study was to study readmission rates, factors associated with readmissions and effects of orthogeriatric liaison service in a setting where patients are discharged typically on the first postoperative day from the operating tertiary care hospital to lower-level health care units.

Methods

A regionally representative cohort of 763 surgically treated hip fracture patients aged ≥ 50 years was included in this retrospective study, based on hospital discharge records. Primary outcome was a 30-day readmission, while the secondary outcome was a composite outcome, defined as readmission or death with a follow-up of 1 year at maximum.

Results

The 30-day readmission rate was 8.3% and 1-year mortality was 22.1%. Short length of stay did not lead to poorer outcomes. Delay from admission to surgery of ≥ 4 days and discharge to primary health care wards were associated with an increased 30-day readmission rate. Age ≥ 90 years, delay to surgery, postoperative length of stay of ≥ 2 days and discharge on a Saturday were associated with higher risk for the composite outcome. Use of orthogeriatric liaison service at the operating hospital was associated with a lower risk of 30-day readmissions (11.8% vs. 6.2%, P = 0.012) whereas in longer follow-up readmissions seemed to cumulate similarly independent of orthogeriatric contribution. Patients living in the largest community in the area were discharged to a secondary care orthogeriatric ward and had a lower risk of 30-day readmissions than other patients (4.8% vs. 10.2%, P = 0.009).

Conclusion

Use of orthogeriatric liaison service and later care at secondary care orthogeriatric ward seem to be beneficial for hip fracture patients in terms of reducing readmissions and mortality. Of the other care-related factors, short delay from admission to surgery and short total length of stay in the operating hospital was also associated with these outcomes, which, however, may relate to the effects of patient characteristics rather than the care process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hip fractures are a common and costly injury worldwide [1]. In older patients, hip fractures have also been associated with increased morbidity [2] and increased health care costs [3], and increased mortality [4, 5]. From patients’ point of view, hip fracture often leads to decline in quality of life and functional ability and consequently there’s an increased need for assistance in daily living and many patients move to more assisted living environments [6, 7]. To avoid these adverse consequences, undelayed surgery, rapid mobilization and avoiding complications are essential [8,9,10,11]. Multidisciplinary orthogeriatric care improves the outcomes [12,13,14,15] but the arrangement of such services as well as access to such care vary between countries and regions.

A certain proportion of hip fracture patients are admitted back to hospital after the initial discharge from the operating unit. Such readmissions are harmful and, if possible, should be avoided, as they complicate and often prolong the recovery. Furthermore, in a US study the 1-year mortality for patients readmitted within 30 days was 56%, compared to 22% for those not readmitted [16].

In previous studies, the 30-day readmission rate has varied between 9 and 12% [16,17,18,19,20]. According to these studies, medical conditions cause readmissions more often than surgical reasons (90% vs. 7%, respectively) [20]. Pneumonia has been the most common single risk factor to cause readmissions in various studies [17, 18, 20]. Additionally, there is evidence that a pulmonary disease is a significant risk factor for future readmissions following a hip fracture [17, 20]. Also, a higher anesthesiologic risk score decreased functional ability, longer length of stay (LOS) and older age have been associated with a higher rate of readmissions [17, 18, 20, 21].

In Finland, hip fracture patients’ readmissions have been studied in a nationwide benchmarking project of the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. According to this register-based surveillance, among hip fracture patients operated in 2010–2016, 30-day readmissions occurred in 8.3–16.6% of cases and 30-day mortality was 3.6–7.9%, differing greatly between hospital districts [22]. These numbers suggest that the way how the treatment is arranged might influence hip fracture patients’ risk of readmission and death. A coordinated orthogeriatrics care model has previously been associated with a significant decrease in time to surgery, LOS, postoperative mortality rates and postoperative readmissions, and altogether every sixth readmission might be preventable by comprehensive treatment [23,24,25]. However, in previous studies the length of orthogeriatric intervention has ranged from days to weeks, whereas in our tertiary care center the LOS is only 1–2 days after which the patients are discharged to an orthogeriatric secondary care ward or to primary health care wards. There are some data concerning fast track hip fracture care with short postoperative hospitalization [26] but its effect on readmissions and value of geriatric contribution in the operating unit are unclear.

The objective of this study is to answer the following questions:

-

1.

What percentage of patients are readmitted to the operating unit, how quickly their readmissions occurred, and what caused these readmissions?

-

2.

Is short LOS (2 days or less) associated with an increased number of readmissions or deaths?

-

3.

Does the risk of readmission or death vary according to the use of orthogeriatric liaison service?

Methods

Study population

This retrospective cohort study is based on electronic hospital discharge records gathered from Tampere University Hospital (TAUH), Tampere, Finland (population base ca. 530,000, 9% of which aged ≥ 75 years). The final study population comprised 763 patients aged ≥ 50 years who suffered a hip fracture (ICD-10 code S72.0, S72.1 or S72.2), were admitted between January 1, 2017 and June 30, 2018 and underwent hip fracture surgery (operation codes NFB10, NFB20, NFJ50, NFJ52 or NFJ54, according to Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee Classification of Surgical Procedures). Patients whose hip fracture was treated with total hip replacement were not included because they were operated in a separate hospital for joint replacement. The follow-up time ended on December 31, 2018 so every patient was observed for at least 6 months from discharge. The maximum follow-up was, however, set to 1 year.

Orthogeriatric liaison service has been utilized in TAUH starting March 6, 2017, meaning that a geriatrician and a geriatric nurse participate in the treatment at orthopedic wards immediately after admission caused by a hip fracture. The geriatric team examines the patient’s background, screens for cognitive disorders, delirium, malnutrition, and frailty, performs clinical examination to identify comorbid acute conditions, and checks the medication list. Typical interventions include changes in medication (e.g., excess antihypertensive agents or diuretics, potentially inappropriate medications), prescription of energy-rich meals and protein supplements, advice and, if necessary, medications for the management of delirium. Geriatrician’s notes, including also recommendations for rehabilitation and possible memory testing or other examinations, are sent with the patient to the next treating unit (Fig. 1). This is of importance because only half of the communities in the district have geriatric services that contribute to care of hip fracture patients. Residents of the largest community in the area were discharged to a secondary care hospital with an orthogeriatric ward, 24/7 on-call physician and laboratory services on all weekdays. Residents of other communities were typically treated in primary health care wards lacking such services. Patients who were treated during the time periods when geriatric team was present (March 6, 2017 onwards, excluding vacation periods) were considered to have received orthogeriatric care by orthogeriatric liaison service.

Data collection

The following data were extracted from mandatory electronic hospital discharge records: age, sex, municipality, date of admission, diagnoses, type of surgery, date of discharge, discharge destination and date of death. Data about readmissions were gathered by searching the electronic hospital discharge records for new hospital admissions, using patients’ unique social security numbers. A new admission was recognized as readmission, if the place of treatment was TAUH or the adjacent secondary care unit and the patient had been admitted within 365 days from discharge. Readmissions to the emergency department only (without following hospitalization) were excluded.

Statistical analyses

The primary outcome in this study was a 30-day readmission, while the secondary outcome was a composite outcome, defined as a readmission or death with a follow-up time of 1 year at maximum. Incidence of readmissions was portrayed using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Factors predisposing for 30-day readmissions were analyzed using cross-tabulation. The differences were first tested using Pearson’s χ2 test, and then using logistic regression with adjustment for age, gender and type of fracture. Factors associated with the composite outcome were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards models both in univariate analysis and with the above-mentioned adjustments. The results of regression analyses are reported as odds ratios (OR) and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals. Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS for Windows, version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York).

Results

Data on 763 hip fracture patients were available (Table 1). Of the patients, 7 (0.9%) died during acute hospitalization and were excluded from further analyses.

The 30-day readmission rate was 8.3% and varied between 0% and 18.4% between months. 58 (7.6%) patients died within 1 month from discharge. 1-year mortality was 22.1% and varied between 16.3% and 39.0% between the observation months. During the first postoperative year, the composite outcome (readmission or death) occurred in 363 cases (48.0%). 26% of all readmissions (63/245) and 31% (51/167) of all deaths occurred during the first postoperative month. The median times to readmission and death were 97 (range 1–359) and 69 (range 1–362) days, respectively.

The most common reasons for readmission were pneumonia (n = 14, 5.7%), cardiac failure (n = 12, 4.9%) and acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (n = 8, 3.3%), followed by weakness and fatigue (n = 6, 2.4%), cerebral infarction caused by embolism (n = 6, 2.4%), atrial fibrillation or flutter (n = 6, 2.4%), intestinal obstruction (n = 5, 2.0%) and unspecified fever (n = 5, 2.0%). Altogether these 8 conditions accounted for 25.1% of all reasons for readmission.

Factors predisposing for 30-day readmissions and combined outcomes

Factors associated with 30-day readmissions and 1-year composite outcomes are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

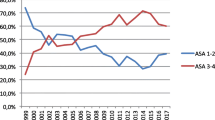

30-day readmissions were more frequent among patients who underwent surgery on the 4th day or later (30.0% vs. 9.4% in patients operated earlier, P = 0.014; adjusted OR 6.408, 95% CI 1.554–26.423), who lived in other municipalities than the city of Tampere (10.2% vs. 4.8%, P = 0.009; adjusted OR 2.186, 95% CI 1.179–4.055) and who did not receive orthogeriatric liaison service (11.8% vs. 6.2%, P = 0.012; adjusted OR 2.030, 95% CI 1.156–3.566) (Table 2). The effect of orthogeriatric liaison service was the most beneficial during the early follow-up whereas in longer follow-up readmissions seemed to cumulate similarly independent of orthogeriatric contribution (Fig. 2).

Composite outcome (readmission or death) was more common among patients aged ≥ 90 years (adjusted HR 1.920, 95% CI 1.371–2.689, compared to patients aged < 75 years), patients with a delay to surgery of ≥ 4 days (adjusted HR 1.997, 95% CI 1.026–3.888, compared to delay of 0–1 days), patients with a LOS of 3 days or more (adjusted HR 1.231, 95% CI 1.002–1.513), patients discharged on the second postoperative day or later (adjusted HR 1.343, 95% CI 1.076–1.675) and patients discharged on a Saturday (adjusted HR 1.511, 95% CI 1.024–2.229).

Discussion

In this regionally representative analysis, a long delay from admission to surgery was associated with an increased 30-day readmission rate whereas the use of orthogeriatric liaison service in the operating university hospital was associated with a decreased risk. A long delay to surgery was also linked with a higher frequency of the composite outcome (readmission or death in 1-year follow-up). Although the patients were discharged from the operating hospital very early (73% by the end of the first postoperative day), such short LOS was not related to an increased number of 30-day readmissions. Instead, especially considering the combined outcome, the result was the opposite: prolonged LOS was linked to more readmissions or deaths in a year’s time span. Patients discharged on Saturdays had a significant increase in the rate of the composite outcome whereas such increase was not evident in 30-day readmissions. Although patients receiving orthogeriatric liaison service had less 30-day readmissions than others, there was no difference in the 1-year composite outcome.

The 30-day readmission rate in our study was 8.3%, which represents the lowest rates reported in Finland (years 2010–2016) although we included also second hip fractures and patients living in nursing homes and institutions who are excluded from the nationwide surveillance [22]. Despite the short stay in the operating hospital, our 30-day readmission rate was slightly lower than in previous studies [16,17,18,19,20]. As it comes to 1-year mortality, the 22.1% mortality is well within the wide range (8.4–36%) reported in previous studies [27] and is in line with recent earlier observations from another part of Finland [6]. Contradicting some earlier studies [18, 27,28,29], gender had no effect on the occurrence of readmissions and death, and age did not affect 30-day readmission rate.

Supporting earlier observations [8, 9, 11, 30], a short delay (0–1 days) from admission to surgery had a connection to both lower 30-day readmission rates and fewer 1-year outcomes. A recent study suggests that a delay in hip fracture surgery for more than 12 h after admission impairs 30-day survival especially among patients with severe systemic disease [8] whereas the opposite has been reported as well [30]. As reasons for the delay were not recorded, these observations could not be confirmed. Furthermore, in the lack of clinical details, it cannot be precluded that the association between short delay and the outcomes is at least partly related to patient characteristics (e.g., fitness for surgery) rather than the care process as such. Use of direct oral anticoagulants and platelet inhibitors represent an increasingly common reason for delaying surgery [31] but in our materials, such drugs were used by a relatively small number of patients (approximately 5%, unreported observation) and they do not seem to increase 30-day mortality [31].

An important and new observation in the present study was that the very short LOS of 2 days or less was not associated with more frequent undesirable outcomes although a large share of patients was discharged to primary care wards with often limited possibilities for intensive treatments and lacking on-call physician and physician service on weekends. This result is in line with a Danish study where 30-day readmission rates were similar (ca. 12%) in fast-track group and conventional care group (LOS approximately 5 days in both groups) [26]. On the other hand, it is possible that patients who had short LOS were healthier and hence better suited for surgery and discharge without additional interventions, which could explain both LOS as well as lower 30-day readmission rate. Interestingly, if a patient was discharged on a Saturday, there was a higher risk for the composite outcome. There are two possible explanations for this association. First, it might be because orthogeriatric liaison service was not available on weekends, and the patient was not necessarily met on Friday due to the surgery. Secondly, patients discharged to primary care units most likely are not evaluated by a physician until next Monday which might cause delays in the care and management of possible acute conditions. This explanation is supported by the observation that patients living in the largest community and discharged to a secondary care hospital with 24/7 services had significantly lower rates of 30-day readmissions and composite outcome. On the other hand, it must be acknowledged that the association between postoperative LOS and increased mortality [32] may be for example due to complications and other health issues, which might also affect our findings considering LOS.

Patients who did not receive orthogeriatric liaison service had more 30-day readmissions, but the same result was not evident using 1-year composite outcome. This could be interpreted as orthogeriatric treatment especially preventing early readmissions while having a lesser impact with longer follow-up. According to one previous study, orthogeriatric treatment has been associated with decreased mortality and a lower readmission rate [33] whereas such association has not been reported in other studies [2], including a randomized controlled trial [14]. In all these studies, the orthogeriatric intervention has lasted longer than in our study (i.e., for 1.5–2 weeks), and we are not aware of earlier studies concerning the effect of very short orthogeriatric intervention, like ours, on readmission rates, mortality or clinical outcomes. In terms of mortality, orthogeriatric care at an orthogeriatric ward, instead of shared care of consultations at orthopedic ward, seems to be more effective [25, 34]. In our study, a large share of patients was treated in such ward in a secondary care hospital, and these patients had a lower readmission rate than others whereas there was no difference in the 1-year outcomes. Therefore, it is probable that the contribution of the orthogeriatric ward was beneficial for these patients. However, a greater study population is needed to further analyze the impact of the orthogeriatric ward at secondary care as well as the combined effect of liaison service and later care at geriatrician-led ward. Altogether, our results suggest that hip fracture patients’ care in a unit able to meet all the patients’ needs is beneficial in preventing early readmissions. In longer follow-up, new hospital admissions are frequent which is understandable considering the high age and multimorbidity in this patient group, and so it feels unlikely that orthogeriatric care would dramatically affect the outcomes in longer follow-up.

The strengths of this study include a regionally representative cohort of consecutive hip fracture patients. Patients treated using total hip replacement were not included in this study due to regional treatment protocols. Furthermore, coding of diagnoses in the discharge records may sometimes reflect geriatric patients’ comorbidities and the reason for readmission is not always coded in detail. As patient records (medical charts) were not reviewed in this study, the exact reasons and factors contributing to the outcomes unfortunately remain unclear. It is possible that differences in patients’ morbidity between different communities might explain the difference between the largest community and others. On the other hand, it is possible that some patients may not have been readmitted due to long distance (> 1.5 h ambulance ride) from the distant communities, which would lead to underestimation of readmission rates. It is, however, unlikely that such selection would have affected the results concerning orthogeriatric liaison service, delay to surgery or LOS. Due to insufficient patient numbers, community-level analyses about the value of orthogeriatric liaison service could not be performed, however.

Conclusion

Care-related factors such as the use of orthogeriatric liaison service and arrangement of later care at secondary care orthogeriatric ward, short delay from admission to surgery, and short total length of stay, that can be beneficial to hip fracture patients aged 50 years or older in terms of reducing readmissions and mortality. Although in general very short stay in tertiary care hospital appears safe, hip fracture patients should not be discharged to primary care wards with insufficient resources for managing hip fracture patients in the acute postoperative phase. Further study is required to specify how hip fracture patients’ treatment should be organized and if readmissions could be reduced using specific discharge criteria.

References

Veronese N, Maggi S (2018) Epidemiology and social costs of hip fracture. Injury 49:1458–1460

Abrahamsen C, Nørgaard B, Draborg E, Nielsen MF (2019) The impact of an orthogeriatric intervention in patients with fragility fractures: a cohort study. BMC Geriatr 19:268

Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergård M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J et al (2013) Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden: a report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos 8:136

Hu F, Jiang C, Shen J, Tang P, Wang Y (2012) Preoperative predictors for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury 43:676–685

Haentjens P, Magaziner J, Colón-Emeric CS, Vanderschueren D, Milisen K, Velkeniers B et al (2010) Meta-analysis: excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Med 152:380–390

Pajulammi HM, Pihlajamäki HK, Luukkaala TH, Nuotio MS (2015) Pre- and perioperative predictors of changes in mobility and living arrangements after hip fracture—a population-based study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 61:182–189

Peeters CMM, Visser E, Van de Ree CLP, Gosens T, Den Oudsten BL, De Vries J (2016) Quality of life after hip fracture in the elderly: a systematic literature review. Injury 47:1369–1382

Hongisto MT, Nuotio MS, Luukkaala T, Väistö O, Pihlajamäki HK (2019) Delay to Surgery of Less Than 12 Hours Is Associated With Improved Short- and Long-Term Survival in Moderate- to High-Risk Hip Fracture Patients. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 10:2151459319853142. https://doi.org/10.1177/2151459319853142

Al-Ani AN, Samuelsson B, Tidermark J, Norling Å, Ekström W, Cederholm T et al (2008) Early operation on patients with a hip fracture improved the ability to return to independent living: a prospective study of 850 patients. J Bone Jt Surg Am 90:1436–1442

Kamel HK, Iqbal MA, Mogallapu R, Maas D, Hoffmann RG (2003) Time to ambulation after hip fracture surgery: relation to hospitalization outcomes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 58:M1042–M1045

Nyholm AM, Gromov K, Palm H, Brix M, Kallemose T, Troelsen A (2015) Time to surgery is associated with thirty-day and ninety-day mortality after proximal femoral fracture: a retrospective observational study on prospectively collected data from the danish fracture database collaborators. J Bone Jt Surg Am 97:1333–1339

Grigoryan KV, Javedan H, Rudolph JL (2014) Orthogeriatric care models and outcomes in hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma 28:7

Hawley S, Javaid MK, Prieto-Alhambra D, Lippett J, Sheard S, Arden NK et al (2016) Clinical effectiveness of orthogeriatric and fracture liaison service models of care for hip fracture patients: population-based longitudinal study. Age Ageing 45:236–242

Prestmo A, Hagen G, Sletvold O, Helbostad JL, Thingstad P, Taraldsen K et al (2015) Comprehensive geriatric care for patients with hip fractures: a prospective, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 385:1623–1633

Eamer G, Taheri A, Chen SS, Daviduck Q, Chambers T, Shi X et al (2018) Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older people admitted to a surgical service. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD012485

Kates SL, Behrend C, Mendelson DA, Cram P, Friedman SM (2015) Hospital readmission after hip fracture. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 135:329–337

Pollock FH, Bethea A, Samanta D, Modak A, Maurer JP, Chumbe JT (2015) Readmission within 30 days of discharge after hip fracture care. Orthopedics 38:e7–13

Khan MA, Hossain FS, Dashti Z, Muthukumar N (2012) Causes and predictors of early re-admission after surgery for a fracture of the hip. J Bone Jt Surg Br 94B:690–697

Basques BA, Bohl DD, Golinvaux NS, Leslie MP, Baumgaertner MR, Grauer JN (2015) Postoperative length of stay and 30-day readmission after geriatric hip fracture: an analysis of 8434 patients. J Orthop Trauma 29:e115–e120

Ali AM, Gibbons CER (2017) Predictors of 30-day hospital readmission after hip fracture: a systematic review. Injury 48:243–252

Buecking B, Eschbach D, Koutras C, Kratz T, Balzer-Geldsetzer M, Dodel R et al (2013) Re-admission to Level 2 unit after hip-fracture surgery—risk factors, reasons and outcome. Injury 44:1919–1925

National Institute for Health and Welfare (2017) PERFECT—Hip Fracture [Internet]. PERFECT—PERFormance, Effectiveness and Cost of Treatment episodes. https://thl.fi/fi/tutkimus-ja-kehittaminen/tutkimukset-ja-hankkeet/perfect/osahankkeet/lonkkamurtuma. [Finnish]. Accessed 10 Nov 2018

Patel JN, Klein DS, Sreekumar S, Liporace FA, Yoon RS (2020) Outcomes in multidisciplinary team-based approach in geriatric hip fracture care: a systematic review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 28(3):128–133

Arshi A, Rezzadeh K, Stavrakis AI, Bukata SV, Zeegen EN (2019) Standardized hospital-based care programs improve geriatric hip fracture outcomes: an analysis of the ACS NSQIP targeted hip fracture series. J Orthop Trauma 33:e223–e228

Kammerlander C, Roth T, Friedman SM, Suhm N, Luger TJ, Kammerlander-Knauer U et al (2010) Ortho-geriatric service—a literature review comparing different models. Osteoporos Int 21S:637–646

Pollmann CT, Røtterud JH, Gjertsen J-E, Dahl FA, Lenvik O, Årøen A (2019) Fast track hip fracture care and mortality—an observational study of 2230 patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 20:248

Abrahamsen B, van Staa T, Ariely R, Olson M, Cooper C (2009) Excess mortality following hip fracture: a systematic epidemiological review. Osteoporos Int 20:1633–1650

Smith T, Pelpola K, Ball M, Ong A, Myint PK (2014) Pre-operative indicators for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 43:464–471

Kannegaard PN, van der Mark S, Eiken P, Abrahamsen B (2010) Excess mortality in men compared with women following a hip fracture. National analysis of comedications, comorbidity and survival. Age Ageing 39:203–209

Öztürk B, Johnsen SP, Röck ND, Pedersen L, Pedersen AB (2019) Impact of comorbidity on the association between surgery delay and mortality in hip fracture patients: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Injury 50:424–431

Daugaard C, Pedersen AB, Kristensen NR, Johnsen SP (2019) Preoperative antithrombotic therapy and risk of blood transfusion and mortality following hip fracture surgery: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Osteoporos Int 30:583–591

Åhman R, Siverhall PF, Snygg J, Fredrikson M, Enlund G, Björnström K et al (2018) Determinants of mortality after hip fracture surgery in Sweden: a registry-based retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 8:15695

Neuerburg C, Förch S, Gleich J, Böcker W, Gosch M, Kammerlander C et al (2019) Improved outcome in hip fracture patients in the aging population following co-managed care compared to conventional surgical treatment: a retrospective, dual-center cohort study. BMC Geriatr 19:330

Moyet J, Deschasse G, Marquant B, Mertl P, Bloch F (2019) Which is the optimal orthogeriatric care model to prevent mortality of elderly subjects post hip fractures? A systematic review and meta-analysis based on current clinical practice. Int Orthop SICOT 43:1449–1454

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

HP has received lecture fees (unrelated to the present study) from Boehringer Ingelhelm and Orion Pharma. EJ has received lecture fees (unrelated to the present study) from Novartis, Orion Pharma, and Finnish societies of medical professionals.

Ethical approval

The institutional reviews board of Tampere University Hospital approved the study (R19512). Because this is a retrospective register-based study, approval from ethics committee is not required according to EU and national legislation.

Informed consent

Informed consent is not required according to EU and national legislation.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarimo, S., Pajulammi, H. & Jämsen, E. Process-related predictors of readmissions and mortality following hip fracture surgery: a population-based analysis. Eur Geriatr Med 11, 613–622 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00307-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00307-0