Abstract

The Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) dataset is used to examine projected changes in temperature and precipitation over the United States (U.S.), Central America and the Caribbean. The changes are computed using an ensemble of 31 models for three future time slices (2021–2040, 2041–2060, and 2080–2099) relative to the reference period (1995–2014) under three Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs; SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5). The CMIP6 ensemble reproduces the observed annual cycle and distribution of mean annual temperature and precipitation with biases between − 0.93 and 1.27 °C and − 37.90 to 58.45%, respectively, for most of the region. However, modeled precipitation is too large over the western and Midwestern U.S. during winter and spring and over the North American monsoon region in summer, while too small over southern Central America. Temperature is projected to increase over the entire domain under all three SSPs, by as much as 6 °C under SSP5-8.5, and with more pronounced increases in the northern latitudes over the regions that receive snow in the present climate. Annual precipitation projections for the end of the twenty-first century have more uncertainty, as expected, and exhibit a meridional dipole-like pattern, with precipitation increasing by 10–30% over much of the U.S. and decreasing by 10–40% over Central America and the Caribbean, especially over the monsoon region. Seasonally, precipitation over the eastern and central subregions is projected to increase during winter and spring and decrease during summer and autumn. Over the monsoon region and Central America, precipitation is projected to decrease in all seasons except autumn. The analysis was repeated on a subset of 9 models with the best performance in the reference period; however, no significant difference was found, suggesting that model bias is not strongly influencing the projections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Climate change is one of the greatest challenges faced by humankind as it poses an existential threat to many aspects of the current social–ecological landscape of natural and human systems. Over North and Central America and the Caribbean, observations provide irrefutable evidence that climate change is already happening. For instance, there has been a decreasing trend in snow accumulation in the western United States (U.S.) during the cold season over the last several decades (Mote et al. 2005; Ashfaq et al. 2013). Similarly, several regions are experiencing increasing trends in minimum temperatures (Batibeniz et al. 2020) and more intense and widespread precipitation extremes (Rastogi et al. 2020). Mean temperatures are also increasing in southwestern U.S. and northwestern Mexico (Cavazos et al. 2020). An anthropogenic footprint is also detectable in the greater frequency of multivariate extremes, such as droughts (Diffenbaugh et al. 2015) and wildfires (Radeloff et al. 2018; Abatzoglou and Williams 2016). Studies suggest that continued greenhouse gas emissions will lead to further warming, along with long-term changes in all components of the climate system, increasing the likelihood of widespread and potentially irreversible impacts on social and ecological systems (IPCC 2014; Sillmann et al. 2013; Pu et al. 2020; Christensen et al. 2013; Fischer and Knutti 2016; Easterling et al. 2017; Diaconescu et al. 2018; Giorgi et al. 2018; Moreno et al. 2019; Veas-Ayala et al. 2018; Oppenheimer et al. 2019; Ashfaq et al. 2020; Cook et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020a, b). These expected changes in climate characteristics will likely intensify the regional hydrological cycle (Ashfaq et al. 2013; Naz et al. 2016), exacerbate the risk of water stress in the regions where river runoff is dominated by snowmelt (Pagan et al. 2016), and increase the population’s exposure to climate extremes (Batibeniz et al. 2020).

General circulation models (GCMs) are the most sophisticated tools available to investigate the climate system response to increases in radiative forcing and to identify the mechanisms driving that response (Taylor et al. 2012; Flato et al. 2013). However, despite potential progress over the last two decades in GCM simulations of past, present, and future climate, considerable regional biases, and other inadequacies still exist due to incomplete representation of key regional scale processes, poor parameterizations, imperfect initial conditions, and coarse resolutions (van Der Wiel et al. 2016; Wehner et al. 2014; Diallo et al. 2019). These modeling deficiencies are in addition to the influences of internal variability of the Earth system that collectively lead to uncertainty in projections of climate change at global to regional scales. To address these challenges, a coordinated framework by the climate modeling community has produced different phases of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP), where state-of-the-art GCMs are run with a common setup. CMIP aims to better understand past, present, and future climate change arising from both natural and forced variability, and in response to changes in radiative forcing, in a multimodel ensemble context (Eyring et al. 2016). CMIP also supports the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Assessment Reports (AR). However, confidence in the projections of GCMs-based future climate partially depends on their skill in simulating current and past climates. Previous comparative evaluations of climate simulations have shown that CMIP Phase 5 (CMIP5) models performed better than CMIP Phase 3 (CMIP3) models, particularly over North and Central America including Caribbean (Bukovsky et al. 2015; Maloney et al. 2014; Ryu and Hayhoe 2014; Koutroulis et al. 2016; Hidalgo and Alfaro 2015).

New simulations from the latest state-of-the-art climate models participating in phase 6 of the CMIP (CMIP6) are now available (Eyring et al. 2016). These simulations provide a new opportunity to evaluate the Earth system response to change in radiative forcings during the twenty-first century. The evaluation of CMIP6 simulations over several regions, including South Asia, Africa and Arabian Peninsula, suggest that their simulated responses exhibits differences from earlier CMIPs studies (Almazroui et al. 2020a,b,c). The CMIP6 models are typically enhanced versions of the models that participated in earlier phases of CMIP. Most have improved parameterizations of cloud microphysics and better representations of various Earth system processes, such as biogeochemical cycles and ice sheets. The average resolution of CMIP6 GCMs is also finer than that of CMIP5 GCMs (Eyring et al. 2016). Several studies have evaluated CMIP6 GCM over the U.S. in the historical period. For instance, Wehner et al. (2020) reported no discernible differences between CMIP5 and CMIP6 GCMs in the simulation of daily precipitation and temperature extremes in the historical period. Similarly, Srivastava et al. (2020) evaluated daily characteristics of precipitation in the historical period and concluded that most CMIP6 models overestimate the occurrence and variability of wet spell durations over the western U.S. while they underestimate the occurrence of dry spells over most of the southern U.S. Likewise, Akinsanola et al. (2020) noted that CMIP6 models showed relatively better skill in the simulation of warm season extreme precipitation over the U.S. However, studies focused on the evaluation of future CMIP5 climatic changes over the North and Central America and the Caribbean are relatively limited and mostly thus far have focused on the North American monsoon that exhibits drying in response to increase in radiative forcing (Jin et al. 2020; He et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020a, b). Therefore, a study assessing the CMIP6 models performance and their simulated precipitation and temperature changes in the twenty-first century over the region encompassing the contiguous U.S., Central America (including Mexico), and the Caribbean, is currently lacking.

This study addresses these gaps by assessing the future climate responses at a subregional scale over these regions through the analysis of a large suite of CMIP6 GCMs under various Shared Socioeconomic Pathways/Representative Concentration Pathways (SSP/RCP) scenarios. In addition, similar analyses are performed using a subset of GCMs that are selected based on their best performance in the historical period. The projections are divided into near-term, mid-term, and far-term time periods. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the observed and model data, along with methods and metrics used to assess model performance and to select the best-performing models. Sections 3 and 4 discuss the results of the study for the present and future climate, respectively. A summary and conclusions are outlined in the last section.

2 Data and Methodology

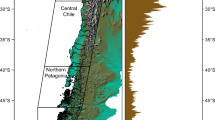

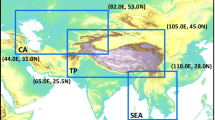

This study utilized 31 CMIP6 GCMs (Table 1) (hereafter M31) that are publicly available (Eyring et al. 2016; https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6) to assess the accuracy of projected changes in temperature and precipitation over the contiguous U.S., Central America, and the Caribbean region (Fig. 1). For the GCM evaluation, monthly temperature observations were obtained from the Climatic Research Unit (CRU, Harris et al. 2014) and the University of Delaware (UoD, Willmott et al. 2001), and monthly precipitation observations were obtained from the CRU and the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC, Becker et al. 2013). All CMIP6 GCM data and observations are interpolated to a common 1˚ × 1˚ latitude–longitude grid using conservative remapping (Iturbide et al. 2020).

The analysis domain was divided into six subregions: Western North America (WNA); Central North America (CNA); Eastern North America (ENA); North Central America (NCA); South Central America (SCA); and the Caribbean (CAR) (Fig. 1). The regionalization is based on that used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), as explained in detail by Iturbide et al. (2020). The time spans for analysis are divided into a historical reference period (1995–2014) and three future periods (near term; 2021–2040, mid term; 2041–2060, and far term; 2080–2099). The models are evaluated against observations for the reference period while future changes with respect to the reference period are calculated over four seasons, winter (December–January–February; DJF), spring (March–April–May; MAM), summer (June–July–August; JJA), and autumn (September–October–November; SON), under the low (SSP1-2.6), medium (SSP2-4.5), and high (SSP58.5) forcing scenarios, as described in Gidden et al. (2019) and O’Neill et al. (2016). The simulated future changes are considered robust if at least 66% of the models agree on the direction of change (Haensler et al. 2013; Almazroui et al. 2020a,b,c). Moreover, a two-tailed Student t test is used to test the significance of simulated changes in each grid box. In addition to spatial time–average plots, the results are also presented as time series of annual averages for each subregion. These plots show the median value of the 31 models along with the 66% likely range (i.e., 17–83 percentiles) around the median line. Trends and levels of significance are then calculated using the Mann–Kendall two-tailed test (Mann 1945; Kendall 1975; Sen 1968; Wilks 2019).

A subset of the best-performing models is also selected based on a bias analysis along with other performance measures. For simplicity, each CMIP6 model is assessed using averages calculated over the entire domain instead of over each subregion. The bias analysis is based on a threshold of 1.5 standard deviations (± 1.5 STD) about the multimodel mean bias for the historical period. According to this criterion, any model with bias exceeding the threshold is not a candidate for selection in the subset set of models (Almazroui et al. 2017a,b). Afterwards, the pattern correlation coefficient (PCC) and the root mean square error (RMSE) for annual mean temperature and precipitation are calculated. For temperature (precipitation), models with an RMSE of less than 2 °C (1 mm/day) and a pattern correlation above 0.96 (0.60) are considered for selection. Models that satisfy the selection criteria along with the RMSE and PCC thresholds for temperature and precipitation are then added to the set of selected models. The rationale for this model selection is to understand whether or not skill-based model selection has any impact on the robustness of simulated changes in temperature and precipitation in the future period (Knutti et al. 2017).

3 Analysis of Present Climate

3.1 Temperature and Rainfall Climatology

The spatial distribution of observed and simulated annual and seasonal mean temperatures averaged over the reference period 1995–2014 is shown in Fig. 2. Annual mean temperature shows a latitudinal variation ranging from 0 ºC in the north to nearly 30 ºC in the south (Fig. 2, middle and lower panel). The observed spatial and seasonal variations in temperature are well captured in the CMIP6 ensemble (Fig. 2, top row). There is substantial spatial heterogeneity in seasonal mean temperatures, particularly in winter and summer. For instance, winter temperatures fall to the deepest minima (− 12 °C) over the upper Midwest, which frequently experiences cold waves due to cold Arctic air flow, while summer average temperatures reach highs (30 °C) over Texas and northeastern Mexico as well as northwestern Mexico and Arizona. These seasonal variations in temperature patterns are well represented in the CMIP6 ensemble (Fig. 2).

Spatial distribution of annual and seasonal mean temperature (°C) obtained from the ensemble mean of M31 (upper panels), and observations (CRU: middle panels, UoD: lower panels) for the present climate, 1995–2014. The 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th columns represent the temperature distribution for annual, winter, spring, summer and autumn, respectively

Figure 3 compares the distribution of precipitation between the observations and the CMIP6 ensemble for the 1995–2014 period. The simulated annual and seasonal precipitation patterns generally resemble those in the observations. However, a number of regional biases exist in seasonal precipitation magnitudes, including excess precipitation over the upper Midwest during winter and spring, a lack of spatial detail in the topography-driven winter precipitation over the western U.S., and an overly strong North American summer monsoon. Nonetheless, by and large, the simulated precipitation captures the general characteristics of the observed variations in seasonal precipitation across the study region.

Same as Fig. 2, except the spatial distribution of annual and seasonal mean precipitation (mm/month) obtained from ensemble mean of M31 (upper panels), and observations (CRU: middle panels, GPCC: lower panels) for the present climate 1995–2014

3.2 Distribution of the Annual Cycle

The annual cycle of observed and simulated temperatures over the six subregions is shown in Fig. 4. Although there is overall consistency in the annual amplitudes between the simulations and the observations, there are some biases in the monthly magnitudes (from − 0.02 to 1.06 °C). For instance, summer (JJA) temperatures are overly warm in the CMIP6 ensemble over the WNA (1.37/1.24 °C relative to CRU/UoD), CNA (1.68/2.11), CAR (0.73/1.01), SCA (0.43/0.51), and ENA (0.55/0.82) regions, and are excessively cold over WNA (-1.50/-1.04 °C relative to CRU/UoD) in the winter (DJF) months. For the other seasons, the simulated annual cycle of temperatures in the CMIP6 ensemble is within ~ 1 °C of the observations over most of the subregions. The simulated temperature biases range from − 0.93 to 0.88 °C (− 0.02 to 1.27 °C) with respect to CRU (UoD) at annual scale.

The annual cycle of observed and simulated precipitation for the six subregions is shown in Fig. 5. At annual scale, the simulated precipitation biases range from − 37.9 to 58.45% (− 33.23–51.96%) with respect to CRU (GPCC). In general, the disagreement between the observations and the CMIP6 ensemble is quite substantial in the case of precipitation. For instance, the simulated precipitation is overly strong in WNA and NCA throughout the year with particularly large biases (~ 20 mm/month) in the cold season months. In contrast, the monthly precipitation amounts in the CMIP6 ensemble are substantially lower than the observations in SCA and CAR. The simulated annual cycle exhibits both wet and dry biases over the CNA region. The dominant annual cycle over SCA, except for the central part of its Caribbean coast, is monsoonal, with highest temperatures in April–May and lowest temperatures in January (Fig. 4). Rainfall in most of SCA is characterized by two maxima in June and September, an extended dry season from November to April, and a short midsummer drought (MSD) in July–August (Fig. 5). To some extent, precipitation seasonality is explained by the seasonal strength of the North Atlantic Subtropical High (NASH) and the North–South migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) (Taylor and Alfaro 2005). The Caribbean islands have two main seasons, characterized by differences in temperature and precipitation. The wet or rainy season with higher temperatures and more accumulated precipitation occurs during the boreal summer and part of spring and autumn. The MSD is also present in most of the Caribbean, particularly in the Greater Antilles (Taylor and Alfaro, 2005). The precipitation annual cycle in Fig. 5 for SCA and CAR is in good agreement with the annual cycles previously presented over the subregions (Centella-Artola et al. 2015; Duran–Quesada et al. 2020; Maldonado et al. 2018; Martínez-Castro et al. 2018; Vichot-Llano et al. 2020a).

The annual cycle of precipitation (mm/month) obtained from observations (CRU and GPCC) and the ensemble mean of M31over six subregions for the base period 1995–2014. Only precipitation over land is considered. Note that the vertical scales of the SCA and CAR panels are different from the vertical scales of the other subregions. The horizontal dashed lines represent the mean annual precipitation in dataset

As mentioned in the methodology section, the annual cycles shown are averages over the subregions and do not necessarily reflect the heterogeneity within the region, particularly that driven by topographic complexity over WNA, NCA, SCA, and CAR (e.g., Taylor and Alfaro 2005). However, the Caribbean MSD (Magaña et al. 1999; Amador 2008) is well reproduced by the model ensemble, even if it is underestimated relative to the observed precipitation. The MSD is also a regular feature of the southern part of NCA and the Pacific side of SCA, but it is not reflected in the area average (Curtis and Gamble 2008). This is an important limitation for stakeholders since MSD is an important aspect of the precipitation annual cycle in SCA.

3.3 Performance of Individual CMIP6 Models

Figure 6a shows the regional average of the terrestrial precipitation bias in each of the 31 CMIP6 models with respect to two sets of observations (GPCC and CRU). Most of the models have a wet bias over the analysis domain, as the simulated precipitation from 23 (21) GCMs is higher than observed while 8 (10) is lower magnitudes than observed. As a result, the ensemble mean also has a wet bias of 0.15 (0.2) mm/day as compared to GPCC (CRU). We subselect models based on their performance by using observed annual standard deviation as a threshold. Models whose bias is within the range of ± 1.5 STDs are identified as better performing models. The models whose bias exceeds ± 1.5 STD (~ ± 0.34 mm/day) are not considered for further analysis, including ACCESS–ESM1–5, CIESM, CNRM–CM6–1–HR, CNRM–CM6–1, CNRM–ESM2–1, CanESM5, IPSL–CM6A–LR, MRI–ESM2–0, and NESM3. It is interesting to note that the finest resolution GCM (CNRM–CM6–1–HR, Table 1) is not among the best-performing models for precipitation. Overall, 23 of the 31 models qualify as better performing models following this criterion.

Area-averaged bias of CMIP6 models for (a) precipitation (mm/day), and (b) temperature (°C) for the period 1995–2014. The blue and red bars in a show wet and dry bias, respectively, while in b they show cold and warm bias, respectively. The horizontal dashed and dashed-dot lines show the ensemble mean bias in M31 with respect to each of the observational datasets, as labelled. The solid lines in a and b show the magnitude of ± 1.5 standard deviation

The biases in the simulated temperatures over the analysis domain are shown in Fig. 6b. For temperature, 19 (15) of the 31 models exhibit a warm bias when compared to the CRU (UoD) observations, resulting in a net positive bias in the ensemble mean. Among 31 models, 23 (28) simulate mean temperatures within the ± 1.5 STD range as compared to the CRU (UoD) observations. Again, the CNRM–CM6–1–HR has a large bias, as it is the coldest CMIP6 model. It should be noted that the observational datasets also differ between themselves. The ensemble mean bias is less than 0.2 °C with respect to CRU, while it is ~ 1 °C with respect to UoD. Therefore, any conclusion regarding simulated bias depends on the choice of reference data.

Using the above-mentioned model selection criteria, we find that 14 models exhibit both precipitation and temperature biases within the ± 1.5 STD range of observations. Given that these analyses are conducted using domain averages, it is quite possible that the low bias of some of these selected 14 models may be due to compensating errors across the analysis domain. Therefore, the selected models are further evaluated to determine how well their spatial distributions of temperature and precipitation agree with the corresponding observed patterns (Fig. 7).

Scatter plot between pattern correlation coefficient (PCC) and root–mean–square error (RMSE) for precipitation (a, b) and temperature (c, d) for two observation datasets and 14 selected CMIP6 models averaged over the entire domain for the period 1995–2014. The vertical dashed line shows the threshold of RMSE (1 mm/day for precipitation) and (2 °C for temperature). The horizontal dashed line shows the PCC thresholds 0.60 for precipitation and 0.96 for temperature. Models with open (white) circles exceed the error thresholds for selection, while the closed (black) circles indicate the candidate models. The final selection of models is shown by an asterisk in Table 1

Figure 7 shows PCC and RMSE for annual mean precipitation and temperature for each of the selected models. These analyses are shown separately for each reference data (CRU, GPCC) to account for observational uncertainty. Additional imposed selection criteria include the RMSE ≤ 1 mm/day for precipitation (Fig. 7a, b), and ≤ 2 °C for temperature (Fig. 7c, d). The filled circles represent models that satisfy the new criteria, while the hollow circles represent those that do not. Of the 14 models, nine fulfill these conditions for both precipitation and temperature with respect to both sets of observations. These models have been marked with an asterisk next to their names in Table 1. The rationale for adopting this two-step model selection procedure is to retain only those models that demonstrate good fidelity in simulating the present climate, which should increase confidence in the reliability of future projections (Knutti et al. 2017). We also recognize that the selection of reference datasets has an impact on the statistics and that model validation based on the different reference datasets may result in a different selection of models. Such observation-based uncertainty is more pronounced in the case of precipitation, partly due to the fact that precipitation is quite variable in space and time, and its magnitudes are more sensitive to the choice of algorithms used in its interpolation from stations to grids. This is particularly true over topographically complex regions, such as NCA and SCA, as noted by Hannah et al. (2017). This disagreement among observational datasets has been discussed in previous works over these regions (e.g., Cerezo-Mota et al. 2016; Cavazos et al., 2020).

4 Future Changes in Annual Mean Temperature and Precipitation

Figure 8 shows the mean changes in annual temperature and precipitation for the near (2021–2040), mid (2041–2060) and far (2080–2099) futures with reference to the 1995–2014 period under the SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5 scenarios. Given that radiative forcing is very similar across all future scenarios in the initial decades, the projected changes in near-future temperatures are not very sensitive to the choice of the emissions pathway (Fig. 8, left panels). These changes include an increase in temperatures over the northern U.S. of up to 2 °C and over Central America of ~ 1 °C. For the mid-future period (Fig. 8, middle column), the projected increase in temperature is up to 3 °C under SSP2-4.5 and 4 °C under SSP5-8.5 scenario. As expected, the strongest increase in temperatures is seen in the far-future over the entire domain under both SSP-2–4.5 and SSP5-8.5. These increases are particularly pronounced (+ 6 °C) over the northern half of the U.S. as a result of changes in the snow albedo feedback (e.g., Colorado-Ruiz et al. 2018; Ashfaq et al. 2016). Warming over the Caribbean is relatively low (+ 1.2 °C for SSP-2–4.5 and + 3.7 °C for SSP-5–8.5), as found by Vichot-Llano et al. (2020b). Table 2 summarizes the area-averaged changes in future simulations over the six subregions (see Fig. 1). The projected temperature changes are significant and robust as more than two-thirds of the models (66%) agree on the direction of the temperature change over the entire domain.

Spatial distribution of changes in annual mean temperature (°C) for the near (2021–2040), mid (2041–2060), and far (2080–2099) future, under the SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5 scenarios with respect to 1995–2014 using the ensemble mean of M31. The backslash and forward slash indicate the grid boxes showing significant and robust changes, respectively, while hatching represents the grid boxes having both significant and robust changes. Significance is defined based on the two-tailed Student t test, while robustness is when at least 66% of the models project a climate change signal in the same direction

As compared to the present climate, the projected annual precipitation displays a wetter response over the contiguous U.S. and drier response over Central America under the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 forcing throughout the twenty-first century (Fig. 9), which progressively increase in magnitude over time as a function of the strength of the radiative forcing. By the end of the twenty-first century, precipitation is projected to increase (decrease) by 10–30% (10–40%) over the U.S. (Central America) under SSP5-8.5 scenario. The change in precipitation during the winter and spring is consistent with the annual pattern (Fig. S2). There is little variation in the SCA and CAR subregions in spring, although the precipitation response is relatively mixed in summer and autumn. For instance, by the end of the twenty-first century, change in precipitation is negative under the SSP5-8.5 scenario except over parts of WNA and ENA. Similarly, autumn precipitation is projected to increase with the exception of some pockets. The simulated precipitation response is less robust over CNA and NCA under the SSP1-2.6 and SSP2-4.5 scenarios than that under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. The north–south projected changes in precipitation are in agreement with the previous projections of a decrease in future precipitation over the southern subregions, including most Caribbean countries, using the SRES climate scenario A2 (Karmalkar et al. 2011), A2 and B2 (Campbell et al. 2010) and RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 (Maloney et al. 2014; Torres-Alavez et al. 2014; Colorado-Ruiz et al., 2018). However, the complexity of the Caribbean subregion requires further investigation, as previous studies suggest that there are marked differences in the precipitation trends in the present and future periods between northwestern and southeastern parts (Imbach et al. 2018; Taylor et al. 2018; Oglesby et al. 2016).

Same as Fig. 8 except for precipitation change (in %)

Figure 10 shows the interannual evolution of temperature changes over each of the six subregions in the 2021–2099 period with reference to the 1995–2014 period in M31 under the three emission scenarios. After 2040, simulated changes under the three scenarios begin to diverge for most of the regions. As previously noted, the pace of warming is a function of the magnitude of the radiative forcing with the strongest increase under SSP5-8.5 and the slowest increase under SSP1-2.6. In fact, temperature shows a decreasing trend after the 2070s in all subregions under SSP1-2.6 as the radiative forcing gradually gets weaker after peaking before 2070 (Fig. 10). A detailed description of the uncertainty associated with the projected annual mean temperature over the six subregions under the three scenarios is provided in Table 3. The uncertainty in the trajectory of temperature changes is larger under the high-emission scenario than under the other two scenarios (Table 3). Moreover, regardless of the scenario, uncertainty increases towards the end of the century (shaded areas in Fig. 10). These results indicate that over the course of the twenty-first century, a large increase in temperature is likely over the U.S., while a relatively smaller but still significant increase in spread is projected over Central America and the Caribbean, particularly under the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios. These findings are consistent with earlier studies (e.g., Colorado-Ruiz et al. 2018) and for the SCA and CAR regions (Hidalgo et al. 2013; Hidalgo et al. 2017; Vichot-Llano et al. 2020b) using CMIP5 models.

Projected evolution of changes in mean annual temperature in the twenty-first century with respect to 1995–2014 under SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5 using a M31 ensemble. Aqua, blue, and maroon curves represent the result for median values under SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5, respectively, and the shaded areas around each of the curves represent the likely range (66% of the projected changes). The curves are obtained by taking the difference of each future year with respect to the average from the historical period (1995–2014), and then smoothing with a 7-year running average

Figure 11 shows the projected evolution of the change in mean annual precipitation for the period 2021–2099 with reference to the period 1995–2014. As in Fig. 10, the curves represent the median of the 31 CMIP6 models, while the shading represents the likely range. As previously noted in the spatial maps, there is an increasing trend over the U.S. under all three scenarios. In contrast, the projected precipitation shows a decreasing trend over Central America and the Caribbean under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5, and little or almost no change under the low-emission scenario. As in the case of temperature, the spread of uncertainty among CMIP6 models (66% likely range) is large for the high-emission scenario as compared to the other two (Table 3). For all scenarios, the uncertainty spread increases towards the end of the twenty-first century (Fig. 11, Table 3). The temperature and precipitation trends for each of the six subregions over the period 2021–2099 under the three SSPs are shown in Table 4.

Same as Fig. 10 except showing precipitation changes (in %)

So far, the analyses of the projections of temperature and precipitation changes are based on the ensemble mean of the 31 CMIP6 models. To investigate the sensitivity of climate change signals over the study domain to the choice of models based on their accuracy over the reference period, we assess these projections using the mean of the 9 best-performing CMIP6 models (hereafter M9), identified in Table 1 with an asterisk, which have relatively small bias in the reference period. This reduced ensemble of selected models projects spatial changes in temperature and precipitation for the near, mid, and far futures under the three scenarios (Fig. S5) that are similar to those projected by the ensemble of all models (see Figs. 8 and 9). However, the magnitude of temperature changes is larger in the limited selection of models, particularly in the second half of the twenty-first century. Similarly, the selected models also produce relatively strong precipitation changes than the full ensemble in all time periods, and under all scenarios, with some minor exceptions. The seasonal changes in temperature and precipitation based on the M9 ensemble are shown in Figs. S6 and S7, which are very similar to the changes in the M31 ensemble (Figs. 8 and 9).

Table 2: Projected changes in mean annual temperature (Temp, °C) and precipitation (Prec, %) over six subregions for near (2021–2040), mid (2041–2060) and far (2080–2099) future periods with reference to the present climate (1995–2014) under three SSP scenarios based on the M9 ensemble Table 1 (GCMs with an asterisk in Table 1).

The time evolution of changes in individual months over the six regions using the M31 ensemble under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 is shown in Fig. 12. Over the U.S., temperature increases are particularly pronounced in late summer and fall months after the 2050s under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. Over Central America, the increases under SSP5-8.5 are more pronounced in summer. As previously noted, the M9 ensemble projects temperature changes similar in direction to those of the M31 ensemble (Fig. 13), but the magnitude of increase is larger. Similarly, the changes in temperature under the low-emission scenario are relatively small in both the M31 and the M9 ensembles (Fig. S8).

Same as Fig. 12 except the changes are shown for the M9 ensemble

For the period 2021–2099, temperature changes simulated by the M31 ensemble across all months over all six subregions are positive, except for 2 months under SSP1-2.6 and 1 month under SSP5-8.5. For the M9 ensemble, negative changes are projected for 12 months, 19 months, and 9 months under SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5, respectively, which account for 0.12%, 0.33%, and 0.16% of the total months under SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5, respectively.

Monthly changes in precipitation in the M31 ensemble exhibit characteristics similar to those for temperature when compared across the three future scenarios (Fig. 14). Increases in precipitation over the three U.S. regions occur predominantly in the winter months and intensify over time. The future precipitation deficit over NCA is mostly a result of drying in spring while that over SCA is due to drying in both spring and summer, which strengthens with increases in the radiative forcing. Moreover, in SCA and CAR, the driest months of the summer are July–August, which suggest an enhanced and extended MSD, especially after the 2050s and under the high-emission scenario. While the pattern of change is similar in the M9 ensemble (Fig. 15), the magnitude of change is stronger and more variable. Lack of substantial differences between the M31 and M9 ensembles suggests that the dipolar precipitation response in CMIP6 models is robust and does not necessarily depend on their accuracy in the reference period. Such an insensitivity of the simulated precipitation response to the performance-based selection of GCMs potentially suggests that the large-scale dynamic and thermodynamic responses to increases in radiative forcing in CMIP6 GCMs are perhaps dictated by similar synoptic-scale processes across the models that are relatively insensitive to regional biases over the terrestrial domain used in our analyses. However, further investigation is needed to quantify the underlying causes of the relatively robust precipitation response over these regions.

Same as Fig. 14 except the changes are shown for the M9 ensemble

5 Concluding summary

In this study, we analyzed 31 CMIP6 models to assess the projected temperature and precipitation changes over six subregions across the contiguous U.S., Central America, and the Caribbean during the twenty-first century under three shared socioeconomic scenarios (SSP1-2.6; SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5).

We first examined the performance of the CMIP6 models over the reference period 1995–2014. The CMIP6 ensemble reproduces the observed distribution of temperature to within − 0.93 °C to 0.88 °C (− 0.02 °C to 1.27 °C) relative to CRU (UoD) over the full domain and reproduces the observed distribution of precipitation to within − 37.90–58.45% (− 33.23–51.96%) relative to CRU (GPCC) over much of the domain. However, models produce too much precipitation over the western U.S. and the monsoon region and too little over southern Central America.

We examined the projected changes in temperature and precipitation for three future periods (2021–2040; 2041–2060; 2080–2099) with reference to the 1995–2014 period under three future scenarios. The CMIP6 ensemble projects a continuous increase in temperature over the U.S., Central America, and the Caribbean under all three future scenarios. The temperature increase is more pronounced over the U.S. than over Central America and the Caribbean. By the end of the twenty-first century, the temperature is projected to increase by up to approximately 6 °C over northern parts of the domain under the high emission SSP5-8.5 scenario.

The spatial distribution of precipitation changes reveals a meridional dipole-like pattern, with an increase (10–30%) over the U.S. and a decrease (10–30%) over Central America and the Caribbean under all three scenarios with regional and seasonal variations over the entire domain. The eastern and central subregions (e.g., ENA and CNA) show an increase in precipitation during winter and spring, and a decrease during summer and autumn. The projected precipitation over Central America exhibits decreases during the winter, spring, and summer seasons, and an increase in autumn. The projected changes in precipitation are more pronounced towards the end of the twenty-first century. Even though there is no clear trend in precipitation changes for some regions, such as SCA, the positive temperature trends can increase aridity and decrease runoff through the intensification of regional hydrological cycle (Alfaro-Córdoba et al. 2020; Moreno et al. 2019; Veas-Ayala et al. 2018).

We further investigated projected changes using a subset of 9 of the best-performing models. The ensemble mean of selected models, does not exhibit significant differences in projected changes when compared with the ensemble mean of all models. Further investigation of the dynamic and thermodynamic characteristics is needed to quantify the relative insensitivity of simulated future responses to biases in the reference period. The use of two observational datasets for model evaluation highlights the uncertainty that exists in the observations and underscores the value of using multiple observational datasets in model evaluation.

The projected changes are spatially consistent between CMIP6 and CMIP5 models over this region. There are differences in terms of magnitude of the projected changes, which is understandable given the differences in the strength of radiative forcing between the SSP/RCP scenarios of CMIP6 and the RCP scenarios of CMIP5. Interestingly, autumn is the only season that exhibits positive rainfall anomalies in the southern tropical subregions in both the CMIP5 and CMIP6 (NCA, SCA), reflecting the possibility of delay in the demise of the summer precipitation season and the monsoon rains (e.g., Ashfaq et al. 2020; Bukovsky et al. 2015; Colorado-Ruiz et al., 2018; Lee and Wang et al. 2014; Torres-Alavez et al. 2014). Although we note that large-scale GCM-based projected changes in precipitation and temperature are less uncertain over the study region, fine-scale processes are known to influence the distribution of these changes at local scales (Diffenbaugh et al. 2005; Ashfaq et al. 2016), particularly over regions with complex topography. In addition, with respect to Caribbean small islands, it is important to note that some islands are not resolved at the spatial resolution of some of the GCMs (Campbell et al. 2010) used in this study. Therefore, further downscaling of CMIP6 GCMs is recommended before using them to quantify climate change impacts on natural and human systems across the U.S., Central America and the Caribbean.

References

Abatzoglou JT, Williams AP (2016) Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:11770–11775. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1607171113

Akinsanola AA, Kooperman GJ, Pendergrass AG et al (2020) Seasonal representation of extreme precipitation indices over the United States in CMIP6 present–day simulations. Environ Res Lett 15:094003. https://doi.org/10.1088/17489326/ab92c1

Alfaro-Córdoba M, Hidalgo HG, Alfaro EJ (2020) Aridity trends in Central America: a spatial correlation analysis. Atmosphere 11(4):427. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11040427

Almazroui M, Islam MNM, Saeed S et al (2017b) Assessment of Uncertainties in Projected Temperature and Precipitation over the Arabian Peninsula Using Three Categories of Cmip5 Multimodel Ensembles. Earth Syst Environ 1:23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-017-0027-5

Almazroui M, Islam MN, Saeed S et al (2020c) Future changes in climate over the Arabian Peninsula based on CMIP6 multimodel simulations. Earth Syst Environ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-020-00183-5

Almazroui M, Saeed S, Islam MN et al (2017a) Assessment of uncertainties in projected temperature and precipitation over the Arabian Peninsula: a comparison between different categories of CMIP3 models. Earth Syst Environ 1:12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-017-0012-z

Almazroui M, Saeed S, Islam MN, Ismail M (2020a) Projections of precipitation and temperature over the South Asian Countries in CMIP6. Earth Syst Environ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-020-00157-7

Almazroui M, Saeed F, Saeed S et al (2020b) Projected change in temperature and precipitation over Africa from CMIP6. Earth Syst Environ 4:455–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-020-00161-x

Amador, J. A. (2008) The Intra–Americas Seas Low–Level Jet (IALLJ): overview and future research. Ann NY Acad Sci 1146(1): 153–188(36). https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1446.012

Ashfaq M, Bowling LC, Cherkauer K, Pal JS, Diffenbaugh NS (2010) Influence of climate model biases and daily-scale temperature and precipitation events on hydrological impacts assessment: a case study of the United States. J Geophys Res-Atmos. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JD012965

Ashfaq M, Cavazos T, Reboita MS et al (2020) Robust late twenty–first century shift in the regional monsoons in RegCM–CORDEX simulations. Clim Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-020-05306-2

Ashfaq, M., Ghosh, S., Kao, S-C. et al. (2013) Near-term acceleration of hydro climatic change in the western U.S. J Geophys Res-Atmos. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50816

Ashfaq M, Rastogi D, Mei R, et al (2016) High-resolution ensemble projections of near-term regional climate over the continental U.S. J Geophys Res-Atmo. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JD025285

Batibeniz F, Ashfaq M, Diffenbaugh NS et al. 2020) Doubling of U.S. population exposure to climate extremes by 2050. Earth's Future. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EF001421

Becker A, Finger P, Meyer-Christoffer A et al (2013) A description of the global land–surface precipitation data products of the Global Precipitation Climatology Centre with sample applications including centennial (trend) analysis from 1901–present. Earth Syst Sci Data 5:71–22. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-5-71-2013

Bi D, Dix M, Marsland S et al (2012) The ACCESS coupled model: description, control climate and evaluation. Aust Meteorol Oceanogr J 63:41–64. https://doi.org/10.22499/2.6301.004

Bukovsky MS, Carrillo CM, Gochis DJ et al (2015) Toward assessing NARCCAP regional climate model credibility for the North American monsoon: future climate simulations. J Clim 28:6707–6728. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00695.1

Campbell JD, Taylor MA, Stephenson TS, Watson R, Whyte FS (2010) Future climate of the caribbean from a regional climate model. Int J Climatol 31:1866–1878. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.2200

Cao J, Wang B, Yang Y-M et al (2018) The NUIST Earth System Model (NESM) version 3: description and preliminary evaluation. Geosci Model Dev 11:2975–2993. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-2975-2018

Cavazos T, Luna-Niño R, Cerezo-Mota R et al (2020) Climatic trends and regional climate models intercomparison over the CORDEX–CAM (Central America, Caribbean, and Mexico) domain. Int J Climatol 40(3):1396–1420. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.6276

Centella-Artola A, Taylor MA, Bezanilla-Morlot A et al (2015) Assessing the effect of domain size over the Caribbean region using the PRECIS regional climate model. Clim Dyn 44:1901–1918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-014-2272-8

Cerezo-Mota R, Cavazos T, Arritt R et al (2016) CORDEX-NA: factors inducing dry/wet years on the North American Monsoon region. Int J Climatol 36(2):824–836. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.4385

Christensen JH, Kanikicharla KK, Aldrian E et al (2013) Climate phenomena and their relevance for future regional climate change. Climate change 2013: The physical science basis (pp. 1217–1308). Cambridge University Press

Colorado-Ruiz G, Cavazos T, Salinas JA et al (2018) Climate change projections from Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 5 multi-model weighted ensembles for Mexico, the North American monsoon, and the mid-summer drought region. Int J Climatol 38(15):5699–5716. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5773

Cook BI, Mankin JS, Marvel K et al (2020) Twenty–first Century Drought Projections in the CMIP6 Forcing Scenarios. Ear Fut 8, e2019EF001461. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EF001461

Curtis S, Gamble D (2008) Regional variations of the Caribbean mid-summer drought. Theor Appl Climatol 94:25–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-007-0342-0

Diaconescu EP, Mailhot A, Brown R, Chaumont D (2018) Evaluation of CORDEX– Arctic daily precipitation and temperature-based climate indices over Canadian Arctic land areas. Clim Dyn 50:2061–2085. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3736-4

Diallo I, Xue Y, Li Q et al (2019) Dynamical downscaling the impact of spring Western US land surface temperature on the 2015 flood extremes at the Southern Great Plains: effect of domain choice, dynamic cores and land surface parameterization. Clim Dyn 53:1039–1061. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-019-04630-6

Diffenbaugh NS, Swain DL, Touma D (2015) Anthropogenic warming has increased drought risk in California. Proc Nat Acad Sci 112:3931–3936. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1422385112

Duran–Quesada AM, Sorí R, Ordoñez P, Gimeno L (2020) Climate Perspectives in the Intra–Americas Seas. Atmos 11(9), 959; https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11090959

Easterling DR, Kunkel KE, Wehner MF, Sun L (2016) Detection and attribution of climate extremes in the observed record. Weather Clim Extr 11:17–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2016.01.001

Eyring V, Bony S, Meehl GA et al (2016) Overview of the coupled model intercomparison project phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci Model Dev 9:1937–1958. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-1937-2016

Fischer EM, Knutti R (2016) Observed heavy precipitation increase confirms theory and early models. Nat Clim Change 6:986. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3110

Flato G, Marotzke J, Abiodun B et al. (eds) Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 741–866

Fuentes-Franco R, Coppola E, Giorgi F et al (2015) Inter–annual variability of precipitation over southern Mexico and Central America and its relationship to sea surface temperature from a set of future projections from CMIP5 GCMs and RegCM4 CORDEX simulations. Clim Dyn 45:425–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-014-2258-6

Gidden MJ, Riahi K, Smith SJ et al (2019) Global emissions pathways under different socioeconomic scenarios for use in CMIP6: a dataset of harmonized emissions trajectories through the end of the century. Geosci Mod Dev 12:1443–1475. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-1443-2019

Giorgi F, Coppola E, Raffaele F (2018) Threatening levels of cumulative stress due to hydroclimatic extremes in the 21st century. npj Clim Atmos Sci 1, 18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-018-0028-6

Gutjahr O, Putrasahan D, Lohmann K et al (2019) Max Planck Institute Earth System Model (MPI–ESM1.2) for the High-Resolution Model Intercomparison Project (HighResMIP). Geosci Model Dev 12:3241–3281. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-3241-2019

Haensler A, Saeed F, Jacob D (2013) Assessing the robustness of projected precipitation changes over central Africa on the basis of a multitude of global and regional climate projections. Clim Chang 121:349–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0863-8

Hajima T, Watanabe M, Yamamoto A et al (2020) Description of the MIROC–ES2L Earth system model and evaluation of its climate–biogeochemical processes and feedbacks. Geosci Model Dev 13:2197–2244. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-13-2197-2020

Hannah L, Donatti C, Harvey C et al (2017) Regional modeling of climate change impacts on smallholder agriculture and ecosystems in Central America. Clim Change 141:29–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1867-y

Hare B, Roming N, Schaeffer M, Schleussner CF (2016) Implications of the 1.5°C limit in the Paris Agreement for climate policy and decarbonisation. Berlin: Climate Analytics, 25 pp

Harris I, Jones PD, Osborn TJ, Lister DH (2014) Updated high–resolution grids of monthly climatic observations – the CRU TS3.10 Dataset. Int J Clim 34:623–642. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.3711

He B et al (2019) CAS FGOALS–f3–L model datasets for CMIP6 historical Atmospheric Model Inter–comparison Project simulation. Adv Atmos Sci 36(8):771–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-019-9027-8

He C, Li T, Zhou W (2020) Drier North American Monsoon in Contrast to Asian-African Monsoon under Global Warming. J Clim 33(22):9801–9816. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-20-0189.1

Held IM, Guo H, Adcroft A, Dunne JP, Horowitz LW, Krasting J et al. (2019) Structure and performance of GFDL's CM4.0 climate model. J Adv Model Earth Syst 11. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS001829

Hidalgo H, Alfaro E (2015) Skill of CMIP5 climate models in reproducing 20th century basic climate features in Central America. Int J Climatol 35:3397–3421. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.4216

Hidalgo H, Alfaro E, Quesada-Montano B (2017) Observed (1970–1999) climate variability in Central America using a high–resolution meteorological dataset with implication to climate change studies. Clim Chang 141:13–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1786-y

Hidalgo HG, Amador JA, Alfaro EJ, Quesada B (2013) Hydrological climate change projections for Central America. J Hydrol 495:94–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2013.05.004

IPCC (2013) Summary for policymakers. In: Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner G–K, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley PM (Eds.) Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the 5th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press

IPCC (2014) Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Imbach P, Chou SC, Lyra A et al (2018) Future climate change scenarios in Central America at high spatial resolution. PLoS ONE 13:e0193570. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193570

Iturbide M, Gutiérrez JM, Alves LM et al (2020) An update of IPCC climate reference regions for subcontinental analysis of climate model data: definition and aggregated datasets. Earth Syst Sci Data. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-2019-258

Jin C, Wang B, Liu J (2020) Future changes and controlling factors of the eight regional monsoons projected by CMIP6 Models. J Clim 33:9307–9326. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-20-0236.1

Karmalkar AV, Bradley RS, Diaz HF (2011) Climate change in Central America and Mexico: regional climate model validation and climate change projections. Clim Dyn 37:605–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-011-1099-9

Kebe I, Diallo I, Sylla MB, De Sales F, Diedhiou A (2020) Late 21st Century Projected Changes in the Relationship between Precipitation, African Easterly Jet, and African Easterly Waves. Atmosphere 11:353. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11040353

Kendall M (1975) Rank Correlation Methods, 4th ed.; Charles Griffin: London, UK

Knutti R, Sedláček J, Sanderson BM, Lorenz R, Fischer EM, Eyring V (2017) A climate model projection weighting scheme accounting for performance and interdependence. Geophys Res Lett 24:4529–4538. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL072012

Koutroulis AG, Grillakis MG, Tsanis IK et al (2016) Evaluation of precipitation and temperature simulation performance of the CMIP3 and CMIP5 historical experiments. Clim Dyn 47:1881–1898. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-015-2938-x

Lauritzen PH, Nair RD, Herrington AR et al (2018) NCAR release of CAM–SE in CESM2.0: a reformulation of the spectral element dynamical core in dry–mass vertical coordinates with comprehensive treatment of condensates and energy. J Adv Model Earth Syst 10:1537–1570. https://doi.org/10.1029/2017MS001257

Law RM, Ziehn T, Matear RJ, Lenton A et al (2017) The carbon cycle in the Australian Community Climate and Earth System Simulator (ACCESS–ESM1)—Part 1: Model description and pre–industrial simulation. Geosci Model Dev 10:2567–2590. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-10-2567-2017

Lin Y, Huang X, Liang Y et al (2020) Community Integrated Earth System Model (CIESM): Description and Evaluation. J Adv Model Earth Syst 12, e2019MS002036. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS002036

Liu SM, Chen YH, Rao J, Cao C, Li SY, Ma MH, Wang YB (2019) Parallel comparison of major sudden stratospheric warming events in CESM1–WACCM and CESM2–WACCM. Atmos 10:679. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10110679

Lurton T, Balkanski Y, Bastrikov V et al (2020) Implementation of the CMIP6 Forcing Data in the IPSL‐CM6A‐LR Model. J Adv Model Earth Syst 12, e2019MS001940. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS001940

Magaña V, Amador JA, Medina S (1999) The midsummer drought over Mexico and Central America. J Clim 12:1577–1588. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(1999)012%3c1577:TMDOMA%3e2.0.CO;2

Maldonado T, Alfaro EJ, Hidalgo HG (2018) Revision of the main drivers and variability of Central America Climate and seasonal forecast systems. Revista de Biología Tropical 66 (Suppl 1): S153–S175. https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/rbt/article/view/33294

Maloney ED, Camargo SJ, Chang E et al (2014) North American climate in CMIP5 experiments: part III: assessment of twenty–first–century projections. J Clim 27:2230–2270. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00273.1

Mann H (1945) Non–parametric tests against trend. Econometrica 13:245–259

Martínez‑Castro D, Vichot‑Llano A, ·Bezanilla‑Morlot A et al (2018) The performance of RegCM4 over the Central America and Caribbean region using different cumulus parameterizations. Clim Dyn 50, 4103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3863-y

Massonnet F, Ménégoz M, Acosta M et al (2020) Replicability of the EC–Earth3 Earth system model under a change in computing environment. Geosci Model Dev 13:1165–1178. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-13-1165-2020

Mauritsen T, Bader J, Becker T et al (2019) Developments in the MPI-M Earth System Model version 1.2 (MPI-ESM1.2) and its response to increasing CO2. J Adv Model Earth Syst 11:998–1038. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018MS001400

Moreno ML, Hidalgo HG, Alfaro EJ (2019) Cambio climático y su efecto sobre los servicios ecosistémicos en dos parques nacionales de Costa Rica, América Central (Climate change and its effect on ecosystem services in two national parks of Costa Rica, Central America). Revista Iberoamericana de Economía Ecológica, 30(1), 16–38. https://ddd.uab.cat/record/212532

Mote PW, Hamlet A, Clark MP, Lettenmaier DP (2015) Declining mountain snowpack in western North America. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-86-1-39

Nangombe S, Zhou T, Zhang W, Wu B, Hu S, Zou L, Li D (2018) Record‐breaking climate extremes in Africa under stabilized 1.5 °C and 2 °C global warming scenarios. Nat Clim Change 8 (5), 375– 380. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558‐018‐0145‐6

Naz BS, Kao S-C, Ashfaq M, Gao H, Rastogi D, Gangrade S (2018) Effects of climate change on streamflow extremes and implications for reservoir inflow in the United States. J Hydrol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2017.11.027

Oglesby R, Rowe C, Grunwaldt A, Inês F, Ruiz F, Campbell J, Alvarado L, Argenal F, Olmedo B, Castillo A, López P, Matos E, Nava Y, Perez C, Perez J (2016) A high-resolution modeling strategy to assess impacts of climate change for mesoamerica and the Caribbean. Am J Clim Chang 05:202–228. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajcc.2016.52019

Oppenheimer M, Glavovic B et al (2019) Sea level rise and implications for low–lying islands, coasts and communities. IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, H.–O. Pörtner et al., Eds., Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/3/2019/11/SROCC_Ch04-SM_FINAL.pdf

O’Neill BC, Tebaldi C, van Vuuren DP et al (2016) The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci Model Dev 9:3461–3482. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-3461-2016

Pagan BR, Ashfaq M, Rastogi D et al (2016) Extreme hydrological events drive reduction in water supply in the southwestern United Sates. Environ Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/9/094026

Partridge TF, Winter JM, Osterberg EC, Hyndman DW, Kendall AD, Magilligan FJ (2018) Spatially distinct seasonal patterns and forcings of the U.S. warming hole. Geophys Res Lett 45:2055–2063. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL076463

Pincus R, Batstone CP, Hofmann RJP, Taylor KE, Glecker PJ (2008) Evaluating the present–day simulation of clouds, precipitation, and radiation in climate models. J Geophys Res 13:D14209. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JD009334

Pu Y, Liu H, Yan R et al (2020) CAS FGOALS-g3 Model Datasets for the CMIP6 Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP). Adv Atmos Sci 37:1081–1092. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-020-2032-0

Radeloff VC, Helmers DP, Anu Kramer H et al (2018) Rapid growth of the US wildland-urban interface raises wildfire risk. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 115:3314–3319

Rastogi D, Touma D, Evans K, Ashfaq M (2020) Shift towards intense and widespread precipitation events over the United States by mid 21st century. Geophys Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL089899

Rogers JC (2013) The 20th century cooling trend over the southeastern United States. Clim Dyn 40:341–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-012-1437-6

Rong XY, Li J, Chen HM et al (2019) Introduction of CAMS–CSM model and its participation in CMIP6. Clim Chang Res 15(5):540–544. https://doi.org/10.12006/j.issn.1673-1719.2019.186

Ryu JH, Hayhoe K (2014) Understanding the sources of Caribbean precipitation biases in CMIP3 and CMIP5 simulations. Clim Dyn 42:3233–3252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-013-1801-1

Seland Ø, Bentsen M, Seland Graff L et al (2020a) The Norwegian Earth System Model, NorESM2—Evaluation of theCMIP6 DECK and historical simulations. Geosci Model Dev. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-2019-378

Seland Ø. Bentsen M, Olivié D et al (2020b) NorESM2 source code as used for CMIP6 simulations (Version 2.0.1), Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3760870

Sellar A, Jones C, Mulcahy J et al (2019) UKESM1: Description and evaluation of the UK Earth System Model. J Adv Model Earth Syst. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS001739

Semmler T, Danilov S, Gierz P et al (2020) Simulations for CMIP6 With the AWI Climate Model AWI-CM-1-1. J Adv Model Earth Syst. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS002009

Sen PK (1968) Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s Tau. J Am Stat Assoc 63:1379–1389

Sillmann J, Kharin VV, Zhang X, Zwiers FW, Bronaugh D (2013) Climate extremes indices in the CMIP5 multimodel ensemble: Part 1. Model evaluation in the present climate. J Geophys Res Atmos 118:1716–1733. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50203

Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M et al. (2007) Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285085563_Contribution_of_Working_Group_I_to_the_Fourth_Assessment_Report_of_the_Intergovernmental_Panel_on_Climate_Change

Song Y, Li X, Bao Y et al (2020) FIO-ESM v2.0 Outputs for the CMIP6 Global Monsoons Model Intercomparison Project Experiments. Adv Atmos Sci 37:1045–1056. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-020-9288-2

Srivastava AK, Richard G, Paul AU (2020) Evaluation of historical CMIP6 model simulations of extreme precipitation over contiguous US regions. Wea Clim Extr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2020.100268

Swart NC, Cole JNS, Kharin VV et al (2019) The Canadian Earth System Model version 5 (CanESM5.0.3). Geosci Model Dev 12:4823–4873. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-4823-2019

Séférian R, Nabat P, Michou M et al (2019) Evaluation of CNRM Earth-System model, CNRM-ESM2-1: role of Earth system processes in present-day and future climate. J Adv Model Earth Syst 11:4182–4227. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS001791

Tatebe H, Ogura T, Nitta T et al (2019) Description and basic evaluation of simulated mean state, internal variability, and climate sensitivity in MIROC6. Geosci Model Dev 12:2727–2765. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-2727-2019

Taylor MA, Clarke L, Centella A et al (2018) Future Caribbean Climates in a World of Rising Temperatures: the 1.5 vs 2.0 Dilemma. J Clim 31:2907–2926. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-17-0074.1

Taylor KE, Stouffer RJ, Meehl GA (2012) An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 93(4):485–498. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-11-00094.1

Taylor M, Alfaro E (2005) Climate of Central America and the Caribbean. In: Encyclopedia of World Climatology: pp.183–189. Netherlands: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-3266-8-37

Torres-Alavez A, Cavazos T, Turrent C (2014) Land–sea thermal contrast and intensity of the North American monsoon under climate change conditions. J Clim 27:4566–4580. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00557.1

UNFCCC (2015) Adoption of the Paris Agreement. New York, NY: UNFCCC. Report number: FCCC/CP/2015/L.9/Rev.1. http://unfccc.int/ resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf

Veas–Ayala N, Quesada–Román A, Hidalgo HG, Alfaro EJ (2018). Humedales del Parque Nacional Chirripó, Costa Rica: características, relaciones geomorfológicas y escenarios de cambio climático (Chirripó National Park wetlands, Costa Rica: characteristics, geomorphological relationships, and climate change scenarios). Revista de Biología Tropical, 66(4), 1436–1448. https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/rbt/article/view/31477

Vichot-Llano A, Martinez-Castro D, Bezanilla-Morlot A, Centella-Artola A, Giorgi F (2020) Projected changes in precipitation and temperature regimes over the Caribbean and Central America using a multiparameter ensemble of RegCM4. Int J Clim. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.6811

Vichot-Llano A, Martinez-Castro D, Giorgi F et al (2020) Comparison of GCM and RCM simulated precipitation and temperature over Central America and the Caribbean. Theor Appl Climatol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-020-03400-3

Voldoire A, Saint‐Martin D, Sénési S et al (2019) Evaluation of CMIP6 DECK experiments with CNRM‐CM6‐1. J Adv Model Earth Syst 11, 2177–2213. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS001683

Volodin E, Gritsun A (2018) Simulation of observed climate changes in 1850–2014 with climate model INM-CM5. Earth Syst Dyn 9:1235–1242. https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-9-1235-2018

Volodin EM, Mortikov EV, Kostrykin SV et al (2018) Simulation of the modern climate using the INM–CM48 climate model. Russian J Num Analy Math Model 33(6), 367–374. https://doi.org/10.1515/rnam-2018-0032

Wang B, Biasutti M, Byrne M et al (2020) Monsoon climate change assessment. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-19-0335.1

Wang B, Jin C, Liu J (2020) Understanding Future Change of Global Monsoons Projected by CMIP6 Models. J Clim 33(15):6471–6489. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-19-0993.1

Wang C, Zhang L, Lee SK, Wu L, Mechoso CR (2014) A global perspective on CMIP5 climate model biases. Nat Clim Change 4:201–205. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2118

Wehner M, Gleckler P, Lee J (2020) Characterization of long period return values of extreme daily temperature and precipitation in the CMIP6 models: Part 1, model evaluation. Weather Clim Extre 30:100283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2020.100283

Wehner MF, Reed KA, Li F et al (2014) The effect of horizontal resolution on simulation quality in the Community Atmospheric Model, CAM5.1. J Adv Model Earth Syst 6, 980–997. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013MS000276

van der Wiel K, Kapnick SB, Vecchi GA et al (2016) The resolution dependence of contiguous U.S. Precipitation extremes in response to CO2 forcing. J Clim 29:7991–8012. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0307.1

Wilks, D. (2019) Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences. 4th. ed. Elsevier

Willmott CJ, Robeson SM, Matsuura K, Ficklin DL (2015) Assessment of three dimensionless measures of model performance. Environ Model Soft 73:167–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2015.08.012

Wu T, Lu Y, Fang Y et al (2019) The Beijing Climate Center Climate System Model (BCC–CSM): the main progress from CMIP5 to CMIP6. Geosci Model Dev 12:1573–1600. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-1573-2019

Wyser K, Kjellström E, Koenigk T et al (2020) Warmer climate projections in EC-Earth3-Veg: the role of changes in the greenhouse gas concentrations from CMIP5 to CMIP6. Environ Res Lett 15(5):054020. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab81c2

Yukimoto S, Kawai H, Koshiro T et al (2019) The Meteorological Research Institute Earth System Model version 2.0, MRI–ESM2.0: Description and basic evaluation of the physical component. J Meteor Soc Japan 97:000–000. https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2019-051

Acknowledgements

This research work was supported financially by the Center of Excellence for Climate Change Research, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The authors thank the World Climate Research Program for making the CMIP6 dataset available for global and regional scale climate research. The authors also thank the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) for archiving and providing free access to the CMIP6 dataset. The CRU, GPCC and UoD datasets were obtained from their websites. The computation work and data analysis were performed on the Aziz Supercomputer at King Abdulaziz University's High–Performance Computing Center, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. EA and HH thanks to UCR project B9-454 for give them time for research. ID was supported by the U.S. NSF Grant AGS-1849654. MB was supported by the U.S. NSF Grant AGS-1623912. MA was supported by the Strategic Partnership Project, 2316‐T849‐08, between DOE and NOAA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest between the authors and the journal.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Almazroui, M., Islam, M.N., Saeed, F. et al. Projected Changes in Temperature and Precipitation Over the United States, Central America, and the Caribbean in CMIP6 GCMs. Earth Syst Environ 5, 1–24 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-021-00199-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-021-00199-5