Abstract

This study explores the use of discourse markers (DMs) in metadiscursive activities such as word searches, repairs or metalinguistic evaluations that occur during spontaneous oral production. The analysis is based on a corpus of telephone conversations between advanced learners and native speakers of French and draws on functional as well as on interactional work on DM. In a first step, three selected learner profiles provide insight, by means of sequence analysis, into how individual learners make use of their particular DM inventory for their utterance planning, carrying out repairs and expressing attitudes toward their oral production. In a second step, the study compares native and non-native speaker’s DM inventories in order to detect general tendencies in the learners’ DM use that differ from the native speakers’ use of DMs. The comparison of the profiles shows that, even if there is relatively little agreement among the learners regarding the concrete lexical forms of the DMs, similarities can be discerned regarding the interlinguistic characteristics (e.g. individual preferences and overuse in the form of “lexical teddy bears” such as oui, alors or voilà, underuse of typical French reformulation markers like enfin, and weak routine in the lexicalisation of metadiscursive comments).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Discourse production in oral conversation is a complex task, determined by the temporality of speaking, i.e. its linear, transitory and irreversible character, as well as by its dialogic and collaborative nature. What a speaker plans to say has to be lexically and grammatically encoded and linearized. The recipient of the utterance has to meet the discourse expectations, taking into account what has preceded the utterance and projecting what is to follow. Finally, the result of this process may be retrospectively negotiated or commented on by the speaker or by his/her interlocutor. Hence, speech is constantly accompanied by metadiscursive activities that structure and comment on the discourse production. In L2 discourse, metadiscursive activities have a twofold problem. On the one hand, speakers are more likely to face communicative difficulties in L2 than in L1, so that metadiscursive activities are particularly necessary to deal with problems concerning the retrieval of lexical and grammatical information, to negotiate understanding and to achieve the intersubjectivity of talk. On the other hand, the act of engaging in metalinguistic activities itself requires particular linguistic and communicative skills that allow the speaker to indicate problems, to hold the floor while searching for a word or to manage repairs. While native speakers have at their disposal routinized devices such as discourse markers (DMs) and other routine formulae, it has been shown that these routines are not yet available in the early stages of acquisition and appear relatively late and with a restricted repertoire in the later stages of this process (cf. Bartning and Schlyter 2004:296). In view of this twofold problem of learner discourse, we are particularly interested in the role of DMs as one type of communicative routines that are used within metadiscursive activities. The focus of our study is oral discourse produced by German university students of French from intermediate to advanced levels (B2/C1). The study explores the use of DMs in L2 French that are involved in metadiscursive activities. Based on the analysis of three selected learner profiles as well as on an overview of DMs in ten different learners in comparison to native speakers, it aims at delivering qualitative insights into the DM repertoires and the individual strategies that enable metadiscursive activities in L2. In the following, we will first outline what we understand by metadiscursive activities and which role DMs play within these activities (Section “Discourse Production, Metadiscursive Activities and Metalinguistic Functions of Discourse Markers”). Subsequently, we will present a brief review of several approaches to L2 acquisition that deal with metalinguistic activities from interactional and functional points of view (Section “Research on Metadiscursive Activities and Discourse Markers in L2”). Having presented the methodological approach of the study (Section “Aims and Method”), we will summarize the results of the analysis concerning individual learner profiles and the differences between native speakers’ and non-native speakers’ DM inventories (Section “Results”). Finally, the results of the different parts of the study will be discussed in Section “Discussion”.

Discourse Production, Metadiscursive Activities and Metalinguistic Functions of Discourse Markers

Discourse production is understood in this contribution as an on-line production (Auer 2009) which is determined by the linearity of spoken language in time, i.e. by its transitoriness, its irreversibility as well as by the synchronization of the production and the reception process in interaction. Thus, discourse production has to be regarded as a collaborative task and a joint accomplishment.

In their seminal work on oral text production in French, Gülich and Kotschi (1995) distinguish three types of phenomena that are related to different aspects of discourse production. The first type comprises unfilled and filled pauses (euh), correction markers (e.g. (en)fin), cut-offs and restarts, sound stretchings and recyclings of parts of the utterance that indicate planning problems such as word searches (cf. Gülich and Kotschi 1995:36). The second type forms part of the operations that Schegloff et al. (1990) describe as “repair”. Participants can “go back” to a previously uttered piece of talk in order to work on it again. A wrong or unclear expression, for example, is then marked as a “trouble source” and can subsequently be revised by a second expression that represents a correction, specification, paraphrase, elaboration or summary, etc. of the first expression. As such, this procedure is also called “replacement repair” (cf. Kitzinger 2013:234ff.). In this context, DMs such as c’est-à-dire, en fait, après tout, among others, play an important role as repair prefaces (i.e. indicators of repair activities, cf. Kitzinger 2013:240). In this contribution, we will refer to this type of procedures as “reformulation”. Finally, participants may also comment on their own or others’ linguistic production without revising or replacing it. This type of procedures forms part of the most explicit category of metadiscursive activity, including metalinguistic comments, evaluations or hedgings, and consists of fixed expressions (e.g. comment dirais-je, entre guillemets) or spontaneous formulations (e.g. c’est jolie votre expression, cf. Gülich and Kotschi 1995:59).

In this study, we are concerned with the role of DMs within different types of metalinguistic activities. DMs are considered an important resource for the accomplishment of the latter without being identical to them. DMs constitute “a broad, extremely heterogeneous class of items with fuzzy boundaries” (Fischer 2014:288). From a formal point of view, they are elements of various length and complexity that mostly have ‘counterparts’ in different word classes and linguistic units, such as adjectives (bon), adverbs (bien, alors) or verbal syntagms (tu sais), from which they evolved by the process of pragmaticalizationFootnote 1 and with which they coexist. As DMs, these elements are prototypically uninflected, positionally variable, not syntactically integrated and syntactically and semantically optional. DMs are mostly defined as a functional class. Rather than propositional meaning, DMs have procedural meaning inasmuch as they help the interlocutors to manage the conversational flow, deal with online discourse production tasks and collaborate in the creation of common ground (cf. Bazzanella 2006; López Serena and Borreguero Zuloaga 2011; Fischer 2014; Borreguero Zuloaga 2015).

When we deal with the metadiscursive function of DMs in the following, we do not assume the existence of a (closed) class of specialized markers. Given the polyfunctional nature of DMs, we instead take the different classes of functions that DMs can fulfil as a starting point. The metadiscursive (macro)function “gathers together all the functions related to text building and production” that can be divided into “functions related to the organization of textual information” and “functions related to the linguistic formulation of the text” (Borreguero Zuloaga et al. 2017:21). In this contribution, we are particularly interested in the latter function, i.e. the use of DMs related to the online planning of oral discourse. We consider DMs as one resource among others that participants deploy in order to keep the floor during searches for words, to indicate and to manage repairs as well as to negotiate and express attitudes towards the result of the production process.

As has been argued above, DMs represent an open class with fuzzy boundaries. We start from the assumption that there is no possible clear-cut distinction between DMs and other forms and expressions fulfilling the same function, but that we have to deal with differences concerning the degree of semantic bleaching and formal (in)variance, or, in short, pragmaticalization. This is particularly true for DMs in L2 where forms may be used like or as DMs that do not exist as DMs in native speaker corpora. As has been shown by Diao-Klaeger and Thörle (2013) and Thörle (2015, 2016), linguistic expressions such as oui can be used in L2 in a DM-like way without being a typical DM of native French. For this reason, the study of discourse markers within metalinguistic activities in L2 will not be restricted to a predetermined set of forms. Instead, all linguistic expressions that indicate the learners’ metalinguistic activities and show DM-like characteristics will be taken into account.

Research on Metadiscursive Activities and Discourse Markers in L2

In L2 research, metadiscursive activities and the metadiscursive function of markers have been studied from several angles, determined by the theoretical background and the specific research interests of the respective approaches. In the following section, two approaches that are particularly relevant to the purpose of this study will be discussed: approaches on form-function-relations and interactional approaches.

Approaches on Form-Function-Relations

These approaches focus on the development of form-function-relations in learners’ DM repertoires that can be observed across various proficiency levels and contrasted with native speakers’ DM use. DMs in L2 differ from native-like uses in the target language. This means that the repertoire of DMs in L2 cannot be described via lexicographic compilations of L1 DMs. Therefore, Jafrancesco (2015:3ff.) as well as Borreguero Zuloaga et al. (2017:20–23) propose a function-based identification of DM forms in L2, which aims to ascertain which discursive functions are activated in the L2 and which DMs—if any—are chosen to carry out these functions (onomasiological approach). In contrast, the semasiological approach starts from the linguistic form and asks for the different functions an individual DM fulfils in discourse. As such, by combining both approaches, it is possible to identify forms and their functional description in a cyclical analysis (cf. Koch 2016:160f.). This is particularly necessary for the identification of the specific use of DMs in L2. Compared to DMs in L1, the inventories of DMs in L2 may contain rather uncommon forms due to interference from L1 or other languages and resulting from individual creations. Kerr-Barnes (1998:205) emphasizes the highly idiosyncratic nature of learners’ DM use as well as a “repetition effect” favoring the reoccurrence of a marker that frequently appeared in the preceding discourse. In some cases, the characterization of forms as DMs is debatable as they do not fulfil the criteria of semantic loss and formal invariance like prototypical DMs, but instead seem like “complex metalingual utterance[s]” (Maschler 2009:30). However, they are not newly constructed formulations, and can be considered to be “conventional sequences” or “formulaic chunks” (Forsberg 2010:25f.).

The results of studies focusing on several L2 (e.g. Hancock 2000 for French; Borreguero Zuloaga et al. 2017 and Jafrancesco 2015 for Italian; Pascual Escagedo 2015 for Spanish) indicate that, in comparison to native speakers’ repertoires, there is a relative lack of diversity of forms used with a metadiscursive function, such as reformulation indicators, markers of uncertainty, evaluation or self-affirmation, although an increasing variety of forms can be observed during the acquisition process. Beginners tend to employ fewer types of DMs and apply these to fulfil various functions, i.e. in a polyfunctional way. Advanced learners have a more precise and distinctive DM repertoire at their disposal. However, the approximation to the target language seems to be limited. There is always a certain range of DMs used by native speakers that is completely lacking or rarely observed in L2, even at higher proficiency levels (e.g. fr. donc, enfin, c’est-à-dire in Hancock 2000:64; it. come dire, diciamo, ecco, insomma in Borreguero Zuloaga et al. 2017:48). It is remarkable that even at the highest levels of proficiency, non-native speakers have not appropriated the full pragmatic range of DMs so that the latter constitutes a sort of “fragile zone” (cf. Fant 2018:80).Footnote 2 This limitation can be interpreted as a fossilization process that, by the way, affects not only the lexical level but also the prosodic and the functional level (cf. Romero Trillo 2002; Borreguero Zuloaga et al. 2017:17).

The strength of these approaches is the description of how L2 structures differ from L1 speakers of the target language. This can lead, for example, to a clearer perception of needs in the language learning process and foster the development of approaches for learning and teaching DMs in the classroom. A general problem with several descriptions of form-function-relations that we intend to address in this contribution is the supposed gap between summaries of L2 DM use and individual particularities. L2 characteristics are often influenced by learners’ L1 and interlanguage phenomena, and learners of the same L1 may display similarities in their DM use, but this does not mean that their usage is uniform. Therefore, the following analysis aims to go beyond the comparison of inventories and form-function-relations of DMs in native speakers and non-native speakers by investigating how cross-individual variation, e.g. concerning the inventory of concrete DMs, relates to generalizable characteristics of DM use in L2.

Interactional Approaches

While the approaches in 3.1. focus on the development of form-function-relations in L2 in comparison to native speakers’ DM use, the analytic focus of interactional approaches to metadiscursive activities in L2 is on social practices and interactional competence rather than on language form and language proficiency. Research in this field analyzes learners’ conduct as a situated behaviour in interaction that is sensitive to the local contingencies of social practice. Relying on ethnomethodological principles, researchers are therefore concerned with naturally occurring data that is audio- or video-taped and described in a purely qualitative sequential analytic way, i.e. turn by turn, from an emic perspective (cf. e.g. Pekarek Doehler 2013).

Studies on metadiscursive activities that adopt the CA-for-SLA approach have shown that interactional competence cannot simply be transferred from L1 to L2. Learners’ techniques for repair or word searches develop over time, becoming subtler and more diversified and thus permitting increased progressivity of talk (Renaud and Rubio Zenil 2010; Farina et al. 2012; Pekarek Doehler and Pochon-Berger 2015).

More recent interactional linguistic studies focus on the emergence of constructions in L2 interaction. In a longitudinal study on word searches in French L2, Pekarek Doehler (2018) analyzes the grammaticalization process of the metadiscursive expression comment on dit (‘how do you say’). This expression evolves during an advanced learner’s stay abroad from an overt call for help to a routinized display of cognitive searching, allowing the speaker to ‘buy time’ while searching for the target item. Furthermore, interactional studies are interested in problem-solving activities, such as word searches and repairs, in native-non-native speaker interaction as opportunities for learning in non-pedagogic communication (Gülich 1986; De Pietro, Matthey and Py 1988; Gajo and Mondada 2000; Brouwer 2003; Thörle 2017).

Although the focus of the interactional approach is not on linguistic forms, nevertheless it appears very useful for the study of DMs in L2. The analysis of how metadiscursive activities are carried out in the concrete sequential context can provide insight into the role DMs and other linguistic and non-linguistic devices play in the accomplishment of these activities, and into how particular DMs emerge in social interaction as a resource for the organization of talk in social interaction.

Aims and Method

The present study aims to describe advanced learners’ DM use within metadiscursive activities in French L2. In order to achieve this, the types of DMs that fulfil metadiscursive functions, the kind of metadiscursive activities in which these forms are involved, and the formal and functional properties they show will be analyzed. The study will focus on individual learner profiles, considering the idiosyncratic nature of DM use in L2 and the concrete metadiscursive activity as well as the sequential context in which a form occurs. Furthermore, the learners’ inventory will be compared to the native speakers’ repertoire in order to show the peculiarities of the DM use in L2 and to determine the extent to which this use relies on individual learner strategies and shows general features.

The research questions can be resumed as follows:

-

Which inventories of DMs are used by non-native speakers in order to fulfil metadiscursive functions?

-

How do these inventories relate to

-

the overall DM repertoire of the respective learners,

-

the DMs used by native speakers?

-

-

Which formal and functional properties do DMs used within metadiscursive activities show

-

•

in the individual profile,

-

•

across several individual profiles?

-

•

Data Corpus

The present analysis is based on a corpus of 10 simulations of telephone conversations between native speakers of French and 10 different advanced learners of French with the general proficiency levels of B2 or C1. The participants in this task-based approach (cf. also Forsberg and Fant 2010) are young adults with German L1 who are studying French in a philological degree program. Each conversation has a duration of 7–17 min (the total of all the conversations is 1 h 54 min) and deals with getting information on stay abroad options in France. The participants are asked to call a language school to find out about French language courses or about the possibility of working as an au pair during the summer holidays. These topics were chosen due to their relevance to the students’ academic environment and connection to real-life contexts. The interlocutors were native speakers of French, either working at a language school or parents who were looking for possible au pairs. All the participants were briefed about the simulated character of the call. Audio or video recordings were taken in an undisturbed office on campus where the informant was left alone with the recorder and the telephone number of the interlocutor. All conversations have been transcribed according to the GAT 2 system for conversation analysis.Footnote 3 The chosen conversations are part of our corpus of spoken French and Spanish by advanced L2 speakers with a total length of 17 h.

The Focus on Learner Profiles

In the first step, three conversations will be highlighted for a more detailed profile analysis (Table 1). The learner profiles inform about

-

the learner’s overall DM inventory,

-

the learner’s inventory of DMs fulfilling metadiscursive functions,

-

the way the learner makes use of particular DMs of his/her inventory.

The inventories presented in the following sections are based on the broad understanding of DMs (see Section “Discourse Production, Metadiscursive Activities and Metalinguistic Functions of Discourse Markers”). Adopting an onomasiological approach (cf. Borreguero Zuloaga 2015:16), all linguistic forms and expressions that fulfil metadiscursive functions and show DM-like characteristics (i.e. procedural rather than propositional meaning, semantic bleaching, prosodic backgrounding, weak degree of syntactical integration) will be taken into account.

The inventories distinguish between displays of planning problems, reformulation indications and metadiscursive evaluations (e.g. hedges). The three learner profiles are presented in Section “Profile JM”, “Profile FH” and “Profile DV”. In a second step, the analysis will be extended to the entire corpus. All forms and expressions used with discourse-marking functions will be identified for each of the ten conversations, distinguishing, on the one hand, between items with discourse-marking function in general and items with metadiscursive functions in particular and, on the other hand, between those markers used by the learner and those used by his or her native interlocutor. In Sects. “Overview: DMs Used in L2” and “Comparison of DMs Used in L1 and in L2” we will present a summary of these items in order to give an overview of the DM inventory of the learners compared to the native speakers’ inventory.

Results

Profile JM

JM started learning French at school when she was 15 years old. At the moment of the recording she is a university student enrolled in a degree program for future teachers of French as a foreign language. She speaks fluently with a speech rate of 121.3 words/min. Several kinds of metadiscursive activities are observable in her conversation: displays of the planning process, corrective and paraphrastic self-reformulations as well as a number of metadiscursive commentaries. The native interlocutor intervenes in JM’s (re)formulation processes several times by coproducing parts of the utterance (cf., e.g. Lerner 2002, Thörle 2017). DMs are involved in all of these activities, as will be shown below.

Repertoire

Table 2 shows the range of forms and expressions used by the informant during the telephone call that fulfil discourse marking functions in general and metadiscursive functions in particular.

JM has a relatively rich DM repertoire which contains the most frequent DMs of the L1 corpus, such as alors, ben, donc, et, mais, oui, voilà, and among them those DMs that are less frequent in the overall L2 corpus, such as donc and voilà (see Section “Overview: DMs Used in L2”). Apart from standard French DMs, the repertoire includes the German form aber (‘but’), which is used once in the conversation, and the form au fin, which is most likely a phonetically erroneously interpreted form of enfin (‘well’), as a repair marker. The DMs au fin (‘enfin’), ben, et donc, non, ou, oui, voilà are used with metadiscursive functions as well as ah, oh and a range of more complex expressions. Their use will be described in the following sections.

DMs Marking the Planning Process

JM’s utterances contain all kinds of procedures displaying the planning process, such as filled and unfilled pauses, sound stretchings, word recyclings, cut-offs, and restarts. Filled pauses are realized as euh or euhm, i.e. by using a mid-central vowel similar to [œː], which comes near to native speakers’ realization. The informant also makes use of DMs that display the planning process. Table 3 shows the number of DMs JM uses throughout her 30 turns within the conversation.

JM’s turns are relatively long and often extend over several turn constructional units (cf. Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson 1974).Footnote 4 The only DMs used at the turn beginningFootnote 5 are oui (3 times) and ben (twice). In addition, seven change of state-tokens (cf. Heritage 1984), such as ah or oh, are used.Footnote 6 In the ongoing turn, JM uses oui, voilà, et donc, ou, au fin [sic!] and non to mark the planning process of her utterance. Examples 1 and 2 illustrate the use of the most frequently occurring DM, oui and voilà (N = native speaker, L = learner).

Example 1: JM’s use of oui in the planning process

In ll. 2, 5 and 17 oui co-occurs with several hesitation phenomena. In l. 2 oui marks the cut-off of the construction after ce and the restart with j’aimerais bien savoir. In l. 5 oui occurs after a sound-stretching (e:t), a filled pause, and later, in ll. 16–18, within a number of hesitation phenomena (filled pauses, click of the tongue). The marker has no affirmative function in these cases. This becomes clear in l. 17 where oui is followed by non. JM cancels the word search or rather delays it until later (d’après/après). A similar observation can be made in Example 2.

Example 2: JM’s use of voilà in the planning process

In l. 3 the ongoing utterance construction is interrupted after the preposition pour (possibly due to the overlapping backchannel signal oui, which is simultaneously uttered by the interlocutor in l. 2). At this point, JM uses voilà before repeating the preposition and continuing with the utterance. This use of voilà does not seem to have its usual functions as a presentative/deictic, agreement/confirmation or conversation-structuring marker (cf. Bruxelles and Traverso 2006). Instead, its function seems to be to overcome the punctual disturbance of the production process, possibly triggered by the overlap.

Reformulation

JM initiates four reformulations in her conversation (self-initiations). Three of these are realized by herself (self-reformulation), while one is realized by her interlocutor (other-reformulation). Three reformulations are corrections; one reformulation is a paraphrase that states more precisely what was said before (donc ça veut dire). For the initiation of these reformulations she uses the forms and expressions shown in Table 4.

The forms and expressions used to initiate a correction contain the idea of alternative (ou), replacement (ne pas… mais…) or negation (non). Only the form ou is also used in the L1 part of the corpus (see below in Section “Comparison of DMs Used in L1 and in L2”). The expression donc ça veut dire is used in a literal sense and introduces an explicative paraphrase. The expressions mentioned in the table are combined with metadiscursive commentaries or displays of the planning process in most of the cases so that JM’s initiations of reformulations seem somewhat labored as it is illustrated by Example 3.

Example 3: JM’s initiation of a reformulations

In l. 4, JM has difficulty articulating the word pratiquer. The first syllable of the word is repeated before the second syllable is realized incorrectly (*practiquer). JM then articulates the first syllable again but breaks off and rejects it with non. She indicates a word search, which is signalled by several insecurity expressing devices: an overt metalinguistic question (comment on dit ça), clicks of the tongue,Footnote 7 the interjection o:h and the expression ouh là là LE françaisFootnote 8 as well as laughing. Only then does she produce the correct form pratiquer, which corrects and replaces the former practiquer and continues her utterance. This reformulation appears relatively labored due to the fact that it involves an extensive word search.

Hedges and Metalinguistic Comments

JM makes a range of metalinguistic comments in her conversation using the following expressions: je dirais, je voulais dire et on dit. We will comment particularly on the use of je voulais dire and on dit. The latter shows an interesting interlinguistic feature (Example 4).

Example 4: JM’s use of hedges and metalinguistic comments

In this extract the participants are negotiating the date on which JM will begin to work as an au pair. JM has been asked when she could come to France. Her answer is an excellent illustration of the incremental nature of oral discourse production. In l. 1 she answers that she could leave on 30th July. In ll. 5–8, she ratifies her answer and indicates the closing of her turn using the DM voilà, c’est ça, oui. However, in l. 9 the answer is extended and slightly modified by stating more precisely that 30th July is the earliest possible date of her arrival. This extension is introduced by German aber (‘but’) and retrospectively framed as a clarification of the former utterance by the expression je voulais dire, which can be understood as a literal metatextual comment in this context. Nevertheless, je voulais dire is articulated with accelerated pace and softer voice than the environment and thus is prosodically backgrounded. In addition, it shows a low degree of syntactical integration in the preceding part of the utterance so that its use comes close to that of a DM, working here as a post-positioned repair marker.Footnote 9

In l. 12, JM slightly modifies the content of her answer again, suggesting 29th July as a possible arrival day. She continues with mais pas-, breaks off and restarts with c’est (.) c’est le maximum. This syntactically and prosodically complete utterance is then extended in l. 15 by on dit, which we interpret as a possible ad hoc-transfer JM makes on the basis of German sagen wir. It is also a possible approximation to a target language expression that is not fully acquired by the informant. The French routine formula would be the marker disons, which can be found in the L1 part of the corpus. Both markers, German sagen wir and French disons, are generally classified as repair markers (cf. Pfeiffer 2015:295f.; Saunier 2012). Unlike other French repair markers, disons can express compromise (cf. Saunier 2012), which also applies to sagen wir in German and which seems to be the case for on dit as used by JM, as the earlier arrival date can be understood as a concession to the host family. Interestingly, JM uses both markers, je voulais dire and on dit, retrospectively, i.e. after the expression they refer to. Please also note that voilà, one of JM’s preferred DMs, is used in this example (ll. 5–8) with a discourse-structuring function, concluding her explanations about the duration of her stay. It illustrates again the polyfunctional use JM makes of this DM.

In sum, JM has a relatively large inventory of forms and expressions fulfilling metadiscursive functions. However, particular forms within this repertoire, namely oui and voilà, are used more often than others to indicate planning problems. As for the initiation of reformulations, JM uses non, ne pas… mais… and ou, i.e. forms that indicate by their original lexical meaning the ideas of cancellation or alternative. JM comments frequently on her own oral production, using metalinguistic hedges and comments. These do not always correspond to the markers native speakers would use, but can be interpreted as an approximation to those (e.g. on dit with the function of disons).

Profile FH

FH started learning French at school when she was 13 years old. Like JM she is a university student enrolled in a degree program for future teachers of French as a foreign language. Her speech rate is, at 91.8 words/min, lower than JM’s. The metadiscursive activities observed in her conversation are mainly displays of planning problems as well as some reformulations. In several instances the function of the latter is to negotiate understanding and thus achieve intersubjectivity. For example, FH initiates a reformulation of the interlocutor’s utterance that she has not understood when it was uttered the first time or corrects an utterance of the interlocutor in order to rectify false assumptions and to prevent further misunderstanding. Compared to JM, metadiscursive comments can hardly be observed in FH’s conversation.

Repertoire

Table 5 shows the range of forms and expressions fulfilling metadiscursive and other discourse marking functions used by the informant during the telephone call.

FH’s repertoire contains the most frequent DMs of the L1 corpus, such as alors, bon, d’accord, et, mais, oui, voilà (see Section “Comparison of DMs Used in L1 and in L2” below), but she does not use donc and et puis. The forms oui, alors, non, ou and comment? are used with metadiscursive functions. Only oui, alors and ou are used in the L1 corpus, too. Typical reformulation markers of French, such as c’est-à-dire or enfin, are not used by FH. Table 5 shows a smaller range of forms for FH when compared to the other participants. However, this result might also be explained by the fact that the recording for FH is shorter than the other two (see Table 1).

DMs Marking the Planning Process

FH’s utterances contain all kinds of hesitation phenomena, such as filled and unfilled pauses, sound stretchings, recyclings, cut-offs, and restarts. Filled pauses are realized as äh or ähm, i.e. by using a rather open-mid vowel similar to [ɛː], which is similar to the way hesitation is realized in German compared to French euh/euhm with [œː], which we use as the standard forms in the transcriptions. The informant makes also use of DMs that mark the planning process. These are represented in Table 6.

FH takes 33 turns during the conversation. Her turns are shorter than JM’s.Footnote 10 Besides the backchannel signals d’accord and oui that are not counted in the table, four elements are used at the turn beginning: ah, alors, mais, and non (one occurrence respectively). In most of her turn beginnings FH does not use any DMs. During the ongoing turn, FH uses oui and alors in order to display planning processes. Example 5 shows the use the informant makes of these forms.

Example 5: FH’s use of alors and oui in the planning process

Typically for FH, the answer to the question of N starts with a filled pause. In l. 4 she interrupts the construction of her utterance after je pense que-. As for the prosodic features, je pense que- does not represent a complete gestalt, as the intonation phrase remains unfinished. At this point, alors, preceded by a hearable inhalation, marks the resumption of the utterance construction. Note that the second alors in l. 8 has a discourse-structuring function, opening FH’s question. As such, it illustrates the polyfunctional way in which alors is used by FH, both for discourse planning and for discourse structuring. In l. 7 a planning problem occurs after ce cours. The informant copes with it by uttering a filled pause, a pause after c’est and the DM oui followed by the repetition of c’est, which is subsequently reformulated again by ça (…). Thus, in this excerpt oui and alors are devices by which the informant overcomes disturbances of the utterance planning.

Reformulation

FH realizes two self-reformulations. In addition, she reformulates an utterance of her interlocutor and finally initiates one self-reformulation of the interlocutor. Three of the four occurrences are corrections. For the initiation of the reformulation, a range of forms is used (ou, non, comment) that semantically express the ideas of alternative, negation or mode (Table 7). Only the form ou is also used in the L1 part of the corpus.

Example 6 illustrates how a self-reformulation is realized.

Example 6: FH’s self-reformulation

The production of FH’s answer is characterized by several hesitation phenomena marking the planning process: filled pauses, recyclings, cut-offs and restarts as well as the use of oui as a filler. In ll. 11 to 13, the word étudier (‘to study’) is corrected and replaced by enseigner (‘to teach’). This correction is relatively labored. FH combines ou with several hesitation phenomena as well as with non comment, which is articulated with a softer voice and prosodically backgrounded. Using these DM-like devices, FH rejects the precedent expression and indicates her cognitive search (cf. also Pekarek Doehler and Berger 2019:64, who interpret comment- in their L2-corpus as a cut-off word-search marker from comment on dit). Finally, the DM oui marks the “result” of the correction process.

In sum, FM shows a relatively small DM inventory in comparison to JM. These DMs are used in a polyfunctional way, indicating, for example, discourse structuring and/or discourse planning (alors). The clearly preferred marker within the planning process is oui. Reformulations are indicated by several forms that express the ideas of alternative (ou), cancellation (non) or mode (comment) and are mostly concerned with corrections in order to prevent misunderstandings.

Profile DV

The male student DV is an advanced learner of French who has recently returned from a nine-month Erasmus exchange in France. He has a relatively high speech rate of 131.7 words/min and estimates his proficiency level as C1. In this profile analysis, we mainly focus on the DM alors that DV uses most frequently and on the reformulation strategy with ou.

Repertoire

Table 8 shows the range of DMs used by the informant during the telephone call.

DV’s repertoire also contains frequent DMs that are found in the L1 corpus (alors, bon, d’accord, et, mais, oui, voilà), whereas the frequent marker donc does not appear.

DMs Marking the Planning Process

DV applies similar strategies in the planning process as the other informants. The DMs used in the planning processes are shown in Table 9.

DV takes 28 turns during the conversation. His turns—again, without counting pure backchannel signals—are generally longer than in the other phone calls due to the subject: DV narrates his experiences from his time in France and gives much more information than the other informants do in their conversations. In the ongoing turn, the use of alors dominates DV’s speaking as Example 7 shows.

Example 7: DV’s use of alors in the planning process

As we can expect, alors often keeps the semantic function of a connector, indicating a logic deduction from the previous proposition. In l. 10 alors should be interpreted as a connector inside the planned utterance and not as part of the planning process. In contrast, in l. 6 alors follows a long pause and can be seen as a strategy to regain speech fluency. The marker has a discourse-structuring function in addition to its semantic function as a connector. The frequency of alors in the planning process of DV is remarkable. In the context of learner language analysis, we hypothesize that the frequent use of alors has to be considered a “lexical teddy bear” (Hasselgren 1994) that maintains a certain state of fluency in the way of a routinely-handled information structure.

Reformulation and Hedging

In situations of planned discourse production—particularly in written language—ou is used as a conjunction and indicates that an alternative to an element mentioned before is as valid as the first option. In spontaneous conversation, however, the same word may introduce a repair of the first utterance, offering a better proposition that invalidates the first one (Table 10).

In Example 8, ou concerns the length of passed time since the last call, as DV called once before and once after his stay abroad.

Example 8: DV’s use of ou as reformulation indicator

In l. 3 DV guesses that the last call has been made around one year ago. However, several devices, namely sound stretchings (pen::se, près), the rising intonation of the utterance, mark the speaker’s uncertainty concerning the time span. The utterance is followed by a pause before ou indicates a reformulation by which DV extends the time span: ou (.) plus même.

The interlanguage is not only characterized by lexical obstacles; grammatical items can also cause difficulties, such as the adjective concord in Example 9.

Example 9: DV’s use of pardon in reformulation

In this case, the corrective reformulation from très vieux to très vieille would not even be necessary, as the reference can be the impersonal pronoun ce instead of ville. In this case, no marker is used for the repair of the first proposition, but the reformulation is closed by the so-called apologetic term (Kitzinger 2013:240f.) pardon. This marker can also be found in native speech; however, we could suppose that it is more likely to refer to content-based repairs whereas we see it here as a form-based repair.

In sum, DV uses a large number of DMs. Most frequently, he structures utterances with alors and mais, but also employs markers for specific contexts, such as the apologetic term pardon. The marker ou is used several times with a metadiscursive function.

Overview: DMs Used in L2

Table 11 shows the kind of DMs the 10 learners of French use in general and the consistency of the use of these markers within the corpus as a whole. This can be seen by the number of informants, i.e. all 10 learners use et and oui/ouais as DMs, for instance.

It is evident that the DMs used by the highest number of informants are not “typical” DMs, such as alors, donc or voilà, but rather DMs that evolved from the conjunctions et, mais, ou, the change-of-state token ah as well as oui/ouais and d’accord. Nevertheless, we find these forms in discourse-structuring positions and some of them are employed with a metadiscursive function in particular, as Table 12 displays.

The list of forms and expressions with a metadiscursive function is topped by ou and oui/ouais. The widespread use of oui in metadiscursive contexts as well as the use of ou as a marker to indicate a reformulation have been discussed in Section “Profile JM” to “Profile DV”. When placing a particular focus on metadiscursive activities, we can find single cases of other forms or even longer expressions that fulfil a discourse-marking function in specific contexts. In the next section, we will focus on the question of how specific these DMs are in L2 by comparing this list to native speaker repertoires.

Comparison of DMs Used in L1 and in L2

Through the conversations between learners and native speakers, it is also possible to identify the DMs of the second group, i.e. the native speakers as informants. As only two native speakers were involved in the study and each of both held several conversations, counting the markers employed by these individuals would distort the comparison, as the amount of talk, and thus the opportunity for using DMs, was much higher. In a compromise solution, the native speakers’ DMs can be presented according to the number of conversations in which the markers occur. In general, we find the DMs displayed in Table 13.

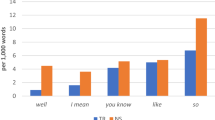

At the top of the list we find alors and donc, whereas the favorite markers of the learners appear less often, and the use of ou as a DM is only marginally existent. In both L1 and L2, we find a long list of forms and expressions that occur only once in each of the corpus (see the last row of Table 13). In order to compare both groups, Fig. 1 shows the occurrences from L2 on the left and from L1 on the right-hand side. Only DMs that occur at least twice in one of both groups are listed.

The quantitative comparison indicates the possible overuse, underuse or misuse (cf. Forsberg 2010:27) of DMs. The DMs oui/ouais, d’accord, ou and parce que are used more consistently in the L2 corpus than in the L1 corpus, whereas the DMs alors, donc, ben/bien/bon, voilà, en fait, (en)fin are used more consistently in the L1 corpus. Hein, en effet, écoutez, disons, c’est-à-dire, sinon and très bien exist only in the L1 corpus. Table 14 focusses on metadiscursive functions.

Apart from alors, the forms that top the list of DMs with a metadiscursive function in L1 rarely occur in the L2 speech. Ben/bien/bon is used less consistently in the L2 corpus than in the L1 corpus. The markers donc, écoutez, c’est-à-dire, disons, en fait and oh are only used in the L1 corpus. Unlike among the learners, markers that are specialized in reformulation processes, such as c’est-à-dire and disons are evident in the L1 corpus, while learners are more likely to use ou, oui/ouais and non. Figure 2 provides an overall view of DMs with a metadiscursive function in both groups.

The quantitative results confirm the markers oui/ouais, ou and non that have been analyzed in the profiles as particular cases of learner-used DMs in metadiscursive activities. Finally, our findings will be discussed in the following section.

Discussion

Metadiscursive Activities, in Which DMs Are Involved

DMs occur in the context of planning problems, in (mostly corrective) reformulations and as metadiscursive evaluations. These activities are often intertwined so that discourse production sometimes appears somewhat labored. DMs are observed in all of the profiles, predominantly in word searches where they co-occur with hesitation phenomena, such as filled and unfilled pauses, recyclings and sound stretchings, that help the speaker to overcome planning problems. Reformulations are not as frequent as word searches. Moreover, the three learners do not seem to use them in the same way. While JM’s reformulations are mainly concerned with self-correction and paraphrasing, and thus with the optimization of her formulation, FH’s reformulations are more closely related to the negotiation of understanding (initiating a reformulation of the interlocutor’s utterance she has not understood or correcting misunderstandings). While the participants in FH’s conversation are thus more oriented towards achieving intersubjectivity (cf. Markaki et al. 2013), JM and her interlocutor also show an orientation towards learning by commenting on difficulties by asking, giving and ratifying help in word searches (cf. also Brouwer 2003). While one of the students (JM) comments repeatedly on her utterances, metadiscursive commentaries are rather the exception in the other profiles.

The Students’ DM Inventory in Comparison to Native Speakers: Formal and Functional Properties

Section “Overview: DMs Used in L2” and “Comparison of DMs Used in L1 and in L2” have clearly shown the relatively small range of DMs learners use in general when compared to the inventory of native speakers’, and the very small range of DMs used with a metadiscursive function. Only ou and oui/ouais are used by the majority of the non-native speakers, while these two markers occur in only two respectively four of the native speakers’ parts of the conversation respectively. These markers are characterized, from a formal point of view, by their low phonetical and morphological complexity. From a functional point of view, ou seems to express a very general idea of alternative in the context of reformulations, while oui seems mostly to be reduced to a so-called “ponctuant” (Traverso 1999:46), helping to overcome the planning problems within the discourse production process. DMs that are used by the native speakers in the majority of the 10 conversations with metadiscursive function (i.e. alors, bon/ben/bien, donc, occurring in six of the conversations) are used by learners, too, but they are not employed by all of them with a metadiscursive function. Alors is used by four of the learners, while ben and donc are used respectively by only one of them. The DMs that are used in several conversations by the native speakers, c’est-à-dire, disons, en fait and comment dire, do not appear at all in the learners’ utterances.Footnote 11 These expressions differ from the aforementioned DMs due to their specialized metadiscursive functions, while ou, oui, alors, ben/bien, and donc are used with a wider range of functions (cf. also Hancock’s (2000:54) distinction between polyfunctional DMs and those with a more specialized semantic charge, all of which form a continuum). Moreover, the former elements are phonetically and morphologically more complex than the latter. The repertoire analysis of DMs that are used in the context of discourse production also corroborates findings on the metadiscursive functions of DMs in other L2 (such as Italian or Spanish) as well as studies on other types of (interactional) DMs in L2. The “typical” DMs used by learners, even at a relatively advanced proficiency level, are semantically rather “unspecific” expressions in that they are phonetically and morphologically relatively simple and are used by learners in a polyfunctional way (cf. e.g. Borreguero Zuloaga et al. 2017; Thörle 2015, 2016; Koch and Thörle 2019).

If we now examine the individual profiles, each of the three learners shows a preference for one or two DMs that s/he clearly uses more often than other DMs of her/his repertoire (JM: oui, voilà; FH: oui; DV: alors) and which can be classified, using Hasselgren’s term (1994:250), as “lexical teddy bears”. These are “core words […] learnt early, widely usable, and above all safe (because they do not show up as errors)”. This is particularly true for JM and FH’s oui and DV’s alors. They correspond to functional or formal similar but not identical forms that are very frequently used in their L1 German (ja, also). Voilà, however, does not fulfil this criterion.

In addition, it is interesting to note that some of the idiosyncratic DMs of JM seem to be approximations of the target language expressions: non-native speakers’ au fin, donc ça veut dire and on dit are similar to the expressions enfin, c’est-à-dire and disons found in the native speakers’ parts of the conversations. Unlike the latter, the non-native speakers’ expressions are less idiomatically fixed and are used with a more literal meaning, i.e. they have not yet undergone a process of pragmaticalization or, at least, this process is not yet completed in the learner’s individual interlanguage (cf. also Pekarek Doehler 2018). The same holds true for the expression comment on dit used by FH. In FH’s conversation, comment on dit is not used as an actual question and does not require an answer. It is uttered with low intensity and marks the speaker’s planning process. It has possibly already undergone a process of routinization but without becoming such a fixed expression as comment dire, for example.

In sum, we can underline that even advanced learners assimilate only a few DMs in their appropriate functional use from the target language point of view. However, they show individual strategies in expressing metadiscursive activities by using specific DMs which are efficacious in their oral discourse production.

Concluding Remarks on Methodology

This study has been based predominantly on the profile analysis of three advanced learners of French L2. In these final remarks, we consider the benefits and limits of this approach. The focus on individual cases enables us to illustrate the relation between the overall DM repertoire of the learner and the forms employed for metadiscursive activities. We have seen that the DMs used with a metadiscursive function coincide mainly with those used in other contexts, thus making them polyfunctional (oui, alors, voilà). The only DM specialized in metadiscursive functions shared by all profiles is ou. Other markers, such as comment on dit, je voulais dire, and pardon, also share formal features of DMs (prosodic backgrounding, low integration, routinization), but their use is still close to the literal propositional meaning. The profile analysis allows us to show the relation between the interlocutors’ orientation (towards intersubjectivity/towards learning) and the implementation of metadiscursive activities (and thus, indirectly, opportunities for DM use).

The difficulty of generalizing the findings to a higher degree of validity for a greater number of learners could be considered a shortcoming of this methodology. However, this approach made it possible for us to identify the relation between individual conduct and cross-individual strategies. For example, the preferred DMs differ from one learner to another. The learner profiles match insofar as they all make use of so-called lexical teddy bears that, although representing different items, share formal and functional properties.

Notes

The emergence of discourse markers is discussed as a cause or result of pragmaticalization (or grammaticalization, depending on the notion of grammar which is adopted, cf. Auer and Günthner 2005; Dostie 2004; Hopper and Traugott 2003). Pragmaticalization occurs when lexical items with propositional meanings are used in a metacommunicative way in order to solve communicative problems and this ‘solution’ becomes habitualized and automatized in the speech community (Frank-Job 2006:359 and 361).

In her study about the pragmatic use of temporal adverbs in French, Hancock (2012) shows that the proportion of the pragmatic use of these expressions exhibits a considerable rise not only between the low-advanced and superior-advanced proficiency level, but also between near-native speakers and native speakers where the rise is particularly steep (see also Fant 2018). This finding corroborates the pragmaticalization hypothesis advanced by Hancock and Sanell (2010) and saying that the acquisition process of the pragmatic uses of certain expressions follows the historical pragmaticalization path of these expressions.

For the details of GAT 2 conventions see “Appendix”.

Note that the interlocutor’s backchannel signals are not counted as turns as they do not interrupt the speaker’s ongoing turn. The latter is thus considered as one single turn.

When referring to DMs at the turn beginning, Table 3 takes into account only the first element of the turn. However, these elements can combine mutually or with other DMs at the turn beginning (euhm oui ben, oui euh alors euh d’abord, ah oui oui ben).

In common dictionaries, ah and oh are generally classified as interjections marking surprise or intensifying the expression of a feeling (cf., e.g. Le Petit Robert 2006). Nevertheless, as change of state-tokens they have been shown to have important functions from an interactional point of view. They are not only used to signal a change of the speaker’s state but also establish a joint orientation (cf. Baldauf-Quilliatre et al. 2014). For this reason, we opted to include these elements in the inventory, too.

For an overview of the current state of research on clicks in interaction cf. Li (2020).

Baldauf-Quilliatre et al. (2014) argue that oh là là, performed by JM as ouh là là, can be analyzed in two different ways: 1. as a ‘mere’ interjection, “emanating in a more or less direct way from the inner stance of the speaker”, and 2. from a social and interactional perspective. From this latter perspective it is interpreted by Baldauf-Quilliatre et al. (2014:193) as an attention-getting token. Although the authors are concerned with a corpus quite different from our L2 corpus, this function may also play a role in JM’s utterance. JM draws the listener’s attention to the language itself (LE français), thus making relevant her identity as a learner of French as a foreign language.

Following Steuckardt (2005), we can consider je voulais dire as a “marqueur de la glose”. This type of markers introduces an expression Y as an explication of another expression X.

As mentioned above, pure backchannel signals are not counted as proper turns. Therefore, the interlocutor’s single backchannel signals do not interrupt the ongoing turn of the speaker. Nevertheless, if the backchannel signal is followed by another utterance of the interlocutor, it is considered a part of the latter’s new turn.

Hancock (2000:64ff.) found in her study on French L2 that donc and enfin are never used by learners whereas they are two of the most frequent DMs in native speakers’ talk. The DM c’est-à-dire is used very rarely and only when it is taken up/repeated from the immediately preceding utterance of the native speaker. For a particular class of metalinguistic reformulation markers (e.g. c’est-à-dire, je veux dire, en d’autres termes) she argues that this kind of markers is not always accessible to the learner. In her study, non-native speakers use them less often than native speakers and fall back on a smaller formal inventory.

References

Auer, P. (2009). On-line syntax: Thoughts on the temporality of spoken language. Language Sciences, 31, 1–13.

Auer, P., & Günthner, S. (2005). Die Entstehung von Diskursmarkern im Deutschen – ein Fall von Grammatikalisierung? In T. Leuschner & T. Mortelsmans (Eds.), Grammatikalisierung im Deutschen (pp. 335–362). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Baldauf-Quilliatre, H., et al. (2014). Oh là là: The contribution of the multimodal database CLAPI the analysis of spoken French. In H. Tyne, et al. (Eds.), French through corpora: Ecological and data-driven perspectives in French language studies (pp. 168–197). Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars.

Bartning, I., & Schlyter, S. (2004). Itinéraires acquisitionnels et stades de développement en français L2. French Language Studies, 14, 281–299.

Bazzanella, C. (2006). Discourse markers in Italian: towards a “compositional” meaning. In K. Fischer (Ed.), Approaches to discourse particles (pp. 449–464). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Borreguero Zuloaga, M. (2015). A vueltas con los marcadores del discurso: de nuevo sobre su delimitación y sus funciones. In A. Ferrari & L. Lala (Eds.), Testualità: Fondamenti, unità, relazioni (pp. 151–170). Firenze: Franco Cesati.

Borreguero Zuloaga, M., Pernas Izquierdo, P., & Gillani, E. (2017). Metadiscursive functions and discourse markers in L2 Italian. In A. P. Loureiro, C. Carapinha, & C. Plag (Eds.), Marcadores discursivos e(m) tradução (pp. 15–58). Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra.

Brouwer, C. (2003). Word search in NNS:NS interaction: Opportunities for language learning? The Modern Language Journal, 87, 534–545.

Bruxelles, S., & Traverso, V. (2006). Usages de la particule voilà dans une réunion de travail: Analyse multimodale. In M. Drescher & B. Job (Eds.), Les marqueurs discursifs dans les langues Romanes (pp. 71–92). Bern: Lang.

De Pietro, J.-F., Matthey, M., & Py, B. (1988). Acquisition et contrat didactique: les séquences potentiellement acquisitionnelles dans la conversation exolingue. Actes du troisième Colloque Régional de Linguistique, Strasbourg 28–29 avril 1988 (pp. 99–119). Strasbourg: Université des Sciences Humaines et Université Pasteur.

Diao-Klaeger, S., & Thörle, B. (2013). Diskursmarker in L2. In C. Bürgel & D. Siepmann (Eds.), Sprachwissenschaft—Fremdsprachendidaktik: Neue Impulse (pp. 145–160). Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Hohengehren.

Dostie, G. (2004). Pragmaticalisation et marqueurs discursifs: Analyse sémantique et traitement lexicographique. Journal of Historical Pragmatics, 7(1), 157–161.

Fant, L. (2018). Discourse and Interaction in Highly Proficient L2 Users. In K. Hyltenstam, I. Bartning, & L. Fant (Eds.), High-level language proficiency in second language and multilingual contexts (pp. 73–95). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Farina, C., Pochon-Berger, E., & Pekarek Doehler, S. (2012). Le développement de la compétence d’interaction: une étude sur le travail lexical. Revue Tranel, 57, 101–119.

Fischer, K. (2014). Discourse markers. In K. P. Schneider & A. Barron (Eds.), Pragmatics of discourse (pp. 271–294). Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

Forsberg, F. (2010). Using conventional sequences in L2 French. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 48, 25–51.

Forsberg, F., & Fant, L. (2010). Idiomatically speaking: Effects of task variation on formulaic language in highly proficient users of L2 French and Spanish. In D. Wood (Ed.), Perspectives on formulaic language. acquisition and communication (pp. 47–70). London: Continuum.

Frank-Job, B. (2006). A dynamic-interactional approach to discourse marker. In K. Fischer (Ed.), Approaches to discourse particles (pp. 359–374). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Gajo, L., & Mondada, L. (2000). Interactions et acquisitions en contexte: Modes d’appropriation de compétences discursives plurilingues par de jeunes immigrés. Fribourg: Éditions Universitaires Fribourg Suisse.

Gülich, E. (1986). L’organisation conversationnelle des énoncés inachevés et de leur achèvement interactif en ‘situation de contact’. DRLAV: Revue Linguistique, 34/35, 161–182.

Gülich, E., & Kotschi, T. (1995). Discourse production in oral communication: A study based on French. In U. M. Quasthoff (Ed.), Aspects of Oral Communication (pp. 30–66). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Hancock, V. (2000). Quelques connecteurs et modalisateurs dans le français parlé d’apprenants avancés: Étude comparative entre suédophones et locuteurs natifs. Stockholm: Stockholms universitet.

Hancock, V. (2012). Pragmatic use of temporal adverbs in L1 and L2 French: Functions and syntactic positions of textual markers in a spoken corpus. Language, Interaction and Acquisition, 3(1), 29–51.

Hancock, V., & Sanell, A. (2010). Pragmaticalisation des adverbes temporels dans le français parlé L1 et L2: Étude développementale de alors, après, maintenant, déjà, encore et toujours. EUROSLA Yearbook, 10, 62–91.

Hasselgren, A. (1994). Lexical teddy bears and advanced learners: A study into the ways Norwegian students cope with English vocabulary. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(2), 237–260.

Heritage, J. (1984). A change-of-state token and aspects of its sequential placement. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action. Studies in conversational analysis (pp. 299–345). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hopper, P. J., & Traugott, E. C. (2003). Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jafrancesco, E. (2015). L’acquisizione dei segnali discorsivi in italiano L2. Italiano Lingua Due, 1, 1–39.

Kerr-Barnes, B. (1998). The acquisition of connectors in French L2 narrative discourse. French Language Studies, 8, 189–208.

Kitzinger, C. (2013). Repair. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), The handbook of conversational analysis (pp. 229–256). Chichester: Wiley.

Koch, C. (2016). Sí, sí, estudio Lehramt, sí. El uso de los marcadores de afirmación en el español de estudiantes ger-manohablantes. Testi e linguaggi, 10, 159–172.

Koch, C., & Thörle, B. (2019). The discourse markers sí, claro and vale in Spanish as a Foreign Language. In I. Bello et al. (Eds.), Cognitive insights in discourse markers in second language acquisition (pp. 119–149). Oxford: Lang.

Le Petit Robert. (2006). Rey-Debove, J., & Rey, A. (2006). Le nouveau petit Robert: dictionnaire alphabétique et analogique de la langue française. Texte remanié et amplifié sous la direction de Josette Rey-Debove et Alain Rey. Paris: Le Robert.

Lerner, G. H. (2002). Turn-sharing. The choral co-production of talk-in-interaction. In C. E. Ford, B. A. Fox, & S. A. Thompson (Eds.), The language of turn and sequence (pp. 225–256). Oxford: University Press.

Li, X. (2020). Click-initiated self-repair in changing the sequential trajectory of actions-in-progress. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 90–117.

López Serena, A., & Borreguero Zuloaga, M. (2011). Los marcadores del discurso y la variación lengua hablada vs. lengua escrita. In Ó. Loureda Lamas & E. Acín Villa (Eds.), Los estudios sobre marcadores del discurso en español, hoy (pp. 415–495). Madrid: Arco.

Markaki, V., et al. (2013). Multilingual practices in professional settings: Keeping the delicate balance between progressivity and intersubjectivity. In A.-C. Berthoud, F. Grin, & G. Lüdi (Eds.), Exploring the dynamics of multilingualism: the DYLAN project (pp. 1–34). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Maschler, Y. (2009). Metalanguage in interaction: Hebrew discourse markers. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Pascual Escagedo, C. (2015). Análisis de las funciones de los marcadores discursivos en las conversaciones de estudiantes italianos de E/LE. Lingue e Linguaggi, 13, 119–161.

Pekarek Doehler, S. (2013). Social-interactional approaches to SLA: A state of the art and some future perspectives. Language, Interaction and Acquisition, 4(2), 134–160.

Pekarek Doehler, S. (2018). Elaborations on L2 interactional competence: the development of L2 grammar-for-interaction. Classroom Discourse, 9(1), 3–24.

Pekarek Doehler, S., & Berger, E. (2019). On the reflexive relation between developing L2 interactional competence and evolving social relationships: A longitudinal study of word-searches in the ‘wild’. In J. Hellermann, S. Eskildsen, S. Pekarek Doehler, & A. Piirainen-Marsh (Eds.), Conversation analytic research on learning-in-action: The complex ecology of L2 interaction in the wild (pp. 51–75). Cham: Springer.

Pekarek Doehler, S., & Pochon-Berger, E. (2015). The development of L2 interactional competence: Evidence from turn-taking organization, sequence organization, repair organization and preference organization. In T. Cadierno & S. W. Eskildsen (Eds.), Usage-based perspectives on second language learning (pp. 263–288). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Pfeiffer, M. (2015). Selbstreparaturen im Deutschen: Syntaktische und interaktionale Analysen. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Renaud, P., & Rubio Zenil, B. (2010). La réparation dans les conversations acquisitionnelles. In M. Candea & R. Mir-Samii (Eds.), La rectification à l’oral et à l’écrit (pp. 207–220). Paris: Orphys.

Romero Trillo, J. (2002). The pragmatic fossilization of discourse markers in non-native speakers of English. Journal of Pragmatics, 34, 769–784.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696–735.

Saunier, E. (2012). Disons, un impératif de dire? Remarques sur les propriétés du marqueur et son comportement dans les reformulations. L’Information grammaticale, 132, 25–34.

Schegloff, E. A., Jefferson, G., & Sacks, H. (1990). The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. In G. Psathas (Ed.), Interaction competence (pp. 31–61). Washington DC: University Press.

Selting, M., et al. (2012). A system for transcribing talk-in-interaction: GAT 2. Gesprächsforschung, 12, 1–51.

Steuckardt, A. (2005). Les marqueurs formés sur dire. In A. Steuckard & A. Niklas-Salminen (Eds.), Les Marqueurs de glose (pp. 51–65). Aix-en-Provence: Publications de l’Université de Provence.

Thörle, B. (2015). Oui comme marqueur discursif polyfonctionnel en français langue étrangère: Romanistik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 21(1), 3–17.

Thörle, B. (2016). Turn openings in L2 French: An interactional approach to discourse marker acquisition. Language, Interaction and Acquisition, 7(1), 117–144.

Thörle, B. (2017). La coproduction du discours dans les situations de communication exolingues. Ricognizioni, 8, 31–52.

Traverso, V. (1999). L’analyse des conversations. Paris: Nathan.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. We would like to thank both reviewers for their very thoughtful reading and their valuable comments on a prior version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Transcription Conventions (Based on GAT 2; Selting et al. 2012)

Appendix: Transcription Conventions (Based on GAT 2; Selting et al. 2012)

- L:

-

Learner

- N:

-

Native speaker

- a::

-

Short lengthening

- a:::

-

Intermediary lengthening

- a::::

-

Long lengthening

- […]:

-

Overlap and simultaneous talk

- °h:

-

Inbreath

- (.):

-

Micro pause

- (-):

-

Short estimated pause

- (–):

-

Intermediary estimated pause

- (—):

-

Long estimated pause (< 1′′)

- (2.6):

-

Measured pause (≥ 1′′)

- enFANT:

-

Focus accent

- ?:

-

Rising intonation to high

- ,:

-

Rising intonation to mid

- .:

-

Falling intonation to low

- (oui):

-

Assumed wording

- ((noise)):

-

Comment

- < <p> >:

-

piano, soft

- < <all> >:

-

allegro, fast

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koch, C., Thörle, B. Metadiscursive Activities in Oral Discourse Production in L2 French: A Study on Learner Profiles. Corpus Pragmatics 5, 153–186 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41701-020-00089-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41701-020-00089-7