Abstract

Background and Objective

Understanding the socioeconomic burden of multiple sclerosis (MS) is essential to inform policymakers and payers. Real-world studies have associated increasing costs and worsening quality of life (QoL) with disability progression. This study aims to further evaluate the impact of cognition, fatigue, upper and lower limb function (ULF, LLF) impairments, and disease progression per Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) level, on costs and QoL.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional cohort study including 20,988 patients from the German NeuroTransData MS registry from 2009 to 2019. QoL analyses were based on EQ-5D-5L. Cost analyses included indirect/direct medical and non-medical costs. Eight subgroups, ranging from 439 to 1812 patients were created based on presence of measures for disease progression (EDSS), cognition (Symbol Digit Modalities Test [SDMT]), fatigue (Modified Fatigue Impact 5-Item Scale [MFIS-5]), ULF (Nine-Hole Peg Test [9HPT]), and LLF (Timed 25-Foot Walk [T25FW]). Multivariable linear regression assessed the independent effect of each test’s score on QoL and costs, while adjusting for EDSS and 12 other confounders.

Results

Lower QoL was associated with decreasing cognition (p < 0.001), worsening ULF (p = 0.025), and increasing fatigue (p < 0.0001); however, the negative impact of LLF worsening on QoL was not statistically significant (p = 0.54). Higher costs were associated with decreasing cognition (p < 0.001), worsening of ULF (p = 0.0058) and LLF (p = 0.049), and increasing fatigue (p < 0.0001). Each 1-scale-step worsening function of SDMT, MFIS-5, 9HPT, and T25FW scores resulted in €170, €790, €330, and €520 higher costs, respectively. Modeling disability progression based on SDMT, MFIS-5, 9HPT, and T25FW scores as an interaction with EDSS strata found associations with lower QoL and higher costs at variable EDSS ranges.

Conclusions

Disease progression in MS measured by 9HPT, SDMT, and MFIS-5 had a significant negative impact on QoL and broad socioeconomic costs independent of EDSS. T25FW had a significant negative association with costs. Cognition, fatigue, ULF, and LLF have stronger impact on costs and QoL in patients with higher EDSS scores. Additional determinants of MS disability status, including SDMT, MFIS-5, 9HPT, and T25FW, should be considered for assessing cost effectiveness of novel therapeutics for MS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The incorporation of diverse measures of multiple sclerosis (MS) disease progression into models assessing quality of life (QoL) and costs associated with disability status allows for a more accurate evaluation of the cost effectiveness of disease-modifying therapies for the treatment of MS. |

This study evaluated the impact of cognition, fatigue, upper and lower limb function (ULF, LLF) impairments, and disease progression per Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) levels, on costs and QoL. |

Decreasing cognition, worsening of ULF/LLF, and increasing fatigue negatively impact QoL and costs in patients with MS independent of EDSS; greater impact was found in MS patients with higher EDSS scores. |

These findings support the importance of additional determinants of MS disability status, including Symbol Digit Modalities Test, Modified Fatigue Impact 5-Item Scale, Nine-Hole Peg Test, and Timed 25-Foot Walk, along with EDSS, when assessing the economic burden of MS. |

This research may inform health policy decisions on cost-effectiveness analyses of novel therapeutics for MS when considering the QoL and economic burden associated with disease progression. |

1 Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is one of the most widespread neurologic disorders amongst young adults, estimated to affect 2.8 million people in 2020 worldwide [1]. MS symptoms vary widely from depression, exhaustion, problems with vision, cognition, bowel and bladder, and muscle stiffness; to causing significant mobility issues that require a walking aid or wheelchair; and in worst cases, confinement to a bed [2]. Moreover, progression of disability, independent of relapse, needs particular attention as a significant driver in the course of the patient’s impairment [3]. MS disability severity is typically measured using the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), the basis of common endpoints in MS randomized clinical trials [4, 5]. The greater availability and spectrum of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) over the past decade has enabled an overall better control of relapse activity and EDSS-assessed disease progression [6]. However, treating MS remains challenging because of the multisystem nature and diversity of symptoms, causing a relevant impact on quality of life (QoL), mobility, and individual autonomy [2].

Progress in the effectiveness of DMTs may result in societally relevant cost savings as MS has significant burden on individuals, their families, and also to the wider society [1, 7]. The socioeconomic costs of MS go beyond medical costs (e.g., hospitalization). Studies have demonstrated that increased disease severity leads to non-medical and indirect expenditures, such as care provided by family and professionals, becoming more significant [8,9,10,11,12]. Furthermore, workforce participation rates decline as an individual’s disability increases; initially there is an increase in short-term job absence costs, and over time there is a shift towards costs associated with long-term work absence [8, 9, 11, 13].

Despite methodological limitations, EDSS remains the most widespread clinical assessment of disability [13, 14], although it does not accurately measure crucial features of progression such as cognition or fatigue [14, 15], and might have limited sensitivity for capturing upper limb function (ULF) and lower limb function (LLF) impairment [16]. Many MS symptoms are therefore not routinely captured by standard clinical investigation, and their consequences are often neglected in assessments of the clinical and socioeconomic burden that MS imposes on people and society.

Indeed, cognition and fatigue have been highlighted as potentially significant contributing factors to patient QoL, economic burden, and employment status in MS [17,18,19,20,21]. However, previous studies assessing the economic burden of MS have been limited by small sample sizes, lack of control for confounders, and a limited ability to disentangle the various factors that could affect economic burden independently of EDSS scores.

Previously, we evaluated the broader impact of MS disease progression on societal costs and QoL per EDSS level, regardless of MS phenotype and treatment (per Dillon et al.) [22]; using multivariable modeling, QoL worsened and healthcare costs were shown to increase with each 0.5 step in EDSS. The objective of this study was to evaluate costs and QoL changes associated with disability status as defined by EDSS and the additional impact of cognitive status, fatigue, ULF, and LLF.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Population

This retrospective, cross-sectional cohort study of people with MS (PwMS) used routinely collected data from the NeuroTransData (NTD) MS registry [23]. Data from all PwMS who met the following criteria were eligible for inclusion: MS diagnosis by neurologist; full information availability on age, sex, living status, and education. PwMS who were prescribed an off-label DMT (n = 206) were excluded from the study.

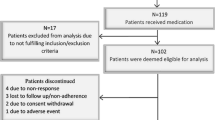

Two cohorts were evaluated in this study: (i) the QoL cohort (Fig. 1a) included data from PwMS with visits to NTD clinics between 2009 and 2019. Eligible visits must have included EDSS and EQ-5D-5L assessments measured on the same day (first visit with an assessment was defined as the index date); (ii) costs cohort (Fig. 1b) included PwMS with visits at NTD clinics from January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2019 during which EDSS was assessed (index date). Another visit during the year prior to the index date with assessment of EDSS was recorded to ensure adequate capture of patient characteristics and socioeconomic costs in the year prior to the index date.

Study population overview flowcharts for a QoL/utility and b HCRU/costs. aSPMS patients (e.g., on interferon) are not excluded even though interferon does not have a label for SPMS. bFull covariate list: Age, sex, living status, educational attainment, time since diagnosis, time since manifestation, MS subtype, time since last relapse, number of relapses in previous year, time since last confirmed disability progression, current DMT, and time since last DMT change. 9HPT Nine-Hole Peg Test, DMT disease-modifying therapy, EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale, EQ-5D-5L European Quality of Life 5-Dimensions Questionnaire-Five Levels, HCRU healthcare resource utilization, MFIS-5 Modified Fatigue Impact 5-Item Scale, MS multiple sclerosis, NTD NeuroTransData, QoL quality of life, SDMT Symbol Digit Modalities Test, SPMS secondary progressive multiple sclerosis, T25FW Timed 25-Foot Walk

For both cohorts, PwMS may be eligible for the study at multiple time points, and for each individual, the most recent eligible time point was selected as the index date for patient inclusion. Additionally, for both cohorts one of the following tests must have been measured within 3 months before or after the index date: the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT), a psychomotor assessment of both motor and processing speed [24]; the Modified Fatigue Impact 5-Item Scale (MFIS-5), a questionnaire for assessing fatigue in clinical and research practice [25]; the Nine-Hole Peg Test (9HPT), a quantitative assessment used to measure arm and hand function (i.e., ULF) [26]; and the Timed 25-Foot Walk (T25FW) test, a quantitative mobility and leg function performance test (i.e., LLF) [27]. Based on the presence of a measure of the SDMT, MFIS-5, 9HPT, and/or T25FW (later referred to as secondary scores), we created four separate subgroups for each cohort. Within each subgroup, the additional impact of cognition, fatigue, ULF, and LLF beyond that of EDSS on QoL and socioeconomic costs was evaluated in multivariable linear regression models.

2.2 Data Source and Setting

Patient inclusion with informed consent is completed in the respective NTD practice as part of routine clinical care. After consent is obtained from each patient, demographics, clinical data, and patient-reported outcomes are captured during outpatient visits in NTD offices using the web-based NTD registry platform [28]. All data are pseudonymized and pooled. The Institute for Medical Information Processing, Biometry and Epidemiology (Institut für Medizinische Informationsverarbeitung, Biometrie und Epidemiologie) at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, Germany, manages codes and acts as an external trust center. An advanced qualified data management and data quality system ensures high data quality [29]. Patients explicitly agreed to any secondary use of their data.

2.3 Outcome Measures

Evaluation of QoL and costs was carried out as per Dillon et al. [22]. To evaluate QoL, utilities were estimated from the EQ-5D-5L scores recorded in the NTD database using the German value set published in Ludwig et al. [30]. For societal costs, analyses were conducted from the societal perspective including direct medical and non-medical costs, and indirect costs (i.e., all costs to all parties). Data from the NTD registry were used to characterize patients’ healthcare resource utilization (HCRU), such as requirements for formal care (e.g., inpatient care, consultations, brain MRI, and medications), informal care, investments required to cope with disability, and impacts on working career. Data from the index date visit and at least one other visit in the prior 12 months were used to describe HCRU and generate an annualized cost. The HCRU categories were derived from previous studies [9] and records of healthcare visits, investigations, treatments, need for equipment, care, etc. were used to quantify HCRU/costs. The costs related to these factors were obtained from the authors from previous research studies [8, 9] that utilized publicly available information, such as average costs for hospital stays, consultations, etc., which we adjusted to 2019 values using the consumer price index. Additional searches of public information were conducted as needed to gather sample costs, including the prices of assistive devices from up to 10 product websites. Productivity losses were assessed using the human-capital method, utilizing the national German cost of labor. The costs of care were estimated based on binary (yes/no) indicators of whether specific types of care were required, such as daycare, family care, short-term inpatient stays, outpatient care, and community-based domestic assistance. Due to the lack of data on the number of care hours provided, the average cost of informal care (family care) per EDSS level was estimated based on previous studies. Investment costs were determined based on product lifespan with periodic maintenance included, and these costs, along with data from product specifications, were gathered. Some products had unclear costs and lifespans; for instance, ‘house modification’ costs could range from less than €1000 (for ramps) to over €20,000 (for complete flat adaptations). To standardize, we used the average costs per flat in Germany to establish a flat barrier fee (excluding expenses for tub lifts and stair escalators, which were considered as separate items).

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Multivariable linear regression analysis was employed to assess the independent effect of scores for SDMT, MFIS-5, 9HPT, and T25FW separately on QoL/utility and HCRU/costs, while adjusting for EDSS (categorical 1.0 increments) and other key confounders, including demographics (age, sex, living status, educational attainment) and MS disease characteristics (time since diagnosis, time since manifestation, MS subtype, time since last 12-week confirmed disability progression event, time since last relapse, number of relapses in previous year, current DMT, and time since last DMT change).

Primary analyses consisted of eight linear regression models, containing a random effect modeling the impact of medical centers. We assessed potential multicollinearity by estimating the generalized variance inflation factor (VIF) for all independent variables [31]. Excessive multicollinearity would reduce the robustness of estimates for independent impact of SDMT, MFIS-5, 9HPT, and T25FW scores relative to the EDSS. A conservative threshold of 2.5 was used to evaluate multicollinearity, although VIF >5 is a generally accepted indicator for severe collinearity [32,33,34].

Our secondary analyses evaluated potential non-linear relationships between secondary scores (SDMT, MFIS-5, 9HPT, and T25FW), and QoL and costs dependent on EDSS. Firstly, distribution of these variables within EDSS strata were plotted visually using partial regression plots. The EDSS strata (EDSS 0.0, EDSS 1.0–1.5, EDSS 2.0–2.5, EDSS 3.0–3.5, EDSS 4.0–4.5, EDSS 5.0+) were informed by previous studies and identified on the basis of the sample sizes available (Table 1) [8, 9]. These EDSS strata correspond to clinically relevant classifications of disability levels, in particular for EDSS scores ≥5.0, allowing the grouping of patients who were partially ambulatory or non-ambulatory with significant loss of autonomy and major dependency.

Subsequently, the secondary scores were modeled as an interaction with EDSS strata in eight further multivariable mixed linear regression models in order to estimate the non-linear association of the secondary scores on QoL and costs. A data-dependent normalization strategy was employed to account for the variation in secondary scores dependent on EDSS strata. Within each strata, we established the corresponding z scores based on the means and standard deviations for each of the secondary scores. Subsequently, z scores were capped to the range (−1.96, +1.96) per strata, and the division was undone by multiplication with the original standard deviation per strata. This strategy ensured that the analysis was not driven by extreme outliers (often observed for 9HPT and T25FW) and defines a typical range for each secondary score per EDSS strata where linear relationships are most likely. Scores for MFIS-5 were not ‘normalized’ due to their categorical nature.

3 Results

3.1 Study Cohorts

The NTD registry included a population of 20,988 MS patients from 2009 to 2019, of which an initial sample of 12,889 PwMS were eligible for the QoL analyses (Fig. 1a). Then, four subgroups were created with full covariate information available plus secondary scores: 1812 for SDMT, 1603 for MFIS-5, 439 for 9HPT, and 609 for T25FW. For the cost analyses, the initial NTD registry population was smaller (n = 14,507) due to a more limited analysis window (2016–2019) and the eligible costs cohort included 12,221 PwMS (Fig. 1b). Costs cohort subgroups with full covariate information available included 1315 for SDMT, 762 for MFIS-5, 572 for 9HPT, and 567 for T25FW. Demographics and baseline characteristics of each QoL and costs cohort per secondary scores are summarized in Table 2. The average secondary scores by EDSS strata for the QoL and costs cohorts are described in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively (see electronic supplementary material [ESM]), showing shifts in secondary scores per EDSS group, which suggested that an interaction with EDSS strata was needed as the dynamic range varied.

3.2 Quality of Life

In the four separate multivariable models (primary analyses), worsening function per secondary score except for T25FW had a statistically significant negative association with QoL and utility scores (Table 3). Multicollinearity did not have significant influence on parameter estimates of secondary scores since the VIF never exceeded 1.33 (data not shown). Each one unit decrease in SDMT, reflecting lower cognition, was associated with a 0.13% decrease in utility. Each 1-point increase on the MFIS-5, reflecting higher fatigue, was associated with a 2.3% decrease in utility. Each 1-second increase in 9HPT, reflecting worsening ULF, was associated with a 0.29% decrease in utility.

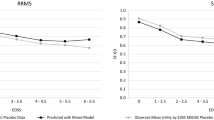

However, non-linear relationships were evident and further modeling of secondary scores as an EDSS strata interaction was performed (secondary analyses, Fig. 2). In these analyses, poorer SDMT score, reflecting decreasing cognition, at EDSS 2.0–2.5 and EDSS 4.0–4.5 demonstrated a significant association with lower QoL. Increasing fatigue, reflected in increasing MFIS-5, demonstrated a significant association with lower QoL across each EDSS category. Worsening ULF, reflected in longer 9HPT times, was significantly associated with lower QoL at EDSS 2.0–3.5, with non-significant decrements to QoL observed at lower EDSS (<2) also observed and a possible ceiling effect at higher EDSS (4+) as the impact of 9HPT attenuated towards the null. A longer T25FW time displayed trends of lower QoL with non-zero coefficients at lower EDSS (<4), which attenuated towards the null at higher EDSS (4+). Forest plots have been constructed for the graphic representation of the summarized estimated results between the coefficient values and EDSS (Fig. 3).

Distributions of a SDMT, b MFIS-5, c 9HPT, and d T25FW scores for the QoL population, separated by EDSS strata. 9HPT Nine-Hole Peg Test, EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale, MFIS-5 Modified Fatigue Impact 5-Item Scale, QoL quality of life, SDMT Symbol Digit Modalities Test, T25FW Timed 25-Foot Walk

Forest plots for a cognition (SDMT), b fatigue (MFIS-5), c upper limb (9HPT), and d lower limb function (T25FW) outcome measures to QoL/utility within strata of EDSS. 9HPT Nine-Hole Peg Test, CI confidence interval, EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale, MFIS-5 Modified Fatigue Impact 5-Item Scale, QoL quality of life, SDMT Symbol Digit Modalities Test, T25FW Timed 25-Foot Walk

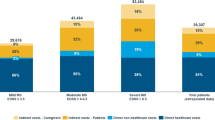

3.3 Costs

In the four separate multivariable models (primary analyses), worsening function per secondary score (i.e., SDMT, MFIS-5, 9HPT, T25FW) had a significantly negative association with overall societal costs (Table 3). Multicollinearity did not influence parameter estimates of secondary scores since the highest VIF estimated was 1.39 (data not shown). Each 1-point decrease in SDMT, reflecting lower cognition, was associated with €170 higher costs. Each 1-point increase on the MFIS-5, reflecting higher fatigue, was associated with €790 higher costs. Additionally, each 1-second increase in 9HPT, reflecting worsening ULF, was associated with €330 higher costs. Whereas each 1-second increase in T25FW, reflecting worsening LLF, was associated with €520 higher costs.

Non-linear relationships were evident and further modeling of secondary scores as an interaction with EDSS strata was performed (secondary analyses, Fig. 4). In these analyses, decreasing SDMT, reflecting lower cognition, at EDSS 2.0–4.5 demonstrated significant associations with higher costs. At lower EDSS (<2), the impact of SDMT on costs was attenuated and was inconsistent with other strata at high EDSS (5+). Increasing fatigue, reflected by an increase in MFIS-5 scores, at EDSS 2.0–4.5 demonstrated a significant association with higher costs, which appeared to attenuate at lower (<2) and higher (5+) EDSS. Worsening ULF, reflected in longer 9HPT times, was significantly associated with higher costs at EDSS 2.0–2.5 and EDSS 4.0–4.5 with an inconsistent impact across remaining EDSS strata. Worsening LLF, captured as higher T25FW values, displayed trends of associations with higher costs, with largest impacts at EDSS 2.0–2.5 and EDSS 4.0–4.5. Forest plots have been constructed for the graphic representation of the summarized estimated results between the coefficient values and EDSS (Fig. 5).

Forest plots for a cognition (SDMT), b fatigue (MFIS-5), c upper limb (9HPT), and d lower limb function (T25FW) outcome measures to HCRU/costs within strata of EDSS. 9HPT Nine-Hole Peg Test, CI confidence interval, EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale, HCRU healthcare resource utilization, MFIS-5 Modified Fatigue Impact 5-Item Scale, SDMT Symbol Digit Modalities Test, T25FW Timed 25-Foot Walk

4 Summary of Findings

The multivariable models demonstrated that worsening function per secondary score (i.e., SDMT, MFIS-5, 9HPT, T25FW) had a significant negative association with HCRU and costs. Modeling of secondary scores as an interaction with EDSS strata demonstrated significant associations between secondary scores and higher costs at variable EDSS ranges.

5 Discussion

This retrospective study of PwMS within the German NTD MS registry demonstrated significant and negative impacts of MS disability status on QoL and socioeconomic costs beyond those measured by the EDSS, including cognitive status, fatigue, ULF, and LLF (with the single exception of T25FW on QoL). The influence of these factors on QoL and costs were observed to be non-linear across strata of EDSS. The directional impact of declining cognition, increasing fatigue, worsening ULF and LLF on decreased QoL and increased socioeconomic costs might be anticipated. However, the relationships appeared to be stronger at lower EDSS levels, perhaps due to patients adapting to their disability at higher EDSS levels. Similar findings have been reported elsewhere, albeit in smaller samples with limited control of confounding variables; in particular, multiple studies did not adjust for EDSS as a covariate in their respective models. These studies have concluded that impairment in upper extremity motor function contributed to an impairment in the physical domain of QoL [35], while walking ability, EDSS, and cognitive performance were independently associated with employment status, and have an impact on societal costs [36].

In our study, decreasing cognition measured by SDMT was associated with a lower QoL and higher costs. Applying thresholds that reflect clinically meaningful change (lower cognition), at the population level [37], we found that each 4-point decrease in SDMT was associated with an approximate 0.52% decrease in utility. Several studies reported that SDMT has a relationship with QoL in cohorts with median EDSS of 1.5 [38], 2.5 [39], and 3.5 [40], as well as in middle-aged cohorts [41, 42]. However, cognition has also been found to have no effect on QoL in an older population with median EDSS of 4.75 [43]. This latter study aligns with the absence of an impact of cognition on QoL for patients with EDSS ≥5.0 seen in the secondary analyses of our study. In models using an interaction term between SDMT and EDSS strata, decreasing cognition had a negative impact on QoL at EDSS ranging from 0.0 to 4.5, but not at EDSS 5.0 and above. Although the association with QoL at EDSS 0.0, 1.0–1.5, and 3.0–3.5 were non-significant, the coefficients were consistent at the lower EDSS levels. Our study extends findings of the previous studies [38,39,40,41,42,43] using a broader spectrum of MS across age and disability, combined with the larger sample size, allowing not only for the global assessment of impact of cognition of QoL across all levels of EDSS but also within EDSS levels.

A systematic review of studies investigating objective cognitive performance and unemployment in MS found a relationship between employment status and cognition in MS, in particular information processing speed assessed by SDMT [44]. Another study exploring the impact of cognitive deficits on employment in PwMS and its contribution to the economic burden of MS, reported that cognitive performance, assessed by the Audio Recorded Cognitive Screen and SDMT, was negatively correlated with economic burden in MS, but independent of EDSS scores [45]. In this study we found an increase in costs of €680 when applying a 4-point clinically meaningful change in SDMT, and in secondary analyses the increase in costs was most relevant at EDSS 2.0–4.5. Overall, these findings suggest that cognitive deficits are a major contributor to unemployment, supporting the assumption that cognitive impairment may contribute to the overall economic burden of MS, particularly as the disease progresses over time. Our study adds to previous research by using a broader range of cost categories rather than restricting to a specific category such as costs due to unemployment. Future research in this area could focus on the longitudinal relationships of cognitive decline starting from time of diagnosis.

Fatigue is often reported as the most frequent and disabling symptom among PwMS and has a significant impact on the psychologic and social consequences affecting patients’ daily life [46]. In the current study, fatigue was significantly associated with QoL and costs in primary analyses, and of the battery of tests utilized in the present study, fatigue most consistently impacted QoL and socioeconomic costs across the EDSS strata in secondary analyses. In particular, a greater impact of fatigue on QoL was observed at upper EDSS levels. Algorithms to convert Fatigue Severity Scale scores to health state utility values have been developed for use in the estimation of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), which are a policy-relevant measure for use in cost-effectiveness analyses [47]. Our results using larger diverse cohorts of MS patients confirm previous findings, indicating that fatigue as a consequence of MS progression contributes significantly to decreased QoL [21, 39, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59] and increased societal costs [60,61,62], and that measures of fatigue are therefore likely to lend themselves to QALY cost-effectiveness analyses [47].

In the current study, worsening ULF had a significant association with decreasing QoL and increasing costs, and in secondary analyses had the largest decrements on QoL and costs at EDSS 2.0–4.5. By contrast, worsening LLF based on T25FW was only associated with higher costs in primary analyses, and in secondary analyses displayed non-significant trends of lower QoL at EDSS 0–3.5 and higher costs at EDSS 2.0–4.5. Our finding of varying relationships with QoL occurring across EDSS strata is reflected in other studies, where a stronger connection between the 9HPT and QoL, than T25FW and QoL was seen [63], while in an older population, no link was found between the T25FW and QoL in patients with EDSS score >5 [26]. The latter finding may possibly be due to ambulation having a less significant impact on patients’ lives than other aspects of disease progression at later stages of MS and may be especially true once patients require a wheelchair. With regard to costs, prior studies have also observed increasing 9HPT and T25FW scores were correlated with increasing annualized direct [64] and indirect costs [65] associated with MS; however, EDSS was not included in the indirect-cost model [65].

To our knowledge, this study is the first to use routinely collected data from outpatient neurology clinics to describe the costs and QoL associated with disability status (as defined by EDSS) and to evaluate the additional impact of cognition, fatigue, ULF, and LLF on costs and QoL.

Strengths of this study include the assessment of EDSS by the patient’s treating neurologist, the large sample size from a real-world setting, although the sample size across each cohort was not homogeneous and was limited for 9HPT and T25FW tests. We also controlled for EDSS and a large number of confounding factors such as education, which are often absent in other studies. Additionally, fatigue was measured in this study using a standardized questionnaire, the MFIS-5, while prior studies relied on visual analog scales to evaluate fatigue [55].

There were limitations to our study, which include those previously described in Dillon et al. [22], such as potential underestimation of costs or the use of outdated cost estimates, and the binary nature of data collected on whether informal care was utilized (yes/no). Due to our cross-sectional study design, clinically relevant score changes within PwMS over time were not analyzed.

Our findings may be limited in their generalizability due to the significant attrition between study populations. The SDMT, MFIS-5, 9HPT, and T25FW are not standard assessments; therefore, the eligibility criteria requiring these tests may have led to a selected population compared with the general MS population within the NTD; although differences in patient characteristics within each cohort were minimal (Table 2), apart from having a higher propensity for relapses in the past 3 months and being on a DMT (which could be explained by a higher clinical need for additional measurements for patients with disease activity and treated with a DMT). Additionally, the model structures used were not adjusted for each additional secondary score and at higher EDSS levels the availability of secondary scores was sparse, thus limiting statistical power and precision in the estimates.

Statistical power was further limited by the use of interaction terms needed to estimate coefficients per EDSS strata, potentially resulting in type II errors. However, it should also be noted that some of the inconsistencies in observations may arise from how the secondary scores were defined. The two aspects to be considered include validity of the instrument and overlap of domains in EQ-5D-5L also measuring similar concepts (i.e., mobility and self-care covered by the T25FW and 9HPT assessments, respectively). Sample size limitations for the T25FW and 9HPT cohorts also impacted the statistical power for those analyses; however, the sample sizes used in this analysis are, overall, large for a real-world data study.

Cut-off values were not used to dichotomize the secondary scores, although clinically relevant changes do exist for these assessments; however, these require longitudinal measurements to define, which was not possible in the current study. The non-linear trends observed in the relationship between secondary scores and outcomes stratified by EDSS, as shown in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 (see ESM), suggest that our secondary analyses modeling interactions of secondary scores with EDSS strata may be more appropriate. However, in line with the literature, we reported our primary model without modeling the interaction. Finally, the non-linear trends observed in our data may also suggest an avenue for future research such as measuring secondary scores longitudinally to account for changes in patient secondary scores and dichotomizing using clinically validated thresholds.

6 Conclusions

The EDSS may not fully measure MS disability concepts of cognition, fatigue, ULF, and milder impacts of LLF at lower EDSS scores, which are determinants of QoL and socioeconomic costs in PwMS [14, 15]. Additional measures of MS disability status, including SDMT, MFIS-5, 9HPT, and T25FW, had a significant negative impact on the QoL of PwMS and broad socioeconomic costs when accounting for EDSS. Recently, additional measures of MS disease progression including fatigue and ULF were judged in a technology appraisal as insufficiently robust to be incorporated into cost-effectiveness models for a DMT in the form of disutility [66]. The findings from the current analyses support the incorporation of other measures such as cognition, fatigue, LLF, and ULF alongside EDSS in models assessing utilities and costs associated with disability status in future economic evaluations of DMTs for the treatment of MS. Overall, these findings may inform health policy decisions in cost-effectiveness analyses of novel therapeutics for MS when considering additional disutility and costs associated with disease progression in PwMS. Health economists, national health authorities, health insurances, and Health Technology Assessment bodies should consider other determinants of disability status in MS including SDMT, MFIS-5, 9HPT, and T25FW, along with EDSS, when assessing economic burden.

References

Walton C, King R, Rechtman L, et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult Scler. 2020;26(14):1816–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458520970841.

Dobson R, Giovannoni G. Multiple sclerosis—a review. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26(1):27–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.13819.

Kappos L, Wolinsky JS, Giovannoni G, et al. Contribution of relapse-independent progression vs relapse-associated worsening to overall confirmed disability accumulation in typical relapsing multiple sclerosis in a pooled analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(9):1132–40. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1568.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33:1444–52. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.33.11.1444.

Lavery AM, Verhey LH, Waldman AT. Outcome measures in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: capturing disability and disease progression in clinical trials. Mult Scler Int. 2014;2014: 262350. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/262350.

Braune S, Rossnagel F, Dikow H, Bergmann A, NeuroTransData Study Group. Impact of drug diversity on treatment effectiveness in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) in Germany between 2010 and 2018: real-world data from the German NeuroTransData multiple sclerosis registry. BMJ Open. 2021;11(8): e042480. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042480.

Trisolini MA, Honeycutt A, Wiener J, Lesesne S. Global economic impact of multiple sclerosis. In: Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. 2010. https://www.msif.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Global_economic_impact_of_MS.pdf. Accessed 13 Jul 2023.

Kobelt G, Thompson A, Berg J, Gannedahl M, Eriksson J, MSCOI Study Group; European Multiple Sclerosis Platform. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Mult Scler. 2017;23(8):1123–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517694432.

Flachenecker P, Kobelt G, Berg J, Capsa D, Gannedahl M, European Multiple Sclerosis Platform. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: results for Germany. Mult Scler. 2017;23(2_suppl):78–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517708141.

Karampampa K, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C, Eckert B. Treatment experience, burden and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in MS study: results from five European countries. Mult Scler. 2012;18(2 Suppl):7–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458512441566.

Karampampa K, Gyllensten H, Yang F, et al. Healthcare, sickness absence, and disability pension cost trajectories in the first 5 years after diagnosis with multiple sclerosis: a prospective register-based cohort study in Sweden. Pharmacoecon Open. 2020;4(1):91–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-019-0150-3.

Ernstsson O, Gyllensten H, Alexanderson K, Tinghög P, Friberg E, Norlund A. Cost of illness of multiple sclerosis - a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7): e0159129. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159129.

Gyllensten H, Kavaliunas A, Murley C, et al. Costs of illness progression for different multiple sclerosis phenotypes: a population-based study in Sweden. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019;5(2):2055217319858383. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055217319858383.

Noseworthy JH, Vandervoort MK, Wong CJ, Ebers GC. Interrater variability with the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and Functional Systems (FS) in a multiple sclerosis clinical trial. The Canadian Cooperation MS Study Group. Neurology. 1990;40(6):971–5. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.40.6.971.

Cadavid D, Cohen JA, Freedman MS, et al. The EDSS-Plus, an improved endpoint for disability progression in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017;23(1):94–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458516638941.

Meyer-Moock S, Feng Y-S, Maeurer M, Dippel F-W, Kohlmann T. Systematic literature review and validity evaluation of the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) and the Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC) in patients with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:58. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-14-58.

Mitchell AJ, Benito-León J, Morales González J-M, Rivera-Navarro J. Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis: integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(9):556–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70166-6.

Smith MM, Arnett PA. Factors related to employment status changes in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(5):602–9. https://doi.org/10.1191/1352458505ms1204oa.

Cadden M, Arnett P. Factors associated with employment status in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2015;17(6):284–91. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2014-057.

Oliva Ramirez A, Keenan A, Kalau O, Worthington E, Cohen L, Singh S. Prevalence and burden of multiple sclerosis-related fatigue: a systematic literature review. BMC Neurol. 2021;21(1):468. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02396-1.

Gustavsen S, Olsson A, Søndergaard HB, et al. The association of selected multiple sclerosis symptoms with disability and quality of life: a large Danish self-report survey. BMC Neurol. 2021;21(1):317. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02344-z.

Dillon P, Heer Y, Karamasioti E, et al. The socioeconomic impact of disability progression in multiple sclerosis: a retrospective cohort study of the German NeuroTransData (NTD) registry. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2023;9(3):20552173231187810. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552173231187810.

NeuroTransData GmbH. NTD database. 2022. https://www.neurotransdata.com/en/. Accessed 8 Apr 2022.

Smith A. Symbol digit modalities test. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1973.

D’Souza E. Modified Fatigue Impact Scale–5-item version (MFIS-5). Occup Med (Lond). 2016;66(3):256–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqv106.

Mathiowetz V, Weber K, Kashman N, Volland G. Adult norms for the nine hole peg test of finger dexterity. Occup Ther J Res. 1985;5(1):24–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/153944928500500102.

Bethoux FA, Palfy DM, Plow MA. Correlates of the timed 25 foot walk in a multiple sclerosis outpatient rehabilitation clinic. Int J Rehabil Res. 2016;39(2):134–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0000000000000157.

Bergmann A, Stangel M, Weih M, et al. Development of registry data to create interactive doctor-patient platforms for personalized patient care, taking the example of the DESTINY System. Front Digit Health. 2021;3: 633427. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2021.633427.

Wehrle K, Tozzi V, Braune S, et al. Implementation of a data control framework to ensure confidentiality, integrity, and availability of high-quality real-world data (RWD) in the NeuroTransData (NTD) registry. JAMIA Open. 2022;5(1):ooac017. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamiaopen/ooac017.

Ludwig K, Graf von der Schulenburg JM, Greiner W. German value set for the EQ-5D-5L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(6):663–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0615-8.

Fox J, Monette G. Generalized collinearity diagnostics. J Am Stat Assoc. 1992;87(417):178–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1992.10475190.

James G, Witten D, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. An introduction to statistical learning: with applications in R. 2nd ed. Springer; 2021.

Menard S. Collinearity. Applied logistic regression analysis. 2nd ed. Quantitative applications in the social sciences. California: Sage Publications, Inc; 2001.

Johnston R, Jones K, Manley D. Confounding and collinearity in regression analysis: a cautionary tale and an alternative procedure, illustrated by studies of British voting behaviour. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1957–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0584-6.

Yozbatiran N, Baskurt F, Baskurt Z, Ozakbas S, Idiman E. Motor assessment of upper extremity function and its relation with fatigue, cognitive function and quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurol Sci. 2006;246(1–2):117–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2006.02.018.

Srpova B, Sobisek L, Novotna K, et al. The clinical and paraclinical correlates of employment status in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2022;43(3):1911–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-021-05553-z.

Benedict RH, DeLuca J, Phillips G, et al. Validity of the Symbol Digit Modalities Test as a cognition performance outcome measure for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017;23(5):721–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517690821.

Giovannetti AM, Schiavolin S, Brenna G, et al. Cognitive function alone is a poor predictor of health-related quality of life in employed patients with MS: results from a cross-sectional study. Clin Neuropsychol. 2016;30(2):201–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2016.1142614.

Niino M, Fukumoto S, Okuno T, et al. Correlation of the Symbol Digit Modalities Test with the quality of life and depression in Japanese patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;57: 103427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2021.103427.

Hoogs M, Kaur S, Smerbeck A, Weinstock-Guttman B, Benedict RHB. Cognition and physical disability in predicting health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2011;13(2):57–63. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073-13.2.57.

Flensner G, Landtblom A-M, Söderhamn O, Ek A-C. Work capacity and health-related quality of life among individuals with multiple sclerosis reduced by fatigue: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:224. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-224.

Fernández O, Baumstarck-Barrau K, Simeoni M-C, Auquier P, MusiQoL Study Group. Patient characteristics and determinants of quality of life in an international population with multiple sclerosis: assessment using the MusiQoL and SF-36 questionnaires. Mult Scler. 2011;17(10):1238–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458511407951.

Baumstarck-Barrau K, Simeoni M-C, Reuter F, et al. Cognitive function and quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-11-17.

Clemens L, Langdon D. How does cognition relate to employment in multiple sclerosis? A systematic review. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;26:183–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2018.09.018.

Maltby VE, Lea RA, Reeves P, Saugbjerg B, Lechner-Scott J. Reduced cognitive function contributes to economic burden of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;60: 103707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2022.103707.

Rottoli M, La Gioia S, Frigeni B, Barcella V. Pathophysiology, assessment and management of multiple sclerosis fatigue: an update. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17(4):373–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2017.1247695.

Goodwin E, Hawton A, Green C. Using the Fatigue Severity Scale to inform healthcare decision-making in multiple sclerosis: mapping to three quality-adjusted life-year measures (EQ-5D-3L, SF-6D, MSIS-8D). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):136. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1205-y.

Englund S, Kierkegaard M, Burman J, et al. Predictors of patient-reported fatigue symptom severity in a nationwide multiple sclerosis cohort. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;70: 104481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2022.104481.

Moore H, Padmakumari Sivaraman Nair K, Baster K, Middleton R, Paling D, Sharrack B. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a UK MS-register based study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;64:103954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2022.103954.

Young CA, Mills R, Rog D, et al. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis is dominated by fatigue, disability and self-efficacy. J Neurol Sci. 2021;426: 117437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2021.117437.

Gulde P, Hermsdörfer J, Rieckmann P. Sensorimotor function does not predict quality of life in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;52: 102986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2021.102986.

Zhang Y, Taylor BV, Simpson Jr S, et al. Feelings of depression, pain and walking difficulties have the largest impact on the quality of life of people with multiple sclerosis, irrespective of clinical phenotype. Mult Scler. 2021;27(8):1262–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458520958369.

Campbell JA, Jelinek GA, Weiland TJ, et al. SF-6D health state utilities for lifestyle, sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of a large international cohort of people with multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(9):2509–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02505-6.

Schmidt S, Jöstingmeyer P. Depression, fatigue and disability are independently associated with quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: results of a cross-sectional study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;35:262–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2019.07.029.

Eriksson J, Kobelt G, Gannedahl M, Berg J. Association between disability, cognition, fatigue, EQ-5D-3L domains, and utilities estimated with different Western European value sets in patients with multiple sclerosis. Value Health. 2019;22(2):231–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.08.002.

Fricska-Nagy Z, Füvesi J, Rózsa C, et al. The effects of fatigue, depression and the level of disability on the health-related quality of life of glatiramer acetate-treated relapsing-remitting patients with multiple sclerosis in Hungary. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;7:26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2016.02.006.

Williams AE, Vietri JT, Isherwood G, Flor A. Symptoms and association with health outcomes in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a US patient survey. Mult Scler Int. 2014;2014: 203183. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/203183.

Reese JP, Wienemann G, John A, et al. Preference-based health status in a German outpatient cohort with multiple sclerosis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:162. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-162.

Papuć E, Stelmasiak Z. Factors predicting quality of life in a group of Polish subjects with multiple sclerosis: accounting for functional state, socio-demographic and clinical factors. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114(4):341–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.11.012.

Le HH, Ken-Opurum J, LaPrade A, Maculaitis MC, Sheehan JJ. Assessment of economic burden of fatigue in adults with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of US National Health and Wellness Survey data. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;65: 103971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2022.103971.

Rodriguez Llorian E, Zhang W, Khakban A, et al. Productivity loss among people with early multiple sclerosis: a Canadian study. Mult Scler. 2022;28(9):1414–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/13524585211069070.

Reese JP, John A, Wienemann G, et al. Economic burden in a German cohort of patients with multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol. 2011;66(6):311–21. https://doi.org/10.1159/000331043.

Alonso RN, Eizaguirre MB, Cohen L, et al. Upper limb dexterity in patients with multiple sclerosis: an important and underrated morbidity. Int J MS Care. 2021;23(2):79–84. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2019-083.

Koch MW, Murray TJ, Fisk J, et al. Hand dexterity and direct disease related cost in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2014;341(1–2):51–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2014.03.047.

Pike J, Jones E, Rajagopalan K, Piercy J, Anderson P. Social and economic burden of walking and mobility problems in multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2012;12(1):94. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-12-94.

Auguste P, Colquitt J, Connock M, et al. Ocrelizumab for treating patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis: an evidence review group perspective of a NICE single technology appraisal. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(6):527–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-020-00889-4.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Preeti Bajaj, Regine Buffels, Seya Colloud, and Gerardo Machnicki for their critical review of the manuscript. Professional medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Sonika Singh (Articulate Science, UK) and funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland. The authors had full editorial control of the manuscript, provided their final approval of all content, approved all statements/declarations, and have authorized submission of the manuscript via a third party. This study was sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland. F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., was involved in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing Interests

Jürgen Wasem is Professor for Health Services Management at University Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany. He received an honorarium for consulting the study concept and quality assurance of data calculations. Yanic Heer was an employee of PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), Zurich, Switzerland during completion of the work related to this manuscript. Eleni Karamasioti was an employee of PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), Zurich, Switzerland during completion of the work related to this manuscript. Erwan Muros-Le Rouzic is an employee of and a shareholder in F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland. Giuseppe Marcelli is an employee of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland. Danilo Di Maio is an employee of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland. Stefan Braune received honoraria from Kassenärztliche Vereinigung Bayerns and health maintenance organizations for patient care; and from Biogen, Merck, NeuroTransData, Novartis, and Roche for consulting, project management, clinical studies, and lectures; he also received honoraria and expense compensation as a board member of NeuroTransData. Gisela Kobelt is President of EHE International GmbH and an employee of European Health Economics, Mulhouse, France. Paul Dillon was an employee of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland during completion of the work related to this manuscript and has shares/ownership of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Ethics Approval

Procedures were approved by the ethical committee of the Bavarian Medical Board (Bayerische Landesärztekammer, June 14, 2012, ID 11144) and of the Medical Board North-Rhine (Ärztekammer Nordrhein, April 25, 2017, ID 2017071). The ethical committee states that it “bases its work on the Declaration of the World Medical Association of Helsinki as amended. It takes into account relevant national and international recommendations, including scientific standards” (https://www.aekno.de/aerztekammer/ethik-kommission/ueber-die-ethik-kommission. In German. Accessed May 24, 2024).

Consent to Participate

All patients gave their informed consent to participate in the study.

Data Availability

The data used in this study are owned by the NeuroTransData registry and sharing of the data is subject to their policies. Any reasonable requests for data access can be directed to the NeuroTransData registry (www.neurotransdata.com).

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data were collected, analyzed, and interpreted by YH and EK. The first draft of the manuscript was written by PD, GK, EM-LR, GM, DDM, SB, and JW. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wasem, J., Heer, Y., Karamasioti, E. et al. Cost and Quality of Life of Disability Progression in Multiple Sclerosis Beyond EDSS: Impact of Cognition, Fatigue, and Limb Impairment. PharmacoEconomics Open (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-024-00501-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-024-00501-x