Abstract

Background

Resource-use measurement is integral for assessing cost-effectiveness within trial-based economic evaluations. Methods for gathering resource-use data from participants are not well developed, with questionnaires typically produced for each trial and rarely validated. The healthcare module of a generic, modular resource-use measure, designed for collecting self-report resource-utilisation data, has recently been developed in the UK. The objective of this research is to identify and prioritise items for new, bolt-on modules, covering informal care, social care and personal expenses incurred due to health and care needs.

Methods

Identification and prioritisation, conducted between April and December 2021, involved a rapid review of questionnaires included in the Database of Instruments for Resource Use Measurement and economic evaluations published from 2011 to 2021 to identify candidate items, an online survey of UK-based social care professionals to identify omitted social care items and focus groups with UK-based health economists and UK-based people who access social care services either for themselves or as carers to prioritise items.

Results

The review identified 203 items. Over half of the 24 survey respondents reported no missing items. Five academic health economists and four people who access social care services participated in focus groups. Feedback shaped the social and informal care modules and indicated that no specific personal expenses were essential to collect in all trials. Aids/adaptations were highlighted as costly personal expenses when relevant; therefore, the personal expenses module was narrowed to aids/adaptations only.

Conclusion

Draft informal care, social care and aids/adaptations modules were developed, ready for further testing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Information on use of social care, informal care, aids and adaptations is collected from participants in randomised controlled trials. |

Draft informal care, social care and aids/adaptations questionnaire modules have been developed and are ready for further testing, before being available for use in research. |

The concise modules will minimise participant burden, increase standardisation, improve data quality and reduce research burden. |

1 Background

Economic evaluations are conducted alongside randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of services, treatments or interventions, to measure the impact on costs and benefits for individuals and society. Measurement of the economic impact in UK-based economic evaluations is often limited to healthcare [1]. However, with advancing population age and increasing prevalence of multimorbidity, there is both a need to measure impacts beyond the health sector and growing interest in joined-up approaches which link health and social care [2]. Social care, informal care (e.g. unpaid care provided by family, friends or neighbours) and items that are purchased by individuals or their family to help manage a health condition are key resources that should be considered for inclusion in economic evaluations. To date, resource-use measurement has lacked standardisation in cost-effectiveness studies [3]. For pragmatic reasons related to cost, time or access, or because suitable routine sources do not exist, resource-use data are often captured via patient-reported questionnaires. Health economists typically create new questionnaires for each study, leading to a lack of consistency and limited comparability across trials [3, 4]. Within the time constraints of an RCT, validation is also not commonly undertaken [1].

The healthcare module of a new resource-use measure was recently developed, with validity testing undertaken [5,6,7]. ModRUM is designed for use in UK-based studies and is free for non-commercial use under licence (see bristol.ac.uk/modrum). To minimise respondent and analyst burden, ModRUM is concise, with a brief core healthcare module. ‘Depth’ questions can be added to capture more detail on cost drivers. ModRUM is generic and can be used in a wide range of health conditions and care settings. ModRUM has a modular design, so that modules covering sectors beyond healthcare could be developed and bolted on when relevant.

The aim of this research is to identify and prioritise items for inclusion in social care, informal care and personal expenses ModRUM modules. The modules were designed to be concise and include items which could be valued in monetary terms. In the social care module, the aim was to capture publicly funded adult social care, whether funded by the UK National Health Service (NHS) or local authorities. In the UK, adult social care includes a “range of activities to help people who are older or living with disability or physical or mental illness live independently and stay well and safe” [8]. It includes personal care at home, day centres, care homes, support for family carers, and aids and adaptations [8]. In the informal care module, the aim was to capture informal (unpaid) care, help or support provided by relatives, friends or neighbours because of long-term physical or mental health conditions or illnesses, or problems related to old age [9,10,11]. In economic evaluations, informal care can be valued using several approaches, including the proxy good method, where informal care is valued using the price of a close market substitute (e.g. a paid carer), and the opportunity cost method, where informal care is valued in terms of what the carer has forgone to provide care (e.g. paid employment) [12]. The valuation method for the informal care module was not predefined. In the personal expenditure module, the aim was to capture direct costs incurred by people to help manage physical or mental health conditions and decide how best to collect this information (e.g. supplements to existing modules or standalone module). Indirect costs, such as lost income, were beyond the remit of the personal expenditure module.

2 Methods

The identification and prioritisation of items for the new modules involved multiple steps (Fig. 1). Data were managed and/or analysed in Microsoft Access, Microsoft Excel and NVivo 12.

Steps taken in the identification and prioritisation of items. 1www.dirum.org

2.1 Rapid Review

2.1.1 Search Strategy

A rapid review was conducted between March and June 2021 to identify social care, informal care and personal expenditure items collected in UK-based economic evaluations with adult participants. Instruments were identified through a search of the Database of Instruments for Resource Use Measurement (DIRUM) (www.DIRUM.org). DIRUM is a repository of instruments for resource-use measurement [13]. All instruments were assessed for eligibility.

Additionally, economic evaluations alongside RCTs were identified via searches of Medline, Embase and PsychINFO, Social Services Abstracts (SSA) and Social Science Citation Index (SSCI). For systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures, it is recommended that Medline and Embase be searched alongside other relevant databases [14]. In a review of databases for literature searches in social work and social care, SSCI and SSA rated highest for unique hits (i.e. results not present in other databases) and sensitivity (i.e. including all relevant literature), and PsychINFO and SSCI rated highest for precision (i.e. percentage of hits) [15]. The search strategy included combinations of related terms for each of the following concepts: study type (limited to trial-based studies), evaluation method (e.g. cost-effectiveness analysis) and sector (e.g. informal care) (Table OR1, Online resource). Searches were restricted by language (English language only) and date (published from 2011 to 2021). Abstracts were screened by one reviewer (K.M.G.).

Finally, a grey literature search was conducted by one reviewer (K.M.G.). Google searches of words synonymous with ‘social care’ and ‘informal care’ were searched alongside government (e.g. NHS) and charity (e.g. The King’s Fund) names, to identify relevant documentation/webpages.

2.1.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Instruments/database articles were included if:

-

They were a UK-based economic evaluation or an instrument designed for use in UK-based economic evaluations alongside RCTs;

-

They included social care, informal care or personal expenses items;

-

They captured data from adults;

-

Resources were captured via self-report or proxy-completion;

-

Resources were captured retrospectively or prospectively (where both were available, only the former was included);

-

The instrument is available, or items tabulated, in disaggregated format.

Instruments/database articles were excluded if they were:

-

Not published in English language.

-

Conference abstracts.

-

Trial protocols.

2.1.3 Extraction and Reduction of Items

Where available, the following information was extracted: (i) instrument/study name, (ii) data extraction source (instrument/article), (iii) retrospective or prospective data collection, (iv) development/publication date, (v) condition(s), (vi) administration mode, (vii) setting and (viii) resource-use sectors (e.g. social care). Only items under relevant sectors were extracted (i.e. social care, informal care, personal expenses). For each item, the following were extracted: (i) item (copied verbatim), (ii) sector, (iii) resource (e.g. social worker) and (iv) details (e.g. yes/no, cost per visit).

The information was extracted as part of a previous study for 59 instruments included in DIRUM up to February 2015 [16]. Where possible, rather than duplicating extraction from the instruments, information was transferred to the database for this study. Extraction was initially performed by two reviewers (K.M.G. and J.C.T.) for a random sample of ten instruments/articles, with divergences discussed. All other extraction was undertaken by one reviewer (K.M.G.). Extracted items were initially deduplicated, then they were systematically grouped into potential items to include in the modules by one reviewer (K.M.G.). A second reviewer checked the categorisations to assess concordance (A.C./J.C.T.).

2.2 Survey of Social Care Professionals

To identify whether any social care items were missing and assess face validity, people working in social care were asked to complete a brief online survey, administered via Online Surveys (onlinesurveys.ac.uk) between July and September 2021.

2.2.1 Sample Selection and Data Collection

Invitations were sent via contacts working in the South-West of England. Respondents were asked to review the list of social care items sourced from the review and report whether any publicly funded adult social care was missing and whether any items in the list might be described differently by users of social services. Job role and number of years’ experience working in adult social care were collected.

2.2.2 Analysis

Categorical responses were analysed using descriptive statistics. Suggested items and terminology were collated and reviewed by two reviewers (K.M.G and J.C.T.) to decide whether items should be added or updated.

2.3 Focus Group with Health Economists

A focus group was conducted with academic health economists on 11 November 2021, to prioritise items to include in the draft modules.

2.3.1 Sampling and Recruitment

Health economists were identified from NIHR-funded study reports, published between 2020 and 2021, that included a social care, informal care and/or personal expenses perspective. To obtain more content expertise, health economists who were not identified from NIHR reports but were known to the research team to have specific expertise in social or informal care were also invited. A purposeful sampling strategy, using publicly available information (such as grants the health economist was a co-applicant on), was used to ensure a mix of experience [17]. The target sample size was four to six [18].

2.3.2 Data Collection

One week prior to the focus group, participants were sent a ranking exercise (Online Resource 2) via Online Surveys. For each module, participants were asked to rank categories. Categories included groups of items (e.g. social care professionals was a category for the social care module). For each category, participants were asked whether items in the category should be asked about (i) individually, (ii) as a general question, (iii) as a combination of individual and general questions or (iv) the category should not be included in the module at all. If the participant selected (i) or (iii), the participant was asked to select the top five most important items (e.g. top five most important social care professionals) or they were asked to rank items in order of importance.

During the online focus group via Zoom, anonymised results from the survey were shared. Discussions were aided by a lead facilitator (K.M.G.) using a pre-defined topic guide (Fig. OR1). Participants were asked why they decided to prioritise particular categories/items. For each category and item, conversations were facilitated to reach consensus on which categories/items should be included.

2.3.3 Data Analysis

The focus group was audio-recorded and transcribed. The transcript was read and reread, and coded for themes [19]. Analysis focussed on comparing the responses in relation to each item, particularly the reasons behind ranking decisions, and examining where there was consensus or disagreement.

2.4 Focus Group with People Who Access Social Care Services

Next, a focus group with people who had accessed social care for themselves or someone they care for was conducted on 3 December 2021. The aim of the focus group was to explore understanding of social and informal care, investigate the validity of items prioritised by health economists and inform the wording of questions.

2.4.1 Sampling and Recruitment

A purposeful sampling strategy was used with the aim of recruiting between four and six people with different experiences of accessing social care services [17, 18]. Invitations were sent to people who expressed an interest but were not members of the study Public Advisory Group for this research. Snowball sampling was used via the Public Advisory Group.

2.4.2 Data Collection

The focus group was held online via Zoom. A main facilitator (K.M.G.) led the discussion using a pre-prepared topic guide (Fig. OR2), which was revised based on findings from the health economist focus group. Topics included understanding and experience of social care and informal care. The focus group was audio-recorded and transcribed.

2.4.3 Data Analysis

The transcript was read and reread, and coded for themes. Analysis focussed on correlating participant responses to potential items for inclusion.

2.5 Formulation of Draft Modules

Following the focus groups, a second survey was sent to the health economist participants to validate conclusions drawn from the feedback. Participants were asked to provide binary responses indicating whether they agreed or disagreed with the conclusions, and to elaborate if the latter. Draft modules were constructed by formulating questions for each item prioritised for inclusion. The modules adopted the same design framework and phraseology as the healthcare module. Modules were edited for consistency and clarity.

3 Results

3.1 Rapid Review to Identify Items

A flow diagram detailing the search is provided in Fig. 2. From 94 instruments identified in DIRUM and 1395 references identified in database searches, 49 instruments, and 77 references relating to 69 unique studies were included. From a grey literature search, 14 further documents/webpages were included for extraction of items related to social care, informal care and personal expenses. A broad range of conditions was covered (Table OR2, Online Resource). A total of 1619 items were extracted from the instruments, studies, documents and webpages. This number reduced to 723 following deduplication. Items were grouped on the basis of meaning, resulting in 203 items (e.g. care assistant, domiciliary care and care worker were grouped under home help/home care worker). The 203 items were grouped under the 13 categories listed in Table 1, which also shows the sectors each category is relevant to.

3.2 Survey of People Working in Social Care

Between July and September 2021, 24 people working in adult social care responded to the survey. Respondents had a range of roles and varied with respect to years’ experience working in adult social care (Table OR3, Online Resource). Of respondents, 58% reported that no adult social care items were missing from the list and 75% reported that the items included would not be described as something different by people who use social care. In Table OR4 (Online Resource), missed items and alternative terminology are presented, along with information on what changes were made in response to the suggestions. There were several reasons that items were not added, including the item already being included in a more general format (e.g. the suggestion of ‘Independent Mental Capacity Advocate’ was considered to be included under ‘Advocate’) and suggested items being outside the scope of the social care module (e.g. health-related items). In response to feedback, ‘social prescriber’ was changed to ‘community navigator/link worker’.

3.3 Focus Group with Health Economists

From NIHR reports, 80 health economists were identified, seven were invited to participate and three participated in the focus group. Four health economists with specific expertise in social or informal care were also invited, and two participated. Participants were based at five academic institutions in England, Scotland and Wales (Table OR5, Online Resource).

3.3.1 Prioritisation of Social Care Items

On the basis of independent ranking, categories that were considered most important for inclusion are presented in Table 2. For the social care module, ‘social care professionals’ was considered the most important category to collect. Participants prioritised ‘professionals’ because “staff is likely to be the highest single cost item that would be differentiating two interventions being assessed within a trial” (health economist (HE) 2)). For the category ‘social care professionals’, ‘home help or home care worker’ and ‘social worker’ were considered the most important items to include by most participants because “thinking about core items, if we have an intervention that has some kind of social care element to it, those are the most likely” (HE3). Many other items (such as ‘welfare rights officer’) were considered to be context dependent and too specific for a generic instrument. Participants suggested that ‘social workers’ could be combined with other similar roles “that develop the care plans for individuals” (HE4).

“...unless you were very interested in social work and care manager in that particular study, you could really combine social work with care manager, and possibly care coordinator together. Because they are doing the same job and they have just got different titles in local authorities.” (HE1)

Owing to geographical variations in terminology for the same roles, there was concern that trial participants would not understand job titles. To resolve this, it was suggested that all potential job titles, or definitions for each role, should be included. For ‘home help’, ‘care assistant’ was suggested as preferable terminology (HE4).

‘Social care services’ were considered the second most important category to include. For this category, ‘respite services’ and ‘day care services’ rated most highly. Participants highlighted potential overlap with ‘social care professionals’, as the unit of measurement in the instrument could be the service (e.g. ‘home care’) or the provider (e.g. ‘care assistant’). HE4 suggested grouping ‘social care services’ into four categories: (i) ‘day services’ (e.g. ‘respite care’), (ii) “services that sit on the interface between health and social care” (e.g. ‘reablement services’), (iii) “technology and aids and adaptation services” and (iv) ‘prevention services’ (e.g. ‘self-help group’).

Items covering ‘housing and residential care’ were rated less important for a generic social care module. HE1 indicated that, dependent on the context, items covering residential care may be highly important if the interventions alter residential care utilisation, or not important at all if residential status does not alter. HE4 indicated that ‘residential care homes’ and ‘nursing homes’ should be captured separately owing to differences in services provided and costs.

‘Aids, equipment and home adaptations’ were considered the least important category to collect in the social care module. Reasons for this included “aids and equipment... never come out to any amount of money” (HE1), poor completion in previous studies (HE3), and “some really big-ticket items like lifts, stairlifts... will be tens of thousands... but often they are being paid for by the individual” (HE4). HE4 thought ‘aids and equipment’ and ‘home adaptations’ could be grouped together. HE1 thought a free-text question would not be appropriate; they suggested, instead, a table with categories. HE4 agreed and suggested a standard cost could be applied to most items rather than asking people to report expenditure.

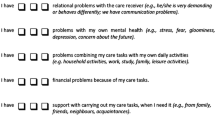

3.3.2 Prioritisation of Informal Care Items

For the informal care module, ‘time spent caring’ was considered most important to collect. ‘Who provided the care (e.g., spouse)’ and ‘what care was provided’ were rated joint second most important. For ‘what care is provided’, ‘personal care’ was considered the most important item, followed by ‘help around the house’, ‘time spent supervising’ and ‘help outside the home’. Participants agreed that these could be labelled ‘personal care’, ‘domestic care’ and ‘supervisory care’. ‘Who provides the most care’, ‘carer’s main activity if not caring’ and ‘carer employment details’ were considered next most important.

For informal care, discussions centred on the importance of items with respect to the costing approach. For the proxy good costing method, ‘what caring is provided’ was considered important, alongside ‘time spent on the caring activity’, for sourcing appropriate unit costs, whereas for the opportunity cost method, ‘what activity is foregone’ is required.

“…it matters what activity they are doing if you are using a proxy good method... if they are doing nursing activity or housework, then you might end up costing in quite a different way… But if you are using the opportunity cost method you are more interested in what activity they have given up…” (HE5)

HE4 highlighted that the type of care often differs depending on the relationship of the informal carer and this is important for costing.

“…co-habiting, caring, spousal care tends to be quite different and often of a close, personal care nature, whereas people that live outside, children for example, tend to provide more instrumental activities like shopping and support…” (HE4)

The difficulty of answering questions on the amount of time spent on caring was highlighted. This included discussion around reporting of ‘supervising’ time, where the carer is present, but not directly providing care. HE3 reported that “some [trial participants] consistently report 24 hours, 24/7 because they are there all the time and obviously if there is an issue at night they would be there to sort things out, even though technically they are asleep”. HE4 mentioned that studies use “broad categories… rather than ask for specific hours”.

When considering what informal carer employment information to collect, ‘main occupation’ was rated second most important, to ‘time off work’, but HE1 said ‘main occupation’ would only be considered relevant if individualised wage rates were used, and not relevant if an average wage would be applied for costing. Other information that was rated less important included ‘given up work’, ‘changed working hours’ and ‘difficulty finding work’. The rationale for this included “you might get only one person in your trial sample that is out of a job” (HE1), “they tend to be one-offs” (HE4) and when deciding what to collect, you need to consider “to what extent might it drive cost differences, or resource use differences between two interventions” (HE5).

3.3.3 Prioritisation of Personal Expenses Items

HE3 explained that, when selecting items to collect in economic evaluations and when ranking items, they considered “why would that [item] be different between the different arms?”. They ranked items lower if they did not think they would differ. ‘Housing and residential care’ was ranked the most important category, with ‘nursing and residential homes’ rated the most important item. This category was rated highly, as dependent on personal circumstances (i.e. whether or not the individual qualifies for government-funded care), it can make a “big difference” (HE4). ‘Care or care professionals’ were ranked the second most important category.

It became apparent during the focus group that some of the participants had ranked personal expenses items with a social care perspective in mind, which explains why care-related categories ranked so highly. Participants said they may have ranked items differently if they were not thinking of the social care perspective. ‘Aids and adaptations’ were ranked more highly for the personal expenses module than for the social care module. HE1 indicated that “they are more important [in the personal expenses module] because they are a cost to you”. They also mentioned that local authorities are likely to get a bulk order discount from suppliers, whereas individuals are likely to pay more.

It was clear from discussions that which personal expenses items to collect would be driven by context. HE2 stated that the list of personal expense items was comprehensive, but “to have a generic personal expenses category… that would simply be too long a list to include” in a concise instrument. Participants also indicated that double counting should be considered, as items can appear in multiple modules.

3.4 Focus Group with People Who Have Accessed Social Care Services

Four people participated. Participant characteristics are presented in Table OR6 (Online Resource). Two participants provided informal care to a spouse, one participant received care for themselves, and one participant assisted a parent with accessing social care and also had experience working in social care.

Participants were initially asked about their understanding of social care and informal care. This highlighted mixed understanding.

“My view of informal care is basically you source your own people you need to assist you and you pay them. Social care, local authority, provide the people and pick up the tab. (Participant (P) 2, provides care for spouse)

“…informal care is unpaid care. So, that might be a family carer or it might be a neighbour or somebody who just helps you out. Whereas formal care is something that is paid for. And that might be by the local authority, or it might be by yourself, you may be funding it yourself.” (P4, provided care for mother, experience of social care in professional capacity)

The term ‘informal care’ was deemed problematic by some participants; P1 cared for their spouse, but did not consider themselves an informal carer “because it’s not ad hoc, it’s every day”. They described themselves as “an unpaid carer”. There were issues evident with the terms ‘care’ and ‘carer’, as individuals may be “resistant to care” (P4) or identify it as help, and care providers, such as P1, said they “struggle to identify as a carer, as it’s what you do in a relationship… you don’t actually think that what you're doing is care”.

“I think the word [care] itself sometimes is not very acceptable to people who are getting older. And if someone says to me, “P3, you need a carer,” I would say, “No, I don’t need a carer”. But if someone said to me, “I think maybe you need a bit of help with your shopping,” that would be a completely different answer that I would give.” (P3)

P3 thought “one way of determining whether a person is actually having care is how often they come”, with something on a frequent basis indicating care. Participants thought the activities that informal carers provide could be separated into ‘maintenance’ (e.g. property upkeep) and ‘personal care’ (e.g. washing hair). In the first focus group, HE4 indicated that informal carer tasks are dependent on their relationship to and whether they are living with the individual they care for. This was confirmed by P4, who was a carer for their mother; they took on administrative tasks, while P1, who cared for their spouse, provided more personal care.

“I just saw myself as somebody who sorted things out really, which was very different to being a carer. I wouldn’t say I had that direct caring role.” (P4)

“You're making meals, cutting meals up, doing drinks, catheters.” (P1)

For time spent caring, P4 thought that informal care time is “not easy to quantify at all”. P2 described doing “17, 18 hour days”, while time spent away from caring “varies from day to day, and you snatch these moments [to do non-caring activities]”. P1 said they like to paint, but they had a monitor, so they could attend to their spouse when needed, indicating that, while they were not directly caring at that time, they were still on-call.

Participants were also asked about their understanding of different job roles in social care. Social workers were understood to “assess what is required… assess affordability” (P2), “conduct a carer’s assessment” (P1) and arrange care. Most participants named social workers as the professional that organises care, with one participant also indicating they had an occupational therapist assessor (P1). P4 said that their relative saw a range of people but would identify them all as a social worker.

“He had a social worker… he also had a care coordinator from the GP practice, he had another care coordinator, or a link worker or something like that, from a voluntary sector organisation, he had a coordinator from the council, and he had somebody who called herself a coordinator from a care company, that was providing his direct care. And he would have called all of those people his social worker.” (P4)

‘Care assistant’ was considered ambiguous by P3.

“Somebody comes and helps me wash my hair. Now, I don’t actually call her a care assistant.” (P3)

Participants indicated that it can be difficult to distinguish what is paid for by government and what they pay for themselves, as social care can be arranged via the council but paid for personally.

“I get an attendance allowance. And that pays for all sorts of things which I need. And I wouldn’t know whether that was the council paying for my care or me looking after it really.” (P3)

Participants also mentioned that some care is provided by the “voluntary sector” (P4), and care by charities can be paid for personally.

“We’ve got Age UK coming in… that is also paid for… they’ll do some mobility exercises with him, they’ll bring iPads and take him on city tours, and things like that. They don’t do personal care… But that, I organised myself.” (P1)

When asked about the main things they had paid for, P2 indicated they had paid for an expensive chair, but social services had provided a walking frame. P1 said they had bought lots of things but “none of them are expensive, but they add up”. P1 thought they could “roughly” and P2 thought they could “pretty accurately” recall how much they had spent.

3.5 Formulation of Draft Modules

Four health economists responded to the survey outlining the initial design of the modules. Most agreed with the items selected for the modules. There was one comment where, dependent on context, the participant advocated for ‘day care’ to be prioritised for inclusion in the social care module over ‘food at home’, as it is more of a core service.

On the basis of feedback from both focus groups, for the social care module, questions were included on ‘care assistant for personal care’, ‘someone who organises care’, ‘support activities (e.g. self-help group)’ and ‘group activities (e.g. day care)’. The informal care module included questions on ‘relationship to care recipient’, ‘time spent caring’ and ‘cohabiting’. Optional questions were drafted on ‘occupation of carer’ and ‘time spent caring by caring activity’. It was clear that a core list of items to collect in a personal expenses module was not appropriate, as what is important is context dependent. Aids and adaptations were indicated as costly expenses for individuals, therefore the focus of the third module was narrowed to aids and adaptations. Collecting data on aids and adaptations can be problematic as it can be funded by the government or the individual themselves, therefore the draft module allows respondents to categorise both the type of aid/adaptation (from cheap to expensive) and the source of funding for each aid/adaptation. The draft modules are provided in the Online Resource (Fig. OR3).

4 Discussion

In this research, a vast number of potential items were identified for new resource-use modules covering social care, informal care and personal expenditure. During a focus group with health economists, items were prioritised. In a focus group with people who access social care services, insight into understanding of social and informal care, and relevance of prioritised items was obtained. On the basis of findings from the focus groups, draft modules were developed.

4.1 Strengths and Limitations of this Research

This research employed a multi-phased approach to identifying and prioritising important social care, informal care and aids and adaptations items to collect in trial-based economic evaluations. The development process is being reported in detail to provide transparency to users. We have drawn on the expertise and experience of a range of people, including health economists with experience of administering resource-use instruments, social care professionals with detailed knowledge of the services currently available and people with experience of receiving or accessing care services. Only two focus groups were conducted to inform the draft modules. While there was generally good agreement amongst health economist participants, and very useful and insightful information from the focus group with people who had accessed social care services, including larger samples may have offered alternative perspectives which could have altered the draft modules.

ModRUM is designed for use in the UK context and may need adaptation and further testing for use outside the UK. Furthermore, the funding landscape for social care in the UK is complex, including differences between the devolved nations and with contributions from local authorities, central government, charitable organisations and social care recipients and their families [20]. Service names vary by geographical location and are subject to change. This complexity means that it was hard to strike the right balance between being sufficiently generic that the instrument could be used in most trials and being understandable to a wide range of people. However, further qualitative interviews with patients/care users and health economists will attempt to address any problems, so that ModRUM is optimised for collecting resource-use data in a range of trials and settings.

4.2 Comparison with Related Literature

Literature on the development of resource-use measures is limited. A review of articles reporting on methods employed to develop resource-use measures found that few instruments were accompanied by development details [7]. Where details were available, they typically did not form a comprehensive account of the methods involved. The process to identify appropriate items for inclusion in new resource-use modules described in this paper differs from processes identified in the review, where authors were found to have described processes that included using existing instruments, literature sources or expert input (from clinicians, health economists or patients) [7]. For the ModRUM healthcare module, items were identified through a Delphi study [5]. However, as social care utilisation is less commonly captured in existing instruments [13] and the social care perspective is less familiar than healthcare to health economists working on trials, it was felt that important items would be better identified by focus groups in which detailed reasons for item inclusion or exclusion could be explored.

Some instruments which include social care resources have development details available, for example the Client Services Receipt Inventory (CSRI) [21]. However, unlike ModRUM, the CSRI was developed for interview administration in the context of mental health conditions [21]. Furthermore, there are many versions of the CSRI, most of which were adapted without further testing. The Annotated Cost Questionnaire for Patients (ACQP) was also developed with standardisation in mind [22]. However, the ACQP is structured to allow analysts to select questions from a large number of items and, in contrast to ModRUM, does not identify the key resource-use items. The PECUNIA RUM was developed for use in multi-sectoral economic evaluations across Europe, and full details of the development process have been published [23]. Item identification for the PECUNIA RUM included literature reviews to identify cost drivers and sector-specific expert reviews of the lists of cost drivers [23]. PECUNIA differs from ModRUM in design: where ModRUM is more concise, PECUNIA captures more information. A questionnaire was recently developed to measure informal caregiving; however, it is designed for carers to complete, while the ModRUM module is designed for completion by care recipients [24]. ModRUM is the first concise, generic, standardised resource-use measurement tool for which comprehensive development details are available.

4.3 Implications of this Research

This research has contributed to creating a flexible instrument that will reduce researcher and participant burden. The healthcare module is already available, and the new modules will be available following further testing. The modules will allow cost and cost-effectiveness comparisons across trials to be made more easily and open the possibility of meta-analysis of costs in future systematic reviews. Using an instrument that has been rigorously developed, such as ModRUM, will help economic evaluations produce high-quality results, leading to more robust decision making.

4.4 Future Research

The draft modules need to be tested for validity and reliability. Semi-structured interviews with practising health economists will be conducted to test the face validity and usefulness (from a costing perspective) of the modules, alongside cognitive ‘think-aloud’ interviews with patients/care users to test validity, comprehensibility and acceptability [25]. The modules will be modified in response to interview findings, before being piloted among the general population.

5 Conclusions

Three draft modules, covering informal care, social care and aids/adaptations, have been developed for use alongside the ModRUM healthcare module. Following further testing, the modules will extend the use of ModRUM to studies undertaking analyses from broader perspectives than healthcare.

References

Ridyard CH, Hughes DA. Methods for the collection of resource use data within clinical trials: a systematic review of studies funded by the UK health technology assessment program. Value Health. 2010;13(8):867–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00788.x.

Care Quality Commission. Beyond barriers: how older people move between health and social care in England 2018. https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20180702_beyond_barriers.pdf. Accessed 25 July 2020.

Thorn JC, Coast J, Cohen D, Hollingworth W, Knapp M, Noble SM, et al. Resource-use measurement based on patient recall: issues and challenges for economic evaluation. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(3):155–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-013-0022-4.

Franklin M, Thorn J. Self-reported and routinely collected electronic healthcare resource-use data for trial-based economic evaluations: the current state of play in England and considerations for the future. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(8):1–13.

Thorn JC, Brookes ST, Ridyard C, Riley R, Hughes DA, Wordsworth S, et al. Core items for a standardized resource use measure (ISRUM): expert Delphi consensus survey. Value Health. 2018;21(6):640–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.06.011.

Garfield K, Husbands S, Thorn JC, Noble S, Hollingworth W. Development of a brief, generic, modular resource-use measure (ModRUM): cognitive interviews with patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06364-w.

Garfield KM. Development of a modular resource-use measure for use in economic evaluations alongside randomised controlled trials: University of Bristol, PhD thesis; 2022. https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/development-of-a-modular-resource-use-measure-for-use-in-economic.

The King's Fund. Key facts and figures about adult social care 2023. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/audio-video/key-facts-figures-adult-social-care. Accessed 3 Jan 2024.

The King’s Fund. Informal workforce 2021. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/time-think-differently/trends-workforce-informal. Accessed 22 Apr 2021.

Office for National Statistics. Health and unpaid care question development for Census 2021 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/census/censustransformationprogramme/healthandunpaidcarequestiondevelopmentforcensus2021. Accessed 22 Apr 2021.

Office for National Statistics. ONS Census Transformation Programme. The 2021 Census. Assessment of initial user requirements on content for England and Wales. Carers topic report 2016. https://www.ons.gov.uk/census/censustransformationprogramme/consultations/the2021censusinitialviewoncontentforenglandandwales. Accessed 22 Apr 2021.

Koopmanschap MA, van Exel NJA, van den Berg B, Brouwer WBF. An overview of methods and applications to value informal care in economic evaluations of healthcare. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:269–80. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200826040-00001.

Ridyard CH, Hughes DA, Dirum Team. Development of a database of instruments for resource-use measurement: purpose, feasibility, and design. Value Health. 2012;15(5):650–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2012.03.004.

Prinsen CAC, Mokkink LB, Bouter LM, Alonso J, Patrick DL, de Vet HCW, et al. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:1147–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1798-3.

Pascoe KM, Waterhouse-Bradley B, McGinn T. Systematic literature searching in social work: a practical guide with database appraisal. Res Soc Work Pract. 2021;31(5):541–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731520986857.

Thorn J, Ridyard C, Riley R, Brookes S, Hughes D, Wordsworth S, et al. Identification of items for a standardised resource-use measure: review of current instruments. Trials. 2015;16(Suppl 2):O26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-16-S2-O26.

Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2014.

Carter SM, Shih P, Williams J, Degeling C, Mooney-Somers J. Conducting qualitative research online: challenges and solutions. Patient Patient Cent Outcomes Res. 2021;14:711–8.

Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine; 1967.

Brown T. Social care provision in the UK and the role of carers. In: Lords Ho, editor. 2021.

Beecham J, Knapp M. Measuring mental health needs. In: Thornicroft G, editor. Costing 7psychiatric interventions. 2nd ed. London: Gaskell; 2001. p. 200–24.

Thompson S, Wordsworth S. An annotated cost questionnaire for completion by patients. HERU Discussion Paper 03/01. 2001.

Pokhilenko I, Janssen LMM, Paulus ATG, Drost RMWA, Hollingworth W, et al. Development of an instrument for the assessment of health-related multi-sectoral resource use in Europe: the PECUNIA RUM. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-022-00780-7.

Landfeldt E, Zethraeus N, Lindgren P. Standardized questionnaire for the measurement, valuation, and estimation of costs of informal care based on the opportunity cost and proxy good method. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2019;17(1):15–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-018-0418-2.

Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing a tool for improving questionnaire design. California: Sage Publications; 2005.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all survey and focus group participants for their valuable contributions to this research. The authors would also like to thank the project Public Advisory Group for their vital input and recommendations. The authors would also like to thank Theis Theisen (University of Agder, Norway) for leading a discussion and attendees for providing feedback on an earlier version of this paper at the 41st Nordic Health Economists’ Study Group meeting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study is funded by the NIHR Research for Patient Benefit programme (NIHR201961). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflict of interest

Kirsty M. Garfield, Gail A. Thornton, Samantha Husbands, Ailsa Cameron, William Hollingworth, Sian M. Noble, Paul Roy and Joanna C. Thorn have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the study. The rapid review was undertaken by K.M.G., with assistance from J.C.T. and A.C. The social care professional survey data was administered and analysed by K.M.G. Focus groups were facilitated by K.M.G. and co-facilitated by G.A.T., J.C.T. and S.H. K.M.G. coded and analysed the data. J.C.T. formulated the first drafts of the modules. All authors contributed to interpreting the data. The first draft of the manuscript was written by K.M.G. and J.C.T. All authors contributed to, reviewed, edited and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this research was granted by the University of Bristol Faculty of Health Science Research Ethics Committee (FREC) (references 0061, 0105). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent to participate

For the survey of social care professionals, completion and return of the survey was deemed to represent informed consent. Focus group participants provided written informed consent.

Consent to publish

All focus group participants provided written informed consent for the publication of any anonymised associated data.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

41669_2024_479_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary file1 The online resource includes the search strategy; characteristics of instruments, articles and grey literature included in the review; characteristics of survey respondents and focus group participants; survey results; and drafts of new modules. (DOCX 1271 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Garfield, K.M., Thornton, G.A., Husbands, S. et al. Identification and prioritisation of items for a draft participant-reported questionnaire to measure use of social care, informal care, aids and adaptations. PharmacoEconomics Open 8, 431–443 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-024-00479-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-024-00479-6