Abstract

Background

Dementia affects about 55 million people worldwide. Demographic change and shifting lifestyles challenge the organization of dementia care. A discrete choice experiment (DCE) was conducted to elicit preferences for living arrangements in dementia in urban and rural regions of Germany.

Methods

Preliminary work included review of previous literature and focus groups. The DCE consists of seven attributes (group size, staff qualifications, organization of care, activities offered, support of religious practice, access to garden, consideration of food preferences) with three levels each. Individuals from the general population between the ages of 50 and 65 years were identified through population registration offices in three rural municipalities and one urban area, and 4390 individuals were approached via postal survey. A hierarchical Bayesian mixed logit model was estimated and interactions with sociodemographic characteristics were investigated.

Results

A total of 428 and 412 questionnaires were returned by rural and urban respondents, respectively. Access to a garden was perceived as the most important attribute (average importance 36.0% in the rural sample and 33.4% in the urban sample), followed by consideration of food preferences (15.8%, 17.8%), staff qualification (14.6%, 15.3%), care organization (11.4%, 12.3%), group size (12.2%, 11.1%), and range of activities (8.0%, 10.1%). The attribute relating to religious practice was given the least importance (2.1%, 0%). Preferences vary according to gender, age, religious beliefs, experience as an informal caregiver, and migrant background.

Conclusion

Heterogeneous preferences for living arrangements for people with dementia were identified. The expansion of concepts with access to natural environments for persons with dementia might be a viable option for the formal care market in Germany. Further research is needed to meet the challenges of setting up and designing innovative living arrangements for people with dementia. Preferences vary by gender, age, religious beliefs, experience as an informal caregiver, and migrant background.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In our discrete choice experiment on preferences for living arrangements for persons with dementia, access to garden was perceived as the most important attribute, followed by consideration of food preferences, staff qualification, care organization, group size, and range of activities. |

Preferences vary by gender, age, religious beliefs, experience as an informal caregiver, and migrant background. |

1 Introduction

Dementia affects about 55 million people worldwide, with an incidence of about 10 million yearly [1]. Global numbers are expected to rise to more than 150 million persons in 2050 [2]. Dementia is known to have psychological, physical, social and economic impact on those affected, their caregivers and the society [3]. In the early stage of dementia, a person usually functions independently. Moderate dementia is typically the longest phase and can last for many years. Participation in daily activities is still possible, while assistance is needed. Persons with severe dementia lose the ability to respond to their environment and require extensive care [4].

International literature shows that a high proportion of people with moderate dementia are cared for at home [5]. However, the number of adult children available to care for their elderly parents is expected to decrease in the future and, accordingly, the provision of good care for persons with dementia is seen as a future challenge in many countries around the world [6, 7].

In the past, institutional care for people with dementia was oriented towards a medical-somatic approach rather than the clinical picture of dementia [8]. Since the mid-1990s, a heterogeneous supply structure with different concepts for the institutional care of persons with dementia has evolved [9]. These concepts include Dementia Special Care Units (DSCUs) and small-scale homelike living units [10]. DSCUs are departments in nursing homes where usually groups of 20–30 persons with dementia are cared for and treated separately from other residents [11]. However, the differences in actual care of the persons with dementia in DSCUs compared with integrative living areas are questionable and it is unknown if the structural differences affect the care of the inhabitants [12]. Small-scale homelike living units usually offer group living for 5–15 residents with dementia and put an emphasis on residents’ choices, autonomy and independence [10, 13]. A number of studies have shown that compared with more traditional settings, small-scale homelike living units may encourage social behaviour, preserve activity performance and positively influence emotional status, while other studies have failed to show these effects [14].

In Germany, the number of persons with dementia in 2021 was close to 1.8 million [15], of which a large part are cared for at home [16]. Projections of the declining potential of adult children to care for their parents in need of care suggest a decline in informal care potential of around 30–40% in the long term [17]. A shift from a perceived ‘duty to care’ to more individualized life plans is also likely to reduce informal care provision, inter alia among migrants [18]. In 2020, the German government published a National Dementia Strategy [19], according to which persons with dementia need housing that is appropriate to their needs and the stage of dementia. While living in their own homes is desirable, alternative living arrangements may be particularly suitable for persons living alone and those with an increased need for care. It is further detailed that the supply of different living concepts has to be differentiated in the coming years, in order to offer individually suitable living and care concepts to persons with dementia [19].

Close to 2500 small-scale homelike living groups for persons with dementia existed in Germany in 2017 [20]. Interestingly, a representative survey was undertaken in 2017 to elicit knowledge, attitudes and experiences with regard to dementia in the German general population. Asked about their expectations towards adequate living and care arrangements for persons with dementia, 28% consider their own household to be particularly suitable and 20% would prefer a small-scale homelike living unit. Another 15% of the population believe that persons with dementia are best cared for in the household of relatives [20]. Interestingly, asking those respondents who either have relatives or friends in need of care or who have accompanied persons in need of care in the past revealed that despite the high preference, only around 2% of persons in need of care lived in small-scale homelike living units. In contrast, nursing homes are preferred by only 5% of the population, but 38% have had to resort to nursing homes in the past [21].

The consideration of individual preferences is a key element of patient-centred care [22]. An involvement of individual needs and expectations in care decisions is associated with better engagement, health, and quality of life [23]. In such decisions, complexity is inevitable, as a number of alternatives exist that are influenced by multiple factors.

The importance of different aspects of healthcare can be elicited with rating scales, e.g., by using Likert scales; however, these scales do not usually consider resource constraints [24]. In contrast, the method of discrete choice experiment (DCE) involves trade-offs and thus reflects actual decision-making processes [24]. The theoretical underpinnings of DCEs, namely the characteristics theory of demand, assumes that goods or services can be valued based on their constituting characteristics (called attributes) [25]. Preferences are assessed by offering respondents a series of hypothetical choice sets, from which they are asked to choose between two or more profiles [26]. Typically, each of the attributes is described by a number of levels, in which the attributes vary across choice sets. The choices made by respondents are then used to estimate the importance of the attributes/levels to the overall utility [27]. DCEs are based on a theory of the behaviour of human preferences, namely random utility theory (RUT), which assumes that respondents behave in a utility-maximizing manner. Thus, data obtained in DCE surveys can be analysed using econometric models that are based on the RUT [26].

DCEs have been broadly used for preference elicitation in healthcare [27]. In addition, a number of DCEs have been undertaken to elicit preferences for long-term care in dementia [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. In the majority of these studies, the general population or caregivers of persons with dementia have been surveyed. Although objectives differ, strong preferences for care by the same person, caregiver expertise, and organizational aspects were found [14].

In this study, a DCE was conducted to elicit preferences for a range of constituting attributes for small-scale living arrangements for persons with dementia. The project is part of a research network investigating health care in demographically declining regions in Germany [37]. Given the challenges outlined above, including the decreasing care potential and the simultaneous increase in persons with dementia, persons from the general public between 50 and 65 years of age from urban and rural regions in Germany were surveyed to derive preferences for the future design of dementia living arrangements.

2 Methods

A DCE was conducted to elicit preferences for living arrangements in dementia in urban and rural regions in Germany. Conduct of the DCE was informed by the Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) checklist for conjoint analyses [38] and the user guide on DCEs issued by the World Health Organization [39].

2.1 Attributes and Levels

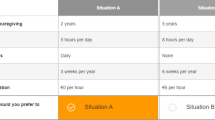

Attributes and levels were developed following the recommendations by Helter and Boehler [40], namely raw data collection, data reduction, removing inappropriate attributes, and wording. A scoping review was conducted to collate published studies in which preferences for living and care concepts for persons with dementia are determined [14], and a systematic review identified studies assessing innovative forms of housing for persons with dementia [41]. Based on the results of these reviews, focus groups with participants from the general public aged 50 years and older aimed to identify important aspects of care arrangements. Four focus groups with a total of 32 participants were conducted. In two of these focus groups, participants were recruited from an urban population, while the other two groups only included people from rural areas. One of the focus groups included people with a Turkish migrant background to investigate intercultural differences. The participants discussed various topics for the case that they themselves suffer from dementia and have to move into a living arrangement, including preferred location, spatial design, group size and composition, care concept, and which activities should be offered. Results were transcribed and qualitative content analysis was performed. Results of the focus groups will be published elsewhere. Themes emerging from this preliminary stage were reduced as proposed by Coast et al. [42]. Wording of the attributes and levels was refined by three researchers (CS, CA, and KH) and discussed in the team. A manageable set of seven attributes with three levels each remained. Table 1 provides an overview of attributes, levels and the hypothesized direction of effects, which resulted from the findings of the scoping review, the systematic review and the focus groups. For example, the attribute ‘group size’ consisted of the levels ‘15 residents’, ‘10 residents’ and ‘5 residents’, with the assumption that residents prefer smaller group sizes over larger groups. The DCE was pretested for comprehensibility with six persons between the age of 50 and 65 years. After the first pretest, some questions and answer options were revised and the order of the questions was changed. After a second round of pretesting with the same people, only minor changes were made.

2.2 Experimental Design

Our experiment contained seven attributes with three levels each, corresponding to 37 = 2187 possible combinations [27]. As it was not feasible to include all combinations in the survey, a fractional factorial main-effects design was constructed using the %MktRuns, %MktEx, and %ChoiceEff autocall macros in SAS V9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). These macros suggest design sizes and produce orthogonal and balanced designs with maximum d-efficiency, which is a commonly used metric in choice design creation. To reduce complexity for survey respondents, a restriction macro was imposed to create partial profile scenarios in which three levels per choice set were held constant [43]. A total of 27 choice tasks were constructed, which were split into three sets with nine tasks each. Each respondent received a questionnaire with one of the three sets and had to choose between two alternatives [34]. No opt-out alternative was provided. An example choice task can be found in the electronic supplementary material (ESM).

2.3 Survey

The sample was compiled by residents’ registration data requested in accordance with Section 34 (3) of the German Registration Act (Bundesmeldegesetz). In Germany, such information can be provided for a clearly defined group of persons if there is public interest. For the urban sample, the registration office of Gelsenkirchen was contacted and for the rural sample, registration offices in municipalities from the Munsterland, a region in north-western Westphalia in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, were approached. The three municipalities with the lowest population density (inhabitants per square kilometre) in 2019 were included for the rural sample, namely Hopsten, Schöppingen, and Wadersloh. The number of persons to approach was estimated according to Johnson and Orme, who recommended a sample size depending on the number of choice scenarios, the number of alternatives, and the number of analysis cells [44, 45]. Assuming a conservative response rate of 8%, a total of 4040 persons, 2020 from the rural population and 2020 from the urban population, were randomly drawn from the registration data. In May 2022, 674 questionnaires of each of the three versions for both rural and urban populations were printed and mailed. Since the response rate from Gelsenkirchen for one of the three survey versions was low, a further 350 people were contacted at the end of June 2022.

The persons contacted received a letter, the questionnaire consisting of 13 pages and a self-addressed return envelope. The first page of the questionnaire contained a vignette in which respondents were asked to imagine that they were diagnosed with moderate dementia. The vignette describes that they have difficulties in everyday activities and notice that they can no longer manage to live independently in their home due to the disease. Respondents were then informed that the survey asks for the optimal housing arrangement and were asked to think primarily about their wishes and needs and not about possible costs. In Germany, long-term care insurance is mandatory and claimants receive benefits according to their care degree [16]. Financing is complex and benefits cover only part of the costs incurred for long-term care. Funding also depends on the type of accommodation and, for example, differs in assisted-living communities. In the case of inpatient care, patients have to pay their own share of the costs for nursing care and must also pay for accommodation, meals, investment costs and vocational training [20]. The full vignette can be found in the ESM.

Apart from the DCE, the survey contained a number of questions related to the hypothetical housing arrangement, namely the place of the housing arrangement, preferred group composition, staff composition, staff gender, staff language, involvement of loved ones, single room versus double room, and questions pertaining to the organization of daily routines. In addition, five best-worst scaling questions in which respondents were asked to tick their most preferred and least preferred activities were part of the survey, the results of which will be reported elsewhere. At the end of the survey, respondents were asked to answer a series of sociodemographic questions, including gender, age, marital status, education, professional education, employment status, religion, religious beliefs, if a relative is or was in need of care, and if yes, if care is or was performed by the respondent.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

The DCE data were analysed using SAS V9.4. Econometric analyses followed the ISPOR guidance for DCEs [46]. Dummy coding was applied. Analysis was based on RUT, assuming that respondents choose the alternative with the highest utility in a choice set [47]. The utility Uni of the respondent n choosing an alternative i for a living arrangement in a choice set s is equal to the sum of Vni, which is an observable component of utility, and εni, which is unobservable to the researcher and treated as a random component (Eq. 1):

where Vni = Xniβ’, with Xni being the observable stochastic component defined by the vector of choice attributes i and β being a vector of coefficients representing the preference weights [46]. Thus, the utility that a respondent gets from choices in our DCE can be expressed by (Eq. 2):

As a first step, the above equation was estimated by a standard conditional logit model. This was used as a starting point and the model was extended to a mixed logit model by specifying the random statement. The mixed logit model was chosen because a considerable heterogeneity was expected in our survey of the general population. Mixed logit models allow for preference heterogeneity and account for correlated observations due to repeated measures within respondents, i.e., allow consideration of the panel nature of the data [46, 48]. A discrete choice hierarchical Bayesian model was used. The prior distribution of the regression coefficients was specified to be normal [48]. Modelling was based on the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm and using the Metropolis-Hastings MCMC approach of Gamerman [49]. The model was specified to perform 30,000 posterior simulation iterations after a burn-in phase of 5000 MCMC draws. Relative importance of the attributes was calculated by dividing the average preference weights of the most preferred level of each attribute by the sum of all best attribute levels [50].

Posterior mean estimates are reported as average preference weights relative to the respective reference levels. Furthermore, 95% Bayesian credible intervals are used to report uncertainty in model estimates. Of note, the interpretation of Bayesian credible intervals differs from that of confidence intervals in the frequentist approach, in that they give the probability that the true estimate lies within the interval, given the observed data [51].

Preference heterogeneity according to female gender, higher age, religious beliefs, informal caregiving experience, and migration background was investigated, with a person being defined to have a migration background if she, he, or at least one parent was not born with German citizenship. Informal care experience was elicited by first asking whether a relative of the respondent was or is in need of care, and if so, whether the care was or is being provided by the respondent. For the assessment of preference heterogeneity, interaction terms between attributes and the individual-specific characteristics were added to the model individually, as done by Larson et al. [52], and Eq. 2 was extended accordingly [53]. Significant interaction effects would indicate that compared with a subgroup of respondents without the specific characteristic, the observed subgroup differed in their average preference weights.

Convergence was checked by assessing trace plots and performing convergence tests. As a measure of goodness of fit, hit probabilities were compared between model specifications. In addition, the deviance information criterion (DIC) was used to compare models.

3 Results

A total of 428 and 412 questionnaires were returned from rural and urban respondents, respectively, corresponding to an overall participation rate of 19%. Sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 2. In the total sample, the majority of respondents were female (57%), married (69%), and full- or part-time employed (68%). In the total sample, 33% of respondents had experience in informal care provision. Those with informal care experience were significantly more likely to be female (73%) than those without informal care experience (53%), and significantly less likely to be in full-time employment (67%) than those without informal care experience (77%). In the rural sample, 56% of respondents considered themselves religious, while in the urban sample, 36% of respondents did so. In the rural and urban samples, 5.6% and 14.1% had a migration background, respectively.

3.1 Results of the Main Analysis

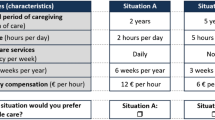

The respondents completed a total of 7142 pairwise comparisons. In all 840 questionnaires received, at least some DCE questions were answered. Excluding respondents with incomplete answers had a negligible impact on the results, with the Pearson’s correlation being >0.999 when comparing the average preference weights [30]. Thus, the analysis was carried out with all responses. No imputation of missing data was performed. Results of the standard conditional logit model can be found in the ESM. The mixed logit models had hit rates of 86%, indicating that the predictions from the model fit the data well. The inter-model comparison of DICs also showed a better model fit for the mixed logit models than for the multinomial logit models for both the rural and urban populations. Posterior mean estimates, 95% Bayesian credible intervals and relative attribute importance are shown in Table 3. Graphical representations of the estimates for the rural and urban samples are shown in Fig. 1.

In both the urban and rural samples, access to garden was perceived as the most important (relative importance: 33.4% in the urban sample and 36.0% in the rural sample) attribute on average, followed by consideration of food preferences (17.8%, 15.8%), staff qualification (15.3%, 14.6%), care organization (12.3%, 11.4%), group size (11.1%, 12.2%), and range of activities (10.1%, 8.0%). The attribute that refers to religious practice was given the least importance. For six of the seven attributes, namely group size, staff qualification, care organization, range of activities, access to garden, and food preferences, average preference weights of the highest level were statistically different from their reference level at the 95% credible interval. This indicates that these six attributes contributed to the decision for a living arrangement made by respondents. For the attribute referring to religious practice, average preference weights for the levels ‘Yes, inside the living arrangement’ and ‘Yes, inside and outside the living arrangement’ are not significantly different from the reference level.

In both samples, pairwise differences in average preference weights between all three levels were statistically significant at the 95% credible interval for the attributes ‘Access to garden’, ‘Nursing staff qualification’ and ‘Group size’. For example, respondents from the rural sample assigned statistically significantly higher preferences to the possibility to access a garden at any time (preference weight: 4.04 [95% Bayesian credible interval 3.63–4.49]) than at fixed times (2.05 [1.76–2.33]).

For most attributes, the average preference weights assigned to levels 2 and 3 were according to the hypothesized direction of preference and thus increase confidence in the theoretical validity of results. However, contrary to the hypothesized direction of preference, a fixed care team was considered more preferable than a single fixed caregiver for the attribute ‘Organization of care’, although this was not statistically significant at the 95% credible interval.

The answers to the additional questions related to the hypothetical housing arrangement can be found in the ESM.

3.2 Preference Heterogeneity

Detailed results on the influence of female gender, higher age, religious beliefs, informal care experience, and migration background can be found in the ESM. A positive sign of the average preference weights indicates a positive effect of the attribute level on preference, whereas a negative average preference weight indicates a negative effect. In the following, effects for which the respective Bayesian credible intervals had the same algebraic sign are reported. Female respondents from the rural sample ascribed higher importance to higher levels of staff qualification and access to garden at any time than male respondents. Likewise, female respondents from the urban sample perceived fixed caregivers and a fixed care team as more important than male respondents and assigned less importance to consideration of food preferences than male respondents. Respondents aged 61–65 years considered fixed care teams as less important compared with younger respondents. Respondents who consider themselves religious ascribed higher importance to levels 2 and 3 of the attribute ‘Support of religious practice’ than respondents who do not report being religious. Respondents from the urban sample with experience in informal care provision ascribed a higher importance to higher levels of staff qualification and a fixed caregiver than respondents without such experience. Respondents with experience in informal caregiving from the urban sample considered support of religious practice inside the living arrangement and garden access at any time as more important. Results indicated a lower importance of staff qualification, a higher importance of small group sizes, and full consideration of food preferences in individuals with a migration background in the rural sample compared with the urban sample. Respondents with a migration background from the urban sample ascribe less importance to activities according to preferences, access to garden at any time, and level 2 of the attribute regarding food preferences, while support of religious practice inside the living arrangement is of higher importance.

4 Discussion

This study sought to elicit preferences for housing arrangements for persons with dementia. A total of 840 questionnaires and 7142 pairwise comparisons were included in our analysis. In both the urban and rural samples, access to garden was perceived as the most important attribute, followed by consideration of food preferences, staff qualification, care organization, group size, and range of activities. The attribute that refers to religious practice was given the least importance. For all attributes except the attribute that refers to religious practice, average preference weights of the highest level were statistically different from their reference level at the 95% credible interval. Results of the mixed logit models appear consistent and valid, as they largely conform to prior hypotheses.

Internationally, a number of DCEs were conducted to investigate similar research questions. The strong preference for access to the garden at any time was partly confirmed by Milte et al. [54], who conducted a DCE to elicit preferences for nursing home characteristics among nursing home residents who were cognitively capable of participating (n = 126) or family member proxies (n = 416). Interestingly, a high level of access to outside and gardens (‘whenever they want’) was preferred over the level ‘sometimes’ by residents, while the reverse was true for proxy participants. The authors speculate that this may be related to safety concerns about unrestricted garden access on the part of relatives. Since in our survey respondents were asked to imagine themselves as residents, these concerns may play a smaller role in our results. Literature reviews assessing the effects of gardens on institutionalized persons with dementia indicate a beneficial effect on agitation, behaviour, physical activity, and quality of life [55, 56]. Besides the high preference for garden access, the results of the additional questions in our survey reveal that a considerable fraction (28%) of respondents would favour living on a farm, which might also show the importance of the outdoor component. Corresponding concepts have already been described and evaluated, especially in The Netherlands and Norway, and are mainly known as Green Care Farms [57, 58]. Green Care is the merger of the agricultural and health care sectors, and includes activities such as feeding animals, milking cows, or gardening [58]. While there are around 1000 care farms each in The Netherlands and Norway, estimates for Germany are much lower [59]. Results of our DCE indicate that the expansion of such concepts with a focus on outdoor activities for persons with dementia might be a viable option for the formal care system in Germany.

Respondents ascribed high importance to the consideration of food preferences. This finding was not confirmed by Sawamura et al. [34], who conducted a DCE to measure preferences for long-term care facility services among adults aged 50–65 years in eight cities in Japan. The mail-in survey contained one of two vignettes of an 80-year-old person with either dementia or a fracture. While necessity of relocation due to medical deterioration was perceived as most important, followed by distance from present residence, waiting time, and room, the attribute ‘individual choice for daily schedules/meals’ was given a lower priority. Milte et al. [60] conducted a DCE to investigate residents’ and proxies’ food preferences in nursing homes and found that proxies’ preferences were highly influenced by taste, while residents ascribed highest importance to eating at a set time.

With regard to nursing staff qualification, respondents of our study ascribed a strong preference to staff with a 3-year training period and advanced dementia training. Similarly, respondents in the study by Chester et al. [28] were strongly in favour of staff with full training in dementia care, and Groenewoud et al. [30] found a high preference for the institution being specialized in dementia care.

The attribute ‘organization of care’ had a relative importance of 11% in the rural sample and 12% in the urban sample, and the level ‘fixed care team’ received higher average preference weights than ‘fixed caregiver’. This finding is in contrast to DCEs on long-term care services conducted in other countries, in which the attribute on care delivery had high importance compared with other attributes, and care by the same person was highly preferred over other levels [28, 33]. These differences might be due to different settings in these two studies, cultural differences, higher severities of dementia, and the fact that respondents in these two studies were asked to choose care scenarios for other persons and not for themselves.

We assessed interactions with sociodemographic characteristics, namely gender, age, religious beliefs, informal caregiving experience, and migration background. The analysis revealed plausible patterns. For example, respondents from both the rural and urban samples who indicated in the questionnaire that they were religious had a significantly stronger preference for higher levels of the attribute concerning support of religious practice. With regard to migration background, small sample sizes must be taken into account. Differences between individuals with migration background from the rural and urban samples might be due to different countries of origin (of the parents). Overall, the differences according to sociodemographic characteristics mainly concern the preferences for different forms of care organization and the importance of support of religious practice. Thus, the differences discovered can provide clues for a target group-specific design of living arrangements.

Our study has a number of limitations. First, the external validity of our findings might be impaired by non-response bias. For example, the high participation rate of females might potentially impair transferability of study findings. Analogous to Lehnert et al. [61], it can be assumed that certain population strata are overrepresented. Compared with official statistics, participation rates of people with a migration background, unemployed individuals, and people with a low educational status seems to be proportionally low, although this cannot be ascertained based on the registration offices’ data.

Second, the survey was directed towards the general population between 50 and 65 years and not towards persons with dementia. Actual recipients of care are older on average and it cannot be ruled out that preferences change in the event of dementia. However, participants of our survey are at an age where they are considering their own future care and some of them have parents in need of care. Thus, our results are meant to contribute to the future differentiation of care. Furthermore, while literature suggests that preferences of persons with dementia differ from proxies’ preferences [62], it is unclear whether preferences for one’s own care change in the event of dementia. For example, Cohen-Mansfield et al. [63] found that the preferences for leisure activities of persons with dementia did not differ between past and present ratings. In future surveys of this kind with a sufficiently large sample, it would be desirable to differentiate according to whether the respondents already have experience with informal care of people with dementia or not.

Third, a total of seven attributes were used in our DCE to describe hypothetical living arrangements, and thus our study can only represent preferences for housing types based on these seven attributes. This number was chosen to keep the cognitive burden manageable and it cannot be ruled out that the inclusion of additional attributes might have altered results. However, the derivation of attributes followed published guidance and further aspects of interest have been included in the additional questions of our survey.

Fourth, a potential limitation in the interpretation of the findings arises from the definition of the lowest attribute levels. For example, the lowest level of the attribute ‘access to garden’ is ‘no garden’, which can be interpreted as ‘zero’. In contrast, the lowest level of the attribute ‘range of activities’ was chosen to be ‘predefined activities’, and not ‘no activities’. Flynn et al. [64] argue that a meaningful comparison of the utility of moving from the first level to a higher level is only possible if the first levels represent a measure of ‘zero’. However, offering no activities at all or completely unqualified staff working in the living arrangement was not considered realistic. Therefore, it was decided to define the lowest possible, but still realistic, values as the lowest levels.

Fifth, it has to be noted that some other factors might explain the strong preference for access to garden in our DCE. The level 1 (‘No’) of the ‘Access to garden’ attribute could have been perceived as a deprivation of personal freedom or independence, which caused respondents to strongly favour the higher levels of this attribute. In addition, filling out DCE surveys is a cognitively demanding task. Our experiment did not offer an opt-out option and thus it was mandatory to choose one of the two alternatives. This approach was chosen because the vignette describes how a person can no longer manage to live alone at home and therefore inevitably has to receive institutional care. Another reason was the fairly long survey and the desire to reduce the number of respondents who opt-out due to the complexity of the choice tasks [65]. As a consequence, it might be possible that respondents focused on a specific attribute such as ‘Access to garden’ in order to reduce cognitive burden and based their choice solely on this attribute. However, bias induced by such simplistic decision rules might rather appear in highly efficient designs [66], while our design had a manageable number of seven attributes with level overlap. Concluding, the absence of an opt-out option must be taken into account when interpreting the results, since in reality not all respondents are expected to move into a housing unit.

Sixth, we did not account for the costs of the living arrangement, which might induce hypothetical bias, as our choice tasks do not fully reflect reality [67]. Although financial aspects have been addressed by the participants of the focus groups, we decided to not include willingness-to-pay (WTP) in our DCE. The aim of the survey was in fact to elicit wishful thinking about housing in the event of dementia, and respondents were explicitly asked to disregard costs. It was feared that the inclusion of a WTP attribute would lead to a strong focus on costs, especially in low-income groups. Furthermore, as residents do not directly account for the entire costs, they cannot be expected to know with certainty the amount they would be willing to pay in the future. We also did not include any other continuous attributes. In addition to monetary variables, the inclusion of a time variable would have been an option, in order to be able to estimate corresponding trade-offs. We did not include the waiting time for a place in the facility as it was not among the attributes perceived as important in the focus groups. Theoretically, we could have defined group size as a continuous attribute to find out how much larger the group could be in order to get an improvement in another attribute. However, while this might be of interest for future analyses, the main focus of this study was to test the basic hypotheses and to identify preference differences in terms of sociodemographic characteristics.

5 Conclusion

The results of our DCE and the additional questions offer differentiated insights into preferences with regard to the optimal design of living arrangements in the case of dementia. Overall findings indicate that the ability to access outdoor areas is of great importance to respondents. According to our results, the expansion of concepts with a focus on outdoor access and activities for persons with dementia is advisable. In these living concepts, it is of great importance to consider the individual food preferences of the residents, followed by qualified staff, a permanent care team and a small group size. Other aspects, such as support of religious practice, are of minor importance. While overall preferences are comparable between the rural and urban samples, investigations of interactions with sociodemographic characteristics found heterogeneities with respect to a large number of attributes in both samples. Concluding, the findings of our survey study offer important clues for the spatial and organizational design of future living arrangements for persons with dementia. The results will be discussed in a stakeholder workshop with experts in the field, in order to derive recommendations for health policy.

References

World Health Organization. Dementia. 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia. Accessed 29 Nov 2022.

GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(2):e105–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8.

World Health Organization. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025. 2017. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-action-plan-on-the-public-health-response-to-dementia-2017---2025. Accessed 29 Nov 2022.

Alzheimer’s Association. Stages of Alzheimer’s. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/stages#:~:text=Alzheimer’s%20disease%20typically%20progresses%20slowly,progress%20through%20the%20stages%20%E2%80%94%20differently. Accessed 4 Oct 2023.

Matthews FE, Bennett H, Wittenberg R, Jagger C, Dening T, Brayne C. Who lives where and does it matter? Changes in the health profiles of older people living in long term care and the community over two decades in a high-income country. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(9): e0161705.

Federal Ministry of Health. Leuchtturmprojekt Demenz. 2011. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/service/publikationen/details/leuchtturmprojekt-demenz.html. Accessed 29 Nov 2022.

Moyle W. The promise of technology in the future of dementia care. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(6):353–9.

Kok JS, Berg IJ, Scherder EJA. Special care units and traditional care in dementia: relationship with behavior, cognition, functional status and quality of life—a review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra. 2013;3:360–75.

Sharkey SS, Hudak S, Horn SD, James B, Howes J. Frontline caregiver daily practices: a comparison study of traditional nursing homes and the Green House project sites. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):126–31.

Palm R, Bartholomeyczik S, Roes M, Holle B. Structural characteristics of specialised living units for people with dementia: a cross-sectional study in German nursing homes. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2014;8(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-8-39.

Kok JS, Nielen MMA, Scherder EJA. Quality of life in small-scaled homelike nursing homes: an 8-month controlled trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0853-7.

Palm R, Holle B. Forschungsbericht der Studie DemenzMonitor. Veröffentlichungsreihe des Deutschen Zentrums für Neurodegenerative Erkrankungen e.V. (DZNE), Standort Witten; 2016.

Wolf-Ostermann K, Worch A, Fischer T, Wulff I, Gräske J. Health outcomes and quality of life of residents of shared-housing arrangements compared to residents of special care units-results of the Berlin DeWeGE-study. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(21–22):3047–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04305.x.

Speckemeier C. Preferences for attributes of long-term care in dementia: a scoping review of multi-criteria decision analyses. J Public Health. 2023;31(10):1597–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-022-01743-x.

Statista. Prognostizierte Entwicklung der Anzahl von Demenzkranken im Vergleich zu den über 65-Jährigen in Deutschland bis 2050. 2023. Available at: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/245519/umfrage/. Accessed 29 Nov 2022.

Bartholomeyczik S, Halek M. Pflege-Report 2017 "Die Versorgung der Pflegebedürftigen“. Stuttgart: Schattauer; 2017.

Dudel C. Vorausberechnung des Pflegepotentials von erwachsenen Kindern für ihre pflegebedürftigen Eltern. Sozialer Fortschritt. 2015;64(1–2):14–24.

Kohls M. Pflegebedürftigkeit und Nachfrage nach Pflegeleistungen von Migrantinnen und Migranten im demographischen Wandel. (Forschungsbericht / Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF) Forschungszentrum Migration, Integration und Asyl (FZ), 12). Nürnberg: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF) Forschungszentrum Migration, Integration und Asyl (FZ) 2012.

BMFSFJ. Nationale Demenzstrategie. 2022. https://www.bmfsfj.de/bmfsfj/themen/aeltere-menschen/demenz/nationale-demenzstrategie. Accessed 29 Nov 2022.

Klie T, Heislbetz C, Schuhmacher B, Keilhauer A, Rischard P, Bruker C. Ambulant betreute Wohngruppen. Bestandserhebung, qualitative Einordnung und Handlungsempfehlungen. Abschlussbericht. AGP Sozialforschung und Hans-Weinberger-Akademie (Hrsg.). Berlin: Studie im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für Gesundheit; 2017.

Klie T. Pflegereport 2018. Pflege vor Ort – gelingendes Leben mit Pflegebedürftigkeit. 2018. https://www.dak.de/dak/download/dak-pflegereport-2018-pdf-2126422.pdf. Accessed 29 Nov 2022.

Yu X, Bao H, Shi J, Yuan X, Qian L, Feng Z, Geng J. Preferences for healthcare services among hypertension patients in China: a discrete choice experiment. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12): e053270. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053270.

Wilberforce M, Challis D, Davies L, Kelly MP, Roberts C, Loynes N. Person-centredness in the care of older adults: a systematic review of questionnaire-based scales and their measurement properties. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0229-y.

Wijnen BF, van der Putten IM, Groothuis S, et al. Discrete-choice experiments versus rating scale exercises to evaluate the importance of attributes. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(4):721–8. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737167.2015.1033406.

Clark MD, Determann D, Petrou S, Moro D, de Bekker-Grob EW. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(9):883–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0170-x.

Soekhai V, Whichello C, Levitan B, et al. Methods for exploring and eliciting patient preferences in the medical product lifecycle: a literature review. Drug Discov Today. 2019;24(7):1324–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2019.05.001.

Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: a user’s guide. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(8):661–77. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200826080-00004.

Chester H, Clarkson P, Davies L, Sutcliffe C, Roe B, Hughes J, et al. A discrete choice experiment to explore carer preferences. Qual Ageing. 2017;18(1):33–43.

Chester H, Clarkson P, Davies L, Sutcliffe C, Davies S, Feast A, et al. People with dementia and carer preferences for home support services in early-stage dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(2):270–9.

Groenewoud S, Van Exel NJ, Bobinac A, Berg M, Huijsman R, Stolk EA. What influences patients’ decisions when choosing a health care provider? measuring preferences of patients with knee arthrosis, chronic depression, or Alzheimer’s disease, using discrete choice experiments. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(6):1941–72.

Jasper R, Chester H, Hughes J, Abendstern M, Loynes N, Sutcliffe C, et al. Practitioners preferences of care coordination for older people: a discrete choice experiment. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2018;61(2):151–70.

Kampanellou E, Chester H, Davies L, Davies S, Giebel C, Hughes J, et al. Carer preferences for home support services in later stage dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(1):60–8.

Nieboer AP, Koolman X, Stolk EA. Preferences for long-term care services: willingness to pay estimates derived from a discrete choice experiment. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(9):1317–25.

Sawamura K, Sano H, Nakanishi M. Japanese public long-term care insured: preferences for future long-term care facilities, including relocation, waiting times, and individualized care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(4):350.e9-20.

Teahan Á, Walsh S, Doherty E, O’Shea E. Supporting family carers of people with dementia: a discrete choice experiment of public preferences. Soc Sci Med. 2021;287: 114359.

Walsh S, O’Shea E, Pierse T, Kennelly B, Keogh F, Doherty E. Public preferences for home care services for people with dementia: a discrete choice experiment on personhood. Soc Sci Med. 2020;245: 112675.

Leibniz Science Campus Ruhr. https://lscr.rwi-essen.de/en/, Accessed 20 Sept 2023.

Bridges JFP, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. Conjoint analysis applications in health–a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013.

World Health Organization. How to conduct a discrete choice experiment for health workforce recruitment and retention in remote and rural areas: a user guide with case studies. 2012. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/586321468156869931/pdf/NonAsciiFileName0.pdf. Accessed 6 Jun 2023.

Helter TM, Boehler CEH. Developing attributes for discrete choice experiments in health: a systematic literature review and case study of alcohol misuse interventions. J Subst Use. 2016;21(6):662–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/14659891.2015.1118563.

Speckemeier C, Niemann A, Weitzel M, Abels C, Höfer K, Walendzik A, Wasem J, Neusser S. Assessment of innovative living and care arrangements for persons with dementia: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):464.

Coast J, Al-Janabi H, Sutton EJ, Horrocks SA, Vosper AJ, Swancutt DR, Flynn TN. Using qualitative methods for attribute development for discrete choice experiments: issues and recommendations. Health Econ. 2012;21(6):730–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1739.

Kessels R, Jones B, Goos P. Bayesian optimal designs for discrete choice experiments with partial profiles. Journal of Choice Modelling. 2011;4(3):52–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1755-5345(13)70042-3.

Orme B. Sample size issues for conjoint analysis studies. Sequim: Sawtooth Software Technical Paper; 1998.

Johnson R, Orme B. Getting the most from CBC. Sequim: Sawtooth Software Research Paper Series, Sawtooth Software; 2003.

Hauber AB, González JM, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, et al. Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete choice experiments: a report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2016;19(4):300–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.004.

McFadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In: Zarembka P, editor. Frontiers in econometrics. New York: Academic Press; 1973.

Hensher DA, Rose JM, Greene WH. Applied choice analysis: a primer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Gamerman D. Sampling from the posterior distribution in generalized linear models. Stat Comput. 1997;7:57–68. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018509429360.

Hoedemakers M, Karimi M, Jonker M, Tsiachristas A, Rutten-van MM. Heterogeneity in preferences for outcomes of integrated care for persons with multiple chronic diseases: a latent class analysis of a discrete choice experiment. Qual Life Res. 2022;31(9):2775–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03147-6.

Hespanhol L, Sain Vallio CS, Menezes Costa LM, Saragiotto BT. Understanding and interpreting confidence and credible intervals around effect estimates. Braz J Phys Ther. 2019;23(4):290–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjpt.2018.12.006.

Larson E, Vail D, Mbaruku GM, Kimweri A, Freedman LP, Kruk ME. Moving toward patient-centered care in africa: a discrete choice experiment of preferences for delivery care among 3,003 Tanzanian women. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8): e0135621. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135621.

Umar N, Quaife M, Exley J, Shuaibu A, Hill Z, Marchant T. Toward improving respectful maternity care: a discrete choice experiment with rural women in northeast Nigeria. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(3): e002135. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002135.

Milte R, Ratcliffe J, Chen G, Crotty M. What characteristics of nursing homes are most valued by consumers? A discrete choice experiment with residents and family members. Value Health. 2018;21(7):843–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.11.004.

Whear R, Coon JT, Bethel A, Abbott R, Stein K, Garside R. What is the impact of using outdoor spaces such as gardens on the physical and mental wellbeing of those with dementia? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(10):697–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.05.013.

Howarth DM, Brettle PA, Hardman DM, Maden M. What evidence is there to support the impact of gardens on health outcomes? Manchester: University of Salford; 2017. http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/47230/. Accessed 29 Nov 2022.

de Bruin SR, Pedersen I, Eriksen S, et al. Care farming for people with dementia; what can healthcare leaders learn from this innovative care concept? J Healthc Leadersh. 2020;12:11–8. https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S202988.

de Boer B, Hamers JPH, Zwakhalen SMG, et al. Green care farms as innovative nursing homes, promoting activities and social interaction for people with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(1):40–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.10.013.

Graeske J, Nisius K, Renaud D. Bauernhöfe für Menschen mit Demenz – Ist-Analyse zu Verteilung und Strukturen in Deutschland. 2020. Available at: https://www.monitor-pflege.de/kurzfassungen/kurzfassungen-2020/mopf-02-2020-graeske. Accessed 29 Nov 2022.

Milte R, Ratcliffe J, Chen G, Miler M, Crotty M. Taste, choice and timing: Investigating resident and carer preferences for meals in aged care homes. Nurs Health Sci. 2018;20(1):116–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12394.

Lehnert T, Günther OH, Hajek A, Riedel-Heller SG, König HH. Preferences for home- and community-based long-term care services in Germany: a discrete choice experiment. Eur J Health Econ. 2018;19(9):1213–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-018-0968-0.

Wilkins JM, Locascio JJ, Gomez-Isla T, Hyman B, Blacker D. Projection in proxy assessments of everyday preferences for persons with cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2023;31(4):254–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2022.12.005.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Gavendo R, Blackburn E. Activity Preferences of persons with dementia: An examination of reports by formal and informal caregivers. Dementia (London). 2019;18(6):2036–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301217740716.

Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, Coast J. Best–worst scaling: what it can do for health care research and how to do it. J Health Econ. 2007;26(1):171–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301217740716.

Veldwijk J, Lambooij MS, de Bekker-Grob EW, Smit HA, de Wit GA. The effect of including an opt-out option in discrete choice experiments. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11): e111805.

Flynn TN, Bilger M, Malhotra C, Finkelstein EA. Are efficient designs used in discrete choice experiments too difficult for some respondents? A case study eliciting preferences for end-of-life care. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(3):273–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0338-z.

Quaife M, Terris-Prestholt F, Di Tanna GL, Vickerman P. How well do discrete choice experiments predict health choices? A systematic review and meta-analysis of external validity. Eur J Health Econ. 2018;19(8):1053–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-018-0954-6.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of the focus groups for their valuable input into the design of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was granted exemption from requiring ethics approval by the Ethics Committee of the University of Duisburg-Essen on 3 October 2023, as no health-related information was collected and participants remained anonymous.

Consent to Participate

Respondents were informed about the voluntary participation, the anonymous nature of the survey and the objectives, the use of results and the handling of data. Due to the anonymous nature of the study, participants consented to their participation in the study.

Consent for Publication

No data on individual persons are contained in the manuscript.

Code Availability

We used SAS V9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) codes for our analyses. The codes are available at https://documentation.sas.com/.

Availability of Data And Materials

The datasets analysed are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest

Christian Speckemeier, Carina Abels, Klemens Höfer, Anja Niemann, Jürgen Wasem, Anke Walendzik, and Silke Neusser declare they have no competing interests.

Funding

This project was funded by the Leibniz Science Campus Ruhr.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design of the study. Attributes and levels were developed and refined by CS, CA and KH. Statistical analysis was performed by CS. CS wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was critically revised by CA, KH, AN, JW, AW and SN. The final version of the manuscript was read and approved by all authors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Speckemeier, C., Abels, C., Höfer, K. et al. Preferences for Living Arrangements in Dementia: A Discrete Choice Experiment. PharmacoEconomics Open 8, 65–78 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-023-00452-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-023-00452-9