Abstract

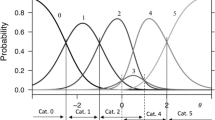

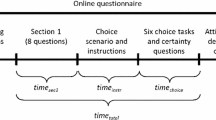

This paper explores the relationship between rating scales and response style using experimental data from a sample of 1500 households of the Innovation Panel (2008) which is part of the Understanding Society database. Two random groups of individuals are being asked about their level of job satisfaction using a self-assessment questionnaire through two (7 and 11 points) rating options. By comparing the two groups, we explore the effects of the different rating scales on Extreme Response Style (ERS). The experimental design of the data enables us to show that both high and low Extreme Response Style (ERS) are correlated with personal and demographic characteristics. In addition, when comparing the shorter to a longer scale, we show that the survey design may generates tendency to choose responses at the extreme values of the distribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Positive psychology is a well-developed branch of research where the study of positive emotions or positive traits are shown to affect happiness; for a reference see Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000)

For a reference on the measurement of satisfaction with life scale see Pavot and Diener (2008)

The two groups are statistically not different in observable terms.

Given that the two groups are randomly allocated in one of the treatment condition, there should not be any statistical difference in observables characteristics. We have provided a randomization test to check any difference for the main variables used in the regression as shown in Table 3.

Beyond the issue of the question format in the case of attitudinal surveys a respondent task might be to measure e.g. his own life satisfaction based on an ordinal scale and very often the thresholds are individual-specific (Pudney 2011).

Another route to control for ERS is to use different unrelated items (Baumgartner and Steenkamp 2001) and compute the individual ERS as the standard deviation of the item score for each respondent.

The main reason why we are grouping the second most extreme responses (in both high and low directions) is due to the very few observations we have (specially for lower ERS) when using only the most extreme responses. Further statistics (available upon request) show that there are only 18 observations for lower ERS when using only the most extreme outcome which are insufficient to carry any meaningful estimation.

We claim that the two groups are actually “comparable” given their observed characteristics. A potential limitation of this data is that they do not account for the influence of the substantive individual trait. For example, a respondent who consistently selects the highest possible score category for each item may in reality possess a very high level of the substantive trait. The experimental design of this study provides empirical support for the correlation between the survey design and self-assessed job satisfaction but given the cross-sectional nature of the data there are substantive personal traits that cannot be entirely accounted for by the inclusion of observable individual controls.

We have also further validated the results by construction ERS with only the two extreme rating scales, the results are the same both in significance and magnitude.

For a reference see: Austin et al. (2006)

References

Austin, E.J., Deary, I.J., & Egan, V. (2006). Individual differences in response scale use: Mixed Rasch modelling of responses to NEO-FFI items. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(6), 1235–1245.

Bachman, J., & O’Malley, P. (1984). Yea-saying, nay-saying, and going to extremes: Black-white differences in response styles. Public Opinion Quartely, 48(2), 491–509.

Baumgartner, H., & Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M. (2001). Response styles in marketing research: A cross-national investigation. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 143–156.

Berg, I.A., & Colier, J.S. (1953). Personality and group differences in extreme response sets. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 13, 164–169.

Böckerman, P., & Ilmakunnas, P. (2009). Unemployment and self-assessed health: Evidence from panel data. Health Economics, 18(2), 161–179.

Brown, D., & McIntosh, S. (2003). Job Satisfaction in the Low Wage Service Sector. Applied Economics, 35(10), 1241–1254.

Bruggemann, A. (1974). Zur Unterscheidung verschiedener Formen von Arbeitszufriedenheit [The differentiation of different forms of work satisfaction]. Arbeit und Leistung, 28, 281–284.

Bussing, A., Bissels, T., Fuchs, V., & Perrari, K.-M. (1999). A dynamic model of work satisfaction: Qualitative approaches. Human Relations, 52(8), 999–1028.

Clark, A.E. (1997). Job satisfaction and gender: Why are women so happy at work?. Labour Economics, 4(4), 341–372.

Clark, A.E. (1999). Are wages habit-forming? evidence from micro data. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 39, 179–200.

Clark, A.E., & Oswald, A.J. (1994). Unhappiness and unemployment. Economic Journal, 104, 648–659.

Clark, A.E., & Oswald, A.J. (1996). Satisfaction and comparison income. Journal of Public Economics, 61, 359–381.

Clark, A.E., Oswald, A.J., & Warr, P. (1996). Is job satisfaction U-shaped in age?. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 69, 57–81.

Conti, G., & Pudney, S. (2011). Survey design and the analysis of satisfaction. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(3), 1087–1093.

Corrado, G., Corrado, L., & Santoro, E. (2013). On the individual and social determinants of neighbourhood satisfaction and attachment. Regional Studies, 47(4), 544–562.

Diener, E., & Emmons, R.A. (1984). The independence of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(5), 1105–1117.

Gazioglu, S., & Tansel, A. (2013). Management-employee relations, firm size and job satisfaction. IZA Discusion papers No. 7308.

Greenleaf, E. (1992). Measuring extreme response style. Public Opinion Quartely, 56, 328–351.

Hui, C.H., & Triandis, H.C. (1985). The instability of response sets. Public Opinion Quarterly, 49, 253–260.

Idsona, T.L. (1999). Establishment size, job satisfaction and the structure of work. Applied Economics, 22(8), 1007–1018.

Johnson, T., Kulesa, P., Llc, I., Cho, Y.I., & Shavitt, S. (2005). The relation between culture and response styles: Evidence from 19 countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36, 264–277.

Kammann, R., & Flett, R. (1983). Affectometer 2: A scale to measure current level of general happiness. Australian Journal of Psychology, 35(2), 259–265.

Kankaras, M., Vermunt, J.K., & Moors, G.B.D. (2011). Measurement equivalence of ordinal items: A comparison of factor analytic, item response theory, and latent class approaches. Sociological Methods and Research, 40(2), 279–310.

Kieruj, N.D., & Moors, G. (2010). Variations in Response Style Behavior by Response Scale Format in Attitude Research. International Journal Public Opinion Research, 22(3), 320–342.

Kieruj, N.D., & Moors, G. (2013). Reponse style behavior: Question format dependent or personal style?. Quality & Quantity, 47, 193–211.

Lewis, N.A., & Taylor, J.A. (1955). Anxiety and extreme response preferences. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 15, 111–116.

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 22(140), 55.

Liu, Y., Wu, D.A., & Zumbo, B.D. (2010). The impact of outliers on cronbach’s coefficient alpha estimate of reliability: Ordinal/rating scale item responses. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70(1), 5–21.

Locke, E.A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Dunnette, M D. (Ed.) Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1297–1349).

Lozano, L.M., Garcia-Cueto, E., & Muniz, J. (2008). Effect of the number of response categories on the reliability and validity of rating scales. Methodology, 4, 73–79.

Marin, G., Gamba, R.J., & Marin, B.V. (1992). Extreme response style and acquiescence among hispanics. The role of acculturation and education. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 23(4), 498–509.

Neumann, L., & Neumann, Y. (1981). Comparison of six lengths of rating scales: Students’ attitudes toward instruction. Psychological Reports, 48, 399–404.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment, 5(2), 164–172.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152.

Pudney, S. (2010). An experimental analysis of the impact of survey design on measures and models of subjective wellbeing. ISER Working Paper Series No. 2010–20.

Pudney, S. (2011). Perception and retrospection: The dynamic consistency of responses to survey questions on wellbeing. Journal of Public Economics, 95(34), 300–310.

Sarpa, S.K. (2010). A jacknife maximum likelihood estimator for the probit model. Applied Economcis Letters, 9(2), 73–74.

Schutz, H.G., & Rucker, M.H. (1975). A comparison of variable configurations across scale lengths: An empirical study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 35, 319–324.

Seligman, M.E.P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology - an introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5–14.

Understanding Society: Innovation Panel, Waves1-4. (2008). University of Essex, Institute for Social and 427 Economic Research; Colchester, Essex: UK Data archive [distributor], SN: 6849.

Wooldridge, J.M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Corrado, L., Joxhe, M. The Effect of Rating Scale on Response Style: Experimental Evidence for Job Satisfaction. J well-being assess 4, 57–73 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41543-020-00026-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41543-020-00026-0