Abstract

After work, employees often share their work experiences with their partners, yet the consequences of these work-related conversations remain poorly understood. In this study with dual-earner couples, we investigate the daily consequences of sharing positive and negative work events with a partner regarding both employees’ and their partners’ affect and work-related self-esteem. Throughout a workweek, 73 heterosexual dual-earner couples completed questionnaires after work and at bedtime. Dyadic multilevel analyses showed that sharing positive work events was positively associated with employees’ positive affect but not with partners’ positive affect. Sharing negative work events showed no significant association with the negative affect of either employees or partners. While sharing positive work events was not associated with employees’ self-esteem, it was negatively associated with partners’ self-esteem. Furthermore, sharing negative work events was negatively associated with partners’ self-esteem, but did not affect employees’ self-esteem. Our study extends existing research on work-related conversations, considering self-esteem as an outcome and adopting a dyadic perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Employees often share their workday experiences, such as positive customer feedback or having a conflict with a colleague, with their significant others after work (i.e., social sharing; Rimé, 2009). Prior studies have shown that positive work-related conversations and leveraging positive work events are associated with decreased negative affect and increased positive affect at bedtime (Tremmel et al., 2018) as well as increased family satisfaction and work–family balance (Ilies et al., 2017). Conversely, sharing negative work events has been associated with heightened negative affect at bedtime (Tremmel et al., 2018).

Although sharing work-related events with a partner is an inherently dyadic experience, previous research (e.g., Ilies et al., 2017; Tremmel et al., 2018) has rarely considered the consequences of social sharing for both the sharing and the listening partner (for an exception see Hicks & Diamond, 2008). However, considering the outcomes of dyadic interactions for both partners is essential as it is unclear whether behaviors that contribute to employees’ well-being are equally beneficial, neutral, or even harmful to the partner’s well-being. For instance, while receiving social support from a partner has been associated with increased psychological detachment from work, providing social support has been shown to reduce detachment from work for the support-providing partner (Haun et al., 2017). Hence, it is important to consider both partners’ perspectives simultaneously when formulating recommendations for improving dual-earner couples’ well-being.

To close this gap in the literature, this study examines how employees’ daily social sharing with their partner relates to both partners’ daily positive and negative affect, as well as their work-related self-esteem at the end of the day. Using a daily diary design with dual-earner couples, we investigate the dyadic consequences of sharing both positive and negative work events with partners.

We contribute to the literature in several ways. First, we expand upon the limited research on work-related conversations (cf. Tremmel et al., 2018). Previous studies into sharing emotional events did not specifically focus on work-related content (Hicks & Diamond, 2008) or concentrated solely on either positive or negative conversations (e.g., Baranik et al., 2017; Culbertson et al., 2012; Ilies et al., 2015, 2017). Others narrowly focused on specific work events, such as customer mistreatment, social conflicts, or perceived prosocial impact (Baranik et al., 2017; Tremmel et al., 2018). In contrast, our study provides a comprehensive perspective on work-related conversations by jointly investigating conversations about positive and negative work events.

Second, adopting a dyadic perspective allows for the investigation of differential consequences of work-related conversations for both individuals within a couple, and enhances our understanding of crossover processes in couples (Hobfoll et al., 2018). By examining how discussions about work-related successes and challenges impact not only employee but also partner outcomes, we contribute to a comprehensive understanding of work-related conversations.

Third, our focus on work-related self-esteem as an outcome, in addition to positive and negative affect, aligns with the call to investigate the broader spectrum of outcomes resulting from work-related conversations (Tremmel et al., 2018). While affect has been frequently studied as an outcome of social sharing (Peters et al., 2018), self-esteem has rarely been considered as an outcome measure. However, given that hearing about one’s partner’s success and failures at work may prompt individuals to engage in social comparison processes, wherein they evaluate themselves against their partners (Beach et al., 1996), self-esteem emerges as a pertinent, yet understudied outcome. Previous research provided first evidence that individuals’ daily work-related levels of self-esteem may cross over to their partners (Neff et al., 2012). Thus, investigating the link between social sharing of positive and negative work events and partners’ self-esteem can contribute to a deeper understanding of this crossover process. Self-esteem is an important predictor of individuals’ psychological well-being (Sowislo & Orth, 2013) as well as work-related outcomes such as job satisfaction and counterproductive work behavior (Kuster et al., 2013).

Theoretical Background

Sharing Affective Work Events

Affective events theory describes affective events as occurrences that commonly elicit emotional responses from individuals (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). These emotional reactions are rooted in cognitive appraisal processes (Lazarus, 1991), wherein individuals categorize the event in terms of valence, intensity, and their perceived coping potential. According to the social sharing of emotion theory (Rimé, 2009), following emotional experiences, individuals possess a strong inclination to share these experiences with others. Through sharing affective events, individuals aim to seek clarification, assign meaning, obtain support, and find an outlet for their emotions (Gable et al., 2004; Rimé, 2009). Sharing positive work events with one’s partner might involve recounting how they solved a work-related problem, receiving positive feedback, or experiencing a sense of competence. Conversely, sharing negative work events may encompass discussing hindrances in goal attainment, technical difficulties with work equipment, or interpersonal conflicts (cf. Ohly & Schmitt, 2015).

In this paper, we focus on exploring the effects of sharing work events on positive and negative affect, as well as self-esteem. Affect refers to an individual’s emotional state, and can be subdivided into the distinct dimensions of positive and negative affect (Watson et al., 1988). Positive affect “reflects the extent to which a person feels enthusiastic, active, and alert”, whereas negative affect “subsumes a variety of aversive mood states, including anger, contempt, disgust, guild, fear, and nervousness” (Watson et al., 1988, p. 1063). Self-esteem describes a person’s self-assessment of their worth (Rosenberg et al., 1995); it can be divided into global self-esteem, representing an overall judgment of the self, and domain-specific self-esteem, which involves a subjective appraisal of one’s value in a specific domain (Leary & Baumeister, 2000). Our focus centers on performance self-esteem, which depends on meeting personal standards in terms of competence and worthiness (Brown & Zeigler-Hill, 2018). This form appears particularly relevant within the context of work, aligning with the specificity-matching principle which states that the level of specificity of predictors and outcomes (e.g., performance self-esteem and work performance) should correspond (Swann et al., 2007). Recognizing that self-esteem may fluctuate daily depending on daily experiences (Nezlek & Plesko, 2001), this study explores state self-esteem.

Our focus centers on measuring affect and self-esteem at bedtime to capture the dyadic effects of work-related conversations following the workday. Previous research has demonstrated that affect and self-esteem assessed at bedtime tend to persist until the subsequent workday (Neff et al., 2012; Sonnentag & Binnewies, 2013). Furthermore, Tremmel et al. (2018) showed that the effects of work-related conversations on employees’ affect endured until the following morning. Daily affect and self-esteem have been shown to be associated with engagement and work performance (e.g., Rothbard & Wilk, 2011; Xanthopoulou et al., 2009).

Employees’ Affect and Self-Esteem as a Consequence of Sharing Work Events

Experiencing affective events has been linked to employees’ emotional states and self-esteem (Nezlek & Plesko, 2001; Ohly & Schmitt, 2015). Subsequently, when employees share work events with their partners, they tend to relive and re-experience these affective events, thereby keeping them cognitively active, more salient, and readily accessible in memory (Rimé, 2009). This reliving of events through social sharing is expected to be associated with employees’ affect and self-esteem. Consistent with prior research that indicates symmetric relationships (i.e., negative factors predict negative affect, positive factors predict positive affect) are more consistently pronounced for well-being outcomes (for an overview, see Sonnentag, 2015), we anticipate that sharing positive work events relates to increased positive affect and sharing negative work events corresponds to increased negative affect.

Capitalization theory (Langston, 1994) posits that people can derive additional benefits from positive events by sharing them with someone else. Capitalization involves the interpersonal interaction of recounting good news, offering advantages that extend “over and above the original value of the positive event” (Peters et al., 2018; p. 2). Thus, social sharing of positive events serves to sustain, prolong, or amplify positive thoughts and feelings (Rimé, 2007). The interpersonal model of capitalization (InterCAP; Peters et al., 2018) suggests that this process leads to favorable outcomes in two primary ways: through the act of sharing with responders and via the perception of enthusiastic and supportive responses. Accordingly, on days when employees share positive work events with their partner after work, they re-experience these positive events and perceive their partners’ responsiveness, thereby enhancing their positive affect at bedtime (Gable et al., 2004). Empirical evidence supports the notion that discussing positive work events influences life satisfaction, affect, and work-family balance (Hicks & Diamond, 2008; Ilies et al., 2015, 2017; Tremmel et al., 2018).

In the rumination literature, it is well-known that after experiencing negative events, negative thought processes frequently occur (Cropley et al., 2006). Subsequently, persistent negative thoughts keep the negative event cognitively activated, leading to heightened negative affect and reduced self-esteem (Broderick, 1998; Sonnentag & Lischetzke, 2018; Wang et al., 2013). Similarly to rumination, through social sharing, individuals tend to revisit negative events, reactivating and rehearsing the associated negative thoughts and feelings (Rimé, 2009). Verduyn et al. (2011), for instance, found that discussing emotion-eliciting events keeps the corresponding emotions active in the mind. Additionally, sharing negative work-related events may foster co-rumination—a process involving excessive discussion of problems and dwelling on negative feelings—prolonging the negative effects (Rose, 2021).

Contrary to the belief that talking about negative events assists in unburdening oneself and finding relief (Zech & Rimé, 2005), research on the consequences of social sharing indicates that sharing negative work experiences is linked to increased negative affect, exhaustion, burnout, depression, frustration, and work-to-family conflict (Baranik et al., 2017; Beehr et al., 2000; Brown et al., 2005; Haggard et al., 2011; Zellars & Perrewé, 2001). Regarding evidence from daily diary studies, Tremmel et al. (2018) found that negative work-related conversations during off-job time, even if not necessarily with a partner, were related to negative affect, whereas Hicks and Diamond (2008) did not find that telling the partner about the most negative event of the day—whether work-related or not—was associated with increased negative affect.

Depending on the experience of positive and negative events, self-esteem can fluctuate (Nezlek & Gable, 2001; Nezlek & Plesko, 2001; Orth & Luciano, 2015). Work-related self-esteem is shaped by the work environment, which conveys implicit or explicit cues about employees’ competence and value, and provides opportunities for success (Bowling et al., 2010; Pierce & Gardner, 2004). In particular, work experiences that foster an employee’s competence, such as successfully completing a project, contribute to a more positive self-image, while experiencing failure can lead to decreased self-esteem (Brockner, 1989; Korman, 1976). When individuals share success or failure with their partner, they tend to relive the affective work event and the associated emotions become more salient in their minds (Rimé, 2009), resulting in increased or decreased work-related self-esteem, respectively. Accordingly, on days when employees share positive work events, their self-esteem is likely to be boosted during the evening, while when they share negative work events, their self-esteem might suffer. Levine et al. (1994) provides empirical evidence to support this hypothesis, finding that a person’s global self-esteem was significantly lower after they had described a negative achievement experience compared to describing a positive one. Thus, we propose the following:

-

H1: Employees’ daily sharing of positive work events is positively related to a) employees’ positive affect and b) employees’ self-esteem at bedtime.

-

H2: Employees’ daily sharing of negative work events is a) positively related to employees’ negative affect and b) negatively related to employees’ self-esteem at bedtime.

Partners’ Affect and Self-Esteem as a Consequence of Sharing Work Events

We propose that social sharing initiated by an employee in a relationship will not only affect their own but also their partner’s day-specific affect and self-esteem. According to social sharing theory (Rimé, 2009), being informed about an emotional event serves as an emotion-eliciting situation itself, and listening to such events has been associated with both positive and negative emotions in the listener (Christophe & Rimé, 1997). Two theoretical models explain why social sharing, as an emotion-eliciting situation, is relevant to the affect and self-esteem of partners.

The extended version of the self-evaluation maintenance model (Beach & Tesser, 1995) proposes that within intimate relationships, the partner becomes integrated into one’s own identity. As relationship partners empathize with each other (Pinkus et al., 2008), the success or failure of a partner is perceived as personally impactful (McFarland et al., 2001). Consequently, on days when employees share positive or negative work events, the partners tend to have similar affective experiences and self-evaluation, as they empathize and place themselves in the employee’s position. McFarland et al. (2001) showed that study participants experienced positive affect following their partners’ success and tended to exhibit enhanced self-evaluations, given they are part of a person’s self-esteem (Rosenberg et al., 1995).

Moreover, the self-expansion model (Aron et al., 2013) similarly describes self-evaluations within intimate relationships. It posits that in such relationships, the partner’s resources and perspectives become integrated into one’s own sense of self. When employees share their affective work events upon reuniting with their partners in the evening, the partners experience the positivity or negativity to some extent as their own feelings, thereby potentially elevating their positive affect and self-esteem or conversely reducing their negative affect and self-esteem on that particular day. For instance, being informed about one’s partner’s most positive event was associated with positive affect on a daily level (Hicks & Diamond, 2008), although being told about one’s partner’s most negative event did not relate to negative affect. Additionally, Neff et al. (2013) observed a positive relationship between employees’ job-related self-efficacy and their partners’ self-efficacy, mediated by vicarious experience—specifically, the utilization of others as models for one’s self-evaluation (Bandura, 1997). We propose the following hypotheses:

-

H3: Employees’ daily sharing of positive work events is positively related to a) partners’ positive affect and b) partners’ self-esteem at bedtime.

-

H4: Employees’ daily sharing of negative work events is a) positively related to partners’ negative affect and b) negatively related to partners’ self-esteem at bedtime.

Control Variables

As previously mentioned, the initiators or precursors of social sharing are affective experiences (Rimé, 2009). It is established that experiencing affective work events is related to affect and self-esteem (Eatough et al., 2016; Tremmel et al., 2018). According to social sharing theory, sharing has effects that surpass the mere experience itself, offering an opportunity to re-engage with positive or negative work events (Rimé, 2009). Therefore, in our analyses, we control for experiencing positive and negative work events to ensure that the hypothesized effects were uniquely attributed to sharing, rather than to the personal experience of one’s own work events.

Method

Sample and Procedure

This study formed part of a broader data collection effort among dual-earner couples, which involved three daily web-based surveys in the morning, after work, and at bedtime over one work week in addition to an intake survey before the daily diary period.Footnote 1 For this study, only data from the after-work and bedtime surveys were used.

To recruit participants, our study titled “We Work, We Love, We Talk – Study on Work-related Communication in Partnerships” was advertised across various social media community groups (e.g., groups for dual-earner couples, (trainee) teachers, research associates, working mothers, survey participants, and university alumni). Additionally, information leaflets were distributed in local venues (e.g., in cafés, shops, dancing schools, and childcare facilities) and mailboxes of private households. Eligible participants were required to be engaged in a heterosexual relationship, with both partners working at least three days per week. We decided to include heterosexual romantic couples only to control for possible effects of the type of dyad. All participants received information about the study before registration and consented to be involved in the study. Participation was voluntary. Anonymity was ensured throughout the data collection and management processes. All data were collected via online surveys.

Couples who completed the survey for at least three days received a 10 € gift card for an online store and were offered the opportunity to receive a summary of their results. Initially, a total of 231 individuals completed the intake survey. Subsequently, their partners were invited to complete the same intake survey. We matched data from 182 individuals, yielding 91 couples who agreed to participate in the study. Data of the remaining 49 individuals could not be matched because their partners did not complete the intake survey. After excluding 18 couples who did not respond to a single questionnaire during the workweek, our final sample comprised 73 couples (146 individuals). To control for selection effects, we tested whether the final sample of couples differed from those individuals who did not complete the daily survey. We found no significant differences between the groups regarding demographic characteristics (e.g., children, age, years of work experience, relationship length, number of working hours) and measures from the general survey (e.g., trait affect, personality, trait self-esteem).

Throughout the study period, participants completed 665 (out of 730 possible) daily after-work surveys and 629 (out of 730 possible) daily bedtime surveys. We matched the individual daily surveys to a pairwise daily data file consisting of 298 (out of 365 possible) days. On 140 days, we had data from one partner of the couple only. Most couples (86.3%) resided together, and 15.1% had at least one child living in their household. On average, the couples had been in a relationship for 7.21 years (SD = 7.63). The mean age of men was 34.67 years (SD = 9.25) and they worked approximately 41.32 (SD = 9.19) hours per week. The female partners were 32.42 years old (SD = 9.39) on average and worked an average of 35.54 (SD = 12.27) hours per week. The majority of participants (72.6%) held academic degrees (e.g., bachelor’s or master’s degree, PhD). The most frequently mentioned occupations were research assistant, engineer, teacher, and psychologist.

Measures

In the after-work questionnaire, participants reported their experience of work events during their workday. Sharing work events, state work-related self-esteem, and affect were assessed in the evening before going to bed. For Cronbach’s alpha, we report the range of internal consistencies across all measurement days separately for women and men.

Experiencing Work Events

We used the work event checklist developed by Ohly and Schmitt (2015). Participants were asked to rate, on a five-point Likert scale, the extent to which various positive and negative work events applied to their workday (1 = Not applicable to 5 = Fully applicable). One example of the five positive work events items was: “To what extent did you solve any work-related problem, complete a work task, or did you succeed in a certain work-related task today?”. One example of the six negative work events items was: “To what extent did you experience time pressure, excessive demands, or did you recognize mistakes which resulted in difficulties to fulfil your work tasks today?”.

Sharing Work Events

To assess whether employees shared work events with their partners, we adapted the 11 work events of the checklist by Ohly and Schmitt (2015). Participants responded on a five-point Likert scale to what extent the statements applied to the respective evening. Sample items include, “I told my partner today that I received praise, positive feedback or thanks from others at work (e.g., supervisor, colleagues or customers)”, and, “I told my partner today that I experienced conflicts or communication problems with colleagues” (1 = Not applicable to 5 = Fully applicable). In addition, participants had the option to indicate that “The event did not occur”. If participants chose this option, this item was not included when calculating the mean value.

State Work-Related Self-Esteem at Bedtime

Consistent with our focus on work-related experiences and guided by the specificity-matching principle, which advocates for the predictors and outcomes’ level of specificity to be matched (Swann et al., 2007), we used the adapted and shortened form of Heatherton and Polivy’s (1991) performance subscale (as seen in Neff et al., 2012). Participants responded on a five-point Likert scale with their level of agreement with the statements. An example item is: “I feel that I have less professional ability than others” (1 = I do not agree at all to 5 = I fully agree). Cronbach’s alpha ranged between 0.74 and 0.83 for women and between 0.75 and 0.85 for men.

Positive and Negative Affect at Bedtime

We used 10 items of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson et al., 1988). Participants rated their current affective state on a five-point Likert scale “now, before going to bed” (1 = not at all to 5 = very much). Positive affect was measured with four items (e.g., “interested”, “inspired”). Negative affect was measured with the six-item short version of the negative affect scale (cf. Sonnentag & Binnewies, 2013; e.g., “distressed”, “nervous”). Cronbach’s alpha for negative affect ranged between 0.73 and 0.88 for women and between 0.77 and 0.87 for men. Cronbach’s alpha for positive affect ranged between 0.75 and 0.81 for women and 0.68 and 0.81 for men.

Data Analysis

Within diary data from members of a couple, two sources of nonindependence are present. First, intimate partners tend to share experiences and exhibit greater similarity to each other than they are to individuals outside their relationship (Kenny et al., 2006). Second, the daily surveys completed by each individual are nonindependent. To address this, we accounted for the dependent structure of our data by estimating a multilevel model for dyadic diary data, in which daily observations of both dyad members are nested within the dyad (Laurenceau & Bolger, 2012). This model includes attributes of the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model and frames bidirectional influence in terms of individual outcomes and both actor effects (where an employee’s dependent variable is regressed on their own independent variable), and partner effects (where an employee’s dependent variable is regressed on their partner’s independent variable) are estimated simultaneously.

We tested our hypotheses using Mplus Version 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). In diary data analysis, two types of effects can be distinguished: within-person associations fluctuate around an average level from day to day, and between-person effects vary across individuals. Given our primary focus on the within-person level, we modeled the assumed actor and partner effects only at the within-couple level. We centered predictor variables around the respective person-mean to reflect daily within-person relations. On the between-couple level, we only modeled the covariance between both partners’ outcomes.

Results

Table 1 displays the mean scores and standard deviations at the within- and between-person levels as well as intercorrelations between the study variables. We also examined whether positive affect, negative affect, and self-esteem differed between couples by partitioning the total variance into within- and between-couple variance. Intraclass correlations (ICCs) are displayed in Table 1.

Hypothesis Testing

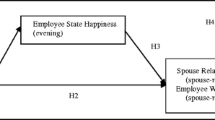

We estimated three separate models, each corresponding to an outcome variable (i.e., positive affect, negative affect, self-esteem). The results of all models are displayed in Table 2 and Fig. 1. The outcomes on a given day for members within a couple were modeled as a function of their individual fluctuations in sharing positive and negative events, as well as their partners’ respective fluctuations in sharing positive and negative events. In addition, we modeled experiencing positive and negative work events of both partners as control variables. For model parsimony, we constrained actor and partner effects to be equal across genders. Constraining these effects did not significantly worsen model fit.

Study model and results. a Positive affect as outcome. b Negative affect as outcome. c Self-esteem as outcome. Note. Solid lines indicate significant relationships. Dotted lines indicate non-significant relationships. For clarity, we only included employee predictor variables in the figures, although the full model included partner and employee predictor variables and partner and employee outcome variables with the corresponding actor and partner effects

We hypothesized that employees’ sharing of positive work events would be positively associated with their own (H1a) and their partners’ (H3a) positive affect. Model 1, where positive affect was the outcome variable, demonstrated a good fit to the data (χ2(8) = 10.407, p = 0.238, CFI = 0.990, RMSEA = 0.032). Employees’ sharing of positive work events was positively associated with their own positive affect, but not with their partners’ positive affect. Therefore, H1a was supported but H3a was not. Additionally, employees’ sharing of negative work events was not found to be related to their own or their partners’ positive affect. Neither experiencing positive nor negative events was significantly associated with employees’ or partners’ positive affect.

In Model 2, with negative affect as the outcome variable, we tested whether employees’ sharing of negative work events is positively related to employees’ (H2a) and partners’ (H4a) negative affect. The model exhibited a good fit with the data (χ2(8) = 11.990, p = 0.152, CFI = 0.984, RMSEA = 0.041). Employees’ sharing of negative work events was neither significantly associated with employees’ nor with their partners’ negative affect. Thus, Hypotheses 2a and 4a were not supported. Neither sharing nor experiencing positive work events was associated with employees’ or their partners’ negative affect. Further, experiencing negative work events was positively associated with employees’ own negative affect, but not with their partners’ negative affect.

In Model 3, where self-esteem was the outcome variable, we tested hypotheses concerning the relationship between employees’ sharing of positive work events and their own (H1b) and their partners’ (H3b) self-esteem and between employees’ sharing of negative work events and their own (H2b) and their partners’ (H4b) self-esteem. The model was a good fit to the data (χ2(8) = 15.356, p = 0.053, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.056). However, employees’ sharing of both positive and negative work events was found to be unrelated to employees’ self-esteem; thus, H1b and H2b were not supported. Also, contrary to our assumption, employees’ sharing of positive work events was negatively, and not positively, related to partners’ self-esteem. Therefore, H3b was not supported. Conversely, in support of H4b, employees’ sharing of negative work events was negatively related to their partners’ self-esteem at bedtime. Experiencing positive work events was negatively related to employees’ self-esteem but unrelated to partners’ self-esteem. Experiencing negative work events was unrelated to both employees’ and partners’ self-esteem.

Discussion

This diary study involving dual-earner couples aimed to examine whether sharing positive and negative work events influences the affect and self-esteem of both partners, independently of the direct effects of experiencing these work events. Our findings indicated that sharing positive work events was positively related to employees’ positive affect, while it did not show any significant association with their self-esteem. The sharing of negative work events was unrelated to employees’ negative affect and self-esteem. Unexpectedly, both sharing positive and negative work events were negatively associated with partners’ self-esteem, but unrelated to partners’ positive and negative affect.

Theoretical Contributions

Our findings suggest that sharing work events has differential implications for the affect and self-esteem of dual-earners. Consistent with capitalization theory (Peters et al., 2018) and prior research (Gable et al., 2004; Hicks & Diamond, 2008; Tremmel et al., 2018), sharing positive work events was associated with an increase in employees’ positive affect. On days when employees told their partners about their successes and positive experiences at work, doing so appeared beneficial by reactivating these positive experiences. By controlling for experiencing work events in the analyses, our results reveal that sharing work events with a partner influenced well-being beyond the direct experience of these events. Thus, capitalizing on positive work events is evidently an effective strategy in nurturing individual well-being (Ilies et al., 2023).

In contrast to our hypothesis, sharing positive work events was unrelated to employees’ own self-esteem. However, experiencing these same positive work events was positively related to their self-esteem. It is plausible that reliving a positive work experience through social sharing might not be sufficiently powerful to increase one’s self-evaluation beyond the event itself. The interpersonal model of capitalization (InterCAP; Peters et al., 2018) suggests that capitalization leads to beneficial outcomes via both the act of sharing and the perception of enthusiastic and supportive responses. Therefore, partners’ reactions to employees’ capitalization on positive events could be relevant (Gable et al., 2004). Perhaps only when partners react enthusiastically to employees sharing good news, employees’ self-esteem may be boosted, while negative or unsupportive reactions might undermine the self-esteem-enhancing effects (B. J. Peters et al., 2018). The diverging results on the effects of social sharing on positive affect and self-esteem suggest that while the act of sharing might suffice in enhancing affect, a partner’s reactions might be particularly important when it comes to improving one’s self-esteem. Hence, our study underscores the importance of considering different outcomes and boundary conditions to gain a comprehensive understanding of the consequences of social sharing.

Contrary to our hypotheses and previous research findings (Tremmel et al., 2018), sharing negative work events was unrelated to negative affect and self-esteem. However, we found that the experience of negative work events was related to negative affect at bedtime, indicating that in fact, negative work events spill over into employees’ non-work time (i.e., Bakker & Demerouti, 2013). Again, the reaction of the partner (i.e., how they support and encourage when being told about negative experiences) may be pivotal, as suggested by Rimé (2009), who proposed that there are two different modes of reaction (i.e., affective and cognitive sharing mode) which may have differential effects on the sharers’ affective state. According to social sharing theory (Rimé, 2009), the affective sharing mode—characterized by conversation partner responses such as empathy and consolation—might perpetuate or intensify negative affect if conversations dwell on the negative experience without seeking alternative perspectives (Tremmel & Sonnentag, 2018). In contrast, the cognitive sharing mode, involving attempts to reframe a negative experience or to adjust expectations, could aid individuals in overcoming a negative experience and thus mitigate its impact. In our study, some partners may have tried to help their partners see their negative work experiences in a different light or to contextualize their failures. Thus, although discussing negative events may have reactivated feelings associated with the negative experience, the partners’ supportive reactions may have facilitated better coping mechanisms. As a result, the negative work-related conversations might not have directly led to increased negative affect or reduced self-esteem (cf. Tremmel et al., 2018). Future research should not only assess the valence of work-related conversations but also the partners’ reactions to reconcile the inconsistencies in current and previous findings.

Altogether, our study provides support for the assumption that sharing positive work-related events with one’s partner increases positive affect, but not self-esteem. However, it did not confirm that sharing negative work events harms employees’ affect and self-esteem. Interestingly, bivariate day-level correlations revealed a positive association between sharing positive and negative events. This suggests that on days when employees share positive events with their partners, it is likely that they also share negative events. By simultaneously considering the effects of both positive and negative work-related sharing, our study contributes to a comprehensive understanding of the effects of work-related social sharing.

Furthermore, our study extends previous research on the individual consequences of social sharing by adopting a dyadic perspective and examining in what way sharing positive and negative work events has implications for employees’ partners, thereby addressing an important gap in the literature (Peters et al., 2018). Based on the extended self-evaluation maintenance model and the self-expansion model (Aron et al., 2013; Beach & Tesser, 1995), we hypothesized that in intimate relationships, partners assimilate each other’s resources and perspectives into their self-concepts, such that successes or setbacks that are shared will similarly influence their own affect and self-esteem. However, contrary to our expectations, we found that employees’ social sharing was associated only with their partners’ self-esteem, and not with their affect.

There are several possible explanations for this pattern of findings. First, couples might have not only discussed work events but also shared positive or negative events unrelated to their work (e.g., a call from a good friend, being stuck in a traffic jam). Hearing about these positive or negative non-work events might have attenuated or concealed the effects of work-related conversations on partners’ affect, but not on their self-esteem. In a previous study, Hicks and Diamond (2008) observed an association between being informed about the most positive experience of the day and increased positive affect. However, as their focus was not specifically on work events, it is conceivable that capitalizing on positive family events (cf. Du et al., 2020) or leisure activities may be more relevant to one’s affect during leisure time than a specific work-related event.

Secondly, the effects of hearing about partners’ positive and negative work events might be dependent on moderating factors. Crossover research suggests that the transfer of one partner’s experiences to another partner is dependent on perspective-taking and empathy (Bakker et al., 2011; Neff et al., 2012). Individuals who can easily empathize or place themselves in their partner’s place might be more prone to share in their partner’s achievements and setbacks, thus being more influenced by these events. Similarly, couples who share the same occupation or work in the same organization (work-linkage; Ferguson et al., 2016), might possess a deeper understanding of their partner’s work conditions and environment, potentially leading them to experience similar emotions to their partner. Consequently, future research should investigate not only couples’ non-work-related conversations but also their aptitude for perspective-taking or work linkage as potential boundary conditions. These aspects could be integrated into the self-expansion and self-evaluation maintenance model to resolve inconsistent findings.

Unexpectedly, we found that employees’ sharing of both positive and negative work events was detrimental to partners’ self-esteem. Regarding negative work events, this finding is consistent with social sharing theory (Rimé, 2009) and supports our hypothesis. Thus, partners in dual-earner relationships appear to integrate their significant other’s negative work experiences into their own self-evaluation, leading to a decline in self-esteem. However, contrary to the hypothesized positive association between employees’ sharing of positive work events and partners’ self-esteem, we found a negative one. This finding is surprising as we expected that partners could derive benefit from each other’s successes, in a “basking in reflected glory” type of effect (Cialdini et al., 1976), resulting in increased self-evaluation. Similarly, the results of Neff et al. (2012) suggested that the reinforced positive effect of positive work events (resulting from social sharing) would transmit to partners’ self-esteem.

One possible explanation is that partners react differently to positive versus negative sharing. While hearing about their partner’s negative or distressing experiences may provoke compassion and due to the shared identity, diminish self-esteem, being told about their partner’s positive work events might trigger comparison processes and a feeling of inferiority (i.e., decreased self-esteem). It is common for partners in intimate relationships to regularly compare themselves to their partners (Pinkus et al., 2008). Hearing about their partners’ positive and negative work experiences might trigger this comparison process. Individuals might feel outperformed when they are being told about their partner’s successes at work. Due to their communal orientation, partners react more positively to upward (i.e., being outperformed by the partner) than to downward comparisons (Pinkus et al., 2008; Scinta & Gable, 2005). However, under specific circumstances, partners may not react positively to upward comparisons when they hear about their employees’ positive work events, particularly if they feel competitive with their partner or believe that they are being outperformed in an area that is important to them. Under these conditions, hearing about their partners’ positive experiences might instead lead to envy and counteract the typically positive effects of capitalization (cf. Watkins, 2021). Our sample consisted mainly of young professionals highly engaged in their work. Thus, it is likely that work is important to them, which might foster feelings of competition between partners, potentially negating the expected positive effects of learning about partners’ positive work events on employees’ self-esteem.

Our study emphasizes the importance of considering the dyadic effects of social sharing. Solely looking at the individual level could have led us to conclude that sharing positive work events is beneficial for employees, as it is associated with increased positive affect. However, adopting a dyadic perspective reveals a more nuanced scenario, indicating that the individual view does not present the full picture, as employees’ sharing might harm their partners’ self-esteem. Therefore, when formulating recommendations, it is necessary to consider both individual and dyadic effects to optimize both partners’ well-being simultaneously.

Limitations and Implications for Future Research

The limitations of the present study include that no clear causal inferences can be made in diary studies (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013). Our dyadic design allowed us to separate the effects of one’s own predictors from the partner’s predictors on their affect and self-esteem. However, participants were requested to report the social sharing of work events, their affect, and their self-esteem at the same time point (before bedtime). This concurrent reporting might have introduced common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Therefore, we cannot be certain that the reporting of social sharing accurately reflected the actual sharing, as it might have been influenced by their affect at that moment.

Further, in our analyses, we did not find the hypothesized negative association between sharing negative work events and negative affect. We speculated that this might be due to fluctuations of negative affect during the conversation, leading to a non-significant association. It is possible that initially, sharing negative work events increases negative affect by recalling the negative events. However, when the employee was able to vent their negative feelings, they might have felt a sense of relief, resulting in decreased negative affect. Future diary studies could explore the temporal sequences and fluctuations in negative affect further by adding several measurement points throughout the evening.

In our study, we focused solely on the effects of social sharing between partners within a given day. However, as the InterCAP model (Peters et al., 2018) suggests, capitalization is an iterative process; capitalization with responsive partners’ reactions leads to more capitalization from both partners. Therefore, future research should not solely examine the immediate consequences of social sharing, but should also consider short- and longer-term consequences.

Future research should also investigate potential strategies or situations in which employees can benefit from the social sharing of positive work events (in terms of increased positive affect), without inadvertently affecting their partners’ self-esteem negatively. As research has indicated that a highly communal orientation is associated with feeling connected to the other person, whether partners benefit from sharing successes or feel outperformed might be determined by their communal orientation (Locke & Nekich, 2000). Future research is warranted to elucidate the role of partner reactions in the association between social sharing and the well-being of both employees and partners. Such research could consider distinguishing between affective and cognitive sharing modes (Tremmel & Sonnentag, 2018).

We used a convenience sample of heterosexual couples which may raise concerns regarding the generalizability of findings to working couples from different backgrounds. Our sample was relatively well-educated with both partners working (close to) full-time hours, suggesting that our findings might be most applicable to academics with significant work involvement. Moreover, our sample was relatively young and only 15% of couples had children living with them. Previous research has revealed that the presence of children in a household might modify the effects of partners’ experiences and behaviors (Hahn & Dormann, 2013; Hahn et al., 2014). Therefore, it is important that future studies use more systematic sampling methods to examine if our findings replicate in culturally and demographically diverse samples (e.g., same‐sex couples, couples with children). We call for more research encompassing other relationship dynamics (e.g., same-sex relationships, platonic cohabitation relationships), as the level of relationship closeness may influence the effects of social sharing (Beach & Tesser, 1995).

Practical Implications

Our results show that while sharing positive work events is beneficial to employees’ affect, it may detrimentally impact partners’ self-esteem. Thus, employees should carefully consider the advantages and disadvantages of sharing positive work events. To prevent harm to their partner, employees could use intrapersonal strategies (e.g., reflection on positive work experiences) instead of interpersonal strategies (e.g., discussing work events with the partner) to amplify the positive effects of work experiences (cf. Ilies et al., 2023). For instance, positive work reflection has been found to be beneficial to employees’ well-being and engagement (Walter & Haun, 2020). Furthermore, our findings suggest that sharing negative work events is detrimental to partners’ self-esteem. Nevertheless, partner support is a powerful resource for enhanced well-being and relationship satisfaction (Haun et al., 2017; Park & Fritz, 2015), and sharing emotions has been found to increase social bonds (K. Peters & Kashima, 2007); we do not advocate against employees sharing bad news with their partners. Instead, it might be helpful to focus on problem-solving and reframing the issue in a more positive light (Tremmel & Sonnentag, 2018; Weigelt & Syrek, 2017). Furthermore, employees could share work events with alternative conversation partners. Co-workers, in particular, might be more suitable to discuss work issues with, given their familiarity with the work environment and potential assistance in solving specific work problems (Norling & Chopik, 2020).

Conclusion

The findings from this daily diary study show that sharing work events with an intimate partner has implications for employees’ positive affect and their partners’ work-related self-esteem. Exploring these variables from a dyadic perspective revealed that being informed about an affective work event—regardless of whether it was positive or negative—was detrimental to one’s self-esteem. Thus, our research emphasizes the importance of taking a dyadic perspective to gain a comprehensive understanding of the consequences of dual-earner couples’ day-to-day interpersonal behaviors.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Notes

This is the first publication from the data set.

References

Aron, A., Lewandowski, G. W., Mashek, D., & Aron, E. N. (2013). The self-expansion model of motivation and cognition in close relationships. In J. Simpson & L. Campbell (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Close Relationships (pp. 90–115). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195398694.013.0005

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2013). The spillover-crossover model. In J. G. Grzywacz & E. Demerouti (Eds.), Current Issues in Work and Organizational Psychology. New Frontiers in Work and Family Research (pp. 54–70). Psychology Press.

Bakker, A. B., Shimazu, A., Demerouti, E., Shimada, K., & Kawakami, N. (2011). Crossover of work engagement among Japanese couples: Perspective taking by both partners. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(1), 112–125. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021297

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control (13th ed.). Freeman.

Baranik, L. E., Wang, M., Gong, Y., & Shi, J. (2017). Customer mistreatment, employee health, and job performance. Journal of Management, 43(4), 1261–1282. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314550995

Beach, S. R. H., & Tesser, A. (1995). Self-esteem and the extended self-evaluation maintenance model. In M. H. Kernis (Ed.), Efficacy, Agency, and Self-esteem (pp. 145–170). Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-1280-0_8

Beach, S. R. H., Tesser, A., Mendolia, M., Anderson, P., Crelia, R., Whitaker, D., & Fincham, F. D. (1996). Self-evaluation maintenance in marriage: Toward a performance ecology of the marital relationship. Journal of Family Psychology, 10(4), 379–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.10.4.379

Beehr, T. A., Jex, S. M., Stacy, B. A., & Murray, M. A. (2000). Work stressors and coworker support as predictors of individual strain and job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(4), 391–405. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(200006)21:4<391::AID-JOB15>3.0.CO;2-9

Bolger, N., & Laurenceau, J.-P. (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. Methodology in the social sciences: 2013: 4. The Guilford Press.

Bowling, N. A., Eschelman, K. J., Wang, Q., Kirkendall, C., & Alarcon, G. (2010). A meta-analysis of the predictors and consequences of organization-based self-esteem. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(3), 601–626. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X454382

Brockner, J. (1989). Self-esteem at work: Research, theory, and practice. Heath.

Broderick, P. C. (1998). Early adolescent gender differences in the use of ruminative and distracting coping styles. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 18, 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431698018002003

Brown, D. J., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2018). Self-esteem. In D. L. Ferris, R. E. Johnson, & C. Sedikides (Eds.), SIOP organizational frontiers series. The self at work: Fundamental theory and research (pp. 40–71). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315626543-3

Brown, S. P., Westbrook, R. A., & Challagalla, G. (2005). Good cope, bad cope: Adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies following a critical negative work event. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 792–798. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.792

Christophe, V., & Rimé, B. (1997). Exposure to the social sharing of emotion: Emotional impact, listener responses and secondary social sharing. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199701)27:1<37::AID-EJSP806>3.0.CO;2-1

Cialdini, R. B., Borden, R. J., Thorne, A., Walker, M. R., Freeman, S., & Sloan, L. R. (1976). Basking in reflected glory: Three (football) field studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34(3), 366–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.34.3.366

Cropley, M., Dijk, D.-J., & Stanley, N. (2006). Job strain, work rumination, and sleep in school teachers. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(2), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320500513913

Culbertson, S. S., Mills, M. J., & Fullagar, C. J. (2012). Work engagement and work-family facilitation: Making homes happier through positive affective spillover. Human Relations, 65(9), 1155–1177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712440295

Du, D., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2020). Capitalization on positive family events and task performance: A perspective from the work-home resources model. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 25(5), 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000259

Eatough, E. M., Meier, L. L., Igic, I., Elfering, A., Spector, P. E., & Semmer, N. K. (2016). You want me to do what? Two daily diary studies of illegitimate tasks and employee well-being. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(1), 108–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2032

Ferguson, M., Carlson, D., Kacmar, K. M., & Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2016). The supportive spouse at work: Does being work-linked help? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039538

Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., Impett, E. A., & Asher, E. R. (2004). What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 228–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.228

Haggard, D. L., Robert, C., & Rose, A. J. (2011). Co-rumination in the workplace: Adjustment trade-offs for men and women who engage in excessive discussions of workplace problems. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9169-2

Hahn, V. C., & Dormann, C. (2013). The role of partners and children for employees’ psychological detachment from work and well-being. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030650

Hahn, V. C., Binnewies, C., & Dormann, C. (2014). The role of partners and children for employees’ daily recovery. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.03.005

Haun, V. C., Haun, S., & Himmel, T. (2017). Benefits and drawbacks of partner social support in dual earner couples’ psychological detachment from work. Wirtschaftspsychologie, 19(3), 51–63.

Heatherton, T. F., & Polivy, J. (1991). Development and validation of a scale for measuring state self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(6), 895–910. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.6.895

Hicks, A. M., & Diamond, L. M. (2008). How was your day? Couples’ affect when telling and hearing daily events. Personal Relationships, 15(2), 205–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2008.00194.x

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Ilies, R., Keeney, J., & Goh, Z. W. (2015). Capitalising on positive work events by sharing them at home. Applied Psychology, 64(3), 578–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12022

Ilies, R., Liu, X.-Y., Liu, Y., & Zheng, X. (2017). Why do employees have better family lives when they are highly engaged at work? The Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(6), 956–970. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000211

Ilies, R., Bono, J. E., & Bakker, A. B. (2023). Crafting well-being: Employees can enhance their own well-being by savoring, reflecting upon, and capitalizing on positive work experiences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-110721-045931. Advance online publication.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. The Guilford Press.

Korman, M. (Ed.). (1976). Levels and patterns of professional training in psychology. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10047-000

Kuster, F., Orth, U., & Meier, L. L. (2013). High self-esteem prospectively predicts better work conditions and outcomes. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(6), 668–675. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550613479806

Langston, C. A. (1994). Capitalizing on and coping with daily-life events: Expressive responses to positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1112–1125. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1112

Laurenceau, J.-P., & Bolger, N. (2012). Analyzing intensive longitudinal data from dyads. In M. R. Mehl, T. S. Conner, & M. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds.), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (pp. 407–422). Guilford Press.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion (Vol. 46). https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819

Leary, M. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 32, pp. 1–62). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(00)80003-9

Levine, S. R., Wyer, R. S., Jr., & Schwarz, N. (1994). Are you what you feel? The affective and cognitive determinants of self-judgments. European Journal of Social Psychology, 24(1), 63–77.

Locke, K. D., & Nekich, J. C. (2000). Agency and communion in naturalistic social comparison. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(7), 864–874. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167200269011

McFarland, C., Buehler, R., & MacKay, L. (2001). Affective responses to social comparisons with extremely close others. Social Cognition, 19(5), 547–586. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.19.5.547.19911

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus User's Guide. Seventh Edition. Muthén & Muthén.

Neff, A., Sonnentag, S., Niessen, C., & Unger, D. (2012). What’s mine is yours: The crossover of day-specific self-esteem. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(3), 385–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.10.002

Neff, A., Niessen, C., Sonnentag, S., & Unger, D. (2013). Expanding crossover research: The crossover of job-related self-efficacy within couples. Human Relations, 66(6), 803–827. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712465095

Nezlek, J. B., & Gable, S. L. (2001). Depression as a moderator of relationships between positive daily events and day-to-day psychological adjustment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(12), 1692–1704. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672012712012

Nezlek, J. B., & Plesko, R. M. (2001). Day-to-day relationships among self-concept clarity, self-esteem, daily events, and mood. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(2), 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201272006

Norling, L. R., & Chopik, W. J. (2020). The association between coworker support and work-family interference: A test of work environment and burnout as mediators. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 819. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00819

Ohly, S., & Schmitt, A. (2015). What makes us enthusiastic, angry, feeling at rest or worried? Development and validation of an affective work events taxonomy using concept mapping methodology. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(1), 15–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9328-3

Orth, U., & Luciano, E. C. (2015). Self-esteem, narcissism, and stressful life events: Testing for selection and socialization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(4), 707–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000049

Park, Y., & Fritz, C. (2015). Spousal recovery support, recovery experiences, and life satisfaction crossover among dual-earner couples. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 557–566. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037894

Peters, K., & Kashima, Y. (2007). From social talk to social action: Shaping the social triad with emotion sharing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(5), 780–797. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.780

Peters, B. J., Reis, H. T., & Gable, S. L. (2018). Making the good even better: A review and theoretical model of interpersonal capitalization. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 12(7), e12407. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12407

Pierce, J. L., & Gardner, D. G. (2004). Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: A review of the organization-based self-esteem literature. Journal of Management, 30(5), 591–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2003.10.001

Pinkus, R. T., Lockwood, P., Schimmack, U., & Fournier, M. A. (2008). For better and for worse: Everyday social comparisons between romantic partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1180–1201. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.5.1180

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Rimé, B. (2007). Interpersonal emotion regulation. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 466–485). Guilford.

Rimé, B. (2009). Emotion elicits the social sharing of emotion: Theory and empirical review. Emotion Review, 1(1), 60–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073908097189

Rose, A. J. (2021). The costs and benefits of co-rumination. Child Development Perspectives, 15(3), 176–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12419

Rosenberg, M., Schooler, C., Schoenbach, C., & Rosenberg, F. (1995). Global self-esteem and specific self-esteem: Different concepts, different outcomes. American Sociological Review, 60(1), 141. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096350

Rothbard, N. P., & Wilk, S. L. (2011). Waking up on the right or wrong side of the bed: Start-of-workday mood, work events, employee affect, and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 54(5), 959–980. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.0056

Scinta, A., & Gable, S. L. (2005). Performance comparisons and attachment: An investigation of competitive responses in close relationships. Personal Relationships, 12(3), 357–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2005.00120.x

Sonnentag, S. (2015). Dynamics of well-being. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2(1), 261–293. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111347

Sonnentag, S., & Binnewies, C. (2013). Daily affect spillover from work to home: Detachment from work and sleep as moderators. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(2), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.03.008

Sonnentag, S., & Lischetzke, T. (2018). Illegitimate tasks reach into afterwork hours: A multilevel study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(2), 248–261. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000077

Sowislo, J. F., & Orth, U. (2013). Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 213–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028931

Swann, W. B., Chang-Schneider, C., & Larsen McClarty, K. (2007). Do people’s self-views matter? Self-concept and self-esteem in everyday life. The American Psychologist, 62(2), 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.84

Tremmel, S., & Sonnentag, S. (2018). A sorrow halved? A daily diary study on talking about experienced workplace incivility and next-morning negative affect. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(4), 568–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000100

Tremmel, S., Sonnentag, S., & Casper, A. (2018). How was work today? Interpersonal work experiences, work-related conversations during after-work hours, and daily affect. Work & Stress, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2018.1496158

Verduyn, P., Van Mechelen, I., & Tuerlinckx, F. (2011). The relation between event processing and the duration of emotional experience. Emotion, 11(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021239

Walter, J., & Haun, V. C. (2020). Positive and negative work reflection, engagement and exhaustion in dual-earner couples: Exploring living with children and work-linkage as moderators. German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift Für Personalforschung, 35(2), 249–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002220964930

Wang, M., Liu, S., Liao, H., Gong, Y., Kammeyer-Mueller, J., & Shi, J. (2013). Can’t get it out of my mind: Employee rumination after customer mistreatment and negative mood in the next morning. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(6), 989–1004. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033656

Watkins, T. (2021). Workplace interpersonal capitalization: Employee reactions to coworker positive event disclosures. Academy of Management Journal, 64(2), 537–561. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.1339

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Weigelt, O., & Syrek, C. J. (2017). Ovsiankina’s great relief: How supplemental work during the weekend may contribute to recovery in the face of unfinished tasks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(12), 1606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121606

Weiss, H., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior: An annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews (pp. 1–74). JAI Press.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Work engagement and financial returns: A diary study on the role of job and personal resources. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82(1), 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317908X285633

Zech, E., & Rimé, B. (2005). Is talking about an emotional experience helpful? Effects on Emotional recovery and perceived benefits. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 12(4), 270–287. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.460

Zellars, K. L., & Perrewé, P. L. (2001). Affective personality and the content of emotional social support: Coping in organizations. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.459

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Johanna Walter. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Johanna Walter and Verena C. Haun commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

At the authors’ institution, no formal approval of the local ethics committee was needed for this kind of survey study.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Walter, J., Haun, V.C. “Darling, You Won’t Believe What Happened at Work Today”: A Diary Study on Sharing Work Events Among Dual-Earner Couples. Occup Health Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-024-00186-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-024-00186-y