Abstract

Leadership behavior is associated with leader well-being. Yet, existing research, with the majority representing cross-sectional studies, limits our understanding of the association over time, potential mediating mechanisms, and potential reciprocal relations. Based on Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, we test between- and within-person relationships between transformational leadership and leader vigor as well as emotional exhaustion over time. In addition, we include leaders’ occupational self-efficacy, information exchange with followers, and meaning of work as mediators. 132 leaders participated in a fully cross-lagged study across three consecutive weeks. We analyzed the data with a random intercept cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM) that allows separating the within- and between-person variance in our variables. At the between-person level, transformational leadership was positively related to vigor, occupational self-efficacy, information exchange, and meaning of work. At the within-person level, there were no lagged associations of transformational leadership and well-being, but a positive lagged effect of vigor in one week on information exchange and meaning of work in the next week. Within one week, transformational leadership was related to occupational self-efficacy, meaning of work, and vigor (positive, respectively) and to emotional exhaustion (negative) within persons. In line with COR theory, we discuss transformational leadership as a resource for leaders associated with greater well-being for leaders. Our study contributes to the literature on dynamic leadership behavior and the mechanisms between leadership and leader well-being

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Transformational leadership affects multiple subordinate outcomes, such as well-being (Montano et al., 2017, 2022) or performance (Wang et al., 2011). Recently, research applied an actor-centered focus and investigated the effects of leader behavior in general, and transformational leadership in particular, on leaders’ health and well-being (Kaluza et al., 2020). At least two central aspects underline the need to focus on leaders’ well-being. First, as for every other employee, high levels of (work-related) well-being benefit leaders and their functioning in work and non-work domains. In addition, leaders are a target group that needs special attention as they are more likely than other employees to be exposed to many work-related stressors and demands (Day et al., 2004; Li et al., 2018; Skakon et al., 2011). Therefore, it is crucial to know about leader-specific stressors and resources, which could also include leadership behavior. Second, leaders’ well-being is not only important for their own functioning but also has far-reaching implications for their teams and the entire organization. For example, leaders with lower levels of well-being show more destructive leadership behaviors (Harms et al., 2017; Kaluza et al., 2020), which is also likely to manifest itself in reduced team satisfaction or productiveness (Mackey et al., 2017). Furthermore, research showed that leaders’ health can also pass over to employees (Harms et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2016; Volmer, 2012), which again highlights leaders’ crucial role in the organizational context.

However, as noted in a recent meta-analysis (Kaluza et al., 2020), most studies have been cross-sectional. Such designs do not allow investigating the associations over time or examining the processes between transformational leadership and leader well-being. This oversight is critical for two important reasons. First, transformational leadership (Kelemen et al., 2020; McClean et al., 2019) and well-being (Sonnentag, 2015) are dynamic constructs which makes it necessary to examine the relationships not only from a stable between-person but also from a fluctuating within-person perspective, testing theory accordingly at both levels (McCormick et al., 2020). Second, exploring mediating processes allows a deeper understanding of mechanisms that can help explain why transformational leadership and leader well-being are related.

The present study addresses the abovementioned limitations by investigating between- and within-person relations of transformational leadership and leaders’ vigor and emotional exhaustion. Furthermore, we examine occupational self-efficacy, information exchange with followers, and meaning of work as mediating variables. Based on Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989), we test our assumptions in a three-wave study over three consecutive weeks and model cross-lagged effects in a random intercept cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM; Hamaker et al., 2015). The RI-CLPM allows us to disentangle between-person from within-person effects. In this way, we can investigate how leader behavior relates to leader well-being and vice versa within one leader.

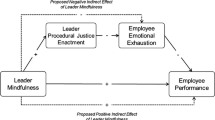

We present our conceptual model in Fig. 1. We focus on transformational leadership (Bass & Avolio, 1994), which is both a change- and relational-oriented behavior; it is a “set of behaviors designed to create and facilitate change in organizations” (DeRue et al., 2011, p. 16). Transformational leadership has been predominantly associated with resource gains for leaders (Kaluza et al., 2020), but the results are partly mixed, as outlined below. Regarding well-being, we investigate leader perceptions of vigor and emotional exhaustion, the two energy constructs of burnout and work engagement. Transformational leadership has previously been shown to be positively associated with leaders’ emotional exhaustion, both between (i.e., leaders who showed more transformational leadership than others reported higher levels of emotional exhaustion than others; Zwingmann et al., 2016) and within leaders (i.e., leaders who showed more transformational leadership in one week than in other weeks reported higher levels of emotional exhaustion than in other weeks; Lin et al., 2019). These findings contrast with a meta-analysis indicating a negative association between change-oriented leadership (e.g., transformational leadership) and impaired well-being (e.g., emotional exhaustion, Kaluza et al., 2020). In line with the meta-analytic results, a recent longitudinal study across two years with six and twelve months intervals showed a negative between-person (but no within-person) association between transformational leadership and burnout (Tóth-Király et al., 2023). Taken together, findings regarding transformational leadership and leader well-being are mixed, suggesting closer inspection.

To date, there is limited research on the association between transformational leadership and leader work engagement in general or leader vigor in particular. A recent longitudinal between-person study found a positive link from transformational leadership on work engagement eight months later and a positive link from work engagement on transformational leadership 14 months later (Geibel et al., 2022). Furthermore, although the specific constructs are not explicit, the meta-analytic results, which indicate a positive association between change-oriented leadership and different aspects of well-being (e.g., job-related well-being), might also be transferred to vigor (Kaluza et al., 2020). This scarcity of (within-person) research on vigor is unfortunate given its’ centrality for employees’ and potentially leaders’ functioning at work (Christian et al., 2011; Rivkin et al., 2018).

Emotional exhaustion, as a negative indicator of well-being (Bakker & Oerlemans, 2012), refers to a chronic state of being physically and emotionally depleted by one’s job demands (Shirom, 1989). Emotional exhaustion is an important indicator of well-being when investigating well-being through a COR lens, as it indicates a state of depleted resources. Even though emotional exhaustion has long been seen as a chronic indicator of (un)well-being (Maslach et al., 2001), research shows a substantial amount of within-person variation for the construct (Podsakoff et al., 2019). Emotional exhaustion fluctuates not only between persons but also to a large degree within persons from one week to the next. Considering emotional exhaustion as a dynamic phenomenon is important as it can help to identify factors within a person that are associated with short-term changes in emotional exhaustion.

Vigor, in turn, is incorporated as a positive indicator of work-related well-being. Vigor means feeling full of energy and mentally resilient during work (Schaufeli et al., 2002) and the experience of work as something stimulating that people want to invest time and effort in (Bakker et al., 2011). It is associated with increased motivation and performance (Christian et al., 2011) and incorporates feeling mentally resilient during work, even when confronted with difficulties and high demands (Bakker & Oerlemans, 2012), which is especially relevant when studying leaders as being in a leadership role is associated with high job demands (Li et al., 2018).

We contribute to the literature on leadership and leader well-being by investigating potential mechanisms on the leader level (i.e., leader occupational self-efficacy as a cognitive variable), the group level (i.e., information exchange of followers with the leader as an interactional variable), and the job level (i.e., leader perceptions of meaningfulness of work as an attitudinal variable). Thereby, as suggested (Kaluza et al., 2020), we can test relevant mechanisms from a resource-based perspective. In this way, we build on and extend previous studies that focused only on mediators from a single level, such as emotion regulation (Arnold et al., 2015) or needs satisfaction (Lanaj et al., 2016). Following COR theory, resources can be organized into several areas (i.e., personal, social context, work evaluations; Hobfoll, 2001), and the existence of resources in one area can be associated with resources in another area (Hobfoll, 2011). Therefore, the mediators we investigate represent a critical resource of each area, respectively, that are also highly relevant in meaningful interactions of leaders with their followers (i.e., transformational leadership). Occupational self-efficacy can be regarded as a content-specific type of self-efficacy settled in the occupational context (Volmer et al., 2022) that helps individuals to adjust to and manage occupational challenges. It constitutes an important aspect of agentic career self-management and can be considered a vital personal resource for leaders.

Leadership does not occur in a vacuum but rather in cooperation and exchange with the followers, and leaders exert significant influence on team dynamics (Lord et al., 2017). Therefore, our research includes information exchange as a group-level process variable. Information can be regarded as an important resource for individuals and organizations (Wu & Lee, 2016) that is critical for the functioning of teams and the organization (S. Wang & Noe, 2010). It is particularly relevant to our research question as it reflects the mutual exchange inherent in leadership.

Furthermore, we include the perception of having meaningful work as a resource for leaders based in their work. When employees perceive their work as meaningful, they perceive it as important, valuable, and significant for themselves or others (Steger et al., 2012). Meaningful work is formed by experiences, including actions by an individual that align with values and goals relevant to a person (Allan et al., 2014). Leadership behaviors directed towards and interactions with followers constitute an important part of leaders’ work routine. Therefore, they can also be related to leaders’ global judgment if their work helps accomplish significant or valuable goals congruent with leaders’ values (Allan et al., 2019). In the following, we outline our theoretical reasoning for the hypothesized model.

Theoretical Background

Between- and Within-Person Associations

Between-person research addresses how individuals differ from each other, whereas within-person research accounts for the fluctuating nature of most phenomena. Therefore, it investigates associations within one person at one time point compared to another time point (McCormick et al., 2020). The associations of variables at the between-person level might differ from those at the within-person level in size or directionality (McCormick et al., 2020). Yet, for other constructs, the associations across levels are the same, indicating homology between levels (e.g., Ilies et al., 2010).

Specifically, for the association of transformational leadership and well-being, it might be possible that the within-person relationships are negative (e.g., because leaders have to invest resources), but the between-person associations are positive (e.g., a net gain through the mediating resources). In contrast, for our study, we as well expect homology between levels and suggest that the processes operating at the between-person level also transfer to the within-person level. Specifically, as outlined in more detail below, we propose that the elements incorporated in transformational leader behaviors benefit leaders in general and also leaders in specific weeks in which they act more transformationally than in other weeks. Even though we assume homology of within- and between-person results, our study still adds important insights into the within- and between-person associations of transformational leadership and well-being. We can test if the relationships transfer from one week to the next and if potential reciprocal relationships exist, thereby getting an idea of the directionality of the associations. Furthermore, also the finding that the relationships look the same at the within- and the between-person level is vital because it has important theoretical and practical implications. It can enrich theory (e.g., COR theory) by helping to understand the theory’s principles (e.g., resource gain and loss) better or to get an idea of the timing of the processes (see also the discussion section).

Practically, the information that can be given to leaders on the transformational leadership – well-being link differs depending on how the relationship looks on the within vs. between-person level. Specifically, a negative within-person but positive between-person association means that leaders will likely suffer from resource loss when they show higher levels of transformational leadership than usual but gain resources in the long run when they show more transformational leadership than others. In contrast, a positive transformational leadership – well-being link on a within and between-person level indicates that it is already beneficial for leaders to show more transformational leadership than usual. In the first situation, it probably is much more difficult and less attractive for leaders to show transformational behaviors as this is initially associated with resource loss. Therefore, these two situations would have different implications for practitioners and leaders. To give evidenced advice, it is crucial to first investigate these associations both on a within- and a between-person level.

Transformational Leadership and Leader Well-Being

Previous research has already highlighted associations between transformational leadership and leader well-being. Meta-analytic results (Kaluza et al., 2020) point towards a positive association. However, results from primary studies report divergent findings. Whereas some day-level (Lanaj et al., 2016) and longitudinal between-person studies (Arnold et al., 2015) align with the meta-analytic findings indicating that transformational leadership is associated with greater leader well-being, other within-person (Lin et al., 2019) and between-person results (Zwingmann et al., 2016) show an association with lower leader well-being.

Transformational leadership is a resource-intensive leadership style, therefore making resource investments necessary. As Lin et al. (2019) summarize, many actions reflective of transformational leadership deplete the leader’s resources, for example, emotion regulation to express positive emotions or time and energy to communicate visions and ideals to followers. However, drawing on COR theory, we propose that engaging in transformational leadership behavior will pay off for the leader in the end due to acquiring additional resources. People engage in short-term resource-depleting behavior because they can take a long-term outlook, striving to gain more resources and more desirable outcomes in the future (Hobfoll, 1989). We argue that transformational leadership constitutes behavior that makes resource investment necessary to acquire resources in the end. On the day-level, previous research already found transformational leadership to benefit leaders in terms of increased positive affect (Lanaj et al., 2016). Additionally, transformational leadership supports goal progress (Harris et al., 2003). Perceptions of reaching or getting closer to one’s goals are important resources and should be reflected in positive feelings of the leader (Johnson et al., 2013), hence equipping the leader with new energy to work towards goal accomplishment. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1:

At the between-person level, transformational leadership is positively related to vigor (H1a) and negatively to emotional exhaustion (H1b).

Hypothesis 2:

At the within-person level, transformational leadership is positively related to subsequent vigor (H2a) and negatively to subsequent emotional exhaustion (H2b).

Transformational Leadership and Occupational Self-Efficacy

Transformational leadership is an effective leadership style associated with relevant resources for leaders, such as employee performance (Ng, 2017) and goal accomplishment (van Dierendonck et al., 2014). Bandura (1977) stated that performance accomplishment is one of the four primary sources of self-efficacy. Thus, successfully coping with tasks will likely enhance an individual’s trust in their abilities. Therefore, feelings of success and goal accomplishment are likely to manifest themselves in greater occupational self-efficacy. Occupational self-efficacy includes many aspects that have been conceptualized as resources (e.g., feelings of success, goal accomplishment, and competence; Hobfoll, 2001). Occupational self-efficacy is a positive self-perception, which can be considered an essential resource for leaders. Based on COR theory, we assume that the resources for leaders associated with acting transformationally are, in turn, reflected in further resources; specifically, in higher occupational self-efficacy.

Previous research demonstrated connections between transformational leadership and follower (occupational) self-efficacy (Hentrich et al., 2017; Kovjanic et al., 2012; Tims et al., 2011), for example, via the fulfillment of the followers’ need for competence (Kovjanic et al., 2012). Transformational leaders regularly communicate challenging goals, which, combined with the expression of confidence that the goals will be reached, is likely to manifest itself in a greater sense of competence in followers (Kovjanic et al., 2012). At the same time, transformational leaders act as role models for their followers (Bass, 1985), so they are also likely to challenge themselves with their goals. Leaders must be optimistic about the future and show confidence in their abilities and strengths to reach these goals. Focusing on one’s strengths and previous successes can help fulfill leaders’ need for competence and will likely increase their occupational self-efficacy. Additionally, when leaders emphasize their followers’ strengths and abilities, they create a sense of “positive focus”, enhancing the focus on the leader’s resources. Recently, a positive association between daily transformational leadership and daily leader needs satisfaction (including the need for competence) has been demonstrated (Lanaj et al., 2016). Taken together, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3a:

At the between-person level, transformational leadership is positively related to occupational self-efficacy.

Hypothesis 3b:

At the within-person level, transformational leadership is positively related to subsequent occupational self-efficacy.

Transformational Leadership and Information Exchange

Transformational leadership involves many behaviors targeted at followers, such as challenging existing assumptions, communicating a vision, or dealing with the followers’ individual needs. Therefore, a leader needs to invest resources in interactions with the followers. In line with COR theory, individuals invest resources first to acquire further resources afterward. Similarly, leaders invest resources when demonstrating transformational leadership but likely benefit from their resource investment and gain additional resources, such as information. Information is an essential resource for leaders (Wu & Lee, 2016) as it is critical for the functioning of teams and the organization (S. Wang & Noe, 2010). The follower-directed behaviors of transformational leadership are likely to enhance a positive team and dyadic climate and to promote high-quality relationships, making it more likely that followers share more or more regularly information with their leader.

Additionally, transformational leadership was associated with increased followers’ trust in their leader (Breevaart & Zacher, 2019). When followers trust their leader, they are more willing to share important information with them (S. Wang & Noe, 2010). In addition, transformational leadership includes actions that aim at stimulating followers’ thoughts on tasks, problems, and their out-of-the-box thinking, as well as at emphasizing group spirit and shared identity and bringing the group to work together on tasks. Framing tasks as intellective and supporting a cooperative team climate (Mesmer-Magnus & Dechurch, 2009) and a high level of group cohesion (S. Wang & Noe, 2010) can enhance information exchange. Additionally, research showed that an innovation-enhancing culture, which is at the heart of transformational leadership as a change-oriented leadership style, can support knowledge sharing (Ruppel & Harrington, 2001). Therefore, we state the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4a:

At the between-person level, transformational leadership is positively related to information exchange.

Hypothesis 4b:

At the within-person level, transformational leadership is positively related to subsequent information exchange.

Transformational Leadership and Meaning of Work

When engaging in an effective leadership style such as transformational leadership, leaders are likely to perceive personal growth or the growth of followers. The perception of growth is a crucial resource for individuals (Hobfoll, 2001). In the light of COR theory, leaders can see their job as a way to gain new resources. It can be perceived as a source to bring in their competencies and develop themselves or others. In the context of resource losses, such as investing resources in demanding leadership behavior, resource gains, such as a positive attitude towards the job and evaluation of the job as being meaningful, increase in salience.

Furthermore, transformational leaders are likely to emphasize the importance and purpose of the work they and their followers are doing (Arnold et al., 2007). We propose that stressing a “higher purpose” will not only be associated with the followers’ (Nielsen et al., 2008; Perko et al., 2014) but also with the leaders’ perception of the job’s meaningfulness. This assumption aligns with the finding that task significance, that is, the perception that one’s work is beneficial for others, longitudinally leads to increased perceptions of the meaningfulness of one’s work (Allan, 2017). Leaders challenge their followers with high expectations and goals when demonstrating transformational leadership behavior. As outlined above, it is reasonable to assume that leaders also challenge themselves in this way. Creating challenging job demands for oneself (as part of job crafting) was related to more perceived meaningfulness of work via higher levels of person-job fit (Tims et al., 2016). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 5a:

At the between-person level, transformational leadership is positively related to meaning of work.

Hypothesis 5b:

At the within-person level, transformational leadership is positively related to subsequent meaning of work.

Leader Resources and Well-Being

From a theoretical perspective, COR theory proposes that resources do not exist in isolation but come in caravans (Hobfoll, 2011). Thus, possessing resources makes acquiring new resources, or at least conserving existing resources, more likely. Positive perceptions of oneself, such as high levels of occupational self-efficacy, are important resources for an individual. Therefore, having a high level of personal resources available (i.e., occupational self-efficacy) should also be reflected in greater well-being (i.e., lower levels of emotional exhaustion and higher levels of vigor). Meta-analytic (Alarcon et al., 2009; Shoji et al., 2016) and longitudinal studies (Avey et al., 2010; Taris et al., 2010) demonstrated that increased self-efficacy benefits individuals in terms of increased well-being.

Similarly, information and the sharing of information by the followers include several aspects that can be considered essential resources for leaders. On a task level, information sharing is related to goal progress and accomplishment, for example, due to better coordination and strategy formulation or the development of shared team cognition, and in turn to higher team and leader performance (Marlow et al., 2018). Additionally, on a socio-emotional level, information sharing reflects a positive climate of trust and cohesion (Mesmer-Magnus & Dechurch, 2009). The perceptions that followers trust themselves as a leader and are willing to support the leader’s and the team’s goals by sharing information are positive for leaders and should be associated with greater well-being.

Meaningful work can be considered a critical psychological state (Oldham & Hackman, 2010), which was found to be associated with increased well-being (Allan et al., 2018). More specifically, the association of meaningful work with work engagement (including vigor) seems to be large (Allan et al., 2018). Meaningful work is likely to enhance a resource gain spiral, for example, through positive work reflection (Jiang & Johnson, 2018), which is likely to be positively related to increased well-being. Indeed, in an experimental intervention, positive work reflection was associated with decreased emotional exhaustion (Clauss et al., 2018). Similarly, longitudinal studies showed that work meaningfulness was related to increased work engagement (Lee et al., 2017) and decreased emotional exhaustion (Kim & Beehr, 2018). These findings demonstrate that having meaningful work is beneficial for individuals’ well-being. Thus, we state:

Hypothesis 6:

At the between-person level, occupational self-efficacy (H6a), information exchange (H6b), and meaning of work (H6c) are positively related to vigor.

Hypothesis 7:

At the between-person level, occupational self-efficacy (H7a), information exchange (H7b), and meaning of work (H7c) are negatively related to emotional exhaustion.

Hypothesis 8:

At the within-person level, occupational self-efficacy (H8a), information exchange (H8b), and meaning of work (H8c) are positively related to subsequent vigor.

Hypothesis 9:

At the within-person level, occupational self-efficacy (H9a), information exchange (H9b), and meaning of work (H9c) are negatively related to subsequent emotional exhaustion.

The Mediating Role of Occupational Self-Efficacy, Information Exchange, and Meaningful Work

We propose that transformational leadership pays off for the leader’s well-being by acquiring additional resources. However, as we will come to see, while the mediating relationships are expected, we find no support for those. We hypothesize that in line with COR theory, demonstrating behavior reflective of transformational leadership is likely to start a resource gain process for the leader, reflected by greater leader well-being. More specifically, we suggest that higher leader well-being can be partly explained by resource acquisition at the individual, team, and job levels. We expect transformational leadership to be associated with higher leader occupational self-efficacy, information exchange of followers with their leader, and meaningfulness of leaders’ work. These states (i.e., the perception that one can deal with problems and challenges in the job, that the followers are providing one with important information for personal and team progress, and that the job one is doing is personally meaningful to oneself and has an impact on others) constitute essential resources for a leader, which in turn will be associated with greater leader well-being. Taken together, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 10:

At the within-person level, the association of transformational leadership and vigor will be mediated by occupational self-efficacy (H10a), information exchange (H10b), and meaning of work (H10c).

Hypothesis 11:

At the within-person level, the association of transformational leadership and emotional exhaustion will be mediated by occupational self-efficacy (H11a), information exchange (H11b), and meaning of work (H11c).

Reciprocal Relationships

We will also test potential reciprocal relationships between transformational leadership and leader well-being. COR theory’s so-called “desperation principle” describes that when people’s resources are exhausted, they “enter a defensive mode to preserve the self, which is often defensive, aggressive, and may become irrational” (Hobfoll et al., 2018, p. 106). Hence, individuals aim to preserve the resources they have left. Consequently, they are more likely to turn their attention to personal needs instead of the needs of others (Hobfoll, 2001). Due to the idea that resource loss is more salient than resource gain (Hobfoll, 1989), leaders are unlikely to invest further resources, for example, demonstrating behavior reflective of transformational leadership, even though this resource investment might pay off in the long term. Instead, leaders may engage in defensive behavior to protect their resources. In line with COR theory, leaders who report low levels of vigor or high levels of emotional exhaustion may have insufficient resources to engage in proactive and resource-expensive behavior. In contrast, leaders high in vigor or low in emotional exhaustion have enough resources to invest in proactive, constructive, and resource-building behavior, such as transformational leadership, to acquire more resources later.

Furthermore, based on COR theory’s resource caravan proposition (Hobfoll, 2011), we can expect resource gain (for those with more resources) and loss cycles (for those with fewer resources). Specifically, leaders reporting more well-being are more likely to perceive or use their resources or even gain additional resources (i.e., occupational self-efficacy, information exchange, and meaning of work). In turn, leaders with a larger resource pool are more likely to show more transformational leadership, which could again benefit their well-being, and so on.

Our theoretical assumptions are supported by existing research showing that a high amount of resources can be an important antecedent of transformational leadership. For example, reduced leader resources were associated with less transformational leadership (Byrne et al., 2014; Diebig et al., 2017; Harms et al., 2017), and work engagement and transformational leadership were found to be reciprocally related on a between-person level (Geibel et al., 2022). Therefore, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 12:

There are reciprocal relationships between transformational leader behavior, leader resources (i.e., occupational self-efficacy, information exchange, and meaning of work), and leader well-being (i.e., vigor and emotional exhaustion). More specifically, both relationships, the path from leadership behavior to well-being and the path from well-being to leadership behavior are simultaneously valid.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Our study was approved by the ethical committee of our institution. We collected data from leaders in different industries and organizations and recruited them through direct contacts, flyers, and postings on websites and social media. The study consisted of a baseline online survey and three weekly online surveys. We chose a weekly interval to follow Guthier et al.’s (2020) call for more longitudinal well-being research covering shorter time intervals. Additionally, the weekly interval is long enough to allow the leaders to interact with their followers and demonstrate leadership behavior. At the same time, it is short enough so leaders can still respond to the study variables, thereby reducing retrospective bias. Our three-week period is well-suited to catch within-person changes in leadership and well-being from one week to the next as it increases the likelihood that the working situations from week to week differ substantially.

After registration for the project, leaders received a link to the baseline survey, which they completed before the start of the weekly surveys. The baseline survey included measures of demographics and baseline variables. Next, in the weekly data collection, we sent the leaders a survey at the end of each week. In the weekly surveys, the leaders reported on their leadership behavior, occupational self-efficacy, information exchange with their followers, meaningfulness of their work, and well-being. The time between the baseline survey and the first weekly survey differed between leaders as they could choose freely at what time after registration and before the first weekly survey they completed the baseline survey. On average, leaders completed the baseline survey between one and two weeks before the first weekly survey (M = 12.86 days). Only leaders who completed the baseline survey were able to answer the weekly surveys.

Of 221 leaders who initially registered to participate in the study, 185 completed the baseline survey (response rate: 84%). 110 leaders completed the first weekly survey (response rate: 50%), 98 leaders completed the second weekly survey (response rate: 44%), and 77 leaders completed the third weekly survey (response rate: 35%). 46 leaders completed all four surveys. Our sample comprised 132 leaders (54% male) who answered the baseline and at least one weekly survey. The average age was 46.49 years (SD = 10.21), their average organizational tenure was 12.51 (SD = 9.73) years, and their average leadership tenure was 10.80 (SD = 8.33) years. Leaders’ average working experience was 13.99 (SD = 10.52) years, and they worked 45.60 h per week (SD = 8.19). The participants came from different industries and worked in various job sectors, such as education, consulting, health, science, law, hotel business, or technology.

Measures

We formulated the items in the weekly surveys to capture the variables’ levels during the respective week. All items were assessed in the German language. When German items of the instruments were unavailable (i.e., for information exchange and meaning of work), we used the translation and back-translation method to translate the items (Brislin, 1970). Any discrepancies were discussed by the authors of the present study and the translating research assistant and a final solution was agreed on.

Transformational leadership. Transformational leadership behavior was assessed using the respective items of the German version of the MLQ Form 5x Short (Felfe, 2006), adapted to fit the leader’s perspective. A sample item for transformational leadership is “I formulate a convincing vision for the future.” Ratings were made on a 5-point scale. For transformational leadership, Cronbach’s α was 0.82 in the baseline survey, and 0.90 averaged across the weeks.

Occupational self-efficacy. Leaders rated their occupational self-efficacy using the 6-item short version of the Occupational Self-Efficacy Scale (Rigotti et al., 2008). A sample item is “When I am confronted with a problem in my job, I can usually find several solutions.” Ratings were made on a 5-point scale. Cronbach’s α was 0.81 in the baseline survey, and 0.85 averaged across the weeks.

Information exchange. Information exchange was assessed with the question “How often do your followers share the following information with you” developed by Cummings (2004) and adapted for the present study. The information asked for were: general overviews, analytical techniques, progress reports, project results, and specific requirements. Ratings were made on a 5-point scale. Cronbach’s α was 0.75 in the baseline survey, and 0.81 averaged across the weeks.

Meaningfulness of work. Meaningfulness of work was rated using the 10-item Work and Meaning Inventory (Steger et al., 2012). A sample item is “I have a good sense of what makes my job meaningful.” Ratings were made on a 5-point scale. Cronbach’s α was 0.86 in the baseline survey, and 0.88 averaged across the weeks.

Emotional exhaustion. Emotional exhaustion was assessed with the respective 8-item subscale of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) (Demerouti et al., 2003). A sample item is “After my work, I regularly feel worn out and weary.” Ratings were made on a 4-point scale. Cronbach’s α was 0.76 in the baseline survey, and 0.88 averaged across the weeks.

Vigor. Vigor was rated with the 6-item subscale of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) (Schaufeli et al., 2002). A sample item is “At my work, I feel bursting with energy.” Ratings were made on a 5-point scale. Cronbach’s α was 0.80 in the baseline survey, and 0.84 averaged across the weeks.

Missing Data

To check for non-random sampling in our study, we performed drop-out analyses following the procedure suggested by Goodman (1996). We conducted a binary logistic regression in which we regressed the participation pattern (participants who only completed maximum three surveys vs. participants who completed all four surveys, i.e., the general survey as well as all three weekly surveys) on age, sex, general weekly working hours, leadership tenure, and our focal study variables at the general level. None of the variables significantly predicted the participation pattern. Additionally, we did not find differences between the two groups in mean scores for the study variables in the general survey or one of the weekly surveys. Therefore, we have a missing pattern representing a situation of missing completely at random. To handle missing values, we used full information maximum-likelihood estimation (FIML) with robust standard errors (Enders & Bandalos, 2001; Graham, 2009). FIML estimates missing values based on all available data points and uses all existing values to estimate model parameters. This procedure allows us to draw conclusions on associations from one week to the next, even though not all participants answered the surveys for two consecutive weeks.

Analytic Approach

We conducted our analyses using the “lavaan” package (Rosseel, 2012) for R with a maximum likelihood estimator. We initially ran confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to support our factor structure. We tested our hypotheses simultaneously using the RI-CLPM (Hamaker et al., 2015). The RI-CLPM was introduced recently by Hamaker et al. (2015) as an alternative model that separates within-person processes from stable between-person differences. Specifically, in a RI-CLPM the observed score variance is decomposed into grand means (i.e., the means over all leaders per measurement point), stable between components, which are the random intercepts capturing a leader’s time-invariant deviation from the grand means (i.e., representing the stable differences between leaders), and last the within components, which are the differences between a leader’s observed measurements and the leader’s expected score (Mulder & Hamaker, 2020).

The expected score is computed for each leader based on the sample mean levels across the three weeks and the individual stable trait factor. Therefore, the within-person level variance represents leaders’ deviations from their own expected scores (Alisic & Wiese, 2020). The correlation between the random intercepts reflects the relationship of stable between-person differences in one variable and the stable between-person differences in another variable. The within-person correlation at T1 indicates the association between within-person deviations in one variable and deviations from own scores in another variable. The correlated change at T2 and T3 reflects the degree to which a within-person change in one variable is related to a within-person change in another variable, independent from the relationship at the previous wave. The stability (i.e., autoregressive) effects express the extent to which within-person deviations in the variables can be predicted by the leader’s previous deviation from the own expected score. Cross-lagged effects indicate to what extent changes in a leader’s individual level of a variable (e.g., vigor) are predicted by deviations from the own expected score in another variable (e.g., transformational leadership) one week earlier (and vice versa) (Alisic & Wiese, 2020; Hamaker et al., 2015).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for our study variables are shown in Table 1. Calculations of intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) indicated within-person variances from 19% (meaning of work) to 42% (information exchange), which supports our separate analysis of between- and within-person relations.

We conducted CFAs to support the fit of our proposed model structure. The six-factor model with our variables transformational leadership, occupational self-efficacy, information exchange, meaning of work, vigor, and emotional exhaustion fit the data well (χ2 = 1388.322, df = 1227, p < .001, CFI = 0.926, RMSEA = 0.034, SRMR = 0.090) and better than a one-factor model with all items loading on one factor (χ2 = 2601.328, df = 1325, p < .001, CFI = 0.412, RMSEA = 0.092, SRMR = 0.109; Δχ2 = 1213.006, df = 98, p < .001).

Hypotheses Testing

We specified two RI-CLPM models to test whether there were changes across the time points. Therefore, we specified one unconstrained RI-CLPM that allowed the autoregressive and cross-lagged effects to vary across the waves and one constrained model that fixed these parameters to equality (see Hamaker et al., 2015; Mulder & Hamaker, 2020). However, the unconstrained model did not converge, so we could not compare the unconstrained and the constrained models. Nevertheless, the constrained model fit the data acceptably well (χ2 = 140.143, df = 72, p < .001, CFI = 0.935, RMSEA = 0.085, SRMR = 0.109) and is also in line with our hypotheses that refer to within-person relations rather than changes across the time points. Tables 2 and 3 show the results of the constrained RI-CLPM. Figure 2 shows a graphical representation of the significant findings.

In line with our hypotheses 1a, 3a, 4a, and 5a, on a between-person level of analysis, transformational leadership was positively related to vigor (rxy = 0.112; p = .011), occupational self-efficacy (rxy = 0.076; p = .010), information exchange (rxy = 0.175; p < .001), and meaning of work (rxy = 0.137; p = .005). In support of hypotheses 6a and 7a, occupational self-efficacy was positively related to vigor (rxy = 0.138; p < .001) and negatively related to emotional exhaustion (rxy = − 0.079; p = .013). Contrary to hypothesis 1b, transformational leadership was not associated with emotional exhaustion. Additionally, there was no support for hypotheses 6b, 6c, 7b, and 7c as information exchange and meaning of work were neither related to vigor nor emotional exhaustion.

At the within-person level, transformational leadership did not significantly predict subsequent vigor, emotional exhaustion, occupational self-efficacy, information exchange, or meaning of work. Additionally, neither occupational self-efficacy, information exchange, nor meaning of work predicted subsequent vigor or emotional exhaustion. Therefore, hypotheses 2a, 2b, 3b, 4b, 5b, 8a, 8b, 8c, 9a, 9b, and 9c, as well as our mediation hypotheses 10a, 10b, 10c, 11a, 11b, and 11c, were not supported.

However, we found significant within-person associations within the second and the third week, respectively. The results were the same for both weeks as we analyzed the constrained model. Transformational leadership was positively related to occupational self-efficacy (rxy = 0.060; p < .001), meaning of work (rxy = 0.045; p = .003), vigor (rxy = 0.050; p = .004), and negatively to emotional exhaustion (rxy = − 0.050; p = .001). Additionally, occupational self-efficacy was positively related to vigor (rxy = 0.060; p = .003) and negatively to emotional exhaustion (rxy = − 0.042; p = .039), and meaning of work was positively related to vigor (rxy = 0.065; p < .001).

Last, regarding hypothesis 12, vigor positively predicted subsequent information exchange (B = 0.363; p = .040) and meaning of work (B = 0.421; p = .001). Neither vigor nor emotional exhaustion predicted subsequent transformational leadership.Footnote 1

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated between- and within-person associations between transformational leadership and leaders’ well-being. Specifically, across three consecutive weeks, we aimed to examine the directionality of the relationships and potential mechanisms to explain the associations. We found that, on a within-person level, transformational leadership in one week was unrelated to leaders’ resources or well-being in the next week and vice versa. That means that a higher or lower amount of transformational leadership, compared to a leader’s typical score, is not reflected in a higher or lower amount of their resources or well-being, compared to their respective typical score, in the subsequent week. Furthermore, there was no evidence for reciprocal associations between transformational leadership and the other study variables. However, on a within-person level, in weeks in which leaders reported a greater amount of transformational leadership than their typical score, they reported increased occupational self-efficacy, meaning of work, vigor, and decreased emotional exhaustion in the same week. Additionally, on a between-person level, leaders who showed more transformational leadership than other leaders also reported higher occupational self-efficacy, information exchange, meaning of work, and vigor than other leaders.

Theoretical Implications

In our study, leaders who showed more transformational leadership behaviors than other leaders reported higher levels of well-being. This finding on a between-person level aligns with previous meta-analytic results (Kaluza et al., 2020), showing positive associations between transformational leadership and leader well-being. Our study extends existing between-person research by demonstrating that occupational self-efficacy, information exchange, and meaning of work are specific resources that leaders higher in transformational leadership possess to a greater extent than leaders lower in transformational leadership.

Additionally, on a within-person level, leaders reported greater well-being within one week in which they also indicated more transformational leadership behaviors. This finding aligns with previous within-person research (Lanaj et al., 2016) on the beneficial effects of transformational leadership for leaders. However, our result is opposed to other research that found on a weekly level that more transformational leadership was related to increased leader emotional exhaustion from the previous week (Lin et al., 2019). In their study, transformational leadership was interpreted as resource depleting for leaders; therefore, these authors pointed to a potential dark side of transformational leadership for leaders themselves. In contrast, our study suggests that higher levels of transformational leadership are related to increased well-being for leaders in the same week, which supports the view that this leadership style is not only beneficial for followers’ well-being (Montano et al., 2017) but, at least within one week, also for leaders’ well-being. As we were able to disentangle between-person from within-person effects, our study shows that variations in one’s amount of transformational leadership are associated with variations in one’s well-being within one week.

Furthermore, also on a within-person level, we found transformational leadership to be associated with increased personal (i.e., occupational self-efficacy) and job (i.e., meaning of work) resources within leaders. Leaders who reported more transformational leadership behaviors during one week compared to their typical level of transformational leadership reported increased occupational self-efficacy and meaning of work in the same week. Our findings suggest that both person-level and job-level resources vary in accordance with variations of transformational leadership.

Regarding the question of the directionality raised by other scholars (e.g., Kaluza et al., 2020), we neither found support for the direction of transformational leadership ◊ well-being nor the direction of well-being ◊ transformational leadership. As we did not find cross-lagged effects associated with transformational leadership from one week to the next, our study suggests that the relationship between transformational leadership and well-being does not transfer over one week. Future research might consider weekend recovery experiences to better align work and non-work experiences with each other.

Considering our hypothesis on reciprocal relationships regarding well-being as a predictor for increased transformational leadership, we found partial support for our assumptions. Leaders who experienced greater vigor in one week than in other weeks also reported more information exchange with their followers and greater meaning of work in the next week compared to other weeks.

Our findings have important implications for COR theory (Hobfoll et al., 2018). In line with the theory stating that resources do not exist individually, we found that transformational leadership comes together with greater resources, both within one week and on a general level. Also aligned with theory, our findings suggest that leaders who feel vigorous and full of energy enter a resource gain cycle and that this resourceful state transfers to the following week. However, our results do not seem to align with two central principles of COR theory. First, in our study, the resource gain (or loss) cycle does not include transformational leadership in either of the two possible directions. This finding is surprising given the multiple associations of transformational leadership with resources. An essential next step could be examining factors that might hinder the beneficial same-time effects of transformational leadership from being reflected in dynamic resource gains across time.

Second, we could not find evidence for the resource investment principle. As transformational leadership was associated with more resources, one might assume that resources had to be invested at some point. However, this investment was not reflected in our data as this, for example, should have been indicated by lower well-being. We can imagine that one answer to that can be found in the timing of our study. For example, the investment of resources could have taken place within one day so that when the surveys were answered at the end of the week, the initial losses already changed into resource gains. This issue might also be relevant for the between- vs. within-person discussion outlined at the beginning of this paper. Even though the relationships were in the same direction across levels in our study, this might be different in other studies that focus on different time frames (i.e., a negative short-term within-person association with well-being due to the investment of resources vs. a positive between-person association when the positive effects had enough time to unfold). Therefore, an important aspect for future COR theory-directed research on transformational leadership and leader well-being (and possibly also for other areas) is to find out at what point resources are invested, how steep the primary loss is, and at what point new resources are gained instead and how large this gain is.

Additionally, the accumulation of resource investment and gain could be of interest: Imagine one leader with steady resource investment but also steady resource gain. Imagine another leader with steady resource investment but only a delayed (but perhaps in total larger) resource gain. Which of the two leaders has a greater “final” amount of resources? Answering questions like these could help move research on transformational leadership, leader well-being, and COR theory forward. In line with previous studies on within-person research (Ilies et al., 2015; Podsakoff et al., 2019), the within and between-person perspective could be integrated more strongly in the current COR theory. The goal should be to link intraindividual variations to longer-term (between-person) outcomes. In this way, previous unexpected findings might not necessarily speak against the validity of a theory but rather be an expression of the multilevel nature of the theory and its processes.

Practical Implications

The findings of our study suggest that leaders who report more transformational leadership behaviors than others also report greater vigor, more occupational self-efficacy, information exchange, and meaning of work than others. Drawing on this finding, one important aspect is sensitizing leaders to the fact that their leadership behavior is related to self-relevant variables. Additionally, in our study, transformational leadership was associated with more resources and greater well-being. Therefore, leaders should be encouraged to strive for higher levels of transformational leadership behaviors. Organizations can also facilitate higher levels of transformational leadership by providing their leaders with training on transformational leadership.

Second, from our study’s within-person findings, we can conclude that showing more transformational leadership compared to one’s typical level is associated with increased occupational self-efficacy, meaning of work, vigor, and decreased emotional exhaustion. This finding supports the notion that leaders should regularly try to find ways to demonstrate behaviors reflective of transformational leadership. They can do this, for example, by encouraging themselves and their followers to try new approaches to solve problems, setting high and ambitious goals and expressing confidence that these goals will be reached, or by dealing with each follower’s needs and wishes.

Limitations and Future Research

We acknowledge some limitations of our research. First, we used leader ratings only. Even though leaders are well-suited to report on their well-being, their leadership ratings can be susceptible to common-method or self-enhancement bias (Atwater et al., 1998; Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, especially in light of our weekly assessments, it is likely that followers would have witnessed their leader’s behaviors only partly (e.g., Allen et al., 2000). Therefore, leaders will likely have a complete picture of their leadership behavior throughout the week (Chan, 2008). Nevertheless, we encourage future research to build on our findings and use other sources for leadership ratings, such as followers, superiors, or behavioral ratings (Heimann et al., 2020; Lord et al., 2017).

Second, we focused on transformational leadership in our study. However, other leadership constructs have also been shown to be associated with leader well-being, such as servant leadership (e.g., Liao et al., 2020), destructive leadership (e.g., Qin et al., 2018) or leader-member relationships (LMR; London et al., 2023) and could therefore be relevant to be studied (in combination) in future research. Furthermore, it would be interesting to investigate moderators of the relationships, such as differential follower reactions to transformational leadership (Tepper et al., 2018).

Additionally, in our conceptualization of well-being, we focused on the energy aspect of well-being. Even though vigor and emotional exhaustion are central indicators of momentary leader well-being, well-being is a broad concept with more facets than just energy (Sonnentag, 2015). For example, next to the rather hedonic view that we applied (Diener, 2000), other approaches refer to a eudaimonic perspective focusing on personal growth, authenticity, and feeling meaningful in one’s life (e.g., Ryff, 1995). Therefore, there are other aspects of leader well-being relevant to be studied. As the associations of transformational leadership with well-being might look different depending on the understanding of well-being, we encourage future research to investigate the relationship with indicators of eudaimonic well-being as well.

Third, our research design did not allow for drawing causal inferences. Therefore, in line with recent studies on experiments in leadership research (Schowalter & Volmer, 2023), we propose using experiments or controlled leadership interventions to establish causality for the relationship between leadership behavior and leader well-being.

Last, we investigated our constructs for three consecutive weeks to catch the dynamics of leadership behaviors and leader well-being in a relatively short time (i.e., from one week to the next). However, research lacks a clear theory on the periods over which the proposed effects can occur. Connected to this, we only considered three weeks in our study. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that the expected associations between the constructs need more time to unfold and that the effects differ across a longer period – or the one-week interval was too long, and shorter time lags would have been more appropriate.

In line with recent suggestions on the leadership – employee well-being link (Rudolph et al., 2022), we invite future research to work on a more robust theory on the timing of effects of leadership behavior and leader well-being and vice-versa to gain a better understanding of optimal time lags and periods. The optimal time lag is dependent on “the nature of the substantive construct, its underlying process of change over time, and the context in which the change process is occurring, which includes the presence of variables that influence the nature and rate of the change” (Wang et al., 2017, p. 10). Even though there is no clear answer on these aspects, at least for the variables of the present study, existent findings on within-person variability can help to get an idea about the stability of variables and the time needed for relationships to unfold. For example, an analysis of within-person variability in experience sampling studies showed larger within-person variance in some constructs (e.g., sleep-related measures) than in other constructs (e.g., satisfaction) (Podsakoff et al., 2019). These results could indicate that constructs with higher within-person variability can change (or be changed) faster than those with lower within-person variability.

A complementary and somewhat analytical approach could be to estimate optimal time lags in longitudinal studies. Based on the stability of the investigated variables, pilot studies with short lags can help to provide information about the expected distribution of effects over time (Dormann & Griffin, 2015). Another option might be to apply continuous time modeling, in which time is treated as a continuum and which, therefore, allows varying time intervals both within and between participants (Voelkle et al., 2018). As models of occupational health often describe continuous (vs. discrete) effects, a continuous, intentionally time-varying approach could be promising for the field (Rauvola et al., 2021).

Conclusion

On a general level and within weeks, we consider transformational leadership as a resource for leaders that is beneficial for the leaders themselves. In our study, transformational leadership was associated with greater well-being and more resources for leaders on the within- and between-person level of analysis. However, the associations seem not to transfer from one week to the next. Our study supports a resource-based perspective on leadership by showing occupational self-efficacy, information exchange, and meaning of work as concrete resources for leaders acting transformationally. Methodologically, we demonstrated the RI-CLPM as an adequate modeling strategy to disentangle between- and within-person relations. This approach can also be advantageous for leadership researchers to catch the longitudinal interplay of the focal variables. We hope our study stimulates further research on the reciprocity of leadership behavior and leader well-being.

Notes

Our focus was on transformational leadership as an overall construct, given high intercorrelations of the dimensions of transformational leadership (Carless, 1998; Felfe, 2006). However, on an exploratory basis, we also conducted the analyses with the separate dimensions. For idealized influence, the results were similar to those of the overall model. For inspirational motivation and individualized consideration, respectively, the associations mostly aligned with those of the overall model regarding their direction. However, compared to the overall model, the strengths of the associations were partly somewhat smaller, and some associations could not be found. The model with intellectual stimulation did not converge. The detailed results are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Alarcon, G., Eschleman, K. J., & Bowling, N. A. (2009). Relationships between burnout: A meta-analysis. Work & stress, 23(3), 244–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370903282600.

Alisic, A., & Wiese, B. S. (2020). Keeping an insecure career under control: The longitudinal interplay of career insecurity, self-management, and self-efficacy. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 120, 103431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103431.

Allan, B. A. (2017). Task significance and meaningful work: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102, 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.07.011.

Allan, B. A., Autin, K. L., & Duffy, R. D. (2014). Examining social class and work meaning within the psychology of working framework. Journal of Career Assessment, 22(4), 543–561. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072713514811.

Allan, B. A., Batz-Barbarich, C., Sterling, H. M., & Tay, L. (2019). Outcomes of meaningful work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 56(3), 500–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12406.

Allan, B. A., Duffy, R. D., & Collisson, B. (2018). Helping others increases meaningful work: Evidence from three experiments. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(2), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000228.

Allen, T. D., Barnard, S., Rush, M. C., & Russell, J. E. (2000). Ratings of organizational citizenship behavior: Does the source make a difference? Human Resource Management Review, 10(1), 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1053-4822(99)00041-8.

Arnold, K. A., Connelly, C. E., Walsh, M. M., & Martin Ginis, K. A. (2015). Leadership styles, emotion regulation, and burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(4), 481–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039045.

Arnold, K. A., Turner, N., Barling, J., Kelloway, E. K., & McKee, M. C. (2007). Transformational leadership and psychological well-being: The mediating role of meaningful work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(3), 193–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.193.

Atwater, L. E., Ostroff, C., Yammarino, F. J., & Fleenor, J. W. (1998). Self-other agreement: Does it really matter? Personnel Psychology, 51(3), 577–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1998.tb00252.x.

Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., Smith, R. M., & Palmer, N. F. (2010). Impact of positive psychological capital on employee well-being over time. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016998.

Bakker, A. B., Albrecht, S. L., & Leiter, M. P. (2011). Key questions regarding work engagement. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(1), 4–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2010.485352.

Bakker, A. B., & Oerlemans, W. G. M. (2012). Subjective well-being in organizations. In K. S. Cameron, & G. M. Spreitzer (Eds.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship (pp. 178–189). Oxford University Press.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall series in social learning theory. Prentice-Hall.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Free Press.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (Eds.). (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. SAGE Publications. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0655/93030874-d.html.

Breevaart, K., & Zacher, H. (2019). Main and interactive effects of weekly transformational and laissez-faire leadership on followers’ trust in the leader and leader effectiveness. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(2), 384–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12253.

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301.

Byrne, A., Dionisi, A. M., Barling, J., Akers, A., Robertson, J., Lys, R., Wylie, J., & Dupré, K. (2014). The depleted leader: The influence of leaders’ diminished psychological resources on leadership behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(2), 344–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.09.003.

Carless, S. A. (1998). Assessing the discriminant validity of transformational leader behaviour as measured by the MLQ. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 71(4), 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1998.tb00681.x.

Chan, D. (2008). So why ask me? Are self-report data really that bad? In C. E. Lance & R. J. Vandenberg (Eds.), Statistical and methodological myths and urban legends (pp. 329–356). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203867266-22.

Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., & Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 89–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x.

Clauss, E., Hoppe, A., O’Shea, D., González Morales, M. G., Steidle, A., & Michel, A. (2018). Promoting personal resources and reducing exhaustion through positive work reflection among caregivers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000063.

Cummings, J. N. (2004). Work groups, structural diversity, and knowledge sharing in a global organization. Management Science, 50(3), 352–364. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1030.0134.

Day, D. V., Sin, H. P., & Chen, T. T. (2004). Assessing the burdens of leadership: Effects of formal leadership roles on individual performance over time. Personnel Psychology, 57(3), 573–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2004.00001.x.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Vardakou, I., & Kantas, A. (2003). The convergent validity of two burnout instruments: A multitrait-multimethod analysis. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1027//1015-5759.19.1.12.

DeRue, D. S., Nahrgang, J. D., Wellman, N., & Humphrey, S. E. (2011). Trait and behavioral theories of leadership: An integration and meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 7–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01201.x.

Diebig, M., Poethke, U., & Rowold, J. (2017). Leader strain and follower burnout: Exploring the role of transformational leadership behaviour. German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift Für Personalforschung, 31(4), 329–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002217721077.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34.

Dormann, C., & Griffin, M. A. (2015). Optimal time lags in panel studies. Psychological Methods, 20(4), 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000041.

Enders, C. K., & Bandalos, D. L. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 8(3), 430–457.

Felfe, J. (2006). Validierung einer deutschen Version des “Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire“ (MLQ Form 5 x Short) von Bass und Avolio (1995) [Validation of a German version of the ‘Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire’ (MLQ Form 5x Short) by Bass and Avolio (1995)]. Zeitschrift Für Arbeits- Und Organisationspsychologie A&O, 50(2), 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1026/0932-4089.50.2.61.

Geibel, H. V., Rigotti, T., & Otto, K. (2022). It all comes back to health: A three-wave cross-lagged study of leaders’ well-being, team performance, and transformational leadership. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 52(7), 532–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12877.

Goodman, J. (1996). Assessing the non-random sampling effects of subject attrition in longitudinal research. Journal of Management, 22(4), 627–652. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(96)90027-6.

Graham, J. W. (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 549–576. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530.

Guthier, C., Dormann, C., & Voelkle, M. C. (2020). Reciprocal effects between job stressors and burnout: A continuous time meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 146(12), 1146–1173. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000304.

Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., & Grasman, R. P. P. P. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889.

Harms, P. D., Credé, M., Tynan, M., Leon, M., & Jeung, W. (2017). Leadership and stress: A meta-analytic review. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(1), 178–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.10.006.

Harris, C., Daniels, K., & Briner, R. B. (2003). A daily diary study of goals and affective well-being at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76(3), 401–410. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317903769647256.

Heimann, A. L., Ingold, P. V., & Kleinmann, M. (2020). Tell us about your leadership style: A structured interview approach for assessing leadership behavior constructs. The Leadership Quarterly, 31(4), 101364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.101364.

Hentrich, S., Zimber, A., Garbade, S. F., Gregersen, S., Nienhaus, A., & Petermann, F. (2017). Relationships between transformational leadership and health: The mediating role of perceived job demands and occupational self-efficacy. International Journal of Stress Management, 24(1), 34–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000027.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016.x.

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640.

Huang, J., Wang, Y., Wu, G., & You, X. (2016). Crossover of burnout from leaders to followers: A longitudinal study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(6), 849–861. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2016.1167682.

Ilies, R., Aw, S. S. Y., & Pluut, H. (2015). Intraindividual models of employee well-being: What have we learned and where do we go from here? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(6), 827–838. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2015.1071422.

Ilies, R., Dimotakis, N., & De Pater, I. E. (2010). Psychological and physiological reactions to high workloads: Implications for well-being. Personnel Psychology, 63(2), 407–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01175.x.

Jiang, L., & Johnson, M. J. (2018). Meaningful work and affective commitment: A moderated mediation model of positive work reflection and work centrality. Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(4), 545–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-017-9509-6.

Johnson, R. E., Howe, M., & Chang, C. H. (2013). The importance of velocity, or why speed may matter more than distance. Organizational Psychology Review, 3(1), 62–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386612463836.

Kaluza, A. J., Boer, D., Buengeler, C., & van Dick, R. (2020). Leadership behaviour and leader self-reported well-being: A review, integration and meta-analytic examination. Work & Stress, 34(1), 34–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2019.1617369.

Kelemen, T. K., Matthews, S. H., & Breevaart, K. (2020). Leading day-to-day: A review of the daily causes and consequences of leadership behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 31(1), 101344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.101344.

Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2018). Organization-based self-esteem and meaningful work mediate effects of empowering leadership on employee behaviors and well-being. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 25(4), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051818762337.

Kovjanic, S., Schuh, S. C., Jonas, K., van Quaquebeke, N., & van Dick, R. (2012). How do transformational leaders foster positive employee outcomes? A self-determination-based analysis of employees’ needs as mediating links. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1031–1052. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1771.

Lanaj, K., Johnson, R. E., & Lee, S. M. (2016). Benefits of transformational behaviors for leaders: A daily investigation of leader behaviors and need fulfillment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(2), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000052.

Lee, M. C. C., Idris, M. A., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2017). The linkages between hierarchical culture and empowering leadership and their effects on employees’ work engagement: Work meaningfulness as a mediator. International Journal of Stress Management, 24(4), 392–415. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000043.

Lin, S. H., Scott, B. A., & Matta, F. K. (2019). The dark side of transformational leader behaviors for leaders themselves: A conservation of resources perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 62(5), 1556–1582. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.1255.

Li, W. D., Schaubroeck, J. M., Xie, J. L., & Keller, A. C. (2018). Is being a leader a mixed blessing? A dual-pathway model linking leadership role occupancy to well-being. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(8), 971–989. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2273.

London, M., Volmer, J., & Zyberaj, J. (2023). Beyond LMX: Toward a theory-based, differentiated view of leader–member relationships. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 38(4), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-10-2022-0513.

Lord, R. G., Day, D. V., Zaccaro, S. J., Avolio, B. J., & Eagly, A. H. (2017). Leadership in applied psychology: Three waves of theory and research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 434–451. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000089.

Mackey, J. D., Frieder, R. E., Brees, J. R., & Martinko, M. J. (2017). Abusive supervision: A meta-analysis and empirical review. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1940–1965. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315573997.

Marlow, S. L., Lacerenza, C. N., Paoletti, J., Burke, C. S., & Salas, E. (2018). Does team communication represent a one-size-fits-all approach? A meta-analysis of team communication and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 144, 145–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2017.08.001.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397.

McClean, S. T., Barnes, C. M., Courtright, S. H., & Johnson, R. E. (2019). Resetting the clock on dynamic leader behaviors: A conceptual integration and agenda for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 13(2), 479–508. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2017.0081.

McCormick, B. W., Reeves, C. J., Downes, P. E., Li, N., & Ilies, R. (2020). Scientific contributions of within-person research in management: Making the juice worth the squeeze. Journal of Management, 46(2), 321–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318788435.

Mesmer-Magnus, J. R., & Dechurch, L. A. (2009). Information sharing and team performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 535–546. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013773.

Montano, D., Reeske, A., Franke, F., & Hüffmeier, J. (2017). Leadership, followers’ mental health and job performance in organizations: A comprehensive meta-analysis from an occupational health perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(3), 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2124.

Montano, D., Schleu, J. E., & Hüffmeier, J. (2022). A meta-analysis of the relative contribution of leadership styles to followers’ mental health. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 30(1), 90–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/15480518221114854.

Mulder, J. D., & Hamaker, E. L. (2020). Three extensions of the random intercept cross-lagged panel model. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 28(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2020.1784738.

Ng, T. W. (2017). Transformational leadership and performance outcomes: Analyses of multiple mediation pathways. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(3), 385–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.11.008.