Abstract

Recent reports from across the developed world indicate that adverse mental health conditions are prevalent in society and the workplace (ABS 2009). Estimates of the financial and social impact on individual well-being dictate that organizational researchers prioritize mental health in the workplace and find ways to better support employees. Based on this, the current study aimed to evaluate the impact of a supervisor-focused mental health training intended to equip supervisors with the knowledge and skills to become advocates for their own mental health, as well as serve as a resource for employees facing mental health challenges at work. Supervisors from a financial services institution in Australia completed surveys pre-training (T1), immediately post-training (T2), and 1 month post-training (T3). Results supported an increase in supervisors’ perceived knowledge related to mental health and well-being in the workplace, as well as an increase in supervisor reports of both personally-targeted well-being behavior and employee-targeted supervisor well-being support from before to after participation in the training. Further, we found that participants’ domain specific well-being self-efficacy (i.e., personal well-being self-efficacy, supervisor-reported well-being support efficacy) was positively impacted by participation in the training and positively associated with self-reported well-being behavior and supervisor well-being support. Theoretical and practical implications of supervisor-focused mental health training are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Results of these analyses can be obtained by contacting the second author.

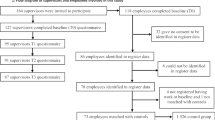

Attrition based on poor performance of the confidential identification code used to link participants across time points. Specifically, three items were used to create a de-identified participant code so responses could be matched across all three time points. Participants were asked to record their month of birth, the first letter of mother’s maiden name, and the second letter of their own last name. These data points were requested on each survey and combined into a single code. Duplicates were apparent due to a large number of missing responses to some of the code items and the high probability of matching combinations given the large sample size.

References

ABS. (2009). National survey of mental health and wellbeing. Cat. No. 4327.0. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4327.0.

Armitage, C., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior: a meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 471–499.

Arnold, K. A., Turner, N., Barling, J., Kelloway, E. K., & McKee, M. C. (2007). Transformational leadership and psychological well-being: the mediating role of meaningful work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12, 193–203.

Azjen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (Vol. 5, pp. 307–337). Greenwich: Information Age Publishing.

Blume, B., Ford, J. K., Baldwin, T., & Huang, J. (2010). Transfer of training: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Management, 36, 1065–1105.

Bogg, J., & Cooper, C. (1995). Job satisfaction, mental health, and occupational stress among senior civil servants. Human Relations, 48, 327–341.

Byrne, M. M., (2001). Structural equation modeling: Perspectives on the present and the future. Int. J. Test, 1, 327-334.

Byrne, A., Dionisi, A. M., Barling, J., Akers, A., & Robertson, J. (2014). The depleted leader: the influence of leaders’ diminished psychological resources on leadership behaviors. Leadership Quarterly, 25, 344–357.

Canadian Mental Health Association. (2017). Retrieved from https://alberta.cmha.ca/mental_health/statistics.

Casey, T. W., & Krauss, A. D. (2013). The role of effective error management practices in increasing miners’ safety performance. Safety Science, 60, 131–141.

Centers for Disease Control. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/basics.htm.

Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., & Noe, R. A. (2000). Toward an integrative theory of training motivation: a meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 678–707.

Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Czabała, C., Charzyńska, K., & Mroziak, B. (2011). Psychosocial interventions in workplace mental health promotion: an overview. Health Promotion International, 26, i70–i84.

Dimoff, J. K., Kelloway, E. K., & Burnstein, M. D. (2015). Mental health awareness training (MHAT): the development and evaluation of an intervention for workplace leaders. International Journal of Stress Management. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039479.

Griffiths, K. M., Christensen, H., Jorm, A. F., Evans, K., & Groves, C. (2004). Effect of web-based depression literacy and cognitive–behavioural therapy interventions on stigmatising attitudes to depression Randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 185, 342–349.

Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E. E., Anger, W. K., Bodner, T., & Zimmerman, K. L. (2011). Clarifying work–family intervention processes: the roles of work–family conflict and family-supportive supervisor behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 134–150.

Kelloway, E. K., & Barling, J. (2010). Leadership development as an intervention in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress, 24, 260–279.

Kelloway, E. K., Turner, N., Barling, J., & Loughlin, C. (2012). Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: the mediating role of employee trust in leadership. Work & Stress, 26, 39–55.

Kessler, R., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Chatterji, S., Lee, S., Ormel, J., Ustun, T., & Wang, P. (2009). The global burden of mental disorders: an update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys. Epidemiological Psychiatric Society, 18, 23–33.

Kirkpatrick, D. L. (1976). Evaluation of training. In R. L. Craig (Ed.), Training and development handbook: A guide to human resource development (2nd ed., pp. 18-1–18-27). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Kitchener, B. A., & Jorm, A. F. (2002). Mental health first aid training for the public: evaluation of effect on knowledge, attitudes and helping behavior. BMC Psychiatry, 2, 10–16.

Kitchener, B. A., & Jorm, A. F. (2004). Mental health first aid training in a workplace setting: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 2, 23–31.

Kraiger, K., Ford, J. K., & Salas, E. (1993). Application of cognitive, skill-based, and affective theories of learning outcomes to new methods of training evaluation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 311–328.

Krupa, T., Kirsh, B., Cockburn, L., & Gewurtz, R. (2009). Understanding the stigma of mental illness in employment. Work, 33, 413–425.

Kuoppala, J., Lamminpää, A., Liira, J., & Vainio, H. (2008). Leadership, job well-being, and health effects-a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 50, 904–915.

LaMontagne, A. D., Martin, A., Page, K. M., Revley, N. J., Noblet, A. J., Milner, A. J., Keegle, T., & Smith, P. M. (2014). Workplace mental health: Developing an integrated intervention approach. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 131–142.

Mental Health Foundation. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/statistics/mental-health-statistics-uk-and-worldwide.

Nielsen, K., Yarker, J., Brenner, S., Randall, R., & Borg, V. (2008). The importance of transformational leadership style for the well-being of employees working with older people. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 63, 465–475.

Nielsen, K., Randall, R., Holten, A., & González, E. R. (2010). Conducting organizational-level occupational health interventions: what works? Work & Stress, 24, 234–259.

Quinones, M. A., & Tonidandel, S. (2003). Conducting training evaluation. In J. E. Edwards, J. C. Scott, & N. S. Raju (Eds.), The human resources program evaluation handbook (pp. 225–243). London: Sage.

Robson, L. S., Shannon, H. S., Goldenhar, L. M., & Hale, A. R. (2001). Guide to evaluating the effectiveness of strategies for preventing work injuries: How to show whether a safety intervention really works. Cincinnati: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health DHHS Publication No. 2001-119.

Roche, M., Haar, J., & Luthans, F. (2014). The role of mindfulness and psychological capital on the well-being of leaders. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19, 476–489.

Ruona, W., Leimbach, M., Holton, E., & Bates, R. (2002). The relationship between learner utility reactions and predicted learning transfer among trainees. International Journal of Training and Development, 6, 218–228.

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2010). Ensuring positiveness of the scaled difference x-square test statistic. Psychometrika, 75, 243–248.

Skakon, J., Nielsen, K., Borg, V., & Guzman, J. (2010). Are leaders’ well-being, behaviours and style associated with the affective well-being of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work & Stress, 24, 107–139.

Stansfeld, S., & Candy, B. (2006). Psychosocial work environment and mental health—a meta-analytic review. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 32, 443–462.

Sy, T., Côté, S., & Saavedra, R. (2005). The contagious leader: impact of the leader's mood on the mood of group members, group affective tone, and group processes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 295–305.

Unsworth, K. L., & Mason, C. M. (2012). Help yourself: The mechanisms through which a self-leadership intervention influences strain. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 17, 235–245.

U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1999). Stress at work (NIOSH publication No. 99–101). Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/99-101/.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealth.gov/basics/myths-facts/index.html.

Van Dierendonck, D., Haynes, C., Borrill, C., & Stride, C. (2004). Leadership behavior and subordinate well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9, 165–175.

World Health Organization. (2003). Investing in mental health. Geneva

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

At the time of data collection, all authors were employed by a consulting company which was hired to design and implement the training. Currently, the first author holds a faculty position at a university and the second and third authors are employed at different organizations. None have any financial (or other) interest in this research, other than the hope that it will inform and contribute to scholarly knowledge.

The authors’ role in the consulting company was on the Research Team (responsible for the design and implementation of the training evaluation study) which is separate from the Client Team (the latter being the team involved in the actual delivery of the training).

The training evaluation study was conducted at no cost to the client organization. Further, the client organization gave consent for the research project to be conducted and was not involved in the design or analysis and interpretation of the evaluation study findings.

Appendix - Scale Items

Appendix - Scale Items

Training Reactions

Response scale: Strongly disagree, disagree, slightly disagree, slightly agree, agree, strongly agree

There were lots of practical examples of how to apply the knowledge and skills taught during this workshop.

The examples used in this workshop were relevant to what I experience at work.

The workshop was carried out in a professional manner.

There were lots of chances to interact with other people during this workshop.

I felt encouraged to be actively involved in this workshop.

I am eager to apply what I learned during this workshop to my job.

I learned something during the workshop that I can apply immediately in my job.

Perceived Well-Being Knowledge

Response scale: None, a little, some, quite a bit, a lot

Differences between a mental health issue and normal reactions to a difficulty in life.

Specific behaviors that suggest an employee is struggling to cope.

Specific behaviors that suggest an employee is performing at his/her optimum level.

The psychological components of resilience.

The steps required to carry out effective supporting conversations with employees.

Attitudes Toward Mental Health

Response scale: Strongly disagree, disagree, slightly disagree, slightly agree, agree, strongly agree

Mental illness is not a real medical condition.

It is best to avoid people with a mental illness so you don’t become ill yourself.

Mental illness is a sign of personal weakness.

People with a mental illness are dangerous.

Personal Well-Being Behavior

Response scale: Not at all, very little extent, little extent, some extent, great extent, very great extent

Manage my personal stress effectively.

Use personal strategies to increase my resilience.

Build trust and rapport with employees.

Supervisor Well-Being Support

Response scale: Not at all, very little extent, little extent, some extent, great extent, very great extent

Support employees who are distressed or upset.

Support employees who resist help from others.

Support employees who over-disclose personal information.

Personal Well-Being Self-efficacy

Response scale: Strongly disagree, disagree, slightly disagree, slightly agree, agree, strongly agree

When facing challenging situations, I am certain I can manage my personal wellbeing effectively.

In general, I think that I can maintain aspects of my wellbeing that are important to me.

Even when I feel stress at work, I can maintain my personal wellbeing quite well.

Supervisor Well-Being Support Efficacy

I am confident that I can carry out effective supporting conversations with employees who are experiencing a mental illness.

I can succeed at supporting employees who are experiencing difficulties with their mental health.

Even if employees are showing signs of mental illness, I can support them quite well.

Well-Being Communication

Response scale: Never, once, once a fortnight, once per week, 2–3 times per week, daily, many times each day

Over the past month, on average how often did you carry out informal conversations or ‘check-ins’ with your subordinates regarding their wellbeing?

Response scale: 0%, about 10%, about 30%, about 50%, about 70%, about 90%, 100%

Over the past month, with what percentage of subordinates have you carried out informal conversations or ‘check-ins’ regarding their wellbeing?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ellis, A.M., Casey, T.W. & Krauss, A.D. Setting the Foundation for Well-Being: Evaluation of a Supervisor-Focused Mental Health Training. Occup Health Sci 1, 67–88 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-017-0005-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-017-0005-1