Abstract

Outliers can seriously distort the results of statistical analyses and thus threaten the validity of structural equation models. As a remedy, this article introduces a robust variant of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS) and consistent Partial Least Squares (PLSc) called robust PLS and robust PLSc, respectively, which are robust against distortion caused by outliers. Consequently, robust PLS/PLSc allows to estimate structural models containing constructs modeled as composites and common factors even if empirical data are contaminated by outliers. A Monte Carlo simulation with various population models, sample sizes, and extents of outliers shows that robust PLS/PLSc can deal with outlier shares of up to \(50\%\) without distorting the estimates. The simulation also shows that robust PLS/PLSc should always be preferred over its traditional counterparts if the data contain outliers. To demonstrate the relevance for empirical research, robust PLSc is applied to two empirical examples drawn from the extant literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Structural equation modeling (SEM) is a popular psychometric method in social and behavioral sciences. Its ability to operationalize abstract concepts, estimate their relationships, and take into account measurement errors makes it a frequently applied tool for answering various types of research questions (Bollen 1989).

In general, two kinds of SEM estimators can be distinguished. On one hand, covariance-based estimators, such as the Maximum-Likelihood (Jöreskog 1970) and the Generalized Least Squares estimator (Browne 1974), minimize the discrepancy between the empirical and the model-implied indicator variance–covariance matrix to obtain the model parameter estimates. On the other hand, variance-based (VB) estimators, such as Generalized Structured Component Analysis (Hwang and Takane 2004) and Generalized Canonical Correlation Analysis (Kettenring 1971), first build proxies for the constructs as linear combinations of the indicators and, subsequently, estimate the model parameters.

Among VB estimators, Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS, Wold 1975) is one of the most often applied and thoroughly studied estimators. Its performance has been investigated for various population models, for normally and non-normally distributed data and in comparison to other estimators (Dijkstra and Henseler 2015a; Hair et al. 2017b; Sarstedt et al. 2016; Takane and Hwang 2018). Moreover, in empirical research, PLS has been used across a variety of fields, such as Marketing (Hair et al. 2012), Information Systems (Marcoulides and Saunders 2006), Finance (Avkiran et al. 2018), Family Business (Sarstedt et al. 2014), Human Resources (Ringle et al forthcoming), and Tourism (Müller et al. 2018).

Over the last several years, PLS has undergone numerous enhancements. In its current form, known as consistent Partial Least Squares (PLSc), it consistently estimates linear and non-linear structural models containing both composites and common factors (Dijkstra and Schermelleh-Engel 2014; Dijkstra and Henseler 2015b). Moreover, it can estimate models containing hierarchical constructs (Becker et al. 2012; Fassott et al. 2016; Van Riel et al. 2017), deal with ordinal categorical indicators (Schuberth et al. 2018b) and correlated measurement errors within a block of indicators (Rademaker et al. 2019), and can be employed as an estimator in Confirmatory Composite Analysis (Schuberth et al. 2018a). In addition to model estimation, PLS can be used in multigroup comparisons (Klesel et al. 2019; Sarstedt et al. 2011) and to reveal unobserved heterogeneity (Becker et al. 2013; Ringle et al. 2014). Furthermore, the fit of models estimated by PLS can be assessed in two ways: first, by measures of fit, such as the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR, Henseler et al. 2014), and second by bootstrap-based tests of the overall model fit (Dijkstra and Henseler 2015a). A recent overview of the methodological research on PLS is provided by Khan et al. (2019).

Despite the numerous enhancements of PLS and suggested guidelines (e.g., Henseler et al. 2016; Rigdon 2016; Benitez et al in press), handling outliers in the context of PLS has been widely neglected, although outliers are often encountered in empirical research (Filzmoser 2005). This is not without problems, since PLS and many of its enhancements such as PLSc use the Pearson correlation, which is known to be very sensitive to outliers (e.g., Boudt et al. 2012). Therefore, ignoring outliers is very likely to lead to distorted results and thus to questionable conclusions.

Outliers are observations that differ significantly from the rest of the data (Grubbs 1969). Two types of outliers can be distinguished (Niven and Deutsch 2012).Footnote 1 First, outliers can arise completely unsystematic and, therefore, not follow any structure. Second, outliers can arise systematically, e.g., from a different population than the rest of the observations.

To deal with outliers in empirical research, two approaches are commonly used. The first encompasses using robust estimators that are not or are only to a lesser extent distorted by outliers. The second entails identifying and manually removing outliers before the final estimation. The latter is often regarded as the inferior approach. First, it cannot be guaranteed that outliers are identified as such, because outliers can affect the results in a way that they may not be identified by visualization or statistics such as the Mahalanobis distance (Hubert et al. 2008). Second, even if outliers can be identified, removing them implies a potential loss of useful information (Gideon and Hollister 1987); in addition, for small data sets, reducing the effective number of observations reduces statistical power.

In light of this situation, the present paper contributes to the existing SEM literature by presenting robust versions of PLS. Specifically, we introduce robust Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (robust PLS) and robust consistent Partial Least Squares (robust PLSc), which combine the robust covariance estimator Minimum Covariance Determinant (MCD) with PLS and PLSc, respectively. Consequently, if robust PLS/PLSc are used to estimate structural equation models, outliers do not have to be removed manually.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 develops robust PLS/PLSc as a combination of PLS/PLSc with the robust MCD estimator of covariances. Sections 3 and 4 present the setup of our Monte Carlo simulation to assess the efficacy of robust PLS/PLSc and the corresponding results. Section 5 demonstrates the performance of robust PLS/PLSc by two empirical examples. Finally, the paper is concluded in Sect. 6 with a discussion of findings, conclusions, and an outlook on future research.

2 Developing robust partial least squares path modeling

Originally, PLS was developed by Wold (1975) to analyze high-dimensional data in a low-structure environment. PLS is capable of emulating several of Kettenring ’s (1971) approaches to Generalized Canonical Correlation Analysis (Tenenhaus et al. 2005). However, while, traditionally, it only consistently estimates structural models containing composites (Dijkstra 2017),Footnote 2 in its current form, known as PLSc, it is capable of consistently estimating structural models containing both composites and common factors (Dijkstra and Henseler 2015b). The following section presents PLS and its consistent version expressed in terms of the correlation matrix of the observed variables.

2.1 Partial least squares path modeling

Consider k standardized observed variables for J constructs, each of which belongs to one construct only. The n observations of the standardized observed variables belonging to the jth construct are stored in the data matrix \(\varvec{X}_j\) of dimension \((n \times k_j)\), such that \(\sum _{j = 1}^J k_j = k\). The empirical correlation matrix of these observed variables is denoted by \(\varvec{S}_{jj}\). To ensure the identification of the weights, they need to be normalized. This normalization is typically done by fixing the variance of each proxy to one, i.e., \(\hat{\varvec{w}}_j^{(0)'} \varvec{S}_{jj} \hat{\varvec{w}}_j^{(0)}=1\). Typically, unit weights are used as starting weights for the iterative PLS algorithm. To obtain the weights to build the proxies, the iterative PLS algorithm performs the following three steps in each iteration (l).

In the first step, outer proxies for the construct are built by the observed variables as follows:

The weights are scaled in each iteration by \(\left( \hat{\varvec{w}}_j^{(l)'} \varvec{S}_{jj} \hat{\varvec{w}}_j^{(l)}\right) ^{-\frac{1}{2}}\). Consequently, the proxy \(\hat{\varvec{\eta }}_j\) has zero mean and unit variance.

In the second step, inner proxies for the constructs are built by the outer proxies of the previous step:

There are three different ways of calculating the inner weight \(e_{jj'}^{(l)}\), all of which yield similar results (Noonan and Wold 1982): centroid, factorial, and the path weighting scheme. The factorial scheme calculates the inner weight \(e_{jj'}^{(l)}\) as follows:Footnote 3

The resulting inner proxy \(\tilde{\varvec{\eta }}_j\) is scaled to have unit variance again.

In the third step of each iteration, new outer weights \(\hat{\varvec{w}}_j^{(l+1)}\) are calculated.Footnote 4 Using Mode A, the new outer weights (correlation weights) are calculated as the scaled correlations of the inner proxy \(\tilde{\varvec{\eta }}_j^{(l)}\) and its corresponding observed variables \(\varvec{X}_j\):

Using Mode B, the new outer weights (regression weights) are the scaled estimates from a multiple regression of the inner proxy \(\tilde{\varvec{\eta }}_j^{(l)}\) on its corresponding observed variables:

The final weights are obtained when the new weights \(\hat{\varvec{w}}_j^{(l+1)}\) and the previous weights \(\hat{\varvec{w}}_j^{(l)}\) do not change significantly; otherwise, the algorithm starts again from Step 1, building outer proxies with the new weights. Subsequently, the final weight estimates \(\hat{\varvec{w}}_j\) are used to build the final proxies \(\hat{\varvec{\eta }}_j\):

Loading estimates are obtained as correlations of the final proxies and their observed variables. The path coefficients are estimated by Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) according to the structural model.

2.2 Consistent partial least squares

For models containing common factors, it is well known that the estimates are only consistent at large, i.e., the parameter estimates converge in probability only to their population values when the number of observations and the number of indicators tend to infinity (Wold 1982).

To overcome this shortcoming, Dijkstra and Henseler (2015b) developed PLSc. PLSc applies a correction for attenuation to consistently estimate factor loadings and path coefficients among common factors. The consistent factor loading estimates of indicators’ block j can be obtained as follows:

The correction factor \({\hat{c}}_j\) is obtained by the following equation:

To obtain consistent path coefficient estimates, the correlation estimates among the proxies need to be corrected for attenuation to consistently estimate the construct correlations:

Here, \({\hat{Q}}_j={\sqrt{\hat{c}_j\hat{\varvec{w}_j}'\hat{\varvec{w}}_j}}\) is the reliability estimate. In case of composites, typically, no correction for attenuation is applied, i.e., \({\hat{Q}}_j\) is set to 1 if the jth construct is modeled as a composite. Finally, based on the consistently estimated construct correlations, the path coefficients are estimated by OLS for recursive structural models and by two-stage least squares for non-recursive structural models.

2.3 Selecting a robust correlation

As illustrated, PLS and PLSc can both be expressed in terms of the correlation matrix of observed variables. For this purpose, typically, the Pearson correlation estimates are used. However, it is well known in the literature that the Pearson correlation is highly sensitive to outliers (e.g., Abdullah 1990). Hence, a single outlier can cause distorted correlation estimates and, therefore, distorted PLS/PLSc results. To overcome this shortcoming, we propose to replace the Pearson correlation by robust correlation estimates. Similar was already proposed for covariance-based estimators (e.g., Yuan and Bentler 1998a, b).

The existing literature provides a variety of correlation estimators that are robust against unsystematic outlier. Table 1 presents an overview of several robust correlation estimators and their asymptotic breakdown points. The Breakdown Point (BP) of an estimator is used to judge its robustness against unsystematic outliers and, thus, indicates the minimum share of outliers in a data set that yields a breakdown of the estimate, i.e., a distortion of the estimate caused by random/unsystematic outliers (Donoho and Huber 1983). Formally, the BP of an estimator T can be described as follows:

with T(X) being the estimate based on the sample X which is not contaminated by outliers and \(T(X^*)\) being the estimate based on the sample \(X^*\) which is contaminated by outliers of share \(\varepsilon\). Usually, an estimator with a higher asymptotic BP is preferred, as it is more robust, i.e., less prone to outlier’s distortion, than an estimator with a lower asymptotic BP. In addition to ranking various estimators by their asymptotic BPs, the estimators can be distinguished by their approach to obtaining the correlation estimate: using robust estimates in the Pearson correlation, using non-parametric correlation estimates, using regression-based correlations, and performing an iterative procedure that estimates the correlation matrix using the correlation of a subsample that satisfies a predefined condition.

To protect the Pearson correlation from being distorted by outliers, robust moment estimates can be used for the calculation of correlation. For instance, the mean and standard deviation can be replaced by, respectively, the median and the median absolute deviation (Falk 1998), or variances and covariances can be estimated based on a winsorized or trimmed data set (Gnanadesikan and Kettenring 1972). In addition to the Pearson correlation, robust non-parametric estimators such as Spearman’s, Kendall’s or the Gaussian rank correlation can be used (Boudt et al. 2012). Regression weights that indicate if an observation is regarded as an outlier can also be applied to weight the variances and covariances in the Pearson correlation (Abdullah 1990). Finally, iterative algorithms, such as the Minimum Covariance Determinant (MCD) and the Minimum Volume Ellipsoid (MVE) estimator, can be used to select a representative subsample unaffected by outliers for the calculation of the covariance and the standard deviations.

Among all considered approaches, the MCD estimator is a promising candidate for developing a robust version of PLS and PLSc. Although both MVE and MCD estimators have an asymptotic BP of 50%, which is the highest BP, an estimator can have and is much larger than the asymptotic BP of 0% of the Pearson correlation; in contrast to the MVE estimator, the MCD estimator is asymptotically normally distributed. Moreover, robust estimates based on the MCD are more precise (Butler et al. 1993; Gnanadesikan and Kettenring 1972) and a closed-form expression of the standard error exists (Rousseeuw 1985).

The MCD estimator estimates the variance–covariance matrix of a sample \(\varvec{X}\) of dimension \(n \times k\) as the variance–covariance matrix of a subsample of dimension \(h \times k\) with the smallest positive determinant. To identify this subsample, theoretically, the variance–covariance matrices of \(\left( {\begin{array}{c}n\\ h\end{array}}\right)\) different subsamples have to be estimated. The choice of h also determines the asymptotic BP of the MCD estimator. A maximum asymptotic BP of \(50\%\) is reached if \(h = (n + k + 1)/2\); otherwise, it will be smaller (Rousseeuw 1985).

The rationale behind the MCD estimator can be given by considering two random variables, each with n observations. While the Pearson correlation is based on all n observations to estimate the correlation, the MCD estimator calculates the variances and the covariance based on a subsample containing only h observations. The h observations are determined by the ellipse with the smallest area containing the h observations. Similarly, it is done in case of more than two variables; the subsample is determined by the ellipsoid with smallest volume containing the h observations. In general, the MCD estimator finds the confidence ellipsoid to a certain confidence level with the minimum volume to determine the variances and covariances.

To reduce the computational effort of calculating the MCD estimator, a fast algorithm has been developed that considers only a fraction of all potential subsamples (Rousseeuw and Driessen 1999). The fast MCD algorithm is an iterative procedure. In each iteration (l), the algorithm applies the following three steps to a subsample \(\varvec{H}^{(l)}\) of sample \(\varvec{X}\) consisting of h observations and k variables:

-

Calculate the Mahalanobis distance \(d^{(l)}_i\) for every observation \(\varvec{x}_i\) of \(\varvec{X}\):

$$\begin{aligned} d^{(l)}_i = \sqrt{\left( \varvec{x}_i - \bar{\varvec{x}}^{(l)}\right) '\varvec{S}^{(l)^{-1}}\left( \varvec{x}_i - \bar{\varvec{x}}^{(l)} \right) } \qquad i = 1, \ldots ,n, \end{aligned}$$(10)where \(\bar{\varvec{x}}^{(l)}\) is the sample mean, and \(\varvec{S}^{(l)}\) is the variance–covariance matrix of the subsample \(\varvec{H}^{(l)}\).

-

Create the new subsample \(\varvec{H}^{(l+1)}\) consisting of the observations corresponding to the h smallest distances.

-

Return \(\varvec{S}^{(l)}\) if the determinant of \(\varvec{S}^{(l+1)}\) equals the determinant of \(\varvec{S}^{(l)}\) or zero; otherwise, start from the beginning.

Since \(\text {det}(\varvec{S}^{(l)}) \ge \text {det}(\varvec{S}^{(l+1)})\) and \(\text {det}(\varvec{S}^{(1)}) \ge \text {det}(\varvec{S}^{(2)}) \ge \text {det}(\varvec{S}^{(3)}) \ldots\) is a non-negative sequence, the convergence of this procedure is guaranteed (Rousseeuw and Driessen 1999). Once the iterative procedure has converged, the procedure is repeated several times for different initial subsamples \(\varvec{H}^{(1)}\).

The initial subsample \(\varvec{H}^{(1)}\) is chosen as follows: first, a random subsample \(\varvec{H}^{(0)}\) of size \(k + 1\) of \(\varvec{X}\) is drawn. If \(\text {det}(\varvec{S}^{(0)}) = 0\), which is not desirable, further observations of \(\varvec{X}\) are added to \(\varvec{H}^{(0)}\) until \(\text {det}(\varvec{S}^{(0)}) > 0\), where \(\varvec{S}^{(0)} = \text {cov}(\varvec{H}^{(0)})\). Second, the initial distances \(d_i^{(0)}\) are calculated based on the mean vector and the variance–covariance matrix of \(\varvec{H}^{(0)}\), see Eq. 10. Finally, the initial subsample \(\varvec{H}^{(1)}\) consists of the observations belonging to the h smallest distances \(d_i^{(0)}\).

Figure 1 illustrates the difference between the Pearson correlation and the MCD estimator for a normally distributed data set with 300 observations, where 20% of observations are replaced by randomly generated outliers. The population correlation is set to 0.5. As shown, the estimate of the Pearson correlation is strongly distorted by the outliers, while the MCD correlation estimate is robust against outliers and thus very close to the population correlation.

2.4 Robust partial least squares path modeling and robust consistent partial least squares

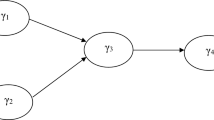

To deal with outliers in samples without manually removing them before the estimation, we propose modifications of PLS and PLSc called robust PLS and robust PLSc, respectively. In contrast to traditional PLS and its consistent version using the Pearson correlation, the proposed robust counterparts use the MCD correlation estimate as input to the PLS algorithm. As a consequence, the steps of the PLS algorithm and the principle of PLSc of correcting for attenuation remain unaffected. Figure 2 contrasts robust PLS and PLSc with their traditional counterparts.

As shown in Fig. 2, the only difference between robust PLS/PLSc and its traditional counterparts is the input of the estimation. The subsequent steps remain unaffected, and thus, robust PLS/PLSc can be easily implemented in most common software packages. However, due to the iterative algorithm, robust PLS/PLSc are more computationally intensive than their traditional counterparts that are based on the Pearson correlation.

3 Computational experiments using Monte Carlo simulation

The purpose of our Monte Carlo simulation is twofold: first, we examined the behavior of PLS and PLSc in case of unsystematic outlier. Although the reliance of traditional PLS/PLSc on Pearson correlation implies that outliers would be an issue, there is no empirical evidence so far of whether the results of traditional PLS/PLSc are affected by outliers and, if so, how strong the effect is. Second, we were interested in the efficacy of robust PLS/PLSc. More concretely, we investigated the convergence behavior, bias, and efficiency of robust PLS/PLSc, and compared them to their traditional counterparts.

The experimental design was full factorial and we varied the following experimental conditions:Footnote 5

-

concept operationalization (all constructs are specified either as composites or common factors),

-

sample size (\(n = 100\), 300, and 500), and

-

share of outliers (\(0\%\), \(5\%\), \(10\%\), \(20\%\), \(40\%\), and \(50\%\)).

3.1 Population models

To assess whether the type of construct, i.e., composite or common factor, affects the estimators’ performance, we considered two different population models.

3.1.1 Population model with three common factors

The first population model consists of three common factors and has the following structural model:

where \(\gamma _{21}=0.5\), \(\gamma _{31}=0.3\), and \(\gamma _{32}=0.0\). As Fig. 3 depicts, each block of three indicators loads on one factor with the following population loadings: 0.9, 0.8, and 0.7 for \(\eta _1\); 0.7, 0.7, and 0.7 for \(\eta _2\); and 0.8, 0.8, and 0.7 for \(\eta _3\).

All structural and measurement errors are mutually independent and the common factors are assumed to be independent of measurement errors. The indicators’ population correlation matrix is given by the following:

3.1.2 Population model with three composites

The second population model illustrated in Fig. 4 is similar to the first, but all common factors are replaced by composites. The composites are built as follows: \(\eta _1=\varvec{x}_1' \varvec{w}_{\varvec{x}_1}\) with \(\varvec{w}_{\varvec{x}_1}^\prime =(0.6, 0.4, 0.2)\); \(\eta _2=\varvec{x}_2^\prime \varvec{w}_{\varvec{x}_2}\) with \(\varvec{w}_{\varvec{x}_2}^\prime =(0.3, 0.5, 0.6)\); and \(\eta _3=\varvec{x}_3^\prime \varvec{w}_{\varvec{x}_3}\) with \(\varvec{w}_{\varvec{x}_3}^\prime =(0.4, 0.5, 0.5)\).

The indicators’ population correlation matrix has the following form:Footnote 6

3.2 Sample size

Although the asymptotic BP of MCD equals 50% (Rousseeuw 1985), its finite sample behavior in the context of the PLS algorithm needs to be examined. Therefore, we varied the sample size from 100 to 300 and 500 observations. For an increasing sample size, we expect almost no effect on the behavior of robust PLS and PLSc except that standard errors of their estimates decrease, i.e., the estimates become more accurate.

3.3 Outlier share in the data sets

To assess the robustness of our proposed estimator and to investigate the performance of PLS and PLSc in case of randomly distributed outliers, we varied the outlier share in the data sets from 0 to 50% with the intermediate levels of 5%, 10%, 20%, and 40%. We deliberately included a share of 0% to investigate whether robust PLS and PLSc perform comparably to their non-robust counterparts if outliers are absent. In this case, we would expect the traditional versions of PLS/PLSc to outperform our proposed modifications as they are based on the Pearson correlation which is known to be asymptotically efficient under normality (Anderson and Olkin 1985). As the share of outliers increases, we expect an increasing distortion in PLS and PLSc estimates. In contrast, due to the MCD estimator’s asymptotic BP of 50%, we expect robust PLS/PLSc to be hardly affected by outliers unless the asymptotic BP is reached.

3.4 Data generation and analysis

The simulation was carried out in the statistical programming environment R (R Development Core Team 2018). The data sets without outliers were drawn from the multivariate normal distribution using the function mvrnorm from the MASS package (Venables and Ripley 2002). The outliers were randomly drawn from the univariate continuous uniform distribution with the lower bound of − 10 and the upper bound of 10 using the function runif from the stats package (R Core Team 2018). To contaminate the data sets with outliers, the last observations of each data set were replaced by those. The MCD correlation estimates were calculated by the cov.rob function from the MASS package (Venables and Ripley 2002). PLS and PLSc as well as the estimates of our proposed robust versions were obtained using the function csem from the cSEM (Rademaker and Schuberth 2018) package.Footnote 7 The inner weights were obtained by the factorial scheme and the indicator weights in case common factors were calculated by Mode A and in case of composites by Mode B.

Although we considered the number of inadmissible solutions, the presented final results are based on 1000 admissible estimations per estimator for each condition, i.e., the inadmissible solutions were excluded and replaced by proper ones. To assess the performance of the different estimators, we consider the empirical smoothed density of the deviations of a parameter estimate from its population value. The range of the density represents the accuracy of an estimator, i.e., the fatter the tails are, the less precise the estimator. A narrow symmetric density with a mode at zero is desired, as it indicates an unbiased estimator with a small standard error.

4 Results

This section presents the results of our Monte Carlo simulation. Due to the large number of results, we report only a representative part of the results. In doing so, we only consider some of the model parameters, since the results are very similar for all parameters. The complete results are given in the Supplementary Material.Footnote 8

4.1 Model with three common factors

This section shows the result for the population model consisting of three common factors. Figure 5 shows the performance of robust PLSc for various sample sizes and outlier shares when all indicators are affected by unsystematic outlier. For clarity, only the two path coefficients \(\gamma _{21}\) and \(\gamma _{32}\) and the factor loading \(\lambda _{13}\) are considered. The results for the other parameters are similar.

As illustrated, the outlier share does not affect the parameter estimates of robust PLSc. On average, all estimates are close to their population value. Only when the proportion of outliers reaches 50%, the estimates will be clearly distorted. Moreover, the results are similar for larger sample sizes, except that the estimates become more accurate.

Figure 6 compares the estimates of robust and traditional PLSc. Since their results are very similar across various sample sizes, the results are only shown for a sample size of 300 observations. Moreover, as the results for robust PLSc are almost unaffected by the share of outliers, only the results for outlier shares of \(0\%\), \(5\%\), \(40\%\), and \(50\%\) are considered.

For samples without outliers, both approaches yield similar estimates, but PLSc produces slightly smaller standard errors. However, while robust PLSc estimates show almost no distortion until the asymptotic BP of 50% of the MCD estimator is reached, traditional PLSc estimates are already distorted for a small outlier share. This distortion increases if the outlier share is increased.

4.2 Population model with three composites

In the following, the results for the population model consisting of three composites are shown. To preserve clarity, only the results for the two path coefficients \(\gamma _{21}\) and \(\gamma _{32}\) and the weight \(w_{13}\) are reported. However, the results for the other parameters are similar. Figure 7 illustrates the performance of robust PLS.

Similar to the model with three common factors, the outlier share has almost no effect on the performance of robust PLS. Only when the share of outliers reaches 50%, the estimates are significantly distorted. On average, the robust estimates are very close to their population value; for an increasing sample size, the estimates becomes more precise.

Figure 8 compares the performance of robust PLS and that of its original version for various shares of outliers. Since the results are very similar across the considered sample sizes, the results for 300 observations are representative of the results for other sample sizes. Moreover, robust PLS behaves similarly for different outlier shares; therefore, only the results for outlier shares of 0%, 5%, 40%, and 50% are shown.

In the case of no outliers, the two estimators yield similar estimates, but PLS results in slightly smaller standard errors. While robust PLS shows a distortion only at the share of 50% of outliers, traditional PLS estimates are already distorted at the outlier share of 5%. As the outlier share increases, the PLS estimates become increasingly distorted, and in case of outlier share of 10% or above, the estimates even show a bimodal distribution.

4.3 Inadmissible solutions

Figures 9, and 10 illustrate the share of inadmissible solutions until 1000 proper solutions were reached for the models with three common factors and three composites. An inadmissible solution is defined as estimation for which the PLS algorithm does not converge, at least one standardized loading or one construct reliability of greater than 1 is produced, or for which the construct correlation matrix or the model-implied indicator’s correlation matrix is not positive semi-definite.

Figure 9 shows the shares of inadmissible solutions for the model containing three common factors. The largest number of inadmissible solutions is produced by PLSc based on the Pearson correlation.Footnote 9 In this case, neither the sample size nor the share of outliers significantly influences the share of inadmissible solutions. In contrast, robust PLSc produces fewer inadmissible solutions than does traditional PLSc in every condition except for samples without outliers. Although robust PLSc produces numerous inadmissible solutions in case of 100 observations, its results improve for samples of size 300 and 500. Robust PLSc only produces a large number of inadmissible solutions for 50% of outliers in the sample.

Figure 10 shows the share of inadmissible solutions for the model consisting of three composites. In general, the share of inadmissible solutions is lower than that for the model with three common factors. While almost no inadmissible solutions are produced by robust PLS, except in case of the outlier share of 50%, the share of inadmissible solutions of PLS is substantial when outliers are present and is almost unaffected by the sample size and the outlier share. However, in case of no outliers, almost no inadmissible solutions are produced by PLS.

5 Empirical examples

In this section, we illustrate the relevance of robust PLS/PLSc for empirical research. In doing so, we adopt the Corporate Reputation Model adapted from Hair et al. (2017a) and evaluate the influence of an incorrectly prepared data set on the estimation results. In addition, using the open- and closed-book data set from Mardia et al. (1979), we compare the results of robust PLSc to those obtained by the robust covariance-based estimator suggested by Yuan and Bentler (1998a).

5.1 Example: corporate reputation

The Corporate Reputation Model explains customer satisfaction (CUSA) and customer loyalty (CUSL) by corporate reputation. Corporate reputation is measured using the following two dimensions: (i) company’s competence (COMP) which represents the cognitive evaluation of the company, and (ii) company’s likeability (LIKE) which captures the affective judgments. Furthermore, the following four theoretical concepts predict the two dimensions of corporate reputation: (i) social responsibility (CSOR), (ii) quality of company’s products and customer orientation (QUAL), (iii) economic and managerial performance (PERF), and (iv) company’s attractiveness (ATTR).

The concepts CSOR, PERF, QUAL, and ATTR are modeled as composites, while the concepts LIKE, COMP, CUSA, and CUSL are modeled as common factors. In total, 31 observed variables are used for the concept’s operationalization. Each indicator is measured on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 to 7. The data set is publicly available and comprises 344 observations per indicator including 8 observations with missing values in at least one indicator coded as − 99 (SmartPLS 2019).

The conceptual model is illustrated in Fig. 11. To preserve clarity, we omit the measurement and structural errors as well as the correlations among the indicators. For detailed information about the underlying theory and the used questionnaire, it is referred to Hair et al. (2017a).

We estimate the model by robust and traditional PLS/PLSc based on the data set with and without missing values. Ignoring missing values, i.e., analyzing a data set containing missing values, represents a situation where a researcher does not inspect the data set for missing values a priori to the analysis. Consequently, the missing values which are coded as − 99 are treated as actual observations and can, therefore, be regarded as outliers, since they are obviously different from the rest of the observations. In case of no missing values, the missing values are assumed to be completely missing at random and are removed prior to the estimation. As a consequence, they do not pose a threat for the analysis.

To obtain consistent estimates, the model is estimated by PLSc, i.e., mode B is applied for composites and mode A with a correction for attenuation is employed for common factors. In addition, the factorial weighting scheme is used for inner weighting and statistical inferences are based on bootstrap percentile confidence intervals employing 999 bootstrap runs. Table 2 presents the path coefficient estimates and their significances.Footnote 10

Although PLSc and robust PLSc produce quite similar path coefficient estimates in case of the data set containing outliers, there are some noteworthy differences leading to contrary interpretations. While PLSc produces a non-significant effect with a negative sign of LIKE on CUSA \(({\hat{\beta }}=-0.151)\), employing robust PLSc results in a clear positive effect \(({\hat{\beta }}=0.454 , f^2=0.085)\). Moreover, the effect of LIKE on CUSL is non-significant under PLSc \(({\hat{\beta }}=0,031)\) indicating no effect; robust PLSc produces a moderate positive effect \(({\hat{\beta }}=0.507 , f^2=0.237)\). In case of no outliers, both estimators lead to similar results with no contradictions in the interpretation.

5.2 Example: open- and closed-book

This section compares the results of robust PLSc to the outlier-robust covariance-based (robust CB) estimator proposed by Yuan and Bentler (1998a). The latter employs M and S estimators to obtain robust estimates for the indicators’ variance–covariance matrix as input for the maximum-likelihood (ML) estimator. For the comparison, we replicate the empirical example in Yuan and Bentler (1998a) using the open- and closed-book data set from Mardia et al. (1979).

The data set contains test scores of 88 students on five examinations. The first two observable variables (score on Mechanics and Vectors) are linked to the first factor (closed-book exam) and the last three observable variables (score on Algebra, Analysis, and Statistics) depend on the second factor (open-book exam). For more details, see Tanaka et al. (1991).

Table 3 presents the estimated factor correlation \(({\hat{\rho }})\) for the different estimators.

The ML and robust CB estimates are taken from Yuan and Bentler (1998a). Since the M and S estimators depend on a weighting factor, the parameter estimates depend on that weighting factor, as well. As a consequence, the estimated factor correlation ranges from 0.856 to 0.896 for the robust CB estimator.

In general, the PLSc and the ML estimate and the robust PLSc and the robust ML estimates, respectively, are very similar, indicating that robust PLSc performs similarly as the robust CB estimator. Moreover, the difference between robust PLSc and its traditional counterpart is 0.062, while the difference between the ML estimator and its robust version ranges from 0.038 to 0.078. This is in line with Yuan and Bentler ’s conclusion that no extreme influential observations are present in the data set leading to similar results for robust and non-robust estimators.

6 Discussion

Outliers are a major threat to the validity of results of empirical analyses, with VB estimators being no exception. Identifying and removing outliers, if practiced at all, often entail a set of practical problems. Using methods that are robust against outliers is thus a preferable alternative.

Given the frequent occurrence of outliers in empirical research practice, it appears surprising that the behavior of traditional PLS and PLSc has not yet been studied under this circumstance. The first important insight from our simulation study is that neither traditional PLS nor PLSc is suitable for data sets containing outliers; both methods produce distorted estimates when outliers are present. Strikingly, even a small number of outliers can greatly distort the results of traditional PLS/PLSc. This observation underscores the need for a methodological advancement and highlights the relevance of addressing outliers in empirical research using PLS/PLSc.

As a solution, we introduced the robust PLS/PLSc estimators to deal with outliers without the need to manually remove them. The robust PLS/PLSc estimators use the MCD estimator as input to the PLS algorithm. This modular construction of the new method permits the PLS algorithm and the correction for attenuation applied in PLSc to remain untouched and thus allow for an straightforward implementation.

The computational experiment in the form of a Monte Carlo simulation showed that both robust PLS and robust PLSc can deal with large shares of unsystematic outlier and that their results are hardly affected by the model complexity and the number of indicators contaminated by outliers. The proposed method’s estimates are almost undistorted for the outlier share of up to 40%. The share of outliers would need to reach or exceed 50% of observations for the robust PLS/PLSc to break down. This finding is unsurprising, as this level matches the asymptotic BP of the employed MCD correlation estimator. Our findings are relatively stable with regard to outlier extent and model complexity. Even for systematic outliers, our Monte Carlo simulation provides first evidence that robust PLS/PLSc yield undistorted estimates. However, the BP is slightly lower compared to the situation with unsystematic outliers. This is not surprisingly, since the asymptotic Breakdown Point of an estimator is defined on basis of randomly generated contamination.

Although robust PLSc produces a large number of inadmissible solutions in case of small sample sizes, it still produces a smaller number of such solutions than does its non-robust counterpart. Furthermore, robust PLS produces only a notable number of inadmissible solutions for samples with the outlier share of 50%, while its traditional counterpart also produces higher numbers of inadmissible results for smaller outlier shares. In general, as the sample size increases, the number of inadmissible results decreases, and as expected, the estimates become more precise.

It is worth noting that if the data do not contain outliers, PLS and PLSc outperform their robust counterparts with regard to efficiency, i.e., by producing undistorted estimates with smaller standard errors. This finding is unsurprising, because the Pearson correlation equals the Maximum-Likelihood correlation estimate under normality, which is known to be asymptotically efficient (Anderson and Olkin 1985). Moreover, the MCD estimator is based only on a fraction of the original data set, while the Pearson correlation takes the whole data set into account.

The practical relevance of robust PLS/PLSc in empirical research is demonstrated by two empirical examples which additionally emphasize the problem of ignoring outliers. By means of the Corporate Reputation example, it is shown that not addressing outliers can affect the sign and magnitude of the estimates, and thus, also their statistical significance. This is particular problematic as researchers can draw wrong conclusions when generalizing their results. In addition, the open- and closed-book example shows that robust PLSc produces similar results as the robust covariance-based estimator suggested by Yuan and Bentler (1998a) providing initial evidence that both estimators perform similarly well. While the latter is likely to be more efficient in case of pure common factor models as it is based on a maximum-likelihood estimator, robust PLSc is likely to be advantageous in situations in which researchers face models containing both common factors and composites.

Although robust PLS and PLSc produce almost undistorted estimates when the outliers arise randomly and initial evidence is obtained that they are robust against systematic outliers, future research should investigate the behavior of these estimators in case of outliers that arise from a second population, e.g., from an underlying population that the researcher is unaware of or uninterested in. Moreover, since robust PLS and PLSc are outperformed by their traditional counterparts when no outliers are present, future research should develop statistical criteria and tests to decide whether the influence of outliers is such that the use of a robust method is recommendable. Furthermore, the large number of inadmissible solutions produced by PLSc if outliers are present, should be investigated. Even though an initial simulation has shown that the large number of inadmissible results is not a PLSc-specific problem, future research should examine whether a use of other correction factors (Dijkstra 2013) or an empirical Bayes approach (Dijkstra 2018) could improve its performance in presence of outliers. It may be fruitful to depart from robust PLS/PLSc in exploring all these new research directions.

Notes

It is noted that extant literature provides various taxonomy descriptions of outliers (e.g., Sarstedt and Mooi 2014).

It is noted that in the context of PLS, only Mode B consistently estimates composite models (Dijkstra 2017).

For more details on the other weighting schemes, see, e.g., Tenenhaus et al. (2005).

In the following, we only consider Mode A and Mode B. Mode C, which is a combination of Modes A and B, is not considered here (Dijkstra 1985).

In addition, three other conditions were examined. First, it was examined whether the model complexity had an influence on the results by including a model containing 5 constructs and 20 indicators. In doing so, all constructs were either specified as composites or as common factors. Second, we investigated the estimators’ performance in case that only a fraction of the observed variables, i.e., two indicators, are contaminated by outliers. Third, we examined the estimators’ performance in case of systematic outliers. In doing so, the outliers were drawn from the univariate continuous uniform distribution with lower bound 2 and upper bound 5 representing a situation where respondents always score high. Since the results are very similar to the results presented, these conditions are not explained in detail in the paper. For the results as well as further information on both conditions, we refer to the Supplementary Material.

All correlations were rounded to three decimal places.

Figures of the other investigated conditions as well as statistics on the other estimates are provided by the contact author upon request.

In addition, to examine whether the large number of inadmissible solutions is a PLSc-specific problem, we estimated the model with three common factors, 100 observations and 20% outlier by Maximum-Likelihood using the sem function of the lavaan package (Rosseel 2012). As a result, we observed a similar share of inadmissible solutions.

References

Abdullah MB (1990) On a robust correlation coefficient. Stat 39(4):455–460

Anderson TW, Olkin I (1985) Maximum-likelihood estimation of the parameters of a multivariate normal distribution. Linear Algebra Appl 70:147–171

Avkiran NK, Ringle CM, Low RKY (2018) Monitoring transmission of systemic risk: application of partial least squares structural equation modeling in financial stress testing. J Risk 20(5):83–115

Becker JM, Klein K, Wetzels M (2012) Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Plan 45(5–6):359–394

Becker JM, Rai A, Ringle CM, Völckner F (2013) Discovering unobserved heterogeneity in structural equation models to avert validity threats. MIS Q 37(3):665–694

Benitez J, Henseler J, Castillo A, Schuberth F (2019) How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory IS research. Information & Management

Bollen KA (1989) Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley, New York

Boudt K, Cornelissen J, Croux C (2012) The Gaussian rank correlation estimator: robustness properties. Stat Comput 22(2):471–483

Browne MW (1974) Generalized least squares estimators in the analysis of covariance structures. S Afr Stat J 8(1):1–24

Butler RW, Davies PL, Jhun M (1993) Asymptotics for the minimum covariance determinant estimator. Ann Stat 21(3):1385–1400

Dijkstra TK (1985) Latent variables in linear stochastic models: reflections on “maximum likelihood” and “partial least squares” methods, vol 1. Sociometric Research Foundation, Amsterdam

Dijkstra TK (2013) A note on how to make partial least squares consistent. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4547.5688

Dijkstra TK (2017) The perfect match between a model and a mode. In: Latan H, Noonan R (eds) Partial least squares path modeling. Springer, Cham, pp 55–80

Dijkstra TK (2018) A suggested quasi empirical Bayes approach for handling ’Heywood’-cases, very preliminary. https://doi.org/10.13140/rg.2.2.26006.86080

Dijkstra TK, Henseler J (2015a) Consistent and asymptotically normal PLS estimators for linear structural equations. Comput Stat Data Anal 81:10–23

Dijkstra TK, Henseler J (2015b) Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q 39(2):29–316

Dijkstra TK, Schermelleh-Engel K (2014) Consistent partial least squares for nonlinear structural equation models. Psychometrika 79(4):585–604

Donoho DL, Huber PJ (1983) The notion of breakdown point. In: Bickel P, Doksum K, Hodges JL Jr (eds) A festschrift for Erich L. Lehmann. Wadsworth International Group, Belmont, pp 157–184

Falk M (1998) A note on the comedian for elliptical distributions. J Multivar Anal 67(2):306–317

Fassott G, Henseler J, Coelho PS (2016) Testing moderating effects in PLS path models with composite variables. Ind Manag Data Syst 116(9):1887–1900

Filzmoser P (2005) Identification of multivariate outliers: a performance study. Austrian J Stat 34(2):127–138

Gideon RA, Hollister RA (1987) A rank correlation coefficient resistant to outliers. J Am Stat Assoc 82(398):656–666

Gnanadesikan R, Kettenring JR (1972) Robust estimates, residuals, and outlier detection with multiresponse data. Biometrics 28(1):81–124

Grubbs FE (1969) Procedures for detecting outlying observations in samples. Technometrics 11(1):1–21

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Mena JA (2012) An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J Acad Mark Sci 40(3):414–433

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2017a) A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications Ltd., Los Angeles

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Thiele KO (2017b) Mirror, mirror on the wall: a comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J Acad Mark Sci 45(5):616–632

Henseler J (2017) ADANCO 2.0.1. Composite Modeling GmbH & Co., Kleve

Henseler J, Dijkstra TK, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Diamantopoulos A, Straub DW, Ketchen DJ Jr, Hair JF, Hult GTM, Calantone RJ (2014) Common beliefs and reality about PLS: comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ Res Methods 17(2):182–209

Henseler J, Hubona G, Ray PA (2016) Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Ind Manag Data Syst 116(1):2–20

Hubert M, Rousseeuw PJ, Van Aelst S (2008) High-breakdown robust multivariate methods. Stat Sci 23(1):92–119

Hwang H, Takane Y (2004) Generalized structured component analysis. Psychometrika 69(1):81–99

Jöreskog KG (1970) A general method for analysis of covariance structures. Biometrika 57(2):239–251

Kettenring JR (1971) Canonical analysis of several sets of variables. Biometrika 58(3):433–451

Khan GF, Sarstedt M, Shiau WL, Hair JF, Ringle CM, Fritze M (2019) Methodological research on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an analysis based on social network approaches. Internet Res 29(3):407–429

Klesel M, Schuberth F, Henseler J, Niehaves B (2019) A test for multigroup comparison in partial least squares path modeling. Internet Res 29(3):464–477

Marcoulides GA, Saunders C (2006) Editor’s comments: PLS: a silver bullet? MIS Quarterly 30(2):iii–ix

Mardia KV, Kent JT, Bibby JM (1979) Multivariate analysis. Academic Presss, New York

Müller T, Schuberth F, Henseler J (2018) PLS path modeling—a confirmatory approach to study tourism technology and tourist behavior. J Hosp Tour Technol 9:249–266

Niven EB, Deutsch CV (2012) Calculating a robust correlation coefficient and quantifying its uncertainty. Comput Geosci 40:1–9

Noonan R, Wold H (1982) PLS path modeling with indirectly observed variables. In: Jöreskog KG, Wold H (eds) Systems under indirect observation: causality, structure, prediction part II. North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp 75–94

R Core Team (2018) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.R-project.org/

R Development Core Team (2018) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, http://www.R-project.org, ISBN 3-900051-07-0

Rademaker M, Schuberth F (2018) cSEM: Composite-Based Structural Equation Modeling. https://github.com/M-E-Rademaker/cSEM, R package version 0.0.0.9000

Rademaker M, Schuberth F, Dijkstra TK (2019) Measurement error correlation within blocks of indicators in consistent partial least squares: issues and remedies. Internet Res 29(3):448–463

Rigdon EE (2016) Choosing PLS path modeling as analytical method in european management research: a realist perspective. Eur Manag J 34(6):598–605

Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Schlittgen R (2014) Genetic algorithm segmentation in partial least squares structural equation modeling. OR Spectr 36(1):251–276

Ringle CM, Wende S, Becker JM (2015) SmartPLS 3. http://www.smartpls.com, Bönningstedt

Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Mitchell R, Gudergan SP (forthcoming) Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. Int J Hum Resour Manag

Rosseel Y (2012) lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw 48(2):1–36, http://www.jstatsoft.org/v48/i02/

Rousseeuw PJ (1985) Multivariate estimation with high breakdown point. In: Grossmann W, Pflug GC, Vincze I, Wertz W (eds) Mathematical statistics and applications. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht, pp 283–297

Rousseeuw PJ, Driessen KV (1999) A fast algorithm for the minimum covariance determinant estimator. Technometrics 41(3):212–223

Sarstedt M, Mooi E (2014) A concise guide to market research. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg

Sarstedt M, Henseler J, Ringle CM (2011) Multigroup analysis in partial least squares (pls) path modeling: alternative methods and empirical results. Adv Int Mark 22:195–218

Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Smith D, Reams R, Hair JF (2014) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): a useful tool for family business researchers. J Family Bus Strategy 5(1):105–115

Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Ringle CM, Thiele KO, Gudergan SP (2016) Estimation issue with PLS and CBSEM: where the bias lies!. J Bus Res 69(10):3998–4010

Schuberth F, Henseler J, Dijkstra TK (2018a) Confirmatory composite analysis. Front Psychol 9:2541

Schuberth F, Henseler J, Dijkstra TK (2018b) Partial least squares path modeling using ordinal categorical indicators. Qual Quant 52(1):9–35

SmartPLS (2019) Corporate repuation model. https://www.smartpls.com/documentation/sample-projects/corporate-reputation

Takane Y, Hwang H (2018) Comparisons among several consistent estimators of structural equation models. Behaviormetrika 45(1):157–188

Tanaka Y, Watadani S, Moon SH (1991) Influence in covariance structure analysis: with an application to confirmatory factor analysis. Commun Stat Theory Methods 20(12):3805–3821

Tenenhaus M, Vinzi VE, Chatelin YM, Lauro C (2005) PLS path modeling. Comput Stat Data Anal 48(1):159–205

Van Riel AC, Henseler J, Kemény I, Sasovova Z (2017) Estimating hierarchical constructs using consistent partial least squares: the case of second-order composites of common factors. Ind Manag Data Syst 117(3):459–477

Venables WN, Ripley BD (2002) Modern applied statistics with S, 4th edn. Springer, New York, http://www.stats.ox.ac.uk/pub/MASS4

Wold H (1975) Path models with latent variables: the NIPALS approach. In: Blalock HM (ed) Quantitative Sociology. Academic Press, New York, pp 307–357

Wold H (1982) Soft modeling: the basic design and some extensions. In: Jöreskog KG, Wold H (eds) Systems under indirect observation: causality, structure, prediction Part II. North-Holland, Amsterdam, pp 1–54

Yuan KH, Bentler PM (1998a) Robust mean and covariance structure analysis. Br J Math Stat Psychol 51(1):63–88

Yuan KH, Bentler PM (1998b) Structural equation modeling with robust covariances. Sociol Methodol 28(1):363–396

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Heungsun Hwang.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jörg Henseler acknowledges a financial interest in ADANCO and its distributor, Composite Modeling.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Empirical example

See Table 4.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Schamberger, T., Schuberth, F., Henseler, J. et al. Robust partial least squares path modeling. Behaviormetrika 47, 307–334 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41237-019-00088-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41237-019-00088-2