Abstract

This study investigates the impact of X on political discourse and hate speech in Finland, focusing on Muslim and LGBTQ+ communities from 2018 to 2023. During this period, these groups have experienced increased hate speech and a concerning surge in hate crimes. Utilizing network analysis methods, we identified online communities and examined the interactions between Finnish MPs and these communities. Our investigation centered on uncovering the emergence of networks propagating hate speech, assessing the involvement of political figures, and exploring the formation dynamics of digital communities. Employing agenda-setting theory and methodologies including text classification, topic modeling, network analysis, and correspondence analysis, the research uncovers varied communication patterns in retweet and mention networks. Retweet networks tend to be more fragmented and smaller, with participation primarily from far-right Finns Party MPs, whereas mention networks exhibit wider political representation, including members from all parties. Findings highlight the Finns Party MPs' significant role in fostering divisive, emotionally charged communications within politically segregated retweet communities, contrasting with their broader engagement in mention networks. The study underscores the necessity for cross-party efforts to combat hate speech, promote inclusive dialogue, and mitigate political polarization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the rapidly evolving landscape of digital communication, social media platforms, especially X (ex-Twitter), have emerged as pivotal arenas for political discourse [1]. This transformation has profound implications for public dialogue, policymaking, and the dynamics of social interaction [2, 3]. In Finland, as in many other nations, X has become not just a tool for communication, but a significant influencer in affecting political agendas and public opinion [4].

Previous studies have highlighted the platform's role in disseminating political information [5], mobilizing support [6], and framing political issues for the Finnish political context [7]. However, alongside its role in enriching democratic discourse, X has also been identified as a breeding ground for hate speech, particularly targeting marginalized communities such as Muslims and LGBTQ+ individuals [8].

Our study delves into this dichotomy, examining the dual role of X in facilitating political engagement while also serving as a conduit for hate speech. We focus on a comprehensive dataset collected from 2018 to 2023, encompassing a wide spectrum of interactions and narratives on Finnish X. This dataset is unique in its inclusion of tweets targeting Muslims and LGBTQ+ people, providing a broad context for understanding the nature and impact of hate speech in the digital public sphere [9, 10].

Additionally, this research incorporates an analysis of the X accounts of all Finnish parliament members. This aspect is critical in understanding the political dimensions of digital discourse in Finland [11], which emphasizes the growing influence of political actors on social media in shaping public opinion and policy debates [12].

Our study aims to offer a nuanced exploration of how X, as a digital platform, contributes to the proliferation of political discourse and hate speech. By examining the interactions and narratives surrounding Finnish parliament members and the targeted communities, we seek to uncover the patterns and themes that define the digital political landscape in Finland [1].

In doing so, this research not only contributes to the broader understanding of social media's impact on political communication [13] but also offers insights into the specific context of Finland, a nation with its unique political and social dynamics [4]. This study, therefore, stands at the intersection of digital media studies, political communication, and social policy, offering valuable perspectives for academics, policymakers, and practitioners alike [14].

More specifically, this research is guided by the following key questions: (a) How have hate speech networks emerged on X, and what are the notable differences between retweet and mention networks? (b) To what extent are politicians involved in these discussions, and is there a variation in involvement across different political parties? Finally, what types of digital communities have formed around these discourses, which hate speech themes have they prioritized, and what roles or statuses do politicians hold within these communities?

2 Agenda-setting theory in the digital age

Agenda-setting theory (AST), as initially conceptualized by McCombs and Shaw [15], posits that the media play a critical role in shaping public discourse by determining the salience of issues in the public mind. The media's influence lies not in persuading the audience what to think, but in dictating what topics are to be thought about (McCombs & Shaw, 1972). In the digital era, this theory takes on new dimensions with social media platforms, including X, which blend the roles of information creators and consumers [16].

X’s unique structure, characterized by brevity and immediacy, has reinvented the ways in which information is disseminated and agendas are set [5]. Politicians utilize X to bypass traditional media filters, directly reaching and influencing the public [16]. The rapid dissemination and feedback mechanisms intrinsic to X amplify the agenda-setting capacity of political actors, enabling them to shape public discourse in real time [17].

Nonetheless, the dynamics of interaction between political groups and the public take on a distinct form within the realm of social media communication. On X, the intricate transformation of agenda-setting is further nuanced by the emergence of echo chambers [18], which significantly influence the trajectory of political polarization.

The phenomenon of echo chambers on X, where users predominantly encounter views that reinforce their own, exacerbates the effects of agenda-setting [19]. Such environments contribute to political polarization, as divergent groups become increasingly insular [20]. This segmentation of the public sphere significantly influences the nature of political discourse and the efficacy of agenda-setting strategies on X [21].

Furthermore, the advent of social media has notably augmented public participation in the agenda-setting process, empowering users to actively influence and shape the discourse. Contrary to traditional media, agenda-setting on X involves a reciprocal relationship between political actors and the public. The public is not merely a passive recipient but an active participant, with the capacity to influence and modify the agenda through mechanisms of engagement such as retweets, likes, and replies [22]. This two-way interaction offers a more nuanced understanding of agenda-setting dynamics in the digital realm [23].

We have employed AST as our conceptual framework to systematically analyze the dissemination of hate speech on X, providing insights into how certain actors use divisive rhetoric to influence public discourse [24]. The analysis of content, frequency, and public engagement with hate speech tweets reveals the priorities and strategies of political groups in shaping public perception [25].

Moreover, understanding the agenda-setting role of X in the context of hate speech is crucial for comprehending the broader implications for democratic discourse and public policy. It sheds light on how digital platforms contribute to the shaping of societal norms and values, and the potential need for regulatory interventions [26].

In this study, we employed a comprehensive suite of methods—text classification, topic modeling, network analysis, and correspondence analysis. These approaches synergistically facilitated our analysis of the data, aligning seamlessly with the AST framework. Text classification in our study refers to the application of Natural Language Processing (NLP) to systematically categorize tweets from our dataset [27]. This methodology, supplemented by qualitative analysis, enables us to identify patterns and trends in the discourse on X by focusing on threads rather than solely on keywords. This comprehensive approach is essential for understanding the dynamics of hate speech, as it merges qualitative and quantitative analyses to provide a more thorough insight.

On the other hand, by identifying distinct thematic categories with the topic analysis, these results highlight that the dominant hate speech themes represent the agendas set by various political groups and actors on X. This aligns with McCombs and Shaw’s (1972) proposition that media, including new forms like social media, play a crucial role in shaping the salience of issues.

The community detection outcomes reveal how political groups and their followers create echo chambers, a phenomenon significant in the digital agenda-setting process [20]. To better understand the influence of social media on the spread of hate speech, it is essential to recognize the infrastructural and algorithmic impacts that guide users toward specific types of content [28]. The algorithms controlling content visibility on these platforms frequently establish echo chambers, which not only reinforce pre-existing biases but also risk radicalizing individuals by progressively exposing them to extremist material [29,30,31]. Such echo chambers contribute to polarized agenda-setting, amplifying particular hate speech narratives within certain groups [19]. This effect emphasizes the significant role that digital platforms play in forming social identities and influencing public discourse [32]. Finally, the correspondence analysis provides a nuanced understanding of how different political groups prioritize specific hate speech themes [33]. This aligns with the view of the dynamic nature of agenda-setting in the digital age, where public feedback, in this case through retweets and mentions, influences the prominence of specific topics [23].

3 Hate speech context in Finland

In the context of Finland, both the Muslim community and LGBTQ+ groups have been subject to hate speech and an alarming rise in hate crimes. Recent data highlights a significant surge in reported hate crime incidents targeting these communities. Specifically, in 2021, there was a noticeable rise in hate crimes against Muslims, with reported cases increasing by 44%, from 39 to 55. Subsequently, in 2022, there was a further 9% rise, totaling 60 cases [34, 35]. Likewise, hate crimes motivated by the victim's sexual orientation witnessed a substantial escalation, with a staggering 85% increase in 2021, as reflected in the jump from 68 to 126 reported cases. This trend persisted in 2022, with an 11% increase, resulting in 140 cases [34, 35].

In the contemporary digital landscape, where the pervasive influence of social media reigns supreme, an intriguing phenomenon takes center stage. The primary disseminators of hate speech predominantly comprise far-right political parties, their supporters, and anti-immigration activists [36, 37]. They leverage the reach of social media to propagate hate speech and radicalize individuals by exploiting concerns surrounding immigration and cultural identity [38]. In an attempt to mitigate the impact of their incendiary rhetoric, politicians often resort to blame deflection and justifications, a phenomenon termed covert hate speech, with the guise of protecting the nation [39,40,41].

Political actors employ these digital platforms to influence public discourse, perpetuating a distinct “us versus them” narrative [42, 43]. This approach not only fosters group cohesion within party politics but also marginalizes perceived outsiders [37]. Notably, far-right groups skillfully utilize these online channels to reinforce traditional gender norms to marginalize LGBTQ+ individuals or depict migrants as a threat to the country [7, 44].

Within the Finnish context, anti-immigrant and xenophobic rhetoric has firmly entrenched itself in public discourse, primarily promoted by far-right groups such as the Finns Party [37, 45]. This rhetoric frequently targets Muslims and portrays Islam as a threat to Finnish values and gender equality [46, 47]. Far-right groups often intertwine anti-immigrant arguments with gender politics, ostensibly advocating for the protection of women and LGBTQ+ individuals through their opposition to Muslim immigration. However, this is often a strategic maneuver aimed at controlling immigrant men rather than a sincere commitment to empower women [7].

Central themes within far-right hate speech center on safeguarding the nation and traditional values from perceived external threats like immigration and Islam [7, 47]. Their primary targets are Muslim immigrants, frequently depicted as a unified patriarchal group that poses a threat to Western liberal values and the principles of Islam. Despite receiving some nominal support from far-right groups, the LGBTQ+ community also endures unwarranted scrutiny [7, 47].

On the political spectrum, there is a clear division. More progressive entities champion causes like gender equality, LGBTQ+ rights, and multiculturalism, positioning themselves as countering forces against the divisive rhetoric of their far-right counterparts [48, 49]. Left-wing parties align themselves with feminist causes, although a subset of them resorts to populist rhetoric. In contrast, right-wing parties, such as the Finns Party, strongly oppose progressive gender policies, feminism, and multiculturalism [48, 49]. This digital landscape also stands at the epicenter of convergence between discussions involving Islam and conversations centered on sexual minorities [50].

4 Methods

4.1 Data

We utilized the R package academictwitteR [51] to gather tweets from January 1st, 2018, to January 1st, 2023. Guided by existing literature, our team identified potential instances of hate speech by searching for keywords previously established [52, 53]. Specifically, we assembled data related to LGBTQ+ content using 13 search terms, which encompassed 199 variations. Similarly, for content related to Muslims, we employed 14 keywords and their 221 respective variations (refer to Table 1 in the supplementary file). These terms accounted for various linguistic aspects of the Finnish language, including inflections, conjugations, and specific phrasings. We compiled a corpus of 320,045 tweets, originating from 30,360 distinct X profiles. The research received ethical clearance from the Ethics Committee at the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) due to its focus on individuals and their opinions.

To analyze the role of Finnish parliament members (MPs) in a network, we collected X handles for MPs serving in the last two terms. The first term spanned from 2019 to 2023, and the second from 2023 onwards. We intentionally included MPs serving consecutive terms for their continued political influence throughout our study period. The Finnish Parliament has 200 members; we identified 183 MPs' X handles in the first term and 186 in the second. Notably, 128 MPs have been in office since 2019. In total, our dataset comprises 271 unique X handles from nine parties across both terms.

4.2 Text classification

We adopted a framework for hate speech classification developed by Waseem and Hovy [54] and McIntosh [55], consisting of 11 categories. This framework provides a comprehensive set of criteria for identifying hate speech, which includes the use of slurs or attacks targeting minorities, attempts to silence or misrepresent minority groups through unfounded claims or strawman arguments, the promotion of violent ideologies or problematic hashtags, negative stereotyping, and the defense of xenophobic or sexist viewpoints. Additionally, it considers ambiguous cases where offensive screen names or content meeting other criteria are present. This multifaceted framework offers a robust approach to classify various manifestations of hate speech in different contexts.

To enhance its comprehensiveness, we expanded our study to address numerous intricate issues. We trained our experienced annotators on various facets of hate speech, which include, but are not limited to, the identification of target groups [56], deciphering humor [57], sarcasm, polysemy and interpreting emojis [58,59,60,61], discerning both implicit and explicit forms of hate speech [40, 41, 62], offensive language [54, 55], as well as hostility, criticism and counter-speech [63,64,65]. For simplicity, we classified tweets into three categories regarding hate speech: "hate speech" if any such content is identified, "no" if none is present, and "not sure" if the determination is unclear.

Sentiment analysis, which categorizes posts as negative, neutral, or positive, plays a critical role in identifying implicit hate speech. This analytical tool complements human judgment by detecting subtle negative expressions [58] that annotators may not explicitly classify as hate speech. However, they often perceive these expressions as having an overall negative tone toward targeted groups.

Overall text classification involves three consecutive stages: annotators initially identify target groups (Muslim, LGBTQ+, both, or neither), then evaluate the tone of the text based on sentiment, and finally label it according to hate speech classification labels.

For computational text classification, we randomly selected 4381 tweets, excluding retweets, short posts (less than 30 characters), and URL-only posts. Four native Finnish-speaking assistants classified tweets. We used Krippendorff's analysis to assess the annotator inter-rater reliability. Following 10 iterative training sessions, we achieved the highest IRR scores for target group classification (0.84), sentiment categories (0.67), and hate speech detection (0.64).Footnote 1

The lower agreement score partly results from annotators' unfamiliarity with Muslim culture and its contexts [66]. The complexity of accurately identifying hate speech is heightened when topics encompass Islamic terminologies, including beliefs, practices, Quranic verses, and Sharia laws, due to their culturally specific nature [67, 68]. Subjectivity in hate speech annotation can lead to discrepancies among annotators, a phenomenon that not only presents challenges but also offers valuable insights for understanding the nuanced interpretations of Islamic concepts, such as taqiyya, and cultural practices mistakenly perceived as religious beliefs [69, 70]. Through topic analysis, this investigation reveals the intricate dynamics between cultural interpretations and hate speech classification, highlighting the need for a nuanced approach in addressing hate speech targeting Muslim communities (see Table 6 in the Supplementary Materials for examples of complex tweets).

We used the BERT model, specifically the FinBERT model, due to its efficacy in NLP tasks [71, 72]. We fine-tuned it on training data, resulting in five models: target classification, sentiment classification (LGBTQ+ and Muslim), and hate speech classification (LGBTQ+ and Muslim). The target classification achieved an accuracy of 0.94, while LGBTQ+ models outperformed Muslim models in sentiment and hate speech classification (Table 2 in the supplementary file).

4.3 Topic analysis with BERTopic

Topic modeling, like BERTopic, identifies and analyzes topics within text collections. BERTopic, a Python library [73], clusters posts based on semantic similarity using BERT embeddings. Recent research [74] finds BERTopic superior to alternatives like Top2Vec, NMF, and LDA, offering distinct topics and novel insights from similar texts. In this study, we use BERTopic to extract topics from hate speech tweets. BERTopic follows customizable steps: extracting embeddings, dimension reduction, clustering, tokenizing, applying weighting, and fine-tuning representation (refer Table 3 in the supplementary file).

4.4 Network analysis and community detection

We opted for the Leiden algorithm, well suited for intricate, directed networks like those found in X activities, due to its proficiency in handling directionality, a crucial feature for analyzing retweets and mentions [75]. This choice is informed by its superior performance with directed data, in contrast to the Louvain and Newman algorithms, which are primarily designed for undirected networks and are more commonly used in this domain. Notably, when applied within the R programming language using the leidenAlg package, it facilitates a comprehensive examination of these networks, encompassing retweet and mention structures. This analysis gains particular significance when investigating the dissemination of hate speech. The directional Leiden analysis, which interprets retweets as endorsements and mentions as direct engagements, allows for the segmentation of the X community into distinct clusters [76].

4.5 Correspondence analysis

To understand the alignment between the topics of hate speech and the identified communities, correspondence analysis was applied. This technique is particularly useful in revealing the relationships between categorical data, in this case, topics and communities, offering insights into which political groups prioritize certain hate speech narratives [33].

Correspondence analysis (CA) serves as a data visualization technique suitable for cross-tabulated data, offering a two-dimensional graphical representation of counts or ratio-scale data (Greenacre, 2010). Much like principal component analysis does for quantitative data, CA enables the summarization and visualization of information in datasets with multiple interrelated variables [77]. Through the extraction of principal components, which are linear combinations of the original variables, CA simplifies the representation of crucial information from complex multivariate data.

For conducting inferential tests with CA, we employed the factorextra package in R. This algorithm generates various outputs, including eigenvalues, Chi-square test statistics, and plots. The biplot, a widely used visual tool, illustrates the overall data structure by plotting rows (categories) and columns (variables) as points in a lower-dimensional space. The horizontal and vertical axes of the biplot correspond to dimension 1 and 2, respectively, capturing the most substantial and second-most substantial sources of variation in the data. Furthermore, squared cosine (cos2) values offer insights into how effectively individual row/column points are represented by the axes in the factor map, indicating their quality in the multivariate analysis. The biplot visualization sheds light on the relationship between topics extracted from misinformation data and the communities within the existing network.

5 Findings

Our assembled corpus contained 263,103 tweets, originating from 24,185 unique Twitter profiles. This dataset included 55,411 individual tweets (those without mentions), 174,076 mentions (encompassing replies, comments, and mentions), and 33,616 retweets. Within this collection, a considerable majority of the posts, numbering 190,705 (72%), were directed at Muslims, whereas 72,398 posts (28%) focused on LGBTQ+ individuals. The text classification model categorized 63,067 of these tweets as hate speech, which constitutes 24% of the entire dataset. Of these hate speech tweets, a significant 87% (54,606 tweets) targeted Muslims, with the remaining 13% (8,461 tweets) aimed at LGBTQ+ individuals.

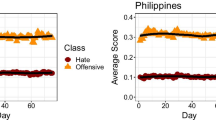

Figure 1 demonstrates a rising trend in hate speech volumes against both Muslims and LGBTQ+ individuals. Timeline analysis, however, uncovers differing trajectories: there is a steady, cumulative rise in hate speech concerning LGBTQ+ individuals. Conversely, the trend among Muslims shows a general increase but with notable variations. These variations often reflect event-driven discussions that provoke moral shocks [78]. Such shocks occur when people express strong emotions and moral condemnation in response to certain events or situations [79].

5.1 Topic modeling

Topic modeling of hate speech posts revealed 41 distinct topics targeting LGBTQ+ individuals and 32 topics targeting Muslims (for detailed information, refer to Tables 4 and 5 in the supplementary file). Notably, the higher diversity of topics for LGBTQ+ individuals, despite their smaller volume of posts, contrasts with the relatively fewer topics identified for Muslims, even with a larger volume of posts. Due to page constraints, we focus on the relationship between communities and topic distribution within the framework of CA. However, a more extensive discussion of these topics, situated within the Finnish political and social context, can be accessed in the authors' previous work [80] utilizing the same dataset.

5.2 Retweet network

By employing the directional Leiden community detection algorithm, we have identified a total of 188 communities. However, the majority of accounts are accumulated in a few larger communities. Specifically, only 10 communities have over 100 members and they contain more than 78% of all accounts in dataset (Fig. 2).

As illustrated in Fig. 3, when we apply a filter to isolate communities with membership sizes exceeding 140, we find that only seven Finns Party members remain within this subset. This observation suggests that Finns Party members tend to gravitate toward larger communities that share hate speech content. However, it is worth noting that their influence within the network is not particularly robust. The most active MP within these communities has only been retweeted six times.

Eight distinct communities were included into the CA. These communities exhibited a range of membership sizes, with the largest encompassing 335 individuals and the smallest, constituting the eighth group, comprising 135 members. For analytical robustness, only topics exceeding a 0.75 threshold in topic contribution scores were retained. This threshold ensures focus on the most relevant and significant topics within each community (For an overview of the topic distribution at the 0.70 threshold, see Figure 1 in the supplementary file).

A notable divergence in topical interests is observed among Communities 3, 4, 7, and partly 6, as depicted in Fig. 4. This divergence suggests these communities have distinct thematic focuses compared to the remaining groups.

5.2.1 LGBTQ+ related topics

In the analysis, only two topics related to LGBTQ+ issues exceeded the established threshold of 0.75 in topic contribution scores, highlighting their significant presence within the discourse. The first of these, topic L-09, which is mainly about “Homophobia, and Gender Stereotypes” using food preferences is apart from the other topics, it falls at the intersection of Communities 4 and 7.

The second, L-00, occupies a central position in the topic landscape. This topic primarily explores “Resistance to LGBTQ+ Visibility and Identity: Pride, Media, and Public Life,” indicating a focal concern with the public portrayal and societal acceptance of LGBTQ+ identities.

5.2.2 Criticism of Islam within religious context

Specifically, Community 3 displays a pronounced inclination toward discussions involving Muslim-related topics, predominantly featured in categories M-22, M-10, and M-27. These categories encapsulate specific thematic areas: M-10 delves into "Interpretations of Violence and Scriptural Justifications in Islam," M-22 explores "Islam and Slavery: Discussions on Historical and Contemporary Perspectives," and M-27 critically examines "Jutta Urpilainen and Islam: Criticisms and Accusations of Misrepresentation."Footnote 2 Such thematic concentration signals a unique discourse pattern within Community 3, underscoring the heterogeneity in community-based topic preferences.

5.2.3 Islam in European sociopolitical discourse

This section converges on a thematic nexus of integration, tensions, and comparative perspectives regarding Muslim immigrants within Finnish and broader European societies. Central to this discourse is M-00, which scrutinizes “Islam and Societal Integration in Finland,” shedding light on the complexities of cultural integration. Complementing this is M-01, which delves into “Discrimination and Xenophobia against Somalis,” thereby highlighting the ethnic-specific hate speech toward this group.

M-02 further explores the dynamic interplay between “Gender Equality and Religious Practices,” revealing the tensions between progressive social values and traditional religious norms. In a comparative vein, M-04 presents a juxtaposition of “Muslim Refugees with Ukrainian Refugees,” offering insights into the differential perceptions and treatments of diverse refugee populations.

Other salient topics include M-08, which investigates “Religious Tolerance and Conflict: Islam and Christianity in Europe,” providing a lens through which to view interfaith dynamics. Similarly, M-05 addresses “Religious Tensions and Anti-Semitism in the Context of Immigration,” underscoring the multifaceted nature of religious interactions within immigrant communities.

Further, M-12 discusses “Religious Extremism and Its Impact on French Society,” and M-17 examines “Turkey, EU, and Islam: Perspectives on Erdogan's Policies and European Relations,” each adding layers of complexity to the discourse on Islam's role in European public life. Meanwhile, M-03 takes a closer look at “Immigration Politics and Cultural Assimilation in Sweden and Finland,” thereby contributing a Nordic perspective to the conversation. M-28 rounds out the discussion by focusing on “Islamist Terrorism and Norway: Public Reactions and Concerns,” offering a case study on societal responses to extremist threats.

Contrastingly, certain topics such as M-19, “Iran and Women's Rights: Struggle Against Islamic Laws and Patriarchal Control,” occupy a more isolated position within this thematic map, with Community 4 being its nearest cluster. Similarly, M-16 and M-31, covering “Oulu and the Discussion on Sexual Assault Cases Involving Muslims” and “Pekka Haavisto and Islam: Public Opinions and Criticism” respectively, align more closely with Community 6. These topics, while peripheral to the main cluster, contribute critical perspectives on specific issues, thereby enriching the overarching discourse on Islam within European societies.

Collectively, these discussions encapsulate a comprehensive and nuanced dialogue on the intersection of Islamic identity with sociopolitical and cultural currents in Europe, painting a detailed portrait of the multifarious experiences and issues at the heart of this intersection.

5.2.4 Distribution of MPs

Upon examination of the participation patterns of MPs, it becomes apparent that those affiliated with the Finns Party are inclined to engage with larger communities. Within the scope of the eight communities, a total of eight MPs from the Finns Party have been discerned—allocating two to Community 1, two to Community 2, one each to Communities 5 and 6, and two to Community 7. The MPs from the Finns Party are predominantly clustered around the central axis of the biplot, reflecting a diverse engagement with multiple topics. This central placement suggests a broad interest from these MPs in topics of societal integration, cultural assimilation, and religious tensions.

5.3 Communities in mention networks

Interactions within the mention network manifest either as references to previously posted content or as direct engagements with other users, which include mentioning or tagging them while creating new content. The occurrence of hate speech mentions is context-dependent, as users may target specific accounts, invite others to join discussions, or involve oppositional parties. Mention activities highlight greater efforts in agenda-setting, particularly in introducing new topics to the discussions, engaging with related topics, and emphasizing their importance. This variability leads to mention networks encompassing all Finnish political parties.

Given the large volume of the mention activity, we focused on engagements that occurred more than once. Utilizing the Leiden algorithm, we identified 87 communities. Similar to retweet communities, a few clusters dominate the account distribution, with only 12 communities exceeding 100 members and the top 10 accounting for a remarkable 73% of all accounts (Fig. 5). To facilitate clearer visualization, we narrowed our analysis to communities with more than 150 members, resulting in eight larger clusters (Fig. 6). Within these predominant communities, we found 16 MPs from the Finns Party, 6 from the Centre Party, 5 each from the Greens and the Left Alliance, 1 from Liike Nyt, 9 from the National Coalition Party, 6 from the Social Democrats, and 3 from the Swedish Party. This distribution mirrors the retweet community pattern, where Finns Party MPs are predominantly associated with the larger groups.

Compared to the retweet network, Finns Party MPs are far more visible and active participants in the mention networks. The current party leader holds the top spot with a staggering 600 mentions, followed in the third row by the former party leader at 313 mentions. In stark contrast, other parties' most mentioned accounts pale in comparison: the Greens at 54 mentions, the Left Alliance at 134 mentions, the Centre Party at 40 mentions, the Social Democrats at 140 mentions, the Swedish Party at 41 mentions, the National Coalition Party at 113 mentions, and Liike Nyt with a mere 1 mention.

When comparing their influence within the mention network, an activistFootnote 3 tops the list with 1,014 mentions, followed by the public broadcasting company Yle Uutiset with 922. Other media organizations also feature prominently, with Helsinki Sanomat receiving 499 mentions, Iltalehti 358, and Ilta-Sanomat 345, all ranking in the top 10 mentioned accounts. Additionally, another civil activistFootnote 4 appears in the top 10, while the remaining most mentioned accounts belong to the Finns Party.

Our CA analysis focused on the top 10 communities, whose membership sizes spanned from 142 to 419. The results reveal that the majority of topics surpassing the 0.75 thresholds for topic contribution are clustered in proximity to one another, with the exception of four distinct outliers (For detailed information about the topic distribution at the 0.70 threshold, see Figure 2 in the supplementary file). Within this thematic aggregation, only two topics pertain to LGBTQ+ issues (L-00 and L-01), while the remainder predominantly focus on subjects related to Muslims (Fig. 7).

Out of the 10 communities analyzed, we identified 60 Finnish MPs actively observing/experiencing online hate speech. These MPs represented a broad spectrum of political ideologies, including the Centre Party (6 MPs), the Christian Democrats (2 MPs), the Finns Party (16 MPs), the Greens (6 MPs), the Left Alliance (5 MPs), Liike Nyt (1 MPs), the National Coalition Party (14 MPs), the Social Democrats (7 MPs), and the Swedish People's Party (3 MPs). This finding underscores the active participation of Finnish politicians from across the political spectrum in online political discourse.

5.3.1 LGBTQ+ related topics

The topic designated as L-00, which scrutinizes the “Resistance to LGBTQ+ Visibility and Identity: Pride, Media, and Public Life,” occupies a central position within the common clustering of communities in the CA biplot. This central location indicates that, with the exception of Communities 1 and 6, the remaining communities are generally closer to each other. This proximity suggests that they likely share more common topics in their discussions, including perspectives on LGBTQ+ issues. The near-universal centrality of L-00 within the biplot indicates a widespread engagement with the topic, implying that discussions surrounding LGBTQ+ visibility and identity are prevalent and possibly contentious across various community clusters. This suggests that, for most communities, the theme of LGBTQ+ resistance in public discourse is a salient issue that garners significant attention and conversational alignment. Here, “resistance” specifically refers to the denial of LGBTQ+ individuals' rights and presence in public spaces, highlighting a critical area of debate and discussion across these communities.

On the other hand, L-01 is situated peripherally relative to the others and primarily encompasses debates surrounding “Naming and Shaming in Political Contexts: Political Figures, Organizations, and Controversies.” This topic is most closely associated with Community 1, suggesting targeted engagement.

5.3.2 Criticism of Islam within religious context

The three topics in question coalesce around a critical examination of the foundations of Islam as a religious and belief system, each addressing a specific facet of this overarching theme. Topic M-10 ventures into the contentious “Interpretations of Violence and Scriptural Justifications in Islam,” probing the theological debates within Islamic discourse. Similarly, M-22 engages with “Islam and Slavery: Discussions on Historical and Contemporary Perspectives,” offering complex narratives surrounding the issue over time. Furthermore, M-30 navigates the discourse on “Jari Taponen and Jihadism: Public Perspectives on Law Enforcement Approach,” encapsulating public opinion and critique regarding counter-jihadism strategies and law enforcement methodologies.

The separation of these topics from the main cluster in the CA biplot and their strong association with Community 6 highlight their unique character and focused discourse. This alignment suggests a deeper engagement with critical perspectives on Islam within Community 6. Notably, Community 6 has the second-largest number of MPs (9), including 3 from Swedish, 2 from Social Democrats, 3 from National Coalition Party, and 1 from Centre Party. This community sits between two prominent thematic foci: the critical perspectives on Islam and the political and social dimensions of Muslim immigration.

5.3.3 Political and social dimensions of Muslim immigration

This cluster of topics primarily revolves around political and societal issues related to the Muslim presence in both Finland and the broader European context. This cluster includes topics such as M-31, “Pekka Haavisto and Islam: Public Opinions and Criticism,” which probes the public discourse and critique surrounding a prominent Finnish political figure and Islamic issues. Alongside this, M-17, “Turkey, EU, and Islam: Perspectives on Erdogan's Policies and European Relations” offers insight into the intricate dynamics between Turkish policies under Erdogan and their implications for EU relations.

Also central to this segment are M-19, “Iran and Women's Rights: Struggle Against Islamic Laws and Patriarchal Control,” which tackles the contentious issues of women's rights and the resistance against religious and patriarchal structures in Iran, and M-00, “Islam and Societal Integration in Finland,” which explores the integration of Islam into the societal fabric of Finland. Likewise, M-06, “Challenges and Perceptions of Muslim Immigration in Europe,” delves into the complexities and public perceptions of Muslim immigration on the continent, while M-08, “Religious Tolerance and Conflict: Islam and Christianity in Europe,'” examines the interplay of religious coexistence and contention between Islam and Christianity in the European milieu.

Geographically within the CA biplot, these topics occupy a region connecting Community 6, positioned at the upper end, with Communities 2, 3, and 8. This spatial distribution highlights a concentrated dialogue within these communities on the political and social dimensions of Muslim identity and its intersection with Finnish and European culture. This engagement with these topics underscores a critical examination of the multifaceted relationship between Muslim communities, political policies, and societal integration across Europe. Unsurprisingly, Communities 2 and 6 are the most active politically, given their focus on the political and social dimensions of Muslim immigration discussions. This is reflected in the fact that Community 2 has the largest number of MPs (12), including 5 from the Finns Party, 3 from the Left Alliance, 3 from the National Coalition Party, and 1 from Social Democrats. Similarly, Community 3 has 3 MPs from the Finns Party and one from Liike Nyt.

5.3.4 Comparative and practical aspect of Muslim immigrants

The final thematic cluster in the CA coalesces around practical considerations of Muslim immigration, cross-cultural interactions, and the varied responses of European societies to these phenomena. Central to this segment is M-03, “Immigration Politics and Cultural Assimilation in Sweden and Finland,” which scrutinizes the policies and societal pressures influencing the cultural integration of immigrants in these Nordic countries.

Adjacent to this is, topic M-21, “Central and Eastern European Countries and EU: Debates on Immigration, Multiculturalism, and Islam,” which encapsulates the contentious debates surrounding immigration and the place of Islam within the multicultural tapestry of the European Union, particularly focusing on the Central and Eastern European perspective.

Topic M-24, “Islam, the Left, and the Far-Right: Polarizing Views on Ideological Alliances and Threat Perceptions,” presents an exploration of the complex and often polarized ideological views on Islam, spanning the political spectrum from the Left to the Far-Right. Similarly, M-05, “Religious Tensions and Anti-Semitism in the Context of Immigration,” investigates the intersection of religious diversity and the resurgence of anti-semitic sentiment within the context of immigration.

Further topics such as M-07, “Discrimination and Violence Against Sexual Minorities in Religious Contexts,” delve into the specific challenges faced by sexual minorities, particularly within religiously conservative environments. Topic M-14, “Finns Party and Immigration: Discussion on Nationalism, Islam, and Women's Rights,” critically examines the discourse on nationalism and its interrelation with Islam and gender issues, as propagated by the Finns Party.

Additionally, M-04, “Comparison of Muslim Refugees with Ukrainian Refugees,” draws a comparative line between different refugee groups, highlighting differential treatments and perceptions. Lastly, M-01, “Discrimination and Xenophobia against Somalis,” addresses the specific experiences of Somali immigrants, marked by xenophobia and discrimination.

Collectively, these topics aggregate around more tangible aspects of the Muslim immigration experience, including national practices, the comparative analysis of immigrant groups, and the social and political responses that these groups elicit within European countries. This cluster reflects a broad and multifaceted discourse that is central to understanding contemporary immigration dynamics and the evolving cultural landscape of Europe.

Between the overarching thematic dimensions described above, Community 5 emerges as a pivotal entity, functioning as a bridge between these discussions. This intermediary positioning of Community 5 suggests its unique role in navigating both the theoretical aspects of Muslim integration and the more tangible, policy-oriented discussions, in topics such as M-05, M-07, and M-17. In terms of parliamentary engagement, there is a distinct pattern within Community 5. The Members of Parliament (MPs) from the Finns Party are notably active, with five representatives participating in the dialogue. Additionally, one MP from the Centre Party is present, which indicates that this community represents more likely right-wing perspectives.

6 Discussion

In the retweet networks we studied, exclusive participation of the Finns Party members was evident. In contrast, the mention networks displayed a broader political representation, encompassing members from all parties. A notable trend in the data was the heightened presence of far-right and other right-wing party members, with the Greens being the primary target among the opposition parties, along with more general category of “tolerant” people [50].

Analyzing the content of these mention networks reveals a specific pattern: liberal parties, particularly those advocating for immigration and LGBTQ+ rights, frequently became targets of hate speech. Similar dynamics have been identified in previous qualitative studies and in different platforms as well [81, 82]. Interestingly, the discussions analyzed here often involved members of far-right parties, who were actively engaged in initiating or contributing to the dialogues. A common strategy in these mention networks was to tag multiple accounts within a single post, aiming to disseminate the message widely and rapidly.

These observations suggest that while hate speech pervades mention networks across the political spectrum, direct engagement in its spread, notably through retweet networks, is largely confined to a subset of far-right party members [83]. Importantly, these exchanges are not restricted to obscure forums but occur on highly visible, public platforms, involving a wide range of political actors. Differing patterns between trends in hate speech targeting Muslims and LGTBQ+ people, showing the former trendline proceeding with notable peaks, indicate a more reactive approach toward the former, whereas the latter seemingly follows a certain lower baseline, although also continuously growing.

The growth is interesting in the light of the relatively low level of migration from the Muslim countries to Finland during the period of this study especially when compared to the so-called migration crisis in 2015–2016. The continuously growing level of hate speech suggests that Muslim migration is used increasingly as an issue independent of the reality of migration and to produce a crisis mentality. This most likely also reflects the changes in the Finns Party positions toward a more radical direction [84], considering the central position of current and previous party leaders in the mention networks. The crises are also a part of the strategy of the populist parties, for which the “existence and continued success is reliant on the continued propagation and perpetuation of crisis” [85]. Therefore, keeping the issue on the agenda is highly relevant for them. Furthermore, as also indicated by our topic analysis which suggested among others the resurgence of anti-semitism in the context of immigration, marginalizing rhetoric targeting explicitly one group may nevertheless lead to marginalization of other minorities as well [86, 87].

Previous studies also suggest that especially anti-immigration rhetoric is often followed by external events [78] and is in this sense reactive. Reactive nature on the other hand does not exclude its own agency but may be seen in the light of how far-right actors also challenge the traditional media and their gatekeeper power. Our topic analysis indicates they want actively to provide an alternative framing to the news shared and discussed in the mainstream media. This may additionally reflect the differing salience of these issues on the agenda of the far-right in Finland.

Certain themes are prioritized by the far-right parties when those fit their agenda. Migration is the key mobilizing element in the rhetoric of the populist radical right, also among the voters of the Finns Party [84], whereas anti-LGTBQ+ hate speech is perhaps more advocated on the individual level and by actors with no party affiliation, as suggested by the more scattered nature of the topics in this category. Only two LGTBQ+ topics in mention and retweet networks rose above the established threshold in topic contribution scores. Along with agenda setting, this relates to the thesis of issue ownership. LGTBQ+ rights are discussed and supported actively also on the other edge of the political field, but critical immigration issues are often left to be dealt with by the far-right [88]. Furthermore, as some studies suggest and our topic analysis also indicates, this may reflect the attempts to include the LGTBQ+ people in the nationalist project against other minority groups, especially the Muslims [89]. Although our topic analysis suggests a shared perspective on the LGTBQ+ issues in several communities, this may therefore to some extent be illusory.

Retweet communities, confirming the results of a recent study [90], tend to be more politically segregated. Retweets, amplifying the message, also typically signal endorsement and positive engagement with the topic [91]. In our study, notable is the total absence of other parties than the Finns Party in the larger retweet communities which include hate speech. This suggests, if not direct engagement, at least passive acceptance of the hate-filled parlances within a certain subset of the party members, although the number of MPs in these communities was rather low.

Populist communication logic prefers such issues that are more emotional, thereby stirring conflict and heated discussion [92]. Engagement in emotional, often hate-filled discussions can be detected also in the mention networks, in which Finns Party leaders show very visibly. On the other hand, as previous studies also show, they were not only engaged in hate speech networks but also received a lot of hate speech themselves, as did members of the other parties with high social media activity [57, 93, 94]. Descriptions of the topics in this study nevertheless indicate the Greens and left-wing MPs are more often targeted, and certain named left-wing or Greens Party politicians even come up as specific topics in our analysis.

The inclusion of the members of the other parties in the mention communities, despite their potentially dialogical nature, may additionally indicate increasingly polarized attitudes, especially if done for the purpose of targeting. Emotional pro et contra argumentation, however, also in itself may increase the polarization. For the dynamics of polarization, as previous studies suggest, both reactions and counter-reactions are highly relevant [93]. Drawing members of the other parties into the discussion may in this sense serve the agenda-setting by the far-right as the discussion is initially framed by them, drawing attention to the issues they have the ownership of, and which are high on their agenda.

Given this context, the dynamics of the hate speech networks, agenda-setting, and polarization, parliamentarians, as both observers and at times targets of such hate speech, are uniquely positioned to lead proactive measures. The fact that governments typically form multi-party coalitions underscores the potential for collaborative, cross-party initiatives. Such efforts could significantly enhance legislative and administrative strategies to combat hate speech, promoting a more respectful and inclusive public discourse.

7 Limitations

This study is subject to several important limitations that warrant caution in applying our findings. Initially, the reliance on X data introduces questions about its generalizability beyond the platform's user base. Although X granted considerable access to researchers, aiding in data collection during our research period, this accessibility has subsequently decreased. This reduction in access poses challenges for conducting similar future studies on X.

Additionally, our analysis, centered on retweets and mentions, does not illuminate individual tweeting behaviors. Further investigation is required, particularly regarding the activities of certain Finns Party members in retweet communities. Moreover, while our study sheds light on agenda-setting and framing within the X environment, its implications for the broader media ecosystem remain unexplored. This limitation suggests the need for additional research to understand the full impact of these dynamics beyond the confines of the platform.

8 Conclusion

This study investigates the influence of hate speech on political communication in Finland, with a focus on online communities, the engagements of Finnish MPs, and their impact on public discourse. It identifies a selective prioritization of issues within communities, noting variations in MPs' roles and stances across different topics and groups. Specifically, the research highlights the politically segregated nature of retweet communities and the distinctive participation of Finns Party MPs in promoting emotionally charged, conflict-driven communication. In contrast, MPs from all political parties are engaged in mention networks, with Finns Party MPs demonstrating more significant activity and impact.

The findings reveal a pronounced involvement of Finns Party leaders in fostering divisive communication within these networks, contributing to political segregation. This behavior suggests that the strategic agenda-setting and framing by hate speech communities could exacerbate polarization, emphasizing the critical need for parliamentarians to actively counteract hate speech and foster a more respectful, inclusive public dialogue.

Moreover, the study calls attention to the urgent requirement for cross-party efforts to mitigate hate speech, aiming to cultivate a more conducive atmosphere for democratic engagement.

Data availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly or third parties due to ethical and privacy reasons mandated by the Ethical Review Committee of THL.

Notes

A score of 0.8 or higher is considered excellent inter-rater reliability, indicating strong agreement among the coders. A score between 0.67 and 0.8 is considered good inter-rater reliability, while a score between 0.5 and 0.67 is considered moderate. A score below 0.5 is considered poor and suggests that the coders have little agreement.

Jutta Urpilainen is a Finnish politician representing the SDP who acts currently as the European Commissioner for International Partnership. Her use of a black scarf during a visit to Abu Dhabi in 2022 caused a negative uproar especially among the far-right.

The mentioned activist belonging to the Kurdish minority in Finland presents liberal positions and is actively engaged in dialogue with far-right members.

Blogger and civil activist who is of Kurdish background and a secular Muslim, has often engaged in discussions heavily criticizing the allegedly positive attitudes left-wing politicians represent concerning radical Islam.

References

Bruns, A., Burgess, J.: Twitter hashtags from ad hoc to calculated publics. Presented at the (2015)

Dahlberg, L.: Rethinking the fragmentation of the cyberpublic: from consensus to contestation. New Media Soc. 9, 827–847 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444807081228

Freelon, D., Marwick, A., Kreiss, D.: False equivalencies: online activism from left to right. Science 369, 1197–1201 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb2428

Strandberg, K.: A social media revolution or just a case of history repeating itself? The use of social media in the 2011 Finnish parliamentary elections. New Media Soc. 15, 1329–1347 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812470612

Jungar, A.-C.: From the mainstream to the margin?: The radicalisation of the True Finns. In: Akkerman, T., de Lange, S.L., Rooduijn, M. (eds.) Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Into the Mainstream?, pp. 113–143. Routledge, New York (2016)

Enli, G.: Twitter as arena for the authentic outsider: exploring the social media campaigns of Trump and Clinton in the 2016 US presidential election. Eur. J. Commun. 32, 50–61 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323116682802

Lähdesmäki, T., Saresma, T.: Reframing gender equality in Finnish online discussion on immigration: populist articulations of religious minorities and marginalized sexualities. NORA Nord. J. Fem. Gender Res 22, 299–313 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1080/08038740.2014.953580

Titley, G., Lentin, A.: Islamophobia, race and the attack on antiracism: Gavan Titley and Alana Lentin in conversation. Fr. Cult. Stud. 32, 296–310 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/09571558211027062

Chakravarthi, B.R.: Detection of homophobia and transphobia in YouTube comments. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41060-023-00400-0

Gagliardone, I., Gal, D., Alves, T., Martinez, G.: Countering Online Hate Speech. UNESCO Publishing, Paris (2015)

Laaksonen, S.-M., Haapoja, J., Kinnunen, T., Nelimarkka, M., Pöyhtäri, R.: The datafication of hate: expectations and challenges in automated hate speech monitoring. Front. Big Data. 3, 3 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3389/fdata.2020.00003

Ausserhofer, J., Maireder, A.: National politics on Twitter: structures and topics of a networked public sphere. Inf. Commun. Soc. 16, 291–314 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.756050

Stromer-Galley, J.: Presidential Campaigning in the Internet Age. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

Vaccari, C., Valeriani, A.: Party campaigners or citizen campaigners? How social media deepen and broaden party-related engagement. Int. J. Press/Polit. 21, 294–312 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216642152

McCombs, M.E., Shaw, D.L.: The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin. Q. 36, 176–187 (1972)

Parmelee, J.H., Bichard, S.L.: Politics and the Twitter Revolution: How Tweets Influence the Relationship Between Political Leaders and the Public. Lexington Books, Lanham (2013)

Conway, B.A., Kenski, K., Wang, D.: The rise of Twitter in the political campaign: searching for intermedia agenda-setting effects in the presidential primary. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 20, 363–380 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12124

Garimella, K., De Francisci Morales, G., Gionis, A., Mathioudakis, M.: Political discourse on social media: echo chambers, gatekeepers, and the price of bipartisanship. In: Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference on World Wide Web—WWW ’18. pp. 913–922. ACM Press, Lyon (2018)

France, A.: Cass R. Sunstein: #Republic: divided democracy in the age of social media. Ethic Theory Moral Pract. 20, 1091–1093 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-017-9839-5

Garrett, R.K.: Echo chambers online?: Politically motivated selective exposure among Internet news users. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 14, 265–285 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01440.x

Stroud, N.J.: Polarization and partisan selective exposure. J. Commun. 60, 556–576 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01497.x

Chadwick, A.: The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2013)

Russell Neuman, W., Guggenheim, L., Mo Jang, S., Bae, S.Y.: The dynamics of public attention: agenda-setting theory meets big data: dynamics of public attention. J. Commun. 64, 193–214 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12088

Awan, I.: Cyber-extremism: Isis and the power of social media. Society 54, 138–149 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-017-0114-0

Wojcieszak, M., Garrett, R.K.: Social identity, selective exposure, and affective polarization: how priming national identity shapes attitudes toward immigrants via news selection. Hum. Commun. Res. 44, 247–273 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqx010

Tucker, J., Guess, A., Barbera, P., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., Nyhan, B.: Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: a review of the scientific literature. SSRN J. (2018). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3144139

Galke, L., Diera, A., Lin, B.X., Khera, B., Meuser, T., Singhal, T., Karl, F., Scherp, A.: Are we really making much progress? Bag-of-words vs. sequence vs. graph vs. hierarchy for single- and multi-label text classification. http://arxiv.org/abs/2204.03954 (2023)

Stieglitz, S., Dang-Xuan, L.: Emotions and information diffusion in social media—sentiment of microblogs and sharing behavior. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 29, 217–248 (2013). https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222290408

Cinelli, M., De Francisci Morales, G., Galeazzi, A., Quattrociocchi, W., Starnini, M.: The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2023301118 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023301118

Zuiderveen Borgesius, F.J., Trilling, D., Möller, J., Bodó, B., De Vreese, C.H., Helberger, N.: Should we worry about filter bubbles? Internet Policy Rev. (2016). https://doi.org/10.14763/2016.1.401

Flaxman, S., Goel, S., Rao, J.M.: Filter bubbles, echo chambers, and online news consumption. PUBOPQ 80, 298–320 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw006

Baumann, F., Lorenz-Spreen, P., Sokolov, I.M., Starnini, M.: Modeling echo chambers and polarization dynamics in social networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 048301 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.048301

Greenacre, M.: Correspondence Analysis in Practice. Chapman and Hall, Boca Raton (2017)

Rauta, J.: Poliisin tietoon tullut viharikollisuus Suomessa 2021 [Hate crimes reported to the police in Finland in 2021]. Poliisiammattikorkeakoulu [Finnish Police Vocational College], Tampere (2022)

Rauta, J.: Poliisin tietoon tullut viharikollisuus Suomessa 2022 [Hate crimes reported to the police in Finland in 2022]. Poliisiammattikorkeakoulu [Finnish Police Vocational College], Tampere (2023)

Backlund, A., Jungar, A.-C.: Populist radical right party-voter policy representation in Western Europe. Representation 55, 393–413 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2019.1674911

Horsti, K.: Techno-cultural opportunities: the anti-immigration movement in the Finnish mediascape. Patterns Prejudice 49, 343–366 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2015.1074371

Hokka, J., Nelimarkka, M.: Affective economy of national-populist images: investigating national and transnational online networks through visual big data. New Media Soc. 22, 770–792 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819868686

Pettersson, K.: “Freedom of speech requires actions”: exploring the discourse of politicians convicted of hate-speech against Muslims. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 49, 938–952 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2577

Bhat, P., Klein, O.: Covert hate speech: white nationalists and dog whistle communication on Twitter. In: Bouvier, G., Rosenbaum, J.E. (eds.) Twitter, the public sphere, and the chaos of online deliberation, pp. 151–172. Springer, Cham (2020)

Baider, F.: Covert hate speech, conspiracy theory and anti-semitism: linguistic analysis versus legal judgement. Int. J. Semiot. Law 35, 2347–2371 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-022-09882-w

Allport, G.W.: The Nature of Prejudice. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Cambridge, MA (1954)

Van Dijk, T.A.: Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse Soc. 4, 249–283 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926593004002006

Keskinen, S.: Antifeminism and white identity politics: political antagonisms in radical right-wing populist and anti-immigration rhetoric in Finland. Nord. J. Migr. Res. 3, 225 (2013). https://doi.org/10.2478/njmr-2013-0015

Mäkinen, K.: Uneasy laughter: encountering the anti-immigration debate. Qual. Res. 16, 541–556 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794115598193

Hatakka, N., Niemi, M.K., Välimäki, M.: Confrontational yet submissive: calculated ambivalence and populist parties’ strategies of responding to racism accusations in the media. Discourse Soc. 28, 262–280 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926516687406

Saarinen, R., Koskinen, H.J.: Recognition, religious identity, and populism: lessons from Finland. In: Slotte, P., Gregersen, N.H., Årsheim, H. (eds.) Internationalization and Re-confessionalization, pp. 315–336. University Press of Southern Denmark, Denmark (2022)

Kantola, J., Lombardo, E.: Populism and feminist politics: the cases of Finland and Spain. Eur J Polit Res 58, 1108–1128 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12333

Nygård, M., Nyby, J.: Chapter 9: the role of ideas in parenting leaves: the case of gender equality and its politicization in Finland. Presented at the, Cheltenham, UK, December 9 (2022)

Jantunen, J.H., Kytölä, S.: Online discourses of ‘homosexuality’ and religion: the discussion relating to Islam in Finland. JLS 11, 31–56 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1075/jls.20011.jan

Barrie, C., Ho, J.C.: academictwitteR: an R package to access the Twitter Academic Research Product Track v2 API endpoint. J. Open Source Softw. 6, 3272 (2021). https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03272

Kettunen, L., Paukkeri, M.-S.: Utilisation of artificial intelligence in monitoring hate speech. Helsinki, Finland (2021)

Mäkinen, K.: Sanat ovat tekoja. Vihapuheen ja nettikiusaamisen vastaisten toimien tehostaminen [Words are actions. Enhancing measures against hate speech and cyberbullying]. Sisäministeriö [Ministry of the Interior], Helsinki, Finland (2019)

Waseem, Z., Hovy, D.: Hateful symbols or hateful people? Predictive features for hate speech detection on Twitter. In: Proceedings of the NAACL Student Research Workshop, pp. 88–93. Association for Computational Linguistics, San Diego, California (2016)

McIntosh, P.: White privilege: unpacking the invisible knapsack. In: Understanding Prejudice and Discrimination, pp. 191–196. McGraw-Hill Humanities (2003)

De Gibert, O., Perez, N., García-Pablos, A., Cuadros, M.: Hate speech dataset from a white supremacy forum. In: Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Abusive Language Online (ALW2), pp. 11–20. Association for Computational Linguistics, Brussels, Belgium (2018)

Sakki, I., Martikainen, J.: Mobilizing collective hatred through humour: affective–discursive production and reception of populist rhetoric. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 60, 610–634 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12419

Fielitz, M., Ahmed, R.: It’s not funny anymore. Far-right extremists’ use of humour. Radicalisation Awareness Network, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union (2021)

Vidgen, B., Harris, A., Nguyen, D., Tromble, R., Hale, S., Margetts, H.: Challenges and frontiers in abusive content detection. In: Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Abusive Language Online, pp. 80–93. Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy (2019)

Hatakka, N.: Expose, debunk, ridicule, resist! Networked civic monitoring of populist radical right online action in Finland. Inf. Commun. Soc. 23, 1311–1326 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1566392

Hakoköngäs, E., Halmesvaara, O., Sakki, I.: Persuasion through bitter humor: multimodal discourse analysis of rhetoric in internet memes of two far-right groups in Finland. Soc. Media Soc. 6, 205630512092157 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120921575

Waseem, Z., Davidson, T., Warmsley, D., Weber, I.: Understanding abuse: a typology of abusive language detection subtasks. In: Proceedings of the First Workshop on Abusive Language Online, pp. 78–84. Association for Computational Linguistics, Vancouver, BC, Canada (2017)

Davidson, T., Warmsley, D., Macy, M., Weber, I.: Automated hate speech detection and the problem of offensive language. ICWSM 11, 512–515 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v11i1.14955

Kocoń, J., Figas, A., Gruza, M., Puchalska, D., Kajdanowicz, T., Kazienko, P.: Offensive, aggressive, and hate speech analysis: from data-centric to human-centered approach. Inf. Process. Manag. 58, 102643 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2021.102643

Vidgen, B., Botelho, A., Broniatowski, D., Guest, E., Hall, M., Margetts, H., Tromble, R., Waseem, Z., Hale, S.: Detecting East Asian prejudice on social media (2020)

Obermaier, M., Schmuck, D., Saleem, M.: I’ll be there for you? Effects of Islamophobic online hate speech and counter speech on Muslim in-group bystanders’ intention to intervene. New Media Soc. 25, 2339–2358 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211017527

Khurana, U., Vermeulen, I., Nalisnick, E., Van Noorloos, M., Fokkens, A.: Hate speech criteria: a modular approach to task-specific hate speech definitions. In: Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop on Online Abuse and Harms (WOAH), pp. 176–191. Association for Computational Linguistics, Seattle, Washington (Hybrid) (2022)

Kshirsagar, R., Cukuvac, T., McKeown, K., McGregor, S.: Predictive embeddings for hate speech detection on Twitter. In: Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Abusive Language Online (ALW2), pp. 26–32. Association for Computational Linguistics, Brussels, Belgium (2018)

Fell, M., Akhtar, S., Basile, V.: Mining annotator perspectives from hate speech corpora. In: NL4AI@AI*IA (2021)

Sang, Y., Stanton, J.: The origin and value of disagreement among data labelers: a case study of individual differences in hate speech annotation. In: Smits, M. (ed.) Information for a Better World: Shaping the Global Future, pp. 425–444. Springer, Cham (2022)

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K., Toutanova, K.: BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. CoRR. abs/1810.04805 (2018)

Virtanen, A., Kanerva, J., Ilo, R., Luoma, J., Luotolahti, J., Salakoski, T., Ginter, F., Pyysalo, S.: Multilingual is not enough: BERT for Finnish. http://arxiv.org/abs/1912.07076 (2019)

Grootendorst, M.: BERTopic: neural topic modeling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.05794 (2022)

Egger, R., Yu, J.: A topic modeling comparison between LDA, NMF, Top2Vec, and BERTopic to demystify Twitter posts. Front. Sociol. 7, 886498 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2022.886498

Traag, V.A., Waltman, L., Van Eck, N.J.: From Louvain to Leiden: guaranteeing well-connected communities. Sci. Rep. 9, 5233 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41695-z

Porter, M.A., Onnela, J.-P., Mucha, P.J.: Communities in networks. Not. AMS 56, 1082–1097 (2009). https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.0902.3788

Kassambara, A.: Practical guide to principal component methods in R: PCA, M(CA), FAMD, MFA, HCPC, factoextra. STHDA (2017)

Wahlström, M., Törnberg, A., Ekbrand, H.: Dynamics of violent and dehumanizing rhetoric in far-right social media. New Media Soc. 23, 3290–3311 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820952795

Jasper, J.M., Poulsen, J.D.: Recruiting strangers and friends: moral shocks and social networks in animal rights and anti-nuclear protests. Soc. Probl. 42, 493–512 (1995). https://doi.org/10.2307/3097043

Unlu, A, Lac, T., Sawhney, N., Tammi, T. and Kotonen, T (n.d.) From prejudice to polarization: tracing the forms of online hate speech targeting LGBTQ+ and muslim communities in Finland

Åkerlund, M.: Influence without metrics: analyzing the impact of far-right users in an online discussion forum. Soc. Media Soc. 7, 205630512110088 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211008831

Unlu, A., Kotonen, T.: Online polarization and identity politics: an analysis of Facebook discourse on Muslim and LGBTQ+ communities in Finland. Scand. Polit. Stud. 47, 199–231 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12270

Åkerlund, M.: The importance of influential users in (re)producing Swedish far-right discourse on Twitter. Eur. J. Commun. 35, 613–628 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323120940909

Söderlund, P., Grönlund, K.: Can a change in the leadership of a populist radical right party be traced among voters? The case of the Finns Party. Scand. Polit. Stud. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12263

Moffitt, B.: How to perform crisis: a model for understanding the key role of crisis in contemporary populism. Gov. Oppos. 50, 189–217 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.13

Burke, S., Diba, P., Antonopoulos, G.A.: ‘You sick, twisted messes’: the use of argument and reasoning in Islamophobic and anti-semitic discussions on Facebook. Discourse Soc. 31, 374–389 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926520903527

Sami, W.Y., Lambert, A.H.: Antisemitism and Islamophobia: old and dynamic racisms. In: Johnson, K.F., Sparkman-Key, N.M., Meca, A., Tarver, S.Z. (eds.) Developing Anti-racist Practices in the Helping Professions: Inclusive Theory, Pedagogy, and Application, pp. 361–390. Springer, Cham (2022)

Kuisma, M., Nygård, M.: Immigration, integration and the Finns Party: issue-ownership by coincidence or by stealth? In: Odmalm, P., Hepburn, E. (eds.) The European Mainstream and the Populist Radical Right, pp. 71–89. Routledge, New York (2017)

Kuhar, R., Ajanović, E.: Sexuality online: the construction of right-wing populists’ “internal others” on the web. In: Pajnik, M., Sauer, B. (eds.) Populism and the Web, pp. 141–156. Routledge, London (2017)

Tolsma, J., Spierings, N.: Twitter and divides in the Dutch parliament: social and political segregation in the following, @-mentions and retweets networks. Inf. Commun. Soc. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2024.2305159

Praet, S., Martens, D., Van Aelst, P.: Patterns of democracy? Social network analysis of parliamentary Twitter networks in 12 countries. Online Soc. Netw. Media 24, 100154 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.osnem.2021.100154

Engesser, S., Fawzi, N., Larsson, A.O.: Populist online communication: introduction to the special issue. Inf. Commun. Soc. 20, 1279–1292 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1328525

Backström, J., Creutz, K., Pyrhönen, N.: Making enemies: reactive dynamics of discursive polarization. In: Pettersson, K., Nortio, E. (eds.) The Far-Right Discourse of Multiculturalism in Intergroup Interactions, pp. 139–162. Springer, Cham (2022)

Knuutila, A., Kosonen, H., Saresma, T., Haara, P., Pöyhtäri, R.: Viha vallassa: Vihapuheen vaikutukset yhteiskunnalliseen päätöksentekoon. [Hate in power: the effects of hate speech on social decision-making.] https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/161812 (2019)

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. The primary author was awarded research grants by the Nordic Research Council for Criminology (NSfK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AU (Ali Unlu) was responsible for the overall research design, data collection process, and management of text annotation trainings. Additionally, AU conducted both network analysis and correspondence analysis, and was instrumental in structuring the overall framework of the paper. ST (Sophie Truong) took the lead on the text classification component of the study, and was pivotal in the implementation and analysis of BERT for topic analysis. TK (Tommi Kotonen) spearheaded the qualitative research aspect, meticulously crafting the discussion section to ensure comprehensive interpretation and contextualization of the findings. All authors collectively engaged in the review and revision process, ensuring the manuscript's integrity and scholarly contribution.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Unlu, A., Truong, S. & Kotonen, T. Mapping the terrain of hate: identifying and analyzing online communities and political parties engaged in hate speech against Muslims and LGBTQ+ communities. Int J Data Sci Anal (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41060-024-00571-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41060-024-00571-4