Abstract

The main objective of this paper is to develop a scale that can facilitate a comprehensive assessment of intellectual virtues. To our knowledge, no instrument has been designed to assess virtuous intellectual character as a global construct, and this article aimed to fill this research gap through two studies. The first study aimed to investigate the construct validity and reliability of the scale, while the second study aimed to confirm the factorial structure observed in Study 1 and to analyze the convergent validity of the new scale. Study 1 included 545 college students (mean age = 19.57 years, SD = 1.41) enrolled in 33 undergraduate degree programs at Argentinean universities. Study 2 included 700 college students (mean age = 18.07, SD = 0.95). The EFA carried out in Study 1 identified five dimensions of the VICS (attentiveness, open-mindedness, curiosity, carefulness, and intellectual autonomy), and the CFA carried out in Study 2 validated the five-factor structure. A bifactor model indicated that each group of items was related to a specific virtue while simultaneously being linked to a bifactor or global construct, i.e., “a virtuous intellectual character.” Our results confirm the existence of a global construct while preserving the specificity of each virtue. The results of Study 2 indicated that the VICS total score and its five factors are associated with intellectual humility, deep thinking, bravery, academic engagement, and social and psychological well-being. However, all intellectual virtues were only weakly associated with emotional well-being. Finally, both studies indicated good reliability of the VICS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, virtue epistemology has provided a new framework for studying the intellectual virtues that characterize excellent thinkers (Turri et al., 2021). The distinctive feature of the approach proposed by virtue epistemologists lies in its emphasis on the need to consider cognitive faculties and the virtues that perfect them to account for the possibility of obtaining knowledge of the truth. This approach has led to increasing interest in studying the notion of personal character in philosophy as well as a renewed interest in this topic in psychology.

In a broad sense, character traits are stable dispositions that combine perception, knowledge, emotion, motivation, and action to respond to the demands associated with different spheres of human life. Personal character is often taken to include four dimensions: moral, civic, performance, and intellectual character (Baehr, 2017; Park et al., 2017). Over the past 30 years, intellectual character has become a significant topic of discussion in philosophical circles (Baehr, 2011; Battaly, 2019; Code, 1987; Montmarquet, 1993; Roberts & Wood, 2007; Zagzebski, 1996), where it has been observed that the traits associated with intellectual character can either facilitate the achievement of epistemic goals (intellectual virtues, such as intellectual humility and open-mindedness) or hinder them (intellectual vices, such as arrogance and closed-mindedness).

For many virtue epistemologists, intellectual virtues refer to the distinctive personal qualities exhibited by excellent thinkers (Dow, 2013; King, 2021a). These qualities include abilities, habits, or traits that are directed toward epistemic goods, such as knowledge, understanding, and truth.

The catalog of intellectual virtues is flexible, and different lists have been proposed by different authors who claim that the lists they propose are not exhaustive. Thus, Robert Roberts and Jay Wood analyzed the following intellectual virtues: love of knowledge, firmness, courage and caution, humility, autonomy, generosity, and practical wisdom (Roberts & Wood, 2007). Philip Dow identified seven core intellectual virtues (Dow, 2013): courage, carefulness, tenacity, fair-mindedness, curiosity, honesty, and humility. Nathan King added two other virtues (King, 2021a): autonomy and open-mindedness. Jason Baehr also proposed a list of nine key virtues that replaced honesty and fair-mindedness with attentiveness and thoroughness (Baehr, 2015, 2021). These scholars, among others, have analyzed the characteristics of good thinkers, often in the context of educational goals, with the aim of helping cultivate such virtues in the classroom. Although researchers in the field of psychology have also begun to research the notion of a virtuous intellectual character, no validated instruments have yet been developed to assess this notion comprehensively.

The following list of nine key intellectual virtues enumerated by Baehr has been one of the most frequently considered approaches to this topic (Baehr, 2015, 2021, pp. 34–50):

-

1.

Curiosity is the habit of seeking and asking for explanations without being satisfied with superficial or easy answers. It results in a desire to know and obtain a broader and deeper understanding (Ross, 2018).

-

2.

Intellectual autonomy is the capacity to engage in active, self-directed thinking. This virtue results in the ability to think and reason for oneself (Carter, 2017).

-

3.

Intellectual humility is the willingness to own one’s intellectual strengths and limitations. This virtue results in the recognition that one still has much to learn and in the ability to rectify the situation when one realizes that one’s own opinion is wrong (Ballantyne, 2021).

-

4.

Attentiveness is the habit of being “personally present” in the learning process. This virtue helps individuals avoid distractions and dispersion and to focus on what is essential (Berinsky et al., 2024).

-

5.

Carefulness is the willingness to detect and avoid methodological errors and mistakes. This virtue results in a search for accurate conclusions and results (King, 2021a, pp. 58–80).

-

6.

Intellectual thoroughness involves investigating topics in depth and exploring the connections among them from a comprehensive perspective (Baehr, 2021, pp. 43–45).

-

7.

Open-mindedness is the capacity to listen to points of view that are opposed to one’s own in an understanding way. This virtue results in the willingness to consider issues and to think in ways to which one is not accustomed, thereby avoiding biases (Baehr, 2013b; Riggs, 2019).

-

8.

Intellectual courage is the disposition that enables one to sustain one’s ideas. This virtue results in the willingness to communicate such ideas without concern for threats or criticism and without fear of embarrassment or failure (Roberts & Wood, 2007a).

-

9.

Intellectual tenacity is the habit of accepting intellectual challenges and sustaining prolonged effort over time. This virtue helps individuals keep their proposed objectives in sight and to overcome obstacles without becoming discouraged when they experience fatigue or encounter difficulties (Dweck et al., 2014).

While philosophers have been exploring the theoretical conceptualization of intellectual virtues in further depth, psychologists have also been developing instruments to assess several of these virtues, such as curiosity (Bluemke et al., 2023; Yow et al., 2022), open-mindedness (Haran et al., 2013), and grit (Duckworth et al., 2007). Intellectual humility, meanwhile, has received a great deal of attention in the past decade, representing the most frequently studied intellectual virtue by far (Porter et al., 2021). This virtue has been conceptualized in various ways, for example, by contrasting it with vices such as arrogance and vanity (Roberts & Wood, 2003), considering it to be an orientation toward recognition of one’s own intellectual limitations (Whitcomb et al., 2015) or viewing it as a willingness to own one’s intellectual weaknesses and strengths (King, 2021b). In addition, a variety of scales have been designed to measure intellectual humility, such as those developed by Alfano (2017), Leary et al. (2017), and Krumrei-Mancuso (2019).

Recently, it has been noted that studies on intellectual humility by psychologists have focused primarily on the assessment of this virtue; furthermore, it has been suggested that such studies may already be entering a new phase based on exploration of how intellectual humility can mutually reinforce other intellectual virtues in the process of shaping an excellent intellectual character (Jayawickreme & Fleeson, 2023, p. 238). Such investigations can also be very useful in the context of education.

Some virtue epistemologists have argued that education should focus on cultivating students’ intellectual virtues (Baehr, 2013a; Battaly, 2016; Pritchard, 2013). As a goal of education, an education that seeks to cultivate intellectual virtues, or teaching for intellectual virtues, involves the intentional and thoughtful cultivation of deep and effective habits through continuous practice (Baehr, 2021). Educators who are committed to this ideal have developed self-report measures that can help students reflect on their intellectual character with the goal of improving it. One prominent such measure is Jason Baehr’s Virtue-Based Self-Assessments (Baehr, 2015, 2021, pp. 197–200).

However, despite the importance of intellectual virtues in the context of education, to date, no psychometrically validated instruments have been developed to facilitate the comprehensive assessment of a virtuous intellectual character. Moreover, such an instrument would make it possible to advance the research on other questions that virtue epistemology has highlighted but that still require empirical investigation.

On the one hand, given that intellectual virtues are essential with respect to effective and motivated learning (Baehr, 2021, pp. 3–4), it can be assumed that a virtuous intellectual character is associated with academic engagement. Although several conceptualizations of academic engagement have been proposed, empirical evidence has indicated that the mechanism underlying feelings of engagement is the same across different conceptualizations (Tomás et al., 2020). According to the conceptualization developed by Schaufeli, academic engagement is a positive and satisfying state of mind that is related to learning and characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption. Vigor represents a high level of mental energy and resilience alongside persistence in the context of learning. Dedication can be described as a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, pride, and challenge. Finally, absorption is characterized by total concentration and deep absorption in the context of studying, which causes time to seem to pass quickly and gives rise to difficulties regarding individuals’ attempts to disengage from the task at hand (Schaufeli et al., 2002, p. 74). The instrument developed by Schaufeli has already been used successfully in many countries, including Argentina (Mesurado et al., 2016).

On the other hand, it can also be assumed that virtuous intellectual character is associated with human flourishing (Mesurado & Vanney, forthcoming). According to Baehr (2006, p. 507), intellectual character in the philosophical sense refers to essential elements of cognitive flourishing or well-being. Pritchard (2016, p. 115) also claims that intellectual virtues are essential traits in human flourishing and, as such, should be valued in their own right and not merely in terms of their practical use; similarly, King holds that such virtues play a central role in both individual and collective flourishing (King, 2021a, p. x). To date, eudemonic psychologists have proposed the most comprehensive approaches to human well-being based on a multidimensional conceptualization of human flourishing, including emotional, psychological, and social dimensions (Keyes, 2005, 2013). Several years ago, a multidimensional flourishing scale based on Keyes’s proposal was developed and validated in Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Portugal, and Spain (Mesurado et al., 2018).

The main objective of this paper is to develop a scale that can facilitate a comprehensive assessment of intellectual virtues. Two studies were conducted to address this issue. The first study aimed to investigate the construct validity and reliability of the scale, while the second study aimed to confirm the factorial structure observed in Study 1 and to analyze the convergent validity of the new scale.

1.1 Study 1. Objectives

The first aim of Study 1 is to examine the construct validity of the Spanish version of the Virtue-Based Self-Assessments instrument designed by Baehr (2015, 2021, pp. 197–200). A second aim of this study is to investigate the internal consistency of the new scale.

2 Methods

The procedures performed in the studies were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The participants of both studies signed informed consent forms.

2.1 Participants

The sample on which this research focused included 545 college students (275 women, 50.46%; 263 men, 48.26%; and 7 nonbinary students, 1.28%) who were enrolled in 33 undergraduate degree programs (e.g., medicine, economics, law, education) at Argentinean universities located in Buenos Aires. The students’ ages ranged from 17 to 25 years, and their mean age was 19.57 years, with a standard deviation of 1.41 years. Most students (98.9%) reported no disabilities, while 0.1% reported dyslexia or visual or pulmonary impairment. The sample size is adequate to perform the proposed factor analysis (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014; MacCallum et al., 1999).

With the intention of characterizing the family educational context in which the student was raised, data were collected on the educational level of the parents. In terms of the highest level of education attained by the students’ fathers or guardians, 3.9% had completed elementary school, 30.6% had completed high school, 40% had completed university education, 23.3% had completed a postgraduate program, and 2.2% of participants preferred not to answer this question. In terms of the highest level of education attained by the students’ mothers or guardians, 2.2% had completed elementary school, 23.9% had completed high school, 56.9% had completed university education, 16% had completed a postgraduate program, and 1.1% of participants preferred not to answer this question.

To recruit the sample on which this research focused, we used the nonprobabilistic snowball procedure. In our study, we initially contacted university students from different undergraduate programs and asked them to connect with other students until we reached the sample size described in this study. The students’ participation in this research was anonymous, and they received no compensation for their participation in this study. The recruitment period started on October 4, 2021, and ended on August 27, 2022.

2.2 The Original Virtue-Based Self-Assessments Instrument

The original Virtue-Based Self-Assessments instrument designed by Baehr (2015, 2021) measures nine intellectual virtues using 72 items: curiosity (e.g., “My classes often leave me wondering about the topics we discussed”), intellectual autonomy (e.g., “I am an independent thinker”), intellectual humility (e.g., the reverse-scored item “I am right about most things”), attentiveness (e.g., “I enjoy paying attention”), intellectual carefulness (e.g., the reverse-scored item “I make careless errors in my schoolwork”), intellectual thoroughness (e.g., “I like to get to the bottom of things that interest me”), open-mindedness (e.g., “I like to hear different perspectives”), courage (e.g., the reverse-scored item “When my answer is different from everyone else’s, I avoid speaking up”), and intellectual tenacity (e.g., “Even if a class is boring, I work hard to pay attention and learn”). Each subscale includes a total of 8 items, 3 or 4 of which are reverse scored.

The participant is asked to score each statement on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, which includes the following options: 1 = “Very different from me,” 2 = “Different from me,” 3 = “Neither different from me nor like me,” 4 = “Like me,” and 5 = “Very much like me.”

2.3 The Process of Translating the Virtue-Based Self-Assessments Instrument

A professional with a dual degree in philosophy and psychology, a philosopher specializing in virtue epistemology, and a psychologist specializing in psychometrics participated in the process of translating the scale from English into Spanish. The professional with a dual degree in philosophy and psychology is fluent in English, and he performed the initial translation. The three professionals then discussed the translation of each statement until a consensus was reached. The emphasis of this process was on achieving a conceptual translation rather than a literal translation of the items with the goal of ensuring that the instrument used more natural and appropriate language for the participants. In accordance with the guidelines and standards pertaining to educational and psychological testing, the translation process involved not only translating the language used in the test to ensure that it was suitable for Argentine participants but also discussing linguistic and cultural characteristics to ensure that the instrument would be able to assess each intellectual virtue appropriately (American Educational Research Association et al., 2014).

2.4 Statistical Procedures

To investigate the construct validity of the Spanish version of the Virtue-Based Self-Assessments instrument, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted using JASP software version 0.16. The Kaiser‒Meyer‒Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were utilized to determine the convenience of the procedure based on exploratory factor analysis (EFA). A scree plot and parallel analysis were used to determine the number of factors or dimensions. The principal axis factoring method and Varimax rotation were also utilized.

Finally, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated to assess the scale’s internal consistency.

3 Results

To determine the validity of the Spanish version of the Virtue-Based Self-Assessments instrument, we first aimed to conduct various analyses to determine the construct validity and internal consistency of this measure.

3.1 Investigation of Construct Validity

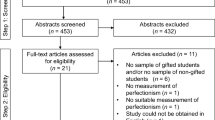

Exploratory factor analysis was used to investigate the construct validity of Baehr’s Spanish version of the Virtue-Based Self-Assessments instrument. The KMO test revealed a value of 0.84, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity revealed a value of 4168.90, df = 148, p <.001. The scree plot suggested five dimensions or factors, which explained 45% of the variance (see Fig. 1). The parallel analysis also indicated the existence of 5 factors (see Table 1). The principal axis factoring method and varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization were used to determine the distribution of the items into these five factors. The rotation converged in 13 interactions, and the loading factors of the items ranged between 0.41 and 0.78 (see Table 2).

Three criteria were used to determine whether an item should be maintained in the scale: (a) each factor was composed of at least three items, (b) the factor loading of each item was equal to or greater than 0.40, and (c) the difference in loadings among factors was greater than 0.10 (Kahn, 2006; Worthington & Whittaker, 2006). Based on these criteria, a new scale was obtained, which included 23 items distributed across 5 subscales: attentiveness, open-mindedness, curiosity, carefulness, and intellectual autonomy. As our results did not confirm the original structure of the nine dimensions of the Virtue-Based Self-Assessments instrument, we decided to rename the new instrument, with the original author’s consent, the Virtuous Intellectual Character Scale (VICS). In addition, these instruments are designed for various purposes. While the Virtue-Based Self-Assessments were designed for educational purposes to facilitate students’ self-reflection on their intellectual character, the VICS is psychometrically validated.

3.2 Internal Consistency

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the total score was α = 0.85. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each subscale were as follows: attentiveness (α = 0.83), open-mindedness (α = 0.83), curiosity (α = 0.76), carefulness (α = 0.73), and intellectual autonomy (α = 0.56). The reliability indices pertaining to the total scale score and all subscales reached the recommended reliability threshold of 0.70 with the exception of the intellectual autonomy subscale. The failure of this subscale to reach the recommended threshold may be due to the fact that it contains only three items (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994, p. 252). However, this subscale was retained because removal of the items included in the intellectual autonomy subscale did not result in any significant improvement in the reliability of the total scale.

3.2.1 Study 2. Objectives

The first aim of Study 2 is to confirm the five-structure factors (including attentiveness, open-mindedness, curiosity, carefulness, and intellectual autonomy) of the VICS developed in Study 1. In addition, the theoretical models will also be compared to refine the conceptualization of a virtuous intellectual character.

The second aim of this study is to study the scale’s internal consistency and convergent validity by referencing a large sample.

4 Methods

4.1 Participants

The sample included 700 college students (374 women, 53.4%; 323 men, 46.4%; and 1 participant who did not answer this question, 0.1%) who were enrolled in 17 undergraduate courses (e.g., medicine, economics, law, education) at an Argentinean university located in Buenos Aires. The students’ ages ranged from 17 to 24 years, and their mean age was 18.07 years, with a standard deviation of 0.95 years. Most students (98.4%) reported no disabilities, while 1.6% of participants reported dyslexia, hyperactivity deficit, or visual or motor impairment. The sample size is adequate to perform the proposed factor analysis (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014; MacCallum et al., 1999).

According to the data we collected, 4.4% of the students’ fathers or guardians had completed elementary school, 30% had completed high school, 41.4% had completed university education, 21.9% had completed a postgraduate program, and 2.3% of the participants did not want to answer this question. However, 1.9% of the students’ mothers or guardians had completed elementary school, 22.7% had completed high school, 54.4% had completed university education, 19.6% had completed a postgraduate program, and 1.4% of the participants did not want to answer this question.

To collect the sample, we recruited students in their first years at an Argentine university. The students’ participation in this research was voluntary and anonymous, and they did not receive any compensation for their participation in this study. The recruitment period started on March 3, 2023, and ended on April 3, 2023.

4.2 Instruments

Virtuous Intellectual Character Scale (VICS). The 23-item VICS developed in Study 1 was used. VICS measures attentiveness (e.g., “I enjoy paying attention”), open-mindedness (e.g., “I like to hear different perspectives”), curiosity (e.g., “The world is a fascinating place to discover”), carefulness (e.g., “I take the time I need to get the answer right”), and intellectual autonomy (e.g., “When someone gives me advice, I like to think it through for myself”). The participants were asked to score each statement on a 5-point frequency rating scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

The Intellectual Humility Scale developed by Leary and colleagues (2017) was used. This scale features six items, including “I question my own opinions, positions, and viewpoints because they could be wrong.” Participants scored each statement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all like me) to 5 (very much like me). High scores indicate high levels of intellectual humility. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for intellectual humility was 0.87.

Engagement. The 17-item Utrecht Student Engagement Scale (UWES; Schaufeli, Martinez, et al., 2002) was used to measure academic engagement among students. The Utrecht Student Engagement Scale includes three subscales: vigor (6 items; e.g., “I can continue studying for a very long time,” α = 0.86); dedication (5 items; e.g., “My studies inspire me,” α = 0.92); and absorption (6 items; e.g., “Time flies when I’m studying,” α = 0.84). The participants were asked to score each statement on a 7-point frequency rating scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always).

Flourishing. The 12-item Multidimensional Flourishing Scale developed by Mesurado et al. (2021) was used to measure student flourishing. The Multidimensional Flourishing Scale includes three subscales: social well-being (4 items, e.g., “I feel close to other members of society,” α = 0.75); psychological well-being (4 items, e.g., “I am happy with my current lifestyle,” α = 0.81); and emotional well-being (4 items, e.g., “Angry vs. content,” α = 0.71). The participants were asked to score social and psychological well-being on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Moreover, the emotional well-being subscale was measured on a 5-point semantic differential scale ranging from 1 = negative emotions to 5 = positive emotions.

Deep ThinkingFootnote 1. The Spanish version of the thoroughness subscale of the Virtue-Based Self-Assessments by Baehr (2015, 2021) was used. Previously, an exploratory factor analysis was performed using the sample of Study 1, revealing a unidimensional structure (KMO = 0.79, Bartlett’s test of sphericity = 783.72, explaining 54.48% of the variance). CFA was performed using the sample of Study 2, which confirmed the unidimensional structure (chi-square test = 8.16, df = 5, p =.15, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.03, SRMR = 0.02). The scale is composed of 5 items: (i) “When I get interested in something,” (ii) “It is more important to understand what I am learning than to get a good grade,” (iii) “I like to get to the bottom of things that interest me,” (iv) “When I don’t understand something, I try to find out more,” and (v) “It bothers me when I don’t understand what the teacher is talking about”. The participants were asked to score each statement on a 5-point frequency rating scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for Deep Thinking using the sample of Study 2 was 0.78.

Intellectual Courage (see Footnote 1). The Spanish version of the intellectual courage subscale of the Virtue-Based Self-Assessments by Baehr (2015, 2021) was used. Previously, an exploratory factor analysis was performed using the sample of Study 1, revealing a bidimensional structure (KMO = 0.75, Bartlett’s test of sphericity = 566.33, explaining 53.60% of the variance). CFA was performed using the sample of Study 2, which confirmed the bidimensional structure (chi-square test = 38.22, df = 12, p =.001, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.04). The scale is composed of 7 items that measure two aspects of intellectual courage: bravery and cowardice. The intellectual bravery subscale includes 4 items: (i) “I am willing to answer a question even if I think my answer might be wrong,” (ii) “I stand up for what I believe in,” (iii) “I speak up in class even when I am nervous about doing so,” and (iv) “I am willing to take risks to learn more”. The intellectual cowardice subscale includes 3 items: (i) “When my answer is different from everyone else’s, I avoid speaking up,” (ii) “Fear often prevents me from learning more,” and (iii) “If I think my friends might laugh at me, I keep my opinion to myself”. The participants were asked to score each statement on a 5-point frequency rating scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). For the convergent study, we used the bravery dimension, which had a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.59.

4.3 Statistical Procedures

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using the MPLUS program to confirm the structural factor of the VICS developed in Study 1. We compared different models or structural factors. Specifically, we compared a five-factor model (Model 1), a unidimensional model (Model 2), a second-order model (Model 3), and a bifactor model (Model 4).

The five-factor model (Model 1) identifies five interrelated intellectual virtues. In the unidimensional model (Model 2), all items are related to a general factor (a virtuous intellectual character) without distinguishing between specific dimensions or factors. The second-order model (Model 3) identifies 5 intellectual virtues (first-order latent variables) related to a general factor, which is the virtuous intellectual character (second-order variable). Bifactor models may be relevant when a general factor explains the commonality among items associated with a factor or dimension and in situations featuring several factors or dimensions, each of which captures the distinct impact of a specific dimension beyond that of the general factor (Chen & Zhang, 2018). In other words, bifactorial models can also be relevant when researchers are interested in developing an instrument that allows them to capture or measure both a general factor and specific factors or dimensions.

The comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker‒Lewis index (TLI) were used to measure the goodness of fit exhibited by the models, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) were used as error measures.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated to assess the scale’s internal consistency. Finally, the Pearson correlation was used to investigate the convergent validity between the VICS and the measures of intellectual humility, academic engagement, and flourishing among students obtained using other scales.

5 Results

We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to determine the extent to which the five structure factors of the VICS represent an appropriate measure of virtuous character.

5.1 Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Model Comparison

The mean and variance-adjusted weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimator was used to estimate all models account for the ordinal nature of the VICS’s items as suggested Brauer et al. (2023). Moreover, the modification index was used to improve the goodness of fit exhibited by the model. The modification index suggested a correlation between the error variance associated with two pairs of items (O2/O6 with O4/O1 and O5/O3 with O3/O4)Footnote 2 with regard to all the models tested. Table 3 shows the chi-squared, degrees of freedom, Akaike information criterion (AIC) values, and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) values for the models.

An initial confirmatory factor analysis was performed to test the five-factor model (Model 1). The fit indices thus obtained were CFI = 0.93 and TLI = 0.92; the error measures were RMSEA 0.05 and SRMR = 0.05.

The second model tested was the unidimensional model (Model 2). That is, in this model, all the items were related to a unique factor. The fit indices thus obtained were CFI = 0.74 and TLI = 0.71; the error measures were RMSEA 0.09 and SRMR = 0.07.

The third model tested was a second-order model (Model 3). That is, a second-order factor encompassing the five dimensions described in Model 1 was included in this model. The fit indices thus obtained were CFI = 0.93 and TLI = 0.92, and the error measures were RMSEA 0.05 and SRMR = 0.05.

Finally, the fourth model tested was the bifactor model (Model 4). That is, each group of items was related to its specific factor in this model, and all items were simultaneously linked to a bifactor. The fit indices thus obtained were CFI = 0.95 and TLI = 0.94; the error measures were RMSEA 0.04 and SRMR = 0.04. Table 4 shows a clear associations between items and their specific factor as well as their general factor.

Notably, the results thus obtained indicated that the unidimensional model exhibited the worst fit, while the bifactor model exhibited the best fit. These results indicate the existence of a general factor (i.e., virtuous intellectual character) that explains the commonality among items related to a dimension or factor. Simultaneously, five factors or virtues are retained, each of which explains a specific aspect of a virtuous intellectual character over and above the general factor.

5.2 Internal Consistency

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the total score was α = 0.82. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each subscale were as follows: α = 0.75 for attentiveness, α = 0.81 for open-mindedness, α = 0.78 for curiosity, α = 0.74 for carefulness, and α = 0.57 for intellectual autonomy. The reliability indices associated with the total scale score and all subscales reached the recommended reliability threshold of 0.70, with the exception of the intellectual autonomy subscale, as observed in Study 1.

5.3 Convergent Validity

Pearson correlations among the total score on the VICS and the scores on its subscales with intellectual humility, deep thinking, bravery, academic engagement, and flourishing were calculated. The literature considers that a correlation value between 0.10 and 0.30 represents a small effect, values between 0.30 and 0.50 represent a moderate effect, and values greater than 0.50 represent a large effect (Cohen, 2013). The results of Study 2 indicated that the VICS total score and its five factors are associated with intellectual humility, deep thinking, bravery, academic engagement (vigor, dedication, and absorption), and social and psychological well-being. However, all intellectual virtues were only weakly associated with emotional well-being (see Table 5).

6 Discussion

The character education movement has expanded substantially in recent years as both a goal of education and a fertile field for academic study (Matthews & Lerner, 2024). One pillar of character education is the development of intellectual character, which focuses on the cultivation of intellectual virtues. To evaluate the development of these character traits, several instruments have been developed to assess specific intellectual virtues, such as curiosity, open-mindedness, and grit (Bluemke et al., 2023; Duckworth et al., 2007; Haran et al., 2013; Yow et al., 2022). However, to our knowledge, no instrument has been designed to assess a virtuous intellectual character as a global construct, and this article aimed to fill this research gap.

Organizations interested in promoting the cultivation of intellectual virtues, such as K-12 schools and universities, must intentionally concentrate on a specific subset of intellectual virtues to manage their efforts effectively. Educational institutions often need more clarification about which virtues they should prioritize. Moreover, evaluating intellectual character development can be very demanding for them. The present paper provides a solution for these challenges: first, it offers a focused and unified subset of intellectual virtues, and second, it proposes a single measure for assessing them.

Based on Jason Baehr’s (2021) theoretical proposal, Study 1 aimed to examine the construct validity of the Spanish version of the Virtue-Based Self-Assessments instrument. The original scale identified nine intellectual virtues as relevant character traits of excellent thinkers: curiosity, intellectual autonomy, intellectual humility, attentiveness, intellectual carefulness, intellectual thoroughness, open-mindedness, courage, and intellectual tenacity. However, the exploratory factor analysis results identified only five dimensions as part of a single construct: attentiveness, open-mindedness, curiosity, carefulness, and intellectual autonomy. This new instrument, which facilitates the comprehensive assessment of a set of intellectual virtues, was renamed the VICS. A second study, which included approximately 700 university students, confirmed the five-factor structure and the previously obtained results.

Furthermore, four confirmatory factor analyses were tested with regard to the new scale: a five-factor model, a one-dimensional model, a second-order model, and a bifactor model. The bifactor model exhibited the best fit, thus indicating that each group of items was related to a specific virtue (i.e., attentiveness, open-mindedness, curiosity, carefulness, or intellectual autonomy) while simultaneously being linked to a bifactor or global construct, i.e., “a virtuous intellectual character.” Consequently, our results confirm the existence of a global construct while preserving the specificity of each virtue.

Although a variety of psychometric instruments have been designed in recent years to assess certain epistemic virtues individually, in which context proposals to measure intellectual humility have been the most notable (Porter et al., 2021), little research has focused on the comprehensive study of a virtuous intellectual character or on how intellectual virtues are interrelated (Jayawickreme & Fleeson, 2022). Researchers have recently noted that a virtuous intellectual character may be able to have successful effects only when individuals possess not only one intellectual virtue but also an extensive set of such virtues to different degrees (Ratchford et al., 2024). For this reason, it is perhaps more appropriate to speak of a virtuous intellectual character, which several combinations of epistemic virtues may delineate, than to speak of the virtuous intellectual character as a univocal notion.

In addition to confirming the five factors that characterize the VICS’s structure and the results of Study 1, Study 2 also aims to study the VICS’s convergent validity regarding intellectual humility, deep thinking (thoroughness), bravery (courage), academic engagement, and flourishing.

The results of this study confirmed a strong correlation between intellectual humility and open-mindedness and moderate correlations with regard to attentiveness, carefulness, curiosity, and autonomy. These relationships highlight the fact that intellectual virtues are interconnected and complementary and can mutually reinforce one another in the context of personal and cognitive development.

The results also corroborated a strong correlation between deep thinking and the VICS total score, with stronger correlations with the intellectual virtues of attentiveness, open-mindedness, and curiosity. This is not surprising since it is reasonable to infer that a greater capacity for focused attention, an open-minded approach to issues from different perspectives, and an inquisitive curiosity lead to deeper thinking.

A strong correlation was also found between bravery, which corresponds to the virtuous dimension of courage, and the VICS total score. In turn, a moderate correlation was also observed between the bravery dimension and the five intellectual virtues that are dimensions of the VICS. It is reasonable to assume that individuals who have arrived at their beliefs through attentive and careful consideration, who are open to diverse and inquisitive perspectives, and who are accustomed to thinking independently are better equipped to sustain and defend their ideas even in the face of opposition.

Likewise, the results indicated that all the intellectual virtues included in the VICS are associated with the three components of academic engagement (vigor, dedication, and absorption). It is thus reasonable to conclude that the cultivation of intellectual virtues contributes positively to the development of a more committed attitude toward one’s education, thereby facilitating more active, self-motivated studying, and encouraging individuals to involve themselves emotionally in their learning; these contributions, in turn, encourage persistence and dedication to the task of studying even in challenging situations.

However, intellectual virtues are not limited to the academic sphere; they are also crucial in everyday life beyond the classroom and university settings. In this sense, our results revealed that a virtuous intellectual character is associated with human flourishing. Specifically, we found that the conceptualization of a virtuous intellectual character operationalized in the VICS is moderately associated with the social and psychological well-being dimensions of human flourishing and is also associated with the emotional well-being dimension to some degree. Because emotional well-being is a state of mind that can fluctuate rapidly, it is less strongly linked to stable dispositions such as character traits. These results are consistent with the conclusions of previous research that has indicated that virtues are associated with profound conceptions of happiness that endure over time, such as social and psychological well-being (Kim & Lim, 2016).

Moreover, the association we observed between the conceptualization of a virtuous intellectual character operationalized in the VICS and the social (commitment) and psychological (purpose) dimensions of human flourishing emphasizes the motivational component of intellectual virtues. In this sense, this study’s results also provide empirical evidence to support the distinction between intellectual virtues and skills, which has often been mentioned by virtue epistemologists (Baehr, 2011, pp. 29–32).

In summary, the cultivation of epistemic virtues such as attentiveness, open-mindedness, curiosity, carefulness, and autonomy can help people reach their full intellectual and cognitive potential. This intellectual character development also contributes to human flourishing by enabling people to know themselves better, develop their skills and talents, contribute to the creation of a better society (social well-being), and find meaning and purpose in their lives (psychological well-being).

Finally, both studies indicated that the internal consistency of the VICS is good. Indeed, both the overall score on the VICS and the scores pertaining to each intellectual virtue (except for autonomy) exhibited a high level of reliability. However, the autonomy subscale has lower internal consistency, probably due to the small number of items that comprise this scale, which consequently reduces the alpha (see, for example, Ziegler et al., 2014).

In summary, this article provides strong evidence indicating that the VICS is a valid and reliable instrument for assessing intellectual character. The VICS can effectively measure five critical intellectual virtues, and it thus represents a valuable tool for assessing important intellectual character traits among students.

6.1 Limitations of the Study and Prospects for Better Measurement of Intellectual Virtues

The VICS can effectively measure five essential intellectual virtues; however, further work is needed on the intellectual autonomy subscale of the VICS because it obtained low levels of reliability in both studies. The intellectual autonomy subscale is brief and includes very few items; thus, its operationalization could be improved by developing new items to better capture various aspects of autonomy.

Some intellectual virtues were not included in the VICS. In the future, alternative instruments that can complement VICS could include the measurement of other intellectual virtues, such as intellectual honesty and fair-mindedness.

Another limitation of this study lies in the nonprobabilistic sample selection method. This methodology introduces a potential bias by nonrandomly selecting participants, which may compromise the sample’s representativeness and, consequently, the generalizability of the findings to the broader population of Argentinean students. Indeed, by not using a probability method, there is a risk that specific segments of Argentinean students may be under- or overrepresented in the sample. Likewise, it would be interesting to apply the VICS to university students from other Latin American countries to analyze its validity and reliability in other Spanish-speaking cultures and to analyze the cross-cultural invariance of the bifactor model. Moreover, an important limitation of our study is the age range of the participants. By including only individuals between 17 and 25 years old, we may not fully capture the variability in intellectual virtues that could be observed in a broader, more age-diverse population.

6.2 Conclusion and Directions for Future Research on Intellectual Virtues

The study presented in this paper serves as an initial step toward delineating a virtuous intellectual character. On the one hand, this study validates an instrument that can be used to assess a group of five intellectual virtues comprehensively. On the other hand, the results we obtained enable us to propose the following general hypothesis that should be corroborated by future research: the nine intellectual virtues studied by Baehr (2021) should not be viewed as existing at the same level, i.e., some virtues are more fundamental than others or the cause of others. This general hypothesis, in turn, can be divided into several sub-hypotheses that can be analyzed by a variety of future studies.

The five intellectual virtues included in the VICS (curiosity, open-mindedness, attentiveness, carefulness, and autonomy) could be viewed as proper characteristics of the knowledge process; thus, they are grouped together within the same construct. Curiosity promotes the exploration and discovery of new ideas, open-mindedness takes into account different perspectives, attention focuses on the cognitive task at hand, thus eliminating distractions, and carefulness helps individuals critically examine information, thus contributing to the development of autonomous and self-determined thinking.

The EFA led to the exclusion of four intellectual virtues: humility, thoroughness, courage, and tenacity. This means that even though VICS is considerably more comprehensive than any individual virtue construct, it covers only part of the terrain of virtuous intellectual character. Much more research is still needed to empirically determine the relationship of VICS to intellectual virtues that fall outside the construct. Future empirical causality analyses conducted in longitudinal studies could determine, for example, whether the intellectual virtues included in VICS necessarily imply the existence of other virtue(s) at a more fundamental level. Or if the virtues of VICS are a necessary cause of the existence of other virtues not included in it.

On the one hand, intellectual humility could be viewed as a precursor of and a more fundamental virtue than the other virtues included in the VICS. Since humble people recognize that they do not know everything, they are curious and willing to learn. Such people are open to changing their minds because they are aware of the value of others’ opinions. They try to be careful and attentive because they understand that they are not infallible. In addition, humble people own their weaknesses as well as their strengths, which can enable them to think autonomously and independently.

On the other hand, intellectual thoroughness and courage may be viewed as outputs of the virtues included in the VICS. Namely, attentiveness, open-mindedness, curiosity, carefulness, and intellectual autonomy are character traits that promote deep thought and fearless communication of one’s own ideas.

Finally, while knowledge entails sustained effort over time, undertaking challenges, and tolerance to frustration, tenacity emphasizes the volitional component more than do the other intellectual virtues. This virtue is thus essential with regard to developing all the other virtues.

Longitudinal studies should be conducted to test the causal sequence suggested by these hypotheses. That is, such studies should investigate (i) whether intellectual humility represents a precursor of our conceptualization of a virtuous intellectual character and/or (ii) whether courage and thoroughnessFootnote 3 can result from a virtuous intellectual character.

In summary, this initial conceptualization of a virtuous intellectual character can inspire a great deal of research. In addition to those already mentioned, some intellectual virtues that were not considered in this study, such as intellectual honesty or fair-mindedness, could be featured as new dimensions in a more comprehensive scale that aims to measure a virtuous intellectual character. An exciting possibility in this regard would be to explore the construction of an instrument to measure intellectual autonomy more effectively, as autonomy is a crucial virtue in students’ intellectual development. Finally, an even more ambitious challenge would be to identify the necessary conditions for claiming that an individual’s possession of a group of intellectual virtues is sufficient to affirm that she exhibits a virtuous intellectual character. Research is already underway in this direction (Ratchford et al., 2024).

In any case, the VICS is a reliable instrument that can be immediately useful for evaluating the effectiveness of numerous initiatives that are beginning to be developed to teach for intellectual virtues in higher education. By using the VICS, educators can identify the strengths and weaknesses of their students’ intellectual virtues and develop appropriate teaching strategies to help them improve. Additionally, the VICS can be used to assess the impact of various interventions and programs aimed at promoting intellectual virtues, thus providing a valuable tool for educational research and evaluation.

Data availability

The databases are available at https://osf.io/j3s4f/.

Notes

Four of the nine intellectual virtues originally proposed by Jason Baehr in Deep in Thought were excluded in Study 1: intellectual humility, perseverance, intellectual courage, and thoroughness. There are instruments with good psychometric properties that measure intellectual humility (e.g., Leary, 2017) and perseverance (e.g., Duckworth et al., 2007). However, to our knowledge, no scales assess thoroughness and courage as intellectual virtues. For this reason, we have examined both scales’ psychometric properties independently to investigate whether they correlate with the virtues of the VICS.

We end old codifications of the items, respectively. O = open-mindedness.mploy the new a

In the Virtue-Based Self-Assessments instrument, thoroughness is operationalized by items such as “I like to get to the bottom of things that interest me”.

References

Alfano, M., Iurino, K., Stey, P., Robinson, B., Christen, M., Yu, F., & Lapsley, D. (2017). Development and validation of a multi-dimensional measure of intellectual humility. PLoS One, 12(8), e0182950. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182950

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education. (2014). Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. American Educational Research Association.

Baehr, J. (2006). Character in epistemology [research-article]. Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition, 128(3), 479–514. http://electra.lmu.edu:2048/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true &db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.4321733&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Baehr, J. (2011). The inquiring mind. On intellectual virtues and virtue epistemology. Oxford University Press.

Baehr, J. (2013a). Educating for intellectual virtues: From theory to practice. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 47(2), 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12023

Baehr, J. (2013b). The structure of Open-Mindedness. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 41(2), 191–213. https://doi.org/10.1353/cjp.2011.0010

Baehr, J. (2015). Cultivating good minds. A philosophical & practical guide to educating for intellectual virtues. IntelectualVirtues.org.

Baehr, J. (2017). The varieties of Character and some implications for Character Education [Report]. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(6), 1153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0654-z

Baehr, J. (2021). Deep in Thought. A practical guide to teaching for intellectual virtues. Harvard Education.

Ballantyne, N. (2021). Recent work on intellectual humility: A philosopher’s perspective. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1940252

Battaly, H. (2016). Responsibilist virtues in Reliabilist classrooms. In J. Baehr (Ed.), Intellectual virtues and education. Essays in applied virtue epistemology (pp. 163–183). Routledge.

Battaly, H. (Ed.). (2019). The Routledge handbook of virtue epistemology (1st ed.). Routledge.

Berinsky, A. J., Frydman, A., Margolis, M. F., Sances, M. W., & Valerio, D. C. (2024). Measuring attentiveness in self-administered surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 88(1), 214–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfae004

Bluemke, M., Engel, L., Gruning, D. J., & Lechner, C. M. (2023). Measuring intellectual curiosity across cultures: Validity and comparability of a New Scale in Six languages. Journal of Personality Assessment, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2023.2199863

Brauer, K., Ranger, J., & Ziegler, M. (2023). Confirmatory factor analyses in psychological test adaptation and development. Psychological Test Adaptation and Development, 4(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1027/2698-1866/a000034

Carter, J. A. (2017). Intellectual autonomy, epistemic dependence and cognitive enhancement. Synthese, 197(7), 2937–2961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1549-y

Chen, F. F., & Zhang, Z. (2018). Bifactor models in psychometric test development. The Wiley handbook of psychometric testing: A multidisciplinary reference on survey, scale and test development, 325–345.

Code, L. (1987). Epistemic responsibility. Published for Brown University Press by University Press of New England.

Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge.

Dow, P. E. (2013). Virtuous minds. Intellectual Character Development. InterVarsity.

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

Dweck, C., Walton, G., & Cohen, G. (2014). Academic Tenacity: Mindsets and Skills that Promote Long-Term Learning.

Haran, U., Ritov, I., & Mellers, B. A. (2013). The role of actively open-minded thinking in information acquisition, accuracy, and calibration. Judgment and Decision Making, 8(3), 188–201. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1930297500005921

Jayawickreme, E., & Fleeson, W. (2022). How do intellectual virtues promote good thinking and knowing? Theory and Research in Education, 20(2), 200–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/14778785221113985

Jayawickreme, E., & Fleeson, W. (2023). Understanding intellectual humility and intellectual character within a dynamic personality framework. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 18(2), 237–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2022.2154701

Kahn, J. H. (2006). Factor analysis in counseling psychology research, training, and practice: Principles, advances, and applications. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(5), 684–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006286347

Keyes, C. L. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539

Keyes, C. L. M. (2013). Mental well-being: International contributions to the study of positive mental health. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5195-8

Kim, S. Y., & Lim, Y. J. (2016). Virtues and well-being of Korean Special Education teachers. International Journal of Special Education, 31(1), 114–118.

King, N. (2021a). The excellent mind. Intellectual virtues for everyday life [Book]. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190096250.001.0001

King, N. (2021b). Humility and Self- Confidence: Own Your.

Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J., Haggard, M. C., LaBouff, J. P., & Rowatt, W. C. (2019). Links between intellectual humility and acquiring knowledge. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1579359

Leary, M. R., Diebels, K. J., Davisson, E. K., Jongman-Sereno, K. P., Isherwood, J. C., Raimi, K. T., Deffler, S. A., & Hoyle, R. H. (2017). Cognitive and interpersonal features of Intellectual Humility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(6), 793–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217697695

Lloret-Segura, S., Ferreres-Traver, A., Hernández-Baeza, A., & Tomás-Marco, I. (2014). El análisis factorial exploratorio de Los ítems: Una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. Anales De psicología/annals of Psychology, 30(3), 1151–1169.

MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Zhang, S., & Hong, S. (1999). Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 4(1), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.4.1.84

Matthews, M. D., & Lerner, R. M. (Eds.). (2024). The Routledge International Handbook of Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Character Development. Volume I: Conceptualizing and Defining Character (First edition. ed.). Routledge.

Mesurado, B., & Vanney, C. (forthcoming). The role of intellectual character and honesty in adolescent flourishing. Research in Human Develpment.

Mesurado, B., Richaud, M. C., & Mateo, N. J. (2016). Engagement, Flow, Self-Efficacy, and Eustress of University students: A cross-national comparison between the Philippines and Argentina. Journal of Psychology, 150(3), 281–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2015.1024595

Mesurado, B., Crespo, R. F., Rodríguez, O., Debeljuh, P., & Carlier, S. I. (2018). The development and initial validation of a multidimensional flourishing scale. Current Psychology, 40(1), 454–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9957-9

Montmarquet, J. A. (1993). Epistemic virtue and doxastic responsibility. Rowman & Littlefield.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric Theory New York. NY: McGraw-Hill.

Park, D., Tsukayama, E., Goodwin, G. P., Patrick, S., & Duckworth, A. L. (2017). A tripartite taxonomy of character: Evidence for intrapersonal, interpersonal, and intellectual competencies in children. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 48, 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.08.001

Porter, T., Baldwin, C. R., Warren, M. T., Murray, E. D., Bronk, C., Forgeard, K., Snow, M. J. C., N. E., & Jayawickreme, E. (2021). Clarifying the content of Intellectual Humility: A systematic review and integrative Framework. Journal of Personality Assessment, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2021.1975725

Pritchard, D. (2013). Epistemic Virtue and the Epistemology of Education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 47(2), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12022

Pritchard, D. (2016). Intellectual Virtue, Extended Cognition, and the Epistemology. In J. Baehr (Ed.), Intellectual virtues and education. Essays in applied virtue epistemology (pp. 113–127). Routledge.

Ratchford, J. L., Fleeson, W., King, N. L., Blackie, L. E. R., Zhang, Q., Porter, T., & Jayawickreme, E. (2024). Clarifying the Virtue Profile of the good thinker: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Topoi. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-024-10028-9

Riggs, W. (2019). Open-mindedness. In H. D. Battaly (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of virtue epistemology (1st ed.). Routledge.

Roberts, R., & Wood, W. (2003). Humility and Epistemic Goods. In M. R. DePaul, & L. T. Zagzebski (Eds.), Intellectual virtue: Perspectives from ethics and epistemology. Clarendon.

Roberts, R. C., & Wood, W. J. (2007). Intellectual virtues. An essay in Regulative Epistemology. Clarendon.

Roberts, R., & Wood, W. (2007a). Courage and caution. Intellectual virtues. An essay in regulative epistemology (pp. 215–235). Clarendon.

Ross, L. (2018). The Virtue of Curiosity. Episteme, 17(1), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1017/epi.2018.31

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor Analytic Approach [Article]. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326

Tomás, J. M., Gutiérrez, M., Alberola, S., & Georgieva, S. (2020). Psychometric properties of two major approaches to measure school engagement in university students. Current Psychology, 41(5), 2654–2667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00769-2

Turri, J., Alfano, M., & Greco, J. (2021). Virtue epistemology. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Vol. Winter 2021 Edtion).

Weaknesses— and Your Strengths In The Excellent Mind: Intellectual Virtues for Everyday Life (pp. 106–130). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190096250.003.0004

Whitcomb, D., Battaly, H., Baehr, J., & Howard-Snyder, D. (2015). Intellectual Humility: Owning Our Limitations. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, n/a-n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpr.12228

Worthington, R. L., & Whittaker, T. A. (2006). Scale development research: A content analysis and recommendations for best practices. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(6), 806–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006288127

Yow, Y. J., Ramsay, J. E., Lin, P. K. F., & Marsh, N. V. (2022). Dimensions, measures, and contexts in psychological investigations of curiosity: A scoping review. Behav Sci (Basel), 12(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120493

Zagzebski, L. T. (1996). Virtues of the mind. An inquiry into the nature of virtue and the ethical foundations of knowledge. Cambridge University Press.

Ziegler, M., Kemper, C. J., & Kruyen, P. (2014). Short scales–five misunderstandings and ways to overcome them. Journal of Individual Differences, 35(4), 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000148

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Jason Baehr for allowing the original ‘Virtue-Based Self-Assessments’ instrument to be renamed ‘Virtuous Intellectual Character Scale’ (VICS). They also extend their thanks to the reviewers, whose comments helped improve the text.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was made possible through the support of a grant from the John Templeton Foundation to Claudia E. Vanney (JTF 62684). The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The Institutional Review Board at Universidad Austral [CIE 22–064] approved the study and procedures. The informed consent was obtained in writing.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Virtuous Intellectual Character Scale (VICS)

English version | Spanish version |

|---|---|

Instructions: Below are a series of statements related to your attitudes toward your university studies. Indicate the degree of frequency with which you experience these attitudes. (1) never, (2) few times, (3) quite often, (4) many times, (5) always | Instrucciones: A continuación se presentan una serie de afirmaciones vinculadas a tus actitudes frente a tus estudios universitarios. Indica el grado de frecuencia con la que experimentas estas actitudes. (1) Nunca, (2) Pocas veces, (3) Bastante, (4) Muchas veces, (5) Siempre |

Attentiveness | Atención |

A1. I notice small details in stories that might become important later on. | A1. En las historias presto atención a los pequeños detalles porque luego pueden volver importantes. |

A2. I enjoy paying attention. | A2. Disfruto prestando atención. |

A3. I tend to notice details that other people miss. | A3. Tiendo a notar cosas que otros pasan por alto. |

A4. I like to look closely at things. | A4. Me gusta mirar las cosas de cerca. |

A5. I could spend a very long time looking at a detailed image. | A5. Podría pasar mucho tiempo mirando una imagen en detalle. |

Open-mindedness | Apertura mental |

O1. I am open to considering new evidence. | O1. Estoy abierto a considerar nuevas evidencias. |

O2. I am a flexible thinker. | O2. Puedo cambiar mi manera de pensar (soy flexible). |

O3. I like to hear different perspectives. | O3. Me gusta escuchar diferentes perspectivas/puntos de vista. |

O4. I am willing to change my beliefs. | O4. Estoy dispuesto a cambiar mis ideas/lo que pienso |

O5. I enjoy learning why other people believe what they believe. | O5. Me gusta saber porqué otras personas piensan como piensan |

Curiosity | Curiosidad |

Cu1. I am interested in a lot of topics. | Cu1. Estoy interesado en muchos temas. |

Cu2. I am eager to explore new things. | Cu2. Estoy entusiasmado por conocer cosas nuevas. |

Cu3. I wonder about how things work. | Cu3. Suelo preguntarme cómo funcionan las cosas. |

Cu4. My classes often leave me wondering about the topics we discussed | Cu4. Los temas que vemos en clase siempre me dejan pensando. |

Cu5. The world is a fascinating place to discover. | Cu5. El mundo es un lugar fascinante para explorar. |

Carefulness | Rigurosidad |

Ca1. I take the time I need to get the answer right. | Ca1. Me tomo el tiempo que necesito para dar la respuesta correcta. |

Ca2. I always read the directions before starting an assignment. | Ca2. Siempre leo con cuidado las consignas antes de comenzar una tarea. |

Ca3. I check my work for errors before turning it in. | Ca3. Reviso mis respuestas antes de entregarlas. |

Ca4. I avoid jumping to conclusions. | Ca4. Evito sacar conclusiones precipitadas (apresuradas). |

Ca5. I like to be accurate | Ca5. Me gusta ser preciso. |

Intellectual autonomy | Autonomía intelectual |

IA1. Sometimes, I disagree with what my parents or teachers thinks | IA1. A veces estoy en desacuerdo con lo que piensan mis padres y superiores. |

IA2. I think differently from my classmates. | IA2. Pienso diferente que mis compañeros de clase. |

IA3. When someone gives me advice, I like to think it through for myself. | IA3. Cuando alguien me da un consejo, me gusta pensarlo por mi mismo. |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mesurado, B., Vanney, C.E. Assessing Intellectual Virtues: The Virtuous Intellectual Character Scale (VICS). Int J Appl Posit Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-024-00193-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-024-00193-y