Abstract

This study updates and extends upon previous meta-analyses by examining the key antecedents and outcomes within the longitudinal job crafting literature. Using a robust statistical approach that disattenuates correlations for measurement error, we further extend past work by exploring the moderating effect of time on the relationship between job crafting and its key correlates. A systematic literature search gathered all current longitudinal research on job crafting, resulting in k = 66 unique samples in the current analysis. Random-effects meta-analysis was conducted for overall job crafting and also for each individual facet of job crafting dimensions. Results showed that both overall job crafting and the individual facets of job crafting had moderate to strong, positive correlations with all variables included in this analysis, except for burnout and neuroticism which were negatively associated. A similar pattern of findings was largely present for all individual facets of job crafting. The exception to this was decreasing hindering demands crafting that had weak, negative associations with all correlates examined, except for burnout where a moderate, positive association was found. Findings from the moderation analysis for work engagement, job performance, and job satisfaction showed that although there was a clear downward trend of correlational effect sizes over time, they did not reach significance. The current study contributes to the job crafting literature by advancing previous meta-analyses, demonstrating the effect that job crafting has on positive work outcomes for both the employee and organisation over time. We conclude by exploring the implications for future research and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Job crafting (Tims & Bakker, 2010; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001) is a job design approach that employees use to modify their work so that it better aligns with their values, motives, and needs, thereby promoting wellbeing and flourishing at work (Frederick & VanderWeele, 2020). In the face of ongoing organisational change and uncertainty, specifically through modern advancements which have fostered a more digitalised and flexible workplace, recent research has shown that employee-driven job redesign behaviours such as job crafting, offer a promising practical alternative to previously used traditional employer-led, top-down job re-design approaches (Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019; Rudolph et al., 2017). Previous reviews have synthesized the existing research on job crafting to understand the benefits and implications of job crafting for both employees and organisations (Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019; Rudolph et al., 2017). However, we estimate that as much as 50–55% of the current literature on job crafting is cross-sectional, thus not making it possible to empirically discern whether job crafting is a temporal antecedent or an outcome of the variables examined.

In addition to experimental research, which is often time-consuming and expensive to conduct, longitudinal research is one possible methodological design that can be used to establish associations between variables over time, and determine the temporal order between variables, providing a stronger base for causal inference. To date, there have been two meta-analyses that aggregate longitudinal research on employee job crafting behaviour (Frederick & VanderWeele, 2020; Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019). These reviews combine the literature on job crafting within different work contexts (i.e., the settings or factors that influence the nature of work) and examine the effect this has on work content (i.e., factors that are controlled by the employee including the job demands and resources). Yet these reviews either contain effects that are biased downward by measurement error (Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019), or contain effect sizes that are difficult to interpret due to the statistical aggregation across multiple different research designs (e.g., experimental, time-lagged designs; Frederick & VanderWeele, 2020). Thus, the first objective of the current study is to build upon the extant longitudinal job crafting literature and use psychometric meta-analysis to establish effect size estimates that are more easily interpretable. Second, we aim to examine the moderating effect of time on the relationship between job crafting and key correlates. In doing this, we provide stronger evidence to draw temporal inferences between job crafting and the commonly measured variables in the literature, and furthermore, provide insight into the long-term correlates of job crafting, an area which has received limited attention.

The remainder of the introduction is structured as follows. First, we outline the key conceptualisations present in job crafting research. Next, we review the current job crafting literature including existing meta-analytical reviews of job crafting. Finally, we examine time lag as a moderator in this analysis, that then leads to the aims and main research questions for this analysis.

1 Theory and Research Questions

1.1 Job Crafting

Job crafting sits within the field of positive psychology (Seligman, 2002), specifically positive organisational scholarship (Wrzesniewski, 2003) which focuses on interventions aimed at promoting and enhancing employee wellbeing, rather than preventing and/or treating illbeing. Positive psychological interventions like job crafting, aim to cultivate positive feelings, behaviours and cognitions in participants to have an overall positive effect on wellbeing (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Although different approaches exist within the job crafting literature, the two most common approaches are the role-based approach (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001) and the resources-based approach (Tims & Bakker, 2010). In the role-based approach, Wrzesniewski and Dutton (2001) reviewed the literature on proactive job behaviour and suggested that employees can make changes to their work environment in three ways: 1) by altering the scope, number, sequence, or type of tasks, known as task crafting; 2) by adapting the quality and/or amount of interaction and human connection at work known as relational crafting; and 3) by reframing how they perceive the tasks within it, known as cognitive crafting. Tims and Bakker (2010) utilized the job demands and resources model (JD-R; Bakker & Demerouti, 2007) to define job crafting. This model suggests that employees seek to increase their job resources at work, while working to reduce problematic job demands. They refined this idea into four dimensions: 1) increasing structural job resources crafting (e.g., crafting more autonomy, and opportunities to develop oneself); 2) increasing social job resources crafting (e.g., crafting more social connections and support from colleagues); 3) increasing challenging job demands crafting (e.g., crafting more tasks and job responsibilities); and 4) decreasing hindering job demands crafting (e.g., crafting ways to have fewer emotional and cognitive demands). While there is much overlap between both perspectives, the omission of cognitive crafting from the Tims and Bakker’s (2010) model, as well as the lack of distinction between expansion (i.e., expanding the scope of the job by increasing job resources) and contraction (i.e., narrowing the scope of the job by decreasing demands) oriented behaviours regarding Wrzesniewski and Dutton’s (2001) task, relational and cognitive crafting, has let to further refinements and the theoretical integration of both models (Bindl et al., 2019; Zhang & Parker, 2019).

More recent models of job crafting are underpinned by regulatory focus theory (Higgins, 1997), and are thus known as, ‘promotion and prevention crafting’ (PPC; Bindl et al., 2019; Zhang & Parker, 2019) or as ‘approach and avoidance crafting’ (Bruning & Campion, 2018). Promotion-focused job crafting (i.e., altering the job to increase positive outcomes), is geared toward pleasure attainment and employees obtaining and creating favourable outcomes to bring about change (Higgins, 1997; Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019). Such an approach aligns with increasing job resources, challenging job demands, and expansion-oriented task, relational and cognitive crafting aspects of previous job crafting models (Slemp & Vella-Brodrick, 2013). Prevention-focused job crafting (i.e., altering the job to reduce negative outcomes) is associated with the avoidance of pain, and reflects people’s need for safety, security and the avoidance of negatives states where needs are not satisfied (Higgins, 1997; Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019). Prevention crafting aligns with decreasing hindering job demands, and contraction forms of task, relational and cognitive crafting (Bindl et al., 2019; Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019). By combining the previous conceptualisations of job crafting, this new model of promotion and prevention crafting encompasses both the tangible and intangible changes that employees can create in work boundaries. This approach allows for a clearer definition of job crafting behaviour, thereby creating a stronger model for future research.

Despite the varying conceptualisations, published literature on job crafting has grown considerably over the last ten years. Much of this growing interest is due to the substantial research showing the benefit of job crafting on individual work outcomes such as work engagement, job satisfaction, wellbeing (Rudolph et al., 2017), job performance (Bohnlein & Baum, 2020) and burnout (Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019). While certain work characteristics such as work experience (Niessen et al., 2016) and job autonomy (Sekiguchi et al., 2017) may present more opportunities for employees to craft their job and thus facilitate job crafting behaviour, typically, research has shown that the positive effect of job crafting is consistent across a range of organisational contexts and cultures, suggesting that all employees may be able to benefit from crafting their job despite their occupation or working condition. Furthermore, the collective evidence suggests that job crafting is associated with benefits not just for individual job crafters, but also work teams and organisations. For instance, studies have shown that team job crafting is positively associated with individual performance (Tims et al., 2013), team performance (McClelland et al., 2014), and team innovativeness (Seppala et al., 2018). Similarly, job crafting is positively associated with organisational citizenship behaviour (Guan & Frenkel, 2018; Shin & Hur, 2019), organisational commitment (Wang et al., 2018), and negatively associated with turnover (Esteves & Lopes, 2017; Vermooten et al., 2019; Zhang & Li, 2020), which, if we accept these reflect causal relationships, can lead to substantial financial benefits for organisations (Oprea et al., 2019).

Despite such research findings, much of the current literature on job crafting is cross-sectional, which poses some challenges for the field (Rindfleisch et al., 2008). Although cross-sectional research is beneficial in giving us a snapshot of the association between variables (Levin, 2006), there are two primary limitations that pertain to this study design. First, it is more prone to common method variance (CMV; i.e., the systematic method error due to the use of a single rater or source; Podsakoff et al., 2003), which means effect sizes are generally biased upwards. Second, due to a single measurement at one point in time, cross-sectional data places constraints on the ability to infer the direction of associations (Rindfleisch et al., 2008). Our estimates reveal that around 52% of the current research on job crafting is cross-sectional in nature, suggesting that concerns regarding the lack of interval validity in cross-sectional research leading to potentially inflated associations, may be applicable to the job crafting literature (Ostroff et al., 2002). For instance, despite overwhelming evidence showing a positive, moderately strong relationship between job crafting and work engagement in cross-sectional research (Rudolph et al., 2017), there have been smaller and more varied effects among intervention studies (Oprea et al., 2019), and randomized control trials (Sakuraya et al., 2020). Thus, to confirm findings from cross-sectional research and to attain a more accurate representation about how job crafting is associated with its key correlates, insights from more sophisticated research designs that help reduce these limitations are needed.

One of the main ways that researchers recommend reducing the threat of CMV bias is by gathering data over multiple time periods (Ostroff et al., 2002; Podsakoff, 2003; Rindfleisch et al., 2008). Fortunately, there have been numerous individual longitudinal studies conducted within the job crafting literature to determine the key outcomes of job crafting using such designs. Although there are some exceptions, findings amongst longitudinal studies also lend support to the hypothesis that job crafting predicts future positive work outcomes, such as person-job fit, meaningfulness, flourishing, job performance, and job satisfaction (Cenciotti et al., 2017; Dubbelt et al., 2019; Kooij et al., 2017; Moon et al., 2018; Robledo et al., 2019; Tims et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). There are currently two meta-analyses that have examined longitudinal literature on job crafting (see Frederick & VanderWeele, 2020; Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019). Lichtenthaler and Fischbach (2019) found that prevention-focused job crafting at Time 1 had a positive relationship with work engagement and a negative relationship with burnout at Time 2. They also found an inverse relationship with prevention-focused job crafting, which showed a negative relationship with work engagement, and positive relationship with burnout at Time 2. Using Tims and Bakker’s (2010) framework, Frederick and VanderWeele (2020), found a positive relationship with job crafting at Time 1 and work engagement at Time 2.

However, while this evidence is promising, these reviews contain methodological limitations that warrant a new meta-analysis to help overcome them. For instance, the statistical analysis used to calculate the meta-analytic correlations in Lichtenthaler and Fischbach (2019) does not correct for measurement unreliability in the predictor or criterion, which may lead to a downward bias in effect sizes (Schmidt & Hunter, 2015; Wiernik & Dahlke, 2020). Similarly, Frederick and VanderWeele’s (2020) meta-analysis is limited insofar as it included both observational longitudinal studies, as well as intervention studies, in the same analysis. Because results from different study designs tend to differ systematically, this may lead to increased, as well as artificially introduced, heterogeneity (Higgins et al., 2019). Thus, such approaches may serve to establish effect size estimates that are some what difficult to interpret. In meta-analyses, it is important to take account of the fact that experimental studies, such as randomized control trials (RCTs) of intervention studies, generate effect sizes in fundamentally different ways than do observational studies (Borenstein et al., 2009; Deeks et al., 2019). For instance, effects from RCTs (for quasi-experimental trials) are generated by comparing the degree to which groups change over time, whereas observational studies generate effects by quantifying the strength of association between variables. Another notable difference is that in intervention studies, participants are actively trained in job crafting behaviours, whereas in observational studies, participants are untrained and observed in their natural work setting (Borenstein et al., 2009). Because both research designs are used to examine fundamentally different types of research questions, we suggest that it a new meta-analysis is needed so that so that study designs can be separated during the analysis (Higgins et al., 2019).

In sum, these issues suggest that a new investigation on longitudinal studies is needed to determine true effect sizes within this literature. In doing this, improved accuracy on the actual strength of association between job crafting and its key antecedents and outcomes will be identified.

1.2 Time Lag as a Possible Moderator of Effects

In addition to building upon previous meta-analyses, we also aim to generate insight into the effect of time on the relationships between job crafting and its key outcomes. Previous research suggests that, in addition to reducing CMV, longitudinal research allows one to examine the way in which the relationships change as a function of time (Ford et al., 2014). This has long been recognized in the job crafting literature (e.g., Oprea et al., 2019; Rudolph et al., 2017), yet there has been little consideration to the effect of time lags on effect sizes. Such a situation is unfortunate as time lags over which variables are measured are very likely to influence effect size magnitudes. Thus, to better understand whether job crafting is stable over time in longitudinal research, the optimal time lag must be considered. Without this insight, drawing conclusions about the stability of job crafting over time may be inaccurate without also taking into the account the specific time period in which stability is measured. Similarly, in cases where experimental manipulation is not possible, a proxy for understanding causal processes shows that one variable (e.g., job crafting) is able to predict later levels of a presumed outcome (e.g., work engagement; Card, 2019). An understanding of these predictive relations over time are critical goals in cumulative science, which we address here.

Given the above, the aim of the current study was to address two research questions:

-

Research Question 1: What are the most prevalent antecedents and outcomes of the longitudinal job crafting literature, and how strongly is job crafting related to these variables?

-

Research Question 2: To what extent does time lag influence the strength of relationships between job crafting and its key antecedents and outcomes?

In addressing these research questions, we aim to overcome existing methodological limitations present in the literature. In contrast to existing meta-analyses which use longitudinal studies and examined work engagement, burnout and performance we contribute to advancing knowledge by examining the key antecedents and outcomes of job crafting that have been studied in the literature to date, rather than focusing on a select few. Finally, in order to further advance the field of job crafting, we examine the moderating effect of time lag.

2 Method

2.1 Literature Search Strategy

The search strategy was developed to retrieve all possible sources on job crafting, from which only longitudinal studies were included in the current meta-analysis. In line with best practice guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Appelbaum et al., 2018; Rudolph et al., 2020; Siddaway et al., 2019), we employed a variety of search strategies to systematically search for studies that examined the longitudinal antecedents and consequences of job crafting. First, to retrieve both published and unpublished sources, we conducted a literature search using eight databases that covered both published and unpublished literature: Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC), Business Source Complete (searched through Ebscohost), Web of Science Core Collection, Medline, PyscINFO, Open Dissertations, ProQuest Theses and Dissertations, and Scopus. Our search covered all years to April, 2020. In line with literature search strategies recommended by Harari et al. (2020), we consulted a university librarian to help select the most relevant databases and also to select search terms for our literature search.

In line with current conceptions of job crafting (Slemp & Vella-Brodrick, 2013; Tims et al., 2012; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001), we ran the search using the following base terms: “job”, “task”, “relational”, “cognitive”, “increasing structural demands”, “increasing social job resources”, “increasing challenging job demands”, “decreasing hindering job demands,” which were combined with “crafting” using the Boolean operator “AND”. This was done to ensure that the search only returned sources that had at least one of the base terms, as well as “crafting” in the title, abstract or key words. Second, we searched Google Scholar for sources that cited papers that are associated with the most commonly used measures of job crafting (Slemp & Vella-Brodrick, 2013; Tims et al., 2012). Third, we examined the reference lists of key meta-analyses for relevant longitudinal studies.

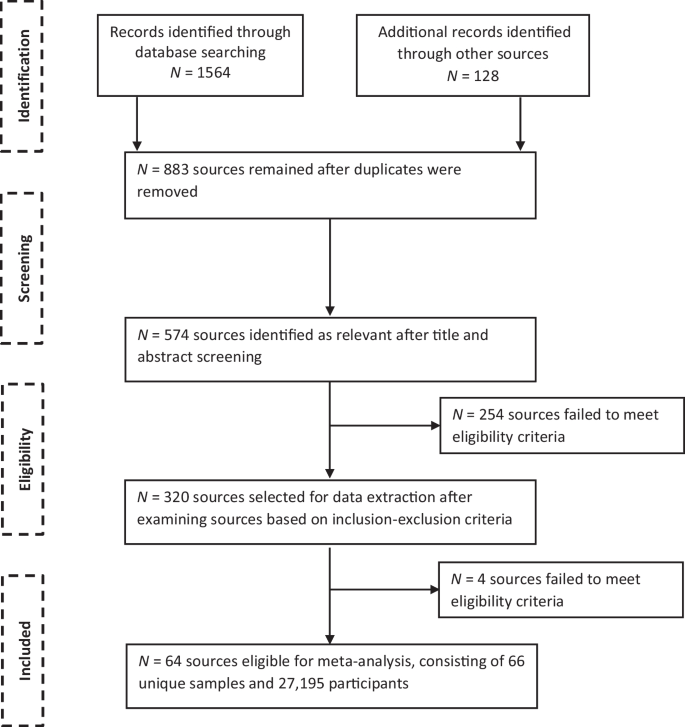

In total, our search process returned 1,692 sources, from which 883 remained after duplicates were removed (see Fig. 1). We first assessed the relevance of the source using the title and abstract, and subsequently further screened sources using the full text and our inclusion criteria (outlined below). This process yielded 320 empirical studies on job crafting, of which 68 were identified as longitudinal studies that met our inclusion criteria. Because Schmidt and Hunter (2015) suggested we need to identify any studies that may have duplicate sampling, as meta-analytic procedures are sensitive to the violation of the assumption of sample independence, in the final step of our screening we used the recommended procedures outlined in Wood (2008) to identify studies with duplicate samples. In doing this, we identified seven studies which used duplicate samples (e.g., Kim & Beehr, 2018, 2019, 2020). Where necessary, if the studies that identified as duplicates examined the same outcomes, we only included the earliest or ‘original’ sample in our analysis, as recommended by von Elm et al. (2004, p. 975). However, we included duplicates in some analyses if there was no overlap in the variables studied. Overall, after applying these criteria we were left with 64 studies, three of which were unpublished (k = 66 independent samples, combined N = 27,195).

2.2 Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they satisfied the following criteria: (a) the study directly measured and reported overall job crafting or a facet of job crafting (i.e., task crafting, relational crafting, cognitive crafting, increasing structural resources, increasing social resources, increasing challenging demands, decreasing hindering demands, increasing quantitative job demands, and physical job crafting), and the relevant antecedent or outcome; (b) the study was written in English; (c) the study contained primary data; (d) the full text was readily available; (e) job crafting was empirically measured using a known job crafting scale (see Table 1 in Rudolph et al., 2017 for a list of known measures in the job crafting literature); (f) the study has at least two waves of measurement; and (g) the study has at least a one month time lag between waves of measurement. This last criterion was set on the basis of Dormann and Griffin (2015), who used cross-lagged regression coefficients of both direct and reciprocal relationships, to determine the optimal time lag that will have the highest chance to detect an effect size if one exists for two waves of measurement. Findings from this study showed that ‘shortitudinal’ research with around approximately 1 month time lag (24 days), was found to be the minimal optimal length. Thus, studies with shorter time lags, such as daily diary studies and shorter longitudinal research, were excluded from the study.

2.3 Study Coding and Data Transformations

All studies were manually coded using an established coding template. The studies were coded for (a) the sample size, (b) the zero-order correlation coefficient (r) between job crafting and the relevant correlate variable, (c) the reliability of job crafting measure (Rxx), (d) the reliability of correlate measure (Ryy), (e) the scale used to measure job crafting, (f) the country in which the study was published, (g) the publication status of the paper (published vs unpublished), (h) the number of waves of measurement, (i) the time lag between waves (in months), (j) occupational status of participants, and (k) the study design.

Where necessary, we used the data transformation procedures described by Schmidt and Hunter (2015) to establish composite correlations for studies that only reported correlations at a facet level, but not the corresponding aggregate to reflect the overall construct. We did this by combining the correlation coefficients using their intercorrelations between the variable facets. We also established corresponding composite reliabilities using Mosier (1943) formulas. We calculated the composite to determine the overall job crafting construct. Based on regulatory focus theory, we did this to establish composites for approach and avoidance crafting, using a similar approach to Lichtenthaler and Fischbach (2019). Taking this approach meant that decreasing hindering resources crafting was excluded when calculating the overall job crafting composite. Unlike promotion-oriented forms of job crafting, decreasing hindering resources crafting is labelled a prevention form of job crafting, and often viewed as a protective mechanism when job demands are high (Demerouti, 2014). As such, the direction of association between the correlates of decreasing hindering resources crafting is often the inverse when compared to promotion crafting. Thus, combining these facets in the same analysis would result in downwardly biased aggregated effect sizes. Where necessary, we also established composite correlations when studies reported only facets of the antecedent or outcome variables.

2.4 Meta-Analytic Procedure

To conduct our meta-analysis, we used the psychometric meta-analysis approach, proposed by Schmidt and Hunter (2015). We conducted our analyses with R Studio (Version 1.4.1717) using the “psychmeta” package (Dahlke & Wiernik, 2019) and the unbiased sample variance estimator. We first calculated a sample-size weighted mean observed correlation between each facet of job crafting and each correlate variable. Next, we estimated the population correlation (\(\overline{\uprho }\)) using artifact (reliability) distributions, which are reported in our supplementary file.

Schmidt and Hunter’s (2015) approach to meta-analysis is based on the random effects model. The advantage of the random effects model is that it allows parameters to vary across studies and does not have strong assumptions about the homogeneity of effect parameters. Thus, random effect meta-analyses determine the mean effect size from an assumed distribution of effect sizes (Borenstein et al., 2010; Hedges & Vevea, 1998; Schmidt & Hunter, 2015), which leads to more accurate and generalizable estimates of effect sizes and confidence intervals (CI; Field, 2003; Schmidt & Hunter, 2015). While the random effects model requires at least three studies, the psycmeta package in R will aggregate effects when two studies are available, so we also report a meta-analytic correlation for all outcomes that had a minimum of two studies available, and also generated the 95% confidence intervals for each estimate.

Heterogeneity was assessed using \(S{D}_{\uprho }\) and the 80% credibility interval (CV). \(S{D}_{\uprho }\) is the corrected standard deviation of the true score correlation and, greater values of \(S{D}_{\uprho }\) suggest greater heterogeneity in meta-analytic associations (Schmidt & Hunter, 2015). We also generated the 80% credibility interval (CV), which provides an estimate of heterogeneity around each effect size. The CV is interpreted such that 80% of the distribution of true correlations (the \(\overline{\rho }\) distribution) falls within this interval (Schmidt & Hunter, 2015).

We summarize the meta-analytic findings by reporting (a) the number of studies in the analysis (k), (b) the combined sample size (N), (c) the “bare bones” meta-analytic correlation (Schmidt & Hunter, 2015) which is the meta-analytic correlation corrected only for sampling error (\(\overline{r }\)), (d) the observed standard deviation (\(S{D}_{r}\)), (e) the residual standard deviation (\(S{D}_{res}\)) for the meta-analytic correlation, (f) an estimate of the true correlation that is corrected for both sampling and measurement error (\(\overline{\uprho }\)), (g) the variance in this estimate (\(S{D}_{\uprho }\)), (h) the observed standard deviation of corrected correlations (\(S{D}_{{r}_{c}}\)), (i) the 95% CI and, (j) the 80% CV for the true correlation parameter. To interpret our effect sizes, we used Bosco et al.’s (2015) empirically established correlational benchmarks for applied psychological research. Specifically, we used benchmarks of |r|= 0.07, 0.16, and 0.32 to indicate the lower-bound thresholds of weak, moderate, and strong, which correspond to the 25th, 50th and 75th percentile, respectively.

2.4.1 Moderator Analysis: Time Lag

In line with our second aim, we conducted moderator analyses using meta-regression to examine whether time lag was related to study-level effect sizes. Time lag was coded as the time (in months) between the measurement of job crafting, or a facet of job crafting, and the correlate of interest. We concluded that the moderator was significant if the 95% CIs for the regression coefficients did not encompass zero (Borenstein et al., 2009).

2.5 Publication Bias Analysis

Although active steps were taken to locate and obtain unpublished data sources, it is possible that our findings could still be subject to publication bias. Thus, in line with recommendations by Field et al. (2021) we conducted a thorough analysis to assess whether publication bias was present in our findings, which we considered in several ways. First, we visually analysed funnel plots which displayed effect sizes plotted against their standard errors. The distribution of effect sizes on the funnel plots will be asymetrical in the case of biased literatures, which is often caused by having ‘missing’ published studies containing nonsignificant or small effects. Second, we also used Egger’s regression test of funnel plot assymtery to assess the symmetry of the funnel plot (Egger et al., 1997). Finally, Duval and Tweedie’s (2000) trim and fill procedure was used to examine the extent to which ‘missing’ studies would affect the original effect estimates. To ensure that a reasonable distribution of published and unpublished studies were considered, and also because findings from the trim and fill method may be biased for small sample sizes, only variables where k > 10 were considered for the analyses. To run these analyses, we used the free, open source software Meta-Sen (https://metasen.shinyapps.io/gen1/), which provides a comprehensive software platform to examine for sensitivity analyses and outlier-induced heterogenity. All analyses using Meta-Sen are included in our supplementary file.

3 Results

3.1 Antecedents of Job Crafting

As indicated in Table 1, overall job crafting exhibted near-zero, non-significant meta-analytic correlations with most of the demographic variables, except for education (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.10 [95% CI = 0.05, 0.14]; k = 17; N = 7,809), work hours (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.21 [95% CI = 0.15, 0.28]; k = 3; N = 1,013), and experience (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.27 [95% CI = 0.19, 0.35]; k = 2; N = 627), which showed a moderate positive relationship. By contrast, personality factors were moderate to strong antecedents of job crafting, with proactive personality having a positive, strong relationship (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.37 [95% CI = 0.15, 0.58]; k = 6; N = 2,161), and neuroticism having a moderate, negative relationship (\(\overline{\rho }\) = -0.19 [95% CI = -0.40, 0.02]; k = 3; N = 864), on job crafting behaviours. Generally, moderate to strong correlations were observed for different work contexts, except for burnout (\(\overline{\rho }\) = -0.16 [95% CI = -0.17, -0.16]; k = 2; N = 2,320) which had a moderate, negative relationship with job crafting. Of these, positive leadership (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.68 [95% CI = 0.47, 0.90]; k = 6; N = 4,193), HR flexibility (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.48 [95% CI = 0.31, 0.65]; k = 3; N = 1,294), and work engagement (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.46 [95% CI = 0.42, 0.50]; k = 3; N = 1,018) were the strongest antecedents of job crafting. Strong positive correlations were also observed between all motivational factors and job crafting.

Similar to overall job crafting, near-zero, non-significant correlations were found between demographic variables and task, relational and cognitive crafting (see Table 2). The exception to this was the correlation found between age (relational crafting: \(\overline{\rho }\) = -0.07 [95% CI = -0.10, -0.05]; k = 3; N = 1,802; cognitive crafting: \(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.07 [95% CI = -0.01, 0.14]; k = 3; N = 1,802) and gender (relational crafting: \(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.06 [95% CI = 0.02, 0.10]; k = 4; N = 2,048; cognitive crafting: (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.06 [95% CI = 0.05, 0.07]; k = 3; N = 1,802), which exhibited a weak negative, and a weak positive relationship, respectively. These findings suggest that females engaged in more relational and cognitive crafting than men. Social support was a strong, positive antecedent to job crafting behaviour for both task (\(\overline{r }\) = 0.35, k = 1; N = 253) and relational crafting (\(\overline{r }\) = 0.50, k = 1; N = 253). Similarly, self-esteem also exhibited a strong, positive association for both task (\(\overline{r }\) = 0.44, k = 1; N = 138) and cognitive crafting (\(\overline{r }\) = 0.54, k = 1; N = 138). Motivation had a strong positive association with task crafting (\(\overline{r }\) = 0.34, k = 1; N = 426), and similar findings were also found between interdependence and relational crafting (\(\overline{r }\) = 0.32, k = 1; N = 253). Neuroticism had a moderate, negative association with cognitive crafting (\(\overline{r }\) = -0.10, k = 1; N = 253).

All demographic variables had non-significant associations with the facets of job crafting defined by Tims and Bakker (2010) (see Table 3). Work engagement was one of the strongest antecedents across all facets of job crafting, and had positive associations with structural resources crafting (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.45 [95% CI = 0.39, 0.51]; k = 8; N = 4,570), social resources crafting (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.31 [95% CI = 0.27, 0.35]; k = 3; N = 2,607), and challenging demands crafting (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.54 [95% CI = 0.48, 0.61]; k = 3; N = 2,607). By contrast, there was a moderate negative relationship between work engagement and hindering demands (\(\overline{\rho }\) = -0.27 [95% CI = -0.31, -0.15]; k = 3; N = 2,608). Burnout also had consistently moderate, negative associations with all of Tims et al.’s (2012) facets of job crafting (structural resources crafting: \(\overline{\rho }\) = -0.21 [95% CI = -0.31, -0.12]; k = 2; N = 2,320; social resources crafting: \(\overline{\rho }\) = -0.10 [95% CI = -0.15, -0.04]; k = 2; N = 2,320; challenging demands crafting: \(\overline{\rho }\) = -0.17 [95% CI = -0.23, -0.11]; k = 2; N = 2,320), except for hindering demands crafting which exhibited a strong, positive association with burnout (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.40 [95% CI = 0.30, 0.51]; k = 2; N = 2,320). Workaholism exhibited low to moderate, positive associations with all of Tims et al.’s (2012) facets of job crafting (structural resources crafting: \(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.11 [95% CI = 0.07, 0.15]; k = 3; N = 2,607; social resources crafting: \(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.09 [95% CI = 0.01, 0.18]; k = 3; N = 2,607; challenging demands crafting: \(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.22 [95% CI = 0.16, 0.29]; k = 3; N = 2,607), however this association was not significant for hindering demands crafting (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.13 [95% CI = -0.02, 0.27]; k = 2; N = 2,320). Moderate, positive associations were observed between psychological capital and social resources crafting (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.20 [95% CI = 0.00, 0.19]; k = 2; N = 1,935). and challenging demands crafting (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.25 [95% CI = 0.13, 0.37]; k = 2; N = 1,260).

3.2 Outcomes of Job Crafting

Of note in Table 1 is the strong positive association between job crafting and different job attitude outcomes, with work engagement (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.46 [95% CI = 0.40, 0.52]; k = 14; N = 6,493) and meaningfulness (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.52 [95% CI = 0.22, 0.83]; k = 3; N = 957) showing the strongest effects. In contrast, a moderate negative meta-analytic correlation emerged between burnout and job crafting (\(\overline{\rho }\) = -0.22 [95% CI = -0.27, -0.18]; k = 4; N = 1,523). A strong, moderate, positive association was found between job crafting and performance (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.28 [95% CI = 0.22, 0.34]; k = 15; N = 6,193). Very strong positive correlations were found between job crafting and self-efficacy (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.58 [95% CI = 0.45, 0.71]; k = 3; N = 947) and psychological capital (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.44 [95% CI = 0.29, 0.58]; k = 2; N = 1,289).

Generally task, relational, and cognitive crafting had moderate to strong positive associations with job attitudes, with need-supply fit and work-family balance having the strongest associations with relational crafting (work-family balance: \(\overline{r }\) = 0.19, k = 1; N = 1,411) and cognitive crafting (need-supply fit: \(\overline{r }\) = 0.32, k = 1; N = 118). A moderate, negative relationship existed between relational crafting and job dissatisfaction (\(\overline{r }\) = -0.15, k = 1; N = 246). By contrast, only a weak relationship existed between task crafting and work-family balance (\(\overline{r }\) = 0.08, k = 1; N = 1,411) and job dissatisfaction (\(\overline{r }\) = 0.04, k = 1; N = 1,411). Task crafting had a moderate, positive association with creativity (\(\overline{r }\) = 0.15, k = 1; N = 86).

Work engagement and job satisfaction had strong, positive associations with all of Tims et al.’s (2012) facets of job crafting, except for hindering demands crafting which had near-zero, non-significant associations with these outcomes (work engagement: \(\overline{\rho }\) = -0.03 [95% CI = -0.11, 0.05]; k = 7; N = 1,797; job satisfaction: \(\overline{\rho }\) = -0.04 [95% CI = -0.20, 0.12]; k = 5; N = 1,670). A similar pattern of results was observed for job performance (structural resources crafting: \(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.33 [95% CI = 0.25, 0.41]; k = 5; N = 1,719; social resources crafting: \(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.13 [95% CI = 0.06, 0.21]; k = 5; N = 1,313; challenging demands crafting: \(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.28 [95% CI = 0.13, 0.42]; k = 6; N = 1,893; hindering resources crafting: \(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.05 [95% CI = -0.07, 0.17]; k = 6; N = 2,059). Similarly but conversely, all of Tims et al.’s (2012) facets of job crafting had moderate to strong, negative associations with burnout, except hindering demands crafting which exhibited a positive, yet non-significant association with burnout (\(\overline{\rho }\) = 0.19 [95% CI = -0.08, 0.46]; k = 3; N = 1,192). Generally, all of Tims et al.’s (2012) facets of job crafting, except decreasing hindering resources crafting, had a significant, moderate to strong correlation with other commonly measured job attitudes, including organisational citizenship behaviour (structural resources crafting: \(\overline{r }\) = 0.32, k = 1; N = 288; challening demands crafting: \(\overline{r }\) = 0.27, k = 1; N = 288) and psychological captial (structural resources crafting: \(\overline{r }\) = 0.54, k = 1; N = 940). The exception to this was the association between social resources crafting and psychological empowerment, which exhibited a near-zero relationship (\(\overline{r }\) = 0.03, k = 1; N = 320). By contrast, decreasing hindering resource crafting had near-zero to small, negative correlations with job attitudes such as flourishing (\(\overline{r }\) = -0.03, k = 1; N = 443) and adaptivity (\(\overline{r }\) = -0.07, k = 1; N = 368).

3.3 Moderator Analysis: Time Lag

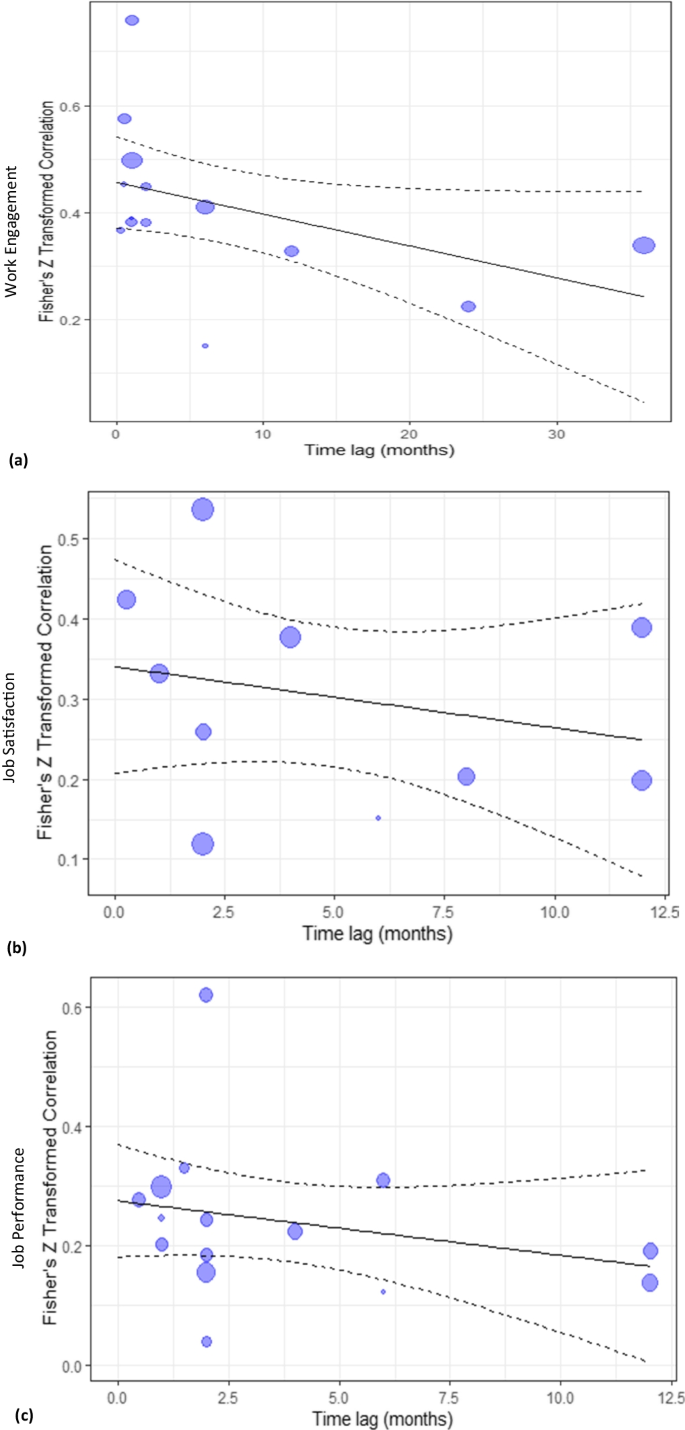

We used meta-regression to examine whether the aforementioned correlations were related to the time lag between measurements. To do this, we used z-transformed effect sizes and examined whether these changed as a function of time-lag. In line with Cochrane guidelines (Deeks et al., 2019), we only conducted the meta-regression when there were at least 10 effect sizes for each outcome variable, which limited our analyses to work engagement, job satisfaction and job performance, which were all outcomes of overall job crafting. To aid our interpretation of these analyses, we generated bubble plots to convey overall trends in the associations over time (see Fig. 2 below).

As displayed in Fig. 2, a clear downward trend in correlation effect sizes can be observed across all of these criteria, suggesting that effect sizes attenuate as a function of time lag. However, results did not reach significance. The moderation analysis with work engagement,while trending downwards, was not significant (k = 14, SE = 0.0033, β = − 0.006, CI = [− 0.0124, 0.0005]), as the confidence intervals encompass zero (see Fig. 2a). Moderation also did not reach significance between job crafting and job satisfaction (k = 10, SE = 0.0105, β = − 0.0076, CI = [− 0.0283, 0.0130]), or job peformance (k = 15, SE = 0.009, β = − 0.0091, CI = [− 0.0269, 0.0086]) (see Fig. 2b and c).

3.4 Publication Bias

Within our supplemental material (SM), SM Table 1 displays the sensitivity analysis results for all correlates of job crafting that had 10 or more effect sizes. Again, the correlates that fit this criterion were work engagement, job satisfaction and job performance, which were all outcomes of overall job crafting.

An assessment of SM Table 1 suggests that outliers did not threaten the observed meta-analytic findings. No outliers were found for job satisfaction, and one outlier was removed for both work engagement and job performance. However, an examination of the adjusted meta-analytic mean estimates shows a similar value for the corresponding original mean estimate before the outlier was removed. Specifically, the absolute differences between the original meta-analytic estimate and adjusted estimate did not exceed 20% of the original estimate (Field et al., 2021). Hence, results of our sensitivity analyses suggest that outliers did not threaten the observed meta-analytic results.

Similarly for publication bias, the sensitivity analyses suggest that the meta-analytic estimates between overall job crafting and work engagement, job satisfaction and job performance were not threatened by publication bias (see SM Table 1). In fact, results of the adjusted meta-analytic effect sizes suggest that, if anything, the original effect size was underestimated, as indicated by typically stronger, not weaker, effects after accounting for publication bias. Hence, the sensitivity analyses indicate that our original meta-analytic estimates are likely conservative estimates of the observed data and are not threatened by outliers or publication bias.

4 Discussion

Our aim in the present meta-analysis was to uncover key antecedents and outcomes in the longitudinal job crafting literature, and determine the strength of association between these variables. We also aimed to examine whether the lag between job crafting and its key correlates moderated the strength of the relationship between these variables. In the following sections, we summarize and interpret our findings, discuss relevant limitations, and suggest directions for future research.

4.1 Study Findings and Contributions

Our results contribute to the literature in several ways. First, we extend previous meta-analyses that only included a select few variables, by examining all the key variables within longitudinal job crafting research, and reveal that certain antecedents have a meaningful relationship with overall job crafting. Individual demographic characteristics (i.e., education levels, experience and working hours), psychological factors (i.e., motivation and psychological capital), and personality traits were all found to be positively associated with overall job crafting behaviour. Our findings are consistent with human capital theory, which suggests that older employees, as well as more experienced, educated, and longer-tenured employees possess greater accumulated knowledge about their job, and are more readily able to find opportunities where they can craft their job, and are thus in a better position to do so. Unsurprisingly, our findings also revealed that employees who have more traits associated with a proactive personality were also more likely to engage in job crafting. Proactive employees generally have higher levels of initiative, are able to overcome barriers, identify opportunities, and persevere to achieve their goals, thus making them more likely to engage in job crafting behaviour (Bakker et al., 2012; Bindl & Parker, 2011; Parker et al., 2010). However, a point of difference between findings from this study and previous meta-analyses, was that gender, age and tenure were found to be non-significantly associated to overall job crafting, whereas Rudolph et al. (2017) found a significant effect. However, the association between gender and relational and cognitive crafting was the exception to these results, with our findings indicating that women tended to engage in relational and cognitive crafting more than men.

Our findings revealed that, in addition to positive traits (e.g., proactive personality), negative traits were also found to be associated with job crafting behaviour. Specifically, workaholism was found to be a positive, weak to moderate, antecedent of all facets of job crafting, except decreasing hindering demands crafting. This may be because, workaholics have been found to self-impose demands on themselves and choose to take up new challenges and tasks at work, whilst seeking to expand their capabilities at work, as well as manage their job demands (Schaufeli et al., 2008). These characteristics of workaholism overlap with Tims et al.’s (2012) dimensions of job crafting, and our weak to moderate associations reflect this. However, workaholism was positively associated with decreasing hindering demands crafting, as workaholics have been found to do whatever is important at work, including avoiding demanding tasks or people that may be potential obstacles in achieving their work goals (Hakanen et al., 2018). Our findings are consistent with previous research which has found that other negative traits, such as obsessive passion examined in previous research, is also positively associated with job crafting, thereby further supporting existing theoretical propositions stating that job crafting does not yield only ‘good’ outcomes for both the employee and organizations (Slemp et al., 2021; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Instead, job crafting contains both positive and negative qualities, and certain forms of job crafting, potentially through workaholism, could entice maladaptive outcomes such as burnout (Petrou et al., 2015; Tims et al., 2015). Thus, future job crafting interventions should consider the potentially negative effects that job crafting could have, and attempt to limit this by educating employees on ways in which they can reduce maladaptive forms of job crafting.

Our results are consistent with Wang et al.’s (2020) previous meta-analytic findings, which suggest that work context and social factors serve key antecedent functions for job crafting. Specifically, our findings reveal that working environments that are more flexible and supportive, in addition to the presence of positive leadership styles, may enhance an individual’s motivational state to encourage employees to craft their job (Parker et al., 2010; Zhang & Parker, 2019). Our findings reflect this notion as, positive leadership styles (e.g., empowering and charismatic leadership), HR flexibility, feelings of autonomy and social support, were all found to be strong, positive antecedents of overall job crafting behaviour. These findings have practical implications in terms of emphasising the need to incorporate the organisation within future job crafting interventions, as this may be more successful in encouraging and motivating employees to craft their job and make a proactive effort to improve their work wellbeing.

An interesting finding was that work engagement and burnout were both antecedents and outcomes of overall job crafting and for each facet of Tims et al.’s (2012) job crafting model. Specifically, lower burnout and higher work engagement was significantly associated with later job crafting behaviour, but were also possible outcomes of job crafting. Indeed, it is possible that a reciprocal relationship exists between job crafting and burnout/work engagement, such that more engaged/less burned out employees are more/less likely to engage in job crafting in the first place, thereby influencing later engagement and burnout. While we suggest that this is a possibility, the literature in its current form does not allow for such an analysis, and this should be an aim for future research to address. Nevertheless, our findings extend previous meta-analyses by highlighting that burnout and engagement serve as both antecedents and outcomes of job crafting, raising the possibility of a reciprocal relationship.

Although our findings align with previous meta-analyses that showed job crafting to be positively associated with work engagement and negatively with burnout at later time points (Frederick & VanderWeele, 2020; Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019), there were some differences in effect sizes. The meta-analytic correlation between job crafting and later work engagement was significantly stronger than that found in Frederick and VanderWeele (2020). This may be because, Frederick and VanderWeele’s (2020) meta-analysis combined longitudinal and experimental research together when applying the meta-analysis. As interventions typically rely on successfully increasing employee job crafting beyond an existing level that they already display, typically unconsciously, intervention studies are likely to yield smaller effect sizes than observational studies insofar as effects are contingent on the difference between pre-post levels of job crafting, rather than capturing natural variance aggregating correlations (Bakker et al., 2019; Diener et al., 2021). Consequently, combining interventions with longitudinal research may be pulling the meta-analytic effect size downwards, thereby making them smaller than what would be found when observing job crafting in its natural form in organisations. As we only included longitudinal research in our meta-analysis, this may explain why we found much stronger correlational estimates for work engagement than Frederick and VanderWeele (2020).

Although Lichtenthaler and Fischbach (2019) did not correct for measurement error in their meta-analysis, we found similar effect sizes for both work engagement and burnout. This suggests that while Lichtenthaler and Fischbach’s (2019) meta-analytic findings were fairly accurate in their estimates, it was necessary to conduct our meta-analysis to show that their findings are not simply an artifact of CMV or measurement error. This is because, in our meta-analysis, we limited both upward bias which is created through CMV by including only longitudinal research in our analysis. At the same time, we also control for downward bias by imposing corrections for measurement error, thereby resulting in the most accurate effect sizes. Thus, these consistent findings allude to the robustness of the relationship that job crafting has with work engagement and burnout, and further suggests that the measures used in job crafting research are consistent with the way they associate with other variables.

Decreasing hindering job demands crafting was the only dimension of job crafting that had little to no association with any of the correlates included in our findings. Although it is expected that reducing problematic job demands through decreasing hindering demands crafting is thought to have a positive influence on job outcomes, these findings support previous speculations which suggest that decreasing hindering demands may signal a withdrawal from work (Demerouti, 2014). For example, previous research has found that decreasing hindering demands is positively related with exhaustion (Petrou, 2013) and has detrimental effects on motivation (Petrou et al., 2012). Thus, it is possible that in instances where employees are withdrawing from work, decreasing demands may potentially be an ineffective strategy to improve job attitudes and performance at work (Demerouti, 2014).

While prior intervention research suggests that job crafting effects likely wane over time (Sakuraya et al., 2016; van Wingerden et al., 2017), our non-significant findings from the moderation analysis indicate that the effect of time on correlation magnitudes is likely to be modest. These findings contribute to the limited literature that examines the long-term effects of job crafting. Longitudinal research allows for the examination of the dynamic nature of job crafting over time that would not otherwise be possible with cross-sectional research. In doing this, more precise estimates between job crafting and other variables can be found, leading to more accurate conclusions about the effect of job crafting. It should be noted that while we were interested in the moderation effect of time lag on both the antecedents of job crafting as well as how job crafting relates to its outcomes, there were only sufficiently available studies for the outcomes, which we tested. However, it is possible that the association between certain antecedents and later job crafting behaviour may also change over time, and thus should be explored in future research.

4.2 Limitations and Future Directions

The current study includes a number of limitations that should be considered. First, one limitation of meta-analyses is that it is dependent on the quality, scope and number of studies present in the existing literature. Also, the inclusion of questionnaire studies in the current meta-analysis may potentially make it more susceptible to the traditional limitations of self-report questionnaires such as response bias, monomethod bias, and method variance (Razavi, 2001). Although interest and research on job crafting continues to grow, some of our meta-analytic findings were based on a small number of studies, which was further limited due to the focus of time-lagged correlations within the job crafting literature. Although only two studies are needed to conduct a meta-analysis (Valentine et al., 2010), this may have increased the possibility that our results for such analyses are influenced by second-order sampling error (Schmidt & Oh, 2013), or by extreme or inflated effect sizes (Turner et al., 2013). Thus, having a larger sample size would allow more power to estimate robust effect sizes. Second, there is not sufficient research that examines Wrzesniewski and Dutton’s (2001) cognitive crafting dimension, and, as such, we were unable to further examine the antecedents and outcomes associated with these dimensions of job crafting. Cognitive crafting is a valuable component of job crafting and is viewed as the facet of job crafting that is most closely aligned with work identity and meaningfulness (Slemp & Vella-Brodrick, 2013; Zhang & Parker, 2019). Employees can achieve greater fit with their work environment by reframing and redefining the way they perceive their work (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001; Zhang & Parker, 2019), even without any physical behaviour change. Thus, it is possible that cognitive crafting may have a significant positive effect on perceived job characteristics, as well as other desirable outcomes including work identity, meaningfulness, and emotions (Berg et al., 2013; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001; Zhang & Parker, 2019), which we were not able to directly test. Research exploring the effect of cognitive crafting on work outcomes, as well as the interaction between behavioural- and cognitive-crafting, would be a valuable avenue for future research.

Third, there is limited research on prevention-oriented job crafting in the current literature. In this study, we defined prevention-oriented job crafting as behavioural changes that employees deploy in their job to reduce negative job demands. However, while Tims et al.’s (2012) measure of decreasing hindering job demands offers a reliable facet of prevention-oriented job crafting, it is only one form of prevention-oriented job crafting and does not include broader job crafting strategies (Bindl et al., 2019). Newer measures are emerging that integrate regulatory focused promotion- and prevention-oriented job crafting with Wrzesniewski and Dutton’s (2001) model of job crafting (Bindl et al., 2019), and offer a way forward in this regard.

Moreover, as findings from this meta-analysis revealed that decreasing hindering demands has potentially maladaptive effects on certain work outcomes, such as burnout, there is limited research exploring when and why these negative outcomes occur. Hu et al. (2020) suggests that employees reduce stress by alleviating or actively removing harmful stimuli, known as active coping, as well as by distancing themselves from the problem, known as withdrawal, which could lead to different outcomes. Active coping behaviour is a more adaptive form of job crafting that results in increased proactive behaviour, whereas employees who withdraw from stressful demands are less likely to engage in adaptive behaviour, which negatively impacts goal-related behaviours and hence leads to negative work-related wellbeing (Hu et al., 2020). Thus, future research should seek to create measures that differentiate between the coping mechanism employees use when engaging in prevention-oriented job crafting behaviour in order to identify the true effect that prevention-oriented job crafting has on individual and organisational outcomes.

While employee characteristics such as tenure and experience were included within this analysis, it did not include other potentially important descriptive variables such as size of the organisation, employee status (i.e., the employee’s position and seniority in an organisation) and specific job type. This is potentially a limitation within the current analysis as previous research has shown that variables such as employee status (Sekiguchi et al., 2017) and organisational rank (Roczniewska & Puchalska-Kaminska, 2017) affect employee job crafting behaviour such that those in higher positions typically craft their job more frequently than those in lower positions within the organisation. Thus, this is an avenue for future research to further understand.

Last, the current meta-analysis examined how job crafting changed over time. However, the nature of work also tends to change and evolve over time, and this change may not be well captured in longitudinal research which generally does not take potential moderators or covariates into account. Thus, future research could examine why changes in job crafting may occur in relation to changes in the work environment.

5 Conclusions

The present study provides a meta-analytical review of the antecedents and outcomes in the longitudinal job crafting literature. From a theoretical standpoint, we advanced on the knowledge of job crafting by remedying methodological shortcomings that were present in several previous meta-analyses. Results from our study revealed that promotion-oriented job crafting has a moderate to strong, positive association with all antecedents and outcomes examined in this analysis, except for burnout where a weak, negative effect was found. However, in most instances, prevention-oriented job crafting was found to be very weakly associated with most of the correlates examined in longitudinal literature, although such a result could be attributed to the limited literature available on this form of job crafting. Furthermore, moderation analyses suggest that effect sizes between job crafting and its key outcomes may attenuate over time, but are unlikely to completely diminish. From a practical standpoint, practitioners may be able to utilise findings from this analysis to highlight the effectiveness of job crafting on positive work outcomes and suggest that there is promise in job crafting as a way to target employee engagement and productivity.

References

Appelbaum, M., Cooper, H., Kline, R. B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Nezu, A. M., & Rao, S. M. J. A. P. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA publications and communications board task force report. The American Psychologist, 73(1), 3.

Bakker, A., Cai, J., English, L., Kaiser, G., Mesa, V., & Van Dooren, W. (2019). Beyond small, medium, or large: Points of consideration when interpreting effect sizes. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 102, 1–8.

Bakker, A., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328.

Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Derks, D. (2012). Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations, 65(10), 1359–1378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712453471

Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 81–104). American Psychological Association.

Bindl, U. K., & Parker, S. K. (2011). Proactive work behavior: Forward-thinking and change-oriented action in organizations. APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol 2: Selecting and developing members for the organization., 567–598. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12170-019

Bindl, U. K., Unsworth, K. L., Gibson, C. B., & Stride, C. B. (2019). Job crafting revisited: Implications of an extended framework for active changes at work. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(5), 605–628. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000362

Bohnlein, P., & Baum, M. (2020). Does job crafting always lead to employee well-being and performance? Meta-analytical evidence on the moderating role of societal culture. International Journal of Human Resource Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1737177

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). When does it make sense to perform a meta-analysis. In Introduction to Meta-Analysis (pp. 357–364).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2010). A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(2), 97–111.

Bosco, F. A., Aguinis, H., Singh, K., Field, J. G., & Pierce, C. A. (2015). Correlational effect size benchmarks. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 431.

Bruning, P. F., & Campion, M. A. (2018). A role-resource approach-avoidance model of job crafting: A multimethod integration and extension of job crafting theory. Academy of Management Journal, 61(2), 499–522.

Card, N. A. (2019). Lag as moderator meta-analysis: A methodological approach for synthesizing longitudinal data. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 43(1), 80–89.

Cenciotti, R., Alessandri, G., & Borgogni, L. (2017). Psychological capital and career success over time: The mediating role of job crafting. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 24(3), 372–384.

Dahlke, J. A., & Wiernik, B. M. (2019). psychmeta: An R package for psychometric meta-analysis. Applied Psychological Measurement, 43(5), 415–416.

Deeks, J. J., Higgins, J. P., & Altman, D. G. (2019). Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta‐analyses. In Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (pp. 241–284): Cochrane Statistical Methods Group

Demerouti, E. (2014). Design your own job through job crafting. European Psychologist, 19(4), 237–247.

Diener, E., Northcutt, R., Zyphur, M., & West, S. G. (2021). Beyond experiments. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 17(4) 1101–1119.

Dormann, C., & Griffin, M. A. (2015). Optimal time lags in panel studies. Psychological Methods, 20(4), 489.

Dubbelt, L., Demerouti, E., & Rispens, S. (2019). The value of job crafting for work engagement, task performance, and career satisfaction: Longitudinal and quasi-experimental evidence. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 28(3), 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1576632

Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463.

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634.

Esteves, T., & Lopes, M. P. (2017). Crafting a calling: The mediating role of calling between challenging job demands and turnover intention. Journal of Career Development, 44(1), 34–48.

Field, A. P. (2003). The problems in using fixed-effects models of meta-analysis on real-world data. Understanding Statistics: Statistical Issues in Psychology, Education, the Social Sciences, 2(2), 105–124.

Field, J. G., Bosco, F. A., & Kepes, S. (2021). How robust is our cumulative knowledge on turnover? Journal of Business and Psychology, 36(3), 349–365.

Ford, M. T., Matthews, R. A., Wooldridge, J. D., Mishra, V., Kakar, U. M., & Strahan, S. R. (2014). How do occupational stressor-strain effects vary with time? A review and meta-analysis of the relevance of time lags in longitudinal studies. Work and Stress, 28(1), 9–30.

Frederick, D. E., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2020). Longitudinal meta-analysis of job crafting shows positive association with work engagement. Cogent Psychology, 7(1), 1746733.

Guan, X. Y., & Frenkel, S. (2018). How HR practice, work engagement and job crafting influence employee performance. Chinese Management Studies, 12(3), 591–607. https://doi.org/10.1108/cms-11-2017-0328

Hakanen, J. J., Peeters, M. C., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2018). Different types of employee well-being across time and their relationships with job crafting. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(2), 289–301.

Harari, M. B., Parola, H. R., Hartwell, C. J., & Riegelman, A. (2020). Literature searches in systematic reviews and meta-analyses: A review, evaluation, and recommendations. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 118, 103377.

Hedges, L. V., & Vevea, J. L. (1998). Fixed-and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 486.

Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond Pleasure and Pain. American Psychologist, 52(12), 1280–1300.

Higgins, J. P., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley.

Hu, Q., Taris, T. W., Dollard, M. F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2020). An exploration of the component validity of job crafting. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology Review, 29(5), 776–793.

Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2018). Can empowering leaders affect subordinates’ well-being and careers because they encourage subordinates’ job crafting behaviors? Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 25(2), 184–196.

Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2019). The power of empowering leadership: Allowing and encouraging followers to take charge of their own jobs. International Journal of Human Resource Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1657166

Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2020). Job crafting mediates how empowering leadership and employees’ core self-evaluations predict favourable and unfavourable outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(1), 126–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2019.1697237

Kooij, D. T., Tims, M., & Akkermans, J. (2017). The influence of future time perspective on work engagement and job performance: The role of job crafting. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(1), 4–15.

Levin, K. (2006). Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evidence-Based Dentistry, 7(1), 24–25.

Lichtenthaler, P. W., & Fischbach, A. (2019). A meta-analysis on promotion- and prevention-focused job crafting. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(1), 30–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2018.1527767

McClelland, G. P., Leach, D. J., Clegg, C. W., & McGowan, I. (2014). Collaborative crafting in call centre teams. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 87(3), 464–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12058

Moon, T. W., Youn, N., Hur, W. M., & Kim, K. M. (2018). Does employees’ spirituality enhance job performance? The mediating roles of intrinsic motivation and job crafting. Current Psychology, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9864-0

Mosier, C. I. (1943). On the reliability of a weighted composite. Psychometrika, 8(3), 161–168.

Niessen, C., Weseler, D., & Kostova, P. (2016). When and why do individuals craft their jobs? The role of individual motivation and work characteristics for job crafting. Human Relations, 69(6), 1287–1313.

Oprea, B. T., Barzin, L., Virga, D., Iliescu, D., & Rusu, A. (2019). Effectiveness of job crafting interventions: A meta-analysis and utility analysis. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2019.1646728

Ostroff, C., Kinicki, A. J., & Clark, M. A. (2002). Substantive and operational issues of response bias across levels of analysis: An example of climate-satisfaction relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 355.

Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36(4), 827–856.

Petrou, P. (2013). Crafting the change: The role of job crafting and regulatory focus in adaptation to organizational change. Utrecht University.

Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., Peeters, M. C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Hetland, J. (2012). Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1120–1141.

Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2015). Job crafting in changing organizations: Antecedents and implications for exhaustion and performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(4), 470–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039003

Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 885(879). https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879.

Razavi, T. (2001). Self-report measures: An overview of concerns and limitations of questionnaire use in occupational stress research.(Discussion Papers in Accounting and Management Science, 01-175) Southampton, UK. University of Southampton p 23.

Roczniewska, M. A., & Puchalska-Kaminska, M. (2017). Are managers also “crafting leaders”? The link between organizational rank, autonomy, and job crafting. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 48(2), 198–211.

Rindfleisch, A., Malter, A. J., Ganesan, S., & Moorman, C. (2008). Cross-sectional versus longitudinal survey research: Concepts, findings, and guidelines. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(3), 261–279.

Robledo, E., Zappalà, S., & Topa, G. (2019). Job crafting as a mediator between work engagement and wellbeing outcomes: A time-lagged study. International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health, 16(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081376

Rudolph, C. W., Chang, C. K., Rauvola, R. S., & Zacher, H. (2020). Meta-analysis in vocational behavior: A systematic review and recommendations for best practices. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 118, 103397.

Rudolph, C. W., Katz, I. M., Lavigne, K. N., & Zacher, H. (2017). Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102, 112–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.05.008

Sakuraya, A., Shimazu, A., Imamura, K., & Kawakami, N. (2020). Effects of a job crafting intervention program on work engagement among japanese employees: A randomized controlled trial. Frontiers In Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00235

Sakuraya, A., Shimazu, A., Imamura, K., Namba, K., & Kawakami, N. (2016). Effects of a job crafting intervention program on work engagement among Japanese employees: A pretest-posttest study. BMC Psychology, 4(1), 49–49.

Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & Bakker, A. B. (2008). It takes two to tango: Workaholism is working excessively and working compulsively. The long work hours culture: Causes, consequences choices, 203–226.

Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. E. (2015). Methods of meta-analysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings (3rd ed.). Sage.

Schmidt, F. L., & Oh, I.-S. (2013). Methods for second order meta-analysis and illustrative applications. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 121(2), 204–218.

Sekiguchi, T., Li, J., & Hosomi, M. (2017). Predicting job crafting from the socially embedded perspective: The interactive effect of job autonomy, social skill, and employee status. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 53(4), 470–497.

Seligman, M. E. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Simon and Schuster.

Seppala, P., Hakanen, J. J., Tolvanen, A., & Demerouti, E. (2018). A job resources-based intervention to boost work engagement and team innovativeness during organizational restructuring: For whom does it work? Journal of Organizational Change Management, 31(7), 1419–1437. https://doi.org/10.1108/jocm-11-2017-0448

Shin, Y., & Hur, W. M. (2019). Linking flight attendants’ job crafting and OCB from a JD-R perspective: A daily analysis of the mediation of job resources and demands. Journal of Air Transport Management, 79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2019.101681

Siddaway, A. P., Wood, A. M., & Hedges, L. V. (2019). How to do a systematic review: A best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 747–770.

Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 467–487.

Slemp, G. R., & Vella-Brodrick, D. (2013). The Job Crafting Questionnaire: A new scale to measure the extent to which employees engage in job crafting. International Journal of Wellbeing, 3(2). 126–146.

Slemp, G. R., Zhao, Y., Hou, H., & Vallerand, R. J. (2021). Job crafting, leader autonomy support, and passion for work: Testing a model in Australia and China. Motivation and Emotion, 45(1), 60–74.

Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SAJIP: South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(2), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v36i2.841

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186.

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., Derks, D., & Rhenen, W. V. (2013). Job crafting at the team and individual level: Implications for work engagement and performance. Group & Organization Management, 38(4), 427–454.

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2015). Job crafting and job performance: A longitudinal study. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 24(6), 914–928. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2014.969245

Tims, M., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2016). Job crafting and its relationships with person-job fit and meaningfulness: A three-wave study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 44–53.

Turner, R. M., Bird, S. M., & Higgins, J. P. (2013). The impact of study size on meta-analyses: Examination of underpowered studies in Cochrane reviews. PLoS ONE, 8(3), e59202.

Valentine, J. C., Pigott, T. D., & Rothstein, H. R. (2010). How many studies do you need? A primer on statistical power for meta-analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 35(2), 215–247.

van Wingerden, J., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2017). The longitudinal impact of a job crafting intervention. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 26(1), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2016.1224233

Vermooten, N., Boonzaier, B., & Kidd, M. (2019). Job crafting, proactive personality and meaningful work: Implications for employee engagement and turnover intention. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 45. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v45i0.1567

von Elm, E., Poglia, G., Walder, B., & Tramèr, M. R. (2004). Different patterns of duplicate publicationan analysis of articles used in systematic reviews. JAMA, 291(8), 974–980. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.8.974

Wang, H., Li, P., & Chen, S. (2020). The impact of social factors on job crafting: A meta-analysis and review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 8016.

Wang, H. J., Demerouti, E., Blanc, P. L., & Lu, C. Q. (2018). Crafting a job in ‘tough times’: When being proactive is positively related to work attachment. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 91(3), 569–590. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12218

Wiernik, B. M., & Dahlke, J. A. (2020). Obtaining unbiased results in meta-analysis: The importance of correcting for statistical artifacts. Advances in Methods: Practices in Psychological Science, 3(1), 94–123.

Wood, J. A. (2008). Methodology for dealing with duplicate study effects in a meta-analysis. Organizational Research Methods, 11(1), 79–95.

Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2001.4378011

Wrzesniewski, A. (2003). Finding Positive Meaning in Work. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 296–308). Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Zhang, F., & Parker, S. K. (2019). Reorienting job crafting research: A hierarchical structure of job crafting concepts and integrative review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(2), 126–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2332