Abstract

Effective educator wellbeing interventions should consider the individual, relational, and contextual influences on educator wellbeing. Given the gap between the effectiveness of positive psychology interventions (PPIs) and their real-world success, it is essential to understand and adapt to the school context when integrating psychological interventions into educational settings. The MARKERS (Multiple Action Responsive Kit for Educator, Relational, and School wellbeing) educator wellbeing program is multi-level, designed to consider the individual, relational, and contextual influences on wellbeing. Its multi-foci design also allowed for adaptations to specific contexts. This study examines the impact of the MARKERS program in one school in Aotearoa New Zealand. We use a mixed methods case study approach that draws on measures of educator wellbeing, social network measures of energising interactions, and focus group data. The use of stochastic actor-oriented models (SAOMs) allowed us to examine changes to the social network over time. Findings show that MARKERS program participants experienced a significant positive change in their relational space and experienced more energising interactions, but they were ‘swimming against the tide’ as other staff in the school had fewer energising interactions with their colleagues. Our study illustrates the importance of considering the relational and contextual influences on wellbeing when evaluating educator wellbeing interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Ensuring the wellbeing of educators is an essential element of building whole-school wellbeing. However, the research on educator wellbeing, which has mainly focused on teachers, shows high rates of stress and depression in the profession (Greenberg, 2016; Milfont et al., 2008; Steiner & Woo, 2021). Poor teacher wellbeing negatively impacts teachers and schools, as it is associated with low teacher self-efficacy (Collie et al., 2012), poor relationships with students (Hoglund et al., 2015), adverse effects on student outcomes (Caprara et al., 2006), and leads to attrition (Greenberg, 2016; OECD, 2019). By improving teacher wellbeing, these ill-effects can be ameliorated, improving not only the lives of teachers but also the sustainability of the profession and leading to positive outcomes for students, both in terms of wellbeing and achievement (McCallum & Price, 2010).

Positive psychology is a field that seeks to “understand and build the factors that allow individuals, communities, and societies to flourish” (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000, p.5). Research in the field has identified factors that allow individuals to flourish and led to the development of many positive psychology interventions (PPIs) that individuals can use to boost their wellbeing (Carr et al., 2021) including interventions focused on teacher wellbeing (e.g., Chan, 2013; Rahm & Heise, 2019). Some examples of PPIs are gratitude journalling, acts of kindness, and identifying strengths. However, many of these approaches to improving wellbeing are criticised as they focus on the individual and overlook relational and contextual factors that influence wellbeing (Brauer & Proyer, 2023; Kern et al., 2020; Lomas et al., 2021; van Zyl et al., 2023). There is a similar disconnect between what we know about wellbeing and the design of interventions to improve wellbeing in schools (Cabanas & González-Lamas, 2022). The individualised focus is also evident in interventions to improve educator wellbeing, which tend to neglect relational and contextual factors (Cann et al., 2023a). In our research, we position educator wellbeing as a positive, relational, and community endeavour. We used this approach to design an educator wellbeing program and adapted it to one specific school context, thus addressing a gap in the literature on educator wellbeing interventions.

Next, we explored the literature on educator wellbeing using a socio-ecological lens before outlining social network theory and explaining how it can be used to examine how relationships contribute to wellbeing. Then, we present a case study of the educator wellbeing program that evaluates its impact using educator wellbeing data and social network data to explore the links between relationships and wellbeing over time.

1.1 Educator Wellbeing

We use the term educator wellbeing to include all school staff—teachers, leaders, and support staff—as all are important in creating school communities. However, most research focuses on teacher wellbeing, teacher wellbeing is seldom defined, and any definitions used vary widely (McCallum et al., 2017). To define educator wellbeing for our study we drew on subjective wellbeing theory which encompasses feelings of satisfaction, high positive affect, and low negative affect (Diener, 1984) and psychological wellbeing theory, which encompasses experiences of meaning and growth (Ryff, 1989). We define educator wellbeing as educators’ satisfaction with their work, a sense of engagement in a profession that contributes to others, supportive working relationships, and low stress levels.

Socio-ecological models of wellbeing are useful for addressing the gap in the positive psychology literature, where relational and contextual elements have been overlooked. Socio-ecological models of wellbeing acknowledge that it is not only an individual’s thoughts and behaviours that influence their wellbeing, it is also influenced by relational and contextual factors in their environment). Many socio-ecological models of wellbeing are underpinned by Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological model that outlines how relational and contextual factors influence an individual’s development, through: the microsystems (different settings the person is in, and their influences via direct interaction with people or objects, or influence from connections between people within that setting), the mesosystems (interactions between different settings the individual participates in), the exosystem (settings in which the individual does not directly participate but may be affected indirectly), and the macrosystem (influences from the wider culture in which the settings are located). Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model has been used as a lens to explore wellbeing, in schools, such as student belonging (Allen et al., 2018) and teacher wellbeing (Ainsworth & Oldfield, 2019; Price & McCallum, 2015). Using a socio-ecological view to explore educator wellbeing, we find evidence of individual, relational, and contextual factors that influence educator wellbeing. These factors are interconnected, and there is a crossover among them. Therefore, arranging the evidence into these factors is a general guide only. As there are varied definitions and conceptualisations of educator wellbeing, this evidence covers not only the term wellbeing, but also related positive concepts such as flourishing, job satisfaction, and happiness, as well as negative aspects such as burnout, stress, and exhaustion.

At the individual level, teachers’ emotion regulation strategies and beliefs influence wellbeing. The strategy of suppressing emotions is linked to teachers experiencing increased anxiety and depression, and lower wellbeing (Wang et al., 2019; Yin et al., 2018); whereas emotion regulation strategies such as reappraisal (reframing the meaning of a situation to alter its emotional impact) and self-reflection are associated with contentment, enthusiasm, higher job satisfaction, and lower emotional exhaustion (Mattern & Bauer, 2014; Yin et al., 2018). Other individual factors are teacher beliefs such as self-efficacy, which is associated with higher wellbeing (Bermejo-Toro et al., 2016) and happiness (Mehdinezhad, 2012).

At the relational level positive and supportive relationships with colleagues support educators’ wellbeing (Hobson & Maxwell, 2017; Kaynak, 2020; Paterson & Grantham, 2016). However, the absence of positive and supportive relationships, or the presence of toxic relationships, hinders wellbeing (Hobson & Maxwell, 2017). Measures of social support from colleagues have been positively associated with educators’ wellbeing and job satisfaction (Ainsworth & Oldfield, 2019; Kern et al., 2014). Social network studies, which collect information on interactions between educators, also show links between relationships and educator wellbeing. For example, early career teachers are more likely to suffer burnout when they directly interact with teachers who are burnt out, known as burnout contagion (Kim et al., 2017). Educator wellbeing is also contagious, as an individual’s wellbeing is associated with the wellbeing level of the people with whom they have close relationships in school (Cann et al., 2022). Some studies show that contextual factors can impact educator wellbeing more than individual or relational factors (Ainsworth & Oldfield, 2019; Cann et al., 2022; Hobson & Maxwell, 2017).

Contextual factors such as trusting and collaborative school conditions are strongly linked to educator wellbeing (Cann et al., 2022). Teachers cite collaborative working relationships with colleagues as contributing to developing confidence, reducing anxiety and stress, and contributing to their wellbeing (Collie et al., 2012; Paterson & Grantham, 2016). Teachers’ trust in colleagues is positively associated with increased enthusiasm, commitment and contentment, and reduced anxiety and depression (Huang et al., 2019; Yin et al., 2018). In addition, supportive school leadership is linked to teacher wellbeing (Cann et al., 2021; Janovská et al., 2016).

Workload is often identified as a contextual factor that negatively impacts educator wellbeing, decreasing job satisfaction and increasing burnout (Ainsworth & Oldfield, 2019; Hobson & Maxwell, 2017; Kaynak, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic is a recently emerging contextual factor that has negatively impacted teachers’ mental health and wellbeing due to uncertainty, workload, negative perception of the profession, concern for others’ well-being, and health struggles (Kim et al., 2021). There is evidence to show a number of influences on educator wellbeing due to individual, relational, and contextual factors; however, not all of this evidence has been used to inform educator wellbeing interventions.

Most interventions to improve educator wellbeing target individual-level factors like emotion regulation and coping skills through practices such as mindfulness. Although positive relationships with colleagues are important for educators’ wellbeing, few interventions seek to develop positive supportive relationships (Cann et al., 2023a). Interventions that attend to relational factors generally include multiple content areas, such as Fernandes et al.’s (2019) intervention that includes a module on building relationships, resulting in large effect size increases in teacher wellbeing. Contextual factors that influence educator wellbeing are generally overlooked in interventions to improve educator wellbeing, with few studies even describing contextual factors such as the school culture in which an intervention is conducted, much less attempting to influence a contextual factor (Cann et al., 2023a). One exception is an intervention where teachers participated in sessions focused on improving group climate, which led to increased trust and social support and reduced stress and burnout (Sottimano et al., 2018).

The evidence that educator wellbeing interventions mostly neglect relational and contextual influences on wellbeing mirrors the patterns in positive psychology interventions that predominantly focus on the individual (van Zyl et al., 2023). However, as positive psychology evolves it increasingly considers relational and contextual aspects of wellbeing (Lomas et al., 2021). This shift has seen social network theories being used to inform the field of positive psychology in terms of how social contexts can influence wellbeing (Kern et al., 2020). We use social network theories as a foundation for this research.

1.2 Social Network Theory

Social network theory is a shift “away from individualist, essentialist and atomistic explanations toward more relational, contextual and systemic understandings” (Borgatti & Foster, 2003, p. 991). Social network theory focuses on the role of relationships in enabling the flow of resources, influencing peoples’ attitudes or behaviour, and enabling or constraining action (Cross & Parker, 2004; Wasserman & Faust, 1994). The resources embedded in these relationships are known as social capital, and can be leveraged in order to create human capital in terms of knowledge, skills, and capabilities (Coleman, 1988). Daly et al. (2016) articulated four basic assumptions of social network theory that highlight the focus beyond the individuals (actors) within a social network and highlight the importance of the relationships between people (relational ties or ties). The assumptions are: (1) actors within a network are interdependent and interconnected, (2) relational ties enable the flow of resources between actors, (3) the structure of the network influences the resource flow across the network and to individual actors, and (4) social networks provide both opportunities and constraints for individual and collective action (Daly et al., 2016). In particular social network theories are often concerned with the ‘relational space’—the informal social structures influencing peoples’ actions and attitudes and the complexity inherent within that approach (Rodway & Farley-Ripple, 2020; Sinnema et al., 2023). More specifically, in schools, relational space has been defined by Butler et al. (2015):

Relational space, therefore, when applied to a school, presents an image of that space as constituted by the various relationships between and among all the entities therein—students, staff, rooms, teaching resources, curricula, and school grounds. All of these relationships are in flux, creating a space that is constantly shifting (p. 897).

In this study, we use the term relational space to refer to social networks in schools that are comprised of the informal relationships between educators. Few studies have examined the links between school social networks and educator wellbeing. Exceptions are Kim et al.’s (2017) study, finding that burnout is contagious among teachers via their close colleagues, and Cann et al.’s (2022) study, finding that educator wellbeing was significantly associated with the number of close relationships an educator had within a school.

Social network analysis (SNA) is the methodology used to explore social networks. SNA can be used to discern patterns at the individual level (e.g. the number of relational ties an individual has), the relational level (e.g. whether a relational tie is mutual), and the contextual level (e.g. the relational activity across a network)—aligning with a socio-ecological view of the influences on wellbeing. Here, we outline some important topics within social network research and their relevance to educator wellbeing: types of relationships, number of relational ties, proportion of reciprocal (i.e., mutual) relationships, social contagion, and longitudinal network models.

SNA has been used to explore different types of relationships and their links to education and wellbeing outcomes. Social networks in schools can impact innovation (Liou & Daly, 2018), curriculum and policy implementation (Hopkins et al., 2017), and student achievement (Daly et al., 2014). The types of relationships explored in these studies are often instrumental ties, which are focused on exchanging tangible work-related resources such as advice or materials. When considering wellbeing, expressive ties are often explored, which are relationships that are more affective such as friendship or energising relationships. For example, SNA has demonstrated the importance of positive and supportive relationships (i.e., expressive ties) in reducing psychological distress (Sapin et al., 2016). In this study we examine a particular type of expressive tie, an energising tie, which is defined as “a type of interaction that increases positive affective arousal, which people can experience as emotion—short responses to specific events—or mood—longer-lasting affective states that need not be a response to a specific event” (Quinn & Dutton, 2005, p. 36). There is evidence of an association between energising interactions and educators’ job satisfaction (Daly et al., 2016), but no studies of which we are aware that have explored their link to educator wellbeing.

When analysing social networks, relational patterns can be discerned at the whole network level or for individual people in the network. At the individual level, the number of ties that a person (referred to as an actor in social network terminology) has is known as their degree centrality, which can be broken down into out-degree (the number of outgoing ties, for example, the people they go to for advice), and in-degree (the number of incoming ties, for example, people who come to them for advice). Out-degree indicates an individual’s activity within the network, whilst in-degree shows how popular an individual is (Robins, 2015). This information can be linked to consequences for the individual; for example, educators who actively seek advice from others tend to show the largest improvements to their practice, whereas educators who are highly sought out for advice have lower levels of improvement (Sinnema et al., 2021). In terms of wellbeing, the greater a person’s social activity, the greater their happiness levels (Sun et al., 2019). The social activity in the network as a whole can be evaluated through the measure of density, the proportion or percentage of all possible ties that are actually present (Robins, 2015). Network density is useful for evaluating changes at an organisational level over time, for example, the degree of collaboration activity in schools (Sinnema et al., 2023).

Affective relationships, such as friendship, are more likely to lead to a reciprocal relationship, also known as a mutual dyad (Robins, 2015). At the whole network level, the proportion or percentage of ties that are reciprocated is known as the reciprocity of the network. Reciprocity may be expressed at the dyad level, where “if someone does something for you, you do something for them” (Rodway & Farley-Ripple, 2020, p. 180). Generalised reciprocity is expressed at the community level, where a ‘pool of goodwill’ captures the idea that people contribute to the community, as they trust that at some point, they will also benefit from it (Baker & Dutton, 2017).

Social networks can also be used to study social contagion—the spread of behaviours, emotions and phenomena through a network. The theory of social contagion outlines how a variable (such as smoking, or happiness) affects that variable in another person via social interaction, leading to the spread of behaviours such as smoking and alcohol use, phenomena such as obesity and divorce, and emotions such as happiness and loneliness (Christakis & Fowler, 2013). Social network studies in schools show burnout is contagious among teachers via their close colleagues and mentors (Kim et al., 2017), and wellbeing is contagious through educators’ close relationships with colleagues (Cann et al., 2022).

To explore network changes over time, longitudinal models of social networks (e.g., stochastic actor-oriented models [SAOMs]), can be used. SAOMs can test for statistically significant changes in networks and behaviour over time, including checking for social contagion effects. Studies using SAOMs have shown that educational leaders tend to build advice and knowledge-sharing ties with others in the same location (Daly & Finnigan, 2011) and school students become similar to their friends in terms of homework completion and attention in class (Geven et al., 2013). However, we are unaware of any studies that use SAOMs to explore educator wellbeing.

1.3 The Present Study—Exploring the Impact of a Socio-Ecological Educator Wellbeing Intervention

Socio-ecological influences on wellbeing underpin the development of the MARKERS (Multiple Action Responsive Kit for Educator, Relational, and School wellbeing) educator wellbeing program we evaluate in this study (the development and adaptation of the program is explained in detail in Cann et al., 2023b). The multi-level program, targets various socio-ecological aspects of educator wellbeing at the individual, relational, and school levels. Additionally, it employs a multi-foci strategy, encompassing a range of activities that target different levels and allow for adaptation, such as gratitude exercises, active constructive responding, and workload case studies. The MARKERS program was adapted for implementation at one school in Aotearoa New Zealand. Based on in-depth interviews with several staff members at the school we identified key needs for educators in the school to rebuild social connections after the impacts of COVID restrictions, and address a lack of appreciation and recognition. The MARKERS program consisted of seven 1-hour sessions at 2-week intervals in school term time. The session topics were: (1) introduction; (2) wellbeing definitions and models; (3) stress coping strategies, stress mindset, and the stress cycle; (4) gratitude and appreciation; (5) active constructive responding; (6) workload in schools; (7) recap and forward planning. The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of the MARKERS educator wellbeing program on educator wellbeing and the factors that influence educator wellbeing. Given the MARKERS program’s focus on rebuilding social connections and improving their quality in terms of appreciation and recognition, we centre the exploration of the program’s impact on the relational space through the use of SNA.

2 Methods

We use a mixed-methods case study methodology to explore the impact of the MARKERS educator wellbeing program. Case studies are a preferred methodology for exploring cause and effect (Yin, 2009), and in this case, how the wellbeing program influenced educator wellbeing and the relational space. Mixed-methods approaches allow the integration of both quantitative and qualitative methods, drawing on their strengths in answering different questions, and thus giving more insight than either method alone (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

2.1 Sampling

The case study site was an intermediate school (years 7 and 8) in an urban area of Aotearoa New Zealand (intermediate schools are part of the primary education sector, teaching students aged 11–13 years old). The school and its staff had working relationships with the authors due to the schools involvement in other research projects, and the school’s senior leadership team had expressed an interest in developing educator wellbeing in their school.

All school staff were invited to participate in surveys in October 2021 and October 2022. The MARKERS wellbeing program occurred between June and October 2022, and seven staff attended at least five of the seven sessions, six of whom also participated in a focus group in October 2022. In order to ensure an accurate comparison of any changes to measures in the surveys between time 1 (October 2021) and time 2 (October 2022), we created a matched dataset consisting of only the individuals invited to participate in both surveys (i.e., anyone joining or leaving the school during that period was not included). This gives us an accurate comparison of the core members of the school network over time, and is a common approach used in social network research in education (for example: Daly & Finnigan, 2011). Therefore, the final survey dataset for the whole school was 32 staff, including five MARKERS program participants. The demographic data for the matched dataset is provided in Table 1. The study was reviewed and approved by the research ethics committee at the corresponding author’s institution. Consent was obtained from the principals of the school in order to invite their staff to participate, and all participants gave informed consent.

2.2 Data Collection

Online surveys collected data about educator wellbeing and relational data about energising interactions between staff. A focus group with MARKERS participants gathered data about their experiences of the program.

2.2.1 Educator Wellbeing

The survey included two separate measures to collect wellbeing data: the educator wellbeing scale and the perceived stress scale. We previously developed and validated the educator wellbeing scale with a sample of approximately 450 educators in Aotearoa New Zealand (Cann et al., 2022). The scale is based on the satisfaction with life scale (Diener et al., 1985) and the flourishing scale (Diener et al., 2010) adapted for an educator specific focus. The scale comprises 15 items where respondents rate their agreement on a 6-point agreement scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Analysis showed that 13 of these items form three distinct sub-scales of wellbeing: satisfaction, contribution, and support, with reasonable reliability with α = 0.65 to 0.84 (Cann et al., 2022). To measure the negative end of the wellbeing spectrum, we used the shortened 4-item version of the perceived stress scale (PSS; Cohen et al., 1983). The scale comprises 4 items where respondents rate the frequency of feelings on a five-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). The scale has been used in previous research with educators and shown good reliability, with α = 0.85–0.88 (Harris et al., 2016).

2.2.2 Energising Interactions

We collected social network data about educators’ energising interactions, which can increase positive affect and job satisfaction (Daly et al., 2016). Survey respondents were asked: “Which colleague(s) give you an increase in positive energy after an exchange? By “energy” we mean feeling inspired, a positive, encouraging, and motivating interaction”. To answer the question a network roster (a list of all staff in their school) was provided, and educators ticked the names of people with whom they had an energising interaction.

2.2.3 Focus Group and Survey Comments

A week after the seven educators completed the MARKERS program, six of them participated in a focus group with the aim of understanding their experiences of the program, and any changes to wellbeing as a result of the program. The focus group followed a semi-structured format, which included pre-prepared questions, follow up questions from the researcher, and discussion between participants. The focus group was audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. All focus group comments and survey comments reported in this paper are from the five MARKERS participants in the matched dataset used for the SAOM.

MARKERS program participants were provided with a version of the whole school survey that had open-ended questions where they could comment on aspects of the wellbeing program and its impacts. These comments were collated with the focus group comments for the qualitative data analysis.

2.3 Data Preparation and Analyses

We followed a typical convergent mixed-methods approach to data analysis where we analysed the quantitative and qualitative data separately and then merged the results (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

2.3.1 Data Preparation

The educator wellbeing scale and PSS data were inspected for missing values. For individuals with < 10% missing data, the missing values were imputed, for individuals with > 10% missing data their response for that scale was excluded from analyses. The cut off value of 10% is commonly accepted in educational studies (Brown, 2016). Missing data were imputed in IBM SPSS Statistics (version 29) using the expectation maximisation method (Dempster et al., 1977). We prepared the matrix of responses for the energising interactions network in Microsoft Excel, for use in R statistical software (version 4.2.3). The audio recording of the focus group was transcribed and imported into NVivo version 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018) for coding.

2.3.2 Data Analysis

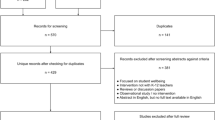

We used the R package igraph (Csardi & Nepusz, 2006) to perform network analysis on the matched dataset. First, a series of whole network measures were produced, such as density, reciprocity, and mutual dyads. Then maps of the energy networks were created for time 1 and time 2. Figure 1 provides some key terminology for reading the network maps.

Key terminology for network maps. Social network specific terminology is introduced in bold. A, B, C, and D are people (actors) represented by circles (nodes) on the map. The lines show relational ties between two actors. The arrow on the line shows the direction of the tie. For example, from the perspective of A:

• A says they have an energising tie with B. This is an outgoing tie.

• The total number of outgoing ties is the outdegree. A has an outdegree of 2.

• A is named by D as someone they have an energising tie with. This is an incoming tie.

• The total number of incoming ties is the indegree. A has an indegree of 2.

• Both A and C say they have an energising tie with each other. This is a reciprocal tie.

Nodes are sized by the number of ties (both outgoing and incoming ties).

We then performed a longitudinal analysis of the social network using a stochastic actor-oriented model (SAOM) with the R package RSiena (Ripley et al., 2023). SAOMs provide models of tie changes over time that are driven by the characteristics of the actors within the network such as actors’ preference for building ties, or characteristics of pairs of actors (dyadic influences), such as whether a tie is reciprocated (Snijders et al., 2010). We used a co-evolution variation of a SAOM, which analyses the longitudinal network data jointly with changing actor attributes (for an introduction to this approach see: Kalish, 2020). We developed four co-evolution SAOMs; one model each for the three subscales of the wellbeing scale and one for the stress scale. The models have a set of network effects (related to energising ties) and behaviour effects (related to wellbeing), which are described in Table 2. Any significant effects in the model indicate an influence on either energising tie formation or the wellbeing of actors.

SAOM has some advantages over using raw network data used to generate the network statistics and maps. There were missing network data, as the completion rate for the matched dataset was 87.5% at time 1 and 81.3% at time 2. These completion rates are acceptable for reliable social network analyses of between 70% and 80% depending on the analysis (Kossinets, 2006), but the percentage that completed both the time 1 and time 2 surveys was only 71.9%. However, SAOMs have the advantage that they impute for missing data so they give a more accurate account of the processes occurring in the network. SAOMs perform well with up to 20% missing data, but may work with more missing data, which is tested by model convergence parameters (de la Haye et al., 2017). The models presented in this paper met all convergence parameter criteria (Ripley et al., 2023) giving us confidence that the models were not adversely affected by missing data.

2.3.3 Focus Group and Survey Comments

The focus group transcript and qualitative data from MARKERS program participants’ surveys were coded in NVivo version 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018) using a combination of pre-determined codes and inductive coding. The pre-determined codes were based on key ideas in the questions, such as comments about applying learning from the program. Inductive codes were developed as the data were coded. A codebook was created before the start of coding with the a of pre-determined codes, a description of the code, and inclusion and exclusion notes. During two passes of coding any inductive codes that were developed were added, and example quotes were added to illustrate the codes. To avoid ‘definitional drift’, and refine the codes, a constant comparison method was used, where coded data within the same node were compared to each other and to the codebook (DeCuir-Gunby et al., 2011; Gibbs, 2007).

3 Results

Our findings indicate that, in general, the energising ties in the school decreased over time, yet MARKERS participants tended to build energising ties. MARKERS participants also tended to have improved wellbeing over time, whilst other staff in the school tended to have lower wellbeing. In the following sections, we explain these findings by integrating wellbeing data, social network data and focus group data.

3.1 Descriptive Statistics and Network Maps

MARKERS participants mean scores for the satisfaction and support subscales of wellbeing increased between the two time points, and their stress scores decreased. None of the changes were significant, although the small sample size (n = 5) limits statistical power. In contrast to the MARKERS participants, the mean scores on all three subscales of wellbeing decreased for all other educators in the school, and the mean score for stress increased slightly. Details of these changes are given in Table 3. The internal consistencies of the wellbeing and stress measures were checked for the sample of 23 educators that completed the survey at both time points. Cronbach’s alpha values were α = 0.911 (wellbeing: satisfaction), α = 0.784 (wellbeing: contribution), α = 0.754 (wellbeing: support), and α = 0.758 (PSS).

In general, the number of energising ties decreased, yet the MARKERS program participants deviate from that prevailing trend by building more energising ties. This can be seen in the changes in node size in the maps of the energy networks at time 1 and 2 (Fig. 2). The maps indicate fewer energising ties for non-participants at time 2 than at time 1, as the size of the nodes decreases for the majority of actors. Network statistics (Table 4) provide support for the observation that there tend to be fewer energising ties in the network over time with the density of ties decreasing from 29 to 22%. Interestingly, there was a much greater reduction in mutual dyads (a 36% drop) than asymmetrical dyads (a 13% drop), meaning that at time 2 relationships were less likely to be reciprocal. Although the completion rate dropped slightly between time 1 and time 2 (from 87.5 to 81.3%, or two fewer people), this does not explain the much greater drop in the number of mutual ties. For the MARKERS program participants, the majority of their nodes either stayed the same size or increased in size, indicating they had the same or a greater number of energising ties. Next, we turn to the SAOMs to check whether these changes were significant.

3.2 Co-Evolution Stochastic Actor Oriented Models Results

MARKERS program participants were significantly more likely to build energising ties than other staff; most staff had a tendency not to build energising ties, as indicated by the statistically significant effects for the SAOMs. The SAOMs also showed no significant changes in wellbeing across the network, and participation in the MARKERS program, or being connected to someone in the program, had no significant effect on wellbeing. The SAOM results in Table 5 show four co-evolution models that combined the energy network with one of the three subscales of wellbeing and the stress scale. Each is explained in more detail below.

3.2.1 Network Effects - Energising Ties

The frequency with which actors can change a tie in the simulation is called the network rate parameter (1); no p-values are given, as these would be meaningless (Snijders et al., 2010). The network rate parameter shows that each actor considers changing an energising tie between 16 and 17 times on average. Similarly, the behaviour rate parameter (16) is the number of opportunities each actor had to change their wellbeing, which was between 1 and 2 on average. The negative and significant outdegree effect (2) shows that overall there is a tendency for staff not to create energising ties. The positive and significant popularity indegree effect (4) indicates that if staff do form energising ties over time, these tend to be with staff members who are frequently named as someone with whom people have an energising interaction. For the MARKERS program participants, the ego effect (8) is positive and significant, indicating that they tend to build energising ties, but the alter effect (7) shows a non-significant effect for staff naming the MARKERS program participants as someone they have an energising interaction with. There were no significant effects on tie formation due to members’ gender (10 to 12) or years working in education (13 to 15).

The MARKERS program participants’ tendency to build energising ties was reinforced by the qualitative data which indicated more interactions were occurring, and that all participants were cognisant about expressing appreciation to their colleagues. One participant summed this up in the focus group: “I think all of us have gone away and just sort of thought a little bit harder about the effect we have on others”. Comments from the survey indicated that the program had increased interactions between participants: “some people who participated in the programme I communicate with them more” and had prompted “more conversations about well-being” with other school staff. The program prompted more wellbeing-focused conversations by building a greater wellbeing vocabulary, as indicated by the focus group comment: “opening the discussions with other people and being like oh, yeah… this is the language I can use with people”. The program also led to more positive interactions, all but one participant in the focus group commented on deliberately showing their colleagues appreciation, with most commenting that the MARKERS sessions on appreciation were the most impactful content of the program, such as: “I was thinking, with my direct team, how am I showing them that I appreciate them, or making them realise that their talents are specific to just them, and therefore, they’re like needed?” and “appreciation language…I think that was good. That’s something that I kept in mind” and “the appreciation languages and the gratitude stuff was really good”. However, participants contrasted their own awareness of showing appreciation with a lack of awareness in other staff, consistent with MARKERS participants reporting a greater number of energising ties, whilst other staff reported fewer: “Because if we just talk to each other it’s like ‘ooh, I see what you’re doing’… It’s easy to miss those things sometimes, and that can be part of the problem, not noticing when people are appreciating, not noticing when the good things are happening”.

3.2.2 Behaviour Effects - Wellbeing

There were no significant changes in educators’ wellbeing, as indicated by non-significant behavioural effects in the SAOMs (17 and 18). Even focusing on only the MARKERS program participants, there were no significant changes in their wellbeing (19). Therefore it is not surprising that there was no wellbeing contagion effect for other people who interacted with MARKERS program participants (20). The MARKERS program participants may have shown no change in wellbeing as they were inconsistent in applying their learning from the sessions, as indicated by comments in the focus group. In each session, time was set aside for participants to choose from a range of wellbeing actions to implement between sessions. However, providing a number of options to allow flexibility led one participant to comment “it’s hard to be accountable on something that’s a bit fluid”. Some participants indicated they struggled to follow through at times: “I was like, cool idea, I’m gonna do that tomorrow. Didn’t do it”, and that a more regular focus on content would be useful for forming habits: “it would have been almost more useful to do three sessions on implementing gratitude…to keep it in our minds for that amount of time so it becomes a habit”. However, all participants indicated a behaviour change that resulted from the program, with some forming regular habits. Two participants referred to using the stress cycle strategies, and two participants referred to regular gratitude habits as a result of the program: “I actually really started to look forward to washing my hair each week because I do my gratitude thing”. Written comments in the survey were also consistent with changes being made: “a better understanding of practices that I can conduct that will positively impact my wellbeing” and “I’ve thought more about my weekly gratitude”. The lack of any significant wellbeing contagion effect from the MARKERS program participants is consistent with focus group comments. Comments showed that, as a small group of staff, they felt they had limited school-wide impact: “the effects of us changing our mindset on some things, and the way that we discourse with each other, or the way that we view situations and things like that, the effect is lessened by the fact that it’s a small representative here”. The program included discussion of school wide factors that can influence wellbeing, such as workload, and possible school wide initiatives in response, but one participant commented on the difficulty of trying to reduce workload: “What can you cut? It’s really hard”.

4 Discussion

We presented a mixed-methods case study that examined the impact of the MARKERS educator wellbeing program on the wellbeing and relational space of 32 staff in one school in Aotearoa New Zealand, including five individuals who participated in the MARKERS program. Data collected were measures of wellbeing, social network data, and focus group data. The use of longitudinal network modelling (SAOMs) enabled us to check for contagion effects between the wellbeing program participants and the other staff members in their school. Qualitative data provided rich descriptions of the changes that occurred. We found no significant changes in wellbeing, but strong evidence of changes in the relational space of MARKERS program participants in terms of more positive interactions with colleagues. We explain three key findings about the relational space and wellbeing: (1) the MARKERS participants positive changes in relational space, (2) the different perceptions of the relational space experienced by other school staff, and (3) the lack of a significant change in wellbeing.

4.1 MARKERS Participants Built Energising Ties and Saw the Energisers in the Network

The relational space of MARKERS program participants improved significantly; awareness of cultivating appreciative, positive interactions with colleagues and the tendency to build energising ties all increased. Energising ties may have been built due to participants showing gratitude and appreciation to others and celebrating positive news. When a person expresses thanks to a colleague, the person giving thanks will experience an increase in energy if they believe their expression of thanks will strengthen their relationship with the other person (Quinn & Dutton, 2005). People who focus on showing gratitude and kindness to people in their social network experience significantly greater relationship satisfaction (O’Connell et al., 2016). Celebrating other people’s positive emotions with them (through active constructive responding or positive empathy) is linked to feelings of greater social connection (Gable et al., 2004; Morelli et al., 2015). This is consistent with content taught in the MARKERS program: showing gratitude and appreciation to others and celebrating positive news (through active constructive responding) strengthens relationships. Given that all MARKERS program participants talked about increased use of gratitude and appreciation, this could explain the findings about their improved relational space.

The energising ties of MARKERS participants tended to be with ‘energisers’ in the network; those with more incoming energising ties than others. This suggests a tendency to notice the positives in their environment. In experimental settings, people with more optimistic expectations pay more attention to positive stimuli (Kress et al., 2018). Optimism is often measured through respondents ‘positive expectancies’ (Malouff & Schutte, 2017), and the MARKERS program specifically built positive expectancies through content about gratitude, appreciation, and celebrating positive news. This is illustrated by the finding that all but one of the MARKERS program participants specifically talked about the program prompting them to show more appreciation to their colleagues. As showing appreciation to another person involves making a positive evaluation of that person (Pfister et al., 2020), this could explain why MARKERS participants noticed the energisers in the network.

4.2 MARKERS Participants Were “Swimming Against the Tide”, as Other Staff had Different Perceptions of the Relational Space

The MARKERS program participants’ tendency to form more energising ties goes against prevailing conditions in the school, as other staff tended not to form energising ties over time. There was also a large decrease in the number of mutual ties in the school (and, therefore, an associated drop in reciprocity in the school network). Considering the MARKERS program participants tended to increase their number of energy ties alongside the decrease in the number of mutual ties across the whole-school network, this indicates MARKERS participants were involved in many asymmetrical (or non-reciprocated) ties. This is unusual as people tend to reciprocate positive affective relationships (Robins, 2015), and mutual ties are less likely to dissolve over time (Spillane & Shirrell, 2017). This points to a difference between the MARKERS program participants and other school staffs members’ perceptions of the relational space.

Different interpretations of the energising ties (i.e. non-reciprocal ties) may be explained due to people experiencing an increase or decrease in energy depending on their interpretation of an interaction (Quinn & Dutton, 2005). Whilst the MARKERS participants experienced energising interactions due to their tendency to look for opportunities to show appreciation and celebrate positive news, other staff could experience that same interaction differently. For example, if a receiver of thanks feels they have been put in an awkward social situation they will not experience an increase in energy (Quinn & Dutton, 2005). Another reason for different interpretations of the same interactions could be due to one party behaving differently than normal. For example, in O’Connor and Cavanagh’s (2013) social network study of a leadership coaching intervention they found that interactions were experienced more positively by the recipient of coaching than the person they were interacting with. O’Connor and Cavanagh (2013) suggest this may be due to the person being coached being supported to try new skills during their interaction, whereas people they interact with may experience the new skills as an unexpected change that provokes anxiety. As we only have focus group data from MARKERS program participants and not other school staff, we do not have information on how other school staff interpreted their interactions with the MARKERS program participants. Therefore, future research could focus on gathering qualitative data from people with whom wellbeing program participants interact.

Another reason for different perceptions of interactions could be due to a time lag between changes occurring and people noticing those changes. Research comparing friendship behavioural networks (phone calls and messages between people) with cognitive networks (people nominating others on a network survey) shows there can be a time lag between an increase in communication and a subsequent nomination as a friend (Bahulkar et al., 2017). There may be a similar time lag between the MARKERS program participants having more positive communications with colleagues, and their colleagues noticing that and nominating them on the network survey. Further research could collect follow up data to test for such a time lag.

4.3 No Significant Changes to Wellbeing, Even for MARKERS Program Participants Who Had Positive Changes in Their Relational Space

School staff did not experience any significant changes in wellbeing. Even the MARKERS program participants, who tended to build energising ties, did not experience a significant change in their wellbeing. This suggests there is not a significant link between energising ties and wellbeing. This somewhat differs from other research that found that people with higher job satisfaction were more likely to send energy ties (Daly et al., 2016). There is little other research exploring the link between energising ties and wellbeing.

The increase in energising ties but lack of increase in wellbeing for the MARKERS program participants may be due to the differences in building habits around daily interactions versus individual habits. For example, MARKERS participants had multiple opportunities to implement their learning about positive relationships in their day-to-day interactions, which may explain their tendency to form energising ties. However, program participants also talked about difficulties in creating individual wellbeing habits such as a gratitude practice, which may explain why there was no significant change in wellbeing. Other research suggests that more time may be needed to observe significant wellbeing improvements. A study of five different positive psychology interventions (PPIs) shows the varying timing of impacts on happiness and depression, with some PPIs leading to immediate changes that lasted for 6 months, some having immediate effects that ceased 1 week after the intervention, and some with effects that only became significant 1 month after the intervention (Seligman et al., 2005). Similar variation in the timing of effects has been observed with interventions to improve teacher wellbeing (Cann et al., 2023a). For example, Rahm and Heise’s (2019) multi-foci intervention showed that at a 5-month follow-up, significant increases to flourishing were sustained, and increases to positive affect were no longer significant, yet self-efficacy only became significant at the 5-month mark. Prolonged positive impacts on wellbeing were found to be associated with whether participants actively continued wellbeing practices they had learnt during interventions (Seligman et al., 2005). When MARKERS program participants discussed having difficulty forming regular wellbeing habits, some suggested that the program could be improved by focusing on one skill to practise throughout all program sessions. This illustrates a tension between supporting participants to form habits by repeating the same skill, and the evidence showing that multi-foci programs incorporating several PPIs outperform single PPI interventions (Donaldson et al., 2021; van Agteren et al., 2021) Thus, an area for future research is to focus on measuring and supporting building regular wellbeing habits outside of intervention sessions.

The lack of a link between increased positively energising interactions and wellbeing may be explained by the phenomenon of ‘bad is stronger than good’. Research outlines how ‘bad’ phenomena (events, emotions, feedback, interactions etc.) have a stronger effect on people than ‘good’ phenomena, and in the context of social networks this has been shown to lead to feeling of belonging being influenced by avoiding negative interactions rather than engaging in positive interactions (Baumeister et al., 2001). There may be a similar mechanism in our study, meaning that the increased number of energising interactions did not influence wellbeing, and future research could explore whether avoiding negatives, such as managing conflict, has a greater influence on wellbeing.

The lack of any significant change in wellbeing could also be due to working against prevailing conditions of decreasing wellbeing. The COVID-19 pandemic created some unique demands on teachers, with evidence showing that this led to a general decline in teacher wellbeing in other countries (Kim et al., 2021). In Aotearoa New Zealand, the ongoing COVID-19 restriction from 2020 to 2022, when this study was conducted, continued to impact educators, with principals describing feeling “stretched and stressed” (NZEI Te Riu Roa, 2023a, para. 2). The impacts of the pandemic added to already difficult working conditions, such as staff shortages and large class sizes (Wylie & MacDonald, 2020), culminating in approximately 50% of the education workforce going on strike in March 2023 (Stuff, 2023). Few studies have tested educator wellbeing interventions during the pandemic, but one exception is Lee et al.’s (2023) intervention with teachers in Hong Kong, which led to significant changes in teachers rating of their relationships with colleagues despite no change in wellbeing. In the context of a workforce experiencing a host of negative impacts on wellbeing, the MARKERS wellbeing program may have helped to buffer against a drop in wellbeing. Future research would need to include control group comparisons to explore this, although given our research premise that unique school contexts influence educator wellbeing, it would be difficult to match schools with the same context.

4.4 Limitations

The single-context case-study approach allowed deep insights into the impact of the MARKERS programme, but also had inherent limitations. The case-study approach used did not include a control group, limiting the comparisons we can make to prevailing conditions for educators in Aotearoa New Zealand. Our case study focused on one school, and therefore the sample size is small (5 people in the MARKERS program, and 32 school staff in total), so statistical power is limited. Work has only recently commenced on methods to perform power analyses for SAOMs, and indicates that for co-evolution SAOMs statistical power is likely higher for network effects than behaviour effects (Kalish, 2020; Stadtfeld et al., 2020), meaning our study may be underpowered for detecting changes in wellbeing. Kalish (2020) suggests that a network of at least eight actors is a reasonable size for SAOMs of the co-evolution of networks and behaviour, and therefore the results presented here for the network of 32 educators can be considered an adequate size for co-evolution SAOM analysis. The small sample size also means that generalisability to other contexts is limited. However, by using a socio-ecological approach to wellbeing, we accept the lack of generalisability as a trade off with developing a deep understanding of a social phenomenon in a specific context. As Kern et al. (2020) describe, when considering the influence of context on wellbeing “generalizability matters less than identifying the conditions in which findings occur (i.e., boundaries around a finding)” (p. 710).

4.5 Conclusion

Our examination of the impact of the MARKERS educator wellbeing program shows that program participants experienced significant positive change in their relational space, but no significant changes to their wellbeing. By examining changes experienced by the program participants and their colleagues in the same school, we were captured the complex relationships between educator wellbeing and their relational space. We assert that different perceptions of interactions and influences beyond the school context can lead to ‘swimming against the tide’ when trying to improve educator wellbeing. A key takeaway from this research is the importance of considering the specific relational and contextual influences on educator wellbeing, not only in designing a wellbeing intervention, but also in evaluating its impact.

Data Availability

The ethics approval for this project, and the related participant information documents and consent forms, stated that only the research team will have access to the data. Therefore, the authors are unable to make the data available to others.

References

Ainsworth, S., & Oldfield, J. (2019). Quantifying teacher resilience: Context matters. Teaching and Teacher Education, 82, 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.03.012.

Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8.

Bahulkar, A., Szymanski, B. K., Chan, K., & Lizardo, O. (2017). Co-evolution of two networks representing different social relations in NetSense. In H. Cherifi, S. Gaito, W. Quattrociocchi, & A. Sala (Eds.) Complex Networks & Their Applications V: Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on Complex Networks and their Applications (Complex Networks 2016) (pp. 423–434). Springer International Publishing.

Baker, W., & Dutton, J. E. (2017). Enabling positive social capital in organizations. In J. E. Dutton, & B. R. Ragins (Eds.), Exploring positive relationships at work: Building a theoretical and research foundation (pp. 325–345). Psychology.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323.

Bermejo-Toro, L., Prieto-Ursúa, M., & Hernández, V. (2016). Towards a model of teacher well-being: Personal and job resources involved in teacher burnout and engagement. Educational Psychology, 36(3), 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2015.1005006.

Borgatti, S. P., & Foster, P. C. (2003). The network paradigm in organizational research: A review and typology. Journal of Management, 29(6), 991–1013. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-2063_03_00087-4.

Brauer, K., & Proyer, R. T. (2023). Introduction to the Special Issue Well-being in romantic relationships. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00105-6.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Brown. (2016). The qualitative secret within quantitative research: It’s not just about numbers. In C. J. McDermott, & B. Kožuh (Eds.), Modern approaches in Social and Educational Research (pp. 33–42). Department of Education, Antioch University.

Butler, J. K., Kane, R. G., & Morshead, C. E. (2015). It’s my Safe Space: Student Voice, Teacher Education, and the Relational Space of an Urban High School. Urban Education, 52(7), 889–916. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085915574530.

Cabanas, E., & González-Lamas, J. (2022). A critical review of positive education: Challenges and limitations. Social Psychology of Education, 25, 1249–1272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-022-09721-7. https://doi-org.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/.

Cann, R. F., Riedel-Prabhakar, R., & Powell, D. (2021). A model of positive School Leadership to improve teacher wellbeing. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 6(2), 195–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-020-00045-5.

Cann, R. F., Sinnema, C., Daly, A. J., Rodway, J., & Liou, Y. H. (2022). The power of school conditions: Individual, relational, and organizational influences on educator wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.775614.

Cann, R. F., Sinnema, C., Rodway, J., & Daly, A. J. (2023a). What do we know about interventions to improve educator wellbeing? A systematic literature review. Journal of Educational Change.

Cann, R. F., Sinnema, C., Daly, A. J., & Rodway, J. (2023b). A contextual approach to designing, implementing, and adapting a wellbeing program: A case study of the MARKERS wellbeing program for educators. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology.

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Steca, P., & Malone, P. S. (2006). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of job satisfaction and students’ academic achievement: A study at the school level. Journal of School Psychology, 44(6), 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.09.001.

Carr, A., Cullen, K., Keeney, C., Canning, C., Mooney, O., Chinseallaigh, E., & O’Dowd, A. (2021). Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(6), 749–769. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1818807.

Chan, D. W. (2013). Counting blessings versus misfortunes: Positive interventions and subjective well-being of Chinese school teachers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 33(4), 504–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.785046.

Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2013). Social contagion theory: Examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Statistics in Medicine, 32(4), 556–577. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.5408.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. https://doi.org/10.1086/228943.

Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2012). School climate and social–emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 1189–1204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029356.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative & mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage.

Cross, R., & Parker, A. (2004). The hidden power of social networks: Understanding how work really gets done in organizations. Harvard Business School Press.

Csardi, G., & Nepusz, T. (2006). The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal, Complex Systems, 1695(5), 1–9. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gabor-Csardi/publication/221995787_The_Igraph_Software_Package_for_Complex_Network_Research/links/0c96051d301a30f265000000/The-Igraph-Software-Package-for-Complex-Network-Research.pdf.

Daly, A. J., & Finnigan, K. S. (2011). The Ebb and Flow of Social Network ties between District leaders under high-stakes accountability. American Educational Research Journal, 48(1), 39–79. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831210368990.

Daly, A. J., Moolenaar, N. M., Der-Martirosian, C., & Liou, Y. H. (2014). Accessing capital resources: Investigating the effects of teacher human and social capital on student achievement. Teachers College Record, 116(7), 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811411600702.

Daly, A. J., Liou, Y. H., & Brown, C. (2016). Social Red Bull: Exploring Energy relationships in a School District Leadership Team. Harvard Educational Review, 86(3), 412–448. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-86.3.412.

de la Haye, K., Embree, J., Punkay, M., Espelage, D. L., Tucker, J. S., & Green, H. D. Jr. (2017). Analytic strategies for longitudinal networks with missing data. Social Networks, 50, 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2017.02.001.

DeCuir-Gunby, J. T., Marshall, P. L., & McCulloch, A. W. (2011). Developing and using a codebook for the analysis of interview data: An example from a professional development research project. Field Methods, 23(2), 136–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X10388468.

Dempster, A. P., Laird, N. M., & Rubin, D. B. (1977). Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 39(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1977.tb01600.x.

Diener, E. D. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542.

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Diener, E. D., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y.

Donaldson, S. I., Chen, C., & Donaldson, S. I. (2021). Designing positive organizational psychology interventions. In S. I. Donaldson, & C. Chen (Eds.), Positive organizational psychology interventions: Design and evaluation (pp. 1–38). Wiley Online Library.

Fernandes, L., Peixoto, F., Gouveia, M. J., Silva, J. C., & Wosnitza, M. (2019). Fostering teachers’ resilience and well-being through professional learning: Effects from a training programme. Australian Educational Researcher, 46(4), 681–698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00344-0.

Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., Impett, E. A., & Asher, E. R. (2004). What do you do when things go right? The Intrapersonal and Interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 228–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.228.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of meta-analyses in education. Routledge.

Geven, S., Weesie, J., & Van Tubergen, F. (2013). The influence of friends on adolescents’ behavior problems at school: The role of ego, alter and dyadic characteristics. Social Networks, 35(4), 583–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2013.08.002.

Gibbs, G. (2007). Analysing qualitative data. Sage.

Greenberg, M. T. (2016). Teacher Stress and Health: Effects on Teachers, Students and Schools. Pennsylvania State University. Available at: https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2016/07/teacher-stress-and-health.html.

Harris, A. R., Jennings, P. A., Katz, D. A., Abenavoli, R. M., & Greenberg, M. T. (2016). Promoting stress management and wellbeing in educators: Feasibility and efficacy of a school-based yoga and mindfulness intervention. Mindfulness, 7(1), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0451-2.

Hobson, A. J., & Maxwell, B. (2017). Supporting and inhibiting the well-being of early career secondary school teachers: Extending self-determination theory. British Educational Research Journal, 43(1), 168–191. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3261.

Hoglund, W. L. G., Klingle, K. E., & Hosan, N. E. (2015). Classroom risks and resources: Teacher burnout, classroom quality and children’s adjustment in high needs elementary schools. Journal of School Psychology, 53(5), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2015.06.002.

Hopkins, M., Ozimek, D., & Sweet, T. M. (2017). Mathematics coaching and instructional reform: Individual and collective change. Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 46, 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmathb.2016.11.003.

Huang, S., Yin, H., & Lv, L. (2019). Job characteristics and teacher well-being: The mediation of teacher self-monitoring and teacher self-efficacy. Educational Psychology, 39(3), 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1543855.

Janovská, A., Orosová, O., & Janovský, J. (2016). Head teacher’s social support, personality variables and subjective well-being of Slovak primary teachers. Orbis Scholae, 10(3), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.14712/23363177.2017.11.

Kalish, Y. (2020). Stochastic actor-oriented models for the co-evolution of networks and behavior: An introduction and tutorial. Organizational Research Methods, 23(3), 511–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118825300.

Kaynak, N. E. (2020). A close look at teachers’ lives: Caring for the well-being of elementary teachers in the US. International Journal of Emotional Education, 12(1), 19–34. Retrieved from https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/bitstream/123456789/55036/1/v12i1p2.pdf.

Kern, M. L., Waters, L., Adler, A., & White (2014). Assessing employee wellbeing in schools using a multifaceted approach: Associations with physical health, life satisfaction, and professional thriving. Psychology, 5(6), 500–513. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2014.56060.

Kern, M. L., Williams, P., Spong, C., Colla, R., Sharma, K., Downie, A., Taylor, J. A., Sharp, S., Siokou, C., & Oades, L. G. (2020). Systems informed positive psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(6), 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1639799.

Kim, J., Youngs, P., & Frank, K. (2017). Burnout contagion: is it due to early career teachers’ social networks or organizational exposure? Teaching and Teacher Education, 66, 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.04.017.

Kim, L. E., Oxley, L., & Asbury, K. (2021). My brain feels like a browser with 100 tabs open: A longitudinal study of teachers’ mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1), 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12450.

Kossinets, G. (2006). Effects of missing data in social networks. Social Networks, 28(3), 247–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2005.07.002.

Kress, L., Bristle, M., & Aue, T. (2018). Seeing through rose-colored glasses: How optimistic expectancies guide visual attention. PLoS One, 13(2), e0193311. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193311.

Lee, A. S., Datu, J. A. D., Chan, D. K., Lau, E. Y. H., Fung, W. K., Cheng, R. W., Cheung, R. Y. M., & Chung, K. K. H (2023). The effects of a PROSPER-based intervention on well-being among pre-service preschool teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A randomized control trial. Educational Psychology, 43(2–3), 228–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2023.2189649.

Liou, Y. H., & Daly, A. J. (2018). Broken bridges: A social network perspective on urban high school leadership. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(5), 562–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-01-2018-0010.

Lomas, T., Waters, L., Williams, P., Oades, L. G., & Kern, M. L. (2021). Third wave positive psychology: Broadening towards complexity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(5), 660–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1805501.

Malouff, J. M., & Schutte, N. S. (2017). Can psychological interventions increase optimism? A meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(6), 594–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1221122.

Mattern, J., & Bauer, J. (2014). Does teachers’ cognitive self-regulation increase their occupational well-being? The structure and role of self-regulation in the teaching context. Teaching & Teacher Education, 43, 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.05.004.

McCallum, F., & Price, D. (2010). Well teachers, well students. Journal of Student Wellbeing, 4(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.21913/jsw.v4i1.599.

McCallum, F., Price, D., Graham, A., & Morrison, A. (2017). Teacher wellbeing: A review of the literature. Association of Independent Schools of NSW. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017/10/apo-nid201816-1133141.pdf.

Mehdinezhad, V. (2012). Relationship between High School teachers wellbeing and teachers efficacy. Acta Scientiarum Education, 34(2), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.4025/actascieduc.v34i2.16716.

Milfont, T. L., Denny, S., Ameratunga, S., Robinson, E., & Merry, S. (2008). Burnout and wellbeing: Testing the Copenhagen burnout inventory in New Zealand teachers. Social Indicators Research, 89, 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9229-9.

Morelli, S. A., Lieberman, M. D., & Zaki, J. (2015). The emerging study of positive empathy. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 9(2), 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12157.

NZEI Te Riu Roa (2023). Open letter to minister of education Jan Tinetti. https://www.nzeiteriuroa.org.nz/assets/downloads/Principals-Open-Letter-to-Education-Minister-Jan-Tinetti.pdf.

O’Connell, B. H., O’Shea, D., & Gallagher, S. (2016). Enhancing social relationships through positive psychology activities: A randomised controlled trial. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(2), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1037860.

O’Connor, S., & Cavanagh, M. (2013). The coaching ripple effect: The effects of developmental coaching on wellbeing across organisational networks. Psychology of Well-Being: Theory Research and Practice, 3(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/2211-1522-3-2.

OECD (2019). TALIS 2018 results (1): Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners. https://doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en.

Paterson, A., & Grantham, R. (2016). How to make teachers happy: An exploration of teacher wellbeing in the primary school context. Educational and Child Psychology, 33(2), 90–104. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2016.33.2.90.

Pfister, I. B., Jacobshagen, N., Kälin, W., & Semmer, N. K. (2020). How does appreciation lead to higher job satisfaction? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 35(6), 465–479. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmp-12-2018-0555.

Price, D., & McCallum, F. (2015). Ecological influences on teachers’ well-being and fitness. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 43(3), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866x.2014.932329.

QSR International Pty Ltd (2018). NVivo (Version 12) [Computer software]. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

Quinn, R. W., & Dutton, J. E. (2005). Coordination as energy-in-conversation. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 36–57. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2005.15281422.

Rahm, T., & Heise, E. (2019). Teaching happiness to teachers-development and evaluation of a training in subjective well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02703.

Ripley, R. M., Snijders, T. A. B., Boda, Z., Vörös, A., & Preciado, P. (2023). Manual for RSiena (version February 2023). University of Oxford, Department of Statistics, Nuffield College.

Robins, G. (2015). Doing social network research: Network-based research design for social scientists. SAGE Publications Ltd. (Online at UoA.

Rodway, J., & Farley-Ripple, E. (2020). Shifting our gaze: Relational space in professional learning network research. In L. Schnellert (Ed.), Professional Learning networks: Facilitating Transformation in Diverse contexts with Equity-seeking communities (pp. 171–192). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Ryff, C. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069.

Sapin, M., Widmer, E. D., & Iglesias, K. (2016). From support to overload: Patterns of positive and negative family relationships of adults with mental illness over time. Social Networks, 47, 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2016.04.002.

Seligman, & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.5.

Seligman, Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410.

Sinnema, C., Liou, Y. H., Daly, A., Cann, R., & Rodway, J. (2021). When seekers reap rewards and providers pay a price: The role of relationships and discussion in improving practice in a community of learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 107, 103474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103474.

Sinnema, C., Daly, A., Rodway, J., Hannah, D., Cann, R., & Liou, Y. H. (2023). Improving the Relational Space of Curriculum Realisation: Social Network Interventions. Emerald.

Snijders, T. A., Van de Bunt, G. G., & Steglich, C. E. (2010). Introduction to stochastic actor-based models for network dynamics. Social Networks, 32(1), 44–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2009.02.004.

Sottimano, I., Guidetti, G., Converso, D., & Viotti, S. (2018). We cannot be forever young, but our children are: A multilevel intervention to sustain nursery school teachers’ resources and well-being during their long work life cycle. Plos One, 13(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206627.

Spillane, J. P., & Shirrell, M. (2017). Breaking up isn’t hard to do: Exploring the dissolution of teachers’ and school leaders’ work-related ties. Educational Administration Quarterly, 53(4), 616–648. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161x17696557.

Stadtfeld, C., Snijders, T. A., Steglich, C., & van Duijn, M. (2020). Statistical power in longitudinal network studies. Sociological Methods & Research, 49(4), 1103–1132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124118769113.

Steiner, E. D., & Woo, A. (2021). Job-related stress threatens the teacher supply. Rand Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA1100/RRA1108-1/RAND_RRA1108-1.pdf.

Stuff (2023). Teachers across the country hold historic joint strike action. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/education/300830305/teachers-across-the-country-hold-historic-joint-strike-action.

Sun, J., Harris, K., & Vazire, S. (2019). Is well-being associated with the quantity and quality of social interactions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119, 1478–1496. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000272.

van Agteren, J., Iasiello, M., Lo, L., Bartholomaeus, J., Kopsaftis, Z., Carey, M., & Kyrios, M. (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(5), 631–652. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01093-w.

van Zyl, L. E., Gaffaney, J., van der Vaart, L., Dik, B. J., & Donaldson, S. I. (2023). The critiques and criticisms of positive psychology: A systematic review. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2023.2178956.

Wang, H., Hall, N. C., & Taxer, J. L. (2019). Antecedents and consequences of teachers’ emotional labor: A systematic review and meta-analytic investigation. Educational Psychology Review, 31(3), 663–698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09475-3.

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications. Cambridge.

Wylie, C., & MacDonald, J. (2020). What’s happening in our English-medium primary schools: Findings from the NZCER national survey 2019. NZCER.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Sage.

Yin, H., Huang, S., & Lv, L. (2018). A multilevel analysis of job characteristics, emotion regulation, and teacher well-being: A job demands-resources model. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2395. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02395.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the research ethics committee at the corresponding author’s institution.

Informed Consent