Abstract

This study investigates self-deceptive enhancement (SDE) as a control for response style in measuring positive psychology constructs, focusing on work engagement and three self-reported individual performance components. Addressing the critiques of positive psychology, particularly its reliance on self-report measures and susceptibility to method variance, we examine the role of SDE—characterised by unconsciously inflated self-perceptions—in self-reported surveys. Using latent variable modelling with different model specifications, we assess the impact of controlling for SDE in the relationship between work engagement and self-reported performance outcomes in a sample of small and medium enterprise employees. Our results show that the baseline model, not accounting for SDE, indicates statistically significant paths between work engagement and all three performance outcomes. However, when SDE is controlled for as a marker variable or a predictor, these relationships change significantly, with a notable reduction in the explained variance for two of the three performance components. The results highlight how SDE can impact substantive findings, underscoring the importance of considering controlling for SDE as an unconscious response style in positive psychology research. All in all, controlling for SDE may become necessary for improving the accuracy and consistency of research results in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The critiques of positive psychology, including issues surrounding the measurement and operationalisation of constructs, are particularly pertinent to this study. For example, the field has been criticised for an overinflation of associations (i.e., multicollinearity) between positive constructs (see Van Zyl et al., 2023, for an overview). Given the overreliance on self-report measures in positive psychology research (e.g., Diener, 2012; Qureshi & Evangelidou, 2018), its variables are particularly prone to method variance (Spector, 2021; Spector et al., 2019). Several method variance sources exist, including social desirability (Podsakoff et al., 2003; Spector et al., 2019), which reflects a tendency by respondents to portray an overly positive image of their selves (Uziel, 2010).

Suggestions on how to reduce or eliminate social desirability vary by usefulness and applicability. Probably the most direct approach is to reduce the need to produce desirable responses, by, for example, anonymizing the reports or wording survey items in a relatively neutral tone. However, this is not always feasible (e.g., in real-life screening processes), thus some advocate using indirect measurement approaches, such as asking people to report how other people, not themselves, behave (Yang et al., 2017). Others criticise the validity of this approach and advocate incorporating direct measures of social desirability (e.g., social desirability scales; Bernardi & Nash, 2023). Previous findings (e.g., Röhner et al., 2023; Uziel, 2014) and our current approach explore a nuanced perspective on this suggestion, noting that some scales of social desirability, such as those measuring self-deception, are more useful than others in controlling bias (Uziel, 2010).

Self-deceptive enhancement (SDE) is a facet of social desirability characterised by an unconscious bias towards positively inflated self-perceptions (Paulhus, 1984, 1991). The unconscious nature of SDE, as opposed to the more deliberate actions in impression management (IM), suggests a subtle yet potentially significant influence on self-report measures (Uziel & Cohen, 2020). Indeed, our focus is explicitly on SDE, as it is arguably suitable for controlling response style in positive psychology research. This suitability stems from two sources: First, SDE is inward-directed, thus particularly relevant in employee surveys, which are generally not regarded as high-stakes tests. Second, and importantly, in more recent studies, SDE has emerged as a more reliable measure of social desirability bias than IM (e.g., Uziel, 2010, 2014).

Research indicates that SDE is associated with individuals attributing excessively positive qualities to themselves, especially concerning agency, self-esteem, and adaptiveness (Paulhus, 1984; Uziel, 2010, 2014). This aspect becomes crucial when considering the authenticity of responses and the potential over-reporting of positive attributes in survey research (a form of response bias), especially when positively phrased items about the self are answered. Spector et al. (2019) opine that, although affect/attitudinal measures are prone to method bias due to their self-reported nature, individuals are often the most knowledgeable about internal states. Van der Vaart (2021) and Widyastuti and Hidayat (2018) posed similar arguments regarding performance. However, to counteract the potential adversity of method variance in self-reporting, we believe researchers should make attempts, when possible, to control for them in statistical models (Podsakoff et al., 2003; Spector et al., 2019).

This study delves into how SDE impacts responses in psychological surveys, particularly with positively worded Likert-type scale items. Individuals with an overly inflated sense of self, indicative of SDE, are more inclined to agree with positive statements about themselves, aligning with their enhanced self-view (Uziel & Cohen, 2020). Arguably, there is a potential bias at work, which, given a common self-reported method, could inflate relationships or even create the impression of relationships when non-existent.

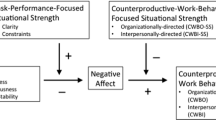

To verify this assumption, we investigated SDE as a potential source of response bias in this study with real-world data by employing it as a ‘control variable’ in different models, such as the marker variable technique within a latent variable modelling framework (Williams et al., 2015). This methodological approach could allow for a more precise interpretation of the actual relationships within models with positive psychological constructs, thereby significantly enhancing the validity of findings. This study used the well-known work engagement and self-reported performance relationship (Kim et al., 2013) as an example to test our assumption. Work engagement is a positive, work-related state of mind characterised by vigour, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). Performance is multidimensional, focusing on proficiency (i.e., performing assigned tasks), proactivity (i.e., anticipating and initiating changes), and adaptivity (i.e., responding to change) (Griffin et al., 2007).

By investigating the relationship between SDE and positive psychological constructs, this study aimed to illuminate how this unconscious component of socially desirable responding may bias self-reported experiences in the workplace. The research also sought to explore the broader implications for the validity and reliability of survey research in positive psychology. This study critically assessed whether the field should adjust for the influence of SDE to ensure accurate parameter estimates and thereby provide solutions to the criticisms levelled at the field in this regard.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

For this investigation, we used secondary data from Mokgata et al. (2023). The data included employees from South African SMEs aged 18–64 with at least a high school qualification. After excluding 33 respondents for attention check failures and seven outliers, the final sample comprised 278 employees, with an average age of 29.30 years, working at their current organisation for about 39.60 months. Most respondents were African females (66.20% and 61.20%, respectively).

2.1.1 Measuring Instruments

SDE. The SDE scale measures social desirability with statements reflecting exaggerated claims of positive attributes, mostly related to one’s agency, judgment, and rationality (Paulhus, 1991). Our shortened scale of SDE used 5 of the 20 items that make up the SDE sub-scale of the Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (BIDR-6; Paulhus, 1991). In choosing the items we considered five studies that aimed to validate abbreviated BIDR-6 versions (i.e., Asgeirsdottir et al., 2016; Hart et al., 2015; Leite & Beretvas, 2005; Pauls & Stemmler, 2003; Stöber et al., 2002). Due to discrepancies in item selection across these studies, we opted for the five items common to at least four validation studies. The items were: “I always know why I like things”, “I never regret my decisions”, “I am very confident of my judgments”, “I am a completely rational person”, and “I sometimes lose out on things because I can’t make up my mind” (reversed scored). A high score portrays individuals who lack (or deny having) self-doubts and who think highly about themselves as rational and decisive individuals. What makes the scale a measure of self-deception is that external observers cannot vet the content (as opposed to questions about overt behaviour, such as littering or gossiping, as in the Impression Management sub-scale of the BIDR; Paulhus, 1991). Responses were given on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (Not true) to 7 (Very true). Higher scores indicate more SDE. Composite reliability was found to be acceptable: 0.713.

Work engagement was measured with the ultra-short version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-3; Schaufeli et al., 2019). Each item measures a core aspect of the construct: vigour, dedication, and absorption. An example item (vigour) is “At work, I am bursting with energy”, and all items are measured on a seven-point scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 6 (Always). Composite reliability was calculated: 0.821.

The Work Role Performance scale (WRP; Griffin et al., 2007) was used to measure self-reported individual performance. Therefore, we used nine of the 27 items that measure an individual’s proactivity (e.g., “initiated better ways of doing your tasks”; three items), adaptivity (e.g., “adapted well to changes in core tasks”; three items), and proficiency (e.g., “ensured your tasks were completed properly”; three items). The self-report questionnaire uses a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). Composite reliabilities for all three components were acceptable: 0.824, 0.753, and 0.903.

3 Analyses

We used latent variable modelling with Mplus 8.10 (Muthén & Muthén, 2023) to investigate four models in this study. Latent variables are advantageous because measurement error is controlled for - assuming unequal item weightings (Hoyle, 2023). Specifically, we used confirmatory factor analyses and mean- and weighted least squares estimation to model the variables in all iterations of our structural models. The standard model evaluation criteria were considered for model fit, such as the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) > 0.90, and standardised root mean squared residual (SRMR) and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08 (Wang & Wang, 2020). However, it should be noted that RMSEA has been shown to underperform with this estimation method, and SRMR should be preferred (Shi et al., 2020). We set an alpha level of 0.05 for statistical significance (p <.05) for all parameters. Specifically important in this study is the size of correlations between the latent variables in each model. One would expect a decrease in correlation sizes if SDE had an effect from one model to the next. By extension, we were also interested in the explained variance (R2) in the outcome variables and how the different model specifications might change this. We used Cohen’s guidelines for effect sizes as concerns r and R2 (Cohen, 1992).

In the first model (Model 1), we modelled the work engagement and work role performance variables without any attempt to control for SDE to establish a baseline model to ascertain the explained variance in the dependent variables. In our second model (Model 2), we added the SDE variable as a marker variable that is uncorrelated with work engagement and the work role performance factors. However, work engagement and the work role performance factors remain correlated. This approach involves integrating the marker variable items (SDE) as indicators of a separate latent factor and including all other items in it as well. This factor is specifically designed to capture common method variance or, in this case, the SDE response style. By constraining the correlations between this SDE marker variable factor and its relation to other latent variables to zero, we effectively isolate the method variance, ensuring that it does not confound the relationships among our primary constructs of interest that remain correlatedFootnote 1.

In our third model (Model 3), we controlled for SDE by using it, by itself, as an uncorrelated factor, predicting each of the observed indicators. We demonstrate with this approach that this model and the previous model (Model 2) provide equivalent results as they are the same model just coded in a different way in MplusFootnote 2. In our fourth model (Model 4), we use SDE as a control variable specified to predict all the other latent variables in the model, also testing its influence at the latent variable level and not the item level. In our fifth and last model (Model 5; variant of Model 4), we constrain the structural paths from SDE to these other latent variables to be zero– providing us with a hierarchical type of regression model that considers the changes in explained variance. The Mplus syntax for these models are available as supplementary material: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/7GK38

4 Results

Table 1 presents the fit statistics for the various iterations of our model.

As evidenced, Models 1 through 4 demonstrate adequate fit to the data. Model 5, a modification of Model 4, shows less than adequate fit. However, in this iteration, we implemented a constraint on the paths from SDE to the latent variables, setting them to zero. This adjustment was part of a systematic procedure to evaluate the influence of SDE on the variance (R2) within these models. The resultant changes due to this modification are detailed below.

Table 2 presents the factor loadings for all the models.

As can be seen, the parameters of Models 1 (baseline without SDE) and 5 (SDE constrained to zero in the structural model) are equivalent (SDE included but constrained to have a zero effect). Model 2 (marker variable containing SDE item and all the other items) and Model 3 (SDE as a latent variable predicting all the other observed indicators in the model) are also equivalent in terms of parameters.

Table 3 presents the significance of the standardised betas and the explained variances in the models’ dependent variables.

In the baseline model (Model 1), which excludes the SDE variable, statistically significant paths were identified from work engagement to all individual performance outcome variables, each exhibiting a medium effect size. Contrastingly, Model 2 (using the SDE marker variable and yielding results equivalent to Model 3) revealed intriguing findings. Despite the standardised betas indicating statistically significant relationships, two out of three performance outcomes demonstrated a reduction in explained variance, which was also not statistically significant. The exception was task proactivity, which maintained a statistically significant pathway and explained variance (β = 0.290; p <.001; R2 = 8.40%; p =.020).

Considering the results of Models 4 and 5, SDE accounts for almost an equivalent amount of variance in the two performance outcomes (task proficiency and adaptivity) compared to work engagement. These observations suggest that SDE, as a response style, can substantively influence the paths between work engagement and self-reported performance to the degree that it may change the substantive conclusions of a study.

5 Discussion

This report explored the role of SDE as a control for response style in measuring positive constructs, particularly those susceptible to unconscious social desirability in self-reports. We focused on work engagement and individual performance as example variables. Our findings indicate that SDE significantly impacts these associations.

This study indicates that SDE is a key factor that should be considered in explaining variance in self-reported performance measures, aligning with management research perspectives (Spector et al., 2019), emphasising the potential impact of this expression of response bias in self-report surveys (Uziel, 2014). Without controlling for SDE, our models suggested strong relationships between work engagement and performance outcomes. However, when controlling for SDE—either as a marker variable or by having it predict all observed indicators—the significances of these relationships were altered.

Specifically, while significant beta coefficients remained, their values reduced, and the explained variance in two out of three performance components were no longer statistically significant, leading to a rejection of two initial expectations, that is, that work engagement would be useful in explaining variance in all three components of performance. Comparing hierarchical type models—one where SDE predicts outcomes and another constraining these relationships to zero—revealed that SDE accounts for nearly the same variance in the performance components as work engagement, except for proactivity. Nevertheless, the relationship and explained variance remained significant (albeit weaker) for the proactivity component, suggesting only a small impact of SDE on this type of performance in our sample. This could stem from the content of the SDE scale, which is more focused on adaptiveness and doing things ‘right’ than on (biases related to) initiating action. However, recent research has suggested avoiding interpreting the marginal effects of control variables and concentrating on the primary relationships of interest (see Hünermund & Louw, 2023), in this case, the relationships between work engagement and the performance variables. Indeed, work engagement has shown to be associated with other forms of proactive behaviour, such as job crafting (Meijerink et al., 2020) and presumably to person-job fit through job crafting (De Beer et al., 2016).

From a broader perspective, our findings imply that ignoring social desirability may lead to biased reports that may distort the true correlations between substantive variables (by either enhancing or suppressing true associations). Increased awareness of this reality and the need to address it is an important implication because this problem is often overlooked (e.g., as noted in Yang et al., 2017). Although our findings about SDE are promising, it is clear that a single method cannot eliminate the problem (but only attenuate its impact) and that a range of activities needs to be taken in the design of scales (e.g., by phrasing items to be more neutral in terms of desirability), administration settings (e.g., by assuring anonymity), and post-administration statistical controls (e.g., with effective social desirability scales, as applied here) to offer a better and more elaborate solution. A third implication is that more diversity is needed in measuring constructs, by, for example, adding others’ reports to self-reports and by exploring observable behaviours, thereby also reducing the impact of social desirability (e.g., Spector et al., 2019).

5.1 Limitations and Recommendations

First, the study’s cross-sectional nature limits the ability to draw causal inferences. However, simultaneous measurement of the SDE and the variables of interest (work engagement and subjective performance) is advantageous for control purposes– as they are measured on the same occasion. Nevertheless, investigating the stability of SDE over time and its longitudinal relationship with positive constructs could provide deeper insights. Second, while our focus was on SDE as an unconscious phenomenon, other control variables facets of social desirability could also warrant examination (see Mändli & Rönkkö, 2023). A novel approach is proposed in a recent study by Miller and Simmering (2023), who developed an ‘attitudes towards the colour blue’ scale as a proposed marker variable. Combining this with SDE in future research could yield intriguing results. Third, researchers should also explore some of these relations in real-life settings (i.e., high-stakes conditions) and use objective (or external) measures of performance, which would allow checking whether SDE suppresses the associations between self-reported engagement and (actual) performance. Fourth, it is important to acknowledge that SDE can play a role in other areas of psychology where many other positively worded items and scales exist. Researchers from other disciplines of psychology are encouraged to use SDE as a control variable where they consider it appropriate. Lastly, the data were collected in South Africa, and there may be unique cultural differences in how SDE manifests, which should be investigated using measurement invariance implementations with other countries.

6 Conclusion

This report underscores the importance of considering controlling for SDE as an unconscious response style in accurately measuring positive psychology constructs. To enhance the validity of findings, researchers should include appropriate controls for response styles in their studies, using them– at least - for sensitivity analysis. SDE shows promising results and may play an important future role in addressing criticisms of measurement and methodology in positive psychology (see Van Zyl et al., 2023). Researchers can compare results with and without SDE, when appropriate, to add perspective to research findings.

Notes

This is an essential difference between this type of model and a bifactor model, where the remaining (specific) factors would also be constrained to be uncorrelated (orthogonal).

Depending on model specification, the equivalent values will be under the factor loadings (BY) or regression output (ON).

References

Asgeirsdottir, R. L., Vésteinsdóttir, V., & Thorsdottir, F. (2016). Short form development of the Balanced Inventory of Desirable responding: Applying confirmatory factor analysis, item response theory, and cognitive interviews to scale reduction. Personality and Individual Differences, 96, 212–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.083.

Bernardi, R. A., & Nash, J. (2023). The importance and efficacy of controlling for social desirability response bias. Ethics & Behavior, 33(5), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2022.2093201.

Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current. Directions in Psychological Sciences, 1(3), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783.

De Beer, L. T., Rothmann, S. Jr., & Mostert, K. (2016). The bidirectional relationship between person-job fit and work engagement: A three-wave study. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 15(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000143.

Diener, E. (2012). In S. J. Lopez (Ed.), Positive psychology: Past, present, and future. & C. R. Snyder (Ed.). The Oxford Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 6–12). Oxford University Press.

Griffin, M. A., Neal, A., & Parker, S. K. (2007). A new model of work role performance: Positive behaviour in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 327–347. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24634438.

Hart, C. M., Ritchie, T. D., Hepper, E. G., & Gebauer, J. E. (2015). The balanced inventory of Desirable responding short form (BIDR-16). SAGE Open, 5(4), 215824401562111. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015621113.

Hoyle, R. H. (Ed.). (2023). Handbook of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Hünermund, P., & Louw, B. (2023). On the nuisance of control variables in causal regression analysis. Organizational Research Methods. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/10944281231219274.

Kim, W., Kolb, J. A., & Kim, T. (2013). The relationship between work engagement and performance: A review of empirical literature and a proposed research agenda. Human Resource Development Review, 12(3), 248–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484312461635.

Leite, W. L., & Beretvas, S. N. (2005). Validation of scores on the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale and the Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65(1), 140–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164404267285.

Mändli, F., & Rönkkö, M. (2023). To omit or to include? Integrating the frugal and prolific perspectives on control variable use. Organizational Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.1177/10944281231221703. Advance online publication.

Meijerink, J., Bos-Nehles, A., & de Leede, J. (2020). How employees’ pro-activity translates high-commitment HRM systems into work engagement: The mediating role of job crafting. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(22), 2893–2918. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1475402.

Miller, B. K., & Simmering, M. J. (2023). Attitude toward the color blue: An ideal marker variable. Organizational Research Methods, 26(3), 409–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/10944281221075361.

Mokgata, N., van der Vaart, L., & De Beer, L. T. (2023). Autonomy-supportive agents: Whose support matters most, and how does it unfold in the workplace? Current Psychology, 42(27), 23931–23946. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03550-9.

Muthén, B., & Muthén, L. K. (1998–2023). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

Paulhus, D. L. (1984). Two-component models of socially desirable responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(3), 598–609. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.3.598.

Paulhus, D. L. (1991). In J. P. Robinson (Ed.), Measurement and control of response bias. P. R. Shaver, & Wrightsman, L. S. (Eds.). Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (pp. 17–59). Academic.

Pauls, C. A., & Stemmler, G. (2003). Substance and bias in social desirability responding. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(2), 263–275. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00187?3

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

Qureshi, A., & Evangelidou, S. (2018). Toward a culturally competent positive psychology. In N. J. Brown, Lomas, T., & Eiroa-Orosa, F. J. (Eds.). The Routledge International Handbook of critical positive psychology (1st) ed., pp. 263–280). Routledge.

Röhner, J., Thoss, P., & Uziel, L. (2023). Can people with higher versus lower scores on impression management or self-monitoring be identified through different traces under faking? Educational and Psychological Measurement. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131644231182598. Advance online publication.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.248.

Schaufeli, W. B., Shimazu, A., Hakanen, J., Salanova, M., & De Witte, H. (2019). An ultra-short measure for work engagement: The UWES-3 validation across five countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35(4), 577–591. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000430.

Shi, D., Maydeu-Olivares, A., & Rosseel, Y. (2020). Assessing fit in ordinal factor analysis models: SRMR vs. RMSEA. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 27(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2019.1611434.

Spector, P. E. (2021). Mastering the use of control variables: The hierarchical iterative control (HIC) approach. Journal of Business and Psychology, 36, 737–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09709-0.

Spector, P. E., Rosen, C. C., Richardson, H. A., Williams, L. J., & Johnson, R. E. (2019). A new perspective on method variance: A measure-centric approach. Journal of Management, 45(3), 855–880. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316687295.

Stöber, J., Dette, D. E., & Musch, J. (2002). Comparing continuous and dichotomous scoring of the Balanced Inventory of Desirable responding. Journal of Personality Assessment, 78(2), 370–389. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa7802_10.

Uziel, L. (2010). Rethinking social desirability scales: From impression management to interpersonally oriented self-control. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(3), 243–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610369465.

Uziel, L. (2014). Impression management (lie) scales are associated with interpersonally oriented self-control, not other‐deception. Journal of Personality, 82(3), 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12045.

Uziel, L., & Cohen, B. (2020). Self-deception and discrepancies in self-evaluation. Journal of Research in Personality, 88, Article 104008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104008.

Van der Vaart, L. (2021). The performance measurement conundrum. Construct validity of the individual Work performance questionnaire in South Africa. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 24(1), Article 3581. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v24i1.3581.

Van Zyl, L. E., Gaffaney, J., van der Vaart, L., Dik, B. J., & Donaldson, S. I. (2023). The critiques and criticisms of positive psychology: A systematic review. The Journal ofPositive Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2023.2178956.

Wang, J., & Wang, X. (2020). Structural equation modelling (2nd ed.). Wiley & Sons.

Widyastuti, T., & Hidayat, R. (2018). Adaptation of individual work performance questionnaire (IWPQ) into Bahasa Indonesia. International Journal of Research Studies in Psychology, 7(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsp.2018.3020.

Williams, L. J., & O’Boyle, E. H. (2015). Ideal, nonideal, and no-marker variables: The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) marker technique works when it matters. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(5), 1579–1602. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038855.

Yang, J., Ming, X., Wang, Z., & Adams, S. M. (2017). Are sex effects on ethical decision-making fake or real? A meta-analysis on the contaminating role of social desirability response bias. Psychological Reports, 120(1), 25–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294116682945.

Acknowledgements

Liad Uziel’s contribution was supported by a grant from the Israel Science Foundation (ISF grant No. 133/23).

Funding

Open access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

De Beer, L.T., van der Vaart, L. & Uziel, L. Should Positive Psychology Researchers Control for Response Style?. Int J Appl Posit Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-024-00150-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-024-00150-9