Abstract

Positive psychology is the scientific study of human thoughts, feelings and behaviour that focuses on building resources rather than treating illness. The current pilot study utilised qualitative methods to explore an intervention, ‘Tweens’, based on proven methods from positive psychology. Tweens was designed to be suitable for adolescents aged 11–14, who experienced symptoms of depression, anxiety, or stress. A defining feature of Tweens is that it included both the afflicted children and their parents, and is the first study to examine a positive psychology family intervention for this target group. Using Constructive Grounded Theory, this study sought to determine what meaning, if any, the participants ascribed to Tweens and how they integrated the methods into their daily lives. The study also investigated why some participants did not find the intervention meaningful or effective. The results show that the experienced meaningfulness of Tweens can be divided into three main categories: (1) A sense of belonging or togetherness, (2) The utility of the tools that were taught, and (3) An increased mindsight and learning how to choose actions mindfully. The results are discussed in light of the broaden-and-build theory: when parents and children have shared knowledge and vocabulary for talking about well-being, supportive upward spirals occur. All the adolescents did not perceive the intervention as meaningful, and we discuss variations in depressiveness, problematic life circumstances and possible flaws in the intervention as possible reasons for this.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Positive psychology is the scientific study of human feelings, thoughts, and behaviour that focuses on building the good instead of treating illness (Peterson, 2008). A focus on positive psychology themes, such as strengths, positive emotions, gratitude, resilience, hope, and social engagement, is directly linked to increased mental health and a tendency to set long-term goals that support psychological growth (Marques et al., 2011; Hutchinson & Pretelt, 2015), as well as health benefits, including greater longevity (Jeste et al., 2015).

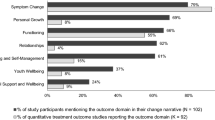

Although promising evidence from positive psychology and positive psychology interventions (PPIs) is starting to accrue (Turner et al., 2021; Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009; Boiler et al., 2013; Quinlan et al., 2012; Donaldson et al., 2014; Ghielen et al., 2018), we still know little about the mechanisms behind the desired changes in well-being from a participant perspective. The aim of this pilot study was to qualitatively examine the effects of one PPI model, looking at what the participants perceived to be the meaningful components of the intervention, what their personal take-away from the intervention was, and to determine the downsides or problems of the intervention from their perspective.

One aim of positive psychology has long been to promote relational growth and flourishing families (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Despite this, most studies have examined interventions targeting individuals (Waters, 2020) and limited research has been conducted on positive relationships overall (see e.g. Brauer and Proyer, 2023). By widening the perspective to integrate the relational system around the individual in the interventions, the aim could also expand to foster relational change over time (Doty et al., 2017). This is especially relevant in the treatment of children and adolescents, whose well-being is largely affected by the family system around them.

1.1 Positive Psychology Interventions for Children and Adolescents

Most research on PPIs has been conducted on adults, with encouraging results of increased well-being and reduced depressive symptoms (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009), but an increasing number of recent studies have focused on PPIs for children and adolescents (Turner & Mueller, 2021). For children, most of the PPIs that have been studied are school-based interventions, which have shown promising results in different cultural contexts. (Seligman et al., 2009; Adler, 2017; O’Connor et al., 2017; Boniwell et al., 2015; Fagerlund et al., 2021; Laakso et al., 2020; Ruini et al., 2006,).

The positive psychology community has requested further research addressing both typically developing children and clinical groups, for example, children with mental health difficulties (Weems, 2009). Both have the same aim of increasing well-being, life satisfaction and resilience. In addition, PPIs targeting clinical groups often use a reduction of symptoms as an additional outcome measure of intervention effectiveness. (Waters, 2020). There is a substantially smaller number of PPIs for specific clinical groups for children. The studies target adolescents with depression or anxiety (Teodorczuk et al., 2019; Jabbari et al., 2015), children showing symptoms of lowered mood (Kwok et al., 2016), adolescents experiencing a dip in subjective well-being (Tomyn et al., 2015), children rating sub-optimal life satisfaction (Suldo et al., 2014), and Latina/o adolescents aiming to prevent depression (Cavazos Vela et al., 2019). Most of these have shown encouraging results by decreasing depression (Jabbari et al., 2015; Kwok et al., 2016; Cavazos Vela et al., 2019), decreasing anxiety (Jabbari et al., 2015), decreasing stress (Jabbari et al., 2015), increasing life satisfaction (Jabbari et al., 2015; Kwok et al., 2016; Tomyn et al., 2015; Suldo et al., 2014; Cavazos Vela et al., 2019), and increasing resilience and positive recovery attitudes (Cavasoz Vela et al., 2019). However, follow-up data have shown that increased life satisfaction has subsided over time (Suldo et al., 2014).

One study did not find any significant effects on well-being, anxiety or depression, namely Teodorczuk et al.’s (2019) study of adolescents living in a youth care centre. While this could mean the PPI simply was not effective enough, another explanation could be that these adolescents did not have as much support, reassurance and encouragement as other adolescents living at home might have. Previous research has indicated that sufficient support is an important factor for positive outcomes (Allen & Vacca, 2010). In cases such as this, an in-depth qualitative investigation of the participants’ own experiences could have provided answers as to which aspects of the intervention they found meaningful and which they did not, which in turn could have explained the non-significant results. The authors of the study concluded that their quantitative study was not able to pick up the subtleties in behavioural and attitudinal change, and thus argue for the need for more qualitative PPI research, as this may yield important information. Moreover, this study speaks to the necessity of including the adolescents’ contexts into the interventions, such as families, guardians, or school personnel. This could be crucial for making changes in adolescents’ psychological health, as social support is such an important factor for experienced well-being.

Looking specifically at PPIs involving families, more interventions have been developed for children with some sort of difficulty, in comparison to typically developing children with no major life difficulties (Waters, 2020). Existing studies are heterogeneous, both in terms of intervention layout and which difficulty they have targeted. Some studies have examined families in poverty or other forms of deprivation (Meija et al.,. 2012; Ho et al., 2016a), families in therapy (Conoley, 2015), and families with children with specific challenges such as autism (Benn et al., 2012; Hwang et al., 2015; Ferraioli & Harris, 2013), type 1 diabetes (Kichler & Kaugars, 2015), or behavioural problems (Sanders et al., 2014). These studies show that family PPIs are effective.

The most common method used in family interventions is focusing on character strengths. A recent study of children in public mental health care showed that discharges were successful after participation in strength-focused treatment (Turner & Mueller, 2021). The intervention layout used by Conoley (2015), called Positive Family Therapy, was also strength based. Other family interventions not targeting clinical groups cover different positive psychology concepts such as goal-setting, meaning and family identity (Waters, 2020), gratitude, flow, joy, savouring, health, active listening (Ho et al., 2016a, b), and resilience (Doty et al., 2017). The results from these variations of family interventions have shown increases in subjective well-being (Waters, 2020; Ho et al., 2016a, b), enhanced positive family interaction (Ho et al., 2016a, b), improved parenting behaviours, and increased parenting confidence (Doty et al., 2017). No qualitative studies of family PPIs have been published, despite both Teodorczuk et al. (2019) Ho et al. (2016a) speaking to their necessity.

1.2 Purpose and Goals of Tweens

The Tweens study aimed to examine in depth a family PPI for adolescents experiencing internalising psychological difficulties such as anxiety, depressive symptoms, or stress. The Tweens curriculum was developed from the same research group’s earlier intervention ‘Flourishing Students’ (Fagerlund et al., 2021; Laakso et al., 2020). The curriculum incorporated many of the elements of the Personal Well-being Lessons (Boniwell & Ryan, 2012; Boniwell et al., 2015) as well as many more theories and methods from the field of positive psychology (see e.g. Dweck, 2006; Fox Eades, 2008; Fredrickson, 1998, 2001, 2013a, b; Lopez, 2014; Niemiec, 2014; Peterson and Seligman, 2004; Raknes, 2009; Rath & Clifron, 2009; Reivich and Shatté, 2002; Seligman et al., 2005, Seligman, 2011; Stallard, 2002, 2005). Tweens included parents in the treatment, enabling adolescents and parents to learn simultaneously about character strengths, noticing the good, positive communication, resiliency skills, and mindfulness, but in separate groups. Between the sessions, the families integrated their new knowledge into their home environments by doing shared practical exercises. Another main aim of Tweens was to promote relational growth. In practice, this meant helping whole families increase their positive and constructive relational behaviour and resilience. This would, in turn, hopefully result in flourishing families with increased well-being. To make the participants’ own voices heard, this study used an explorative Grounded Theory (GT) approach without pre-determined hypotheses. The aim of the present study was to let the participants formulate and express their thoughts about the Tweens intervention, and through their words articulate what meaning, if any, they ascribed to this type of intervention.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

The Tweens intervention was aimed towards adolescents aged 11–14 years, suffering from mild to moderate symptoms of depression, anxiety, or stress. A specific diagnosis was not needed to participate in the study, but mainly internalising symptomatology was chosen to prevent the group from being too heterogeneous. In total, ten adolescents partook in the study, of whom seven were girls and three were boys. The parents also participated in a simultaneous intervention. Eleven parents participated, of whom ten were mothers and one was a father. Three additional families participated in the intervention, but chose not to participate in the interviews, and were thus excluded from the study. Tweens was advertised to 11–14-year-olds suffering from anxiety, low mood, worry, stress, or loneliness, and to their parents, through school psychologists and care facilities treating adolescents. The participants were Swedish-speaking or bilingual families from the metropolitan area of Finland. When signing up, a research assistant conducted short semi-structured phone interviews with the parents, checking whether the intervention suited their needs, whether they fitted the inclusion criteria of mild to moderate internalizing symptomatology and informing them of the intervention layout and research aim. Reasons for excluding participants were age, mainly externalising symptomatology, and too severe symptomatology. Adolescents with signs of clear self-destructive behaviour, suicidality, and psychosis were excluded from this pilot study.

Before participating in the study, all but one of the adolescent participants filled in a survey. The Beck Youth Inventories (Beck et al., 2013) was used to assess the adolescents’ levels of anxiety and depression. In the Tweens study, the anxiety and depression scales were of particular importance for measuring the severity of their experienced symptoms. The results were analysed with cut-off points provided by the test manual, where a non-clinical group had been used to develop and standardise the Beck Youth Inventories (Beck et al., 2013). The scales and cut-off points cannot be used for diagnostic purposes but give important information on the adolescents’ experiences. On the anxiety scale, four participants had much heightened experiences of anxiety, three had some heightened experiences and two had an average amount. On the depression scale, five participants reported having much heightened experiences of depression, two some heightened experiences and two had an average amount. Adolescent self-esteem was measured using the ‘I think I am’ questionnaire (Birgerstam, 2013). Eight of the adolescents had average self-esteem, three slightly low and one very low. Table 1 presents qualitative descriptions of the participants’ symptomatology as described by their parents.

The participants have been given pseudonyms. The parents’ pseudonyms are surnames whereas the adolescents’ pseudonyms are first names, so that the parents are easily distinguishable from their children. The genders of the pseudonyms were randomly assigned so that every other participant was assigned a male and every other a female pseudonym. This does not correspond with the actual gender distribution and was done deliberately to guarantee the participants’ full anonymity.

2.2 The Tweens Intervention

2.2.1 Procedure

The Ethics Review board for the Humanities and Social Behavioral Sciences at the University of Helsinki reviewed and approved the research plan. The participants were informed of the research purpose in advance, and of their right to withdraw their consent at any time. The adolescents and their parents participated in the intervention simultaneously but in separate groups. The layout for the intervention was developed mainly from the same research group’s earlier interventions ‘Flourishing Students’ (Fagerlund et al., 2021; Laakso et al., 2020) and ‘Flourishing Families’ (Pentti et al., 2019). The material and exercises were adapted to fit the format and time available for Tweens. Tweens was planned and executed as an eight-part intervention, consisting of weekly two-hour sessions. The contents and exercises of the child group and the parent group mirrored each other, and each week the families had joint homework exercises. Table 2 presents a summary on the contents of the intervention.

The intervention was conducted twice, once in the autumn of 2018 and once in the spring of 2019. Five families participated in the autumn intervention and eight in the spring. The child groups were led by two leaders, whereas the parent group had two leaders for the autumn group and one for the spring group, due to a shortage of staff. The leaders had different educational backgrounds in the field of health care and had received relevant internal training of positive psychology methods within the research group. The interventions were designed to allow much time for discussion and exercises, and for teaching the participants positive psychology concepts.

2.2.2 Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected continuously throughout the intervention to collect information on the participants’ meaning-making process. At the beginning of the intervention, the participants filled in forms containing questions on their expectations and hopes for Tweens as well as their own reasons for applying. The purpose of this form was to find any possible meaning that they ascribed to Tweens prior to the intervention. After the intervention, the participants were invited to participate in family interviews.

The family interviews were semi-structured and designed to elicit meaning, but followed the participants’ lead to deepen the understanding of what they found meaningful in the experience. If the interviews came to a halt, the interviewer proceeded by bringing up parts of Tweens not yet mentioned in the discussion. The interview mainly consisted of topics such as the participants’ attitudes at the beginning, the effects that Tweens had on them, their parent-child interplay and what they learned from the process. The support structure for the interviews is found as an appendix. Afterwards, the interviews were transcribed and read through several times to establish familiarity with the content. Subsequently, line-by-line coding made common themes emerge from the data. The codes and emerging themes were compared and synthesised through memo-writing. The first memos only compared answers within the families, but as the analysis deepened, they started comparing similarities and differences between parents and between children. Understanding of the adolescents’ symptomatology, observations, and quantitative data was woven in to enable understanding the different outlooks of the families and participants.

When the initial line-by-line coding was completed, we began a more focused coding. We categorised the codes by a process of colour-coding of the memos for similar meanings and experiences. We tried out, compared and adjusted categories to make analytic sense and stay true to the participants’ original statements. To do this, we elaborated and rethought the memos and wrote new memos containing synthesised understandings of all the material. These more refined memos, taking all codes and categories and their internal connections and distinctions into account, worked as a basis for the final analytical report. The final categories are presented in the analysis section and a discussion of the strengths and limitations of the analysis process in the conclusion section.

2.3 Grounded Theory

The Tweens intervention used Grounded Theory (GT), a qualitative method for collecting and analysing participants’ experiences. As the Tweens intervention is a pilot study of a new model of positive psychology group treatment, it is important to let the participants’ own descriptions be the starting point for the analysis. GT is characterised by certain systematic methodological strategies: a process of simultaneous involvement in data collection and analysis. The aim is to collect more data for deepening the understanding of what emerges from the material until reaching a point when more data no longer contribute anything new to the understanding of the phenomena. In GT, the researcher usually has no fixed research questions at the onset, but a guiding interest or topic of inquiry, letting the participants provide the problem description through what they bring forth during the interviews. GT procedures include intensive interviewing, shaping interviews after the participants’ stories and more targeted interviewing as the research deepens (Charmaz, 2014, 2015). However, not all aspects of the current study are in line with the original GT model, as the general aim was not to generate a formal theory, but to construct a conceptual analysis of this specific experience. Moreover, we were unable to keep finding new informants to inform the growing analysis until saturation was reached, as the number of possible informants was limited to the participants of the two pilot study intervention groups. Charmaz (2015) points out, however, that this is a possible and valid way of using GT.

Furthermore, GT has developed into Constructivist Grounded Theory (CGT). With a CGT approach, researchers are acknowledged as co-constructors of the data, and their theoretical proclivities and interaction with the informants shape the collection, content, and analysis of the data. As researchers, we were highly involved in planning, conducting, interviewing, and analysing the intervention. As we conducted this study, we were consciously aware of our constructivist stance.

3 Results

The participants found meaning in Tweens in both similar and different ways. A close look at their statements revealed three main themes. The first theme was a sense of belonging, a feeling of togetherness with others in the group and openness towards each other. The second theme was related to the tools that were taught, and how these had helped the participants develop wider appreciation, hope, and compassion. The third theme was related to increased awareness of the present moment and self-understanding, which had helped the participants to pause and choose their actions more deliberately. This kind of awareness could be described by the term mindsight, coined by Siegel (2010), which will be described later.

3.1 Belonging

A central reason for both parents and adolescents finding Tweens meaningful is that it gave them a sense of belonging or togetherness. This was the most frequently mentioned aspect of meaning; both groups described a surprising openness, leading to a sense of belonging, and a sense of joint action and togetherness within the families participating in Tweens. Still, about one third of the adolescents did not feel this sense of belonging. Some of them stated that the adolescents did not really bond and that there could have been a stronger sense of togetherness if there had been more fun activities. Others mentioned the uneven age or gender distribution as factors affecting their sense of belonging: some perceived the material as too difficult or too easy, while others wished there had been other peers of the same gender in their group. Figure 1 summarises the subcategories that emerged for this theme.

3.1.1 Openness

When the participants talked about belonging, many used the word ‘openness’. Several parents expressed amazement for how deeply they were able to share personal stories and how fast a sense of safety was formed in the parent group. Some gave credit to good leadership, while others stressed that the participants being strangers before Tweens started made it easier to open up as they were not afraid of being judged. Mr Williams stated that openness is a skill that must be practised, and that Tweens promoted this. Among the adolescents, Michaela and Timmy mentioned the fact that the group was small. Having things in common also facilitated openness and belonging. Michaela put it this way:

I think it was easier when it was quite a small group. And then that everybody had pretty similar problems, or yeah, like the same things that we came here for. (…) Many had sleeping difficulties and like, a little bit of anxiety, perhaps?

In other words, she found it meaningful to be able to talk to other adolescents of her age about mental health topics. Anna also reasoned along similar lines, that it was interesting to hear what others’ lives were like. Tweens gave her more reference points and widened her perspective of other people’s struggles. Lisa also ascribed meaning to Tweens because of the open atmosphere. She had no friends at school, and appreciated the safe, relaxed, and fun environment that Tweens provided. Our interpretation is that when participants dare to be vulnerable, it reduces their feelings of shame, isolation and being different. This, in turn, creates a sense of belonging, togetherness and trust within the group. Openness was something participants also expressed they had hoped for beforehand, and therefore appreciated it when they experienced it.

3.1.2 Togetherness in the Child Groups

Approximately two thirds of the adolescents felt a sense of belonging and reported it as an important factor as to why Tweens was meaningful to them. When Charlie was asked whether he had felt any emotion more often due to Tweens he replied ‘togetherness’. When asked what the best part of Tweens was, Anna answered ‘maybe it was that everybody listened to each other’. For them and many others listening, telling your own stories and feeling heard were factors that created a sense of belonging. However, not all the adolescents felt this way. Timmy said he did not share much about himself, nor did he feel that there was much spontaneous sharing from the other adolescents. In his opinion, they just answered the leaders’ questions. Michaela’s thoughts embraced the views of both Anna and Timmy, and shed light on why they might have perceived the same situation so differently. On the one hand, she stated that everybody listened to each other, and that they received support from one another, but on the other hand, she also said that they did not really talk to each other if it was not included in the task. Still, she thought that it had been important and meaningful for her to be able to talk freely about herself in her own words. Evidently, no genuine relationship or authentic connection seemed to have developed between the adolescents, especially among the participants in the spring group. Although this did not affect the feeling of belonging for some, others had hopes of finding new friends. Sophie and Lisa expressed disappointment in this regard. This shows that despite the facilitating of friendships not having been a preliminary goal of the researchers, it may have been for the adolescents.

The participants also appreciated the freedom and flexibility of Tweens, as an alternative experience of a positive group context, often in comparison to school. Lisa commented that it was a complete contrast from school, where there were constant demands that she could not meet and which contributed to her feelings of despair and hopelessness. In fact, all the adolescents in the autumn group seemed to enjoy themselves and laugh a great deal, especially during the breaks. One participant was sceptical before attending Tweens, but his parent told us that the scepticism disappeared after the first session. Another participant concluded that ‘It was nice because we could also hang out and then it didn’t have to feel like… Or you felt that you’re not alone.’ This statement is representative of the autumn group, but the adolescents in the spring group talked less about having fun together. Benny even felt that Tweens was boring and unnecessary. When asked how it could have been different, he said:

I don’t know really, but at least something happier, and it was also rather quiet there. (…) Can’t we do something that makes us happy in some other way than talking about exactly what the problem is? We might always have problems?

According to him, the atmosphere was too heavy, and the subjects discussed were too problem focused. The parent of another adolescent participating in the same group also noticed that the group cohesion was weak and suggested that more group-building games and more activity overall could have helped the adolescents open up to each other and enjoy Tweens more. Another parent suggested that more physical activity could be helpful. These statements clearly show differences between the autumn and spring groups. Since the layout of the intervention was the same for both groups, the most probable reason for these differences was the group composition. Many of the participants in the spring group pointed out that the age distribution was quite wide, and the adolescents were on different levels of maturity, in contrast to the autumn group, in which the maturity levels of the adolescents was more even. However, Charlie from the autumn group also commented that he had much in common with the other adolescents, so in addition to maturity levels, similar interests could also help group cohesion. There were different leaders in the autumn and spring groups, and in the spring group one leader quit halfway through, which could also have impacted the adolescents’ experiences and sense of belonging to the group.

3.1.3 Peer Support in the Parent Groups

All the parents expressed appreciation for the atmosphere and the support they received from Tweens. A great deal of session time was allocated to peer support, and while some felt it took too much time in relation to the content and the tools being taught, many participants felt it was important and talked extensively about the specific value of peer support for parenting. Many parents felt that they were in similar situations and could thus support each other in problematic parenting situations. One parent applauded the leaders of the parent groups, who skilfully created a sense of safety and openness within the group, which enabled them to trust each other and share more. Another parent repeatedly described the intervention as very therapeutic:

We opened up to each other in pairs and talked about what problems we had and how we viewed things. (…) It was surprisingly beautiful to get to open up like that. Astonishingly nice therapy.

3.1.4 Joint Action Within the Families

Being a family intervention, Tweens aimed to help the adolescents from two directions: by directly treating the adolescents, and helping the parents better support their children. Many of the parents commented on this, appreciating the concept of being in different groups, but still working toward the same goal, creating joint actions with their child for the child’s well-being. This feeling seemed to be especially strong if participation in Tweens had come from the adolescent’s initiative or if the adolescent was eager to participate. Sharing the enthusiasm brought parents joy and made it meaningful to them. One participant expressed the following:

I think Tweens is about, with your child, reflecting on how we can feel good, and feel better together. (…) I think Tweens is about being together. Yes, and also being together with the other adults and listening to them.

The fact that the intervention provided time for parent and child to spend together was brought up frequently in the interviews. One adolescent who otherwise felt sceptical toward Tweens, admitted that time together with his parent was the only meaningful thing in the intervention. Other parents started looking for opportunities to spend more time with their children, while also being receptive and respectful of when the child signalled that they wanted time alone.

3.2 Tools

One goal of Tweens was to provide tools that the families could use in their everyday lives to promote psychological well-being. Some of the tools and exercises taught during Tweens are presented in Table 2. These tools and the changes they brought to the participants’ lives were often described as meaningful. This section is structured around the changes that the participants described as meaningful, namely a new vocabulary, seeing strengths, appreciation, hope, compassion, and health awareness. Health awareness will not be addressed any further in this paper, as it is connected to another measurement method, measuring heart rate variability, which does not fit into the scope of the current study. Figure 2 summarises the subcategories within the category regarding tools.

Concrete tools for making everyday life simpler and more exciting was the reason some of the participants signed up for Tweens. Mr and Mrs Thompson felt Tweens lived up to their hopes in this regard and believed these tools would have positive long-term effects on their son. The key concepts of positive psychology, such as strengths, mindfulness, and resilience, were new for some participants, but familiar to others. The parents who were familiar with the concepts commented that in many ways Tweens worked as a reminder to use this knowledge more often. Tweens seemed to confirm their view on how to promote both their own psychological health and that of their children. Some of the adolescents were also familiar with the concepts and agreed with their parents that Tweens was a reminder to use the knowledge.

3.2.1 New Vocabulary

The participants reported having gained new vocabulary. Having a shared language for psychological well-being and talking about it more shaped the culture at home and created new habits. Some families described how it became more normal to express appreciation and pride towards one another when they had the terminology to do so. Families also learned new ways of communicating about emotional states and about helpful and unhelpful thoughts in a concrete and understandable way. Michaela expressed that it helped her to understand her own thoughts and feelings, which could otherwise seem fleeting and abstract. Having new vocabulary for thoughts and feelings made them more neutral and externalised; not something you are but something you have. Some parents found meaning in the new vocabulary for resolving conflicts while supporting their children’s resilience and self-knowledge. However, when learning about the same topics of conflict-solving and resilience, many adolescents felt it was too complicated and impractical, especially when upset or angry. The adolescents generally reported gaining more from the strength or gratitude vocabulary.

3.2.2 Awareness of Strengths

Several participants mentioned becoming more aware and appreciative of both their own and other people’s strengths. A few participants expressed feeling proud when they became aware of new strengths within themselves. The strength-related topics in Tweens also helped the participants be more understanding towards one another. Mr Williams explained that what he used to perceive as negative behaviour in his son Charlie, he now saw as the flipside of a strength that he normally cherished, expressing an understanding of how strengths can be over- and underused. Mr Williams described Charlie as very enthusiastic, sociable, and eager to participate, but when he overused these strengths, he could become too impulsive and insensitive.

Many participants found the strength-based topics and exercises both meaningful and helpful. The participants especially appreciated hearing about their strengths from different people, even though some found it hard to ask others to describe their strengths. Sophie explained how even though she found it hard to ask people about her strengths, she started believing they might be true when many different people observed the same strengths in her. Lisa, in turn, had a hard time believing that the strengths others described in her were true, which her mother believed was because Lisa’s self-image with peers was based mostly on her school experiences, which were rather negative. Benny found it meaningless to pick out strengths for himself, since he felt the strengths did not matter. He did not see strengths in himself and using positive affirmations bothered him as he considered it unauthentic. He did not come up with anything positive to say about himself and he hated doing the exercise as it made him feel egoistic. Although he had difficulty seeing the good in himself, he agreed with his father that it was nice to hear observations of his strengths from others. He remembered well which strengths others saw in him and talked happily about their family strength tree.

3.2.3 Appreciation

Appreciation and gratitude are tools that many participants claimed to have taken to heart from Tweens. The exercise many brought up was the ‘what went well’ exercise, where you name three things you are thankful for about your child or family. Many of the families formed new habits around feeling and expressing gratitude, and some parents pointed out that being consistent in one exercise was better than implementing all the new tools with their children. They did mention that it was challenging to be consistent in the exercises when their children struggled with low moods and negative self-images, but they also believed it counterbalanced their negative bias to some extent. Mr Stone said, ‘Even if it’s been a shitty day, we don’t let it go until we’ve found three good things’. Another parent said that she noticed that the appreciation and gratitude exercises had led her to see more positive things.

For some, however, the effect of appreciation seemed to be short lived and in need of consistent expression to be effective. Mrs Jones mentioned seeing an increase in spontaneous kindness in herself and her daughter, but that the effect wore off with time. Benny criticised one of the exercises for providing only short-lived joy, but not really being helpful in the long run.

3.2.4 Hope and Mindset

During Tweens, one of the themes was resilience and this was approached by a mindset point of view. Both parents and adolescents were taught the differences between a fixed and a growth mindset, e.g., by the ‘helping hand’ exercise. In many interviews, a more dynamic or growth mindset was discernible among both parents and adolescents. They expressed agency and hope in being able to affect their lives with their own actions and ways of thinking, and some parents described changes they had already facilitated with the help of a more dynamic mindset. For example, Mr Williams expressed that hopefulness was something that could be improved through practice, and that he had already noticed this in himself because of the Tweens intervention and wanted to continue working on it.

The adolescents also showed development in terms of mindset and hopefulness, even though some described it as being difficult. Isak, who often used to put himself in emotionally charged situations, learned not to make a big deal out of everything and that this could prevent him becoming sad. During the interview, he stated that he now welcomes challenges, since he knows how to handle the situations. He has a new way of relating to his emotions, seeing challenging emotions as an area of growth and development and not just a burden. Michaela ascribed a sense of hope through her newly gained tools, since they could lead to a positive change, even though she felt it was still difficult to use them in the heat of the moment. She worded this in the following way:

In some situations, it doesn’t really work to think ‘Okay, I’m going to use this technique now’, or it’s difficult to use them. But it’s also good to know that when you do use them, the situation can develop into something better.

Nevertheless, awareness of positive and negative thoughts does not equal an ability to alter your way of thinking, and sometimes it is necessary to realise that an issue stems from a context rather than from the way a person thinks. Lisa described the lack of support at her school and stated that she would need more positive things around her, meaning that her mindset could only change so much.

3.2.5 Compassion for self and Others

Of the parents, Mrs Brown, Mr Smith and Mrs Taylor talked about self-compassion. They appreciated the focus on being kind to oneself and of being good enough. They explained how they finished Tweens feeling that their way of parenting was good enough, and that they could go on as before. Mrs Taylor reflected on self-compassion when forming high ambitions and placing demands on oneself: ‘(…) trying is good enough. You don’t have to get perfect marks in everything’. Her daughter Sophie partially embraced this, but still expressed fears that her performance at school would not be good enough. Charlie also struggled with the same fears, and his father expressed having learned new ways to convey compassion and love even when Charlie behaved badly, expressing that he was just as worthy of love at his worst moments as he was at his best.

Another parent, Mrs Anderson, also talked about finding more acceptance and compassion towards her daughter, Jessica. She explained that moods steered Jessica, and that even in her own words, she could be difficult when she was down. After Tweens, Mrs Anderson learned how to pause and take a breath, thus avoiding getting distressed and frustrated at her daughter. She expressed an increased understanding of her child’s emotions and their legitimacy. Some participants pointed out how meaningful mindfulness exercises were for increasing self-compassion.

3.3 Mindsight

A newfound sense of increased awareness was brought up in some way in all but one of the interviews, making it one of the most prevalent themes in terms of what meaning the participants ascribed to Tweens. The kind of awareness that the participants described coincides with the term and concept of mindsight. Mindsight is the ability to see both one’s own mind and the minds of others, in order to understand or intelligently speculate on what others might be thinking or feeling. It also encompasses the use of this information to shape one’s own mind by choosing different courses of action (Siegel, 2010). The participants described this as being able to mentally pause, become aware of the present moment and break their typical patterns of behaviour by choosing how to act. They also described a general shift, such as gaining new insight into and knowledge about themselves and others. Figure 3 presents the subcategories of mindsight.

3.3.1 Awareness of self and Others

Many participants mentioned an increased awareness of the moment as well as of qualities in themselves and others, thanks to many different topics handled in Tweens. They especially mentioned the topics of resilience, mindset and positive interaction in this regard, but also well-being in general. Something many of the statements had in common was how the use of the new vocabulary helped both parents and adolescents become more aware.

Mr Evans, Mrs Brown and Michaela pointed out that they were more aware of their own thought patterns and believed that they could affect their thoughts to some extent. Mr Williams and his son Charlie commented that they were more mindful when communicating with others and realised how their own words could affect others. They also saw that no personality traits were inherently good or bad, but that you needed awareness of how to apply them to develop good relationships with others. This increased awareness of their personality traits could also be ascribed to the strength-based exercises. From this, participants learned where their resources for resilience and areas for growth were. Finally, some parents mentioned an increased awareness of their parenting behaviours. These behaviours could be, for example, not taking out their own frustration on their children, being more hopeful and optimistic in their parenting roles, spending more quality time with their children, and listening more to their children’s wishes and needs.

3.3.2 Pausing and self-observation

About half of the parents talked about pausing for reflection and self-observation: some of them focused on mindfulness exercises, while others focused more on pausing in heated moments to prevent taking out their frustration on their children. Mr Williams reflected on how it was easier to have negative interactions with others when you are stressed out, and that in those moments, it was crucial to have increased awareness in order to have positive interactions.

About a third of the adolescents spontaneously brought this up as something they had learned and were using to their benefit. For example, Charlie stated that he stopped to think more often after Tweens. Timmy felt that he could benefit from learning about resilience, as it helped him understand what was going on in his head. He continued that this, in turn, made it easier for him to calm himself down. According to Timmy, this was the reason he had participated in Tweens in the first place.

3.3.3 Choosing Action

Several participants expressed that increased mindsight leads to a series of other possibilities. Their newfound awareness enabled them to choose what happened next in a more conscious manner, such as in the case of Isa. He described how he had become less reactive and how this had prevented a negative situation from growing bigger than it had to. What he described in the following quote was the opportunity of choice, something that several participants experienced as a benefit of increased awareness:

I’ve noticed that sometimes when I’ve become sad or angry but not acted on it, nothing big has happened. So I’ve, yeah like, kept a low profile, or something. (…) This feels good. Or if something happens, like, I don’t make a big deal out of it, but I still get sad of course.

Sophie also described experiencing more self-awareness, mainly of her emotions and the bodily activation that follows. She explained how with practice she had learned to act against her feelings of fear and nervousness and instead expose herself to distressing events when it felt important. It seems that in addition to becoming more self-aware, she had also developed a more dynamic mindset and become more self-assured and skilful at handling difficult situations.

3.3.4 Breaking Patterns

Mr Evans talked about how the increased awareness enabled him to observe his own emotional patterns and break them. He described having previously been in a loop of recognising similarities between current situations and past challenging events, and automatically expecting the same outcome. With his new awareness of resilience and how thought spirals can be created, he was able to recognise this in himself and start breaking this pattern. He expressed how positive thinking would not hurt him, but he also highlighted that Tweens had helped him face the worst-case scenarios and accept them as possible outcomes.

A few other parents also pointed out the connection between becoming more aware and being able to break negative thought spirals. Mrs Brown strongly expressed how revolutionary breathing exercises had been for her, how they made it possible for her to calm down and make conscious choices about how to continue in any situation. Mr Williams also touched on the subject, by describing his realisation of wanting to set a good example for his child on how to handle emotions, and how he can now do so by pausing and not letting his negative emotions steer the situation.

4 Conclusion

The aim of this pilot study was to examine the mechanisms behind relational and individual growth, through looking at if and how the Tweens intervention enabled meaningful change. A qualitative approach with intensive interviewing and in-depth analysis using a CGT method led to three main categories of why and how Tweens was found to be meaningful for the majority of the participants. These findings can add depth to existing promising quantitative data on PPI’s effectiveness in increasing subjective well-being and decreasing symptoms of depression by uncovering some of the mechanisms behind the changes.

The main categories that participants found meaningful in Tweens were a sense of belonging and togetherness, the tools they were taught, and a sense of increased awareness or mindsight. The group format enabled peer support, which led to the participants feeling less lonely. Regarding what tools the participants felt were the most useful were topics and exercises regarding strengths, positive emotions, gratitude, and positive communication. One theme that did not feel as useful especially for some of the adolescents was resilience, since the exercises were more challenging. Tweens also led to more positive communication within the families and better recognition of both one’s own and others’ behaviours and thought patterns. Many described having learned to pause and make more conscious choices instead of being reactive. This ability to pause and react consciously, in addition to experiencing an increased awareness of oneself and others can be summarised as having increased mindsight. However, not all participants found all these categories meaningful, and some adolescents had difficulty finding any meaning at all in Tweens. Possible reasons for this are discussed below.

4.1 Relational Growth Through Upward Spirals

Promoting relational growth was one of the main aims of Tweens. One way to approach this aim is to help families break negative thought or behavioural spirals. In order to break negative spirals, the first step is to be aware of and recognise when reactions are negative. In other words, one needs to have mindsight. Many participants in the Tweens study described having learned to be more mindful and aware of their negative behaviour. Some even described being able to turn negative interactions around into an upward spiral, which is arguably the most important result of this pilot study. The subcategories of mindsight found in this study could be linked together in a cyclical process that describes what happens when we break negative spirals and instead engage in upward spiralling behaviour.

Figure 4 depicts a self-sustaining loop, in which a positive change in any of the boxes leads to further progress in the other boxes. In the child group, Isak was a good example of creating new upward spirals. He claimed that after becoming more aware of his behavioural patterns through Tweens, he had learned to mentally pause when he got sad or angry. When he paused, he could choose to act in a different way than he usually would have, and thus prevent his negative emotions growing out of proportion. When he chose to act differently and got a different result, he also learned something about his own ability to affect any situation. In this way, his newfound awareness of himself and others made it possible to act differently and break a previously negative behaviour pattern.

According to the broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2001), upward spirals form in the interplay between social resources and positive emotions. In accordance with this, we can assume that much of what enabled Isak’s upward spiral was the support he gained from both his father and the Tweens group, and the positive emotions that he reported gaining. He talked about how he now looks forward to more, similar challenging situations, so that he can challenge himself again. These findings show that these factors of mindsight might be the underlying building blocks that make up upward spirals.

Some of the parents also experienced new upward spirals. Many ascribed this to peer support, from which they gained a new social resource, which in turn created positive emotions from feeling heard, accepted and not alone. Several parents pointed out they had reduced their nagging or had been able to pause before becoming frustrated with their children. This indicates that parents could at least better prevent negative spirals from escalating. Becoming more aware of their behaviour patterns was one of the mechanisms behind this change, which was then enhanced in their day-to-day life when they were able to be mindful in the moment and pause.

Increased positive communication within families is another example of upward spiralling. Since both the parents and the children learned the same concepts and gained a shared language to express their mental states, many families were able to create upward spirals. They now talked more often about how they felt and thus experienced more emotional support. Some families felt they managed to make a habit out of expressing appreciation of one another, whereas other families reflected more on how they could sow seeds for more positive emotions to feel good together as a family.

4.2 Factors Negatively Affecting Perceived Meaningfulness

Some adolescents had difficulty seeing any meaningfulness in Tweens. They either saw only a marginal usefulness, were unsure of any actual long-term effects, or denied any benefits. This difficulty in seeing meaning correlated with the symptomatology of these adolescents, so that those suffering from more depressive symptoms found less meaning in the intervention. One way of understanding this is through the underlying mechanisms of depression. As one of the major symptoms of depression is a diminished sense of interest or pleasure, and another is a sense of worthlessness (World Health Organization, 2016), it might be that their inability to find meaningfulness in Tweens was a consequence of their depression. This prompts the question of whether the intervention may still have been helpful for them even if they were not able to see or express this, or whether this type of intervention is unable to provide the help these adolescents need. Two of the most depressed adolescents and their parents reflected that the most important changes should happen at school, where the main problem lay.

Fred ascribed some meaningfulness to Tweens, but mostly as a positive alternative experience that helped take his mind off school for a brief moment. Tweens being a different, better social experience than school is important, as it gives adolescents hope that they can find other social contexts and experiences. But despite having a better time at Tweens than at school, they did not feel that Tweens was able to meet all their needs, because things would not change at school. It is important to note that PPIs only can do so much if problematic contexts are not tended to and resolved, as was the case in the study by Teodorczuk et al. (2019) on children living in youth care centres. It might be difficult to see any meaningfulness or improvement in your well-being if you do not feel that it is within your power to change the situation, despite having learned constructive tools for communication and problem-solving. In the case of children and adolescents, the adults around them need to take responsibility for preventing and intervening in bullying or loneliness, for example.

A couple of the adolescents who perceived limited meaningfulness in Tweens suggested improvements. Among the adolescents who participated in the spring intervention, some complained that group cohesiveness was weak, and that there was little spontaneous sharing among the adolescents. Timmy said that they mostly just answered the leaders’ questions and did not really bond with each other, and Benny felt that it was boring and the atmosphere too heavy. It seems that the leadership in the spring group did not fully succeed with the goal of focusing on strengths instead of having a problem-focused mindset, or the goal of eliciting positive emotions. Furthermore, the age span in the spring group was greater than that in the autumn group, which could have contributed to the adolescents not bonding with each other as well as the adolescents in the autumn group. It seems that continuity and a feeling of safety within the group were crucial for the adolescents in the meaning-making process. This is important feedback for future development of PPIs for adolescents.

In conclusion, not all adolescents felt that Tweens had a meaningful effect on them and their well-being. In other words, the Tweens curriculum might not be effective to all participants, and factors contributing to this could be e.g., severity of symptomatology and a weak group cohesion. It is important to further investigate who benefits of the curriculum and who doesn’t.

4.3 Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The aim of this pilot study was to examine the perceived meaningfulness of Tweens from a participant standpoint. One goal was to let the participants’ own voices be heard, for which an inductive approach with no preformulated hypotheses was optimal. To support this inductive aim, the interviews were conducted as intensive interviews with a specific purpose of determining what, if any, meaning the participants ascribed to Tweens and what the possible meaning-making process looked like. Other than this, the interviews were guided by the participants themselves. To further inductiveness, the literature review was delayed until the end of the research process, as is the custom in GT. The strength of this approach is that it minimises the risk that the researchers see what they expect to see and deductively apply the expected constructs and categories to the participants’ experiences.

One of the goals of using CGT is to keep gathering more data until new data no longer further development in the analyses, i.e., saturation is reached. This was not possible in the current study, as the sample was limited to a pilot study consisting of two small groups of people. While saturation could not be reached, we are cautiously optimistic about the reliability because even without more participants, the data converged toward the main categories that were presented in the analysis section. Furthermore, although the categories were the same, the participants had differing opinions about them. Still, we could have done more, specifically by collecting more interview data from the same participants as the categories started unfolding, in order to explain the relationships between the categories and obtain a more in-depth understanding of them. Moreover, even though it in practice was impossible to include more participants in the pilot study, it is crucial to hear more voices on the subject before making more general conclusions on the meaning-making process and whether Tweens is an effective curriculum for decreasing internalising symptoms and increasing well-being. Another way of increasing the possibility of drawing more general conclusions from the study would have been to choose participants with more similar symptomatology to one another, e.g., only youth experiencing mild symptoms of depression.

We also examined the fit, relevance, modifiability, and workability of the study, which are the GT criteria originally set by Glaser and Strauss (1967). Since the whole analysis is built on constant comparisons and finding the right wording to express the concepts, we argue that the concepts fit and express the data well, this being a strength of the study. Regarding relevance, the study population was the Swedish-speaking population of Finland, and thus the study was relevant to this specific community. Because of the small, culturally homogeneous sample, generalising the results on a larger scale should be done with caution. This study shows modifiability, meaning that the theory is flexible enough to be modified when new data are collected, because of the flexible approach the researchers used when analysing the data. The categories were modified about three to four times as the understanding developed during the analysis process, by rethinking and evaluating how the data could best be understood and presented. Last, workability is whether the theory works to identify the main processes and the variation within these, and whether the categories are the smallest common denominators with which to describe the process. This was the aim of the researchers at all stages, but the degree to which it was successfully achieved is difficult to determine. One way to evaluate this would have been to have other researchers categorise the codes, to see how strongly the same processes would have been observed. However, this was not done in this study, and can be considered a weakness.

Finally, it is important to note that our preconceptions as researchers may have influenced the study. Before the intervention, we examined ourselves for preconceptions and biases, to minimise the risk of them affecting the study. Furthermore, as we were involved in both the interventions and the interviewing process, it is possible that the participants were affected by our familiarity, and did not truthfully express their experiences and thoughts on Tweens. We also noticed some adolescents were less talkative during the interviews, which made us ask more leading questions, which could also have affected the answers. As we were looking for perceived meaning, we often phrased follow-up questions positively, first asking about what they thought was good before asking about what they thought was not.

4.4 Implications and Suggestions for Further Research

This was a pilot study that showed varied but mainly promising results about how meaningful the Tweens intervention was from a participant viewpoint. The purpose of investigating the effectiveness of Tweens was to see whether it formed a suitable treatment for adolescents with mild to moderate symptoms of internalising symptomatology. While not all participants found Tweens meaningful, most of them did find meaning in the form of belonging, new tools and/or increased mindsight. We propose that Tweens could be applied by psychologists working in family counselling or school psychologists, who could offer the interventions as a form of student mental health care. However, more data needs to be collected to confirm and add to the results of this study. Some improvements should be made to the intervention based on the results of the current study, such as a smaller age span for the adolescent participants, since the different maturity levels were an issue for some participants. The results also show that not all topics need be included in both the child and parent groups, as topics regarding conflict-solving and resilience were meaningful for adults but too difficult for the adolescents to grasp. Instead, more emphasis could be placed on having fun and strengthening group cohesion with the adolescents, as the feeling of belonging and togetherness is one of the most meaningful factors and something some of the adolescents wanted more of. Furthermore, further research on the connection between the mindsight cycle and the upward spirals of the broaden-and-build theory would be useful. For instance, it could be investigated using network analyses, by linking awareness, being able to pause, choosing action, and breaking behavioural patterns with generating positive emotions, and being a social resource for others.

Data Availability

From the research group on request.

Code Availability

From the research group on request.

References

Adler, A. (2017). Positive education: Education for academic success and for a fulfilling life. Psychologist Papers, 38(1), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.23923/pap.psicol2017.2821

Allen, B., & Vacca, J. S. (2010). Frequent moving has a negative affect on the school achievement of foster children makes the case for reform. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(6), 829–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.02.001

Beck, J., Beck, A., & Jolly, J. (2013). Beck Ungdomsskalor. Manual Svensk version. Pearson.

Benn, R., Akiva, T., Arel, S., & Roeser, R. W. (2012). Mindfulness training effects for parents and educators of children with special needs. Developmental Psychology, 48(5), 1476–1487. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027537

Boiler, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G., Riper, H., Smit, F., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2013). Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Bmc Public Health, 13(1), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-119

Boniwell, I., Osin, E. N., & Martinez, C. (2015). Teaching happiness at school: Non-randomized controlled mixed methods feasibility study in the effectiveness of personal well-being lessons. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(1), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1025422

Boniwell, I., & Ryan, L. (2012). Personal well-being lessons for secondary schools: Positive psychology in action for 11 to 14 year olds. Open University Press.

Brauer, K., & Proyer, R. T. (2023). Introduction to the special issue “Well-being in Romantic Relationships”. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08956-5_188-1

Cavazos Vela, J., Fisk, J. & Ikonomopoulos, J. (2019). Exploring Latina clinical mental health counseling students’ perceptions of teaching pracices. Teaching and Supervision in Counseling, 1(1), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.7290/tsc010102

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. SAGE publications Ltd.

Charmaz, K. (2015). Grounded theory. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to Research Methods. SAGE publications Ltd.

Conoley, C. W., Plumb, W., Hawley, E., Spaventa-Vancil, K. J., K. Z., & Hernández, R. J. (2015). Integrating positive psychology into family therapy: Positive family therapy. The Counselling Psychologist, 43(5), 703–733. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000015575392

Donaldson, S. I., Dollwet, M., & Rao, M. A. (2014). Happiness, excellence, and optimal human functioning revisited: Examining the peer-reviewed literature linked to positive psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(3), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.943801

Doty, J. L., Davis, L., & Arditti, J. A. (2017). Cascading resilience: Leverage points in promoting parent and child well-being. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9, 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12175

Dweck, C. (2006). The new psychology of success. New York: Random House.

Fagerlund, Å., Laakso, M., Pesonen, A. K., & Eriksson, J. (2021). Flourishing Students: Increasing Student Well-Being Though a Positive Psychology Intervention Program. (Under preparation).

Ferraioli, S. J., & Harris, S. L. (2013). Comparative effects of mindfulness and skills-based parenting training programs for parents of children with autism: Feasibility and preliminary outcome data. Mindfulness, 4(2), 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0099-0

Fox Eades, J. (2008). Celebrating strengths. Building strengths-based schools. CAPP Press.

Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 300.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Fredrickson, B. L. (2013a). Positive emotions broaden and build. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 1–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-407236-7.00001-2

Fredrickson, B. L. (2013b). Updated thinking on positivity ratios. American Psychologist, 68(9), 814–822. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033584

Ghielen, S. T. S., van Woerkom, M., & Christina Meyers, M. (2018). Promoting positive outcomes through strengths interventions: A literature review. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(6), 573–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1365164

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. (1967). The Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine de Gruyter.

Ho, H. C. Y., Mui, M., Wan, A., Ng, Y., Stewart, S. S., & Yew, C. (2016b). Happy family kitchen II: A cluster randomized controlled trial of a community-based positive psychology family intervention for subjective happiness and health-related quality of life in Hong Kong. Trials, 17(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1508-9

Ho, H. C. Y., Wan, A., Ng, Y., Yew, C., Mui, M., Stewart, S. M., Lam, H., T., & Chan, S. S. (2016a). Happy family kitchen: A community-based research for enhancing family communication and well-being in Hong Kong. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(6), 752–762. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000233

Hutchinson, J., & Pretelt, V. (2015). Building resources and resilience: Why we should think about positive emotions when working with children, their families and their schools. Counselling Psychology Review, 25(1), 20–27.

Hwang, Y. S., Kearney, P., Klieve, H., Lang, W., & Roberts, J. (2015). Cultivating mind: Mindfulness interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder and problem behaviours, and their mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(10), 3093–3106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0114-x

Jabbari, M., Shahidi, S., & Mootabi, F. (2015). Effectiveness of group intervention based on positive psychology in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety and increasing life satisfaction in adolescent girls. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 20(4).

Jeste, D. V., Palmer, B. W., Rettew, D. C., & Boardman, S. (2015). Positive psychiatry: Its time has come. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(6), 675–683. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14nr09500

Kichler, J. C., & Kaugars, A. S. (2015). Topical review: Applying positive development principles to group interventions for the promotion of family resilience in pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40(9), 978–980. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsu115

Kwok, S. Y. C. L., Gu, M., Tong, K., & Kit, K. (2016). Positive psychology intervention to alleviate child depression and increase life satisfaction: A randomized clinical trial. Research on Social Work Practice, 26(4), 350–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731516629799

Laakso, M., Fagerlund, Å., Pesonen, A. K., et al. (2020). Flourishing students: The efficacy of an extensive positive education program on adolescents’ positive and negative affect. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-020-00048-2

Lopez, S. J. (2014). Making hope happen: Create the future you want for yourself and others. Atria Books.

Marques, S. C., Pais-Ribeiro, J. L., & Lopez, S. J. (2011). The role of positive psychology constructs in predicting mental health and academic achievement in children and adolescents: A two-year longitudinal study. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 1049–1062. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9244-4

Meija, A., Calam, R., & Sanders, M. R. (2012). A review of parenting programs in developing countries: Opportunities and challenges for preventing emotional and behavioral difficulties in children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15(2), 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-012-0116-9

Niemiec, R. (2014). Mindfulness and character strengths. Hogrefe Publishing.

O’Connor, M., & Cameron, G. (2017). The geelong grammar positive psychology experience. In E. Frydenberg, A. Martin, & R. Collie (Eds.), Social and Emotional Learning in Australia and the Asia-Pacific. Springer.

Pentti, S., Fagerlund, Å., & Nyström, P. (2019). Flourishing families: Effects of a postive psychology intervention on parental Flow, Engagement, meaning and hope. International Journal of Wellbeing, 9(04), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v9i4.1003

Peterson, C. (2008). What is positive psychology, and what is it not? Psychology Today Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-good-life/200805/what-is-positive-psychology-and-what-is-it-not

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues. A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press

Quinlan, D., Swain, N., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2012). Character strengths interventions: Building in what we know for improved outcomes. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(6), 1145–1163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9311-5

Raknes, S. (2009). ) psychologisk forstehjelp [Psychological First Aid]. Gyldendal Akademisk.

Rath, T., & Clifton, D. O. (2009). How full is your bucket? Gallup Press. Educator’s ed.

Reivich, K., & Shatté, A. (2002). The resilience factor. Three Rivers Press.

Ruini, C., Belaise, C., Brombin, C., Caffo, E., & Fava, G. A. (2006). Well-being therapy in school settings: A pilot study. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 75, 331–336. https://doi.org/10.1159/00009-5438

Sanders, M. R., Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Day, J. J. (2014). The triple P-positive parenting program: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(4), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.04.003

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish. A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education, 35, 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980902934563

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.60.5.410

Siegel, D. (2010). Mindsight: The new science of personal transformation. Bantam Books.

Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session, 65(5), 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclip.20593

Stallard, P. (2002). Think good, feel good: A cognitive behavioural therapy workbook for children and young people. Wiley.

Stallard, P. (2005). A clinician’s guide to think good-feel good: Using CBT with children and young people. Wiley.

Suldo, S. M., Savage, J. A., & Mercer, S. H. (2014). Increasing middle school students’ life satisfaction: Efficacy of a positive psychology group intervention. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 19–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9414-2

Teodorczuk, K., Guse, T., & Plessis, A., G (2019). The effect of positive psychology interventions on hope and well-being of adolescents living in a child and youth care centre. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 47(2), 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2018.1504880

Tomyn, A. J., Weinberg, M. K., & Cummins, R. A. (2015). Intervention efficacy among ‘at risk’ adolescents: A test of subjective wellbeing homeostasis theory. Social Indicators Research, 120, 883–895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0619-5

Turner, E. H., & Mueller, C. W. (2021). Greater focus on strengths is associated with successful discharge in youth public mental health treatment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health Services Research, 78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-021-01121-x

Waters, L. (2020). Using positive psychology interventions to strengthen family happiness: A family systems approach. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(5), 645–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1789704

Weems, C. F. (2009). Developmental psychopathology, positive psychology and knowledge development in child and youth care: Editorial hopes and aspirations for the forum. Child & Youth Care Forum, 38(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-009-9064-z

World Health Organization (2016). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (10th ed.). https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en

Funding

The Folkhälsan Research Foundation.

Open access funding provided by Abo Akademi University (ABO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jennifer Söderlund wrote the original manuscript and analysed the data. Julia Simonsen translated the manuscript to English and finalised the work. Kristina Ström supervised the work and commented on the manuscript. Åse Fagerlund supervised the work and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the University of Helsinki Ethical Review Board in the Humanities and Social and Behavioral Sciences.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Consent to Participate

Written informed consent from all participants.

Consent for Publication

Written informed consent from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Support structure for the family interviews

General questions

-

1.

What thoughts do you have on Tweens in general?

-

2.

What did you do during Tweens? Tell me since I wasn’t there.

-

3.

Did you learn something that you will include into your life or that had an impact on your way of thinking? What could you tell your former self, that you didn’t know then?

-

4.

What was the best part of Tweens?

-

5.

What is, in your opinion, the biggest change you see in yourself or your family since participating in Tweens? Have you started doing anything differently at home?

-

6.

What meaning did the group have to you? Compared to if you learned about positive psychology by yourself or at school.

-

7.

Which of the homework exercises were the most rewarding to you? Will you continue doing any of them after Tweens?

-

8.

What are your biggest strengths? What benefits could you have from knowing about strengths?

-

9.

How does it feel now that Tweens has ended?

-

10.

Does it feel like you got what you wanted out of Tweens?

Walkthrough of the sessions

-

1.

Summarising the session and asking what they thought of it.

-

2.

Asking whether they have used the methods taught in that session at home.

-

3.

Asking if and how they have benefitted from the used methods.

Themes

-

1.

Positive emotions.

-

a.

What feelings have you felt more since participating in Tweens?

-

b.

What feelings have you felt less since participating in Tweens?

-

c.

What changes has the parent noticed in the child?

-

a.

-

2.

Optimism

-

a.

What thoughts do you have on optimism and hope for the future?

-

b.

Has your way of viewing yourself changed since participating in Tweens? How?

-

c.

What thoughts do you have on the possibility of reaching your future goals?

-

a.

-

3.

Positive relationships

-

a.

Have you noticed any change in your relationship?

-

b.

Has your way of spending time together changed in any way?

-

c.

Have you noticed a change in your other relationships e.g., with friends or siblings?

-

d.

You had a homework exercise where you asked what strengths others see in you. What were your thoughts on it?

-

a.

-

4.

Perseverance and resilience

-

a.

If you were to face a challenge that requires hard work, what thoughts go through your mind before starting the work?

-

b.

If you think back to yourself before Tweens, has your way of thinking changed in any way?

-

c.

Has the parent noticed any changes in the child’s perseverance and resilience when faced with a challenge.

-

a.

-

5.

Engagement

-

a.

Have your thoughts regarding school changed in any way? Has Tweens changed the way you take on school exercises? Has your ability to focus at school changed?

-

b.