Abstract

The persistent problem of low and stagnant labour force participation rate of women in urban India over the past two and a half decades has been well recognised by scholars. The rates stagnated within the low range of 22–23%, during the period extending between 1999–2000 and 2011–2012. The paper attempts to contribute to the current understanding of this puzzling phenomenon through a sequential analysis of long-term trends in female labour force participation rate by disaggregating urban women in terms of their age, marital status, and education levels. The cross-sectional analysis is supplemented by the nonparametric technique of classification and regression tree (CART). Focussing on the sample of non-student urban women, the paper finds that the problem relates primarily to the relatively better educated married women in the age-cohorts of 30–59 years. Moreover, 2011–2012 was marked by a further weakening in the labour market outcomes of these women, both with respect to the lesser educated married women and married men in general.

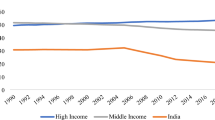

Source: Calculated from unit-level NSSO data for various rounds

Source: Calculated from unit-level NSSO data

Source: Calculated from unit-level NSSO data for various rounds

Source: Calculated from unit-level NSSO data for various rounds

Source: Calculated from unit-level NSSO data

Source: Calculated from unit-level NSSO data

Source: Calculated from unit-level NSSO data

Source: Calculated from unit-level NSSO data

Source: Calculated from unit-level NSSO data

Source: Calculated from unit-level NSSO data

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Labour force participation rate is defined as the percentage of the persons employed (working) or unemployed (seeking or available for work) to the total persons in the working age group. In the adjusted labour force participation rate, the numerator of the ratio remains unchanged. It is from the denominator or the total sample of working age women (15–59 years); the section of women currently attending educational institutions (usual activity status 91) is removed.

0 year equals illiterate to below primary education; 5 years equals primary level; 8 years equal middle level; 10 years equal secondary level; 12 years equal higher secondary; and 15 years equal graduate and above (Ghose, 2004).

Reservation wage is the lowest wage at which an individual is willing to work and it plays an important role in the labour force participation decision of women (Brown et al., 2011).

References

Abraham, V. 2013. Missing labour or consistent “De-Feminisation”? Economic and Political Weekly 48 (31): 99–108.

Afridi, F., T. Dinkelman, and K. Mahajan. 2018. Why are fewer married women joining the work force in rural India? A decomposition analysis over two decades. Journal of Population Economics 31 (3): 783–818.

Andres, L. A., Dasgupta, B., Joseph, G., Abraham, V., and Correia, M. 2017. Precarious drop: reassessing patterns of female labor force participation in India. Technical report, World Bank Group, Washington, D.C

Bhalla, S., & Kaur, R. 2011. Labour force participation of women in India: some facts, some queries.

Brown, S., J. Roberts, and K. Taylor. 2011. The gender reservation wage gap: Evidence from British panel data. Economics Letters 113 (1): 88–91.

Chatterjee, U., Murgai, R., & Rama, M. (2015). Job opportunities along the rural-urban gradation and female labor force participation in india. The World Bank.

Chaudhary, R., & Verick, S. 2014. Female labour force participation in India and beyond (No. 994867893402676). International Labour Organization

Chowdhury, S. 2011. Employment in India: What does the latest data show? Economic and Political Weekly 46 (32): 23–26.

Das, M., and S. Desai. 2003. Why are educated women less likely to be employed in India? Testing competing hypotheses. Washington, DC: Social Protection, World Bank.

Das, M.S., Jain-Chandra, S., Kochhar, M.K., & Kumar, N. 2015. Women workers in India: why so few among so many? (No. 15–55). International Monetary Fund.

Desai, S., & Joshi, O. 2019. The Paradox of Declining Female Work Participation in an Era of Economic Growth. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 1–17

Eapen, M. 2004. Women and work mobility: Some disquieting evidences from the Indian data (No. 358). Centre for Development Studies, Trivendrum, India.

Ferrant, G., Pesando, L. M., & Nowacka, K. 2014. Unpaid Care Work: The missing link in the analysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes. Issues paper

Ghose, A.K. 2004. The employment challenge in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 5106–5116

Ghose, A.K. 2013. The Enigma of Women in The Labour Force. Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 56(4). Ghose, 2013

Ghose, A.K. 2016. India Employment Report 2016. New Delhi: Oxford University Press for The Institute for Human Development.

Himanshu. 2011. Employment trends in India: a re-examination. Economic and Political Weekly, 43–59

Kannan, K.P., & Raveendran, G. 2012. Counting and profiling the missing labour force. Economic and Political Weekly, 77–80

Kapsos, S., Bourmpoula, E., & Silberman, A. 2014. Why is female labour force participation declining so sharply in India? (No. 994949190702676). International Labour Organization.

Klasen, S., & Pieters, J. 2012. Push or Pull? Drivers of Female Labor Force Participation during India's Economic Boom (No. 6395). Institute for the Study of Labor

Klasen, S., & Pieters, J. 2015. What explains the stagnation of female labor force participation in urban India? The World Bank

Lin, S. Y., Wei, J. T., Weng, C. C., & Wu, H. H. 2011. A case study of using classification and regression tree and LRFM model in a pediatric dental clinic. International Proceedings of Economic Development and Research—Innovation, Management and Service, 14, 131–135.

Malinowska, A. 2014. Classification and regression tree theory application for assessment of building damage caused by surface deformation. Natural Hazards 73 (2): 317–334.

Mitra, A., & Verick, S. 2013. Youth employment and unemployment: an Indian perspective. ILO

Naidu, S.C. 2016. Domestic labour and female labour force participation. Economic and Political Weekly L1 (44 & 45): 101–108.

Panda, P.K. 2003. Poverty and young women's employment: linkages in Kerala. Economic and Political Weekly, 4034–4042

Rangarajan, C., Kaul, P.I., & Seema. 2011. Where is the missing labour force?. Economic and Political Weekly, 68–72

Roche, F., V. Pichot, E. Sforza, D. Duverney, F. Costes, M. Garet, and J.C. Barthélémy. 2003. Predicting sleep apnoea syndrome from heart period: A time-frequency wavelet analysis. European Respiratory Journal 22 (6): 937–942.

Rustagi, P. (2013). Changing Patterns of Labour Force Participation and Employment of Women in India. Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 56(2)

Sinha, P. (2013). Combating youth unemployment in India. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Department for Global Policy and Development

Sudarshan, R. M., & Bhattacharya, S. 2009. Through the Magnifying Glass: Women's Work and Labour force participation in urban Delhi. Economic and Political Weekly, 59–66.

Funding

The study is not based on funding by any Institution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

See Tables

14 and

15.

Appendix B

See Figs.

11,

12,

13.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tayal, D., Paul, S. Labour Force Participation Rate of Women in Urban India: An Age-Cohort-Wise Analysis. Ind. J. Labour Econ. 64, 565–593 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-021-00336-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-021-00336-8

Keywords

- Female labour force participation

- Employment rate

- Age-cohort

- Married women

- Domestic duties

- Graduate women