Abstract

An estimated 3.5 million interstate migrant workers have become an indispensable part of Kerala’s economy. The state also offers the highest wages for migrant workers for jobs in the unorganised sector in the entire Indian subcontinent. Further, the state has evolved several measures for the inclusion of the workers and was able to effectively respond to their distress during the national lockdown. This paper examines labour migration to Kerala, key measures by the government to promote the social security of the workers and the state’s response to the distress of migrant workers during lockdown, by synthesising the available secondary evidence. The welfare measures as well as interventions initiated by the state are exemplary and promising given the intent and provisions. However, some of them do not appear to have consideration of the grassroots requirements and implementation mechanisms to enhance access. As a result, the policy intent and substantial investments have not yielded the expected results. The state’s effective response to the distress of workers during the lockdown emanates from its overall disaster preparedness and resilience achieved from confronting with two consecutive state-wide natural disasters and a public health emergency in the immediate past. While the government has played a strategic role through policy imperative and ensuring a synergistic response, the data presented by the state indicate a much larger but invisible role played by the employers and civil society in providing food and shelter to workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Ahead in demographic transition among Indian states, Kerala has evolved as one of the most attractive destinations for migrant workers from the rest of India. The state offers the best wage rates for workers in the unorganised sector in the country, manifold compared to most other states (Labour Bureau 2020). The state, which registered replacement level of fertility three decades of ago, has two districts already registering negative population growth (GOK 2019a). Interstate migrant workers have become an indispensable part of the state’s economy. Almost all economic sectors that require arduous physical labour are dependent on migrant workers. This also includes sectors such as marine fishing that requires highly skilled labour. Estimated to be about 3.5 million in 2018, migrant workers hail from all over India (GOK et al. 2018). While the rest of the states struggled to address the distress of migrant workers during the national lockdown to arrest the COVID-19 pandemic, Kerala was able to ensure food and shelter to workers through a decentralised response. The state, which is still known as a remittance economy where migration from Kerala directly or indirectly impacts every household in the state, is also known for measures taken for the welfare of interstate migrant workers it receives (Planning Commission 2008). This paper examines labour migration to Kerala, key measures by the Government of Kerala (GOK) to promote the social security of the migrant workers and inclusiveness of the response of the state to the distress of migrant workers during lockdown, by synthesising the available secondary evidence.

2 Migration from Neighbouring States

Since its formation in 1956, the state has attracted migrant labourers from the neighbouring states, particularly from Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. During the period from 1961 to 1991, workers from Tamil Nadu and Karnataka complemented the native workers in filling up the requirement of the blue collar labour force (Kumar 2016). There were specific sectors where migrant labourers were largely absorbed including the plantations, the brick kilns and work requiring digging up. In Wayanad, Kannur and Kasaragod districts, workers from Karnataka catered to the labour requirement, while in all the districts, workers from Tamil Nadu were available. Migrants from Tamil Nadu have played a key role in the construction sector in Kerala from the mid-1970s. Limited availability of employment in both agricultural and industrial sectors in Tamil Nadu, coupled with the spurt of construction activity that arose due to the high inflow of remittances from Keralites working in the Middle East, had triggered such migration (Anand 1986). The significant difference in wages and the sustained demand in the construction sector resulted in heavy migration from Tamil Nadu. By 1990s, Kochi, the construction hub and commercial capital of Kerala, witnessed heavy migration of labourers from Tamil Nadu. A settlement of migrant workers from Tamil Nadu evolved at Vathuruthy in Kochi (Peter and Narendran 2017). In 2007, workers from 13 districts in Tamil Nadu, predominantly from Dindigul, Tiruchirappalli, Theni and Madurai, worked in Kochi city (Surabhi and Kumar 2007). Three-fifths of the migrants in Thiruvananthapuram district in 2007 were from Tamil Nadu (Rajan and Zachariah 2007).

3 Migration from the Rest of India

Labour migration from beyond Southern India started significantly with the arrival of migrants from Odisha to work in the Timber Industry in Ernakulam district. Migrants from Odisha, who arrived first, lived in the mill premises and worked hard even at odd hours and were content with whatever limited work was available and the free accommodation provided. Bhais, as the migrant workers from outside South India are popularly called, received higher wages than what they could earn elsewhere in India and enjoyed the work and the peaceful life in Kerala. The timber entrepreneurs in Perumbavoor preferred migrants from eastern India over Tamilians because they came single, were less expensive, more subservient, hardworking and available, relatively, throughout the year (Peter and Gupta 2012). The emergence of Kanjikode in Palakkad during the nineties as a hub of iron and steel industry led to sourcing of workers from Bihar. The work required skill and constant exposure to intense heat with no local takers (Peter and Narendran 2017). The Supreme Court of India banned forest-based plywood industries in Assam in 1996. This resulted in the collapse of plywood industry in Assam which had the monopoly in this sector in India, and the rise of Kerala, which depended on rubber wood for plywood production, as a major hub of plywood production in India. Migration from Odisha increased significantly, and there emerged a new stream of workers from Assam, particularly workers skilled in plywood production. Following their footsteps, unskilled workers from West Bengal arrived (Peter and Gupta 2012). Gradually, migrants from several other states arrived taking up any kind of unskilled work.

While most of the labour migration was driven by the social network of the workers, multinational companies too mobilised workers from states such as Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and West Bengal using intermediaries, to work in their projects in Kerala. The GOK also noted the increase in the number of workers from states such as West Bengal, Bihar, Odisha, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand (GOK 2009). A study, covering four cities and six sectors of employment in Kerala, found that West Bengal and Tamil Nadu were the major source states of migrant workers in Kerala in 2012 (Moses and Rajan 2012). Nearly 8500 children from migrant families were enrolled in government-funded schools in Kerala during the academic year 2019–2020 (Kuttikrishnan 2019).

4 Estimate of Migrant Workers

Robust estimates of migrant workers in Kerala are currently not available. A study commissioned by the Department of Labour and Skills (DOLS), GOK, estimated that there were over 2.5 million interstate migrant workers in the state in 2013. The net annual addition per year according to the study conducted by the Gulati Institute of Finance and Taxation (GIFT) was 1,82,000 migrants (Narayana et al. 2013). Based on this, it was projected that the state has nearly 3.5 million interstate migrant workers in 2018 (GOK et al. 2018). However, the survey based on long-distance train entering Kerala did not consider those from the neighbouring states such as Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, who come using other means of transport. That way, the GIFT estimate could even be underestimated. Irrespective of the debate on the estimated number of migrant workers in the state, it is evident that such workers are present even in the remotest corners of the state. A Hindi service was available on Sundays in 2016 for the workers from Jharkhand at the church in Anakkampoyil, one of the remote corners of Kozhikode district (Peter and Narendran 2017).

5 Migration Corridors to Kerala

The increasing demand for workers to take up work that required heavy physical labour, coupled with the high wage rates compared to the rest of India, regular availability of employment and minimal avenues for employment in states which are experiencing a demographic dividend coincided by lack of employment opportunities, has resulted in the evolution of some of the longest labour migration corridors in India connecting Kerala with Assam, West Bengal, Odisha, Jharkhand, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh in addition to Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. A study by Centre for Migration and Inclusive Development (CMID) documented migrants from 194 districts from across 25 Indian states/Union Territories working in Kerala during 2016–2017. More than four-fifths of these districts belonged to eight Indian states: Tamil Nadu and Karnataka in the south, Uttar Pradesh in the north, Jharkhand, Odisha, Bihar and West Bengal in the east and Assam in the northeast India. Nearly 60 per cent of the source districts belonged to the east and northeast India (Peter and Narendran 2017). District-level corridors have also emerged indicating the strong influence of social network in migration. Table 1 provides a list of corridors evolved between eastern Indian states and Kerala. The growing informalisation of work has resulted in almost all industries including public sector entities engaging migrant workers directly or indirectly.

The profile of workers varied by native place of the worker, location of employment as well as the sector in which he/she is engaged. The preferences of industries coupled with gender, social network as well as the skillset of the migrant by and large decided the profile of the migrants in a particular industry. Traditional fishers from Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha and West Bengal worked in the marine fishing sector, expert artisans from Saharanpur of Uttar Pradesh were engaged in the furniture sector, young girls from eastern and north eastern states were mostly employed in the fish processing as well as garment and apparel industries, young Adivasi couples from Jharkhand were preferred by the tea plantations, men from north Karnataka and Assam worked in the laterite mines, and the hospitality industry preferred workers from Northeast India, Darjeeling and Nepal (Peter and Narendran 2017).

Akin to the rest of India, the temporary migrants in Kerala also belonged to socially and educationally disadvantaged poor agrarian communities, whose livelihood opportunities in their native places have been severely constrained by a multitude of factors including climate change, disasters like drought and floods, conflicts and oppression. Among the 194 districts in India from where migrant workers have flocked to Kerala during 2016–2017, 33 were among the top 100 districts in India with the largest number of Scheduled Tribe population as per the 2011 Census. Also, among the top five districts in India with the largest Scheduled Caste population, four have evolved as district-level corridors of labour migration to Kerala (Peter and Narendran 2017). Over half of the interstate migrant workers in Ernakulam districts belonged to religious minority communities (CMID 2020). Typical of long-distance migration, single men dominated the migration stream from eastern India, while single men, women, couples and families came from neighbouring states.

6 Measures by the State for the Welfare of Workers

Kerala is the first Indian state to enact a social security scheme for migrant workers (Srivastava 2020). The state’s concern in the welfare of the interstate migrant workers is reflected in the way it constituted a Working Group on Labour Migration under the 13th Five-Year Plan deliberations (2017–2022). The state also organised several national and state-level deliberations on the challenges faced by the workers in the state. The Fourth Administrative Reforms Commission (ARC) evaluated the implementation of the welfare schemes for migrant workers as a priority. There are several measures taken by various departments for the inclusion of migrant workers. The Department of Education since 2008 has been engaged in promotion of inclusive education for children of migrant workers. Educational volunteers who speak the mother tongues of the migrant children have been appointed by Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan in select schools in areas with high concentration of migrant children. The State Literacy Mission, from 2017 onwards, implements a programme to teach the workers Hindi and Malayalam. Kudumbashree, the state’s initiative for empowerment of women and poverty eradication, has initiated efforts to bring migrant women also into its fold. In addition to the HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) prevention interventions, the Department of Health and Family Welfare, through National Health Mission (NHM), has introduced Link Workers in 2020 to enhance access to healthcare for migrant families. Resourceful migrant workers were recruited and trained to provide health information and connect the migrants to services in their own language coordinating with the other frontline workers of the department. The Department of social justice has started setting up mobile creches to take care of kids of migrant workers. From January 2020, the Civil Supplies Department has activated interstate portability benefits to workers from select states although it currently excludes West Bengal, Assam, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar from where over 80 per cent of the workers come (GOK 2020a).

The DOLS, which offers a host of welfare measures for the migrant workers, directly implements three worker facilitation centres in the state for migrants, one each in the south, central and north regions. In addition to the Interstate Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Services) (ISMW) Act, 1979, the central act that provides for the social security of interstate migrant workers in India, the state, in 2010, launched an Interstate Migrant Workers Welfare Scheme (ISMWWS-2010) which has several provisions for the welfare of the migrant workers. Aawaz Insurance Scheme 2016 and Apna Ghar Housing for migrant workers are the two other major initiatives of DOLS. The salient features of the state schemes are outlined below.

7 Interstate Migrant Workers Welfare Scheme 2010

Under the ISMWWS, a separate fund was created under the Kerala Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Board (KBOCWWB) for the welfare of migrant workers. A worker in the age group 18 to 60 years can enrol under the scheme after completion of one month from his/her arrival in the state, paying a renewable annual membership fee of ₹30. GOK contributes a sum equal to three times of the annual receipts through membership to the fund, and a similar contribution is also earmarked from the KBOCWWB. The scheme mandates every employer in the state who engage interstate migrant workers to ensure that such workers are registered under the scheme. Table 2 summarises the key benefits under the scheme as updated in 2019.

8 Apna Ghar Housing Scheme

The Apna Ghar migrant housing project was launched in 2019 by the DOLS with the intention to provide affordable rental housing to migrant workers in the state. Equipped with dormitory style rooms, cooking and dining facilities, drying areas and toilets, this migrant hostel is available to the migrant workers at a subsidised rent through their employer. A bed can be availed by migrant workers at a rent of ₹1000 per month (Desai 2019). DOLS has constructed one such 620-bed hostel in a Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in Kanjikode, Palakkad, and intends to construct such hostels in districts across the state, to start with Ernakulam and Kozhikode.

9 Aawaz Insurance Scheme

Launched by the DOLS in 2016, Aawaz is an insurance package designed exclusively for migrant workers. A migrant worker can get enrolled for free under Aawaz and avail a health insurance cover of ₹15,000 and an accidental insurance cover of rupees two lakhs (GOK 2020b). Registration is done through the DOLS facilitation centre and also through special outreach campaigns. The registration process is outsourced to a private entity. Fingerprints and iris scans of the workers are taken, and an identity card is issued. Over five lakhs Aawaz cards have been issued to interstate workers during the period 2016 to 2020. The claims are managed by DOLS as an assurance model.

10 A Critical Review of the State of Access to DOLS Schemes

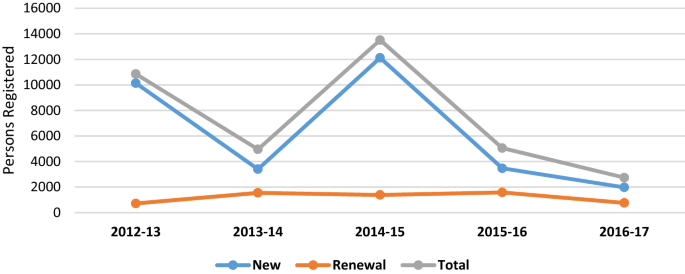

An analysis of the schemes being implemented by DOLS reveals that despite the policy measures, the workers have not been able to benefit substantially from any of these schemes as observed by Srivastava (2020). Since majority of workers who come to Kerala are not recruited by a contractor from their native states, the Interstate Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Services) (ISMW) Act, 1979, does not apply to them in its current form. Most of those who are recruited at the native state and brought by the contractors to Kerala also are not registered as the data for the period 2012–2017 reveal (Table 3). The registrations increased from 6833 during 2012–2013 to 11,011 during 2014–2015 and subsequently declined to almost half of it in 2016–2017 (GOK 2018).

The Administrative Reforms Commission which reviewed the implementation of the Interstate ISMWWS observed that the scheme has become ‘defunct’ with only 2741 registrations during 2016–2017, whereas the state was estimated to have over 2.5 million interstate migrants working in Kerala (GOK 2018). Figure 1 provides the trends in registration under ISMWWS during 2012–2017. During the five-year period from 2012 to 2017, a total of ₹12.3 lakhs was spent as benefits to migrant workers, which was only 14 per cent of the total expenditure during the period and only 1.3 per cent of the total available funds (GOK 2018). The benefits disbursed were mostly related to compensation towards death or repatriation of the body of the workers who had died.

Poor demand creation has been one of the major reasons for the failure of the scheme. A study in Ernakulam district during December 2019–January 2020 revealed that none of the 419 workers interviewed had heard about the scheme (CMID 2020). The scheme was nested under the KBOCWWB without deployment of additional staff. There were other barriers also such as the paper work required including the certification by employer and capping of monthly wage to ₹7500. Besides, the introduction of Aawaz scheme in 2016, which was in fact a duplication of a subset of the benefits under ISMWWS, further weakened the implementation of the scheme. Although as a welfare scheme for migrant workers, Aawaz got popularity in the media, majority of the migrant workers in the state are unaware about its existence (Sreekumar 2019). Introduction of Aawaz appears to be more a surveillance measure collecting the biometric data than with the real intent of providing health and accidental insurance since ISMWWS already provided these services along with a host of other benefits for the workers and their family members. Currently, the services under Aawaz are available only at government health facilities. None of the migrants who had experienced hospitalisation during 2019–2020 reported to have benefited from Aawaz, but had managed it from their own pocket or with the support of their employer (CMID 2020). One of the key reasons for the low awareness and uptake of the schemes is the human resource constraints of DOLS to promote awareness and enrolment. The employers are also hesitant to get all their workers registered fearing that this might result in documentation of the number of persons engaged by establishment attracting legal action to provide them with employee benefits (Sreekumar 2019).

While the housing infrastructure created under the Apna Ghar scheme meets the requirement of single male migrants, instead of addressing the housing needs of the most vulnerable workers such as the footloose workers or migrant families, the scheme subsidises the cost of accommodation of private enterprises and helps them improve their profit margins (Desai 2019). There is only one such facility functioning in the entire state offering a total of only 620 beds in the state. Besides, accommodation arrangements through employer keep the workers confined to the employer. Given the Kerala context, instead of segregating the migrant workers through exclusive housing for migrants, the state should promote mainstream living facilitating the workers’ access to affordable housing leveraging the open market where state plays the role of regulator than being a provider.

11 Collective Bargaining and Employee Welfare

Migrant workers in Kerala have so far not benefited from the immense social capital gained by the trade unions in Kerala. Even in 2020, more than 90 per cent of the workers are not part of any trade union which deprives them of the power of collective bargaining (CMID 2020). Unprotected by labour unions, they are often exploited and subjected to unfair practices at the work place. Wages received by the migrant workers are lesser than the wages received by locals for the same work (Parida et al. 2020). Differential wages and the role of powerful labour unions in perpetuating wage discrimination and labour segmentation have created a deep divide in the work force of Kerala (Prasad-Aleyamma 2017). Just like most informal workers in the rest of the country, most of the migrant workers in Kerala also do not enjoy the employee welfare measures such as employees’ state insurance (ESI), provident fund (PF) or pension. They are engaged directly or through contractors through verbal agreements without being on the rolls, under piece rates or other arrangements and are paid in cash. In several instances, employers have avoided registering workers with DOLS to reduce the liabilities and benefits they are to provide to the workers (Krishnakumar 2019).

12 Othering of Migrant Workers

As a state which substantially benefits from its diaspora, Kerala acknowledges the contribution of migrants and has constituted Loka Kerala Sabha, a platform that provides the diaspora an opportunity to contribute to policy formulation of the state (GOK 2019a). Also, the state has an exclusive department for the welfare of its nearly three million non-Keralites in the name of Department of Non-Keralites Affairs (NORKA) directly under the Chief Minister. However, there is no comparable institutional mechanism at the state level for the welfare of the interstate migrant workers who are larger in number compared to the Kerala diaspora. Also, by referring migrant workers as Athithi Thozhilali (guest worker) in documents, including government orders, the state officially promotes othering, reminding everyone that the workers who are Indian citizens with the fundamental right to work, reside and travel anywhere in the country, ‘do not belong to Kerala’ and are expected to return upon the completion of work. Although the state glorifies this as treating the workers as state’s ‘guests’, this tokenism essentially permeates xenophobia presenting the workers as ‘less privileged ones’ compared to Malayalis. At the same time, the Malayali workers elsewhere are referred to as Pravasi Malayali, which essentially means migrant Malayali and not as ‘guest workers from Kerala’. This othering promoted by the state is so pervasive that it has penetrated deep into psyche of migrant workers, some of whom introduce themselves as ‘I am a Bhai’. Although Bhai and Annan have the literal meaning ‘brother’, in Kerala these have become synonyms to migrant identities from north and south India. Most of the Malayali employers call their workers by these names, and a large share of employers do not even know the real names of their workers.

13 The Impact of COVID Pandemic and the State Response

In the absence of studies, this section of the paper banks on CMID’s grassroots experience in the state including operating a multilingual helpline for distressed migrant workers in the state supplemented by government documents available in the public domain as well as newspaper reports.

The national lockdown on 25 March 2020 to arrest the spread of the COVID-19 infection had a catastrophic impact on the migrant workers in the country. While the country came to a standstill, the stigma and consequent discrimination faced by the migrant workers was visibly prominent. Abandoned by employers, livelihoods lost, evicted from their residences and deprived of social security, hundreds of thousands of migrant workers and their families, including children, were pushed to the streets in India’s urban centres (Caritas India 2020; Jan Sahas 2020; Stranded Workers’ Action Network 2020). In the absence of transport, thousands of migrants were forced to walk towards their homes hundreds of kilometres away. Several of them died on the way unable to cope with the arduous journey and hunger. While the rest of the country witnessed such a plight of migrant workers and the state governments struggled to manage the crisis, the situation in Kerala was substantially better. In this section of the paper, the authors examine the impact of the COVID pandemic on migrant workers in the state and the Kerala’s response to address the challenges they faced.

The first COVID-19 case in India was identified in Kerala on 30 January 2020 (Perappadan 2020). With more cases surfacing during early March in the state, distancing and other measures by the state and people impacted migrants who worked in sectors which involved substantial public interaction. The hotels and restaurants lost business and had to be eventually closed down, resulting in loss of employment of migrants (Narayanan 2020; Smitha 2020). Many employers asked their workers to return home till situation improved (Gram Vikas and CMID 2020). The footloose labourers were another group who were impacted from the initial days onwards as they could not assemble at the junctions seeking work since crowds were discouraged. Besides, the demand for work also declined steeply as the potential employers feared that hiring migrant workers would put them at risk of infection from the workers. Travel also eventually became difficult. These impacted workers from Tamil Nadu and West Bengal particularly who formed the largest proportion of footloose labourers in the state. Beauty parlours, saloons and malls also had fewer visitors impacting the livelihoods of workers. As a result, by the middle of March, the footloose workers and those who worked in the hotel and restaurants began to return to native places (Kuttappan 2020). Many had to hurriedly leave without obtaining the salary they had entrusted with the employers. There were also workers who wished to return but had to stay back as their native families had substantial debts to be repaid or their families solely survived on remittances from Kerala (Gram Vikas and CMID 2020).

With the lockdown on 25 March 2020, everyone except those who worked in essential services lost employment. The announcement of lockdown panicked the workers and their families at the native place. During the initial days, access to food was a challenge, particularly for the footloose labourers in the absence of an employer to take care of their food expenses (Vineeth 2020). The Local Self-Governments (LSGs) delegated the provision of food to employers and those who gave houses/rooms on rent to workers (GOK 2020c). However, given the mobility constraints, large number of workers, the need to feed them thrice a day, this was something the house owners could not afford to or manage. The community kitchens set up by the LSGs initially did not provide free food to migrant workers (GOK 2020d). Four-fifths of calls to CMID’s Bandhu helpline for migrant workers during the period 30 March to 11 April 2020 were seeking help for obtaining food.Footnote 2 Migrants who had brought families to Kerala were affected severely compared to those who were single. While the food-related challenges eventually subsided, there were also workers who had to request their native family to send money to buy provisions/food. At many places the supply was insufficient given the requirement (Koshy 2020a). Although government gave provisions, at several places, the workers struggled to obtain cooking fuel and other ingredients in the absence of money. Very few workers endeavoured to walk to their native places from Kerala although Idukki and Malappuram witnessed workers walking to Tamil Nadu and workers were documented attempting to walk to Jharkhand, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Karnataka from Kannur (Emmanuel 2020; Bhat 2020).

Messages were also in circulation that trains are being organised by government for the return of workers. Amidst such confusions, in Paippad near Kottayam where large number of footloose labourers lived, thousands of workers assembled in the streets seeking support to go home (Nair 2020). Such protests also took place in Koothattukulam in Ernakulam district, Pattambi in Palakkad, Payyannur in Kannur district as well as in Malappuram (Subrahmani 2020; Mathrubhumi 2020; Shaju 2020). In Perumbavoor in Ernakulam district, the footloose labourers protested on the poor quality of food provided to them (Indian Express 2020).

As lockdown got extended, several workers got exhausted and wanted to go home. When Shramik trains were organised for workers to return home, migrants who lived outside major clusters struggled without information and started gathering at places where registrations happened on the previous day. While majority of the workers were from West Bengal, Assam and Tamil Nadu, most trains went to Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Odisha during the initial weeks. Also, the workers were asked to pay for the train fare which initially prevented the travel of those who had financial constraints (Joseph 2020; Koshy 2020b). The families also found it challenging as they had to arrange money for the travel of multiple persons. Later, with the intervention of the Supreme Court, the workers were not charged (Scroll 2020). Rumours that workers will not be able to return for a year if they did not go immediately also panicked the workers. Workers in districts without railway stations such as Idukki found it difficult to access the Shramik trains, and some of them walked towards Ernakulam. This was eventually resolved by registration and organising transport.

In some places, workers were persuaded by local residents to return to native places and there were also sporadic cases of forced retention by employers (Kallungal 2020). Leveraging the opportunity around the ambiguity about the availability of Shramik trains, private bus operators organised trips charging ₹5000 to ₹6000 per person for trip to Odisha and ₹7000 to ₹9000 for travel to West Bengal and Assam (Abraham 2020). Since the Shramik Special trains were discontinued without providing opportunities for all workers who wanted to return home, a lot of workers had to borrow money to travel by air (Times of India 2020). Even in September 2020, migrant workers continued to be stranded in Kerala and were unable to go home since economical modes of transport were not available. Even with the unlock phase in progress, most of the workers who wished to return to Kerala have been unable to come back since train service from eastern India to Kerala has not resumed. With poverty and distress deepening in their native places, many workers have borrowed money to travel by air to Kerala. The advisory issued by the state necessitates migrant workers arriving Kerala without employers to undergo rapid COVID antigen tests at their own expenses (GOK 2020e).

14 Response of the State to the Crises of Migrant Workers

Within fifteen days of the diagnosis of the first COVID-19 case in India, National Health Mission, Government of Kerala, working with NGOs prepared and disseminated COVID prevention messages in multiple languages. The DOLS on 18 March 2020 issued a circular designating state, district and subdistrict officials to conduct COVID-19 awareness programmes among migrant workers (GOK 2020f). The circular instructed officials to identify and map areas where workers resided and also obtain WhatsApp contact details of at least one worker per area to create a group for disseminating information. Daily updates on actions and COVID symptoms among migrant workers were to be reported to the office of the Labour Commissioner. The Department of Local Self-Government (LSGD) on 20 March 2020 issued a detailed order on the roles and responsibilities of LSGs in COVID interventions and preventive measures to be undertaken. This order identified migrant workers as one of the vulnerable groups and emphasised the need to gather data about such workers in each LSG and impart the awareness programmes. The order mandated daily reports from each LSG on the actions taken (GOK 2020g). Kerala was well prepared for a lockdown by the time the national lockdown was announced on 24 March 2020.

With the announcement of the national lockdown, the government quickly acted. The government entrusted the 1200 LSGs including the Panchayats and Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) to ensure that the migrant workers had food and shelter working with Labour and Skills, Revenue, Civil Supplies, Health and Family Welfare and other relevant departments. Over 20,000 residential pockets identified by LSGD and DOLS were treated as in situ relief shelters of migrant workers, and some new camps were also set up to decongest the existed worker accommodations (GOK 2020b; Nath No Date). In the absence of hotels and restaurants, community kitchens were opened at LSGs to provide food at a moderate cost of ₹20 per person to those who stayed in lodges, hostels or other facilities. Free food was provided from the community kitchens to the destitute, beggars, bedridden patients and the poor. However, initially migrant workers were initially not provided food free of cost (GOK 2020d). The government not only resolved this eventually, but also attempted to provide food by providing food materials or engaging cooks from among the workers (Arnimesh 2020).

The employers were given instructions to take care of the food and accommodation of all their workers, and the house owners with migrant workers as tenants were directed to provide them food. The house owners were unable to do so since they could not afford to it and it was practically not feasible. However, given the penetration of mass media in Kerala, the instructions of Government of India (GOI) to provide salary to workers for the period lockdown and not to charge rent from tenants also helped in preventing large-scale evictions. Although salaries were not provided by most of the employers to the migrant workers, they provided the workers with food and shelter. At the same time, there were also marginal contractors who had struggled to feed migrants employed by them. Eventually, the community kitchens were instructed by the state to provide free food to the footloose migrant workers also (GOK 2020h). The Civil Supplies Department provided rice/atta to migrant workers through with LSGD, DOLS and Department of Revenue (GOK 2020i). The milk collected from farmers, that could not be processed, was distributed among migrant workers in addition to the children enrolled in anganwadis and pregnant women in the state (Nidheesh 2020).

On 28 March 2020, the Department of Health Services rolled out India’s first active mobile COVID screening unit for the migrant workers (Kuruvila 2020). The mobile clinic provided treatment to minor ailments as the workers were unable to seek healthcare coming out of the camps and also screened the migrant workers for COVID symptoms. Both the COVID helpline of the Department of Health Services and the helpline of the DOLS in Ernakulam district provided information services to distressed migrant workers in their mother tongue engaging the Link Workers (Ragesh 2020). Messages on COVID prevention were circulated in Assamese, Odia, Bengali, Hindi and Tamil. Home guards and volunteers who speak the language of the workers were also engaged to interact with the migrant workers to understand and address their grievances. Senior government officials such as the Labour Commissioner and State Police Chief who also were migrants aired messages in the mother tongue of workers which was circulated through the WhatsApp groups of migrant workers established by the DOLS. Many senior officials also visited migrant worker camps to comfort them. Recreational items including televisions and carom boards were also distributed in some camps so that the workers do not sit idle and distressed (Arnimesh 2020).

With GOI announcing Shramik special trains, the departments worked together to screen workers for COVID and facilitated their return to native places. The buses of Kerala Police and Kerala State Road Transport Corporation moved registered workers to various railway stations. Free food and water were provided to the workers who travelled to their native places in Shramik trains. When flagged, the DOLS intervened to release labourers who were forcefully detained by employers.

Collective efforts of the volunteers, activists, Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), corporate entities, contractors, employers and those who lived in their neighbourhood also substantially supported migrant workers and families. Support included donation of food and provisions, masks and sanitisers, setting up multilingual helplines and public announcements, preventing forced detention, providing healthcare services, helping workers to travel to native states and connecting them to public services. Social media groups were also created at national level to facilitate interstate support to migrant workers.

15 An Analysis of the State Response to the Crisis of Migrants

Kerala’s exceptional and fairly inclusive response to the crisis faced by the interstate migrant workers due to the COVID pandemic stands out when compared to the ad hoc responses of other Indian states. The informed and decentralised response points to the overall disaster preparedness of the state firmly rooted in its experience and lessons learned from the rain disasters that had occurred in the state during 2018 and 2019 and also the Nipah virus outbreak in 2018. The state was devastated by the floods and landslides that had occurred in the state in 2019 where over 5000 landslides and landslips of various intensities shook the state and floods inundated more than 60 per cent of the villages in the state displacing 1.5 million people (Thummarukudy and Peter 2019). The floods and landslides during 2019 also impacted 13 out of the 14 districts in the state.

The need assessment conducted after the 2018 disasters by the United Nations with GOK identified interstate migrant workers as one of the groups that were severely impacted. The assessment estimated that about 2.3 million interstate migrant workers lost their livelihoods (GOK et al. 2018). A study exploring how the migrant workers were impacted by the 2018 disasters found out that the migrants were discriminated in rescue, relief and rehabilitation. They had missed the alerts in local languages resulting in poor preparedness and were by and large put in exclusive relief camps for migrants, many of which were prematurely closed leaving them without food and shelter. They also were missed out in the drug administration to prevent spike of cases of leptospirosis after the flood. The damage and loss assessment also was not inclusive, resulting in the eligible workers missing the compensations (Peter and Narendran 2019).

The lessons learned from these disasters resulted in a more resilient, inclusive and decentralised response driven by the LSGs as the COVID pandemic hit the state. Kerala now recognises interstate migrant workers as a population vulnerable to disasters (GOK 2019c). The experience from the two state-wide disasters substantially improved its overall disaster preparedness including mapping migrant pockets, disseminating multilingual messages, entrusting LSGs to response at ward level and DOLS designating officials from grassroots to state levels. The sensitivity of the state-level officials to the issues of migrant workers also has been a key factor that resulted in a proactive response.

While the government has played a very crucial role in alleviating the distress of migrant workers through policy measures at state level, it has enumerated and was directly involved in providing food and other services to only about 4.3 lakhs of workers in the state, whereas the estimate of interstate migrant workers in 2019 tallies to over three million (GOK 2020b; GOK et al. 2018). Also, there is a popular perception outside Kerala that the Government of Kerala set up over 20,000 new relief shelters for migrant workers, largest in India (The Wire 2020). In reality, majority of these ‘shelters’ were places where the migrant workers normally resided at the accommodation provided either by their employer/contractor or taken on rent by themselves, recognised as ‘shelters’ for the provision of relief, and were not new relief shelters set up to which workers moved in during the lockdown. Although a large number of workers, particularly footloose labourers, had returned to the native place before lockdown and the government facilitated travel of over three lakhs persons during the lockdown and there were others who travelled in buses to native states, it appears that the majority of the migrant workers in the state continued to remain in the state despite having not received services from the state during the period of lockdown. CMID’s field insights also support such a possibility. This points towards a much larger role played by the employers, contractors and CSOs in providing food and shelter to migrant workers.

A host of other factors may also have played pivotal roles in alleviating the distress of migrant workers in the state. Unlike in many other states, there is only a negligible proportion of migrant workers who live on the pavements/under the flyovers or in open spaces. Most workers live in pucca structures, however dilapidated they are, with access to drinking water and toilets. The proportion of migrant families in the state are also relatively lesser unlike in many urban centres in northern India. It was perhaps easier for the single migrants to stay back with minimal resources and access to fewer meals. Also, the minimum distance to be travelled by a worker in Kerala to any eastern Indian state was over a 1500 km which may have served as a deterrent against the option of walking homewards. In addition to the response of a vibrant civil society in the state, Government of India’s various measures to alleviate the distress of migrant workers have also been beneficial to the workers in Kerala.

None of the forgoing discussion undermines the exceptional role played by GOK in mitigating the distress of migrant workers in the state during national lockdown. Most of the evidence informed steps by the state fostered disaster risk reduction of the migrant workers during the pandemic. The state was also able to undertake necessary midcourse corrections for enhancing the inclusivity of the response through measures such as making migrant workers also eligible for free food from community kitchens although they were excluded initially. A more inclusive response perhaps would have been possible by proactive engagement of the employers and CSOs working with migrants by involving them in the committees and core teams that were set up to address the challenges faced by the workers rather than keeping it by and large driven by officials with limited understanding of the grassroots realities. Entrusting the room owners and marginal contractors to provide food to migrants could have been avoided as it resulted in food shortage faced by the footloose labourers. Appointing a senior officer from social justice as nodal officer instead of a police officer would have been a more sensitive approach than portraying it as a law and order issue. Extracting the train fare from the migrant workers for Shramik trains at the time of distress also did not augur well for a state which highly depends on migration. Delegating food supply exclusively to LSGs would have worked better without duplication/confusion compared to the arrangement of LSGs providing food through community kitchens, while DOLS and revenue department played a major role in the supply of provisions. Besides, keeping the community kitchens live till the livelihoods of the workers were restored could have helped the workers better since winding them up resulted in workers struggling for food at some places.

16 Conclusion

This paper has analysed labour migration to Kerala and has examined key measures by the GOK to promote the social security of the migrant workers and inclusiveness of the response of the state to the distress of migrant workers during the national lockdown by synthesising the available secondary evidence. The welfare measures as well as interventions initiated by the state are exemplary and promising given the intent and provisions under the schemes. However, some measures appear to have been taken without due consideration of the grassroots requirements and implementation mechanisms to enhance access. In the absence of institutionalised and pragmatic arrangements carefully envisaged to implement and monitor the programmes ensuring synergy within and between departments, these measures have rather been tangential than being complementary. As a result, the policy intent and substantial investments have not yielded commensurate results.

Kerala’s experience to promote the welfare of migrant workers in the state offers important lessons for the inclusion of migrant workers in India. Increasingly, internal migration in India is driven by social networks as evident from Kerala. The Interstate Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Services) (ISMW) Act, 1979, in its current from only applies to the workers recruited by the contractors at their native states and engaged in another state. In order to ensure that all interstate workers benefit from the welfare provisions of the act, in line with the recommendation of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on labour reviewing the Labour Code on Social Security, the current definition of migrant worker in the Act needs to be expanded to include those who move on their own. Besides, the ISMW Act has been one of the legislations that have remained only on paper and substantial reinforcements in human resources may be required to strengthen the department of Labour at state levels to ensure that migrant workers benefit from the provisions of the legislation.

The workers will significantly benefit from comprehensive schemes similar to IMWWS 2010 of GOK that consider not only social security of the worker, but the entire family at the destination. Enrolment in such schemes should be kept simple without the worker needing to pay, produce certificates from employer/officials at the destination or native place or going through annual renewals that require complex paper work. The monthly income ceilings for eligibility if any in both ISMW Act and state-level schemes should be decided in a realistic manner to ensure inclusion of maximum workers than keeping the welfare measures tokenistic. At the same time, care should be taken to avoid schemes such as Aawaz that duplicate components of an existing scheme as it may result in weakening of the systems as well as uptake of both the schemes. Also, harvesting biometric data of the workers beyond minimum requirements amounts to surveillance and should be avoided.

While GOI aims to achieve 100 per cent interstate portability of Public Distribution System (PDS) by March 2021, in the process, GOI should prioritise high migration corridors unlike the way it was done in the case of Kerala where states which supply over 80 per cent of the workforce currently do not figure out among the 11 states with which portability has been already established. Also, for the migrants to benefit from the interstate portability of PDS, GOI may consider individual PDS cards instead of family cards since in long-distance migration for work, most of the family members stay behind in the villages.

Instead of models like Apna Ghar of Kerala where state socially segregates migrant workers and subsidises the employer’s expenses on housing, priority should be given to addressing the housing needs of the most vulnerable workers such as footloose labourers or migrant families. The shelters should be close to their work places/labour nakas, but workers should not be trapped in an industrial area without much access to public provisions. The state may not be able to provide housing to all, but can play the role of a regulator. These could be done at LSG level than entrusting it to the Department of Labour which generally is under-resourced to implement its own programmes. The CSOs can play the role of service facilitators rather than government directly implementing it or outsourcing it to private entities. Instead of exclusive housing for migrants which results in segregated spaces, mainstreaming models work better where workers/families live among others through rental housing that are not exploitative.

Kerala’s experience also reveals that fragmented initiatives for migrant welfare by various departments result in suboptimal outcomes although services may be complementary. Institutional mechanisms should be evolved at state, district and LSG levels to ensure synergy. It is ideal to have a nodal agency with dedicated resources at the state level to plan, facilitate and monitor welfare of migrant workers and their families. Such nodal agencies should also unlock and leverage the unique potentials of Employer and Business Membership Organisations, CSOs and migrant workers. The Trade Unions in India have a substantial role to play so that the migrant workers benefit from the immense social capital created by the unions across Indian states.

The state’s response to the distress of migrant workers during the national lockdown emanates from its historic social capital and more importantly from the overall disaster preparedness and resilience it has achieved from confronting with two consecutive state-wide natural disasters that had devastated Kerala during 2018 and 2019. These disasters had marked migrant workers as a vulnerable group that was left behind and a priority group for future disaster risk reduction initiatives. The lessons learned from the disasters resulted in a more resilient, inclusive and decentralised response driven by the LSGs compared to the unprepared and ad hoc response in 2018 led by the Department of Revenue with a weak presence at the grassroots (Rajesh and Peter 2019). While the GOK has played a strategic role in alleviating the distress of migrant workers through policy imperative and ensuring a synergistic response, the data presented by the state indicate a much larger but invisible role played by the employers, contractors and CSOs in providing food and shelter to migrant workers. A host of other geopolitical factors also appear to have favoured the state in reducing the intensity as well as visibility of the distress experienced by the migrant workers during the lockdown. Kerala’s response also underlines the importance of decentralised governance and management and the challenges faced by the migrant workers by activating LSGs, particularly the ULBs. This calls for nationwide interventions to sensitise the ULBs and ensure inclusive local governance without the sedentary bias.

With the birth and death rates coming to a saturation in many advanced economies, it is migration that will decide the future of the population composition in such areas. This has also brought migration to centre of global politics. Kerala perhaps will be the first Indian state to pass through this phase of the global demographic trajectory. The state, instead of officially promoting ‘Othering’ through portraying the workers who are legitimate Indian citizens as ‘guests’, should construe migration from the rest of India as a win–win solution for the state and an opportunity to diffuse its much appreciated advanced human development to some of the most deprived regions of the country realising that these workers and their families are an integral part of Kerala’s social fabric.

Notes

Based on the call data analysis from Bandhu Helpline, a multilingual helpline implemented by CMID in partnership with ESAF Bank and Gram Vikas during the COVID 19 lockdown for the support to distressed migrant workers in Kerala.

References

(01 July 2020). With No Special Trains, Guest Workers from Kerala Borrow Money to Fly Home. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kochi/no-spl-trains-guest-workers-borrow-money-to-fly-home/articleshow/76717432.cms?frmapp=yes&from=mdr. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

(28 May 2020). Migrant workers must not be charged for train or bus fare, states should provide meals, rules SC. The Scroll. https://scroll.in/latest/963167/migrants-to-not-pay-for-train-or-bus-fare-states-to-provide-meals-at-stations-says-supreme-court. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

(31 March 20). Now, Perumbavoor rocked by migrant worker unrest. The New Indian Express. http://cms.newindianexpress.com/cities/kochi/2020/mar/31/now-perumbavoor-rocked-by-migrant-worker-unrest-2123618.html. Accessed 16 September 2020.

(7 May 2020). Migrant workers organise protest in Payyannur, Koothattukulam. The Mathrubhumi. https://english.mathrubhumi.com/news/kerala/migrant-workers-organise-protest-in-payyannur-koothattukulam-1.4743070. Accessed 16 September 2020.

(09 April 2020). Kerala Govt Running 65% of Shelter Camps for Migrants After Lockdown: Centre to SC. The Wire. https://thewire.in/law/kerala-centre-supreme-court-lockdown-migrant-labourers-shelter. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

Abraham, Rajesh. 2020, 09 June. Kerala buses made crores taking Bengal workers home. The New Indian Express. http://cms.newindianexpress.com/states/kerala/2020/jun/09/kerala-buses-made-crores-taking-bengal-workers-home-2153979.html. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

Anand, S. 1986. Migrant construction workers in Kerala: A case study of Tamil workers in Kerala (Unpublished M.Phil. Dissertation). New Delhi: Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Arnimesh, Shanker. 2020, 18 April. Rotis, mobile recharges, carrom boards—How Kerala fixed its migrant worker anger. The Print. https://theprint.in/india/rotis-mobile-recharges-carrom-boards-how-kerala-fixed-its-migrant-worker-anger/403937/. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

Bhat, Prajwal. 2020, 27 March. Migrant workers in Kerala forced to walk to Karnataka border, sheltered in Kodagu. The News Minute. https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/migrant-workers-kerala-forced-walk-karnataka-border-quarantined-kodagu-121296. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

Caritas India. 2020. The New Exodus: The Untold Stories of Distress Among Migrants During COVID-19: A Rapid Research Report, 2020. https://www.caritasindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/The-New-Exodus-The-Untold-Stories-of-Distressed-Migrants-during-Covid-19.pdf. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

Centre for Migration and Inclusive Development. 2020. Interstate Migrant Workers in Ernakulam District, Kerala: Report of the Baseline Survey. New Delhi: Caritas India.

Desai, Renu. 2019. The Apna Ghar Projects by Bhavanam Foundation Kerala and the Questions It Raises for Migrant Workers’ Housing in Indian Cities. In Here Hope Has No Address: Proceedings of the Workshop on Housing for Migrant Workers. Ahmadabad: Prayas Centre for Labour Research and Action.

Emmanuel, Gladwin. 2020, 19 May. Migrant workers stranded in Kerala grow restless, start to walked to UP and Bihar, Stopped by Police. Mumbai Mirror. https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/coronavirus/news/migrant-workers-stranded-in-kerala-grow-restless-start-to-walk-to-up-and-bihar-but-stopped-by-police/articleshow/75824986.cms. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

Government of Kerala, United Nations, Asian Development Bank, The World Bank, European Union Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid. 2018. Kerala Post Disaster Needs Assessment Floods and Landslides – August 2018. Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Kerala.

Government of Kerala. 2020a, 12 December. Letter No. DSO/EKM/1/2020-CS10 dated 12 December 2020 on interstate portability. Ernakulam: District Civil Supplies Office.

Government of Kerala. 2020b. Statement of the Facts on Behalf of the Government of Kerala in Suo-motu WP(C)06/2020 filed before the Hon’ble Supreme court, Government of Kerala. https://www.livelaw.in/pdf_upload/pdf_upload-375917.pdf. Accessed 16 Sept 2020.

Government of Kerala. 2020c, 26 March. Notice No. A2-2685 (Malayalam). Vengola: District Civil Supplies Office.

Government of Kerala. 2020d, 26 March. Government Order No.713/2020/LSGD (Malayalam). Thiruvananthapuram: Department of Local Self Government.

Government of Kerala. 2020e, 18 July. Advisory on quarantine and COVID-19 testing of guest workers returning to Kerala (No.31/F2/2020/Health. Thiruvananthapuram: Health and Family Welfare Department.

Government of Kerala. 2020f. Circular Number: 8/2020 (Malayalam) dated 18/03/2020. Thiruvananthapuram: Office of the Labour Commissioner.

Government of Kerala. 2020g. Government Order Number: 5/2020 LSGD Malayalam) dated 20/03/2020. Thiruvananthapuram: Department of Local Self Government.

Government of Kerala. 2020h. COVID Prevention: Community Kitchen: Government Order 733/2020 (Malayalam). Thiruvananthapuram: Local Self Government Department.

Government of Kerala. 2020i, 31 March. Letter No.4357721/D2/2020. Department of Civil Supplies. Thiruvananthapuram. https://kila.ac.in/sitedoc/documents/misc/covid19/GO-Circular/1.%20LSGD/8%20Community%20Kitchen.pdf. Accessed on 16 September 2020.

Government of Kerala. 2009. Economic Review 2009. Thiruvananthapuram: Kerala State Planning Board.

Government of Kerala. 2018. Welfare to Rights: Implementation of Select Legislations: A Review. Thiruvananthapuram: Administrative Reforms Commission.

Government of Kerala. 2019a. Economic Review 2018:, vol. 1. Thiruvananthapuram: State Planning Board.

Government of Kerala. 2019b. GO Number 4/2019: Notification Dated 18 January 2019. Kerala Gazette (Extra Ordinary). 8(15): 1–5. http://lc.kerala.gov.in/images/pdf/gos/migrantwrkrswlfrescheme.PDF. Accessed on 16 September 2020.

Government of Kerala. 2019c. Rebuild Kerala development programme: a resilient recovery policy framework and action plan for shaping Kerala’s resilient, risk-informed development and recovery from 2018 Floods. https://rebuild.kerala.gov.in/reports/RKDP_Master%2021May2019.pdf. Accessed on 16 September 2020.

Gram Vikas and CMID. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on migrant labourers from Kalahandi, Odisha. Bhubaneswar: Gram Vikas.

Jan Sahas. 2020. Voices of the invisible citizens: A rapid assessment of the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on internal migrant workers-recommendations for the state, industries and philanthropies. https://ruralindiaonline.org/library/resource/voices-of-the-invisible-citizens/. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

Joseph, Neethu. 2020, 2 May. Migrant workers in Kerala helpless as contractors, govt don’t pay for train tickets. The News Minute. https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/migrant-workers-kerala-helpless-contractors-govt-dont-pay-train-tickets-123862. Accessed 16 September 2020.

Kallungal, Dhinesh. 2020, 13 June. Employers withhold ID cards, deny wages to detain migrants. The New Indian Express. https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/kerala/2020/jun/13/employers-withhold-id-cards-deny-wages-to-detain-migrants-2155903.html. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

Koshy, Sneha, Mary. 2020a, 16 April. Stranded Migrant Workers in Kerala Desperate to Return Home. ND TV. https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/stranded-migrant-workers-in-kerala-desperate-to-return-home-2212548. Accessed 16 September 2020.

Koshy, Sneha, Mary. 2020b, 03 May. Kerala Gives Food To Migrant Workers, They Pay For Train Ride Home. NDTV. https://www.ndtv.com/kerala-news/coronavirus-kerala-gives-food-to-migrant-workers-they-pay-for-train-ride-home-2222274. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

Krishnakumar, S. 2019. Sociological Study on the Conditions of Migrant Workers in the Garment Industry in Ernakulam City Post 2018 Floods. International Journal of Management. 10(4): 68–75.

Kumar, P. 2016. Contours of Internal Migration in India: Certain Experiences from Kerala, 80586. MPRA Paper No: Munich Personal RePEc Archive.

Kuruvila, Anu. 2020, 03 April. 1st mobile COVID screening unit begins operation among migrant labourers. The New Indian Express. http://cms.newindianexpress.com/cities/kochi/2020/apr/03/1st-mobile-covid-screening-unit-begins-operation-among-migrant-labourers-2125005.html. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

Kuttappan, Regimon. 2020, 18 March. Internal Migrants Begin To Leave Kerala Over COVID Scare. The Lede. https://www.thelede.in/kerala/2020/03/18/internal-migrants-begin-to-leave-kerala-over-covid-scare. Accessed 16 September 2020.

Kuttikrishnan, A. P. 2019, State Interventions for Promoting Inclusive Education for Children of Migrant Workers in Kerala: Presentation made at the Consultation on Inclusion of Migrant Children held on June 24, 2019, Thiruvananthapuram.

Bureau, Labour. 2020. Wage Rates in Rural India: March 2020. Chandigarh: Labour Bureau.

Moses, J.W., and S.I. Rajan. 2012. Labour migration and integration in Kerala. Labour and Development 19(1): 1–18.

Nair, Jaikrishnan. 2020, 29 March. Kerala: Migrant workers hit Kottayam streets, demand food, return to native places. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kochi/migrant-workers-hit-kottayam-streets-demand-food/articleshow/74872567.cms. Accessed 16 September 2020.

Narayana, D., C.S. Venkiteswaran, and M.P. Joseph. 2013. Domestic Migrant Labour in Kerala. Thiruvananthapuram: Gulati Institute of Finance and taxation.

Narayanan, Kiran. 2020, 19 March. Virus outbreak leaves migrants jobless. The New Indian Express. https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/kerala/2020/mar/19/virus-outbreak-leaves-migrants-jobless-2118543.html. Accessed 16 September 2020.

Nath, Pranab, Jyoti. No Date. Guest Workers in Kerala Along Time. Linked In. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/pranabjyoti-nath-034a4345_a-documentation-on-migrant-workers-authored-activity-6682158270192336896-9jGL. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

Nidheesh, M. K. 2020, 01 April. Free milk for migrants and kids in Kerala to solve lockdown-induced glut. Mint. https://www.livemint.com/news/india/free-milk-for-migrants-and-kids-in-kerala-to-solve-lockdown-induced-glut-11585758343041.html. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

Parida, J., M. John, and J. Sunny. 2020. Construction Labour Migrants and Wage Inequality in Kerala. Journal of Social and Economic Development. Institute for Social and Economic Change. Springer Publications.

Perappadan, Bindu S. 2020, 30 January. India’s First COVID Infection Confirmed in Kerala. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/indias-first-coronavirus-infection-confirmed-in-kerala/article30691004.ece. Accessed 16 September 2020.

Peter, B., and K. Gupta. 2012. Implications of forest conservation interventions of the judiciary on human migration: An in-depth exploration into the causes of labour migration to plywood industry in Kerala. Indian Journal of Social Development 12(1): 1–14.

Peter, B., and V. Narendran. 2017. God’s Own Workforce: Unravelling Labour Migration to Kerala. Perumbavoor: Centre for Migration and Inclusive Development.

Peter, Benoy, and Vishnu Narendran. 2019. Impact on Migrant Workers in Kerala. In Leaving No One Behind: Lessons from Kerala Disasters, ed. Muraleedharan Thummarukudy and Benoy Peter, 106–115. Kozhikode: Mathrubhumi.

Philip, Shaju. 2020, 01 May. As migrants protest in Kerala, CM Pinarayi Vijayan says Centre’s move impractical. The Indian Express. https://indianexpress.com/article/india/as-migrants-protest-in-kerala-cm-pinarayi-vijayan-says-centres-move-impractical-6388031/. Accessed 16 September 2020.

Planning Commission. 2008. Kerala Development Report. New Delhi: Academic Foundation.

Prasad-Aleyamma, M. 2017. The Cultural Politics of Wages: Ethnography of Construction Work in Kochi, India. Contributions to Indian Sociology. Sage Publications 51(2): 1–31.

Ragesh, G. 2020, 06 April. With 6 languages, this Odia woman helps migrant labourers at Kerala’s COVID control room. Manorama. https://www.onmanorama.com/districts/ernakulam/2020/04/03/bengali-assamese-migrant-worker-queries.html. Accessed on 17 September 2020.

Rajan, I.S., and K.C. Zachariah. 2007. Pilot Study on Replacement Migration (Unpublished). Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies.

Rajesh, K., and Benoy Peter. 2019. Reimagining the Role of Local Self Governments in Disaster Management in Kerala. In Leaving No One Behind: Lessons from Kerala Disasters, ed. Muraleedharan Thummarukudy and Benoy Peter, 178–183. Kozhikode: Mathrubhumi.

Smitha, N. 2020, 18 March. Migrant workers leave in groups from COVID19 hit Kerala. The Asian Age. https://www.asianage.com/india/all-india/180320/migrant-workers-leave-in-groups-from-covid19-hit-kerala.html. Accessed 16 September 2020.

Sreekumar, N. 2019. Challenges Encountered for Enrolment in Aawaz Health Insurance Scheme by Construction Migrant Workers in Kerala. In Health, Safety and Well-Being of Workers in the Informal Sector in India: Lessons for Emerging Economies, ed. S. Panneer, S. Acharya, and N. Sivakami, 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8421-9.

Srivastava, R. 2020. Integrating Migration and Development Policy in India: A Case Study of Three Indian States. Centre for Employment Studies. New Delhi: Institute for Human Development. Working Paper Series 03.

Subrahmani, M. R. 2020, 31 March. Kerala: Migrant Labourers Protest On Streets For The Second Time In Two Days Over Food. Swarajya. https://swarajyamag.com/news-brief/kerala-deprived-of-essentials-migrant-labourers-protest-on-streets-for-the-second-time-in-two-days. Accessed 16 September 2020.

Surabhi, K.S., and N.A. Kumar. 2007. Labour migration to Kerala: A study of Tamil migrant labourers in Kochi. Kochi: Centre for Socioeconomic and Environmental Studies.

Stranded Workers' Action Network. 2020. To Leave or Not to Leave: Lockdown Migrant Workers and their Journeys Home. SWAN. https://ruralindiaonline.org/library/resource/to-leave-or-not-to-leave-lockdown-migrant-workers-and-their-journeys-home/. Accessed 17 Sept 2020.

Thummarukudy, Muraleedharan, and Benoy Peter. 2019. Leaving No One Behind: Lessons from Kerala Disasters. Kozhikode: The Mathrubhumi.

Vineeth, K. 2020, 28 March. Bengali worker seeks police help after starving for more than a day. The Mathrubhumi. https://english.mathrubhumi.com/news/offbeat/bengali-worker-seeks-police-help-after-starving-for-more-than-a-day-1.4649997.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peter, B., Sanghvi, S. & Narendran, V. Inclusion of Interstate Migrant Workers in Kerala and Lessons for India. Ind. J. Labour Econ. 63, 1065–1086 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00292-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00292-9