Abstract

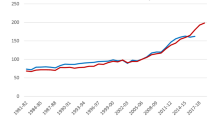

This paper traces the movement of wages of field labour in agriculture, both men and women, among 18 Indian states during the period 2005-06 to 2015-16, based on data from Agricultural Wages in India (AWI) of the Government of India. The estimates assembled show that the state-wise variations in nominal wages have remained stable over the years, suggesting a continued presence of region-specific factors such as differentials in productivity and cost of living, influencing wage levels. The ranking of states with nominal wages has remained almost unchanged; but there are some new entrants to the category of low-wage states. The same goes for gender disparity in wages, which has not increased over the years. However, there was no noticeable reduction of disparity among the states, which have had high estimates to begin with. As for the growth of money wages of men and women, the indices have risen impressively by more than three-fold in most states. One feature that calls for attention is why the more urbanised and industrially advancing states keep on paying inordinately low wages to their unskilled workers in rural areas. The study also flags a number of factors that could plausibly have influenced the absolute level of money wages. It brings out that real wages of men and women have had a consistent, but not spectacular rise, spread over a longer spell in many states. However, there is an ominous tendency for real wages to deteriorate in some industrially advanced states. The relevant indices compiled point to a striking association between the growth of real wages and net state domestic product per capita (NSDPPC) at constant prices. It also suggests that an increase in productivity is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for raising real wages at the lower end of labour markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Operation specific wages of agricultural labourers, yearly averages as well as monthly estimates, of men and women are compiled by the Labour Bureau, Government of India and reported in website of the Ministry of Agriculture: http://eands.dacnet.nic.in/AWIS.htm.

The states of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, included in this study were newly created in 2000 by partitioning the states of Madhya Pradesh and Bihar. Wage data for the new states are available from 2001 onwards.

The methodology of earlier studies is explained in Jose (2017). Earlier, we had followed a lengthy and laborious method of deriving the weighted average wages of men each state using district-wise monthly data on wages, mainly to ensure the comparability of wages from 1956 onwards.

This comes out from the district-wise reporting centers listed and the operation-wise wage data of each center, quoted in the AWI sources of recent years from 2010 onwards. The representability of wage data in recent years, however, remains to be statistically tested.

A new series of ALCP index numbers with base year 2005–06 are published for each state by the Labour Bureau, of the Government of India. They are accessible at: http://labourbureaunew.gov.in.

As explained before, in previous studies, the methodology was to derive the yearly weighted average wages of men and women in each state using district-wise monthly data on wages. The weights used were the district wise share of agricultural laborers as obtained from the Census estimates. The methodology is explained in Jose (2017).

For instance, the average wage of men noted in Kerala during 2015–16 is more than three times the corresponding average reported in Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh or Jharkhand. Such variations, equally pronounced are present in the wages of women workers too.

There is a case for linking these differences to inter-state differences in product per worker within agriculture and the net domestic product per worker in current prices of different states as was done in the previous studies. This will be attempted in a more detailed analysis of wages and the underlying causal factors to be carried out in a sequel to this paper.

It depends a great deal on how the labour markets of regions and industries become integrated and in turn bring some increase and uniformity in wages (Krishnan 1991). In the industrially fast growing states of western India like Maharashtra and Gujarat, whether or not there is any ongoing integration of markets, and how far their absolute wages are downwardly influenced by the inflow of migrant workers remain to be analysed with more empirical evidence. Earlier in Jose (2017) a preliminary attempt was made to explain the wage differentials across states in relation to a number of factors such as product per worker, agro-climatic factors, and the spread of commercial agriculture. A statistical analysis of the causal factors underlying wage differentials is outside the scope of this exercise.

Among the states with high wages for men, Punjab seems to have stopped reporting the wages of women in recent decades.

Towards the end of this paper, we will make a preliminary effort to correlate the growth of agricultural wages in different states to the corresponding growth of state domestic product per capita.

A cursory glance at the state level data for rural areas furnished by the National Sample Survey (NSSO 2017) suggests a strong association between these variables and agricultural wages.

Ester Boserup argued that as cropping patterns shifted from long-fallow to short-fallow and then to more intensive cropping, consequent on a rise in productivity of land and labour, women tended to withdraw from subsistence farming and engage themselves in unpaid work within precincts of their households.

The index numbers for two states: Jharkhand and UP have been derived with 2006–07 as the base year. The wage rates of men and women in Jharkhand during 2014–15 and therefore their index numbers have been extrapolated from averages of the preceding and succeeding years. Likewise, the wage indices of women in Assam during 2009–10 and in UP during 2010–11 have been derived through extrapolation.

There were notable exceptions to the general patterns. The details are discussed in Jose (2017).

The states are: AP, Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, MP, Orissa, UP and West Bengal (both men and women) and Punjab and Tamil Nadu (men only).

References

Acharya, S. (2018), "Wages of Manual Workers in India—A Comparison Across States and Industries", Draft Paper. Institute of Human Development, New Delhi.

Bardhan, K. (1977), "Rural employment, wages and labour markets in India: A survey of research parts I, II, and III" Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 12, No. 23, pp. 26–28.

Boserup, E. (1965), The Conditions of Agricultural Growth, Aldine Publishing Company, New York.

Dasgupta, S. and R. Sudarshan (2011), "Issues in labour market inequality and women’s participation in India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Programme" Working Paper No. 98, Policy Integration Department, International Labour Organization, Geneva.

Krishnan, T.N. (1991), "Wages, employment and output in interrelated labour markets in an agrarian economy-A study of Kerala", Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 26, No. 26, pp. A82–A96.

Jose, A.V. (2017), "Real Wages in Rural India", in K.P. Kannan, R. Mamgain and P. Rustagi (eds.) Labour and development- Essays in honour of Professor T.S. Papola, Academic Foundation, New Delhi

Jose, A.V. (2013), "Changes in wages and earnings of rural labourers", Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 40, No. 8, pp. 26–27.

NREGA (2005), The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005, The Gazette of India Extraordinary, NREGA, New Delhi.

NSSO (2017), Key Indicators of Unincorporated Non-Agricultural Enterprises (Excluding Construction) in India, NSS 73rd ROUND, Appendix Tables A9 and A11, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, New Delhi.

Reserve Bank of India (2018), Handbook of statistics on Indian economy, RBI, Mumbai.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge with thanks the comments on an earlier draft from Sarthi Acharya.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jose, A.V. Agricultural wages in Indian states. Ind. J. Labour Econ. 60, 333–345 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-018-0111-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-018-0111-x