Abstract

In this paper, the impact of sea surface temperature (SST) data assimilation on the results of a finite volume community ocean model has been examined by using the nudging scheme. In this regard, the advanced very high-resolution radiometer satellite SST data were selected as the observational data for assimilation. The numerical modeling was performed over the Persian Gulf from 1998 to 2003 in two different modes: with and without SST data assimilation. The performance of data assimilation with the nudging scheme was evaluated by comparing the simulated SST with the in situ SST measurements and optimum interpolation SST data. Both the spatial and temporal comparisons show the efficiency of assimilation in correcting the model results. The spatial root mean square error in the assimilated run depicts meaningful improvements in the whole of the domain. Also, the temporal comparisons of the results show the capability of assimilation in lowering the model output errors. The simulated SST obtained by applying the data assimilation in the shallow parts of the Persian Gulf matched exactly with the measured ones, especially near the Hormuz Strait. Finally, the results show significant improvements in the SST simulated by using the nudging schemes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Sea surface temperature (SST) is one of the most important variables for studying the ocean and the atmosphere and their interactions. Because of its importance and simple methods for measuring, there is a considerable amount of in situ measurements. In marine science, SST has a key role in research of climate change. Due to the importance of the ocean's upper level in studying the processes which occur at the interface of water and the atmosphere, the satellite SST data can be accessed by the users less than 3 h after measurements. The accuracy of SST can definitely facilitate a better understanding of these processes. Although in situ measurements are the most exact method, due to scarcity of these data, using satellite observational data is the most appropriate option to compensate for this lack. Fortunately, the collection of SST maps has been accomplished by satellite sensors for more than three decades.

Nowadays, use of the SST product from satellite sensors due to its wide coverage (> 1000 km2) and suitable spatial (~ 1 km at nadir) and temporal (two times per day) resolutions has been habitual (Kilpatrick et al. 2015).

Although the recent and improved ocean models can simulate many of the characteristic parameters of the ocean systems, the model outputs have some errors due to uncertainty in factors such as initial and boundary conditions and the intrinsic numerical and input data errors.

Inaccurate numerical simulation of wind-induced phenomena like wind waves and wave-induced currents in the Persian Gulf is a result of the lack of offshore wind stations and heat flux data; this is a considerable source of error for this simulation.

Therefore, to reduce the simulation errors, nowadays, remotely observed data are combined with ocean models by using data assimilation methods.

The first attempt in employing data assimilation in ocean research was the assimilation of SST and vertical profile measurements in a global circulation model by Derber and Rosati (1989). Carton and Hackert (1990) did the same work by adding a correction technique into the Tropical Atlantic model. Clancy et al. (1990, 1992) combined synoptic ship, bathythermograph, buoy and satellite data with the prediction of a mixed-layer model by using an optimal interpolation (OI) scheme. Behringer (1994) applied an objective interpolation scheme for assimilating SST and expendable bathythermograph (XBT) observations to improve the SST maps.

The most common techniques in data assimilation are nudging, 3D and 4D variational methods, optimal interpolation and the Kalman filter (KF). Manda et al. (2005) recognized the skill and feasibility of the nudging method as compared to sophisticated assimilation methods such as the ensemble Kalman filter (EnKF) for estimating the upper mixed layer of the ocean.

Also, many previous studies have been carried out to recognize the SST pattern and variations in the Persian Gulf. Shirvani et al. (2015) denoted increasing Persian Gulf SST over approximately the last 20 years. Johns et al. (2003) studied the heat and freshwater budgets of the Persian Gulf and showed an annual heat loss of about −7 ±4 W/m2 in this domain. Nazemosadat (1998) showed a relationship between the Persian Gulf SST and drought diagnostics in the southern parts of Iran. Nazemosadat et al. (2008) depicted the effect of El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) on the Persian Gulf SST. Glibert et al. (2002) showed that the SST is the governing item controlling fin-fish dynamics and is related to summertime fish kills in Kuwait Bay. Sheppard and Rayner (2002) associated coral bleaching in the southern part of the Persian Gulf to high seawater temperatures.

In this study, the nudging scheme was used to assess the ability of this assimilation scheme to improve the structure of the temperature field in a high-resolution setup of a finite volume community ocean model (FVCOM; Chen et al. 2006). After the SST assimilation process, the modeled oceanic state variables were compared with the observed data to evaluate the improvement yielded by the assimilation procedure.

The structure of this paper is as follows: first, the FVCOM is briefly described and then the observational data, statistical methods and nudging assimilation scheme are illustrated. Next, the results of the effects of the SST assimilation on the SST and subsurface temperature profiles are presented. Finally, a summary and discussion are offered.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 FVCOM

The model used for this study is the FVCOM which has been described in its manual (Chen et al. 2006); it uses an unstructured grid, 3D primitive equations and fully coupled current–wave–ice data. This model was originally developed by Chen et al. (2003) and modified and upgraded by a joint effort of the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth (UMASS-D) and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (Chen et al. 2006). The FVCOM is governed by seven primitive equations of momentum, continuity, temperature, salinity and density in the spherical coordinate system, with turbulent mixing parameterized by the general ocean turbulence model (Burchard 2002) in the vertical orientation and the Smagorinsky turbulent closure scheme in the horizontal orientation (Smagorinsky 1963). The flux forms of the governing equations are discretized in the unstructured triangular mesh in the horizontal (Chen et al. 2003) and in the generalized terrain-following coordinate in the vertical (Pietrzak et al. 2002). The FVCOM is integrated with options of various mode splits and semi-implicit schemes in time and the second-order accurate advection schemes in space. The methods using an unstructured grid and finite volume combine the best attributes of the finite difference method for simple discrete computational efficiency and the finite element methods for geometric flexibility. The flux computational approach provides an accurate representation of mass, heat and salt conservation.

In this study, an unstructured mesh was used and the domain was built with a triangular grid. The horizontal resolution of the model grid varies from ~ 5 km near the coast to ~ 25 km in the offshore region of the Persian Gulf. The total numbers of triangular cells and nodes are 30,552 and 15,779, respectively (Fig. 1). As the Persian Gulf is a shallow water system with a mean depth of ~ 38 m, the sigma coordinate was used in the vertical, with a total of ten uniform layers. The Arvand Roud is the main freshwater inflow into the Persian Gulf which formed by combining the Euphrates, Tigris and Karun Rivers (Saleh 2010). The climatological monthly mean of the river inflow was used with an annual mean transport of 1576 m3/s and high-flow seasons between March and May. For vertical mixing and horizontal diffusion, we used the Mellor–Yamada level 2.5 turbulence closure (Mellor and Yamada 1982) and Smagorinsky schemes were employed, respectively. The external and internal mode time steps are 6.0 and 60.0 s, respectively.

The study period is from 1998 to 2003 based on the in situ data availability. The surface forcing including daily surface wind, precipitation, evaporation, shortwave and longwave radiation, and latent and sensible heat fluxes were prepared based on European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) data with 0.5° spatial and 6-h temporal resolutions available from 1998 to 2003, containing a reanalysis product. To modify and localize the wind data set in the domain, the results of Abbaspour and Rahimi (2011) were used.

2.2 SST Data: Assimilation and Comparison

Five years of advanced, very high-resolution radiometer (AVHRR) SST data between 1998 and 2003 were selected for the assimilation. These data were selected due to their low spatial and high temporal resolutions. Ahmadabadi et al. (2009) showed the maximum, minimum and mean of errors for SST in the Persian Gulf as 0.77, −0.09 and ±0.43, respectively, which can be considered acceptable values.

The reported conductivity, temperature and depth (CTD) data produced by the Regional Organization for the Protection of the Marine Environment (ROPME) in the summer of 2001 and the daily optimum interpolation SST data (OISST; Reynolds et al. 2007) were used to assess the assimilation efficiency. It should be mentioned that a large amount of in situ observations was collected during the ROPME cruise in 2001 (Fig. 2).

To compare the results of assimilation procedure with the in situ measurements, three points were separated due to their higher depths relative to other stations at some locations. The bias and root mean square error (RMSE) were used for representation of the quantity of the results as follow:

where xi and yi denote the measured and modeled values, respectively. Moreover, \(\bar{x}\) and \(\bar{y}\) are their average values, respectively.

2.3 The Nudging Method

The nudging method is one of the easiest and oldest schemes among the data assimilation schemes. However, in spite of the above-mentioned characteristics, it is still widely used for many important applications such as forecast applications and operational assimilation systems. Due to its low computational cost, it is known as a fast and practical method. In this method, the model is slowly nudged (relaxed) towards observations at each time step in the model via a Newtonian relaxation term in the prognostic equation of the variable. The nudging method has been used in ocean data assimilation by Holland and Malanotte-Rizzoli (1989) and Malanotte-Rizzoli and Young (1992).

Manda et al. (2005) studied the SST mixing process and used nudging and EnKF methods. They applied both the nudging and the sophisticated nonlinear EnKF assimilation method and then compared the results. They concluded there is not a significant difference between the sets of results.

The nudging scheme is described as follows (Chen et al. 2006):

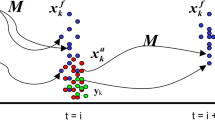

Let \(\alpha (x,y,z,t)\) be a variable selected to be assimilated and \(F\alpha (x,y,z,t)\) represents the sum of all the terms in the governing equation of \(\alpha (x,y,z,t)\) except the local temporal change term. Then the governing equation of \(\alpha (x,y,z,t)\) with inclusion of nudging assimilation is given as

\(\alpha_{0}\) is the observed value; \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{\alpha }\) is the model-predicted value; n is the number of observational points within the search area; \(\gamma_{i}\) is the data quality factor at the ith observational point with a range from 0 to 1; and \(G_{\alpha }\) is a nudging factor that keeps the nudging term scaled by the slowest physical adjustment process. The selection of \(G_{\alpha }\) must satisfy the numerical stability criterion given by

Normally, \(G_{\alpha }\) is set to approximately the magnitude of the Coriolis parameter. \(W_{i} (x,y,z,t)\) is a product of weight functions given as

\(W_{xy} ,W_{\sigma } ,W_{t}\) and \(W_{\theta }\) are horizontal, vertical, temporal and directional weighting functions, respectively. The mathematical expressions of these functions are given as

The weight function used here considers the temporal and spatial variation. Likewise, total weight has a value between 0 and 1. R is the search radius, \(\bar{r}\) is the distance from the location where the data exists, \(R_{\sigma }\) is the vertical search range, \(T_{w}\) is half of the assimilation time window and \(\Delta \theta\) is the directional difference between the local isobath and the computational point with \(c_{1}\) being a constant ranging from 0.05 to 0.5.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Advantages of Using SST Assimilation

The results of 5-year integration, starting from the first of January 1998 have been presented. The simulated SST has been averaged over the integration period and has been compared with the results of survey carried out in this region. To study the efficacy of SST assimilation, the model was run in two stages with the same design: the control run (without assimilation) and assimilation run. Figure 3 presents the daily averaged SST of control and assimilated runs compared with OISST in the whole domain. As can be seen, the assimilated run results correlate well with the OISST data and have an equilibrium mean value of ~ 27 °C. As can be seen in Fig. 3, the control run SST time series in the whole period has been underestimated and the mean temperature reached ~ 26 °C (Fig. 3). The first comparison showed that the assimilated SSTs are almost closer to OISST than the control run in all years.

Figure 4 shows the differences of the control and assimilation run results with respect to OISST. It is obvious that there are little differences between the assimilated results and OISST on the order of ~ 1 °C. At the other side, the control run SSTs have considerable differences with OISST during the whole run time.

Furthermore, the spatial comparisons have been done, too. Figure 5 shows the spatial pattern of the OISST data and both run results. The figure presents remarkable accordance between the SST pattern of the assimilation run results and the spatial pattern of the OISST data. In addition, the figure depicts the efficiency of the assimilation in correcting the spatial pattern of SST in the whole domain, especially in the northern coasts near the Hormuz Strait and in the northwest regions of the Persian Gulf.

Figure 6 shows the RMSE of the control and assimilation run results relative to the OISST. As can be observed from this figure, the accuracy of SST has been increased by using the assimilation methods. The figure presents a slight RMSE in the assimilation run results almost in the entire domain. Also, it can be seen that the maximum RMSE decreased about 13.5 °C.

Figure 7 shows the differences of the simulated SST results in four different months for the control run (left panel) and assimilation run (right panel) with OISST. As can be observed from this figure, the systematic error after assimilation tends to zero in 4 months, which confirms the previous findings on the effectiveness of the assimilation algorithm. Especially, a significant improvement can be seen in the northern part of the domain near the Hormuz Strait, showing the differences of about less than 1 °C. Also, it can be seen that there is egregious disparity between the control run results and OISST.

In order to study the influence of SST assimilation on the subsurface temperature, the vertical temperature profile of two runs were compared with the CTD data of ROPME the cruise.

Figure 8 presents the comparison of both control and assimilation run SST vertical profiles against the corresponding in situ profiles, for three stations identified by stars in Fig. 2. The simulated temperature profiles in the assimilated model are more consistent with in situ measurements. As can be seen from this figure, in the upper 20 m, the difference between observed and assimilation experiment data at the stations is negligible. The assimilated run profiles closer to the field measurement profiles. This figure reveals the impact of SST assimilation in correcting the simulated upper layer temperature. The figure shows that under the stratified layer, the assimilation has little penetration due to the presence of strong stratification which does not allow heat exchange between the upper parts of the mixed layer with lower parts of this layer.

Vertical temperature profiles at the three stations. See the station locations of each profile in Fig. 2

4 Conclusions

This study applied the nudging scheme which enables satellite SST observations to be assimilated into the FVCOM in the Persian Gulf. The results show that the assimilation can effectively improve the thermal structure of the domain not only at the surface but also in the subsurface.

This assimilation method can successfully be applied for satellite SST data, such as that collected by NOAA and other satellites. It was demonstrated that over the period of modelling, the agreement of the assimilated SST with the satellite observation was improved by ∼ 11% in comparison with the regular SST without data assimilation. When the satellite-borne SST data were assimilated into the FVCOM through the nudging scheme, the assimilated model state showed improvements compared to those in the non-assimilative model over all the simulation periods for most of the model domain. The regions with the largest errors were found to be the southern coasts and southwestern portion of the Persian Gulf. The northern regions have low SST errors in comparison with OISST.

References

Abbaspour M, Rahimi R (2011) Iran atlas of offshore renewable energies. Renew Energy 36(1):388–398

Ahmadabadi MN, Arab M, Maalek-Ghaini FM (2009) The method of fundamental solutions for the inverse space-dependent heat source problem. Eng Anal Bound Elem 33(10):1231–1235

Behringer DW (1994) Sea surface height variations in the Atlantic Ocean: a comparison of TOPEX altimeter data with results from an ocean data assimilation system. J Geophys Res Oceans 99(c12):24685–24690

Burchard H (2002) Applied turbulence modelling in marine waters. Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences. Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-45419-5

Carton JA, Hackert EC (1990) Data assimilation applied to the temperature and circulation in the Tropical Atlantic, 1983–84. J Phys Oceanogr 20(8):1150–1165

Chen C, Liu H, Beardsley RC (2003) An unstructured grid, finite-volume, three-dimensional, primitive equations ocean model: application to coastal ocean and estuaries. J Atmos Ocean Technol 20(1):159–186

Chen C, Beardsley RC, Cowles G (2006) An unstructured grid, finitevolume coastal ocean model-FVCOM user manual, 2nd edn. School for Marine Science and Technology, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, New Bedford. Technical report SMAST/UMASSD-06-0602, pp 318

Clancy RM, Phoebus PA, Pollak KD (1990) An operational global-scale ocean thermal analysis system. J Atmos Ocean Technol 7(2):233–254

Clancy RM, Harding JM, Pollak KD, May P (1992) Quantification of improvements in an operational global-scale ocean thermal analysis system. J Atmos Ocean Technol 9(1):55–66

Derber J, Rosati A (1989) A global oceanic data assimilation system. J Phys Oceanogr 19:1333–1347

Glibert P, Landsberg J, Evans J, Al-Sarawai M, Fraj M, Al-Jarallah M, Haywood A, Ibrahem S, Klesius P, Powell C, Shoemaker C (2002) A fish kill of massive proportion in Kuwait Bay, Arabian Gulf, 2001: the roles bacterial disease, harmful algae, and eutrophication. Harmful Algae 1:215–231

Holland WR, Malanotte-Rizzoli P (1989) Assimilation of altimeter data into an ocean model: space versus time resolution studies. J Phys Oceanogr 19:1507–1534

Johns WE, Yao F, Olson DB, Josey SA, Grist JP, Smeed DA (2003) Observations of seasonal exchange through the straits of Hormuz and the inferred heat and freshwater budgets of the Persian Gulf. J Geophys Res Oceans 108(C12):1978–2012

Kilpatrick KA, Podesta G, Walsh S, Williams E, Halliwell V, Szczodrak M, Brown OB, Minnet PJ, Evans R (2015) A decade of sea surface temperature from MODIS. Remote Sens Environ 165:27–41

Malanotte-Rizzoli P, Young RE (1992) No title how useful are localized clusters of traditional oceanographic measurements for data assimilation? Dyn Atmos Oceans 17:23–61

Manda A, Hirose N, Yanagi T (2005) Feasible method for the assimilation of satellite-derived SST with an ocean. J Atmos Ocean Technol 22(6):746–756

Mellor GL, Yamada T (1982) Development of a turbulence closure model for geophysical fluid problems. Rev Geophys 20(4):851–875

Nazemosadat SMJ (1998) The Persian Gulf sea surface temperature as a drought diagnostic for southern parts of Iran. Drought News Netw 10:12–14

Nazemosadat SMJ, Ghasemi AR, Amin SA, Soltani AR (2008) The simultaneous impacts of ENSO and the Persian Gulf SST on the occurrence of drought and wet periods in northwestern Iran, Tabriz University. J Agric Sci 18(3):1–17

Pietrzak J, Jakobson JB, Burchard H, Vested HJ, Petersen O (2002) A three-dimensional hydrostatic model for coastal and ocean modelling using a generalised topography following co-ordinate system. Ocean Model 4(2):173–205

Reynolds RW, Smith TM, Liu C, Chelton DB, Casey KS, Schlax MG (2007) Daily high-resolution-blended analyses for sea surface temperature. J Clim 20(22):5473–5496

Saleh DK (2010) Stream gage descriptions and streamflow statistics for sites in the Tigris River and Euphrates River basins, Iraq. US Geological Survey Data Series 540, p 146

Sheppard C, Rayner N (2002) Utility of the Hadley Centre sea–ice and sea surface temperature data set (HadISST1) in two widely contrasting coral reef areas. Mar Pollut Bull 44:303–308

Shirvani A, Nazemosadat SMJ, Kahya E (2015) Analyses of the Persian Gulf sea surface temperature: prediction and detection of climate change signals. Arab J Geosci 8(4):2121–2130

Smagorinsky J (1963) General circulation experiments with the primitive equations. Mon Weather Rev 91(3):99–164

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Abbasi, M.R., Chegini, V., Sadrinasab, M. et al. Correcting the Sea Surface Temperature by Data Assimilation Over the Persian Gulf. Iran J Sci Technol Trans Sci 43, 141–149 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40995-017-0357-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40995-017-0357-z