Abstract

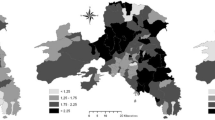

The Princeton European Fertility Project famously studied the determinants of fertility transition using geographical data. The project, however, received criticism for using high-level spatial units that hide much of the variation within. Additionally, although the project underlined the importance of neighbourhood influence through linguistic and cultural similarities, the spatial aspects were not comprehensively studied. This article investigates fertility determinants during the second half of the fertility transition in Estonia, a country with one of the earliest transitions in Europe. We study the completed cohort fertility of married women born between 1875 and 1894 in Estonia at the lowest-level of municipalities. Given the spatial nature of the data, spatial Durbin models are used in addition to the OLS model. The results show that demographic, cultural, educational, economic and spatial influences were all important in determining the level of fertility during the transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The third being that the organised religion must also explicitly state the expected behavioural norms with respect to fertility.

The micro-level data was mostly destroyed after the results were compiled.

Child-woman ratio is a ratio between the number of children under age 5 and the number of women aged 15–49.

We are unable to compute a child-woman ratio for married women from the published census results, since marital status is aggregated for the population aged 15 and more. Micro-level data was destroyed during the Second World War.

The individual records were opened to people alive and living in Estonia from 1926–1944. Thus, women who had died or emigrated beforehand were not included in the Register. This is possibly also a source of bias.

This could be seen from the trends in the rate of illegitimacy and also from the comparison of infant mortality rates between legitimate and illegitimate children. From 1926, the illegitimacy rate, as well as the infant mortality rate for illegitimate children increases considerably.

An opened individual record was not automatically transferred to a new municipality for the most part. This means that internal migration during the 1930s is also partly unregistered in the Family Register data. If the individual record was copied and sent to another municipality, however, the old record was closed with the explicitly stated reason. Thus, we can leave aside such records, and conclude that there are no duplicate records in the study.

The under-registration of infant deaths is the primary concern with historic demographic data. If such deaths are under-registered, the number of children born is underestimated as well.

While the mean number of children is computed on the basis of individual records for 88,004 women born 1875–1894, the child mortality variable is based on records for 75,480 women. The reason for this difference is that the full dates for birth and death for all children are required in order to compute this variable. Thus, we have excluded women with any missing or low-quality information regarding dates. We explore this issue further in the section on robustness checks.

The maximum and minimum values for mean number of children for women aged 35–49 recorded during the 2011 census were 1.47 and 2.9. The standard deviation was 0.27. Number of municipalities was 226.

These are computed based on 1000 simulations with the impacts() command of the spatialreg package.

References

Aarma, L. (1990). Kirjaoskus Eestis 18. sajandi lõpust 1880. aastateni (nekrutinimekirjade andmeil) [Literacy in Estonia from the late 18th century to the 1880s (based on lists of recruits]. Eesti Teaduste Akadeemia.

Anderson, B., Coale, A. J., & Härm, E. (1979). Human fertility in Russia since the nineteenth century. Princeton University Press.

Andresen, L. (2003). Eesti kooli ajalugu: algusest kuni 1940. aastani [The history of the Estonian schools: From the beginning to 1940]. Avita.

Anselin, L. (1995). Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geographical Analysis, 27(2), 93–115.

Barnes, G. A., & Guinnane, T. W. (2012). Social class and the fertility transition: A critical comment on the statistical results reported in Simon Szreter’s “Fertility, class and gender in Britain, 1860–1940.” The Economic History Review, 65(4), 1267–1279.

Basten, S., Huinink, J., & Klüsener, S. (2012). Spatial variation of sub-national fertility trends in Austria, Germany and Switzerland. Comparative Population Studies. https://doi.org/10.12765/CPoS-2011-08

Becker, G. S. (1960). An economic analysis of fertility. In Demographic and economic change in developed countries (pp. 209–240). Columbia University Press.

Becker, S. O., & Woessmann, L. (2008). Luther and the girls: Religious denomination and the female education gap in 19th century Prussia. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 110(4), 777–805.

Benassi, F., & Carella, M. (2022). Modelling geographical variations in fertility and population density of Italian and foreign populations at the local scale: A spatial Durbin approach for Italy (2002–2018). Quality & Quantity. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01446-1

Besser, L. & Ballod, K. (1897). Smertnost, vozrastnoi sostav i dolgovetshnost provoslavnogo naselenia oboego pola v Rossii za 1851–1890 gody [Mortality, age composition and longevity of the Orthodox population in Russia in 1851–1890]. Zapiski Akademii Nauk 1(5).

Bivand, R., Piras, G., Anselin, L., Bernat, A., Blankmeyer, E., Chun, Y., Gómez-Rubio, V., Griffith, D., Gubri, M., Halbersma, R., LeSage, J., Li, A., Ma, J., Mallik, A., Millo, G., Pace, K., Peres-Neto, P., Rüttenauer, T., Sarrias, M., Tiefelsdorf, M. (2021). Spatialreg: Spatial regression analysis (1.1–8) [Computer software]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=spatialreg

Blanc, G. (2021). The cultural origins of the demographic transition in France. Working paper. https://www.guillaumeblanc.com/secularization.html.

Brée, S., & Doignon, Y. (2022). Decline in fertility in Paris: An intraurban spatial analysis. Population, Space and Place, 28(6), e2550.

Brown, J. C., & Guinnane, T. W. (2002). Fertility transition in a rural, catholic population: Bavaria, 1880–1910. Population Studies, 56(1), 35–49.

Brown, J. C., & Guinnane, T. W. (2007). Regions and time in the European fertility transition: Problems in the Princeton project’s statistical methodology. The Economic History Review, 60(3), 574–595.

Burillo, P., Salvati, L., Matthews, S. A., & Benassi, F. (2020). Local-scale fertility variations in a low-fertility Country: Evidence from Spain (2002–2017). Canadian Studies in Population, 47, 279–295.

Campisi, N., Kulu, H., Mikolai, J., Klüsener, S., & Myrskylä, M. (2020). Spatial variation in fertility across Europe: Patterns and determinants. Population, Space and Place, 26(4), e2308.

Carlsson, G. (1966). The decline of fertility: Innovation or adjustment process. Population Studies, 20(2), 149–174.

Cleland, J., & Wilson, C. (1987). Demand theories of the fertility transition: An iconoclastic view. Population Studies, 41(1), 5–30.

Coale, A. J., & Watkins, S. C. (Eds.). (1986). The decline of fertility in Europe. Population Council.

Coale, A. J. (1973). The demographic transition reconsidered. International Population Conference, Liege (pp. 53–72). Clarendon Press.

Comber, A., et al. (2022). A route map for successful applications of geographically weighted regression. Geographical Analysis, 55(4), 1–24.

Costa, R., Bocquier, P., & Eggerickx, T. (2021). The contribution of diffusion to the fertility transition in Belgium (1887–1934). Population and Development Review, 47(2), 411–447.

Daudin, G., Franck, R., & Rapoport, H. (2019). Can internal migration foster the convergence in regional fertility rates? Evidence from 19th Century France. The Economic Journal, 129(620), 1618–1692.

Davis, K. (1945). The world demographic transition. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 237, 1–11.

Doignon, Y., Ambrosetti, E., & Miccoli, S. (2021). The spatial diffusion of fertility decline in Egypt (1950–2006). Genus, 77, 23.

Dribe, M. (2009). Demand and supply factors in the fertility transition: A county-level analysis of age-specific marital fertility in Sweden, 1880–1930. European Review of Economic History, 13(1), 65–94.

Dribe, M., Breschi, M., Gagnon, A., Gauvreau, D., Hanson, H. A., Maloney, T. N., Mazzoni, S., Molitoris, J., Pozzi, L., & Smith, K. R. (2017). Socio-economic status and fertility decline: Insights from historical transitions in Europe and North America. Population Studies, 71(1), 3–21.

Dribe, M., Hacker, J. D., & Scalone, F. (2014). The impact of socio-economic status on net fertility during the historical fertility decline: A comparative analysis of Canada, Iceland, Sweden, Norway, and the USA. Population Studies, 68(2), 135–149.

Elhorst, J. P. (2010). Applied spatial econometrics: Raising the bar. Spatial Economic Analysis, 5(1), 9–28.

Fischer, M. M., & Wang, J. (2011). Spatial data analysis: Models. Springer-Verlag.

Galloway, P. R. (2009). Fertility decline and social democracy in Prussia 1875 to 1910. Working Paper downloaded from: https://www.patrickgalloway.com/galloway_2009_fertility _decline_and_social_democracy_in_prussia_1875_to_1910.pdf.

Goldstein, J. R., & Klüsener, S. (2014). Spatial analysis of the causes of fertility decline in Prussia. Population and Development Review, 40(3), 497–525.

Golgher, A. B., & Voss, P. R. (2016). How to interpret the coefficients of spatial models: Spillovers. Direct and indirect effects. Spatial Demography, 4(3), 175–205.

González-Bailón, S., & Murphy, T. E. (2013). The effects of social interactions on fertility decline in nineteenth-century France: An agent-based simulation experiment. Population Studies, 67(2), 135–155.

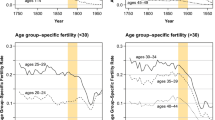

Gortfelder, M. (2020). Fertility modernisation in Estonia: An analysis of individual-level data for women born 1850–1899. Tallinn University.

Gortfelder, M. (2021a). Maltusliku ehk Lääne-Euroopa abiellumustüübi kõrgaeg Eestis [The peak of the Malthusian/West-European marriage pattern in Estonia]. Ajalooline Ajakiri, 177(3/4), 133–167.

Gortfelder, M. (2021b). What influenced early secularization? A statistical analysis of the results of the 1923 referendum in Estonia. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 60(4), 769–788.

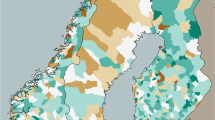

Gortfelder, M., & Jaadla, H. (2022). Sündimuse ruumilised mustrid ja selle põhjused Eestis demograafilise ülemineku ajal [Spatial fertility patterns and its causes in Estonia during the demographic transition]. Acta Historica Tallinnensia, 28(1), 104.

Gortfelder, M., Jaadla, H., & Klesment, M. (2021). Socio-economic status and fertility in an urban context at the end of the nineteenth century: A linked records study from Tartu. Estonia. the History of the Family, 26(1), 51–73.

Gortfelder, M., & Puur, A. (2019). Demograafiline nüüdisajastumine Eestis: 1850–1899 sündinud naiste emaduslugude analüüs [Demographic modernisation in Estonia: An analysis of maternity histories of women born 1850–1899]. Tuna Ajalookultuuri Ajakiri, 21(1), 19–38.

Gortfelder, M., & Puur, A. (2020). Survival and sex composition of offspring: Individual-level responses in the quantum and tempo of childbearing during the demographic transition. Population Studies, 742(2), 161–177.

Guinnane, T. W. (2011). The historical fertility transition: A guide for economists. Journal of Economic Literature, 49(3), 589–614.

Guinnane, T. W., Okun, B. S., & Trussell, J. (1994). What do we know about the timing of fertility transitions in Europe? Demography, 31(1), 1–20.

Haines, M. R., & Hacker, J. D. (2011). Spatial aspects of the American fertility transition in the nineteenth century. In Navigating time and space in population studies (pp. 37–63). Springer

Hajnal, J. (1965). European marriage patterns in perspective. In D. V. Glass & D. E. Eversley (Eds.), Population in history. Essays in historical demography (pp. 101–143). Edward Arnold.

Hallberg, E. (2013). Havrefolket. Studier i befolknings- och marknadsutveckling på Dalboslätten 1770–1930. Göteburg Universitet.

Jaadla, H., Reid, A., Garrett, E., Schürer, K., & Day, J. (2020). Revisiting the fertility transition in England and Wales: The role of social class and migration. Demography, 57(4), 1543–1569.

Junkka, J. (2019). Spatial diffusion of fertility decline in northern Sweden, 1850–1950. Annales de Demographie Historique, 2, 83–117.

Kahk, J., & Tarvel, E. (1997). An economic history of the Baltic countries. Almqvist & Wiksell International.

Karjahärm, T., & Sirk, V. (1997). Eesti haritlaskonna kujunemine ja ideed 1850–1917 [The development and ideas of the Estonian intelligentsia]. Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus.

Kasekamp, A. (2010). A history of the Baltic countries. Palgrave Macmillan.

Katus, K. (1989). Eesti demograafiline areng läbi sajandite [Demographic development of Estonia throughout the centuries]. Eesti Kõrgkoolidevaheline Demouuringute Keskus.

Katus, K. (1994). Sündimus ja selle piirkondlikud erisused Eestis demograafilise ülemineku jooksul. I. [Fertility and its regional differences in Estonia during the demographic transition. I.]. Akadeemia, 6(1), 134–149.

Katus, K., & Puur, A. (2004). Life tables. Estonia 1923–1938 and 1950–2000. Eesti Kõrgkoolidevaheline Demouuringute Keskus.

Klüsener, S., Dribe, M., & Scalone, F. (2019). Spatial and social distance at the onset of the fertility transition: Sweden, 1880–1900. Demography, 56(1), 169–199.

Knodel, J. (1987). Starting, stopping, and spacing during the early stages of fertility transition: The experience of German village populations in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Demography, 24(2), 143–162.

Laur, M., Lust, K., Pirsko, P., & Tarkiainen, Ü. (2014). Talude päriseksostmine: Pärnumaa andmestiku põhjal [The purchase of farms: Based on the data of the county of Pärnumaa]. Eesti Ajalooarhiiv.

Lee, R. D., Galloway, P. R., & Hammel, E. A. (1994). Fertility decline in Prussia: Estimating influences on supply, demand, and degree of control. Demography, 31(2), 347.

Lesthaeghe, R. J. (1977). The decline of Belgian fertility, 1800–1970. Princeton University Press.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Neels, K. (2002). From the first to the second demographic transition: An interpretation of the spatial continuity of demographic innovation in France, Belgium and Switzerland. European Journal of Population/Revue Européenne de Démographie, 18(4), 325–360.

Matthews, S. A., & Parker, D. M. (2013). Progress in spatial demography. Demographic Research, 28(10), 271–312.

McQuillian, K. (2004). When does religion influence fertility? Population and Development Review, 30(1), 25–56.

Mombert, P. (1907). Studien zur Bevölkerungsbewegung in Deutschland in den letzten Jahrzehnten mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der ehelichen Fruchtbarkeit [Studies on the population movements in Germany during the past decades with a particular attention on marital fertility]. Brandsche.

Murphy, T. E. (2015). Old habits die hard (sometimes). Journal of Economic Growth, 20(2), 177–222.

Noodla, K. (1986). Eesti raamatu lugeja XVIII sajandi lõpul ja XIX sajandi algul [Estonian bookreader at the end of the 19th and at the beginning of the 19th century]. In S. Olesk et al. (Eds.), Tagasivaateid kirjanduslukku (pp. 8–30). Eesti Raamat.

Norkus, Z., & Markevičiūtė, J. (2021). New estimation of the gross domestic product in Baltic countries in 1913–1938. Cliometrica, 15, 565–674.

Notestein, F. W. (1945). Population – The long view. In T. W. Schultz (Ed.), Food for the world (pp. 36–57). University of Chicago Press.

Potter, J. E., Schmertmann, C. P., Assunção, R. M., & Cavenaghi, S. M. (2010). Mapping the timing, pace, and scale of the fertility transition in Brazil. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 283–307.

Raun, T. U. (1979). The development of Estonian literacy in the 18th and 19th centuries. Journal of Baltic Studies, 10(2), 115–126.

Raun, T. U. (2002). Estonia and the Estonians. Hoover Press.

Reher, D. S. (1999). Back to the basics: Mortality and fertility interactions during the demographic transition. Continuity and Change, 14(1), 9–31.

Reher, D. S., & Sandström, G. (2015). Dimensions of rational decision-making during the demographic transition; Aranjuez (Spain) revisited. Historical Life Course Studies, 2, 20–36.

Reher, D. S., Sandström, G., Sanz-Gimeno, A., & van Poppel, F. W. A. (2017). Agency in fertility decisions in Western Europe during the demographic transition: A comparative perspective. Demography, 54(1), 3–22.

Reher, D. S., & Sanz-Gimeno, A. (2007). Rethinking historical reproductive change: Insights from longitudinal data for a Spanish town. Population and Development Review, 33(4), 703–727.

Riigi Statistika Keskbüroo (1924a). 1922 a. üldrahvalugemise andmed, Vihk 1: Rahva demograafiline koosseis ja korteriolud Eestis [The results of the 1922 census, Volume 1: The demographic composition of the population and living conditions in Estonia]. Tallinn: Riigi Statistika Keskbüroo.

Riigi Statistika Keskbüroo (1924b). 1922 a üldrahvalugemise andmed (vihud IV–XI): Maakondade tulemused [The results of the 1922 census, Volume 4–11: The results of the counties].

Riigi Statistika Keskbüroo (1923). Esimene rahvahääletus Eestis [The first referendum in Estonia]. Statistika Kuukiri, 2(3), 58–76.

Riigi Statistika Keskbüroo (1935). Rahvastiku koostis ja korteriolud. 1.III 1934 rahvaloenduse andmed. Vihk II [The composition of the population and living conditions. The results of the 1 of March 1934 census. Volume II]. Tallinn: Riigi Statistika Keskbüroo.

Roosaare, J., Liiber, Ü. Aunap, R., Järvet., Pragi, U., Tihemets, K. 2000. Eesti geograafia CD [Estonian Geography]Tartu: Tartu University. [GIS boundaries].

Ryder, N. (2010). On the sociology of fertility reduction. Population and Development Review, 36(3), 607–620.

Saard, R. (2020). Härraskirikust rahvakirikuks: Eesti rahvusest luterliku vaimulikkonna kujunemine ja Eesti Evangeelse Luterliku Kiriku sünd [From the church of the elite to the church of the people: The development of the Estonian national clergy and the birth of the Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church]. Tallinn: Argo.

Sabater, A., & Graham, E. (2019). International migration and fertility variation in Spain during the economic recession: A spatial Durbin approach. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 12(3), 515–546.

Salvati, L., Benassi, F., Miccoli, S., Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H., & Matthews, S. A. (2020). Spatial variability of total fertility rate and crude birth rate in a low-fertility country: Patterns and trends in regional and local scale heterogeneity across Italy, 2002–2018. Applied Geography, 24, 102321.

Sánchez-Barricarte, J. J. (2017). Mortality–fertility synergies during the demographic transition in the developed world. Population Studies, 71(2), 155–170.

Santow, G. (1995). “Coitus interruptus” and the control of natural fertility. Population Studies, 49(1), 19–43.

Schmertmann, C. P., Potter, J. E., & Cavenaghi, S. M. (2008). Exploratory analysis of spatial patterns in Brazil’s fertility transition. Population Research and Policy Review, 27(1), 1–15.

Szreter, S. (1996). Fertility, class and gender in Britain, 1860–1940. Cambridge University Press.

Szreter, S., & Fisher, K. (2010). Sex before the sexual revolution: Intimate life in England 1918–1963. Cambridge University Press.

Teder, T. (1939). Perekonnaseisuametniku käsiraamat. Siseministeerium.

Templ, M., Kowarik, A., Alfons, A., Cillia, G. de, Prantner, B., & Rannetbauer, W. (2021). VIM: Visualization and imputation of missing values (6.1.1) [Computer software]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=VIM.

Vallin, J., Jasilionis, D., & Meslé, F. (2017). Does a turbulent history lead to turbulent life expectancy trends? Evidence from the Baltic States. Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History, 50(4), 191–209.

Van de Kaa, D., et al. (1994). The second demographic transition revisited: Theories and explanations. In G. Beets (Ed.), Population and the family in the low countries 1993: Late fertility and other current issues (pp. 81–126). Amsterdam: Zwets and Zeitlinger.

Van de Walle, F. (1986). Infant mortality and the European demographic transition. In A. Coale & S. Watkins (Eds.), The decline of fertility in Europe (pp. 201–233). Princeton University Press.

Van Poppel, F., Reher, D. S., Sanz-Gimeno, A., Sanchez-Dominguez, M., & Beekink, E. (2012). Mortality decline and reproductive change during the Dutch demographic transition: Revisiting a traditional debate with new data. Demographic Research, 27(11), 299–338.

Vitali, A., Aassve, A., & Lappegård, T. (2015). Diffusion of childbearing within cohabitation. Demography, 52(2), 355–377.

Vitali, A., & Billari, F. C. (2017). Changing determinants of low fertility and diffusion: A spatial analysis for Italy. Population, Space and Place, 23(2), e1998.

Yang, T.-C., Noah, A. J., & Shoff, C. (2015). Exploring geographic variation in US mortality rates using a spatial Durbin approach. Population, Space and Place, 21(1), 18–37.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Estonian Research Council grant (PSG669). We thank anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions on this article. We also thank Alexis Comber for advice regarding multiscale GWR models and Veiko Berendsen for help with data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gortfelder, M., Jaadla, H. Determinants of Fertility During the Fertility Transition in Estonia: A Spatial Analysis. Spat Demogr 11, 5 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40980-023-00116-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40980-023-00116-6