Abstract

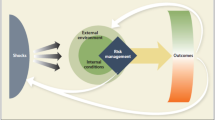

The objective of the paper is to track the association between different type of shocks experienced by rural households and corresponding coping strategies opted by them as they are, not only exposed to household-level and community level shocks, but also, lack effective risk management strategies which make them vulnerable to get into chronic poverty. A probit analysis has been used to articulate the comparative static distinction of risk management strategies between poor and non poor rural households using Additional Rural Incomes Survey/Rural Economic and Demographic Survey (ARIS/REDS) data surveyed by National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) in rural India across 17 states to get a comparative static analysis. Households, generally, withdraw savings, seek remittances from migrant family members, take loan from formal and informal lenders and sell their existing assets and participate in Government sponsored welfare based programs to control after effect of shocks. Comparatively non-poor rural households could build up safety net (precautionary measure) to cope with price rise and other sudden shocks. But, extremely poor, generally, if don’t get help from relatives or can’t borrow from informal sources, ultimately starve at the time of sudden shocks. The welfare based government programs fail to arrest this extreme situation of grief during the idiosyncratic shocks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Despite the diversity of their financial situations, many American households share a surprising vulnerability. Families, even those with higher incomes, can be disrupted by just one financial setback.” http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2015/10/emergency-savings-report-1_artfinal.pdf

b. Rural households in emerging market economies countries are vulnerable to poverty as a result of negative shocks and because of their limited capacity for effective ex-post coping. Tongruksawattana, Waibel and Schmidt (2010).

Dercon et al. (2005) and Calvo and Dercon (2005) defined shocks as “adverse events that lead to a loss of household income, a reduction in consumption and/or a loss of productive assets”. Shocks can generate vulnerability and extreme poverty.

Human Development Report 2014.

Despite having huge policy level intervention for poverty reduction, more than 2.2 billion people are still living either near or below poverty line. That, essentially, signifies that more than 15 percent of the world’s population is still vulnerable to multidimensional poverty (Human Development Report, 2014).

a. The World Bank, in 2011 based on 2005’s PPPs International Comparison Program, estimated 23.6% of Indian population, or about 276 million people, lived below $1.25 per day on purchasing power parity. For details refer to, ‘A Measured Approach to Ending Poverty and Boosting Shared Prosperity—Concepts, Data, and the Twin Goals’, The World Bank, Washington-DC , USA,ISBN (paper): 978-1-4648-0361-1;ISBN electronic): 978-1-4648-0362-8; doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-0361-1.

b. The incidence of poverty in India is a matter of key concern for policy analysts and academic researchers both because of its scope and intensity. National poverty line estimates1 indicated a poverty incidence of 27.5 percent in 2004–2005, implying that over one quarter of the population in India lives below the poverty line. Also, in absolute numbers, India still has 301.7 million poor persons with a significant percentage of them being substantially or severely poor in terms of the norms identified as being necessary for survival. http://www.im4change.org/docs/understanding-poverty-india.pdf.

Various Ministries in the Government of India have come up with various social sector schemes for social and economic welfare development of the nation. The programs are classified into different groups. These are named as, wage employment programs, self-employment programs, food security programs, social security programs and poverty alleviation programs. http://www.gktoday.in/government-schemes-in-india/ http://www.gktoday.in/government-schemes-in-india/.

Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojna, National Urban Livelihood Mission, National Food Security Mission, Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana are few policy programs taken up by GOI for wellbeing of the poor population.

Human Development Report, 2014. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr14-report-en-1.pdf.

The states include Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Orissa, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and, Andhra Pradesh. The state reorganization that influenced Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, did not affect the selection of villages that have remained intact since 1969.

The first three rounds included Assam and Jammu and Kashmir. However, the 1982 round did not include Assam, while the 1999 round excluded Jammu and Kashmir (both incidents affected by the local law and order situation prevailing in these states at that time). The current round excludes both these states.

The household sample has compensated for attrition through a random addition to the original sample since 1982. 10 households were randomly selected from the process of listing in each of the survey rounds. Thus, the sample remains representative.

The listing component of the survey was completed in 2006 while the household survey was administered between 2007 and 2008.

‘Jati’ is synonymous to ‘Caste’ in Hindu society. The word has its origin from Sanskrit and indicates towards a form of existence determined by birth.

The Gini coefficient is a measure of statistical dispersion projected to represent the income distribution of a nation’s inhabitants, and is the most commonly used measure of inequality.

As for example the NREGA, enacted in 2005 by the United Progressive Alliance government, was envisioned as a safety net for rural households. http://nrega.nic.in/nrega_guidelineseng.pdf

Household ties based on kinship.

Gram Sabha has been envisaged as the foundation of the Panchayati Raj system after the enactment of the 73rd Constitutional Amendment Act, 1992. A Gram Sabha consists of members that include every adult (age 18 +) of the village and is generally formed in villages with population at least exceeding 1500 people.Usually in every 5 years the members of the Gram Sabha elects the members of the Gram Panchayat.

Pradhan or Gram Pradhan or Sarpanch, as it is called in India, is the elected head of the Gram Panchayat.

Infrastructure index = [(1-(Distance to wholesale market /Maximum distance to wholesale market)) + (1-(Distance to pucca road /Maximum distance to pucca road)) + (Dummy for villages having motorized bus stand) + (Dummy for villages having milk cooperative societies)]/4

Accessibility of proper public transport, road quality, concentration of whole sale markets etc are the major indicators of infrastructure.

Service index = [(Dummy for villages having public tap) + (Dummy for villages having trained health workers) + (Dummy for villages having schools) + (Number of electricity connections / Maximum number of electricity connections)]/4

Availability of public taps, trained health workers, schools, electricity connection signify strong access to public services.

Technology index =[(Percentage of high yielding verities area per 1000 acres /1000) + (Percentage of pump sets per 1000 acres/Maximum percentage of pump sets) + (Percentage of harvesters and sprinklers per 1000 acres/Maximum percentage of harvesters and sprinklers) + (Percentage of tractors per 1000 acres/Maximum percentage of tractors) + (Percentage of improved buffaloes and cows per 1000 acres/Maximum percentage of buffaloes and cows)]/5

Technology Index in rural areas refers to technology for farm sector. Availability of tractors, high yielding verities of inputs, pump sets etc signify improvement of technology.

Each index is the simple average of scores obtained from the information given by the respondents for related indicators.

Details on the revenue and expenditure programs as defined in survey questionnaire are following.

-

Revenue from higher source (state government, state finance commission, central government certified programs and employment guarantee schemes).

-

Revenue from local government (collect land tax, water usage tax, issues stamp papers, other taxes).

-

Expenditures (drinking water, sanitation and sewages, roads and transformations, irrigations, electrifications, street lighting, credit & input subsidies, communications, school and education, health facilities, natural resource management, employment programs, social issues and ceremonies and etc).

-

Alternative wage employment of rural households is the wage employment excludes the employment programs by the government i.e. household engages themselves in the private sectors.

References

Amendah, Buigut, Mohamed. 2014. Coping Strategies among Urban Poor: Evidence from Nairobi, Kenya. PLOS One 9(1): e83428. Published: January 10, 2014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083428

Basu, K. 1991. The Elimination of Endemic Poverty in South Asia: Some Policy Options. In The Political Economy of Hunger, vol. 3, ed. Endemic Hunger. Jean Dreze & Amartya Sen. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Berloffa, G., and Francesca. 2013. ‘Income shocks, coping strategies, and consumption smoothing: An application to Indonesian data’. Journal of Asian Economics, Elsevier, vol. 24(C), pages 158–171.

Bhattamishra, B. 2008. Community-based Risk Management Arrangements: An Overview and Implications for Social Fund Programs. Social Protection Discussion Paper No. 0830. The World Bank, Washington D.C.

Calvo, C., and Dercon, S. 2005. Measuring Individual Vulnerability. Economics Series Working Papers 229. University of Oxford. Department of Economics.

Cameron, Lisa A., and Worswick. 2003. The labor market as a smoothing device: labor supply responses to crop loss. Review of Development Economics 7 (2): 327–341.

Carter, and Lybbert. 2012. Consumption versus asset smoothing: testing the implications of poverty trap theory in Burkina Faso. Journal of Development Economics 99 (2): 255–264.

Castellanos, and Rahut. 2006. Coping Strategies adopted by rural extreme poor households in Bolivia.mineo. 1–28.

Clarke, D., and Dercon. 2009. Insurance, Credit and Safety Nets for the Poor in a World of Risk. United Nations. DESA. Working Paper No. 81. http://www.un.org/esa/desa/papers/2009/wp81_2009.pdf. Accessed on 20th November 2015.

Dercon, S. 2002. Income risk, coping strategies, and safety nets. The World Bank Research Observer 17 (2): 141–166.

Dercon, S. 2005. Risk, poverty and vulnerability in Africa. Journal of African Economics 14 (4): 483–488.

Dercon, S., J. Hoddinott, and T. Woldehanna. 2005. ‘Shocks and Consumption in 15 Ethiopian Villages’, 1999–2004. Journal of African Economies 14 (4): 559–585.

Fafchamps, M., and Gubert. 2007. The formation of risk sharing networks. Journal of Development Economics 83 (2): 326–350.

Fafchamps, M., and Lund. 2003. Risk-sharing networks in rural Philippines. Journal of Development Economics 71 (2): 261–287.

Gaiha, R. 2000. Do Anti-Poverty Programmes Reach The Rural Poor in India? Oxford Development Studies 28 (1): 71–95.

Government of India. 2008. The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 (NREGA), Operational Guidelines 2008; Ministry of Rural Development Department of Rural Development, Government of India. http://nrega.nic.in/nrega_guidelineseng.pdf.

Heltberg, and Lund. 2009. Shocks, Coping, and Outcomes for Pakistan’s Poor: Health Risks Predominate. Journal of Development Studies 45 (6): 889–910.

http://www.gktoday.in/government-schemes-in-india/ http://www.gktoday.in/government-schemes-in-india/. Accessed on 27 December 2015.

http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2015/10/emergency-savings-report-1_artfinal.pdf. Accessed on 03 May 2016.

http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr14-report-en-1.pdf. Accessed on 03 May 2016.

Jha, R., Nagarajan, and Pradhan. 2012. ‘Household Coping Strategies and Welfare: Does Governance Matter?’. NCAER. Working Papers on Decentralization and Rural Governance in India, Number 14.National Council of Applied Economic Research, New Delhi.

Kazianga, H., and C. Udry. 2006. Consumption smoothing? Livestock, insurance and drought in rural Burkina Faso. Journal of Development Economics 79 (2): 413–446.

Klonner, S., and Oldiges. 2014. ‘Safety Net for India’s Poor or Waste of Public Funds? Poverty and Welfare in the Wake of the World’s Largest Job Guarantee Program’. Discussion Paper Series No. 564, Department of Economics, University of Heidelberg.

Kochar, A. 1999. ‘Smoothing Consumption by Smoothing Income: Hours-Of-Work Responses to Idiosyncratic Agricultural Shocks in Rural India’. The Review of Economics and Statistics, February 1999, 81(1): 50–61.

Kozel, V., Fallavier, P., and Reena Badani. 2009. ‘Risk & Vulnerability Analysis in World Bank Analytic Work, 2000-07’. Social Protection Discussion Paper No. 0812. The World Bank, Washington D.C.

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/SOCIALPROTECTION/Resources/SP-Discussion-papers/Social-Risk-Management-DP/0812.pdf. Accessed on 31 January 2016.

Krueger, Mitman, and Perri. 2016. ‘On the Distribution of the Welfare Losses of Large Recessions’. Staff Report 532, July 2016, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Minneapolis. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/research/sr/sr532.pdf. Accessed on 08 August 2016.

Lal, R., Miller, S., Lieuw-Kie-Song, M., and Kostzer, D. 2010. ‘Public Works and Employment Programmes: Towards a Long-Term Development Approach’. International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth Working Paper No.66.

Mazumdar, Sumit. et.al. 2014. ‘Multiple Shocks, Coping and Welfare Consequences: Natural Disasters and Health Shocks in the Indian Sundarbans’. PLOS One, Open Access Journal.Published: August 29, 2014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105427. Accessed on 5 July 2015.

Okamoto, I. 2011. How do poor rural households in Myanmar cope with shocks? Coping strategies in fishing and farming village in Rakhine state. The Developing Economies 49 (1): 89–112.

Rashid, D. A., Langworthy, M., and Aradhyula, S. V. 2006. ‘Livelihood Shocks and Coping Strategies: An Empirical Study of Bangladesh Households’, 2006 Annual meeting, July 23-26, Long Beach, CA 21231, American Agricultural Economics Association (New Name 2008: Agricultural and Applied Economics Association).

Tongruksawattana, S., Hermann Waibel, and Erich Schmidt .2010. ‘How do Rural Households Cope with Shocks? Evidence from Northeast Thailand’. Paper prepared for the CPRC International Conference 2010: Ten Years of War Against Poverty hosted by the Brooks World Poverty Institute at the University of Manchester 8-10 September 2010 1-20. http://www.chronicpoverty.org/uploads/publication_files/tongruksawattana_waibel_schmidt_thailand.pdf. Accessed on 7 September 2014.

Townsend, R. 1994. Risk and Insurance in Village India. Econometrica 62: 539–592.

Udry, C. 1994. Risk and insurance in a rural credit market: An empirical investigation of Northern Nigeria. Review of Economic Studies 61 (3): 495–526.

“Understanding Poverty in India”, ADB, 2011. http://www.im4change.org/docs/understanding-poverty-india.pdf

World Bank. (2013). World Development Report 2014: Risk and Opportunity. Managing Risk for Development. Washington, DC. http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2015/10/emergency-savings-report-1_artfinal.pdf. Accessed on 2 September 2015.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We are thankful to H. K. Nagarajan, RBI Chair Professor, IRMA, Gujarat, Shashanka Bhide, Director-MIDS, Chennai and NCAER, New Delhi and IDRC, Canada for giving us opportunity to involve in ‘Decentralisation and Rural Governance in India’ project and for sharing us the detailed primary data set for the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pradhan, K.C., Mukherjee, S. Covariate and Idiosyncratic Shocks and Coping Strategies for Poor and Non-poor Rural Households in India. J. Quant. Econ. 16, 101–127 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-017-0073-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-017-0073-8