Abstract

Compulsive exercise commonly coexists with eating psychopathology. While the impact of sociocultural influences on disordered eating has been identified in young people, sociocultural influences on compulsive exercise are yet to be systematically synthesized. This systematic review therefore aimed to synthesize literature examining sociocultural influences from peers, family and media on compulsive exercise, to explore the potential importance of such influences on the development and maintenance of compulsive exercise in young people. A systematic literature search was conducted following PRISMA guidelines in PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, MEDLINE, SPORTDiscus and Web of Science databases up to November 2021. Seven quantitative studies were included (five cross-sectional, two prospective). The review highlighted three key factors underpinning the relationship between sociocultural influences and compulsive exercise in young people: body-related messages from significant others, and unfavorable comparisons with, and pressure to conform to, body image ideals. The findings support the notion that compulsive exercise behaviors and attitudes can be socially determined. However, the limited research with young people necessitates further exploration of sociocultural influences on the development and onset of compulsive exercise in adolescence/young adulthood to develop robust conclusions. It is also crucial that research remains up to date with changing technological influences on exercise behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Compulsive exercise has been linked to the development and maintenance of eating disorders in young people (e.g., Meyer et al., 2011), and the component of compulsive exercise most strongly associated with eating disorders is exercising for weight and/or shape control (Mond & Calogero, 2009). Sociocultural factors have been implicated in the development of disordered eating in adolescents (Field et al., 2001), through mechanisms such as social comparisons and body dissatisfaction (Halliwell & Harvey, 2006; Rodgers et al., 2010). As compulsive exercise is found to prolong treatment of eating disorders (e.g., Levallius et al., 2017), and adolescents are particularly susceptible to social influences (Blakemore & Mills, 2014), it is crucial to address the way in which sociocultural influences can impact on compulsive exercise behaviors and attitudes at this age. This systematic review addresses this research gap by synthesizing and critically evaluating studies that assess sociocultural influences on compulsive exercise behaviors and attitudes in young people.

Exercise is linked to a decreased risk of morbidity and chronic disease and can promote positive self-perceptions and self-esteem (Lubans et al., 2016). However, some individuals report compulsive or obsessive exercise attitudes and behaviors which can be detrimental to both physical and mental health (Lichtenstein et al., 2017; Mond et al., 2006). Compulsive exercise is characterized as a severe and intense drive to exercise, despite illness or injury (Taranis et al., 2011), and as a way to manage negative emotions (Goodwin et al., 2012). Rigid and routine-like in nature, exercise is often prioritized above social and occupational activities, and compulsive exercisers will also often experience high levels of guilt and anxiety should exercise be missed or postponed (Taranis et al., 2011). It is unsurprising, therefore, that compulsive exercise has been found to negatively impact on individuals’ quality of life and psychological wellbeing (Young et al., 2018). As adult exercise behaviors and attitudes are often established in adolescence (Patton et al., 2016), it is crucial to identify the risk factors associated with the development and maintenance of compulsive exercise in young people, prior to consolidation of these behaviors in adulthood.

Young people often use exercise as a method to control their weight and shape (Zach et al., 2013), including prioritizing exercise for appearance over health-related reasons (Patton et al., 2016). Exercising for weight and shape reasons is strongly associated with compulsive exercise (Bell et al., 2016; Schaefer et al., 2015; Uhlmann et al., 2018) and is also one of the dimensions of compulsive exercise most strongly associated with disordered eating (Mond & Calogero, 2009). Indeed, compulsive exercise has been found to maintain symptoms of eating disorders, prolong recovery, and increase the risk of relapse (e.g., Levallius et al., 2017; Meyer et al., 2011). It is therefore important to understand the potential risk factors in the development and maintenance of compulsive exercise in young people, prior to their consolidation in adulthood.

Sociocultural Influences

Young people are more susceptible to social influences than older adults (Blakemore & Mills, 2014), and such influences can significantly impact engagement in exercise behaviors at this age (Davison & Jago, 2009). As sociocultural influences have been found to impact the development and maintenance of disordered eating in adolescents and young people (Field et al., 2001; Halliwell & Harvey, 2006), a greater understanding of the potential impact that sociocultural influences can have on unhealthy exercise behaviors, such as compulsive exercise, is needed in order to support their healthy development.

Parent and Peer Influences

An individual’s family is typically the first form of socialization (Ricciardelli & McCabe, 2002). Parents in particular are an important factor in the development of body-change desires and strategies in children (Hart et al., 2015). Adolescents are more likely to engage in exercise-related activities if their parents do (Christofaro et al., 2018), particularly when adolescents perceive support and encouragement from their parents to exercise (e.g., King et al., 2008). However, messages from parents to exercise to promote body change rather than health is associated with unhealthy body changes strategies in adolescents and young adults, such as disordered eating (Berge et al., 2013; Rodgers & Chabrol, 2009). Peers, however, often become a more salient influence than parents during adolescence (Brown et al., 2007). Adolescents are more likely to engage in eating and exercise behaviors that are modelled by their peers (Hamel et al., 2012), often due to pressure to adhere to the friendship group’s set standard of behaviors and values (Fitzgerald et al., 2012; Kierans & Swords, 2016). While there is evidence to highlight the influence that parents and peers have on eating-related body change strategies (Quiles Marcos et al., 2013), less is known about the role that peers and family play in a young person’s use of other maladaptive body change strategies such as compulsive exercise.

Media Influence

A desire to achieve body types seen on traditional media platforms, such as television and magazines, has been related to an increase in physical activity in adolescents (Taveras et al., 2004). Most adolescents are also now engaging with social media platforms (e.g., Instagram, TikTok and Snapchat) in order to interact with their peers and seek out health-related content (Coyne et al., 2019; Rideout, 2016). Social media has been successfully utilized in interventions to promote positive changes in physical activity and eating-related behaviors in young people (e.g., Goodyear et al., 2021). However, the use of social media has been significantly linked to increased disordered eating and over-evaluation of weight and shape in adolescents (Wilksch et al., 2020). As weight and shape concerns are components of compulsive exercise that are most strongly associated with eating psychopathology (Mond & Calogero, 2009), it is important to gain an understanding of the potential impact that social media can also have on compulsive exercise attitudes and behaviors in young people.

Current Study

Compulsive exercise has been linked to the development and maintenance of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in young people. While research to date has highlighted the role of sociocultural influences on disordered eating in young people, the evidence surrounding sociocultural influences on compulsive exercise has yet to be systematically synthesized, meaning that there has been no consideration of the impact of a range of sociocultural factors on potentially unhealthy compulsive exercise attitudes and behaviors in young people. Given that adolescence, in particular, is a crucial time for the development of exercise and eating-related attitudes, such a review will highlight the potential importance of sociocultural influences on the development and maintenance of compulsive exercise in young people and inform the future development of interventions to address these influences before compulsive exercise behaviors become ingrained in adulthood or contribute to eating psychopathology in young people. The purpose of this systematic review is therefore to synthesize existing literature that explores sociocultural influences on compulsive exercise among young people to enhance our understanding of the role that these sociocultural factors might play on compulsive exercise in this potentially vulnerable population.

Method

Search Strategy

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Page et al., 2021) guidelines were followed. To obtain relevant peer-reviewed articles, electronic database searches were conducted within EBSCOHost (i.e., PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, MEDLINE, SPORTDiscus) and Web of Science with no date restrictions. Searches were conducted up to November 2021. The search strategy combined terminology relevant to compulsive exercise (e.g., compulsive exercise, exercise addiction, exercise dependence, obsessive exercise) with terms relating to sociocultural factors (e.g., peer, family, media) and young people (e.g., teenagers, adolescents, young adults) using the AND Boolean operator. The wildcard function (*) was used with stem words, where appropriate, to ensure variations of terminology and spelling were identified. The same broad search strategy was used for all databases and is presented in Appendix 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included, articles were required to be written in English and to be published in peer-reviewed academic journals. As this review focuses on young people, studies were also required to report that their participants’ ages ranged between 10 and 24 years, to reflect the World Health Organization’s (WHO, 2014) definition of “young people”. Articles were excluded if they did not include a clear measure of exercise psychopathology (compulsive exercise or related construct), or if they did not assess relationships between exercise psychopathology and at least one sociocultural factor (e.g., family, media, peers). Studies were also excluded if athlete populations were recruited, due to established differences in athletes’ exercise perspectives and performance in comparison to the general population (e.g., athlete schedules being routine-like and performance oriented; Plateau et al., 2014). Studies that measured media influence were only included if they stated the type of media content accessed by the participants, to determine the specific media content and/or platform that might be related to compulsive exercise.

Data Extraction

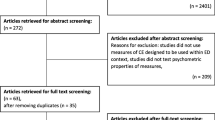

The article selection process is presented in Fig. 1. Studies that met the inclusion criteria (n = 507) were identified and, after the removal of duplicates, 328 articles were screened based on their titles and abstracts. These articles were reviewed by the first author in relation to the inclusion criteria, and any uncertainties around inclusion were discussed with the research team. The initial screening process resulted in 255 articles being removed. Full text review was conducted on 73 articles. Articles in this final review stage that did not meet the requirements for inclusion were excluded either due to the absence of a measure of exercise psychopathology (n = 19) or the absence of an assessment of sociocultural factors (n = 26). Nineteen papers were also excluded as the participant age range was either not reported or did not reflect the WHO (2014) definition for young people. Two papers were excluded due to recruitment of athlete populations. A total of seven articles therefore met the inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review. Of these studies, five used a cross-sectional design and two adopted a longitudinal design. No qualitative studies were identified that met the inclusion criteria. The study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Quality Assessment

The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) checklists for quantitative studies reporting correlations (NICE, 2012) and cohort studies (NICE, 2016) were used to determine the methodological quality of each study in the review. This process was conducted independently by the first author. These tools have been widely used in quality assessments (Jones et al., 2016; Scott et al., 2019). Each of the five cross-sectional studies was assessed against the NICE (2012) checklist criteria and received one of the following five ratings: (i) minimized risk of bias (++); (ii) may not have addressed all potential sources of bias (+); (iii) significant bias may persist (−); (iv) not reported; or (v) not applicable. The two longitudinal studies were assessed against the NICE (2016) risk of bias criteria and received a rating of either (i) yes; (ii) no; (iii) unclear; or (iv) N/A. Both quality assessment tools employ the following final rating guidelines to inform an overall risk of bias score: Good quality (++) was assigned if the study met all or most of the criteria; Reasonable quality (+) was assigned if the study met some criteria and it was deemed that any unmet criteria would not significantly alter the conclusions of the study; or Poor quality (−) was assigned if few or no criteria were met and conclusions would likely change. A summary of the criteria for each of the quality assessments is provided in Tables 2 and 3.

Results

Study Characteristics

All studies used self-report questionnaires. Three studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (UK), one in Australia, one in Italy, one in Lithuania and one in China. Included studies were published from 2004 to 2020, although most (n = 6) had been published since 2010. Sample sizes varied between the studies, ranging from 332 to 881 participants (median = 467). Six studies sampled both male and female participants and one study sampled exclusively female participants. Five studies recruited adolescent samples (i.e., aged 12 to 19; Goodwin et al., 2011, 2014; Jankauskiene et al., 2019; McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2004; White & Halliwell, 2010). Two studies reported a young person age range (i.e., aged 17 to 23; Costa et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2020). Two studies exclusively measured media influence (Jankauskiene et al., 2019; Yao et al., 2020), one study exclusively measured parent influence (Costa et al., 2016), one study exclusively measured peer influence (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2004) and three studies measured multiple sociocultural influences (Goodwin et al., 2011, 2014; White & Halliwell, 2010). Table 1 presents a summary of the studies included in this review.

Exercise Psychopathology Measures

Four standardized measures of exercise psychopathology were employed across the included studies (see Table 1). Two studies used the Compulsive Exercise Test (CET; Taranis et al., 2011); a 24-item self-report measure which assesses the core features of exercise psychopathology, including affect regulation, exercising for weight and shape reasons, and exercise rigidity. Two studies used the Exercise Dependence Scale (EDS; Hausenblas & Downs, 2002); a 21-item self-report questionnaire which assesses physical and psychological symptoms of exercise dependence. One study used the “exercising for weight control” subscale of the Exercise Dependence Questionnaire (EDQ; Ogden et al., 1997). The EDQ reflects the nature of exercise as being rigid and excessive, with perceptions of low control. One study used the Excessive Exercise Scale for Adolescents (EES-A; McCabe & Vincent, 2002), which examines importance, frequency and duration of exercise, as well as the compulsive need to exercise. All validated measures reflect symptoms of compulsive exercise, such as exercise rigidity and negative affect.

Jankauskiene et al. (2019) used a non-validated measure of exercise psychopathology and asked six questions on a five-point Likert scale, based on exercise behaviors that are not recommended by health professionals and can be detrimental to health (i.e., “I exercise as long as I can (more than 2 h)”). Test–retest reliability was reported as 0.89 for this measure.

Sociocultural Influence Measures

Five validated measures of sociocultural influence were used across the studies (see Table 1). These measures assessed either a single influencing factor (i.e., peers, family, media) or multiple influences. Two studies used the Perceived Sociocultural Pressure Scale (Stice & Bearman, 2001) to assess peer, family and media influences. Three studies used the Perceived Sociocultural Influences Questionnaire (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2001) to assess peer and family influences. One study used the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3 (Thompson et al., 2004), which measures internalization of body ideals endorsed by traditional media platforms, such as TV and magazines. One study assessed parental influence using the Parental Psychological Control Scale—Youth Self Report (Barber & Buehler, 1996). One study exclusively assessed peer relationships using the Same Sex and Opposite Sex Peer Relation Scale (Marsh, 1990).

Yao et al. (2020) used a non-validated measure to assess the frequency of selfie-taking behaviors (e.g., selfie-taking and selfie posting) for social networking sites, using five items each with a five-point Likert scale. Cronbach’s alpha was reported as 0.82 for this study.

Quality Assessment

All of the cross-sectional studies were rated as good quality (NICE, 2012). All five studies recruited populations relevant to the aims of the research and identified and controlled for confounding variables. Analytic methods were deemed appropriate for all studies and the results were considered internally valid, thus contributing to the studies’ overall quality. The full quality assessment for the cross-sectional studies is presented in Table 2.

Both prospective studies were rated as good quality (NICE, 2016). They adopted self-report questionnaires in their design. As a single cohort was used for both time points, risk of performance bias was rated as low for both studies. However, outcome data was not available for all participants, due to a small number of participants not completing the whole length of the study. While attrition rates across these studies ranged from 18 to 60%, both studies reported that there were no significant differences between variable scores of those that completed assessments at both times points and those that did not, thus reducing attrition bias. The full quality assessment for the prospective studies is presented in Table 3.

Potential Sociocultural Influences on Exercise Psychopathology

A synthesis of the findings from the studies included in this review is provided below. Studies were grouped according to sociocultural influence: (a) family influence; (b) peer influence; (c) media influence. One study examined the combined influence of parents, peers and media on compulsive exercise and will therefore be addressed separately.

Family Influences on Exercise Psychopathology

Three studies assessed family influences on compulsive exercise (cross-sectional: n = 2; prospective: n = 1). Of these studies, one exclusively assessed young males’ and females’ perceptions of parenting styles in relation to compulsive exercise (Costa et al., 2016) and two studies assessed the relationship between body-related messages from parents and compulsive exercise (Goodwin et al., 2011, 2014). In relation to parenting styles, higher perceived parental psychological control was associated with higher reported compulsive exercise attitudes and behaviors in young people, and maladaptive perfectionism mediated this relationship (Costa et al., 2016). Furthermore, both cross-sectional (Goodwin et al., 2011) and prospective research (Goodwin et al., 2014) identified a positive relationship between body-related messages from parents and compulsive exercise behaviors in adolescents. However, the delivery and receipt of body-related messages (i.e., comments made regarding body image) from parents were only significantly associated with increased compulsive exercise behaviors and attitudes in boys, not girls.

Peer Influences on Exercise Psychopathology

Three studies assessed peer influences on compulsive exercise (cross-sectional: n = 1; prospective: n = 2). Of these studies, two focused on the relationship between body-related messages from peers and compulsive exercise (Goodwin et al., 2011, 2014), and one study focused on the influence of body image comparisons with peers and compulsive exercise (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2004). Both cross-sectional and prospective research found that body-related messages from peers to be more muscular predicted elevated compulsive exercise behaviors and attitudes in boys, yet this was not found to be significant in girls (Goodwin et al., 2011, 2014). Further prospective research found that adolescent boys and girls who felt their body differed from their peers’ bodies were more at risk of engaging in compulsive exercise behaviors, however this relationship was less pronounced in boys (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2004).

Media Influence on Exercise Psychopathology

Media was assessed in four studies included in this review (cross-sectional: n = 3; prospective: n = 1). The type of media assessed in each study varied between TV and magazines (Goodwin et al., 2011, 2014; Jankauskiene et al., 2019) to social media platforms (Yao et al., 2020). Both cross-sectional (Goodwin et al., 2011; Jankauskiene et al., 2019) and longitudinal research (Goodwin et al., 2014) assessed the influences of traditional forms of media (e.g., TV and magazines) in relation to adolescents’ compulsive exercise. Cross-sectional research suggested that higher perceived pressure to conform to body ideals portrayed in traditional media was linked to higher levels of compulsive exercise in adolescent boys and girls (Jankauskiene et al., 2019), particularly when there was a perceived pressure from the media to be thin (Goodwin et al., 2011). However, longitudinal research found this pressure from the media to significantly predict compulsive exercise among adolescent girls not boys (Goodwin et al., 2014). For social media influence, cross-sectional research found a significant relationship between increased selfie-posting on social networking sites and increased maladaptive exercise behaviors (i.e., exercising for weight control) in young adult females (Yao et al., 2020). Body surveillance was found to be a partial mediator of this relationship, suggesting that the process of editing and posting “selfies” on social networking sites encourages body image monitoring in young females, which can therefore potentially impact on unhealthy exercise behaviors.

Sociocultural Model of Exercise Psychopathology

One study examined the combined impact of parents, peers and media on compulsive exercise and developed a sociocultural model of exercise psychopathology (White & Halliwell, 2010). This cross-sectional study found that the relationship between sociocultural pressures and a need for exercise was fully mediated by body image and appearance investment in both adolescent boys and girls. The mediator of body image disturbances in the relationship between sociocultural pressures and a need for exercise was stronger in adolescent girls than boys.

Discussion

While research has explored the impact of sociocultural influences on disordered eating in adolescents (Field et al., 2001), research is yet to systematically synthesize the evidence surrounding sociocultural influences on compulsive exercise in young people, meaning that the impact of sociocultural factors on potentially unhealthy compulsive exercise attitudes and behaviors in adolescents had not been considered. This is important given that adolescence is a crucial time for the development of exercise and eating-related attitudes, and adolescent exercise behaviors and attitudes become ingrained in adulthood. This systematic review therefore aimed to synthesize existing literature that explores sociocultural influences on compulsive exercise among young people aged 10–24 years, to enhance our understanding of the role that these sociocultural factors might play on compulsive exercise in this potentially vulnerable population. Overall, the studies included within this review provided evidence to suggest links between three distinct sociocultural factors: (a) family, (b) peers, and (c) media, with young people’s compulsive exercise attitudes and behaviors. The review highlighted the importance of individuals making unfavorable comparisons with body image ideals as a key underpinning factor for compulsive exercise in young people. Maladaptive perfectionism and body surveillance were significant mediators in the relationship between perceived or actual body-related pressure from others and increased compulsive exercise in young people. The findings also pointed towards gender differences in the impact of sociocultural influence on compulsive exercise in young people.

Parent Influence

Body-related messages from parents, and perceived psychological control from parents, were associated with higher compulsive exercise behaviors and attitudes in young people (Costa et al., 2016; Goodwin et al., 2011). Previous exploratory research has demonstrated that body-related messages from parents tend to reflect the body image ideals endorsed by parents, such that mothers and fathers typically encourage a slim physique in girls, while fathers encourage a muscular physique in boys (Thomas et al., 2014). The findings from this review move beyond this to suggest that if young people perceive parental control in relation to their body image, this can potentially impact on unhealthy weight control behaviors, such as compulsive exercise (Costa et al., 2016). While body-related messages from parents were found to only significantly predict compulsive exercise in boys, not girls (Goodwin et al., 2014), these findings were reflective of messages to be more muscular and evidence of this relationship is limited. As body types favored by young females are now often more reflective of an athletic and toned ideal (Bell et al., 2016), further research would be beneficial to explore whether it is the body-types favored by parents or the level of perceived control to exert these body types in their children that is associated with compulsive exercise attitudes and behaviors.

Peer Influence

Body image comparisons and body-related messages from peers were also associated with increased compulsive exercise behaviors and attitudes in young people. Social Comparison Theory (Festinger, 1954) states that individuals are most likely to compare their appearance and abilities to similar others (i.e., peers), and the findings in this review found peer comparisons to be evident in both adolescent males and females (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2004). Previous research found that social comparisons mediated the relationship between body-related messages from peers and a drive for muscularity in adolescent boys (Schaefer & Blodgett Salafia, 2014), yet the findings in this review expand on this and emphasize the way in which messages from peers to be more muscular can predict compulsive exercise in boys (Goodwin et al., 2011, 2014). While there was no evidence to suggest that body-related messages from peers predicted compulsive exercise in young females, body comparisons with peers were a significant predictor of compulsive exercise in girls (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2004). However, it is acknowledged that only a small number of studies have investigated this area, and further research is required to explore friendship dynamics in more detail and to unpack the mechanisms that may link these with maladaptive body change strategies, such as compulsive exercise, in adolescent boys and girls. While body-related messages and social comparisons with body ideals are evidently crucial in relation to compulsive exercise, it is difficult to determine whether these findings are fully representative of the sociocultural pressures that young people experience and which impact upon exercise attitudes and behaviors. Qualitative research is necessary to further understand the relative importance that young people place on these sociocultural influences in informing their exercise behaviors and attitudes.

Media Influence

Perceived pressure to conform to body ideals presented in the media was also a significant predictor of compulsive exercise in adolescents (Goodwin et al., 2011; Jankauskiene et al., 2019). However, these findings were only reflective of traditional forms of media (e.g., TV and magazines). Social media use is prevalent among adolescents (Coyne et al., 2019) and adolescents are increasingly accessing image-based social media platforms, such as Instagram and Snapchat, as a means of communicating with peers and new people (Pew Research Center, 2018). One study in this review highlighted body-surveillance as a mediator in the relationship between selfie-posting and increased compulsive exercise in young adult females (Yao et al., 2020), suggesting that young females can feel pressure to convey a certain appearance on social media posts. As recent research has highlighted a relationship between social media use and disordered eating behaviors in adolescents (Wilksch et al., 2020), further exploratory research may be important in understanding how peer interactions occurring on social media, and the internalization of body ideals seen online, may contribute to compulsive exercise behaviors and attitudes at this age.

Implications

This systematic review synthesized evidence on the relationship between sociocultural influences and compulsive exercise behaviors and attitudes in young people. The review indicates that compulsive exercise is associated with a multitude of sociocultural factors in young people and highlights the need for in-depth exploration into the mechanisms by which sociocultural factors can impact the development and maintenance of compulsive exercise in this group. This is particularly critical for informing eating and exercise-related interventions. Sociocultural factors have been linked to increased eating disorder symptomatology (Pedersen et al., 2018) and, as engaging in compulsive exercise has been found to prolong treatment of eating disorders and increase the chance of relapse (Solenberger, 2001), interventions that incorporate sociocultural factors (e.g., parents) in the treatment of eating disorders (Rosello et al., 2021) must also consider the sociocultural nature of compulsive exercise. Exercise-related interventions with young people have also been found to incorporate sociocultural factors (e.g., parents, peers) as a means to encourage exercise behaviors in young people (Ha et al., 2019). It is therefore crucial that those who are developing intervention strategies to promote physical activity or exercise understand the way in which sociocultural factors could impact unhealthy exercise behaviors and attitudes at this age.

Strengths and Limitations

This systematic review adhered strictly to the PRISMA guidelines. The methodological quality of each study was thoroughly assessed using established quality checklists (NICE, 2012, 2016) and the studies were all found to be of good quality. However, this systematic review is not without its limitations. When searching for eligible articles, studies were required to include a clear measure of exercise psychopathology to ensure that clear relationships could be identified between compulsive exercise and relevant sociocultural factors. This approach, however, might have limited the opportunity to identify any qualitative research, and this is an important focus for future reviews in this area to provide additional in-depth insights into the nature and potential mechanisms of sociocultural influences on compulsive exercise. Differences in exercise psychopathology terminology were also evident, such that some studies included in the review referred to exercise psychopathology as “exercise dependence” (n = 3), yet others used the term “compulsive exercise” (n = 2). However, it is important to note that inconsistencies in definitions and terminology do exist (Lichtenstein et al., 2017).

There are also some limitations to this review based on the inclusion criteria. To be included in this review, studies were required to report a “young people” age range reflective of the WHO (2014) definition of 10–24 years. Numerous studies were therefore excluded as the age range of participants was either not reported (n = 9) or because some participants in the study were over the age of 24 years (n = 10). This highlights the need for future researchers to take into consideration participant ages when aiming to recruit a sample of young people and to ensure that ages are clearly and fully reported. Use of more focused age-ranges would be valuable in future research as it would enable us to gain a clearer understanding of the developmental issues that can potentially contribute to the onset of unhealthy eating and exercise behaviors. Intervention and prevention strategies for unhealthy eating and exercise behaviors can also be adapted, based on more age-focused research, to ensure they are developmentally appropriate. It is noteworthy that the results from these 19 excluded studies reported similar mechanisms in the relationship between sociocultural influences on compulsive exercise, such as unfavorable comparisons with, and pressure to conform to, body ideals. Some excluded studies, however, highlighted the importance of goal setting on fitness tracking technology and internalization of body related content on social media (i.e., fitspiration) as being associated with increased compulsive exercise (Blackstone & Herrmann, 2020; Raggatt et al., 2018). It is therefore crucial that future research remains up to date with changing technological influences on compulsive exercise behaviors and attitudes in young people and explores the potential impact of fitness devices and social media on exercise behaviors specifically in adolescents.

Implications for Future Research

The outcomes of this review have highlighted the impact that sociocultural factors can have on the development and maintenance of compulsive exercise in young people. The findings suggest that social comparisons and internalization of body ideals are critical factors in the relationship between sociocultural factors with compulsive exercise; however, it is evident that this is a very under-researched area and further research is required with adolescent samples to fully explore the mechanisms that underpin the relationship between sociocultural influences and compulsive exercise at this age. As compulsive exercise is associated with serious health-related issues, such as disordered eating and poor quality of life, understanding the mechanisms by which compulsive exercise develops is important for identifying potential prevention strategies for unhealthy eating and exercise behaviors, before these unhealthy behaviors become ingrained. The findings from this review can therefore begin to inform the development of interventions for adolescents that target sociocultural influences on body image concerns and be used to ensure that these interventions address a multitude of sociocultural influences that can not only impact upon eating behaviors and body image concerns, but also compulsive exercise.

Conclusion

Compulsive exercise is known to commonly coexist with eating psychopathology. While the significance of sociocultural influences on eating disturbances among young people is well established, research is yet to systematically synthesize the evidence surrounding sociocultural influences on compulsive exercise in this age group. This systematic review aimed to synthesize and critically evaluate studies that assessed sociocultural influences on compulsive exercise in young people. The findings highlighted the role that family, peers and media provide in relation to compulsive exercise, and pointed towards the way in which social comparisons, body-related messages and pressure to conform to body ideals can predict this relationship. Gender differences in the findings were evident, suggesting that the influence of sociocultural factors on compulsive exercise may differ between males and females. However, while this review’s findings are illuminating, research in this area is limited and more research is required to understand the temporal relationships between sociocultural influences and compulsive exercise in young people. Further research on technological influences on compulsive exercise is also required, as existing research with adolescents is limited. Future studies will benefit from exploratory and prospective research designs to provide a deeper understanding of how and why these relationships exist, and how sociocultural factors influence the development and maintenance of compulsive exercise prior to adulthood.

References

Barber, B. K., & Buehler, C. (1996). Family cohesion and enmeshment: Different constructs, different effects. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58(2), 433. https://doi.org/10.2307/353507

Bell, H. S., Donovan, C. L., & Ramme, R. (2016). Is athletic really ideal? An examination of the mediating role of body dissatisfaction in predicting disordered eating and compulsive exercise. Eating Behaviors, 21, 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.12.012

Berge, J. M., MacLehose, R., Loth, K. A., Eisenberg, M., Bucchianeri, M. M., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2013). Parent conversations about healthful eating and weight: Associations with adolescent disordered eating behaviors. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(8), 746–753. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAPEDIATRICS.2013.78

Blackstone, S. R., & Herrmann, L. K. (2020). Fitness wearables and exercise dependence in college women: Considerations for University Health Education Specialists. American Journal of Health Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2020.1767004

Blakemore, S. J., & Mills, K. L. (2014). Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115202

Brown, V. L., Trevino, R. A., Richard, A. J., Bell, D. C., Montoya, I. D., & Brown, H. S. (2007). An analysis of peer influence and peer selection on human immunodeficiency virus risk behaviors. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 9(3), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9861.2004.tb00097.x

Christofaro, D. G. D., Andersen, L. B., de Andrade, S. M., de Barros, M. V. G., Saraiva, B. T. C., Fernandes, R. A., & Ritti-Dias, R. M. (2018). Adolescents’ physical activity is associated with previous and current physical activity practice by their parents. Jornal De Pediatria, 94(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPED.2017.01.007

Costa, S., Hausenblas, H. A., Oliva, P., Cuzzocrea, F., & Larcan, R. (2016). Maladaptive perfectionism as mediator among psychological control, eating disorders, and exercise dependence symptoms in habitual exerciser. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.004

Coyne, S. M., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Holmgren, H. G., & Stockdale, L. A. (2019). Instagrowth: A longitudinal growth mixture model of social media time use across adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29(4), 897–907. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12424

Davison, K. K., & Jago, R. (2009). Change in parent and peer support across ages 9 to 15 yr and adolescent girls’ physical activity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 41(9), 1816–1825. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a278e2

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Field, A. E., Camargo, C. A., Taylor, C. B., Berkey, C. S., Roberts, S. B., & Colditz, G. A. (2001). Peer, parent, and media influences on the development of weight concerns and frequent dieting among preadolescent and adolescent girls and boys. Pediatrics, 107(1), 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.107.1.54

Fitzgerald, A., Fitzgerald, N., & Aherne, C. (2012). Do peers matter? A review of peer and/or friends’ influence on physical activity among American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 35(4), 941–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.01.002

Goodwin, H., Haycraft, E., & Meyer, C. (2011). Sociocultural correlates of compulsive exercise: Is the environment important in fostering a compulsivity towards exercise among adolescents? Body Image, 8(4), 390–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.05.006

Goodwin, H., Haycraft, E., & Meyer, C. (2012). The relationship between compulsive exercise and emotion regulation in adolescents. British Journal of Health Psychology, 17(4), 699–710. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02066.x

Goodwin, H., Haycraft, E., & Meyer, C. (2014). Sociocultural risk factors for compulsive exercise: A prospective study of adolescents. European Eating Disorders Review, 22(5), 360–365. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2309

Goodyear, V., Wood, G., Skinner, B., & Thompson, J. (2021). The effect of social media interventions on physical activity and dietary behaviours in young people and adults: A systematic review. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12966-021-01138-3

Ha, A. S., Ng, J. Y. Y., Lonsdale, C., Lubans, D. R., & Ng, F. F. (2019). Promoting physical activity in children through family-based intervention: Protocol of the “Active 1 + FUN” randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6537-3

Halliwell, E., & Harvey, M. (2006). Examination of a sociocultural model of disordered eating among male and female adolescents. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11(2), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910705X39214

Hamel, A. E., Zaitsoff, S. L., Taylor, A., Menna, R., & le Grange, D. (2012). Body-related social comparison and disordered eating among adolescent females with an eating disorder, depressive disorder, and healthy controls. Nutrients, 4(9), 1260–1272. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu4091260

Hart, L. M., Cornell, C., Damiano, S. R., & Paxton, S. J. (2015). Parents and prevention: A systematic review of interventions involving parents that aim to prevent body dissatisfaction or eating disorders. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(2), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22284

Hausenblas, H. A., & Downs, D. S. (2002). How much is too much? The development and validation of the exercise dependence scale. Psychology and Health, 17(4), 387–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/0887044022000004894

Jankauskiene, R., Baceviciene, M., Pajaujiene, S., & Badau, D. (2019). Are adolescent body image concerns associated with health-compromising physical activity behaviours? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071225

Jones, B. A., Haycraft, E., Murjan, S., & Arcelus, J. (2016). Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in trans people: A systematic review of the literature. International Review of Psychiatry, 28, 81–94. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1089217

Kierans, J., & Swords, L. (2016). Exploring the appearance culture in early adolescence: A qualitative focus group approach in the Republic of Ireland (ROI). Journal of Adolescent Research, 31(6), 671–699. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558415604219

King, K. A., Tergerson, J. L., & Wilson, B. R. (2008). Effect of social support on adolescents’ perceptions of and engagement in physical activity. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 5(3), 374–384. https://doi.org/10.1123/JPAH.5.3.374

Levallius, J., Collin, C., & Birgegård, A. (2017). Now you see it, Now you don’t: Compulsive exercise in adolescents with an eating disorder. Journal of Eating Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1186/S40337-016-0129-8

Lichtenstein, M. B., Hinze, C. J., Emborg, B., Thomsen, F., & Hemmingsen, S. D. (2017). Compulsive exercise: Links, risks and challenges faced. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 10, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s113093

Lubans, D., Richards, J., Hillman, C., Faulkner, G., Beauchamp, M., Nilsson, M., … Biddle, S. (2016). Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: A systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics, 138(3).

Marsh, H. W. (1990). Self-description questionnaire-II. University of Western Sydney.

McCabe, M. P., & Ricciardelli, L. A. (2001). The structure of the perceived sociocultural influences on body image and body change questionnaire. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 8(1), 19–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327558IJBM0801_02

McCabe, M. P., & Ricciardelli, L. A. (2004). A longitudinal study of pubertal timing and extreme body change behaviors among adolescent boys and girls. Adolescence, 39(153), 145–166.

McCabe, M. P., & Vincent, M. A. (2002). Development of body modification and excessive exercise scales for adolescents. Assessment, 9(2), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/10791102009002003

Meyer, C., Taranis, L., Goodwin, H., & Haycraft, E. (2011). Compulsive exercise and eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 19(3), 174–189. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1122

Mond, J. M., & Calogero, R. M. (2009). Excessive exercise in eating disorder patients and in healthy women. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43(3), 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670802653323

Mond, J. M., Hay, P. J., Rodgers, B., & Owen, C. (2006). An update on the definition of “excessive exercise” in eating disorders research. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39(2), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20214

NICE. (2012). Quality appraisal checklist: Quantitative studies reporting correlations and associations. Retrieved January 5, 2021, from https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/appendix-g-quality-appraisal-checklist-quantitative-studies-reporting-correlations-and#checklist

NICE. (2016). Methodology checklist: Cohort studies. Retrieved January 5, 2021, from https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg10/chapter/appendix-d-methodology-checklist-cohort-studies

Ogden, J., Veale, D., & Summers, Z. (1997). The development and validation of the exercise dependence questionnaire. Addiction Research and Theory, 5(4), 343–355. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359709004348

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J., Bossuyt, P., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T., Mulrow, C., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ, 372(71). https://doi.org/10.31222/OSF.IO/V7GM2

Patton, G. C., Sawyer, S. M., Santelli, J. S., Ross, D. A., Afifi, R., Allen, N. B., … Viner, R. M. (2016). Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. The Lancet, 387(10036), 2423–2478. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1

Pedersen, L., Hicks, R. E., & Rosenrauch, S. (2018). Sociocultural pressure as a mediator of eating disorder symptoms in a non-clinical Australian sample. Cogent Psychology, 5(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2018.1523347

Pew Research Center. (2018). Teens, social media & technology. Retrieved February 19, 2020, from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

Plateau, C. R., Shanmugam, V., Duckham, R. L., Goodwin, H., Jowett, S., Brooke-Wavell, K. S. F., … Meyer, C. (2014). Use of the compulsive exercise test with athletes: Norms and links with eating psychopathology. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 26(3), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2013.867911

Quiles Marcos, Y., Quiles Sebastián, M. J., Pamies Aubalat, L., Botella Ausina, J., & Treasure, J. (2013). Peer and family influence in eating disorders: A meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 28(4), 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2012.03.005

Raggatt, M., Wright, C. J. C., Carrotte, E., Jenkinson, R., Mulgrew, K., Prichard, I., & Lim, M. S. C. (2018). “i aspire to look and feel healthy like the posts convey”: Engagement with fitness inspiration on social media and perceptions of its influence on health and wellbeing. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5930-7

Ricciardelli, L. A., & McCabe, M. P. (2002). Children’s body image concerns and eating disturbance. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(3), 325–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00051-3

Rideout, V. (2016). Measuring time spent with media: The Common Sense census of media use by US 8- to 18-year-olds. Journal of Children and Media, 10(1), 138–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2016.1129808

Rodgers, R. F., & Chabrol, H. (2009). Parental attitudes, body image disturbance and disordered eating amongst adolescents and young adults: A review. European Eating Disorders Review, 17(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.907

Rodgers, R. F., Paxton, S. J., & Chabrol, H. (2010). Depression as a moderator of sociocultural influences on eating disorder symptoms in adolescent females and males. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(4), 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9431-y

Rosello, R., Gledhill, J., Yi, I., Watkins, B., Harvey, L., Hosking, A., … Nicholls, D. (2021). Early intervention in child and adolescent eating disorders: The role of a parenting group. European Eating Disorders Review, 29(3), 519–526. https://doi.org/10.1002/ERV.2798

Schaefer, L. M., Burke, N. L., Thompson, J. K., Dedrick, R. F., Heinberg, L. J., Calogero, R. M., … Swami, V. (2015). Development and validation of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4). Psychological Assessment, 27(1), 54–67.https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037917

Schaefer, M., & Blodgett Salafia, E. H. (2014). The connection of teasing by parents, siblings, and peers with girls’ body dissatisfaction and boys’ drive for muscularity: The role of social comparison as a mediator. Eating Behaviors, 15(4), 599–608.

Scott, C. L., Haycraft, E., & Plateau, C. R. (2019). Teammate influences on the eating attitudes and behaviours of athletes: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 43, 183–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.02.006

Solenberger, S. E. (2001). Exercise and eating disorders: A 3-year inpatient hospital record analysis. Eating Behaviors, 2(2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1471-0153(01)00026-5

Stice, E., & Bearman, S. K. (2001). Body-image and eating disturbances prospectively predict increases in depressive symptoms in adolescent girls: A growth curve analysis. Developmental Psychology, 37(5), 597–607. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.37.5.597

Taranis, L., Touyz, S., & Meyer, C. (2011). Disordered eating and exercise: Development and preliminary validation of the compulsive exercise test (CET). European Eating Disorders Review, 19(3), 256–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.1108

Taveras, E. M., Rifas-Shiman, S. L., Field, A. E., Frazier, A. L., Colditz, G. A., & Gillman, M. W. (2004). The influence of wanting to look like media figures on adolescent physical activity. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.005

Thomas, S. L., Olds, T., Pettigrew, S., Randle, M., & Lewis, S. (2014). “Don’t eat that, you’ll get fat!” exploring how parents and children conceptualise and frame messages about the causes and consequences of obesity. Social Science and Medicine, 119, 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.024

Thompson, J. K., van den Berg, P., Roehrig, M., Guarda, A. S., & Heinberg, L. J. (2004). Development and validation of the sociocultural attitudes towards appearance questionnaire. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 17(3), 293–304.

Uhlmann, L. R., Donovan, C. L., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Bell, H. S., & Ramme, R. A. (2018). The fit beauty ideal: A healthy alternative to thinness or a wolf in sheep’s clothing? Body Image, 25, 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.01.005

White, J., & Halliwell, E. (2010). Examination of a sociocultural model of excessive exercise among male and female adolescents. Body Image, 7(3), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.02.002

Wilksch, S. M., O’Shea, A., Ho, P., Byrne, S., & Wade, T. D. (2020). The relationship between social media use and disordered eating in young adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(1), 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23198

World Health Organization. (2014). Adolescence: A period needing special attention—Recognizing-adolescence. Retrieved November 14, 2019, from http://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/section2/page1/recognizing-adolescence.html

Yao, L., Niu, G., Sun, X., Duan, C., & Zheng, Y. (2020). Selfie-posting on social networking sites, body surveillance, and exercise for weight control among Chinese young women with low body mass index. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101767

Young, S., Touyz, S., Meyer, C., Arcelus, J., Rhodes, P., Madden, S., … Hay, P. (2018). Relationships between compulsive exercise, quality of life, psychological distress and motivation to change in adults with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-018-0188-0

Zach, S., Zeev, A., Dunsky, A., Goldbourt, U., Shimony, T., Goldsmith, R., & Netz, Y. (2013). Perceived body size versus healthy body size and physical activity among adolescents - Results of a national survey. European Journal of Sport Science, 13(6), 723–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2013.771382

Acknowledgements

The first author was awarded a PhD studentship by the School of Sport, Exercise and Health Sciences at Loughborough University, UK.

Funding

Kalli A. Reynolds is funded by a PhD studentship awarded by the School of Sport, Exercise and Health Sciences at Loughborough University, UK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report none.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

A flowchart to represent the broad search strategy for all databases used.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reynolds, K.A., Plateau, C.R. & Haycraft, E. Sociocultural Influences on Compulsive Exercise in Young People: A Systematic Review. Adolescent Res Rev 8, 179–194 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-022-00180-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-022-00180-x