Abstract

This paper studies the interplay between central and local governments in defining the optimal degree of decentralization in terms of public goods supply. The choice between full centralization and asymmetric decentralization implies a trade-off between the possibility to provide public goods at a lower cost, wherever this is possible by decentralizing, and the possibility to fully internalize spillovers by full centralization. We find that asymmetric decentralization introduces distortions into the public decision-making process. We also demonstrate that the power to interfere in the central government’s ruling mechanisms should be reduced for the jurisdictions that have decentralized, in order to make their decentralization choice convenient even for the citizens in the less efficient jurisdictions. Finally, we find the conditions under which asymmetric decentralization can be simultaneously advantageous for both rich and poor regions through the design of appropriate equalization transfers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

According to the traditional literature on federalism (Oates 1972), the choice between decentralization and centralization depends on the trade-off between the internalization of inter-jurisdictional spillovers (doing better by a national government) and the local information advantages (exploiting better by a sub-national government). However, with the second-generation theory of federalism more attention has been paid to the fiscal and political incentives facing sub-national policy-makers (Oates 2005; Weingast 2009). This would also affect the above mentioned trade-off and, in particular, the intergovernmental relationship between the centre and the local units.

More generally, the decision to allocate policy jurisdictions to different levels of government is related to a number of trade-offs between the advantages and disadvantages of centralized versus decentralized provision (Tommasi and Weinschelbaum 2007). For instance, the central government could discriminate unfairly between regions and choose to favour one region for political reasons (e.g., that with the top-ranking member of government comes from), thus justifying an institutional reform towards decentralization (Zantman 2002). In a similar fashion, the allocation of responsibility could differ systematically across local entities (or states) as it would never be optimal to allocate such responsibility uniformly among all of them (Jack 2004). Put differently, in some states/regions the responsibility, combined with the autonomy, for services delivery should rest, for instance, with the central government, while in other states/regions it should reside with the state/regional government. Moreover, when income differs substantially across regions, centralization could be not always efficient as regional specificities may prevail leading to forms of partial fiscal federalism (Cerniglia et al. 2019). Overall, this could give rise to some new institutional settings, characterized by asymmetric degrees of decentralization due to the attitude/intention of either the central or the regional government. In fact, if one looks at some recent cross-country experiences, this seems to be the case.

For example, in Italy after the constitutional reform in 2001, the article 116 (third paragraph) of the Constitution introduces the possibility for Italian regions to request the attribution of additional forms and particular conditions of autonomy. This differentiated autonomy can be attributed at the claim of the region concerned, after consultation with the local authorities, with a state law approved by an absolute majority of the members, on the basis of agreement between the State and the Region concerned (Eupolis 2017; Zanardi 2017). In recent years, the request for greater autonomy has been put forward by nine regions (Lombardy, Veneto, Emilia-Romagna, Piedmont, Liguria, Tuscany, Marche, Umbria and Campania) and in two of them, i.e. Lombardy and Veneto, a referendum was held in 2017, which confirmed such request by citizens, anticipating the negotiations with the central government. By contrast, Emilia–Romagna directly committed the Governor of the Region to start negotiations with the State in the same year (Rizzo and Secomandi 2019).

In Spain, once the constitutional process was accomplished, 17 autonomous communities emerged and a highly asymmetric quasi-federal system was the outcome (Keating 2000; Flynn 2004). This was mostly due to the increasing leverage acquired by the Catalan, Basque and a few other, autonomous governments at the negotiating table (Conversi 2007).Footnote 1

In some cases, the sub-national autonomy is, however, less related to fiscal decentralization and much more to regulatory decentralization as in the Russian institutional system (Libman and Rochlitz 2019), where the Russian regions systematically passed laws and legal acts that often explicitly contradicted federal regulations, leading to a “war of laws” (Lapidus 1999; Libman 2010). In this context, some regions managed to negotiate a higher level of autonomy from the center on a bilateral basis, leading to a highly asymmetrical design of Russian federalism (Hughes 2001; Martinez-Vazquez 2007).

Finally, in other cases the central control has never declined to a level that allowed a comparable level of institutional variation at the sub-national level such as in China (Libman and Rochlitz 2019). For instance, under Mao China’s destiny was very much decided by what happened at the center, with the autonomy of regional and local states remaining extremely limited. However, Chinese sub-national governments gained over time a residual claim on revenues, which allows them to retain some of the resources generated in the region. This contributes to explain why Chinese regions feature higher growth incentives for regional officials. More generally, Chinese provinces enjoy a significant level of autonomy with respect to economic policy, which is why China can be seen as a de facto federation, although de jure the country is a unitary state.

Those different countries’ experiences seem to suggest that asymmetric arrangements within the decentralization architecture are more frequent and, in some cases, more accommodative, durable and practical, being also more flexible and effective in managing and preventing intergovernmental conflict (MacGarry 2001; Coakley 2004; Conversi 2007). Put differently, for the most part asymmetric decentralization within modern states could reflect agreements and the result of a voluntary exchange between regional and central governments, rather than wars of conquest or threats of secession, to manage successfully multilevel governance (Congleton et al. 2003; Congleton 2006).

However, some side effects and distortions may arise when asymmetric forms of decentralization take place within a single country, especially in terms of free-riding attitude by some regions that call for some corrective action from the centre. Recalling the theory of public choice from its origins (Buchanan and Tullock 1962; Tollison and Buchanan 1972), we could say that a State functioning could be adversely affected by the presence of too many special interests (usually causing an excessive growth in public spending).

In this paper, we try to shed some light on this issue starting with a default scenario characterized by an entirely centralized supply of a local public good. However, local governments may require the decentralization of this supply. In particular, we focus on the case in which decentralization occurs asymmetrically. Asymmetric decentralization can take place for different reasons. For example, because the citizens have different preferences at the local level, or because some local governments are in a better position concerning their cost structrure, i.e. they can provide the public good at lower costs than the central government. The latter case is discussed in our study. Thus, if asymmetric decentralization is possible only for the most efficient local governments, the provision of local public policies in less efficient jurisdictions will remain a central government’s responsibility.

The tax base used to finance the public policies in the territories that have obtained decentralization will be separated from the central budget. In this context, we study the spillover effects generated by asymmetric decentralization and the free-riding incentives introduced by the former. The choice between full centralization and asymmetric decentralization implies a trade-off between the possibility to produce at a lower cost, wherever this is possible by decentralizing, and the possibility to fully internalize spillovers by full centralization. In this framework, understanding how and to what extent asymmetric decentralization can improve welfare is not a trivial task.

Furthermore, we claim that asymmetric decentralization introduces distortions in the public decision-making process, whose consequences require an adequate understanding for both governments and voters. The jurisdictions that obtain decentralization can decide their public goods supply and, at the same time, they contribute to define public policies that the central government will implement in the other non-decentralized regions. We demonstrate that the power to interfere in the central government’s decision-making process should be reduced for the jurisdictions that have decentralized in order to make their decentralization choice convenient even for the citizens in the less efficient jurisdictions.

Finally, to enrich the analysis and make it closer to the real-world experience, we relax the assumption of no inter-regional differences in the per capita income, also including an equalization transfer mechanism. Accordingly, we are able to analyse the regional disparities in the level economic development as one of the main arguments that has traditionally contributed to explain the local demand for greater autonomy (Mangiameli et al. 2020). This extension complements the assumption of territorial specific costs (e.g., due to morphology, urban concentration, and other exogenous factors), which are independent of the governments’ quality and institutional responsibility of public goods provision. In fact, the choice between, for instance, full centralization and asymmetric decentralization might be also determined by the existence of inter-regional income disparities that call for inter-regional fiscal flows, which can play an important role in this story. Looking at some countries’ experience (e.g., Belgium, United Kingdom, Spain, Canada, Germany), it can be noted that even though some forms of territorial gap exist—between the North and the South; the East and the West—, the institutional asymmetry did not worsen the regional divide as it has been complemented by equalization tools that made that divide less severe. This paper finds the conditions under which asymmetric decentralization can be simultaneously advantageous for both rich and poor regions through the design of appropriate equalization transfers.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 develops the economic framework. Sections 3 to 5 study equilibrium polices under full centralization, full decentralization and asymmetric decentralization, respectively. Section 6 shows the welfare implications in the different institutional settings. Section 7 discusses the role of veto power in the decision to decentralize, while Sect. 8 provides an extension of the baseline model including income heterogeneity among regions. Finally, Sect. 9 concludes. The Appendix contains derivations and proofs of the propositions.

2 The economy

We use a framework similar to that of Besley and Coate (2003) and Giuranno (2009, 2010). In detail, we consider two equal sized jurisdictions comprising a federation and normalize to one the population of each jurisdiction. In the economy two kinds of goods are considered: a public one, g, and a private one, y; the former refers to some public provision aimed at fulfilling collective interest (e.g., control of environmental pollution), while the latter represents the personal income to be consumed for private purposes as well as to finance the public good.

Citizens are all alike; that is, they are endowed with the same income and have the same taste \(\lambda\) regarding the public good. The parameter \(\lambda >0\) tells us how much citizens value g with respect to y.

Citizens vote in order to elect their delegates to act either in the central government or in the regional government. Since citizens are all alike, any of them can represent the constituency. The preferences \(u_{i}\) of the representative of jurisdiction i are given by the following equation:

The parameter \(k\in \left[ 0,1/2\right]\) measures the degree of spillovers, which is the same for all citizens; when \(k=0\) citizens care only about the public good provided in their own jurisdiction, while when \(k=1/2\) they benefit equally about the public good in both jurisdictions (Besley and Coate 2003). The term \((1-t_{i})y\) denotes after tax income available for private consumption, where y is the pre-tax income and \(t_i\) is the tax rate in jurisdiction i. Note that the condition \(g_{i}\ge 1\) means that a minimal level of public good must be provided by default.

We assume that the cost of public good production is different if the public good is provided either by the central or the local governments. Such difference could be due to different administrative skills and knowledge between local and central officials, bureaucrats and policy-makers. Indeed, local government could better minimize political transaction costs by promoting, for instance, the transfer of certain services and maintaining in-house production for others (Williamson 1985). In this way, local officials can concentrate on potential productive and allocative efficiency gains, also better controlling performance and attending to service disruptions (Tavares and Camöes 2007). The opposite could also be true, that is local government’s action could be easily distorted by lobbyist pressures and even by the infiltration of organized crime (Ravenda et al. 2020). Such differences depend on the quality of institutions, thus when the spending allocation among levels of governments change also the costs of public good provision change.Footnote 2

In particular, we assume that \(0<c_{1}<c<c_{2}\), where \(c_{1}\), c and \(c_{2}\) are the unit costs of production in region 1, at the central level and in region 2, respectively. Hence, we define region 1 as the efficient one and region 2 as the inefficient one. Furthermore, we assume that c, \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are common knowledge.

Note that such cost structure includes the cases of different economies of scale. Indeed, if \(c<\frac{c_1+c_2}{2}\) we have economy of scale because of costs subadditivity; when \(c>\frac{c_1+c_2}{2}\), we have diseconomy of scale. There is no scale economy if \(c=\frac{c_1+c_2}{2}\); in this case, the unit cost of the central government is simply the average cost \(c=\frac{c_1+c_2}{2}\).Footnote 3

In what follows we consider three alternative scenarios: (1) the public good g is set by the central government under full centralization; (2) policy g is set under full decentralization; (3) policy g is set under asymmetric decentralization, where one jurisdiction can define policy g under decentralization, while the other jurisdiction cannot.

3 Policy determination under full centralization

We assume that under full centralization the central government adopts a uniform policy across jurisdictions; that is, \(g_{i}=g^{C}\). Furthermore, policy is chosen by negotiation under the threat that, in the case of disagreement, it cannot be set by regional governments.Footnote 4

The centralized budget is

The agreement utility is

While, the disagreement utility is \(y-c\), the income minus the cost for producing the minimum provision of public good.Footnote 5 Note that under centralization spillovers are fully internalized (Besley and Coate 2003).

We show the central government’s policy outcome as the solution of Nash bargaining between jurisdictional representatives; that is,

where, \(\phi =-c(g^{C}-1)+\lambda \ln g^{C}\ge 0\) is the net gain of each representative from reaching an agreement on policy \(g^{C}\). Note that a necessary condition for \(\phi \ge 0\) is that \(\lambda \ge c\); that is, equilibrium net gains are weakly positive when citizens value the public good highly enough. In the latter case, the default value \(g^{C}=1\) is suboptimal and an agreement on the supply of a \(g^{C}\ge 1\) is achieved.

Centralized policy outcome is

As a result, regardless of where citizens live, individual welfare under full centralization is

4 Policy determination under full decentralization

Under full decentralization, jurisdictions set policy at local level independently from each other and according to their budget constraint. The latter is given by

Decentralized Nash equilibrium is the solution to the following problem:

Solutions are:

Solution in Eq. 6 leads to the following Proposition.Footnote 6

Proposition 1

Under full decentralization, spillovers are not internalized. Furthermore, the jurisdiction that produces at a lower cost than the central government can compensate the loss due to the spillover through a lower production cost, while the jurisdiction with a higher production cost always provides a lower level of public good than that of the central government.

When we compare full decentralization with full centralization, we find that public goods provision is underprovided by an amount \(\left( 1-k\right)\) in both jurisdictions. Furthermore, the following relations hold: \(g_{2}^{D}< g^{C}\); \(g_{2}^{D}< g_{1}^{D}\); \(g_{1}^{D}\lesseqgtr g^{C}\); \(t_{1} ^{D}=t_{2}^{D}\le t^{C}\). Against a uniform tax rate, the inefficient jurisdiction will certainly reduce public good provision under decentralization. Instead, policy outcome in the efficient jurisdiction can be either higher or lower than that under full centralization. Thus, only the efficient jurisdiction can compensate the decentralized loss due to the spillover effect through a lower production cost. Clearly, the inefficient region prefers full centralization to full decentralization because it can benefit from both a lower cost and the internalized spillovers. While, the region that produces at a lower cost than the central government prefers to use its own technology, provided the gain of a lower cost, more than to compensate the loss due to not internalizing spillovers.

Furthermore, according to solution (Eq. 6), individual welfare under full decentralization is

5 Policy determination under asymmetric decentralization

In this section, we analyse the case of asymmetric decentralization. We assume that when a jurisdiction is more efficient then the central government in providing the public good it may obtain the power to set policy autonomously at the decentralized level.

Recalling that we have assumed that jurisdiction 1 is more efficient then the central government in the provision of the public good g, while jurisdiction 2 does not, only jurisdiction 1 will be able to obtain the decentralization of public good provision. In that case, policy is chosen and implemented at the decentralized level for jurisdiction 1 and at the centralized level for jurisdiction 2.

It should be noted that asymmetric decentralization is not a secession since there is no a complete separation from the federation and no region does leave the national state. Indeed, even the more efficient region has an incentive to remain and to bargain on the national decision-making process regarding public good provision in the other region as it is interested in the internalization of externalities.

First, we study the policy choice of jurisdiction 1 that can decentralize; that is, jurisdiction 1 sets \(g_{1}^{A}\) as follows:

that is,

The equilibrium policy of jurisdiction 1 is

Therefore, jurisdiction 1 sets policy at the decentralized level without internalizing the spillovers produced on the other jurisdiction. Furthermore, in equilibrium, jurisdiction 1 chooses exactly the same policy that it would choose under full decentralization, i.e. \(g_{1}^{A}=g_{1}^D\).

Instead, in jurisdiction 2 public good provision is chosen by bargaining at the central level between the representatives elected in the two jurisdictions. Since the central government’s budget constraint excludes the tax revenues collected in jurisdiction 1, it is given by

where, the centralized tax rate \(t^{A}=t_2^{A}\) is levied only on the tax base of the jurisdiction that has to receive the central government provision, since jurisdiction 1 uses its tax base for financing its own provision.

The agreement utility of the representative of jurisdiction 1 is

Under disagreement, the central government cannot provide the public good in jurisdiction 2 above the minimum guaranteed level, which is 1 by assumption. Therefore, the disagreement utility for the representative of jurisdiction 1 is given by

The net gain from reaching an agreement over public good provision in jurisdiction 2 must be weakly positive for the jurisdictional representatives. The net gain for the representative of jurisdiction 1 is

Note that \(\partial {\psi _{1}}/\partial {g_{2}^{A}}>0\); that is, the efficient jurisdiction is interested in the highest possible centralized provision in the inefficient jurisdiction in order to benefit from its spillover as much as possible.

Instead, for jurisdiction 2, the agreement utility is

Note that by maximizing Eq. (11) with respect to \(g_{2}^{A}\), we obtain the first best of jurisdiction 2 when policy is chosen by the central government by using its technology; that is,

Equation (12) can be seen as the utopia point of jurisdiction 2, which defines the maximum possible achievement of public good provision that jurisdiction 2 may reach in the bargaining situation. Thus, this amount in asymmetric decentralization (Eq. 12) is always higher than that provided under full decentralized (Eq. 6) and lower then that provided under full centralization (Eq. 4).

The disagreement utility for jurisdiction 2, which implies \(g_{2}^{A} =1\), is

The net gain for the representative of jurisdiction 2 is given by

It is worth studying policy outcome in the absence of spillovers (\(k=0\)) before focusing on the case where \(k\ne 0\). This allows us to define a benchmark result expressed in the following Proposition.

Proposition 2

In the absence of spillover (\(k=0\)), asymmetric decentralization generates the highest possible welfare for all jurisdictions.

When \(k=0\), the net gain (Eq. 10) of jurisdiction 1 from policy provision in jurisdiction 2 is null. This means that jurisdiction 1 is indifferent to the level of \(g_{2}^{A}\) decided by the central government. Therefore, jurisdiction 2, which has a positive net gain (Eq. 13) even when \(k=0\), will be able to obtain the preferred level of provision in the central government since jurisdiction 1 has no incentive to oppose. As a result, it is straightforward to verify that when \(k=0\) policy outcome in the two jurisdictions is given by \(g_{1}^{A}=\frac{\lambda }{c_{1}}\) and \(g_{2}^{A}=g_{2}^{FB}=\frac{\lambda }{c}\), where \(g_{1}^{A}>g_{2}^{A}\) since \(c_{1}<c\). Asymmetric decentralization is always weakly welfare improving for all jurisdictions since they can benefit from higher public good provision at lower costs. In detail, consider that the following relations hold when \(k=0\): \(g_{1}^{A}=g_{1}^{D}>g^{C}\); \(g_{2}^{A}=g^{C}>g_{2}^{D}\); \(u_{1}^{A}=u_{1}^{D}>u^{FC}\); \(u_{2}^{A}=u^{FC}>u_{2}^{D}\).

Now, we turn to the general case where \(k\ne 0\). In this scenario, it is useful to consider the determinants of net gain depending on the relation between \(g_2^A\) and \(g_2^{FB}\). Thus, after simple algebra, we rewrite Eq. 13 as follows:

We use Nash bargaining in order to solve the decision-making problem of the central government.

where, \(\theta\) and \(1-\theta\) are the political bargaining weights of region 1 and 2 respectively, with \(\theta \in \left[ 0,1\right]\).

The first order condition is

According to Eq. 15 it is straightforward to verify that \(g_2^A\ge g_2^{FB}\).

The equilibrium Eqs. (8) and (15) lead to the following Proposition.

Proposition 3

Under asymmetric decentralization, the following results emerge:

and

The proof of Proposition 3 is in the Appendix.

Asymmetric decentralization implies that the region that cannot decentralize is also not able to affect the policy determination in the region that can decentralize, i.e. \(\frac{dg_{1}^{A}}{d\theta }=0\). The reverse is not true, since the region that can decentralize is also able to influence the policy setting for the region that has to stay under the central government’s authority. Since region 1 is interested in the highest provision in region 2, then \(g_{2}^{A}\) increases as region’s 1 political influence \(\theta\) increases, i.e. \(\frac{dg_{2}^{A}}{d\theta }>0\).

Furthermore, as expected, public good provision increases in both regions as individual preference \(\lambda\) increases and decreases as spillover k increases. On the other hand, the higher the marginal cost of the central government, c, the lower the public good provision in region 2. Likewise, the higher the marginal cost of region 1, \(c_{1}\), the lower the public good provision in the same region.

The following Proposition compares public goods provision under the three different set-ups.

Proposition 4

Given the equilibria under full decentralization, full centralization and asymmetric decentralization, the following relations hold: \(g_{2}^{D}<g_{2}^{A}\le g^{C};g_{1}^{A}=g_{1}^D\gtreqless g^{C}\).

We have already shown that region 1 sets \(g_{1}^{A}=g_{1}^D\) and that such provision may be either higher or lower than the provision under full centralization. Such ambiguity is due to the fact the two forms of decentralization allow region 1 to use the most efficient technology, but without internalizing spillovers.

In order to compare the public provision of region 2 in the three settings, we should consider that centralized equilibrium policy is a compromise between the conflicting interests of the two jurisdictions. To see that, recall that region 1 is interested in the highest possible provision in region 2 in order to benefit from the related spillovers. As a result, citizens of region 2 end up spending more than their first best for the provision of the public good in their region. To realize that, consider that in equilibrium the following relations hold: \(\frac{d\psi _{2} }{dg_{2}^{A}}\equiv \frac{du_{2}^{A}}{dg_{2}^{A}} =-1+\frac{g_2^{FB}}{g_{2}^{A}}\le 0\); where the negative sign is a necessary condition for the existence of equilibrium.

Thus, a necessary condition for satisfying equilibrium Eq. (15) is that the provision of \(g_{2}^{A}\) is weakly higher than \(g_{2}^{FB}\), which is reported in Eq. (12). This, in turn, implies that, in equilibrium, the production in the inefficient region is always higher than the production under full decentralization; that is, \(g_{2}^{D}<g_{2}^{FB}\le g_{2}^{A}\le g^{C}\), where \(g_{2}^{FB} = g_{2}^{A} = g^{C}\) when \(k=0\), as shown in Proposition 2.Footnote 7

Moreover the inefficient provision \(g_2^A\) increases more than proportionally with respect to the first best utopia provision for region 2.

6 Welfare analysis for different local institutional settings

The following Proposition compares the welfare generated by full and asymmetric decentralization for the two regions.

Proposition 5

The efficient region prefers asymmetric decentralization to full decentralization. The inefficient region prefers asymmetric decentralization to full decentralization when \(\theta <{\overline{\theta }}\). Furthermore, the threshold needed to make full decentralization better off for jurisdiction 2 increases in \(c_{2}\).

The first part of Proposition 5 follows Proposition 4, hence \(k\ln g_{2}^{A} \ge k\ln g_2^{FB}+k\ln \frac{c}{c_{2}}\) is always true since \(\ln \frac{c}{c_{2}}<0\). The proof of the second part of Proposition 5 is in the Appendix.

Clearly, asymmetric decentralization allows region 1 not only to exploit its more efficient technology but also to internalize positive spillovers generated in region 2. On the contrary, region 2 would get the same spillover from region 1, either with full or asymmetric decentralization, without having the possibility to internalize the spillover produced by the region 1.

Instead, the advantage of asymmetric decentralization for region 2 with respect to full decentralization comes from the possibility to use central technology that is more efficient. For sufficiently high values of production cost and bargaining power, also the inefficient region prefers asymmetric decentralization.

The following Proposition compares the welfare generated by asymmetric decentralization and full centralization for the efficient region. While, the welfare analysis for region 2 is presented in the next section.

Proposition 6

When \(k=0\), the efficient region prefers asymmetric decentralization to full centralization. Instead, when \(k>0\), it is more likely to prefer asymmetric decentralization either the higher the efficiency ratio \(\left(\frac{c}{c_1}\right)\) is or the higher the provision of public good in the inefficient region \(g_2^A\) is.

The proof of Proposition 6 is in the Appendix.

According to Proposition 4 (\(g_2^D<g_2^{A}\le g^{C}\)), only with full centralization region 1 can completely internalize the spillover. For region 1, asymmetric decentralization is more convenient than full centralization either if the central government’s cost is sufficiently higher than the cost of the efficient region or if the bargaining power of region 1 is sufficiently high. In fact, the higher is the bargaining power of region 1, the higher is the public good provision in region 2.

Asymmetric decentralization in favour of a single region may have either positive or negative effects for the other region. For this reason, the opinion of the non-decentralized jurisdiction should also be taken into account during the decision-making process. In the following section, we analyse the role of veto power that the inefficient jurisdiction might exert when jurisdiction 1 asks to asymmetrically decentralize local public policy.

7 Asymmetric decentralization and veto power

We assume that full centralization is the status quo. In this context, the efficient jurisdiction asks for asymmetrical decentralization concerning the public good provision, while the inefficient one has a veto power on this choice. In the case where negotiation about such request takes place between the representatives of the two jurisdictions, the representative of jurisdiction 2 uses its veto power against the asymmetric decentralization of public good provision in jurisdiction 1 if the following propositions hold.

Proposition 7

It is more likely that the inefficient region uses its veto power against the asymmetric decentralization setting for region 1 if the production cost of the efficient jurisdiction is not sufficiently smaller than that of the central government.

The proof of Proposition 7 is in the Appendix.

An underling assumption for the previous Proposition to hold is that the costs of production in jurisdictions 1 and 2 and that of the central government are common knowledge. If the production cost of region 1 is not sufficiently smaller than the cost of the central government, asymmetric decentralization cannot be convenient for region 2. The reason is that, for a given magnitude of the spillover, the loss due to the lack of spillover internalization could not be sufficiently compensated by the efficiency gain guaranteed by region 1. In order to explain that, consider the equilibrium policy in Eq. 8: the lower \(c_1\), the higher \(g_1^A\). Consequently, a higher efficiency in region 1 leads to both a higher public good provision in region 1 and a higher spillover in favour of region 2. This means that region 2 finds convenient to let region 1 decentralize when region 1 is highly efficient since a higher efficiency leads to a higher spillover to be exploited. Moreover, region 2 can use a more efficient technology when producing public goods at the central level.

A key element that may either facilitate or, on the contrary, make the asymmetric decentralization process more difficult concerns the distribution of the decision-making power at the centralized level of government that, after the asymmetric decentralization has been decided, remains in charge of the public provision in region 2. Thus, if region 2 has the possibility to exert a veto power about the asymmetric decentralization request of region 1, the decision-making weight of region 2 at the centralized level, after the request of region 1 has been accepted, plays a role in winning the consent of region 2.

The following Proposition clarifies the role of the bargaining power in the centralized legislature after the asymmetric decentralization of jurisdiction 1 has been taking place.

Proposition 8

The inefficient region is more likely to accept the asymmetric decentralization scenario of region 1 if the bargaining power of the efficient region (\(\theta\)) is low enough.

The proof of Proposition 8 is in the Appendix.

Under asymmetric decentralization, if the efficient region has a too large bargaining power, the inefficient one might have no gain from accepting an asymmetrically decentralized setting. All the gains are, indeed, captured by the efficient region. Therefore, the inefficient region does not use its veto power against the asymmetric decentralization of region 1 if the decision-making power of the latter is suitably reduced in favor of jurisdiction 2.

8 Inter-regional income disparity, fiscal flows and regional specific costs: an extension

So far, we have considered local characteristics only related to technological issues and consisting in different production costs. This means that regions are all the same, except for the efficiency in the production of local public good, and no inter-regional differences in the per capita income are admitted. Actually, local characteristics are likely to affect also the demand side, including income heterogeneity among regions that is one of the main drivers that could give reasons for greater autonomy at the local level (Mangiameli et al. 2020).

Following this reasoning—and to make the model more realistic—, we relax the hypothesis of homogeneity in regional income, also including an inter-regional equalization mechanism across regions. Indeed, inter-regional income disparities imply the existence of inter-regional fiscal flows, which could play a role in the choice between full centralization and asymmetric decentralization.Footnote 8

Furthermore, in this extension of the model, we treat the production costs of the public good as regional specific. The assumption of regional specific costs captures the fact that the production costs might depend on the differences in territorial features of the regions (e.g., orography, urban concentration, and other exogenous elements) that cannot be modified by changing the government’s responsibility of public goods provision. The regional specific costs are, in fact, different from the institutional specific costs that depend, instead, on the different institutional quality of the two tiers of government under consideration.

In order to address all these issues, we revise both the hypotheses and notation as follows. Consider two equal size regions, with population \(N_1=N_2=N\). Regions differ in their per capita income. Let us consider the per capita income of each region as \(y_1=(1+a)y=\delta _1 y\) and \(y_2=(1-a)y=\delta _2 y\), where \(0<a<1\) is the disparity index and y the average national per capita income. Thus, the following relation holds: \(y_2\le y \le y_1\). We normalize the average national per capita income by setting \(y=1\). Citizens are all alike; that is, they are endowed with the same intra-regional income \(y_i\). We also assume that \(c_1 < c_2\).

Furthermore, we denote by \(F^C\ge 0\) the per capita transfer from region 1 to region 2 under full centralization and by \(F^A\ge 0\) the per capita transfer from region 1 to region 2 under asymmetric decentralization.

We focus on the comparison between the two most relevant institutional settings, also most frequently occurring in the real world as explained before: asymmetric decentralization and full centralization.

8.1 Full centralization

Let us define \(\tau _i={\tilde{t}} y_i= {\tilde{t}} \delta _i\) as the per capita tax burden paid by the citizens of region i under full centralization and a proportional tax rate \({\tilde{t}}\). In order to highlight the role of tax flows from the richer to the poorer region, we can write \(\tau _1={\tilde{t}}\delta _1=\tau +F^C\) and \(\tau _2={\tilde{t}}\delta _2=\tau -F^C\), where \(\tau =\frac{\tau _1+\tau _2}{2}\) is the average tax burden.

Accordingly, the government budget constraint under full centralization can be written as

Since the unit costs are regional specific, \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) do not change when the central government provides the public good for the regions.Footnote 9 Note that with regional specific costs, the cost paid by the central government is the average of the regional costs, \(c=\frac{c_1+c_2}{2}\), thus there is neither subadditivity nor superadditivity in costs (no scale economy). Thus, the per capita tax burden is

The agreement utilities are

We assume that in disagreement \({\tilde{g}}^{C} =1\), \(F^{C^d}=0\) and \(\tau =\frac{c}{N}\). Thus, the disagreement utilities are:

with \(i=1,2\). The net gains from bargaining are:

and

We solve the bargaining problem by solving the following Nash product \(\max _{{\tilde{g}}^{C} } (\phi _1^C)^\theta (\phi _2^C)^{1-\theta }\). The solution is:

Thus, individual equilibrium utilities under full centralization are:

and

Since full centralization is characterized by a unique tax rate \({\tilde{t}} = \frac{\tau _1}{1+a}=\frac{\tau _2}{1-a}\), then \(\frac{\tau +F^C}{1+a}=\frac{\tau -F^C}{1-a}\). Furthermore, recalling that in the equilibrium \(\tau =\lambda\), we can write \(\frac{\lambda +F^C}{1+a}=\frac{\lambda -F^C}{1-a}\). Solving for \(F^C\) we obtain the per-capita amount of transfer from the richer to the poorer region:

that is, a larger income disparity a implies a larger transfer \(F^C\). Then, it is easy to calculate that the national tax rate is equal, in the equilibrium, to \({\tilde{t}}=\frac{\tau +F^C}{1+a}=\frac{\lambda (1+a)}{1+a}=\lambda\).

8.2 Asymmetric decentralization

We assume that in the case of asymmetric decentralization the rich region sets its own level of local public good provision and finances it with its own tax revenue. Thus, the budget constraint of the regional government is \(c_1{\tilde{g}}_1^A=N\tau _1^A\). Moreover, region 1 commits itself to pay a per capita lump sum transfer, \(F^A\).

The transfer \(F^A\) has a minimum value (\(F_{min}\)), which makes it convenient for the poorer region to accept asymmetric decentralization, and a maximum value (\(F^{max}\)), which represents the amount that the richer region is willing to pay in order to convince the poorer one to let asymmetric decentralization of region 1.Footnote 10 In that context, we analyse whether an interval \((F_{min}, F^{max})\) with \(F_{min}<F^{max}\) exists.

Before discussing the scenario with different types of transfer, we should recall that, even in this case—and like in the absence of income disparity—, asymmetric decentralization is not a secession. Indeed, the richer region does not leave the federation and it is involved in a national bargaining process regarding public good provision in the poorer region. The point at stake is that the richer region has an interest in it for, at least, two reasons: i) it contributes to the financing of public good in region 2 through the tax transfer mechanism; ii) it is interested in the internalization of externalities.

Thus, under asymmetric decentralization, the rich region sets its own provision by maximizing the following utility function with respect to \({\tilde{g}}_{1}^A\)

under the regional budget constraint \(c_1 {\tilde{g}}_1^A=N\tau _1^A\). Thus, equilibrium policy in region 1 is

Note that the latter is the same equilibrium value of full decentralized, which is different than the secession case because region 1 pays a tax transfer \(F^A\) that allows to internalise the externalities produced by the centralized provision in region 2. The utility of asymmetric decentralization is not equal to that under full centralization. In fact, in the negotiation within the central government on the public good provision in region 2, the agreement utility of the representative of region 1 is:

which increases with the level of public good provision in region 2 and decreases with the transfer provided to the same region, \(F_A\).

The decision over the public good provision in the poorer region, which is decided at central government level where both regions bargain, is subject to the budget constraint \(c {\tilde{g}}_2^A = N(\tau _2^A + F^A)\); That is, the government finances the provision in region 2 by both the tax revenue collected in region 2 and the financial flow from the rich region \(F^A\). Furthermore, given the assumption of regional specific costs it must be \(c=c_2\).

The disagreement utility for the rich region when negotiating on \({\tilde{g}}_2^A\) is:

which includes the transfer \(F^A\) that region 1 has committed to pay and that, in the case of disagreement, contributes to finance the minimum level of provision \({\tilde{g}}_2^A=1\). The net gain from reaching an agreement for region 1 is:

The agreement utility for the poorer region is:

In the case of disagreement, the budget constraint is \({\tilde{g}}_2^A=1= \frac{N}{c_2}(\tau _2^d+F^A)\). Accordingly, the disagreement utility of the representative of region 2 is

The net gain for region 2 is

As a result, the equilibrium provision of local public good in region 2 is the value that maximizes the bargaining function

As for Eq. 15, there exists an utopian first best solution \({\tilde{g}}_2^{FB}=\frac{N}{c_2}\lambda (1-k)\), which is the solution for \(\theta =0\). The bargaining solution satisfies the following relations

with \(\frac{\partial {\tilde{g}}_2^A}{\partial \theta }>0\). The proofs of Propositions 3 and 4 apply.Footnote 11

Thus, the bargaining between regions allows the rich region to partially internalize the spillover produced by the provision in region 2.

Then, the rich region prefers asymmetric decentralization over full centralization if \({\tilde{u}}_1^C<{\tilde{u}}_1^A\), thus if

After rearranging, we can writeFootnote 12

Thus, region 1 prefers asymmetric decentralization if

where, recalling the proofs of Propositions 3 and 6, \({\tilde{z}}(\theta )=\frac{{\tilde{g}}_2^A}{{\tilde{g}}_2^{FB}}\). Furthermore, \({\tilde{z}}\) is increasing in \(\theta\) and is equal to 1 when \(\theta =0\).

Thus, given the definition of \(c=\frac{c_1+c_2}{2}\) the following Proposition holds.

Proposition 9

There exists a maximum value of intergovernmental transfer under asymmetric decentralization, \(F^{max}\), such that, for \(F^A\le F^{max}\), the rich region requests asymmetric decentralization. \(F^{max}\) increases in \(\theta\), decreases in \(c_1\) and increases in \(c_2\). Furthermore, \(F^{max}=F^C\) when \(k=0\) and \(c_1=c_2\). The impact of \(k>0\) is ambiguous.

According to Proposition 9, if the richer region can avoid the cross-subsidization to the poorer one, then it is available to pay a higher transfer than in full centralization.

Region 2 opposes a veto on the asymmetric decentralization of region 1 if \({\tilde{u}}_2^A {<} {\tilde{u}}_2^C\), i.e. if

substituting the equilibrium values of g and recalling that \({\tilde{g}}_2^A={\tilde{z}}{\tilde{g}}_2^{FB}={\tilde{z}}\frac{N\lambda (1-k)}{c_2}\)

then

Thus, if \(F^A<F_{min}\), region 2 opposes a veto against the asymmetric decentralization of region 1. Note that

Now, we can state the following Proposition.

Proposition 10

There exists a minimum value of intergovernmental transfer under asymmetric decentralization, \(F_{min}\), such that, for \(F^A \ge F_{min}\), the poorer region is willing to accept the asymmetric decentralization of region 1. \(F_{min}\) increases in \(\theta\). The impact of differences in costs and k is ambiguous. For small differences among regional costs, \(F_{min}>F^C\).

The proof of Proposition 10 is in the Appendix.

In order to make both regions accept asymmetric decentralization the transfer should be set within the interval among \(F_{min}\) and \(F_{Max}\). Thus, a necessary condition is that \(F_{min} \le F^{max}\). From Propositions 9 and 10 it is clear that for no spillover and no differences in costs \(F_{max}=F^C<F_{min}\), thus the agreement is not feasible.

Generalizing, the following Proposition holds.

Proposition 11

An agreement on asymmetric decentralization that makes both regions better off is feasible only for \(c_1\) sufficiently lower than \(c_2\). Moreover, in order to make an agreement more likely, the bargaining power should be set to a \(\theta ^*\) value that increases with the spillover. Finally, in order to achieve an agreement, the greater the spillover, the greater the cost differences should be.

The proof of Proposition 11 is in the Appendix.

For a given spillover, \(\theta <\theta ^*\) implies that the bargaining power is too distorted towards the poorer region, the one with the highest cost, while \(\theta >\theta ^*\) implies that it is distorted towards the richer region. In both cases an agreement is not feasible, unless \(c_1\) is sufficiently lower than \(c_2\).

Furthermore, an interval \((F_{min}, F^{max})\) with \(F_{min} \le F^A \le F^{max}\) exists if the cost difference between regions is high enough. That is, the efficiency gain that the richer region can achieve thanks to a sufficiently lower production cost can be partly used to compensate the welfare loss of the poorer region caused by the asymmetric decentralization of the richer one. In other words, asymmetric decentralization can, under certain conditions, guarantee mutual benefits for all regions through appropriate tax transfers.

9 Concluding remarks

How policy-making power is divided among levels of governments has received some attention by the literature on federalism starting from the contribution by Buchanan (1987), followed by more recent public choice studies (Congleton et al. 2003; Congleton 2006). The main drivers in explaining different decentralized institutional settings concern autonomy issues and public goods provision (Besley and Coate 2003; Cerniglia et al. 2019), redistribution grounds and allocation of public resources (Giuranno 2009; Zanardi 2017), regions’ political preferences and ethnic conflict within the country (Coakley 2004; Mintz 2019).

Although in all those cases an asymmetric form of decentralization is likely the outcome, litte attention has been paid by the existing literature on the institutional consequences of that. Our paper contributes to this debate, being also motivated by different pictures emerging from many countries wherein asymmetric decentralization seems to be the rule, rather than the exception.

Our model shows that asymmetric decentralization introduces distortions in the public decision-making process. This is mostly due to the fact that jurisdictions having opted for decentralization have not only the autonomy to determine their public goods provision but also, and more importantly for the policy outcome, the power of co-determining the public provision assigned to the non-decentralized jurisdictions by the central government. This power to interfere at the central level should be, actually, limited in order to do not harm citizens living in jurisdictions that prefer not selecting the decentralized setting given their inefficient costs structure.

From a policy viewpoint, asymmetric decentralization introduces new elements in the traditional trade-off between centralization and decentralization. Accordingly, centralization is seen as the possibility to internalize spillovers as well as to eliminate the free-riding incentives of local jurisdictions. On the other hand, decentralization allows for a better tailoring of public policies to local characteristics. The new elements that the policy maker should take into account in designing an asymmetric multilevel government set-up refer to the asymmetric distribution of benefits in favour of those jurisdictions that manage to obtain the decentralization of their functions. The reason is that asymmetric decentralization introduces new free-riding opportunities in favour of the regions that decentralize that contradicts the principle of institutional cooperation among the different tiers of government. However, it is also true that jurisdictions that do not decentralize can benefit from a higher efficiency that the central government may, under certain conditions, guarantee. When spillovers are the cause of free-riding, but their magnitude is small, asymmetric decentralization is clearly more convenient than other forms of local governance, such as full either decentralization or centralization for all jurisdictions. Low spillovers lead to less free-riding in local provision, which may make asymmetric decentralization appealing to both citizens and decision-makers because it may increase efficiency with small free-riding distortions.

Instead, when spillovers are relevant, the policy-maker must endeavour to make an institutional engineering effort in order to limit the negative effects generated by opportunistic behaviour. We find that the latter may be limited by distributing the decision-making power at the centralized level of government in favour of the regions that do not decentralize.

When relaxing the hypothesis of homogeneity in income across regions and assuming that the richer region asks for asymmetric decentralization, we find that asymmetric decentralization can be simultaneously advantageous for all regions, i.e. rich and poor, if it allows to achieve efficiency gains such as to compensate poor regions through the design of appropriate equalization transfers. Inter-regional differences in the costs of supplying public goods and services can allow for significant efficiency gains, especially when costs are institutional specific, i.e. they change with the level of government. Efficiency gains are also possible with regional specific costs, which do not change with the level of government, as the richer region that decentralizes in this way would avoid the cross-subsidization that a centralized supply would entail.

Notes

In recent years, after a popular referendum in 2006 a new Statute of Autonomy granted self-government to Catalonia, including the possibility of separate membership in the UNESCO, further increasing Spain’s asymmetrical disposition.

However, for the provision of many public goods, differences in costs depend only on the objective characteristics of regions. In this case, the cost for providing public goods in a region does not change when the providing government changes. We address the case of regional specific costs, as opposed to institutional specific costs, in Sect. 8.

In Sect. 8, we relax the assumption of \(c_1< c <c_2\) admitting very large economies of scale, i.e. \(c < c_1\).

Note that we assume that a minimum level of public good \(g^{C}\) is always guaranteed; that is, \(g^{C}\) can be seen as a merit good. Furthermore, without loss of generality, we set the default value of \(g^{C}\) to unity, which also ensures an always weakly positive value of \(\ln g^{C}\).

Note that solution (6) exists if and only if \(\lambda >\frac{c_{i}}{1-k}\). Furthermore, a sufficient condition in order to have \(g_{i}^{D}\ge 1\) \(\forall\) \(k\le 1/2\) is \(\lambda \ge 2c_{2}\).

In order to see that also consider that \(\frac{dg_{2}^{A}}{dk}<0\), as shown in Proposition 3, and that \(\frac{dg^{C}}{dk}=0\).

The assumptions introduced in this section allow to address some of the most institutionally relevant trade-offs usually faced by the policy-makers in some advanced economies (e.g., Italy, Spain, United Kingdom, Germany).

Note that, unless the regional tax burdens are set in order to have \(\tau _i=\frac{c_i {\tilde{g}}^{C}}{N}\), which is not the case under consideration in this model, there is a cross-subsidization from a region to another.

The case of \(F^A=0\), i.e. no transfer is provided, is already treated when income homogeneity among regions has been assumed.

Note that when the production costs are regional specific, both the first best equilibrium and the Nash bargaining solutions for region 2 are lower than the provision levels set when the production costs are government specific.

From this formula, we can derive the case of institutional specific costs by substituting c to \(c_2\). Moreover, we can analyse how the results change if we relax the hypothesis \(c_1< c < c_2\), when considering institutional specific costs. In this case, if \(c\le c_1\), the incentive of requesting asymmetric decentralization is very low and it is due only to the possible reduction in transfer, since with \(\lambda \left( 1-k\right) \ln \frac{c}{c_1}\le 0\) there is an efficiency loss due to that the richer region cannot exploit the advantages from the economies of scale.

It is the same condition if we impose no transfer (\(F^C=F^A=0\)) and if we consider institutional specific costs (\(c_1\le c_2=c\)).

References

Besley, T., & Coate, S. (2003). Centralized versus decentralized provision of local public goods: A political economy approach. Journal of Public Economics, 87(12), 2611–2637.

Biswas, R., & Giuranno, M. G. (2019). Internal migration and public policy. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 19(4), 1–16.

Buchanan, J. M. (1987). The constitution of economic policy. The American Economic Review, 77(3), 243–250.

Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. (1962). The calculus of consent (Vol. 3). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Cerniglia, F., Longaretti, R., & Zanardi, A. (2019). Emergence of asymmetric fiscal federalism: Centrifugal and centripetal forces. Technical report, Paper presented at the SIEP Conference 2019.

Coakley, J. (2004). The territorial management of ethnic conflict. Abingdon: Routledge.

Congleton, R. D. (2006). Handbook of Fiscal Federalism, chapter Asymmetric federalism and the political economy of decentralization (pp. 131–153). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishers.

Congleton, R. D., Kyriacou, A., & Bacaria, J. (2003). A theory of menu federalism: Decentralization by political agreement. Constitutional Political Economy, 14(3), 167–190.

Conversi, D. (2007). Asymmetry in quasi-federal and unitary states. Ethnopolitics, 6(1), 121–124.

Eupolis, Lombardia. (2017). Regionalismo differenziato e risorse finanziarie. Consiglio Regionale della Lombardia: Technical report.

Flynn, M. K. (2004). Between autonomy and federalism Spain. Managing and Settling Ethnic Conflicts (pp. 139–160). Berlin: Springer.

Giuranno, M. G. (2009). Regional income disparity and the size of the public sector. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 11(5), 697–719.

Giuranno, M. G. (2010). Pooling sovereignty under the subsidiary principle. European Journal of Political Economy, 26(1), 125–136.

Hughes, J. (2001). Managing secession potential in the Russian federation. Regional and Federal Studies, 11(3), 36–68.

Jack, W. (2004). The organization of public service provision. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 6(3), 409–425.

Keating, M. (2000). The minority nations of Spain and European integration: A new framework for autonomy? Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, 1(1), 29–42.

Lapidus, G. W. (1999). Asymmetrical federalism and state breakdown in Russia. Post-Soviet Affairs, 15(1), 74–82.

Libman, A. (2010). Constitutions, regulations, and taxes: Contradictions of different aspects of decentralization. Journal of Comparative Economics, 38(4), 395–418.

Libman, A., & Rochlitz, M. (2019). Federalism in China and Russia. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

MacGarry, J. (2001). Northern Ireland and the divided world: The Northern Ireland conflict and the good Friday agreement in comparative perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mangiameli, S., Filippetti, A., Tuzi, F., & Cipolloni, C. (2020). Prima che il Nord somigli al Sud. Rubbettino: Le Regioni tra divario e asimmetria.

Martinez-Vazquez, J. (2007). Fiscal fragmentation in decentralized countries. Subsidiarity, solidarity and asymmetry, chapter asymmetric federalism in Russia: Cure or poison? (pp. 227–266). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Mintz, J. (2019). Two different conflicts in federal systems: An application to canada. The School of Public Policy Publications, 12, 14.

Oates, W. E. (1972). Fiscal Federalism. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Oates, W. E. (2005). Toward a second-generation theory of fiscal federalism. International Tax and Public Finance, 12(4), 349–373.

Ravenda, D., Giuranno, M. G., Valencia-Silva, M. M., Argiles-Bosch, J. M., & García-Blandón, J. (2020). The effects of mafia infiltration on public procurement performance. European Journal of Political Economy, 64, 101923.

Rizzo, L., & Secomandi, R. (2019). Effetti finanziari delle richieste di autonomia regionale: prime simulazioni. IRPET: Technical report.

Tavares, A. F., & Camöes, P. J. (2007). Local service delivery choices in Portugal: A political transaction costs framework. Local Government Studies, 33(4), 535–553.

Tollison, R. D., & Buchanan, J. M. (1972). Theory of public choice: Political applications of economics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Tommasi, M., & Weinschelbaum, F. (2007). Centralization vs. decentralization: A principal-agent analysis. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 9(2), 369–389.

Weingast, B. R. (2009). Second generation fiscal federalism: The implications of fiscal incentives. Journal of Urban Economics, 65(3), 279–293.

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The economic institutions of capitalism: Firms, markets, relational contracting. New York: Free Press.

Zanardi, A. (2017). Le richieste di federalismo differenziato: una nota sui profili di finanza pubblica. Astrid Rassegna, (11).

Zantman, W. (2002). Constitutional design and regional favoritism. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 4(1), 71–93.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Giampaolo Arachi and the participants at the XXXII Annual Conference of the Italian Society of Public Economics for useful comments. Special thanks are due to two anonymous referees for their insightful suggestions on a previous version of the paper.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Proof of Proposition 3

The comparative statics with respect to \(g_{1}^{A}\) is straightforward. Instead, in order to study the comparative statics with respect to \(g_{2}^{A}\), we study the first order condition (Eq. 15). Algebrically it leads to:

where \(\frac{g_{2}^{A}-1}{\ln g_{2}^{A}}<g_2^{A}\),

since \(\ln g_2^A-\frac{g_2^A-1}{g_2^A} >0\) and

since \(\left[ -\ln g_2^a+2\frac{g_2^A-1}{g_2^A+1}\right] <0\)

Monotonicity implies that G can be inverted thus

the provision of public good in inefficient region in asymmetric decentralization increases more than proportionally on respect to the utopia first best provision in the same region. Any variable which moves up the utopian public expenditure increases also the expenditure in asymmetric decentralization

Let us define \(F(\theta ,g_2^A,g_2^{FB})=G(g_2^A,\theta )-g_2^{FB}\), for the implicit function theorem \(\frac{dg_2^A}{d\theta }=-\frac{F_\theta }{F_{g_2^A}}=-\frac{G_\theta }{G_{g_2^A}}\) since \(G_{g_2^A}>0\), \(sign\left( \frac{dg_2^A}{d\theta }\right) =-sign(G_\theta )\).

Therefore,

thus \(\frac{dg_2^A}{d\theta }>0\)

Proposition 3 is proved.

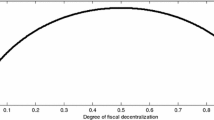

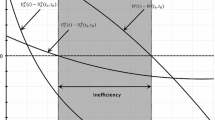

The above analysis can be showed in the following graph

The figure shows that for \(1\le g_2^{FB}\le \frac{\lambda }{c}\), a unique solution always exists with \(g_2^{A}\ge g_2^{FB}\). All the variables which increase the utopia point \(g_2^{FB}\) increase also the solution of Nash Bargaining \(g_2^{A}\). Seemingly, when \(\theta\) increases, the RHS decreases (dashed lines) rotating clockwise, thus \(g_2^{A}\) increases.

1.2 Proof of Proposition 5

Region 2 prefers full decentralization to asymmetric decentralization if the following condition is true

where, the left and right hand sides are defined in Eqs. (11) and (7), respectively, considered in their equilibrium outcomes. Thus,

then

We can set \(z\equiv \frac{g_{2}^{A}}{g_{2}^{FB}}>1\). Then,

which is true when \(z>{\overline{z}}\), where \({\overline{z}}\) means sufficiently high.

We do not know the explicit equation of \({\overline{z}}\). However, we know that region 2 does prefer asymmetric decentralization to full decentralization when \(z<{\overline{z}}\), which proves the Proposition given that

Since \(g_2^A>g_2^{FB}\), then \(\frac{1}{g_2^A}\frac{dg_2^A}{d\theta }<\frac{1}{g_2^{FB}}\frac{dg_2^A}{d\theta }\). Now, let us consider the value of \(\theta\), which we denote with \(\theta ={\overline{\theta }}\), such that \(z={\overline{z}}\), which is the point in the graph where \(\ln z+\ln c_{2}-\ln c = z-1\), i.e. the point where region 2 is indifferent between full and asymmetric decentralization. Now, any \(\theta >{\overline{\theta }}\) reduces the threshold to, say, \(\overline{{\overline{z}}}<{\overline{z}}\). This, in turn, makes the condition \(\ln z+\ln c_{2}-\ln c<z-1\) more likely to be satisfied. Furthermore, note that the threshold needed in order to make full decentralization better off for jurisdiction 2 increases in \(c_{2}\). In order to see that, consider that

which proves the Proposition.

1.3 Proof of Proposition 6

We compare full centralization (Eq. 5) with asymmetric decentralization for region 1 (Eq. 9), as follows:

Recalling that \(\lambda \ge c\), the left hand side is weakly positive, as well as the right hand side. Furthermore, when \(k=0\) the above inequality becomes

that is always true for \(\lambda {>} c\). Thus, when \(k=0\) the efficient region prefers asymmetric decentralization because \(c_1\le c\). Instead, as k increases the left hand side remains constant. For \(k=1/2\) the right hand side becomes

Thus, it is more likely to prefer asymmetric decentralization either the higher the efficiency ratio \((\frac{c}{c_1})\) is or the higher the provision of public good in the inefficient region \(g_2^A\) is.

Proposition is proved.

1.4 Proof of Propositions 8 and 7

We compare asymmetric decentralization for region 2 (Eq. 11) with full centralization (Eq. 5), as follows:

Recall the definition \(z\equiv \frac{ g_{2}^{A} }{g_2^{FB}}>1\)

When the right hand side (RHS) is greater than the left hand side (LHS), the inefficient region 2 prefers full centralization to asymmetric decentralization.

From the proof of Proposition 3, \(g_2^A\) increases more than proportionally compared to \(g_2^{FB}\), then \(\frac{d z}{dg_2^{FB}}>0\). Since \(\frac{d RHS}{d z}=\frac{z-1}{z}>0\) always increases in z, \(\frac{dRHS}{d\theta }=\frac{dRHS}{dz}\frac{dz}{dg_2^{A}}\frac{dg_2^{A}}{d\theta }>0\). Moreover \(\frac{dRHS}{dc}=\frac{dRHS}{dz}\frac{dz}{dg_2^{FB}}\frac{dg_2^{FB}}{dc}<0\). Thus the right hand side increases with \(\theta\) and decreases with c.

Inspecting LHS it is easy to demonstrate that it increases with c and decreases with \(c_1\).

Thus, it is more likely that the inefficient region would not use its veto against asymmetric decentralization if the efficiency of region 1 is sufficiently higher than that of the central government, i.e. if the efficiency ratio \(\frac{c}{c_1}\) is high enough. Moreover, region 1 does not use its veto power when the bargaining leverage of region 1, \(\theta\), is low. In both cases it is more likely that \(LHS>RHS\). The Propositions 7 and 8 are proved.

1.5 Proof of Propositions 9

From Eq. 16, the maximum transfer that the rich region can pay depends on three elements:

-

\(\lambda \left( k + \ln (1-k)\right) \le 0\) is the cost of having a partial and not a full internalization of spillover; note that such element is decreasing in k, i.e. the absolute value of that cost increases with the spillover (k).

-

\(k\lambda \ln {\tilde{z}}(\theta )= k\lambda \ln \frac{{\tilde{g}}_2^A}{{\tilde{g}}_2^{FB}}\ge 0\) is the benefit that the rich region receives by bargaining with the poorer region a level of local public goods greater than the poorer region optimal level. It increases with \(\theta\), as we demonstrate in Proposition 3. The effect of k is ambiguous.

-

Finally, recalling that \(c=\frac{c_1+c_2}{2}\), \(\lambda \ln \frac{c}{c_1^{1-k} c_2^k}\ge 0\) when \(0\le k\le 1/2\) is the efficiency gain that the rich region obtains when it pays the local public good at its lower costs, instead of cross-subsidizing the public good of the poorer region. Such value is equal to zero if there is no cost difference between regions. It increases when the cost difference among regions increases since it is the ratio between the arithmetic mean c and the weighed geometric one, where the weight of the lower values is higher (\(0\le k \le 1/2\)). It decreases in k.

Thus, the effect of k on \(F_{max}\) is ambiguous. in any case, when \(k=0\) \(F_{max}>F^C\). Moreover,

thus \(F_{Max}\) is decreasing in \(c_1\), while

After rearranging

Proposition 9 is proved.

1.6 Proof of Propositions 10

From Eq. 17

-

\(\lambda (1-k)\left[ ({\tilde{z}}-1)-\ln {\tilde{z}}\right] >0\) is increasing \({\tilde{z}}\). Since \({\tilde{z}}\) is increasing in the bargaining power, \(\theta\), \(F_{min}\) is increasing in the bargaining power of rich region.

-

\(-\lambda \left[ k+\ln (1-k)\right] \ge 0\) is the cost of not internalizing spillover.

-

\(\lambda \ln \frac{c_2^{1-k}c_1^k}{c}\) depends on the difference between regions. Note that without spillover (\(k=0\)) it is positive, while for high spillover (\(k=1/2\)) it is negative.

Only with a high difference in regional costs \(F_{min}\) could become lower then \(F^C\). Without cost differences, the poorer region will always request a higher transfers than the one it receives under full centralization in order to accept asymmetric decentralization.

Note that if \(F^A=0\), the poorer region looses both the internalization of spillover and the financial flow from the rich region (thus it pays more taxes). Therefore, the poorer region uses its veto power against asymmetric decentralization.

The above condition is very similarFootnote 13 to the one in the proof of Propositions 7 and 8.

Moreover, since \(\frac{c_2^{1-k}c_1^k}{c}=2\frac{c_2^{1-k}c_1^k}{c_1+c_2}\)

and

which is positive if k is sufficiently high and \(c_1\) sufficiently smaller than \(c_2\), otherwise it is negative. Furthermore,

that is negative if k is sufficiently high and \(c_1\) sufficiently smaller than \(c_2\), otherwise it is positive.

Proposition 10 is proved.

1.7 Proof of Propositions 11.

\(F_{min}<F_{Max}\) if

then

Since in the parameters’ space \({\tilde{z}}\ge 1\) and \(k\in \left[ 0,1/2\right]\),

An agreement is feasible (a necessary condition is \(F_{max}-F_{min}>0\)) only if \(\ln \frac{c}{\sqrt{c_1c_2}}\) is big enough, thus if the difference \(c_2-c_1\) is large enough.

Moreover,

thus

For a given value of the spillover there exists a maximum value of \(\theta ^*\) such that \({\tilde{z}}^*=\frac{1}{1-k}\).

Calculating the value in the maximum

that can be positive only if \(\ln \frac{c}{\sqrt{c_1c_2}}\) is big enough.

Moreover,

Thus, the higher the spillover, the higher both \(\theta ^*\) and the difference between \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) should be in order to have an agreement for asymmetric decentralization.

Proposition 11 is proved.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fiorillo, F., Giuranno, M.G. & Sacchi, A. Asymmetric decentralization: distortions and opportunities. Econ Polit 38, 625–656 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-020-00211-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-020-00211-7

Keywords

- Public goods

- Asymmetric decentralization

- Intergovernmental relations

- Equalization transfers

- Positive political economy