Abstract

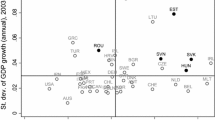

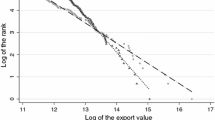

Recent empirical work has documented the high concentration of trade flows, and the large role played by few “big hits” in each country’s export. We propose a simple stochastic benchmark against which we assess each economy’s actual number of “big hits”. We show that most European countries underperform the benchmark, while China, the US and Germany do better. A low number of “big hits” (relative to our prediction) is associated with higher export volatility. Looking at possible determinants of “big hits”, we find they depend on the actual performance of each country, so that industrial policy needs to be country-specific.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This happens because in an open economy with a lack of property rights, the knowledge or product discovered is not appropriable, thus leading to imitation by other investors thereby resulting in an insufficient rate of return for the initial discoverer. Consequently, investment is under-supplied or, in other words, there is too little “search” and “discovery”.

The authors document that manufacturing export success is intrinsically related to economic development: since a large number of BH testifies for export success, it implies export growth and exerts a positive impact on overall economic growth and development.

The BACI dataset reconciles the data reported by exporting and importing countries to the United Nations Statistics Division. For more information on the construction of BACI, refer to Gaulier and Zignago (2010).

This value refers to 2005. The coefficient increases over time (results are not reported here).

In the network literature, preferential attachment is typically associated with the pioneering work by Barabási and Albert (1999) and gives rise to a very skewed connectivity distributions (few well-connected nodes coexist alongside a large number of peripheral actors). This feature is found to characterise many real-world applications besides trade, such as the internet (Faloutsos et al. 1999; Riccaboni et al. 2013), world-wide air transportation (Guimera et al. 2005), migration (Sgrignoli et al. 2015), mobile communications (Onnela et al. 2007) and interbank payments (Soramäki et al. 2007).

In principle, the initial value of trade links could be 1, or be defined in terms of some exogenous determinant such as size and distance, as in a standard gravity model.

Easterly et al. (2009) suggest that a BH is a large export flow, but they do not provide any precise definition for it.

A possible explanation for the fact the model overpredicts, on average, the number of BHs is the assumption that all countries draw their export values from the same distribution. This may lead us to overstate the potential number of BHs for small countries, if the distribution of their export flows is more concentrated around small values.

In this case, however, it is necessary to control for the size of the country or, better, for the number of product–destination flows exported (\(K_i\)). This is because, unlike the Theil index which is both scale and population independent, as the number of items across which the HH index is computed grows, its value goes down mechanically.

Using the standard deviation or the variance of growth rates as a measure of volatility is quite common in the empirical literature; see for instance Koren and Tenreyro (2007).

See the "Appendix" for formal definitions of network measures and the other explanatory variables.

See Magnus et al. (2010) for a comparison between WALS and BMA.

References

Armenter, R., & Koren, M. (2014). A balls-and-bins model of trade. American Economic Review, 104(7), 2127–2151.

Baldwin, R., & Harrigan, J. (2011). Zeros, quality, and space: Trade theory and trade evidence. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 3(2), 60–88.

Barabási, A.-L., & Albert, R. (1999). Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science, 286(5439), 509–512.

Barro, R. J., & Lee, J.-W. (2012). A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. Journal of Development Economics, 104, 184–198.

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2008). Financing patterns around the world: Are small firms different? Journal of Financial Economics, 89(3), 467–487.

Beck, T., & Demirguc-Kunt, A. (2009). Financial institutions and markets across countries and over time—Data and analysis. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series, 4943.

Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2000). A new database on financial development and structure. World Bank Economic Review, 14, 597–605.

Bee, M. (2006). Estimating the parameters in the loss distribution approach: How can we deal with truncated data? In E. Davis (Ed.), The advanced measurement approach to operational risk (pp. 123–144). London: Riskbooks.

Bhattacharya, K., Mukherjee, G., Saramäki, J., Kaski, K., & Manna, S. S. (2008). The international trade network: Weighted network analysis and modelling. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 2008(02), P02002.

Blomstrom, M., Lipsey, R. E., & Zejan, M. (1994). What explains developing country growth? In Convergence of productivity: Cross-national studies and historical evidence (pp. 243–259). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Cadot, O., Carrére, C., & Strauss-Kahn, V. (2011). Export diversification: What’s behind the hump? Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(2), 590–605.

Chaney, T. (2014). The network structure of international trade. American Economic Review, 104(11), 3600–3634.

Easterly, W., Reshef, A., & Schwenkenberg, J. (2009). The power of exports. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series, 5081.

Ellison, G., & Glaeser, E. L. (1997). Geographic concentration in US manufacturing industries: A dartboard approach. Journal of Political Economy, 105(5), 889–927.

Faloutsos, M., Faloutsos, P., & Faloutsos, C. (1999). On power-law relationships of the internet topology. ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review, 29(4), 251–262.

Foschi, R., Riccaboni, M., & Schiavo, S. (2014). Preferential attachment in multiple trade networks. Physical Review E, 90(2), 022817.

Fu, D., Pammolli, F., Buldyrev, S. V., Riccaboni, M., Matia, K., Yamasaki, K., et al. (2005). The growth of business firms: Theoretical framework and empirical evidence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(52), 18801–18806.

Gaulier, G., & Zignago, S. (2010). Baci: International trade database at the product-level (the 1994–2007 version). Working Paper 2010-23, CEPII.

Guimera, R., Mossa, S., Turtschi, A., & Amaral, L. N. (2005). The worldwide air transportation network: Anomalous centrality, community structure, and cities’ global roles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(22), 7794–7799.

Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica, 46(6), 1251–1271. (10372)

Hausmann, R., & Hidalgo, C. A. (2011). The network structure of economic output. Journal of Economic Growth, 16(4), 309–342.

Hausmann, R., & Rodrik, D. (2003). Economic development as self-discovery. Journal of Development Economics, 72(2), 603–633.

Hausmann, R., & Rodrik, D. (2005). Self-discovery in a development strategy for El Salvador. Economia, 6(1), 43–101.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M., & Rubinstein, Y. (2008). Estimating trade flows: Trading partners and trading volumes. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2), 441–487.

Hidalgo, C. A., & Hausmann, R. (2009). The building blocks of economic complexity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(26), 10570–10575.

Hidalgo, C. A., Klinger, B., Barabási, A.-L., & Hausmann, R. (2007). The product space conditions the development of nations. Science, 317(5837), 482–487.

Hummels, D., & Klenow, P. J. (2005). The variety and quality of a nation’s exports. American Economic Review, 95(3), 704–723.

Imbs, J., & Wacziarg, R. (2003). Stages of diversification. American Economic Review, 93(1), 63–86.

Jackson, M. O. (2008). Social and economic networks. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kaldor, N. (1957). A model of economic growth. The Economic Journal, 67(268), 591–624.

Koren, M., & Tenreyro, S. (2007). Volatility and development. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(1), 243–287.

Krautheim, S. (2012). Heterogeneous firms, exporter networks and the effect of distance on international trade. Journal of International Economics, 87(1), 27–35.

Magnus, J. R., Powell, O., & Prüfer, P. (2010). A comparison of two model averaging techniques with an application to growth empirics. Journal of Econometrics, 154(2), 139–153.

Nair-Reichert, U., & Weinhold, D. (2001). Causality tests for cross-country panels: a new look at fdi and economic growth in developing countries. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 63(2), 153–171.

Onnela, J.-P., Saramaki, J., Hyvonen, J., Szabó, G., Lazer, D., Kaski, K., et al. (2007). Structure and tie strengths in mobile communication networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(18), 7332–7336.

Riccaboni, M., Rossi, A., & Schiavo, S. (2013). Global networks of trade and bits. Journal of Economic Interaction and Coordination, 8(1), 33–56.

Riccaboni, M., & Schiavo, S. (2010). Structure and growth of weighted networks. New Journal of Physics, 12(2), 023003.

Riccaboni, M., & Schiavo, S. (2014). Stochastic trade networks. Journal of Complex Networks, 2(4), 537–556.

Rodrik, D. (2004). Industrial policy for the twenty-first century. CEPR Discussion Paper, No. 4767.

Sgrignoli, P., Metulini, R., Schiavo, S., & Riccaboni, M. (2015). The relation between global migration and trade networks. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 417, 245–260.

Simon, H. A. (1955). On a class of skew distribution functions. Biometrika, 42(3/4), 425–440.

Simon, H. A., & Ijiri, Y. (1977). Skew distributions and the size of business firms. Amsterdam: North Holland.

Soramäki, K., Bech, M. L., Arnold, J., Glass, R. J., & Beyeler, W. E. (2007). The topology of interbank payment flows. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 379(1), 317–333.

Stiglitz, J. E., Lin, J. Y., & Monga, C. (2013). The rejuvenation of industrial policy. Policy Research Working Paper 6628, The World Bank.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by Banca Intesa San Paolo with a grant in memory of the late Prof. Ferdinando Targetti, first director of the School of International Studies at the University of Trento. The authors also acknowledge financial support received from the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research through the programs PRIN 2009 (Grant No. 2009Z3E2BF_002), Futuro in Ricerca 2012 (Grant RBFR12BA3Y), and the PNR (CRISIS Lab project).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: List of variables and their description

-

Initial income is GDP per capita at PPP (constant 2005 international $) in logarithm for the year 1995 which is the beginning of the period under consideration [source from World Development Indicators (WDI)].

-

GDP represents the size of the economy. It is total GDP amount in logarithm for each country at constant US$.

-

Country capabilities is calculated as in Hidalgo and Hausmann (2009) , \(k_{c,0} = \sum _{p} M_{cp}\) i.e. the diversification of country c as the sum of \(M_{cp}\) over all products p where \(M_{cp}\) = 1 if country c exports product p with a revealed comparative advantage above 1, \(M_{cp}\) = 0 otherwise. We use our own data and average the figure for each country.

-

Product ubiquity is also taken from Hidalgo and Hausmann (2009) and represents the pervasiveness of the products of a country, \(k_{p,0} = \sum _{c} M_{cp}\).

-

Betweenness centrality, following Jackson (2008), is defined as \(\sum \nolimits _{ij:i\ne j, k \not \in ij} \frac{P_{ij}(k)}{P_{ij}}\) where \(P_{ij}\) denotes the number of shortest paths from node i to j and \(P_{ij}(k)\) denotes the number of shortest paths from node i to j that node k lies on. It is a measure of the importance of a country based on its connections.

-

Clustering, where the clustering coefficient of a node is the probability that two randomly selected neighbours are connected to each other. The clustering coefficient \(C_{c}\) of node i, \(C_{c} ({\mathbf {A}}) = \frac{\sum \nolimits _{j\ne i; k\ne j; k\ne i} A_{ji} A_{ik} A_{jk} }{\sum \nolimits _{j\ne i; k\ne j; k\ne i} A_{ji} A_{ik} }\).

-

Private credit is credit from all financial institutions and sourced from the Financial Development and Structure Dataset, World Bank developed by Beck et al. (2000). The April 2013 version has been used. The variable is Private Credit by Deposit Money Banks and Other Financial Institutions to GDP (%) which is defined as claims on the private sector by deposit money banks and other financial institutions divided by GDP. As described in Beck and Demirguc-Kunt (2009), this asset side variable captures one of the most important function of financial intermediaries, that is, allocation of credit.

-

Tariffs is average tariff rate on manufactured products (%) (source WDI).

-

Start-up costs represents costs of business start-up procedures as a percentage of gross national income per capita (source WDI).

-

Export docs is simply the number of documents required per shipment to export goods such as documents required for clearance by government ministries, customs authorities, port and container terminal authorities, health and technical control agencies and banks are taken into account. It is an ease of doing business indicator.

-

Inflation is used to capture changes in the price level. It reflects annual percentage changes in consumer prices (source WDI).

-

Export/GDP is a standard indicator of openness to trade (source WDI).

-

Rule of law, percentile rank, is a World Governance Indicator, World Bank.

-

Telephones captures technological development (source WDI).

-

FDI is net inflows of Foreign Direct Investment in current US$ in logarithm (source WDI).

-

\({D^{Oil}}\) is a dummy variable capturing whether a country is a significant oil-producer, that is, its oil rents is more than 40 % of its GDP (source WDI).

-

\({D^{SSA}}\), \({D^{SA}}\), \({D^{NA}}\), \({D^{MENA}}\), \({D^{LAC}}\) and \({D^{EAP}}\) are regional dummy variables representing regions as per the WDI 7 regions classification, namely, Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, North America, Middle East and North Africa, Latin Ame and Caribbeans, East Asia Pacific.

-

Capital stock, investment and savings are capital stocks in billions constant 2005 $US, investment rate as a percentage of GDP, savings rate as a percentage of GDP respectively (source CEPII Econmap baseline database 2.1).

-

Pop. is population density (people per sq. km of land area) (source WDI).

-

Ki is the number of product–destinations in logarithm.

-

Agricultural and industrial empl. represent employment in the agricultural sector and employment in industry (% of total employment) respectively (source WDI).

-

Primary school and secondary school are years of primary schooling and secondary schooling for population aged 15 and over respectively (source Barro and Lee 2012).

-

Export volatility is the standard deviation in export growth from 1995 to 2005 (calculated using data from BACI database). All the variables are for the year 2005 except where specified above. To maximise the number of observations, where data was missing for the year 2005, averages of previous and successive years were used.

Appendix 2

See Table 8.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sufrauj, S.B., Schiavo, S. & Riccaboni, M. Big hits, export concentration and volatility. Econ Polit 32, 135–166 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-015-0014-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-015-0014-y