Abstract

This manuscript is a review of the preclinical and early clinical findings related to a unique fluorinated polyphosphazene nanolayer device surface modification. Polyzene-F (PzF) is a novel, high-molecular weight, highly pure polyphosphazene that was designed to enhance the biologic interface between a medical device surface and human tissue or blood. The polymer also has unique mechanical properties that for the first time allow implants to be paved with a coating that has a nanoscale thickness of < 50 nm. The coating has inherent thrombus resistant properties and takes on biomimetic properties soon after implant due to favorable protein adhesion. Over the last 1.5 decades, PzF has undergone extensive preclinical testing including benchtop endothelial cell migration and platelet adhesion studies followed by increasingly sophisticated evaluation in 16 different animal models. The coating consistently has shown reduced platelet adhesion, decreased clotting, reduced inflammation, and accelerated healing compared with different surfaces as well as uncoated controls. These preclinical findings have translated into early compelling clinical evidence that suggest enhanced healing and reduced thrombosis can be achieved with a PzF-coated implant. There are now two PzF nanocoated products approved by the US Food and Drug Association (FDA), embolic spheres, and a coronary stent. This is the first detailed overview of the history, preclinical findings, and current clinical results attributed to the PzF coating with emphasis on the coronary stent Cobra-PzF.

Lay Summary

Over the last few decades, we have seen remarkable advances in medical technology including the development of less invasive surgical alternatives for the treatment of heart and vascular disease. One of the key advances in treating or preventing heart attack, stroke, and limb loss has been the development of stents. Stents are small, metallic, mesh-like devices that can be expanded within blocked vessels via small catheters placed through the groin or wrist. These stents provide structural support while the vessel heals. One of the challenges with stents and other permanent device implants is related to how our bodies react to foreign materials. One of the most feared complications of stents is clotting, which can result in abrupt closure of the treated artery. In the case of heart stents, abrupt closure can cause a heart attack or even sudden death whereas clotting within stents in the neck arteries (carotids) can cause stroke. Additional normal body defense mechanisms include complicated immune responses that trigger inflammation and can cause scarring resulting in early recurrence of the blockage or so-called “restenosis.” In an effort to eliminate restenosis, many stents are now coated with drugs that slow or prevent healing. The downside of this approach has been the need for long-term blood-thinning medications like Plavix and aspirin. In this article, we review the history and current clinical findings of a new way to potentially make medical implants invisible to the normal foreign body defense responses that cause subsequent complications. The innovation involves the development of a new compound called Polyzene-F (CeloNova BioSciences, San Antonio, TX) that can be placed on the surface of a device in a layer that is extremely thin. This new coating is so thin it cannot be seen with even the strongest available microscopes and falls into a new category of material science called nanotechnology. Nanotechnology involves materials that are measured on a molecular level rather than the traditional measurements used in the field of medical devices. We describe many experiments done on the benchtop alongside animal studies and early clinical results that support the hypothesis that an enhanced biologic response can be expected for implants coated with Polyzene-F. The initial types of heart disease patients being studied with this new coated stent (Cobra-PzF) are those at high risk for bleeding since we know these patients are less tolerant of blood-thinning medicine. This initial narrow focus was selected based on the experience from our team and others suggesting animal studies do not always predict how humans respond to new treatments coupled with the knowledge that drug-eluting stents are getting better each day. We do see signals in the completed Cobra-PzF clinical trials that clotting and recurrence (restenosis) are low, but these studies do not directly compare this device to alternative stents in a type of study we call a “randomized trial.” There is an ongoing large randomized trial comparing the Polyzene-F nanocoated stent (Cobra PzF) with contemporary drug-eluting stents in patients at high risk for bleeding, which should complete enrollment in 2019. At the same time, the US FDA-approved Polyzene-F-coated microbeads (Embozene, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA) are being studied for the treatment of tumors and cancer. If an enhanced biologic response is proven in the ongoing randomized trials being conducted on the currently approved Polyzene-F-coated devices, then this new surface enhancement may have broader application for a variety of medical device implants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

We have witnessed unprecedented advances in the field of medical device innovation over the last 5 decades. With maturation of the field, the early focus on implant architecture and miniaturization has shifted to the challenge of optimizing implant interaction with living tissue on a cellular and molecular level. The cascade of chemical reactions, alongside the myriad of paracrine, cytokine, and cellular responses, triggered at the tissue-blood interface of an implanted device, is extremely complex. We set out to establish a surface that mimics normal tissue or imitates nature at a molecular level via nanolayer surface paving with a novel hybrid inorganic-organic polymer now known as Polyzene-F (CeloNova BioSciences, San Antonio, TX).

Polyzene-F (PzF) is a special polyphosphazene, poly [bis (trifluoroethoxy)phosphazene] (Fig. 1a), made with a proprietary polymerization process. The polymer has unique mechanical characteristics, namely high tensile strength and high elasticity, that allowed the development of a unique, predictable, homogenous implant coating that can be applied at nanoscale thickness of < 50 nm. To put the coating thickness into perspective, the PzF surface modification is not visible under a microscope and is less than the thickness of a cell wall. The polymer was developed to optimize the interface with blood proteins by preferential adsorption of albumin over fibrinogen through trifluoroethanol moieties and avoiding other organic branch chain substitutions on the inorganic backbone [1]. PzF-coated devices appear to take on biomimetic properties soon after implant as they are rapidly covered with albumin [2]. Furthermore, the adherent albumin seems to maintain structural integrity with reduced denaturation compared with other implant surfaces [2]. This latter benefit partly explains the lower inflammatory response seen in PzF-coated implants although there are also reduced inflammatory and clotting responses seen in the absence of albumin. The biomimetic properties gained soon after implant, in part, may explain the early clinical benefit seen in the first FDA-approved clinical applications of PzF-coated embolic beads [Embozene Embolic Microspheres—(Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA)] [3,4,5,6,7]. The second FDA-approved PzF-coated product is the Cobra PzF nanocoated coronary stent (CeloNova BioSciences, San Antonio, TX). The goal of this overview is to review the history, preclinical, and clinical findings of this new nanolayer coating with emphasis on the US FDA-approved PzF-coated coronary stent.

The structure of PzF and its effect on plasma protein adsorption. a The PzF backbone as a phosphonitrillic compound with trifluoroethoxy attachments. b Illustrates that surfaces modified with PzF proved most efficacious in minimizing fibrinogen adsorption (red bars) while maximizing human serum albumin (green bars) measured in arbitrary units. (Hydro, hydroxylated glass slides; APTMS, ((3-Aminopropyl)trimetoxysilane); Aldehyde, Glutaric Aldehyde; PMMA, poly(methyl methacrylate); and OTS, (Octadecyltrichlorosilane) [2]

History of Polyzene-F

PzF is the culmination of nearly 2 centuries of scientific discovery involving a class of compounds categorized as phosphazenes. Phosphazenes were discovered in 1834 and over the next few decades the chemical composition [PNCL2] and trimetric configuration were further defined [8,9,10]. It was Stokes [11] in 1895 who discovered the cyclic nature of the phosphazene trimer structure and was able to synthesize an inorganic rubber with heating. However, the compound was so sensitive to crosslinking and instability with heating, it was not until the mid-1960s when Allcock and Kugel [12] synthesized the 1st un-crosslinked, fully substituted, high molecular weight, poly [bis (trifluoroethoxy)phosphazene]. These new polyphosphazenes showed great promise but the ring-opening polymerization process was complex. The synthetic process failed to tightly regulate macromolecular characteristics and fell short in production consistency, namely in functional properties, structural irregularities, and synthetic by-products affecting degradation profile, making a cost-effective scalable model for commercial applications elusive [13, 14].

Some progress was made in polyphosphazene synthesis during the 70s and 80s bypassing the side chain macromolecular substitution process [15,16,17,18,19,20]. However, it was the work done by Dsidra Tur, Michael Grunze, and his team at the University of Heidelberg in the 90s that led to the development of PzF. This work culminated in development of the first medical grade Poly [bis (trifluoro-ethoxy)phosphazene] that, unlike the previous polyphosphazenes, was a very high molecular weight, low dispersity, and extremely pure compound. This newly discovered synthesis pathway allowed electron withdrawing of trifluoroethoxy groups that resulted in the ability to program into the polymer a negative surface energy and high dipole moment that enhanced biologic interface with tissue and blood. The resultant strongly hydrophobic compound also had the unique combination of high elasticity and high tensile strength.

PzF has undergone extensive preclinical testing since it was discovered over 15 years ago. The structural integrity of the coating, application techniques, and surface compatibility testing with various implant materials remain proprietary. However, selected testing analyzing the impact of the coating on clotting, platelet adhesion/activation, protein adhesion, and anti-inflammatory properties are summarized in Table 1. Additional background for the preclinical testing is provided below followed by a review of how this research has been translated into clinical trial results.

Characterization of Polyzene-F

Chemical Properties

The proprietary synthesis pathway for PzF enabled the development of the first polyphosphazene without significant hydroxyl group substitution. As a result, PzF has < 0.005% residual hydroxyl groups. The residual chlorine content is < 0.003%. The molecular weight is 10 to 25 × 106 with a polydispersity index of 1.1 to 1.4. The elongation to break is 700% and there is a high tensile strength of 196 MPa with a surprising elastic modulus of 90 MPa and surface potential of − 32.5 mV [21,22,23]. These characteristics result in very unique properties that are innate to the material at initial exposure to the biologic environment but also propagated by how circulating proteins behave on the surface.

Protein Adsorption

The molecular handshake between a foreign body surface and blood components generally starts within seconds as proteins begin to adhere to the surface. According to the “Vroman effect,” the more mobile proteins adsorb first. Those can later be replaced by larger, less mobile proteins [24]. The structure and type of adsorbed proteins on the implant surface contribute to the cellular response. We now know that fibrinogen triggers a negative cellular response with activation of inflammatory cells and platelets. In addition, the most abundant protein in the bloodstream, albumin, can send signals that incite inflammation and inflammatory cell adhesion when that protein becomes denatured [25]. Welle et al. [2] examined the adsorption of albumin and fibrinogen on various surface coatings including metal, metal oxide, and non-metal coatings when the surface is immersed in human plasma. The lowest amount of fibrinogen and the highest amount of albumin were observed on PzF modified surfaces (Fig. 1b). More importantly, the albumin attached to a PzF coating seems to avoid denaturing. These findings, among others, became the foundation for the hypothesis that the implanted devices coated with PzF would mimic nature and thus decrease inflammatory response, reduce platelet activation/clotting, enhance healing, and, in the example of a coronary stent, reduce restenosis.

In Vitro Findings

The hypothesis that PzF would reduce platelet adherence was supported by early studies with a porous PzF foil (note: the foil is 100 s times thicker than the PzF nanocoating and thus is visible under a microscope) stretched on a control [gold] metal surface. The PzF foil was prepped with multiple alternating slits and when stretched over the gold metal coupon, a pattern of covered and uncovered portions of gold substrate was achieved (Fig. 2a). The covered coupon was then immersed in platelet rich human plasma for 1 h. After rinsing in citrate buffer solution, the samples were fixed with formaldehyde solution and examined under the microscope showing remarkable sparing of the PzF covered portions from platelet adhesion (Fig. 2a) [26].

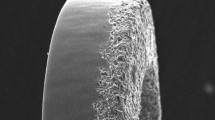

PzF displays anti-thrombotic properties. a PzF foil coating portions of a gold substrate. The portions coated by the Pzf foil sparsely adhere activated platelets compared with the uncovered gold substrate. b Control bare metal stent with visibly activated platelets (green area) as opposed to a PzF-coated stent with sparse platelet adherence. c Confocal microscopy (× 10 and × 20) and scanning electron microscopy (× 15 and × 200) images in a porcine ex vivo arteriovenous shunt model. The COBRA PzF NCS (green box) yielded the least thrombocyte adherence when compared with the COBRA BMS (blue box) and Vision BMS (red box). d Scanning electron microscopy images comparing a bare metal stent with a thick protein layer of fibrinogen, thrombocytes, and erythrocytes against the COBRA PzF NCS with a thin protein layer lacking clots or fibrin, instead supporting healthy endothelial cell growth [20, 29]

Furthermore, rapid endothelialization was anticipated as others have shown low concentrations of fibrinogen lead to rapid endothelialization [27]. In an in vitro experiment, human aortic endothelial cell migration on a 1 × 1 cm2 coupon under low and high shear stress flow was used to evaluate PzF-coated metal surfaces [28]. Within 14 days, the PzF-coated coupon was completely covered with endothelial cells. In a similar experiment, endothelial cell coverage was analyzed on stainless steel and cobalt-chromium stents (CoCr), both in uncoated and PzF-coated conditions. The migration speed under shear flow was 25 ± 0.8 μm/h for stainless steel stent and 21.4 ± 2.3 μm/h cobalt chromium CoCr (current preferred metal for coronary stents) while for the PzF-coated material, the speed increased to 25.9 ± 2.3 μm/h and 27.2 ± 2.6 μm/h respectively.

Ex Vivo and In Vivo Findings

Ex vivo and in vivo studies supported the anti-thrombotic properties shown during earlier in vitro analysis. In a canine ex vivo loop system, specifically placing a fistula between artery and vein containing different materials, adhered thrombotic mass was determined for different polymeric materials including PzF, Teflon, and polyethylene without anti-coagulant [29, 30]. PzF showed no thrombotic mass after 22 min, while polyethylene had more than 4500 μg/cm2.

Further animal studies have shown the PzF modified surface does not activate platelets and supports healthy endothelial cell growth without over expression (Fig. 2b, d). Subsequently, Richter et al. [31] compared the thrombo-resistance and non-inflammatory properties of PzF surface-modified stents with bare metal stents in a rabbit model. Statistically significant differences in thrombus occurrence were demonstrated. Results showed that surface modified stents were superior to bare metal stents regarding the prevention of stent thrombosis. Analysis for neointimal hyperplasia showed that the maximum neointimal hyperplasia of the PzF surface-modified stents was ~ 2.5 times lower than that of the non-surface modified stents supporting the hypothesis that enhanced healing may reduce restenosis [31].

In a porcine study by Satzl et al. [32], PzF-coated stents demonstrated superiority to bare metal stents at 3-month follow-up with regard to: (a) on-stent anti-thrombogenicity: no thrombus deposition; and statistically significant reduction in the percentage of average luminal diameter (ALD) and minimal luminal diameter (MLD), neointimal area, and luminal area, (b) reduction of late in-stent-restenosis: statistically significant reduction in the percentage of stenosis, (c) prevention of local and specific inflammation responses: statistically significant reduction in inflammatory score, and (d) nearly-complete endothelialization.

In comparison with control bare metal stents, PzF-coated stents placed in porcine renal and iliac vessels showed absent thrombus deposition versus thrombus on 2 of the 6 iliac stent controls at 4 weeks [33].

Late in-stent neointimal response in stainless steel bare metal stents was higher than the PzF surface-modified CoCr stents in a porcine coronary artery model [34]. There was no evidence of thrombus deposition on stents or target vessels throughout the entire study for Polyzene-F surface-modified stents. There were no occurrences of severe inflammation with granulomas on any of the tested stents.

A porcine ex vivo arteriovenous-shunt model was used to examine the thrombogenicity property of COBRA PzF Nanocoated Coronary Stent (NCS) System versus Cobra bare metal stents (BMS) and Vision BMS (Fig. 2c). It was shown that after explantation, no thrombus formation for the COBRA PzF NCS System was observed. In the SEM picture as well as the stained stent via light microscopy, very low amount of thrombotic mass can be seen in the COBRA PzF compared with significant mass on the Vision BMS (Fig. 2c) [35].

Further pre-clinical investigation supported the in vitro findings of rapid endothelialization as well as illustrating reductions in inflammation with Cobra PzF-coated stents. A pre-clinical study with nine New Zealand white rabbits, where 18 stents were implanted in the left and right ilio-femoral artery, showed excellent endothelialization for COBRA PzF NCS System after 14 days. The study aimed to assess endothelial cell coverage and inflammation in response to Cobra PzF-coated stents without drug in the rabbit compared with Synergy bioabsorbable polymer everolimus-eluting stent (EES) and Xience Xpedition permanent polymer EES after 14 days of implantation. Table 2 summaries the result for the endothelial cell coverage. The COBRA PzF NCS System had significantly better coverage of stent struts and in-between stent struts with endothelial cells compared with Synergy and Xience [36].

In a porcine coronary artery stent implantation model versus a Vision bare metal stent (24 animals), the neointimal growth for COBRA PzF NCS System was significantly lower than for a Vision BMS [35]. At 28 and 90 days, the neointimal thickness for COBRA PzF NCS System was 0.16 and 0.1 mm versus Vision BMS 0.33 and 0.22 respectively (Fig. 3). Even for overlapping stents, the neointimal thickness for COBRA PzF NCS System was by factor 3 thinner: 0.13 mm versus Vision BMS’ 0.39 mm.

Light microscopy findings from a porcine coronary model. a Compares COBRA PzF NCS against Vision BMS at 5-, 28-, and 90-days when implanted in normal porcine coronary arteries. The COBRA PzF NCS showed reduced neointimal growth and stenosis coupled with a significantly larger luminal area when compared against Vision BMS. b Proximal, middle, and distal cross-sections of porcine coronary arteries, illustrating lower incidence of granulomas and minimal inflammation in the COBRA PzF NCS when compared against Vision BMS. Low magnification images (× 2) were stained with Movat pentachrome staining and high magnification images (× 20) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining [29]

In the same pre-clinical study as above, with New Zealand white rabbits, the inflammation reaction was evaluated with a RAM11 marker for macrophages. On the COBRA PzF NCS System, the lowest number of macrophages was observed compared with Synergy and Xience stents. Cytokines also play an important role in coronary artery disease and are involved in interactions between different cell types, cellular responses to pathologic stimuli, and maintenance of homeostasis. Koppara et al. [35] showed in experiments with cultured monocytes that monocytes have a much lower ability to adhere and form multinucleated cells, particularly macrophages, on PzF-coated coupons (Fig. 4, panel a). Evaluation of cytokines in the cell medium including IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, and TNFα showed significantly lower amounts of inflammatory cytokines for the PzF-coated coupons (Fig. 4, panel b).

PzF exhibits reduced inflammation. a Cultured monocytes on a PzF-coated CoCr stent struggle to adhere and develop into multinucleated cells when compared with an uncoated CoCr stent. Monocytes were stained with Alexa Fluor® 546 Phalloidin (red), nuclear counterstained with DAPI (blue), and imaged by confocal microscopy (× 40). b Compares the concentration of inflammatory cytokines IL-10, IL-12, TNFα, and IL-4 on a PzF-coated CoCr stent against an uncoated CoCr stent. The PzF-coated CoCr stent showed significantly lower inflammatory cytokines (p < 0.01) [29]

Similar to the low inflammatory markers in the above study, a low inflammation score was found when the COBRA PzF NCS System was compared with a Vision bare metal stent implantation in porcine coronary artery after 28 days (Fig. 5) [37, 38]. No struts with granulomas were found for the COBRA PzF NCS System compared with the Vision bare metal stent. In addition, for a single stent and overlapping stents, the amount of struts with granuloma was zero compared with Vision bare metal stent. Additionally, the injury score was very low for the COBRA PzF NCS System in comparison with the Vision bare metal stent.

PzF exhibits anti-restenotic and anti-inflammatory effects. 28 days after single stent implantation in porcine coronary arteries, the COBRA PzF NCS (red bars) has significantly lower neointimal area and thickness as well as a lower injury score and granulomas on struts when compared against Vision BMS (blue bars).

Recently, the team at the CVPath Institute (Gaithersburg, Maryland) under the direction of Dr. Aloke Finn evaluated Cobra PzF versus conventional drug-eluting stents with respect to thrombogenicity and healing to assess suitability for short-term dual anti-platelet therapy (DAPT). In the porcine shunt model, the Cobra PzF showed less platelet aggregation than the bioabsorbable polymer drug-eluting stent (DES) and comparable findings to the durable polymer DES. Additional studies included analysis of vessel permeability utilizing a new method developed by CVPath that has not been reported previously. Utilizing these new methods via a 28-day in vivo rabbit iliac model, the endothelial coverage and barrier protein function were found to be superior in Cobra PzF relative to durable polymer DES, bioabsorbable polymer DES, and polymer free DES (Figs. 6 and 7). This latter finding is the first in vivo assessment of how different stent platforms affect subsequent uptake of large molecules into the cell wall which has many implications for healing and late neoatherosclerosis. In addition, the study showed via vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin complex and p120 staining statistically significant better endothelial coverage in the Cobra PzF stent compared with market-leading DES [36].

Results of 28 day in-life stent implantation in a rabbit model. Evans blue uptake across the COBRA PzF, Xience, Synergy, and BioFreedom stent systems (iii). The Evans blue uptake was significantly lower in the COBRA PzF compared with Xience and Synergy and favorable to BioFreedom. Confocal microscopy of each stent performing colocalization of VE-cadherin and p120 (ii) and scanning electron microscopy (i) enhanced at × 200 (a)(b) suggest Cobra PzF has a significantly higher endothelial coverage barrier protein above strut and higher endothelial coverage [36]

Quantification of 28 day in-life stent implantation results in a rabbit model. Cobra PzF had the least Evans blue uptake, most endothelial coverage barrier protein above strut, and most endothelial coverage in scanning electron microscopy above strut compared with Xience, Synergy, and BioFreedom [36]. The Evans blue uptake was significantly lower in the COBRA PzF compared with Xience and Synergy and favorable to BioFreedom. Confocal microscopy of each stent performing colocalization of VE-cadherin and p120 and scanning electron microscopy enhanced at × 200 suggest Cobra PzF has a significantly higher endothelial coverage barrier protein above strut and higher endothelial coverage [36]

Clinical Findings

More than 20,000 patients have been treated with PzF nanocoated stents and over 3000 patients have been evaluated in clinical trials. The first-generation stent, Catania PzF coronary stent, was introduced in Europe in 2008 while the recent generation COBRA PzF NCS underwent limited release in Europe in 2013 and in the USA in August of 2017. The human clinical trial experience is summarized in Table 3 and detailed below.

The first clinical outcomes with Catania PzF coronary stent were reported by Tamburino et al. [39, 40] in the first-in-man (ATLANTA-FIM) trial (n = 55) and subsequent ATLANTA II (n = 300). The late stent thrombosis (LST) which was 0% in the ATLANTA FIM and in ATLANTA II with no need for dual antiplatelet therapy beyond 30 days after the procedure. The 0% LST was also observed in the multicenter registry in France (n = 379) [41]. Clinically driven target lesion revascularization (TLR) at 12-months post-procedure was 3.6%, 6.5%, and 3.9% in ATLANTA FIM, ATLANTA II, and ATLANTA FR, respectively.

The first human experience with COBRA PzF NCS was reported by Maillard et al. [42]. Among 100 patients (71% men, mean age 71.4 ± 11.0 years), 38% had acute coronary syndromes. The population was consistent with real-world experience and included patients with multiple comorbidities including 26% with diffuse multi-vessel disease. One-year outcomes demonstrated 5% TLR and no cases of definite stent thrombosis.

Andersson et al. [43] reported on 103 high-risk individuals undergoing PCI with COBRA PzF NCS using the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR), the SCAAR is a 20-hospital registry developed to evaluate stent performance. At a mean follow-up of 10 months, clinically driven TLR was 3.9% and no clinical stent thrombosis was observed.

CeloNova Biosciences has sponsored three COBRA PzF clinical trials. The COBRA PzF Coronary Stent System in Native Coronary Arteries for Early Healing, Thrombus Inhibition, Endothelialization, and Avoiding Long-Term Dual Anti-Platelet Therapy (PzF SHIELD) (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01925794) study led to the approval of COBRA PzF in the USA. The PzF SHIELD Study was a non-randomized, multi-center, prospective, single arm, controlled clinical study conducted at 35 sites in the US and Europe [44]. Between August 2013 and February 2015, 296 patients were enrolled and treated with COBRA PzF stent. A high number, 34% of patients, were diabetics. Stent thrombosis at 9-months post-procedure was 0%, type 4c MI was 0.7% while clinically driven TLR was 4.6%.

The Safety and Effectiveness Evaluation of COBRA PzF Coronary Stent System: A Post Marketing Observational Registry (eCOBRA) (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03103620). The eCOBRA trial was a prospective, post market, multicenter registry for all comers’ patients undergoing PCI. A total of 940 patients were enrolled and implanted with COBRA PzF stents from 18 French centers. The 12-month primary endpoint results were presented at EuroPCR 2018, and subgroup analysis (STEMI and NSTEMI vs. stable and unstable angina) was presented at TCT 2018. The eCOBRA trial demonstrated a low rate of cardiac death (3.7%), Target Vessel-MI (1.8%), clinically driven TLR (4.3%), and a low rate of LST (0.3%). In the sub group analysis, 443 patients with STEMI and NSTEMI versus 497 with stable or unstable angina were compared. At 1 year, cardiac death was 5.0% vs 2.4% (p.0.04), MI 2.7% vs 3.8% (p.NS), LST 0.45% vs 0.2% (p.NS), and TLR 4.5% vs 3.4% (p.NS) in ACS and non ACS groups, respectively.

The Randomized Trial of COBRA PzF Stenting to Reduce Duration of Triple Therapy (COBRA-REDUCE) study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT0259450). COBRA REDUCE is ongoing. It is a prospective, 1:1 randomized, open-label assignment, assessor-blinded, active-controlled, multi-center study to evaluate the safety of the COBRA PzF stent with 2 weeks DAPT compared with drug-eluting stents with 3 or 6 months DAPT in patients on oral anticoagulant and undergoing PCI. This study will enroll 996 patients at 60 sites globally.

Conclusions

Extensive preclinical in vitro, in vivo, and ex vitro studies suggest devices covered with a nanolayer of PzF have favorable interactions with platelets and subsequent enhanced healing due to protein adhesion associated biomimetic properties. The reduction in clotting, decreased inflammatory response, and enhanced healing seems to be driven by the unique molecular architecture of the polymer and results in an improved interface with cellular, protein, cytokine, and paracrine responses at the implant surface. The first FDA-approved PzF-coated permanent implant (Embozene Embolic Spheres, Boston Scientific, Marlborough Mass, USA) also showed evidence of reduced inflammation which may be beneficial in reducing pain, part of post-embolic syndrome, after occlusion of hypervascular tumors [3]. The coronary stent was selected by PzF researchers as the next clinical target based on the hypothesis that the thrombo-resistant polymer characteristics could potentially address the issue of stent thrombosis and the need for long-term DAPT while the reduced inflammatory response may also enhance healing and reduce restenosis.

While the field of coronary intervention has matured over the last 3 decades, one of the remaining challenges is balancing the risk of accelerated neointimal growth within the stent, in-stent restenosis, and the inherent risk of using a drug coating to slow or halt healing. The former results in the need for repeat intervention while the latter is associated the potentially catastrophic risk of stent thrombosis. In reality, the unhealed DES is very similar to a vulnerable plaque and the binary shift from being widely patent to abrupt closure, without mature collaterals, is associated with a very high mortality [45]. On the other hand, recent data suggests that repeat intervention for in-stent restenosis is also associated with increased mortality, so the ideal solution remains elusive [46].

This new class of nanocoated stents with enhanced healing comes at a time when DES outcomes are improving. For example, the DES abrupt closure risk improved from 4.4 to 1.4% with newer drugs and polymer changes [47]. Recent DES designs have evolved to include bioabsorbable or even absent abluminal polymer drug delivery systems. Third generation DESs seem to have abrupt closure risks below 1% but often with the tradeoff of higher need for TLR, 3.5% in the polymer free DES study, or 5–6% in high-risk bleeding populations [48]. The Cobra PzF seems to have significantly narrowed the gap between DES and BMS with an intermediate solution that has an “all comers” TLR of 4.3% in a 940 patient registry and a TLR of 4.6% in the well-controlled US/OUS trial leading to FDA approval [44, 49].

If the Cobra PzF-associated low TLR rates and MACE continue to be confirmed in ongoing trials, then availability of this new class of stents raises many questions about future stent trial designs and comparative studies. The compelling pre-clinical work, reported herein, showing permeability of the endothelial barrier to large molecules with DES, raises questions about the long-term biologic impact of a widely porous endothelium during delayed DES healing, and how this may explain very late stenosis or occlusion from neo-atherosclerosis. In addition, the TLR risk seems to persist for DESs out to 3–5 years and this may not be the case for this new class of pro-healing stents. Therefore, would the earlier slightly higher TLR observed in Cobra PzF compared with some DESs balance out at 3 years since the neointimal process should generally be extinguished during the first year of the former? Will we need to reconsider the value of 1 year “late loss” as a surrogate for coronary stent efficacy? It is far too early in the clinical research stage of PzF enhanced healing to answer many of these questions; however, many will argue that the DES outcomes will continue to improve and some degree of harnessed healing will always be required.

As we consider the ideal larger trial design to address the provocative questions regarding pro-healing as an alternative to delayed or incomplete healing in a coronary artery, the current Cobra PzF clinical research focus is on a subgroup of patients that are at high risk of bleeding. Approximately, 10–15% of indicated coronary interventional cases are currently done in patients at high risk of bleeding including those with atrial fibrillation on oral anticoagulants [50,51,52]. These patients could benefit from a stent that prevents acute thrombus formation and accelerates healing. Based on the WOEST trial, these atrial fibrillation patients have prohibitive risk of bleeding following DES when placed on DAPT in addition to their needed anticoagulant, so-called “triple therapy.” A stent that reduces acute and subacute thrombotic risk, while also reducing restenosis, may have a significant advantage in the high bleeding-risk patient. Accordingly, the ongoing COBRA REDUCE trial will evaluate the safety and bleeding risk of 2 weeks DAPT in patients on oral anticoagulation compared with traditional antiplatelet regimen in the DES control group. This novel trial design addresses a huge unmet need as the 1st stent study with only 2 weeks DAPT since one-half of all major bleeding on triple therapy occurs in the 1st month after DES stent placement [53].

Irrespective of how the ongoing Cobra PzF trials progress it is clear that advanced material science research that includes expertise from many disciplines—material scientists, engineers, chemists, cardiovascular pathologists, clinicians, and cell biologists—will be the next frontier in device science innovation. The PzF coating may be applicable for other medical device implants but this will require additional study.

References

Welle A, Grunze M, Tur D. Blood compatibility of poly [bis (trifluoroethoxy) phosphazene]. JAMP. 2000;4(1):6–10.

Welle A, Grunze M, Tur D. Plasma protein adsorption and platelet adhesion on poly [bis (trifluoroethoxy)phosphazene] and reference material surfaces. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1998;197(2):263–74. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcis.1997.5238.

Richter G, Radeleff B, Stroszczynski C, Pereira P, Helmberger T, Barakat M, et al. Safety and feasibility of chemoembolization with doxorubicin-loaded small calibrated microspheres in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: results of the MIRACLE I prospective multicenter study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41(4):587–93.

Smeets AJ, Nijenhuis RJ, van Rooij WJ, Lampmann LE, Boekkooi PF, Vervest HA, et al. Embolization of uterine leiomyomas with polyzene f–coated hydrogel microspheres: initial experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21(12):1830–4.

Stampfl U, Radeleff B, Sommer C, Stampfl S, Dahlke A, Bellemann N, et al. Midterm results of uterine artery embolization using narrow-size calibrated embozene microspheres. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34(2):295–305.

Pisco JM, Duarte M, Bilhim T, Cirurgiao F, Oliveira AG. Pregnancy after uterine fibroid embolization. Fertility and sterility. 2011;95(3):1121.e5–8.

Bonomo G, Pedicini V, Monfardini L, Della Vigna P, Poretti D, Orgera G, et al. Bland embolization in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma using precise, tightly size-calibrated, anti-inflammatory microparticles: first clinical experience and one-year follow-up. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33(3):552–9.

Rose H. Ueber eine Verbindung des Phosphors mit dem Stickstoff. Ann Pharm. 1834;11(2):129–39.

Von Liebig J. Über Phosphorstickstoff. J Liebigs Ann Chem. 1834;11:139.

Gladstone JH, Holmes J. XXVII.—On chlorophosphuret of nitrogen, and its products of decomposition. J Chem Soc. 1864;17:225–37.

Stokes H. Properties of phosphorus nitrides. Ame Chem Soc J. 1895;17:275–80.

Allcock H, Kugel R. Synthesis of high polymeric alkoxy-and aryloxyphosphonitriles. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87(18):4216–7.

Andrianov AK, Chen J, LeGolvan MP. Poly(dichlorophosphazene) as a precursor for biologically active polyphosphazenes: synthesis, characterization, and stabilization. Macromolecules. 2004;37(2):414–20. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma0355655.

Andrianov AK, Svirkin YY, LeGolvan MP. Synthesis and biologically relevant properties of polyphosphazene polyacids. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5(5):1999–2006. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm049745d.

Allcock H, Patterson D. Phosphorus-nitrogen compounds. 27. Ring-ring and ring-chain equilibration of dimethylphosphazenes. Relation to phosphazene polymerization. Inorg Chem. 1977;16(1):197–200.

Allcock HR, Patterson DB, Evans TL. Synthesis of alkyl and aryl phosphazene high polymers. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99(18):6095–6.

Allcock H, Schmutz J, Kosydar KM. A new route for poly (organophosphazene) synthesis. Polymerization, copolymerization, and ring-ring equilibration of trifluoroethoxy-and chloro-substituted cyclotriphosphazenes1, 2. Macromolecules. 1978;11(1):179–86.

Flindt E-P, Rose H. Trivalent-pentavalent phosphorus compounds—phosphazenes. I. A New method for preparation of poly[bis(trifluorethoxy)-phosphazenes]. Z Anorg Allg Chem. 1977;428(1):204–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.19774280125.

Wisian-Neilson P, Neilson RH. Poly (dimethylphosphazene),(Me2PN) n. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102(8):2848–9.

Neilson RH, Wisian-Neilson P. Poly (alkyl/arylphosphazenes) and their precursors. Chem Rev. 1988;88(3):541–62.

Magill J. Poly(phosphazene), semicrystalline. In: Mark JE, editor. Polymer data handbook. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. p. 1018.

Starannikova L, Tur D, Teplyakov V, Plate N. Gas separation properties of polyBis(Trifluoroethoxyphosphazene). Vysokomol Soedin Ser A. 1994;36(11):1906–11.

Fritz U. Ph.D. Thesis: University of Heidelberg; 2006.

Lavery KS, Rhodes C, Mcgraw A, Eppihimer MJ. Anti-thrombotic technologies for medical devices. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;112:2–11.

Brash JL. Exploiting the current paradigm of blood–material interactions for the rational design of blood-compatible materials. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2000;11(11):1135–46.

Gries CR. [Doctoral dissertation]: University of Heidelberg; 2001.

Ahmed Z, Underwood S, Brown R. Low concentrations of fibrinogen increase cell migration speed on fibronectin/fibrinogen composite cables. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2000;46(1):6–16.

Sprague EA, Luo J, Palmaz JC. Human aortic endothelial cell migration onto stent surfaces under static and flow conditions. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1997;8(1):83–92.

Tur D, Koršak V, Vinogradova S, Dobrova N, Novikova S, Il'ina M, et al. Investigation of the thermostability of poly [bis (trifluoroethoxy) phosphazene]. Acta Polym. 1985;36(11):627–31.

Vinogradova SV, Tur DR, Vasnev VA. Open-chain poly (organophosphazenes). Synthesis and properties. Russ Chem Rev. 1998;67(6):515–34.

Richter GM, Stampfl U, Stampfl S, Rehnitz C, Holler S, Schnabel P, et al. A new polymer concept for coating of vascular stents using PTFEP (poly bis (trifluoroethoxy) phosphazene) to reduce thrombogenicity and late in-stent stenosis. Investig Radiol. 2005;40(4):210–8.

Satzl S, Henn C, Christoph P, Kurz P, Stampfl U, Stampfl S, et al. The efficacy of nanoscale poly [bis (trifluoroethoxy) phosphazene](PTFEP) coatings in reducing thrombogenicity and late in-stent stenosis in a porcine coronary artery model. Investig Radiol. 2007;42(5):303–11.

Henn C, Satzl S, Christoph P, Kurz P, Radeleff B, Stampfl U, et al. Efficacy of a polyphosphazene nanocoat in reducing thrombogenicity, in-stent stenosis, and inflammatory response in porcine renal and iliac artery stents. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19(3):427–37.

Stampfl U, Sommer C-M, Thierjung H, Stampfl S, Lopez-Benitez R, Radeleff B, et al. Reduction of late in-stent stenosis in a porcine coronary artery model by cobalt chromium stents with a nanocoat of polyphosphazene (Polyzene-F). Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31(6):1184–92.

Koppara T, Sakakura K, Pacheco E, Cheng Q, Zhao X, Acampado E, et al. Preclinical evaluation of a novel polyphosphazene surface modified stent. Int J Cardiol. 2016;222:217–25.

Jinnouchi H, Mori H, Cheng Q, Kutyna M, Torii S, Sakamoto A et al. Thromboresistance and functional healing in the COBRA PzF stent versus competitor DES: implications for dual anti-platelet therapy. EuroIntervention. 2018. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJ-D-18-00740

Sakakura K, Cheng Q, Otsuka F, Yahagi K, Barakat M, Ren J, et al. TCT-806 thrombogenicity of novel polyphosphazene surface-modified coronary stent compared to standard bare metal stent in swine shunt model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(18 Supplement 1):B244–B5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.1559.

Sakakura KPE, Nakano M, Otsuka F, Barakat M, Ren J, Kolodgie F, et al. Improved arterial healing in response to a novel polyphosphazene surface-modified stent in swine. Paris: EuroPCR; 2013.

Tamburino C, Capodanno D, Di Salvo ME, Sanfilippo A, Cascone I, Incardona V, et al. Safety and effectiveness of the Catania Polyzene-F coated stent in real world clinical practice: 12-month results from the ATLANTA 2 registry. EuroIntervention. 2012;7(9):1062–8.

Tamburino C, La Manna A, Di Salvo ME, Sacchetta G, Capodanno D, Mehran R, et al. First-in-man 1-year clinical outcomes of the Catania coronary stent system with Nanothin Polyzene-F in de novo native coronary artery lesions: the ATLANTA (Assessment of The LAtest Non-Thrombogenic Angioplasty stent) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2009;2(3):197–204.

Teiger SC E, Mouillet G, Armangaud J, Gharib S, Faure JP, Al-Amry H, et al. Incidence of thromboembolic events in patients treated with stent coated with anti-thrombotic and anti-inflammatory polymer: interim analysis of an observational multinational study in France and Middle East. Paris: EuroPCR; 2011.

Maillard L, Tavildari A, Barra N, Billé J, Joly P, Peycher P, et al. Immediate and 1-year follow-up with the novel nanosurface modified COBRA PzF stent. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;110(12):682–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acvd.2017.04.010.

Andersson JNJ, Strandh A. Clinical experiences from nanothin Polyzene-F coated coronary stents in a high-risk population. Paris: EuroPCR; 2016.

Cutlip DE, Garratt KN, Novack V, Barakat M, Meraj P, Maillard L, et al. 9-month clinical and angiographic outcomes of the COBRA Polyzene-F nanocoated coronary stent system. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(2):160–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2016.10.037.

Claessen BE, Henriques JPS, Jaffer FA, Mehran R, Piek JJ, Dangas GD. Stent thrombosis: a clinical perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2014;7(10):1081–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2014.05.016.

Palmerini T, Della Riva D, Biondi-Zoccai G, Leon MB, Serruys PW, Smits PC et al. Mortality following nonemergent, uncomplicated target lesion revascularization after percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2018

Räber L, Magro M, Stefanini GG, Kalesan B, van Domburg RT, Onuma Y et al. Very late coronary stent thrombosis of a newer-generation everolimus-eluting stent compared with early-generation drug-eluting stents: a prospective cohort study. Circulation. 2012;125(9):1110–21.

Jensen LO. A randomized trial comparing a polymer-free coronary drug-eluting stent with an ultra-thin strut bioresorbable polymer-based drug-eluting stent in an all-comers patient population. San Diego: TCT; 2018.

Maillard LBL, Faurie B, Brasselet C, Durel N, Depoli F, Berland J, et al. One-year results of the e-Cobra registry: 1,027 all-comer, consecutive, prospective, high-risk patients treated with the Cobra PzF nanocoated coronary stent (NCS). Paris: EuroPCR; 2018.

Morice M-C, Urban P, Greene S, Schuler G, Chevalier B. Why are we still using coronary bare-metal stents? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(10):1122–3.

Urban P, Meredith IT, Abizaid A, Pocock SJ, Carrié D, Naber C, et al. Polymer-free drug-coated coronary stents in patients at high bleeding risk. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(21):2038–47.

Krukoff M. Prospective randomized comparison of the bioFreedom biolimus A9 drug-coated stent versus the Gazelle bare-metal stent in patients at high bleeding risk II - LEADERS FREE II. TCT; September 22; San Diego, USA 2018.

Dewilde WJ, Oirbans T, Verheugt FW, Kelder JC, De Smet BJ, Herrman J-P, et al. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9872):1107–15.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to pioneering scientists who led the way on inventing and optimizing PzF. Drs. Dsidra Tur, Michael Grunze, Ulf Fritz, and the team at the University Heidelberg led the way on developing the polymer and programming in the biomimetic properties reported herein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Mark C. Bates, MD: patent holder, shareholder, and CeloNova board member; Lee Sun, PhD, Mark Barakat, MD, and Alexander Kueller, PhD are CeloNova employees and have stock options in the company. Ahmed Yousaf has nothing to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bates, M.C., Yousaf, A., Sun, L. et al. Translational Research and Early Favorable Clinical Results of a Novel Polyphosphazene (Polyzene-F) Nanocoating. Regen. Eng. Transl. Med. 5, 341–353 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40883-019-00097-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40883-019-00097-3