Abstract

We suggest the necessary/sufficient criteria for existence of a (order-by-order) solution \({y}({x})\) of a functional equation \(F({x},{y})=0\) over a ring. In full generality, the criteria hold in the category of filtered groups, this includes the wide class of modules over (commutative, associative) rings. The classical Implicit Function Theorem and its strengthening obtained by Tougeron and Fisher appear to be (weaker) particular forms of the general criterion. We obtain a special criterion for solvability of equations arising from group actions \(g(w)=w+u\), here u is “small”. As an immediate application we re-derive the classical criteria of determinacy, in terms of the tangent space to the orbit. Finally, we prove the Artin–Tougeron-type approximation theorem: if a system of \(C^\infty \)-equations has a formal solution and the derivative satisfies a Lojasiewicz-type condition then the system has a \(C^\infty \)-solution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

All rings in this paper are commutative, associative, with unit element, of zero characteristic. We use the multivariable notation \({x}=(x_1,\ldots ,x_m)\), \({y}=(y_1,\ldots ,y_n)\).

1.1 General setting and known results

Consider a system of (analytic/formal/\(C^\infty \)/\(C^k\)) equations \(F({x},{y})=0\). The classical Implicit Function Theorem reads: If the matrix of derivatives,

, is right invertible (i.e. is of the full rank) then

\(F({x},{y})=0\)

has a (analytic/formal/etc.) solution.

, is right invertible (i.e. is of the full rank) then

\(F({x},{y})=0\)

has a (analytic/formal/etc.) solution.

The condition “ is right invertible” is quite restrictive. For example, the theorem does not ensure a solution of the one-variable equation \(xy=0\) (in the vicinity of (0, 0)) or of \(y^2=0\) (at any point).

is right invertible” is quite restrictive. For example, the theorem does not ensure a solution of the one-variable equation \(xy=0\) (in the vicinity of (0, 0)) or of \(y^2=0\) (at any point).

Various strengthenings/generalizations of this theorem are known (including the Hensel lemma). For example, the Tougeron Implicit Function Theorem ensures solvability when the matrix  is not too degenerate. Denote by

is not too degenerate. Denote by  the ideal of the maximal minors of this matrix.

the ideal of the maximal minors of this matrix.

Theorem 1.1

([29], [30, p. 56]) Let  or

or  (for \(\Bbbk \) a normed field) or

(for \(\Bbbk \) a normed field) or  . Let \(F({x},{y})\in R^{\oplus p}\), \(p\leqslant n\), and let \(I\subset R\) be a proper ideal. If

. Let \(F({x},{y})\in R^{\oplus p}\), \(p\leqslant n\), and let \(I\subset R\) be a proper ideal. If  then there exists a solution \(F({x},{y}({x}))\equiv 0\) such that

then there exists a solution \(F({x},{y}({x}))\equiv 0\) such that  .

.

While this theorem ensures the solution of \(yx=0\) and \(y^2=0\), it fails to ensure a solution of the system

Here \(F(x,0)=x^3\left( {\begin{array}{c}1\\ 1\end{array}}\right) \),  , thus

, thus  .

.

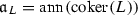

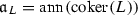

It was noticed by Tougeron [28] that one can replace in the condition  the ideal

the ideal  by a larger ideal,

by a larger ideal,

the annihilator of the cokernel of the morphism

. Some properties of this ideal are recalled in Sect. 2.3. By now we just mention that for \(p=1\), i.e. the case of one equation, the two ideals coincide:

. Some properties of this ideal are recalled in Sect. 2.3. By now we just mention that for \(p=1\), i.e. the case of one equation, the two ideals coincide:  .

.

The statement was further strengthened by Fisher, he replaced one of the factors in \(({\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{{y}}({x},0)})^2\) by the image  . (The initial version was for p-adic rings, we give a more general version relevant to our context.)

. (The initial version was for p-adic rings, we give a more general version relevant to our context.)

Theorem 1.2

([10]) Let \((R,{\mathfrak {m}})\) be a local Henselian ring over a field of zero characteristic. Let  . Suppose

. Suppose

Then there exists a solution \(F({x},{y}({x}))\equiv 0\) such that  .

.

In the case of one equation, \(p=1\), this coincides with Tougeron’s result. For \(p>1\), Fisher’s result is stronger. (Note that  , and for \(p>1\) the inclusion is in general proper.)

, and for \(p>1\) the inclusion is in general proper.)

Though Fisher’s version solves the examples mentioned above, it cannot cope with a slightly more complicated example

where  and \(g(x_1,x_2)\in {\mathfrak {m}}^{2k+1}\) for \(k>2\). Here

and \(g(x_1,x_2)\in {\mathfrak {m}}^{2k+1}\) for \(k>2\). Here

thus in general  , i.e. condition (1) is not satisfied.

, i.e. condition (1) is not satisfied.

1.2 Overview of results

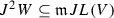

Our work has began from the observation that Fisher’s condition can be further weakened: instead of  it is enough to ask for

it is enough to ask for  , where \({\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{y}({x},0)}\subseteq J\subset R\) is the biggest possible ideal satisfying

, where \({\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{y}({x},0)}\subseteq J\subset R\) is the biggest possible ideal satisfying  . (See Corollary 3.17 and Sect. 4.1 for more detail.) This gives further strengthening of Fisher’s and Tougeron’s statements. Still, this strengthening does not help to address the very simple system (cf. Sect. 4.1)

. (See Corollary 3.17 and Sect. 4.1 for more detail.) This gives further strengthening of Fisher’s and Tougeron’s statements. Still, this strengthening does not help to address the very simple system (cf. Sect. 4.1)

Here \({\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{y}}=(x_1x_2)\) thus \(J=(x_1x_2)\), but  .

.

In this note we prove much stronger solvability criteria. In this introduction we sketch just the main features of the method. The detailed formulation can be found in Sect. 3.1 (Theorem 2.1) and Sect. 5 (Theorem 5.3), the applications are in Sects. 4 and 6.

We weaken the condition on  further, to the “weakest possible” condition of “iff” type, so that we get a Strong Implicit Function Theorem.

further, to the “weakest possible” condition of “iff” type, so that we get a Strong Implicit Function Theorem.

Our results hold in broader category. It is natural to extend from the classical case of  ,

,  ,

,  to the local Henselian rings (not necessarily regular or Noetherian) over a field. In fact even the ring structure is not necessary, our main result, Theorem 2.1, is true for filtered (not necessarily abelian) groups.

to the local Henselian rings (not necessarily regular or Noetherian) over a field. In fact even the ring structure is not necessary, our main result, Theorem 2.1, is true for filtered (not necessarily abelian) groups.

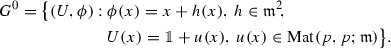

A particular class of equations comes from the group actions  . Assume W is a filtered abelian group (e.g. a module over a local ring). To understand how large the orbit is one studies the equation \(g(w)=w+u\). Here \(g\in G\) is an unknown, while \(u\in W\) is “small”. (More precisely, one studies whether the orbit Gw is open in the topology defined by a filtration.) Theorem 2.1, being very general, is of little use here. Rather, we obtain a special version of strong IFT, Sect. 3.1.2.

. Assume W is a filtered abelian group (e.g. a module over a local ring). To understand how large the orbit is one studies the equation \(g(w)=w+u\). Here \(g\in G\) is an unknown, while \(u\in W\) is “small”. (More precisely, one studies whether the orbit Gw is open in the topology defined by a filtration.) Theorem 2.1, being very general, is of little use here. Rather, we obtain a special version of strong IFT, Sect. 3.1.2.

Usually the main problem is to establish the order-by-order solution procedure. Thus many of our results are of the form: If

then there exists a Cauchy sequence

\(\{{y}^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}({x})\}_n\)

such that

\(F({x},{y}^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}({x}))\rightarrow 0\)

. (The topology here is induced by a filtration, e.g. by the powers of maximal ideal.)

then there exists a Cauchy sequence

\(\{{y}^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}({x})\}_n\)

such that

\(F({x},{y}^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}({x}))\rightarrow 0\)

. (The topology here is induced by a filtration, e.g. by the powers of maximal ideal.)

Once such a result is established, one has a solution in the completion of \(R^{\oplus p}\) by the filtration. Then (if R is non-complete) one uses the Artin-type approximation theorems [18] to establish a solution over R, or at least over the henselization of R.

For the ring \(C^\infty ({\mathbb {R}}^p\!,0)\) and many other important rings the Artin approximation does not hold (in the naive way). Over some rings we can directly ensure a solution, see Sect. 3.4. For \(C^\infty ({\mathbb {R}}^p\!,0)\) we use Theorem 5.3.

1.3 Comments and motivation

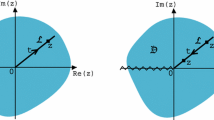

Several remarks/explanations are necessary at this point. Recall the simple geometric interpretation. Consider the (germ of) subscheme/subspace  . The classical IFT, in the case when (X, 0) and (Y, 0) are smooth, gives a sufficient condition that the germ

. The classical IFT, in the case when (X, 0) and (Y, 0) are smooth, gives a sufficient condition that the germ  is smooth and its projection onto (X, 0) is an isomorphism.

is smooth and its projection onto (X, 0) is an isomorphism.

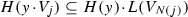

Our version of IFT, for arbitrary Henselian germs (X, 0), (Y, 0), gives a necessary and sufficient condition that the germ  has an irreducible component whose projection onto (X, 0) is an isomorphism. This can be restated as follows. Consider the natural projection

has an irreducible component whose projection onto (X, 0) is an isomorphism. This can be restated as follows. Consider the natural projection  . Usually this projection is not an isomorphism. The solvability of the equation means the weaker property: the existence of the section of \(\pi \),

. Usually this projection is not an isomorphism. The solvability of the equation means the weaker property: the existence of the section of \(\pi \),  .

.

To emphasize: as the germ  is in general non-smooth (possibly reducible, non-reduced), the question cannot be simply “linearized” by an automorphism of

is in general non-smooth (possibly reducible, non-reduced), the question cannot be simply “linearized” by an automorphism of  , i.e. cannot be reduced to the classical IFT by some appropriate change of variables.

, i.e. cannot be reduced to the classical IFT by some appropriate change of variables.

A reformulation in terms of commutative algebra reads: Given a ring R over some base ring \(R_X\), e.g.  or

or  , etc. Given an ideal \(F=\)

\((F_1,\dots ,F_p)\subset R\), a solution of \(F({x},{y})=0\) is a projection

, etc. Given an ideal \(F=\)

\((F_1,\dots ,F_p)\subset R\), a solution of \(F({x},{y})=0\) is a projection  whose kernel is precisely F.

whose kernel is precisely F.

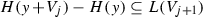

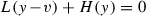

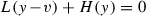

The classical approach to construct a solution is the order-by-order approximation: first solve the part linear in \({y}\) (modulo quadratic terms), then quadratic, cubic, etc. Accordingly, we always present the equation(s) \(F({x},{y})=0\) in the form \({u}+L{y}+H({y})=0\in W\). Here \({u}=F({x},0)\in W\),  is a homomorphism of R-modules (or just of abelian groups); \(H({y})\) denotes the remaining “higher order terms” (a contractive map in the sense of Krull topology), defined in Sect. 2.2.

is a homomorphism of R-modules (or just of abelian groups); \(H({y})\) denotes the remaining “higher order terms” (a contractive map in the sense of Krull topology), defined in Sect. 2.2.

Further, as we always start from a solution of the linear part, \({u}+L{y}=0\), we assume \({u}\in L(V)\), i.e.  for some \({v}\in V\). Therefore the equation to solve is presented in the form

for some \({v}\in V\). Therefore the equation to solve is presented in the form

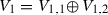

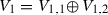

In practice one usually needs not just a solution. Thinking of \({v}\) as a parameter, one needs a statement of the type:

There exists a subgroup/submodule \(V_1\subseteq V\) such that for any \({v}\in V_1\) the equation \(L({y}-{v})+H({y})=0\) has a solution \({y}_{v}\in V_1\) which is “close” to \({v}\) and depends on \({v}\) “differentiably”. We call this a good solution, the precise formulation see in Sect. 2.2. Our criteria answer the question:

Question 1.3

Given  , what is the biggest \(V_1\subseteq V\) such that for any \(v\in V_1\) there exists a good solution?

, what is the biggest \(V_1\subseteq V\) such that for any \(v\in V_1\) there exists a good solution?

Note that for some equations all solutions are “not good”, cf. Sect. 4.3.

If the number of unknowns equals the number of equations and  is non-degenerate, then the classical IFT ensures the unique solution. When

is non-degenerate, then the classical IFT ensures the unique solution. When  is degenerate the solution (if it exists) can be non-unique, as the space

is degenerate the solution (if it exists) can be non-unique, as the space  can have several irreducible components. However, when L is injective, the solution lying in \(V_1\) is unique! The (non-)uniqueness issues are addressed in Sect. 3.3.

can have several irreducible components. However, when L is injective, the solution lying in \(V_1\) is unique! The (non-)uniqueness issues are addressed in Sect. 3.3.

We expand \(F({x},{y})=0\) in powers of \({y}\) (i.e. at \({y}=0\)), hence the criteria are formulated in terms of  , etc. One can expand at some other point, \({y}=y^{\scriptscriptstyle (0)}({x})\), then the criteria are written in terms of

, etc. One can expand at some other point, \({y}=y^{\scriptscriptstyle (0)}({x})\), then the criteria are written in terms of  , etc. (For example, Theorem 1.2 is stated in [10] in such a form.) Such an expansion at \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (0)}({x})\) is helpful if one has a good initial approximation for the solution. The two approaches are obviously equivalent, e.g. by changing the variable \({y}\mapsto {y}-y^{\scriptscriptstyle (0)}({x})\). To avoid cumbersome formulas we always expand at \({y}=0\).

, etc. (For example, Theorem 1.2 is stated in [10] in such a form.) Such an expansion at \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (0)}({x})\) is helpful if one has a good initial approximation for the solution. The two approaches are obviously equivalent, e.g. by changing the variable \({y}\mapsto {y}-y^{\scriptscriptstyle (0)}({x})\). To avoid cumbersome formulas we always expand at \({y}=0\).

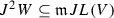

In view of our initial result, Sect. 1.2, one might try to weaken the condition on the ideal \({\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{y}({x},0)}\subseteq J\subset R\) further. It appears that \(J^2=J{\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{y}({x},0)}\) is almost the “weakest possible” among the conditions stated in terms of ideals only, it cannot be significantly weakened, cf. Sect. 4.2. But this condition is still far from being necessary. The “right” condition (necessary and sufficient) is obtained by replacing the ideals with filtered subgroups. As a bonus we do not need the rings structure anymore, e.g. Theorem 2.1 holds in the generality of (not necessarily abelian) filtered groups.

If the equations \(F({x},{y})=0\) are linear in \({y}\), i.e.  , then the obvious sufficient condition for solvability is: the entries of \(F({x},0)\) lie in the ideal \({\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{{y}}({x},0)}\). While the (tautological) necessary and sufficient condition is:

, then the obvious sufficient condition for solvability is: the entries of \(F({x},0)\) lie in the ideal \({\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{{y}}({x},0)}\). While the (tautological) necessary and sufficient condition is:  . This condition is much weaker than those of Tougeron and Fisher and is far from being sufficient for non-linear equations. Therefore as landmarks for our criteria one should consider equations that are non-linear in

\({y}\)

.

. This condition is much weaker than those of Tougeron and Fisher and is far from being sufficient for non-linear equations. Therefore as landmarks for our criteria one should consider equations that are non-linear in

\({y}\)

.

The Implicit Function Theorem is a fundamental result. In Sect. 4.4 we obtain an immediate corollary to non-bifurcation of multiple polynomial roots under deformations. In Sect. 4.5 we indicate a potential application to the study of smooth curve-germs (lines/arcs) on singular spaces. In Sect. 6.3 we apply a version of strong IFT to group-actions to re-derive the classical criteria of finite determinacy.

Further directions in algebra and geometry are: matrix equations, equations on (filtered) groups [3], tactile maps [6], bounds on Artin–Greenberg functions [23, 24], etc. We hope to report on these applications soon.

2 Definitions and notations

2.1 Groups with descending filtration

We always assume that a (not necessarily abelian) group V is filtered by a sequence of normal subgroups \(V\supset V_1\supset V_2\supset \cdots \),  . Moreover, we assume that the filtration satisfies the condition \([V_1,V_i]\subseteq V_{i+1}\), similarly to the lower central series of a group. This later condition is trivial when V is an abelian group. If V is complete with respect to \(\{V_i\}\) then the filtration is faithful, i.e.

. Moreover, we assume that the filtration satisfies the condition \([V_1,V_i]\subseteq V_{i+1}\), similarly to the lower central series of a group. This later condition is trivial when V is an abelian group. If V is complete with respect to \(\{V_i\}\) then the filtration is faithful, i.e.  . The filtration induces the Krull topology, the fundamental system of neighborhoods of \(v\in V\) is

. The filtration induces the Krull topology, the fundamental system of neighborhoods of \(v\in V\) is  , or

, or  , by normality.

, by normality.

Example 2.1

-

(a)

The simplest case is when V is a module over a ring, with filtration defined by the powers of an ideal

.

. -

(b)

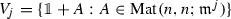

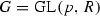

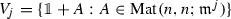

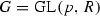

Let \((R,{\mathfrak {m}})\) be a local ring with the filtration \(R\supset {\mathfrak {m}}\supset {\mathfrak {m}}^{2}\supset \cdots \). Consider the group of invertible R-matrices

. We get the filtration by normal subgroups

. We get the filtration by normal subgroups  .

. -

(c)

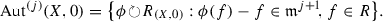

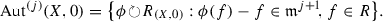

Let (X, 0) be the germ of a space (algebraic/formal/analytic etc). Consider the group of its automorphisms

. The natural filtration is by the subgroups of automorphisms that are identity up to j’th order. More precisely, denote by \((R_{(X,0)},{\mathfrak {m}})\) the local ring of (germs of) regular functions. Then

. The natural filtration is by the subgroups of automorphisms that are identity up to j’th order. More precisely, denote by \((R_{(X,0)},{\mathfrak {m}})\) the local ring of (germs of) regular functions. Then

2.2 Implicit function equation

Given two (not necessarily abelian) groups V, W, a homomorphism  , and a decreasing filtration

, and a decreasing filtration  by normal subgroups, we define the filtration

by normal subgroups, we define the filtration  on W. Consider the equation

on W. Consider the equation  , where the “higher order” map

, where the “higher order” map  , usually not a homomorphism, is such that

, usually not a homomorphism, is such that

-

\(H({{\mathbbm {1}}}_V)={{\mathbbm {1}}}_W\),

-

for any \(y\in V_1\) and \(j\in {\mathbb {N}}\).

for any \(y\in V_1\) and \(j\in {\mathbb {N}}\).

Note that being of higher order depends essentially on L, in particular,  .

.

If V, W are abelian groups, then the implicit function equation is  , where

, where  , while the higher order \(H({y})\) satisfies \(H(0_V)=0_W\) and

, while the higher order \(H({y})\) satisfies \(H(0_V)=0_W\) and  for any \(y\in V_1\) and j.

for any \(y\in V_1\) and j.

The most common case is when V, W are modules over a (commutative, associative) ring R. Then usually \(L\in \mathrm{Hom}_R(V,W)\). We say that the map  is of order \(\geqslant k\) if for any ideal \(J\subset R\) there holds

is of order \(\geqslant k\) if for any ideal \(J\subset R\) there holds  .

.

Example 2.2

Suppose R is graded, fix an ideal \(J\subset R\) and consider the filtration  . Suppose H(y) can be written as a sum of homogeneous forms \(H(y)=\sum _{i\geqslant k} h_i(y)\), the degree of \(h_i(y)\) being i. If \(L(V)\supseteq J^{k-2}W\) then H(y) is a “higher order” term for L. Indeed, for any \(i\geqslant k\) and

. Suppose H(y) can be written as a sum of homogeneous forms \(H(y)=\sum _{i\geqslant k} h_i(y)\), the degree of \(h_i(y)\) being i. If \(L(V)\supseteq J^{k-2}W\) then H(y) is a “higher order” term for L. Indeed, for any \(i\geqslant k\) and  ,

,

Example 2.3

(Warning) Being of higher order terms can be a restrictive condition. For example, in the equation \(y^2-yx+x^a=0\) the monomial \(y^2\) represents the higher order term for the filtration  only if \(a\geqslant 3\). Otherwise the condition \(H(V_1)\subseteq L(V_2)\) is not satisfied.

only if \(a\geqslant 3\). Otherwise the condition \(H(V_1)\subseteq L(V_2)\) is not satisfied.

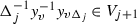

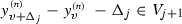

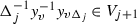

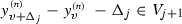

An order-by-order solution of the equation  is a Cauchy sequence \(\{y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\}_{n\geqslant 1}\) with respect to the filtration \(V_\bullet \), i.e.

is a Cauchy sequence \(\{y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\}_{n\geqslant 1}\) with respect to the filtration \(V_\bullet \), i.e.  , such that \(L(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)})\)

\(H(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)})L({v})^{-1}\in L(V_n)\) . By normality

, such that \(L(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)})\)

\(H(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)})L({v})^{-1}\in L(V_n)\) . By normality  , we can also write the condition as \((y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n+1)}){}^{-1}y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\in V_n\) or

, we can also write the condition as \((y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n+1)}){}^{-1}y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\in V_n\) or  .

.

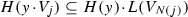

We say that the equation  admits a good solution on

\(V_1\) if there exists a map

admits a good solution on

\(V_1\) if there exists a map  satisfying the following conditions (we denote \({y}(v)\) by \({y}_v\), i.e. consider v as a parameter):

satisfying the following conditions (we denote \({y}(v)\) by \({y}_v\), i.e. consider v as a parameter):

-

for any \({v}\in V_1\);

for any \({v}\in V_1\); -

\({y}_{{{\mathbbm {1}}}_V}={{\mathbbm {1}}}_V\) and y respects the filtration, \(y(V_i)\subseteq V_i\) (this is a strengthening of continuity);

-

the map \({y}\) is “differentiable and close to identity”, namely,

, where the map

, where the map  is such that

is such that  for any \(v\in V_1\) and \(j\in {\mathbb {N}}\). Alternatively this condition can be stated as

for any \(v\in V_1\) and \(j\in {\mathbb {N}}\). Alternatively this condition can be stated as  for any

for any  . By normality, this is equivalent to

. By normality, this is equivalent to  .

.

We say that a solution  is quasi-good if

is quasi-good if  , where

, where  . Good implies quasi-good.

. Good implies quasi-good.

Combining these notions, we get the notion of a good order-by-order solution, i.e. a Cauchy sequence of maps  with

with

-

\(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_{{{\mathbbm {1}}}_V}={{\mathbbm {1}}}_V\),

,

, -

for all \(n,j\geqslant 1\) and

for all \(n,j\geqslant 1\) and  .

.

Similarly, a quasi-good order-by-order solution satisfies  , where

, where  .

.

If V, W are abelian groups then all notions simplify accordingly. A good order-by-order solution means a Cauchy sequence of maps  satisfying the conditions:

satisfying the conditions:

-

\(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_{{v}}\;-y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n+1)}_{{v}}\in V_n\), \(L(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_{{v}}\;-{v})+H(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_{{v}})\in L(V_n)\),

-

for all \(n,j\geqslant 1\) and

for all \(n,j\geqslant 1\) and  .

.

2.3 Annihilator of cokernel

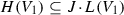

Consider a homomorphism of finitely generated R-modules  . Its image L(V) is an R-submodule of W. Its cokernel

. Its image L(V) is an R-submodule of W. Its cokernel  is an R-module as well. The annihilator-of-cokernel ideal is defined as the support of the cokernel module

is an R-module as well. The annihilator-of-cokernel ideal is defined as the support of the cokernel module

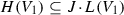

Recall the classical relation [9, Proposition 20.7]: for \(L\in \mathrm{Mat}(m,n;R)\) with \(m\leqslant n\) there holds \({\mathfrak {a}}_L\supseteq I_m(L)\supseteq ({\mathfrak {a}}_L)^m\). (Here \(I_m(L)=I_{\max }(L)\) is the ideal of the maximal, i.e.  , minors.) In particular, for \(m=1\), \({\mathfrak {a}}_L=I_1(L)\), the ideal is generated by all entries of L.

, minors.) In particular, for \(m=1\), \({\mathfrak {a}}_L=I_1(L)\), the ideal is generated by all entries of L.

By definition, \({\mathfrak {a}}_L W\subseteq L(V)\). In many cases one has a stronger property:  for some proper ideal \(J\subsetneq R\).

for some proper ideal \(J\subsetneq R\).

Example 2.4

Let  , \(1<m\leqslant n\), and suppose \({\mathfrak {a}}_L=I_{\max }(L)\), e.g. this holds when \(I_{\max }(L)\) is radical. Then \({\mathfrak {a}}_L W\subseteq J^{m-1} L(V)\).

, \(1<m\leqslant n\), and suppose \({\mathfrak {a}}_L=I_{\max }(L)\), e.g. this holds when \(I_{\max }(L)\) is radical. Then \({\mathfrak {a}}_L W\subseteq J^{m-1} L(V)\).

The embedding  does not hold only in some degenerate cases. For example, let \(L=\left( {\begin{matrix} f&{}0\\ 0&{}L_1\end{matrix}}\right) \), where \(\det L_1=f\). Then \({\mathfrak {a}}_L=(f)\) and

does not hold only in some degenerate cases. For example, let \(L=\left( {\begin{matrix} f&{}0\\ 0&{}L_1\end{matrix}}\right) \), where \(\det L_1=f\). Then \({\mathfrak {a}}_L=(f)\) and  .

.

3 Main results: criteria of solvability

3.1 General statements

Let  be a homorphism of (arbitrary) groups, where V is filtered by normal subgroups as in Sect. 2.1. Consider the equation

be a homorphism of (arbitrary) groups, where V is filtered by normal subgroups as in Sect. 2.1. Consider the equation  . See Sect. 2.2 for definitions.

. See Sect. 2.2 for definitions.

Theorem 2.1

-

(i)

If the map

represents the “higher order terms”, i.e.

represents the “higher order terms”, i.e.  for any \(y\in V_1\), \(j\in {\mathbb {N}}\), then there exists a quasi-good order-by-order solution

for any \(y\in V_1\), \(j\in {\mathbb {N}}\), then there exists a quasi-good order-by-order solution  . If moreover L admits a right inverse, i.e. there exists a map

. If moreover L admits a right inverse, i.e. there exists a map  such that

such that  , \(T(L(V_i))\subseteq V_i\), then there exists a good order-by-order solution.

, \(T(L(V_i))\subseteq V_i\), then there exists a good order-by-order solution. -

(ii)

Suppose

is compatible with the filtration in the sense

is compatible with the filtration in the sense  for some N(j), \(\lim _{j\rightarrow \infty }N(j)=\infty \). If there exists a good order-by-order solution

for some N(j), \(\lim _{j\rightarrow \infty }N(j)=\infty \). If there exists a good order-by-order solution  , then H represents the “higher order terms”, i.e.

, then H represents the “higher order terms”, i.e.  for any \(y\in V_1\), \(j\in {\mathbb {N}}\).

for any \(y\in V_1\), \(j\in {\mathbb {N}}\). -

(iii)

If V is complete with respect to \(V_\bullet \) and H represents the “higher order terms” then there exists a quasi-good solution

. If moreover L admits a right inverse, then there exists a good solution.

. If moreover L admits a right inverse, then there exists a good solution.

Proof

(i) First we construct a quasi-good order-by-order solution \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\). The procedure is inductive with non-canonical choices. If L is right invertible then all choices are canonical and the solution becomes good.

Note that \(H(V_{i})\subseteq L(V_{i+1})\), cf. Sect. 2.2. Fix some \(v\in V_i\), we construct inductively \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\) such that \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n+1)}(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)})^{-1}\in V_{i+n}\) and  .

.

Choose  and note that

and note that  . Suppose

. Suppose  have been constructed for some \(n\geqslant 1\). We shall look for \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n+1)}\) in the form \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n+1)}=zy^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\), so we should find the necessary \(z\in V_{i+n}\). Note

have been constructed for some \(n\geqslant 1\). We shall look for \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n+1)}\) in the form \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n+1)}=zy^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\), so we should find the necessary \(z\in V_{i+n}\). Note

By the induction assumption \(w\in L(V_{i+n})\), thus we choose \(z\in V_{i+n}\) such that \(L(z)=w^{-1}\). (If w is the identity element of W then we choose \(z={{\mathbbm {1}}}_V\).) Then equation (3) reads

This completes the induction step. (Here we use the normality  .)

.)

By construction, \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\) is a Cauchy sequence, as  . And if \(v={{\mathbbm {1}}}_V\) then \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}={{\mathbbm {1}}}_V\). Moreover, if \(v\in V_i\) then

. And if \(v={{\mathbbm {1}}}_V\) then \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}={{\mathbbm {1}}}_V\). Moreover, if \(v\in V_i\) then  . Thus \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\) is a quasi-good order-by-order solution.

. Thus \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\) is a quasi-good order-by-order solution.

Suppose there exists a continuous right inverse T,  , then in equation (3) we choose

, then in equation (3) we choose  . The proof of

. The proof of  goes by induction on n. For \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (1)}_{v}=v\) the statement is trivial. Suppose this holds for \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_{v}\). Then

goes by induction on n. For \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (1)}_{v}=v\) the statement is trivial. Suppose this holds for \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_{v}\). Then

Note that  , thus

, thus

Now, by normality  , we have

, we have

which, by normality  , equals

, equals

Finally, by induction, this space is  , and, by the property of filtration,

, and, by the property of filtration,  , the last expression is

, the last expression is  .

.

(ii) We proceed in two steps. In Step 1 we prove that a good order-by-order solution is an almost surjective map, its image is dense. In Step 2 we use this auxiliary statement to bound  .

.

Step 1. We prove the following auxiliary statement: If

is a good map, i.e.

\(y_v=v g(v)\)

with

is a good map, i.e.

\(y_v=v g(v)\)

with

, then the image of

y

is dense in

\(V_1\), i.e. for any

\(v\in V_1\)

there exists a sequence

\(v^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\in V_1\)

such that

, then the image of

y

is dense in

\(V_1\), i.e. for any

\(v\in V_1\)

there exists a sequence

\(v^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\in V_1\)

such that

.

.

Define  . Suppose \(v^{\scriptscriptstyle (1)}\!,\ldots ,v^{\scriptscriptstyle (i)}\) have been constructed, so that

. Suppose \(v^{\scriptscriptstyle (1)}\!,\ldots ,v^{\scriptscriptstyle (i)}\) have been constructed, so that  , i.e.

, i.e.  . Define

. Define  . Now the direct check gives

. Now the direct check gives

i.e. \(v^{\scriptscriptstyle (i+1)}\) satisfies the needed condition.

Step 2. Fix some good order-by-order solution  ,

,  . We should bound

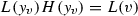

. We should bound  for any \(y\in V_1\),

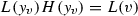

for any \(y\in V_1\),  . By (a) we can assume \(L(y)\in L(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_{v} V_{n+1})\) for some \(v\in V_1\) and \(n>j\). Moreover, we can choose n so large that in addition \(L(y\Delta _j)\in L\bigl (y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_{v\widetilde{\Delta _j}} V_{n+1}\bigr )\) for some

. By (a) we can assume \(L(y)\in L(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_{v} V_{n+1})\) for some \(v\in V_1\) and \(n>j\). Moreover, we can choose n so large that in addition \(L(y\Delta _j)\in L\bigl (y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_{v\widetilde{\Delta _j}} V_{n+1}\bigr )\) for some  . Now use

. Now use  and choose n so large that

and choose n so large that  and

and  . Therefore, for \(n>j\),

. Therefore, for \(n>j\),

In the second row we used the goodness of \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_{v}\).

(iii) If V is complete with respect to \(V_\bullet \) then  . Given the Cauchy sequence \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\) from (i), take the limit

. Given the Cauchy sequence \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}\) from (i), take the limit  . Then one has

. Then one has

\(\square \)

Remark 2.2

To emphasize, this theorem is almost an ‘iff’ statement, thus the assumptions on L, H are the “weakest possible”.

3.1.1 The case of abelian groups

One often needs results of such type for abelian groups, where one solves the equation  . We state the corresponding criterion separately.

. We state the corresponding criterion separately.

Corollary 3.3

-

(i)

Given abelian groups V, W and a homomorphism

. Suppose there exists a decreasing filtration \(V_\bullet \) of V such that for all \({y}\in V_1\) and \(j\geqslant 1\),

. Suppose there exists a decreasing filtration \(V_\bullet \) of V such that for all \({y}\in V_1\) and \(j\geqslant 1\),  . Then for any \({v}\in V_1\) there exists a quasi-good order-by-order solution.

. Then for any \({v}\in V_1\) there exists a quasi-good order-by-order solution. -

(ii)

If V is complete with respect to \(V_\bullet \) then the conditions

imply a quasi-good solution of the equation \(L({y}-{v})+H({y})=0\).

imply a quasi-good solution of the equation \(L({y}-{v})+H({y})=0\).

Remark 3.4

In the classical case of the equation \(F({x},{y})=0\) one requires that the map  is right invertible, i.e. surjective. Our criterion demands that \(F'_{y}({x},0)(V_{j+1})\) contains the variation of the higher order terms

is right invertible, i.e. surjective. Our criterion demands that \(F'_{y}({x},0)(V_{j+1})\) contains the variation of the higher order terms  , here

, here  .

.

3.1.2 A special version for group-action equations

Given two maps of (not necessarily abelian) groups  . Suppose W is filtered by normal subgroups

. Suppose W is filtered by normal subgroups  and F(V) contains \({{\mathbbm {1}}}_W\in W\). (Here we do not assume that L is a homomorphism.) Denote by \(\overline{L(V)},\overline{F(V)}\subseteq W\) the closures with respect to the filtration \(W_i\). The following statement is almost tautological, yet highly useful in Sect. 6.

and F(V) contains \({{\mathbbm {1}}}_W\in W\). (Here we do not assume that L is a homomorphism.) Denote by \(\overline{L(V)},\overline{F(V)}\subseteq W\) the closures with respect to the filtration \(W_i\). The following statement is almost tautological, yet highly useful in Sect. 6.

Lemma 3.5

Suppose  for any \(j\geqslant k\). If \(W_k\subset \overline{L(V)}\) then \(W_k\subseteq \overline{F(V)}\).

for any \(j\geqslant k\). If \(W_k\subset \overline{L(V)}\) then \(W_k\subseteq \overline{F(V)}\).

In the abelian case the condition reads  .

.

Proof

Suppose \(W_k\subseteq L(V)\), then  for any \(j\geqslant k\). Thus

for any \(j\geqslant k\). Thus  . As F(V) contains \({{\mathbbm {1}}}_W\in W\) we get

. As F(V) contains \({{\mathbbm {1}}}_W\in W\) we get  for any N. Which is precisely \(W_k\subseteq \overline{F(V)}\).

for any N. Which is precisely \(W_k\subseteq \overline{F(V)}\).

The general case. Let \(N>k\), consider the quotient  . Denote the composition maps

. Denote the composition maps  by \(\pi _N L, \pi _N F\). Then \(W_k\subset \overline{L(V)}\) implies \(\pi _N(W_k)\subseteq \pi _N L(V)\) for any N. By the previous paragraph we get \(\pi _N(W_k)\subseteq \pi _N F(V)\). Thus

by \(\pi _N L, \pi _N F\). Then \(W_k\subset \overline{L(V)}\) implies \(\pi _N(W_k)\subseteq \pi _N L(V)\) for any N. By the previous paragraph we get \(\pi _N(W_k)\subseteq \pi _N F(V)\). Thus  for any N, which means \(W_k\subseteq \overline{F(V)}\). \(\square \)

for any N, which means \(W_k\subseteq \overline{F(V)}\). \(\square \)

3.2 Criteria for modules over the rings

Theorem 2.1 and Corollary 3.3 transform the solvability question into the search for an appropriate filtration \(V_\bullet \). Not much can be said for a general (non)abelian group. However, our criterion simplifies for modules over a ring: it is enough to find just the first submodule \(V_1\subset V\) and an ideal.

Let R be a (commutative, associative) ring over a domain \(\Bbbk \) of zero characteristic (e.g. \(\Bbbk \) is a field). Given two R-modules and a homomorphism \(L\in \mathrm{Hom}_R(V,W)\). Suppose further that the term \(H({y})\) admits a “linear approximation with the remainder in the form of Lagrange”, i.e.

here \(H_1({y})(z)\) is linear in z while \(H_2({y},\Delta )(z,z)\) is quadratic in z.

Example 3.6

Such an approximation holds e.g. for R a subring of one of the quotients  .

.

Corollary 3.7

Fix some ideal \(J\subset R\) and a submodule \(V_1\subset V\). Under the assumptions as above we have:

-

(a)

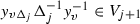

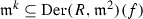

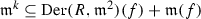

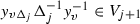

If the equation

admits a good order-by-order solution for the filtration \(\{V_i=J^{i-1}V_1\}\) then

admits a good order-by-order solution for the filtration \(\{V_i=J^{i-1}V_1\}\) then  .

. -

(b)

If

then

then  admits a quasi-good order-by-order solution for the filtration \(\{V_i=J^{i-1}V_1\}\). (If L is right invertible then there exists a good order-by-order solution.)

admits a quasi-good order-by-order solution for the filtration \(\{V_i=J^{i-1}V_1\}\). (If L is right invertible then there exists a good order-by-order solution.)

Proof

(a) By Theorem 2.1, the existence of a good solution implies  and hence

and hence  .

.

(b) For any \(t\in \Bbbk \), \(\Delta \in V_1\) we have  . Thus

. Thus  for \(t\in \Bbbk \). Then

for \(t\in \Bbbk \). Then  and \(H_2({y},t\Delta )\)

and \(H_2({y},t\Delta )\)

. Thus

. Thus  and

and  . Thus

. Thus  is implied by

is implied by  . Now invoke Corollary 3.3 for the filtration \(\{V_i=J^{i-1}V_1\}\). \(\square \)

. Now invoke Corollary 3.3 for the filtration \(\{V_i=J^{i-1}V_1\}\). \(\square \)

Corollary 3.7 reduces the question (for modules over a ring) to the search for an appropriate submodule \(V_1\subset V\). The simplest submodule is  for some ideal \(J\subset R\).

for some ideal \(J\subset R\).

Corollary 3.8

Suppose H(y) has the linear approximation as in equation (4), and moreover H(y) is of order \(k\geqslant 2\), i.e.  . If

. If  then there exists a quasi-good order-by-order solution

then there exists a quasi-good order-by-order solution  with respect to the filtration

with respect to the filtration  .

.

(Proof: Apply Corollary 3.7 for the filtration  .)

.)

Example 3.9

Given the equation  , where H is of order k as above.

, where H is of order k as above.

-

(a)

Consider the annihilator of cokernel ideal

, cf. Sect. 2.3. If

, cf. Sect. 2.3. If  then there exists a good (order-by-order) solution

then there exists a good (order-by-order) solution  . Also, a bit weaker form: if

. Also, a bit weaker form: if  then there exists a good (order-by-order) solution

then there exists a good (order-by-order) solution  .

.In the lowest order case, \(k=2\), we get a sufficient condition for the order-by-order solvability:

. This condition is weaker than Tougeron’s and Fisher’s conditions, so even this criterion is stronger.

. This condition is weaker than Tougeron’s and Fisher’s conditions, so even this criterion is stronger. -

(b)

Quite often

, cf. Sect. 2.3. Then we get a stronger statement: if

, cf. Sect. 2.3. Then we get a stronger statement: if  then there exists a good (order-by-order) solution

then there exists a good (order-by-order) solution  .

.

3.2.1 Ideals that satisfy \(J^2\subseteq J{\mathfrak {a}}_L\)

(These are important in view of Example 3.9.) Consider the set \(\mathfrak {J}\) of all ideals satisfying \(J^2\subseteq J{\mathfrak {a}}_L\). This is an inductive set, i.e. for any increasing sequence \(J_1\subseteq J_2\subseteq \cdots \) the union  is an ideal such that \(J^2\subseteq J{\mathfrak {a}}_L\). (If

is an ideal such that \(J^2\subseteq J{\mathfrak {a}}_L\). (If  then \(f,g\in J_k\) for some \(k<\infty \), thus \(fg,f+g\in J_k\).) Therefore in \(\mathfrak {J}\) there exist(s) ideal(s) that is/are maximal by inclusion.

then \(f,g\in J_k\) for some \(k<\infty \), thus \(fg,f+g\in J_k\).) Therefore in \(\mathfrak {J}\) there exist(s) ideal(s) that is/are maximal by inclusion.

Lemma 3.10

Let \(J\subset R\) be a maximal by inclusion ideal that satisfies \(J^2\subseteq J{\mathfrak {a}}_L\).

-

(i)

\({\mathfrak {a}}_L\subseteq J\). If the ideal J is finitely generated then \(J\subseteq \overline{{\mathfrak {a}}_{L}}\). (Here \(\overline{{\mathfrak {a}}_{L}}\) is the integral closure.)

-

(ii)

If \({\mathfrak {a}}_L\) is radical then \(J={\mathfrak {a}}_L\). If R is integrally closed and \({\mathfrak {a}}_L\) is principal, generated by a non-zero divisor, then \(J={\mathfrak {a}}_L\).

Proof

(i) If \(J^2\subseteq J{\mathfrak {a}}_L\) then obviously the inclusion is satisfied by the ideal \(J+{\mathfrak {a}}_L\) as well. As J is the largest with this property, \({\mathfrak {a}}_L\subseteq J\). For the second part, note that \({\mathfrak {a}}_L\) is a reduction of J, see [17, Definition 1.2.1], thus \(J\subseteq \overline{{\mathfrak {a}}_{L}}\) by [17, Corollary 1.2.5].

(ii) If \(J^2\subseteq J{\mathfrak {a}}_L\) then in particular \(J^2\subset {\mathfrak {a}}_L\). Then, \({\mathfrak {a}}_L\) being radical, we get \(J\subseteq {\mathfrak {a}}_L\). Hence together with (i) we get \(J={\mathfrak {a}}_L\). The second part follows from [17, Proposition 1.5.2]: in our case \(\overline{{\mathfrak {a}}_{L}}={\mathfrak {a}}_L\). \(\square \)

Example 3.11

In many cases \({\mathfrak {a}}_L\subsetneq J\subsetneq \overline{{\mathfrak {a}}_{L}}\) and a maximal by inclusion ideal J is non-unique. For example, let  and

and  . Then \({\mathfrak {a}}_L=(x^p,y^p,z^p)\) while \(\overline{{\mathfrak {a}}_{L}}={\mathfrak {m}}^p\). Define \(J_z=((x,y)^p,z^p)\), \(J_y=((x,z)^p,y^p)\), \(J_x=((y,z)^p,x^p)\). By a direct check, each of them satisfies \(J^2=J{\mathfrak {a}}_L\). But there is no bigger ideal J that contains say \(J_x+J_y\) and satisfies \(J^2=J{\mathfrak {a}}_L\). Indeed, suppose \(y^{p-i}z^{i}\in J\) and \(x^{p-j}z^{j}\in J\), for some i, j satisfying \(i+j<p\). Then \(J{\mathfrak {a}}_L=J^2\ni x^{p-j}y^{p-i}z^{i+j}\), in particular \(x^{p-j}y^{p-i}z^{i+j} \in {\mathfrak {a}}_L\), \(i+j<p\), contradicting the definition of \({\mathfrak {a}}_L\). Thus, in this case there are at least three distinct maximal by inclusion ideals.

. Then \({\mathfrak {a}}_L=(x^p,y^p,z^p)\) while \(\overline{{\mathfrak {a}}_{L}}={\mathfrak {m}}^p\). Define \(J_z=((x,y)^p,z^p)\), \(J_y=((x,z)^p,y^p)\), \(J_x=((y,z)^p,x^p)\). By a direct check, each of them satisfies \(J^2=J{\mathfrak {a}}_L\). But there is no bigger ideal J that contains say \(J_x+J_y\) and satisfies \(J^2=J{\mathfrak {a}}_L\). Indeed, suppose \(y^{p-i}z^{i}\in J\) and \(x^{p-j}z^{j}\in J\), for some i, j satisfying \(i+j<p\). Then \(J{\mathfrak {a}}_L=J^2\ni x^{p-j}y^{p-i}z^{i+j}\), in particular \(x^{p-j}y^{p-i}z^{i+j} \in {\mathfrak {a}}_L\), \(i+j<p\), contradicting the definition of \({\mathfrak {a}}_L\). Thus, in this case there are at least three distinct maximal by inclusion ideals.

3.3 (Non-)Uniqueness

The classical Implicit Function Theorem ensures the uniqueness of solution, provided \(F'_{y}(0,0)\) is injective. In our case the injectivity ensures that the solution is “eventually unique” in the following sense.

Proposition 3.12

Given two order-by-order-solutions \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_1\!, y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_2\) of the equation  . Suppose

. Suppose  and L is injective. Then for any n,

and L is injective. Then for any n,  .

.

Proof

By the assumption  . Suppose the statement holds for \(j=1,\dots ,n-1\). As both \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_i\) are Cauchy sequences, we get

. Suppose the statement holds for \(j=1,\dots ,n-1\). As both \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_i\) are Cauchy sequences, we get  . We shall prove that in fact

. We shall prove that in fact  .

.

As each \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_i\) is an order-by-order-solution, we have  . Thus

. Thus

By normality  , we get

, we get

Now use  and the property of higher order terms for H to get

and the property of higher order terms for H to get  . Therefore, \(L((y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_2)^{-1}y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_1)\in L(V_n)\) and the statement follows by the injectivity of L. \(\square \)

. Therefore, \(L((y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_2)^{-1}y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)}_1)\in L(V_n)\) and the statement follows by the injectivity of L. \(\square \)

Remark 3.13

The assumption \(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (1)}_1\!, y^{\scriptscriptstyle (1)}_2\in V_1\) is important. One might seek for a condition in terms of \({v}\) and L only, then it is natural to ask whether \({v}\) belongs to a small enough subgroup of V. For example, in the case of modules, \(v\in JV\), for some small enough ideal \(J\subset R\). This does not suffice as one sees already in the example of one equation in one variable \((y-x^a)(y+x^b)=0\). Suppose \(a<b\), then \({\mathfrak {a}}_L=(x^a)\), while \(v\in (x^{a+b})\). By taking \(b\gg a\) the ideal \((x)^{a+b}\) can be made arbitrarily small as compared to \({\mathfrak {a}}_L\). Yet, there is no uniqueness.

Remark 3.14

If L is non-injective then there can be no uniqueness. Even the images \(L(y^{\scriptscriptstyle (n)})\) of an order-by-order-solution are not “eventually unique”. As the simplest example consider the equation \(y^2_1+y^2_2-y_1+v=0\), where  . We have a family of solutions \(y_1=2(v+y^2_2)/\bigl (1+\sqrt{1-4(v+y^2_2)}\bigr )\), here \(y_2\) is a parameter. By taking \(y_2\in (v^j)\) these solutions can be made arbitrarily close one to the other (in particular they all lie in \(V_1\)), yet \(L(y_1,y_2)\) is different for different \(y_2\).

. We have a family of solutions \(y_1=2(v+y^2_2)/\bigl (1+\sqrt{1-4(v+y^2_2)}\bigr )\), here \(y_2\) is a parameter. By taking \(y_2\in (v^j)\) these solutions can be made arbitrarily close one to the other (in particular they all lie in \(V_1\)), yet \(L(y_1,y_2)\) is different for different \(y_2\).

3.4 A criterion for exact solutions

The criteria of Sect. 3.1 provide order-by-order solutions, alternatively, solutions in the completion of V by \(V_\bullet \), i.e. the formal solutions. Recall the Artin approximation property: if a finite system of polynomial equations over R has a solution over \(\widehat{R}\) then it has a solution over R [1, 2]. Many rings have this approximation property, e.g. excellent Henselian rings (in particular complete rings, analytic rings), cf. [16].

In our case we have more general rings and more general class of equations. Thus we give a criterion for exact (and not just order-by-order) solutions.

Fix some proper ideal \(J\subsetneq R\). The pair (R, J) is said to satisfy the (classical) Implicit Function Theorem, denote this by  , if for any surjective morphism of free R-modules of finite ranks

, if for any surjective morphism of free R-modules of finite ranks  , any

, any  and any “higher order term”

and any “higher order term”  , the equation

, the equation  has a good solution. Note that if R satisfies

has a good solution. Note that if R satisfies  then for any ideal \(J_1\subseteq J\) the ring satisfies

then for any ideal \(J_1\subseteq J\) the ring satisfies  as well.

as well.

Example 3.15

Let \((R,{\mathfrak {m}})\) be any local Henselian ring over a field \(\Bbbk \). For example, the ring of formal power series  , the ring of analytical power series

, the ring of analytical power series  (for \(\Bbbk \)-normed), the ring of smooth functions

(for \(\Bbbk \)-normed), the ring of smooth functions  or the ring of p-times differentiable functions

or the ring of p-times differentiable functions  . Then \((R,{\mathfrak {m}})\) satisfies \(\mathrm{cIFT}_{\mathfrak {m}}\).

. Then \((R,{\mathfrak {m}})\) satisfies \(\mathrm{cIFT}_{\mathfrak {m}}\).

The rings  ,

,  do not satisfy \(\mathrm{cIFT}_{\mathfrak {m}}\), e.g. the equation \(y^2+y=x^2\) is not solvable over these rings.

do not satisfy \(\mathrm{cIFT}_{\mathfrak {m}}\), e.g. the equation \(y^2+y=x^2\) is not solvable over these rings.

We say that (R, J) satisfies the Implicit Function Theorem with unit linear part, denote this by  , if the system of equations \({y}-{v}+H({y})=0\) has a good solution,

, if the system of equations \({y}-{v}+H({y})=0\) has a good solution,  , for any higher order terms H.

, for any higher order terms H.

This system is a particular case of the classical implicit function equations. Therefore the Henselian rings (over a field) of Example 3.15 satisfy \(\mathrm{IFT}_{{\mathfrak {m}}\!,{\mathbbm {1}}}\). Note that the condition  is weaker than

is weaker than  . For example,

. For example,  is satisfied by

is satisfied by  ,

,  for \(J=({x})\). More generally, one can take as \(\Bbbk \) any ring and as R a Henselian algebra over \(\Bbbk \).

for \(J=({x})\). More generally, one can take as \(\Bbbk \) any ring and as R a Henselian algebra over \(\Bbbk \).

Proposition 3.16

Given a finitely generated R-module V and two maps  . Suppose \(L\in \mathrm{Hom}_R(V,W)\), while H satisfies

. Suppose \(L\in \mathrm{Hom}_R(V,W)\), while H satisfies  , here \(\{\xi _i\}\) are some generators of V, while \(h_i(\{y_j\})\) are of order \(\geqslant 2\). Suppose

, here \(\{\xi _i\}\) are some generators of V, while \(h_i(\{y_j\})\) are of order \(\geqslant 2\). Suppose  holds for an ideal \(J\subsetneq R\). Then the equation

holds for an ideal \(J\subsetneq R\). Then the equation  has a solution

has a solution  .

.

Note that here R is not necessarily over a field, e.g. R can be  or

or  . Being of order \(\geqslant 2\) means that \(h_i(J)\subseteq J^2h(R)\) for any ideal \(J\subseteq R\).

. Being of order \(\geqslant 2\) means that \(h_i(J)\subseteq J^2h(R)\) for any ideal \(J\subseteq R\).

Proof

Expand \(v=\sum _i v_i\xi _i\), \(y=\sum _i y_i\xi _i\), then the equation reads  . Thus it is enough to solve the finite system of equations

. Thus it is enough to solve the finite system of equations  . As

. As  holds in our situation we get the solution. \(\square \)

holds in our situation we get the solution. \(\square \)

Corollary 3.17

Suppose a local ring \((R,{\mathfrak {m}})\) satisfies \(\mathrm{IFT}_{{\mathfrak {m}}\!,{\mathbbm {1}}}\). Consider the equation  , where \(\mathrm{ord}\,H\geqslant 2\).

, where \(\mathrm{ord}\,H\geqslant 2\).

-

(i)

If

then for any

then for any  there exists a solution.

there exists a solution. -

(ii)

If

then for any

then for any  there exists a solution.

there exists a solution. -

(iii)

If

and

and  then for any

then for any  there exists a solution.

there exists a solution.

Example 3.18

Let \((R,{\mathfrak {m}})\) be a local Henselian ring over a field. Take \(J={\mathfrak {a}}_L\), then the corollary implies Tougeron’s and Fisher’s theorems. As mentioned in the introduction, if one takes J the maximal possible that satisfies  then one gets the strengthening of Tougeron’s and Fisher’s theorems.

then one gets the strengthening of Tougeron’s and Fisher’s theorems.

But the corollary is useful for more general rings, e.g. if in equation (2) the term \(p(x_1,x_2)\) has integral coefficients then we get a solution over  .

.

4 Examples, remarks and applications

4.1 Comparison to Fisher’s and Tougeron’s theorems

The condition  (cf. Corollary 3.17) is a weakening of the condition \(J\subseteq {\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{{y}}({x},0)}\).

(cf. Corollary 3.17) is a weakening of the condition \(J\subseteq {\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{{y}}({x},0)}\).

Example 3.1

Let  , where \(\Bbbk \) is some base ring, take

, where \(\Bbbk \) is some base ring, take  . (If \(\Bbbk \) is a field then \({\mathfrak {m}}\) is the maximal ideal.) Consider the equation

. (If \(\Bbbk \) is a field then \({\mathfrak {m}}\) is the maximal ideal.) Consider the equation  , compare this to (2). Here \(H({y},{x})\) represents the higher order terms, it is at least quadratic in \(y_1,y_2\), while \(p({x})\in R\). In this case,

, compare this to (2). Here \(H({y},{x})\) represents the higher order terms, it is at least quadratic in \(y_1,y_2\), while \(p({x})\in R\). In this case,  and \(I_{\max }(L)={\mathfrak {a}}_{L}=(x^k_1,x^k_2)\subset R\). Thus \(({\mathfrak {a}}_L)^2=(x^{2k}_1,x^{k}_1x^{k}_2,x^{2k}_2)\). Thus to apply Tougeron’s and Fisher’s theorems we have to assume that

and \(I_{\max }(L)={\mathfrak {a}}_{L}=(x^k_1,x^k_2)\subset R\). Thus \(({\mathfrak {a}}_L)^2=(x^{2k}_1,x^{k}_1x^{k}_2,x^{2k}_2)\). Thus to apply Tougeron’s and Fisher’s theorems we have to assume that  .

.

On the other hand, by a direct check, the ideal  satisfies

satisfies  . Therefore Corollary 3.17 implies: if \(p({x})\in {\mathfrak {m}}^{2k+1}\) then the equation has a solution. For \(\Bbbk \) an algebraically closed field we get a better criterion: if \(p({x})\in {\mathfrak {m}}^{2k}\) then the equation has a solution.

. Therefore Corollary 3.17 implies: if \(p({x})\in {\mathfrak {m}}^{2k+1}\) then the equation has a solution. For \(\Bbbk \) an algebraically closed field we get a better criterion: if \(p({x})\in {\mathfrak {m}}^{2k}\) then the equation has a solution.

Note that to write down an explicit solution is not a trivial task even in the particular case of (2).

Further, if \(\Bbbk \) is not a field then we get the solvability of a “Diophantine type” equation. For example, for \(\Bbbk ={\mathbb {Z}}\) and \(H(y,{x}),p({x})\) defined over \({\mathbb {Z}}\), we get the criterion of solvability over  . Note that even for the equation \(y^n+yx^k+x^N=0\) the solvability over

. Note that even for the equation \(y^n+yx^k+x^N=0\) the solvability over  is not totally obvious.

is not totally obvious.

Therefore, even in the case of just one equation, the condition  strengthens the versions of Tougeron and Fisher.

strengthens the versions of Tougeron and Fisher.

4.2 Comparison of the condition  to \(H(V_1)\subseteq J L(V_1)\)

to \(H(V_1)\subseteq J L(V_1)\)

(cf. Corollary 3.7) It is simpler to check the ideals  than to look for a submodule satisfying the needed property. But the “ideal-type” criterion is in general weaker than the criterion via \(V_1\).

than to look for a submodule satisfying the needed property. But the “ideal-type” criterion is in general weaker than the criterion via \(V_1\).

Example 4.2

Consider the system

over  . In this case the annihilator of cokernel ideal is principal, \({\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{{y}}({x},0)}=(x_1x_2)\), thus

. In this case the annihilator of cokernel ideal is principal, \({\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{{y}}({x},0)}=(x_1x_2)\), thus  implies \(J={\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{{y}}({x},0)}\), see Sect. 3.2.1. And \((x_1x_2)\) does not contain \(x^n_1,x^m_2\) regardless of how big n and m are.

implies \(J={\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{{y}}({x},0)}\), see Sect. 3.2.1. And \((x_1x_2)\) does not contain \(x^n_1,x^m_2\) regardless of how big n and m are.

Of course, the general criterion of Corollary 3.7 suffices here. (One starts from \(V_1=\left( {\begin{matrix}x_1 R\\ x_2 R\end{matrix}}\right) \) and \(J=(x_1,x_2)\).)

This is a good place to see in a nutshell why no weakening of  in the form of some condition on ideals is possible.

in the form of some condition on ideals is possible.

Example 4.3

Consider the related system with a modified quadratic part

While the previous system has obvious solutions for \(n,m\geqslant 2\), this system has no solutions in R. Indeed, from the second equation it follows that \(y_1\) is divisible by \(x_2\). Then the left hand side of the first equation must be divisible as well, contradicting the non-divisibility of the right hand side.

Example 4.4

As a further illustration we consider the system

where  , here R is a regular local Henselian ring. Suppose

, here R is a regular local Henselian ring. Suppose  , i.e. \((a_1)\cap (a_2)=(a_1a_2)\). Then \({\mathfrak {a}}_L=(a_1a_2)\) is a principal ideal and thus

, i.e. \((a_1)\cap (a_2)=(a_1a_2)\). Then \({\mathfrak {a}}_L=(a_1a_2)\) is a principal ideal and thus  implies \(J={\mathfrak {a}}_L\). Hence the approach via

implies \(J={\mathfrak {a}}_L\). Hence the approach via  gives: if

gives: if

then the system has a solution.

We check the approach via filtration. To invoke Corollary 3.7 we need \(V_1\subset R^{\oplus 2}\) to satisfy the following condition: if  then

then

for any  (here T stands for transposition). This gives: \(V_1\subset (a_1a_2)R^{\oplus 2}\) and further substitution gives

(here T stands for transposition). This gives: \(V_1\subset (a_1a_2)R^{\oplus 2}\) and further substitution gives  . Put

. Put  , this ensures

, this ensures  . Note that L has the obvious continuous right inverse,

. Note that L has the obvious continuous right inverse,

Thus for \(b_1\in (a^2_1a_2)\), \(b_2\in (a_1a^2_2)\) the equation has a good order-by-order solution. The later condition is slightly weaker than (5).

Remark 4.5

Suppose the system of equations splits. Then it is natural to choose the split submodule:  . (Note that the converse does not hold: decomposability of \(V_1\) does not imply that the system splits in any sense. For example, all modules of the type

. (Note that the converse does not hold: decomposability of \(V_1\) does not imply that the system splits in any sense. For example, all modules of the type  are decomposable if V is free of rank \(>1\).) The following questions are important:

are decomposable if V is free of rank \(>1\).) The following questions are important:

-

Suppose L is block-diagonal. What are the conditions on H so that we can choose

?

? -

Formulate some similar statements for L upper-block-triangular v.s. \(V_1\) an appropriate extension of modules.

4.3 Equations whose solutions are not good

Often the “simple” and “most natural” solutions are not good (not even quasi-good) in our sense, moreover the (quasi-)good solutions do not exist at all.

Example 4.6

Consider the equation \(y^2=p(x)\) over  . Here \(L=0\), while \(H(y)\ne 0\). Corollary 3.7 claims that there are no good solutions. Explicitly, there does not exist a submodule \(\{0\}\ne V_1\subset R\) such that for any \(p(x)\in V_1\) there exists a solution

. Here \(L=0\), while \(H(y)\ne 0\). Corollary 3.7 claims that there are no good solutions. Explicitly, there does not exist a submodule \(\{0\}\ne V_1\subset R\) such that for any \(p(x)\in V_1\) there exists a solution  good in the sense of Sect. 2.2. This can be seen directly, if \(V_1\ne \{0\}\) then

good in the sense of Sect. 2.2. This can be seen directly, if \(V_1\ne \{0\}\) then  for \(N\gg 1\), and \(y^2=x^{2N+1}\) has no solutions in R.

for \(N\gg 1\), and \(y^2=x^{2N+1}\) has no solutions in R.

Of course, by a direct check, for any p(x) of even order there are solutions. But these solutions are not good.

Example 4.7

Consider the equation  over

over  , \({x}=(x_1,\ldots ,x_n)\), \(n>1\). Assume that \(g_1({x}), g_2({x})\) are generic enough, in particular

, \({x}=(x_1,\ldots ,x_n)\), \(n>1\). Assume that \(g_1({x}), g_2({x})\) are generic enough, in particular  . Then the equation cannot be presented in the form

. Then the equation cannot be presented in the form  , so it has no quasi-good solutions. (Even its linear part is non-solvable, though the equation has two obvious solutions.) This happens because an arbitrarily small deformation of the free term,

, so it has no quasi-good solutions. (Even its linear part is non-solvable, though the equation has two obvious solutions.) This happens because an arbitrarily small deformation of the free term,  , will bring an equation with no solutions in

, will bring an equation with no solutions in  . (In the case \(g_1({x}),g_2({x})\in C^\infty ({\mathbb {R}}^p,0)\) even a deformation by a flat function will lead to an equation with no solutions.)

. (In the case \(g_1({x}),g_2({x})\in C^\infty ({\mathbb {R}}^p,0)\) even a deformation by a flat function will lead to an equation with no solutions.)

4.4 An application: bifurcations of polynomial roots

Fix a polynomial \(p(y)=\sum ^d_{i=0}a_i y^i\). Suppose for a fixed tuple of the coefficients \((a_0,\ldots ,a_d)\) the polynomial has only simple roots (of multiplicity one). Then under small deformations of coefficients the roots deform smoothly. The multiple roots cause bifurcations in general. Our results provide a sufficient condition that a particular root deforms (smoothly/analytically/etc.) under the change of parameters. More precisely, starting from the initial ring R consider an extension S of R by one local variable, e.g.  or

or  , etc. Present the family of equations in the form

, etc. Present the family of equations in the form  . We say that a root \(y_0\) of the initial equation deforms (smoothly/analytically/etc.) if there exists a root \(y(t)\in S\) such that \(y(0)=y_0\).

. We say that a root \(y_0\) of the initial equation deforms (smoothly/analytically/etc.) if there exists a root \(y(t)\in S\) such that \(y(0)=y_0\).

To formulate the criterion we shift the variables \(y\mapsto y+y_0\), so that the (new) root of the initial equation is \(y=0\).

Corollary 4.8

-

(i)

(Tougeron) If \(a_0(t)\in (ta_1^2(t))\) then the root \(y=0\) of the initial equation deforms with t.

-

(ii)

(Belitskii–Kerner) If \(a_0(t)\in (t a_1(t))\) and

for any \(i\geqslant 2\) then the root \(y=0\) of the initial equation deforms with t.

for any \(i\geqslant 2\) then the root \(y=0\) of the initial equation deforms with t.

(Note that if \(a_0(t)\in (ta_1^2(t))\) then all assumptions of part two are satisfied.) To check this statement it is enough to put \(v=a_0/a_1\) and  .

.

Example 4.9

If all eigenvalues of a matrix are distinct, then they deform differentiably under small deformations of entries. In the case of multiple eigenvalues Corollary 4.8 ensures that at least one of potentially bifurcating eigenvalues deforms differentiably. More explicitly, expand the determinant

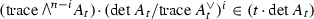

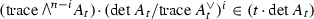

(Here  is the associated skew-power of \(A_t\).) Suppose the multiple eigenvalue is zero, so \(\det A_{t=0}=0\). Then

is the associated skew-power of \(A_t\).) Suppose the multiple eigenvalue is zero, so \(\det A_{t=0}=0\). Then

-

(Tougeron’s part) If \(\det A_t \in (t(\mathrm{trace}\,A^\vee _t)^2)\) then the eigenvalue deforms smoothly.

-

(Belitskii–Kerners’s part) If

then the eigenvalue deforms smoothly.

then the eigenvalue deforms smoothly.

4.5 A possible application: smooth curve-germs on singular spaces

Let \((X,0)\subset (\Bbbk ^n\!,0)\) be a germ (algebraic/analytic/formal) of a singular space. The smooth curve-germs lying on (X, 0) are an important subject, often used in the theory of arc spaces [8]. The first question is whether (X, 0) admits at least one smooth curve-germ, [13–15].

From the IFT point of view this question reads (for simplicity we work over  ): Can a given system of equations be augmented by another system so that the total system

): Can a given system of equations be augmented by another system so that the total system

has a one-dimensional power series solutions? For example

has a one-dimensional power series solutions? For example  , \(F(x_1,x_2(x_1),\ldots ,x_n(x_1))\equiv 0\)

? The strong IFT seems to lead to some results on the existence/properties of families of such curves.

, \(F(x_1,x_2(x_1),\ldots ,x_n(x_1))\equiv 0\)

? The strong IFT seems to lead to some results on the existence/properties of families of such curves.

5 An approximation theorem of Artin–Tougeron type

There are several approximation theorems guaranteeing analytic/\(C^\infty \)-solutions, provided a formal solution exists. Given the germ of an analytic map at the origin  , consider the implicit function equation

, consider the implicit function equation

here \({x}\) is the multi-variable, while \({y}\) is an unknown map,  .

.

A formal solution of this equation is a formal series  such that \(\widehat{F}({x},\widehat{y}({x}))\equiv 0\), where \(\widehat{F}\) is the (formal) Taylor expansion at zero of the map F. In general this solution does not converge off the origin. Two classical results relate it to the “ordinary” solution.

such that \(\widehat{F}({x},\widehat{y}({x}))\equiv 0\), where \(\widehat{F}\) is the (formal) Taylor expansion at zero of the map F. In general this solution does not converge off the origin. Two classical results relate it to the “ordinary” solution.

Theorem 5.1

Let \(\widehat{y}({x})\) be a formal solution of the analytic equation \(F({x},{y})=0\).

-

(i)

For every \(r\in {\mathbb {N}}\) there exists an analytic solution whose r’th jet coincides with the r’th jet of \(\widehat{y}({x})\) [1].

-

(ii)

There exists a \(C^\infty \)-solution \({y}({x})\) whose Taylor series at the origin is precisely \(\widehat{y}({x})\) and such that for any \(r\in {\mathbb {N}}\) there exists an analytic solution which is r-homotopic to \({y}({x})\) [31].

(Recall that two solutions \({y}_0({x}), {y}_1({x})\) are r-homotopic if there exists a \(C^\infty \)-family of solutions \({y}({x},t)\) such that \({y}_0({x})={y}({x},0)\), \({y}_1({x})={y}({x},1)\) and \({y}({x},t)-{y}_0({x})\) is r-flat at the origin.)

What if the equation \(F({x},{y})=0\) is not analytic but only of \(C^\infty \)-type? Does the existence of a formal solution for the completion \(\widehat{F}({x},{y})=0\) imply the existence of a \(C^\infty \)-solution? The naive generalization of Artin/Tougeron’s theorems does not hold.

Example 5.2

Let \(\tau \) be a function flat at the origin, e.g.

Consider the equation \( {\tau }^2(x)y(x) = {\tau }(x) \). The completion of this equation is the identity \(0\equiv 0\) thus every formal series  is a formal solution of \(\widehat{F}({x},{y})=0\). However, the equation has no local smooth solutions (not even continuous ones).

is a formal solution of \(\widehat{F}({x},{y})=0\). However, the equation has no local smooth solutions (not even continuous ones).

In this example the coefficient of y(x), i.e. the function \(\tau ^2\), is flat at zero. In other words, the ideal \({\mathfrak {a}}_{F'_{y}({x},{y}_0)}\) is too small and  .

.

The following statement supplements our previous results and extends Tougeron’s theorem to \(C^\infty \)-equations. Let \(R=C^\infty ({\mathbb {R}}^m\!,0)\) with the maximal ideal \({\mathfrak {m}}\subset R\). Suppose the equation \(F({x},{y})=0\) has a formal solution \(\widehat{{y}}_0\). By Borel’s lemma [25] we can choose a \(C^\infty \)-map \({y}_0\) whose completion is \(\widehat{{y}}_0\), thus \(F({x},{y}_0)\) is a vector of flat functions.

Theorem 5.3

Suppose the equation \(F({x},{y})=0\) has a formal solution and there holds  . Then there exists a \(C^\infty \)-map,

. Then there exists a \(C^\infty \)-map,  whose Taylor series at the origin is precisely \(\widehat{y}_0\) and such that \(F({x},{y}({x}))\equiv 0\).

whose Taylor series at the origin is precisely \(\widehat{y}_0\) and such that \(F({x},{y}({x}))\equiv 0\).

Proof

We seek the solution in the form \({y}={y}_0 +{z}\), where the map \({z}\) is flat. Expand  into the Taylor series with remainder

into the Taylor series with remainder

Then the equation takes the form

where the map \(F({x},{y}_0)\) is flat. Note that the summand G satisfies the condition \(G({x},\lambda {z}) = \lambda ^2hH({x},{z},\lambda )\) with a \(C^\infty \)-map H such that \( H_z'({x},0,\lambda ) = 0\). We look for the solution of (7) in the form

where  and \(A^\vee \) denotes the adjugate matrix.

and \(A^\vee \) denotes the adjugate matrix.

Then we arrive at the equation  with the \(C^\infty \)-map \(\widetilde{G}\) satisfying \(\widetilde{G}_u'({x},0) = 0 \). Dividing by \( d^2({x}) \), we obtain the equation

with the \(C^\infty \)-map \(\widetilde{G}\) satisfying \(\widetilde{G}_u'({x},0) = 0 \). Dividing by \( d^2({x}) \), we obtain the equation

where the map \(\tau \) is flat. By the classical Implicit Function Theorem, the latter equation has a local flat \( C^\infty \)-solution. Hence, the map z satisfies (7) and \({y}={y}_0+{z}\) is the solution we need. \(\square \)

Remark 5.4

-

(a)

The assumption of the theorem can be stated as: Every function flat at the origin is divisible by

. In particular this implies that

. In particular this implies that  is non-degenerate in some punctured neighborhood of the origin \(0\in ({\mathbb {R}}^m\!,0)\). Note that \({y}_0\) is defined up to a flat function, but the assumption does not depend on this choice.

is non-degenerate in some punctured neighborhood of the origin \(0\in ({\mathbb {R}}^m\!,0)\). Note that \({y}_0\) is defined up to a flat function, but the assumption does not depend on this choice. -

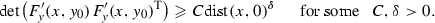

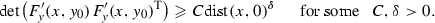

(b)

Recall that a function \(g({x})\) is said to satisfy the Lojasiewicz condition (at the origin) if there exist constants \(C>0\) and \(\delta >0\) such that for any point \({x}\in ({\mathbb {R}}^m\!,0)\):

. As is proved, e.g. in [30, Section V.4], \(g({x})\) satisfies the Lojasiewicz condition at the origin iff

. As is proved, e.g. in [30, Section V.4], \(g({x})\) satisfies the Lojasiewicz condition at the origin iff  . Thus the assumption of the theorem can be stated in the form

. Thus the assumption of the theorem can be stated in the form

-

(c)

A similar statement can be proved for \(C^k({\mathbb {R}}^p\!,0)\)-functions, but then the solution is in general only in the \(C^{k-2-\delta }\)-class.

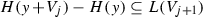

6 Openness of group orbits and applications to the finite determinacy

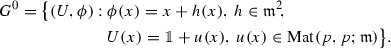

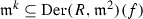

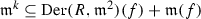

Given a module W over some base ring \(\Bbbk \) (we assume \(\Bbbk \supseteq {\mathbb {Q}}\)) with a decreasing filtration \(\{W_i\}\). Consider the group of all \(\Bbbk \)-linear invertible maps that preserve the filtration  . Fix some subgroup

. Fix some subgroup  and let \(G^0\subseteq G\) be the unipotent subgroup, Sect. 6.1.1. Fix some element \(w\in W\), consider the germ of its \(G^0\)-orbit \((G^0w,w)\) and the tangent space to this germ \(T_{(G^0w,w)}\), Sect. 6.1.2. (Note that the existence of \(T_{(G^0w,w)}\) places some restrictions on G, see (8).)

and let \(G^0\subseteq G\) be the unipotent subgroup, Sect. 6.1.1. Fix some element \(w\in W\), consider the germ of its \(G^0\)-orbit \((G^0w,w)\) and the tangent space to this germ \(T_{(G^0w,w)}\), Sect. 6.1.2. (Note that the existence of \(T_{(G^0w,w)}\) places some restrictions on G, see (8).)

Theorem 6.1

If \(W_k\subseteq \overline{T_{(G^0w,w)}}\) then \(w+W_k\subseteq \overline{G^0w}\).

Here  denotes the closure with respect to the filtration \(W_\bullet \). Thus the statement is of the order-by-order-type. In particular, in the proof we can assume that W is \(W_\bullet \)-complete. The proof is given in Sect. 6.2, after some preparations in Sect. 6.1. Some immediate applications to the finite determinacy are given in Sect. 6.3.

denotes the closure with respect to the filtration \(W_\bullet \). Thus the statement is of the order-by-order-type. In particular, in the proof we can assume that W is \(W_\bullet \)-complete. The proof is given in Sect. 6.2, after some preparations in Sect. 6.1. Some immediate applications to the finite determinacy are given in Sect. 6.3.

6.1 Preparations

6.1.1 The unipotent subgroup \(G^0\)

Consider the system of projecting maps  . They induce projections on the group

. They induce projections on the group  and accordingly the restrictions

and accordingly the restrictions  . (We use the same letter \(\pi _j\), this causes no confusion.) We define the “unipotent” part of the group

. (We use the same letter \(\pi _j\), this causes no confusion.) We define the “unipotent” part of the group

Example 6.2

Let \((R,{\mathfrak {m}})\) be a local ring as in Example 3.6.

-

(a)

Let \(G=\mathcal {R}\) be the group of local coordinate changes \({x}\mapsto \phi ({x})\). They act on the elements of the ring by \(f({x})\mapsto \phi ^*(f({x}))=f(\phi ({x}))\). For the filtration \(\{{\mathfrak {m}}^{j}\}\) the group \(G^0\) consists of the changes of the form \({x}\mapsto {x}+h({x})\), where \(h({x})\in {\mathfrak {m}}^{2}\).

-

(b)

More generally, consider the group of automorphisms of a module

acting by

acting by  , where \(\phi \in \mathcal {R}\), while \(U({x})\) is an invertible matrix over R. Then

, where \(\phi \in \mathcal {R}\), while \(U({x})\) is an invertible matrix over R. Then

-

(c)

Note that \(G^0\) depends essentially on the filtration. In the previous examples we could take the filtration by the powers of some other ideal \(\{J^i\}\) or just by a decreasing sequence of ideals.

6.1.2 Logarithm, exponent and the tangent space

As is mentioned after Theorem 6.1 we can pass to the completion of the module \({\widehat{W}}\) with respect to the  filtration. Accordingly we have

filtration. Accordingly we have  , the completions of

, the completions of  .

.

Among all \(\Bbbk \)-linear maps (not necessarily invertible) \(\mathrm{End}_\Bbbk ({\widehat{W}})\) consider the nilpotent ones  . Consider the logarithmic map (recall that \(\mathbb {Q}\subset \mathbbm {k}\))

. Consider the logarithmic map (recall that \(\mathbb {Q}\subset \mathbbm {k}\))

As \(g\in {\widehat{G}}{}^0\),  , thus the sum (though infinite) is a well-defined linear operator on \({\widehat{W}}\). As this logarithm is defined by the standard formula, we have \(\ln a^ia^j=\ln a^i+\ln a^j\). But in general \(\ln ab\ne \ln a+\ln b\), as a, b do not commute. Nevertheless we assume that

, thus the sum (though infinite) is a well-defined linear operator on \({\widehat{W}}\). As this logarithm is defined by the standard formula, we have \(\ln a^ia^j=\ln a^i+\ln a^j\). But in general \(\ln ab\ne \ln a+\ln b\), as a, b do not commute. Nevertheless we assume that

This is satisfied in many cases, e.g. in all our examples.

Definition 6.3

The tangent space to \({\widehat{G}}{}^0\) at the unit element is the \(\Bbbk \)-module \(T_{\scriptscriptstyle {\widehat{G}}{}^0}=\ln {\widehat{G}}{}^0\subseteq \mathrm{End}_\Bbbk ({\widehat{W}})\).

Consider the exponential map,  defined by

defined by

As \(\xi \) is a nilpotent endomorphism, the sum (though infinite) is a well-defined linear operator and is invertible.

Lemma 6.4

The image \(\exp T_{\scriptscriptstyle {\widehat{G}}{}^0}={\widehat{G}}{}^0\) and the maps \(T_{\scriptscriptstyle {\widehat{G}}{}^0}\underset{\scriptscriptstyle \ln }{\mathop {\rightleftarrows }\limits ^{\scriptscriptstyle \exp }}{\widehat{G}}{}^0\) are mutual inverses.

Proof

Let \(\xi \in T_{\scriptscriptstyle {\widehat{G}}{}^0}\), then \(\xi =\ln g\) for some \(g\in {\widehat{G}}{}^0\). Thus \(\exp \xi =\exp \ln g=g\in {\widehat{G}}{}^0\). The maps \(\ln \) and \(\exp \) are mutual inverses as they are defined by the same Taylor series as the classical functions. \(\square \)

6.1.3 The relevant properties of the exponent and variation operator

The j’th stabilizer of \(w\in W\) is the subgroup  . For any \(g\in G^0\) and \(w\in W\) define the variation operator \(\Delta _w(g)=gw-w\).

. For any \(g\in G^0\) and \(w\in W\) define the variation operator \(\Delta _w(g)=gw-w\).

Lemma 6.5

The restriction  , \(j\geqslant 1\), is a homomorphism of groups.

, \(j\geqslant 1\), is a homomorphism of groups.

Proof

First note that the image of \(\Delta _w{|}_{\mathrm{St}_j(w)}\) is indeed in  as \(\pi _j(\Delta _w(g))=0\) for any \(g\in \mathrm{St}_j(w)\). Let \(g\in G^0\) and \(h\in \mathrm{St}_j(w)\). Then

as \(\pi _j(\Delta _w(g))=0\) for any \(g\in \mathrm{St}_j(w)\). Let \(g\in G^0\) and \(h\in \mathrm{St}_j(w)\). Then

as \(\pi _j(hw)=\pi _j(w)\). \(\square \)

Lemma 6.6

Let \(\xi \in T_{\scriptscriptstyle {\widehat{G}}{}^0}\) and \(w\in W\).

-

(i)

\(\pi _j(\exp \xi )\in \pi _j(\mathrm{St}_j(w))\) iff \(\pi _j(\xi w)=0\in \pi _j(W)\).

-

(ii)

If \(\pi _j (\exp \xi )\in \pi _{j}( \mathrm{St}_{j}(w))\) then \(\pi _{j+1}(\Delta _w(\exp \xi ))=\pi _{j+1}(\xi w)\).

Proof

(i) (\(\Rightarrow \)) As the stabilizer is a group, \(\pi _j(\exp t\xi w)=\pi _j (w)\) for all \(t\in {\mathbb {Z}}\). The left hand side of this equation is a polynomial in t because \(\xi \) is nilpotent. As \(\mathrm{char}\,\Bbbk =0\) and \(\Bbbk \supseteq {\mathbb {Q}}\), the equality holds for all \(t\in \Bbbk \). But this implies \(\pi _j (\xi w)=0\).

(\(\Leftarrow \)) If \(\pi _j(\xi w)=0\) then \(\pi _j(\xi ^k w)=0\), thus \(\pi _j (\exp \xi )\in \pi _j (\mathrm{St}_j(w))\).

(ii) The function \(h(t)=\pi _{j}(\Delta _w(\exp t\xi ))\) is a polynomial in t. By Lemma 6.5, it is additive. Thus \(h(t)=tc\) where \(c=h(1)=\pi _j (\exp \xi w-w)=\pi _{j}(\xi w)\). \(\square \)

6.2 Proof of Theorem 6.1