Abstract

Leveraging the richness of population register data in Denmark, this study provides an in-depth examination of the residential situations of the formerly incarcerated over the first 3 years after prison. These data allow us to examine precisely who former prisoners reside with after release, and whether the characteristics of housemates, such as prior conviction status, and relationship type, such as familial ties, are associated with criminal reconviction. While Denmark has one of the lowest incarceration rates in the world, like many other Western countries, it is challenged by high recidivism rates among the formerly incarcerated. Using data on the population of all individuals released from prison between 1991 and 2014 and estimation via Cox proportional hazards models, we find that formerly incarcerated individuals who move into a residence with other individuals with criminal records have significantly greater hazards of reconviction, even after controlling for an extensive set of observed confounders. Residing with family members, particularly spouses, significantly reduces the likelihood of recidivism, but only if the family members do not have a recent criminal conviction. Results underscore the importance of housing arrangements and family ties during the post-release period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Individuals who are recently released from prison face numerous challenges that they must overcome to avoid persisting in crime, including finding employment, paying mountainous fines and fees, and accessing drug and mental health treatment (see, e.g., Harding et al., 2019; Leverentz, 2022; Miller, 2021; Western, 2018). One particularly important and fundamental challenge relates to where and with whom to live. Recent studies in the USA have shown that in the first few days post-release, the vast majority of formerly incarcerated individuals face severely constrained residential options and tend to reside with family or friends, with temporary shelters another common location (La Vigne et al., 2004; Leverentz, 2022; Warner & Remster, 2021; Western et al., 2015). In Michigan, Herbert et al. (2015) found that, over the course of parole, parolees reside with at least one parent in 22% of “residential episodes”—that is, a continuous period of time living in the same location and living arrangement. Seventeen percent of residential episodes are with other family members, 18% are with romantic partners, 6% are with friends, 3% involve residing alone, and the remainder represent homeless episodes or other housing situations not fitting into the aforementioned categories. Hence, the formerly incarcerated may reside in a variety of living situations during the first few years after release from prison, and an individual’s residential situation and the type of housemate he/she has may be fundamental to desisting from crime and successful reintegration back into society.

Whereas several recent studies (e.g., Harding et al., 2013; Herbert et al., 2015; Warner & Remster, 2021) have offered meticulous analyses of living arrangements of the formerly incarcerated and individuals with criminal histories, it is still unknown to what extent the friends, family members, and romantic partners that often share residence with the formerly incarcerated themselves have criminal records, and to what consequence. For instance, Jacobs and Gottlieb (2020) and Steiner et al. (2015) each observe that residing with family members relative to other living situations, such as residing with a non-family housemate, reduces the likelihood of criminal recidivism. However, these studies are unable to distinguish whether the familial housemates, too, had criminal records. Indeed, typical data limitations make it very challenging to document who the formerly incarcerated reside with and the background characteristics of their housemates. Hence, it is an open question whether family ties are universally beneficial or whether it depends on the criminal backgrounds of family members.

An initial motivation of our study is to ask a basic but fundamental question: to what extent do the formerly incarcerated reside with individuals with criminal records during their first few years after their release? Furthermore, we ask: to what extent does residing with someone with a criminal record raise a person’s likelihood of recidivism, if at all (relative to residing alone or residing with someone without a criminal record)? Last, but importantly, does the purported benefit of residing with family members after incarceration, with respect to criminal desistance, depend upon whether the family members themselves have a criminal record? Put differently, does the beneficial effect of living with family only hold if those family members are free of crime?

To answer these questions, we capitalize on the richness of Danish population register data, which contain information on all individuals released from prison in Denmark in the period between 1991 and 2014 (N = 232,544) as well as their locations of residence before and after prison, indicators of who they resided with at each location, and whether these housemates had criminal records. We are able to determine co-residence because Danish housing registers (i.e., administrative databases covering the entire country population) provide information on where all individuals reside (or if they have no fixed dwelling), along with an indication of when a resident moves and where he/she subsequently resides. We can determine if co-residents were family members versus other individuals by linking housing registers to birth certificates and marriage certificates (available in the population register).

In Denmark, imprisonment is generally reserved for the most serious offenders. Although imprisonment is used to a lesser degree in Denmark compared to the USA and some other Western countries (e.g., the UK), recidivism rates are comparable, and the country faces similar challenges related to persistent offending found elsewhere (Durose & Antenangeli, 2021; Statistics Denmark, 2021; UK Ministry of Justice, 2021). Hence, while our empirical focus is on Denmark, we would suggest that our findings related to housemate and family influences and recidivism are relevant to other Western countries.

Criminal Recidivism and Living Arrangements

Criminal history, marriage, employment, addiction, mental health disorders, stigma, rationality and agency, identity, and neighborhood context are among the most widely discussed and acknowledged correlates of criminal persistence and desistance as well as related outcomes such as recidivism (Bersani & Doherty, 2018; Huebner & Berg, 2011; National Research Council, 2007; Rocque, 2017). Various classification schemes have been used by criminologists to group the correlates of recidivism by similarities, including the distinction between structural vs. subjective predictors and the distinction between internal and external factors (Bersani & Doherty, 2018; Rocque, 2017). Given extensive attention to identifying the correlates of recidivism in the research literature, in this section, we provide a focused discussion on the reasons why particular types of living arrangements and housemates may facilitate, or curtail, recidivism. Indeed, rather than taking a “causes-of-effect” approach to identify and validate the multitude of predictors of recidivism (see Sampson et al., 2013), this study takes an “effects-of-a-cause” approach to examine the specific influence of housemates on criminal persistence and desistance.

Why Might the Criminal Histories of Housemates Matter?

There are a variety of mechanisms by which a convicted housemate may influence the behavior of a given individual (for a recent review of peer influence explanations for crime, see McGloin & Thomas, 2019). For instance, Akers (1973) emphasized the role of operant conditioning in explaining the influence of criminal peers, arguing that a core part of the learning process of criminal behavior is “differential reinforcement”—i.e., that individuals learn the actual or anticipated rewards and consequences of their behavior. In theory, then, if a housemate expresses support for criminal behavior in some manner, for example, by praising the act, expressing gratitude for monetary benefits, or by serving as an accomplice, then this positive reinforcement makes criminal behavior more likely. Consistent with this hypothesis, research has found that the beneficial effect of marriage on desistance from crime is only found in relationships in which the spouse does not have a criminal record (Andersen et al., 2015). Conversely, relationships can have a controlling influence (Hirschi, 1969; Sampson & Laub, 1993). If a housemate sanctions or threatens to sanction the behavior in some way, for instance, by ending the relationship or kicking the individual out of the house, then this negative reinforcement may render criminal behavior less likely.

Negative reinforcement may occur even in the absence of threats from a prosocial peer or housemate, in the form of imbalance in relationships. Applying Heider’s (1958) balance theory to the study of delinquency, McGloin (2009) argued that an imbalance in the criminal propensities between two individuals creates a tension because people naturally prefer social equilibrium. To achieve balance in a relationship when one individual has a heightened criminal propensity and the other does not, the individual with criminal tendencies may gravitate towards more prosocial behavior, whereas the other individual becomes more delinquent.

Important for the present study, the influence of one’s social ties may depend on frequency, duration, priority, and intensity of social interactions (Newcomb, 1953; Sutherland, 1947). For instance, priority as a source of variation suggests that family and associations from earlier in life may be more influential than other relationships. Intensity suggests that family members and closer associates are more influential (McGloin & Thomas, 2019; Sutherland, 1947). Similarly, and with respect to our discussion of balance theory, imbalance in relationships about crime will produce a greater strain on individuals (i.e., a greater need to resolve the imbalance) as the strength or intensity of the relationship increases (McGloin, 2009; Newcomb, 1953). Hence, housemates, particularly because of frequency and intensity, may be quite important conduits of criminal influence. This assertion parallels research by Anker and Andersen (2021) on the intergenerational transmission of crime between parents and children, in that the active transmission of criminal influences is facilitated by direct and frequent interaction between family members, particularly through co-residence.

Whereas learning, reinforcement, and balance represent key mechanisms by which peers and other social ties may be influential, family, friends, and associates may influence an individual’s criminal (and prosocial) conduct through additional mechanisms. For instance, housemates may facilitate criminal behavior through the creation of criminal opportunities or by putting an individual in situations conducive to crime (Laub & Sampson, 2003; Osgood et al., 1996; Warr, 2002). And exposure to criminal peers and criminally involved family members may lead to an individual’s recidivism by way of a “courtesy stigma” that draws in the attention and surveillance of the police, probation, and parole (Goffman, 1963). For instance, if a brother in the same house is criminally active, police may assume that crime runs in the family.

Heterogeneity by Relationship Type

As alluded to in the preceding section, a potential moderating influence with respect to the criminal history of housemates and reoffending may be the nature of the relationship between the housemates. Numerous studies have shown that reuniting the formerly incarcerated with their families can provide essential support to them as they work to desist from crime (e.g., Harding et al., 2019; La Vigne et al., 2004; Steiner et al., 2015; Visher et al., 2004), and an extensive literature in life-course criminology documents the important role of a stable marriage in the desistance process (Bersani & Doherty, 2013, 2018; Sampson & Laub, 1993). A healthy marriage may undermine short-term inducements to crime such as hanging out with criminal peers. Marriage may also lead to longer-term conforming behavior because of the controlling influence of a spouse, for example, by influencing a commitment to structured daily activities (Laub & Sampson, 2003). Empirical research on within-individual change in criminal behavior due to local life circumstances does indeed find that serious male offenders who moved in with a spouse had double the odds of terminating their offending compared to individuals who moved out of a residence with a spouse (Horney et al., 1995; see also Piquero et al., 2002).

Nevertheless, it is also true that the formerly incarcerated often have family members with their own criminal problems as well as histories of substance abuse (Fontaine & Biess, 2012). Hence, residing with a family member with a criminal history can increase an individual’s risk of recidivism, through exposure to criminal opportunities and substance use and through stresses and conflicts associated with relationships (Fontaine & Biess, 2012; Harding et al., 2019; Leverentz, 2014). Therefore, there may be heterogeneity in the influence of family ties on the persistence and desistance of crime among formerly incarcerated individuals, depending on whether familial housemates are actively or recently involved in criminal activity.

Positive Peer Support and the Importance of Neighborhoods

Two other factors may be important for understanding the association between housing situations and criminal recidivism, leading to either an amplification of the influence of a housemate or, conversely, a reduction. We address the following possibilities in supplementary analyses in the “Supplementary Material.” First, residing with someone, including a family member, who has recovered and rehabilitated from a history of criminality and substance abuse may be therapeutic and supportive (Washington State Institute for Public Policy, 2019). In the context of our study, we therefore expect that an individual’s likelihood to reoffend because of convicted housemates would be relatively muted when those housemates are rehabilitated or are no longer actively involved in crime. Conversely, we expect that the likelihood to reoffend would be most pronounced when those housemates are active or very recent offenders.

Second, formerly incarcerated and convicted individuals tend to cluster in geographic space (Kirk, 2019) and a mounting base of research in both the USA and Denmark reveals that proximity to concentrations of criminal offenders elevates crime and reoffending rates (e.g., Chamberlain & Wallace, 2016; Damm & Dustmann, 2014; Kirk, 2015; Rotger & Galster, 2019). Based on this line of research, it could thus be the case that influences from the wider neighborhood will be more consequential than influences inside the household and that the influence of a housemate depends upon the availability of negative (or pro-social) ties in the surrounding neighborhood.

Summary of Hypotheses

Per the preceding discussion, we expect that formerly incarcerated individuals residing with a housemate with a criminal record will have an elevated probability of recidivism relative to individuals residing alone or with non-convicted housemates (H1). We also expect that the association between living with a convicted housemate and recidivism will be weaker if there are non-convicted residents in the dwelling as well—i.e., a mixture of convicted and non-convicted housemates rather than solely living with a convicted housemate(s) (H2). Turning to the importance of family, we expect that residing with non-convicted family members will decrease the likelihood of recidivism relative to residing with non-convicted individuals with no family relation or convicted individuals (H3). Moreover, per our statements about the importance of priority and intensity of social relations, we expect the influence of a non-convicted spouse to be the most valuable of the family relations (H4). We cannot a priori assess whether to expect the influence from convicted family members to be positive, negative, or null. We take this view, in part, because even if a family member is engaged in criminal conduct, the nature of the relationship with the focal individual may serve as a controlling influence, with the focal individual investing in stakes in conformity.

Institutional Context

To give readers some understanding of the Danish context, here, we briefly lay out details about imprisonment, the release process, and the provision of social housing.

Imprisonment and Release in Denmark

Denmark has one of the lowest incarceration rates in the world (Fair & Walmsley, 2021). The shortest prison sentences in Denmark are just 7 days long; more than half of sentences are shorter than 4 months (including prison sentences as well as home confinement); and as little as 10% of sentences exceed 2 years (Danish Prison and Probation Service, 2020).

Most incarcerated individuals in Denmark are placed in open prisons, which have fewer safety precautions than closed prisons (closed prisons are reserved for individuals serving sentences longer than 5 years, for the gang affiliated, for individuals considered dangerous to other prisoners, and for individuals with high risk of escape). In open prisons, the availability of resocialization initiatives is high, and open prisons offer robust training and education opportunities (and often different types of treatment, such as addiction treatment). Despite this rehabilitative environment, roughly half of individuals released from Danish prisons are convicted of a new crime within just one year of release (Statistics Denmark, 2021).

The prisoner release process formally begins at or shortly after admission to prison and focuses on the individual’s needs and resources, including housing needs. A release plan is mandatory for individuals serving sentences longer than 4 months, but in practice most incarcerated individuals in Denmark have one. By law, early release onto parole is expected after having served two-thirds of the sentence, if the sentence is longer than 2 months. Once released, prison staff are required to inform social services about the individual’s resources and challenges, to secure smoother assistance in the community. A small number of individuals, less than 0.5% in our data, spend time in a halfway house and thus mechanically have convicted housemates, wherefore we omit halfway house stays in our analyses.

Housing During Imprisonment and Release in Denmark

A crucial aspect of the aforementioned release process is securing stable housing, and in Denmark it is entirely possible to maintain pre-existing housing while imprisoned and to receive government support in doing so. Rights and obligations concerning housing during imprisonment in Denmark have been formally regulated by law since 1998 (Orders no. 387 of June 22, 1998 and 517 of July 3, 1998). The laws specify that individuals are eligible for housing benefits during confinement, which means that the municipality where they originated pays part of an individual’s rent while he/she is in prison. The rule only applies to those serving sentences shorter than 6 months. For longer sentences, in which individuals more commonly lose their former housing situation, a caseworker instead assists the individual in searching for housing, such as subletting or signing up for social housing.

Nevertheless, municipalities often have a financial disinterest in receiving newly released prisoners, and collaboration with the Danish Prison and Probation Service can often be hampered by this fact. As such, although features of the Danish context implies that housing situations for formerly incarcerated persons could well be better than in a totally unregulated context, we expect residential instability to be common rather than the exception for released individuals in Denmark.

Data and Methods

We rely on administrative data covering the full population of Danish residents from 1991 to 2017 to construct a survival panel data set with exact information on where and with whom all formerly incarcerated individuals lived every day since they were released from prison, and until 3 years following release or until they committed a new criminal offense that resulted in a conviction. There are four key features that make Danish administrative data particularly desirable for this study.

First, attrition is almost non-existent in the data because administrative registers are crucial to the functioning of the Danish welfare state (Andersen, 2018). This is particularly important for this area of study where attrition rates are usually high (Western et al., 2016). Second, we are able to track individuals who disappeared from the data for a period if they migrated out of the country, were not registered at any dwelling, or died. This feature of the data overcomes the issue of missing censoring common in survival analyses (Allison, 2014). Third, we are able to merge several sources of information from different registers to the same individual through a unique personal identifier. This feature is important because it allows us to reduce observed confounding by conditioning on a wide range of background characteristics, such as criminal history, prior living arrangements, education, employment, and other social and demographic variables. Finally, we observe these characteristics not only for the focal individual, but also for his or her housemates at any given point. This combination of features presents us a rare opportunity to examine the experiences of the formerly incarcerated following release from prison (for further discussion, see Lyngstad & Skardhamar, 2011).

Sample Selection

To construct our analytic sample, through the Imprisonment register we identified all individuals who served a prison sentence and were admitted to prison in 1991 or later and released by the end of 2014. Releases include individuals released via parole as well as those released following completion of their full sentence. We chose 2014 as an end date because we measure reconviction for up to 3 years following release and 2017 is the last fully updated data year in the Convictions register. The starting sample contained 253,339 prison spells for 123,466 individuals. We drop 281 (0.1%) spells for 102 individuals who died in prison, and 8564 (2.4%) spells for 2940 individuals who were below the age of 18 when admitted to prison. We exclude these young individuals because they are placed in separate institutions, rather than prisons, and are therefore irrelevant to the scope of this study (see, Langsted et al., 2011). We also drop 6554 (2.7%) spells for 3305 individuals with missing background information (see Table B3 for further details on missing variables). Finally, we exclude 5396 (2.3%) spells for 1419 individuals who were not registered with an address at all after their release from prison, very likely due to deportation (which we are unable to observe directly in the administrative registers available to us, but the number almost perfectly corresponds to the number of foreigners in Danish prisons who are usually expelled from the country following release; Danish Ministry of Justice, 2016). Our final sample contains 232,544 spells for 115,700 individuals. In the supplementary material, Table A1 summarizes this sample delimitation procedure, and Appendix B provides further details on all steps involved in constructing the data set.

Key Variables

Dependent Variable

Our dependent variable is the hazard of reconviction following release from prison—that is, the probability of reconviction on a given day conditional on the fact that the individual had not yet been reconvicted. We obtained conviction information from the Convictions register, which is recorded by the Danish National Police. Our dependent variable thus contains the entire universe of formal convictions in Denmark. We exclude non-criminal offenses, such as violations of the Traffic Act, from our measure. To avoid judicial processes from influencing our measure of the timing of convictions, we recorded convictions by the date the offense was committed rather than the date of conviction. This also has the advantage of more directly tying our outcome variable to the timing of the behavior that led to conviction, not to the court or prosecutor decision itself. We construct a binary measure indicating whether the individual committed a crime for which he/she was later convicted each day following release for a period of 3 years.

To test whether our main results are sensitive to our choice of dependent variable, Table A2 in the supplementary material replicates our main results using days until rearrest, days until a new charge, and the compound days until any contact with the criminal justice system (i.e., arrest, charge, or reconviction). Furthermore, in Table A3, we replicate our main analysis using months instead of days as our time unit of analysis. Both sets of sensitivity tests produced results very similar to our main results presented in the next section.

Living Arrangements

The administrative registers contain information on all residential tenancy spells in Denmark since 1980, including all occupants’ personal identifiers, and exact start and end of tenancy dates. These data allow us to construct detailed measures of whether the individual lived alone or with housemates every single day following release. Merging the Convictions register informs whether these housemates were convicted prior to the focal individual’s release from prison. Our two main independent variables are (1) a binary variable equal to 1 if the focal individual lived with at least one adult housemate (above the age of 15, which is the age of criminal responsibility in Denmark) on that day, and zero otherwise; and (2) a binary variable equal to 1 if at least one current adult housemate was convicted for a crime that occurred within the 2 years before the focal individual’s release from prison. We define criminal housemates in this way—i.e., a conviction for a crime committed within the past 2 years—to focus our analysis on the influence of active or recently active criminal ties. However, in a moderating analysis to follow, we also examine whether the influence of criminal housemates depends on the recency of the conviction and extend our focus to any housemate convicted up to 5 years prior to the focal individual’s release from prison. Additionally, we examine the interaction between our two independent variables, to determine if the association between reconviction and living with a convicted housemate weakens when the dwelling also includes a housemate without a criminal record.

We acknowledge that it would be preferable to have behavioral measures of actual offending for housemates (i.e., our independent variable) as well as the focal individual (i.e., dependent variable) rather than, or in addition to, conviction. We revisit this limitation in the “Discussion” section.

It is obviously pivotal to our setup that the Housing register provides accurate information on where people live, and not just where people were registered as living. Pedersen et al. (2020) and Ruge et al. (2020) evaluated the quality and accuracy of the housing location information in the Housing register as high, finding that as little as 0.34% of the Danish population are wrongfully registered on any given day because of registration delays (in Denmark, citizens are required to report a change in address no later than five days after they move, which explains the low rate of error). Another way these evaluations analyzed the rate of wrongful registrations was by observing how many citizens were recorded with an address but did not have any contact with social services (broadly defined, including healthcare, schools, tax authorities, the criminal justice system, and the like) for three consecutive years, which in Denmark would most likely signal that the person does not live at the registered address. Again, accuracy was found to be high, indicating that only between 0.5 and 1.9% of registrations are likely to be erroneous. The reason the accuracy of the data is high is because of the central role the Housing register plays for public governance in Denmark. From the citizen’s perspective, correct housing registration is a requirement for the payout of social benefits (such as social assistance), access to healthcare, and the like. From the state’s perspective, correct housing registration is essential as it serves as the information base for calculating municipal reimbursements of social expenditures and taxes from the central government.

Control Variables

In all analyses, we control for baseline living arrangements by including dummy variables indicating whether the released individual lived with at least: (a) one non-convicted adult housemate, (b) one child below the age of 15, and (c) one convicted housemate, all measured at the time of admission to prison. We include these controls because prior living arrangements and pre-incarceration social relations may influence subsequent living situations as well as the ease or difficulty of navigating the process of prisoner reentry and reintegration. We also include time-varying variables indicating whether the focal individual moved to a new residence, and whether he/she resided with at least one non-adult housemate on any given day. The former variable is an indicator of residential instability, as the period after release is often highly unstable and transient, and residential instability may be correlated with both habitation with individuals with criminal records and reconviction.

In addition, we condition on a wide range of individual characteristics, measured prior to prison admission, except for age, which we measure at the release date. Other sociodemographic characteristics include gender, the number of children the individual had, and whether at least one of the individual’s parents were immigrants to Denmark from a non-Western country. Following the official definitions from Statistics Denmark, we include dummy variables indicating whether the individual was married (married people and people in registered partnerships, such as same-sex marriages), in a cohabiting relationship (defined as either two persons who lived together and had at least one child or two co-resident persons of opposite sex with age difference less than 15 years), or single (the reference category which represented the inverse of married or cohabiting couples). We also control for years of education (obtained from official education credentials via the Ministry of Education), earnings (all legal labor earnings reported to the Danish Customs and Tax Administration), and labor market attachment (whether employed, unemployed, or outside the labor market on the last day of November the year prior to prison admission). Finally, we include information on the individual’s current case for which he/she was released from prison (type of criminal offense and sentence length) as well as criminal history variables (number of previous convictions and incarcerations). Table 1 summarizes the variables.

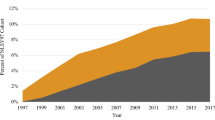

As shown in Table 1, around 44% of the individuals in our sample were reconvicted for a criminal offense that occurred within 3 years following their release from prison. This reconviction rate is lower than current official estimates produced by Statistics Denmark (2021) because we draw upon release cohorts back to 1991 (the reconviction rate in Denmark has steadily increased over time). Among those who were reconvicted, the average time from prison release to the offense of reconviction was 335 days and the median was 243 days. On average, we observed individuals in our dataset for 680 days. This number is substantially lower than 1095 days (3 years) because almost half of the individuals who recidivated are reconvicted in less than a year, and hence censored from that point.

Table 1 also suggests that there is some interval censoring in our survival panel. On average, we are unable to identify individuals’ addresses in 9% of the person-days between release from prison and the 3-year follow-up period (or offense date). This is primarily driven by individuals who lived on the street or individuals who lived with family or friends without registering their residence to the local authorities. As noted previously, time spent in halfway houses is rare in the Danish context—i.e., just 0.45% of the cases in our data spent time in a halfway house. Because housemates in halfway houses are, by definition, previously convicted, we excluded these relatively few observations from the data by setting the addresses to missing. Importantly, this censoring from missing addresses does not affect the measurement of our outcome variable because convictions are registered in a separate administrative register.

Analytic Strategy

We start our analyses by summarizing with whom the people in our data live. We then summarize the features that select the people in our data into living arrangements, which we do by regressing all covariates on living arrangement 3 months after release, and again 3 years after release, to observe whether the pattern changed over the follow-up period (see Tables A4 and A5 in the supplementary material). We then move on to the more elaborate analyses of the association between living with a convicted housemate and criminal reconviction. First, we measure whether living with a convicted housemate accelerates newly released individuals’ time to reconviction, compared to living with a non-convicted housemate (our reference category) and to living alone (H1). We condition on a rich set of control variables to reduce biases arising from observed confounding. Of course, our estimates should not be interpreted as causal effects of living arrangements on recidivism, as they may partly reflect unobserved differences between released individuals who lived with other former offenders and released individuals who did not. Second, we (a) explore how this relationship varies by whether the household composition includes both convicted and non-convicted individuals (H2) and (b) whether the association differs across familial status (H3 and H4). In supplementary analyses—to analyze the importance of the recency of housemates’ criminal history and the geographical clustering of convicted people—we explore how the relationship varies by (c) the length of time since the housemate’s last criminal conviction and (d) the concentration of convicted people in the neighborhood (see Fig. A1 and Table A9).

Statistical Model

We model the relationship between conviction and living arrangements by fitting semi-parametric hazard models to our survival data set. We observe individual \(i\) every day \(t\) since release from prison and until he/she recidivates, which is our failure event, or until the follow-up period ends at T = 1095 days. One important feature of the Cox proportional hazards model (Cox, 1972) is that it easily incorporates time-varying independent variables. Our model takes the form:

where \(a(t)\) is the baseline hazard that describes the risk of reconviction when all independent variables are set to 0; \(a\left(t\right)\) can be any function of time and is left completely unspecified in this semi-parametric model. \(C{H}_{i}(t)\) is a time-varying dummy variable equal to 1 if individual \(i\) lives with at least one formerly convicted housemate on day \(t\), and 0 otherwise. Similarly, \(L{A}_{i}(t)\) is a dummy variable equal to 1 if individual \(i\) lives alone on day \(t\), and 0 otherwise. Hence, the reference category is living with at least one non-convicted housemate. \({m}_{i}(t)\) is a dummy variable equal to 1 if individual \(i\) relocates to a new residence in day \(t\) and thus captures residential instability over time. \({{\varvec{x}}}_{{\varvec{i}}}\) is a vector of time-constant control variables, described above.

In our model, the main parameter of interest is \(\gamma ,\) which estimates the hazard of reconviction at time \(t\), given that the individual lives with a convicted housemate on day \(t\) and is still in the risk set, holding the values of the other variables constant. In our analyses, our interpretations are based on exponentiated coefficients (e.g., \(\mathrm{exp}(\widehat{\gamma })\)), which are equivalent to hazard ratios. We also calculate covariate-adjusted survival functions and plot their values against time, conditional on living with a convicted housemate \((C{H}_{i}\left(t\right)=1)\) and living with a non-convicted housemate \((L{A}_{i}\left(t\right)=0, C{H}_{i}\left(t\right)=0)\). We interpret these values as covariate-adjusted probabilities of avoiding reconviction until time \(t\), conditional on living arrangements (e.g., living with a convicted housemate) at time \(t\).

One key assumption in the Cox regression model is that the ratio of the hazards for any two observations at any point in time is constant, often referred to as the proportional hazards assumption. Despite the theoretical importance of this assumption, Cox regressions provide good approximations even when the assumption is violated (see Allison, 2014). In our robustness checks below, we test whether our results are robust to violations of the proportional hazards assumption.

Results

Table 1, which appeared at an earlier page, shows results to our initial question, about whom the newly released live with in the first 3 years after release. In addition, supplementary calculations (not shown) reveal that the average released individual in Denmark spent just 34.6% of his time in the first 3 years post-release residing alone, and only 18% lived alone throughout the entire 3-year period. For the entire sample, the average number of housemates on any given day was close to 1.5. Around 29% of individuals lived with a recently convicted housemate at some point during the 3-year follow-up period (i.e., resided with a person who had a conviction for an offense within the previous 2 years). The average formerly incarcerated individual in our data spent 15% of his time residing with at least one housemate with a recent criminal conviction, and, on average, the people in our data were exposed to 0.25 convicted housemates per day. Hence, newly released individuals were exposed to convicted housemates at a substantial rate, thereby motivating our aim to understand the consequences of their residential arrangements.

Newly released individuals also relied heavily on family for living arrangements, as expected. During our follow-up period, as much as 33.5% lived with at least one family member at some point in the 3 years immediately following prison release, including spouses and registered partners. And although most residency spells with family members included non-convicted family members, 4.4% of the newly released individuals in our data lived with a recently convicted family member at some point during our follow-up period, which illustrates the importance of looking also at the role of criminal history of family members for the reintegration process of newly released people.

Our analysis of selection into living arrangements three months and three years after prison release paints an expected picture: those who were married or in cohabiting relationships at baseline also had a higher chance of living with non-convicted housemates (their housemate after three months/years was likely to be the same spouse as at baseline). Females were more likely to live with recently convicted housemates, which could reflect both higher conviction rates among men in general (a randomly chosen male spouse is more likely to have a criminal record than a randomly chosen female spouse) and selection because women sentenced to imprisonment constitute a highly selective group. Socioeconomic background correlates negatively with living arrangement in the sense that lower income, weaker labor market attachment, and criminal history are predictive of living with recently convicted housemates. Importantly, however, the estimated correlations between living arrangements and the background variables are generally relatively weak (see Tables A4 and A5).

Living with Non-Convicted or Convicted Housemates

Table 2 reports our estimation results from the Cox regressions relating reconviction to living with a non-convicted versus convicted housemate, before and after adjusting for covariates (Models 1 and 2, respectively). Consistent with our first hypothesis (H1), our results show that living with a housemate with a criminal record substantially accelerates the time to reconviction. Compared to living with no convicted housemates, having at least one convicted housemate increases the hazard of reconviction by 128.3% prior to adjusting for covariates (Model 1) and 33.5% after adjusting for relevant covariates (Model 2). We also observe the benefit of living with non-convicted housemates relative to living alone, in that living alone increases the hazard of reconviction by 24.2% net of covariates (Model 2).

The large difference between the magnitude of the estimates in Models 1 and 2 shows that much of the relationship between living with a convicted housemate and reconviction is driven by selection into this type of living arrangement. Formerly incarcerated individuals who chose or could not avoid living with other individuals with a criminal past following release from prison differ from individuals who did not live with housemates with a criminal record. Yet, even after taking these differences into account by controlling for a large set of observed confounders, our estimates reveal that a substantial and statistically significant relationship between reconviction and living with convicted housemates remained.

To illustrate our findings, we plot survival functions in Fig. 1 based on Model 2 estimates, with survival curves evaluated at the means of our covariates. These curves show that the difference in the survival estimates between individuals living with convicted vs. non-convicted housemate(s) is roughly 7 percentage points (68.5% vs. 75.3%), and a difference of 5 percentage points between living alone vs. non-convicted housemates (70.4% vs. 75.3%). Whereas certainly multiple factors contribute to the risk of reconviction, our results nevertheless show that residential arrangements are crucial for the desistance (or persistence) of formerly incarcerated individuals. Whom released individuals end up living with after prison is strongly related to their subsequent criminal trajectories, even after adjusting for a wide range of observed characteristics.

Covariate-adjusted survival estimates from Cox regressions. Note: Survival estimates based on estimates from Table 2, Model 2. Control variables are set at their mean values (N = 232,544)

Living with both Convicted and Non-Convicted Housemates

To further examine hypothesis one as well as our second hypothesis, Fig. 2 plots hazard ratios from a model where we estimated the hazard of reconviction conditional on whether the released individual lives with convicted housemates only, a mix of both convicted and non-convicted housemates, or alone (see also Table A7 in the supplementary material). The hazard ratio compares the hazard rate for each of the three respective groups to the hazard rate for individuals residing with non-convicted housemates only. Again in support of our first hypothesis, our results show that living with convicted housemates exclusively increases the hazard of reconviction by around 44%, relative to living with non-convicted housemates exclusively. This percentage is higher than the figure reported in the previous section and in Table 2 (33.5%) because it distinguishes between only residing with one or more convicted housemates vs. residing with both convicted and non-convicted individuals. On this distinction, and consistent with our second hypothesis, our results reveal that the detrimental influences of living with formerly convicted housemates are diluted, although not completely eliminated, when living with a mix of convicted and non-convicted housemates. In this case, residing with a mix of convicted and non-convicted housemates increases the hazard of reconviction by a lesser 23% relative to residing exclusively with non-convicted housemates.

Covariate-adjusted survival estimates of the relationship between reconviction and the composition of housemates in terms of conviction status. Note: Reference category is “non-convicted housemate(s) only.” For estimates, see Table A7 in the online supplementary material (N = 232,544)

Living with Family Members

We now turn to results related to the importance of family members. Panel (a) in Fig. 3 plots hazard ratios from a model where we interacted the “convicted housemate(s)” variable with an indicator of whether the focal individual lives with at least one familial housemate (see also Table A8 in the supplementary material). Results in the top panel show that living with convicted housemates substantially increases recidivism, no matter whether the convicted housemates are family members or not. That being said, results in panel (a) also show that the risk of reconviction is lower for individuals living with convicted family members, compared to individuals living with convicted non-familial housemates. The hazard of reconviction increases by 17% for those living with convicted familial housemates, and by about 40% for those living with convicted non-familial housemates—both relative to living with non-convicted non-familial housemates.

Covariate-adjusted survival estimates of the relationship between reconviction and living with convicted family members. Notes: Reference category is “non-convicted non-familial housemate.” We also include a dummy for “lives alone.” For estimates, see Table A8 in the online supplementary material. All models include the full set of control variables set at their mean values. (a) Familial vs non-familial housemates. (b) Type of familial relation to housemate

Whereas our focus is primarily on the changes in the hazard of reconviction from residing with convicted housemates, to test our third hypothesis, we compare the hazard of reconviction among individuals residing with non-convicted family versus non-family members. Interestingly, we find that the hazard ratio for living with non-convicted familial housemates is indistinguishable from the baseline hazard (living with non-convicted non-familial housemates), implying that there is no additional “bonus” of residing with non-convicted family members. Hence, we do not find support for hypothesis three.

In panel (b), we explore whether the relationship between reconviction and living with (non-) convicted housemates varies by the type of family relation, where non-convicted non-family members are our reference category. Focusing on the black boxes, only for residence with a non-convicted spouse is the hazard of recidivism reduced compared to living with a non-convicted housemate of no family relation. This finding is consistent with our fourth hypothesis. The benefits of marriage may occur for a variety of reasons, including negative reinforcement of criminal behavior, and also because marriage tends to reduce the likelihood that an individual will associate with delinquent peers (Warr, 1998).

In contrast to living with a non-convicted spouse, residing with a non-convicted mother or sibling actually raises the probability of recidivism, albeit slightly, relative to a non-convicted non-familial relation. Hence, while numerous studies tout the purported benefits of family ties for criminal desistance, our study points to the importance of distinguishing the type of tie, and the fact that some family relations may not be as productive for desistance as residing with non-family housemates (non-convicted).

Focusing now on comparisons within family types, results for living with convicted family members are generally less precisely estimated, with wider confidence intervals. Nevertheless, our findings reveal higher recidivism hazards for individuals living with convicted spouses or siblings than for their counterparts living with non-convicted spouses or siblings. For individuals living with mothers or fathers, we do not find statistically significant differences between the recidivism hazards between those living with convicted vs. non-convicted mothers and fathers.

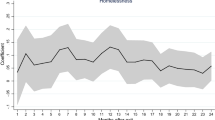

Living with Recently Convicted Housemates

In our main specification, the “convicted housemate(s)” dummy is equal to 1 if any of the focal individual’s housemates were convicted for a criminal offense within 2 years before the focal individual’s release from prison. To analyze whether reconviction depends on the recency of the housemate’s criminal offense, in a sensitivity analysis, we respecified this dummy variable 60 times (corresponding to 5 years) such that it is equal to 1 if the most recent criminal offense among any of the housemates was within 1 month before the focal individual’s release from prison in the first specification, 2 months in the second specification and so on. All models include the full set of covariates used in the main specification.

Results, which are shown in Fig. A1 in the supplementary material, reveal that housemates with more recent criminal records are indeed more detrimental than housemates with older criminal records. For instance, living with a housemate who committed a criminal offense 5 years (60 months) before the focal individual’s release from prison increases the hazard of reconviction by about 30%, relative to living with a non-convicted housemate, whereas living with a housemate with a recent criminal offense (e.g., 12 months before the focal individual’s release) increases the hazard of reconviction by about 35%. The width of the confidence intervals around the estimates from this exercise are, however, wide and leads us to be cautious about the firmness of this conclusion, just as we note that the impact of recency—an estimated five percentage points over the course of 5 years—according to this analysis is relatively minor (although the consistency of results across the figure are intriguing).

The Influence of Neighborhood Crime

For the purposes of analyzing whether our main results could be driven by an underlying clustering of newly released persons into high-crime neighborhoods, we operationally define neighborhoods as geographical grids of varying size that divide Denmark into 9086 residential areas with approximately 250 households in each grid (for details, see Damm et al., 2006). We then construct a monthly measure of the concentration of formerly convicted individuals in every neighborhood, \({C}_{j,m}=\left(\frac{{N}_{j,m}^{c}}{{N}_{j,m}}\right)\cdot \mathrm{10,000}\), where \({N}_{j,m}^{c}\) denoted the number of adults (aged 18—65) with a conviction for an offense that occurred within the previous two years, and \({N}_{j,m}\) denoted the number of adults in neighborhood \(j\) in month \(m\). We then split this variable into three terciles, with the first tercile having relatively few formerly convicted individuals among the neighborhood population, and the second and third terciles having increasing proportions of residents with past convictions.

Table A9 in the supplementary material reports estimation results from a model where we interact each tercile dummy with the housemate indicators to test whether the relationship between living with a (non-)convicted housemate varies by the concentration of formerly convicted individuals in the neighborhood. Our findings show that the likelihood of reconviction varies substantially by the concentration of former offenders in the neighborhood (as we would expect from existing research). Individuals who live in high concentration neighborhoods have a 26% increase in the hazard of reconviction, relative to individuals who reside in a low concentration neighborhood following release from prison. However, we find no significant interactions between the neighborhood concentration of former offenders and the convicted housemate indicators. The influence of a convicted housemate does not appear to vary by whether there are few or many other convicted individuals residing in the surrounding neighborhood, thus offering little evidence to undermine our main results.

Checking the Proportional Hazards Assumption

One implication of the proportional hazards assumption is that all explanatory variables are unrelated to any function of time. To test this assumption, Table A6 (panel B) in the supplementary material reports correlations between our independent variables and Schoenfeld residuals. Although many of the correlations are statistically significant, thereby violating the proportionality assumption, almost all correlations are very weak (less than 0.01). These significant correlations are thus most likely driven by the fact that we use full population data with a very large sample size. Despite this, we relax the proportionality assumption by interacting all independent variables with time in Table A6 (panel C) in the supplementary material. The coefficients on the time interactions are significant for most of our independent variables, and a model without time interactions will therefore theoretically violate the proportional hazards assumption. However, all interactions between the independent variables and time return a hazard ratio of 1.000, which, again, indicates that the statistically significant time correlations are driven by a large sample size, not by substantive issues with the model. Importantly, our main results are stable in this alternative specification. The reported hazard ratios on the main independent variables “Convicted housemate(s)” and “Lives alone” all have the same direction as in the main model. The smaller point estimates are driven by the fact that the time interactions are measured at a very small interval (one single day). To achieve appropriate comparisons to our main results, one should therefore add the time interactions to the point estimates on the main independent variables. For instance, multiplying the “Convicted housemate(s)” dummy with its time interaction (multiplied by the number of days since release from prison) would yield statistically significant results comparable to the ones observed in the main model. We therefore conclude that our main results are robust to relaxing the proportional hazards assumption.

Discussion

Taking seriously Elder’s (1997) conception of the interdependency of lives, in this study, we provided an in-depth examination of the residential situations of the formerly incarcerated in Denmark not just at the point of release, but over the first 3 years after prison. The population register data allowed us to examine the extent to which Danes who were newly released from prison resided with other individuals with criminal records after release and the consequences of co-residence with housemates with recent convictions. We paid particular attention to the importance of living with family members and given the richness of the data were also able to break down results by type of family member.

Our conclusion is that not only is living with recently convicted housemates and family members common among people who are released from prison, it is also consequential for criminal reconviction risks. Results from survival models showed that during periods of co-residence with recently convicted housemates, the rate of criminal offenses for which the focal person was later convicted accelerated. We also found that the negative consequences of residing with a convicted housemate can be buffered by also having exposure to individuals without a recent criminal record.

Living with family members constitutes a particularly interesting case because family has repeatedly been shown to be important for suppressing crime risks (Laub & Sampson, 2003). In agreement with much prior research (e.g., Bersani & Doherty, 2013), the influence of non-convicted spouses is particularly beneficial in helping the formerly incarcerated avoid reconviction. Interestingly, and in disagreement with our third hypothesis, residing with a non-convicted mother, father, or sibling does not reduce the hazard of recidivism relative to residing with a non-convicted friend or associate. Residing with convicted spouses or other family members appears more detrimental to the risk of recidivism than residing with individuals of any relation who have not been recently convicted. Yet if the choice is between residing with a family member with a recent conviction or a non-family peer or associate with a conviction, our results suggest that the most detrimental living arrangement may be the latter situation.

Whereas our results indicate that it could be beneficial for newly released persons to live with non-convicted family members, particularly spouses, during the reintegration process, it is important to keep in mind that residing with someone just out of prison is no easy task. Comfort (2016) characterizes the burdens that come with residing with persons who are under the purview of the criminal justice system, for example. She describes the burden as a twenty-hour-a-day job, which in a sense exploits the strength of familial bonds—family members feel obligated to help and support—to solve a range of psychological and practical tasks that could also have been solved by welfare agencies. This exploitation is stressful to family members, which could have long-term consequences, such as ones for health. And even though Comfort (2016) focuses on low-level offenders who cycle in and out of prison, we believe many of the points she raises could easily apply to living with other types of recently released persons. It thus seems pertinent to figure out how to strike a balance between benefitting from the strengths of family ties—especially the benefits of living with a non-convicted spouse—for the reintegration process while at the same time protecting the very same family members from some of the strains that could come with sharing residence with recently released people.

Given our results, what then are sensible approaches to facilitate the successful reentry and reintegration of formerly incarcerated individuals? For instance, can or should we regulate who a formerly incarcerated individual lives with post-release? In some contexts, such as in the USA, conditions of parole and community supervision can be used to stipulate who an individual can reside with and even where she or he can reside (Steiner et al., 2015). However, rather than advocate for a punitive, and ethically questionable, approach that criminalizes one’s ability to associate with friends and even family, we favor policy prescriptions that provide individuals the opportunity to make more productive choices about where and with whom to reside post-incarceration.

For instance, in the USA in 1996, President Clinton enacted the infamous “one-strike and you’re out” public housing policy. With this policy, families could be denied admission or evicted from public housing for the alleged criminal behavior of an occupant or a guest (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), 1997). The Obama presidency sought to reverse such punitive housing policies, including through creation of family reunification programs that provided a legal mechanism for the formerly imprisoned to move in with families in public housing (Bae et al., 2016). Our findings suggest that initiatives like these that promote housing with law-abiding family members, particularly spouses, can reduce the likelihood of recidivism.

Of course, housing policy is not the only mechanism that can facilitate family reunification. Whereas recent research shows that changing the amount of in-prison visitation with family members is not associated with a reduced probability of recidivism (Andersen et al., 2021; Lee, 2019), diversion programs in lieu of incarceration may be beneficial for maintaining prosocial familial bonds. As one example, research reveals that a punishment of electronic monitoring as an alternative to incarceration reduces the likelihood of reconviction (Di Tella and Schargrodsky, 2013; Henneguelle et al., 2016) and associated outcomes such as unemployment (Andersen & Andersen, 2014). Electronic monitoring may be consequential, in part, because it allows individuals to maintain familial relationships as well as current residence.

Returning to the discussion of housing, given that some housing situations, such as residing with convicted non-family members, can be quite detrimental to the formerly incarcerated, financial housing assistance may be crucial for avoiding such a situation. Indeed, research reveals that rental assistance programs for formerly incarcerated individuals, particularly individuals with very unstable housing situations, can significantly and substantially reduce the likelihood of recidivism (Kirk et al., 2018; Lutze et al., 2013; Palmer et al., 2019) as well as the risk of homelessness (Evans et al., 2016). While none of these studies explicitly tested whether housing assistance was efficacious because it helped individuals avoid detrimental housemates, the expansion of housing assistance and opportunities for people coming out of prison makes it less likely that individuals will be forced to reside in an undesirable housing situation.

Whereas we have emphasized policy solutions that incentivize and facilitate maintenance of pro-social ties, our findings also point to the detrimental consequences of practices, such as halfway houses, that concentrate individuals with relatively fresh criminal tendencies together (Doleac et al., 2020; Huebner & Berg, 2011; Kirk, 2015). On this point, Lee (Forthcoming) leverages the random assignment of prison case managers in Iowa, who vary in their likelihood of recommending either halfway house release or parole release to the community for state prisoners, to investigate the effects of residence in a halfway house (versus parole to the community) on recidivism. Consistent with the implications of our study, he finds that assignment to halfway houses increases the probability of reincarceration.

Several limitations apply to our study. First, Denmark has one of the lowest incarceration rates in the world with relatively short prison terms. By implication, incarceration tends to be reserved for individuals with relatively extreme criminal propensities, which is a potential limitation as it is unclear how results from this context translates to elsewhere.

A second key limitation of our study is one that plagues much of the research on peer influence—our inability to conclusively determine whether the observed association between exposure to criminal housemates and the behavior of the individual is due to peer influence or to selection. It may be the case that individuals most disposed to reoffend seek out individuals with criminal records to reside with, such that exposure to someone with a criminal record has little to no causal influence. Results from our regressions of covariates on living arrangements 3 months and 3 years after release (Tables A4 and A5)—our gauge of the extent of selection issues—indicates some correlation between background characteristics and living with recently convicted housemates, but point estimates are generally small. Although we cannot rule out selection bias, we would reiterate that the breadth and depth of the population register data we used throughout the analyses help reduce the likelihood of selection issues. For instance, we adjusted for background characteristics in the form of the number of previous convictions and incarcerations, employment, education, family characteristics, and demographic background.

A third limitation is that we are only assessing direct ties in the form of housemates. However, it may be the case that indirect ties also increase the likelihood of recidivism. For instance, Andersen (2017) showed that having a brother-in-law with a criminal conviction, whether the brother-in-law lives nearby or more distant, raises an individual’s likelihood of a criminal conviction. And the empirical literature on peer effects has shown that the influence of friends of friends as well as friends of romantic partners can be quite consequential (e.g., Kreager & Haynie, 2011).

The fourth and last limitation concerns the nature of our data. As in many studies relying upon administrative data, we were limited by the fact that our dependent variable, reconviction, represented the outcome of behavior and criminal justice practices. In contrast, we would ideally have a distinct measure of reoffending. However, such a measure was not available to us. Similarly with our key independent variable, we would be able to provide a more precise test of our hypotheses if we were to have a measure of housemate offending behavior rather than conviction. It could be the case that some proportion of who we termed “non-convicted housemates” are in fact active offenders who have avoided arrest and conviction. In this sense, some unknown number of “non-convicted housemates” may be just as, or more, criminally inclined as some “convicted housemates,” but the latter were more likely surveilled by the police and parole services and more likely to come into contact with the criminal justice system. Whereas these limitations prevent us from making completely definitive statements about the relationship between the behavior of housemates and the behavior of formerly incarcerated individuals, we would nevertheless suggest that this type of unobserved heterogeneity would in fact bias the results downward, making our findings stand even stronger. The breadth and depth of administrative register data used in this study provides numerous advantages for examining the connection between living arrangements and family ties for newly released individuals’ risk of criminal reconviction.

References

Akers, R. L. (1973). Deviant behavior: A social learning approach. Wadsworth.

Allison, P. D. (2014). Quantitative applications in the social sciences: Event history and survival analysis. SAGE Publications Inc.

Andersen, L. H. (2017). Marriage, in-laws, and crime: The case of delinquent brothers-in-law. Criminology, 55, 438–464.

Andersen, L. H., & Andersen, S. H. (2014). Effect of electronic monitoring on social welfare dependence. Criminology and Public Policy, 13, 349–380.

Andersen, S. H., Andersen, L. H., & Skov, P. E. (2015). Effect of marriage and spousal criminality on recidivism. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 496–509.

Andersen, L. H., Fitzpatrick, M., & Wildeman, C. (2021). “How does visitation affect incarcerated persons and their families? Estimates using exogenous variation in visits driven by distance between home and prison.” Journal of Human Resources. OnlineFirst.

Andersen, L. H. (2018). Danish register data: Flexible administrative data and their relevance for studies of intergenerational transmission. In V. I. Eichelsheim, & S. G. A. van de Weijer (Eds.), Intergenerational continuity of criminal and antisocial behaviour: An international overview of studies, (1st ed., pp. 28–43). Abingdon: Routledge.

Anker, A. S. T., & Andersen, L. H. (2021). Does the intergenerational transmission of crime depend on family complexity? Journal of Marriage and Family, 83, 1268–1286.

Bae, J., diZerega, M., Kang-Brown, J., Shanahan, R., & Subramanian, R. (2016). Coming home: An evaluation of the New York City housing authority’s family reentry pilot program. Vera Institute.

Bersani, B. E., & Doherty, E. E. (2013). When the ties that bind unwind: Examining the enduring and situational processes of change behind the marriage effect. Criminology, 51, 399–433.

Bersani, B. E., & Doherty, E. E. (2018). Desistance from offending in the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Criminology, 1, 311–334.

Chamberlain, A. W., & Wallace, D. (2016). Mass reentry, neighborhood context and recidivism: Examining how the distribution of parolees within and across neighborhoods impacts recidivism. Justice Quarterly, 33, 912–941.

Comfort, M. (2016). “A twenty-hour-a-day job”: The impact of frequent low-level criminal justice involvement on family life. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, 665, 63–79.

Cox, D. R. (1972). Regression models and life-tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 34(2), 187–220.

Damm, A. P., & Dustmann, C. (2014). Does growing up in a high crime neighborhood affect youth criminal behavior? American Economic Review, 104, 1806–1832.

Damm, A. P., Schultz-Nielsen, M. L., & Tranæs, T. (2006). En befolkning deler sig op? Copenhagen, Denmark: ROCKWOOL Foundation Research and Gyldendal.

Danish Ministry of Justice. (2016). Etnicitet og statsborgerskab. Justitministeriet Direktoratet for Kriminalforsorgen Koncernledelsessekretariaet: Jura og statistik. Available at: https://www.kriminalforsorgen.dk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/etnicitet-og-statsborgerskab-2015-udgivet-2016.pdf.

Danish Prison and Probation Service. (2019). Afsonere. Guide til myndighedssamarbejde. Copenhagen, Denmark: Danish Prison and Probation Service.

Danish Prison and Probation Service. (2020). Statistik 2019. Copenhagen, Denmark: Danish Prison and Probation Service.

Di Tella, R., Schargrodsky, E. (2013). Criminal recidivism after prison and electronic monitoring. Journal of Political Economy, 121, 28–73.

Doleac, J. L., Temple, C., Pritchard, D., & Roberts, A. (2020). Which prisoner reentry programs work? Replicating and extending analyses of three RCTs. International Review of Law and Economics, 62, 1–16.

Durose, M. R., & Antenangeli, L. (2021). Recidivism of prisoners released in 34 states in 2012: A 5-year follow-up period (2012 to 2017). US Department of Justice.

Elder, G. H., Jr. (1997). The life course and human development. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 939–991). Wiley.

Evans, W. N., Sullivan, J. X., & Wallskog, M. (2016). The impact of homelessness prevention programs on homelessness. Science, 353, 694–699.

Fair, H., & Walmsley, R. (2021). World prison population list (Thirteenth). Institute for Criminal Policy Research.

Farrington, D. P. (2011). Families and crime. In J. Q. Wilson & J. Petersilia (Eds.), Crime and public policy (pp. 130–157). Oxford University Press.

Fontaine, J., & Biess, J. (2012). Housing as a platform for formerly incarcerated persons. Urban Institute.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma. Prentice-Hall.

Harding, D. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Herbert, C. (2013). Home is hard to find: Neighborhoods, institutions, and the residential trajectories of returning prisoners. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 647, 214–236.

Harding, D. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Wyse, J. J. B. (2019). On the outside: Prisoner reentry and reintegration. University of Chicago Press.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Wiley.

Henneguelle, A., Monnery, B., & Kensey, A. (2016). Better at home than in prison? The effects of electronic monitoring on recidivism in France. Journal of Law and Economics, 59, 629–667.

Herbert, C. W., Morenoff, J. D., & Harding, D. J. (2015). Homelessness and housing insecurity among former prisoners. The Russell Sage Foundation Journal, 1, 44–79.

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of delinquency. University of California Press.

Horney, J., Osgood, D. W., & Marshall, I. H. (1995). Criminal careers in the short-term: Intra-individual variability in crime and its relation to local life circumstances. American Sociological Review, 60, 655–673.

Huebner, B. M., & Berg, M. T. (2011). Examining the sources of variation in risk for recidivism. Justice Quarterly, 28, 146–173.

Jacobs, L. A., & Gottlieb, A. (2020). The effect of housing circumstances on recidivism: Evidence from a sample of people on probation in San Francisco. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 47, 1097–1115.

Kirk, D. S. (2015). A natural experiment of the consequences of concentrating former prisoners in the same neighborhoods. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, 6943–6948.

Kirk, D. S. (2019). Where the other 1 percent live: An examination of changes in the spatial concentration of the formerly incarcerated. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 5, 255–274.

Kirk, D. S. (2020). Home free: Prisoner reentry and residential change after Hurricane Katrina. Oxford University Press.

Kirk, D. S., Barnes, G. C., Hyatt, J. M., & Kearley, B. W. (2018). The impact of residential change and housing stability on recidivism: Pilot results from the Maryland opportunities through vouchers experiment (MOVE). Journal of Experimental Criminology, 14, 213–226.

Kreager, D. A., & Haynie, D. L. (2011). Dangerous liaisons? Dating and drinking diffusion in adolescent peer networks. American Sociological Review, 76, 737–763.

La Vigne, N. G., Visher, C., & Castro, J. (2004). Chicago prisoners’ experiences returning home. Urban Institute.

Langsted, L. B., Garde, P., & Greve, V. (2011). Criminal law in Denmark. Third (Revised). Kluwer Law International.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives. Harvard University Press.

Lee, L. M. (2019). Far from home and all alone: The impact of prison visitation on recidivism. American Law and Economics Review, 21, 431–481.

Lee, L. M. Forthcoming. (n.d.) Halfway home? Residential housing and reincarceration. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.

Leverentz, A. (2014). The ex-prisoner’s dilemma: How women negotiate competing narratives of reentry and desistance. Rutgers University Press.

Leverentz, A. (2022). Intersecting lives: How place shapes reentry. University of California Press.

Lutze, F. E., Rosky, J. W., & Hamilton, Z. K. (2013). Homelessness and reentry: A multisite outcome evaluation of Washington State’s reentry housing program for high risk offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41, 471–491.

Lyngstad, T. H., & Skardhamar, T. (2011). Nordic register data and their untapped potential for criminological research. Crime and Justice, 40, 613–645.

McGloin, J. M. (2009). Delinquency balance: Revisiting peer influence. Criminology, 47, 439–477.

McGloin, J. M., & Thomas, K. J. (2019). Peer influence and delinquency. Annual Review of Criminology, 2, 241–264.

Miller, R. J. (2021). Halfway home: Race, punishment, and the afterlife of mass incarceration. Little, Brown and Company.

National Research Council. (2007). Parole, desistance from crime, and community integration. Committee on Community Supervision and Desistance from Crime. Committee on Law and Justice, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Newcomb, T. M. (1953). An approach to the study of communicative acts. Psychological Review, 60, 393–404.

Osgood, D. W., Wilson, J. K., Bachman, J. G., O’Malley, P. M., & Johnston, L. D. (1996). Routine activities and individual deviant behavior. American Sociological Review, 61, 635–655.

Palmer, C., Phillips, D. C., & Sullivan, J. X. (2019). Does emergency financial assistance reduce crime? Journal of Public Economics, 169, 34–51.

Pedersen, N. J. M., Jensen, J. K., Ruge, M., & Niels B. G. P. (2020). Undersøgelse af kvaliteten af kommunernes arbejde med bopælsregistrering i CPR. Vive – the national research center for social science.

Piquero, A. R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P., & Haapanen, R. (2002). Crime in emerging adulthood. Criminology, 40, 137–170.

Rocque, M. (2017). Desistance from crime: New advances in theory and research. Palgrave Macmillan.

Rotger, G. P., & Galster, G. C. (2019). Neighborhood peer effects on youth crime: Natural experimental evidence. Journal of Economic Geography, 19, 655–676.

Ruge, M., Petersen N. B. G., Jensen J. K., & Pedersen, N. J. M. (2020). Undersøgelse af kvaliteten af bopælsregistreringen i CPR. Registerbaseret tillægsanalyse. Vive – the national research center for social science.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1993). Crime in the making: Pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University Press.

Sampson, R. J., Winship, C., & Knight, C. (2013). Translating causal claims. Criminology and Public Policy, 12, 587–616.

Statistics Denmark. (2021). RECIDIV1: Persons by Sex, Age, Duration until recidivism, index penalty and index offence. Copenhagen: Statistics Denmark. Accessed 8 June 2021. Available at: https://www.statbank.dk/tabsel/192505.

Steiner, B., Makarios, M. D., & Travis, L. F., III. (2015). Examining the effects of residential situations and residential mobility on offender recidivism. Crime and Delinquency, 61, 375–401.

Sutherland, E. H. (1947). Principles of criminology (4th ed.). J.B. Lippincott.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). (1997). Meeting the challenge: Public housing authorities respond to the “one strike and you’re out” initiative. HUD.

UK Ministry of Justice. (2021). Proven Reoffending Statistics: October to December 2019. Ministry of Justice.

Visher, C., & Courtney, S. M. E. (2006). Cleveland prisoners’ experiences returning home. Urban Institute.

Visher, C., La Vigne, N., & Travis, J. (2004). Returning home: Understanding the challenges of prisoner reentry, Maryland pilot study: Findings from Baltimore. Urban Institute.

Warner, C., & Remster, B. (2021). Criminal justice contact, residential independence, and returns to the parental home. Journal of Marriage and Family, 83, 322–339.

Warr, E. M. (1998). Life-course transitions and desistance from crime. Criminology, 36, 183–216.

Warr, E. M. (2002). Companions in crime: The social aspects of criminal conduct. Cambridge University Press.

Washington State Institute for Public Policy. (2019). Therapeutic community (in the community) for individuals with co-occurring disorders. Available at: https://www.wsipp.wa.gov/BenefitCost/ProgramPdf/201/Therapeutic-communities-in-the-community-for-individuals-with-co-occurring-disorders

Western, B. (2018). Homeward: Life in the year after prison. Russell Sage.

Western, B., Braga, A. A., Davis, J., & Sirois, C. (2015). Stress and hardship after prison. American Journal of Sociology, 120, 1512–1547.