Abstract

Purpose

Motivated by offender typology debates, we evaluate whether adult offending trajectories can be predicted from adolescent risk factors.

Methods

Drawing on data from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development (N = 411), we use person-centered, latent class cluster analysis (LCCA) to identify groups of respondents with similar behavioral, social, and psychological profiles measured in adolescence. We then use hierarchical linear models to estimate the criminal trajectories associated with each cluster using annual offending measures from 19 to 50 years of age. This offers a test of whether prospectively defined crime trajectories validate theoretical conceptions of qualitatively distinct offender groups.

Results

Our LCCA identified four clusters of boys with varying patterns of adolescent characteristics. The offending trajectories associated with these clusters differed in magnitude rather than shape. While we were able to identify a subgroup of offenders whose criminal offending remained relatively high over the life course, significant differences across subgroups were varied and dissipated after young adulthood. All offending trajectories followed the familiar age-crime curve, characterized by a sharp decline in offending in early adulthood.

Conclusions

Our findings support multidimensional interventions that would offset the constellations of behavioral, psychological, and social setbacks adolescents face. At the same time, our findings undermine the notion that qualitatively distinct patterns of offending can be prospectively identified and suggest that the processes behind criminal decline over the life course are generalizable across offenders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Problem behaviors tend to concentrate during the adolescent period of the life course. The prevalence of deviant behavior is sufficiently high in adolescence to suggest that deviance is developmentally normative [32, 31]. While the majority of delinquent adolescents do not go on to display problem behavior past early adulthood [50], a small minority of offenders account for a disproportionate amount of crime across the entire life course (see e.g., [13, 59, 61, 64]). These findings form the foundation of an important theoretical debate. Specifically, a fundamental question remains as to whether this minority represents a categorically distinct group of “persistent” or “career” offenders with a non-normative etiology [31, 43] or whether they simply represent the tail end of a continuous offender distribution [20, 42, 53].

This theoretical debate has practical implications for those concerned with identifying and preventing criminal persistence. If offenders fall into distinct groups with predictably different trajectories and potential for change, we would expect interventions to target these differences. Adding challenge to this debate is the fact that while chronic or life-course-persistent offenders may be distinguishable on the basis of their early criminal onset and prolonged involvement in crime, their offending behavior is more difficult to distinguish from the general offending population during adolescence [34], the point at which many come to the attention of the criminal justice system and/or practitioners. Recent scholarship suggests, however, that a range of problems including drug abuse, early sexual behavior, temperament and personality problems, and low academic achievement co-occur and accumulate within individuals and predict later-life outcomes [17, 36]. This broader set of problems may be useful in differentiating adolescents on a normative developmental trajectory from those situated on a more problematic trajectory.

With this research, we evaluate whether adolescent problems can effectively predict offender groups in general and “diagnose” life-course-persistent offending more specifically. We innovate on group-based strategies that have become common in life-course criminology by integrating a diagnostic framework borrowed from the health sciences literature. First, we assess the extent to which a variety of problematic behavioral, social, and personality characteristics, measured in mid to late adolescence, cluster together to form qualitatively distinct groups of adolescents. In contrast to variable-centered approaches, which assess the relative contribution of individual variables to a given outcome, we use a person-centered approach to identify groups of adolescents who look similar to one another across a broad set of characteristics [4, 30, 54]. While useful summaries in and of themselves, we test the practical and theoretical application of the clusters by examining the adult offending trajectories associated with each of the groups.

Unlike previous variable-based and retrospective modeling approaches, the person-centered, prospective strategy employed here maps well onto real-world scenarios in which adolescents are assessed by practitioners. In such scenarios, practitioners typically have limited knowledge of early childhood factors (e.g., exposure to biological, environmental, and social risks prenatally or during infancy; neuropsychological deficits; and early childhood family dysfunction). We evaluate whether adolescent presentations of problematic behavioral, social, and personality characteristics are useful in diagnosing criminal persistence from young adulthood through age 50.

Beyond the potential practical application of this strategy, our work makes a theoretical contribution by testing whether we can predict distinct offending groups based on characteristics measured during adolescence. We then evaluate the extent to which the criminal trajectories validate theoretical conceptions of offender groups. Before discussing the details of this research, we begin with a brief review of the debate surrounding the identification of persistent career criminals. We then review the empirical work and analytic strategies that have been employed to model offending trajectories and identify a subset of persistent, chronic offenders.

Literature Review

Heterogeneity in Offending or Distinct Groups of Offenders

Whether distinct groups of offenders exist has long been a contentious criminological debate. Of particular interest are the relatively few offenders whose criminal behavior persists into adulthood rather than adhering to the norm of desistance in late adolescence or early adulthood. One side of the debate views these offenders as a qualitatively distinct “kind” of offender, popularly called “career criminals” or “life-course persisters” [39, 11, 31, 64]. These discrete categories of offenders are expected to differ not only in the degree and in the kind of criminal pursuits in which they are involved but also in their etiology. Career criminals or persistent offenders are set apart by the early onset of their misbehavior and, as the name aptly applies, their persistence of high-level offending beyond adolescence and through the life course. While persistence implies consistently high absolute levels of offending, softer interpretations of the term allow that the offending rate of these individuals may decline with age yet will remain high relative to others [33, 53]. The potential of identifying and classifying subgroups of offenders in the population has proven to be highly seductive; should certain characteristics discriminate between different types of offenders, then the possibilities of early intervention and prevention of crime are large [10, 19].

The other side of the debate views persistent offenders as representing nothing more than the tail end of a continuous offender distribution [51, 58, 47, 53, 20]. Denouncing arguments for distinct offender groups, variability in offending is instead the result of variation in an underlying propensity or latent causal dimension [41]. In general, while there is agreement that significant heterogeneity in offending exists, the extent to which this heterogeneity represents qualitatively distinct offender groups, differentiated by their causes of offending, is debatable.

Distinguishing Offending Trajectories: Childhood Indicators

Researchers arguing that persistence in offending characterize a unique subset of individuals in the population point to a number of factors found to distinguish them from their peers. One of the strongest predictors of long-term, serious offending is an early age of onset in criminal behavior [14, 27, 45, 57]. Persistent offenders experience higher levels of impulsivity, more aggressive attitudes, less social closeness, and lower cognitive capabilities than their peers do even in childhood [34, 56, 8, 46, 31]. Childhood problem behaviors can accumulate and set the stage for challenges in adolescence and beyond by severing informal social bonds and making it harder for individuals to take advantage of social network, school, and employment opportunities [52, 6, 7]. Importantly, despite evidence of the continuity that exists between childhood misbehavior and adult criminality, attempts to identify persistent offenders on the basis of childhood behavior have exposed the oft-cited paradox: while “…adult antisocial behavior virtually requires childhood antisocial behavior…most antisocial children do not become antisocial adults” [50]. This suggests that if individuals become set on persistent trajectories, this must occur after childhood.

More fundamentally, measures of age of onset and other early childhood characteristics are difficult to obtain. Longitudinal studies that follow the same respondents from early childhood to late adulthood are rare, expensive, and logistically difficult. Lack of early assessment is a challenge for psychiatric clinicians as well. The DSM-V, which guides clinical practice, defines early onset as occurring before age 10. Few children receive official attention at such a young age, and even fewer from the disadvantaged social environments thought to contribute to early and persistent offending as these children lack the financial resources sometimes needed to procure clinical intervention. Notably, Moffitt has acknowledged the difficulty in distinguishing among offender types during adolescence noting, “(w)hat is needed is information about how childhood-onset and adolescent-onset conduct disorder can be differentiated on the basis of current presenting [adolescent] behavior” (1996: 403).

Distinguishing Offending Trajectories: Adolescent Indicators

The challenges in distinguishing among offender types are not limited to childhood. During adolescence, persistent offenders may be “difficult to distinguish on most delinquency indicators” from their peers as rates of offending among adolescents in general peak during this developmental stage ([34], pp. 403). An exception is violent offending, which is more pervasive among persisters [34, 35, 56].

White and colleagues (2001) investigated whether persistent offenders could be isolated on the basis of adolescent indicators using data from the Rutgers Health and Human Development Project (HHDP) containing information on nearly 700 males followed from early adolescence through to adulthood. They examined the predictive ability of early neuropsychological problems, personality characteristics (i.e., impulsivity, harm avoidance, sensation seeking), and family adversity (i.e., socioeconomic status, family structure, parental hostility). The only factor found to distinguish this group was a measure of disinhibition (i.e., sensation seeking) whereby persistent delinquents reported higher levels of disinhibition in adolescence. Wiesner and Capaldi [63] also found little evidence that adolescent predictors could distinguish persistent offenders. Using data from the Oregon Youth Study, a longitudinal study of 204 at-risk boys, chronic offenders had higher rates of deviant peer affiliation, engaged in risky sexual behavior, and more substance use in adolescence compared to their peers who were desisting from crime in young adulthood. More recently, Bersani et al. [3] assessed the ability of early-onset, chronic offending in adolescence, low intelligence, and psychological instability to predict life-course offending trajectories for nearly 5000 individuals convicted in the Netherlands in 1977. Despite using a variety of analytic approaches, both prospective and retrospective, their results demonstrated the difficulty in predicting offender groups. Thus far, efforts aimed at identifying persistent offenders based on early life-course risk factors have reaped limited success.

Identifying Distinct Offender Groups

Methods of identifying distinct offender groups often begin with the assumption that offending trajectories are clustered rather than continuously distributed and further require that the number of clusters be decided a priori. To accomplish this, the authors subjectively construct offender groups and assign membership. For example, the most problematic offenders might be those who score high on a teacher assessment scale [21], rank in the top five percent of the arrest frequency distribution [45], or fall one or more standard deviations above the mean in self-reported delinquency [34].

In an effort to move beyond these subjective definitions, Nagin and colleagues ([38]; [39]) embraced latent class modeling to categorize criminal histories. This approach allows the existence and number of groups to be formally tested. Nagin et al. [39] conclude, for instance, that four groups are necessary to summarize non-offenders, adolescence limited, high chronics, and low chronics. This methodological advance has led to an abundance of studies using latent class trajectory modeling [44, 23]. A standing criticism of latent class trajectory modeling, however, is that it requires the benefit of hindsight. This has left some researchers to charge that typology groups cannot be “accurately or meaningfully predicted in the prospective sense” and that desistance in early adulthood is the norm for the continuum of offenders ([53], p. 31; see also [40]).

The Current Study

The present paper gets around the methodological criticisms central to the typology debate. First, we employ a person-centered approach, which allows us to examine how adolescent risk factors cluster together, rather than studying them as isolated characteristics in a variable-centered framework [30, 54]. We achieve this by first using latent class analysis to test whether a set of behavioral, psychological, and social problems is useful in describing “types” or similarly situated clusters of youth in an at-risk sample. This focus on the “person as a whole” [9] directly maps on to theories of cumulative disadvantage and cumulative continuity (e.g., [31, 52]). Moreover, latent class analysis allows interactions between risk factors, interactions which would greatly complicate interpretation of variable-centered results [2]. With the goals of adolescent intervention and treatment in mind, it is important to consider the typical clusters of setbacks and psychological problems adolescents face so that multidimensional interventions can take place to address the person as a whole rather than one problem at a time. For this reason, LCA offers a clear advantage over variable-centered approaches in allowing one to focus on prototypical patterns in the data [2].

Second, we avoid the a priori assumption that a persistent subgroup exists and the reliance on subjective and retrospective definitions to identify these offenders. Once we identify the clusters of adolescents, we estimate the criminal trajectories associated with each cluster using annual offending data spanning age 19 to 50 years. This permits a test of whether these personality problems and life-course snares are helpful in prospectively identifying qualitatively distinct subgroups of offenders.

Our analytic procedure is analogous to a diagnostic framework found in the health sciences literature where latent class techniques are increasingly promoted as an important tool to validate diagnostic criteria [65, 18]. Among other conditions, researchers have used latent class analysis to analyze diagnostic categories of diabetes [22], psychopathy [55], and schizophrenia [65]. Following these works, our analysis consists of two stages: a cluster derivation stage and a cluster validation stage. We derive clusters based on adolescent risk factors. We then model the associated offending trajectories and test whether the trajectories validate theoretical conceptions of distinct offending patterns.

Data and Measures

The Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development began in 1961 when the respondents were 8 and 9 years old. Most (n = 399) were enrolled in one of six state primary schools in South London. An additional 12 were sampled from a population of boys enrolled in a local school for the “educationally subnormal” to render the original sample of 411 boys representative of the population of boys living in the area. The boys were interviewed at about ages 8, 10, 14, 16, 18, 21, 25, 32, and 48. At age 21, convicted delinquents were targeted and sampled along with a similarly sized but randomly selected sample of not-convicted youths. The sampling procedure targeted working class males. Because the urban poor are disproportionately likely to be involved in serious offending, these data are more likely than data drawn from the general population to include serious offenders.

Variables

Extant empirical and theoretical work [31, 16, 56, 62] aimed at distinguishing persistent offenders guided the selection of variables we use to identify clusters of boys with similar adolescent characteristics. These indicator variables consist of behavioral, personality, and social life-course snares. We limit our variables to those available during adolescence, as we wish to simulate a scenario whereby the boys would come to official attention during adolescence and many childhood measures would be unavailable. We draw primarily from the 18-year-old interviews to capture late adolescence, the age at which criminal offending peaks. When variables are not available at age 18, we use the oldest adolescent age at which the variables were measured and note the age at which the data were obtained in the variable description below. We do include childhood convictions, as these would realistically be available to practitioners.

Behavioral Indicators

Violent offending is a dichotomous measure of whether the boys were ever convicted of robbery, violence, offensive weapon, or threats by age 18. All conviction data were obtained through the Criminal Record Office in London. These include convictions for all serious offenses committed in Great Britain or Ireland and exclude minor offenses such as drunkenness and traffic infractions. Twenty boys had been convicted for a violent offense by 18. Because just four of the boys were convicted more than once during these juvenile years, we do not include a frequency measure.

Childhood offending measures whether the boys were convicted of a serious crime by age 13. Twenty boys were convicted of a crime by 13. Just six respondents were convicted of more than one offense by their teenage years. Due to this data sparsity, we include only a dichotomous measure of childhood offending.

Psychological/Personality Indicators

Low IQ identifies respondents who, at age 14, scored below 90 on Raven’s Progressive Matrices non-verbal test, which is designed to measure reasoning ability [49].

Aggressive Attitudes At age 18, the boys were asked to indicate whether they agreed or disagreed with 11 statements included on an aggressive attitude questionnaire. These 11 items constitute an aggression scale, which we list in Table 1. Our measure identifies boys with aggressive attitudes scoring higher than the sample median.

High Impulsivity At 16, the boys completed the Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI; [12]). As part of the EPI, they were asked to indicate whether they agreed or disagreed with statements included in the impulsivity subscale. The items making up the impulsivity subscale are listed in Table 1. High impulsivity identifies boys scored above the sample median.

Low Sociability Low sociability indicates respondents who scored below the sample median on the sociability subscale of the EPI at age 16 [12]. The items making up the sociability subscale are listed in Table 1.

Social/Life-Course Snares

Teenage pregnancy is a dichotomous indicator identifying respondents who, at their 18-year-old interview, self-reported having gotten a girl pregnant.

Leaving school is a dichotomous variable identifying boys who left school and had not taken any certification exams by their 18-year-old interview. Students who leave school without passing any examinations are comparable to the United States high school dropouts in the sense that they left with no credentials [24].

Habitual drug use is a self-reported indicator of whether the respondent was habitually using drugs at the time of his 18-year-old interview. Respondents who had taken drugs five times or more, including at least once in the last 6 months, are defined as habitual users.

Poor Parental Bonds At age 18, the London boys were asked three questions that tapped their relationship with their parents. They were asked about the extent to which they agreed with their mother, the extent to which they agreed with their father, and whether they wanted to live away from home because of tension with their parents. Together, these assess their relationship with their parents. This measure identifies those whose parental bonds were poor.

Delinquent Friends At 18, respondents were asked whether any of their friends had participated in 38 different delinquent acts. This variable indicates respondents whose friends’ deviant participation fell above the sample median.

Adult Convictions

Convictions

We use counts of convictions accrued from ages 19 through 50 to assess adult criminal trajectories. Lengthy prison sentences were less common for these men than they might be for criminally active men in the USA. Just 44 (26.3 %) of the 167 ever-convicted offenders in the sample served time in prison or in a detention center by the time they were 50 years old [15]. These 44 men were incapacitated for an average of 1.3 years. Twenty-five of the 411 men were deceased or had emigrated and were not followed to age 50 [15]. To assess the impact of this attrition, we also studied patterns of offending among respondents who remained in the study for the entire period (not shown). The patterns are entirely consistent with the results shown in this paper, suggesting that attrition did not substantially alter the patterns.

Methods

Our analysis consists of a two-stage process including a cluster derivation stage and a cluster validation stage. In the cluster derivation stage, we use latent class cluster analysis (LCCA) to identify groups of adolescents with similar patterns of personality and behavioral risk factors. LCCA is a model-based clustering approach in which a categorical latent variable is assumed to explain all of the association between the indicator variables (i.e., the behavioral and personality indicators). The identified categories are mutually exclusive and exhaustive, and each category represents a latent class (or cluster). We use model-based probabilities to guide our decisions about how many latent classes should be included in the model. We assign each respondent to the class to which he has the highest probability of belonging. As described above, these include dichotomous indicators of low IQ, violent conviction, childhood conviction, teenage pregnancy, school dropout, habitual drug use, and poor parental bonds. We split continuous indicators (i.e., pro-aggressive attitudes, low sociability, impulsivity, peer delinquency) at the median and identified respondents scoring above the sample median as higher risk than their peers. The decision to assign risk based on the median value is typical [25, 34, 53].Footnote 1

In the cluster validation stage, we assess the extent to which the clusters identified match theoretical conceptions of criminal offender groups, including the notion of a persistent subgroup. Because our measures of offending are nested within individuals (i.e., repeated measures of offending at each age), we model conviction trajectories for each cluster using hierarchical linear modeling [48, 26] and predict the offending trajectories of each of the derived clusters.Footnote 2 To capture the complexity or change of the offending trajectories, we specify a third-order polynomial. We assume random effects for the intercept and the linear or first-order polynomial (i.e., age), and because we found no significant variation, we assume fixed effects for age squared and age cubed. Finally, we conduct one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests to investigate whether the frequency of criminal offending differs significantly across clusters at each age (19–50).

Results

First Stage Analysis: Cluster Derivation

We began by estimating models consisting of one to six clusters using all 11 personality and behavioral risk factors. A central assumption of latent class analysis is that the indicators are independent of one another beyond their shared relationship with the unobserved latent variable. We relax this assumption to allow correlation between childhood offending (measured through age 12) and violent offending (measured through age 17). The p values associated with models 1 to 6 when including all 11 indicators were less than 0.05, indicating poor overall model fit. Wald tests to evaluate whether individual indicators were helpful in discriminating between the clusters showed that violent convictions and teenage pregnancy were statistically insignificant across most of the models.Footnote 3 We re-estimated the models without these indicators; we display the fit statistics associated with the one- to six-cluster models in Table 2 (models 1–6, respectively). Additional classes did not offer new substantive differences in the patterns we observed, and their fit statistics are not shown. Respondents with missing data on any of the indicator variables were left out of the analysis, leaving a sample size of 376. The p values suggest that models consisting of two or more clusters adequately fit the data and offered improved fit over the null model.

Recent simulation studies have found that Bayesian information criterion (BIC) typically underestimates the number of classes, while the Akaike information criterion (AIC) overestimates the number of classes [28, 1], but that the AIC statistic generally outperforms the BIC statistic [5]. Table 2 presents both, as well as the AIC3, which Lin and Dayton ([28] and Vermunt et al.[60]) suggest as a good compromise in estimating the number of classes that should be represented in latent class analysis. The BIC statistic is lowest for the two-cluster model (3991.03), while the AIC statistic is lowest for the five-cluster model (3874.92). The AIC3 is lowest for the four-cluster model (3915.34). Deviance-based tests comparing the deviance statistics (−2LL) of competing models suggest that the model fit improves with each additional cluster though the four-cluster model, but the five-cluster model does not offer significantly improved fit over the four-cluster model. An additional consideration was our aim to identify a small but persistent group of offenders thought to be masked in aggregate statistics that include the more common adolescent-limited offenders. We preferred a higher-class solution to solutions with fewer clusters because it would improve the possibility of isolating this small group of offenders. Together, these criteria pointed to the four-cluster solution as best fitting.

We stress that these clusters are summaries of the data, rather than real or fixed entities. We follow the literature in using terms like “membership” and “belonging” to describe the relationship between the respondents and the four classes. In actuality, there is a subjective element involved in identifying the number of clusters that should be represented in the model, and each respondent is assigned to the cluster to which he has the highest probability of belonging. The average posterior probabilities of assignment to these clusters are 0.99, 0.75, 0.88, and 0.93, which are well above the recommended threshold for model accuracy [37]. To be certain that our findings could not be attributed to features of the model selection process, we also examined the criminal trajectories associated with the clusters identified in each of the other estimated models. The results were consistent with the core findings highlighted in this article.

Latent Classes

Table 3 reports the clusters representing the four groups of adolescents with the percentage of the respondents assigned to each cluster who reported experiencing the variable of interest. Because of their substantive importance in the literature on persistent offending, we include the results for violent convictions and teenage pregnancy in the following descriptions of the clusters despite their insignificance in our models.

Cluster 1 is the largest (42.3 % of the sample had the highest probability of belonging to this cluster) and contains the “least troubled” respondents. Compared with the other clusters, these least troubled respondents had high IQs (only 10.7 % had low IQs). Childhood and violent offending were virtually non-existent. This cluster has the lowest percentage of respondents with aggressive attitudes (44.7 %) or high impulsivity (32.1 %). They were the least likely of the groups to be responsible for a teenage pregnancy (2.5 %) or to leave school without academic credentials (15.7 %). About 13.8 % of them reported having used drugs habitually and having a poor relationship with their parents. While over a fifth reported having delinquent friends, this rate was the lowest of all the clusters.

Cluster 2 represents 24.5 % of the respondents. This cluster consists of the highest proportion of respondents with low IQs (59.8 %). Over 6 % had been convicted of crimes in childhood. The majority of them expressed aggressive attitudes (82.6 %) and high impulsivity (71.7 %). All of the members of this cluster left school early, making them “low achievers.” None were habitual drug users. Almost 20 % had poor parental bonds, and over half of them reported having very delinquent friends (57.6 %).

Seventeen percent of respondents are best represented by cluster 3, and we refer to them as “impulsive rowdies.” Just 9.4 % of respondents in this cluster have low IQs. The cluster is characterized by low rates of childhood (0 %) and violent offending (3.1 %), but highest percentage of aggressive attitudes (96.9 %) and impulsivity (100 %). The impulsive rowdies fall in the middle in terms of members’ experiences with life-course snares including early pregnancy, early school leaving, and habitual drug use. Members were the least likely (0 %) of the clusters to have poor parental bonds, yet the most likely (93.8 %) to have very delinquent friends.

Finally, we refer to the 16.2 % of respondents who make up cluster 4 as “ensnared partiers.” Roughly 44.3 % of the members of this cluster had low IQs. They were the most likely (16.4 %) to have been convicted as children and convicted of a violent crime by 18 years old (23.0 %). Many (65.6 %) had aggressive attitudes and high impulsivity (59.0 %). Fewer had low sociability (21.3 %). They were more likely than the members of other clusters to have experienced life-course snares including early pregnancy (13.1 %) and habitual drug use (100 %), and 82.0 % had left school early. They were also the most likely to have poor parental bonds (62.3 %), and the majority of them (68.9 %) had a large number of delinquent friends.

Second Stage Analysis: Cluster Validation

Having identified four clusters of individuals who are similar in regard to their behavioral, social, and psychological profiles, we then assess the extent to which these groups are differentiated on the basis of life-course offending trajectories up to age 50. Based on the criteria measured in mid to late adolescence, we expected that the risk for persistent offending would be greatest for the ensnared partiers. We suspect that their early criminal histories and violent offending combined with their life-course snares, poor relationships with parents, and large number of delinquent friends would be alarming to most practitioners.

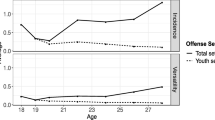

Figure 1 displays the criminal trajectories associated with each of the four clusters. The figure confirms that the ensnared partiers are the most active offenders. At age 19, the risk of offending is highest for this cluster. Notably, while this group experiences a rapid decline in offending through their twenties, they consistently have a higher risk of offending over the life course up to age 50. ANOVA results comparing cluster differences at each age suggest that these differences are more consistently significant in early adulthood than they are in later adulthood.

The impulsive rowdies appear to be the cluster best characterized as aggressive and impulsive, yet they also appear to be very social. They were the most likely to self-report a large number of delinquent friends, while retaining strong bonds with parents. Figure 1 suggests that they, too, were very active offenders in late adolescence, nearly matching the rate of offending by the ensnared partiers; however, their offending trajectory dropped off more quickly as they entered adulthood. The offending trajectory of the low achievers is similar in shape to that displayed by the impulsive rowdies. Though criminally active in young adulthood, their rate of offending declines sharply in their twenties. By age 50, the risk of offending for both the impulsive rowdy cluster and the ensnared partiers is nearing zero.

We anticipated that the least troubled cluster would represent the least active offenders because a low proportion of these members experienced the various risk indicators. Indeed of the four clusters, this cluster is the least criminally active with a rate of offending near zero throughout their life course.

Taken together, these results suggest two key findings. First, the risk indicators included here appear to be strong indictors of offending. Those clusters with a larger proportion of their members experiencing negative or precocious events and personality traits are more likely to offend in adolescence and into adulthood. The results demonstrate that the risk indicators are helpful in isolating a group of boys whose relative participation in crime is significantly higher at every age in the analysis compared to the other three clusters. Second, despite clear differences in the magnitude of offending across clusters, we note the absence of a persistently high rate of offending for any of the groups. Even among the ensnared partiers, whose rate of offending is significantly greater than their peers through age 50, offending rates begin to decline steadily and rapidly as they enter young adulthood. Using a variety of theoretically informed behavioral, social, and psychological indicators, we are unable to diagnose a group of individuals characterized by a consistently high rate of offending across the life course.

Sensitivity Analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to ensure that our findings were not simply the result of measurement choices. We restricted the assignment of risk to those boys who were in the tails of the risk distribution by setting the assignment of risk to those in the upper (or lower) decile for the continuous indicators. As in the analysis just presented, the sensitivity analysis yielded four clusters which best characterized the data (results not shown). Among them was a small cluster of respondents, representing just 6.1 % of the sample. Members of this cluster experienced nearly every behavioral, social, and psychological risk indicator at a significantly higher percentage than members of the other three clusters experienced them.

Analogous to the ensnared partiers in our central analysis, this most problematic group was the most criminally active of the clusters throughout adulthood and particularly in early adulthood. Consistent with the criminal trajectories presented in Fig. 1, there were clear differences in the magnitude of offending across all clusters, but the overall shape of the trajectories were similar to one another. All of the clusters experienced precipitous declines in offending in early adulthood. Moreover, the ANOVA models comparing the clusters’ conviction counts at each age were not statistically significant at many of the ages in later adulthood.

Discussion

Following applications of latent class cluster analysis in the health sciences literature, this paper set up a diagnostic framework to learn whether factors found to be associated with persistent offending in variable-centered, retrospective analyses could be used in a diagnostic or prospective framework. Our analytic approach offers a methodological twist on group-based modeling strategies that have become increasingly pervasive in criminology. First, our strategy takes a person-centered approach and sets up a scenario more comparable to clinical settings whereby adolescent factors are known, but childhood factors are often lacking. Second, our approach contrasts latent trajectory approaches which identify offender groups retrospectively.

Our person-centered approach highlights how behavioral, personality, and social problems cluster together in patterned ways. Previous analysis has illuminated variables that predict prolonged offending and has stressed that the accumulation of these problems or disadvantages undermine healthy adult development in ways that are difficult to overcome [52, 29]. Though not inconsistent with these studies, our findings highlight that not all risk factors are equally likely to occur within individuals. Our ensnared partiers, for instance, were more likely than members of the other clusters to have offended as children and offended violently. They were also the most likely to experience early fatherhood, take part in habitual drug use, and have poor parental bonds. Although they went on to offend at relatively high rates in adulthood, in adolescence they did not stand out on other well-known risk factors for offending including having an aggressive attitude, high impulsivity, or low sociability. This points to a need to appreciate, not simply the quantitatively, but also the qualitatively distinct ways in which risk factors cluster together and accumulate.

At the same time, our results are unable to validate a distinct subgroup of persistent offenders whose absolute levels of offending are consistently high across the life course. Overall, the shape of the age-crime relationship is consistent across clusters; there is a discernible increase in offending throughout early adolescence and a peak of offending in late adolescence (ranging from 18–21). Consistent with the classic age-crime curve, each of the clusters of adolescents experienced precipitous declines in offending throughout the remainder of the life course, so that offending was exceedingly rare at age 50. These findings are consistent with a softer interpretation of “persistence” allowing that offending may decline with age yet, for some, may remain high relative to other offenders [33, 53].

While our evidence runs counter to notions of a troubled group of individuals who offend at consistently high rates over time, we also note that our measure of crime (criminal convictions at each age) is a limited measure and captures only one feature of a persistent antisocial tendency. Although a focus on conviction history should capture those deemed most problematic from a public security perspective, it may be that the offensive behavior of persistent offenders changes form with age in ways that become undetectable by law enforcement. Likewise, it may be that persistence is more easily observed in minor forms of offending or types of offending which are less likely to receive official attention.

Our findings may inform practitioners or those individuals interested in intervening in the lives of those most at risk for future offending. Whereas previous research using measures of risk attained during adolescence has demonstrated limited success distinguishing persisters, our application of latent class cluster analysis to identify clusters of similarly situated youth on the basis of a variety of behavioral, social, and psychological risk factors is more closely aligned with the conceptualization of risk as a constellation or accumulation of problem characteristics and behaviors.

Conclusion

Criminologists have long been interested in the clustering of deviant and criminal behavior in adolescence. As a consequence of this clustering, adolescence is often the first point in life course in which troubled youth come to the attention of the criminal justice system, mental health professionals, or other service providers. The vast majority of adolescents age out of these problem behaviors as they transition to adulthood. However, for a smaller number of individuals, adolescent problems are part and parcel of a long life of continued behavioral and personality problems. Researchers have long sought to understand whether the comorbidity of disorders and risks is due to an accumulation of disadvantages in which early problems cause later problems to occur or whether this variety of problems can be attributed to early, fundamental differences between people. This area of inquiry has maintained its salience because of its potential impact on health care and criminal justice policies. If in fact the population is comprised of offender types with distinct etiologies of offending, this would necessitate distinct treatments.

The findings from our research inform this debate. On the one hand, our analyses reveal that the clustering of behavioral, social, and psychological problems in adolescence do diagnose or predict a small subset of individuals with relatively high involvement in crime across their life course. On the other hand, we also observe a pattern mirroring the typical age-crime curve whereby offending declines rapidly in young adulthood even among the most at-risk group. Later-life differences in offending between the clusters were also less likely to be statistically significant than differences in early adulthood. These findings suggest that policies aimed to identify offenders who will continue to offend at a consistently high rate across the life course based on adolescent characteristics would be largely unsuccessful. One goal of such efforts is to incapacitate individuals so that they are no longer free to commit crimes. Yet, our results suggest that continued offending at a consistently high rate is rare, even among the most criminally active subset. Moreover, the similarity in offending patterns across all clusters undermines distinct offender group explanations that are grounded in the idea that subgroups of offenders experience qualitatively distinct offending trajectories. These patterns instead suggest that the explanations of the age-crime relationship, and specifically the processes behind criminal decline over the life course, are generalizable to all offenders.

To the extent that these findings replicate in other work using different data and measures, this strategy may prove to be a useful real-world application for those working with troubled youth. The most troubled adolescents appear to experience setbacks across several domains. They experienced cognitive deficiencies, personality problems, and a number of life-course snares. Regardless of their initial cause, these setbacks may accumulate over the life course and disadvantage these individuals across life domains. This highlights the need to research and develop multidimensional interventions that treat adolescents holistically.

Notes

To help ensure our findings are not a result of measurement choices, we also conduct a sensitivity analysis in which we restrict the assignment of risk to those boys who are in the upper decile (or lower decile in the case of low sociability) of the distribution for each of the continuous indicators. The substantive findings using this decision making criterion do not differ from those presented in the main analyses. Details available upon request.

Because our outcome of interest is the count of criminal convictions at each age, we use a non-linear Poisson model with the inclusion of an overdispersion parameter (analogous to a negative binomial model). The full mixed model equation is

$$ {\eta}_{ti}={\beta}_{00}+{\beta}_{10}*Ag{e}_{ti}+{\beta}_{20}* AgeSquare{d}_{ti}+{\beta}_{30}* AgeCube{d}_{ti}+{r}_{0i}+{\epsilon}_{ti} $$The insignificance of violent offending was not related to its correlation with child offending. Similar results were obtained when the child offending indicator was excluded from the models.

References

Andrews, R. L., & Currim, I. S. (2003). A comparison of segment retention criteria for finite mixture logit models. Journal of Marketing Research, 40, 235–243.

Bauer, D. J., & Shanahan, M. J. (2007). Modeling complex interactions: person-centered and variable-centered approaches. Modeling contextual effects in longitudinal studies, (pp. 255-283).

Bersani, B. E., Nieuwbeerta, P., Laub, J. H. (2009). Predicting trajectories of offending over the life course: findings from a Dutch conviction cohort. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency.

Bosick, S. J. (2012). Crime and the transition to adulthood: a person-centered approach. Crime & Delinquency.

Brame, R., Nagin, D. S., & Wasserman, L. (2006). Exploring some analytical characteristics of finite mixture models. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 22(1), 31–59.

Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (1993). When do individual differences matter? A paradoxical theory of personality coherence. Psychological Inquiry, 4(4), 247–271.

Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (1995). The continuity of maladaptive behavior: from description to explanation in the study of antisocial behavior. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology (risk, disorder, and adaption) (Vol. 2, pp. 472–511). Oxford: Wiley.

Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Silva, P. A., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., Krueger, R. F., & Schmutte, P. S. (1994). Are some people crime prone? Replications of the personality-crime relationship across countries, genders, races, and methods. Criminology, 32, 163–195.

Clausen, J. A. (1991). Adolescent competence and the life course, or why one social psychologist needed a concept of personality. Social Psychology Quarterly, 54(1), 4–14.

Cohen, J. (1983). Incapacitation as a strategy for crime control: possibilities and pitfalls. In M. Tonry & N. Morris (Eds.), Crime and justice: a review of research (Vol. 5, pp. 1–84). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

D'Unger, A. V., Land, K. C., McCall, P. L., & Nagin, D. S. (1998). How many latent classes of delinquent/criminal careers? Results from mixed Poisson regression analyses. The American Journal of Sociology, 103(6), 1593–1630.

Eysenck, S. B., & Eysenck, H. J. (1964). An improved short questionnaire for the measurement of extraversion and neuroticism. Life Sciences, 3(10), 1103–1109.

Farrington, D. P., & West, D. J. (1993). Criminal, penal and life histories of chronic offenders: risk and protective factors and early identification. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 3(4), 492–523.

Farrington, D. P., Loeber, R., Elliott, D. S., Hawkins, D. J., Kandel, D. B., Klein, M. W., et al. (1990). Advancing knowledge about the onset of delinquency and crime. In B. B. Lahey & A. E. Kazdin (Eds.), Advances in clinical child psychology (Vol. 13, pp. 231–342). New York: Plenum Press.

Farrington, D. P., Coid, J. W., Harnett, L. M., Jolliffe, D., Soteriou, N., Turner, R. E., et al. (2006). Criminal careers up to age 50 and life success up to age 48: new findings from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development (2ed.): Home Office Research, Development and Statistics Directorate.

Farrington, D. P., Ttofi, M. M., & Coid, J. W. (2009). Development of adolescence‐limited, late‐onset, and persistent offenders from age 8 to age 48. Aggressive Behavior, 35(2), 150–163.

Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., & Lynskey, M. T. (1994). The comorbidities of adolescent problem behaviors: a latent class model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 22(3), 339–354.

Formann, A. K., & Kohlmann, T. (1996). Latent class analysis in medical research. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 5(2), 179–211.

Gottfredson, D. M. (1987). Prediction and classification in criminal justice decision making. In D. M. Gottfredson & M. Tonry (Eds.), Prediction and classification: criminal justice decision making (pp. 1–20). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Haapasalo, J., & Tremblay, R. E. (1994). Physically aggressive boys from ages 6 to 12: family background, parenting behavior, and prediction of delinquency. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 1044–1052.

Hagenaars, J. A., & McCutcheon, A. L. (2002). Applied latent class analysis. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Jennings, W. G., & Reingle, J. M. (2012). On the number and shape of developmental/life-course violence, aggression, and delinquency trajectories: a state-of-the-art review. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(6), 472–489.

Kerckhoff, A. C. (1990). Getting started: transition to adulthood in Great Britain. Boulder: Westview Press.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lauritsen, J. L. (1998). The age-crime debate: assessing the limits of longitudinal self-report data. Social Forces, 77(1), 127–154.

LeBlanc, M., & Loeber, R. (1998). Developmental criminology updated. Crime and Justice, 23, 115–198.

Lin, T. H., & Dayton, C. M. (1997). Model selection information criteria for non-nested latent class models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statististics, 22, 249–264.

Lopes, G., Krohn, M. D., Lizotte, A. J., Schmidt, N. M., Vásquez, B. E., & Bernburg, J. G. (2012). Labeling and cumulative disadvantage the impact of formal police intervention on life chances and crime during emerging adulthood. Crime and Delinquency, 58(3), 456–488.

Magnusson, D., & Bergman, L. R. (1990). A pattern approach to the study of pathways from childhood to adulthood. In L. N. Robins & M. Rutter (Eds.), Straight and devious pathways from childhood to adulthood (pp. 101–115). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescent-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

Moffitt, T. E. (2003). Life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial behavior: a 10-year research review and a research agenda. In B. B. Lahey, T. E. Moffitt, & A. Caspi (Eds.), Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency (pp. 49–75). New York: Guilford Press.

Moffitt, T. E. (2006). Life-course persistent versus adolescence-limited antisocial behavior: research review. In D. Cicchetti & D. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology (2nd ed., vol. 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation). New York: Wiley.

Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Dickson, N., Silva, P. A., & Stanton, W. (1996). Childhood-onset versus adolescent-onset antisocial conduct problems in males: natural history from ages 3 to 18 years. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 399–424.

Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Harrington, H., & Milne, B. J. (2002). Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescent-limited antisocial pathways: follow-up at age 26 years. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 179–207.

Mun, E. Y., Windle, M., & Schainker, L. M. (2008). A model-based cluster analysis approach to adolescent problem behaviors and young adult outcomes. Development and Psychopathology, 20(1), 291.

Nagin, D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge: Harvard University.

Nagin, D. S., & Tremblay, R. E. (2005). What has been learned from group-based trajectory modeling? Examples from physical aggression and other problem behaviors. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 602(Nov.), 82–117.

Nagin, D. S., Farrington, D. P., & Moffitt, T. E. (1995). Life-course trajectories of different types of offenders. Criminology, 33(1), 111–139.

Osgood, W. (2005). Making sense of crime and the life course. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 602.

Osgood, D. W., & Rowe, D. C. (1994). Bridging criminal careers, theory, and policy through latent variable models of individual offending*. Criminology, 32(4), 517–554.

Paternoster, R., Dean, C. W., Piquero, A., Mazerolle, P., & Brame, R. (1997). Generality, continuity and change in offending. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 13(3), 231–266.

Patterson, G., & Yoerger, K. (1993). Developmental models for delinquent behavior. In S. Hodgins (Ed.), Mental disorder and crime (pp. 140–172). Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Piquero, A. R. (2008). Taking stock of developmental trajectories of criminal activity over the life course. In A. M. Liberman (Ed.), Longitudinal research on crime and delinquency: Springer.

Piquero, A. R., Daigle, L. E., Gibson, C., Piquero, N. L., & Tibbetts, S. G. (2007). Research note: are life-course-persistent offenders at risk for adverse health outcomes? Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 44(2), 185–207.

Rabiner, D. L., Coie, J. D., Miller-Johnson, S., Boykin, A.-S. M., & Lochman, J. E. (2005). Predicting the persistence of aggressive offending of African American males from adolescence into young adulthood the importance of peer relations, aggressive behavior, and ADHD symptoms. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 13(3), 131–140.

Raudenbush, S. W. (2005). How do we study "what happens next?". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 602(Nov.), 131–144.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Raven, J. (2003). Raven progressive matrices. In Handbook of nonverbal assessment (pp. 223-237). Springer.

Robins, L. N. (1978). Sturdy childhood predictors of adult antisocial behaviour: replications from longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine, 8, 611–622.

Rowe, D. C., Osgood, D. W., & Nicewander, W. (1990). A latent trait approach to unifying criminal careers*. Criminology, 28(2), 237–270.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1997). A life-course theory of cumulative disadvantage and the stability of delinquency. In T. P. Thornberry (Ed.), Developmental theories of crime and delinquency (pp. 133–162). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (2005). A life-course view of the development of crime. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 602, 12–45.

Singer, B., Ryff, C. D., Carr, D., & Magee, W. J. (1998). Linking life histories and mental health: a person-centered strategy. Sociological Methodology, 28, 1–51.

Skeem, J., Johansson, P., Andershed, H., Kerr, M., & Louden, J. E. (2007). Two subtypes of psychopathic violent offenders that parallel primary and secondary variants. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(2), 395.

Stouthamer-Loeber, M., Wei, E., & Loeber, R. (2004). Desistance from persistent serious delinquency in the transition to adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 897–918.

Thornberry, T. P., & Krohn, M. D. (2003). The development of panel studies of delinquency. In T. P. Thornberry & M. D. Krohn (Eds.), Taking stock of delinquency: an overview of findings from contemporary longitudinal studies. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Thornberry, T. P., Lizotte, A. J., Krohn, M. D., Farnworth, M., & Jang, S. J. (1994). Delinquent peers, beliefs, and delinquent behavior: a longitudinal test of interactional theory*. Criminology, 32(1), 47–83.

Tracy, P. E., Wolfgang, M. E., & Figlio, R. M. (1990). Delinquency in two birth cohorts. New York: Plenum.

Vermunt, J. K., Van Ginkel, J. R., Van Der Ark, L. A., & Sijtsma, K. (2008). Multiple imputation of incomplete categorical data using latent class analysis. Sociological Methodology, 38(1), 369–397.

West, D. J., & Farrington, D. P. (1977). The delinquent way of life. London: Heinemann.

White, H. R., Bates, M. E., & Buyske, S. (2001). Adolescence-limited versus persistent delinquency: extending Moffitt's hypothesis into adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(4), 600.

Wiesner, M., & Capaldi, D. M. (2003). Relations of childhood and adolescent factors to offending trajectories of young men. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 40(3), 231–262.

Wolfgang, M., Figlio, R., & Sellin, T. (1972). Delinquency in a birth cohort. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Young, M. A. (1982). Evaluating diagnostic criteria: a latent class paradigm. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17(3), 285–296.

Acknowledgments

No additional funding was provided for this research, and funding was therefore not influential in the conduct and preparation of this research, in the collection and interpretation of data, in the writing process, and in the decision to submit this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 102 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bosick, S.J., Bersani, B.E. & Farrington, D.P. Relating Clusters of Adolescent Problems to Adult Criminal Trajectories: a Person-Centered, Prospective Approach. J Dev Life Course Criminology 1, 169–188 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-015-0009-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-015-0009-y