Abstract

We discuss various anti-poverty policies which involve direct transfer policies for the poor, focusing on their different dimensions—namely the size and time sequence of the transfers, whether it is cash or in kind, any conditionality involved, whether they are means-tested. We argue that their pros and cons depend on what is the underlying aspect of poverty that the policy is aiming to address, namely what is the cause of it, what is the time horizon, what is the social objective, and what, if any, limitations on state capacity might be present. We illustrate the issues involved by discussing two transfer policies in detail, a rural asset transfer programme in Bangladesh and a hypothetical universal income support programme in India—and highlight the dual nature of such policies as both redistributive and potentially productive investments. We conclude by discussing the potential complementarities between different types of anti-poverty policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Various anti-poverty policies can be divided into three broad categories: those that are aimed at enabling the poor greater access to markets, those that are aimed at improving the access of the poor to public services and infrastructure, and those that are explicitly redistributive in nature. Examples of the first include reducing transactions costs in specific markets (e.g. savings, credit, insurance), providing inputs which are not readily available in the market (e.g. training specific skills), improving access to information, and reforming property rights. Examples of the second include various measures to improve accountability and reduce leakage and corruption in the provision of public services like health and education. Examples of the third class of policies involve directly transferring resources to the poor, in cash or in kind, which have been increasingly adopted by developing countries as part of their anti-poverty and social safety net policies.Footnote 1

In this essay I focus mainly on transfer policies aimed at the poor. These are aimed to help individuals and households cope with chronic poverty, destitution, and vulnerability, and examples include unconditional and conditional cash transfers, non-contributory social pensions, food and in-kind transfers, school feeding programmes, public works, and fee waivers (World Bank 2018). These are typically given in regular instalments to individuals or households in a targeted group, both by governments and by NGOs funded by general taxation or by donors, typically based on means-testing (which differentiate them from pensions or child support). More recently, there has been a trend towards a new class of transfer policies aimed at the poor, programmes that involve one-time lumpy transfers of money or productive assets, such as livestock paid to individuals or households to enable them to start or expand self-employment activities or microenterprises.

Today, more than 120 low- and middle-income countries run cash transfer programmes targeted to poor families (Banerjee et al 2023), and globally, these countries spend an average of 1.5% of GDP on social safety net programmes (World Bank 2018). In just the past decade, the number of developing countries running conditional cash transfer programmes, which condition benefits on households making human capital investments in their children, has more than doubled (World Bank 2018).

Transfers can vary in size—ranging from income or consumption support to enable the poor to accumulate assets (e.g. asset transfer policies). They can be unconditional or conditional on children attending school and family members receiving preventative health care (e.g. programmes such as Progresa, renamed Opportunidades and more recently, Prospera, in Mexico, and Bolsa Familia in Brazil) or in kind (e.g. food, sanitation, education, health services provided free or at a subsidised rate to the poor). We will refer to the these as UCTs, CCTs, and IKTs, respectively.

These transfer programmes are part of an embryonic form of the emergence of a welfare state in developing countries, something that had firmly gathered roots in the developed world by the 1960s, following the Great Depression and the Second World War (see Garland 2016 for an overview). Its origin in the developing world follows the failure of the structural adjustment policies across Latin America in the 1980s, when many of the region’s governments adopted conditional cash transfer programmes (CCTs) to mitigate their detrimental consequences on social protection and people’s livelihoods (Fotta and Schmidt 2022).

There is still a fair bit of debate about the form these direct transfer programmes should take. For example, should these be in cash or in kind or take the form of subsidies? If these are to take the form of cash transfers, should these be conditional or unconditional? Should these be means-tested or universal?

If we think a bit abstractly, all economic decision problems require at a minimum an assessment of the economic environment, an objective, a set of constraints, and a time horizon. Therefore, designing anti-poverty policies is no different. It requires a view of what causes of poverty, what are the constraints facing the poor as well as the policymaker (e.g. budget constraint, administrative capacity constraint), what is the social objective, and to what extent it differs from the objective of the beneficiaries, and what is the time horizon. Let me elaborate on these dimensions a bit.

An important element that is implicit in the concept of existing transfer policies, such as cash or in-kind transfers, employment guarantees, subsidies, public works programmes like MGNREGS, and livelihood programmes that provide support in starting or improving their livelihood activities, are different views as to what causes poverty. One aspect of this involves differences in views about the binding constraints facing the poor: for e.g. is it access to or frictions affecting specific markets (food, credit, labour, insurance), access to public services (health, sanitation, education), or life-cycle considerations applying to subsets of the poor (maternity, child welfare, old-age support), social discrimination (gender, caste), or just the absence of sufficient income. The other aspect is, whether poverty is a transient or persistent state. Extreme poverty tends to persist in some circumstances while people can gradually lift themselves into better lives in others. If poverty is transient, then maximising income generation opportunities and providing a safety net seems reasonable policies, but if poverty is persistent then enabling the poor access to income generation opportunities would be the only way to make headway in terms of reducing persistent poverty.

A second implicit element is the time horizon and goal of the policymaker—whether the goal is long-term upliftment of the poor by generating or enhancing income-earning opportunities, or to provide short-term relief or to help people cope with shocks (e.g. health, employment).

A third implicit element is the underlying social objective. Is it equity? In which case given the limited resources available it would make sense to spread it evenly and in particular, provide more support to those who are the neediest. Or is it the most effective deployment of resources to get as many people permanently out of poverty as possible? One can immediately see that these two objectives have very different implications regarding the size of the transfers and how they are allocated.

Finally, different transfer policies also partly reflect different views on the limitations of state capacity regarding welfare. This is not just limited budgetary resources but also bureaucratic delays, inclusion and exclusion errors, and corruption. For example, cash transfers may be viewed by some as the state shirking its responsibility to provide different types of welfare services, but it may also reflect a pragmatic take that given the many problems of delivery, this may have the least leakage in terms of reaching the poor.

In this paper, I will discuss two kinds of transfer policies I have studied recently to illustrate a few conceptual points relating to the pros and cons of different types of transfer policies. The two specific policies I want to discuss are as follows. The first one (discussed in “Asset transfer policies” section below) is an asset transfer policy in rural Bangladesh targeted to ultra-poor women combined with some training carried out by BRAC. The second one (discussed in “A universal income transfer scheme” section below) is a hypothetical minimum universal income support programme in the context of India.

In "Complementarities between different types of transfer schemes" section, I make some general conceptual points relating to transfer policies aimed at the poor, in the light of the discussion of the earlier discussion about specific forms of transfer policies. I argue that while transfer policies for the poor are redistributive in nature, some of them can actually be viewed as an investment in productivity and not merely “relief”. Also, another important point in my view is, while at one level, different kinds of anti-poverty policies (or, more narrowly transfer policies) and programmes compete for fixed resources (including state capacity) and therefore, are substitutes, still there are some interesting ways in which complementarities between these different policies can be and are being explored. The section “Concluding remarks” makes some concluding remarks.

Asset transfer policies

Among the various explanations for chronic, extreme poverty, a prominent theme is the idea of a poverty trap.Footnote 2 Theories of poverty traps emphasise the self-perpetuating nature of poverty, whereby the chief cause of poverty is previous poverty. Several mechanisms could potentially underlie such a ‘cycle of poverty’ at the individual level, ranging from savings behaviour, human capital, nutrition, physical and mental health, and lumpy investments coupled with borrowing constraints.Footnote 3

The two main insights of this view of poverty are, first, that the same person would not be poor had they started with better initial opportunities, and second, there is a certain minimum threshold level of resources that are needed so that people can make a large enough investment (in their health, education, productive assets) to get out of poverty.

The ‘poverty traps view’ contrasts with alternative accounts of persistent poverty which emphasise the role of economic fundamentals—the innate characteristics of the individual or the economic environment in which the poor operate. To the extent that these characteristics cannot be changed or compensated, the afflicted person is doomed to remain poor.

The two broad views characterised above have starkly different implications for the design of anti-poverty policies. If the poorest are indeed in a trap, one-time investments can have permanent effects, provided that the investment is large enough. Small transfers would not suffice to overcome the particular barrier locking someone in poverty. On the other hand, if the poor are unalterably unproductive—because of their individual characteristics or the economic environment in which they operate—one-time transfers will dissipate over time. The optimal social policy in this case is regular income or consumption support.

In a recent paper, me and my co-authors study an asset transfer policy in rural Bangladesh to see if poverty traps are present. This is an example of a “targeting the ultra-poor” (TUP) programme that offers a combination of one-time large asset transfers, training, and personalised healthcare support to specifically targeted households, namely women in rural areas. An earlier study (Bandiera et al. 2017) showed that despite these programmes having on average a high and positive effect on reducing poverty among beneficiaries, a fraction of these beneficiaries—around 30%—falls back into extreme poverty.

The study is set in 1309 villages of northern Bangladesh, an area characterised by high rates of extreme poverty, food insecurity, and severely limited occupational choice. The data follows 6000 beneficiaries of BRACs TUP programme over five survey waves between 2007 and 2018. Roll-out of the programme was randomised such that half the beneficiaries received it in 2007 and the rest in 2011. For 2007–2014 data were collected on a total of 23,000 households that are representative of the entire village population.

At baseline, we document high persistence of poverty in the control group and a hierarchy of occupations that strongly correlates with household wealth. The poorest work in low-pay, irregular, casual jobs in agriculture or domestic services, while the better-off are self-employed in livestock rearing and cultivating their own land. In this context, the question of persistent poverty becomes a question of whether the poor stay poor because they do bad jobs (and are unable to take on different ones) or whether they do bad jobs because they are poor (poverty traps view).

We use the asset transfer that was part of the TUP programme to test between these competing views. The transfer was of similar size for all beneficiaries—the majority received a cow—but households held different amounts of assets pre-transfer. This generates variation in asset values post-transfer which we exploit to track subsequent asset dynamics. As our main result, we identify a threshold value of productive assets above which households accumulate further wealth and below which they fall back into poverty. Those households that own less than an equivalent of 500 USD PPP of productive assets in 2007—34% of beneficiaries—have even less four years later.

Our survey reveals that wealthier households not only hold more assets, but more expensive assets (cows and land). These expensive assets constitute an indivisible investment, which the poorest cannot afford. For example, the median price of a cow amounts to the 80% of average annual per-capita consumption of the poor.Footnote 4

In addition to the cow, some complementary assets seem to be indispensable to reach a minimum profitable scale of the livestock microenterprise. The households that remain below the poverty threshold do not do so by much. The amount of assets they lack equals the price of a cart, a shed for keeping livestock, or a plough. Without these additional inputs, the cow does not produce sufficient earnings to be maintained and assets will deplete over time. On the other hand, beneficiaries with sufficient wealth at baseline to afford these complementary inputs achieve much higher returns in self-employed livestock rearing than in casual labour, which they can then reinvest. Overall, a picture emerges where the poorest lack livestock and complementary assets, both of which are necessary to take on more profitable occupations but neither of which they can acquire. They are thus excluded from the better occupations and their labour and aptitude is wasted on less productive and insecure casual labour. The low wage and unreliable nature of this work, in turn, prevent them from saving enough to purchase the indivisible assets needed to move out of it.

Many findings of this paper will be specific to the context. For example, we are less likely to find poverty traps in cities where people face a larger menu of job options with fewer burdens to move up from the worst to the next best occupation. However, even in other settings there might be lumpy investments—the cost of moving to a better neighbourhood, a certified training programme, or a college degree—which exclude the poor from better occupations.

This study therefore poses a trade-off: lumpy transfers can be effective in pushing the poor out of poverty in the long run but in the presence of limited resources, they cannot be adopted on a very large scale. On the other hand, relatively small amounts of transfers can provide income support to a larger group of people and provide a valuable safety net to vulnerable groups.

Unless recipients can move above the wealth threshold, any social assistance will dissipate over time, and they will slide back into poverty. This might explain the modest effects of small loans on household productivity in some settings. Nevertheless, there remains an important role for small transfers to safeguard slightly better-off households who risk falling into the trap in the face of adverse shocks. However, to serve this purpose they have to be given on a regular basis.

On the other hand, large asset or human capital transfers, as well as policies that address the multiple constraints that jointly create a trap can have lasting effects even if only delivered once because they enable people to move into better occupations. After people escape the most basic level of poverty (it takes at least 4 years in our context), they might even be able to repay some of the initial asset grants. Estimates suggest that the surplus generated from breaking the trap surpasses the programme cost by a factor of 15.

However, given the resource constraints, the fact that lumpy transfers are more likely to enable the poor escape poverty poses an obvious trade-off, as mentioned earlier. To the extent that providing a minimum level of income or consumption support is desirable to as many of the poor as possible in order to help them meet a subsistence level, that would take away revenue that could be given to smaller number of the poor at a larger sum per person, to help these individuals escape poverty. As an illustration, consider the asset transfer programme we discussed above. A typical cow costs around 9000 BDT in 2007 which converts to Rs7651 in INR in 2007. Adjusting for inflation, it is Rs 21,886.55 in 2022. In contrast, the PM-Kisan scheme, involves a payment of Rs 6000 per year, which is less than one-third of this amount. Given the Indian budgetary realities (which we will discuss in more detail in the next section), it is not practical for the government, whether at the state or central level, to adopt a lumpy transfer scheme on a very large scale. Moreover, given the nature of the political process, it is not practical for governments (as opposed to NGOs like BRAC) to give a substantial transfer to a small group of people without generating discontent in the larger population. This brings me to the discussion of another type of transfer scheme that I have studied recently, which goes in the very opposite direction compared to lumpy asset transfer schemes—a limited and fiscally feasible version of a universal transfer scheme.

A universal income transfer scheme

There has been a global surge in academic and policy interest in using UBI.Footnote 5 In the Indian context, several scholars and policy commentators have argued over the past decade that inefficient and poorly implemented welfare schemes should be replaced with direct income transfers to the poor. The 2016–2017 Economic Survey of India gave further policy salience to the idea of a UBI for India, by recommending its active consideration. Parallel investments in the JAM (Jan-Dhan, Aadhaar, Mobile) infrastructure required to implement direct benefit transfers into beneficiary bank accounts, have also made it feasible to implement the idea.

The move to income transfers as a component of India’s anti-poverty strategy has also been reflected in actual policy in the last few years, especially in the context of farmer welfare. The state of Telangana’s early 2018 launch of the Rythu Bandhu Scheme (RBS), which gave farmers an unconditional payment of Rs. 4,000 per acre, pioneered this approach. Since then, such policies have been replicated at both the state-level (as in the KALIA programme in Odisha) and at the national level (through the PM-KISAN programme). The Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojana (PM-KISAN) was launched in December 2018. At first, it provided Rs. 6000/year per family with cultivable landholding up to 2 hectares, subject to some exclusions. The first Cabinet meeting of the NDA government after re-election in 2019 extended the scheme to all farmers, regardless of landholdings. It excludes those who are not farmers, or pay income tax, and also, both husband and wife cannot take benefits.

With the extended coverage, it reaches around 10 crore farming households (the aim is to reach 14.5 crore farming households or roughly half the country) with an estimated cost to the Central Government of Rs. 75,000 crores for the year 2020–2021, or roughly 0.4% of GDP at current prices. For the latest year. 2022–2023, the estimated cost to the Central Government is Rs. 68,000 crores, or roughly 0.3% of GDP at current prices. Despite its scale (it is likely to be the largest income transfer scheme in the world) and some success, problems of inclusion and exclusion errors continue to come up. Some of the exclusion errors or delays are due to logistical factors affecting the last-mile delivery—mainly because of rejections by the respective bank or Aadhaar verification issues.

We propose that these income transfers be made universal, covering all citizens regardless of whether they are farmers.

Theory and evidence point to several advantages of unconditional universal income transfers as an anti-poverty policy. Such transfer schemes have several attractive properties: limited administrative costs of targeting, and lower risk of exclusion errors (since they are universal); lower leakage of benefits because of fewer intermediaries between fund disbursal and receipt; lower disincentives for work compared to most targeted programmes; greater sociological acceptability because of the lack of ‘rank reversal’ in incomes that often happens under targeted programmes; improved financial inclusion and formal savings, which can in turn mitigate risk and enable consumption smoothing at a lower cost than credit (which is subject to higher costs of financial intermediation); relaxing borrowing constraints for productive investments; and improved female empowerment (especially if transfers to children are sent to their mothers’ accounts).

One reason that a policy of universal transfers has moved more slowly despite the endorsement by the Economic Survey is that in policy discussions universal income transfers have been equated with Universal Basic Income (UBI). This has several problems.

First, a natural response to such a proposal is, what is the point of giving the rich a basic income too? Elsewhere I have argued (see Ghatak and Maniquet 2019) that this is largely a misunderstanding of how tax and transfer schemes work. In any developed country, people pay taxes and also receive some concessions or government support at the same time depending on their situation (say, child support) and what really matters is their net income. Similarly, a rich person will be paying taxes that are much higher than the UBI they will receive, and indeed, for the rich whether they receive a UBI or there is a big threshold below which no income taxes are to be paid (which has recently been raised to Rs. 3 lakh per year) are equivalent policies in terms of net income.

Second, the term “basic income” connotes an amount sufficient for survival, and most academic and policy discussions of a UBI have focused on transfers large enough to nearly eliminate poverty, ranging from 3.5 to 4% of GDP (Joshi 2016, Economic Survey 2016) to 10–11% of GDP (Bardhan 2016; Ghatak 2015). As a result, the fiscal math simply does not work out. It is impossible to implement such a large universal transfer without either cutting other major anti-poverty programmes or substantially increasing the tax to GDP ratio (currently around 18%). Alternatively, a large transfer automatically necessitates some targeting, which negates several key advantages of universality. This question of feasibility is a relevant and important question in the context of any transfer schemes, including universal ones.

In my paper with Karthik Muralidharan (Ghatak and Muralidharan 2021), we argue that there is a limited version of a universal income transfer scheme that is feasible. Suppose India adopts a limited form of a universal income transfer scheme for every citizen that is pegged at 1% of GDP per capita to be deposited directly into the bank account of every citizen on a regular monthly basis. This would provide every citizen with a supplemental benefit of around Rs. 144 per month or Rs. 1728 per year (at current estimates).

The biggest advantage of this proposed scheme is simply that it is affordable enough to actually be implemented. Indeed, the value envisaged by the proposed scheme is quite similar to that of PM-KISAN (which works out to Rs. 500/month per household or Rs. 120/month per person) and so it can be implemented simply by roughly doubling the budget for PM-KISAN and making the programme truly universal. This would allow benefits to also reach landless labourers, who are typically more likely to be destitute and needy than farmers who own land. It would also reduce the likelihood that farmers continue to engage in economically unviable cultivation just to get the PM-KISAN benefit.

It would also be easier to implement by further reducing eligibility and verification costs. Also, by being at the individual level it would limit the potential for gaming the scheme (by households splitting to double the value of the transfer). However, even with a universal scheme one has to be realistic in terms of some of the logistical problems of last-mile delivery faced by various direct benefit transfer (DBT) schemes. These include availability of and accessibility to cash-out points (COPs). Beneficiaries often have to travel long distances to withdraw cash and even when available a COP may function erratically. They also include issues that emerge during the cash-out transaction itself, such as network failures, biometric authentication failures, electronic payment device malfunctioning, and long queues.Footnote 6

Complementarities between different types of transfer schemes

One of the main takeaway points from the discussion so far is at least some forms of transfer policies should not be viewed only as subsistence support for the poor. Rather they can also have positive productivity effects, which means the clean separation between policies that are aimed at boosting productivity and those that are viewed as redistributive (or to provide basic relief)—an “equity-efficiency” trade-off—does not often hold.

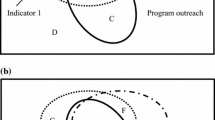

The other main takeaway points are the different kinds of trade-offs that exist among alternative transfer schemes. For example, lumpy schemes are more likely to achieve permanent gains in pushing people out of poverty but they are expensive and certainly cannot be adopted at a very large scale. On the other hand, smaller transfer schemes can provide income support to the poor and play an important role in providing a safety net, but they are unlikely to help the poor escape poverty. Moreover, given limited budgetary resources, the better is the targeting infrastructure that can identity the poor, the higher can be the transfer amount that can be given out compared to a universal scheme. However, if targeting is poor and subject to serious inclusion and exclusion errors, a universal scheme becomes attractive, but the per-capita transfer amount has to be smaller.

While all anti-poverty policies (or, more narrowly transfer policies) and programmes compete for fixed resources (including state capacity) and therefore are substitutes, still there are some interesting ways in which complementarities between these different policies can be and are being explored, such as what are now referred to as “cash-plus” polices.Footnote 7 Subject to the basic budget constraint concerning lumpy transfers versus smaller amounts aimed at providing a safety net, whatever amount per person is feasible budget-wise, these can be most effective when combined with other programmes. BRAC’s policy aimed at the poorest sections was developed in the early 2000s when it became clear that existing microfinance and anti-poverty programmes were not being effective with this group. The key elements of the new policy that BRAC adopted include: meeting the basic needs of households participating in the programme that typically takes the form of a cash transfer and basic food supplies which serve as a safety net that the poor can count on while investing in improving livelihoods; ensuring that participants and their families have access to essential services such as education, health services, water, and sanitation. To enable participants to earn a sustainable income during the programme, they are provided with a productive asset and/or training. They are also provided training on how to manage income and expenditures, encouraging them to save, and connecting them with financial services.

There is another sense in which different types of transfer policies can be complementary—those excluded by one can be picked up by others. For example, CCTs have been successful in improving the outcomes they target (e.g. education), they can undermine the social protection value of the transfers by denying them to those who fail to satisfy the conditions (Özler 2020). Hence, even the best CCT programmes need to be complemented with other interventions and in this context UCTs are becoming more popular, especially in low-income settings where conditionalities can be harder to put in place. In a similar way, in the Indian context, we can think of a hybrid scheme that would enable combining workfare with welfare. Consider the MGNREGS that provides 100 days of guaranteed employment in rural areas. It is not ideal for the poor who are unable to do usual manual work, for e.g. children, the elderly, the disabled. On the other hand, for those are willing and able to work, the self-targeting aspect of MGNREGS means only those who really need the money would be willing to do extra work to earn it. If an unconditional cash transfer along the lines described in the section on “A universal income transfer scheme” as a flat base amount is combined with MGNREGS where one only gets paid conditional on working, then they can complement each other in targeting different groups within the broad class of the poor.

Also, existing evidence suggests that cash transfers can be complementary to the objectives of economic recovery and employment generation, which is one of the most major challenges at present. Studies show that cash transfer programmes can have large positive effects on non-recipient households and firms. A recent study in rural Kenya studies a cash transfer programme that provided a one-time cash transfer of about USD 1000 to over 10,500 poor households with the implied fiscal shock being nearly 15% of local GDP. The study estimates a local transfer multiplier of 2.4, and minimal price inflation.Footnote 8

The pandemic has highlighted not only the importance of cash transfers but also potential complementarities between them and other welfare policies. In 2020, worldwide cash transfer benefits nearly doubled, with 214 countries and territories planning or implementing over 400 cash transfer programmes in response to the pandemic (Matin 2022).

In India, while not universal, income transfer schemes have been stepped up to deal with the pandemic, aimed at women and vulnerable groups within the poor, such as senior citizens, widows and the disabled, as well as the PM-Kisan scheme aimed at farmers. Beyond cash transfer schemes, as part of its welfare package aimed at the poor, the Indian government has also stepped up the allocation for the public distribution system (PDS) and the employment guarantee scheme (MGNREGS).

Indeed, the pandemic has highlighted some important complementarities between cash and in-kind transfer programmes. One key lesson from the unique nature of the crisis is it has impacted supply chains but also by shrinking livelihoods, it has had a negative effect on the demand-side as well. This in my view makes income transfers and in-kind transfers more of complements than substitutes. After all, what good is only income when supply chains are disrupted? Similarly, how does it matter if shops are well-stocked when a person has no money? Thinking beyond the pandemic, given the presence of relatively remote areas where supply chains are not strong and the continued sluggishness of the post-pandemic economic recovery, the basic argument continues to be relevant.

Finally, the pandemic has highlighted a fundamental complementarity between the economic relief and public health responses to the crisis.Footnote 9 Given the large size of the population who do not have salaried jobs or sufficient savings to draw on during lockdowns or a health shock they are experiencing, an economic relief package is an essential component of a public health response. After all what good is saving someone from the disease if they starve to death or the other way around? In the medium run, the obvious way forward seems to be to build on the complementarity between public health and economic interventions, to both revitalise the economy and expand the capacity of the public health system in terms of personnel, equipment, and healthcare facilities. For example, once the immediate fiscal crisis is dealt with, there is an overwhelmingly strong case for focusing public expenditure on recruiting and training healthcare workers capable of doing basic tests and providing rapid and initial responses, especially in areas not well served by health services. It would generate both a critical first line of defence for our healthcare system, as well as provide training and employment opportunities as the economy continues along the path to recovery.

Concluding remarks

This paper proposed a conceptual framework to evaluate different kinds of direct transfer policies to the poor, ranging from one-off asset transfers to regular transfers in cash or kind, and identified a few critical dimensions that are important for evaluating their relative strengths and weaknesses, ranging from what specific constraints the poor face, the time horizon, and the social objective (e.g. providing consumption support to as broad a group as possible vs making lumpy asset transfers to a few that would help them escape poverty in the long run). We argued that these transfer programmes often show that the classic equity-efficiency trade-off may not apply in this context as these transfers may have direct gains in terms of the productivity of the poor. We also discussed potential complementarities between different types of transfer programmes.

Notes

See Ghatak (2015).

This section is based on Balboni et al (2022).

See Ghatak (2015) for an overview. Here we focus on the individual and the persistence of poverty of individuals.

In our study villages, there are no functioning rental or credit markets that would allow households to buy access to these assets for a share of the time and the price, thus dividing the investment into smaller parts.

This section draws on Ghatak and Muralidharan (2021).

See Gupta, Ghosh, and Hussain (2022).

See Matin (2022).

Egger, Haushofer, Miguel, Niehaus, and Walker (2022).

See Roy and Ghatak (2020).

References

Balboni C, Bandiera O, Burgess R, Ghatak M, Heil A (2022) Why do people stay poor? Quart J Econ 137(2):785–844

Bandiera O, Burgess R, Das N, Gulesci S, Rasul I, Sulaiman M (2017) Labor markets and poverty in village economies. Q J Econ 132(2):811–870

Banerjee A, Hanna R, Olken BA, Lisker DS (2023) Social protection in the developing world. J Econ Lit, Forthcoming

Bardhan P (2016) Universal basic income – its special case for India. Indian J Hum Dev 11(2):141–143

Egger D, Haushofer J, Miguel E, Niehaus P, Walker MW (2022) General equilibrium effects of cash transfers: experimental evidence from Kenya. Econometrica 90(6):2603–2643

Fotta M, Schmidt M (2022) Cash transfers. In: Stein F (ed) The open encyclopedia of anthropology. https://doi.org/10.29164/22cashtransfer.

Garland D (2016) The welfare state—a very short introduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Ghatak M (2015) Theories of Poverty Traps and Anti-Poverty Policies. World Bank Econ Rev 29(Supplement 1):S77–S105

Ghatak M, Maniquet F (2019) Universal basic income: some theoretical aspects. Annu Rev Econ 11(895–928):2019

Ghatak M, Muralidharan K (2021) An inclusive growth dividend: reframing the role of income transfers in India’s Anti-Poverty Strategy. In: Shah S, Bosworth B, Muralidharan K (eds) India Policy Forum 2019, vol 16. Sage Publications, New Delhi

Gupta A, Ghosh I, Hussain S (2022) What two new surveys say about the state of DBT's last mile woes. The Wire, April 7, 2022

Joshi V (2016) Universal basic income supplement for India: a proposal. Indian J Hum Dev 11(2):144–149

Matin I (2022) What ‘cash plus’ programs teach us about fighting extreme poverty. Stanford Social Innovation Review, January 5, 2022

Ministry of Finance, Government of India (2017) Economic Survey (2016–17). https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget2017-2018/es2016-17/echapter.pdf

Özler B (2020) How should we design cash transfer programs?, Let’s Talk Development, World Bank Blogs

Roy AL, Ghatak M (2020) The twin crises of covid-19 and how to resolve them, The India Forum, April 28

World Bank (2018) The state of social safety nets 2018. World Bank, Washington, DC

Funding

No funding was received for this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghatak, M. Direct transfer policies for the poor. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-023-00306-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-023-00306-4