Abstract

This paper, through an analysis of the relationship between internationalization and a novel concept of performance at the firm level, sheds new light on this stream of literature, as our analysis presents a new approach by examining the internationalization-performance relationship at the firm level and arguing that this relationship is dependent on firm-specific assets. To test this argument, we use a sample of 267 manufacturing firms in Spain. We use a Bayesian stochastic frontier model with random coefficients to adequately capture the heterogeneity of resources across firms. The results reveal that the effect of internationalization on performance is heterogeneously distributed across firms. Finally, the strategic implications of these results for achieving a sustained competitive advantage by firms are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As a consequence of the globalization of markets, due mainly to the dismantling of tariff barriers and strong technological advances, internationalization has become one of the main strategies for both small and large-sized enterprises (Lu & Beamish, 2001). The phenomenon of internationalization has provoked a growing interest in researchers for decades, who attempt to understand its effects on firm performance. Thus, there are extensive theoretical and empirical studies that addresses the internationalization-firm performance (I-P) relationship (e.g., Arora et al., 2018; Assaf et al., 2012; Buckley & Tian, 2017a, b; Contractor, 2012; Contractor et al., 2007; Contractor et al., 2003; Lu & Beamish, 2001, 2004, 2006; Michel & Shaked, 1986; Verbeke & Brugman, 2009; Woo et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2022).

Academics have relied on various theoretical approaches to explain the I-P relationship, such as organizational learning (Lavie & Miller, 2008; Ruigrok & Wagner, 2003), cognitive and organizational psychology (Lu & Beamish, 2004), transaction cost (Hennart, 2007) and the resource-based view (RBV) (Kotabe et al., 2002). There is no doubt that these different theoretical approaches have helped to better understand the I-P relationship. However, research on the I-P relationship has not provided conclusive results, and the findings are inconsistent and contradictory (Ruigrok & Wagner, 2003). While some authors consider that such inconclusive results are due to a measurement problem (e.g., Goerzen & Beamish, 2003; Richter et al., 2017), others think that these results also reflect different theoretical approaches (Miller et al., 2016).

Most empirical studies on the I-P relationship consider that firms are homogeneous, ignoring the importance of the heterogeneity of resources between firms (Kotabe et al., 2002). In this sense, Barney (1991) points out that the main source of the differences in firm performance is the heterogeneity of resources. Similarly, the theory of international business suggests that in general, it is expected that firm-specific assets (FSAs) or firm-specific advantages condition the impact of internationalization strategies on performance (e.g. Rugman & Verbeke, 2003; Rugman et al., 2011; Tashman et al., 2019; Verbeke & Forootan, 2012). That is, FSAs can be sources of competitive advantages for firms in their international expansion.

In addition to not adequately incorporating heterogeneity into the empirical tests on the I-P relationship, the firm performance measure used in previous empirical research also has serious drawbacks (Pangarkar, 2008; Richter et al., 2017). For example, Richter et al. (2017) note that most research on the I-P relationship uses financial indicators to measure performance and questions whether these indicators adequately reflect the theoretical costs and benefits of internationalization. These authors argue “that studies can benefit from incorporating more operational performance indicators, such as efficiency measures” (2017: 95). Likewise, the use of financial-accounting indicators as measures of firm performance requires a reference point to be significant, which is not always easy to find (Assaf et al., 2012).

Therefore, the nature of the I-P relationship is not clear, and thus, a more in-depth study is needed. Furthermore, it is important for managers to know if an internationalization strategy provides an opportunity to achieve sustained competitive advantage (Hamel & Prahalad, 1985). Consequently, the question of how internationalization affects firm performance continues to be an important research topic in the field of business internationalization (Richter et al., 2017). The purpose of this paper is to try to fill the two previously mentioned gaps. First, we incorporate heterogeneity between firms into the empirical analysis of the I-P relationship. Second, we introduce the concept of profit efficiency as a measure of firm performance.

This paper makes two contributions to the literature. First, on the basis of the RBV, this study assumes that firms are heterogeneous, even within the same industry or strategic group, and therefore face different production frontiers. Consequently, we evaluate the I-P relationship in a sample of 267 manufacturing firms in Spain using a Bayesian stochastic frontier model with random coefficients to adequately capture heterogeneity across firms. This methodology considers that firms do not operate under a common frontier, assuming that firms are heterogeneous. This methodological approach, unlike previous methodologies, allows us to adequately gather the characteristics and internal properties of each firm. Second, this study innovates by introducing a performance measure (profit efficiency) that better evaluates the overall performance of a firm than does traditional financial or accounting measures. To the best of our knowledge, profit efficiency has not been used before in the I-P context.

The results suggest that when there is heterogeneity between firms, the shape and positive (or negative) sign of the I-P relationship are unevenly distributed among firms in the sample, depending on FSAs. The rest of the study is structured as follows. In Section 2, we review the literature. Next, we present the theoretical development and generate our hypotheses. Section 4 describes the data and methodology. Section 5 presents and discusses the results. The conclusions are reported in Section 6.

2 Literature review

The effect of internationalization on firm performance is a crucial issue for both the theory and practice of firm internationalization (Assaf et al., 2012). As indicated above, there is extensive literature on the I-P relationship. This literature describes the conditions under which a firm that decides to implement an internationalization strategy can improve its performance (Gomes & Ramaswamy, 1999; Grant, 1987; Kogut, 1985).

In general, the idea that international expansion is beneficial for firms is a central argument in studies on business internationalization (Contractor et al., 2007). Firms are internationalized because they expect a benefit from the imperfections of international markets (Lu & Beamish, 2004; Ruigrok & Wagner, 2003). Thus, some studies rely on the theory of organizational learning to argue that internationalized firms can improve their profit by taking advantage of learning to operate in similar markets (Ghoshal, 1987). This approach suggests that selling in different geographic markets allows firms to accumulate experience, increasing their knowledge and competitiveness (Friesenbichler & Reinstaller, 2023; Hitt et al., 1997; Lu & Beamish, 2004; Rashid, Hassan, & Karamat, 2021; Ruigrok & Wagner, 2003). Other studies are based on the theory of foreign direct investment (Daniels & Bracker, 1989) and argue that internationalization can yield positive returns derived from greater cost efficiency by exploiting economies of scale and scope (Caves, 1971; Grant, 1987) and that it helps to reduce revenue fluctuation and volatility by diversifying risk by selling in different countries (Kim et al., 1993).

Some academics adopt a more managerial approach and focus on the internal resources of firms to explain the source of the benefits of internationalization. In this sense, the theory of the multinational firm suggests that a firm can be more profitable by developing specific competencies by expanding its resources (tangible and intangible) to international markets (Buckley, 1989). Along the same lines, some studies examine the role of FSAs in the internationalization process of firms (e.g., Buckley & Tian, 2017a, b; Gkypali et al., 2015; Kirca et al., 2016; Tashman et al., 2019; Tomàs-Porres et al., 2023). In general, these studies suggest that FSAs and the degree of internationalization are reciprocally related and that this relationship positively affects firm performance (Buckley & Tian, 2017b; Tashman et al., 2019).

All these theories emphasize the benefits of operating in international markets. However, the literature also recognizes the important costs associated with international expansion, mainly in the initial stage (Lee et al., 2014). Some of the costs derived from internationalization are related to the higher costs of coordination and communication, the cultural costs that arise when operating in different geographic markets, the costs of managing a more complex supply chain and the costs derived from the exchange rate risk (Ruigrok & Wagner, 2003; Thomas & Eden, 2004). Likewise, as firms operate in a greater number of international markets, their structure and processes may not adapt to the new global environment of the firm, generating additional costs (Gomes & Ramaswamy, 1999). These internationalization costs can negatively affect performance.

All these benefits and costs are used to hypothesize concerning the I-P relationship (Richter et al., 2017). Table 1 shows a summary of the previous literature on the I-P relationship. As seen, the results are both contradictory and inconclusive. Part of the empirical literature suggests that on average, as firms expand internationally, such expansion has a positive and linear effect on firm performance (Buckley & Tian, 2017a, b; Delios & Beamish, 1999; Grant, 1987; Hsu & Pereira, 2008). The main reasons for this positive effect are the possibility of exploiting economies of scale, providing better and more flexible access to resources and allowing greater learning (Hennart, 2007).

However, Gomes and Rasmaswamy (1999) argue that beyond some optimal degree of internationalization, the costs may exceed the benefits. Consequently, the I-P relationship is not always necessarily linear and positive. Thus, other studies suggest a U-shaped I-P relationship (Assaf et al., 2016; Assaf et al., 2012; Capar & Kotabe, 2003; Contractor et al., 2007; Feng et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2014; Lu & Beamish, 2001; Ruigrok & Wagner, 2003; Shih-Yung et al., 2019). These studies suggest that in the initial stage of internationalization, the performance of the firm is negative and as time passes becomes positive as a result of the process of organizational learning through international experience.

In contrast, other authors find that the I-P relationship has an inverted U shape (Daniel & Braker, 1989; Gomes & Ramaswamy, 1999; Hitt et al., 1997; Qian, 2002; Woo et al., 2019). This configuration suggests that geographic expansion allows for greater performance up to a certain threshold from which the organizational costs and complexity associated with the management of multiple dispersed activities begin to be greater than the benefits that can be derived from international expansion (Contractor et al., 2003).

However, other researchers note that the initial efforts involved in internationalization can generate additional costs as well as overinternationalization, thus being detrimental to performance (Miller et al., 2016; Cho & Lee, 2018; Contractor et al., 2003; Lu & Beamish, 2004). This approach considers that the process of international expansion is developed in three stages and is known as the horizontal S-shaped curve. In the first stage, the initial costs involved in the internationalization process are higher than the benefits. In a second stage, the profits of international expansion exceed the costs. Finally, if international expansion goes beyond a certain optimal threshold, the increase in costs is greater than the increase in profits (Contractor et al., 2003).

Finally, some authors suggest that the I-P relationship is negative (Michel, & Shaked, 1986; Ramaswamy, 1993, 1995) or not significant (Hennart, 2007; Shaked, 1986) because firms are not at their optimal threshold of internationalization due to excessive or insufficient international diversification.

Table 1 also shows that much of the previous literature has examined the I-P relationship in developed countries, with a focus on the average I-P relationship (e.g., Assaf et al., 2012; Contractor, 2012; Contractor et al., 2007; Woo et al., 2019), assuming homogeneity across sample firms or, in the best of cases, the inadequate collection of heterogeneous information. In this sense, some studies have shown that knowing the average effect of a strategy on firm performance (positive or negative) does not necessarily imply that the direction and intensity of this effect can be inferred for a firm-specific strategy (Hansen et al., 2004; Mackey et al., 2017). Rather, the effect of a firm-specific strategy on performance will depend on its resources and capabilities and the context in which it operates and not so much on the average effect of that strategy on performance for a sample of firms (Mackey et al., 2017).

Additionally, most of the previous literature on the I-P relationship (see Table 1), uses traditional measures of performance, such as return on assets (ROA) or return on equity (ROE), assuming that shareholders appropriate all returns generated by a firm. This shareholder perspective is not consistent with the RBV’s economic profit generation model (Barney, 2018). Many of the returns that create a competitive advantage are appropriated by other stakeholders (Coff, 1999), in addition to shareholders. Consequently, it is possible that not all the profits of a resource-based competitive advantage are reflected in financial or accounting measures of firm performance.

In summary, previous literature has examined the I-P relationship using different theoretical approaches. However, no research exists that has adequately incorporated heterogeneity between firms and used a performance measure that captures all the benefits of competitive advantage. Thus, this research aims to examine the I-P relationship considering heterogeneity and using an innovative measure of performance.

3 Theory development and hypotheses

The RBV constitutes the theoretical basis of this research. The RBV is one of the most popular theories in the strategic management literature (Cooper et al., 2023). From an analytical perspective, the point of view of this theory assumes that the competitive position of a firm depends on the specialization of its resources and capabilities and focuses its attention on their optimal use to create sustained competitive advantages that allow the firm to achieve above-normal performance. This specialization will lead to firms to be, even within the same industry or strategic group, heterogeneous in terms of the resources and relevant capabilities to implement their strategies. Moreover, due to the imperfect mobility of these resources, heterogeneity will be maintained over time (Barney, 1991). Therefore, in the RBV framework, the main source of differences in firm performance is the heterogeneity of resources (tangible and intangible) across firms. In an internationalization strategy, the diversity of products, processes, markets and specific knowledge of a firm can not only be a source of a sustained competitive advantage and, therefore, greater profitability but can also act as a barrier to the entry of potential competitors in the international sphere (Annavarjula & Beldona, 2000).

Some of the extensive literature on the I-P relationship adopts a theoretical approach focused on the internal resources and capabilities of firms, FSAs or firm-specific advantage to explain the sources of the benefits derived from internationalization (e.g., Hitt et al., 2006; Kotabe et al., 2002; Rugman et al., 2011; Rugman & Verbeke, 2003; Tashman et al., 2019; Verbeke & Forootan, 2012), implicitly assuming heterogeneity across firms. For example, Caves (1996) notes that an important aspect that can condition the effect of an internationalization strategy on performance is FSAs. Lu and Beamish (2004) emphasize that FSAs have a positive impact on the I-P relationship. For Hitt et al. (2006), the necessary condition for a firm to be successful in international expansion is to possess valuable, rare and inimitable resources. Kotabe et al. (2002) suggest that the effect of internationalization on firm performance depends on FSAs. Buckley and Tian (2017b) indicate that knowledge-based assets mediate the relationship between transnationality and financial performance. Tashman et al. (2019) rely on the RBV to argue that FSAs are sources of competitive advantages that can be used by firms in their international expansion.

However, although, from a theoretical point of view, the importance of resource heterogeneity is recognized as a source of competitive advantage, much of the empirical literature on the I-P relationship ignores or does not adequately capture this heterogeneity. Thus, most empirical studies examine the effect of internationalization on the performance of a “hypothetical” average firm, focusing on the average relationship between internationalization strategies and firm performance (Assaf et al., 2012; Contractor, 2012; Contractor et al., 2007; Woo et al., 2019). This mismatch between the theoretical literature and empirical studies questions whether the results of these studies can be inferred to be firm-specific when the allocation of resources between firms differs (Hansen et al., 2004).

In summary, in the RBV framework, the resources and capabilities of the firm are a source of competitive advantage if they are heterogeneously distributed across firms (Barney, 1991). Therefore, it is expected that from the perspective of the RBV, firms will use their unique resources and capabilities to increase profits from their international expansion strategies. Thus, there is increasing evidence that firms choose international markets where they can achieve resource advantages (Assaf et al., 2015). Therefore, the shape and sign of the I-P relationship will depend on the characteristics and internal properties of each firm.

In accordance with Miller et al. (2016), we consider that international expansion has two dimensions: intensity or depth and diversity or scope. In practice, these two dimensions must be tested separately because depending on whether the firm opts for one strategy or another, the effect on performance may be different (Woo et al., 2019).

The intensity of internationalization refers to the degree of penetration of the firm in international markets and is expected to affect firm performance. On the one hand, international expansion allows a firm to access new markets, increasing its customer base and demand for goods and services. This increase in sales abroad can reduce production costs if the firm faces economies of scale (Hennart, 2007). However, it is also important to highlight that international expansion involves challenges and risks, such as cultural barriers, according to which the firm has to deal with the costs derived from the stereotypes of foreign consumers (Eden & Miller, 2004), regulatory barriers, organizational difficulties such as the processing costs of information (Miller et al., 2016), and exchange and logistics risks. According to the RBV framework, the heterogeneity of resources across firms means that these benefits and drawbacks of the intensity of international expansion affect the performance of firms differently. Therefore, it is expected that the relationship between internationalization intensity and firm performance varies across firms depending on the FSAs. Based on the presented arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis (1): The direction of the relationship between internationalization intensity and firm performance depends on the firm's ability to leverage its specific assets in international contexts.

International diversification is a strategy that involves expanding a firm's operations in multiple countries or geographic regions. International diversity entails costs and benefits that are different from those of the intensity of internationalization (Miller et al., 2016). This strategy allows the firm to reduce its dependence on a single market and take advantage of growth opportunities in different locations. In this way, the firm can (a) benefit from a reduction in risk when operating in different countries, (b) take advantage of the economies of scope derived from sharing resources in the production process, (c) access resources and talent not available or limited in the local market and (d) enrich the knowledge and skills derived from continuous learning and improvement. However, international diversification also has risks, such as the costs associated with coordination (Greve, 1998); the distribution of scarce resources such as management among a greater number of countries, which can affect the competitiveness of the firm (D’Aveni et al., 2010); and adaptation to different business cultures. Once again, within the framework of the RBV, the heterogeneity of resources across firms can cause these costs and benefits to affect performance differently. Therefore, it is expected that the relationship between international diversification and firm performance varies across firms depending on the FSAs. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis (2): The direction of the relationship between international diversification and firm performance depends on the firm's ability to leverage its specific assets in international contexts.

These hypotheses are aimed at investigating how internationalization impacts firm performance, considering the presence of FSAs in international markets. The interaction between internationalization and FSAs is presented as a crucial element in understanding how a firm can leverage its distinctive resources in a global context without predefining the direction of the relationship between I-P. In other words, the direction of this relationship is left open so that the specific nature of this connection can be revealed by the data analysis.

4 Data and methodology

4.1 Sample and data

Our hypotheses are empirically examined in a sample of international manufacturing firms in Spain. The data were collected from the database of the State Society for Industrial Participation Foundation. Of the total number of firms, 459 were eliminated due to a lack of data availability. The final number of firms in the sample was 267 in the period from 2010 to 2017, resulting in a balanced data panel of 2,136 observations. To the research period holds relevance because of several key factors. Firstly, this period encompasses the post-financial crisis recovery phase, thus allowing us to investigate how manufacturing firms adapted and performed during this critical period. Additionally, rapid technological advancements occurred in the early 2010s, influencing how manufacturing firms engaged with international markets and shaping their performance outcomes. Furthermore, the period of 2010–2017 coincides with significant shifts in the global trade landscape, which were marked by changes in trade agreements and geopolitical factors. This context is crucial for understanding how Spanish manufacturing firms navigated these changes and the subsequent impact they had on the internationalization strategies and performance of these firms.

The reference population includes firms from the entire Spanish territory, with 10 or more workers from the manufacturing industry. The average number of employees of the firms in the sample is 240. Likewise, the sample is made up of manufacturing firms from various industries. Specifically, 14.98% of firms are agricultural and industrial machinery firms; 11.61% belong to the chemical industry and pharmaceutical products; 7.49% belong to food products and tobacco, and another 7.49% to rubber and plastic products; 6.37% are firms dedicated to textiles and clothing, and another 6.37% to ferrous and nonferrous metals; 5.99% of the firms belong to the motor vehicle industry; 5.62% belong to metal products, and another 5.62% to machinery and electrical material; and the remaining 28.46% belong to other manufacturing industries.

4.1.1 Variables

Performance

Most studies that examine the I-P relationship use accounting or financial indicators, such as return on assets (ROA) or return on equity (ROE), among others, to measure firm performance (e.g., Buckley & Tian, 2017a, b; Contractor et al., 2007; Lu & Beamish, 2001, 2004; Miller et al., 2016). These measures of firm performance have been very controversial in the literature. For example, it is possible that not all the returns generated by an internationalization strategy are reflected in some traditional financial measures of performance (Barney, 2018). That is, “… most performance measures capture only the rent that is not appropriated by the most powerful stakeholders” (Coff, 1999: 131). Furthermore, financial measures ignore the other dimensions of performance, such as the operational dimension. A purely financial measure does not take into account, for example, that the efficiency with which a firm uses its resources can be the main source of its performance (Chen et al., 2015). Operational performance is determined by underlying processes, such as the efficiency with which firms manage their resources. In the RBV framework, the mere possession of exclusive resources does not guarantee that a firm achieves a competitive advantage; further, these resources must be used efficiently (Peteraf, 1993).

This research uses efficiency as a measure of performance. Although some authors, such as Assaf et al. (2012), use the concept of cost efficiency as a performance measure to examine the I-P relationship in retail firms, this concept of efficiency does not capture the possible differences in the quality of the products of the firms, nor erroneous decisions regarding the output side (Berger & Mester, 1997). We use the concept of profit efficiency (PE) to measure firm performance. This concept measures the distance between the current profit of a firm \(\left({\pi }_{it}\right)\) and its optimal profit frontier \({(\pi }^{max})\). The optimal profit frontier represents the maximum possible profit for given conditions. Therefore, profit efficiency estimates firm performance compared to optimal performance and is based on the widely accepted economic objective of profit maximization. In addition, this concept takes into account the impact of an internationalization strategy both on the cost side and on the revenue side (creation of a greater output value) and their interaction, in line with the concept of efficiency proposed by Peteraf (1993) in the RBV framework.

Mathematically, the profit efficiency can be estimated as specified below (Berger & Mester, 1997):

where \(f\left({x}_{it}\right)\) denotes the profit function, \({v}_{it}\) random errors and \({u}_{it}\) profit inefficiency.

The profit function used in this research depends on the output quantity and price of inputs. The selected outputs should be a measure of the organization’s achievement of goals and objectives. Therefore, we specify the following output variables: 1) production of goods and 2) other operating revenue. The input variables must represent the resources necessary to obtain the outputs. Thus, we specify the following price variables for the inputs that make up the profit frontier: 1) labour price, 2) capital price and, 3) material price.

Internationalization

The literature on the I-P relationship shows that there have been multiple measures of this construct. The most frequently used measures are ratios that measure some aspects of the size of foreign operations over total firm operations, such as foreign sales over total sales, foreign assets over total assets, foreign employment to total employment, research and development intensity or advertising intensity (e.g., Ang, 2007; Buckley & Tian, 2017a; Chang & Wang, 2007; Contractor et al., 2003; Kafouros et al., 2008). Other authors use the number of overseas subsidiaries and the number of countries in which a firm has overseas subsidiaries as a measure of internationalization (Lu & Beamish, 2004).

This research conceptualizes the internationalization of firms in two dimensions, i.e., intensity and diversity, because their effect on performance can be different (Woo et al., 2019). We measure the international intensity of each firm in each year as the proportion of foreign sales with respect to its total sales (Lu & Beamish, 2001). International diversity refers to the different foreign markets where the firm expands internationally and is measured by the number of countries where a firm operates (Hitt et al., 2006; Lu & Beamish, 2004).

Control variables

Consistent with previous research, when conducting the empirical analysis, two variables were taken into account to control their potential effects on the performance of internationalized firms: size and age. We measured the size of the firm as the natural logarithm of the book value of total assets (Chang & Wang, 2007). Generally, size is related to the amount of resources available to a firm, reflecting its portfolio of resources or international expansion capacity (Hitt et al., 2006). The second control variable is the age of the firm, which is measured by the number of years since it was established (Kim & Hemmert, 2016).

To correct the variations due to the effect of prices, the data have been deflated according to the price index, calculated as 2016 = 100. Table 2 summarizes the descriptive statistics and correlation matrix of the variables.

4.2 Empirical model

As indicated above, this research measures firm performance using profit efficiency. For this, an alternative profit function is estimated where profit is a function of the level of output and the price of inputs (Berger & Mester 1997). That is, the quantity of output is taken as given, while the price of the outputs varies freely and affects the profit. To measure the profit function, we use the translog form, which is very flexible. The most commonly used model with which to estimate profit efficiency is the stochastic frontier approach (SFA), developed by Aigner, Lovell and Schmidt (1977) and Meeusen and van Den Broeck (1977). Classic SFA assumes that all firms in a sample are homogeneous across themselves and, therefore, only differ in terms of their level of inefficiency. This leads to the estimation of a single profit frontier for all the firms in the sample, and efficiency is measured by the distance of each firm with respect to that frontier.

In our case, it does not seem realistic to assume that all internationalized firms within the manufacturing industry are homogeneous. In the manufacturing industry, multiple types of resources and capabilities coexist that cause significant variability across firms within that industry. This variability across firms introduces significant amounts of heterogeneity that if not considered properly, can lead to erroneous results (Huang, 2004).

To adequately capture this heterogeneity in the SFA, Tsionas (2002) proposes a random parameter model that allows estimating an individualized profit frontier for each firm, hence incorporating heterogeneity into the efficiency level. To illustrate, the following equation of the profit function with random coefficients is considered:

where \({\pi }_{it}\) is the profit, measured by added value, of firm \(i\) in year \(t\); the variables \({x}_{it}\) represent the output quantity [\({x}_{1,it}\) = production of goods (total net sales), and \({x}_{2,it}\)= other operating revenue] and the price of the inputs [\({x}_{3,it}\) = labour price (ratio between personnel costs and the number of full-time equivalent employees), \({x}_{4,it}\) = capital price (ratio between the depreciation of fixed assets and the fixed assets), and \({x}_{5,it}\) = material price (ratio between intermediate consumption and production of goods and services)]. It is essential to note that the input prices (labour, capital, and material) serve as proxy variables and have been calculated in the manner specified above. These proxy variables are derived from the following data extracted from our database: personnel costs (gross wages and salaries, severance payments, employer social security contributions, contributions to supplementary pension systems, and other social expenses), the number of full-time or equivalent employees (permanent and temporary employees), the depreciation of fixed assets (amortization of fixed assets and provisions), fixed assets (fixed assets net considering accumulated depreciation and provisions), intermediate consumption (purchases and external services and the net of changes in purchase inventory) and the production of goods and services (sales and the inventory variation in sold goods).

The term \({v}_{it}\)represents a random disturbance that captures the measurement error, which is distributed such that \({v}_{it}\sim N(0,{\sigma }^{2})\), and \({u}_{it}\) is a nonnegative error term with which to measure inefficiency. The parameter \(\alpha\) is the intercept, which remains fixed because it is introduced in the model as \({v}_{it}\). Finally, the parameters \({\beta }_{i}\) represent the random coefficients. For each firm in the sample, a different \(\beta\) parameter is estimated, which reflects the heterogeneity of the manufacturing industry.

The SFA model also allows for the incorporation of determinants that explain the differences in inefficiencies across firms. Traditionally, as with the frontier, the average effect of these explanatory factors has been estimated for the set of firms in the sample. However, the fact that a determinant has on average a certain value does not mean that this is the effect for each of the firms (Mackey et al., 2017). In other words, the estimation methods must take into account the individual differences of the firms and not be based on averages that statistically neutralize the differences across firms.

Therefore, we extend the model proposed by Tsionas (2002) such that the inefficiency function is formed by a set of explanatory variables but whose parameters are also random, thus being able to determine the individual effect of each determinant for each firm. It is assumed that the inefficiency function \({u}_{it}\) follows an exponential distribution, as specified below:

where the variables \({Z}_{it}\) represent the determining factors of firm \(i\) in year \(t\) (Z1 = international intensity, Z2 = international diversity, Z3 = international intensity squared, Z4 = international diversity squared, Z5 = age, and Z6 = size). In turn, \({ \gamma }_{0}\) is the intercept, and \({\gamma }_{i}\) represents the random parameters such that for each firm in the sample, a different \(\gamma\) parameter is estimated, being able to determine the individualized effect of each determinant factor on a firm.

Models (2) and (3) are estimated simultaneously using Bayesian techniques. This estimation technique is innovative in this type of study. Traditionally, most empirical studies that examine the I-P relationship in the RBV framework use models that are estimated by classic statistical methods, such as regression analysis and maximum likelihood estimation (Hansen et al., 2004). However, one of the main advantages of the Bayesian approach, and a central issue of this research, is that it allows us to isolate the effect of a strategy on performance for each firm. Bayesian models estimate full probability distributions for firm parameters. In contrast, non-Bayesian methods calculate point estimates and confidence intervals for parameters. These confidence intervals establish the effects that would be observed if the same study were replicated an infinite number of times, fixing the interval in which the value of a certain parameter moves. The information obtained is that the effect on the performance of a strategy varies between the minimum and the maximum of that interval for a given confidence level (Hansen et al., 2004). In this way, it is a matter of answering the following question: Can the null hypothesis, i.e., this parameter is equal to zero, be rejected?

However, no inference can be made on whether the most likely effect on the performance of a strategy is zero or on the average, the minimum, the maximum or any other value of the interval. Therefore, Bayesian inference acquires greater importance and utility because it does not determine if a parameter is equal to or different from zero; however, by estimating the full probability distribution for a parameter, it allows us as researchers to determine the credibility interval that shows the most likely range of values for a parameter (Zyphur & Oswald, 2015). Thus, the Bayesian model allows full probabilistic predictive inference.

According to the above, this research uses Bayesian inference as an estimation method for Models (1) and (2). Posterior values are estimated using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) procedure and the Gibbs algorithm with data augmentation (Gilks et al., 1995; Koop et al., 1995). The software used is WinBUGS 14.

5 Results and discussion

In this section, we present and discuss the results obtained when estimating the effect of internationalization on the performance of 267 firms using the model described above. Table 3 provides the posterior means, standard deviations and 97.5% confidence intervals for the profit function parameters, from which profit efficiency is evaluated for each firm in the sample. The results were obtained using 100,000 MCMC iterations after discarding the first 10,000 to avoid the sensitivity of the initial values. Although the coefficients for each firm are not reported, a significant degree of variability in these coefficients across firms is observed. This result reveals that the firms in the sample face different profit frontiers, confirming the existence of heterogeneity. Table 4 provides the posterior means of the coefficients of the determinants of the inefficiency function.

Table 5 provides the probability of a positive effect on performance for each determinant of profit inefficiency. Note that this probability does not represent the size of the effect. Clearly, a probability greater than 0.5 indicates that the effect on profit efficiency is more likely to be positive. That is, when the probability that international intensity (Z1) has a positive effect on profit efficiency is 68.91%, the probability that the effect is negative is 31.09%.

Our hypothesis suggests that the direction of the relationship between I-P depends on the firm's ability to leverage its specific assets in international contexts. Therefore, the focus of our interest is to examine the I-P relationship at the firm level and not for a “hypothetical” average firm. The average value when the sample of firms is heterogeneous can lead to inaccurate results. For example, note that in Table 4, the posterior mean of Z1 is 0.1392, indicating that, on average, an increase in the degree of international intensity has a positive effect on profit efficiency of 13.92%. This average result only allows us to conclude that it is more likely that the percentage of firms in the sample whose performance increases when internationalized is greater than the percentage of firms whose performance decreases when internationalized. That is, if the number of firms that increase performance is greater than the number of firms that reduce it, the regression coefficient between internationalization and performance is positive. Otherwise, the coefficient will be negative.

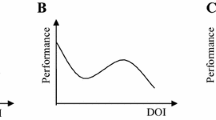

The methodology used in this study is designed to estimate the effect of an internationalization strategy on firm performance. As commented, one of the advantages of Bayesian models is that they estimate probability distributions for parameters and allow for the effects of each firm to be isolated and the results to be interpreted at the firm level. This probability distribution does not represent a confidence interval or the probability that the “true parameter” is different from zero (Mackey et al., 2017: 333). Likewise, knowing the distribution of a parameter allows determining the probability that this parameter is greater or less than any desired value. Figure 1 shows the probability distribution of the international intensity and international diversity parameters.

The area under the curve to the right of zero for each of the probability distributions represented in Fig. 1 shows the probability that the effect of international intensity and international diversity on profit efficiency is positive. Similarly, the area under the curve to the left of zero shows the probability that the effect is negative. In the case of international intensity, the probability that the effect is positive is 68.91%. Likewise, it is observed that the curve for this probability distribution peaks at approximately 0.5, indicating that the most likely effect on profit efficiency of an increase in the degree of international intensity is 50%.

As mentioned previously, suggesting that a strategy may, on average, increase or decrease performance is very problematic. However, if we consider the individual effect for each firm, for 68.91% of the firms the effect on performance of the linear term of international intensity is positive, while for 31.09% of firms, this effect is negative. The effect of the squared term of international intensity on profit efficiency is positive for 96.63% of the firms; therefore, this effect is negative for 3.37% of firms. The joint evaluation of the linear term and its square results in three subsets of firms for which the sign and shape of the I-P relationship is different.

In the first subset of 184 firms (68.91%), the effect of the linear term of the international intensity variable is positive, and the effect of this variable squared is also positive. This finding indicates that in this subset of firms, as international intensity increases, the positive effect of this variable on profit efficiency is more than proportional. This subset of firms has unique resources and capabilities that they have developed or acquired over time and that have allowed them to gain competitive advantages in their international intensity strategy and, therefore, improve their performance.

A second subset of nine firms (3.37%) exists where the effect of the linear term of the international intensity variable is negative and the effect of this squared variable is also negative. In this case, as international intensity increases, profit efficiency decreases more than proportionally, most likely because these firms do not have the necessary attributes and internal properties to be successful in the international intensity strategy.

Finally, for a subset of 74 firms (27.72%), the effect of the linear term of the international intensity variable is negative, and the effect of this squared variable is positive, indicating that the relationship between international intensity and profit efficiency for this subset of firms is U-shaped. For these firms, at an early stage, when the degree of international intensity is low, their performance does not improve. However, as international intensity increases, it is possible that these firms have acquired or developed resources and/or strategic capabilities for international intensity, which helps performance improve at a later stage. That is, the performance of these firms first decreases and subsequently increases as international intensity increases.

This result suggests that the relationship between international intensity and firm performance is heterogeneous across the firms in the sample. Therefore, when the firm-level relationship is examined, the positive (or negative) effect and shape of the relationship between international intensity and firm performance are unevenly distributed across firms in the sample, as determined by FSAs. Consequently, we accept Hypothesis 1.

Likewise, as seen in Table 4, the relationship between international diversity and performance has a posterior mean of 0.5154, indicating that for the average of the firms in the sample, the effect of this variable is positive and approximately 51.54%. Again, if we consider the firm-level effect instead of the average effect, the results in Table 5 indicate that for 85.39% of the firms in the sample, the linear term international intensity has a positive effect on performance, and for 14.61% of the firms in the sample, this effect is negative. Table 5 also indicates that the effect of the squared term of international diversity on profit efficiency is negative for 100% of the firms in the sample. In this case, the joint evaluation of the linear term and its square results in two subsets of firms for which the sign and the shape of the I-P relationship are different.

In the first subset of 228 firms (85.39%), the effect of the linear term of the international diversity variable is positive, and the effect of this variable squared is negative. This finding indicates that the relationship for this subset of firms between international diversity and profit efficiency has an inverted U shape. A probable explanation is that this subset of firms has resources and/or strategic capabilities that lead to international diversity improving their performance in the initial stage. However, at a later stage, international diversity decreases the performance of these firms. That is, the performance in this subset of firms first increases and then decreases with international diversity.

A second subset of 39 firms (14.61%) exist for which the effect of the linear term of the international diversity variable is negative and the effect of this squared variable is also negative. This finding indicates that as international diversity increases, profit efficiency decreases more than proportionally in this subset of firms, probably because it does not have the necessary resources and strategic capabilities to implement this type of strategy.

Again, the previous result suggests that the relationship between international diversity and firm performance is heterogeneous across the firms in the sample. Therefore, the shape and positive (or negative) effect of the relationship between international diversity and firm performance is unevenly distributed across the firms in the sample, depending on the FSAs. Therefore, we also accept Hypothesis 2.

Finally, the results in Table 5 also show that for 97.38% of internationalized firms, mature firms have greater profit efficiency (or a decrease in profit efficiency for 2.62% of firms). Similarly, the results suggest that for 39.33% of internationalized firms, a larger size increases profit efficiency (or decreases profit efficiency for 60.67% of firms).

6 Conclusions and implications

With the increase in international competition and saturated markets, internationalization continues to be one of the crucial strategies for firms. However, there is currently a debate about whether internationalization truly increases firm performance and under what conditions. There is abundant empirical literature that addresses the average I-P relationship, obtaining contradictory results. This stream of literature implicitly assumes homogeneity across the firms in the sample or does not adequately capture heterogeneity across firms. However, examining the average relationship is inconsistent with the RBV of the firm because the central premise of this theory holds that the main source of the differences in firm performance is the heterogeneity of resources. The objective of this research is to present a new approach to the literature by examining the I-P relationship at the firm level, assuming the heterogeneity of resources across firms.

The results support our hypothesis that the shape and the sign of the effect of internationalization on firm performance are unevenly distributed across firms, depending on FSAs. Consequently, examining the average relationship between I-P when we are in the presence of the heterogeneity of resources across firms can lead to inconclusive and contradictory results. Knowing that the average effect of internationalization on firm performance is positive only allows us to determine that the number of firms in the sample whose performance increased due to internationalization is greater than the number of firms whose performance declined.

The results of this research allow us to conclude that like any other strategy (Mackey et al., 2017), there is significant disparity across firms in the sample considering how internationalization affects their performance. Firms decide to internationalize because they desire to improve their performance. However, not all internationalized firms manage to improve their performance and to do so at the same intensity. It is expected that only those firms that manage to develop or acquire unique resources and capabilities will gain a competitive advantage and improve their performance. Therefore, the final conclusion of this study suggests that the sign and shape of the effect of internationalization on performance are unevenly distributed across the firms in the sample, depending on the provision of unique resources and capabilities of each firm. This conclusion is consistent with the central idea of the RBV that the heterogeneity of resources across firms will translate into differences in competitive advantages and firm performance (Hamel & Prahalad, 1990; Barney, 1991).

The interpretation of this conclusion is opposite of how other studies that examine the average effect of the I-P relationship are interpreted. For these studies, if the average effect is negative, an internationalization strategy is not advisable. However, a negative average effect only indicates that it is very likely that this strategy does not improve performance for a hypothetical average firm. However, even in these circumstances, a small subset of firms could have exclusive resources and capabilities that enable them to increase their performance when implementing an internationalization strategy. Specifically, when the number of firms that implement a rare and difficult-to-imitate strategy is small, it is more likely that these firms will gain competitive advantages (Barney, 1991).

Some previous research based on the RBV has studied the I-P relationship (e.g., Hitt et al., 2006; Kim & Hemmert, 2016; Tashman et al., 2019). However, although these investigations have contributed significantly to the literature, they examine the I-P relationship at the industry level and not at the firm level, despite the fact that firms are heterogeneous with respect to strategically relevant resources (Barney & Arikan, 2001). The results from our firm-level study indicate that the I-P relationship depends on the unique resources and capabilities of each firm.

This research also helps to explain the inconclusive and contradictory results of previous research (Ruigrok & Wagner, 2003; Buckley & Tian 2017b). As the results of this study suggest, depending on the specific assets that each firm has developed or acquired over time, the sign and shape of the I-P relationship will be different, even for firms within the same industry. Thus, this research finds three subsets of manufacturing firms for which the relationship between international intensity and performance has different signs and forms. It also finds two subsets of these firms for which the relationship between international diversity and performance has different signs and forms. If the heterogeneity across firms in a sample is not considered, the result of the average effect of the I-P relationship would most likely be given by the sign and the shape of the subset with the largest number of firms. In the case of the effect of international intensity on performance, the result for the subset of firms with the highest number (68.90%) was a positive effect. Regarding the effect of international diversity on performance, the largest subset of firms (85.39%) presents an inverted U-shaped relationship.

The results of this study have important theoretical and practical implications when investigating the impact of a given strategy on firm performance. Within the RBV framework, heterogeneity across firms implies that firms differ in terms of their potential for opportunities, in this case, an internationalization strategy. The Bayesian methodology allows for not only evaluating the effect of a strategy at the firm level but also knowing the probability that this effect is greater or less than zero (or any other value) and not so much if the effect is the same or different from zero (Mackey et al., 2017). In fact, the size of the effect of a strategy on firm performance may be very small, but it is unlikely to be zero. The methodology used in this study can help other investigations focus more on evaluating the probability that the effect of a strategy on firm-level performance is positive or negative rather than evaluating this relationship globally for a set of firms. The discipline of strategic management should strive to explore new methodological approaches that allow us to know the probability of a strategy for improving firm-level performance (Hahn & Doh, 2006; Hansen et al., 2004).

From a practical point of view, concluding that on average, an internationalization strategy has a positive effect on firm performance can be counterproductive for managers. This should not be interpreted as all internationalized firms increase their performance because as shown by the results of this research, some firms can increase performance while others will see a decrease. The average effect can inform managers only if a strategy is more likely to have a positive or negative effect on performance. Managers should focus on developing or acquiring those exclusive resources and capabilities that are strategic for internationalization within their industry. That is, managers, rather than determining whether the effect of internationalization on firm performance is positive or negative, should be interested in the probability and specific conditions under which an internationalization strategy improves the performance of a particular firm.

Finally, the present investigation has some limitations that future investigations could address. First, the number of firms included in the analysis is small due to the limited database. However, one of the advantages of the Bayesian methodology is that it facilitates analysis with small samples. Second, there is a small number of foreign markets in which the Spanish firms in the sample operate. Although the objective of this work was to investigate whether the sign and shape of the I-P relationship depends on the resources and capabilities of each firm, future studies could investigate which resources and capabilities are strategic for firm-level internationalization.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Abdi, M., & Aulakh, P. S. (2018). Internationalization and performance: Degree, duration, and scale of operations. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(7), 832–857.

Aigner, D., Lovell, C. K., & Schmidt, P. (1977). Formulation and estimation of stochastic frontier production function models. Journal of Econometrics, 6(1), 21–37.

Ang, S. H. (2007). International diversification: Aquick fix for pressures in company performance? University of Auckland Business Review, 9(1), 17–23.

Annavarjula, M., & Beldona, S. (2000). Multinationality-performance relationship: a review and reconceptualization. The International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 8(1), 48–67.

Arora, P., Kweh, Q. L., & Mahajan, D. (2018). Performance comparison between domestic and international firms in the high-technology industry. Eurasian Business Review, 8, 477–490.

Assaf, A. G., Josiassen, A., & Agbola, F. W. (2015). Attracting international hotels: Locational factors that matter most. Tourism Management, 47, 329–340.

Assaf, A. G., Josiassen, A., & Oh, H. (2016). Internationalization and hotel performance: The missing pieces. Tourism Economics, 22(3), 572–592.

Assaf, A. G., Josiassen, A., Ratchford, B. T., & Barros, C. P. (2012). Internationalization and performance of retail firms: a Bayesian dynamic model. Journal of Retailing, 88(2), 191–205.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Barney, J. B. (2018). Why resource-based theory's model of profit appropriation must incorporate a stakeholder perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 39(13), 3305–3325.

Barney, J. B., & Arikan, A. M. (2001). The resource-based view: Origins and implications. In M. A. Hitt, R. E. Freeman, & J. S. Harrison (Eds.), Handbook of strategic management (pp. 24–288). Blackwell.

Berger, A. N., & Mester, L. J. (1997). Inside the black box: What explains differences in the efficiencies of financial institutions? Journal of Banking & Finance, 21(7), 895–947.

Buckley, P. J. (1989). The Institutionalist Perspective on Recent Theories of Direct Foreign Investment: A Comment on McClintock. Journal of Economic Issues, 23(3), 879–885.

Buckley, P. J., & Tian, X. (2017a). Internalization theory and the performance of emerging-market multinational enterprises. International Business Review, 26(5), 976–990.

Buckley, P. J., & Tian, X. (2017b). Transnationality and financial performance in the era of the global factory. Management International Review, 57(4), 501–528.

Capar, N., & Kotabe, M. (2003). The relationship between international diversification and performance in service firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(4), 345–355.

Caves, R. E. (1971). International corporations: The industrial economics of foreign investment. Economica, 38(149), 1–27.

Caves, R. E. (1996). Multinational enterprise and economic analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Chang, S. C., & Wang, C. F. (2007). The effect of product diversification strategies on the relationship between international diversification and firm performance. Journal of World Business, 42(1), 61–79.

Chen, C. M., Delmas, M. A., & Lieberman, M. B. (2015). Production frontier methodologies and efficiency as a performance measure in strategic management research. Strategic Management Journal, 36(1), 19–36.

Cho, J., & Lee, J. (2018). Internationalization and performance of Korean SMEs: the moderating role of competitive strategy. Asian Business & Management, 17(2), 140–166.

Coff, R. W. (1999). When competitive advantage doesn't lead to performance: The resource-based view and stakeholder bargaining power. Organization Science, 10(2), 119–133.

Contractor, F. J. (2012). Why do multinational firms exist? A theory note about the effect of multinational expansion on performance and recent methodological critiques. Global Strategy Journal, 2(4), 318–331.

Contractor, F. J., Kumar, V., & Kundu, S. K. (2007). Nature of the relationship between international expansion and performance: The case of emerging market firms. Journal of World Business, 42(4), 401–417.

Contractor, F. J., Kundu, S. K., & Hsu, C. C. (2003). A three-stage theory of international expansion: The link between multinationality and performance in the service sector. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(1), 5–18.

Cooper, C., Pereira, V., Vrontis, D., & Liu, Y. (2023). Extending the resource and knowledge-based view: Insights from new contexts of analysis. Journal of Business Research, 156, 113523.

Daniels, J. D., & Bracker, J. (1989). Profit performance: do foreign operations make a difference? Management International Review, 29(1), 46–56.

D’Aveni, R. A., Dagnino, G. B., & Smith, K. G. (2010). The age of temporary advantage. Strategic management journal, 31(13), 1371–1385.

Delios, A., & Beamish, P. W. (1999). Geographic scope, product diversification, and the corporate performance of Japanese firms. Strategic Management Journal, 20(8), 711–727.

Eden, L., & Miller, S. R. (2004). Distance matters: Liability of foreignness, institutional distance and ownership strategy. Theories of the Multinational Enterprise: Diversity Complexity and Relevance, 16, 187–221.

Feng, D., Chen, Q., Song, M., & Cui, L. (2019). Relationship between the degree of internationalization and performance in manufacturing enterprises of the Yangtze river delta region. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 55(7), 1455–1471.

Freixanet, J., & Rialp, J. (2022). Disentangling the relationship between internationalization, incremental and radical innovation, and firm performance. Global Strategy Journal, 12(1), 57–81.

Friesenbichler, K. S., & Reinstaller, A. (2023). Small and internationalized firms competing with Chinese exporters. Eurasian Business Review, 13(1), 167–192.

Ghoshal, S. (1987). Global strategy: An organizing framework. Strategic Management Journal, 8(5), 425–440.

Gilks, W. R., Richardson, S., & Spiegelhalter, D. (Eds.). (1995). Markov chain Monte Carlo in practice. CRC.

Gkypali, A., Rafailidis, A., & Tsekouras, K. (2015). Innovation and export performance: do young and mature innovative firms differ? Eurasian Business Review, 5, 397–415.

Goerzen, A., & Beamish, P. W. (2003). Geographic scope and multinational enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 24(13), 1289–1306.

Gomes, L., & Ramaswamy, K. (1999). An empirical examination of the form of the relationship between multinationality and performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(1), 173–187.

Grant, R. M. (1987). Multinationality and performance among British manufacturing companies. Journal of International Business Studies, 18(3), 79–89.

Greve, H. R. (1998). Performance, aspirations, and risky organizational change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(1), 58–86.

Hahn, E. D., & Doh, J. P. (2006). Using Bayesian methods in strategy research: an extension of Hansenet al. Strategic Management Journal, 27(8), 783–798.

Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (1985). Do you really have a global strategy? The International Executive, 27(3), 13–14.

Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (1990). The core competence of the corporation. Harvard business review, 68(3), 79–91.

Hansen, M. H., Perry, L. T., & Reese, C. S. (2004). A Bayesian operationalization of the resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 25(13), 1279–1295.

Hennart, J. F. (2007). The theoretical rationale for a multinationality-performance relationship. Management International Review, 47(3), 423–452.

Hitt, M. A., Hoskisson, R. E., & Kim, H. (1997). International diversification: Effects on innovation and firm performance in product-diversified firms. Academy of Management Journal, 40(4), 767–798.

Hitt, M. A., Tihanyi, L., Miller, T., & Connelly, B. (2006). International diversification: Antecedents, outcomes, and moderators. Journal of Management, 32(6), 831–867.

Hsu, C. C., & Pereira, A. (2008). Internationalization and performance: The moderating effects of organizational learning. Omega, 36(2), 188–205.

Huang, H. C. (2004). Estimation of technical inefficiencies with heterogeneous technologies. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 21, 277–296.

Kafouros, M. I., Buckley, P. J., Sharp, J. A., & Wang, C. (2008). The role of internationalization in explaining innovation performance. Technovation, 28(1–2), 63–74.

Kim, J. J., & Hemmert, M. (2016). What drives the export performance of small and medium-sized subcontracting firms? A study of Korean manufacturers. International Business Review, 25(2), 511–521.

Kim, W. C., Hwang, P., & Burgers, W. P. (1993). Multinationals' diversification and the risk-return trade‐off. Strategic Management Journal, 14(4), 275–286.

Kirca, A. H., Fernández, W. D., & Kundu, S. K. (2016). An empirical analysis and extension of internalization theory in emerging markets: The role of firm-specific assets and asset dispersion in the multinationality-performance relationship. Journal of World Business, 51(4), 628–640.

Kogut, B. (1985). Designing global strategies: Comparative and competitive value-added chains. Sloan Management Review, 27(summer), 15–28.

Koop, G., Osiewalski, J., & Steel, M. F. (1995). Bayesian long-run prediction in time series models. Journal of Econometrics, 69(1), 61–80.

Kotabe, M., Srinivasan, S. S., & Aulakh, P. S. (2002). Multinationality and firm performance: The moderating role of marketing and R&D capabilities. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(1), 79–97.

Lavie, D., & Miller, S. R. (2008). Alliance portfolio internationalization and firm performance. Organization Science, 19(4), 623–646.

Lee, S., Koh, Y., & Xiao, Q. (2014). Internationalization and financial health in the US hotel industry. Tourism Economics, 20(1), 87–105.

Lu, J. W., & Beamish, P. W. (2001). The internationalization and performance of SMEs. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 565–586.

Lu, J. W., & Beamish, P. W. (2004). International diversification and firm performance: The S-curve hypothesis. Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 598–609.

Lu, J. W., & Beamish, P. W. (2006). SME internationalization and performance: Growth vs. profitability. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 4(1), 27–48.

Mackey, T. B., Barney, J. B., & Dotson, J. P. (2017). Corporate diversification and the value of individual firms: A Bayesian approach. Strategic Management Journal, 38(2), 322–341.

Meeusen, W., & van Den Broeck, J. (1977). Efficiency estimation from Cobb-Douglas production functions with composed error. International Economic Review, 18(2), 435–444.

Michel, A., & Shaked, I. (1986). Multinational corporations vs. domestic corporations: Financial performance and characteristics. Journal of International Business Studies, 17(3), 89–100.

Miller, S. R., Lavie, D., & Delios, A. (2016). International intensity, diversity, and distance: Unpacking the internationalization–performance relationship. International Business Review, 25(4), 907–920.

Pangarkar, N. (2008). Internationalization and performance of small-and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of World Business, 43(4), 475–485.

Peteraf, M. A. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage: a resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14(3), 179–191.

Qian, G. (2002). Multinationality, product diversification, and profitability of emerging US small-and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(6), 611–633.

Ramaswamy, K. (1993). Multinationality and performance: an empirical examination of the moderating effect of configuration. Academy of Management Proceedings, 1, 142–146.

Ramaswamy, K. (1995). Multinationality, configuration, and performance: A study of MNEs in the US drug and pharmaceutical industry. Journal of International Management, 1(2), 231–253.

Rashid, A., Hassan, M. K., & Karamat, H. (2021). Firm size and the interlinkages between sales volatility, exports, and financial stability of Pakistani manufacturing firms. Eurasian Business Review, 11, 111–134.

Richter, N. F., Schmidt, R., Ladwig, T. J., & Wulhorst, F. (2017). A critical perspective on the measurement of performance in the empirical multinationality and performance literature. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 13(2), 94–118.

Rugman, A. M., & Verbeke, A. (2003). Extending the theory of the multinational enterprise: Internalization and strategic management perspectives. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(2), 125–137.

Rugman, A. M., Verbeke, A., & Nguyen, Q. T. (2011). Fifty years of international business theory and beyond. Management International Review, 51(6), 755–786.

Ruigrok, W., & Wagner, H. (2003). Internationalization and performance: An organizational learning perspective. MIR: Management International Review, 43(1), 63–83.

Shaked, I. (1986). Are multinational corporations safer? Journal of International Business Studies, 17(1), 83–106.

Shih-Yung, W., Li-Wei, L., & Su-Mei, G. (2019). The influence of internationalization degree on the performance of industry-specific companies: A case study of Taiwan (2001–2017). International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 9(4), 212–227.

Tashman, P., Marano, V., & Babin, J. (2019). Firm-specific assets and the internationalization–performance relationship in the US movie studio industry. International Business Review, 28(4), 785–795.

Thomas, D. E., & Eden, L. (2004). What is the shape of the multinationality-performance relationship? Multinational Business Review, 12(1), 89–110.

Tomàs-Porres, J., Segarra-Blasco, A., & Teruel, M. (2023). Export and variability in the innovative status. Eurasian Business Review, 13(2), 257–279.

Tsionas, E. G. (2002). Stochastic frontier models with random coefficients. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 17(2), 127–147.

Tsionas, M. G., & Tzeremes, N. G. (2022). The degree of internationalization and firm productivity: empirical evidence from large multinationals. British Journal of Management, 33(4), 1969–1990.

Verbeke, A., & Brugman, P. (2009). Triple-testing the quality of multinationality–performance research: An internalization theory perspective. International Business Review, 18(3), 265–275.

Verbeke, A., & Forootan, M. Z. (2012). How good are multinationality–performance (M-P) empirical studies? Global Strategy Journal, 2(4), 332–344.

Woo, L., Assaf, A. G., Josiassen, A., & Kock, F. (2019). Internationalization and hotel performance: Agglomeration-related moderators. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 82, 48–58.

Wu, S., Fan, D., & Chen, L. (2022). Revisiting the internationalization-performance relationship: A twenty-year meta-analysis of emerging market multinationals. Management International Review, 62(2), 203–243.

Xiao, S. S., Lew, Y. K., & Park, B. (2019). 2R-based view on the internationalization of service MNEs from emerging economies: Evidence from China. Management International Review, 59, 643–673.

Zyphur, M. J., & Oswald, F. L. (2015). Bayesian estimation and inference: A user’s guide. Journal of Management, 41(2), 390–420.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arbelo, A., Arbelo-Pérez, M. & Pérez-Gómez, P. Internationalization and individual firm performance: a resource-based view. Eurasian Bus Rev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-024-00276-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-024-00276-5