Abstract

This paper investigates the impact of aligning an innovation strategy with Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices on innovation and non-innovation performance variables. Drawing on principles from Stakeholder Theory and Social Network Theory of Innovation, the research hypothesizes that ESG-driven firms will outperform firms that are not ESG-driven in terms of future innovation outcomes, labor productivity, exporting and survival rates. Using the Technological Innovation Panel (PITEC) database, a panel of Spanish companies, the study compares the performance of two groups of innovative firms: firms that declare that at least one of the ESG goals are relevant for their innovation activities (ESG-driven companies) and matched firms that regard all three ESG goals as not important (non-ESG companies). Our findings reveal that ESG-driven companies exhibit a better future innovation performance and that, in terms of labor productivity, exporting, and survival their performance is never inferior than that of innovative firms that are not ESG-driven.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In 2006, the United Nations (UN) launched the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) to meet the global need for a framework that would encourage institutional investors to voluntarily incorporate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors into their investment decisions and ownership practices. ESG is an abbreviation coined in 2004 in the report “Who cares Wins: Connecting Financial Markets to a Changing World” by 20 financial institutions in response to a request from Kofi Annan, the Secretary-General of the United Nations (Gillan et al., 2021). ESG factors encompass three aspects. First, the “Environmental (E)” factor refers to climate change mitigation and adaptation, and, in turn, to resource use, emissions, recycling, waste management, and greenhouse gas emissions as well as the environment more broadly, for instance, the preservation of biodiversity, pollution prevention and the circular economy. Second, the “Social (S)” factor addresses issues of inequality, inclusiveness, labour relations, investment in people and their skills and communities, as well as workforce treatment, human rights, community interests, and product responsibility, with an emphasis on building trust and loyalty among stakeholders. Third, the “Governance (G)” factor focuses on the governance of public and private institutions - including management structures, employee relations and executive remuneration - and it plays a fundamental role in ensuring the inclusion of social and environmental considerations in the decision-making process and the compliance with best-practice corporate governance principles (European Commission, 2023).

The PRI initiative is supported by an international network of signatories who voluntarily commit to implementing the six PRIs in their investment practices and report on their progress.Footnote 1 While the concept of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) existed at that time, corporate scandals and financial crises, such as those involving Enron and the 2008 financial crisis changed the landscape and increased scrutiny of governance practices as a means to regain stakeholders’ trust. This shift in perspective gave rise to the broader concept of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG), which takes governance practices explicitly into account.Footnote 2 Therefore, ESG is a broader concept and, at the same time, implies a more profound level of integration into business strategy and decision-making processes than CSR.

The notion that companies should address a wide range of ESG issues has gained traction among individuals, businesses, and institutions, as evidenced by the significant increase in signatories to the PRI and the substantial assets under their control. For instance, Gillan et al. (2021) report that more than 3000 institutional investors and service providers have embraced the PRI, with the assets under management for these entities experiencing significant growth, from $6.5 trillion in 2006 to over $86 trillion in 2019. This reflects a growing recognition of the importance of ESG factors in sustainable and responsible business practices that have attracted the attention of investors, corporate managers and also researchers.

As a consequence, the corpus of literature has experienced a continuous and substantial growth over the past decade (Daugaard & Ding, 2022). While the ESG concept is relatively recent, the body of related research is substantial. This is primarily because ESG comprises three distinct aspects (environmental, social, and governance), and many papers that claim to focus on ESG delve into just one or two of these dimensions instead. In this regard, a significant portion of existing studies on this subject assess ESG activities by considering the environmental and social dimensions together, that is, CSR. Hence, since ESG is rooted in CSR, many papers have employed these two terms interchangeably (Garcia et al., 2017; Gillan et al., 2021). Even though this study considers ESG-driven companies, defined as those that regard the three ESG-related goals as relevant in their innovation activities, for the purpose of the literature review of this paper, we analyze the CSR/ESG literature, understanding that CSR emphasizes the environmental and the social aspects and that ESG adds the governance issues.

The main focus of prior CSR/ESG research has encompassed five key areas: (1) exploring the correlation between market characteristics, including country, state, and industry, and the implementation of CSR/ESG practices (Liang & Renneboog, 2017; Jha & Cox, 2015; Borghesi et al., 2014; 2) examining the relationship between firm management attributes, such as board composition, executive profiles, compensation structures, and internal governance, and the adoption of CSR/ESG initiatives (Bénabou & Tirole, 2010; Cronqvist & Yu, 2017; McCarthy et al., 2017; 3) investigating the associations between various ownership structures, including institutional, family, and state ownership, and CSR/ESG activities (Hoepner et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2020; Abeysekera & Fernando, 2020; Boubakri et al., 2019; 4) assessing the influence of CSR/ESG actions on firm risk, encompassing aspects such as cost of capital, systemic risk, credit risk, and legal risk (Lins et al., 2017; Albuquerque et al., 2019; Hoepner et al., 2023), and (5) scrutinizing the connection between CSR/ESG practices on the one hand, and firm value and performance on the other (Fatemi et al., 2015; Friede et al., 2015; Buchanan et al., 2018).

The purpose of this paper is to contribute to the fifth line of research analyzing how the incorporation of environmental, social, and governance practices into a company’s innovation strategy affects its future innovation outcomes and performance indicators.Footnote 3 Following Gillan et al. (2021) and Galbreath (2013), the impact of management decisions regarding ESG dimensions on firm performance is one of the most contentious inquiries within the extensive body of literature on ESG/CSR. In light of the substantial investments made in these initiatives, a fundamental question arises on whether ESG-driven efforts pay off in terms of better performance.Footnote 4 In this line, a number of empirical studies have analyzed the relationship between ESG and Future Financial Performance (FINP). Even though most of these studies found a positive relationship between ESG-driven firms and future firm performance (Allouche & Laroche, 2005; Ambec & Lanoie, 2008; Griffin & Mahon, 1997), there are also contradictory findings (Friedman, 1970) and non-significant results in other studies (Margolis & Walsh, 2003; Orlitzky et al., 2003). Consequently, whether and how ESG actions influence future financial performance is still a source of disagreement and debate among researchers and managers (Lu et al., 2014; Wang & Sarkis, 2017).

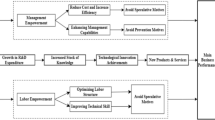

By analyzing a number of non-financial performance indicators, this paper contributes to the academic debate and complements existing studies. Specifically, this is done by estimating the difference in performance between companies that emphasizes ESG goals on their innovation strategies and companies that do not in terms of innovation outputs (probability of introducing new products, new processes, and products new to the market, as well as percentage of sales derived from new products) and in terms of labor productivity, exporting status and likelihood of firm survival. These performance dimensions play a critical role in enabling firms to sustain a competitive advantage. For all these reasons, we hypothesize that ESG-driven firms are more innovative in the future, present a greater labor productivity, are more export-oriented and, are more likely to survive than comparable non-ESG firms.

From the methodological point of view, this paper uses the data from the Technological Innovation Panel (PITEC database), which is a yearly survey from the Spanish National Statistical Institute. This dataset provides detailed information on innovation inputs and outputs of a panel of Spanish firms as well as some information on firm characteristics. Using information on stated innovation goals, innovative firms can be classified into two broad categories as to the orientation of their innovation goals: ESG-driven firms and non-ESG firms. The former group includes companies that regard at least one of the three ESG goals (environmental, social, and/or governance) as relevant in their innovation activities. The latter group includes firms that regard none of the three cited ESG goals as relevant for innovation. We employ two different thresholds in the declared importance of innovation goals to classify innovative firms into these two groups, as explained later. Within the group of ESG-driven firms, we may consider different subclassifications, such as firms that regard environmental goals (and possibly social and governance goals) as relevant, firms that regard social (and possibly environmental and governance goals as relevant), firms that regard governance goals (and possibly environmental and social goals) as relevant, and firms that regard all three ESG goals as relevant. In our empirical analysis, we compare future innovation and non-innovation performance of different subgroups within ESG-driven firms on one hand, and non-ESG driven firms on the other.

To control for the non-random nature of ESG-driven strategies and to address the concern regarding the possibility that better-performing firms are precisely the ones adopting ESG-driven innovation strategies, this paper uses matching to create a balanced sample of control firms, based on pre-treatment observed firm characteristics. By balancing covariates between treatment and control groups, it becomes more plausible to infer a causal relationship between the treatment and the outcomes. We find robust evidence on the positive relationship between adopting an ESG-driven innovation strategy and having a better future innovation performance. We also find evidence suggesting that ESG-driven firms enjoy a never reduced future labor productivity, present a better exporting performance, and are more likely to survive, although this evidence is less robust to changes in the classification criterion and estimation method.

From the theoretical point of view, this study has two main contributions. First, its results contribute to support the Stakeholder Theory, in the sense that shows that by prioritizing stakeholder interests and aligning them with ESG actions, companies can enhance their innovation outcomes and improve important performance metrics. Although the majority of studies are in line with the stakeholder perspective, establishing a positive link between ESG-driven firms and future firm performance, there are also conflicting findings supporting Agency Theory and non-significant outcomes in other research. Consequently, the influence of ESG initiatives on future firm performance remains a contentious subject of debate to which this paper contributes. Second, it establishes a link between the Social Network Theory of Innovation and the Stakeholder Theory. As previously stated, the Stakeholder Theory posits that taking into account a wider range of stakeholders interests will help the company to better address their concerns and survive in the future. This paper relates this argument with the innovation literature focused on the analysis of the external sources to innovate, in particular, with the Social Network Theory of Innovation. This theory states that innovation is the result of a networked and collaborative process, where the flow of information and knowledge among interconnected actors drives the creation and diffusion of new ideas and technologies. Therefore, this paper relies on the Social Network Theory of Innovation to give support to the Stakeholder theory: ESG-driven companies are characterized because they proactively engage with stakeholders, seek their input and feedback, respond to their concerns and build trust through transparent communication. This continuous engagement with stakeholders generates a competitive advantage, called social capital, that contributes to a better innovation and firm performance.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 presents and develops the hypotheses, Sect. 3 presents the data and methodology. Section 4 discusses the results and Sect. 5 offers some concluding remarks. Results from robustness checks are presented in the Appendix.

2 Hypotheses development

CSR is commonly understood as “the commitment of businesses to contribute to sustainable economic development by working with employees, their families, the local community and society at large to improve their quality of life” (World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 1999). Broadly speaking, CSR actions primarily emphasize a company’s responsibility to give back to society and engage in ethical activities designed to fulfill immediate social or environmental needs. These actions are not always integrated into a company’s overall strategy and, often, are managed as standalone initiatives. Then, CSR requires a low level of integration in the business strategy. Moreover, by focusing on environmental and social aspects, CSR may be regarded as a subset of ESG. Conversely, ESG refers to how corporations and investors integrate environmental, social and governance concerns into their business models with the objective of creating sustainable value for all stakeholders (Gillan et al., 2021). Given the long-term focus of ESG actions, they become integral components of the company’s core business strategy and decision-making processes. As a result, companies embracing ESG principles incorporate these factors into their strategic decisions and risk management. Thus, CSR and ESG fundamentally differ in scope and the level of integration within the company strategy. However, despite these differences, previous research has used these terms interchangeably (Garcia et al., 2017; Gillan et al., 2021).

The existing literature has approached CSR/ESG-related issues through two main theoretical frameworks: the Agency Theory and the Stakeholder Theory. From the perspective of the Agency Theory, integrating environmental, social and/or governance actions on companies’ strategies are the result of agency problems that drag wealth creation. This relies on Friedman’s argument that managers should solely focus on maximizing firm profits and fulfilling the main goals of shareholders (Friedman, 1970) and not the ones of the different stakeholders. From this perspective, allocating corporate resources in CSR/ESG initiatives is seen as detrimental to shareholder value and profit maximization, essentially seen as a cost rather than an investment. Several studies support this view, suggesting that managers who take part in CSR/ESG-related activities benefit themselves at the expense of reducing value for shareholders (Bénabou & Tirole, 2010; Masulis & Reza, 2015; Brown et al., 2006) and that managers that invest in social activities prioritize their personal reputation over the company profits (Barnea & Rubin, 2010). Summarizing, according to the Agency Theory, CSR/ESG activities are not aligned with shareholders’ interests because they are an investment that does not pay off and, in turn, decrease the value created.

In contrast to the Agency Theory, the Stakeholder Theory (Freeman, 1984), argues that managers should be accountable to all stakeholders, not just shareholders. According to this perspective, managers “must pay attention to any group or individual, who can affect or is affected by the organization’s purpose, because that group can hinder [the firm’s] accomplishments” (Freeman 1984, p. 52). The effective incorporation of these diverse interests is crucial for managers to navigate the stakeholder landscape and develop a comprehensive understanding of their genuine concerns (Bhattacharya et al., 2008; Brower & Mahajan, 2013). Following this theoretical framework, even though CSR/ESG activities may reduce short-term earnings, they do not sacrifice corporate long-term value. Indeed, they maximize the long-term welfare of shareholders, protecting the interests of all stakeholders in terms of ESG factors (Peng & Isa, 2020). Therefore, the Stakeholder Theory claims that managers must always consider the impact of business decisions on the environment, society and corporate governance to be able to generate a sustainable management strategy that maximizes the long-term value for all stakeholders.

Regarding the empirical evidence of the relationship between CSR/ESG and performance, a large number of studies provide support for the Stakeholder Theory showing a positive direct relationship between CSR/ESG activities and financial performance. Specifically, following the systematic review of Van Beurden and Gössling (2008), 68% of the contributions surveyed show a significant positive relationship between Corporate Social Performance (CSP) and Corporate Financial Performance (CFP), the 26% found no significant relationship and the remaining 6% found a significant negative relationship. For example, among the studies that show a positive impact, Orlitzky et al. (2003) perform a meta-analysis review of 52 studies generating a total sample size of 33,878 observations to analyze whether there is a relationship between Corporate Social Performance (CSP) and Corporate Financial Performance (CFP). Their results show that there is a positive relationship with a high degree of certainty between the two variables, both across industries and across study contexts. In an attempt to update the meta-analytic review, Allouche and Laroche (2005), conducted the analysis of 82 published studies that refer not only to the US but also to the UK. Again, the results are consistent with Corporate Social Performance (CSP) having a positive impact on Corporate Financial Performance (CFP) and this is stronger in the UK context. In the same line, Shen and Chang (2009) studied the difference in financial performance between companies that invest in CSR and companies that do not, based on Taiwanese data from 2005 to 2006. They explicitly take into consideration non-random adoption of CSR practices. Although the four matching methods used provide marginally different results, they conclude that companies involved in CSR practices usually obtain significantly higher values on pretax income to net sales and profit margin. Gillan et al. (2010), using the ESG scores from the Kinder-Lydenberg-Domini (KLD) database during the period 1992–2007, found that companies with stronger ESG performance have an increased operating performance, efficiency and firm value than the others. According to Ameer and Othman (2012), who analyzed data from 100 sustainable global companies in 2008, these companies exhibited a higher average sales growth, return on assets, pre-tax profits, and cash flows from operations. Furthermore, this enhanced financial performance not only increased but also remained consistent throughout the sample period. Also, Eccles et al. (2014) analyzing a sample of 180 U.S. companies and employing propensity score matching found that firms that had adopted sustainable policies by 1993 had a stronger stock market and accounting performance in 2009 than their non-adopting counterparts. Flammer (2015) using a sample of U.S. public trade companies during the period 1997–2002, showed, by means of a regression discontinuity design, that companies that adopt CSR proposals increase the shareholder value by 1.77% and also achieve a superior accounting performance.

However, there are also papers that found a negative relationship. For instance, Di Giuli and Kostovetsky (2014), in their analysis of the relationship between changes in a firm’s ESG/CSR scores and its revenue growth over three years, discovered that when companies extend their ESG/CSR policies, the eventual outcome is a future stock underperformance and a long-term decline in ROA. Similarly, Masulis and Reza (2015) found that the stock market responded negatively to the announcement of corporate philanthropic contributions, implying that investors did not place a high value on this type of ESG/CSR activity. Furthermore, Servaes and Tamayo (2013) determined that the correlation between ESG/CSR and firm value is dependent on the extent of advertising. They found that among companies that do not advertise, ESG/CSR investments either have a detrimental impact or show no connection to firm value. Finally, there are papers that show a non-significant relationship. For instance, Hsu et al. (2018), who analyzed state-owned firms, concluded that environmental choices are not significantly linked to shareholder value in terms of Tobin’s q or long-term profitability. In the same line, Humphrey et al. (2012), who examined CSP ratings for firms in the UK, found no variations in the risk-adjusted performance of UK firms with high or low CSP ratings. They concluded that CSR does not have a positive impact in terms of risk or return.

Given these heterogeneous results, a gap in the literature still remains, calling for a deeper inquiry into the influence of CSR/ESG practices on firm performance through its indirect effect on firm innovation capacity (Bocquet et al., 2013; Costa et al., 2015; Hull & Rothenberg, 2008; Lioui & Sharma, 2012; McWilliams & Siegel, 2000). As Galbreath (2013) states, given the challenges associated with determining the financial benefits of ESG investments in the short and/or long-term (Dyllick & Hockerts, 2002; Hahn et al., 2010), areas of research beyond ESG’s direct link to financial returns are needed.

Following this argument, we believe that it is important to analyze several other variables related to firm performance that may be influenced by the ESG orientation of firm’s innovation strategies. Hence, this paper investigates the differences between ESG-driven and non-ESG firms in terms of the probability of introducing new products and/or processes, as well as the percentage of sales derived from new products. Furthermore, we explore whether the adoption of ESG-driven innovation strategies improves labor productivity and determine if these companies are more active in foreign markets than comparable non-ESG firms. Finally, as these performance dimensions play a critical role in enabling firms to sustain a competitive advantage, this paper also analyzes the difference between ESG-driven and non-ESG firms in terms of firm survival.

2.1 ESG-driven strategy and innovation performance

Innovative firms used to rely mostly on internal sources of knowledge to innovate, such as R &D activities conducted by existing departments, innovative practices within the organization, educational events and employee-driven initiatives. According to the Closed Innovation paradigm, firms were responsible for the entire innovation process - from idea generation to financing and support- operating under the self-reliant principle: “If you want something done right, you have got to do it yourself” (Chesbrough 2003, p. 33). However, in today’s business landscape characterized by rapidly decreasing time to market, shorter product life-cycle and the growing expertise of customers, (Bidault & Cummings, 1994; DeBresson & Amesse, 1991), companies overly focused on internal research run the risk of missing numerous opportunities. Many of these opportunities lie beyond the company’s existing business scope or require collaboration with external technologies to unlock their potential (Chesbrough, 2003). As a result, the ability to exploit external knowledge has become a critical component of innovative performance (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990).

This shift in the business landscape has prompted a substantial body of literature that examined the relationship between internal and external R &D strategies. At the core of this literature is the debate on the complementarity or substitutability between internal and external R &D strategies for managing innovation, a discourse accompanied by mixed empirical evidence. On one hand, there are studies that have demonstrated that internal R &D and external technology sourcing are complementary innovation activities (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Rigby & Zook, 2002; Cassiman & Veugelers, 2006; Lokshin et al., 2008; Rothaermel & Hess, 2007; Schmiedeberg, 2008). On the other hand, there are also papers that have found substitutability (or no complementarity) between internal and external sources of innovation (Hess & Rothaermel, 2011; Laursen & Salter, 2006; Vega-Jurado et al., 2009). In an attempt to explain the different previous results, Hagedoorn and Wang (2012) argue that internal R &D and external R &D are complements or substitutes depending on the level of in-house R &D: substitutes for low levels of internal R &D, and complements for high levels of internal R &D. Additionally, from a methodological perspective, Piga and Vivarelli (2003) emphasize the significance of addressing selectivity bias: the decision to cooperate in R &D is contingent on the prior internal decision to undertake R &D and, hence, is not appropriate to use a single equation framework.

Without delving into the complementarity-substitution effect, other researchers highlighted the benefits of using diverse knowledge sources to innovate. Specifically, Cohen and Levinthal (1990) demonstrated that the innovative process is facilitated by knowledge diversity, allowing individuals to form novel associations and linkages; Kogut and Zander (1992) argued that increased diversity in complementary knowledge sources enhances the probability of successful innovation, emphasizing that innovation often stems from knowledge recombination; Baldwin and Clark (2000), Baldwin and Clark (2006) highlight the benefits of conducting multiple parallel searches in innovation; Amara and Landry (2005) found that firms introducing innovations with a greater degree of novelty are more likely to use a wider range of information sources to develop or improve their products and Leiponen and Helfat (2010) emphasizes that accessing a greater number of knowledge sources improves the likelihood of obtaining valuable innovation outcomes, particularly with regard to the “value” of newly commercialized innovations in terms of sales revenues.

The simultaneous pursuit of internal and external R &D strategies has been termed by Chesbrough (2003) as “Open Innovation”. Embraced by an increasing number of firms in recent decades, Open Innovation involves integrating external sources into the firm’s innovation processes and competitive strategy (Chesbrough, 2003). Successful open innovators effectively commercialize external ideas by utilizing both external and in-house pathways to navigate the market (Chesbrough, 2003). This transformative process challenges the traditional firm boundaries, making the firm more porous and embedded in loosely coupled networks comprising various actors that, both collectively and individually, collaborate towards a shared goal.

The emphasis on openness and interaction in innovation research aligns with a broader exploration of the relationship between collaboration/cooperation and innovation. This alignment is supported by various studies across different sectors. For instance, Shan et al. (1994) noted a correlation between cooperation and innovative output in biotechnology start-up firms; Powell et al. (1996) found that biotech firms engaged in cooperative networks exhibited superior innovative performance; Ahuja (2000), in an analysis of inter-firm collaboration linkages, found that both indirect and direct ties influence a firm’s ability to innovate, with the effectiveness of indirect ties moderated by the number of the firm’s direct ties. Moreover, Becker and Dietz (2004) asserted that engaging in R &D cooperation with various partners increases the likelihood of innovation; Bullinger et al. (2004) found that collaboration with universities, research institutes, suppliers, customers, and other actors played a valuable role in the process of knowledge and innovation creation; Liefner et al. (2006) discovered that collaborating with foreign companies facilitated the acquisition of new ideas and entry into the market with innovative products, while cooperation with universities was primarily employed for the design of new products and Nieto and Santamaría (2007) concluded that collaborative networks involving diverse partner types exert the most significant influence on the level of innovation novelty.

These more recent models of open innovation emphasize the interactive nature of the innovation process and highlight the importance of the breadth of information sources utilized by firms (Von Hippel, 1976; Leiponen, 2000, 2002; Rosenkopf & Nerkar, 2001; Veugelers & Cassiman, 1999). For instance, Katila and Ahuja (2002) argued that a firm’s innovative performance is determined by the independent and interactive effects of search depth -how the firm reuses its existing knowledge- and search scope -how widely the firm explores new knowledge- and Laursen and Salter (2006) found that companies exhibiting a broad external search -defined by the number of external sources or search channels- and a deep external search -defined by the extent to which firms draw deeply from the different external sources or search processes- tend to be more innovative. Nevertheless, given that innovation search and cooperation can be time-consuming, costly and labor-intensive (Kaiser, 2002), there is a threshold beyond which additional exploration of innovation sources becomes less productive, and the advantages of openness start yielding decreasing returns (Katila & Ahuja, 2002; Laursen & Salter, 2006).

To gain a profound understanding of knowledge exchange and the promotion of collaboration, the concept of networks has gained prominence in the innovation literature. In this regard, the network theories of innovation have evolved from more restricted networks with clients, suppliers and research partners to consider a broader range of institutional and social actors as sources of information (Nelson, 1993; Edquist, 1997; Edquist & Hommen, 1999; Lundvall, 2016). Specifically, the theories of social networks in innovation posit that innovation stems from research and dynamic interactions among firms and various actors, with a pivotal role assigned to the knowledge possessed by each network member, which is contextually connected to the environment and its participants (Amara & Landry, 2005). Possessing contextualized knowledge ensures that individual actors contribute to enhancing various facets of a firm’s absorptive capacity, thereby increasing the benefits of cooperation (Mendi et al., 2020). Simultaneously, this approach reduces the likelihood of considering excessive actors that exhibit diminishing returns. In that sense, the social network theories of innovation lay more emphasis on the strategic importance of relational rather than technical tools and assume that the creation of competitive advantages rest on the social capital generated. Even though social capital can take different forms, in innovation literature it specifically refers to trust, which is developed over time through repeated interaction, and through the breadth of the network.

Some earlier contributions have asserted a positive relationship between ESG/CSR and innovation outcomes, yet none of them has evaluated this connection through the lens of the Social Network Theory of innovation. For instance, Porter and Kramer (2006) or Kramer and Porter (2011) argue that engaging in CSR is an important source of innovation because it implies a social process whose result is a share-value creation. Also, Hull and Rothenberg (2008) present evidence that the firm’s involvement in CSR practices positively influence the company’s performance through the adoption of innovation related processes. This is supported also by Bocquet et al. (2013), who find that firms engaging in CSR activities are more likely to be innovative in terms of their processes and generation of products. Reverte et al. (2016) presented evidence demonstrating that adopted CSR policies directly impact the firm performance and innovation capacity of 133 eco-responsible Spanish firms. Similarly, Ueki et al. (2016) utilized questionnaire survey data from Thai trucking firms and provided empirical evidence of a significant positive effect of firms’ CSR activities on innovation.

At the same time, ESG-driven companies are characterized by their commitment to ethical, sustainable, and responsible business practices regarding the environment, society and governance. Following the Stakeholder theory, these companies consider the interests of all stakeholders and this external engagement allows the firm to expand its innovation-related knowledge and improve its absorptive capacity, encouraging higher levels of innovation activity (McWilliams & Siegel, 2000). That is, while internal stakeholders facilitate the combination of knowledge and capabilities within the firm, maintaining good relations with external stakeholders enables the firm to have access to diverse and contextualized external knowledge and information (Choi & Wang, 2009). Greater absorptive capacity and access to diverse expert sources of information for innovation enhance the firms’ innovation capabilities and thus increase the probability of sustaining innovation in the future.

Linking the Stakeholder Theory—which asserts that managers should be accountable to a wider set of stakeholders- to the Social Network Theory –which states that operating within networks increase the firm’s ability to identify and generate innovation opportunities that could not be identified otherwise (Raab, 2019; Burt, 2000)-, this paper considers that ESG-driven companies are in a better place to identify and respond to strategic opportunities and challenges through continuous evaluation stakeholder relationships (Driessen & Hillebrand, 2013; Vilanova et al., 2009), and that the more constant and intense the relationships are, the more likely the information will be used to develop innovations (Amara & Landry, 2005). With a superior position in these two dimensions -increased awareness and capability to implement more innovation opportunities-, ESG-driven firms gain a comparative advantage in innovation over non-ESG counterparts. Consequently, this advantage is expected to result in a superior future innovation performance for ESG-driven innovative firms compared to their non-ESG counterparts.

Drawing on these arguments, the first hypothesis suggests that ESG-driven companies, by considering a broader set of stakeholders, are better positioned to sustain future innovation compared to non-ESG driven companies. As a result, this advantageous positioning (social capital) leads to higher levels of innovation outputs.

Hypothesis 1

ESG-driven companies present better future innovative performance than non-ESG companies.

2.2 ESG-driven strategy and labor productivity

As previously mentioned, ESG-driven companies distinguish themselves by their commitment to addressing the diverse needs of a broad spectrum of stakeholders, which may encompass employees, suppliers, customers, competitors, shareholders, and communities, among others. The effectiveness of meeting these varied stakeholder needs relies on the managerial capacity to comprehend the complex stakeholder landscape and integrate these multifaceted external interests into the corporate strategy (Costa et al., 2015). Analyzing the distinct needs of this network of stakeholders, who possess contextualized knowledge, and engaging in interactions with them, provides managers with valuable social capital for the development of new products and processes, or enhancements of existing ones.

Labor productivity is a crucial indicator of a firm’s efficiency and effectiveness in employing its human resources to produce goods or services. A higher labor productivity means that the firm produces more output or generates more value per unit of labor input (Samuelson & Nordhaus, 1989). In the context of ESG-driven companies, the consideration of diverse and contextualized knowledge, combined with a commitment to being accountable to various stakeholders, leads to the adoption of innovations in the value chain of the firm (Drempetic et al., 2020). The value chain includes all the activities and processes that a company undertakes from the initial stages of product or service development to its delivery to customers. Consequently, integrating ESG considerations into the value chain becomes a pivotal strategy for promoting responsible and sustainable business practices (Porter & Kramer, 2006). A closer examination of the discrete actions associated with each of the three ESG dimensions enables us to discern their impact on the value chain.Footnote 5.

First, the implementation of environmental actions generates cost reduction and resource optimization. Companies that apply actions such as waste reduction, resource conservation and energy efficiency can reduce production costs and optimize the resource utilization. These companies display a strong sustainability proposition on plastics and packaging, are more water-efficient and have a lower unit-cost structure (Derwall et al., 2005).

Second, the implementation of social actions positively impacts the work environment, leading to increased employee motivation, commitment, engagement and productivity. Moreover, ESG-driven companies that foster a positive workplace culture attract millennials who are seeking purposeful job opportunities, improving talent retention and productivity in the workplace (Greening & Turban, 2000).

Finally, the implementation of governance actions improves accountability, transparency and risk management. ESG-driven companies prioritize stakeholder interests and proactively address potential risk associated with their operations with the objective to maintain an enhanced reputation and brand image. ESG goals, therefore, may represent an added incentive to achieve a better performance. This proactive risk management approach reduces the likelihood of adverse, punitive regulatory outcomes (Ansari et al., 2013) and avoid costly complications and interferences to their daily operations that could result in a reputational damage. Additionally, the greater accountability of ESG-driven companies encourages them to optimize investments and the use of resources, including labor, resulting in a better financial performance (Fatemi et al., 2015; Ioannou & Serafeim, 2010).

Overall, companies that regard ESG goals as relevant, taking into consideration a wider array of stakeholders and harnessing the contextualized knowledge within their networks, are likely to implement environmental, social, and governance practices that result in increased labor productivity. Moreover, these improvements in productivity are likely to be long-lasting, since they involve profound changes in the productive structure of the firm, as argued in the previous paragraphs. Therefore, the second hypothesis once again bridges the principles of the Stakeholder Theory, which advocates that companies bear the responsibility of considering the concerns and well-being of all parties impacted by their operations, with the Social Network Theory of Innovation. The latter theory asserts that interactions within a network lead to the creation of social capital, which, in this specific context, translates into increased innovation, operationalized through the adoption of environmental, social, and governance practices. Hence, the second hypothesis argues that innovative companies that are ESG-driven, present higher labor productivity than innovative firms that are not ESG-driven.

Hypothesis 2

ESG-driven companies have higher future labor productivity compared with non-ESG driven companies.

2.3 ESG-driven strategy and internationalization

Cassiman and Golovko (2011) and Cho and Pucik (2005) show that the critical drivers of national competitiveness are innovation and internationalization. We already argued that ESG fosters innovation through the explicit consideration of the stakeholders’ interests, and we focus now on the internationalization part. In particular, we argue that the consequences of adopting an ESG-driven innovation strategy include a higher probability of exporting in the future.

First, ESG-driven companies show a higher degree of innovation persistence and adaptability compared with their peers. Their emphasis on prioritizing stakeholder interests and cultivating social capital within their network enables them to remain vigilant to environmental shifts impacting their stakeholders. Leveraging their context-sensitive knowledge, these companies can swiftly customize and fine-tune their products or services to align with specific market conditions. This adaptability significantly enhances the likelihood of succeeding in foreign markets. Previous research has shown a positive relationship between innovation and export performance, indicating that more innovative firms tend to perform better internationally (Golovko & Valentini, 2011). Given the greater innovation showed by ESG-driven companies, we can expect them to achieve greater success in foreign markets.

Second, ESG-companies, driven by sustainability, ethical practices and social responsibility, enjoy a positive corporate reputation and a strong brand image (Gupta, 2002). This positive perception attracts customers, investors and other stakeholders, leading to increased market share and customer loyalty (Albuquerque et al., 2019). Stakeholders, including consumers, employees, and investors, prefer transparent firms, especially as economies move to more responsible accounting to mitigate ESG risks and avoid costly penalties (Eccles et al., 2014). A company’s ESG reputation holds significant importance for its status, fundraising efforts, and consequently, its ability to withstand competitive pressures and ensure survival in the market. (Brown & Dacin, 1997; Cornell & Shapiro, 1987; Hammond & Slocum, 1996)

Third, ESG-driven companies may benefit from improved access to capital and lower cost of capital due to their positive reputation. Investors and value chain partners increasingly seek companies with strong ESG performance. In consequence, ESG-driven companies may find it easier to access funding, obtain advantageous loan terms, and benefit from lower borrowing costs. Helm (2007) claims that a company with a good reputation is perceived to be “less risky than companies with equivalent financial performance, but with a less well-established reputation.” ESG activities foster trust between investors and managers (In et al., 2014) and reduce the level of information asymmetry and adverse selection costs associated with equity raising. Moreover, companies with high ESG performance tend to receive greater coverage from the media and attract socially conscious investors (Becker-Olsen et al., 2006; Hong & Kacperczyk, 2009; Hung et al., 2018).

Consequently, ESG-oriented companies, given their broader stakeholder perspective and the internalization of contextual knowledge into companies’ strategies, exhibit superior capabilities to consistently sustain innovation and to adapt to changing circumstances. Furthermore, their adoption of sustainable societal and ethical practices typically results in a stronger reputation and brand image, which, in turn, facilitates easier access to capital. These factors provide them with a sustained competitive advantage in domestic markets that may contribute to their success in future international business endeavors. Therefore, the third hypothesis states:

Hypothesis 3

ESG-driven companies present higher probability of exporting in the future compared with non-ESG driven companies.

2.4 ESG-driven strategy and survival

ESG-driven companies take into account not just the interests of shareholders but also the issues related to the other stakeholders that influence or are influenced by the company. The Stakeholder Theory suggests the creation of a more balanced and sustainable approach to corporate decision-making, ultimately leading to long-term success, by fostering positive relationships and responsible business practices with a wider range of stakeholders (Freeman, 1984). Following the Social Network Theory of Innovation, knowledge is immersed in networks and is the result of relationships among their members (Acs, 2000). It anticipates that the greater the stability and intensity of relationships, the higher the likelihood that the information will be leveraged to create truly innovative developments (Amara & Landry, 2005). Basically, this happen because operating within networks develops social capital that, in the innovation context, refers to trust and the breadth of the network. Social capital contributes to reduce transaction costs between firms and other actors, notable search and information costs, bargaining and decision costs, policing and enforcement costs (Maskell, 1998).

Moreover, participating in networks enhances a firm’s capacity to recognize and generate innovative opportunities that might otherwise go unnoticed (Raab, 2019; Burt, 2000). Therefore, a superior innovation performance and the consequences of social capital represent a structural change in the firm that supports a sustainable competitive advantage. The concept of competitive advantage (Porter, 1980) refers to the unique resources, capabilities, qualities or strategic positioning that enables companies to outperform its competitors in the marketplace. Attaining a competitive advantage is extremely important for companies, as previous research has shown its positive association with several desirable outcomes. These outcomes includes market leadership and a important market share (Porter, 1985), high profitability as consequence of increased revenues and superior profit margins (Porter, 1985); increased customer satisfaction and loyalty (Prahalad & Hamel, 1990), robust business growth as a consequence of attracting new customers, expanding into new markets or introducing new products or services (Rumelt, 2012); a strong brand reputation associated with positive qualities such as quality, reliability, innovation or customer-centricity (Aaker, 2012); generation of important barriers to entry for new competitors (Porter, 1980) and the ability to attract top talent and retaining skilled employees (Cappelli, 2009).

Hence, we anticipate that by considering a more extensive array of stakeholders and engaging in a network that cultivates social capital, companies can develop a sustained competitive advantage that positively influences their long-term viability when compared to innovative firms that are not ESG-driven. Therefore, our final hypothesis posits a direct relationship between ESG-driven companies and their ability to endure over the long-term, attributable to their sustainable competitive edge, in contrast to the non-ESG driven counterparts. In particular,

Hypothesis 4

ESG-driven companies present a higher future rate of survival compared with non-ESG companies.

3 Data, methodology and variables

3.1 Data

The empirical analysis carried out in this paper uses firm-level data from the Technological Innovation Panel (PITEC) database. This is a panel of Spanish firms surveyed yearly by the Spanish National Statistical Institute (INE). The PITEC project was initiated in 2003, and the sample at that time included firms with internal R &D expenditures, as well as large firms. In 2004 and 2005, more firms, specifically small firms and firms with positive external R &D expenditures were introduced. During the 2005–2013 period, the sample of firms was quite stable. However, from 2014 onward, annual surveys were conducted for only a portion of the firms within the panel, which prevents the researcher from tracking all the firms that were included in the 2005 survey. Consequently, this paper concentrates on utilizing all the available data from the 2005–2013 period.

The questionnaire extends the Community Innovation Survey (CIS), based on the Oslo Manual, and which has been used not only within the European Union but in an increasing number of countries outside the EU. Given that the Spanish questionnaire provides more information than the CIS, and its longitudinal nature, the PITEC panel has attracted the interest of numerous researchers who have previously analyzed this database, addressing different research questions, see for example Barge-Gil (2010), García-Vega and Huergo (2021), Armand and Mendi (2018), or Mendi (2023), to cite a few. As in similar CIS-based questionnaires, some of the questions refer to the three-year period that includes the survey year, whereas other questions refer to the survey year. In particular, information on innovation outcomes, innovation obstacles, and innovation goals, refer to the three-year period that includes the survey year. For instance, in the 2013 wave, questions on innovation outcomes refer to the 2011–2013 period. In contrast, questions on innovation expenditures, for instance, investments in internal R &D, external R &D, or licensing, refer to the survey year.

Within the PITEC database, this paper focuses on questions in section 6.2 entitled ’Innovation Objectives’ which states: “The innovative activities carried out in your company may have been oriented towards different objectives. Indicate the level of importance (high, intermediate, low, or not important at all) of the following objectives”: 1. Reduced environmental impact (Environmental proxy), 2. Improvement of employee health and safety (Social proxy), and 3. Compliance with environmental, health, or safety regulatory requirements (Governance proxy).Footnote 6 Only innovative firms, that is, those firms that introduced a new product and/or a new process and/or had some ongoing or abandoned innovation in the three years up to the survey year are requested to answer this set of questions. The information on these questions allows us to classify innovative firms into two groups, according to the orientation of their innovation efforts in a given three-year period: non-ESG firms and ESG-driven firms. We have employed two distinct classification criteria to distinguish between non-ESG and ESG-driven firms. Under the first criterion, a non-ESG firm is an innovative firm that declares that none of the three ESG goals has a medium or high importance. Under the second criterion, a non-ESG firm is that which declares that none of the three ESG goals has a high importance. In our empirical analysis, the control group will be drawn from firms that are classified as non-ESG. An ESG-driven firm is one that declares at least one of the ESG goals to have high or medium importance (first criterion), or one that declares at least one of the ESG goals to have high importance (second criterion). In Sect. 4, within the group of ESG-driven firms, we will implement separate analyses for firms that declare environmental, social, governance, or all three ESG-factors to be relevant, always in comparison to non-ESG firms.

3.2 Methodology

This paper estimates the effect of firms adopting a ESG-innovation strategy on a number of performance variables related to the hypotheses laid out in Sect. 2. There are two important issues that condition our empirical analysis. First, our treatment variables -the orientation of firms’ innovation strategies- and most of our outcome variables refer to the three-year period that ends in the survey year. Therefore, if we want to avoid overlap between treatment and outcome and given that both treatment and outcome refer to three-year periods, we must use data from 6 years to conduct a cross-sectional analysis. Second, firms choose the direction of their innovation activities, and in particular, ESG orientation is non-random, depending on the firm’s specific characteristics. Indeed, the adoption of ESG-oriented innovation strategies is not a consequence of, say, a legal change that affects some firms and does not affect some other firms -a natural setting to adopt a difference-in-differences strategy. Instead, it is a deliberate strategic choice made by the firms themselves. This suggests the use of matching to estimate the effect of the orientation of the firm’s innovation orientation. Hence, as in García-Vega and Huergo (2021) we use matching in order to compare treated firms -those that declare an ESG-driven innovation strategy- with similar control firms that are also innovative, but not ESG-driven. The specific ESG treatments that we consider are, in turn: (1) innovation strategies where environmental goals (and possibly social and governance goals) are relevant; (2) innovation strategies where social goals (and possibly environmental and governance goals) are relevant; (3) innovation strategies where governance goals (and possibly environmental and social goals) are relevant; and (4) innovation strategies where all three ESG goals are relevant. As mentioned above, matched control observations are in all cases drawn from the group of non-ESG firms, that is, the subsample of innovative firms that declare, in the treatment period, none of the three ESG factors to be relevant.

By using matching, we compare each observation in the treatment group, firms that implement one of the listed four ESG-driven innovation strategies, with an observation in the control group, that is, firms that are innovative but not ESG-driven. This way, the average difference may be interpreted as the average treatment effect on the treated. Regarding the temporal dimension of our study, out treatment period includes 3 years, since innovative firms report the orientation of their innovation activities during the three years up to the survey period. Meanwhile, matching is based on the values of observable variables prior to treatment, and performance is observed after treatment. Since we have data for the 2005–2013 period, this means that the earliest treatment period is 2006–2008, to allow for the observation of matching variables pre-treatment, and the latest treatment period is 2008–2010, so as to avoid overlap between treatment and performance variables such as innovativeness, which report performance for the three years up to the survey year. Taking into consideration this feature of our data, we will conduct separate analyses considering 2006–2008 and 2008–2010 as the treatment periods, respectively.

There are different procedures to construct the matched sample. Following García-Vega and Huergo (2021) and Heijs et al. (2022), we use propensity score matching to construct our matched sample. Appendix A includes tests of the adequacy of the matching procedure. We use the Stata command kmatch (Jann, 2017) to implement propensity score matching. In all the specifications, kernel bandwidth has been selected using cross-validation and standard errors have been obtained by 50 bootstrap repetitions.

3.3 Variables

Table 1 displays the definitions of the outcome and selection variables used in this paper. First, this paper considers two categories of performance variables: innovation-related and other performance variables. In the innovation category, this paper employs five different innovation proxies that were previously used in the literature to capture innovation results (Mairesse & Mohnen, 2010; García-Vega & Huergo, 2021). Specifically, this paper utilizes a binary variable labeled “innovative” (INNOVATIVE), which takes the value one if the firm reported introducing a product or a process innovation and/or had ongoing innovation within the last two years, zero otherwise. This variable is a broad indicator of innovation, encompassing product, process and ongoing innovations in the three-year period that includes the survey year. This general variable was further divided into two indicators for firms’ product and process innovations. The variables, named “product innovation” (PRODINNOV) and “process innovation” (PROCINNOV) are defined as dummies that take value one if a firm introduced a product or process innovation, respectively in the same three-year period. This differentiation between product and process innovations is significant as it helps distinguish between innovations driven by demand and those focused on cost reduction, respectively. Furthermore, this study incorporates a variable named “new product” (NEWPROD), which takes value one when a firm reports introducing products that are new to the market within the three years up to the survey year, zero otherwise. The inclusion of this variable is aimed at identifying radical innovations that represent new market offerings, distinguishing it from the previously mentioned variables. Finally, another variable named “innovative sales” (INNOVSALES), defined as the logarithm of sales in year t from innovative products introduced between \(t-2\) and t, was used to offer a financial perspective on product innovation within a given year. Hypothesis 1 examines the connection between the ESG orientation of innovative firms and their innovative outputs in the future, and this study employs these five different proxies to capture the outputs from various angles, encompassing general terms, product and process innovation, radical product innovations, and monetary payoff. We analyze the innovative performance of firms after treatment, that is in the 2009–2011 period and in the 2011–2013 periods, and therefore, we construct these performance variables using data from the 2011 and 2013 surveys, respectively.

We also consider other performance variables that do not refer to innovation outcomes. Labor productivity, exporting, and survival are critical dimensions that require thorough examination, as they are closely linked to the concept of sustainable competitive advantage. First, the variable “labor productivity” (LABORPROD) was defined as the logarithm of sales per employee in year t. While there are various ways to measure labor productivity throughout the value chain, this specific variable has been previously employed in the literature for the same purpose (Wagner, 2002; Datta et al., 2005). This variable was used because ESG-driven companies incorporate social aspects that have a direct impact on employee motivation. Therefore, we anticipate that this variable reflects the improvement in performance associated with these social aspects. Second, “exporting” (EXPORT) is defined as a dummy variable that takes value one if the firm exported in the last two years, zero otherwise. Given that innovation and internationalization are regarded as essential factors in enhancing national competitiveness, we included this variable to examine whether the influence of integrating ESG activities into a company’s strategy extends beyond the domestic market. In other words, the objective of this variable is to determine whether the social capital resulting from stakeholder interactions is limited to the specific market where the firm operates or if it has a broader reach. Finally, “survival” (SURVIVAL) was defined, following Zhang and Mohnen (2022) as a dummy variable that takes the value of one if the firm was active in the last two years, zero otherwise. This variable was used as it offers insights into the ongoing discussion between Agency Theory and Stakeholder Theory. It helps us examine whether the integration of ESG actions results in a decline in wealth (potentially leading to non-survival) or if companies manage to survive and thrive. As in the case of innovation performance variables, we carry out our analysis using performance data after treatment, that is for the 2009–2011 and 2011–2013 periods in the case of survival and exporting. In the case of labor productivity performance, which is observed yearly, post-treatment performance is measured in 2009 and 2011.

Regarding the selection variables used to construct the matched sample, as argued in the previous section, they are observed pre-treatment, that is in 2005 (when treatment is in 2006–2008), and 2007 (when treatment is in 2008–2010). Specifically, we use 14 industry dummies to control for industry differences and the following selection variables to control for specific firm characteristics: (1) PRODINNOV, binary indicator of being a product innovator (to control for past performance in product innovation); (2) PROCINNOV, binary indicator of being a process innovator (to control for past performance in process innovation); (3) LNINNOVEXP, logarithm of innovation expenditures (to control for absorptive capacity); (4) EMPLOYEES logarithm of number of employees (to control for firm size); (5) GROUP, binary indicator of belonging to a group of firms (to control for specific characteristics related with the inclusion within a group); (6) EXPORT, binary indicator of exporting (to control for prior experience in international relations); (7) LNINVEST, logarithm of physical investments (to control for difference on assets); (8) LNLABORPROD logarithm of labor productivity (to control for the skill mix); (9) MARKETOBST, perception of relevance of market being dominated by incumbents (to account for the perceived degree of competition in the market). Finally, following García-Vega and Huergo (2021), we also control for whether the firm belongs to the control group in 2005, which in our case means being innovative but a non-ESG firm in the 2003–2005 period. In our case, since the questionnaires prior to 2008 included only questions on environmental and governance goals, we classify a firms as being non-ESG if it gave a low or a medium/low importance to both environmental and governance goals in their innovation activities.

Regarding the matching procedure, many potential comparison groups may be used: non-innovative firms, innovative firms with a specific type of environmental, social, and governance orientation of their innovation efforts or innovative firms oriented to all the three ESG factors. In our case, the matched sample is drawn from the set of firms that are innovative in the reference period (2006–2008 or 2008–2010), but declare none of the three ESG factors to have a high or a medium importance (first criterion), or firms that are innovative in the reference period (2006–2008 or 2008–2010), but declare none of the three ESG factors to have a high importance (second criteria). These firms are called non-ESG firms. Therefore, in all cases, our matched sample is made up of innovative firms, to try to achieve the maximum comparability between treatment and control observations.

Table 2 displays the distribution of firms in each category for the year 2008 based on two distinct criteria used to classify ESG-driven companies. To be more specific, the first criterion categorizes ESG companies as those assigning medium-high importance to all ESG factors, while the second criterion defines ESG-driven companies as those assigning high importance to all these factors. The total number of firms is 11,182 and 2804 (25.08%) of them are non-innovators. These firms will not be included in the control group in any of our estimations. All comparisons will be made among firms that were innovative in the treatment period, whether 2006–2008 or 2008–2010. The remaining firms can be classified according to the orientation of their innovation strategies, depending on the importance attributed to environmental, social, and governance issues. In particular, the second column of the table presents the number of observations in each category based on the first classification criteria for ESG-driven companies (those that assigned medium-high, M.-H., importance to all ESG factors), while the fourth column displays the number of observations in each group according to the second criterion (to assign high importance, H., to the different ESG factors). As expected, since the second criterion is more strict, a higher percentage of firms fall into the category of innovative non-ESG firms (32.97% vs 50.33% ), while a smaller percentage are classified as innovative ESG firms (26.38% vs 9.7%). Additionally, under the second criterion, there are fewer firms in each of the three individual ESG categories.

Table 3 presents summary statistics for the different groups of firms, depending on their orientation of innovation activities in the 2006–2008 period, which is one of the two treatment periods that we consider. Specifically, the different columns display the mean and standard deviations of the different variables, distinguishing between the outcome variables and the variables used to construct the matched sample. Recall that the outcome variables refer to the post-treatment period (2009–2011 for all the variables except for the logarithm of labor productivity, which is observed in 2009), whereas the selection variables are observed in the pre-treatment period, that is, in 2005. For each group (environmental, social, governance, ESG, and non-ESG), we report the mean and standard deviation using the two classification criteria, namely giving a medium or high importance to these goals (M.-H.), or a high importance only (H.). We can observe that there is not much of a difference depending on the classification criterion or between firms in the three ESG factors, but there is a difference in the means of most of the outcome variables between the groups of ESG-driven and non-ESG firms. Looking at the selection variables, we also see that there is a similar imbalance. Precisely the matching procedure used in the empirical analysis will reduce the covariate imbalance between the treated and the control groups.

4 Discussion of the results

Tables 4 and 5 presents the results of the estimation of the average treatment effects on the treated, where the classification criterion used is firms giving a medium or high importance (M.-H.) to ESG factors. In order to carry out a more comprehensive analysis, in all tables, we present results using two reference periods. Specifically, in the top panel of each table, we report results using 2005–2011 data. In this case, the treatment period is 2006–2008, since innovation goals reported in 2008 refer to the 2006–2008 period, and performance refers to the 2009–2011 period. Pre-treatment selection uses data from 2005. Similarly, in the bottom panel of each table, we report results using 2008–2010 as the treatment period. This way, pre-treatment selection refers to 2007, and performance refers to the 2011–2013 period. In the analysis, the reported effects are to be interpreted as average treatment effects on treated, that is, the average effect for firms that are innovative and whose innovation strategy is oriented towards environmental goals, social goals, governance goals, or all three ESG goals, relative to firms that are innovative but that regard all three ESG goals as unimportant. Table 4 presents results for innovation-related variables (Hypothesis 1), specifically, being innovative, introducing at least one new product, introducing at least one new process, introducing at least one product that is new to the market, and percentage of sales from innovative products. Meanwhile, Table 5 report results for other performance variables, specifically the logarithm of labor productivity (Hypothesis 2), exporting (Hypothesis 3) and survival (Hypothesis 4). In the case of the top panel, where treatment is in the 2006–2008 period, exporting and survival refer to the 2009–2011 period, whereas labor productivity is for the year 2009, since it is constructed using annual data. In the case of the bottom panel, the analysis is shifted two years.

Hypothesis 1 argues that ESG-driven firms show a better future innovation performance than non-ESG driven companies. Analyzing Table 4 we observe that, under both panels, when we compare innovative firms with at least one ESG-related goal with with innovative non-ESG firms, those with ESG goals outperform their peers in terms of all the innovation outputs in the post-treatment period, that is 2009–2011. Specifically, in the first column of the top panel, we see that, depending on the particular ESG goal considered, ESG-driven companies are found to be about 15% more likely to be innovative in 2009–2011 than firms that were also innovative in 2006–2008 but declared that all three ESG goals had a low importance for their innovation activities, and the effects are statistically significant at the 1% level. All the estimated effects reported on the first column of the top panel are very similar numerically. In the bottom panel of the table, the results are qualitatively similar, with very minor differences in the size of the estimated effects. The rest of the columns of Table 4 report similar results. For instance, in the cases of introducing at least a new product (column 2: PRODINNOV), the coefficients are all positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, and all of them relatively close in numerical terms. A similar picture arises with introducing at least one new process (column 3: PROCINNOV)), and one product new to the market (column 4: NEWPROD). Regarding the percentage of innovative sales (column 5: INNOVSALES) in 2011 from products introduced in 2009–11, the estimated effect of ESG orientation is in the neighborhood of 8%, and statistically significant at the 1% level in all cases. Looking at the bottom panel, we notice that the estimated effect is somewhat smaller in absolute value, but positive and significant at the 1% level in all cases. Based on the reported results, we can conclude that hypothesis 1 is corroborated. These findings are in line with previous literature that have found a positive relationship between CRS/ESG and innovation performance (Porter & Kramer, 2006; Hull & Rothenberg, 2008; Bocquet et al., 2013; Reverte et al., 2016; Ueki et al., 2016). In addition to corroborating previous findings, in our case, the fact that the effect of the ESG orientation is positive and significant for all the indicators of innovation performance helps us to support the proposed link between the Stakeholder and Social Network Theories. As we previously stated, ESG-driven companies are distinguished by their proactive engagement with a diverse range of stakeholders, attentive consideration of their varying priorities, and the management of this information to inform decisions that benefit all parties. This paper argues that this aligns with the Social Network Theory of Innovation, which posits that knowledge is embedded within the various nodes of the network. The more these network nodes interact and take each other into account, the greater the likelihood of innovation. Hence, our expectation was that a larger number of stakeholders (as opposed to considering just shareholders) results in a greater diversity of contextualized information sources and, consequently, an increased likelihood of innovation that, in this paper, is represented on product or process improvements within the company, new products launched to the market or percentage of sales from innovative products.

Regarding other performance variables, the first column of Table 5 presents the results related with labor productivity (Hypothesis 2). If we focus on the comparison between ESG-driven companies and non-ESG driven companies, we can observe that the estimated effects, in both panels, are in all cases positive but statistically significant at the 10% level in the case of the top panel only. In the case of the bottom panel, the estimated effects are positive but insignificant, except in the case of social goals. These results represent partial support for Hypothesis 2 on the effect of the implementation of environmental, social and governance practices on the value chain, ultimately leading to cost reductions and operational enhancements (Porter & Kramer, 2006; Drempetic et al., 2020). The absence of a negative effect on productivity represents a lack of support for Agency Theory, in the sense that ESG orientation does not come at the expense of future performance and end up into wealth reduction.

The second column of the table refers to the probability of exporting (Hypothesis 3). In that case, when we analyze the comparison between ESG-driven firms and non-ESG driven firms, in both panels, the estimated effect on the probability of exporting is also positive and statistically significant, in most cases at the 1% level. These results corroborate Hypothesis 3, which argues that ESG-driven companies present a higher probability of exporting than non-ESG driven companies given their superior capabilities of adaptation, their stronger reputation and their easier access to capital. As innovation and internationalization are the key drivers of market competitiveness (Cassiman & Golovko, 2011; Cho & Pucik, 2005), the observation that the ESG effect exerts a significant and positive influence on factors related to innovation and exporting, reinforces the foundations of Stakeholder Theory. As previously stated, this theory posits that the proactive consideration and resolution of stakeholders’ concerns yield enduring and favorable outcomes for organizations in the long run. Thus, the consistent ESG impact on innovation and exporting activities serves to further underscore the validity of the Stakeholder Theory, emphasizing the benefits of prioritizing stakeholder engagement and addressing their concerns in the contemporary business environment.

Finally, the third column of the table, shows the results referring to survival (Hypothesis 4). Once more, when we examine the comparison between ESG-driven and non-ESG firms, we can observe that in both panels, the difference between these groups is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level. As in the previous table, the values of the estimated effects are very similar in all cases, in the neighborhood of 5%. This is consistent with our predictions in Hypothesis 4 and offer valuable insights into the prospective consequences of incorporating ESG into a company’s strategy. Notably, the positive and significant coefficients indicate that ESG investments do not compromise a company’s medium-term viability. On the contrary, they increase the odds of survival. Notice that the size of the effects is larger in the top panel, which considers survival during the post-recession years, 2009–2011. These findings are consistent with with the principles of Stakeholder Theory in contrast to those of Agency Theory.

In summary, this study uncovers a positive and substantial impact of ESG orientation across five innovation metrics, exporting, and firm survival, as well as a non-negative effect on labor productivity. When we consolidate all the results, it becomes evident that prioritizing ESG within a company’s strategy yields positive effects in the future. As a result, our findings do not align with Agency Theory, as we did not identify any evidence suggesting that ESG investments lead to a reduction in wealth that comes at the expense of the long-term firm performance. Instead, our results align with Stakeholder Theory, indicating that companies that prioritize ESG initiatives exhibit enhanced performance in terms of innovation outputs, exporting and survival rates, and a non-decreased performance in terms of labor productivity. Therefore, the improved performance seen in ESG-focused companies in these domains forms a robust basis for asserting that ESG objectives do not undermine overall firm performance, against the premises of Agency Theory.

In order to provide a more complete analysis, as a robustness check, we replicate our analysis in the previous two tables, using the second classification criterion regarding ESG-driven firms. Specifically, on the next two tables, ESG-driven firms are defined as those firms that assigned a high importance to all factors instead of high or medium importance. This way, as seen in Table 2, we reduce the number of firms in the ESG group, since we are imposing a more restrictive classification criterion. Table 6 presents estimated effects for innovation performance variables using the second criterion. If we pay attention to the comparison between ESG-driven and non-ESG firms (that now are defined as those companies that assigned low or medium importance to any of those ESG factors), we can still observe that ESG-driven companies outperform non-ESG companies in terms of all innovation indicators. In both panels, the statistical significance is high, at the 1% level in most of the cases, but the size of the effects is smaller. This may be due precisely to the stricter classification criterion: we may be including in the control group firms that are indeed ESG-driven, for which the performance will be similar to those firms in the treatment group. Since our classification relies on self-reported importance of ESG factors, we do not have access to the true ESG relevance of these factors. However, results reported on the two panels are consistent with ESG-driven firms having a better innovation performance than non-ESG firms. In the case of non-innovation performance variables (Table 7), a similar pattern arises: the size and statistical significance of the coefficients is reduced, especially in the case of the bottom panel. Specifically, in the top panel, the difference between ESG-driven and non-ESG firms in terms of labor productivity still is positive and significant in two of the four cases. However, the significance is not maintained in the bottom panel. In terms of exporting, it is evident that within this narrower criteria, an ESG innovation orientation does not exert any influence on the firm’s ability to export. A similar pattern arises in the case of survival, where significance is retained in the top panel, but not in the bottom panel. Therefore, our results are robust to the change in classification criterion in the case of innovation performance, but not so much in the case of non-innovation performance variables. In any case, firms that regard as important at least one of the three ESG factors do not underperform other innovative non-ESG firms in any of the dimensions considered.