Highlights

-

The strongly coupled Ag/Sn–SnO2 nanosheets (NSs) were prepared via a versatile electrochemical template strategy, and the generated electron-enriched Sn sites promote the formation of *OCHO and alleviate the energy barriers of *OCHO to *HCOOH.

-

Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs afford a superior activity toward CO2 electroreduction with current densities up to 2000 mA cm‒2 and near-unity selectivity for formate production.

-

Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs as the cathode in a membrane electrode assembly with porous solid electrolyte reactor enable the direct production of ~ 0.12 M pure HCOOH solution for 200 h.

Abstract

Electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 converts intermittent renewable electricity into value-added liquid products with an enticing prospect, but its practical application is hampered due to the lack of high-performance electrocatalysts. Herein, we elaborately design and develop strongly coupled nanosheets composed of Ag nanoparticles and Sn–SnO2 grains, designated as Ag/Sn–SnO2 nanosheets (NSs), which possess optimized electronic structure, high electrical conductivity, and more accessible sites. As a result, such a catalyst exhibits unprecedented catalytic performance toward CO2-to-formate conversion with near-unity faradaic efficiency (≥ 90%), ultrahigh partial current density (2,000 mA cm−2), and superior long-term stability (200 mA cm−2, 200 h), surpassing the reported catalysts of CO2 electroreduction to formate. Additionally, in situ attenuated total reflection-infrared spectra combined with theoretical calculations revealed that electron-enriched Sn sites on Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs not only promote the formation of *OCHO and alleviate the energy barriers of *OCHO to *HCOOH, but also impede the desorption of H*. Notably, the Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs as the cathode in a membrane electrode assembly with porous solid electrolyte layer reactor can continuously produce ~ 0.12 M pure HCOOH solution at 100 mA cm−2 over 200 h. This work may inspire further development of advanced electrocatalysts and innovative device systems for promoting practical application of producing liquid fuels from CO2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) technology provides an elegant route toward a carbon–neutral energy cycle, which addresses the requirements for storage of renewable energy in valuable carbon-based chemicals and fuels [1,2,3]. Liquid products have a higher volumetric energy density by contrast with gaseous-phase products, enabling them easier to store and distribute [4]. In particular, formate or formic acid (HCOOH) as an important feedstock is widely utilized in pharmaceutical, antiseptics, electrolytic metallurgy, and leather [5]. Unfortunately, to date, the reported electrocatalysts have all failed in commercialization requirements of CO2RR with Faradaic efficiency (FE) beyond 90%, partial current density close to 1 A cm–2, and long-term operation of at least 100 h [6, 7]. Moreover, the generated liquid product was usually mixed with soluble electrolytes in typical H-type or flow-type reactor [8], requiring extra energy-intensive downstream separation process to purify the liquid fuel solution for practical applications. Thus, it is urgently desirable to explore highly efficient electrocatalysts and develop insoluble electrolyte systems to achieve commercial-grade liquid fuel products.

Over the past decades, Sn-, Bi-, Pb-, and In-based electrocatalysts have been widely exploited for the reduction of CO2 to formic acid/formate [9,10,11,12]. Among these, Sn-based electrocatalysts are considered as the most promising candidates because of their low toxicity, large abundance, and low cost [13, 14]. However, owing to their medium binding energy to *H derived from HER, CO2 conversion over metal Sn is difficult to obtain desirable FEformate [15]. Besides, large overpotential was required to overcome the barrier associated with the initial electron transfer to CO2 form the CO2* intermediate due to poor electrical conductivity [16, 17]. Recently, it was reported that Sn–SnO2 derived from oxidized Sn or reduced SnO2 exhibits improved formate selectivity compared to bare Sn, arising from formation of oxygen vacancies or structural defects to enhance the stabilization of CO2RR intermediates [18, 19]. Nevertheless, Sn–SnO2 catalysts only achieved high FEformate in a narrow potential window and always delivered lower current density.

As known, the product selectivity is mainly related to the electronic configuration of the active sites in electrocatalysts. By reasonably combining foreign metal or non-metal components, it is capable of tailoring interaction between the active sites and intermediates to enhance selectivity [20,21,22,23]. Particularly, metal groups as moderator not only optimize the electronic structure of active sites, but also boost significantly its electrical conductivity. As the highest electrical conductivity of all metals, Ag (6.30 × 107 S m–1 at 20 ℃) is frequently utilized as a main constituent to increase the electrical conductivity of electrocatalysts [24,25,26,27,28], and its work function of 4.26 eV is also different from both Sn (4.42 eV) and SnO2 (5.24 eV) [29,30,31], which allows the possibility of manipulating the electronic configuration and electrical conductivity of Sn–SnO2 spontaneously. Moreover, the increasing number of actives sites, such as the construction of low-dimensional electrodes with more accessibility of catalytic sites, not only enhanced utilization of active centers, but also favored penetration of ions, promoted mass transport of gas, and thus ultimately improved the overall electrocatalytic performance [32, 33]. Consequently, we speculate that assembly of Sn–SnO2 units and metal Ag with delicately tuned electronic regulation could generate a significant synergistic effect for an efficient CO2RR.

Another prominent challenge that goes beyond the scope of electrocatalysts lies in the liquid products inevitably existing in a mixture with solutes in liquid electrolytes. In a conventional liquid electrolyte, KHCO3 or KOH as commonly solutes ensure fast ion conduction between the cathode and anode to obtain low ohmic drop [34]. The budding solid-state batteries adopt ion-conducting solid polymers or ceramics as alternatives of solution electrolyte to assist ions shuttle between anode and cathode [35, 36]. Motivated by this chemical principle, it is urgent to seek innovative electrolytes to replace typical soluble electrolytes, avoid energy-intensive separation, and produce pure fuel solution directly from CO2 electrolysers. An integration of rational design in both catalysts and electrolytes, for high activity and pure fuel output, respectively, would help to push the generation of liquid fuels via the CO2RR closer to large-scale application.

To support this hypothesis, herein, we designed and synthesized strongly coupled Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs through self-templating transformation and electrochemical reduction strategy. Benefiting from the optimized electronic structure, superior electrical conductivity, and abundant accessible sites, the obtained Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs can accomplish notable performance with an ampere-level current densities (2000 mA cm–2) and near-unity selectivity over 90% for CO2 electroreduction to formate production, which is much superior to previous reports. Meanwhile, it is also continuous to operate with high FEformate at a current density of 200 mA cm–2 for 200 h. The in situ attenuated total reflection-infrared (ATR-IR) spectra and theoretical analysis unraveled that coupling of Ag NPs induces the electronic enrichment of the Sn sites on Sn–SnO2 and thereby promotes generation of the crucial *OCHO intermediate and reduces energy barrier of *OCHO to *HCOOH conversion. In addition, to solve the downstream separation cost, porous solid electrolyte (PSE) layer was introduced into a membrane electrode assembly (MEA) reactor, in which the Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs as cathode catalyst can continuously reduce CO2 to ~ 0.12 M pure HCOOH solution for 200 h. This work could highlight significant understandings in both the development of advanced catalysts and superior devices for carbon–neutral technologies.

2 Experimental Procedures

2.1 Preparation of Electrocatalysts

2.1.1 Chemicals and Materials

Tin (II) chloride dihydrate (SnCl2·2H2O), silver nitrate (AgNO3), L-cysteine (C3H7NO2S), 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NMP), potassium bicarbonate (KHCO3), potassium hydroxide (KOH), and ethanol were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. Ag powder, dimethyl sulfoxide-D6 (99.9%, DMSO), deuterium oxide (D2O), and formic acid (HCOOH) were purchased from Energy Chemical Co., Ltd. Nafion solution (5 wt%) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. All chemical reagents were used directly without further purification. Ultrapure water (> 18.25 M Ω cm) was used for the experiments.

2.1.2 Preparation of SnS2 NSs

SnS2 NSs were synthesized according to the previously reported procedure [37]. In a typical synthesis, 0.228 g of SnCl2·2H2O and 0.349 g of L-cysteine were dissolved in 60 mL of NMP under magnetic stirring for 3 h. Afterward, the precursor solution was solvothermally reacted at 180 ℃ for 6 h. The product was centrifuged, washed with water and ethanol, and dried at 60 ℃ for 12 h.

2.1.3 Preparation of AgSO4/SnO2 NSs

SnS2 NSs as templates were used to fabricate bimetallic oxide nanosheets via cation exchange combined with high-temperature oxidation method. Firstly, 0.1 g of SnS2 NSs were dispersed in 80 mL of ethanol with sonication for 30 min. Subsequently, 20 mL of ethanol solution of AgNO3 (0.48 mM) was added to the above mixture with magnetic stirring for 12 h at 60 ℃. Finally, the Ag+-exchanged SnS2 NSs was collected, washed, and dried, and it was further calcined at 500 ℃ for 2 h in O2 with a heating rate of 5 ℃ min–1.

2.1.4 Preparation of Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs

Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs were obtained via an in situ electrochemical self-reconstruction process from AgSO4/SnO2 NSs in a three-electrode system. Typically, 10.0 mg of AgSO4/SnO2 NSs was dispersed in the mixture of water, ethanol, and 5 wt.% Nafion solution (8:1:1) with ultrasonic treatment for 30 min and casted onto a 1.0 × 1.0 cm2 carbon paper with the mass loading of 2.0 mg cm–2. The transformation was carried out in an H-type cell with two compartments separated by a piece of proton exchange membrane (Nafion 117). The working electrode and the reference electrode (saturated Ag/AgCl) were placed in the cathode compartment, and the counter electrode (Pt mesh) was placed in the anodic compartment. Each compartment contained 0.5 M KHCO3 electrolyte (15 mL). All potentials were converted to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) reference scale (ERHE = EAg/AgCl + 0.198 V + 0.0591 V × pH). The cathodic transformation of AgSO4/SnO2 NSs to Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs was performed via the electrolysis of AgSO4/SnO2 NSs at ‒1.17 V for 15 min in CO2-saturated 0.5 M KHCO3 electrolyte.

2.1.5 Preparation of Sn–SnO2 NSs

Firstly, the obtain SnS2 NSs were converted into SnO2 NSs at 500 ℃ for 2 h in O2 with a heating rate of 5 ℃ min−1. Subsequently, the converted SnO2 NSs were cathodically reduced to Sn–SnO2 NSs, following the similar procedures to Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs.

2.2 Performance Evaluation

2.2.1 H-type Cell Measurements

The carbon fiber paper supported Ag/Sn–SnO2 (or Sn–SnO2) catalyst was directly used as the working electrode in the typical H-type cell with two compartments. The electrolyte was pre-saturated with Ar (pH = 8.4) or CO2 (pH = 7.4). A constant CO2 flow of 20 sccm was continuously bubbled into the electrolyte to maintain its saturation during CO2RR measurements.

2.2.2 Flow Cell Measurements

It consisted of a gas diffusion electrode (GDE) loaded with Ag/Sn–SnO2 (2.0 mg cm−2, 1.0 × 0.5 cm2) as the cathode, a piece of bipolar membrane as the separator, and a porous nickel foam as the anode. Ag/AgCl reference electrode was located inside the cathode compartment. During the measurements, CO2 gas was directly fed to the cathodic GDE at a rate of 20 sccm. 1.0 M KOH was used as the electrolyte throughout the measurements, which was forced to continuously circulate in the cathode and anode chambers by using peristaltic pumps with 40 mL min‒1.

2.2.3 Solid Electrolyte Cell Measurements

The two-electrode cells with solid proton conductor were provided by Wuhan Zhisheng New Energy Co., Ltd., and used for pure HCOOH solution production, in which an anion exchange membrane and proton exchange membrane were used for anion and cation exchange, respectively. Around 1 mg cm−2 Ag/Sn–SnO2 loaded onto the GDL electrode (2.0 cm2 electrode area) was used as the cathode, and IrO2 was loaded onto a titanium mesh as the anode. The cathode side was supplied with 30 cm3 min–1 humidified CO2 gas, and 0.1 M H2SO4 aqueous solution was circulated around the anode side with 2 mL min−1. Porous styrene–divinylbenzene sulfonated co-polymer was used as the solid ion conductor. Deionized water or humidified N2 flow was used to release the HCOOH produced within the solid-state electrolyte layer.

2.3 Computational Methods

All calculations were carried out using Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP) based on the density functional theory (DFT) [38, 39]. The projector-augmented wave (PAW) with generalized gradient approximation and Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof functional was used for the electron–ion interactions with a cutoff energy of 500 eV [40, 41]. A vacuum region of 15 Å along the out-plane direction was applied to avoid interactions between the neighboring cells of slab models. Besides, the effect of van der Waals (vdW) interactions was included using the correction scheme of Grimme (D2). According to the experimental characterization results, we constructed model of an Sn–SnO2 cluster loaded on Ag (111) to simulate Ag/Sn–SnO2. The Bader charge was calculated using the Bader Charge Analysis script by Henkelman and coworkers. The charge transfer from Ag to Sn atom in Sn–SnO2 was verified by the Bader charge and differential charge density. The Brillouin zone was sampled on a Monkhorst–Pack k-mesh (1 × 1 × 1 in the structural optimization of Sn–SnO2, 3 × 3 × 1 for Ag/Sn–SnO2), and the structures were optimized until all the atomic forces have declined below 0.02 eV Å−1. The free energy of CO2 reduction (ΔG) is defined as:

where ΔE denotes calculated total energy change, T represents the temperature (298.15 K), ΔS is the entropy change, and ΔEZPE is zero-point energy change.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Synthesis of Strongly Coupled Ag/Sn–SnO2 Nanosheets

The strongly coupled Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs were engineered via using a versatile electrochemical template strategy (Fig. 1). Here, the SnS2 NSs were first prepared according to the solvothermal method (Fig. S1), followed by a facile anion exchange process to obtain silver–tin bimetallic sulfides, designated as Ag–SnS2. During this process, the Sn cations from SnS2 NSs were partially replaced by Ag+ ions due to the smaller solubility product constant of Ag2S (\(K_{{sp,\;{\text{Ag}}_{2} {\text{S}}}} \le K_{{sp,{\text{ SnS}}_{2} }}\)), and their lamellar structure remained almost the same. After calcination treatment in oxygen, the Ag atoms in Ag–SnS2 easily escaped from nanosheets, and the coordinated S atoms rapidly formed SO3, which aggregated and converted into Ag2SO4 NPs; meanwhile, Sn atoms kept a lower migration rate inside the nanosheets, and the surrounding S atoms were replaced by O atoms. As a result, the Ag–SnS2 NSs evolved into coupled Ag2SO4/SnO2 composites, in which Ag2SO4 NPs were confined in the nanosheets composed of dense SnO2 grains. Finally, the obtained Ag2SO4/SnO2 NSs were converted into Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs under operando CO2RR conditions. The coupled Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs were pasted on GDE and fixed in a MEA with PSE layer reactor to achieve a direct and continuous production of pure HCOOH solution.

3.2 Characterizations of Strongly Coupled Ag/Sn–SnO2 Nanosheets

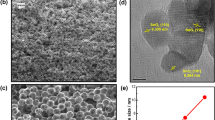

The silver–tin bimetallic NSs, synthesized by utilizing SnS2 NSs as self-templates, were characterized. Typical transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high-angle annular dark-field scanning TEM (HAADF-STEM) images (Figs. 2a, b and S2a–d) demonstrate that the morphology of SnS2 NSs remains unchanged after Ag+ ion-exchange reactions. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) spectrum combined with corresponding mapping images (Fig. S2e, f) confirm that the Ag element was successfully introduced into SnS2 NSs with uniform distribution. After the pyrolysis in O2 atmosphere, the bimetallic sulfide was transformed into the hybrid Ag2SO4/SnO2. The morphology and structure of the Ag2SO4/SnO2 composite were examined by TEM and high-resolution TEM (HRTEM). As shown in Figs. 2c and S3a, b, some nanoparticles with ~ 10–20 nm in diameter emerge from nanosheets composed of small grains connected each other. Based on the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern (Fig. S3c), two kinds of diffraction rings were found, including the (110), (200), (211), and (301) planes of cubic SnO2, and the (200) plane of orthorhombic Ag2SO4. HRTEM image and corresponding fast Fourier transform pattern reveal that the nanoparticle is Ag2SO4, which is surrounded by many SnO2 grains (Fig. S3d–f). EDX mapping images show these Ag2SO4 NPs separately embedded into SnO2 NSs (Fig. S3g). Besides, their crystal structure and surface statement of Ag2SO4/SnO2 were also further characterized by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) technology (Fig. S4).

Typical TEM images: a SnS2 NSs, b Ag-SnS2 NSs, c Ag2SO4/SnO2 NSs, d Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs, e Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs. f Particle size distribution of Sn–SnO2 from Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs. g HRTEM image and corresponding FFT pattern of Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs, integrated pixel intensities of Ag, Sn, SnO2. h HAADF-STEM image and EDX mapping images of Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs

To obtain Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs, the as-synthesized Ag2SO4/SnO2 precursor was dispersed and pasted on carbon paper and subjected to − 1.8 V versus RHE for 60 min in CO2-saturated 0.5 M KHCO3 electrolyte. After the electrochemical conversion, the catalyst was collected for further characterization. PXRD pattern unveils that Ag2SO4 was completely transformed into Ag in the electrocatalysts, while SnO2 was partially reduced to Sn metal (Fig. S5). As shown in Fig. 2d, no obvious change in morphology is observed after the electroreduction of Ag2SO4/SnO2 NSs, and the derived Ag NPs are still separately located in the nanosheets that are composed of Sn–SnO2 grains with ~ 5.6 nm in size (Fig. 2e, f). HRTEM image (Fig. 2g) distinctly shows a region of interfacial contact among three different crystal planes with lattice spacings of about 0.24, 0.29 and 0.34 nm, belonging to the (111) plane of Ag, the (200) plane of Sn, and the (110) plane of SnO2, respectively. The derived Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs possess intimate interfaces of Ag and Sn–SnO2, which was also confirmed by corresponding EDX mapping images and EDX line scans (Figs. 2h and S6). The Sn–SnO2 NSs were also prepared for comparison through the similar procedure (Figs. S7 and S8). Further insight into the chemical states of Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs was obtained by XPS. As shown in Fig. S9a, Ag 3d spectrum for Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs fits well with two pairs of characteristic peaks at 368.1 and 373.9 eV, and 367.6 and 373.6 eV, which can be assigned to metal Ag and Ag+, respectively [42]. As for Sn 3d spectrum in Fig. S9b, the two sets of doublet peaks for Ag/Sn–SnO2 at the binding energy of 484.9 and 494.2 eV together with 486.1 and 494.8 eV ascribe to metal Sn and Sn4+, respectively [43]. Obviously, the binding energy of Sn 3d in Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs negatively shifted 0.15 eV compared to that of Sn–SnO2 NSs, indicating the electronic interaction between the Ag NPs and the Sn–SnO2 NSs.

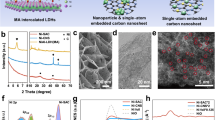

In order to deeply investigate the effect of Ag NPs on the electronic and coordination structure of Sn–SnO2, X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) was carried out. The XANES spectra of the Ag K-edge in different samples (Fig. 3a) show that the adsorption edges of Ag/Sn–SnO2, Ag2O, and Ag foil are very close to each other. The magnified image (inset in Fig. 3a) shows that Ag/Sn–SnO2 exhibits a tendency for the pre-edge feature to shift to Ag2O, compared with the Ag foil. The K3-weighted EXAFS spectra of Ag/Sn–SnO2 in Fig. 3b show that the two main peaks correspond to Ag–O and Ag–Ag (Ag-Sn) bonds compared to Ag2O and Ag foil. It is worth noting that the interatomic distance of the Ag–Ag bond (2.92 Å) in Ag/Sn–SnO2 is slightly longer than that of Ag foil (2.86 Å) due to the formation of Ag-Sn bonding, which is further verified by the Ag K-edge EXAFS fitting results displayed in Figs. S10 and S11 and Table S1. In the XANES spectra of the Sn K-edge (Fig. 3c), the edge position of Sn–SnO2 and Ag/Sn–SnO2 located between those of Sn foil and SnO2, and Ag/Sn–SnO2 shifted to lower energy compared with Sn–SnO2, suggesting their decreased congruity in the coordination environment. To further illustrate the fine structure of Ag/Sn–SnO2, their XANES spectra are compared and shown in Fig. 3d, in which the peaks at 1.34 and 2.42 Å are attributed to the Sn–O bond and Sn–Sn (Sn–Ag) interaction, respectively. A slight compression of the Sn–Sn bond derives from the difference between the atomic radii of Sn and Ag, further confirming their successful alloying. The wavelet transform analysis also confirmed the different coordination of Sn atom between the Sn–SnO2 and Ag/Sn–SnO2 samples (Fig. 3e). According to the Sn K-edge EXAFS fitting curves (Table S2), it is noticed that the average coordination numbers of Sn–O (3.7), Sn–Ag (2.0), and Sn–Sn (2.1) in Ag/Sn–SnO2 are obviously less than those of Sn–O (4.7) and Sn–Sn (3.1) in Sn–SnO2, implying the emergence of coordinatively unsaturated Sn sites after the coupling of Ag. Usually, these unsaturated metal atoms would cause structural distortions or defects, leading to greatly modified electronic properties. The work functions of Ag/Sn–SnO2 and Sn–SnO2 were further investigated to clarify the difference in their electronic properties by ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS). Sn in Sn–SnO2 is easily oxidized back to SnO2 during the UPS preparation, so that the work function of Sn–SnO2 (5.17 eV) does not obviously decrease compared to that of SnO2. In contrast to transition metal, noble metal Ag is difficult to be oxidized, and the coupled Ag/Sn–SnO2 displays a markedly lower work function (4.73 eV). Thus, Ag NPs would transfer electrons to Sn–SnO2, which is further confirmed by the cyclic voltammetry (CV) test (Fig. S13), inducing an upshift of the Fermi level of Ag/Sn–SnO2 (Fig. 3f). Briefly, it is concluded that the introduction of Ag into Sn–SnO2 facilitates the electron transfer from Ag atoms to Sn atoms in Sn–SnO2, leading to electron enrichment in Sn–SnO2 surfaces (Fig. 3g).

Fine-structure characterization: a Ag K-edge XANES spectra, b Ag K-edge extended XANES oscillation functions K3χ(k), c Sn K-edge XANES spectra, d Sn K-edge extended XANES oscillation functions K3χ(k), e Wavelet transform EXAFS of Sn of Sn foil, Sn–SnO2, Ag/Sn–SnO2, and SnO2. f UPS spectra of Ag/Sn–SnO2 and Sn–SnO2. g Schematic illustration of electron transfer at Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs

3.3 Electrocatalytic CO2RR Performances in Typical Reactor

The catalytic performance of Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs for CO2 electroreduction was evaluated in an H-type reactor using 0.5 M KHCO3 as electrolyte. As shown in Fig. 4a, the current densities of Sn–SnO2 NSs are enhanced with the combination of Ag NPs, and it exhibits considerable current densities of 69 mA cm−2 compared to Sn–SnO2 NSs with 29.5 mA cm−2 at –1.37 V. The promotion of current density by Ag coupling was further confirmed by the linear scanning voltammetry (LSV) curves in Ar-saturated KHCO3 electrolyte. The products of CO2RR were quantitatively analyzed at different potentials between − 0.67 and − 1.37 V over Sn–SnO2, and Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs (Figs. S14–S16). Figure 4b shows that the FEformate of Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs can remain above 90% in a wide range of potentials from –0.87 to –1.37 V with the maximum value of ~ 93% at − 1.17 V, which is 1.2 times larger than that of Sn–SnO2 NSs (78%). When bare Ag NPs were utilized as electrocatalysts, only conversion of CO2 toward CO was achieved (Fig. S16). We further calculated the partial current density of formate (jformate) for Ag/Sn–SnO2 and Sn–SnO2 NSs at all of applied potentials. As shown in Fig. 4c, Ag/Sn–SnO2 is capable of delivering a jformate of about 48.5 mA cm−2 at − 1.37 V, which is about 3 times higher than that of Sn–SnO2 (16 mA cm−2). Besides, the effect of Ag content in Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs on the performance of CO2 reduction was also investigated (Fig. S17). With the increase of Ag content, the current density increases from 30 to 67 mA cm−2 and then decrease to 58 mA cm−2. The corresponding FEformate also follows volcanic-like trend at the applied potential of − 1.27 V, which may be due to that part of the Ag, which is not in close contact with Sn–SnO2, tends to reduce CO2 to CO.

Electrocatalytic CO2RR performance in typical reactors: a LSV curves, b FE of formate CO and H2, c partial current densities of formate of Sn–SnO2 NSs and Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs of H-type reactor in 0.5 M KHCO3; d FE of formate and partial current densities of formate of Sn–SnO2 NSs and Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs, e cathodic energy efficiency of formate of Sn–SnO2 NSs and Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs, f yield of formate over Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs, g long-term amperometric stability of Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs, h comparison of stability, FE of formate, and current density with those of reported Sn-based catalysts of Flow-type reactor

To decipher the origin of high activities of Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs, their double layer capacitances (CdI) were estimated according to corresponding electrochemically active surface areas (Fig. S18a). The CdI of Ag/Sn–SnO2 and Sn–SnO2 NSs were calculated to be 1.62 and 0.66 mF cm−2, respectively, illustrating that the Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs can provide more active sites. The CdI-normalized jformate value of Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs was larger than that of Sn–SnO2 NSs (Fig. S18b), elucidating Sn–SnO2 NSs with improved intrinsic activity by incorporation of Ag NPs. To gain insight into the reaction kinetics, the Tafel slopes of the catalysts were plotted in Fig. S18c. The Tafel slope of Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs (107.2 mV dec–1) is lower than that of Sn–SnO2 NSs (172.8 mV dec–1), indicating the favorable kinetic activity for the electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to formate over Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs. Moreover, multi-step proton–electron coupling is involved in the reduction of CO2, and the charge transfer process from catalysts to intermediates was also investigated by the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). By contrast, Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs have a smaller impedance value of ~ 10 Ω compared to Sn–SnO2 NSs (~ 60 Ω) (Fig. S18d), implying good electrical conductivity, which confirms that after combination with Ag, the charge transfer resistance of Sn–SnO2 is significantly decreased and thus promotes the reaction kinetics. Furthermore, the oxidative LSV scans under Ar-bubbled KOH electrolyte further displayed that the potential for OH– adsorption on the Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs surface was more negative than that of Sn–SnO2 NSs, suggesting its most powerful ability to stabilize the CO2*− intermediate (Fig. S19). To the best of our knowledge, Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs exceed previously reported Sn-based electrocatalysts for formate production by CO2RR in H-type reactor (Fig. S20 and Table S3). In addition, Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs also exhibits good stability with high FEformate during a 25-h potentiostatic test (Fig. S21). After the long-term test, no obvious changes in crystallinity, surface statement, and morphology for the Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs are observed (Fig. S22), elucidating their good activity and stability.

Gas diffusion electrode (GDE) can overcome mass-transfer limitation of CO2 due to its low solubility in aqueous solution and promotes the realization of the industrial-level current density, and the CO2RR performance of Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs was further measured in a flow-type reactor (Fig. S23). Figures 4d and S24 show that Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs gave above 90% FEformate over a wide potential window from –0.43 to –2.02 V, while Sn–SnO2 delivered lower formate selectivity as it failed to suppress competitive HER. By contrast, Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs achieved an ultrahigh formate partial current density of 2000 mA cm–2 at –2.01 V, outperforming most of the advanced electrocatalysts for formate generation by CO2RR (Figs. 4d and S24f). In the meantime, Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs manifested a higher cathodic energy efficiency (CEE) than that of Sn–SnO2 for reduction of CO2 to formate (Fig. 4e). To further intuitively evaluate the efficiency of Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs, the corresponding formate yield at the selected potentials per unit catalyst load area and time was also calculated. As shown in Fig. 4f, the yield of formate for Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs increased with the increase of applied potential, and the value reached 33.5 mol h–1 cm–1 at 2.02 V. Moreover, the long-term stability a CO2RR electrocatalyst is another prerequisite for its practical implementation. Correspondingly, the constant-current electrolysis of Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs at the current density of 200 mA cm–2 in the flow-type reactor was operated and is displayed in Fig. 4g. Clearly, no obvious increase in potential was noticed after 200 h continuous electrolysis. Meanwhile, an excellent formate selectivity was well maintained, illustrating the industrial superiority and feasibility of the Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs at such a large current density. Such remarkable catalytic performance of Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs is the best one among those reported catalysts of CO2 electroreduction to formate (Fig. 4h and Table S4).

3.4 In Situ Characterizations and Theoretical Calculations

To further understand the electroreduction of CO2 to formate process, operando ATR-IR spectra were performed to monitor the intermediates. As shown in Fig. 5a, an upward peak at 1401 cm–1 is assigned to the *OCHO group [9, 10], and another downward peak at 1630 cm−1 is ascribed to interfacial H2O [44, 45], implying that the *OCHO intermediate was generated while the absorbed H2O molecules were participated for Sn–SnO2. Remarkably, the consumption of interfacial H2O is equivalent to the formation of *OCHO, implying that the reduction of CO2 is accompanied by significant H2 evolution. By integrated Ag NPs in Sn–SnO2 NSs, the consumption of absorbed H2O characteristic band is obviously suppressed (Fig. 5b), and corresponding relative peak area ratio of *OCHO/H2O for Ag/Sn–SnO2 is bigger than Sn–SnO2 (Fig. 5c), which clarifies that Ag/Sn–SnO2 can effectively weaken the formation of H2 and promote the reduction of CO2. A weak peak belonging to *COOH group was observed at 1268 cm−1 [46], because the uncovered Ag in Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs prefer to bond the formation of CO intermediate (Fig. 5b). Based on the analysis of electrochemical in situ FTIR results, it is likely that CO2 reduction follows the reaction pathway listed as follows:

First-principles calculations were carried out to gain insights into high performance of CO2 electroreduction over Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs. The Ag/Sn–SnO2 slab was modeled by optimizing the Sn–SnO2 grains on the surface of Ag NPs (Fig. S25), and corresponding Gibbs free energy for each reaction step of CO2RR process was calculated (Fig. S26). As shown in Fig. 5d, the formation of intermediate HCOO* is an exothermic process, and Ag/Sn–SnO2 occupies obviously lower key *OCHO intermediate formation energy compared to Sn–SnO2. The transformation of *OCHO to *HCOOH is the most endothermic on both systems and uphill energy on Ag/Sn–SnO2 is smaller than that on Sn–SnO2 (0.82 vs. to 0.98 eV), indicating that HCOOH formation on Ag/Sn–SnO2 is more favorable. Subsequently, the desorption of *HCOOH only needs to overcome the smaller energetic barriers for both, illustrating that the second proton-coupled electron step dominates the CO2 reduction process. Charge density difference plots of OCHO adsorption on Ag/Sn–SnO2 and Sn–SnO2 are presented in Fig. 5e. Notably, charge redistribution over Ag/Sn–SnO2 is the more significant, rationalizing the stronger adsorption. Moreover, Bader charge analysis reveals that the *OCHO species on Ag/Sn–SnO2 obtains a charge of 0.690 |e|, which is greater than that (0.686 |e|) on Sn–SnO2, indicating that the electrons of Sn atoms in Ag/Sn–SnO2 are easily transferred to *OCHO. In addition, as main side reaction, HER was also studied (Fig. S27), and the free energy profiles are displayed in Fig. 5f. The uphill free energy of the desorption of *H to H2 on Ag/Sn–SnO2 surface is much higher than that on Sn–SnO2 (Fig. 5f), suggesting the superior inhibition of H2 production. Overall, both experimental and theoretical results elucidate that the coupled Ag/Sn–SnO2 with electron-rich Sn sites not only facilitates the successive hydrogenation of *CO2 to *OCHO to *HCOOH, but also further hinders H2 formation, thus resulting in enhancement selectivity of formate in a wide range of potential (Fig. 5g).

Up to now, although formate can be exclusively generated via a CO2RR approach with high-performance electrocatalysts, the as-obtained products were in low concentrations actually and mixed with solute salts, which requires extra separation and concentration treatments to obtain pure liquid fuel for subsequent applications. To promote large-scale application of producing liquid fuels from CO2RR pathway, porous solid electrolytes (PSE) is employed to replace water-soluble electrolytes and achieve direct synthesis of pure liquid acid solution. PSE layer can efficiently deliver ions between the cathode and anode, but does not introduce additional solutes to mix with produced HCOOH. As shown in Figs. 6a and S28, the cathode and anode of PSE layer are Ag/Sn–SnO2-coated GDE and Ti mesh-supported IrO2, which sandwiched cation exchange membranes (CEMs) and anion exchange membranes (AEMs), respectively. The cathode side was uninterruptedly supplied with humidified CO2 flow for CO2RR, and generated HCOO− ions on Ag/Sn–SnO2 were driven to pass through the AEM and arrive the middle PSE layer by the electrical field. Meanwhile, the anode side was circulated with 0.1 M H2SO4 solution for water oxidation, and H+ generated on IrO2 moved through the CEM into the middle PSE layer. In the middle chamber, a PSE layer facilitated ion transportation with minimized ohmic losses, and the HCOOH molecules formed via the ionic recombination were then efficiently brought out through this porous layer via the flow of deionized (DI) water or N2 vapor.

Operando ATR-IR spectra collected at different applied potentials in CO2-saturated 0.5 M KHCO3: a Sn–SnO2, b Ag/Sn–SnO2, c comparison of the relative peak area ratio of *OCHO/H2O. Theoretical calculations for Ag/Sn–SnO2 and Sn–SnO2: d free energy profiles of CO2 reduction to HCOOH, e differential charge density plot of the *OCHO intermediate adsorption structure, f free energy profiles of H2 evolution. g Schematic diagram of CO2RR over electron-rich Sn sites and electron-neutral Sn sites

Electrocatalytic CO2RR performance of Ag/Sn–SnO2 in a 2 cm2 MEA with PSE layer reactor: a schematic illustration of CO2 reduction to pure HCOOH with OER reaction in the PSE-cell (The pure HCOOH product can be formed via the ionic recombination of crossed HCOO− and H+ ions in the PSE layer, and diffuse away through DI water or N2 vapor flow). Concentration of HCOOH under different cell currents, along with the corresponding FEHCOOH, b DI water as diffuse carrier with flow rate of 60 mL h−1, c humidified N2 as diffuse carrier with flow rate of 100 sccm. Long-term electrolysis under a current density of 100 mA cm−2, d humidified N2 as diffuse carrier with flow rate of 100 sccm, e DI water as diffuse carrier with flow rate of 20 mL h−1

The LSV curve of CO2RR in a 2 cm2 Ag/Sn–SnO2//PSE//IrO2 cell plotted in Fig. S29a shows that the overall current density gradually increases as the cell voltage ramps up. The selectivity of HCOOH in the PSE-cell follows volcanic-like trend and max FEHCOOH reaches up to 83% (Figs. 6b and S29b), but their value is lower compared to results of typical reactors, which rooted in the different pH (acidic pH in MEA with PSE and neutral/alkaline pH in H-type/flow-type reactor, respectively) and the liquid product distribution. With the increase of current density, corresponding concentration of HCOOH solution varies from 15 to 130 mM at this deionized (DI) water flow rate (Fig. 6b), and maximum partial current density is 350 mA cm−2 (Fig. S29c). To further improve concentration of the generated HCOOH, humidified N2 was employed to replace the DI water to carry HCOOH molecules in PSE layer. As shown in Fig. S29d, the overall current density also reaches 1000 mA with a fixed N2 flow rate of 100 sccm. It is observed in Figs. 6c and S29e that FEHCOOH also follows a trend of rising up first and then falling down, but the concentration of HCOOH is significantly improved under the same current, and corresponding current density can reach 270 mA cm−2 (Fig. S29f).

In view of the advantage of producing high-concentration HCOOH solution with humidified N2 flow, a long-term electrolysis experiment was also implemented to realize the continuous production of pure HCOOH solution. However, it was noticed that the cell voltage was apparently increased to maintain the current of 200 mA as the electrolysis time was prolonged (Fig. 6d), which is mainly attributed to the gradual degradation of membranes and solid electrolytes without enough wetting conditions [47]. Because it is difficult to prevent the degradation of AEM on the current technical level, DI water as a substitute was utilized to explore the durability of Ag/Sn–SnO2 for long-term operation at the same current for reduction of CO2 to pure HCOOH with a lower flow rate of 20 mL h−1. Strikingly, a stable production of ~ 0.1 M pure HCOOH was achieved at a large current density of 100 mA cm−2 during 200 h continuous electrolysis periods (Fig. 6e). Such unparalleled activity, yield, and excellent long-term stability for reduction of CO2 to pure HCOOH surpass previous reports (Table S5). Consequently, the exceptional results of Ag/Sn–SnO2 present promising prospect of commercial production of pure HCOOH from CO2.

4 Conclusions

In conclusion, we have developed strongly coupled Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs by combined self-templating transformation and electrochemical reduction strategy. On account of its regulated electron configuration and superior electrical conductivity, the Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs with ample accessible sites as electrocatalysts are capable of exhibiting a combination of high activity and stability in the CO2-to-formate reduction exceeding 200 h of continuous operation, outperforming most of reported Sn-based electrocatalysts. Moreover, operando ATR-IR spectroscopy and theoretical calculations reveal that the incorporation of Ag NPs into Sn–SnO2 NSs can promote the formation of the *OCHO, alleviate the energy barriers of *OCHO to *HCOOH, and suppress the competitive H2 production. Additionally, Ag/Sn–SnO2 NSs as the cathode in a MEA with PSE reactor enable the direct production of ~ 0.12 M pure HCOOH solution for 200 h. The momentous achievements in this work would be indicative to integrating the electrode materials and electrolytic systems for accelerating the practical application of carbon–neutral technologies.

References

J. Ma, X. Xiong, D. Wu, Y. Wang, C. Ban et al., Band position-independent piezo-electrocatalysis for ultrahigh CO2 conversion. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300027 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202300027

B. Yang, K. Liu, H. Li, C. Lui, J. Fu et al., Accelerating CO2 electroreduction to multicarbon products via synergistic electric–thermal field on copper nanoneedles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 3039–3049 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c11253

Q. Wang, M. Dai, H. Li, Y. Lu, T. Chan et al., Asymmetric coordination induces electron localization at ca sites for robust CO2 electroreduction to CO. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300695 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202300695

H. Shin, K.U. Hansen, F. Jiao, Techno-economic assessment of low-temperature carbon dioxide electrolysis. Nat. Sustain. 4, 911–919 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00739-x

J. Fan, X. Zhao, X. Mao, J. Xu, N. Han et al., Large-area vertically aligned bismuthene nanosheet arrays from galvanic replacement reaction for efficient electrochemical CO2 conversion. Adv. Mater. 33, e2100910 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202100910

M. Zhong, K. Tran, Y. Min, C. Wang, Z. Wang et al., Accelerated discovery of CO2 electrocatalysts using active machine learning. Nature 581, 178–183 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2242-8

F.P. García de Arquer, C.T. Dinh, A. Ozden, J. Wicks, C. McCallum et al., CO2 electrolysis to multicarbon products at activities greater than 1 A cm−2. Science 367, 661–666 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay4217

C. Xia, P. Zhu, Q. Jiang, Y. Pan, W. Liang et al., Continuous production of pure liquid fuel solutions via electrocatalytic CO2 reduction using solid-electrolyte devices. Nat. Energy 4, 776–785 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-019-0451-x

M. Zhang, S. Zhou, W. Wei, D.-D. Ma, S.-G. Han et al., Few-atom-layer metallene quantum dots toward CO2 electroreduction at ampere-level current density and Zn-CO2 battery. Chem Catal. 2, 3528–3545 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.checat.2022.10.001

M. Zhang, W. Wei, S. Zhou, D.-D. Ma, A. Cao et al., Engineering a conductive network of atomically thin bismuthene with rich defects enables CO2 reduction to formate with industry-compatible current densities and stability. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 4998–5008 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1039/D1EE01495A

Y. Shi, Y. Ji, J. Long, Y. Liang, Y. Liu et al., Unveiling hydrocerussite as an electrochemically stable active phase for efficient carbon dioxide electroreduction to formate. Nat. Commun. 11, 3415 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17120-9

H. Shang, T. Wang, J. Pei, Z. Jiang, D. Zhou et al., Design of a single-atom indiumδ+–N4 interface for efficient electroreduction of CO2 to formate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22465–22469 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202010903

L. Li, A. Ozden, S. Guo, A.D.A.F.P. Garci, C. Wang et al., Stable active CO2 reduction to formate via redox-modulated stabilization of active sites. Nat. Commun. 12, 5223 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25573-9

W. Wang, Z. Wang, R. Yang, J. Duan, Y. Liu et al., In Situ phase separation into coupled interfaces for promoting CO2 electroreduction to formate over a wide potential window. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 22940–22947 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202110000

Y. Chen, M.W. Kanan, Tin oxide dependence of the CO2 reduction efficiency on tin electrodes and enhanced activity for tin/tin oxide thin-film catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 1986–1989 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja2108799

W. Luc, C. Collins, S. Wang, H. Xin, K. He et al., Ag–Sn bimetallic catalyst with a core-shell structure for CO2 reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1885–1893 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.6b10435

K. Ye, Z. Zhou, J. Shao, L. Lin, D. Gao et al., In situ reconstruction of a hierarchical Sn–Cu/SnOx core/shell catalyst for high-performance CO2 electroreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 4814–4821 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201916538

H. Liu, B. Li, Z. Liu, Z. Liang, H. Chuai et al., Ceria-mediated dynamic Sn0/Snδ+ redox cycle for CO2 electroreduction. ACS Catal. 13, 5033–5042 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.2c06135

Y. Jiang, J. Shan, P. Wang, L. Huang, Y. Zheng et al., Stabilizing oxidation state of SnO2 for highly selective CO2 electroreduction to formate at large current densities. ACS Catal. 13, 3101–3108 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.3c00123

M. Chen, S. Wan, L. Zhong, D. Liu, H. Yang et al., Dynamic restructuring of Cu-Doped SnS2 nanoflowers for highly selective electrochemical CO2 reduction to formate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 26233–26237 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.202111905

C. Chai, B. Liu, K. Liu, P. Li, J. Fu et al., Heteroatoms induce localization of the electric field and promote a wide potential-window selectivity towards CO in the CO2 electroreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202212640 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202212640

T. Wang, J. Chen, X. Ren, J. Zhang, J. Ding et al., Halogen-incorporated Sn catalysts for selective electrochemical CO2 reduction to formate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202211174 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202211174

S. Yan, C. Peng, C. Yang, Y. Chen, J. Zhang et al., Electron localization and lattice strain induced by surface lithium doping enable ampere-level electrosynthesis of formate from CO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 25741–25745 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.202111351

M. Yu, G.H. Moon, R.G. Castillo, S. DeBeer, C. Weidenthaler et al., Dual role of silver moieties coupled with ordered mesoporous cobalt oxide towards electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 16544–16552 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.202003801

Q. Chen, K. Liu, Y. Zhou, X. Wang, K. Wu et al., Ordered Ag nanoneedle arrays with enhanced electrocatalytic CO2 reduction via structure-induced inhibition of hydrogen evolution. Nano Lett. 22, 6276–6284 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c01853

S.A. Chala, M.C. Tsai, W.N. Su, K.B. Ibrahim, B. Thirumalraj et al., Hierarchical 3D architectured Ag nanowires shelled with NiMn-layered double hydroxide as an efficient bifunctional oxygen electrocatalyst. ACS Nano 14, 1770–1782 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.9b07487

Z. Zhang, X. Li, C. Zhong, N. Zhao, Y. Deng et al., Spontaneous synthesis of silver-nanoparticle-decorated transition-metal hydroxides for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 7245–7250 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202001703

R. Gao, Z. Yang, L. Zheng, L. Gu, L. Liu et al., Enhancing the catalytic activity of Co3O4 for Li–O2 batteries through the synergy of surface/interface/doping engineering. ACS Catal. 8, 1955–1963 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.7b03566

H. Wu, F. Huang, J. Peng, Y. Cao, High-efficiency electron injection cathode of Au for polymer light-emitting devices. Org. Electron. 6, 118–128 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgel.2005.03.009

A.W. Dweydari, C.H.B. Mee, Work function measurements on (100) and (110) surfaces of silver. Phys. Status Solidi 27, 223–230 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1002/pssa.2210270126

Z. Yu, Z. Yang, Z. Ni, Y. Shao, B. Chen et al., Simplified interconnection structure based on C60/SnO2-x for all-perovskite tandem solar cells. Nat. Energy 5, 657–665 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-020-0657-y

H. Yang, Q. Lin, C. Zhang, X. Yu, Z. Cheng et al., Carbon dioxide electroreduction on single-atom nickel decorated carbon membranes with industry compatible current densities. Nat. Commun. 11, 593 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14402-0

S. Liu, X.F. Lu, J. Xiao, X. Wang, X.W.D. Lou, Bi2O3 nanosheets grown on multi-channel carbon matrix to catalyze efficient CO2 electroreduction to HCOOH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 13828–13833 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.201907674

P. Zhu, H. Wang, High-purity and high-concentration liquid fuels through CO2 electroreduction. Nat. Catal. 4, 943–951 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-021-00694-y

A. Manthiram, X. Yu, S. Wang, Lithium battery chemistries enabled by solid-state electrolytes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16103 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/natrevmats.2016.103

L. Fan, S. Wei, S. Li, Q. Li, Y. Lu, Recent progress of the solid-state electrolytes for high-energy metal-based batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702657 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201702657

N. Han, Y. Wang, J. Deng, J. Zhou, Y. Wu et al., Self-templated synthesis of hierarchical mesoporous SnO2 nanosheets for selective CO2 reduction. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 1267–1272 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8TA10959A

G. Kresse, J. Furthmüller, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Comp. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.47.558

G. Kresse, J. Hafner, Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.47.558

P.E. Blöchl, Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953

J.P. Perdew, K. Burke, M. Ernzerhof, Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865

L. Zhang, W. Cai, N. Bao, H. Yang, Implanting an electron donor to enlarge the d-p hybridization of high-entropy (oxy)hydroxide: a novel design to boost oxygen evolution. Adv. Mater. 34, e2110511 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202110511

P. Wang, M. Qiao, Q. Shao, Y. Pi, X. Zhu et al., Phase and structure engineering of copper tin heterostructures for efficient electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction. Nat. Commun. 9, 4933 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07419-z

Q. Wang, K. Liu, K. Hu, C. Cai, H. Li et al., Attenuating metal-substrate conjugation in atomically dispersed nickel catalysts for electroreduction of CO2 to CO. Nat. Commun. 13, 6082 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33692-0

Y. Wang, C. Wang, Y. Wei, F. Wei, L. Kong et al., Efficient and selective electroreduction of CO2 to HCOOH over Bismuth-based bromide perovskites in acidic electrolytes. Chem. Eur. J. 28, e202201832 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.202201832

J. Hao, Z. Zhuang, J. Hao, K. Cao, Y. Hu et al., Strain relaxation in metal alloy catalysts steers the product selectivity of electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. ACS Nano 16, 3251–3263 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.1c11145

L. Fan, C. Xia, P. Zhu, Y. Lu, H. Wang, Electrochemical CO2 reduction to high-concentration pure formic acid solutions in an all-solid-state reactor. Nat. Commun. 11, 3633 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17403-1

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported from the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (Grant No. 52125103), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52301232, 52071041, 12074048, and 12147102), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2022M720552). The authors would like to thank the Analytical and Testing Center of Chongqing University for the assistance with the sample characterization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no interest conflict. They have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, M., Cao, A., Xiang, Y. et al. Strongly Coupled Ag/Sn–SnO2 Nanosheets Toward CO2 Electroreduction to Pure HCOOH Solutions at Ampere-Level Current. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 50 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01264-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01264-6