Highlights

-

SnO2-Co-carbon nanocomposites were in-situ prepared from Co-based metal–organic frameworks and showed a remarkably high initial Coulombic efficiency (82.2%) and a capacity of ~ 800 mAh g−1 at a high current density of 5 A g−1.

-

Facile approach for designing highly reversible and stable electrodes for next-generation high-performance lithium-ion batteries.

Abstract

The two major limitations in the application of SnO2 for lithium-ion battery (LIB) anodes are the large volume variations of SnO2 during repeated lithiation/delithiation processes and a large irreversible capacity loss during the first cycle, which can lead to a rapid capacity fade and unsatisfactory initial Coulombic efficiency (ICE). To overcome these limitations, we developed composites of ultrafine SnO2 nanoparticles and in situ formed Co(CoSn) nanocrystals embedded in an N-doped carbon matrix using a Co-based metal–organic framework (ZIF-67). The formed Co additives and structural advantages of the carbon-confined SnO2/Co nanocomposite effectively inhibited Sn coarsening in the lithiated SnO2 and mitigated its structural degradation while facilitating fast electronic transport and facile ionic diffusion. As a result, the electrodes demonstrated high ICE (82.2%), outstanding rate capability (~ 800 mAh g−1 at a high current density of 5 A g−1), and long-term cycling stability (~ 760 mAh g−1 after 400 cycles at a current density of 0.5 A g−1). This study will be helpful in developing high-performance Si (Sn)-based oxide, Sn/Sb-based sulfide, or selenide electrodes for LIBs. In addition, some metal organic frameworks similar to ZIF-67 can also be used as composite templates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the past few years, the applications of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have extended from consumer electronics to power batteries. This impressive progress achieved in this field suggests that LIBs will continue to be a dominant power source for electric vehicles in the next decade [1]. In the pursuit of further improvement of LIBs, various efforts have been made to rationalize their design and to develop advanced electrode materials with high specific capacity, prolonged life span, and good rate capability [2, 3]. Graphite is the most widely used LIB anode. However, it exhibits a limited specific capacity of 372 mAh g−1. Therefore, in 2011, Sony Corporation produced novel LIBs (Nexelion). Specifically, their anodes consisted of Sn-Co–C composites. Various tin-based anodes have also been fabricated in order to develop high-performance LIBs [2,3,4]. Among these anodes, tin oxide (SnO2) anodes have been extensively studied because SnO2 can store Li+ via a two-step reaction and shows a high theoretical specific capacity of 1494 mAh g−1. In the Li+ storage of SnO2, the first step is the conversion reaction (SnO2 + 4Li → Sn + 2Li2O), which generates a capacity of 731 mAh g−1. In the subsequent lithiation/delithiation process, an alloying reaction (Sn + 4.4Li → Li4.4Sn) occurs, delivering a capacity of 763 mAh g−1 [6,7,8]. However, there are two major challenges in developing SnO2 anodes with a high specific capacity: (i) capacity loss induced by the huge volume variations (greater than 300%) generated during cycling, (ii) the irreversibility of the conversion reaction, which reduces the initial Coulombic efficiency (ICE) of the anode [5,6,7].

Various attempts have been made to overcome these limitations. For example, various carbon-based SnO2 composites have been developed to accommodate the volume expansions caused by cycling in order to achieve cycling stability [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. However, this carbon composite approach cannot improve the ICE of SnO2 anodes. Hu et al. reported that SnO2 electrodes with Sn grains < 11 nm in diameter show a completely reversible conversion reaction (Sn + Li2O → SnO2) [19]. Transition metals (M = Cu, Fe, Mn, Co, etc.) or metal oxides are used to stabilize nanostructured SnO2 and can also improve the reversibility of the conversion reaction between Li2O and SnO2 [4, 20,21,22,23,24,25]. Inactive metals can buffer the expansion of Sn particles (to coarsen them) and migrate to the Sn/Li2O surface so that Sn can remain active with Li2O. Thus, the introduction of transition metals can improve the ICE of SnO2 electrodes. To sum up, there are mainly three mainstream solutions for developing high-performance SnO2-based anodes: (1) designing a unique carbon-based structure including the surface coating to suppress the full volume expansions [26, 27] while providing an expansion space [8, 28,29,30,31], (2) preparing ultrafine SnO2 nanoparticles to aggrandize the grain boundaries and alleviate the mechanical strain and improve the reversibility of the conversion reaction [6], and (3) introducing transition metals or forming intermetallic alloys to make the conversion reaction reversible and mitigate the expansion of Sn simultaneously [4, 20,21,22,23].

Recently, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) with inorganic (Co and Zn) and organic molecules have been used as a novel 3D porous carbon source for developing adjustable templates to anchor guest transition metals [32,33,34]. In this study, we fabricated a novel ternary SnO2-Co-C composite by mixing ultrafine SnO2 nanoparticles with a Co-based MOF (ZIF-67) (denoted as N-u-SCC) to develop LIB anodes with high ICE and long-term cycle stability. ZIF-67 serves as a sacrificial template for the formation of Co additives and 3D porous carbon frameworks. This well-designed structure showed the advantages of the unique 3D carbon-based nanostructure with in situ formed Co additives and suppressed the volume expansions and Sn coarsening of the lithiated SnO2. This improved the cycling performance of the anodes and rendered the conversion reaction highly reversible. The 3D porous carbon framework served as an excellent carrier for SnO2 (to be anchored) and improved the conductivity of the entire composite while providing enough space for volume variations during the lithiation/delithiation process. The in situ formed Co additives not only prevented the covering of SnO2 by Li2O and alleviated the volume expansions, but also served as good electron conductors. As a result, the N-u-SCC-2 electrode showed a high ICE of 82.2% (average level). In addition, the electrodes showed extraordinary specific capacity (~ 975 mAh g−1 after 100 cycles at 0.2 A g−1), high capacity retention (78.6% after 100 cycles at 0.2 A g−1), excellent rate capability (a reversible capacity of ~ 800 mAh g−1 under the current density of 5 A g−1), and prolonged life span.

2 Experimental Section

All the chemicals used in this work were analytically pure and were commercially available. Commercial SnO2 and Co(NO3)2·6H2O, 2-methylimidazole were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co. Ltd. Na2SnO3 and urea were purchased from Xilong Scientific.

2.1 Synthesis of Ultrafine SnO2

Ultrafine SnO2 was prepared by modifying the method reported by Lou et al. [3]. In a typical reaction, 2.5 mmol of NaSnO3·4H2O and 16 mmol of urea were added into a solution of 145 mL of H2O and 15 mL of ethanol and the resulting mixture was stirred for 1 h. The reaction mixture was then transferred to a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave, which was heated in an oven at 190 °C for 15 h. The reaction mixture was centrifuged to obtain precipitates, which were dried at 80 °C overnight and annealed at 550 °C for 4 h.

2.2 Synthesis of ZIF-67 Frameworks

ZIF-67 frameworks were prepared by a simple liquid-phase method. Certain amounts of Co(NO3)2·6H2O (listed in Tables 1 and S1) (A) and 2-methylimidazole (B) were separately added into equal proportions of a methanol/ethanol solution under stirring, and the resulting solutions were labeled as solutions A and B, respectively. Solution B was quickly added to solution A, and the resulting mixture was vigorously stirred for another 3 min. The reaction mixture was then static aged for 22 h [33]. Precipitates were separated from the solution by centrifugation and were freeze-dried and then annealed at 550 °C for 2 h.

2.3 Synthesis of N-c-SCC and N-u-SCC Composites

The N-doped commercial SnO2-Co-C (denoted as N-c-SCC) and N-u-SCC composites were prepared using a method similar to that used for the preparation of the ZIF-67 frameworks. The only difference was that 0.2 g of SnO2 (commercial or ultrafine) was added into solution A followed by sonication for 0.5 h. After the sonication, solution A was stirred for another 10 min for better dispersion. Then, solution B was quickly added to solution A and the resulting mixture was stirred vigorously for another 3 min. The reaction mixture was then static aged for 22 h. The precipitates separated from the solution by centrifugation were freeze-dried and then annealed at 550 °C for 2 h.

2.4 Material Characterization

The morphology of the as-prepared samples was examined by a SUPRA 55 field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) examinations were carried out on a JEOL JEM 2100F at 200 kV. The elemental mapping and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) measurements of the samples were taken on an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer equipped with the JEOL 2100F microscope. The powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the samples were recorded on a Rigaku Ultima IV with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was carried out using an Axis Ultra DLD spectrometer.

2.5 Electrochemical Measurements

The electrochemical performance of the as-prepared composites was evaluated using R2032 coin-type half cells assembled in a glove box filled with argon. The oxygen and moisture contents of the glove box were < 0.5 ppm. The electrodes were prepared by confecting a slurry containing the active materials, carbon black, and carboxymethyl cellulose with a ratio of 7:2:1 in a solution of water and ethanol. This slurry solution was stirred for 8 h and was then casted onto a Cu foil and dried at 80 °C for 12 h under vacuum. The active material loading on each electrode was 0.9–1.1 mg. A solution of 1 M LiPF6 in ethylene carbonate and diethyl carbonate (at a volume ratio of 1:2) containing 10 wt% fluoroethylene carbonate (FEC) was used as the electrolyte. The electrochemical measurements of the electrodes were taken using a Neware battery tester over the potential range of 0.01–3.0 V. The specific capacity of the composites was calculated using their whole masses. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements were taken on an electrochemical workstation (CHI 660C) over the voltage range of 0.01–3 V at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1.

3 Results and Discussion

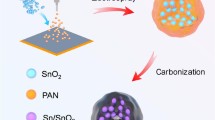

Figure 1 shows the schematic of the synthesis of N-u-SCC. The as-prepared ultrafine SnO2 nanoparticles and Co(NO3)2·6H2O were uniformly dispersed in an alcoholic solution. To this solution, an alcoholic solution of 2-methylimidazole (2-Melm) was added to generate the SnO2@ZIF-67 composite. After annealing under an inert atmosphere, ZIF-67 carbonized and its structure collapsed. This eventually resulted in the formation of carbon frameworks with metallic Co. We also prepared composites using commercial SnO2. For this, commercial SnO2 was added to the alcoholic solution during the synthesis of ZIF-67. The reaction mixture was then heat-treated under an inert atmosphere to finally obtain the in situ formed N-c-SCC. Table S1 lists the synthetic formulae and ICE values of the three N-c-SCC electrodes. The morphology of commercial SnO2 and the three N-c-SCC composites is shown in Fig. S1.

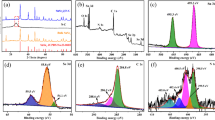

The phase composition of the samples was analyzed using their XRD patterns. The XRD patterns shown in Fig. 2a reveal that SnO2 (JCPDS No. 77-0447) was the main phase of all the three samples. With an increase in the carbon content, the CoSn phase of the samples became predominant. No other impurity was detected. Figure 2b shows the ICE of the pure commercial SnO2 and N-c-SCC electrodes. The N-c-SCC electrodes showed better electrochemical performance than the pure commercial SnO2 electrode. The ICE of the N-c-SCC electrodes increased from 62.6 to 72.5%. This is because Co nanoparticles improved the reversibility of the conversion reaction on SnO2. Taking the variate into consideration, this remarkable improvement in the ICE of the N-c-SCC electrodes was due to the ZIF-67 frameworks, which consisted only of Co and carbon. This demonstrates the viability of our design, in which ZIF-67 was used as the sacrificial template. To further evaluate the electrochemical performance of the four electrodes, their charge–discharge curves were plotted, as shown in Fig. S2. The charging potential of all the SnO2 electrodes could be divided into three regions, each of which involved different reaction processes. Similarly, the capacity of the electrodes in each cycle could be divided into three parts: 0.01–1.0 V corresponding to the dealloying reaction (LixSn → Sn), 1.0–2.4 V corresponding to the conversion reaction (Sn → SnO2), and 2.4–3.0 V corresponding to some other reactions like the consumption of the electrolyte [25]. On the basis of the electrochemical measurements and morphological analysis of the electrodes, it can be stated that (1) the contact area between Co and SnO2 significantly improves the reversibility of the conversion reaction. At the N-u-SCC-1, the highest capacity was observed in all the cycles over the potential range of 1.0–2.4 V. (2) An increase in the carbon content improved the reversibility of the conversion reaction and the cycling stability of the electrodes. Figure S2 reveals that the N-c-SCC-3 electrode showed the best cycling stability.

To further optimize the electrochemical performance of the SnO2 electrodes, commercial SnO2 was substituted by the as-prepared ultrafine SnO2 nanoparticles (~ 15 nm). The N-doped ultrafine SnO2-Co-C composites (denoted as N-u-SCC) were prepared using a method same as that used for preparing the N-c-SCC composites. Table 1 lists the synthetic formulae, carbon contents, and Sn and Co weight ratios of the two N-u-SCC composites. The morphology of the ultrafine SnO2 nanoparticles and N-u-SCC-1 and N-u-SCC-2 electrodes was observed. Figure 3a, d shows that the ultrafine SnO2 nanoparticles had a diameter of ~ 15 nm and were evenly distributed in the composites. The morphology and diameter of the frameworks of N-u-SCC-1 (Figs. 3b, e) were similar to those shown in Fig. S1c. This can be attributed to the same Co(NO3)2·6H2O/2-Melm ratio (1:8) in both the cases. Since the ultrafine SnO2 particles were much smaller than commercial SnO2 particles, they offered a larger contact area with metallic Co. At the Co(NO3)2·6H2O/2-Melm ratio of 1:16, the frameworks became less stable and could be hardly observed. However, carbon was predominant, as shown in Fig. 3c, f.

The morphology of the N-u-SCC-2 composite was further analyzed by TEM. Figure 4a shows a typical TEM image of the as- prepared N-u-SCC-2 composite. It can be observed that the carbon frameworks consisted of SnO2 and Co (CoSn) nanoparticles (light zone), which alleviated the volume variations during the subsequent deintercalation reactions. The sufficient contact area between SnO2 and Co (CoSn) improved the reversibility of the conversion reaction, thus improving the ICE and cycling performance of the electrode. The lattice distances of 0.32 and 0.24 nm (Fig. 4b) correspond to the (110) and (200) planes of crystalline SnO2. The lattice distance of 0.22 nm corresponds to the (111) lattice plane of CoSn. The lattice distances of Sn could not be detected. This can be attributed to the low Sn content of the nanocomposite and the similarity in the lattice distances of Sn and SnO2. Figure 4c shows the elemental mapping of the N-u-SCC-2 composite under ultrahigh magnification. This figure confirms that Sn and Co were uniformly distributed in the carbon frameworks and showed sufficient contact. The Sn and Co weight ratios of N-u-SCC-2 were about 50.8% and 11.2%, respectively, while those of N-u-SCC-1 were 51.5% and 25.1%, respectively, as revealed by the EDS results (Table S2).

The phase composition of the ultrafine SnO2 particles and N-u-SCC-1 (SnO2-ratio 1 in Fig. 5a) and N-u-SCC-2 composites (SnO2-ratio 2 in Fig. 5a) was analyzed using their XRD patterns. The XRD peaks of ultrafine SnO2 could be indexed to JCPDS No. 77-0447. Like commercial SnO2, both N-u-SCC-1 and N-u-SCC-2 consisted of the CoSn phase, which was formed during the annealing process. This confirms the presence of Co in these composites. It should be noted that N-u-SCC-2 showed the Sn metal phase (Fig. 5a). This can be attributed to its stronger reduction capability owing to its higher carbon content (according to the EDS results; Tables 1 and S2). N-u-SCC-1 consisted mainly of the SnO2 phase with little CoSn. N-u-SCC-2 also consisted of SnO2 as the main phase with small fractions of the Sn and CoSn phases. In these composites, Co mainly existed as the CoSn phase. Figure 5b compares the ICE values of the N-u-SCC electrodes. The N-u-SCC-2 electrode showed the highest ICE value of about 82.2% (Fig. S4). N-u-SCC-2 showed a higher ICE than N-u-SCC-1 because of its larger Sn/Co contact area, as revealed by the FESEM images.

The valence states of Sn and Co in the N-u-SCC-2 composite were analyzed by XPS. As can be observed from Fig. 5c, Sn showed a main valence of Sn4+. This is consistent with the observation that SnO2 was the main phase of this composite. In addition, some Sn present on the surface showed a valence of zero. This can be attributed to the reduction of metallic Sn by carbon and Co during the annealing process (as observed from the XRD patterns). Oxygen vacancies were generated at this point. The Co 2p spectra (Fig. 5d) of the near-surface region of the composite showed three types of valence (Co, CoO, and Co2O3). The increasing valence could be assigned to the oxidation of metallic Co. The small amount of oxidation in the near surface of the composite could not be detected by XRD. Figure 5e, f shows the N 1s and C 1s spectra of the N-u-SCC-2 composite and confirms the presence of N and C in it. Moreover, the high-resolution N 1s XPS spectra showed that the composite consisted of pyridinic N (398.7 eV) and pyrrolic N (400.5 eV) (Fig. S5). The pyridinic N and pyrrolic N contents of this composite were 80.3% and 19.7%, respectively (Fig. S5). These results indicate the N-doped C composite SnO2 was the main active phase of the N-u-SCC-2 composite.

Figure 6a shows the CV curves of the N-u-SCC-2 electrode. The peak observed at ~ 0.87 V during the first cycle can be attributed to the reduction of SnO2 to metallic Sn or SnO and the formation of solid–electrolyte interface (SEI) layers, which accounted for the disappearing of this peak in the subsequent cycles. The relatively large area of this peak indicates that a large amount of reaction/layer was formed. The peaks observed at around 0.3 and 0.2 V in the subsequent cycles correspond to a series of Li–Sn alloying reactions. The anodic peaks at 0.50, 0.61, 0.73, and 0.78 V can be attributed to the LixSn → Sn dealloying reactions. This is consistent with the differential charge capacity versus voltage curves obtained in the subsequent cycles. The broad peaks at 1.25 and 2.06 V correspond to the reversible oxidation of metallic Sn to SnO and SnO2, respectively. The peaks remained stable and could be clearly observed during the 4th cycle, demonstrating the high reversibility of the conversion reactions. After the first cycle, the curves showed similar peak patterns, indicating that the stability of the electrode increased gradually. Figure 6b shows the first three discharge/charge curves of the N-u-SCC-2 electrode at a current density of 0.2 A g−1. The initial discharge capacity of the electrode was 1365.2 mAh g−1. Similar curves were obtained in the subsequent cycles. This attests the high ICE and excellent cycling performance of the electrode. For unveiling the reversible nature of the conversion reaction, the differential charge capacity versus voltage curves of the N-u-SCC-2 electrode at the 1st, 10th, 50th, and 100th cycles were obtained (Fig. 6c). The peaks observed over the potential range of 0.01–1.0 V correspond to the dealloying reactions (LixSn to Sn), while the peaks at 1.0 to − 2.4 V correspond to the conversion reactions (Sn to SnO or SnO2) after 100 cycles. The peaks (integral intensities and potential positions) corresponding to the conversion reactions remained the same (1st and 2nd cycles) even after the 50th cycle. These results demonstrate the high reversibility of the conversion reaction.

a CV curves of the N-u-SCC-2 electrode over the potential range of 0.01–3 V. b First three discharge/charge curves of the N-u-SCC-2 electrode at a current density of 0.2 A g−1. c Differential charge capacity vs. voltage curves of the N-u-SCC-2 electrode during the 1st, 10th, 50th, and 100th cycles. d Galvanostatic charge–discharge cycle of the N-u-SCC-2 electrode at a current density of 0.2 A g−1. e Cycling performance of the N-u-SCC-2 electrode at a current density of 0.5 A g−1

The N-u-SCC-2 electrode showed a reversible discharge capacity of ~ 975 mAh g−1 after 100 cycles (Fig. 6d) at a current density of 0.2 A g−1, which corresponds to a capacity retention ratio of 78.6% (when compared with the 2nd cycle). On the other hand, the N-u-SCC-1 and pure SnO2 electrodes exhibited much smaller reversible discharge capacities of 504 and 226.0 mAh g−1, respectively, after 100 cycles. The first discharge capacities of the N-u-SCC-2, N-u-SCC-1, and pure SnO2 electrodes were 1365.2, 990.5, and 1736.7 mAh g−1, respectively. This high capacity retention of the N-u-SCC-2 electrode can be attributed to its high carbon content, which provided more space for volume variations along with a larger Sn/Co contact area to inhibit the volume expansion, thus increasing the cycling life of the electrode. It should be noted that the N-u-SCC-2 electrode showed an average ICE of 82.2% because of the formation of SEI layers. This improved the reversibility of the reactions between SnO2 and Li. On the other hand, the N-u-SCC-1 and pure SnO2 electrodes showed an ICE of 68.1% and 59.7%, respectively (Fig. S6). The N-u-SCC-2 electrode exhibited smaller internal resistance than the other two electrodes, as revealed by the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements shown in Fig. S7a. The EIS measurements of the N-u-SCC-2 electrode after 100 cycles were also taken. An equivalent circuit consisting of the resistances of the electrolyte (Re), charge transfer (Rct), and constant phase elements and Warburg impedance was proposed to fit the impedance data. Low Rct values were obtained after 100 cycles (179–32 Ω), suggesting the enhanced charge transfer kinetics (Table S4). In addition, the N-u-SCC-2 electrode showed excellent rate capability. Figure S8a shows the discharge/charge curves of the electrode at different current densities. All the curves showed similar trend with the same discharge/charge platform. Furthermore, a reversible capacity of ~ 800 mAh g−1 was obtained when the current density was increased to 5 A g−1. At the current densities of 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 A g−1, discharge capacities of ~ 1500, 1240, 1090, 965, and 800 mAh g−1, respectively, were obtained. As the current returned to 0.2 A g−1, the capacity became stable, as shown in Fig. S8b. This extraordinary rate capability of N-u-SCC-2 was not due to its unique nanostructure consisting only of Co and carbon framework, but can be attributed to the oxygen vacancies, which improved the conductivity and transportation of Li+ [28, 31, 35,36,37,38,39,40]. The N-u-SCC-2 electrode exhibited a cycling life of up to 450 cycles and maintained a reversible capacity of ~ 760 mAh g−1 at the current density of 0.5 A g−1, as shown in Fig. 6e. After 150 cycles, the diffusion kinetics of lithium ions improved after the initial activation. The optimization of the SEI layer at the initial stage leads to capacity fading because of its breakdown and reconstruction. The cycling performance of an electrode improves after the formation of a stable SEI layer. The long-term cycling performance of the N-u-SCC-2 electrodes at relatively high current densities of 1 A g−1 for 200 cycles and 2 A g−1 for 300 cycles was also evaluated, as shown in Fig. S9. As can be observed from the figure, the electrode exhibited a desirable long-term cycling performance.

We also compared the ICE of the N-u-SCC-2 anode with that of previously reported SnO2/C LIB anodes. (Materials for LIBs are listed in Table S3.) The N-u-SCC-2 anode showed the highest ICE and outstanding electrochemical properties. Figure 7 shows the schematic of the delithiation process of pure SnO2, SnO2/C, and N-u-SCC electrodes. As shown in Fig. 7a, after lithiation, SnO2 particles became larger and the distances between them decreased. This resulted in the gradual agglomeration of SnO2 nanoparticles, leading to poor cycling life and low ICE of the electrode. Upon the incorporation of carbon materials like graphene and 3D frameworks (Fig. 7b), these SnO2 particles scattered and became more dispersive in the original state after being coated with carbon. The introduced carbon materials suppressed the volume variations of SnO2 particles during lithiation, provided extra space for volume variations, and served as barriers to prevent the aggregation of SnO2 particles so that the particles were still dispersive after delithiation. Similarly, the N-u-SCC-2 composite consisted of 3D carbon frameworks, which prevented the aggregation and volume variations of SnO2 particles during lithiation. However, the 3D carbon frameworks in this composite consisted of uniformly distributed Co (CoSn) particles. Co does not participate in the delithiation reactions and remains stable. This makes Co a powerful barrier to prevent the volume variations and particle agglomeration of SnO2. Thus, the exquisitely designed N-u-SCC-2 composite showed extraordinary electrochemical properties. Figure S10 shows the FESEM images of the ultrafine SnO2 particles and N-u-SCC-2 composites after 100 cycles. Pure SnO2 grains showed severe aggregation (Fig. S10b), while N-u-SCC-2 exhibited little aggregation and a morphology similar to that observed initially (Fig. S10d). Figure S10e, f shows the TEM images of the original N-u-SCC-2 and N-u-SCC-2 electrodes after discharging to 1.0 V. The morphology remained the same except that the latter became amorphous. These observations demonstrate the potential of the N-u-SCC-2 composite for application as an LIB anode.

4 Conclusion

In summary, a novel ternary SnO2-Co-C nanocomposite (N-u-SCC) was successfully prepared via a simple and low-cost synthesis method. In this design, the in situ formation of Co additives from the Co-based ZIF-67 framework rendered the SnO2 conversion reaction highly reversible and the N-doped carbon frameworks efficiently mitigated the structural degradation of SnO2 while facilitating electronic transport and ionic diffusion. Accordingly, the optimized N-u-SCC electrodes exhibited excellent electrochemical performance with high ICE (average 82.2%), outstanding rate performance (800 mAh g−1 at 5 A g−1), and long-term cycling performance (~ 760 mAh g−1 after 400 cycles at a current density of 0.5 A g−1). These findings will be helpful for developing highly reversible and stable electrodes for next-generation high-performance LIBs.

References

Global EV Outlook 2018, International Energy Agency. https://www.iea.org/gevo2018/

J.S. Chen, X.W. Lou, SnO2-based nanomaterials: synthesis and application in lithium-ion batteries. Small 9(11), 1877–1893 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201202601

X.W. Lou, Y. Wang, C. Yuan, J.Y. Lee, L.A. Archer, Template-free synthesis of SnO2 hollow nanostructures with high lithium storage capacity. Adv. Mater. 18(17), 2325–2329 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.200600733

Y.F. Deng, C.C. Fang, G.H. Chen, The developments of SnO2/graphene nanocomposites as anode materials for high performance lithium ion batteries: a review. J. Power Sources 304, 81–101 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2015.11.017

D.H. Liu, F. Xie, J. Lyu, T.K. Zhao, T.H. Li, B.G. Choi, Tin-based anode materials with well-designed architectures for next generation lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 321, 11–35 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.04.105

Y. Idota, T. Kubota, A. Matsufuji, Y. Maekawa, T.M. Iyasaka, Tin-based amorphous oxides: a high-capacity lithium-ion-storage material. Science 276(5317), 1395–1697 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.276.5317.1395

J.Y. Huang, Z. Li, C.M. Wang, J.P. Sullivan, S.X. Mao, N.S. Hudak et al., In situ observation of the electrochemical lithiation of a single SnO2 nanowire electrode. Science 330(6010), 1515–1519 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1195628

X. Hu, G. Wang, B. Wang, X. Liu, H. Wang, Co3Sn2/SnO2 heterostructures building double shell micro-cubes wrapped in three-dimensional graphene matrix as promising anode materials for lithium-ion and sodium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 355, 986–998 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.07.173

X. Zhou, L.J. Wan, Y.G. Guo, Binding SnO2 nanocrystals in nitrogen-doped graphene sheets as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 25(15), 2152–2157 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201300071

W. Ai, Z. Huang, L. Wu, Z. Du, C. Zou, Z. He, R. Shahbazian-Yassar, W. Huang, T. Yu, High-rate, long cycle-life Li-ion battery anodes enabled by ultrasmall tin-based nanoparticles encapsulation. Energy Storage Mater. 14, 169–178 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2018.02.008

R. Hu, D. Chen, G. Waller, Y. Ouyang, Y. Chen et al., Dramatically enhanced reversibility of Li2O in SnO2-based electrodes: the effect of nanostructure on high initial reversible capacity. Energy Environ. Sci. 9(2), 595–603 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/C5EE03367E

L. Zhang, H.B. Wu, B. Liu, X.W. Lou, Formation of porous SnO2 microboxes via selective leaching for highly reversible lithium storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 7(3), 1013–1017 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ee43305f

W. Dong, J. Xu, C. Wang, Y. Lu, X. Liu et al., A robust and conductive black tin oxide nanostructure makes efficient lithium-ion batteries possible. Adv. Mater. 29(24), 1700136 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201700136

C. Miao, M. Liu, Y.-B. He, X. Qin, L. Tang et al., Monodispersed SnO2 nanospheres embedded in framework of graphene and porous carbon as anode for lithium ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 3, 98–105 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2016.01.006

L.P. Wang, Y. Leconte, Z. Feng, C. Wei, Y. Zhao et al., Novel preparation of N-doped SnO2 nanoparticles via laser-assisted pyrolysis: demonstration of exceptional lithium storage properties. Adv. Mater. 29(6), 1603286 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201603286

J. Han, D. Kong, W. Lv, D.M. Tang, D. Han et al., Caging tin oxide in three-dimensional graphene networks for superior volumetric lithium storage. Nat. Commun. 9(1), 402 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02808-2

J. Liang, C. Yuan, H. Li, K. Fan, Z. Wei, H. Sun, J. Ma, Growth of SnO2 nanoflowers on N-doped carbon nanofibers as anode for Li- and Na-ion batteries. Nano-MICRO Lett. 10, 21 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-017-0172-2

B. Jiang, Y. He, B. Li, S. Zhao, S. Wang, Y.B. He, Z. Lin, Polymer-templated formation of polydopamine-coated SnO2 nanocrystals: anodes for cyclable lithium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56(7), 1869–1872 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201611160

D. Zhou, W.L. Song, L.Z. Fan, Hollow core-shell SnO2/C fibers as highly stable anodes for lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7(38), 21472–21478 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.5b06512

X. Zhou, L. Yu, X.W. Lou, Formation of uniform n-doped carbon-coated SnO2 submicroboxes with enhanced lithium storage properties. Adv. Energy Mater. 6(14), 1600451 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201600451

L. Xia, S. Wang, G. Liu, L. Ding, D. Li, H. Wang, S. Qiao, Flexible SnO2/N-doped carbon nanofiber films as integrated electrodes for lithium-ion batteries with superior rate capacity and long cycle life. Small 12(7), 853–859 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201503315

L. Zu, Q. Su, F. Zhu, B. Chen, H. Lu, Antipulverization electrode based on low-carbon triple-shelled superstructures for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 29(34), 1701494 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201701494

R. Huang, L.J. Wang, Q. Zhang, Z. Li, D.Y. Pan, B. Zhao, M.H. Wu et al., Irradiated graphene loaded with SnO2 quantum dots for energy storage. ACS Nano 9(11), 11351–11361 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.5b05146

R. Hu, H. Zhang, Z. Lu, J. Liu, M. Zeng, L. Yang, B. Yuan, M. Zhu, Unveiling critical size of coarsened Sn nanograins for achieving high round-trip efficiency of reversible conversion reaction in lithiated SnO2 nanocrystals. Nano Energy 45, 255–265 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.01.007

R. Hu, Y. Ouyang, T. Liang, X. Tang, B. Yuan, J. Liu, L. Zhang, L. Yang, M. Zhu, Inhibiting grain coarsening and inducing oxygen vacancies: the roles of Mn in achieving a highly reversible conversion reaction and a long life SnO2–Mn-graphite ternary anode. Energy Environ. Sci. 10(9), 2017–2029 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/C7EE01635B

R. Hu, Y. Ouyang, T. Liang, H. Wang, J. Liu, J. Chen, C. Yang, L. Yang, M. Zhu, Stabilizing the nanostructure of SnO2 anodes by transition metals: a route to achieve high initial coulombic efficiency and stable capacities for lithium storage. Adv. Mater. 29(13), 1605006 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201605006

J. Huang, Y. Ma, Q. Xie, H. Zheng, J. Yang, L. Wang, D.L. Peng, 3D graphene encapsulated hollow CoSnO3 nanoboxes as a high initial coulombic efficiency and lithium storage capacity anode. Small 14(10), 1703513 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201703513

Q. He, J. Liu, Z. Li, Q. Li, L. Xu, B. Zhang, J. Meng, Y. Wu, L. Mai, Solvent-free synthesis of uniform MOF shell-derived carbon confined SnO2/Co nanocubes for highly reversible lithium storage. Small 13(37), 1701504 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201701504

J.W. Deng, C.L. Yan, C. Yang, S. Baunack, S. Oswald, H. Wendrock, Y.F. Mei, O.G. Schmidt, Sandwich-stacked SnO2/Cu hybrid nanosheets as multichannel anodes for lithium ion batteries. ACS Nano 7(8), 6948–6954 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1021/nn402164q

C. Kim, J.W. Jung, K.R. Yoon, D.Y. Youn, S. Park, I.D. Kim, A high-capacity and long-cycle-life lithium-ion battery anode architecture: silver nanoparticle-decorated SnO2/NiO nanotubes. ACS Nano 10(12), 11317–11326 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.6b06512

G. Ji, Y. Ma, B. Ding, J.Y. Lee, Improving the performance of high capacity Li-ion anode materials by lithium titanate surface coating. Chem. Mater. 24(17), 3329–3334 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1021/cm301432w

H. Zhang, Z. Chen, R. Hu, J. Liu, J. Cui, W. Zhou, C. Yang, Enabling a highly reversible conversion reaction in a lithiated nano-SnO2 film coated with Al2O3 by atomic layer deposition. J. Mater. Chem. A 6(10), 4374–4385 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8TA00290H

Y. Guo, X. Zeng, Y. Zhang, Z. Dai, H. Fan et al., Sn nanoparticles encapsulated in 3D nanoporous carbon derived from a metal-organic framework for anode material in lithium-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9(20), 17172–17177 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b04561

Q. Yu, P. Ge, Z. Liu, M. Xu, W. Yang, L. Zhou, D. Zhao, L. Mai, Ultrafine SiOx/C nanospheres and their pomegranate-like assemblies for high-performance lithium storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 6(30), 14903–14909 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/C8TA03987A

Z. Liu, D. Guan, Q. Yu, L. Xu, Z. Zhuang, T. Zhu, D. Zhao, L. Zhou, L. Mai, Monodisperse and homogeneous SiOx/C microspheres: a promising high-capacity and durable anode material for lithium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 13, 112–118 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2018.01.004

R. Jia, J. Yue, Q. Xia, J. Xu, X. Zhu, S. Sun, T. Zhai, H. Xia, Carbon shelled porous SnO2−δ nanosheet arrays as advanced anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 13, 303–311 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2018.02.009

T. Wang, H.K. Kim, Y. Liu, W. Li, J.T. Griffiths et al., Bottom-up formation of carbon-based structures with multilevel hierarchy from MOF-guest polyhedra. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140(19), 6130–6136 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.8b02411

T. Liu, W. Wang, M. Yi, Q. Chen, C. Xu, D. Cai, H. Zhan, Metal-organic framework derived porous ternary ZnCo2O4 nanoplate arrays grown on carbon cloth as binder-free electrodes for lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 354, 454–462 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.08.037

K. Wang, S. Pei, Z. He, L.A. Huang, S. Zhu, J. Guo, H. Shao, J. Wang, Synthesis of a novel porous silicon microsphere@carbon core-shell composite via in situ MOF coating for lithium ion battery anodes. Chem. Eng. J. 356, 272–281 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.09.027

Q. Xie, P. Liu, D. Zeng, W. Xu, L. Wang, Z.-Z. Zhu, L. Mai, D.-L. Peng, Dual electrostatic assembly of graphene encapsulated nanosheet-assembled ZnO–Mn–C hollow microspheres as a lithium ion battery anode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1707433 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201707433

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2016YFA0202602) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 21503178 and 21703185). We are grateful to Hongfei Zheng of Xiamen University for his technical support in transmission electron microscopy. This work is also supported by XMU Undergraduate Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Programs (Grants No. 2017X0695 for Huijiao Yang and Xiaocong Tang).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, P., Yang, J., Li, S. et al. High Initial Reversible Capacity and Long Life of Ternary SnO2-Co-carbon Nanocomposite Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 11, 18 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-019-0246-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-019-0246-4