Abstract

This paper was aimed to study the impact of climate change on the hydrology of Andasa watershed for the period 2013–2099. The soil and water assessment tool (SWAT) was calibrated and validated, and thereby used to study the impact of climate change on the water balance. The future climate change scenarios were developed using future climate outputs from the Hadley Center Climate Model version 3 (HadCM3) A2 (high) and B2 (low) emission scenarios and Canadian Earth System Model version 2 (CanESM2) Representative concentration pathways (RCP) 4.5 and 8.5 scenarios. The large-scale maximum/minimum temperature and rainfall data were downscaled to fine-scale resolution using the Statistical Downscaling Model (SDSM). The mean monthly temperature projection of the four scenarios indicated an increase by a range of 0.4–8.5 °C while the mean monthly rainfall showed both a decrease of up to 97% and an increase of up to 109%. The long-term mean of all the scenarios indicated an increasing temperature and decreasing rainfall trends. Simulations showed that climate change may cause substantial impacts in the hydrology of the watershed by increasing the potential evapotranspiration (PET) by 4.4–17.3% and decreasing streamflow and soil water by 48.8–95.6% and 12.7–76.8%, respectively. The findings suggested that climate change may cause moisture-constrained environments in the watershed, which may impact agricultural activities in the watershed. Appropriate agricultural water management interventions should be implemented to mitigate and adapt to the plausible impacts of climate change by conserving soil moisture and reducing evapotranspiration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water resources systems are described by the interactions of various interlinked components that yields numerous economic, environmental, ecological, and social Impacts (Loucks et al. 2005). Praskievicz and Chang (2009) reviewed land use/cover as one factor affecting the extent of climate change impact on hydrologic processes. The climate change effects on society and natural resources rest on the response of the hydrological cycle and further to warming (Marvel and Bonfil 2013). According to Trenberth et al. (2000), doubling of CO2 emission globally may expedite the hydrological cycle by 10% through changes in the evaporation and rainfall regime. Studies predict that the rainfall could decline by 10% by the mid-century in the south of the Sahara, which will cause water scarcity (Nyong 2005). Evidenced by historical data and climate projections, freshwater resources become vulnerable and highly affected due to climate change (Bates et al. 2008)

The forthcoming climate is often estimated using General Circulation Models (GCMs) considering different scenarios of greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions (Trenberth et al. 2000). GCMs are defined as the physical, chemical, and biological numerical representations of the climate system, and their interactions and feedback processes (IPCC 2013). The future plausible GHG emissions are represented and studied using scenarios (IPCC 2014), and most of these scenarios assume increasing GHG concentrations at global and regional levels (Wilby and Dawson 2007). GCMs are currently the most widely used tools for simulating the global climate system. However, the outputs from GCMs are too coarse and not in a form that can be used at a local scale. Therefore, the outputs from crude-scaled GCMs have to be downscaled to higher and finer spatial resolutions for localized applications. Although various downscaling methods are currently available, whenever cost and time effective study of local-level climate change impacts are needed, the statistical downscaling approach is the more encouraging option (Wilby and Dawson 2007). Likewise, the impacts of climate change are studied using hydrological models, which are developed to understand the relationship between climate and water resource systems (Xu 1999).

Two-third of the global population may become vulnerable to water availability due to climate change (Melese 2016). The severity of the impact has been worse on the hydrological systems of arid and semiarid Africa, where the water resource is highly sensitive to the climate system. For example, Melese (2016) reported that some Ethiopian rivers and lakes diminish in size and other streams may dry up due to climate change. Likewise, the impacts of local to global environmental changes on the hydrology of the Blue Nile basin were studied by several scholars (e.g., Beyene et al. 2009; Elshamy et al. 2009; Enyew et al. 2014; Dile et al. 2013).

Ethiopia has 12 major river basins with the total mean annual surface water potential of 122 Billion Metric Cube (BMC) (MoWR 2002). In addition, the recent best guesses for groundwater potential is between 12 and 30 BMC or more (MoWR and GW-MATE 2011). Although Ethiopia is considered as the water tower of East Africa, its water resources systems have very high spatial and temporal variability. However, the economy of Ethiopian is heavily reliant on agriculture, which supports 41% of the national income and 80% of the workforce (Diao et al. 2007). Since the Ethiopian economy is highly correlated to the hydrological variability and seasonality, several studies reported that the Ethiopian economy is vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and suggested implementing appropriate mitigation and adaptation measures to reduce climate change impact (World Bank 2006). However, the implementation of appropriate climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies requires a robust understanding of the impact of climate change on water resources. For example, although the Upper Blue Nile basin is one of the major water resources vital for Ethiopia and the region by supporting domestic, irrigation and hydropower generation, little research has been conducted to understand the impact of climate change on the hydrology of its sub-basins making sustainable water resources development difficult. This study, therefore, aims to analyze the impact of climate change on the hydrology on one of the sub-basins of the Upper Blue Nile basin called Andasa watershed. The study will predict climate change scenarios for temperature and rainfall in the watershed for the period 2013–2099, and thereby assess the impact of climate change on the river streamflow and other water balance components. The study used the Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) to study the hydrological impact of climate change. SWAT is a physically based model developed to estimate the impact of climate and land management practices on water, sediment and pollutants in watersheds with varying soils, land use, and management conditions (Neitsch et al. 2011).

Materials and methods

Study area

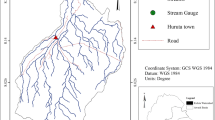

The case study was conducted in the Andasa watershed which is located in a headwater of the Upper Blue Nile in the Amhara region, Ethiopia (Fig. 1). The location of the watershed extends between 11°09′ and 11°33′N latitude, and 37°16′ and 37°28′E longitude. The elevation in the watershed ranges between 1700 and 3210 m above sea level (masl). The watershed is one of the major tributaries to the Upper Blue Nile River, and covers an area of 576 km2.

The mean annual temperature of the watershed is 20 °C and the average annual rainfall and streamflow of the watershed are 1370 mm and 9.5 m3/s, respectively. The livelihood for a large part of the population in the watershed is mainly through agricultural activities (Fig. 1).

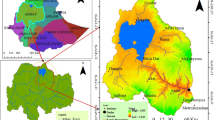

Spatial data

The spatial data used in this study include land use/cover (LULC), soil, and Digital Elevation Model (DEM). These data were used to setup and simulate a hydrological model that was used to study the impact of climate change. The LULC of the watershed was prepared using Landsat 8 satellite image based on a maximum likelihood supervised classification techniques. Supervised classification enhances the accuracy of the LULC classification since it is backed by prior knowledge about the study area (Yiqiang et al. 2010). The Landsat 8 satellite image was obtained from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/). A reference data for the supervised classification was collected using a random sampling technique. The analysis showed that subsistence rain-fed agriculture covers the majority (45%) of the watershed followed by cropland–woodland mosaic LULC type (35%) (Table 1; Fig. 2a). The spatial soil data were used in this study obtained from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO 1997) since it provides detailed chemical and physical properties of the soils available in the watershed. There were four dominant soil types in the watershed namely chromic luvisols, eutric vertisols, haplic luvisols, and humic nitisols (Fig. 2b). A DEM data of 30-m resolution was used for watershed discretization and stream network creation. The DEM data were obtained from the ASTER GLOBAL archive at the USGS website (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/).

Hydrometeorological data

Daily climatic data were required by the model to simulate different biophysical processes in the hydrological model. The required daily climate data include rainfall, maximum temperature (T-max), minimum temperature (T-min), relative humidity (RH), wind speed, and sunshine hours, which were collected from the Ethiopian National Meteorological Services Agency (ENMSA) for Bahir Dar, Adet, Merawi and Meshenti meteorological stations (Fig. 1). The climate data were available for the period 1991–2012. The Bahir Dar and Adet stations all the observed climate variables were available while the Merawi station observed only rainfall and maximum/minimum temperature. The Meshenti station observed only rainfall data. Since the data for the Bahir Dar station have a better quality for most of the climatic variables, the missing records for all of the stations were completed using a weather generator based on Bahir Dar station. Although sunshine hours data were available, the hydrological model used in this study required solar radiation data to estimate evapotranspiration and other processes. Therefore, solar radiation (Rs) was calculated based on the sunshine hours using the Angstrom algorithm (Allen et al. 1998).

The study used observed streamflow data to calibrate and validate the SWAT model. The observed streamflow data were collected from the hydrology department of the Ethiopian Ministry of Water, Irrigation, and Energy (MWIE) and Abay (Blue Nile) Basin Authority.

The future climate of the study area was predicted using outputs from the Global Climate Models (GCMs). GCMs have been considered as credible tools to simulate the response of the global climate system to the increasing greenhouse gas concentrations (IPCC-TGCIA 1999). However, climate change projections involve uncertainties due to various assumptions in GCM conceptualizations, and scenario developments (IPCC 2014). Due to such uncertainties, multiple GCM outputs and scenarios are often used to get plausible estimates of the future climate (Christensen et al. 2007). This study, therefore, used climate data from the Hadley Center Coupled Model version 3 (HadCM3) and the Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis second-generation Earth System Model (CanESM2) GCMs to estimate the future climate change of the Andasa watershed. Moreover, the study used two scenarios each from the two models. The scenarios from the HaDCM3 were A2 and B2, and Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) 4.5 and 8.5 for the CanESM2 model. These scenarios represent the average (B2 and RCP 4.5) and extreme condition scenarios (A2 and RCP 8.5) were selected to reasonably capture the impact of climate change on the hydrology of the watershed (Table 2). The GCM climate outputs data were obtained from the Canadian climate data and scenario website (http://climate-scenarios.canada.ca/?page=main).

Modelling approach

Prediction of climate change

The coarser scale GCM outputs were downscaled into finer scale climate predictions using a tool called Statistical Downscaling Model (SDSM version 4.2). SDSM uses long-term historical climate data to establish relationships between predictands and predictors (Wilby and Dawson 2007). The SDSM served as a vital tool for low cost, and rapid assessments of localized climate change studies (Wilby and Dawson 2007).

The GCMs data were calibrated and validated using observed rainfall, T-max, and T-min of the Bahir Dar station due to its long-term historical and better quality data. The HadCM3 and CanESM2 were calibrated and validated for the period of 1961–2000, and 1961–2005, respectively, using data from the National Center for Environmental Prediction (NCEP). Since the evaluation of the climate data (i.e., rainfall, T-max, and T-min) at Bahir Dar station showed a high correlation with the rest of the stations (r > 0.9), the downscaled future climate change variables at the Bahir Dar station were introduced to other stations.

Downscaling of rainfall is generally challenging because of the complex ocean and atmospheric circulation parameters (predictors) and local rainfall (predictand) (Table 3) (Pour et al. 2014; Forland et al. 2011; Sachindra et al. 2014). Due to the difficulty of replicating the GCM outputs to the observed rainfall, it is generally recommended to mimic the long-term averages of the GCM variables to that of the observed (McMahon 2015).

In the SDSM methodology, predictors were selected when they showed a significant relationship with the predictand variables (i.e., rainfall, T-max, and T-min). The relationship was considered significant when partial r-value was ≥ ± 0.5 and P value ≤ 0.05 (Wilby and Dawson 2007). The strength of the relationship was further checked using scatterplot to assess if the significance is affected by outliers. As is presented in Table 4, strong agreements were observed between the selected predictor and predictand variables in all of the scenarios.

Changes in the projected climate were estimated in reference to a baseline period of 1993–2012 (Vbase). The three studied periods span for 30 years based on the recommendation of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO 2017) representing the periods 2013–2039 (the 2020s), 2040–2069 (2050s), and 2070–2099 (2080s).

Percent changes and differences (Δ) between projected climate and baseline climate were calculated for rainfall and temperature using the following equations:

where ΔP and ΔT refer to the percent change in mean monthly rainfall and difference in mean monthly temperature, respectively. V2020s, V2050s and V2080s represent the mean of all average mean monthly rainfall and temperature ensembles, and VbaseP and VbaseT refer the mean monthly rainfall and mean monthly average temperature for the baseline period, respectively (Wilby and Dawson 2007).

Hydrological modeling

SWAT is a river basin (watershed) scale model that allows studying durable impacts and the best modeling tool to account for heterogeneous soils, land use, and management practice (Winchell et al. 2013). In addition, it showed better performance for agriculture-dominating watersheds (Golmohammadi et al. 2014). To capture the spatial variability, SWAT divides into small spatial disaggregates called Hydrological Response Unit (HRU) (Arnold et al. 2012). It is also successful in the simulation of management practices and climate scenarios (Bonuma et al. 2015). Furthermore, reports indicated that it is frequently applied in the Nile basin including its sub-basins and show good performances (Awulachew et al. 2008; van Griensven et al. 2012).

The SWAT hydrological model was setup to study the impact of climate change on the hydrology of Andasa watershed. The model was simulated for the period 1991–2012 in which the first 2 years of simulations were used for the model warm-up to initialize different watershed processes. The model was calibrated and validated using observed streamflow for the period 1993–2006, and 2007–2012, respectively.

The SWAT model sensitive parameters were identified and calibrated using a Sequential Uncertainty Fitting version 2 algorithm (SUFI-2) in SWAT-Calibration and Uncertainty Program (SWAT-CUP). The higher absolute value of t-stat with smaller p value (x ≤ 0.05) is considered as sensitive parameters (Abbaspour 2015). The robustness of the model calibration and uncertainty was evaluated using P-factor, R-factor, and different statistical goodness-of-fit evaluation indices such as Nash–Sutcliff efficiently (Nash and Sutcliffe 1970) and Percent Bias (PBIAS). P-factor estimates the percentage of the observed data bracketed within the 95 Percent Prediction Uncertainty (95PPU) while the R-factor estimates the distance between the upper and lower 95PPU (Abbaspour et al. 2004).

Estimating climate change impact

Once the SWAT model was calibrated and validated based on observed streamflow data, it was used for the climate change impact analysis. The impact of climate change on the hydrology of the watershed was studied by introducing the percent change in mean monthly rainfall and difference in mean monthly temperature (Δ°C) into the calibrated and validated SWAT model for three future periods(the 2020s, 2050s, and 2080s). Figure 3 presents the methodological framework including model input, data processing, calibration and validation, and climate change impact analysis.

Results and discussion

Climate change in the Andasa watershed

Rainfall may show a reduction in all the scenarios of the two GCMs with a consistent agreement for the coming century (Fig. 4). The majority of the climate change scenarios simulated a decrease in mean monthly rainfall for all months of three periods of the 2020s, 2050s, and 2080s; however, there was no agreement on the magnitude of changes predicted by the GCM scenarios (Fig. 5). The decrease in mean monthly rainfall ranges between 9.2% and 97.1% in which the highest decrease was predicted by the CanESM2 model in the RCP 8.5 scenario in the middle of the century (in the 2050s). During the 2030s, an increase in mean monthly rainfall was observed in the months of March and October for the RCP 8.5, and in the month of April for the RCP 4.5. In the 2050s, all GCM scenarios showed an increase in rainfall in the months of March and April, except the HadCM3 A2 scenario which showed a decrease in rainfall in April. Compared to the other periods an increase in rainfall was observed in the 2080s in which at least one of the GCM scenarios showed an increase in mean monthly rainfall during the period of November to May (Fig. 5). On the other hand, the reduction of mean annual rainfall ranges from 22.5% in the 2080s to 46.1% in the 2020s. The emission scenarios (A2 and B2) projected the highest decrease in mean annual rainfall than the concentration scenarios (RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5) in the three future periods (the 2020s, 2050s, and 2080s) (Fig. 5).

Since there are limited studies in the Andasa watershed, it was difficult to compare the results to previous studies. However, there are several climate change studies in the Upper Blue Nile basin where the Andasa watershed is located, which provides some insight into how climate change may unfold in the Andasa watershed. On the other hand, climate change studies in the Upper Blue Nile basin showed differing results in terms of the future rainfall. This is because predicting rainfall is a difficult task since it is influenced by complex atmospheric processes (Conway and Schipper 2011; Taye et al. 2011). To combat such uncertainties, Setegn et al. (2011) used a multimodel to hydroclimatic change study in the Lake Tana subbasin of the Upper Blue Nile basin and reported similar findings as this study that the future rainfall may generally decrease in the Lake Tana basin. On the other hand, Aich et al. (2014) projected an increasing trend of monthly rainfall in the Upper Blue Nile basin. However, there are studies that observed increasing and decreasing impact over different time periods in the future. For example, Beyene et al. (2009), estimating multimodel averages of 11 GCMs, reported that rainfall may increase early in the twenty-first century and a decrease at the end of the century. Some studies applied multimodel climate change studies and provided mixed findings in terms of rainfall projection. For example, Elshamy et al. (2009) studied the impact of climate change in the Upper Blue Nile basin using 17 GCMs from the IPCC 4th Assessment Report (AR4), and reported that 10 of the GCMs showed decreasing annual rainfall and the rest showed an increasing annual rainfall. Conversely, some studies (e.g., Taye et al. 2011; Enyew et al. 2014) reported that there is no clear trend of rainfall change due to climate change in the Upper Blue Nile basin. Taye et al. (2015) reviewed climate change and variability in the Upper Blue Nile basin. They reported that the reasons for differing results related to climate change are related to the inconsistent use of both climate and hydrologic models, emission scenarios, and GCM output downscaling techniques. Akhter et al. (2018) also reported that differences in rainfall projections may occur due to the variations of atmospheric domain sizes which determine the hydro-climatology of a watershed by affecting the selection and number of sensible predictors.

As discussed in the Taye et al. (2015), there is no consensus in rainfall projection in the Upper Blue Nile basin (e.g., Conway and Schipper 2011; Elshamy et al. 2009; Gebre and Ludwig 2015). Although this study used different GCM scenarios based on the 4th and 5th IPCC Assessment Report (AR), the finding from this study is a bit different from the other studies. For example, Gebre and Ludwig (2015) used 5 RCP-based GCMs to study climate change impact in the Tana subbasin, and their result showed that 4 of the GCMs (MPI-esm, IPSL-CM5, Ec-Earth, CNRM-cm5) showed an increasing mean annual rainfall while 1 GCM (Hadgem2-es) projected relatively a decreasing trend for the 2030s and 2070s except for RCP 8.5.

Dile et al. (2013) also predicted a decrease in mean annual rainfall at Gilgel Abay River in the Upper Blue Nile basin in the initial 2020s and an increase in the 2050s and 2080s. According to their findings, the mean annual rainfall may decrease by − 10% and − 13% in the 2020s, and increase by 3.8% and 2.2% in 2050s, and 19.3% and 12% in the 2080s in the A2a and B2a scenarios, respectively. Although there will be a difference in magnitude, the prediction by Dile et al. (2013) is in line with this study for the 2020s period. This study predicted a decrease in mean annual rainfall by − 46.1% and − 46% for A2a and B2a scenarios for the 2020s (Fig. 5; Table 5).

The projected temperature (T-max and T-min) showed increasing trends in the HaDCM3 and CanESM2 scenarios for the coming century (Fig. 6). Figure 6 apparently shows the increasing trend of temperature throughout the future periods.

The climate change analysis from the two GCMs showed that there may be an increase in mean monthly for the 2020s, 2050s, and 2080s periods (Fig. 7). The change in mean monthly temperature for the coming century may range between 0.4 °C and 8.5 °C (Fig. 7). The increasing pattern of mean monthly temperature change was consistent among the model scenarios and three future periods where the highest mean monthly temperature increase was observed in the HadCM3 A2 scenario. Change in mean annual temperature on the other hand increased between 1.5 °C by RCP 4.5 in the 2020s and 5.7 °C by A2 scenario in the 2080s (Fig. 7).

However, the projected change in temperature in this study was a little more than estimates for the global average temperature. (Figure 7) The lower end change in mean annual temperature projection using the RCP 4.5 scenario in this study was 1.5 °C–2.9 °C for the coming century while the IPCC (2014) reported a global mean surface temperature change of 1.4 °C (2046–2065) to 1.8 °C (2081–2100). In fact, the global mean temperature projection was made using averages of multiple GCM simulations, which may provide a lower estimate. On the other hand, the finding in this study was consistent with some regional studies in Ethiopia and East Africa. For example, Abdo et al. (2009) reported that the average temperature of Gilgel Abay catchment by the end of the century maybe 3.1 °C and 2.25 °C for HadCM3 A2 and B2 scenarios, respectively. Collins et al. (2013), based on ensemble mean of multiple GCMs, found that the future increase in temperature in the tropics including East Africa may range between 0.9 °C and 4.4 °C for both RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 by the end of the century.

Similar results were reported by other studies in the Upper Blue Nile basin. The highest increase of mean monthly temperature by the end of the century (~ 8.9 °C) was reported by Enyew et al. (2014) and the minimum increase by the early twenty-first century (0.8 °C) was predicted by Setegn et al. (2011). Unlike the rainfall projection, the future temperature projection by several studies (e.g., Aich et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2008; Elshamy et al. 2009; Beyene et al. 2009) was consistent and bracketed within the ranges reported by Enyew et al. (2014) and Setegn et al. (2011).

Findings of this study suggested a general decrease in mean annual rainfall and an increase in mean annual temperature (Table 5). The maximum changes are projected with a decrease in rainfall by 46.1% in the 2020s in the A2 scenario and an increase in temperature by 5.7 °C in the 2080s in the A2 scenario. This is consistent with the emission scenarios assumption that the RCP 8.5 and A2 scenarios represent extreme conditions whereas the RCP 4.5 and B2 represent average conditions. Other literature in the Upper Blue Nile and in East Africa (e.g., Beyene et al. 2009; Abdo et al. 2009; Gebre and Ludwig 2015) reported similar findings of warmer temperature in the RCP 8.5 and A2 scenarios compared to the RCP 4.5 and B2 (Table 5).

Sensitivity analysis, calibration, and validation of the SWAT model

Based on the results of sensitivity analysis conducted via SWAT-CUP by SUFI-2 project, soil hydraulic conductivity (Sol_K), curve number (CN2), deep aquifer percolation fraction (Recharge_DP), manning roughness coefficient for main channel (CH_N2) and soil evaporation compensation factor (ESCO) were identified as the top five sensitive parameters.

The model simulation performance was very good with NSE of 0.84 and PBIAS of − 10.2 for the calibration period. Moriasi et al. (2007) suggested that models that provide NSE between 0.75 and 1.00, and PBIAS < ± 10% are very good. However, the PBIAS value for the validation period was within the range of a good model. The p-factor for the calibration and validation period was, 98% and 76%, respectively. While the r-factor for calibration and validation period was 0.94 and 0.79, respectively. Abbaspour (2015) recommended that for streamflow calibration the r-factor and p-factor values should be > 70% and close to 1, respectively. Therefore, the estimates for the p-factor and r-factor indicated a satisfactory model performance both for the calibration and validation periods (Fig. 8).

Impact of climate change on the hydrology

The results showed that climate change may significantly affect the hydrology of Andasa watershed. It may increase the potential evapotranspiration (PET), and decrease water yield and soil moisture. The increase in PET may reach up to 17.3% (HadCM3 A2 scenario), and the decrease in water yield and soil moisture may reach to − 90% (HadCM3 A2 scenario) and − 50% (HadCM3 B2 scenario), respectively. The impact was comparable to the results reported in similar studies conducted in the Upper Blue Nile Basin. For example, Cherie et al. (2013) showed a decrease in streamflow in the range of − 10% to − 61% in the Upper Blue Nile Basin, which is close to the results presented in this study (Table 5).

The increase in PET and decrease in water yield are related to an increase in temperature and a decrease in rainfall (Table 5). Cherie et al. (2013) reported an increase in PET and a decrease in actual evapotranspiration (AET) due to an increase in temperature and limited soil water availability. PET is evaporative demand and it can increase as the temperature increases whereas AET may decrease since it depends on other factors such as rainfall, soil moisture, canopy interception, and plant transpiration (cf. Neitsch et al. 2011). Besides, Neitsch et al. (2011) stated that when one layer unable to meet the evaporative demand, SWAT does not allow compensating from a different layer. Thus, it results in a reduction in actual evaporation for the HRU (Table 5).

The streamflow simulations from the HadCM3 and CanESM2 scenarios showed a reduction in streamflow in the Andasa watershed compared to the baseline period (Figs. 9, 10). This may be due to a general decrease in rainfall and an increase in temperature in the future periods. The highest decrease in monthly streamflow was simulated up to 100%. All the scenarios except 4.5, simulated the maximum change in streamflow at least once in the three periods. On the other hand, an increase in monthly streamflow was simulated by 44.2% and 89.8% on April 2050s and 2080s by the RCP 4.5 scenario, respectively. This is mainly because the exceptional increase in mean monthly rainfall of up to 5.3% and 108.9% was projected in the 2050s and 2080s with the RCP 4.5 scenario, respectively.

Unlike the mean monthly rainfall, all the scenarios consistently projected a change in mean annual rainfall in the range of − 22.5% to − 46.1%. Hence, it leads to a change in mean annual streamflow in a range of − 48.8% to − 95.6% (Table 5). This shows that the direction of changes in streamflow follows the direction of changes in rainfall.

Since the streamflow is highly influenced by rainfall, a decreasing trend of rainfall caused a corresponding decrease in streamflow for the future period. A similar finding was reported by Setegn et al. (2011) and partly by Dile et al. (2013). Conversely, Aich et al. (2014) projected an increasing trend of streamflow in the Blue Nile basin. However, climate change impact study in the Upper Blue Nile by Taye et al. (2011) found a mixed trend of streamflow prediction in the 2050s.

As indicated in Fig. 10, the watershed may experience less flow condition in the coming periods compared to the baseline period. All the scenarios agreed that there may be a mean annual decrease in streamflow due to climate change. The most pronounced reductions in streamflow were simulated by the HadCM3 Scenarios (A2 and B2) than the CanESM2 scenarios (RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5) in the future periods. These are due to the highest decrease in both mean monthly and mean annual rainfall was projected by A2 and B2 scenarios. It results in a reduction of streamflow by the scenarios that were simulated compared to the baseline period (Fig. 10). Overall, these affirm that climate change would have a profound effect on the hydrology of Andasa watershed.

Furthermore, the simulated streamflow with all the scenarios showed a consistent pattern with the baseline period (Fig. 10), which suggested that climate change may not significantly affect the seasonal variability of the streamflow in the Andasa watershed.

Conclusion

The future climate of the Andasa watershed was studied by downscaling GCM outputs using the Statistical Downscaling Model (SDSM version 4.2). The maximum/minimum temperature and rainfall data were obtained from HadCM3 and CanESM2 GCM from 1961 to 2099. Two scenarios from each model were selected to represent a range of greenhouse gas emissions/concentrations. The scenarios were A2 and B2 from HadCM3, and RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 from Can ESM2 models. Generally, there may be a decrease in mean monthly rainfall in the majority of the scenarios and an increase in mean monthly temperature for the coming century. While all the scenarios provided an increasing mean monthly temperature as well as mean annual temperature for the study periods, there was no consistency among the scenarios in projecting the mean monthly rainfall. However, all scenarios uniformly projected a decrease in mean annual rainfall for the three future periods.

SWAT model simulated results revealed that the hydrological components of the watershed may be negatively impacted by climate change. The potential evapotranspiration (PET) may increase and other hydrological components such as actual evaporation (AET), streamflow, water yield, and soil moisture may decrease compared to the baseline period (1993–2012). The increasing trend in PET was related to the increase in temperature, whereas the decrease in other hydrological components was due to the decrease in rainfall and increase in temperature. This suggests that for the coming century, the Andasa watershed may have a constrained soil moisture regime. Therefore, appropriate climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies should be implemented in the Andasa watershed to reduce the negative externalities on soil moisture and streamflow, which are the lifeline for smallholder farmers in the watershed.

References

Abbaspour KC, Johnson CA, van Genuchten MT (2004) Estimating uncertain flow and transport parameters using a sequential uncertainty fitting procedure. Vadose Zone J 3:1340–1352

Abbaspour KC (2015) SWAT-CUP: SWAT calibration and uncertainty programs—a user manual. Eawag: Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, 100

Abdo KS, Fiseha BM, Rientjes THM, Gieske ASM, Haile AT (2009) Assessment of climate change impacts on the hydrology of GilgelAbay catchment in Lake Tana basin, Ethiopia. Hy Process 23:3661–3669. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp

Aich V, Liersch S, Vetter T, Huang S, Tecklenburg J, Hoffmann P, Koch H, Fournet S, Krysanova V, Müller EN, Hattermann FF (2014) Comparing impacts of climate change on streamflow in four large African river basins. Hy Earth SystSci 18(4):1305–1321. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-18-1305-2014

Akhter J, Das L, Meher JK, Deb A (2018) Evaluation of different large-scale predictor-based statistical downscaling models in simulating zone-wise monsoon precipitation over India. Int J Climatol 2018:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5822

Allen RG, Pereira LS, Raes D, Smith M (1998) FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56 Crop Evapotranspiration (guidelines for computing crop water requirements ), 56, p. 300

Arnold JG, Kiniry JR, Srinivasan R, Williams JR, Haney EB, Neitsch SL (2012) Soil & water assessment tool input/output documentation version 2012. Texas water resources institute TR-439

Awulachew SB, Mccartney M, Steenhuis TS, Ahmed AA (2008) A review of hydrology, sediment and water resource use in the Blue Nile Basin. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute. (IWMI Working Paper 131)

Bates BC, Kundzewicz ZW, Wu S, Palutikof JP (eds) (2008) Climate change and water. Technical Paper of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC Secretariat, Geneva. pp. 210

Beyene T, Lattenmaier DP, Kabat P (2009) Hydrologic impacts of climate change on the Nile river basin: implications of the 2007 IPCC Scenarios. Clim Change 100:433–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-009-9693-0

Bonuma NB, Reichert JM, Rodrigues MF, Monteiro JAF, Arnold JG, Srinivasan R (2015) Modeling surface hydrology, soil erosion, nutrient transport, and future scenarios with the ecohydrological swat model in modeling surface hydrology, soil erosion, nutrient transport, and future scenarios with the ecohydrological swat model in. Tópicos Ci Solo 9:241–290

Christensen JH, Hewitson B, Busuioc A, Chen A, Gao X, Held I, Jones R, Kolli RK, Kwon W-T, Laprise R, Magaña Rueda V, Mearns L, Menéndez CG, Räisänen J, Rinke A, Sarr A, Whetton P (2007) : Regional Climate Projections. In: Climate Change (2007) The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In: Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Chen Z, Marquis M, Averyt KB, Tignor M, Miller HL (eds) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, USA

Collins M, Knutti R, Arblaster J, Dufresne J-L, Fichefet T, Friedlingstein P, Wehner M (2013) Long-term climate change: projections, commitments and irreversibility. In S. T. (UK) Sylvie Joussaume (France), Abdalah Mokssit (Morocco), Karl Taylor (USA) (eds), Long-term climate change: projections, commitments and irreversibility. p. 108

Conway D, Schipper ELF (2011) Adaptation to climate change in Africa: challenges and opportunities identified from Ethiopia. Global Environ Change 21(1):227–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.013

Diao X, Fekadu B, Haggblade S, Taffesse AS, Wamisho K, Yu B (2007) Agricultural growth linkages in Ethiopia: estimates using fixed and flexible price models. IFPRI Discussion Paper No. 00695

Dile YT, Berndtsson R, Setegn SG (2013) Hydrological response to climate change for GilgelAbay River, in the Lake Tana Basin—Upper Blue Nile Basin of Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 8(10):12–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079296

Elshamy E, Seierstad A, Sorteberg A (2009) Impacts of climate change on Blue Nile Flows Using Bias—corrected GCM scenarios. Hydrol Earth SystSci 13:551–565

Enyew BD, Van Lanen HAJ, Van Loon AF (2014) Assessment of the impact of climate change on hydrological drought in Lake Tana Catchment, Blue Nile Basin. Ethiopia J GeolGeosci 3:174. https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-6755.1000174

FAO (1997) The digital soil and terrain database of East Africa (Sea): Notes on the arc/ INFO files at 1:1 000 000 scale. Rome

Forland EJ, Benestad R, Hanssen-Bauer I, Haugen JE, Skaugen TE (2011) Temperature and precipitation development at Svalbard 1900–2100. AdvMeteorol 2011:14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/893790

Gebre SL, Ludwig F (2015) Hydrological response to climate change of the Upper Nile River Basin: based on IPCC fifth assessment report (AR5). J Climatol Weather Forecast 3:121. https://doi.org/10.4172/2332-2594.1000121

Golmohammadi G, Prasher S, Madani A, Rudra R (2014) Evaluating three hydrological distributed watershed models: MIKE-SHE, APEX, SWAT. Hydrology 1:20–39. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrology1010020

van Griensven A, Brussel VU, Yalew SG, Kilonzo F (2012) Critical review of SWAT applications in the upper Nile basin countries. Hyd Earth SystSci 16:3371–3381. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-16-3371-2012

IPCC-TGCIA (1999) Guidelines on the use of scenario data for climate impact and adaptation assessment. Version 1. Prepared by Carter TR, Hulme M, Lal M (eds) Intergovernmental panel on climate change, task group on scenarios for climate impact assessment. pp. 69

IPCC (2007) Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In: Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, van der Linden PJ, Hanson CE (eds) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 976

IPCC (2013) Annex III: glossary. In: Planton S (ed) Climate Change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In: Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner G-K, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley PM (eds). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, USA

IPCC (2014) Climate change 2014: synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In: Core Writing Team, Pachauri RK, Meyer LA (eds). IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 151

Kim U, Kaluarachchi JJ, Smakhtin VU (2008) Climate change impacts on hydrology and water resources of the Upper Blue Nile River Basin, Ethiopia. International Water Management Institute, Colombo, Sri Lanka, p. 27

Loucks DP, Van Beek E, Stedinger JR, Dijkman JP, Villars MT (2005) Water resources system planning and management. An introduction to methods, models and applications. UNSCO Publishing, The Netherlands, pp 59–77; pp, 328–329

Marvel K, Bonfil C (2013) Identifying external in fluences on global precipitation. ProcNatlAcadSci. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1314382110

McMahon TA, Peel MC, Karoly DJ (2015) Assessment of rain fall and temperature data from CMPI3 global climate models for hydrologic simulations. Hydrol Earth SystSci 19:361

Melese SM (2016) Effect of climate change on water resources. J Water Resour Ocean Sci 5(1):14–21. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.wros.20160501.12

MoWR and GW-MATE (2011) Ethiopia: strategic framework for managed groundwater development. Addis Ababa

Moriasi DN, Arnold JG, Van Liew MW, Bingner RL, Harmel RD, Veith TL (2007) Model evaluation guidelines for systematic quantification of accuracy in watershed simulations. Am SocAgricBiologEng 50(3):885–900

Nash J, Sutcliffe J (1970) River flow forecasting through conceptual models: part I—a discussion of principles. J Hydrol 10:282–290

Neitsch S, Arnold J, Williams J, Kiniry J, King, K (2011) Soil & Water Assessment Tool Theoretical Documentation Version 2009. Technical Report No. 406. Texas water resources institute

Nyong A (2005) Impacts of climate change in the tropics : the African Experience. p. 24

Pour SH, Harun SB, Shahid S (2014) Genetic programming for the downscaling of extreme rainfall events on the East Coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Atmosphere 5:914–936. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos5040914

Praskievicz S, Chang H (2009) A review of hydrological modeling of basin scale climate change and urban development impact. ProgPhysGeogr 33(5):650–671

Sachindra DA, Huang F, Barton A, Perera BJC (2014) Statistical downscaling of general circulation model outputs to precipitation—part 1:calibration and validation. Int J Climatol 34(11):3264–3281. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.3914

Setegn SG, Rayne D, Melesse AM, Dargahi B (2011) Impact of climate change on the hydroclimatology of Lake Tana Basin, Ethiopia. Water Resour Res 47:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010WR009248

Taye MT, Ntegeka V, Ogiramoi NP, Willems P (2011) Assessment of climate change impact on hydrological extremes in two source regions of the Nile River Basin. Hy Earth SystSci 15:209–222. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-15-209-2011

Taye MT, Willems P, Block P (2015) Implications of climate change on hydrological extremes in the Blue Nile basin: a review. J HydrolReg Stud 4:280–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2015.07.001

Texas A& M University (2016) SWAT|soil & water assessment tool. ARCSWAT|soil and water assessment tool. https://swat.tamu.edu/. Accessed 2 Dec 2016

Trenberth KE, Miller K, Mearns L, Rhodes S (2000) Effects of changing climate on weather and human activities. University Corporation for atmospheric research

WMO (2017) WMO guidelines on the calculation of climate normals. WMO-No. 1203

Wilby RL, Dawson CW (2007) Statistical downscaling modeling (SDSM 4.2) user manual. p. 94

Winchell M, Srinivasan R, DI Luzio M, Arnold J (2013) Arc swat interface for swat 2012 user’s guide

World Bank (2006) Ethiopia: managing water resources to maximize sustainable growth. A World Bank Water Resources Assistance Strategy for Ethiopia. World Bank, Washington, DC

Xu CY (1999) From GCM to river flow: a review of downscaling methods and hydrological modeling approaches. ProgPhysGeogr 23(2):229–249

Yiqiang G, Yanbin W, Zhengshan J, Jun W, Luyan Z (2010) Remote sensing image classification by the Chaos genetic algorithm in monitoring land use changes. Math Comput Model 51:1408–1416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcm.2009.10.023

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the Ethiopian Ministry of Water, Irrigation, and Energy (MWIE), Abay Basin Authority, and Ethiopian National Meteorological Services Agency (ENMSA) for the provision of the relevant data. We are also grateful for Hawassa University, Institute of Technology for the financial support of the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tarekegn, N., Abate, B., Muluneh, A. et al. Modeling the impact of climate change on the hydrology of Andasa watershed. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 8, 103–119 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-020-01063-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-020-01063-7