Abstract

This paper presents a critical examination of recent Polish takeover regulation from a perspective of evolution of capital market law in Poland. The study is based on both legal analysis and an empirical and statistical approach. Firstly, as a starting point, it briefly describes the mandatory bid rule and Takeover Bids Directive as well as the development of early Polish provisions. Secondly, the paper elaborates on the normative model of takeovers, which was in force until 2022. Using a case study and a comprehensive statistical examination of all mandatory bids carried out between 2008 and 2017, it shows how the unusual and incorrect legislative structure of two thresholds of control (33% and 66% of votes) allowed the actual circumvention of mandatory bids, to the detriment of minority shareholders. The paper also describes political considerations and political influences on the legislative process, which led to the failure of the 2014–2015 takeover law proposal. The core of the paper is devoted to the current takeover rules. Statistical research of ownership structures in Poland shows that the threshold of control set at 50% of votes is undoubtedly too high, which entails risks to investor protection that may arise from the adopted model. Based on research on significant holdings in Polish listed companies, the paper further elaborates on the notion of control over a public company and proposes a regulatory utility function to determine the desired threshold of control. This leads to the conclusion that the optimal regulatory threshold of control, given the characteristics of the Polish capital market, is 30% of votes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction: The Polish Capital Market and Takeover Regulation in Perspective

The Polish capital market was reactivated in 1991, as part of a wave of free market reforms and socio-economic transformation in Poland. Three decades later, it is considered a major player in the Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) region, with the number of listed companies reaching 417 on the Warsaw Stock Exchange main market (regulated market), an additional 379 companies on NewConnect (a Polish multilateral trading facility (MTF) operating outside of regulated market, established in 2007), close to 50 foreign listings and a variety of other financial instruments.Footnote 1 In stark contrast to the first April 1991 session with 112 buy and sell orders in total,Footnote 2 in 2007 alone the Warsaw Stock Exchange had 81 IPOs, placing it second in Europe, only behind the London Stock Exchange.Footnote 3

However, the success of the Warsaw Stock Exchange did not go hand in hand with the quality of the Polish takeover regime, especially with well-designed provisions on mandatory bids. Since 1991, the takeover regulation has been changed quite a few times—four major revisions and at least twenty smaller amendments—with the provisions being subject to fierce critique. In February 2022, the Polish legislator announced yet another proposal for the new fundamental change to takeover law, which was adopted by Parliament in the blink of an eye (at least relative to the usual legislative timelines), as the act was passed in April and subsequently entered into force at the end of May 2022.

This paper scrutinizes the current takeover regime in the broad context of the Takeover Bids Directive, the historical evolution of the Polish capital market law and the economic characteristics of this segment of the Polish economy. It features both a legal study of the changing regulations as well as detailed empirical research regarding all takeover bids carried out on the Warsaw Stock Exchange in a period of ten years (2008–2017) and an economic analysis of ownership structures of Polish listed companies. This wide context explains how takeovers in Poland were influenced by flawed legislation, which for years failed to fulfil its function and its goals, and why the current provisions are to a large extent still deficient.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 briefly describes the Takeover Bids Directive, its origins and economic function, together with a comparative view of the mandatory bid rule. The third section examines the evolution of Polish takeover law in the years 1991-2005 and shows the different approaches taken by the legislator during the early phase of the newly reactivated Warsaw Stock Exchange. Section 4 elaborates on the legislative solutions adopted in the period 2005–2022—it shows how the eccentric model of takeover regulation allowed for the mandatory bid requirement to be de facto circumvented in a significant number of takeover transactions during that period. It further provides a statistical analysis of all transactions carried out between 2008 and 2017, which serves as a foundation for a critical examination of the provisions in question. The fifth section describes the politically motivated dispute between Polish ministries, which, in 2015, led to the failure of a reasonable legislative proposal to change the takeover regulation. Section 6 analyzes the recently introduced takeover regime: in the context of a statistical analysis of ownership structures in Poland, it shows that the current provisions, enacted in 2022, are still flawed, as the threshold of control set at 50% of total votes is far too high. Subsequently, Sect. 6 also discusses certain other problematic features of the adopted model (namely lack of a voluntary bids framework and the unreasonable extension of takeover bid obligations to shareholders controlling between 50 and 66% of votes), and possible adverse consequences for the market and provides de lege ferenda remarks on a desired legislative approach. Section 7 concludes.

2 The Takeover Bids Directive and Mandatory Bid Rule—an Overview

The Takeover Bids DirectiveFootnote 4 is one of the European legislative acts with the longest and most turbulent history among the whole acquis communautaire. Early discussions about the European regulations on takeovers of public companies date back to the seventies, when the Pennington ReportFootnote 5 was issued. Inspired by the then-recent British approach,Footnote 6 reflected in the City Code on Takeovers and Mergers of 1968, it proposed a wide regulation covering a variety of aspects related to takeovers of listed companies, most importantly equal treatment of shareholders, mandatory bids and rules of conduct of the bidder, as well as defensive measures available to the target company.Footnote 7

The record of numerous drafts starting in the late eighties, heavy discussions throughout the nineties and the spectacular rejection of the proposal by a razor-thin margin (with just one single missing vote standing in the way of the draft becoming law in 2001)Footnote 8 serve as further examples, in addition to, e.g., the draft Fifth Company Law DirectiveFootnote 9 (which was withdrawn after 30 years)Footnote 10 or the initiative on the European Private CompanyFootnote 11 (withdrawn after 6 years),Footnote 12 of how difficult it is to harmonize company law matters in many countries with different corporate governance systems, path dependencies and political considerations.Footnote 13 What started as a complex draft to establish broad rules on takeovers,Footnote 14 covering not only mandatory bids and proper procedure in cases of takeovers of listed companies, but also and especially provisions on defensive measures and competences of the board under the circumstances of a takeover attempt,Footnote 15 ended up as a set of relatively narrow instruments.

Consequently, the core of the European takeover regime is the mandatory bid rule, laid down in Article 5 of the Takeover Bids Directive.Footnote 16 It provides that in case of the transfer of control over a listed company, the acquirer must carry out a mandatory bid, i.e., make an offer addressed to all remaining shareholders to purchase all of their shares. The purpose of this provision is the protection of minority shareholders, as it gives them the opportunity to exit the company by selling shares at an equitable price (no less than the acquirer paid for the controlling stake) and thus to participate in the control premium paid by the bidder.Footnote 17 It also ensures equal treatment of shareholders and eliminates any form of two-tier discriminatory bids.Footnote 18 It should be noted that not only in EU, but throughout the world, the mandatory bid rule has become a permanent feature of the vast majority of contemporary capital markets, with the U.S. being a rare exception.Footnote 19

Despite the commonness of mandatory bid rules in different countries, the provisions are not harmonized, as there is a wide range of legislative approaches, both throughout the world and even in the EU itself.Footnote 20 By far the most common model (also the default model in the EU—Article 5(3) of the Takeover Bids Directive) relies on setting a single quantitative threshold of control, most commonly around 30% of votes or equity;Footnote 21 however, there are different approaches which can be categorized into several groups. Firstly, the notion of control can also be determined, to some extent, on a qualitative basis, usually supplementing the voting rights threshold. In this vein, some lawmakers refer to actual control or controlling influence, which is exercised by the appointment of a majority of company directors or through other operational control, even if the controlling shareholder does not exceed the quantitative threshold.Footnote 22 Secondly, some jurisdictions with a quantitative threshold of control (percentage of votes) provide additional rules which may alter the threshold of control, due either to the structure of shareholding or to the decision of the company itself.Footnote 23 Finally, in some non-EU jurisdictions, the existence of exemptions, discretionary waivers or the possibility to carry out bids limited in scope strongly influences the shape, impact and efficiency of the mandatory bid rule.Footnote 24

What follows is that the design of the takeover regime comes with a set of policy questions and trade-offs. Setting a uniform takeover threshold at a low level may impede the market for corporate control by halting certain transactions, whereas establishing the threshold at a high level (e.g., around 50% of votes) may allow some change-of-control transactions to be conducted without a mandatory bid, potentially harming minority investors. Other trade-offs are related to the complexity of the designed framework—some more elaborate rules, relying on additional (e.g., qualitative) criteria, may remedy the deficiencies arising from a single uniform threshold, at the expense of legal certainty, clarity and uniformity of regulation.

The remainder of this article is devoted to a detailed analysis of the Polish rules, starting in the early nineties, and to the critique of the choices made by the Polish legislator in dealing with the policy questions and trade-offs related to takeover regulation.

3 The Initial Problem: Early Rules on Takeovers on the Polish Capital Market—1991–2005

To fully comprehend the recently introduced takeover regulation, it is worthwhile to go back 30 years to the beginning of the reactivated capital market and briefly analyze the different regulatory approaches and changing rules. Only from this vantage point is the history of Polish capital market law complete. The first session on the reactivated Warsaw Stock Exchange took place on 16 April 1991, with the initial act containing Polish capital market law adopted on 22 March 1991—the Law on Public Trading of Securities and on Mutual Funds of 1991Footnote 25 (hereinafter: Law on Public Trading of 1991).Footnote 26 The Act was subject to numerous amendments, arising from the rapid growth of the market, many new developments in the field, and different policy choices and regulatory approaches.Footnote 27 As a result, after six years there was a need for a subsequent new legal act devoted to the capital market, which was enacted on 21 August 1997 as the Law on Public Trading in Securities of 1997.Footnote 28 It was in force until the next major revision in 2005, which marks the beginning of the next (current) era of Polish financial market regulation.Footnote 29

The rules on takeovers were present in Polish capital market law since the beginning of the reactivated capital market. In general terms, the period of 1991–2005 can best be described as evolution—different regulatory approaches were undertaken with respect to takeover law, with provisions changing at a relatively high pace.Footnote 30 The most important differences between subsequent provisions concerned: (1) the threshold of control for mandatory bids; (2) other types of bids (including bids for non-controlling holdings); and (3) requirements to notify the supervisor as well as the supervisor’s competences.

With respect to mandatory bids for controlling holdings, the Polish legislator adopted a post-acquisition model, i.e., the mandatory bid had to be carried out only after the investor crossed the threshold of control, which was 50% of votes between 1991 and 1993, 33% of votes between 1993 and 1997, and again 50% of votes from 1997 until 2005. Regarding other types of bids, initially (1991–1993) the legislator provided an additional threshold of 33% of votes. This threshold could only be crossed through a mandatory bid, which did not have to cover all remaining shares of the company. Therefore, in the first two years, the Polish legislator also created a pre-acquisition bid, which was limited in scope. This model lasted until the amendment enacted on 29 December 1993,Footnote 31 which set the threshold of control at 33% in case of mandatory post-acquisition bids (covering all shares), thus abolishing the pre-acquisition limited bids and abandoning the two separate thresholds of 33% and 50% of votes. At the same time, in the 1993 amendment the legislator established small bids related to non-controlling holdings—the acquisition of 10% of votes in less than 90 days was required to be conducted only through a small bid. This instrument was kept in the takeover regime of the subsequent Law on Public Trading in Securities of 1997 and, in slightly modified form, from 2005 until it was finally abolished in 2017. The bids framework was supplemented by the rules on making a proper notification to the supervisor, who, most importantly, had the competence to oppose the takeover (until 2005).Footnote 32

In short, in the early period of takeover law in Poland, the following rules related to takeover law were in place: (1) between 1991 and 1993: a mandatory post-acquisition bid for all shares when crossing the 50% threshold, together with a mandatory pre-acquisition limited bid when crossing the 33% threshold and a notification requirement related to crossing the 33% threshold; (2) between 1993 and 1997: a mandatory post-acquisition bid for all shares when crossing the 33% threshold, together with small bids covering the acquisition of 10% of votes in 90 days and a notification requirement related to crossing the 25%, 33% or 50% threshold; (3) between 1997 and 2005: a mandatory post-acquisition bid for all shares when crossing the 50% threshold, together with small bids covering the acquisition of 10% of votes in 90 days and a requirement to obtain prior approval when crossing the 25%, 33% or 50% threshold.

The variety of approaches and frequent changes, resembling a hit-or-miss attitude, are nonetheless to some extent understandable, given the circumstances. Market practices, as well as legal and economic know-how, were still evolving, and fast changes were often necessary to react to hardly foreseeable circumstances, new technologies or global trends. From a substantive perspective, the 50% threshold of control, dominant in that period, appears to be too high, especially given the fact that the ownership structures in Poland were slightly more dispersed in the nineties than they are now.Footnote 33 This initial problem, related to a lack of thorough economic examination of designed provisions, has remained to this day, with takeover regulation getting worse, instead of better, throughout the years.

4 The Subsequent Problem: Takeover Regulation in 2005-2022

4.1 Regulatory Background and Typology of Takeover Bids in the Act on Public Offering

After several approaches to takeover regulation described above, 2005 saw the arrival of a new model. It was enacted as part of a wide regulatory reform of Polish capital market law, which was related to the Polish accession to the European Union back in May 2004 and the implementation of the EU securities and capital market law in force at the time.Footnote 34

As a consequence, the Law on Public Trading of Securities of 1997 was replaced by three legal acts: (1) the Act on Public Offering of 2005,Footnote 35 dealing with the primary market, issuance of securities, provisions applicable to listed companies, and takeover law; (2) the Act on Trading of Securities of 2005,Footnote 36 covering the secondary market; and (3) the Act on Supervision of the Capital Market.Footnote 37 With numerous amendments carried out in the following years, those three legal acts still constitute the core of Polish capital market law.

In the Act on Public Offering, the legislator laid down several different types of takeover bids, i.e.: (1) mandatory bids (Articles 73–74, with respective sub-types); (2) small bids (Article 72, until 2017); (3) delisting bids (Article 91, sec. 6); and (4) cross-border bids (Article 90a, since 2008). On top of that, legal practice and scholarship accepted voluntary bids, i.e., share purchases not based on explicit provisions of capital market law, but constructed on the basis of general rules of Polish civil law.

The first of the listed categories—mandatory bids—constituted the core element of the takeover regime and were designed to implement Article 5 of the Takeover Bids Directive. Interestingly, the Polish legislator created two separate thresholds of control, i.e., 33% of total votes and 66% of votes, and consequently two separate categories of bids (Articles 73 and 74, respectively). The solution providing two separate thresholds of control is not very common; still, it has been adopted in some countries, such as Finland, Norway and Portugal.Footnote 38 However, what made the Polish model peculiar, is that the first threshold of control—33% of total votes—was related to the requirement to carry out a bid which did not have to cover all of the remaining shares, but only a number of shares that might have allowed the bidder to reach the 66% of total votes. Only crossing the second threshold of control—66% of votes—was associated with the requirement to carry out a bid covering all remaining shares.Footnote 39

To make matters more complicated, each of those categories included two sub-types of bids, i.e., pre-acquisition bids, to be carried out before crossing the threshold of 33% or 66% of votes (Articles 73, sec. 1, and 74, sec. 1, respectively) and post-acquisition bids, carried out after crossing one of the said thresholds (Articles 73, sec. 2 , and 74, sec. 2). From a normative perspective, the default rule was the requirement to carry out the bid before crossing the threshold (pre-acquisition), meaning that crossing either 33% or 66% of votes, as a general rule, was only allowed by carrying out a bid. However, the said default rule had several enumerated exceptions, which allowed carrying out the mandatory bid after the threshold was crossed. Those exceptions were all related to events of crossing the threshold of votes without directly purchasing the shares of a target company in the secondary market. Most importantly, this covered the indirect acquisition of a holdingFootnote 40 (acquiring another company, including SPVs, owning shares above 33% of total votes in the target company), changes of the articles of association, and mergers or divisions. In short, the Polish legislator provided four categories of bids, i.e.: (1) pre-acquisition bids for up to 66% of votes; (2) post-acquisition bids for up to 66% of votes; (3) pre-acquisition bids for all remaining shares; and (4) post-acquisition bids for all remaining shares.

Another category of bids that should be highlighted were small bids—acquiring a significant non-majority holding (5% or 10% of votes) in a specified timeframe also required carrying out a bid, similar to the rules in place since 1993. This category was removed in 2017.Footnote 41

4.2 2005 Polish Takeover Law in Practice—Two Thresholds of Control, Limited Takeover Bids and the Detriment to Minority Shareholders

The model of two thresholds of control—33% and 66% of votes—was subject to fierce critique in Polish academia, starting with a legislative proposal in 2005,Footnote 42 throughout the 17 years it was in force.Footnote 43 Firstly, it was pointed out that crossing the first of the two thresholds—33% of votes—did not require carrying out a takeover bid covering all of the remaining shares and, as a consequence, it did not allow all willing shareholders to tender their shares. Secondly, the threshold of 66% of votes, even though related to the requirement to launch a bid covering all of the remaining shares, was far too high, as control over the company is acquired with a much smaller holding. Therefore, neither of the two thresholds of control constituted a proper implementation of the mandatory bid rule established in Article 5 of the Takeover Bids Directive.Footnote 44 Especially the combination of the 33% threshold, lack of a requirement for the bid to cover all of the shares and the possibility of a post-acquisition bid for up to 66% of votes allowed for an odd practice to grow. A prominent example is the widely discussed takeover of Bank BPH S.A. by GE Money Bank in 2008,Footnote 45 which was done by establishing a special purpose company, transferring the stake representing 65.9% of votes to that company and then executing the purchase of that special purpose vehicle. In this way, the mandatory bid covered only 0.1% of votes (in line with the provisions, only for the remaining stake, in order to be able to reach up to 66% of votes in total).Footnote 46

The Bank BPH case was not the only bad apple. Rather, its story is also that of a common approach to takeover bids at the time. For the purpose of this article, all takeover bids carried out on the Warsaw Stock Exchange in the period 2008–2017 were examined. In the decade analyzed, 269 bids were carried out under the provisions of the Act on Public Offering. Out of these, 187 mandatory bids were executed, with the remaining transactions belonging to other categories, namely delisting bids (37), small bids (42) and cross-border transactions (3). Focusing solely on mandatory bids, the descriptive statistic, which includes the number of bids as well as the percentage of votes covered by the bids in each category, is presented in Table 1 above.

A glimpse at the statistics presented above clearly shows the problem with Polish takeover regulation, which persisted for 17 years (2005–2022). The post-acquisition bids for up to 66% of votes turned from a regulatory exception to a firm rule in practice, with their number being significantly higher than that of pre-acquisition bids (56 compared to 33). Looking at the percentage of votes covered by each category of takeover bids, it can be seen that the majority of bids belonging to the category of post-acquisition bids for up to 66% of votes mostly covered a negligible number of shares. The median of 0.1613% informs that in half of all those bids the shares covered represented, literally, a fraction of a percent, with only a quarter of bids (third quartile) covering more than 6% of votes of the target company. Therefore, the standard practice when carrying out takeovers of listed companies was to set up an SPV, transfer a significant holding of shares to that SPV (as close to 66% as possible), purchase the SPV and execute a mandatory bid for a negligible number of shares (the difference between 66% and the shares placed in the SPV).

And so this practice went on for years, with the Association of Individual Investors (Stowarzyszenie Inwestorów Indywidualnych—the largest association of Polish individual investors) intervening and writing complaints to the European Commission (twice: in 2012 and 2017, respectively),Footnote 47 the European Commission starting the EU Pilot procedure with respect to the incorrect implementation of the Takeover Bids Directive,Footnote 48 the Polish capital market even witnessing the mandatory post-acquisition bid for one share of the target company (as the bidder explained in the documentation, the share subject to bid covered the right to 0.000044% of votes in the target company)Footnote 49 and the legal scholarship now and then pointing out the open secret of how takeovers are being executed in Poland.

The construction of the Polish takeover regime in 2005–2022 serves as an interesting example of how deficient rules may shape market practice and allow the protection established in the Directive to be circumvented in practice. From an economic perspective, the design of the regulation lowered the takeover premiums received by the aggregate of minority shareholders, due both to the reduction of tendered shares (some shares tendered by minority shareholders were not bought by the acquirer) and to the incentive not to tender the shares in the takeover bid (which was often considered pointless as the shares would not be bought anyway). A separate problem, in addition to the limited scope of the bids, was the lack of rules relating to the valuation of the actual price paid by the acquirer who indirectly purchased the target company.

4.3 Voluntary Bids on the Regulated Market and the Issue of Bids in the Alternative Trading System

As explained in Sect. 4.1 above, the mosaic of regulated transactions in large holdings covered mandatory bids, small bids (until 2017), delisting bids and cross-border bids. However, from a practical perspective, the provisions contained in the Act on Public Offering did not exhaust the types of transactions covering large holdings of listed companies. Developed by market practice and accepted by legal doctrine,Footnote 50 voluntary purchases emerged.

Those voluntary bids have been executed solely on the basis of general provisions of the Polish Civil Code, especially the freedom of contract principle. In short, the most common practice is that the purchaser presents the investors with an invitation for them to tender shares by making their offers to sellFootnote 51—such a legal construction allows the purchaser to retain great discretion with respect to accepting the offers presented by shareholders and executing the transaction. The only condition is that the bid must not fall within the scope of mandatory takeover regulation.Footnote 52

Despite the fact that it is difficult to say exactly how many transactions have been executed this way,Footnote 53 it is safe to say that, in time, voluntary bids have become a common element of the Polish capital market landscapeFootnote 54 (most commonly used for share buy-backs), with clear standardized templates (market-driven, as this has happened fully outside of the regulatory focus) and distinct know-how and procedures (especially with respect to the clear exclusion of capital market law provisions), executed by major brokers, investment firms and law firms. The practical difference between takeover bids and voluntary bids comes down to a lack of any minimal price in voluntary bids, a lack of a standardized schedule (timing of the bid), a lack of obligation to purchase shares, and a resulting lack of transparency. Therefore, the standard of protection of shareholder is significantly lower.Footnote 55

Another angle of voluntary bids is related to alternative trading (MTF) organized by the Warsaw Stock Exchange as NewConnect.Footnote 56 It is a market operating outside of the regulated market, with lesser regulatory standards, especially with no takeover bids regime applicable.Footnote 57 Still, similarly to the regulated market, voluntary bids are present on NewConnect,Footnote 58 mostly covering share buy-backs; nonetheless, a recent example of a takeover covering all shares of the target company conducted by carrying out a voluntary bid can also be found.Footnote 59 Whereas voluntary bids on the regulated market constitute a less transparent and unregulated choice, on NewConnect, those transactions often form an advantageous, more transparent alternative to creeping-in acquisitions. The Warsaw Stock Exchange itself also stated that the standardized voluntary framework for takeover bids would be desirable for introduction on NewConnect.Footnote 60

The parallel worlds of takeover bids and voluntary offers show the need for regulation of voluntary bids to be considered by the legislator. In Polish literature, it was argued that voluntary bids regulation is desirable as it would increase transparency and may remedy large price movements in case an investor purchases a large but non-controlling holding.Footnote 61 Regrettably, this opportunity was missed on all occasions, i.e., in 2015 (when the takeover regulatory reform was abandoned—see Sect. 5 below), in 2017 (when small bids were repealed) and in 2022, when the takeover regime was changed.Footnote 62

5 The Political Problem: The 2014–2015 Failed Takeover Law Proposal—Rules Caught in a Political Dispute

5.1 Background and Main Elements of the Draft Takeover Law

Given the described problems and numerous voices arguing for urgent amendment of Polish takeover law, after more than 8 years of regulation in force, a proposal emerged. It was drawn up at the Polish Ministry of Finance and submitted to the Polish Legislation CenterFootnote 63 (Rządowe Centrum Legislacji—RCL) under reference UD 144 on 3 July 2014.Footnote 64 The proposal, in contrast to all other previous or subsequent takeover rules, appeared to be well-designed, it addressed many problems that arose during the time the 2005 takeover regime was in force and took into account a comparative analysis and legislative solutions in other countries. The main features of the proposal were as follows: (1) thresholds of control set at 33 1/3% and 66% of votes;Footnote 65 (2) the requirement for a takeover bid (in case of both thresholds) to cover all remaining shares of the target company; (3) a default post-acquisition model of takeover bids;Footnote 66 (4) a regulatory framework on voluntary bids (for any amount of shares above 5%); (5) the requirement for the valuation to be conducted by a certified auditor in case of an indirect purchase of shares prior to the bid; and (6) additional provisions on cross-border bids and dual listing.Footnote 67

5.2 The Political Battle over the Inclusion of the Treasury’s Interest in the Takeover Law

As the draft proposal was arguably reasonable, to say the least, and ready to be processed by the Council of Ministers during the session of 7 October 2014,Footnote 68 the question regarding the background to and the reasons for the draft law eventually being abandoned (and therefore the provisions not being amended for the next 7 years) remains. The answer is that, like in any good horror story, the call was coming from inside the house.

On 6 October 2014, the Polish Ministry of the Treasury issued a formal letterFootnote 69 to the Ministry of Finance with the suggestion to include the interests of the Treasury (which is responsible for managing assets owned by the State, including the exercise of voting rights)Footnote 70 in the draft law. The Treasury observed that the stance of the Polish supervisor strengthened the approach according to which the Treasury (i.e., the State acting in its dominium capacity) is ‘treated as any other market participant’, which was apparently problematic and generated some further issues for the Ministry. The starting point of this discussion was the notion that capital market law extends the mandatory bid rule (as well as notification requirements) to entities which are dominant in relation to the acquirers, i.e., parent entities. In the opinion of the Ministry of the Treasury, the Treasury did not always have the means to know whether a State-controlled public company exceeded a threshold of control (or even the notification threshold of 5%) and did not have the means to force such a State-controlled company to carry out a mandatory bid or to sell the shares. Therefore, according to the Treasury, the State might itself be forced to sell part of its holdings in a given company, carry out a mandatory bid or lose voting rights.Footnote 71 Consequently, in the subsequent letter, the Treasury proposed that, in case of indirect acquisitions of shares, the State should be exempt from notification requirements, from the mandatory bid requirement and from sanctions related to losing voting rights in case of a breach of the takeover law regime. Alternatively, the Treasury also proposed for the State to be exempt from the notion of indirect acquisition of shares for the purpose of the whole Act on Public Offering.Footnote 72

It is very difficult to understand the alleged core risk that the Treasury could lose its votes or be forced to sell shares in case of indirect acquisition, as those sanctions generally refer to direct holdings, not indirect ones. If a State-controlled company were to purchase shares of a different company and violate the takeover regime, that company would be primarily liable and subject to sanctions (including loss of voting rights in the target company), save for a highly theoretical case where a State would directly own a minority stake in a company which would be a target of acquisition by another of the companies it controls (through a controlling stake) and the latter would ignore both mandatory bids, notification requirements, and the fact of joint holding in a capital group. From a wider perspective, it is also difficult to see how the State is different from any other shareholder which is a holding company controlling some minority or majority stakes in other entities; if anything, for many reasons, the State is arguably in a better position to monitor holdings and influence its subsidiaries. Finally, from the widest perspective, it is highly questionable whether, as the Treasury explained, the ‘public interest of the State Treasury constitutes an overriding and primary interest and for these reasons treating the State Treasury the same as another entity operating on the market is unjustified’.Footnote 73 This statement appears to be in contradiction not only with EU capital market law but also with the spirit of the OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned EnterprisesFootnote 74 and the basic ideas of a free-market economy.

In any case, the process moved forward, with a flurry of letters between several actors, primarily the Ministry of Finance (initiator of the draft), the Ministry of the Treasury, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as well as the Secretary of the Council of Ministers and the Council itself, which carried on for the next months. Over a dozen official documents were presented, with positions changing frequently. Due to a lack of agreement between ministries, the Council of Ministers rejected the examination, final approval, and submission to Parliament of the draft at least twice.Footnote 75 As a final result, the Ministry of Finance agreed to include the provision exempting State-controlled companies from mandatory bids and notification requirements in case of indirect acquisition of shares, under several further, rather unclear and confusing, conditions referring to independence of the decision-making process between the State and State-controlled companies.Footnote 76

But after that the trail goes cold. There was no further follow-up (at least there is no publicly available information on this), with the last official letter from November 2015 briefly referring to a discontinuation of work and return of the draft law to the Ministry of Finance due to the end of term of the Polish Parliament.Footnote 77 As a background, it should be kept in mind that very consequential Parliamentary elections were held in Poland on 25 October 2015, which caused a change of power in Polish politics. Given the Constitutional discontinuity principle (draft laws in Parliament which are not enacted before the end of term are abandoned), it would be highly doubtful if the draft could be enacted, given that it was not even submitted to Parliament in June 2015, still stuck in its pre-legislative phase (RCL). Therefore, the back-and-forth proposals from the Ministry of the Treasury, which lasted from October 2014 to June 2015, were, to say the least, a contributing factor to the failure of the 2014–2015 draft takeover regime amendment.

5.3 Conclusion. State-Owned Companies, Corporate Governance, and the Polish Legal System in Perspective

The above detailed description of the failure of the 2014 takeover law proposal serves as a prominent example of a much wider problem related to the intersection of dominium and imperium areas in Poland, the position and political functions of State-controlled companies and economic protectionism.

It is an open secret that State-controlled companies, including especially listed companies, very often serve as a political tool, being even more a part of the power structures than equal market participants and for-profit business enterprises.Footnote 78 Standard practices include micro-managing of the decision-making process, board nominations strictly in line with political key (with actual competences having at best tertiary importance) and rapid changes in board compositions,Footnote 79 allocation of budgets to affiliated actors (especially including friendly media) and many others, a common denominator being a self-reinforcing vicious circle between political and business favors. And as those effects have gotten arguably worse since 2015 with the currently ruling coalition (which is visible when looking at the number of political scandals related to State-controlled companies), one needs to admit that this toxic intersection of major listed companies and politics has always been present in the Polish system.

The other side of the coin—which supplements the above-mentioned decision-making, nominations and revolving-door problems—is the State acting in its capacity as legislator. Polish takeover law got caught in a typical politically motivated agenda, aimed at creating rules where State-controlled companies could be ‘more equal’ compared to the rest of the market. And the philosophy behind those actions has been very explicit, with the Ministry of the Treasury, acting in the pre-legislative process, emphasizing on several occasions that it was not desirable for Polish State-controlled companies to be subject to the same rules as other listed companies. The Polish legal system has already witnessed much of such favoritism and creation of tailor-made rules suiting State-controlled entities, a prominent example being the Polish Code of Commercial Companies that was amended in order to be in line with the articles of association of PKN Orlen S.A. (the crown jewel of Polish State-controlled companies), not the other way around.Footnote 80

From this perspective, the failure of the 2014–2015 takeover regime amendment is unsurprising for any observer of the Polish capital market. What makes this case slightly more ironic is that it is difficult to see any reasonable rationale for that political turmoil, even keeping in mind that the Polish legislator is more often than not inclined to take the interests of State-controlled enterprises into account when designing any rules. As described above, the risks identified by the Ministry of the Treasury were hypothetical at best; nonetheless, given the very brief analysis above, the final outcome of the 2014-2015 draft takeover law proposal is, regrettably, not surprising.

6 The Recent Problem: The 2022 Takeover Regulation

6.1 Background of the Legislative Process, Further Political Considerations and Main Aspects of the Reform

The next initiative concerning Polish takeover regulation emerged at the Polish Financial Supervision Authority (KNF). The draft of 28 September 2020 was forwarded to the Ministry of Finance and subsequently announced to the public by the supervisor.Footnote 81 However, from that point onwards, the legislative process became obscure.

Initially, after July 2021, the draft was processed as part of a wide legislative package reforming the financial market and strengthening minority investor protection (Draft Act on Financial Market Development).Footnote 82 After a few months, the takeover reform was suddenly shifted from the said draft to the draft law on covered bonds reform (implementing the EU Covered Bonds DirectiveFootnote 83), namely the Act amending the Act on Covered Bonds and Mortgage Banks as well as certain other acts (hereinafter: Amending Law of 2022).Footnote 84 Not surprisingly, the latter legal draft was at the very end of its pre-legislative path with the RCL, which allowed the drafters to fast-track the submission of the takeover reform to Parliament. Therefore, the takeover law was changed through a typical ‘back-door amendment’, at least in two respects: firstly, it was amended through a legal act concerning a different field (covered bonds); secondly, it was inserted into the said legal draft only at the last stage of the pre-legislative path. Sadly, the described process fits into the general concerns about the lack of transparency in the Polish legislative process, often raised by prominent public watchdogs.Footnote 85

Furthermore, unsurprisingly, this amendment has yet another important political angle related to State-owned enterprises. One of the prominent political plans of the Law and Justice party (in power in Poland since 2015) was the consolidation of major oil and energy companies in order to create a ‘National Champion’, i.e., a multi-energy empire-sized corporation with potentially global reach.Footnote 86 Putting the details of the multilateral consolidation aside, one of the key aspects of the whole transaction was the takeover of Lotos S.A. by PKN Orlen S.A.Footnote 87 In this regard, when the Draft Act on Financial Market Development was announced back in July 2021, many commentators pointed to the fact that the 50% threshold of control might allow the takeover to be carried out without a mandatory bid, as the State’s holding in the new company would be close to, but below, 50% of votes, sarcastically calling the proposed amendment to the takeover law ‘Lex Orlen’.Footnote 88 The merger indeed materialized, with the State controlling 49.90% of votes (as of December 2022), thus without the need to carry out a mandatory bid. The amendment was therefore at least well-timed and very convenient for the plan.

After submission to Parliament, the draft law was swiftly processed, with the Amending Law of 2022 being enacted on 7 April 2022 and entering into force on 30 May 2022. The main features of the new takeover regime are as follows: (1) one threshold of control, set at the level of 50% of votes; (2) post-acquisition mandatory bid model; (3) the mandatory bid always covering all of the remaining shares; (4) additional regulation for an optional voluntary bid, but only covering all of the remaining shares and only to be conducted with respect to a company listed on the regulated market; (5) transitional rules—certain requirements for investors holding between 50 and 66% of votes on the day the amendment entered into force; and (6) further rules on the calculation of the bid price.

At first glance, it may seem that the reform resolved some pressing issues, especially as regards the limited scope of mandatory bids (now dealt with, as all bids must cover all remaining shares) or the clarification of rules on establishing the price of mandatory bids. But that is not the case. The Polish legislator merely substituted old problems with a set of entirely new ones amid a façade of changes that do not make any desired difference. In effect, Polish takeover regulation is still to a large extent deficient and, essentially, may not fulfil its function of modern takeover regime for a developed capital market. The remainder of this section explains the problems arising from a recently enacted new set of rules, namely the far too high threshold of control of 50% of votes, the special provisions effectively fixing the holdings of main shareholders in many listed companies, and the absence of voluntary bids which would cover non-controlling stakes.

6.2 The Control Threshold Set at 50% of Votes

6.2.1 The Notion of Control in the Light of the Analysis of Ownership Structures in Poland

The purpose of the mandatory bid rule, as laid down in Article 5 of the Takeover Bids Directive, is to ensure the protection of minority shareholders by requiring the shareholder who acquires control over a listed company to make an offer (bid) to all other shareholders of that company to purchase their shares for an equitable price. In other words, in line with the Directive, whenever control is acquired, the mandatory bid must be carried out.

Against this background, the recently introduced threshold of control of 50% of votes in a company should be examined. As a starting point, it is worth looking at general observations regarding Polish ownership structures. Table 2 presents the basic characteristics of ownership concentration in Poland on 18 November 2022, namely the voting power of the largest and second largest holdings, the voting power of all significant (above 5%) shareholders of listed companies, the voting power of significant shareholders excluding the largest voting block, as well as the free float, with an additional separate row informing about the free float calculated to cover not only minor holdings but also holdings in possession of major Polish institutional investors.Footnote 89

In general, the Polish capital market follows the shareholding patterns dominant in Continental Europe,Footnote 90 with rather concentrated ownership structures and the presence of at least one major shareholder in close to all listed companies. From a comparative perspective, ownership structures in Poland are in line with those of large European markets, especially Germany and France.Footnote 91

Polish ownership structures predominantly remain on similar levelsFootnote 92 and became only slightly more concentrated throughout the last decade, with the mean average and median rising in case of the biggest holdings (around 2–3 percentage points) and all significant holdings (over 2 percentage points) in listed companies.Footnote 93 However, even the presented data of 2022 (with marginally more concentrated ownership structures) does not substantiate the threshold of control at 50%, as the average largest voting block equals only 45.46%. It should be observed that the median of the largest voting block equals 41.57%, which means that in the majority of listed companies the biggest voting block is below that figure (and, consequently, further below 50% of votes). Moreover, in roughly a quarter of listed companies (Q1) the biggest voting block is even below 30% of votes, which means that there is a non-negligible number of companies with more dispersed ownership. This observation is further strengthened by the analysis of the free float, especially when the holdings of institutional investors are included in the count—the third quartile at the level of only 49.15% informs that in close to a quarter of listed companies the majority of shares are held by small investors (below 5% of votes) together with institutional investors.

Moreover, the argument for the threshold of control to be set at a level lower than 50% is reinforced by the low value of cumulative holdings of other—besides the largest voting block—significant shareholders. On average, such investors jointly control only 23.31% of votes (with the median at 22%), with their holdings exceeding 28.94% of votes only in a quarter (Q3) of all listed companies. The value of those remaining large shareholders is relevant, due to the fact that minority (below 5%) shareholders generally rarely attend shareholders’ meetings and rather use the exit strategy, executing the so-called Wall Street walk and selling their holdings, instead of directly influencing the company through voting. Therefore, controlling more votes than the cumulative value of remaining large (above 5%) holdings implies, in most cases, de facto control,Footnote 94 because of the absence of minority investors during shareholders’ meetings related to collective action problems and rational apathy. In other words, due to characteristics of the capital market, the holding above 50% of votes—i.e., having more votes than all other shareholders—is rarely necessary to exercise control over a listed company; in the majority of cases, it is enough to be in control of a holding in excess of the joint holdings of all other significant investors.

There is also strong empirical evidence from Poland backing this approach—a 2014 study of all companies found that at the annual general meetings of listed companies the minority investors (each below 5% of votes) together held only 8.84% of votes on average, with the median at 3.98%. The flip side of this coin is that the mean average of the largest holding of 41.73% of total votes (in 2014), due to the absence of minority investors, increased to 65.74% on average at shareholders’ meetings (median at 66.37%).Footnote 95

The next stage of the analysis involves a more detailed examination of ownership structures in Poland. Recalling the concept of de facto control (understood as the case where the largest voting block is bigger than the joint voting blocks of other significant shareholders) and referring to the importance of looking at the voting power of the remaining (i.e., other than the dominant one) significant shareholders, the Table below presents the companies listed in 2022, divided into ten categories depending on the voting power of the main shareholder (Table 3). The data shows how many companies were in each category, how many companies in each category were subject to the de facto control of the main shareholder, and the average voting blocks of the remaining shareholders.

In November 2022, only in 162 out of 372 listed companies (43.55%) did the largest shareholder control more than 50% of votes, and in the remaining 210 (56.45%) the largest voting block was below that level. Moving forward, there were 106 companies (close to 29%) with voting power between 30 and 50% (78 above 30% of votes and 28 above 40% of votes, respectively). It is important to notice that in the majority of those companies (41 out of 78 and 24 out of 28) the main shareholder was able to exercise de facto control, as the cumulative remaining holdings were below the voting level controlled by the majority block. This means that in case of at least some of those companies, control could be acquired through the purchase of a holding below 50%, without the need to carry out a mandatory bid (under the current rules that established the 50% threshold of control).

What is of equal importance is the analysis of companies with a major shareholder in the categories above 50% of votes, namely between 50 and 60% and between 60 and 70%. There were 105 of such companies (above 28% of all companies), 48 above 50% and 57 above 60% of votes controlled by the main shareholder. In this case, the values of the joint holdings of the remaining shareholders should be looked at, which are relatively low, with a mean average and median in both categories in the range of 11–18%. This data informs that—again, at least in some cases—de facto control could be obtained by controlling a stake below 50%; consequently, the holding close to, but below, 50% of votes could be purchased by the acquirer through a deal negotiated outside of organized trading, with the remaining shares kept or disposed of otherwise.

It should be kept in mind that there are many scenarios regarding corporate governance, holding structures and relations between shareholders (including those acting in concert), and therefore the exact number of companies which could be controlled with a given voting block is impossible to be determined and is also variable over time. Nonetheless, the presented statistics show clear patterns of control on the Polish capital market and prove the existence of certain risks arising from the 50% threshold of control, which is undoubtedly set too high. This is also in line with the arguments presented by notable institutions during the legislative process.Footnote 96

6.2.2 Risks Related to the 50% Threshold of Control

The statistical analysis presented above allows drawing conclusions and pointing to several risks arising from establishing a threshold of control at the level of 50% of votes.

Firstly, which is the most intuitive, there is a risk of transactions involving a significant holding of less than 50% outside of the mandatory bid regime. In case a new controlling investor purchases a stake close to 50% in a negotiated deal without carrying out a mandatory bid,Footnote 97 the remaining shareholders will not have the possibility to have their share of the control premium, nor will they have the option to exit the company by selling their shares to the controlling shareholder.

Secondly, the problem may occur also in case of takeovers of companies with majority shareholders, especially those controlling between 50 and 70% of votes. In such cases, the controlling shareholder can transfer less than 50% of the shares to the acquirer, with the remainder minority share being disposed of or transferred to another party. Alternatively, the holding may be divided into two closely affiliated parties (outside the scope of acting-in-concert provisions), with control effectively changing without carrying out a mandatory bid. Admittedly, such a scenario may always occur (even with lower thresholds of control), but the higher the threshold of control, the more facilitative the framework for such practice.

Finally, the high threshold of control makes the market less transparent. As in many cases control may actually be transferred without acquiring a 50% stake, there might be change-of-control transactions made entirely outside of the takeover bids regime, either through negotiated deals or even through creeping-in over some period of time.Footnote 98

To sum up, it is likely that indirect acquisitions and takeover bids that are very limited in scope, which were dominant in 2005–2022, may be replaced with negotiated deals and acquisitions of just under 50% of votes. The takeover advisory industry is surely able to easily switch from the developed practices of setting up an SPV, conducting an indirect acquisition and carrying out a bid for less than 0.5% holding, to a new set of practices, involving structuring the transaction to gain effective control of just under 50% (likely around 49.5%, mirroring the earlier transactions covering typically 0.16%) of votes. The above-mentioned takeover of Lotos S.A. by PKN Orlen S.A. already serves as a first example.

6.2.3 A Proposed Framework—the Desired Threshold of Control

Finally, the question of what is the desired threshold of control, given the characteristics of the Polish capital market, should be answered. For several reasons, the most suitable threshold of control for the takeover regime appears to be 30% of votes in a listed company.

Firstly, looking again at the data presented in Table 3 above, the 30% holding is associated with a significant increase in a share of companies that are subject to the actual control of the main shareholder. De facto control is present in only around a quarter of the companies where the dominant shareholder controls a holding of 20–30%, and in more than half of the companies where the dominant shareholder holds between 30 and 40% of votes, with a further 85% in a group where the main shareholder holds between 40 and 50%. Put simply, the bigger the share of the main shareholder, the more likely it is that such a shareholder is able to actually exercise control, with a 30% holding being, empirically, an important breaking point, where control of a dominant shareholder starts to be very common.

Secondly, hypothetically, introducing a threshold of control below 30%, even though some companies (minority) in that category might still be controlled by a single investor, would be too extensive, as it would also capture many minority non-controlling holdings, impeding the allocative function of the capital market and creating unjustified burdens on investors. Even some of the second-largest holdings could be covered by such regulation (the Q3 of second-largest holdings in listed companies was close to 20% of votes). Moreover, even in rare cases (15 companies) where a controlling shareholder has between 20 and 30% of votes, such control appears to be unstable (the new controlling shareholder might emerge by acquiring a fifth or a quarter of votes), it could change relatively easily and such companies would be better described as having dispersed ownership (due to the large free float in case the dominant shareholder controls only around a quarter of votes) than by being controlled by a minority holding. Such threshold of control would require additional provisions, which would, on its own, increase the complexity of rules, covering scenarios where despite the crossing of the threshold, the investor would not acquire control, due to a lack of majority of significant holdings or even due to the fact of there being larger holdings within the same company.Footnote 99

Thirdly, the threshold of control of around 30% is in line with the majority of other European states,Footnote 100 which improves harmonization of regulatory practices and uniformization of takeover regimes within the single market. It may be reminded that the importance of a threshold of around 1/3 of votes was also noted by the European legislator in the first draft of the Takeover Bids Directive—according to the 1989 proposal, the threshold of control could not be set at a level higher than 33 1/3%. Due to difficult negotiations and truncation of the European takeover regime, this provision was abandoned; still, it may serve as another indication of the proper understanding of the notion of control.Footnote 101

Finally, as an additional argument, it is also worth looking at some more abstract economic cost-benefit analysis. From a policy perspective, the proper design of takeover rules can be understood as being aimed at two goals: (1) maximization of the percentage of companies which are de facto controlled by a single investor through a minority stake and are covered by the control threshold (change of control would require a mandatory bid); and (2) maximization of the percentage of companies which are not subject to the control of a single entity and are outside of the scope of the notion of control (change of control in those companies up to the level of the largest holding would not be subject to a mandatory bid). For the first of those criteria, the lower the threshold of control, the better (as there are more controlled companies covered by the scope of the notion of control), whereas, in contrast, for the second criterion, the higher the threshold, the better the outcome (as there are fewer companies which are covered by the regulation despite not being controlled by a single investor).

In 2022, 372 Polish companies were listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange, 209 of which did not have a majority (above 50% of votes) holding. Of those 209 companies subject to analysis in this part,Footnote 102 85 were subject to de facto control of the dominant shareholder (understood as being one investor having more votes than all other shareholders combined) and 124 were not. The question is what share (percentage) of the 85 de facto controlled companies would be captured by the notion of control (first criterion) and what share of the 124 non-controlled companies would be outside of the notion of control (second criterion) for each hypothetical threshold of control, from 0 to 50%.

In the simplest terms, this approach rests on the assumption that the company is subject to control when the main shareholder controls more votes than all other significant (above 5%) shareholders combined and that the notion of control (control threshold) should cover such companies. Within this framework, the analysis answers the following questions: (1) what percentage of companies which should be covered by the notion of control are indeed covered for each given threshold of control (first criterion); and (2) what percentage of companies which should not be covered by the notion of control are, in fact, outside of this notion for each given threshold of control (second criterion).

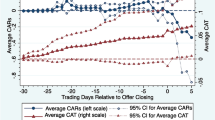

These criteria are reflected by two separate functions, subject to the trade-off described above, and, in consequence, the desired regulation should aim at maximizing the sum of the values of those two functions (the sum—which may be considered as a regulatory utility function—is presented as a dotted line in Fig. 1, scaled to range between 0 and 1, right hand side). The results of empirical analysis are presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1 shows that the optimum of the analyzed trade-off occurs when the threshold of control is set at the level of 31% of votes.Footnote 103 The optimal threshold of control, in the light of the presented cost-benefit analysis and simple regulatory utility function, is therefore around 30% of votes, in line with the initial statistical study of ownership structures and the comparative remarks presented above.

To summarize, one needs to acknowledge that there will never be a simple, unambiguous criterion or test allowing to establish what percentage of shares held in a listed company implies control over it. There are many different corporate governance systems and many more companies operating within them, each having its unique ownership structure and relations between major shareholders. Therefore, it is always, to some extent, a judgment call as to how to establish the criterion of control, which implies the requirement to carry out a mandatory bid. In this section, three different approaches have been proposed, referring to ownership structures, comparative analysis and regulatory cost-benefit analysis. None of those approaches is superior, rather, they are complementary, being different pieces of the same puzzle. Nonetheless, what is important is that all the presented approaches have produced exactly the same conclusion, pointing to the threshold of control of around 30% of votes.Footnote 104

6.3 Special Provisions Related to Major Holdings Existing on 30 May 2022

The 2022 takeover law reform contains further legislative solutions, which, after a closer examination, are unjustified and may create significant general problems for the functioning of the Polish capital market.

According to Article 28, sec. 5 of the Amending Law of 2022, if an investor holds more than 50% and less than 66% of votes in a listed company on the day the Amending Law entered into force (30 May 2022), the requirement to carry out a mandatory bid for all remaining shares arises in case the investor further increases their holding (even by one share). The laconic substantiation regarding this provision presented by the Polish legislator was that, due to the change of the mandatory bid threshold, some of the shareholders who now held more than 50% of shares had previously been obliged only to carry out a bid for up to 66% of votes; consequently, due to this change, some of these investors ‘would never be obliged to carry out the mandatory bid covering all shares’.Footnote 105

This reasoning is highly questionable. Firstly, the rule does not differentiate between shareholders who indeed carried out a mandatory bid for only up to 66% of votes under the previous regulation and those who had held their majority holdings since the beginning of the listing or acquired the stake prior to 2005; it may be the case that some controlling shareholders held their stakes since the establishment of the company or the IPO. Secondly, and more importantly, it is hard to define the provision’s exact purpose and who may benefit from it. The Takeover Bids Directive requires that a mandatory bid must be carried out in case of a change of control to protect minority shareholders. In the cases covered by the provision at hand, control had already been acquired, in many instances long before the triggering of the provision. The trigger event—further increase of the holding—is in no way related to the change-of-control transaction, as control was acquired earlier and there is no reason to require the shareholder to carry out a bid at this point in time. Moreover, the shareholding structure fluctuates, thus changing in between—many of the minority shareholders of companies subject to this provision purchased shares after control had been acquired; conversely, many shareholders who did not benefit from proper protection in one of the companies in question are no longer their shareholders. It is also important to keep in mind that, in case of the provision at hand, the price of the shares is subject to significant change between the time the control was acquired and the time of the takeover bid. As a consequence, according to current regulation, the bid is carried out now (not when the control was acquired), is addressed to current shareholders (not to those who held shares when the initial transaction took place), and is referenced to current market prices (which in many cases significantly differ from market prices at the time the change of control took place). It is very difficult to see how such a mandatory bid, years after control was acquired (if it was acquired through a transaction on the capital market at all), could have any protective function, and therefore the discussed provision is an example of a bureaucratic approach to the law-making process, with the designed rule not having any meaningful purpose for the market.Footnote 106

Noting that the rationale for the analyzed provision is doubtful, as a next step, the question of how many companies are covered by this regulation should be answered by examining the ownership structures on the Polish capital market once again. Figure 2 above presents the number of companies with a dominant shareholder controlling less than 50%, between 50 and 66% and more than 66% of votes, in November 2022.

The data shows that those special (known as ‘transitional’) provisions in fact create a major problem. In short, the regulation cements the holdings of major shareholders in over a quarter of all listed companies in 2022 (96 out of 372, which equals 25.81%). As the precise data on shareholdings on 30 May 2022 was not analyzed, the figure of approximately a quarter of companies subject to the provision at hand is fully in line with other research and the evolution of ownership structures.Footnote 107

Thus, flawed rules have created a significant burden for many major shareholders. It is difficult to judge how problematic this will be in the end, as such larger holdings are rarely actively managed; nonetheless, the Polish legislator managed to create additional meaningless regulation. Additionally, this provision strongly distorts the level playing field, as it only applies to companies listed on 30 May 2022. The more companies will be entering the market over the next years (as long as this provision is in force), the more entities there will be with different applicable rules, i.e., ‘old companies’, where a major shareholder cannot increase their holding and ‘new companies’, where any transaction of a shareholder already controlling above 50% of votes is fully permissible without restrictions. There are many further additional problems with those provisions, including the fact that they are part of the Amending Law of 2022 instead of proper capital market law and ambiguity as regards the exact scope of their application.Footnote 108

6.4 The Rules on Voluntary Bids—Old Problems and Acquirers’ New Clothes

Lastly, the legislator created a voluntary bids provision. In line with new Article 72a of the Act on Public Offering, the investor may voluntarily carry out a bid covering all remaining shares of a target company listed on a regulated market. Therefore, the main features of this regulation are as follows: (1) the voluntary bids regime only covers transactions for all remaining shares; (2) it is limited to the regulated market. These main features constitute the reasons why this design does not really introduce a new quality to the takeover regime, but instead represents a mere reshuffling of the previous norms, with ‘real’ voluntary bids still being outside of regulation.

As explained above (Sect. 4.3), the Polish law does not recognize bids for minor holdings, which could be introduced as a voluntary option for investors wanting to execute a relatively large, but non-controlling, transaction in a transparent and standardized way. Significant non-controlling holdings (above either 10% or 5% of votes) were subject to mandatory small bids regulation which was abandoned in 2017. On the other hand, legal practice developed so-called ‘voluntary bids’, the unregulated invitation for other shareholders to tender their shares to the bidder. There are reasons to at least consider more standardization with respect to large holdings, by introducing uniform bids, for both the regulated and the alternative market. Such regulation, as entirely voluntary, being an option for investors, might enhance transparency and good practices and, at least to some extent, remedy the parallel regimes of takeovers and the unregulated invitation to submit offers. This was also the line adopted in the 2014 draft takeover law and proposed by members of Polish academia and the Warsaw Stock Exchange.Footnote 109

Such regulation is non-existent. Instead, the Polish legislator created provisions which use the phrase ‘voluntary bids’ but really constitute a different legal institution. The reason for these rules is that, prior to 2022, the normative model provided for default pre-acquisition bids with post-acquisition bids as a regulatory exception. In this sense, every pre-acquisition bid was ‘voluntary’ as it was conducted by an investor as a way to cross one of two thresholds of control. In the 2022 rules, the legislator switched (in line with most European models) from default pre-acquisition bids to default post-acquisition bids; this created a need to also cover the scenario of crossing the threshold of control (now at 50% of votes) by carrying out a bid, which was a default way before 2022. Therefore, from a practical perspective, hardly anything has changed: there is a possibility of crossing a threshold of control through a pre-acquisition bid (the same as before, only now it is called ‘voluntary bid’) or crossing a threshold otherwise and carrying out a post-acquisition bid (the same as before, the only difference being that before 2022 such purchase had to be indirect—through an SPV—and can now be both direct and indirect). Therefore, as in Andersen’s tale about the Emperor and his new clothes, the legislator gave acquirers on the Polish capital market new clothes, which, under closer inspection, are nothing new—it involves substantively the same old provisions with a slightly different structure.

The Emperor in Andersen’s tale was in fact naked; there were no clothes covering him, in much the same way as there are no provisions for voluntary bids for partial holdings in Polish takeover law. The notion of voluntary bids in Poland is limited to its definition, but these bids are not the ‘actual’ voluntary bids which should be introduced into Polish capital market law. The regulation is therefore still deficient.

7 Concluding Remarks

A lot has changed in the last 30 years, as the Polish economy has undergone a major economic transformation from a centrally planned economy towards a key financial center in the region. Regrettably, what remains constant throughout the last three decades are the flawed rules and the Polish legislator’s lack of understanding of a proper design of the takeover regime. This area of Polish capital market law serves as an interesting example of the intersection of a poor legal and regulatory structure, political considerations and protectionism towards State-owned enterprises, as well as an obscure legislative process.

In this light, this article showed the evolution of the Polish takeover regime. It started with a brief description of the early years of the reactivated capital market and its regulatory framework. It then presented, in detail, the flawed provisions which were based on two thresholds of control and the possibility of carrying out takeover bids limited in scope (in most cases covering only a fraction of a percent of shares). On the basis of statistical research, it was demonstrated that such a limited bid was dominant practice in the years 2005–2022. The paper also elaborated on the issue of the reasonable draft takeover law of 2014, which, due to intragovernmental discussions and attempts to strengthen economic protectionism by favoring State-owned enterprises, never entered into force.

Finally, the paper scrutinized the new takeover regulation enacted in 2022. There are several problems with the new provisions, the most important one being the too-high control threshold of 50% of votes. It was demonstrated that in the light of the ownership structures of Polish listed companies (the results of statistical research were shown in detail) the actual control over a company is most often exercised with lower holdings. Consequently, the Polish legislator substituted old problems (takeover bids significantly limited in scope) with new ones, related to the possibility of acquiring controlling stakes of less than 50% of votes, entirely outside of the mandatory bid rule and current takeover regime. In addition, according to the new rules, a shareholder who controlled between 50 and 66% of votes on 30 May 2022 is obliged to carry out a mandatory bid in case their holding increases even by only one vote. This provision creates a considerable burden, as it cements the majority holdings in a large number of Polish companies (around a quarter), with no clear rationale or substantiation. Furthermore, a desired regulation of bids covering non-controlling stakes is still missing, with yet another opportunity to create such provisions wasted. Last but not least, this defective reform was introduced as a typical back-door amendment, through an unclear legislative process with possible political factors at play.

Time will tell to what extent the risks arising from the new regulations will materialize and what will be the future of Polish takeover regulation. However, given the past practices and the fact that it took the Polish legislator around 17 years to introduce new, still deficient, provisions, there are hardly any grounds for optimism in this matter.

Notes

Data as of 7 November 2022; general statistics are available at the Warsaw Stock Exchange website, see Warsaw Stock Exchange (2022).

Tychmanowicz (2020).

Warsaw Stock Exchange (2008), p 22.

Directive 2004/25/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 April 2004 on takeover bids, OJ 30.4.2004, L 142/12, hereinafter: Takeover Bids Directive.

Pennington (1974).

Johnston (2007), p 422.

The report contained an appendix with a proposed draft of a directive, see Pennington (1974), appendix.

Proposal for a Fifth Directive on the coordination of safeguards which, for the protection of the interests of members and outsiders, are required by Member States of companies within the meaning of Article 59, second paragraph, with respect to company structure and to the power and responsibilities of company boards, OJ C 131/49, 13.12.1972.

See further on the Fifth Company Law Directive, e.g., Gelter (2017), pp 18–19.

Proposal for a Council Regulation on the Statute for a European Private Company, Brussels, 25.6.2008, COM(2008) 396 final.

Official Journal of the European Union, Vol. 57, C 153, 153/6.

On this subject, see Mukwiri (2020).

See the Proposal for a Thirteenth Council Directive on company law concerning takeover and other general bids, COM(88) 823 final, 16 February 1989.

On the proposed instruments, which were aimed at facilitating takeovers and creating a level playing field, see especially the report released after the initial draft was rejected by the European Parliament: Winter et al. (2002).

The extensive discussion on the policy aspects of the mandatory bid rule is generally outside the scope of this paper. In essence, some commentators argue that, due to increased costs for the acquirer, the rule can impede certain transactions and thus act as an anti-takeover measure favoring incumbent management (see especially Hansen (2011), pp 30–31, and Enriques (2004), pp 448–449). On the other hand, it is also argued that the mandatory bid rule increases the efficiency of the market for corporate control by preventing inefficient transactions (e.g., Schuster (2013), pp 529–563) and by providing fairness and an additional layer of protection to non-sophisticated investors (e.g., Jennings (2005), pp 63–64). The trade-offs and policy choices are acknowledged and further elaborated in European Commission (2013), p 29.

European Commission (2013), p 38.

Several studies have been released by the EU bodies, providing comparative details on the implementation of the Takeover Bids Directive, namely: (1) the most recent report, which was released by ESMA in 2014 and updated in 2019: ESMA (2019); (2) the most detailed and comprehensive report on the implementation of the Takeover Bids Directive, issued in 2013: European Commission (2013); (3) a summary of the report contained in a Communication from the Commission: European Commission (2012); and (4) an initial analysis of the implementation of the Directive, released in 2007: European Commission (2007).

This combined approach can be found, for instance, in Spain (actual appointment of the majority of the board, in addition to the quantitative threshold of 30% of votes), Estonia (right to appoint or remove the majority of board members, or other dominant influence or control over the company) and India (a set of qualitative criteria in addition to a relatively low threshold of 25% of votes). For European jurisdictions, see ESMA (2019), pp 13–14; regulations in India have been described in: Varottil (2015), pp 221–230.