Abstract

In the UK both the Bank of England and the Financial Conduct Authority have recently carried out experiments using new digital technology for regulatory purposes. The idea is to replace rules written in natural legal language with computer code and to use artificial intelligence for regulatory purposes. This new way of designing regulatory rules is in line with the UK government’s vision for the country to become a global leader in digital technology. It is also reflected in the FCA’s business plan. The article reviews the technology and the advantages and disadvantages of combining the technology with regulatory law. It then informs the discussion from a broader perspective. It analyses regulatory technology through criteria developed in the mainstream regulatory debate. It contributes to that debate by anticipating problems that will arise as the technology evolves. In addition, the hope is to assist the government in avoiding mistakes that have occurred in the past and creating a better system from the start.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Technology changes society. Distributed ledger technology (hereinafter also referred to as ‘DLT’) has been described as having the potential to disrupt how and by whom financial and other services are delivered and regulated.Footnote 1 Artificial intelligence already does and will increasingly shape our society in the future.Footnote 2 The law needs to adapt to this change and can benefit from it.

This is at present particularly true for financial regulation. Recent advances in computer science could produce technological solutions that facilitate financial regulation.Footnote 3 Such solutions have been referred to as ‘regulatory technology’. Regulatory technology has been described as a game changer.Footnote 4 It is said to have the potential to streamline compliance and increase efficiency for both the regulator and the regulated entities in financial markets.Footnote 5 It could enable the regulator to supervise the entire population of regulated entities relying on deep evidence delivered in real time. It could free up regulatory capital or remove the need for it altogether. Brexit gives the UK greater freedom to develop a framework of its own. The government is keen for the UK to become a global leader in digital technology.Footnote 6 Now seems like a good time to incorporate new digital technology into regulation.

A significant amount of academic work has been done on FinTech, the combination of digital technology with the delivery of financial services.Footnote 7 The use of technology for the purpose of financial regulation has not yet received a substantial amount of attention.Footnote 8 This is not surprising as the process of integrating digital technology into regulation is still in flux. Recent developments, however, indicate that regulatory technology has reached a stage in its development where it benefits from broader analytical scrutiny.

An increasing number of technology focused start-ups are attempting to develop regulatory technology.Footnote 9 Regulated entities are interested because the increase in regulatory requirements following the financial crisis has made compliance costly.Footnote 10 Regulators are interested because they too want to save money.Footnote 11 They also would like to promote growth and support innovation.Footnote 12 In the UK both the Financial Conduct Authority (hereinafter also referred to as ‘FCA’) and the Bank of England have recently carried out experiments involving the use of new digital technologies.

The aim of this article is to examine the implications of using technology for regulatory purposes. The article also informs the discussion from a broader perspective. It brings the area under the scrutiny of the mainstream regulatory debate. It also contributes to that debate by anticipating the problems that will arise as the technology evolves. In addition, the hope is to assist the regulator and regulated entities in avoiding mistakes that have occurred in the past and creating a better system right from the start.

In Sect. 2 the technology will be examined. After that two potential use cases for regulatory technology and their effect on the regulatory landscape will be discussed: digital reporting and artificial intelligence as a risk management tool. The process of reporting individual data points could be organised through distributed ledger technology and combined with artificial intelligence. In the future, artificial intelligence could be incorporated into prudential regulation to monitor the records of a broader range of transactions or perhaps even the entire IT system of regulated entities (Sect. 3). Then criteria that have been developed to scrutinise regulatory quality will be mapped onto regulatory technology (Sect. 4). Section 5 will take the analysis to a more particular level by examining how the challenges posed by the integration of digital technology into regulation vary according to regulatory strategy. The paper will discuss command regulation, self-regulatory models and meta-regulation. It will also analyse an activity-based regulatory model. Section 6 will conclude and make recommendations.

The main conclusion of the article is that regulatory technology poses different challenges depending on the regulatory strategy adopted by the government. The technology itself, however, serves those who pay for its development. It does not deliver a silver bullet that will make it easier for regulated entities to align their business interests with the public interest.

Another important point is that the role of technology providers will have to be kept under review. As regulatory technology is integrated into regulation the providers of technology become positioned as gatekeepers but do not necessarily have the right incentives to operate in the public interest. The problems that can emerge are exacerbated by the fact that there is a potential for the oligopolistic market that is currently dominating data analysis to move into the realm of regulation.

If the regulator integrates new digital technologies it will need to retain a substantial amount of oversight over its design to be able to retain democratic legitimacy and accountability as well as operate on the basis of due process.

2 The Technology

At present, neither the Financial Conduct Authority nor the Bank of England have adopted or endorsed any particular technological solution. They are, however, holding themselves ready and are proactively engaging with market participants.

In the UK the FCA launched its ‘Project Innovate’ in October 2014.Footnote 13 The project includes regulatory technology.Footnote 14 The Bank of England has created a Fintech Hub which incorporates the work that the Bank has carried out in relation to integrating new digital technologies into its own organisation.Footnote 15

Because regulatory technology is in development it is worth considering more broadly what those creating such tools are using for inspiration. There are a number of new digital technologies which can support regulatory aims. These technologies and their components will be introduced in this section.

2.1 Distributed Ledger Technology

Distributed ledger technology was developed for Bitcoin which is a form of money that is not backed by the government of any state. It was designed as a peer-to-peer system that enabled individuals to transfer money without using banks. A record of which individual owns how much money is shared publicly between the participating individuals who each hold an identical copy of the entire record on their own home computer. This record is referred to as a distributed ledger. Participants are not identified by name but by a number which is referred to as ‘public key’. The ledger is updated by consensus of the participants. Each participant has a passcode referred to as ‘private key’ to access their own money.

Distributed ledger technology can be combined with what is referred to as a smart contract. This is a computer programme which runs on a distributed ledger and automatically transfers money when certain pre-defined events occur. For example, it pays out a certain sum at regular intervals or when an index reaches a certain level.

Bitcoin started as a libertarian project but the technology also lends itself to non-libertarian applications. The Bitcoin ledger itself has, since it first started, developed into an intermediated system where those participants who maintain the register are no longer individuals but have become similar to custodians.Footnote 16

A distributed ledger could be used by banks or other financial services providers.Footnote 17 The Bank of England has, for example, conducted tests to determine if the technology could be used for its inter-bank settlement system. It concluded that at present the technology is not mature enough but is ensuring that its new RTGS system will be compatible with the technology.Footnote 18

The technology can also be used to record ownership of assets other than money.Footnote 19 The use of distributed ledger technology for assets is currently being explored by start-ups as well as incumbent market participants. The FCA have published a discussion paper in April 2017 and a feedback statement in December 2017.Footnote 20 If market participants develop a DLT system through which they hold and transfer financial assets, this could be connected with regulatory technology. The regulator could become a participant enabling it to monitor, supervise and audit trades including smart contracts.Footnote 21

A distributed ledger can also be used to share information. This component of the technology could be of interest for regulatory purposes. We will see below that the FCA has conducted experiments to use the technology for regulatory reporting.

2.2 Artificial Intelligence

It is difficult to define ‘intelligence’ and there is no generally accepted definition of ‘artificial intelligence’.Footnote 22 Artificial intelligence includes software that is able to play games such as chess or go calculating its way through potential combinations of moves.Footnote 23 It also includes software that perceives and reacts to the surrounding environment enabling it to control cars autonomously.Footnote 24 For the purposes of financial regulation two applications of artificial intelligence are of interest: machine learning and natural language processing.

2.2.1 Machine Learning

Financial regulation could benefit from software that reviews large amounts of data to identify patterns that may indicate unusual activity or previously unnoticed correlations indicating that certain risks may have emerged.Footnote 25 Such programmes are already used for fraud prevention purposes where they monitor credit and debit card transactions. They are sometimes referred to as machine learning.

Risk is also visible in communication patterns. In a recent study the authors have, for example, analysed emails sent by 144 senior Enron employees in the lead up to the company’s collapse. They found that in addition to certain terms that appear in such emails and that indicate emerging problems, the length of emails and their frequency are indicators of escalating problems.Footnote 26 It would be possible to use this form of analysis for regulatory purposes.

2.2.2 Transforming Natural Language into Computer Language

Connected with machine learning is a technique in computer science where computers process speech or written text created by human beings. A type of this form of technology is used by Google Translate and by digital assistants such as Alexa, Google or Siri. It is also used by businesses to operate telephone systems or customer service centres.

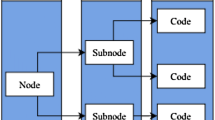

For financial regulation, similar technology can be used to read rules and translate their content into computer programmes which then process data. At present the software is not yet sufficiently advanced to adequately cope with the full spectrum of subtleties used in human language. For this reason, a double translation process is evolving. In a first step natural language is transformed into a machine-readable version. This is similar to the process of adapting natural speech to the requirements of digital assistants or telephone operators. This machine-readable version is then processed to create a programme that automates certain regulatory tasks.Footnote 27 We will see below that this technology has recently been used in experiments carried out by the FCA.

3 Combining Technology with Regulation

In the previous section, new digital technologies have been introduced. In this section and in the remaining sections of this paper two potential ways of integrating these technologies with financial regulation will be discussed. The first use case builds on the computer science experiments currently carried out by the FCA. The second use case takes the current experiments as a starting point but is, for the time being, science fiction. It investigates the implications of using artificial intelligence as a risk management tool.

3.1 Digital Regulatory Reporting

The FCA are currently working with the Bank of England to explore whether digital regulatory reporting could reduce the ‘compliance burden’ affecting regulated entities.Footnote 28 In what are referred to as ‘TechSprints’ they explore using distributed ledger and language processing technology for ‘regulation, compliance procedures, firms’ policies and standards together with firm transactional applications and databases’.Footnote 29

At present the FCA and the Bank of England operate a database referred to as Gabriel.Footnote 30 Regulated entities collect their internal information, produce an electronic report and submit it to Gabriel. This involves manual processes which take time and are prone to mistakes. When the FCA receives the reports they verify completeness, consistency and compliance with the requirements.Footnote 31 Regulated entities as well as the regulator believe that they would benefit from a system that removes manual processes from regulatory reporting.Footnote 32 Gabriel, which came live in 2011, is likely to benefit from an upgrade in the not-so-distant future. Brexit means more freedom for the UK to develop new ways of regulating financial services and the government has a vision for the country to become a leader in digital technologies.Footnote 33

Distributed ledger technology has shown ways of sharing information. A distributed ledger could be created that contains the records for reportable transactions of all regulated entities. This ledger would serve as an internal booking system as well as a reporting device. Regulated entities would record transactions as they do now but instead of doing this on an internal database the record would be made on a distributed ledger. The regulator would be supplied with direct access to that ledger. Cryptography would ensure that while the records are visible to the regulator other regulated entities do not have access to business sensitive information from their competitors.

In recent experiments carried out by the FCA and the Bank of England language processing was used to develop software to run on such a ledger. It translated reporting requirements contained in the FCA Handbook from English into computer code.Footnote 34 It mapped the ‘regulatory requirements directly to the data […] creating the potential for automated, straight-through-processing of regulatory returns’. In Februrary 2019 a second pilot phase was launched.

At present the conclusions are that, from a computer science perspective, it is possible to translate rules on mortgage reporting written in English into a machine-readable and executable form. This machine-readable version of English can be used to create software. That software then retrieves data and creates a report for the regulator from a distributed ledger. That software can also be updated reflecting regulatory changes.Footnote 35 In the future, the regulator and regulated entities could share the records of reportable transactions enabling the regulator to access the information on these as it is held directly with the regulated entities. Regulated entities no longer submit reports. The regulator would help itself to data on transactions. It could even use software with a ‘smart contract’ functionality that identifies breaches, makes suggestions for sanctions or perhaps even automatically issues fines.Footnote 36 The focus of the next stage of project is on questions of economic viability, the possibility of third party providers and data definitions.Footnote 37

3.2 Machine Learning As a Risk Management Tool

It would be possible to extend the access for regulatory software to more than just specific transactions. Such software could access the records of all transactions entered into by regulated entities. This could be combined with machine learning.Footnote 38 Software could be developed that autonomously analyses transactions as they are recorded by the regulated entity. The analysis could be extended to the entire information system operated by a regulated entity. In addition to transaction records regulatory software could monitor other data files, email and voice communication carried out by employees of regulated entities. This would be a step up from keeping records of telephone conversations and email exchanges and would have to be done through a form of analysis that is consistent with protecting the personal information of individuals.Footnote 39

The software could be taught to autonomously identify risk as it emerges. Regulators and regulated entities would be able to locate and address problems at an earlier stage than they are now. The software could be integrated into the regulation of micro-prudential risk management as a tool helping to prevent individual firms form failing.Footnote 40 There is a suggestion that this might liberate regulatory capital. Capital requirements are currently triggered by an analysis of the asset profile of a bank. In the future the trigger for capital requirements could be the product of machine learning analytics allowing a broader and deeper range of information to be processed in the analysis of financial institutions.Footnote 41

This could be combined with a smart contract functionality which, like in the first use case, automates enforcement.

3.3 Advantages and Risks

In this subsection, the advantages and risks associated with the technology will be examined. Regulatory technology could make compliance easier for regulated entities. It could make regulation nimbler and precise and supply the regulator with more accurate and real time information. It could support regulatory processes by informing them through data-based analysis. Levels of standardisation may increase. Like any form of innovation, new technology is associated with risks that are, for the time being, unknown. Regulatory technology introduces a new type of service provider to the regulatory environment.

3.3.1 Making Compliance Easy

At present the FCA regulates the outcome, rather than process, in accordance with the statutory objectives of ensuring consumer protection, market integrity and competitive markets. The regulator acts on the basis of legislation. Based on their mandate they write rules in the version of English that is customarily used in a legal context and publish them. The FCA is neutral towards the technology used by the entities it regulates.Footnote 42 It does not matter how firms maintain records or organise themselves as long as they produce the reports required and comply otherwise with rules contained in the Handbook and its underlying legislation. Regulated entities carry the risk of interpreting the rules and putting in place a system that ensures that they comply.Footnote 43 They employ human beings who read and interpret these regulations. Each entity takes a view on how to implement them including any technology that is used to facilitate compliance. They may seek legal advice and/or liaise with the regulator. Compliance is ultimately assessed by the courts.

Regulatory technology could make compliance easier. Rather than writing rules in legal English the regulator could write rules in machine-readable English or prescribe particular software applications. This would leave less room for regulated entities taking the wrong approach.

Making compliance straightforward can help to increase levels of compliance.Footnote 44 Realistically however, irrespective of the tools used for regulatory purposes regulated entities have a choice. They can either observe regulatory requirements or alternatively they can appear to be compliant by working out how to avoid detection from the regulators including their technology.Footnote 45

3.3.2 Making Regulation Nimble

At present when the rules are updated each entity reads the new regulations, takes a view on how to implement them and updates their systems accordingly adding data fields or making other modifications.Footnote 46 This makes it hard to change course. Regulatory software could simplify the process. Adapting to regulatory change could become as simple as installing a software update.

Regulatory technology can also assist with adapting regulation to changes in the market. Machine learning can help to analyse regulated entities and markets and identify patterns that may indicate the emergence of risk requiring an update of regulatory requirements. They may find, for example, that certain practices are emerging and incorporate these into their monitoring activity.

3.3.3 Making Regulation More Precise

Computer code is more precise than natural language. The process of translating legal English into machine-readable English and onwards into computer code will make rules more precise.Footnote 47 Replacing ambiguous legal terms with precise computer code changes meaning. By becoming more precise the scope of a rule narrows. Removing ambiguity can also cause meaning to shift away from its original focus. In addition, computer code has its own albeit more limited ambiguities. Coding is a process of working with the limitations of the respective programming language.Footnote 48 Creating regulatory software, while being an exciting exercise in computer science, also involves policy choice.Footnote 49 A decision needs to be made on how individual terms are translated and also more broadly on which elements of the regulatory framework will benefit from higher levels of precision.Footnote 50

3.3.4 More Accurate and Real-Time Information

Digital reporting would change what kind of and how quickly information is available to the regulator. It could give the regulator access to information as it is recorded internally by regulated entities. The regulator would receive more accurate information than it does now. It would be supplied with better quality evidence for its decision making. It would also be informed about transactions as soon as they are booked on the shared record and thus receive a close to real-time picture on the transactions entered into by regulated entities.Footnote 51

3.3.5 Data-Based Analysis

The available evidence can be analysed through artificial intelligence.Footnote 52 Machine learning can process large amounts of information. It can help to identify risk in data supplied by regulated entities. This can alert the regulator and regulated entities to problems that appear to be emerging. It could also enable the regulator to closely supervise the entire population of regulated entities rather than just a selected number.Footnote 53 This has been described as leading to a profound transformation of the approach to regulation.Footnote 54 This analysis also has the potential to be extended to reveal macro-economic interconnectedness allowing for better monitoring of macro-prudential risks.Footnote 55 This may also open up the possibility for personalised regulatory interventions.Footnote 56

There is a risk, however, that machine driven analysis of facts revealing themselves in data becomes associated with an aura of objectivity and analytical prowess that does not reflect the scope of the evidence the analysis is based on. The problem is not the analysis but the underlying data set. It is easy to overlook the limitations of data-based analysis. Diagnostic tools that were based on data collected from male individuals can, for example, cause doctors to overlook female patients presenting with heart attacks.Footnote 57 In the context of regulation similar mistakes can occur, leading the regulator and regulated entities into a false sense of security.

3.3.6 Standardisation and Systemic Risk

At the moment, each regulated entity develops its own understanding of how to comply with regulatory requirements. The current rules allow for different interpretations which are all equally lawful. This facilitates a variety of business models within the financial services industry. If a highly standardised financial technology is used across regulated entities consistency increases.Footnote 58 This can reduce room for variety and facilitate herding. There is therefore a risk that regulated entities become increasingly similar causing systemic problems to arise.Footnote 59

3.3.7 Technological Risks

Regulatory technology takes advantage of computer science tools that are relatively new. Our knowledge and understanding of any new technology is initially and invariably limited. In addition, it combines computer science with law. Those trained in law do not normally know about the characteristics and limitations of computer software. Those trained in computer science are not normally familiar with the scope and subtleties of legal terms. Neither group is well placed to anticipate problems that may arise when the two are combined. They may not even be in a good position to appreciate what it is they do not know. This makes it difficult for either group of experts to at least ask the right questions.

One example are potential errors in the software.Footnote 60 Lawyers are not in a good position to imagine fact patterns. Computer scientists can imagine much better what could go wrong. But complex software tends to be opaque and it can be difficult even for computer scientists to predict outputs.Footnote 61 In particular, artificial intelligence can operate in ways that are unforeseen by programmers.Footnote 62 While being better placed than lawyers to predict potential problems, computer scientists are, however, not in a good position to imagine the implications of these problems for the legal context.

Another example is discriminatory bias. Biases present in the existing data set perhaps resulting from manual inspection regimes can easily be converted into automated biases.Footnote 63 Machine learning operates on the basis of black box decision procedures which makes it very difficult to work out even for computer scientists whether the outcome is biased and in what direction the bias is directed to.Footnote 64

More generally it is impossible to predict how regulatory technology will interact with the financial system. It may allow us to better manage risk leading to more stable financial institutions or it may turn out to steer us in the wrong direction.

3.3.8 The Role of Technology Providers

It is possible for the regulator and for regulated entities to develop their own bespoke software. That is, however, not likely. Neither are necessarily interested in or well-placed for becoming software developers. Pooling their resources, market participants have tried to co-operate to develop distributed ledger technology. They have set up R3. This has not had much success. The interests of industry participants appear to be too diverse to allow for the development of common technology.Footnote 65

It is more likely that regulatory technology will introduce a new type of participant into the regulatory environment. It has been mentioned briefly at the beginning of this article that there is, at present, a vibrant market of start-ups who are developing regulatory software.Footnote 66 RegTech events are populated by representatives from these businesses.Footnote 67 It has been recommended that these market participants could be incentivised to engage in the development of regulatory technology by allowing some providers preferential access if only for a limited time.Footnote 68

Special privileges for technology providers should be approached with caution. Alongside a start-up community a small number of large companies currently dominate the market for data analysis and artificial intelligence. They are potentially also interested in serving the financial services industry. One of their strategies for growth is to identify and acquire smaller technology companies.Footnote 69 They bring business interests of their own to the table which do not necessarily align with the public interest.

More generally we should be mindful of the problems that have in the past arisen in relation to credit rating agencies whose ability to act as gatekeepers was severely affected by the business interests.Footnote 70 We are seeing similar issues in relation to auditors whose business model has made it difficult for them to keep up their professional scepticism.Footnote 71

4 Quality of Regulation

In the previous section, the advantages and disadvantages of the technology have been discussed. In this section, regulatory technology will receive scrutiny from a broader analytical framework. When considering how new technologies could be integrated into regulation a natural starting point is to revert to criteria that have been developed to evaluate the quality of regulation.Footnote 72 These are democratic legitimacy, accountability of the regulator, fair, accessible and open procedures, expertise and efficiency. In addition, good regulation should focus on achieving outcomes rather than technical compliance.Footnote 73 In the following subsection the use cases for regulatory technology highlighted in this paper will be analysed against these six criteria.

4.1 Democratic Legitimacy and Accountability

First, regulation should be supported by legislative authority. The acts of the regulator need to be legitimised by a mandate from a democratically elected parliament. The requirement for democratic legitimacy also affects the breadth of the mandate. For example, a statute that requires a regulator to collect reporting information on mortgages to ensure lending is being carried out in accordance with capital and other regulatory requirements, gives more specific legitimacy to the regulator than a statute which simply instructs the regulator to ‘promote financial stability’.Footnote 74

Second, there should be an appropriate scheme of accountability. This criterion is connected with democratic legitimacy. If a regulator has a wide mandate involving a significant amount of discretion, it is all the more important for its decision making to be subject to oversight from democratically legitimated institutions. Accountability may be established by involving a parliament or other democratically elected body in the appointment or removal of leading decision makers working for the regulator. It may also be effected through the judiciary.Footnote 75

The creation of software that automates the reporting of specific data points involves technology providers making a decision on the scope of terms that have been expressed in natural language. This does not create problems for democratic legitimacy or accountability if the onus of identifying a particular programme remains with regulated entities. They would do so at their own risk. At present, they instruct lawyers and programmers to assist with developing a compliant IT solution. Regulatory software can help both types of service providers or perhaps even replace some of their work.

Democratic legitimacy and regulatory accountability need to inform, however, the extent to which the regulator can out-source rule-making to technology providers. If the regulator decides, for example, to issue or endorse regulation in machine readable natural language or in computer code, it needs to keep in mind that democratic legitimacy and accountability limit its ability to delegate the judgement involved in the translation process to third party providers. In particular, the potential involvement of large multinational technology providers in writing financial regulation will require special attention. Allowing private providers wide discretion in making design choices for regulatory technology could lead to an unwarranted ‘outsourcing’ or even ‘privatisation’ of the regulatory process,Footnote 76 creating the risk of undermining sovereignty, and positioning it in a grey zone from a constitutional law perspective.

Moreover, regulators need to be acutely aware that the limitations of data driven analysis is easily overlooked. Overlooking these may not only cause them to overlook problems. It may also cloud their ability to exercise judgement in accordance with democratically legitimated rules. Regulatory software should therefore be incorporated into the procedures operated by the regulator in a way that enables and encourages decision-makers to understand the scope of the data on which the analysis is based and preserves their ability to act in line with their democratic mandate exercising independent and accountable judgement.Footnote 77

Likewise, functionalities automating enforcement based on data-driven analysis need to be designed in a way that ensures that the regulator remains in control of the process.

4.2 Fair, Accessible and Open Procedures

A regulator may also claim legitimacy if it uses fair, accessible and open procedures. Due process is recommended both at the point of setting policy and writing regulation and at the point of enforcement.

For policy setting and for the writing of regulation, trade-offs need to be made between allowing affected parties to participate and implementing the legislative mandate. Regulators operate in a polycentric environment. The different participants have different claims to legitimacy and engage in variety of regulatory conversations. There are conflicting demands that are difficult to reconcile.Footnote 78

Consultation is important. Regulation is the product of a regulatory conversation that allows the different constituencies to articulate their concerns and interests. Too much participation, however, may lead to less effective policy-making and eventually a stagnation of the regulatory system.Footnote 79

In relation to regulatory technology the FCA is carrying out a public consultation at the moment. With any consultation, the problem arises that better funded market participants are better able to participate actively in this process.Footnote 80 The regulator needs to ensure that this does not lead to regulatory capture. Capture occurs when the regulator prioritises the interests of regulated entities over the public interest.Footnote 81

For regulatory technology, the setting of policy and the writing of rules is intertwined with computer science. The technology has not settled yet and its development costs money. Those who fund the development of the technology make the design choices. This gives a significant advantage to well-funded regulated entities enabling them to influence the process in a way which is hard to perceive. It is difficult to determine from the outside if particular functionalities reflect business reasons of the entities who provided the funding or are requirements rooted in the underlying computer science. The regulator therefore needs to be particularly careful to remain objective when integrating regulatory technology.

Fair, accessible and open procedures also matter for enforcement. The requirements of due process need to inform functionalities that automate enforcement. This applies to regulatory technology reviewing individual data points as well as regulatory technology that selects and analyses data autonomously. If the analytical function of the technology is connected to an automated enforcement mechanism such as a ‘smart contract’ regulated entities need to be provided with procedures that enable them to set aside enforcement action.

4.3 Expertise

The third criterion against which regulation can be evaluated is expert judgement. It is possible to justify regulatory intervention on the basis that a decision maker possesses expert judgement. Expertise can be a basis on which the public can be expected to have trust in regulatory decisions. It can justify supplying the regulator with a broader range of discretion.Footnote 82

Regulatory technology can generate high quality analysis. Machine learning can identify fact patterns in data that human analysts would take much longer to identify. This could inspire significant levels of reliance on regulatory technology to supervise regulated entities. An argument could be made that the deeper and broader analysis that can be achieved through artificial intelligence amounts to expert judgment, which justifies removing discretion from human decision makers.

That would be a mistake. The technology is new and we do not yet fully understand all the possible implications. More generally, while the process of identifying risk that justifies regulatory intervention can be assisted by quantitative mechanisms, risk cannot be predicted with scientific certainty. Decisions about identifying risk and acting on such identification involve judgement and should be subject to accountability.Footnote 83

Moreover, problems of regulatory capture may arise also in relation to expertise. The FCA and the Bank of England have set up special units for regulatory technology.Footnote 84 These are intended to work closely with regulated entities. Regulators have governance mechanisms in place to ensure that those setting policy are removed from close interaction with regulated entities. But at the moment there is a knowledge gap. Those setting policy at senior levels do not necessarily have technological expertise enabling them to critically evaluate the information they are presented with. The regulator needs to be sure that its senior decision makers have access to expertise enabling them to exercise professional judgement from the perspective of its democratic mandate and the public interest.Footnote 85

4.4 Efficiency

The fourth criterion against which regulation can be assessed is efficiency. Efficiency can be determined by reference to the implementation of the legislative mandate. Another way of assessing efficiency would be by reference to the results delivered by the regulatory process. Either way efficiency often conflicts with social aims of regulation which are difficult to quantify and is therefore a contested criterion.Footnote 86

In relation to regulatory technology both the regulator and regulated entities are engaging in the process because they expect cost savings.Footnote 87 At present there have only been experiments which have shown that a type of software that writes programmes that automate the reporting of one data point works. Nevertheless, the use of regulatory technology is in the FCA’s business plan.Footnote 88

Time will tell if the savings delivered by regulatory technology outperform the cost involved in setting up and overseeing the mechanism that will evolve going forward. It is, for example, not yet clear how easy it will be to ‘map’ machine readable code or new regulatory software tools onto existing IT systems.Footnote 89 It is possible that regulated entities will need to spend significant amounts of money to make their legacy systems compatible with any new mechanism, with some in the industry predicting that such costs may be prohibitively expensive.Footnote 90 This problem is amplified by the fact that many regulated entities store relevant data in multiple legacy systems and different formats.Footnote 91 An additional problem arises because investments in new technology can be more challenging for smaller than for larger market participants.Footnote 92

4.5 Precision v. Flexibility

To determine efficiency the cost and the output of regulatory regimes are expressed in monetary terms and compared. Connected to this is the question of which type of rules best serves the respective aims of regulation. For regulatory technology, this aspect of designing regulation deserves a heading of its own. There is a choice between granular rules and general principles or standards. Granular rules are more certain, but inflexible.Footnote 93 This can strangle competition and stunt enterprise and growth.Footnote 94 Granular rules can also encourage box ticking.Footnote 95 Principles and standards are flexible but come at the price of ambiguity which creates uncertainty.

A hallmark of good regulation is the extent to which a regulator focuses on outcomes rather than on technical compliance.Footnote 96 Following the financial crisis trust in the ability of regulated entities to align their business interests with regulatory aims has diminished. Regulators have become more interventionist. This, however, has not harmed the firm belief that ‘conduct should be in accordance with the principles and purposes of the rules, not the letter’.Footnote 97 A good quality regulatory regime achieves more than technical compliance.

We have seen that regulatory technology has been said to be capable of delivering more precise and certain rules.Footnote 98 The capability of software to operate to high levels of precision is, however, also a limitation. Software is at present not as capable as natural language to operate flexibly. This may be a temporary issue that will be solved by computer scientists in the future.

For the time being however, policy makers need to determine for which context high levels of precision are desirable. For the reporting of individual data points the current framework already operates at a high level of granularity. Creating software that automates this process through technology does not change this.

It is nevertheless possible for unintended consequences to arise.Footnote 99 For example, at present regulators receive transactions reports with a delay in time. If they identify problems regulated entities are able to make the point that these have been resolved. When the regulator receives real-time transactional information its systems can respond in real-time. There is a risk that this encourages regulated entities to orient themselves towards impressing the regulator in real-time. They could become too focused on real-time reporting, orient their business model accordingly and inadvertently overlook longer-term risks.

This could have the same unwelcome effect that was generated by the requirements for quarterly reports for listed companies. In the post-mortem following the financial crisis it emerged that these reporting requirements caused companies to focus on generating positive short-term metrics and steered them away from making adequate provisions for long-term risks.Footnote 100

For assessments that are currently carried out using general principles or standards the use of regulatory software would change the regulatory design to a more granular level. This may be desirable. The effect of increased levels of precision should nevertheless be the result of a deliberate decision in the respective context rather than an unintended effect using new digital technology.

5 Strategies for Regulation

In Sect. 4 we saw that delivering and claiming quality presents special challenges to integrating regulatory technology into regulation. Section 5 takes that broad argument to a more particular level by analysing how those challenges vary according to the regulatory strategy being put into effect. There are a variety of regulatory strategies available for financial regulation.Footnote 101 The choice lies somewhere between control and freedom. Governments can either impose rules backed by sanctions or leave businesses to their own devices.Footnote 102 Three principled options will be examined here: command regulation, a self-regulatory approach and meta-regulation. We will also briefly look at an activity-based regulatory model. We will see that different advantages and problems arise when technology is integrated into a command as compared to a meta-regulatory or self-regulatory approach. It will also be shown that technology is not neutral. Its availability does not supply regulated entities with greater ability to make their business decisions align with the public interest.

5.1 Command Regulation

The essence of a command regulatory strategy is in its control of the achievement of certain outcomes by imposing sanctions where outcomes are not met. The government is in charge. It writes rules and designs sanctions through primary or secondary legislation and a regulatory body enforces them.Footnote 103 The regime that was put in place after the financial crisis can in large parts be characterised as a command regime.

A command approach could integrate regulatory technology. The government could control the development, its maintenance and updates of the technology.Footnote 104 It could issue software requiring regulated entities to run that software on their systems.

This would address the problem that the coding involves policy choices. Making these choices would remain with the government or the regulator.

Command regulation is generally associated with a preference for granular rules.Footnote 105 This fits with the characteristics that are ascribed to digital technology which generally struggles to integrate ambiguous terms.Footnote 106 Using a more precise tool the regulator would be able to create a more certain framework. There is, however, a risk that a regulator with a preference for granularity overuses an instrument that can only operate to high levels of precision and produces a framework that suffers from inflexibility. This could make it difficult for different business models to thrive and creates a source for systemic risk.Footnote 107

Command regulation is said to be expensive for both the government and for regulated entities. The government needs to both write appropriate rules and develop an enforcement mechanism.Footnote 108 In our context an additional cost factor is that a regulator who designs technology at an operational level would also have to assume a significant part of the technological risk.Footnote 109

If the regulator developed regulatory software the regulated entities would save the money they currently spend to design compliance solutions. They would, however, have to absorb the cost of connecting their existing IT systems with that software.

It has already been mentioned that regulatory technology is particularly susceptible to capture. The line between policy decisions and computer science requirements is not a bright one and, in any event, not visible for non-experts. The regulators’ technology teams are necessarily closely involved with regulated entities. Senior decision makers are further removed but suffer from a knowledge gap. Under a command approach the risk of capture is particularly acute. This is because the regulator needs to rely on information provided by the industry to write rules. In giving information to the regulator, entities can exercise a ‘degree of leverage over regulatory procedures’, which can, over time, produce capture.Footnote 110 If the regulator decides to integrate regulatory technology into a command framework robust governance mechanisms would have to be put in place to avoid the problem of capture.

From the perspective of a potentially closed market of technology providers there are advantages associated with keeping its development close to the government which has significant bargaining power allowing it to exercise control over its content. This, however, comes at a price. The regulator needs to have sufficient resources to be able to have the expertise required to adequately oversee the operational aspects of the process.

5.2 Self-Regulatory Approaches

This approach to regulation relies on market mechanisms. The idea is that regulated entities have a business incentive to abide by certain standards.Footnote 111 They want to impress their customers. These are sensitive to poor practices and this will ensure that appropriate standards are developed and observed.

Self-regulatory approaches normally have some form of a statutory backing.Footnote 112 Self-regulation with a statutory mandate was the approach adopted in the UK between 1986 and 1998.Footnote 113 It has since been discredited culminating in a statement by Joseph Stiglitz who referred to the idea that markets can self-regulate as an oxymoron.Footnote 114 Following the financial crisis, self-regulation has been described as a model ‘in retreat’.Footnote 115

An analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of self-regulatory approaches is nevertheless useful here. As the memory of the financial crisis fades the financial services industry is likely to assert its influence over the policymaking process pushing for de-regulation.Footnote 116 The current interest in regulatory technology is motivated by the perceived burden created by post-crises regulation and could be characterised as move in that direction.

Self-regulatory approaches are likely to resurface particularly for regulatory technology. An argument could be made that the availability of new technological tools makes it possible for the regulator to step back and leave it to the market, now equipped with regulatory technology, to create appropriate frameworks.

Under a self-regulatory approach the regulator would forget about regulatory reporting and would not get involved in participating in a distributed ledger. It could appoint an industry association and instruct it to develop risk-managing technology. Alternatively, it could require individual firms to adopt appropriate regulatory technology. For both approaches the government would endorse the technology at some high level but would not get involved in writing rules either in legal or machine-readable English or in computer code. It would stand back and let individual firms or their associations develop appropriate practices.

Self-regulatory forms of regulation have been credited with advantages. The government does not pay for the design of the standards or for their enforcement.Footnote 117 Specialised knowledge can be built into regulation.Footnote 118 Rules can be tailored to individual companies or sectors to higher degree than under a meta-regulatory model. This can facilitate regulatory innovation.Footnote 119 Further, it has been suggested that regulated entities are more likely to comply with rules they have created themselves and that such rules would be more targeted making it easier to enforce them.Footnote 120 Enforcement can moreover be delegated to specialist bodies which are able to impose industry appropriate, and thus more effective, sanctions.Footnote 121

There are also disadvantages associated with a self-regulatory approach. There are concerns about democratic legitimacy and accountability when rules are made by self-regulatory bodies that are not bound by legislation or accountable to the government.Footnote 122 The same problem arises in relation to enforcement. If a self-regulatory body is more accountable to its members than general public, this is likely to prompt trust issues.Footnote 123 It may find it difficult to enforce regulation where it would negatively affect its members’ business or reputation.Footnote 124 Self-regulatory bodies can have a tendency to act anti-competitively by setting access requirements or prices that suit the interests of their members rather than the general public.Footnote 125 This may stifle competition.

Moreover, it would not be easy for industry associations to develop a common framework. Regulated entities can pool resources to fund technological development only in so far as they have overlapping interests. This makes it difficult for them to co-operate. For technology, finding common ground is particularly difficult not only because there are competing business interests but also because different entities have different legacy systems. Entities that have formed as a result of corporate restructuring sometimes operate more than one IT system because it has proven to be too difficult to connect them domestically.

There is also a concern that regulated entities are unable to find much common ground between their interests and the public interest. They will then focus on being seen to be compliant rather than on ensuring that they actually meet the standards. Self-regulatory systems are said to be susceptible to gaming because there is no independent regulator monitoring compliance.

The regulator could decide to use the availability of regulatory technology as an opportunity to review the interventionist approach that was adopted after the financial crises. It could take the view that the reforms have proven to be too expensive and limiting. It could modify its regulatory strategy. That is a matter for policy choice and weighing up the advantages and disadvantages of the various regulatory models.

The availability of new technological tools is, however, no reason to change gear. Technology does not change the fact that self-regulation relies on trusting regulated entities to adopt robust mechanisms. Both the advantages and the disadvantages of self-regulation apply for regulatory technology. The technology is not neutral. It serves those who develop it. It would be wrong to assume that any form of technology will allow us to have greater faith in the ability of regulated entities to align their business interest with the public interest.

If anything, technology adds a level of complexity that has to inform regulatory decision making. For a self-regulatory model and perhaps more so than any other approach, the problem arises that the market for technology providers of data analysis has its own business models and has the potential to become quite concentrated. Technology providers and their business model could steer the design of the technology further away from the public interest.

5.3 Meta-Regulation

Meta-regulation has been described as ‘the state’s oversight of self-regulatory arrangements’,Footnote 126 and also as ‘interactions between different regulatory actors or levels of regulation’.Footnote 127 It occupies a middle ground somewhere between command regulation with a high level of government involvement and self-regulation with a minimal amount of government involvement. The regulator delegates risk control to the regulated entities themselves, giving them primary responsibility for the risk management systems, while the regulator audits, monitors and incentivises the systems. The regulator steers, the regulated entities row.Footnote 128

The regulator would not design or maintain regulatory software itself but oversee and validate its production. The regulator could specify requirements leading to the creation of a distributed reporting ledger leaving the development and maintenance of the system to regulated entities or their providers. The regulator could issue a machine-readable version of the rules for reporting specific data points. It could also issue technical specifications setting out some common operational standards but would refrain from developing particular software applications.Footnote 129

In the future, the regulator could step back from specifying which data is to be submitted or analysed leaving it to autonomous algorithms to work out patterns and information that is relevant for measuring risk. It would nevertheless remain involved in writing specifications for and in validating software that is used for these purposes.Footnote 130

Keeping in mind that coding involves policy choices and that data generates a limited picture, the regulator would be able to set its level of involvement in a way that preserves democratic legitimacy and regulatory accountability. Moreover, procedural requirements could be prescribed such that the technology operates in a fair, accessible and open manner.

Meta-regulation has been credited with the ability to generate a positive compliance culture, ‘as firms are asked to think for themselves about the challenges of controlling’ particular risks.Footnote 131 For this benefit to materialise, however, firms must have both the ‘capacity for self-regulation’ and the ‘internal resolve to self-regulate’.Footnote 132 Like principled-based regulation, which assumes that regulated entities are able to abide by certain principles,Footnote 133 meta-regulation can fail when firms do not adopt appropriate rules or, for our context, appropriate technology because they are uninformed, ill-intentioned or give priority to business considerations.Footnote 134

Further, meta-regulation has been credited with low cost for the regulator.Footnote 135 From the perspective of the regulator, writing specifications and validating applications is cheaper than being involved in writing software applications. The regulator would have to invest to develop and preserve its ability to write appropriate specifications and approve the applications based on these, but it would not have to fund the full cost of developing regulatory software. These would be borne by regulated entities. By not involving itself at the operational level the regulator would also avoid responsibility for technological risk. These would have to be resolved between regulated entities and their service providers.

From the perspective of regulated entities the cost of complying with meta-regulation is also thought to be lower than the cost of complying with command regulation.Footnote 136 By automating certain processes regulatory software could indeed make compliance cheaper for regulated entities. The initial cost of developing new digital technology that integrates into existing systems could, however, be significant.

A meta-regulation model can facilitate the emergence of firm-specific rules.Footnote 137 Involving the regulator at a higher level of abstraction would make it possible for different firms to develop different types of regulatory software which fit both the regulatory specifications and their respective business models. This might help to alleviate concerns about systemic risk.

Finally like for command and for self-regulation it remains to be seen how a meta-regulatory model will cope with the introduction of technology providers into the regulatory space. The regulator will have to develop an understanding of the business model of the technology providers and determine its level of oversight accordingly with a view to preserving the public interest. To be able to act as an effective monitor of software developed by an oligopolistic market will require a robust amount of expertise.

5.4 Activity-Based Model of Regulation

The standard classification model for regulatory strategies analyses regulation depending on the level of state intervention. In contrast to this Professor Heyvaert is proposing a classification model based on regulatory activity rather than state intervention.Footnote 138 Regulation operates at different levels that require different approaches. These are: the identification of high level policy goals, the normalisation of these goals for example through the creation of rules and standards, engagement activity for example through communication, learning activity through feedback loops and response-based activity ensuring compliance.Footnote 139 This perspective allows the analysis of the interventions independently of how much the state involves itself. From this perspective it is important to ensure that any fascination with technological innovation does not get in the way of a fundamental understanding of the big picture and limits the ability of regulatory actors to set high level goals.

5.5 Conclusions

Regulatory technology is no silver bullet. It does not allow the regulator to have more faith in the ability of a regulated entity to align their profit-making goals with the public interest. The choice of regulatory strategy should not be affected by the availability of regulatory technology. For all three approaches discussed in this section, the role of the providers of regulatory technology needs to be addressed. This is most easily done for a command approach and quite difficult in a self-regulatory model. If regulatory technology is integrated into a command approach, however, the problem could arise that requirements become increasing granular and inflexible which would stifle innovation and growth and could also increase levels of systemic risk. It would seem that a meta-regulatory model that preserves the regulator’s democratic mandate and accountability as well as procedural fairness would be a suitable way to integrate new digital technologies into regulation. Either way, the regulator will need robust technological expertise to make the technology work in the public interest.

6 Conclusions

The article examined the use of new digital technologies for regulatory purposes. The analysis covered distributed ledger technology and two aspects of artificial intelligence: natural language processing and machine learning. To focus the discussion two potential use cases were examined in more depth: the use of distributed ledger technology and machine learning software to automate regulatory reporting requirements and the use of machine learning as a risk management tool.

At an operational level these technologies could make compliance easier. They could make regulation more precise and supply the regulator with more accurate and real time information. The regulator could be enabled to supervise the whole population of regulated entities benefitting from granular evidence supplied in real time. The technologies could also assist the regulator and regulated entities in analysing this evidence allowing them to identify risk as it emerges.

A natural starting point to evaluate regulatory technology is to review it against analytical criteria that have evolved in the mainstream regulatory discourse. A number of points emerge from this analysis.

Regulatory technology integrates policy choice with coding software. Considerations of democratic legitimacy and accountability therefore limit the extent to which the regulator can leave the translation of regulation into software to third party technology providers.

The regulator needs to avoid the temptation of over-estimating the scope of the evidence and analysis generated by new digital technologies. Data is a good and an objective source of information. Algorithms find patterns that humans overlook. But data is never complete and predicting risk is not a scientific endeavor. Regulatory legitimacy would be seriously undermined by an approach that fails to ensure that the scope of the evidence underlying data-driven analysis is robustly communicated to the decision makers who rely on regulatory technology.

Functionalities that automate enforcement need to incorporate requirements of due process.

There is significant risk of regulatory capture. Policy decisions are connecting with coding decisions. The line between policy choice and computer science requirements is not a bright one and not visible to non-experts. The technology teams of the regulators are close to regulated entities and this may compromise their professional scepticism. Senior decision makers suffer from a knowledge gap. The regulator needs to invest in expertise.

Unintended consequences can emerge. Real-time reporting could lead to short term thinking. Regulatory technology could cause regulation to become more granular, leading to inflexibility, technical rather than functional compliance and increasing standardisation. This could generate systemic risk.

The providers of technology will play a significant role. They are for the time being small start-up enterprises. But the more the regulators rely on new digital technology the more attractive the market for regulatory technology will become for the handful of existing providers of data analysis. Their involvement in writing software that monitors risk may become similar to the role performed by credit rating agencies or auditors. This will bring with it the same difficult task of ensuring that the monitoring device that emerges serves the public interest.

Regulatory technology is said to help deliver better quality compliance and regulation for less money. Time will tell if savings arising from automating processes and mechanising analysis will outperform the cost involved in developing, connecting and maintaining the technology on the existing legacy systems.

In terms of identifying a suitable regulatory strategy the regulator has a number of options available. It could develop regulatory software exercising full control of its maintenance and update at an operational level. It could step back and appoint an industry association or leave regulated entities to create software that manages risk. The regulator would endorse this self-regulatory mechanism at a high level of abstraction but would not proactively involve itself in its development. It could adopt a meta-regulatory approach overseeing the development and maintenance of regulatory software by private providers without having full control at an operational level.

All types of regulation have advantages and disadvantages. In most regulatory contexts, a combination of various strategies of regulation are employed.Footnote 140 The characteristics of regulatory technology will play out in different ways for each of these strategies and need to be accommodated accordingly. But technology is not neutral. It is programmed to reflect the preferences of those who oversee its development. While regulatory technology can change the game, it will not be able to change the fact that business interests do not always align with the interests that the regulator has been set up to serve. It would be wrong to assume that regulatory technology is a silver bullet that will make it easier for regulated entities to align their interests with regulatory standards.

Notes

‘Hype springs eternal; The blockchain in finance’, The Economist (London), 19 March 2016, p 73; see also Yeung (2019), p 207.

Two recent covers of The Economist focus on artificial intelligence: ‘The Next Frontier—When Thoughts Control Machines’, 4 January 2018 and ‘Doctor You—A Revolution in Health Care is Coming’, 3 February 2018. The issue of 14 February 2018 contains seven articles that use the term ‘artificial intelligence’: pp 12, 30, 60, 68, 69, 78 and 79.

Financial Conduct Authority (2015).

Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, BEIS Digital, Data and Technology (2017).

There is an emerging literature on legal technology assisting or replacing lawyers and other legal decision makers. See, for example, Pasquale (2019).

Financial Conduct Authority (2018a), p 27.

Zetzsche et al. (2017), p 34.

Financial Conduct Authority (2018h).

Financial Conduct Authority (2018f).

Micheler and von der Heyde (2016), p 631.

Paech (2017), p 1073.

For more information see https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/research/fintech/proof-of-concept (accessed 6 June 2019).

Micheler and von der Heyde (2016); The Australian Stock Exchange has announced that it will operate its clearing and settlement system using distributed ledger technology from 2020, see Eyers (2018); see also https://www.asx.com.au/services/chess-replacement.htm.

Scherer (2016), pp 361 and 364.

Firth-Butterfield et al. (2017).

Yeung (2018).

Sanjiv Ranjan et al. (2017).

For an excellent explanation of this type of technology see https://digital-legislation.net (accessed 11 June 2019); see also https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/research/fintech/proof-of-concept (accessed 11 June 2019); Butler (2017), pp 6–9.

Financial Conduct Authority (2018b), paras. 3.2–3.4.

Financial Conduct Authority (2018g).

See https://gabriel.fca.org.uk/portal_authentication_service/appmanager/merportal/desktop (accessed 6 June 2019).

Financial Conduct Authority (2018b), paras. 3.2–3.5.

Institute of International Finance (2016).

Institute of International Finance (2016).

Financial Conduct Authority (2018g).

Financial Conduct Authority (2018g).

Financial Conduct Authority (2019).

Financial Conduct Authority (2018b), para. 3.3.

Arner et al. (2017), p 375.

Financial Conduct Authority (2018b), paras. 3.2–3.5.

Al Khalil et al. (2017).

There is also a possibility for using the availability of data to creating personalising regulation (for this see Helleringer 2019).

Morse (2018).

Arner et al. (2017), pp 382–383.

Arner et al. (2017), p 402.

For this see Helleringer (2019).

Lichtman et al. (2018), p 781.

Financial Conduct Authority (2018j).

Burt et al. (2017), p 5.

Yeung (2018).

The authors are grateful to Mark Staples for this point.

Robertson (2018).

See for example the list of speakers and sponsors at the London FinTech Week 2018 (https://www.fintechweek.com/home) or at the London FinTech Summit 2018 (https://ifgs.innovatefinance.com/agenda-2018/).

Scherer (2016), pp 374–375.

Mennicken and Power (2013), p 308.

Black (2015), p 218.

Baldwin et al. (2012), p 143.

Baldwin et al. (2012), p 143.

Ranchordás (2019), p 81.

See also Pasquale (2019).

Baldwin et al. (2012), p 29.

Armour et al. (2016), pp 558–560.

Baldwin et al. (2012), pp 29–30.

Black (2005), p 512.

See above.

See also Chiu (2017), p 763.

Baldwin et al. (2012), p 31.

Financial Conduct Authority (2018a), p 27.

Financial Conduct Authority (2018j).

An example of how difficult it can be to adopt new information technology recently occurred in the UK. Following a restructuring TSB Bank moved customer accounts to the IT system operated by its new owners, Sabadell. The anticipation was that this would be a seamless process. The migration, however, turned out to be more complex than expected. It resulted in customers being unable to access their own accounts over a period of several days with problems persisting over weeks. Some 400 customers gained access to accounts that did not belong to them. Branches were unable to operate. The telephone system collapsed (Andrew Bailey, CEO of the FCA, letter dated 30 May 2018 responding to Nicky Morgan, MP, https://www.parliament.uk/documents/commons-committees/treasury/Correspondence/2017-19/fca-to-chair-tsb-300518.pdf, accessed 6 June 2019).

Financial Conduct Authority (2018k), para. 2.8.

Diver (1983), p 65.

Diver (1983), p 65.

Better Regulation Task Force (2003), p 16.

Black (2015), p 245.

Subsection 3.3.3, above.

Ibid; Burt et al. (2017), p 5—see reference to the risk of ‘incorrect disambiguation’.

Kay (2012), paras. 10.20–10.21 and Interim Report (2012), paras. 4.14–4.15.

Coglianese and Mendelson (2010), p 146.

Baldwin et al. (2012), p 106.

Enriques (2017), p 5.

Baldwin et al. (2012), pp 108–109.

Subsection 3.3.3, above.

Colaert (2015), para. 51.

Baldwin et al. (2012), p 108.

Armour et al. (2016), p 546.

Black (2015), pp 219–221.

Ferran (2015), p 110.

Ferran (2015), p 111.

Armour et al. (2016), p 546.

Hutter (2006), p 215.

Coglianese et al. (2010), p 147.

Baldwin et al. (2012), p 147.

Financial Conduct Authority (2016), p 12.

An example of such an approach of integrating technology into regulation can be found in the US Code of Federal Regulations (https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/CFR-2017-title17-vol1/CFR-2017-title17-vol1-sec23-155/content-detail.html, accessed 1 October 2018). Title 17 part 23 rule 155 concerns the requirements for the calculation of margin requirements for swaps. Rather than receiving reports of individual data points the SEC sets requirements for and approves the methodology to be used by regulated entities.

Baldwin et al. (2012), p 148.

Baldwin et al. (2012), p 149.

Baldwin et al. (2012), p 147.

Baldwin et al. (2012), p 148.

Baldwin et al. (2012), p 147.

Heyvaert (2018).

Heyvaert (2018).

Baldwin et al. (2012), p 132.

References

Ajunwa I, Crawford K, Schultz J (2017) Limitless worker surveillance. Cal L Rev 105:735–776

Al Khalil F, Ceci M, O’Brien L, Butler T (2017) A solution for the problems of translation and transparency in smart contracts. http://www.grctc.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/GRCTC-Smart-Contracts-White-Paper-2017.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2019

Armour J, Awrey D, Davies P, Enriques L, Gordon JN, Mayer C, Payne J (2016) Principles of financial regulation. OUP, Oxford

Arner DW, Barberis J, Buckley RP (2016) The emergence of Regtech 2.0: from know your customer to know your data. J Financ Transform 44:79–99

Arner DW, Barberis J, Buckley RP (2017) FinTech, RegTech and the reconceptualization of financial regulation. Northwest J Int Law Bus 37:371–413

Ayers I, Braithwaite J (1991) Responsive regulation. OUP, Oxford

Baldwin R, Cave M, Lodge M (2012) Understanding regulation: theory, strategy and practice, 2nd edn. OUP, Oxford

Better Regulation Task Force (2003) Imaginative thinking for better regulation. Cabinet Office http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100812083626/http://archive.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/brc/upload/assets/www.brc.gov.uk/imaginativeregulation.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2019

Black J (1998) Talking about regulation. Public Law 77–105

Black J (2001) Decentring regulation: understanding the role of regulation and self-regulation in a ‘post-regulatory’ world. Curr Leg Probl 54:103–146

Black, J (2005) The emergence of risk-based regulation and the new public risk management in the United Kingdom. Public Law 512–548

Black J (2008) Constructing and contesting legitimacy and accountability in polycentric regulatory regimes. Regul Gov 2(2):137–164

Black J (2015) Regulatory styles and supervisory strategies. In: Moloney N, Ferran E, Payne J (eds) The Oxford handbook of financial regulation. OUP, Oxford, pp 217–253

Burt A, Aron-Dine J, Kim E, Martinz C, Wang X (2017) 2017 Model driven and machine executable regulations and tech sprint: success criteria and recommendations. https://www.immuta.com/download/recommendations-for-the-fca-and-boes-2017-model-driven-and-machine-executable-regulations-tech-sprint/. Accessed 6 June 2019

Butler T (2017) Standard-based semantic technologies for smart regulation. White Paper, Governance, Risk & Compliance Technology Centre, University of Cork. http://www.grctc.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/GRCTC-Standards-based-Semantic-Technologies-for-Smart-Regulation-White-Paper-2017.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2019

Chiu I (2017) A rational regulatory strategy for governing financial innovation. Eur J Risk Regul 8:743–765

Coglianese C, Mendelson E (2010) Meta-regulation and self-regulation. In: Baldwin R, Cave M, Lodge M (eds) The Oxford handbook on regulation. OUP, Oxford

Colaert V (2015) RegTech as a response to regulatory expansion in the financial sector. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2677116. Accessed 6 June 2019

Crawford K, Schultz J (2014) Big data and due process: towards a framework to redress predictive privacy harms. Boston Coll Law Rev 55:93–128

Danielson J (2017) Artificial intelligence and the stability of financial markets. VOXEU, 15 November 2017. https://voxeu.org/article/artificial-intelligence-and-stability-markets. Accessed 6 June 2019

Deakin S (2015) The evolution of theory and method in law and finance. In: Moloney N, Ferran E, Payne J (eds) The Oxford handbook of financial regulation. OUP, Oxford, pp 13–40

Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, BEIS Digital, Data and Technology (2017) Strategy 2017–2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/687480/BEIS_DDaT_Strategy.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2019

Diver CS (1983) The optimal precision of administrative rules. Yale Law J 93(1):65–109

Domberger S, Sherr A (1989) The impact of competition on pricing and quality of legal services. Int Rev Law Econ 9:41–56

Enriques L (2017) Financial supervisors and Regtech: four roles and four challenges. Revue Trimestrielle de Droit Financier 53. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3087292. Accessed 6 June 2019

Evgoulas E (2015) Regulating financial innovation. In: Moloney N, Ferran E, Payne J (eds) The Oxford handbook of financial regulation. OUP, Oxford, pp 659–692

Eyers J (2018) ASX blockchain to go live at the end of 2020. Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/technology/asx-blockchain-to-go-live-at-end-of-2020-20180427-h0zcgx. Accessed 6 June 2019

Ferran E (2015) Institutional design: the choices for national systems. In: Moloney N, Ferran E, Payne J (eds) The Oxford handbook of financial regulation. OUP, Oxford, pp 97–128

Financial Conduct Authority (2015) Call for input: supporting the development and adoption of RegTech. https://www.fca.org.uk/news/news-stories/call-input-supporting-development-and-adoption-regtech. Accessed 1 Oct 2018

Financial Conduct Authority (2016) FCA feedback statement FS 16/4 to call for input on supporting the development and adopters of RegTech. https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/feedback/fs-16-04.pdf. Accessed 1 Oct 2018

Financial Conduct Authority (2018a) Business plan 2018/19, 27. https://www.fca.org.uk/publications/corporate-documents/our-business-plan-2018-19. Accessed 6 June 2019

Financial Conduct Authority (2018b) Call for input: using technology to achieve smarter regulatory reporting. https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/call-for-input/call-for-input-smarter-regulatory-reporting.pdf. Accessed 1 Oct 2018

Financial Conduct Authority (2018c) Discussion paper on distributed ledger technology (DP17/3, April 2017). https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/discussion/dp17-03.pdf. Accessed 1 Oct 2018

Financial Conduct Authority (2018d) Distributed ledger technology: feedback statement on discussion paper 17/03 (FS17/4, December 2017). https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/feedback/fs17-04.pdf> Accessed 1 Oct 2018

Financial Conduct Authority (2018e) FCA Innovate. https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/fca-innovate> Accessed 1 Oct 2018

Financial Conduct Authority (2018f) FinTech. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/research/fintech. Accessed 1 Oct 2018