Abstract

The global financial crisis proved that banks are not the sole source of systemic risk to the financial system and the wider economy. Indeed, systemic risk emanating from non-bank financial institutions proved to be a key vulnerability of the financial system. Such risks occurred, above all, when leveraged non-bank financial institutions performed bank-like activities such as maturity and/or liquidity transformation. However, the increasingly blurred distinction between markets, financial institutions, services and products is not matched in the European Union by an integrated regulatory and supervisory approach. Instead, regulation was and remains largely organised along sectoral lines, with an emphasis on the banking sector. As the global financial crisis shows, this creates a risk of gaps in the coverage of regulation and supervision, leading to inconsistent regulatory treatment of equivalent products and/or services. This in turn causes an unlevel playing field and increases the potential for regulatory arbitrage. In consequence, risky activities migrate to less regulated or unregulated parts of the financial system, leading to a largely unchecked build-up of systemic risk. Drawing inspiration from the reforms in the United States, we propose that the EU’s system of financial regulation be complemented by a robust body charged with identifying and monitoring non-bank financial institutions that are systemically important. This EU authority should have the discretion to designate a non-bank financial institution as a Non-Bank Systemically Important Financial Institution (non-bank SIFI). A logical choice would be to confer such powers on the European Systemic Risk Board. Designated non-bank SIFIs should be placed under direct prudential supervision by an EU body. This EU supervisor would have to establish, on an individual or categorical basis, appropriate enhanced prudential requirements tailored to the nature, risks and activities of the relevant non-bank SIFI. Additionally, a single European resolution regime should be in place to ensure that non-bank SIFIs can fail without destabilising the financial system. This would avoid a possible ‘Too-Big-To-Fail’ status, remove implicit government guarantees and subject the institution to market discipline. Our proposal aims to ensure that non-bank SIFIs are brought within a regulatory perimeter and supervisory scrutiny consistent with the risk they pose to financial stability. Such a regime would (i) help to eliminate (national) supervisory and regulatory gaps, (ii) reduce regulatory arbitrage activities, and (iii) contribute to the stability of the financial system and a level playing field.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In 2001 Roger Lowenstein noted that the Fed’s initiative to organise a private bailout of hedge fund management firm Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) was not done out of sympathy for LTCM nor to prevent losses to exposed financial institutions.Footnote 1 Instead, the driving concern was ‘the broader notion of “systemic risk”; if Long-Term failed, and if its creditors forced a hasty and disorderly liquidation, [the Fed] feared that it would harm the entire financial system, not just some of its big participants’.Footnote 2 Still, with the last financial meltdown dating back to the 1930s, it was unclear whether ‘systemic risk’ presented a real threat. Lowenstein noted that it was a ‘parlor topic, not something the bankers wanted to spend $250 million on’.Footnote 3

Any residual doubt about the threat posed by systemic risk was dispelled 10 years later when the onset of the Global Financial Crisis necessitated large-scale government intervention to prevent the markets from collapsing.

The Global Financial Crisis painfully demonstrated deficiencies in the regulation, supervision and resolution of financial institutions. Not only in the traditional banking sector but also in other parts of the financial system. Indeed, systemic risk manifested itself to a large degree outside the traditional banking sector, especially in the lightly regulated shadow banking sector. The latter refers, quite ominously, to market-based credit intermediation outside the banking sector. Due to a lack of comprehensive regulation and supervision, banks increasingly shifted activities to the shadow banking sector in order to avoid tax, disclosure and capital requirements.Footnote 4 Such behaviour, which is designed to evade more stringent regulation and supervision or to evade regulation and supervision altogether, is known as regulatory arbitrage. The exploitation of regulatory gaps, however, creates risks to financial stability and puts paid to the notion of a level playing field.

To strengthen financial stability, we propose that non-bank financial institutions which are systemically relevant should be subjected to European prudential regulation and to a European supervisor and a European resolution authority.Footnote 5

Our proposals exclude banks as they are already subject to stricter prudential regulation under the Capital Requirements Directives (CRD IV) and Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) and, within the Member States participating in the European Banking Union (EBU), are subject to the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM). Within the SSM, significant banks are directly supervised by the ECB and resolved by the Single Resolution Board (SRB).Footnote 6

In accordance with the approach of the Financial Stability BoardFootnote 7 and the US Dodd-Frank reforms,Footnote 8 we advocate that the EU’s sectoral approach to financial regulation, supervision and resolution be complemented by a more risk-based identification, regulation, supervision and resolution of non-bank systemically important financial institutions. Any non-bank financial institutionFootnote 9 which could pose a threat to financial stability—referred to as non-bank systemically important financial institutions (non-bank SIFIs)—should therefore be subject to commensurate supervision, regulation and resolution, regardless of the legal categorisation of the non-bank financial institution.Footnote 10 This would entail partial reform and extension of supervision, regulation and resolution of financial institutions in the EU, which is presently organised largely along sectoral lines, and a move towards a more pan-sectoral regime for non-bank SIFIs. A cross-sectoral supervisory and resolution regime for non-bank SIFIs would correspond with the increasingly blurred distinction between markets, financial institutions and products.Footnote 11 It would also help to reduce regulatory arbitrage activities and gaps in coverage, as it would ensure that the risks posed by a non-bank SIFI are subject to commensurate regulation, regardless of the legal form of the entity. In order to properly identify non-bank SIFIs, robust monitoring of the entire European financial sector is necessary.

The proposed regime is in line with financial reform proposals issued by the Financial Stability Board (FSB), which call for a level of supervision proportionate to the potential destabilisation risk that a financial firm poses to the financial system.Footnote 12 Additionally, the FSB requires an effective resolution regime for all financial institutions which could be systemically significant or critical if they fail.Footnote 13

For the development of such a regime we draw on the experiences in the US. There, non-bank financial companies can already be designated as systemically important. Such designation puts them under federal supervision and, reflecting their importance to the financial system, makes them subject to specific prudential and living will requirements. Additionally, non-bank financial institutions posing a systemic risk may be subjected to a specialised resolution regime.

This article seeks to contribute to the discussion on the development within the European Union of a regulatory regime which adequately addresses and mitigates the risk to financial stability posed by non-bank SIFIs. Section 2 therefore highlights the relevance of the problem by reiterating lessons learned from the Global Financial Crisis, especially in respect of the systemic risk posed by non-bank financial institutions. Section 3 examines recommendations made by international bodies, most notably the Financial Stability Board (FSB), in response to the Global Financial Crisis, to increase regulation, supervision and resolution in the financial sector. Section 4 draws inspiration from the US regime, which is of special interest as it already provides for the designation and consequential supervision and resolution of non-bank SIFIs. Section 5 considers the existing body of European financial regulation. We assess what has already been accomplished since the Global Financial Crisis and provide context to our proposed regime of non-bank SIFI supervision and resolution. Section 6 makes suggestions and explores legal possibilities for enhancing the existing body of European financial regulation by including designation, supervision and resolution of non-bank SIFIs at the European level. Section 7 contains our concluding remarks.

2 Systemic Risk

The Global Financial Crisis highlighted a number of structural weaknesses in the worldwide financial system and economies. One of the most important lessons was the, generally unforeseen, possibility of systemic risk originating from non-bank financial institutions.

Systemic risk is the risk that a national, regional or the global, financial system will break down.Footnote 14 Systemic risks manifest themselves where a localised shock—such as the failure of a financial institution—has repercussions that adversely affect the broader economy.Footnote 15 It thus poses a threat to financial stability.Footnote 16 Systemic risk can manifest itself in many different forms and within a range of financial institutions. As noted by Anabtawi and Schwarcz, systemic risks do not distinguish between financial market participants.Footnote 17 Systemic risk should therefore be regarded as an elusive concept, not confined to certain institutions, markets or products.Footnote 18 Accordingly, financial regulation should have an equally flexible and open scope.

Despite the regulatory focus, it turned out that systemic risk was not confined to the (retail) banking sector. Non-bank financial institutions such as Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM), American International Group (AIG) and Reserve Primary proved equally capable of creating systemic risk. This realisation is reflected in the European Systemic Risk Board Regulation, which acknowledges that all types of financial intermediaries, markets and infrastructure may potentially be systemically important to some degree.Footnote 19 Additionally, both the legislative proposal of the European Commission (Commission) on a framework for the recovery and resolution of central counterparties (CCPs)Footnote 20 and its proposal for the creation of a new supervisory mechanism for CCPs aim to regulate and supervise the systemic risk posed by CCPs.Footnote 21 This illustrates our premise that non-bank financial institutions are equally capable of posing systemic risks.Footnote 22 Asset management activities are another example of a potential source of non-bank systemic risk which has recently attracted attention.Footnote 23

The Commission’s proposal for the establishment of a Capital Markets Union (CMU) is also of interest as the envisaged growth of non-bank credit intermediation makes overarching checks on systemic risks even more pressing.Footnote 24 Designed to increase the supply of alternative sources of financing—thereby reducing dependence on funding through the banking sector—the CMU proposal looks to increase the role of non-bank financial intermediaries.Footnote 25 Such diversification of funding improves the allocation of capital and diversification of risk and thereby strengthens the European financial system. At the same time, as recognised by the ‘Five Presidents’ Report’, closer integration of capital markets and gradual removal of remaining national barriers necessitates an expansion and strengthening of the available tools to manage financial players’ systemic risks prudently (macro-prudential toolkit) and to strengthen the supervisory framework to ensure the solidity of all financial actors.Footnote 26 This should, according to the report, ultimately lead to a single European capital markets supervisor.Footnote 27

This shows that systemic risk can occur in different sectors, or indeed across different sectors, and have a variety of distinct characteristics. Therefore it might be difficult to identify such risks. It is therefore of great importance for jurisdictions to have a broad monitoring system in place, capable of identifying systemic risk throughout the entire financial sector.

2.1 Deregulation and Growth of the Financial Sector

As this article aims to contribute to the discussion on how to alleviate systemic risk, specifically in regard to non-bank financial institutions, a short consideration of the role of such entities in the manifestation of systemic risk, especially during the Global Financial Crisis, is in order.

By the mid-1990s the financial sectors in the EU and US were thriving. Technological advances, for instance in information services, led to economy-of-scale benefits.Footnote 28 Additionally, the perception that some of the largest financial institutions were Too-Big-To-Fail provided them with implicit guarantees, thereby generating additional confidence and growth.Footnote 29

At the same time, financial institutions, notably banks, successfully advocated deregulation and the removal of obstacles to growth and competition.Footnote 30 In 1994 this led the US to allow bank holding companies to acquire bank subsidiaries in all states.Footnote 31 In 1999 this was followed by the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act which repealed the restriction on affiliations between banks and securities firms imposed by the Glass–Steagall Act. As a consequence, banks were allowed to underwrite and sell securities and insurance products. Conversely, it allowed securities firms and investment banks to take deposits. Such developments paved the way for large-scale consolidation and growth within and across the banking, securities and insurance sector.Footnote 32 Boosted by progress in the creation of an internal market—specifically through the abolition of obstacles to the free flow of goods, persons, services and capital and the creation of the euro in 1999—a similar trend of increased cross-border activities, consolidation, and growth of financial institutions was evident in the European Union.Footnote 33

The financial supervisory and regulatory regimes remained, however, highly fragmented both geographically and sectorally. In the US, competition between supervisors led to a race to the bottom and, in the absence of a robust consolidated supervisor, regulators failed to identify excessive risks and unsound practices in non-bank financial institutions.Footnote 34 Securities firms, for example, were allowed to attract FDIC-insured deposits without becoming subject to supervision by the Fed.Footnote 35 Likewise, in the EU, financial prudential regulation and supervision was focused on banks.Footnote 36 In consequence, regulators failed to identify the build-up of excessive risk in the financial markets and non-bank financial institutions.

2.2 The Rise of Shadow Banking

The limited perimeter of prudential regulation, the focus on bank supervision and the lack of prudential regulation in the shadow banking sector were informed by the belief that only the banking sector could pose systemic risk. Infamous bank runs clearly contributed to this belief. As shadow banking institutions do not attract insured deposits ‘[t]here was little concern of a bank run’ regarding such institutions.Footnote 37 The reasoning was that such an institution could be left to fail. Furthermore, in a worst-case scenario the government was not liable to refund the insured deposits. Investors who contracted with these firms were supposedly aware of the risks. Indeed, it was thought that an increase in market-based credit intermediation, supplementing the credit provision by banks, would diminish systemic risk.Footnote 38 This proved incorrect.

Financial institutions, eager to take advantage of regulatory gaps, increasingly moved financial intermediation outside the regulatory perimeter of the traditional banking sector.Footnote 39 There they could perform bank-like maturity and liquidity transformation combined with highly leveraged funding structures, while largely unchecked by prudential regulation and oversight. In so far as regulation was present—mostly through securities and insurance regulation—it predominantly focused on market efficiency, transparency, integrity, and consumer and investor protection.Footnote 40 Moreover, as these activities fell outside the regulatory perimeter of banks, regulators were poorly equipped to spot the systemic risks they presented.Footnote 41 The premise that systemic risk was limited to the banking sector led to gaps in regulation and supervision in the financial sector.Footnote 42 Indeed, banking regulation, such as the Basel capital frameworks, did not account for, and thus encouraged, the shifting of risks off the balance sheet.Footnote 43

While precise definitions of ‘shadow banking’ vary, we will adopt the Financial Stability Board’s definition, namely ‘the system of credit intermediation that involves entities and activities outside the regular banking system’.Footnote 44 The FSB propagates a ‘wide net’ approach to defining the shadow bank sector, focusing on ‘credit intermediation that takes place in an environment where prudential regulatory standards and supervisory oversight are either not applied or are applied to a materially lesser or different degree than is the case for regular banks engaged in similar activities’.Footnote 45 This includes inter alia money market funds, hedge funds, insurance companies, mutual funds, structured investment vehicles and pension funds.

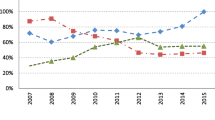

The shadow banking sector expanded rapidly in the years leading up to the crisis. Using a broad definition of non-bank credit intermediaries, the FSB gauged that the total assets in the global shadow banking sector had increased from $26 trillion in 2002 to $62 trillion in 2007.Footnote 46 More recently, the FSB assessed the total assets of non-bank financial intermediation of 20 jurisdictions and the euro area at $137 trillion, representing about 40% of total financial system assets.Footnote 47 In addition to its wide net approach, the FSB developed a narrow measurement methodology to narrow down shadow bank monitoring to those elements of non-bank credit intermediation where important risks may exist or are most likely to emerge. According to this measure, shadow banking amounted to $34 trillion at the end of 2015 for 26 jurisdictions.Footnote 48 This is 3.2% more than in the previous year. In the EU, the size of the broadly defined shadow banking sector amounted to €37 trillion in total assets at the end of 2015. This equals 36% of the total EU financial sector assets and constitutes a growth of 27% since 2012.Footnote 49

Just as in the traditional banking sector, credit intermediation in the shadow banking sector revolves around the transformation of maturities.Footnote 50 Short-term debt is used to fund securitised assets such as Asset-Backed Securities (ABS). However, a key characteristic of shadow banking is that it does not fund itself with deposits. Instead, funds are attracted through a variety of wholesale short-term borrowing markets. These include commercial paper, asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP), unsecured interbank lending, and secured repo borrowing.Footnote 51

2.3 The Risks of Shadow Banking

Credit intermediation which is performed through the shadow banking sector and is not driven by regulatory arbitrage can generate economic valueFootnote 52 and render the financial system more resilient by providing an alternative to bank funding.Footnote 53 However, when non-bank institutions perform bank-like activities—i.e. engage in maturity and liquidity transformation and employ leverage—without being subject to prudential regulation and supervision, financial stability may be jeopardised.Footnote 54 Shadow banking activities that derive their value (exclusively) from avoiding costly regulation thus proved to be a central weakness of the financial system.Footnote 55 It follows that the less stringent—or even lack of—regulation and supervision of the shadow banking sector was not in accordance with the systemic risks posed by it.Footnote 56 These risks manifested themselves in 2008 when the lack of proper oversight, regulation and a fiscal backstop, in combination with high leverage and maturity mismatches, created such vulnerabilities that a relatively small shock could trigger widespread panic in the financial markets.

Such a shock occurred in 2007–2008 when a downturn in the US housing and mortgage market, provoked by excessive credit provision, led to losses on subprime mortgages and associated financial products.Footnote 57 Although the losses on subprime mortgages were substantial, running into the hundreds of billions of dollars, they were relatively small in the context of the total financial system. For example, the losses from subprime mortgages were no larger than those suffered when the Dotcom Bubble burst.Footnote 58 However, the consequences were substantially worse. This was because the subprime mortgage crisis interacted with and exposed deeper systemic vulnerabilities in the financial systemFootnote 59 in ways which did not occur in the case of the Dotcom Bubble.Footnote 60

Financial institutions had, through innovative financial engineering, created highly complex financial products. As the market shifted from an originate-to-hold to an originate-to-distribute model, loans were packaged as securities and sold to other financial institutions. Although such products can be used to allocate resources to where they are of most value, it can also reduce the stability of the financial system.Footnote 61 Their complexity makes it hard to assess the risks involved, leading to investment in financial products which, in hindsight, were highly toxic.Footnote 62 Additionally, and crucially, many risky financial instruments were held on the balance sheets of financial institutions.Footnote 63 Subsequent losses on subprime-related financial products proved devastating for the highly leveraged financial firms which held them on their balance sheets. Those losses extended well beyond the banking sector. Shadow bank entities such as investment funds, insurance companies (including monoline insurers which guaranteed mortgage securities) and other institutional investors all experienced massive losses related to the subprime mortgage market. It should be recalled that banks and shadow banking entities are highly interconnected as many different financial institutions are involved at various stages of the credit intermediation process.Footnote 64 Banks shifted risks off their balance sheets and into shadow bank entities in order to take advantage of regulatory arbitrage. However, when these entities failed, banks sometimes preferred to support them beyond their contractual obligation or equity ties, mainly to avoid reputational risks.Footnote 65 This is referred to as ‘step-in’ risk, as it provides an additional channel of contagion between the banking and the shadow banking system.Footnote 66 As a consequence, the systemic relevance of shadow bank entities stems for a large part from their connectedness with the rest of the financial system.Footnote 67

During the Global Financial Crisis, authorities were forced to take a range of unconventional measures to provide liquidity and stability to the financial markets, starting with their traditional function of lender of last resort. In the US the Fed provided a discount window to eligible commercial banks. This proved ineffective as concerns of being stigmatised made banks hesitant to use it.Footnote 68 Furthermore, for the purposes of the broader financial system, the Fed normally relied on the banks to lend part of the received liquidity to solvent non-bank institutions. But this did not happen to the extent that it had in the past.Footnote 69 This led to a number of programmes for the provision of liquidity to primary dealers.Footnote 70 Despite these efforts, Lehman Brothers—a shadow bank—filed for bankruptcy on 15 September 2008.Footnote 71

After Lehman Brother’s bankruptcy the markets for the rollover of short-term debt, through interbank lending, repo and ABCP, froze.Footnote 72 Uncertainty about the institutions’ health and about the prices of posted collateral caused lenders to stop extending credit.Footnote 73 Reserve Primary Fund, a money market fund (MMF), had heavily invested in commercial paper issued by Lehman Brothers. During the days following Lehman’s bankruptcy, redemption requests to Reserve Primary constituted about half of the fund’s liabilities. This caused Reserve Primary to ‘break the buck’ on 16 September 2008 when shares were redeemed below their 1$ face value. This caused money market funds to experience run-like behaviour.Footnote 74 This in turn left the US Department of Treasury no other option than to guarantee a net asset value of $1 on the shares of all MMFs in order to relieve panic in the financial markets.

Another notorious example of underperforming supervision, and the systemic risks posed by a shadow bank entity, was apparent in the case of American International Group (AIG). AIG’s Financial Products subsidiary sold enormous amounts of credit default swaps. Being adept at regulatory arbitrage, it managed to select the regulator least likely to restrict its practices: the Office of Thrift Supervision.Footnote 75

As has been extensively noted, the consequences of Lehman’s bankruptcy were more severe than imagined.Footnote 76 After Lehman, the scale and number of government programmes rapidly increased.

Most significantly, US Congress appropriated $700 billion for the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) on 3 October 2008, which allowed the Treasury to inject equity into failing financial institutions.Footnote 77 Consequently—between the liquidity facility, lending programs and asset purchasing programs by the Fed and the guarantees provided by the FDIC and the US Treasury—a near complete backstop was created during the crisis for the shadow banking sector.Footnote 78 In this regard Barry Eichengreen noted that ‘the failure to endow the Treasury and the Fed with the authority to deal with the insolvency of non-bank financial institutions was the single most important policy failure of the crisis’.Footnote 79

Meanwhile, Europe lacked a robust pan-European approach to failing financial institutions. National governments were left to their own devices. However, this fragmentation along national borders was not reflected by financial institutions. Benefiting from the unification of the European markets, they had stretched their operations over many countries. In 2008, panic on the financial markets culminated in a joint commitment by the EU leaders to support the major financial institutions and avoid their bankruptcy by providing sufficient liquidity, funding and capital resources.Footnote 80 As a consequence, between 2008 and 2012 national authorities spent a total of €1.5 trillion on state aid in support of the financial system.Footnote 81

Many of the financial institutions which had to be bailed out because of the systemic risk consequences—commonly referred to as Too-Big-To-Fail—were in fact non-bank financial institutions. They ranged, inter alia, from investment banks (e.g. Bear Stearns and Merrill Lynch) and insurance companies (AIG)Footnote 82 to asset managers (Reserve Primary Fund).

In conclusion, the belief that shadow banking activities did not pose systemic risks proved to be false. One of the important lessons from the Global Financial Crisis was that the failure of non-bank financial institutions can—and has—created systemic risk, especially through their interconnectedness with and contagion of the wider financial system.Footnote 83 Financial institutions which deal in bank-like risks by providing maturity and/or liquidity transformation, and high leverage are particularly susceptible to shocks. Shadow banks relied heavily (although not exclusively) on short-term liabilities for funding.Footnote 84 Short-term funding, typically through (overnight) asset-backed commercial paper and repos, requires the institution to roll over its debt when it matures. This rendered shadow banking entities vulnerable to runs on their short-term funding, equivalent to bank runs.Footnote 85 Indeed, lacking funding through insured deposits they were even more vulnerable to runs, whereby panic could easily lead to contagion.Footnote 86 Risks posed by shadow bank entities were aggravated by the fact that such institutions were only subjected to light regulation and supervision. In consequence, the belief that no fiscal backstop to the shadow banking sector was necessary proved equally false: during the crisis large publicly funded bailouts proved necessary.

While the foregoing illustrates the enormous threat posed by the shadow banking sector as exemplified during the Global Financial Crisis, it must be stressed that the financial sector is constantly changing and evolving. Specific risks which manifested themselves in the past may diminish, while other, new, risks materialise.Footnote 87 Future financial crises will probably not mirror previous crises and have different roots. It is therefore crucial to have a forward-looking system in place for identifying potential systemic risks in the financial sector. And once such risks have been identified, they must be brought within a commensurate regulatory perimeter.Footnote 88

3 International Initiatives to Address Systemic Risk Posed by Non-Bank Financial Institutions

As seen above, systemic risk is not confined to the banking system. This calls into question the notion that systemic risk can be controlled by focusing chiefly on bank regulation and supervision. Shadow banks operating outside the regulatory perimeter for banks were able to accumulate systemic risks virtually unchecked. Unlike the jurisdiction of financial supervisors, the build-up of systemic risk was not confined to particular countries or sectors. Furthermore, by focusing on the micro-prudential health, the authorities overlooked and neglected supervision of the safety of the financial system as a whole. This is not to say that the regulation and supervision of banks did not need improving, as it clearly did, but a one-sided focus on bank regulation failed to take account of the risks and consigned them to the shadow sector.

A range of international initiatives designed to increase financial stability were undertaken in response. During the G20 London summit in 2009 it was agreed, among other things, that regulators and supervisors must reduce the scope for regulatory arbitrage. To this end, regulation and oversight should extend to ‘all systemically important financial institutions, instruments and markets’.Footnote 89 A few months later, at the G20 Pittsburgh summit, the world leaders reiterated that ‘all firms whose failure could pose a risk to financial stability must be subject to consistent, consolidated supervision and regulation with high standards’.Footnote 90 It is, therefore, important to have an adequate regulatory perimeter which ensures that all financial activities and institutions that may pose systemic risk are appropriately regulated.Footnote 91 The supervision of individual financial institutions has to take into account—and be complemented by—supervision of the robustness of the financial system as a whole. This is referred to as macroprudential supervision.Footnote 92

The G20 tasked a new organ, the Financial Stability Board (FSB), with the development and coordination of a comprehensive framework for global regulation and oversight of the global financial system.Footnote 93 As part of this task, the FSB has been designing policy recommendations addressing the Too-Big-To-Fail problem of SIFIs, while at the same time preventing regulatory arbitrage as stricter regulation in one sector might lead to migration of risky activities elsewhere.Footnote 94

In order to alleviate Too-Big-To-Fail, the FSB requires a number of integrated policies comprising:

-

Resolution instruments which enable authorities to resolve financial institutions in an orderly manner.

-

Resolvability assessments and recovery and resolution planning for global systemically important financial institutions, and for the development of institution-specific cross-border cooperation agreements.

-

Requirements for financial institutions determined to be globally systemically important to have additional loss absorption capacity tailored to the impact of their default.

-

More intensive and effective supervision of all SIFIs.Footnote 95

According to the FSB, the crisis revealed that some supervisors failed to make appropriate risk assessments leading to an unwarranted assertion that institutions were highly capitalised and liquid, even as some later failed. In consequence, the FSB assessed that the supervision of SIFIs ‘must clearly be more intense, more effective, and more reliable’.Footnote 96

This resulted in a number of recommendations in regard to supervision of SIFIs, including the following:

-

National supervisory authorities should have the powers to apply differentiated supervisory requirements and intensity of supervision of SIFIs based on the risk they pose to the financial system.

-

All national supervisory authorities should have appropriate mandates, independence and resources to identify risks early and intervene to require changes within an institution, as needed, to prevent unsound practices and take appropriate counter-measures to safeguard against the additional systemic risks.

-

Jurisdictions should provide for a national supervisory framework that enables effective consolidated supervision by addressing ambiguities of responsibilities, impairments related to information gathering and assessment when multiple supervisors are overseeing the institution and its affiliates.Footnote 97

3.1 Determining Systemic Risk

Reducing the systemic and moral hazard risks posed by SIFIs starts with the identification of such institutions. For this purpose international methodologies have been created for identifying global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) and insurers (G-SIIs). Furthermore, in March 2015 the FSB and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) released a second consultative document regarding the assessment methodologies for identifying Non-Bank Non-Insurer Global Systemically Important Financial Institutions.Footnote 98

The latter aims to provide a framework for determining whether a non-bank non-insurer financial entity is globally systemically relevant (NBNI G-SIFI). The proposed methodologies are designed to identify NBNI financial institutions whose distress or disorderly failure, because of their size, complexity and systemic interconnectedness, would cause significant disruption to the wider financial system and economic activity at the global level.Footnote 99 Besides giving sector specific indicators, it provides basic impact factors that should be taken into account. These are a financial institution’s size, interconnectedness, substitutability, complexity and global, cross-jurisdictional, activities.

In regard to asset management activities, the FSB recently presented policy recommendations to address structural vulnerabilities from asset management activities.Footnote 100 As illustrated by the demise of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM), a leveraged hedge fund, and the run on MMFs during the 2008 crisis, asset management structures can pose systemic risk.Footnote 101 The FSB identified four important structural vulnerabilities: (i) liquidity mismatch between fund investments and redemption terms and conditions for open-ended funds;Footnote 102 (ii) leverage; (iii) operational risk and challenges in transferring investment mandates in stressed conditions; (iv) securities lending activities of asset managers and funds.

Besides developing NBNI G-SIFI methodology and making sector-specific recommendations, the FSB has provided a framework for the detection of elevated systemic risk posed by non-bank entities. To this end, it proposes a two-pronged strategy, entailing (1) enhanced monitoring and (2) strengthening of oversight and regulation.Footnote 103 The FSB finds that, when necessary to ensure financial stability, relevant authorities should have the power to bring non-bank financial entities into regulatory and supervisory oversight. Therefore authorities should, as a key prerequisite, have a regime to define, expand, and keep up to date the regulatory perimeter necessary to ensure financial stability.Footnote 104

3.1.1 Monitoring Non-Bank Financial Entities That Could Pose Financial Stability Risks

The FSB has adopted a monitoring framework designed to identify the build-up of systemic risks in the shadow banking system. It provides both for a wide-net approach, which captures all non-bank credit intermediation, and a narrow approach. The latter allows authorities to focus on the subset of non-bank credit intermediation where there are (i) developments that increase systemic risk (in particular maturity/liquidity transformation, imperfect credit risk transfer and/or leverage), and/or (ii) indications of regulatory arbitrage that is undermining the benefits of financial regulation.Footnote 105

The monitoring of systemic risk must take an risk-based approach in which the extent of a firm’s involvement in shadow banking has to be judged by its underlying economic activities, rather than legal names or forms.Footnote 106 This is especially relevant as any non-bank financial institution could perform shadow banking activities.Footnote 107 Such a functional approach allows for a consistent assessment of shadow banking activities and the risk they pose to financial stability. It allows new structures and innovations to fall within the monitoring scope. A comparable approach is present in the FSB’s classification of non-bank financial entities into five different economic functions (see Table 1).

The FSB finds that jurisdictions should establish a systematic process involving all relevant domestic authorities in order to review shadow banking risks posed by non-bank financial entities or activities, and ensure that any entities or activities that could pose material risks to financial stability are brought within the regulatory perimeter.Footnote 108 However, in its 2016 thematic review the FSB finds that few jurisdictions have such a systemic process in place. It recommends that, where such a process does not exist, there ‘may be merit for jurisdictions to establish a systematic process to ensure that non-bank financial entities that could pose financial stability risks are brought within the regulatory perimeter in a timely and proactive manner’.Footnote 109

The US is an example of a jurisdiction which does have in place a systematic process for reviewing the regulatory perimeter and bringing non-bank financial companies within (additional) regulatory and supervisory oversight. The US system will be discussed in more detail in Sect. 4 below.

3.2 Regulating Non-Bank Systemically Important Financial Institutions

As stated previously, while shadow bank entities might create systemic risk on their own, risks may also emerge indirectly through the interconnectedness of the shadow and regular banking sectors. Indeed, shadow banks tend to be closely connected with the regulated banking sector due to ownership linkages and explicit and implicit guarantees and as direct counterparties.Footnote 110 For example, the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) assesses that approximately 9% of the euro area credit institutions’ assets are loans to the euro area investment funds and Other Financial Institutions (OFI), or debt securities, equity and investment fund shares issued by those entities. Conversely, deposits from euro area investment funds and OFI constitute 7% of credit institution’ liabilities.Footnote 111

Regulatory response has thus developed broadly along two, not mutually exclusive, lines. First, efforts have been made to impose regulatory limits on the exposure of the traditional banking sector to the shadow banking sector. And, second, efforts are made to expand the regulatory perimeter to capture non-bank financial institutions.

In regard to the former, the Basel Committee for Banking Supervision has issued a final standard which sets out a supervisory framework for measuring and controlling large exposures.Footnote 112 The Basel exposure framework aims to serve as a backstop to risk-based capital requirements, as it should ensure that the maximum possible loss a bank could incur if a single counterparty or group of connected counterparties were to suddenly fail would not endanger the bank’s survival. In effect, this means that the total exposure of a bank to a single counterparty or to a group of connected counterparties must not exceed 25% of the bank’s total amount of Tier 1 capital.Footnote 113 Jurisdictions must implement the large exposure framework in full by 1 January 2019.

In the EU, limits to large exposures are specified in the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR), which by and large matches the Basel exposure framework.Footnote 114 Additionally, the CCR mandates the European Banking Authority (EBA) to provide guidelines for setting appropriate aggregate limits on shadow banking exposures or tighter individual limits on exposures to shadow banking entities which carry out banking activities outside a regulated framework. In its consultation paper on its draft guidelines, the EBA recognised that the Global Financial Crisis ‘has revealed previously unrecognised fault lines which can transmit risk from the shadow banking system to the regulated banking system, putting the stability of the entire financial system at risk’.Footnote 115 In its final guidelines, which came into effect on 1 January 2017, the EBA requires banks and investment firms to identify their individual exposures to shadow banking entities and the potential risks and the impact of those risks arising from these exposures.Footnote 116 These risks must, subsequently, be taken into account within the institution’s Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP) and capital planning.

In regard to step-in risks—i.e. financial support granted by a bank to a troubled non-bank financial entity, beyond any contractual obligations—the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision has published a consultative document on guidelines for the identification and management of such risks.Footnote 117

3.2.1 Non-Bank SIFI Regulation

In regard to the expansion of the regulatory perimeter to ensure that it encompasses non-bank financial institutions and activities that could pose financial stability risks, the FSB has developed policy recommendations for strengthening the oversight and regulation of shadow banking sectors.Footnote 118

The FSB presents a policy framework, consisting of overarching principles that authorities should apply for all economic functions and a specific toolkit for each economic function, in order to mitigate systemic risks posed by a shadow banking entity associated with its specific economic function (see Table 2).Footnote 119

After being tasked by the G20 with addressing Too-Big-To-Fail problems, the FSB also produced a number of policy recommendations designed to reduce the chance of failure of financial institutions and minimise the impact of any such failure. Of primary importance are its Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions (KA), which set out the core elements that the FSB considers necessary for an effective resolution regime.

The FSB recommends that any financial institution that could be systemically significant or critical if it fails should be subject to a resolution regime. Resolution should be initiated when a financial institution is no longer viable or likely to be no longer viable, and when it has no reasonable prospect of becoming viable again.

Effective resolution regimes should, according to the FSB:

-

(i)

ensure continuity of systemically important financial services, and payment, clearing and settlement functions;

-

(ii)

protect, where applicable and in coordination with the relevant insurance schemes and arrangements, such depositors, insurance policy holders and investors as are covered by such schemes and arrangements, and ensure the rapid return of segregated client assets;

-

(iii)

allocate losses to firm owners (shareholders) and unsecured and uninsured creditors in a manner that respects the hierarchy of claims;

-

(iv)

not rely on public solvency support and not create an expectation that such support will be available;

-

(v)

avoid unnecessary destruction of value, and therefore seek to minimise the overall costs of resolution in home and host jurisdictions and, where consistent with the other objectives, losses for creditors;

-

(vi)

provide for speed and transparency and as much predictability as possible through legal and procedural clarity and advanced planning for orderly resolution;

-

(vii)

provide a mandate in law for cooperation, information exchange and coordination domestically and with relevant foreign resolution authorities before and during a resolution;

-

(viii)

ensure that non-viable firms can exit the market in an orderly way; and

-

(ix)

be credible, and thereby enhance market discipline and provide incentives for market-based solutions.Footnote 120

4 Policy Response in the United States—Systemic Risk Regulation

This section discusses some notable regulatory reforms in the US in relation to the identification and subsequent regulation and supervision of non-bank systemically important financial institutions. The US practice can provide valuable insights for possible European reform along the same or similar lines.

As illustrated in Sect. 2, systemic risk in the US manifested itself not only in the traditional banking sector but also to a significant degree in the shadow banking sector. Activities in the lightly regulated shadow banking sector—e.g. investment banks and money market funds—proved the most damaging. The combination of high leverage and the dependence on short-term (overnight) funding to finance long-term investments rendered non-bank financial institutions susceptible to modern bank runs. The withdrawal of funds, or refusal to roll over existing debt, forced fire sales, which led to a further decline in asset prices. As asset prices deteriorated, the solvency of other financial institutions holding similar assets became uncertain, freezing short-term funding and leading to additional fire sales.Footnote 121

The main regulatory response of the crisis was the Dodd–Frank Act, which was signed into law by President Obama on 21 July 2010. Its chief goal was to address the issues of financial stability and systemic risk and to prevent further bailouts of the financial system at the taxpayers’ expense.Footnote 122 The Dodd–Frank Act applies a more risk-based approach to the identification and regulation of non-bank SIFIs in two notable ways. First, by introducing a Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), a new federal regulator, charged with monitoring systemic risk and determining what non-bank financial institutions could pose a threat to the financial stability of the US. Second, it creates a resolution regime for non-bank financial institutions whose failure poses a significant risk to the financial stability of the US. Both reforms are discussed in the following sections.

4.1 Designation by the Financial Stability Oversight Council

In general, the FSOC has two main tasks. First, to identify risks to the financial stability of the US emanating from non-bank financial institutions. Second, to respond to emerging threats to the stability of the United States financial system.Footnote 123

The FSOC is charged with determining whether a non-bank financial companyFootnote 124 is systemically important.Footnote 125 The designation may be made by an affirmative vote of at least two-third of the FSOC’s voting members, including the Chairperson. In consequence, a designated company is supervised by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (FRB) and is subject to the prudential standards set in Title I of the Dodd–Frank Act.

More specifically, a designation may be made under either of two determination standards: (i) when material financial distress at the company could pose a threat to the financial stability of the US; or (ii) when the very ‘nature, scope, size, scale, concentration, interconnectedness, or mix’ of the company’s activities could pose the same threat.Footnote 126

Industry practitioners, commenting on the scope of the FSOC’s non-bank SIFI determination, found that the particular segment of the financial industry they represented does not pose a threat to US financial stability and should not generally be subject to a determination.Footnote 127 The FSOC, however, contended that it does not intend to provide industry-based exemptions from potential non-bank SIFI determinations. Instead it will apply the statutory standards to determine whether a non-bank financial company qualifies as systemically important.Footnote 128 The Dodd–Frank Act identified ten factors that the FSOC must consider when determining whether material financial distress at a non-bank financial company could pose a threat to the US economy.

-

(A)

the extent of the leverage of the company;

-

(B)

the extent and nature of the off-balance-sheet exposures of the company;

-

(C)

the extent and nature of the transactions and relationships of the company with other significant non-bank financial companies and significant bank holding companies;

-

(D)

the importance of the company as a source of credit for households, businesses, and State and local governments and as a source of liquidity for the United States financial system;

-

(E)

the importance of the company as a source of credit for low-income, minority, or underserved communities, and the impact that the failure of such company would have on the availability of credit in such communities;

-

(F)

the extent to which assets are managed rather than owned by the company, and the extent to which ownership of assets under management is diffuse;

-

(G)

the nature, scope, size, scale, concentration, interconnectedness, and mix of the activities of the company;

-

(H)

the degree to which the company is already regulated by 1 or more primary financial regulatory agencies;

-

(I)

the amount and nature of the financial assets of the company;

-

(J)

the amount and types of the liabilities of the company, including the degree of reliance on short-term funding; and

-

(K)

any other risk-related factors that the Council deems appropriate.

The FSOC adopted a final rule and interpretive guidance for non-bank financial company determinations, in which it grouped all factors relevant to the risk determination in six categories.Footnote 129 These six categories, referred to as the ‘analytic framework for determinations’, are: (i) size, (ii) interconnectedness, (iii) substitutability, (iv) leverage, (v) liquidity risk and maturity mismatch, and (vi) existing regulatory scrutiny. Three of these six categories—size, substitutability and interconnectedness—aim to assess the potential impact of the non-bank financial company’s financial distress on the broader economy. The purpose of the other three—leverage, liquidity risk and maturity mismatch, and existing regulatory scrutiny of the non-bank financial company—is to assess the vulnerability of a company to financial distress.

In its Rule and Guidance, the FSOC developed a three-stage process for identifying non-bank financial companies for determination under non-emergency situations.Footnote 130 In stage 1, the FSOC applies six quantitative thresholds to a broad group of non-bank financial companies to identify companies that will be subject to further evaluation by the Council.

4.1.1 Stage 1

First, a financial company has to have at least $50 billion in total consolidated assets. Additionally it has to meet at least one of the following thresholds:

-

$30 billion in credit default swaps for which the company is the reference entity;

-

$3.5 billion in derivative liabilities;

-

$20 billion in total debt outstanding;

-

15 to 1 leverage ratio;

-

10% short-term debt-to-asset ratio.

Companies that have passed the first stage are subject to active review by the FSOC in stage 2. Additionally, a non-bank financial company which does not meet the thresholds of the first stage may still be subjected to a stage 2 analysis by the FSOC based on other firm-specific qualitative or quantitative factors. After all, the uniform quantitative thresholds may not capture all types of non-bank financial companies and all of the potential ways in which a non-bank financial company could pose a threat to financial stability.Footnote 131

4.1.2 Stage 2

In stage 2, the FSOC, conducts a robust analysis of the potential threat that a company could pose to US financial stability. In contrast to the application of uniform criteria under stage 1, stage 2 evaluates the risk profile and characteristics of each individual non-bank financial company. This in line with the belief that systemically important designation cannot be reduced to a formula.Footnote 132 This review is performed on the basis of a company’s: (i) size, (ii) interconnectedness, (iii) substitutability, (iv) leverage, (v) liquidity risk and maturity mismatch, and (vi) existing regulatory scrutiny. It is interesting to note that a key factor of the determination is the extent to which the non-bank financial company is subject to regulation. This shows that the designation process actively aims to remedy gaps in regulation and counteracts regulatory arbitrage and thus draws systemically important shadow banks within the regulatory perimeter.

4.1.3 Stage 3

Companies that are subsequently advanced to stage 3 are informed through a ‘Notice of Consideration’ that they are being considered for a ‘Proposed Determination’. Review under stage 3 focuses on the non-bank financial company’s potential to pose a threat to US financial stability because of the company’s material financial distress or the nature, scope, size, scale, concentration, interconnectedness or mix of its activities. The Notice of Consideration will likely include a request for information deemed relevant to the FSOC’s evaluation. The information necessary may vary significantly based on the non-bank financial company’s business and activities and the information already available. However, the information requests will likely involve both qualitative and quantitative data.

The FSOC indicates that an information request may include confidential business information.Footnote 133 The additional information helps the FSOC to gain a complete image of the systemic risk posed by a company. Factors such the opacity of the non-bank financial company’s operations, its complexity, and the extent to which it is subject to existing regulatory scrutiny and the nature of such scrutiny, may not directly cause systemic risks but could mitigate or aggravate them.

Additionally, the FSOC makes an in-depth analysis of the resolvability of the company. This entails assessing the complexity of the non-bank company’s legal, funding, and operational structure, and any obstacles to the rapid and orderly resolution of the company.

Based on the analyses conducted in stages 2 and 3, a non-bank financial company may be considered for a Proposed Determination. The FSOC may, by a vote of two-thirds of its members (including an affirmative vote of the Council Chairperson), make a Proposed Determination with respect to a non-bank financial company. After the company has been notified of its proposed determination and given the chance to contest it through a non-public hearing, the FSOC will determine by a vote of two-thirds of its voting members whether or not to subject such a company to supervision by the FRB and the prudential standards from Title 1 of the Dodd-Frank Act.

The FSOC designated American International Group (AIG), General Electric Capital Corporation, Prudential Financial and MetLife to be non-bank financial companies whose material financial distress could pose a threat to US financial stability. Metlife successfully appealed its designation in first instance, with an appeal still pending.Footnote 134 The designation of GE Capital Global Holdings was rescinded by the FSOC on 28 June 2016 after it fundamentally changed its business.Footnote 135 Additionally, the FSOC designated eight financial market utilities as systemically important. Recently, the FSOC started considering asset managers for systemic designation.Footnote 136

4.1.4 Judicial Protection against Designation

Following a Proposed Determination, the FSOC provides a written notice of the Proposed Determination to the non-bank financial company. This includes an explanation of the basis of the Proposed Determination. A non-bank financial company that is subject to a Proposed Determination may, within 30 days of receiving any notice of a proposed determination, request a non-public hearing to contest the Proposed Determination.Footnote 137 The FSOC must notify the company of its final determination within 60 days after the hearing.

The company subjected to a final determination may, within 30 days after receiving the notice of final determination, bring an action in the United States district court for the judicial district in which the company’s home office is located, or in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, for an order requiring that the final determination be rescinded. The court’s review is limited to determining whether the final determination was arbitrary and capricious.

American insurance company Metlife brought such proceedings before the US District Court of Columbia, complaining inter alia that the FSOC had not followed its own regulations in designating Metlife as a non-bank SIFI and had failed to examine the costs of its designation.

The judicial review by reference to the arbitrary and capricious criterion is narrow as the court is not able to substitute its judgment for that of the agency.Footnote 138 It may only therefore consider ‘whether the decision was based on a consideration of the relevant factors and whether there has been a clear error of judgment’.Footnote 139 This does mean, however, that the court must consider whether an agency has engaged in reasoned decision-making and has not departed from a prior policy or disregarded its own rules.

Applying this test led the District Court of Colombia to conclude that

FSOC made critical departures from two of the standards it adopted in its Guidance, never explaining such departures or even recognizing them as such. That alone renders FSOC’s determination process fatally flawed. Additionally, FSOC purposefully omitted any consideration of the cost of designation to MetLife. Thus, FSOC assumed the upside benefits of designation (even without specific standards from the Federal Reserve) but not the downside costs of its decision. That is arbitrary and capricious under the latest Supreme Court precedent.Footnote 140

Subsequently, on 30 March 2016, the Supreme Court quashed the FSOC’s designation of Metlife as a non-bank SIFI.

4.2 Supervision of Non-Bank SIFIs

The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (FRB) is tasked with the primary supervision of systemically important financial institutions.Footnote 141 This includes all bank holding companies with a minimum of $50 billion in assets and all non-bank financial companies which have been designated as systemically important by the FSOC.Footnote 142 The FRB is tasked with establishing enhanced prudential standards for non-bank financial companies which are deemed systemically important.Footnote 143

The FRB may establish such enhanced prudential standards on its own initiative or after a recommendation of the FSOC.Footnote 144 The prudential standards developed by the FRB may differentiate between institutions on an individual or categorical basis, thus allowing for the creation of tailored prudential requirements.Footnote 145 The FRB may, therefore, take into consideration the capital structure, riskiness, complexity, financial activities (including the financial activities of their subsidiaries), size, and any other risk-related factors of the financial institution that the FRB deems appropriate. Such a flexible approach to regulation is warranted given the differences in business model and risks between, for instance, insurers and banks. The prudential standards developed by the FRB includes (i) risk-based capital requirements and leverage limits; (ii) liquidity requirements; (iii) overall risk management requirements; (iv) resolution plan and credit exposure report requirements; and (v) concentration limits.Footnote 146

The FRB may establish additional prudential standards for non-bank financial companies that include (i) a contingent capital requirement; (ii) enhanced public disclosures; (iii) short-term debt limits; and (iv) such other prudential standards as the FRB, on its own or pursuant to a recommendation made by the FSOC, determines are appropriate.Footnote 147

In the summer of 2016 the FRB issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking regarding approaches to regulatory capital requirements for depository institution holding companies significantly engaged in insurance activities, and non-bank financial companies determined by the FSOC that have significant insurance activities.Footnote 148 In regard to FSOC designated nonbank financial companies with significant insurance activities—as discussed these are currently AIG and Prudential Financial—the advanced notice proposes a categorization of the insurance firm’s assets and insurance liabilities into risk segments and determine the consolidated required capital by applying risk factors to the amounts in each segment.Footnote 149

4.2.1 Living Wills

The Dodd–Frank Act provides that (i) each non-bank financial company designated by the FSOC as systemically important and supervised by the FRB and (ii) bank holding companies with consolidated assets amounting to a minimum of $50bn, periodically have to provide the FRB, FSOC and the FDIC with a plan for their rapid and orderly resolution in the event of material financial distress or failure.Footnote 150 These resolution plans, commonly known as ‘living wills’, include:

-

(A)

information regarding the manner and extent to which any insured depository institution affiliated with the company is adequately protected from risks arising from the activities of any non-bank subsidiaries of the company.

-

(B)

full descriptions of the ownership structure, assets, liabilities, and contractual obligations of the company;

-

(C)

identification of the cross-guarantees tied to different securities, identification of major counterparties, and a process for determining to whom the collateral of the company is pledged; and

-

(D)

any other information that the Board of Governors and the Corporation jointly require by rule or order.Footnote 151

On 17 October 2011 the FRB approved a joint rule with the FDIC, implementing the resolution plan requirements of the Dodd-Frank Act.Footnote 152 The rule requires covered firms to perform a strategic analysis of how they can be resolved under the Bankruptcy Code in a way that would not pose systemic risk to the financial system.Footnote 153

A key goal of the actions required in order to prepare a living will is the reduction of the interconnectedness between legal entities within a firm as ‘the inability to resolve one legal entity without causing knock-on effects that may propel the failure of other legal entities within the firm makes the orderly resolution of one of these firms extremely problematic’.Footnote 154 This does not necessarily imply that firms, under the living will obligation, have to break up, but, as Thomas Hoenig, vice chairman of the FDIC put it, ‘we want you to structure yourself so that your failure doesn’t bring the economy down next time’ and ‘If you can’t get to that point with your current organization structure, then you should sell assets to get to that state’.Footnote 155

Resolution plans will support the FDIC by providing an understanding of the covered companies’ structure and complexity as well as their resolution strategies and processes. Additionally, they will assist the FRB in its supervisory task to ensure that covered companies operate in a manner that is both safe and sound and that does not pose risks to financial stability. Finally, the resolution plans enhance the understanding of the US operations of foreign banks resulting in a more comprehensive and coordinated resolution strategy for a cross-border firm.Footnote 156

The living wills are reviewed by the FRB and the FDIC. They may jointly determine that a living will is not credible or would not facilitate an orderly resolution of the company concerned under the Bankruptcy Code. In such a case, the financial institution, after being notified by the FRB and the FDIC, has to resubmit a plan that remedies the deficiencies. If the firm fails to resubmit a credible plan, the FRB and the FDIC may jointly impose restrictions and requirements on the firm or its subsidiaries until it resubmits a plan that remedies the deficiencies. They may require more stringent capital, leverage, or liquidity ratios or restrict growth, activities, or operations.Footnote 157 If the firm fails to resubmit a revised resolution plan within 2 years after being required to fulfil additional requirements, the FRB and the FDIC, in consultation with the FSOC, may jointly order the firm to divest assets or operations to facilitate an orderly resolution under the Bankruptcy Code.

4.3 Resolution of Non-Bank SIFIs under OLA

While living wills are intended to identify and remove obstacles to orderly resolution under the Bankruptcy Code, in practice systemically important financial institutions, including bank holding companies, qualify for resolution under the Orderly Liquidation Authority (OLA).Footnote 158

Since the passing of the Dodd-Frank Act, the US has had three main regimes for resolving financial institutions. A general insolvency regime is provided for by the Bankruptcy Code. However, insured depository institutions (i.e. banks) are excluded from the Bankruptcy Code. Instead they are subjected to a specialised regime under federal law.Footnote 159 The Federal Deposit Insurance Company (FDIC) is charged with the application of this regime.

The Dodd–Frank Act also established the Orderly Liquidation Authority, which presents an alternative resolution regime for non-bank financial institutions, including bank holding companies. The OLA provide a liquidation regime for covered financial institutions in a manner that mitigates risks to financial stability and minimises moral hazard.Footnote 160 While, in principle, the Bankruptcy Code remains the default option, resolution under the OLA regime is preferred when normal bankruptcy proceedings would potentially harm financial stability.

The OLA applies to financial institutions that are (i) domestic bank holding companies, (ii) non-bank financial companies supervised by the FRB, (iii) any domestic company predominantly engaged in activities that the FRB has determined are financial in nature or incidental thereto, and (iv) any subsidiary of such companies that is predominantly engaged in activities that are financial in nature or incidental thereto (other than a subsidiary that is an insured depository institution or an insurance company).Footnote 161 Consequently, financial institutions that have been designated as systemically important by the FSOC fall within the meaning of ‘financial company’ under the OLA as they are supervised by the FRB.

Furthermore, in order for a financial company to become ‘covered’ by the OLA the following conditions must be met:Footnote 162

-

1.

in default or in danger of default;

-

2.

the failure of the financial company and its resolution under otherwise applicable Federal or State law would have serious adverse effects on financial stability in the United States;

-

3.

no viable private sector alternative is available;

-

4.

any effect on the claims or interests of creditors, counterparties, and shareholders of the financial company and other market participants as a result of actions to be taken under this subchapter is appropriate, given the impact that any action taken under this subchapter would have on financial stability in the United States;

-

5.

any action under OLA would avoid or mitigate such adverse effects;Footnote 163

-

6.

a Federal regulatory agency has ordered the financial company to convert all of its convertible debt instruments that are subject to the regulatory order.

These determinations are made by the Secretary of Treasury, acting in consultation with the President and after receiving recommendations from the FRB and the FDIC or (in the case of a broker or dealer) the FRB and the SEC. Pursuant to a determination, a financial company may be placed under OLA in order to liquidate it in a manner that mitigates significant risk to the financial stability of the US and minimises moral hazard.

Under an OLA resolution, the FDIC must act as the receiver for the company. It therefore succeeds to all rights and powers of the covered financial company. The FDIC will operate, and conduct all business of, the financial company during its orderly liquidation. It may also appoint itself as receiver of any failing domestic covered subsidiary of the financial company if this would avoid or mitigate adverse effects on the financial stability and such action would facilitate the orderly liquidation of the covered financial company.

4.3.1 Resolution Under OLA

With the introduction of OLA, the treatment of qualified financial contracts has been subject to a different treatment than under normal bankruptcy. Qualified financial contracts (QFCs) are any securities contract, commodity contract, forward contract, repurchase agreement and swap agreement, and any agreement deemed similar by the FDIC.Footnote 164 Normally a financial companies’ default triggers ‘safe harbour’ provisions enabling counterparties to terminate derivative contracts and take the collateral. This can accelerate its decline and lead to value destruction, as counterparties race to terminate derivative contracts with the failing institution.Footnote 165

However, under OLA safe harbour provisions, specifically the right to terminate, liquidate or net a QFC may not be exercised during one business day after the FDIC has been appointed receiver.Footnote 166 Furthermore, walkaway clauses—which suspend, condition, or extinguish a payment obligation—are rendered unenforceable.Footnote 167 This gives the FDIC some time to find a third-party buyer for these contracts. According to the FDIC, this provides market certainty and stability and preserves the value represented by the contracts.Footnote 168

A ‘top-down’ approach to resolution is applied, whereby the top of the financial group (i.e. the parent company level) is placed into receivership and resolution powers are applied by a single resolution authority at this level. The OLA provides the FDIC with the power to merge a company with another company or transfer any asset or liability to another company or a new FSOC-created bridge financial company.Footnote 169 The FDIC does not need to obtain approval for its resolution actions, except approval under antitrust law when it concerns a merger.

Transfer of specific assets and liabilities to a bridge financial company may be used to separate ‘good’ from ‘bad’ assets. Assets such as investments in subsidiaries would be transferred to the bridge company. Through capitalisation of the bridge financial company, by issuing new debt and equity or temporary operating funding from the FDIC,Footnote 170 it will be able to provide support to its subsidiaries, thereby ensuring that they can continue operations. The status as bridge company terminates, barring earlier termination, at the latest after 2 years, with the possibility of an extension for no more than three additional one-year periods.Footnote 171

Left behind in the failed parent company are the bad assets together with equity, subordinated debt and senior unsecured debt. Claims against the receivership are paid according to a statutory priority.Footnote 172 At the minimum all creditors must receive at least the amount that they would have received if the FDIC had the company been liquidated under Chapter 7 of the Bankruptcy Code. Creditor’s claims in the receivership are satisfied by the issuance of securities representing debt and equity in the new holding company.Footnote 173 Such a securities-for-claims exchange, has the effect of what is commonly referred to as a bail-in and ensures that the new operations are well capitalized.Footnote 174

4.4 First Experiences with Non-bank SIFI Designation in the US

As previously mentioned, on 8 July 2013 the FSOC designated American International Group (AIG), General Electric Capital Corporation, Prudential Financial and MetLife as non-bank financial companies which could pose a threat to US financial stability.

After the FSOC’s designation of GE Capital, the latter fundamentally changed its business. From being one of the largest financial services companies in the United States and a significant source of credit to the US economy, it decreased its total assets by over 50%, moved away from short-term funding and reduced its interconnectedness with large financial institutions.Footnote 175 Moreover, it repelled its US depository institutions and no longer provides financing to consumers or small business customers in the United States. As a consequence the FSOC voted on June 28, 2016 to rescind GE Capital’s non-bank SIFI designation.

It seems that the FSOC’s designation of GE Capital had the positive effect of pulling a shadow banking entity within a suitable regulatory perimeter. Where it had earlier gained an advantage through regulatory arbitrage, this was offset by its designation. In consequence, it had the choice to either compete on a level-playing-field and be subjected to stricter oversight, capital/liquidity requirements, or restructure in such a manner that it no longer posed a systemic risk. GE Capital chose to do the latter. It should therefore be regarded as an early success of the Dodd-Franks designation regime as it pulled this shadow banking entity within the regulatory perimeter and effectively alleviated systemic risks.

Metlife’s successful appeal of its designation illustrates the importance of an effective judicial appeal possibility. While the authority in charge of designating non-bank SIFIs needs broad discretionary powers to identify and regulate systemic risk, its decisions must adhere to general principles of law in order to avoid the appearance of arbitrary decision-making.

In regard to future developments, it is interesting to note that the FSOC has adopted an open approach in order to address systemic risk wherever it might arise. Treasury Secretary Jacob J. Lew emphasised in a Wall Street Journal op-ed that ‘It is particularly important that FSOC look over the horizon to where future risks may develop’.Footnote 176 Interestingly, the FSOC is now in the process of examining whether asset managers might present risks that could threaten financial stability.Footnote 177 However, as stated previously, the Trump administration seems to prefer light-touch regulation.Footnote 178

5 Policy Response in the EU

As discussed in the previous section, the FSOC’s powers to designate a non-bank institution as systemically important and the possibility to liquidate financial institutions under the OLA mark the adoption of a more holistic approach to the identification and mitigation of the systemic risks posed by non-bank SIFIs. In the EU, the policy response to the global financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis has remained organised largely along sectoral lines. The most notable reform has been the creation of a European Banking Union (EBU) which entailed an extensive overhaul and transfer of bank supervision and resolution to the EU level.Footnote 179 Because the creation of the Banking Union is the single most important response to the manifestation of systemic risk in the eurozone, a short account of its institutional make-up and scope, especially in relation to shadow banking entities, is in order. This will also allow us to assess the feasibility of expanding its scope to capture systemically important shadow banking entities.

5.1 The European Banking Union