Abstract

This paper contributes to the literature on changes in the employment structure, focusing on the job quality created and destroyed over the recent years in the Italian Southern regions compared to Central and Northern ones and with European regions with similar characteristics. In the 2014–2019 period, the economic gap between Central-Northern regions and the South area has been widening. In South Italy, the share of workers with low quality occupations has further in-creased, while the rest of the country experienced a growth in high quality jobs. In particular, the employment growth in the South has mainly involved those traditional sectors (such as hotels and restaurants) that employ low-skilled workers, while Central-Northern regions have been driven by knowledge intensive services and high-skilled manufacturing. Even compared with other lagging regions in the European Union, Southern Italy showed less favourable trends, especially if compared to German and French areas.

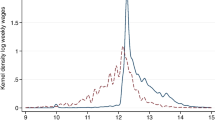

Source: LFS, Eurostat

Source: author’s calculation on LFS, Eurostat, and Eurofound. Ranking 2014. (1) Ranking is calculated at the national level on the total economy (which excludes activities of extraterritorial organisations and bodies). The private sector additionally excludes: Public administration and defence; compulsory social security; Education; Human health and social work activities

Source: author’s calculation on LFS, Eurostat, and Eurofound. Ranking 2014. (1) Ranking is calculated at the national level on the total economy (which excludes activities of extraterritorial organisations and bodies).—(2) Other LKIS include: H = Transporting and storage; L = Real estate activities; N = Administrative and support service activities; S = Other services activities; T = Activities of households as employers; undifferentiated goods—and services—producing activities of households for private use.—(3) Other KIS include: J = Information and communication; K = Financial and insurance activities; R = Arts, entertainment, and recreation.—(4) Professional, scientific, and technical activities.—(5) PA = Public administration and defence; compulsory social security.—(6) Health sector = Human health and social work activities

Source: author’s calculation on LFS, Eurostat, and Eurofound. Ranking 2014, computed at the national level on the total economy (which excludes activities of extraterritorial organisations and bodies). (1) Self-employed includes family workers

Source: author’s calculation on LFS, Eurostat, and Eurofound. Ranking 2014, computed at the national level on the total economy (which excludes activities of extraterritorial organisations and bodies)

Source: author’s calculation on LFS, Eurostat, and Eurofound. Ranking 2014, computed at the national level on the total economy (which excludes activities of extraterritorial organisations and bodies)

Source: author’s calculations on microdata LFS, Eurostat, and Eurofound. Ranking 2014, computed at the national level on the total economy (which excludes activities of extraterritorial organisations and bodies). (1) Group A includes: BE3 = Wallonia, Belgium; DE4 = Brandenburg, Germany; DE8 = Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany; DED = Saxony, Germany; DEE = Saxony-Anhalt, Germany; DEG = Thuringia, Germany; FRE = Nord-Pas-de-Calais-Picardie, France.—(2) Group B includes: ES1 = North-west Spain; ES4 = Central Spain; ES6 = South of Spain; EL4 = Nisia Aigaiou, Kriti Greece; EL5 = Voreia Ellada Greece; EL6 = Kentriki Ellada Greece, PT1 = Continental Portugal

Source: author’s calculations on microdata LFS, Eurostat, and Eurofound. Ranking 2014, computed at the national level on the total economy (which excludes activities of extraterritorial organisations and bodies). (1) Group A includes: BE3 = Wallonia, Belgium; DE4 = Brandenburg, Germany; DE8 = Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany; DED = Saxony, Germany; DEE = Saxony-Anhalt, Germany; DEG = Thuringia, Germany; FRE = Nord-Pas-de-Calais-Picardie, France.—(2) Group B includes: ES1 = North-west Spain; ES4 = Central Spain; ES6 = South of Spain; EL4 = Nisia Aigaiou, Kriti Greece; EL5 = Voreia Ellada Greece; EL6 = Kentriki Ellada Greece, PT1 = Continental Portugal

Source: author’s calculations on microdata LFS, Eurostat, and Eurofound. Ranking 2014, computed at the national level on the total economy (which excludes activities of extraterritorial organisations and bodies). Group A includes: BE3 = Wallonia, Belgium; DE4 = Brandenburg, Germany; DE8 = Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany; DED = Saxony, Germany; DEE = Saxony-Anhalt, Germany; DEG = Thuringia, Germany; FRE = Nord-Pas-de-Calais-Picardie, France.—(2) Group B includes: ES1 = North-west Spain; ES4 = Central Spain; ES6 = South of Spain; EL4 = Nisia Aigaiou, Kriti Greece; EL5 = Voreia Ellada Greece; EL6 = Kentriki Ellada Greece, PT1 = Continental Portugal.—(3) Other LKIS include: H = Transporting and storage; L = Real estate activities; N = Administrative and support service activities; S = Other services activities; T = Activities of households as employers; undifferentiated goods—and services—producing activities of households for own use.—(4) Other KIS include: J = Information and communication; K = Financial and insurance activities; R = Arts, entertainment and recreation.—(5) Professional, scientific and technical activities.—(6) PA = Public administration and defence; compulsory social security.—(7) Health sector = Human health and social work activities

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Due to data availability, in the following analysis we will resort to ISCO at the 2-digit level and NACE at the section level (alphabetical letters).

In the literature, wage-ranking has been widely used (e.g. Goos et al. 2009; Autor and Dorn 2013; Murphy and Oesch 2018; Basso 2019). However, jobs can be ranked according to other parameters such as their requested educational requirement (Olivieri 2012) or the tasks content (Autor et al. 2006; Basso 2019). All these indicators tend to be positively related to each other (De Bustillo et al. 2011). Wage data are generally more reliable statistics than other composite indicators, such as task indexes that may suffer from potential issues of measurement error (Basso 2019).

The combination of both databases allows to overcome some shortcomings of Eurostat wage data (see Basso 2019). The availability of a specific country ranking is an advantage with respect to the previous studies on the topic (for instance the study by Goos et al. 2009 relied on UK wage data to rank the jobs in all EU15 countries, including Italy).

We replicated the analysis by calculating terciles at a regional level. Results are qualitatively unchanged.

Extraterritorial organisations and bodies have been excluded from analysis activities.

For the purpose of the private sector analysis, public administration and defence, compulsory social security, education, human health and social work activities have been excluded.

Analogous findings hold when considering 2011 instead of 2014: results discussed in the rest of the paper are not significantly different when considering 2011 as the starting point of the analysis.

Similar results are obtained when considering the 2011–2019 period.

Compared to Albanese et al., two areas of the UK and one area of France (FRM = Corsica) have been excluded.

NUTS1 areas with a level of per capita GDP (in PPP terms) lower than 90 per cent of UE average EU-15 level in 2000 that had not converged towards EU average in the period between 2000 and 2013. In 2013, the level of per capita GDP (in PPP terms) remains below the average of EU level.

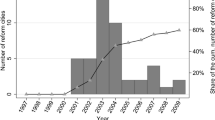

Eurofound focuses on 130 regions in 9 countries (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Czech Republic, Spain, Sweden e UK). Regions are classified in three groups according to the following criterions: regions with the presence of a capital city, regions with other big urban areas and regions with medium-large rural areas. The period of analysis is 2002–2017.

The ranking used for each region is the one constructed at the national level (a specific one for each country considered).

With the exception of Wallonia in Belgium, where the weight of intermediate quality occupations grew.

To account for a different use of part-time jobs across the areas we replicated the exercise in full-time equivalent terms and find similar results (Fig. 13).

Here, given the high number of analysed areas, it was unpractical to attribute to the South of Italy the rate of growth of each sector in each areas examined. Therefore, we graphically indicated (for each sector and occupation) the rate of growth in the considered period.

In the graphs we also included Italian Central and Norther regions in order to have all the areas examined in the same figure. However, Centre-Northern regions should be compared to other EU areas with similar characteristics.

References

Accetturo A, Bassanetti A, Bugamelli M, Faiella I, Finaldi Russo P, Franco D, Giacomelli S, Omiccioli M (2013) Productivity growth in Italy: a tale of a slow-motion change. Bank of Italy Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers) n. 193

Aimone Gigio L, Camussi S, Maccarrone V (2021) Changes in the employment structure and in job quality in Italy: a national and regional analysis. Bank of Italy, Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers), n.603

Autor D, Dorn D (2013) The growth of low-skill service jobs and the polarization of the US Labor Market. Am Econ Rev 103(5):1553–1597

Autor DH, Katz LF, Kearney MS (2006) The polarization of the US labor market. Am Econc Rev Pap Proc 96(2):189–194

Bank of Italy (2010) Il Mezzogiorno e la politica economica dell'Italia. Seminari e convegni, n.4, june 2010.

Bank of Italy (2018) Economie Regionali. L’economia delle regioni italiane. Dinamiche recenti e aspetti strutturali. N. 23, November 2018.

Bank of Italy (2020) Economie Regionali. L’economia delle regioni italiane. Dinamiche recenti e aspetti strutturali. N. 22, November 2020.

Basso G (2019) The evolution of the occupational structure in Italy in the last decade. Bank of Italy, Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers), n. 478

Bentivogli C, Ferraresi T, Monti P, Paniccia R, Rosignoli S (2018) Italian regions in global value chains: an input-output approach. Bank of Italy, Questioni di economia e finanza (Occasional Papers), n. 462

Bugamelli M, Fabiani S, Federico S, Felettigh A, Giordano C, Linarello A (2018a) Back on Track? A Macro-Micro Narrative of Italian Exports. Ital Econ J A Continuation of Rivista Italiana Degli Economisti and Giornale Degli Economisti 4:1–31

Bugamelli M, Lotti F, Amici M, Ciapanna E, Colonna F, Damuri F, Giacomelli S, Linarello A, Manaresi F, Palumbo G, Filippo (2018b) Productivity growth in Italy: a tale of a slow-motion change. Bank of Italy, Questioni di economia e finanza (Occasional Papers), n. 422.

Charnoz P, Orand M (2017) Technical change and automation of routine tasks: Evidence from local labour markets in France, 1999–2011. Economie Et Statistique/economics and Statistics, N 497–498:103–122

Consoli D, Sanchez-Barrioluengo M (2019) Polarisation and the growth of low-skill service jobs in Spanish local labor markets. J Reg Sci 59(1):145–162

De Bustillo RM, Fernández-Macías E, Antón J et al (2011) E pluribus unum? A critical review of job quality indicators. Soc Econ Rev 9(3):447–475

Dwyer RE, Wright EO (2012) Job growth and job polarization in the United States and Europe, 1995–2007. In: Fernández-Macías E, Hurley J, Storrie D (eds) Transformation of the employment structures in the EU and USA. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp 52–74

Eurofound (2008) ERM report 2008—More and better jobs: Patterns of employment expansion in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Eurofound (2014) Drivers of recent job polarisation and upgrading in Europe: European Jobs Monitor 2014. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Eurofound (2016) What do Europeans do at work? A task-based analysis: European Jobs Monitor 2016. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Eurofound (2017) Occupational change and wage inequality: European Jobs Monitor 2017. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Eurofound and European Commission Joint Research Centre (2019) European Jobs Monitor thematic report 2019 Shifts in the employment structure at regional level. European Jobs Monitor series. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

European Commission (2017) Competitiveness in low-income and low-growth regions. The lagging regions report. Brussels

European Commission (2022) Cohesion in Europe towards 2050. Eighth report on economic, social and territorial cohesion. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Fernández-Macías E (2012) Patterns of Employment expansion in Europe, 1995–2007. In: Fernández-Macías E, Hurley J, Storrie D (eds) Transformation of the employment structures in the EU and USA. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp 26–52

Fernández-Macías E, Hurley J, Storrie D (2012) Transformation of the employment structures in the EU and USA., New York

Goos M, Manning A (2007) Lousy and lovely jobs: The rising polarization of work in Britain. Rev Econ Stat 89(1):118–133

Goos M, Manning A, Salomons A (2009) Job polarization in Europe. AmEcon Rev Pap Proc 99(2):58–63

Jaimovich N, Siu HE (2012) The trend is the cycle: Job polarization and jobless recoveries. NBER Working Paper No. 18334, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA

Jones PS, Green AE (2009) The quantity and quality of jobs: changes in UK regions, 1997–2007. Environ Plan 41:2474–2495

Kaplanis I (2007) The geography of employment polarisation in Britain. Department of Geography and Environment, London School of Economics, London

Murphy EC, Oesch D (2018) Is Employment polarisation inevitable? Occupational change in Ireland and Switzerland, 1970–2010. Work Employ Soc 32(6):1099–1117

Nellas V, Olivieri E (2012) The change of job opportunities: The role of computerization and institutions. Quaderni DSE Working Paper No. 804, Department of Science and Economics, Bologna, Italy.

Oesch D, Piccitto G (2019) The polarization myth: occupational upgrading in Germany, Spain, Sweden, and the UK, 1992–2015. Work Occup 46(4):441–469

Olivieri E (2012) Il cambiamento delle opportunità lavorative. Bank of Italy, Questioni di economia e finanza (Occasional Papers) n. 117.

Svimez (2015) Rapporto Svimez 2015 sull’economia del Mezzogiorno. Bologna, Il Mulino.

Wright EO, Dwyer RE (2003) the patterns of job expansions in the United States: a comparison of the 1960s and 1990s. Soc Econ Rev 1:289–325

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We would like to thank Domenico Depalo and Roberto Torrini for their helpful comments. We thank the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound) for the data provided. We are grateful to participants at the internal seminars at the Bank of Italy for their useful suggestions.

Appendix

Appendix

See Figs. 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15.

Source: author’s calculation on LFS, Eurostat, and Eurofound. Ranking 2014. (1) Ranking is calculated at the national level on the total economy (which excludes activities of extraterritorial organisations and bodies).—(2) Other LKIS include: H = Transporting and storage; L = Real estate activities; N = Administrative and support service activities; S = Other services activities; T = Activities of households as employers; undifferentiated goods—and services—producing activities of households for own use.—(3) Other KIS include: J = Information and communication; K = Financial and insurance activities; R = Arts, entertainment and recreation.—(4) Professional, scientific and technical activities.—(5) PA = Public administration and defence; compulsory social security.—(6) Health sector = Human health and social work activities

Sectoral composition in the Italian macro-regions (1)(percentages; 2014).

Source: author’s calculation on LFS, Eurostat, and Eurofound. Ranking 2014. (1) Ranking is calculated at the national level on the total economy (which excludes activities of extraterritorial organisations and bodies).—(2) Other LKIS include: H = Transporting and storage; L = Real estate activities; N = Administrative and support service activities; S = Other services activities; T = Activities of households as employers; undifferentiated goods—and services—producing activities of households for own use.—(3) Other KIS include: J = Information and communication; K = Financial and insurance activities; R = Arts, entertainment and recreation.—(4) Professional, scientific and technical activities.—(5) PA = Public administration and defence; compulsory social security.—(6) Health sector = Human health and social work activities

Quality content of jobs per sector (1) (percentages; 2014).

Source: author’s calculations on microdata LFS, Eurostat, and Eurofound. Ranking 2014, computed at the national level on the total economy (which excludes activities of extraterritorial organisations and bodies). Part-time positions weighted for 0.5. (1) Group A includes: BE3 = Wallonia, Belgium; DE4 = Brandenburg, Germany; DE8 = Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany; DED = Saxony, Germany; DEE = Saxony-Anhalt, Germany; DEG = Thuringia, Germany; FRE = Nord-Pas-de-Calais-Picardie, France.—(2) Group B includes: ES1 = North-west Spain; ES4 = Central Spain; ES6 = South of Spain; EL4 = Nisia Aigaiou, Kriti Greece; EL5 = Voreia Ellada Greece; EL6 = Kentriki Ellada Greece, PT1 = Continental Portugal.—(3) Other LKIS include: H = Transporting and storage; L = Real estate activities; N = Administrative and support service activities; S = Other services activities; T = Activities of households as employers; undifferentiated goods—and services—producing activities of households for own use.—(4) Other KIS include: J = Information and communication; K = Financial and insurance activities; R = Arts, entertainment and recreation.—(5) Professional, scientific and technical activities.—(6) PA = Public administration and defence; compulsory social security.—(7) Health sector = Human health and social work activities

Changes in the share of total employments in full-time equivalent terms per tercile in the service sector (percentages; 2014–2019).

Source: author’s calculations on microdata LFS, Eurostat, and Eurofound. Ranking 2014, computed at the national level on the total economy (which excludes activities of extraterritorial organisations and bodies). (1) Group A includes: BE3 = Wallonia, Belgium; DE4 = Brandenburg, Germany; DE8 = Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany; DED = Saxony, Germany; DEE = Saxony-Anhalt, Germany; DEG = Thuringia, Germany; FRE = Nord-Pas-de-Calais-Picardie, France.—(2) Group B includes: ES1 = North-west Spain; ES4 = Central Spain; ES6 = South of Spain; EL4 = Nisia Aigaiou, Kriti Greece; EL5 = Voreia Ellada Greece; EL6 = Kentriki Ellada Greece, PT1 = Continental Portugal.—(3) Other LKIS include: H = Transporting and storage; L = Real estate activities; N = Administrative and support service activities; S = Other services activities; T = Activities of households as employers; undifferentiated goods—and services—producing activities of households for own use.—(4) Other KIS include: J = Information and communication; K = Financial and insurance activities; R = Arts, entertainment and recreation.—(5) Professional, scientific and technical activities.—(6) PA = Public administration and defence; compulsory social security.—(7) Health sector = Human health and social work activities

Sectoral composition of the EU regions (percentages; 2014).

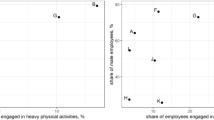

Comparison of the initial sectoral structure per geographical area and change in the related shares (1). (1) The graphs show for the main sectors—according to the classifications previously reported—the share of employed people in 2014 with the related change in the share in percentage points between 2014 and 2019. The extremes of the distribution were considered, e.g. those employed in the first tertile (corresponding to low qualifications) and in the third tertile (high qualifications). The countries shown are: MZ = South Italy; CN = Central-Northern Italy; BE3 = Wallonia, Belgium; DE4 = Brandenburg, Germany; DE8 = Mecklenburg-Pomerania, Germany; DED = Saxony, Germany; DEE = Saxony-Anhalt, Germany; DEG = Thuringia, Germany; FRE = North-Pas-de-Calais-Picard, France; ES1 = North-West Spain; ES4 = Central Spain; ES6 = South of Spain; EL4 = Aegean Islands, Crete Greece; EL5 = Northern Greece; EL6 = Central Greece; PT1 = Continental Portugal

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Camussi, S.A.M., Aimone Gigio, L. Changes in the Italian Employment Structure and Job Quality. Ital Econ J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-023-00247-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-023-00247-1