Abstract

Nonlinear phenomena are often encountered in various practical systems, and most of the nonlinear problems in science and engineering can be simply described by nonlinear equation, effectively solving nonlinear equation (NE) has aroused great interests of the academic and industrial communities. In this paper, a robust zeroing neural network (RZNN) activated by a new power versatile activation function (PVAF) is proposed and analyzed for finding the solutions of dynamic nonlinear equations (DNE) within fixed time in noise polluted environment. As compared with the previous ZNN model activated by other commonly used activation functions (AF), the main improvement of the presented RZNN model is the fixed-time convergence even in the presence of noises. In addition, the convergence time of the proposed RZNN model is irrelevant to its initial states, and it can be computed directly. Both the rigorous mathematical analysis and numerical simulation results are provided for the verification of the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed RZNN model. Moreover, a successful robotic manipulator path tracking example in noise polluted environment further demonstrates the practical application prospects of the proposed RZNN models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With the developments in modern science and technology, more and more natural phenomena and social problems cannot be simply depicted by linear relationship, and they should be described by complex nonlinear models, which makes the nonlinear science one of the most hottest research spots [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. In addition, most of the complex nonlinear models can be summarized by nonlinear equations, and solving nonlinear equation is of great importance for revealing the inner laws of these phenomena, especially for some practical scientific and engineering problems.

In the past decades, iterative methods have been commonly used in finding the solutions of nonlinear equation (NE), and the Newton iterative is one of the most effective methods, which converges to the theoretical roots of the nonlinear equations quadratically [11]. To improve the convergence performance of the Newton iterative for solving NE, many improved Newton-like iterations have been reported [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. However, the computational workload increases dramatically with the increasing order of the NE, which greatly decreases the effectiveness and accurateness of the iteration method owing to its intrinsic serial-processing limitations [21].

In recent years, the study of complex networks spans many different fields such as mathematics, life sciences, and engineering [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. The exploration of extremely complex topological structures and network dynamics has become a hot topic [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Among them, the recurrent neural network (RNN) develops very fast because of its inherent advantages of parallel processing and easy hardware implementation, and it has been deeply studied and investigated [37]. As one of the most effective computational approaches for finding the solutions of various equations [38,39,40], it has been widely applied in scientific and engineering fields [41,42,43,44]. The gradient-based neural network (GNN) and ZNN are two kinds of classic RNN, and the GNN is very effective and suitable to deal with large-scale static computational problems owing to its intrinsic advantages of parallel-processing ability. However, because the derivative information of the involved equation is not considered, the GNN approach cannot handle dynamic problems effectively. ZNN is a special RNN proposed in [45], and it has become an indispensable computational tool in dealing with time-varying problems. Comparing with GNN, ZNN has better robustness and effectiveness, and it has been widely used for solving dynamic equations [46,47,48].

The convergence performance and robustness of the ZNN are closely related to its activation functions (AFs), and choosing different AF will result in different robustness and effectiveness of the ZNN model. Considering the above facts, various novel AFs are proposed for the improvement of the ZNN [49, 50]. A specially constructed AF (sign-bi-power AF, SBPAF) [51] enables the ZNN model to develop from exponential convergence to finite time convergence, which further strengthens the real-time computing capabilities of the ZNN model. Noise and interference are inevitable for any dynamic system, which seriously deteriorate the accuracy and efficiency of the existing neural network models. However, noise compatibility is rarely considered in the existing ZNN models, and they are vulnerable to be attacked by various noises. For the purpose of improving its noise compatibility, a NTZNN model is proposed in [52, 53], and it works properly under various noises, but it only achieves exponential convergence, not finite time convergence or fixed time convergence. Considering the above issues, an NNTZNN model activated by a new versatile AF (VAF) is presented in [54], and the model in [54] achieves fixed-time convergence and noise suppression simultaneously, which is a milestone for the development of ZNN. To further improve the effectiveness and robustness of the ZNN, a RZNN model activated by a new PVAF for solving DNE is proposed in this work.

The key contributions and innovations are summarized below.

-

(1)

A new PVAF is presented to greatly improve the convergence performance and robustness of the ZNN.

-

(2)

Based on the proposed new PVAF, a RZNN model is designed for finding the solution DNE, and detailed mathematical analysis of the robustness and fast convergence of the RZNN model is provided.

-

(3)

Numerical simulated results are conducted to further verify the better robustness, effectiveness and fixed-time convergence of the RZNN model even in the noise polluted environment. Problem formulation and RZNN model.

In this section, the problem formulation is presented first. Then, the design steps of the ZNN and RZNN models for solving DNE are introduced.

Dynamic nonlinear equation (DNE)

In mathematics, the DNE can be summarized below:

In Eq. (1), t is time, x(t) is the unknown dynamic parameter, and f(·) is the nonlinear function, and we assume that the DNE in (1) is solvable, and it at least has one solution. The purpose of this work is to design a NN to find the dynamic solution x(t) of the DNE (1) within fixed-time in the noise polluted environment, and the design procedure of the ZNN model for solving DNE (1) is introduced in the following part.

ZNN model for solving DNE

ZNN is a powerful and effective tool for solving dynamic problems. According to Ref. [45], the ZNN model for solving DNE can be constructed below:

First, let us define a dynamic error function e(t):

Here, if e(t) converges to 0, and the state solution x(t) will satisfy f(x(t), t) = 0. Solving the DNE in (1) is equivalent to enforce e(t) converges to 0.

Then, the following formula is adopted for the convergence of e(t):

where γ > 0 is an adjustable parameter related to convergence performance, and σ(·) is an AF.

At last, substituting (2) into (3), the ZNN models for solving DNE is realized in Eq. (4).

AF is closely related to the effectiveness and robustness of the ZNN model, and any monotonically increasing odd AF could be considered as AF for the ZNN model [55, 56]. The commonly used AFs for the ZNN model are listed in the following Table 1.

It is worthy to mention that noise suppression and fast convergence are two important performance indicators of nonlinear dynamics. Many researchers have been devoted to finding effective AFs to improve the convergence performance of the ZNN model, and all the AFs listed in Table 1 can enforce the ZNN model exponentially or finite-time stable in ideal no-noise environment. However, noise suppression ability of the ZNN model is rarely considered in the previous works. A new RZNN model simultaneously achieves noise suppression and fixed-time convergence will be introduced in the following part.

RZNN model

The new PVAF of this work is presented below:

where p > 0, q > 0, k1> 0, k2> 0, p ≠ q, and sgn(·) is the signum function.

Based on the PVAF (5), the RZNN model for solving DNE (1) is presented as follow:

The RZNN model with additive noises is also presented in Eq. (7):

where n(t) is the additive noise.

RZNN model analysis

As the basis of discussing and analyzing the RZNN model, the following Lemma 1 should be presented in advance.

Generally, a RNN could be depicted by the following differential dynamic system:

where \( x\left( t \right) \in {\mathbb{R}}^{\text{n}} \) stands for a suitable sized state. Let x(0) = x0 present a suitable sized initial state for the dynamic system (8), and assume x(t) = 0 standing for the equilibrium point of the dynamic system (8). There are several theories for the convergence the dynamic system (8).

Definition 1

[57,58,59,60]. The origin of the dynamic system (8) will be globally finite-time stable if the system is asymptotically and globally stable; and there exists a locally bounded setting time function T: \( {\mathbb{R}}^{\text{n}} \to {\mathbb{R}} + \cup \left\{ 0 \right\} \), such that x(t, x0) = 0 for all t ≥ T(x0).

Definition 2

[61,62,63]. The origin of the dynamic system (8) will be globally finite-time stable if the system is globally finite-time stable and the settling time function T is globally bounded, i.e., there exists a constant tf∈ℝ+ satisfying tf≥ T(x0) for all x0∈ℝn.

Lemma 1

[57, 64]. If there exists a radially continuous unbounded function V: ℝn → ℝ + ∪{0} such that V(ζ) = 0 for ζ∈Ω and any solution ζ(t) satisfies

where the constant parameters a, b, p, q, k >0, pk >1, qk <1. Then the set Ω is globally fixed-time attractive for the dynamic system (8), and the upper bound convergence time is

RZNN model analysis without noise

In this part, the RZNN for solving DNE (1) without noise will be analyzed.

Theorem 1

If the DNE (1) is solvable, the neural state solution x(t) of the RZNN model (6) with any random initial state x(0) converges to the theoretical roots x*(t) of DNE (1) in fixed time ts:

Proof

According to Eq. (3), the dynamic error function e(t) of RZNN model (6) can be expressed as:

As the new PVAF (5) is used, we adopt v(t) = |e(t)| as the Lyapunov function candidate, and the time differentiation of v(t) can be expressed as:

Then, based on Lemma 1, the bounded time ts can be directly obtained as:

As the bounded time ts is independent on the initial state of the system, and the RZNN model (6) is fixed-time stable in no noise environment.■

RZNN model analysis with noise

Noises are inevitable for any dynamic system, and the RZNN model (7) with various noises will be considered in this part.

Case 1: polluted by dynamic disappearing noise (DDN)

When the n(t) in (7) is a DDN, the following Theorem 2 ensures the stability of the RZNN model (7).

Theorem 2

If the DNE (1) is solvable, and the dynamic system is polluted by a DDN, which satisfies |n(t)| ≤ δ|e(t)| and γc ≥ δ (δ ∈ (0, +∞)). The neural state solution x(t) of the RZNN model (7) with any random initial state x(0) converges to the theoretical roots x*(t) of DNE (1) in fixed time ts:

Proof

According to Eq. (3), e(t) of RZNN model (7) can also be expressed as:

Here, we adopt v(t) = |e(t)|2 as the Lyapunov function candidate, and the time differentiation of v(t) can be expressed as:

As the new PVAF (5) is used, |n(t)| ≤ δ|e(t)| and γc ≥ δ, the following result can be obtained:

Based on Lemma 1, the bounded time ts can be directly obtained as:

Based on the above analysis, we can conclude that the RZNN model (7) polluted by DDN converges to the theoretical solution of DNE (1) within a bounded time ts, and ts is also irrelevant to the initial state of the system. ■

Case 2: polluted by dynamic non-disappearing noise (DNDN)

When the n(t) in (7) is a DNDN, the following Theorem 3 ensures the stability of the RZNN model (7).

Theorem 3

If the DNE (1) is solvable, and the dynamic system is polluted by a DNDN, which satisfies |n(t)| ≤ δ and γd ≥ δ (δ∈ (0, +∞)). The neural state solution x(t) of the RZNN model (7) with any random initial state x(0) converges to the theoretical roots x*(t) of DNE (1) in fixed time ts:

Proof

Similar to the proof of Theorem 2, we still choose the Lyapunov function candidate v(t) = |e(t)|2 to prove the fixed time convergence of the RZNN model (7) polluted by DNDN. The time differentiation of v(t) is

As the new PVAF (5) is used, |n(t)| ≤ δ and γd ≥ δ, the following result can be obtained:

Based on Lemma 1, the bounded time tb can be directly obtained as:

Based on the above analysis, we can conclude that the RZNN model (7) polluted by DNDN converges to the theoretical solution of DNE (1) within a bounded time ts, and ts is also irrelevant to the initial state of the system. ■

It is worthy to point out that Theorems 1, 2 and 3 demonstrate that the proposed RZNN model activated by the proposed PVAF (5) not only has the ability to converge to the theoretical solution X*(t) of DSE (1) in fixed-time ts, but also has the ability of rejecting interference and noises, and these are two important improvements of the ZNN model.

Numerical simulated verification

By adopting a new PVAF, a novel RZNN model is designed in Sect. 2, and its noise compatibility is analyzed and verified in Sect. 3. In this section, the numerical simulation results of the RZNN model in a noise-polluted environment for solving the DNE (1) are presented. In addition, the ZNN model (4) for solving the DNE (1) activated by the SBPAF in Table 1 is also provided for the purpose of comparison.

To verify the effectiveness and robustness of RZNN model (7), the following DNE is considered, and the design parameters are k1= k2= 5, γ = 1, p =5, q = 25.

The theoretical solutions of the DNE (20) are x*(t) = cos(2t), x*(t) = cos(2t)+ 5, x*(t) = − cos(2t) − 5. First, RZNN model (6) and ZNN model (4) activated by the SBPAF for solving the DNE (20) without noise is presented, then the RZNN model (7) and ZNN model (4) activated by the SBPAF for solving the DNE (20) attacked by various noises are considered.

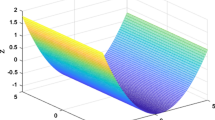

Generating from ten any arbitrary initial state x(0) ∈ [− 10, 10], RZNN model (6) with k =2 (the parameter k in PVAF (5) is set as 2) and ZNN model (4) activated by the SBPAF are used to solve DNE (20) without noise. Figure 1 is the neural state solutions x(t) generated by RZNN model (6) and ZNN model (4) activated by the SBPAF in no noise environment. The red dotted curves are the theoretical solutions of the above DNE (20), and the solid blue curves are neural state solutions generated by RZNN model (6) and the ZNN model (4). Figure 2 is the simulated residual errors of the two models.

As seen in Figs. 1 and 2, the RZNN model (6) and ZNN model (4) activated by the SBPAF are both effective for solving DNE (20) in no noise environment, but their convergence time is different. The ZNN model (4) activated by the SBPAF spends about 2.5 s to find the solution of the DNE (20), while the RZNN model (6) only spends about 0.1 s, and the RZNN model (6) is more effective and superior for solving DNE in no noise environment.

It is worthy to point out that the convergence performance of the RZNN model (6) is closely related to the parameter k in PVAF (5), and we can adopt different k values to control the convergence speed of the RZNN model (6), which has better practical application prospects than the ZNN model (4).

Then, the RZNN model (7) and ZNN model (4) activated by the SBPAF for solving the DNE (20) with the following four kinds of noises in Table 2 are considered.

Figure 3 is the neural state solutions x(t) generated by the RZNN model (7) and ZNN model (4) activated by the SBPAF for solving DNE (20) attacked by PN n(t) = 2cos(t), and Fig. 4 is the simulated residual errors of the two models.

As seen in Figs. 3 and 4, we can conclude that the ZNN model (4) activated by the SBPAF for solving DNE is very vulnerable to PN. When being attacked by PN, the neural state solutions of RZNN model (7) still converge to the theoretical solutions of DNE (20) effectively, but the ZNN model (4) activated by the SBPAF fails to solve the DNE (20), which demonstrates that the RZNN model (7) has better robustness than ZNN model (4) activated by the SBPAF under periodic noise attacks.

At last, more simulation results of the RZNN model (7) and ZNN model (4) activated by the SBPAF attacked by other different types of noises for solving the DNE (20) are considered. Figures 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 present the simulation results of the RZNN model (7) and ZNN model (4) attacked by the following other three types noises: CN n(t) = 1, NDN n(t) = 0.15t and DN n(t) = exp(− t). Following Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10, it can be observed that the external noises seriously deteriorate the convergence performance of the ZNN model (4) activated by the SBPAF, and it cannot obtain the accurate solutions of the DNE (20) when attacked by external noises. However, the RZNN model (7) always converges very quickly to the theoretical solutions of the DNE (20) under various noise disturbances, which further demonstrates the better robustness of the RZNN model (7). Moreover, we can also observe that the convergence speed of the RZNN model (7) is proportional to the parameter k in PVAF (5), which is a great improvement of the proposed RZNN model (7).

In summary, based on the above simulation example, we can conclude that the proposed RZNN model (7) is more effective in solving DNE in noise polluted environment. More importantly, compared to the ZNN model (4) activated by the SBPAF, the proposed RZNN model (7) has the advantages of better robustness, effectiveness, and fixed time convergence.

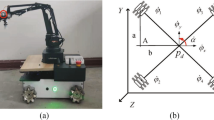

Robotic applications

With the development of artificial intelligence, the researches and applications of robots have aroused great interests in the academic and industrial communities in recent years [44, 65]. In this section, kinematic control of a mobile manipulator (MM) using the RZNN model (7) attacked by dynamic non-disappearing noise is considered. In addition, the ZNN model (4) activated by SBPAF is also applied to complete the same task for the purpose of comparison. The geometric model of the MM was introduced in Ref. [66]. According to Ref. [66], the forward kinematic equation of a MM can be described below:

In Eq. (21), r(t) represents the end-effector position, θ(t) is the joint angel, ξ(·) is a nonlinear mapping function between the end-effector and the joint angel. Generally, the position level Eq. (21) is converted to the velocity level kinematic equation.

where J(θ) = əξ(θ)/əθ denotes the Jacobian matrix.

The RZNN model (7) and the ZNN (4) activated by SPBAF are both used to the kinematic control of MM. The kinematic control models are shown as follows:

where σ1(·) stands for the proposed PVAF (5), and σ2(·) stands for the SBPAF in Table 1.

Equations (23) and (24) are the kinematic control models of the MM using the RZNN and ZNN activated by SPBAF, respectively. n(t) = 0.05t stands for non-vanishing noise.

Let us allocate a double circle for the MM to track, and the initial state of the MM is set as θ(0) = [0, 0, π/6, π/3, π/6, π/3, π/3, π/3]T, and task duration is 10 s. The experiment results are displayed in Figs. 11 and 12.

Trajectory tracking results of MM generated by ZNN model (4) activated by SPBAF with NVN n(t) = 0.05t. a Whole tracking motion trajectories. b Motion trajectories of the mobile platform. c Desired path and actual trajectory. d Tracking errors at the joint position level

Figures 11 and 12 are the trajectory tracking results of MM generated by the proposed RZNN (7) and the ZNN (4) with NDN n(t) = 0.05t, respectively.

Following Figs. 11 and 12, it is clear that the end-effector of the MM controlled by the proposed RZNN completes the double-circle path tracking task exactly, and its tracking errors are less than 0.6 mm when attacked by NDN, while the end-effector of the MM controlled by the ZNN model (4) cannot complete the double-circle path tracking task. The successful completion of double-circle tracking mission further validates the robustness and effectiveness of the RZNN.

Conclusion

In this work, a novel power-versatile activation function (PVAF) is presented. Based on the novel PVAF, a new RZNN model is proposed and analyzed for online finding of the solutions of DNE in noise-polluted environment. The fixed-time convergence of the proposed RZNN model is verified by rigorous mathematical analysis when attacked by various noises. In simulations, the ZNN model activated by the commonly used SBPAF for solving DNE in same conditions are also provided, and the comparison results demonstrate that the proposed RZNN model solves DNE effectively and accurately in noise polluted environment, while the ZNN model activated by SBPAF cannot solve the DNE properly in the same conditions. In addition, a successful completion of the noise-disturbed double-circle tracking task further verifies the practical application prospects of the proposed RZNN model.

References

Hammouch Z, Mekkaoui T (2018) Circuit design and simulation for the fractional-order chaotic behavior in a new dynamical system. Complex Intell Syst 4:251–260

Yu F, Liu L, Shen H et al (2020) Dynamic analysis, circuit design and synchronization of a novel 6D memristive four-wing hyperchaotic system with multiple coexisting attractors. Complexity 2020:17 (Article ID 5904607)

Jin J, Cui L (2019) Fully integrated memristor and its application on the scroll-controllable hyperchaotic system. Complexity 2019 (Article ID 4106398)

Jin J (2018) Programmable multi-direction fully integrated chaotic oscillator. Microelectron J 75:27–34

Yu F, Liu L, Xiao L et al (2019) A robust and fixed-time zeroing neural dynamics for computing time-variant nonlinear equation using a novel nonlinear activation function. Neurocomputing 350:108–116

Yu F, Liu L, He B et al. (2019) Analysis and FPGA realization of a novel 5D hyperchaotic four-wing memristive system, active control synchronization and secure communication application. Complexity 2019 (Article ID 4047957)

Yu F, Shen H, Liu L, Zhang Z, Huang Y, He B, Cai S, Song Y, Yin B, Du S, Xu Q (2020) CCII and FPGA realization: a multistable modified four-order autonomous Chua’s chaotic system with coexisting multiple attractors. Complexity 2020 (Article ID 5212601)

Jin J, Zhao L, Li M, Yu F, Xi Z (2020) Improved zeroing neural networks for finite time solving nonlinear equations. Neural Comput Appl 32:4151–4160

Yu F, Liu L, Qian S et al. (2020) Chaos-based application of a novel multistable 5D memristive hyperchaotic system with coexisting multiple attractors. Complexity 2020 (Article ID 8034196)

Yu F, Qian S, Chen X et al (2020) A new 4D four-wing memristive hyperchaotic system: dynamical analysis, electronic circuit design, shape synchronization and secure communication. Int J Bifurc Chaos. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218127420501412

Kumar M, Singh AK, Srivastava A (2013) Various Newton-type iterative methods for solving nonlinear equations. J Egypt Math Soc 21(3):334–339

Xiao XY, Yin HW (2018) Accelerating the convergence speed of iterative methods for solving nonlinear systems. Appl Math Comput 333:8–19

Sharma JR (2005) A composite third order Newton-Steffensen method for solving nonlinear equations. Appl Math Comput 169(1):242–246

Sharma JR, Kumar D (2018) A fast and efficient composite Newton-Chebyshev method for systems of nonlinear equations. J Complex 49:56–73

Amiri A, Cordero A, Darvishi MT, Torregrosa JR (2019) A fast algorithm to solve systems of nonlinear equations. J Comput Appl Math 354:242–258

Dai P, Wu Q, Wu Y, Liu W (2018) Modified Newton-PSS method to solve nonlinear equations. Appl Math Lett 86:305–312

Birgin EG, Martínez JM (2019) A Newton-like method with mixed factorizations and cubic regularization for unconstrained minimization. Comput Optim Appl 73(3):707–753

Saheya B, Chen GQ, Sui YK, Wu CY (2016) A new Newton-like method for solving nonlinear equations. SpringerPlus 5(1):1269

Sharma JR, Arora H (2017) Improved Newton-like methods for solving systems of nonlinear equations. SeMA 74:147–163

Ham YM, Chun C, Lee SG (2008) Some higher-order modifications of Newton’s method for solving nonlinear equations. J Comput Appl Math 222(2):477–486

Li S, He J, Li Y, Rafique MU (2017) Distributed recurrent neural networks for cooperative control of manipulators: a game-theoretic perspective. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 28(2):415–426

Huang C, Cao J, Cao J (2016) Stability analysis of switched cellular neural networks: a mode-dependent average dwell time approach. Neural Networks 82:84–99

Yang C, Huang L (2017) Finite-time synchronization of coupled time-delayed neural networks with discontinuous activations. Neurocomputing 249:64–71

Cai Z, Pan X, Huang L et al (2018) Finite-time robust synchronization for discontinuous neural networks with mixed-delays and uncertain external perturbations. Neurocomputing 275:2624–2634

Wang D, Huang L, Tang L (2018) Synchronization criteria for discontinuous neural networks with mixed delays via functional differential inclusions. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 29(5):1809–1821

Wang D, Huang L, Tang L et al (2018) Generalized pinning synchronization of delayed Cohen-Grossberg neural networks with discontinuous activations. Neural Netw 104:80–92

Cai ZW, Huang L-H (2018) Finite-time synchronization by switching state-feedback control for discontinuous Cohen-Grossberg neural networks with mixed delays. Int J Mach Learn Cybern 9:1683–1695

Long M, Zeng Y (2019) Detecting iris liveness with batch normalized convolutional neural network. Comput Mater Continua 58(2):493–504

Wang D, Huang L, Tang L (2018) Dissipativity and synchronization of generalized BAM neural networks with multivariate discontinuous activations. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 29(8):3815–3827

Wang F, Zhang L, Zhou S, Huang Y (2019) Neural network-based finite-time control of quantized stochastic nonlinear systems. Neurocomputing 362:195–202

Zhou L, Tan F, Yu F, Liu W (2019) Cluster synchronization of two-layer nonlinearly coupled multiplex networks with multi-links and time-delays. Neurocomputing 359:264–275

Zhou L, Tan F, Yu F (2019) A robust synchronization-based chaotic secure communication scheme with double-layered and multiple hybrid networks. IEEE Syst J. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSYST.2019.2927495

Li W, Xu H, Li H et al (2019) Complexity and algorithms for superposed data uploading problem in networks with smart devices. IEEE Internet Things J. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2019.2949352

Huang C, Liu B (2019) New studies on dynamic analysis of inertial neural networks involving non-reduced order method. Neurocomputing 325:283–287

Cai Z, Huang L (2018) Finite-time stabilization of delayed memristive neural networks: discontinuous state-feedback and adaptive control approach. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 29(4):856–868

Wang Z, Guo Z, Huang L et al (2017) Dynamical behavior of complex-valued hopfield neural networks with discontinuous activation functions. Neural Process Lett 45(3):1039–1061

Zhu E, Yuan Q (2013) pth Moment exponential stability of stochastic recurrent neural networks with markovian switching. Neural Process Lett 38(3):487–500

Stanimirovic PS, Petkovic MD (2018) Gradient neural dynamics for solving matrix equations and their applications. Neurocomputing 306:200–212

Xiao L, Li K, Tan Z, Zhang Z, Liao B, Chen K, Jin L, Li S (2019) Nonlinear gradient neural network for solving system of linear equations. Inf Process Lett 142:35–40

Liao S, Liu J, Xiao X, Fu D, Wang G, Jin L (2020) Modified gradient neural networks for solving the time-varying Sylvester equation with adaptive coefficients and elimination of matrix inversion. Neurocomputing 379:1–11

Zhang Z, Li Z, Zhang Y, Luo Y, Li Y (2015) Neural-dynamic-method-based dual-arm CMG scheme with time-varying constraints applied to humanoid robots. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 26(12):3251–3262

Li S, Zhang Y, Jin L (2017) Kinematic control of redundant manipulators using neural networks. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 28(10):2243–2254

Xiao L, Liao B, Li S, Zhang Z, Ding L, Jin L (2018) Design and analysis of FTZNN applied to the real-time solution of a nonstationary lyapunov equation and tracking control of a wheeled mobile manipulator. IEEE Trans Ind Inf 14(5):98–105

Guo D, Zhang Y (2014) Acceleration-level inequality-based MAN scheme for obstacle avoidance of redundant robot manipulators. IEEE Trans Ind Electron 61(12):6903–6914

Zhang Y, Ge SS (2005) Design and analysis of a general recurrent neural network model for time-varying matrix inversion. IEEE Trans Neural Netw 16(6):1477–1490

Li Z, Zhang Y (2010) Improved Zhang neural network model and its solution of time-varying generalized linear matrix equations. Expert Syst Appl 37(10):7213–7218

Jin J, Xiao L, Lu M, Li J (2019) Design and analysis of two FTRNN models with application to time-varying sylvester equation. IEEE Access 7:58945–58950

Zhang Y, Li W, Guo D, Ke Z (2013) Different Zhang functions leading to different ZNN models illustrated via time-varying matrix square roots finding. Expert Syst Appl 40(111):4393–4403

Shen Y, Miao P, Huang Y, Shen Y (2015) Finite-time stability and its application for solving time-varying Sylvester equation by recurrent neural network. Neural Process Lett 42(3):763–784

Xiao L, Liao B (2016) A convergence-accelerated Zhang neural network and its solution application to Lyapunov equation. Neurocomputing 193:213–218

Li S, Chen S, Liu B (2013) Accelerating a recurrent neural network to finite-time convergence for solving time-varying Sylvester equation by using a sign-bi-power activation function. Neural Process Lett 37(2):189–205

Jin L, Zhang Y, Li S (2016) Integration-enhanced Zhang neural network for real-time-varying matrix inversion in the presence of various kinds of noises. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 27(12):2615–2627

Jin L, Li S, Hu B, Liu M, Yu J (2019) Noise-suppressing neural algorithm for solving time-varying system of linear equations: a control-based approach. IEEE Trans Ind Inf 15(1):236–246

Xiao L, Zhang Y, Dai J, Chen K, Yang S, Li W, Liao B, Ding L, Li J (2019) A new noise-tolerant and predefined-time ZNN model for time-dependent matrix inversion. Neural Netw 117:124–134

Zhang Y, Peng HF (2007) Zhang neural network for linear time-varying equation solving and its robotic application. In: 2007 International conference on machine learning and cybernetics, pp 3543–3548

Zhang Y, Chen K, Li X, Yi C, Zhu H (2008) Simulink modeling and comparison of Zhang neural networks and gradient neural networks for time-varying Lyapunov equation solving. In: Proceedings of IEEE international conference on natural computation, vol 3, pp 521–525

Polyakov A (2012) Nonlinear feedback design for fixed-time stabilization of linear control systems. IEEE Trans Autom Control 57(8):2106–2110

Polyakov A, Efimov D, Perruquetti W (2015) Finite-time and fixed-time stabilization: implicit Lyapunov function approach. Automatica 51:332–340

Khelil N, Otis MJD (2016) Finite-time stabilization of homogeneous non-Lipschitz systems. Mathematics 4(4):58

Zhou Y, Zhu W, Du H (2017) Global finite-time attitude regulation using bounded feedback for a rigid spacecraft. Control Theory Technol 15(1):26–33

Snchez-Torres JD, Sanchez EN, Loukianov AG (2014) A discontinuous recurrent neural network with predefined time convergence for solution of linear programming. In: Proceedings of the IEEE symposium on swarm intelligence, pp 1–5

Becerra HM, Vzquez CR, Arechavaleta G, Delfin J (2018) Predefined-time convergence control for high-order integrator systems using time base generators. IEEE Trans Control Syst Technol 26(5):1866–1873

Snchez-Torres JD, Sanchez EN, Loukianov AG (2013) Recurrent neural networks with fixed time convergence for linear and quadratic programming. In: Proceedings of the Iinternational joint conference on neural networks, pp 1–5

Aouiti C, Miaadi F (2020) A new fixed-time stabilization approach for neural networks with time-varying delays. Neural Comput Appl 32:3295–3309

Zhang Z, Beck A, Magnenat-Thalmann N (2015) Human-like behavior generation based on head-arms model for tracking external targets and body parts. IEEE Trans Cybern 45(8):1390–1400

Xiao L, Zhang Y (2014) A new performance index for the repetitive motion of mobile manipulators. IEEE Trans Cybern 44(2):280–292

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, J. A robust zeroing neural network for solving dynamic nonlinear equations and its application to kinematic control of mobile manipulator. Complex Intell. Syst. 7, 87–99 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-020-00178-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-020-00178-9